Submitted:

07 October 2024

Posted:

08 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Types of Studies

2.3. Types of Participants and Exposure

2.4. Types of Outcome Measures

2.5. Information Sources and Search

2.6. Study Selection

2.7. Data Collection Process

2.8. Assessment of Methodological Quality and Risk Bias

2.9. Data Items and Analysis

3. Results

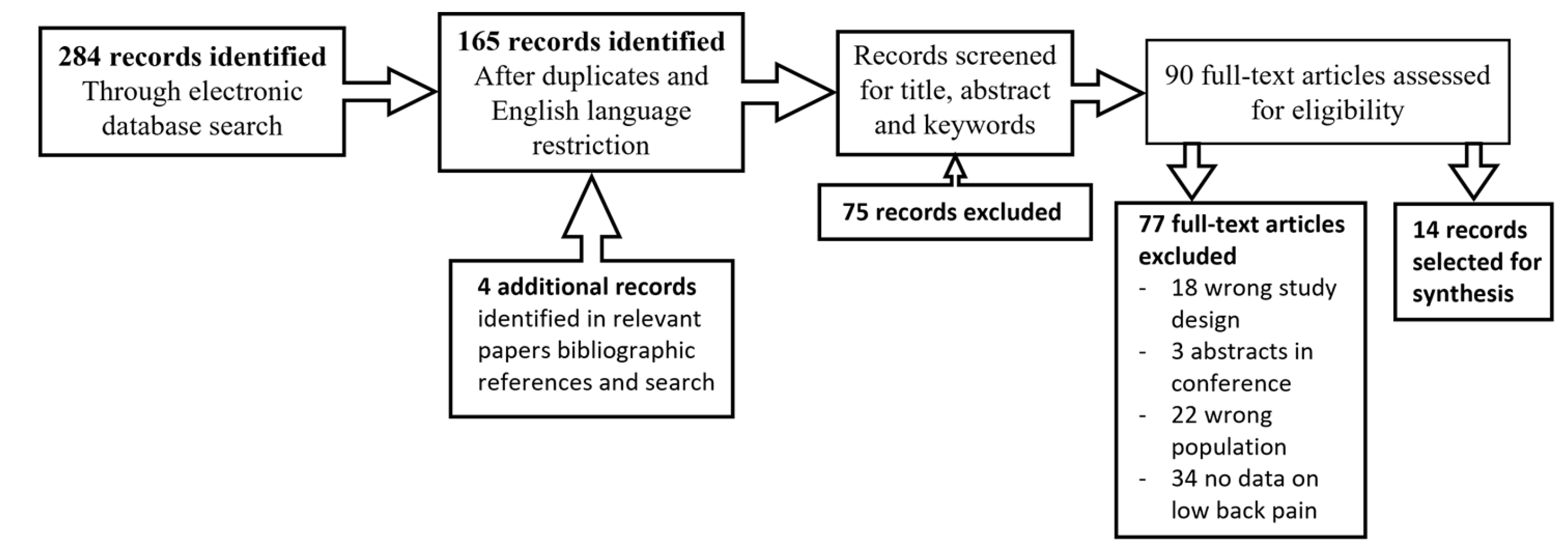

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Methodological Quality

3.4. Demographic and Anthropometric Characteristics of the Sample

3.5. Equestrian Sports

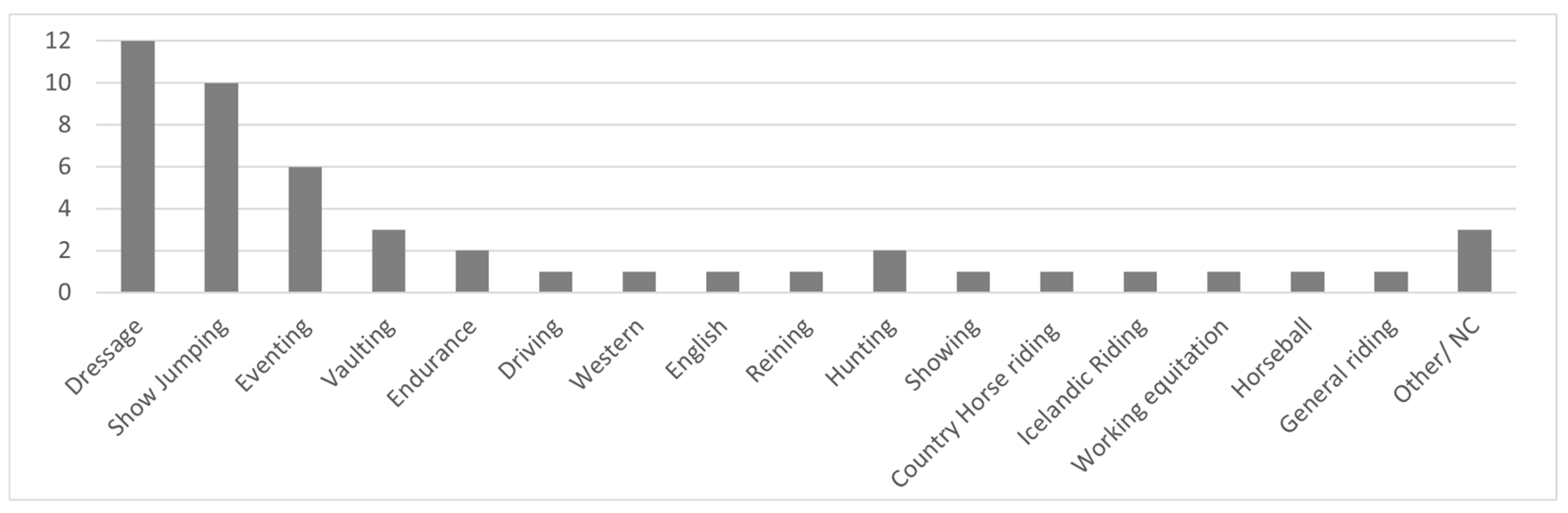

3.5.1. Discipline

3.5.2. Level of Sport

3.5.3. Sport Practice

3.5.4. Equestrian Related Activities

3.6. Other Sporting Activities

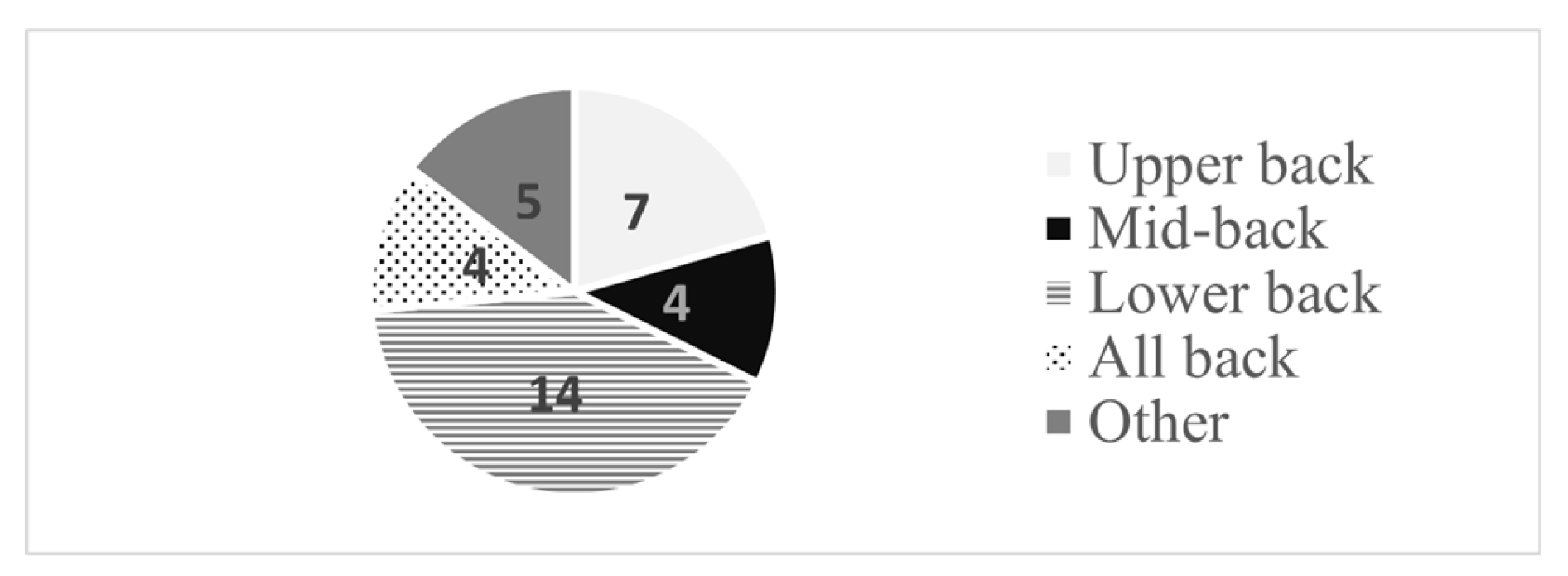

3.7. Anatomic Location and Nature of Injury

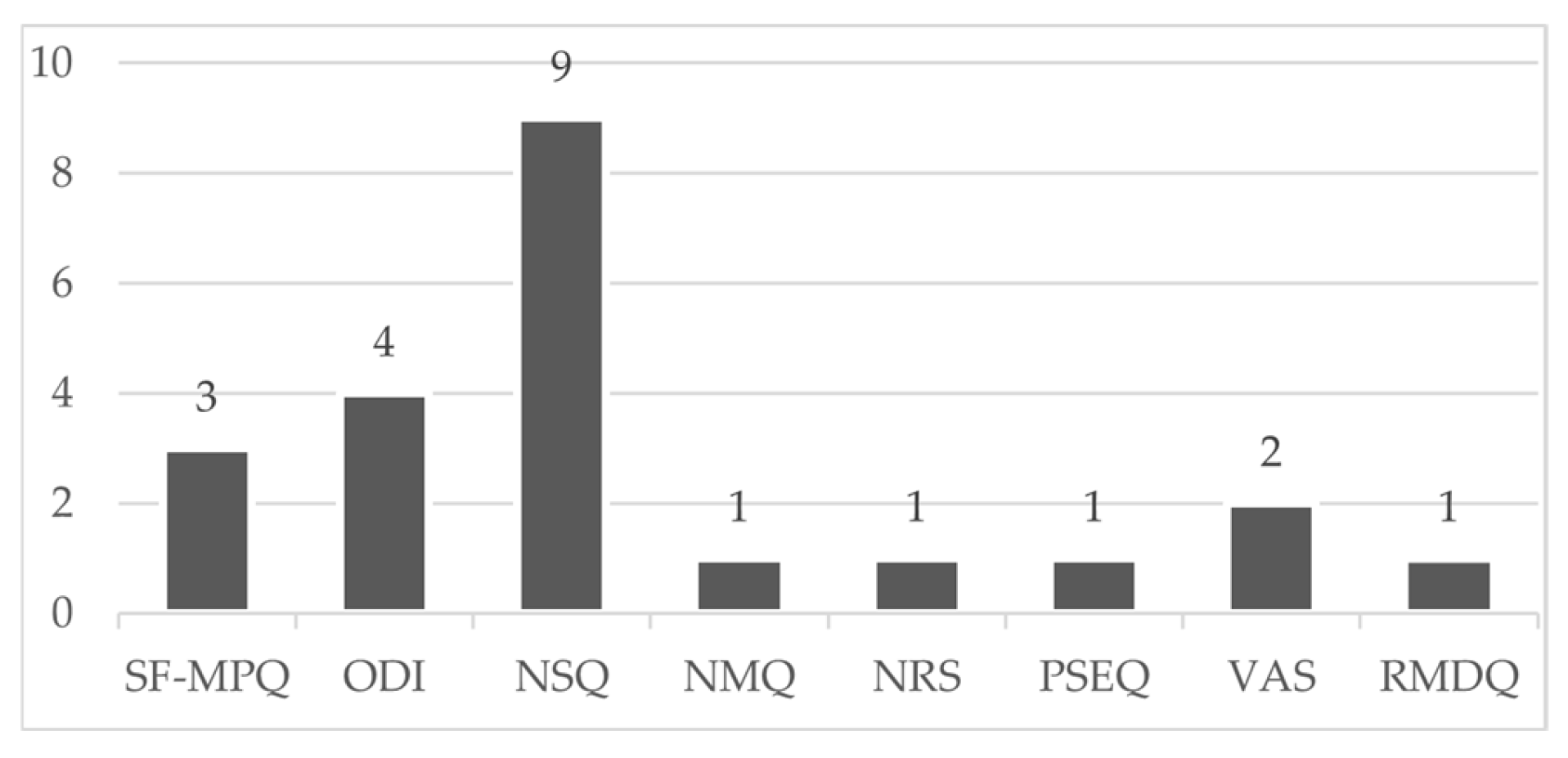

3.8. Tools and Methods for Measurement of LBP

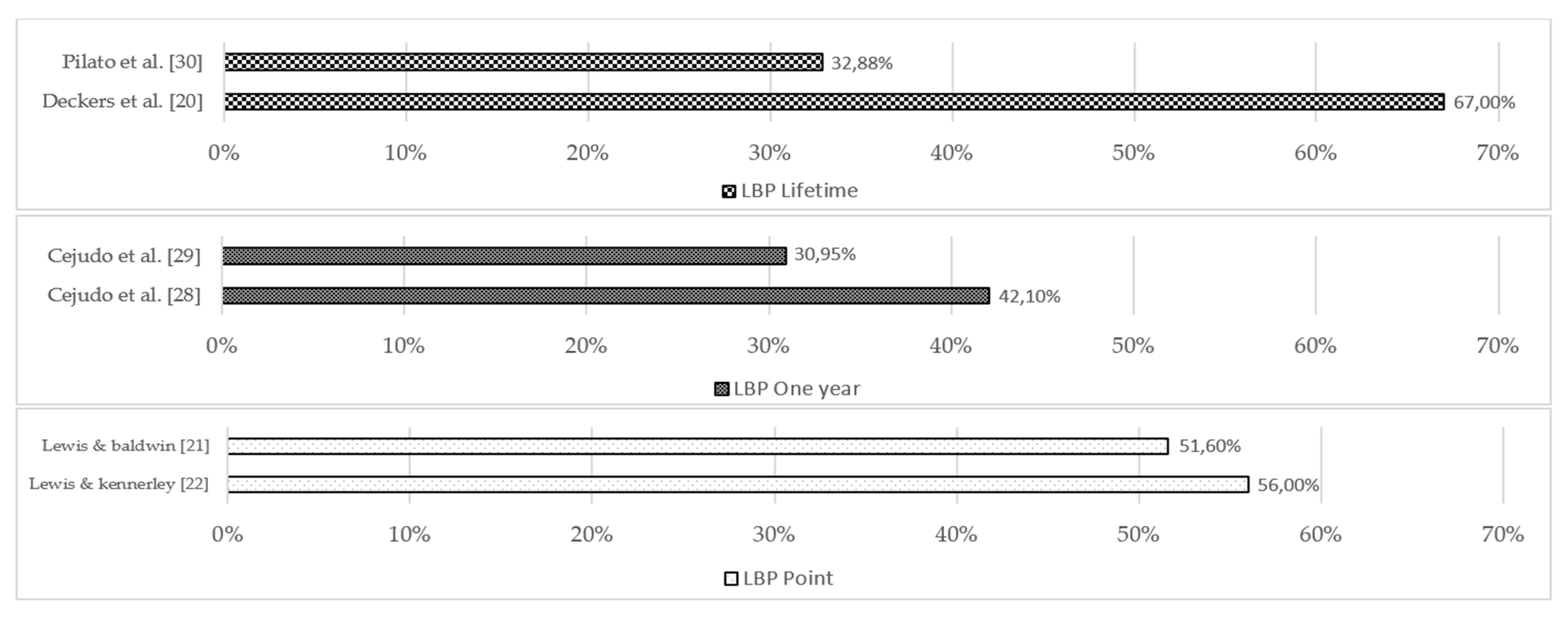

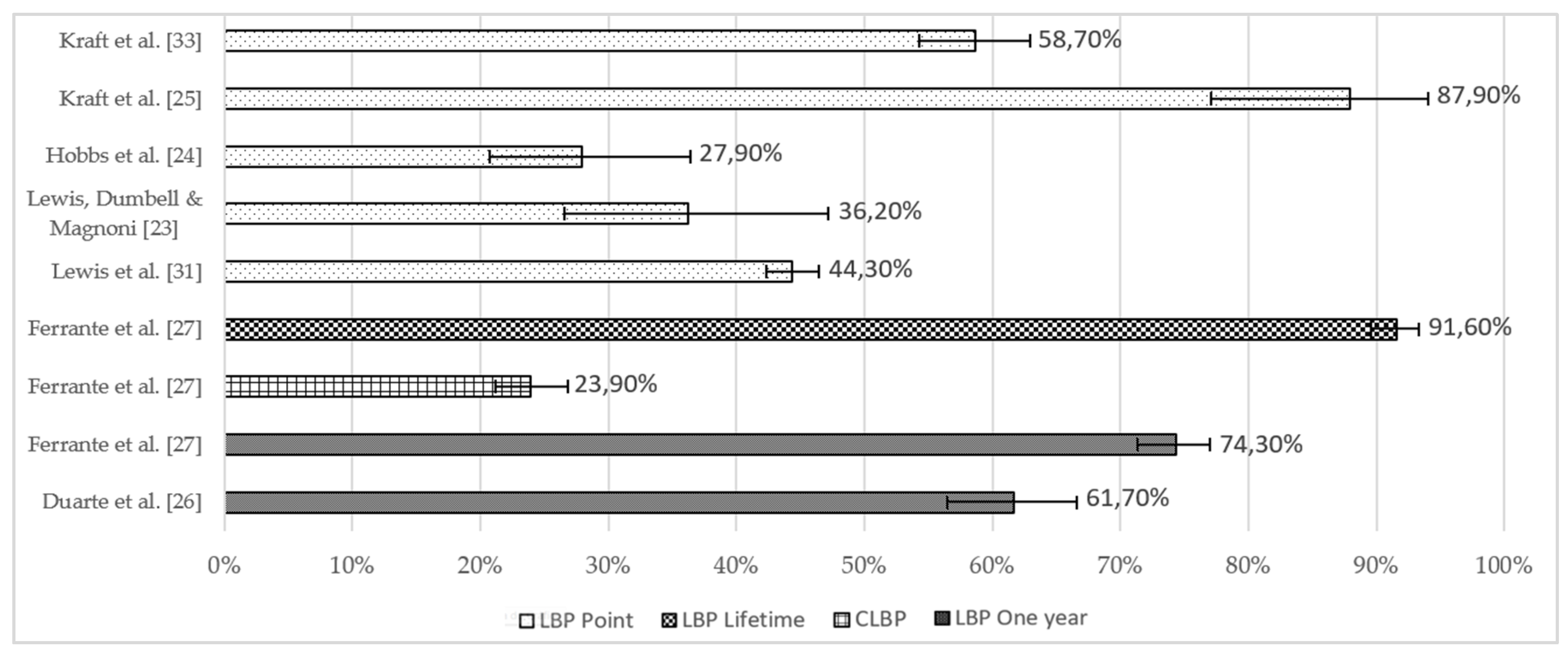

3.9. Lower Back Pain

3.10. Duration and Frequency of Symptoms

3.11. Consequences of Pain

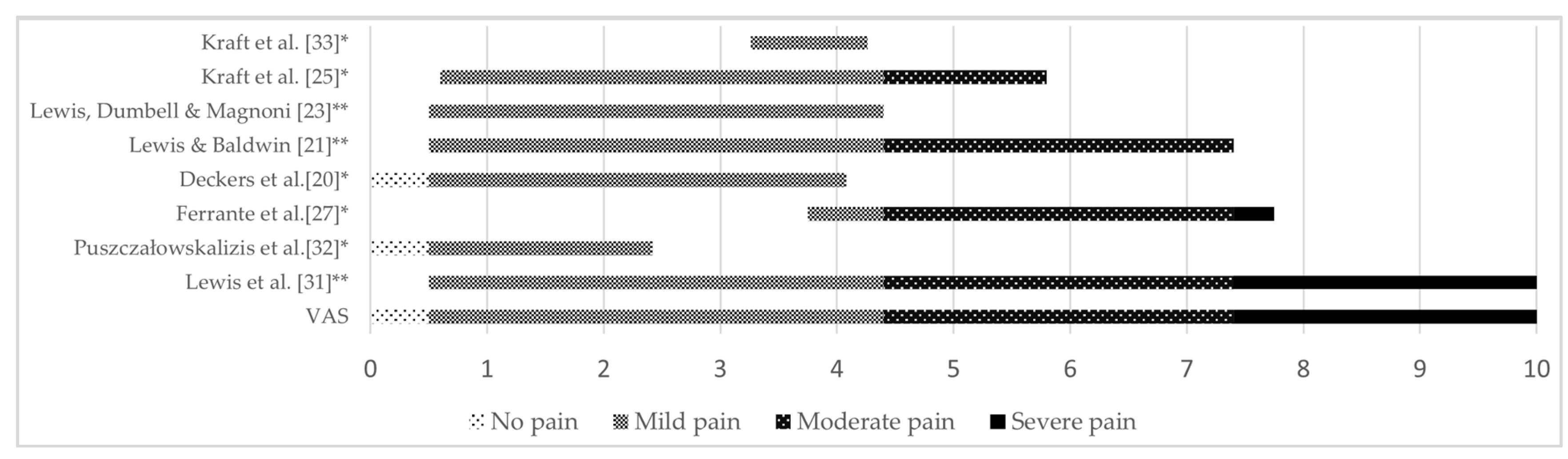

3.11.1. Levels of Pain, Severity, and Levels of Disability

3.11.2. Time Loss

3.11.3. Pain Management Techniques

3.12. Risk Factors, Associations and Contributing Factors for LBP

4. Discussion

- Study Quality: Conducting higher-quality studies is essential to provide more substantial evidence regarding which variables pose risk factors for LBP and which do not.

- Research Tools: There is a pressing need to develop standardized questionnaires that address key questions, enabling researchers to better understand the prevalence of LBP in EA and the factors contributing to its existence.

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoy, D.; Bain, C.; Williams, G.; March, L.; Brooks, P.; Blyth, F.; Woolf, A.; Vos, T.; Buchbinder, R. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis rheum 2021, 64, 2028-2037. [CrossRef]

- Trompeter, K.; Fett, D.; Platen, P. Prevalence of Back Pain in Sports: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sports Med 2017, 47, 1183-1207. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Ning, J.; Chuter, V.H.; Taylor, J.B.; Christophe, D.; Meng, Z.; Jiang, L. Exercise alone and exercise combined with education both prevent episodes of low back pain and related absenteeism: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials [RCTs] aimed at preventing back pain. Br J Sports Med 2020, 54, 766-770. [CrossRef]

- Heneweer, H.; Picavet, H.; Staes, F.; Kiers, H.; Vanhees, L. Physical fitness, rather than self-reported physical activities, is more strongly associated with low back pain: evidence from a working population. Eur Spine J 2012, 21, 1265-1272. [CrossRef]

- Quinn, S.; Bird, S. Influence of saddle type upon the incidence of lower back pain in equestrian riders. Br J Sports Med 1996, 30, 140-144. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, F.; Ardern, C.L.; Hartvigsen, J.; Dane, K.; Trompeter, K.; Trease, L.; Vinther, A.; Gissane, C.; McDonnell, S.J.; Carneiro, J.P.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors for back pain in sports: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2021, 55, 601-607. [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. Performance analysis in equestrian sport. Comp Exerc Physiol 2013, 9, 67-77. [CrossRef]

- Pugh, T.J.; Bolin, D. Overuse Injuries in Equestrian Athletes. Curr Sports Med Rep 2004, 3, 297-303. [CrossRef]

- Dumbell, L.C.; Rowe, L.; Douglas, J.L. Demographic profiling of British Olympic equestrian athletes in the twenty-first century. Sport Soc 2018, 21, 1337-1350. [CrossRef]

- Haan, D. A Review of the Appropriateness of Existing Micro- and Meso-level Models of Athlete Development within Equestrian Sport. Int J Hum Mov Sports Sci 2017, 5, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Hoy, D.; Brooks, P.; Blyth, F.; Buchbinder, R. The epidemiology of low back pain. Best Prat Res Clin Rheumatol 2010, 24, 769-781. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, V.; Douglas, J.L.; Edwards, T.; Dumbell, L. A preliminary study investigating functional movement screen test scores in female collegiate age horse-riders. Comparative Exercise Physiology 2019, 15, 105-112. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [CrossRef]

- Carlson, M.D.; Morrison, R.S. Study Design, Precision, and Validity in Observational Studies. J Palliat Med 2009, 12, 77-82. [CrossRef]

- Drukker, M.; Weltens, I.; van Hooijdonk, C.; Vandenberk, E.; Bak, M. Development of a methodological quality criteria list for observational studies: the observational study quality evaluation. Front Res Metr Anal 2021, 6675071. [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Moola, S.; Lisy, K.; Riitano, D.; Tufanaru, C. Chapter 5: Systematic reviews of prevalence and incidence. In JBI Manual for evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z. Eds.; JBI: South Australia, 2020, 177-217. [CrossRef]

- Corporation, Microsoft. Microsoft Excel (Version 2021). Available online: https://www.microsoft.com.

- Naing, L.; Nordin, R.; Rahman, H.; Naing, Y. Sample size calculation for prevalence studies using Scalex and ScalaR calculators. BMC Med Res Methodol 2022, 22, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Epitools Epidemiological Calculators. (Ausvet) Available online: Sergeant, ESG: https://epitools.ausvet.com.au/ciproportion (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Deckers, I.; De Bruyne, C.; Roussel, N.A.; Truijen, S.; Minguet, P.; Lewis, V.; Wilkins, C.; Van Breda, E. Assessing the sport-specific and functional characteristics of back pain in horse riders. Comp Exerc Physiol 2021, 17, 7-15. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, V.; Baldwin, K. A preliminary study to investigate the prevalence of pain in international event riders during competition, in the United Kingdom. Comp Exerc Physiol 2018, 14, 173-181. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, V.; Kennerley, R. A preliminary study to investigate the prevalence of pain in elite dressage riders during competition in the United Kingdom. Comp Exerc Physiol 2017, 13, 259-263. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, V.; Dumbell, L.; Magnoni, F. A Preliminary Study to Investigate the Prevalence of Pain in Competitive Showjumping Equestrian Athletes. J Phys Fitness Med Treat Sports 2018, 4. [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, S. J.; Baxter, J.; Louise, B.; Laura-Ann, R.; Jonathan, S.; Hilary, C. M. Posture, Flexibility and Grip Strength in Horse Riders. J Hum Kinet 2014, 42, 113-125. [CrossRef]

- Kraft, C.N.; Peter, P.H.; Ute, B.; Mei, Y.; Oliver, D.; Christian, L.; Makus, F.V. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings of the Lumbar Spine in Elite Horseback Riders: Correlations With Back Pain, Body Mass Index, Trunk/Leg-Length Coefficient, and Riding Discipline. Am J Sports Med 2009, 37, 2205-2213. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.; Santos, R.; Fernandes, O.; Raimundo, A. Prevalence of Lower Back Pain in Portuguese Equestrian Riders. Sports 2024, 12, 207. [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, M.; Bonetti, F.; Quattrini, F.M.; Mezzetti, M.; Demarie, S. Low Back Pain, and Associated Factors among Italian Equestrian Athletes: a Cross-Sectional Study. MLTJ 2021, 11, 344. [CrossRef]

- Cejudo, A.; Ginés-Díaz, A.; Rodrígues-Ferrán, O.; Santonja-Medina, F.; Sainz De Baranda, P. Trunk Lateral Flexor Endurance and Body Fat: Predictive Risk Factors for Low Back Pain in Child Equestrian Athletes. Children 2020, 7, 172. [CrossRef]

- Cejudo, A.; Ginés-Días, A.; Sainz De Baranda, P. Asymmetry and Tightness of Lower Limb Muscles in Equestrian Athletes: Are They Predictors for Back Pain? Symmetry 2020, 12, 1679. [CrossRef]

- Pilato, M.; Henry, T.; Malavase, D. Injury History in the Collegiate Equestrian Athlete: Part I: Mechanism of Injury, Demographic Data and Spinal Injury. JSMAHS 2017, 2, 3. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, V.; Nicol, Z.; Dumbell, L.; Cameron, L. A Study Investigating Prevalence of Pain in UK Horse Riders over Thirty-Five Years Old. Int J Equine Sci 2023, 2, 9-18.

- Puszczałowska-Lizis, E.; Szymański, D.; Pietrzak, P.; Wilczyński, M. Incidence of back pain in people practicing amateur horse riding. Fizjoterapia polska 2022, 22. [CrossRef]

- Kraft, C.; Urban, N.; Ilg, A.; Wallny, T.; Scharfstädt, A.; Jäger, M.; Pennekamp, P. Einfluss der Reitdisziplin und -intensität auf die Inzidenz von Rückenschmerzen bei Reitsportlern. Influence of the riding discipline and riding intensity on the incidence of back pain in competitive horseback riders, Sportverletzung Sportschaden: Organ der Gesellschaft fur Orthopadisch-Traumatologische Sportmedizin 2007, 21, 29-33. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.; Chen, C.; Brugger, A. Interpretation of visual analog scale ratings and change scores: a reanalysis of two clinical trials of postoperative pain. J Pain 2003, 4, 407-414. [CrossRef]

- Millet, G.; Brocherie, F.; Burtscher, J. Olympic Sports Science—Bibliometric Analysis of All Summer and Winter Olympic Sports Research. Front Sports Act Living 2021, 3, 772140. [CrossRef]

- Olympic Equestrian—History. Available online: https://olympics.com/en/paris-2024/sports/equestrian (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Gebrye, T.; Fatoye, F.; Mbada, C.; Hakimi, Z. A scoping review on quality assessment tools used in systematic reviews and meta-analysis of real-world studies. Rheumatol Int 2023, 43, 1573-1581. [CrossRef]

- Arachtingi, D. Foster the Gender Equality in the context of horse-riding. An Olympic Value which reveals a path from domination to emancipation. Diagoras Int Acad J Olympic Stud 2020, 4, 60-74.

- Plymoth, B. Gender in equestrian sports: an issue of difference and equality. Sport Soc 2012, 15, 335-348. [CrossRef]

- de Haan, D.; Henry, I.; Sotiriadou, P. Evaluating the place of equestrian sport in the Long-Term Athlete Development (LTAD) and the Sport Policy factors that Lead to International Sporting Success (SPLISS) models. In Proceedings of the SPLISS conference. Melbourne, Australia, 2015.

- Cleary, K. Joyful Equestrian. Available online: https://www.joyfulequestrian.com/horse-disciplines/?utm_content=cmp-true (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Disciplines. Available online: https://www.fei.org/disciplines (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Paris 2024—Sports—Equestrian. Available online: https://olympics.com/en/paris-2024/sports/equestrian (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Para Equestrian. Available online: https://olympics.com/en/paris-2024/paralympic-games/sports/para-equestrian (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- National Federations. Available online: https://inside.fei.org/fei/about-fei/structure/national-federations (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- FEI Facts and Figures. Available online: https://inside.fei.org/fei/about-fei/publications/fei-annual-report/2021/feifactsandfigures/ (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Lamperd, W.; Clarke, D.; Wolframm, I.; Williams, J. What makes an elite equestrian rider? Comp Exerc Physiol 2016, 12, 105-118. [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; Tabor, G. Rider impacts on equitation. Appl Anim Behav Sci 2017, 190, 28-42. [CrossRef]

- Bahr, R.; Clarsen, B.; Derman, W.; Dvorak, J.; Emery, C.A.; Finch, C.F.; Hägglund, M.; Junge, A.; Kemp, S.; Khan, K.M; et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement: methods for recording and reporting of epidemiological data on injury and illness in sport 2020 (including STROBE Extension for Sport Injury and Illness Surveillance (STROBE-SIIS)). Orthop J Sports Med 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Heneweer, H.; Vanhees, L.; Picavet, H. Physical activity and low back pain: A U-shaped relation? Pain 2009, 143, 21-25. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C.; Zwingenberger, S.; Walther, A.; Reuter, U.; Kasten, P.; Seifert, J.; Günther, K.P.; Steiehler, M. Prevalence of Low Back Pain in Adolescent Athletes—an Epidemiological Investigation. Int J Spots Med 2014, 35, 684-689. [CrossRef]

- Catalá, M.; Schroll, A.; Laube, G.; Arampatzis, A. Muscle Strength and Neuromuscular Control in Low-Back Pain: Elite Athletes Versus General Population. Front Neurosci 2018, 12. [CrossRef]

- Noormohammadpour, P.; Khezri, A.H.; Farahbakhsh, F.; Mansournia, M.A.; Smuck, M.; Kordi, R. Reliability and Validity of Athletes Disability Index Questionnaire. Clin J Sport Med 2018, 28, 159-167. [CrossRef]

- Shafshak, T.S.; Elnemr, R. The visual analogue scale versus numerical rating scale in measuring pain severity and predicting disability in low back pain. JCR J Clin Rheumatol 2021, 27, 282-285. [CrossRef]

- Zamani, E.; Kordi, R.; Nourian, R.; Noorian, N.; Memari, A.H.; Shariati, M. Low back pain functional disability in athletes; conceptualization and initial development of a questionnaire. Asian J Spots Med 2014, 5. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, V.D.; Silva, R.F.; Borges, S.; Fernandes, M.; Miñana-Signes, V.; Monfort-Pañego, M.; Noll, P.R.E.S.; Noll, M. Instruments for assessing back pain in athletes: A systematic review. Plos one 2023, 18. [CrossRef]

- Hainline, B.; Derman, W.; Vernec, A.; Budgett, R.; Deie, M.; Dvořák, J.; Harle, C.; Herring, S.A.; McNamee, M.; Meeuwisse, W.; et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement on pain management in elite athletes. Br J Sports Med 2017, 51, 1245-1258. [CrossRef]

- Noormohammadpour, P.; Rostami, P.; Mansournia, M.; Farahbakhsh, F.; Pourgharib Shahi, M.H. Kordi, R. Low back pain status of female university students in relation to different sport activities. Eur Spine J 2016, 25, 1196-1203. [CrossRef]

- Wernli, K.; Tan, J.; O’Sullivan, P.; Smith, A.; Campbell, A,; Kent, P. Does movement change when low back pain changes? A systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2020, 50, 664-670. [CrossRef]

- Nadler, S.; Moley, P.; Malanga, G.; Rubbani, M.; Prybicien, M.; Feinberg, J.H. Functional deficits in athletes with a history of low back pain: a pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002, 83, 1753-1758. [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, J.; Zebardast, J.; Mirzashahi, B. Low back pain in athletes. Asian J Sports Med 2015, 6. [CrossRef]

- Orr, R.; Canetti, E.; Pope, R.; Lockie, R.; Dawes, J.; Schram, B. Characterization of Injuries Suffered by Mounted and Non-Mounted Police Officers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20, 1144. [CrossRef]

- Sugavanam, T.; Sannasi, R.; Anand, P.; Ashwin Javia, P. Postural asymmetry in low back pain–a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Disabil Rehabil 2024, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Low back pain. Available on: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/low-back-pain#:~:text=LBP%20can%20be%20experienced%20at%20any%20age%2C%20and,years.%20LBP%20is%20more%20prevalent%20in%20women%20%282%29. (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Shiri, R.; Falah-Hassani, K.; Heliövaara, M.; Solovieva, S.; Amiro, S.; Lallukka, T.; Burdorf, A.; Husgafvel-Pursiainen, K.; Vikari-Juntura, E. Risk factors for low back pain: a population-based longitudinal study. Arthritis Care Res 2019, 71, 290-299. [CrossRef]

- Moradi, V.; Memari, A.; Shayestehfar, M.; Kordi, R. Low Back Pain in Athletes Is Associated with General and Sport Specific Risk Factors: A Comprehensive Review of Longitudinal Studies. Rehabil Res Pract 2015, 2015, 850184. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, T.P.; Arnold, J.B.; Evans, A.M.; Yaxley, A.; Damarell, R.; Shanahan, E.M. The association between body fat and musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2018, 19, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Papagelopoulos, P.; Boscainos, P.; Giannakopoulos, P.; Zoubos, A. Degenerative Spondyloarthropathy of the Cervical and Lumbar Spine in Jockeys. Orthopedics 2001, 24, 561-564. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Trask, C.; Kociolek, A.M. Whole-body vibration exposure of occupational horseback riding in agriculture: A ranching example. Am J Ind Med 2017, 60, 215-220. [CrossRef]

- Burstrom, L.; Nilsson, T.; Wahlstrom, J. Whole-body vibration and the risk of low back pain and sciatica: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2015, 88, 403-418. [CrossRef]

- Löfqvist, L.; Pinzke, S. Working with Horses: An OWAS Work Task Analysis. J Agric Saf Health 2011, 17, 3-14. [CrossRef]

- Löfqvist, L.; Osvalder, A.L.; Bligård, L.A.; Pinzke, S. An analytical ergonomic risk evaluation of body postures during daily. Work 2015, 51, 667-682. [CrossRef]

- Heneweer, H.; Staes, F.; Aufdemkampe, G.; van Rijn, M.; Vanhees, L. Physical activity, and low back pain: a systematic review of recent literature. Eur Spine J 2011, 20, 826-845. [CrossRef]

| Papers (N, %) | Participants (N, %) | |

|---|---|---|

| Dressage | 12, 85.7 | 2310, 51 |

| Show Jumping | 10, 71.4 | 1996, 44.1 |

| Eventing | 6, 42.9 | 644, 14.2 |

| Rider status | Level of competition | Competitive/ non-competitive | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deckers et al. [20] | Professional & Amateur | National | Competitive |

| Lewis & Baldwin. [21] | - | International | Competitive |

| Lewis & Kennerley. [22] | Elite | International | Competitive |

| Lewis, Dumbell & Magnoni. [23] | Recreational, Amateur & Professional | Competitive | |

| Hobbs et al. [24] | - | - | Competitive |

| Kraft et al. [25] | Elite | National/ International/ Olympic | Competitive |

| Duarte et al. [26] | Hobby & Profession | - | - |

| Ferrante et al. [27] | - | Sport license * | Competitive/ non-competitive |

| Cejudo et al. [28] | - | - | Competitive |

| Cejudo et al. [29] | - | - | Competitive |

| Pilato et al. [30] | - | Intercollegiate | Competitive |

| Lewis et al. [31] | Leisure, Amateur & Professional | - | Competitive/ non-competitive |

| Puszczałowska-lizis et al. [32] | Amateur | - | - |

| Kraft et al. [33] | - | Performance classes ** | Competitive |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).