Submitted:

07 October 2024

Posted:

08 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

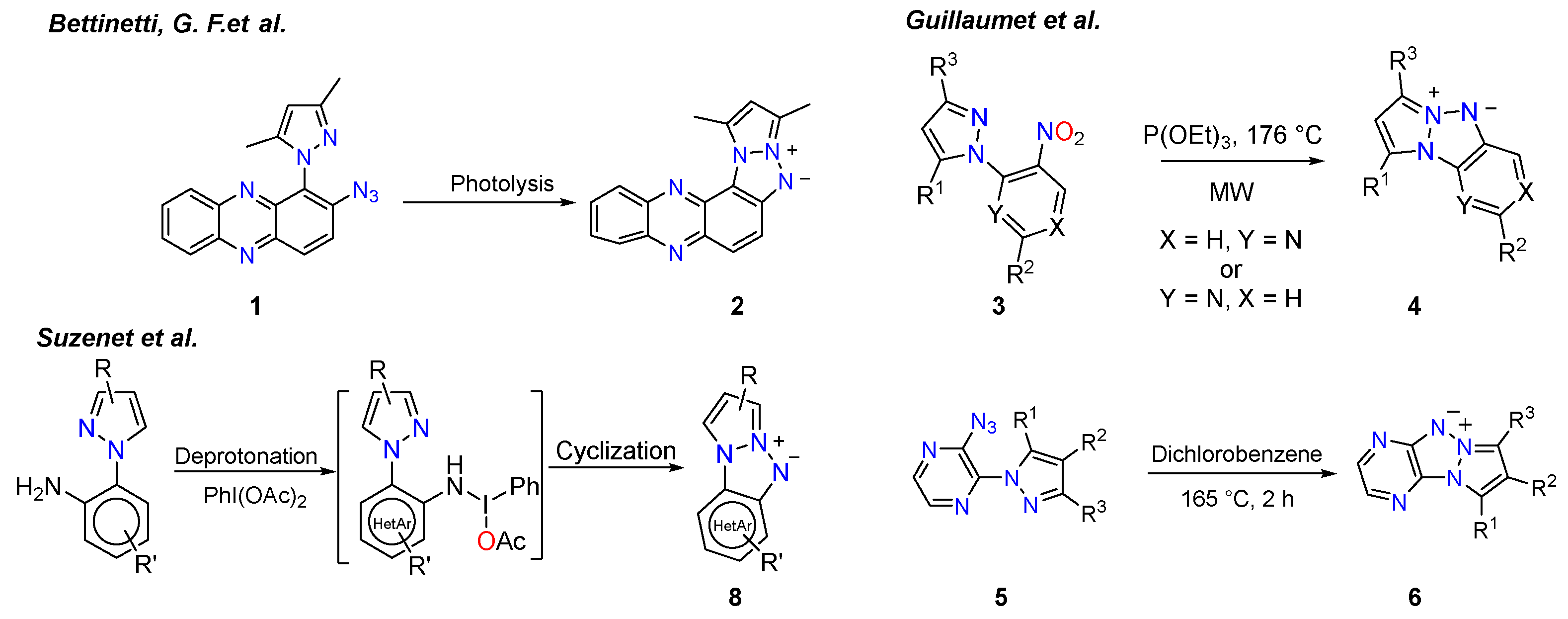

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

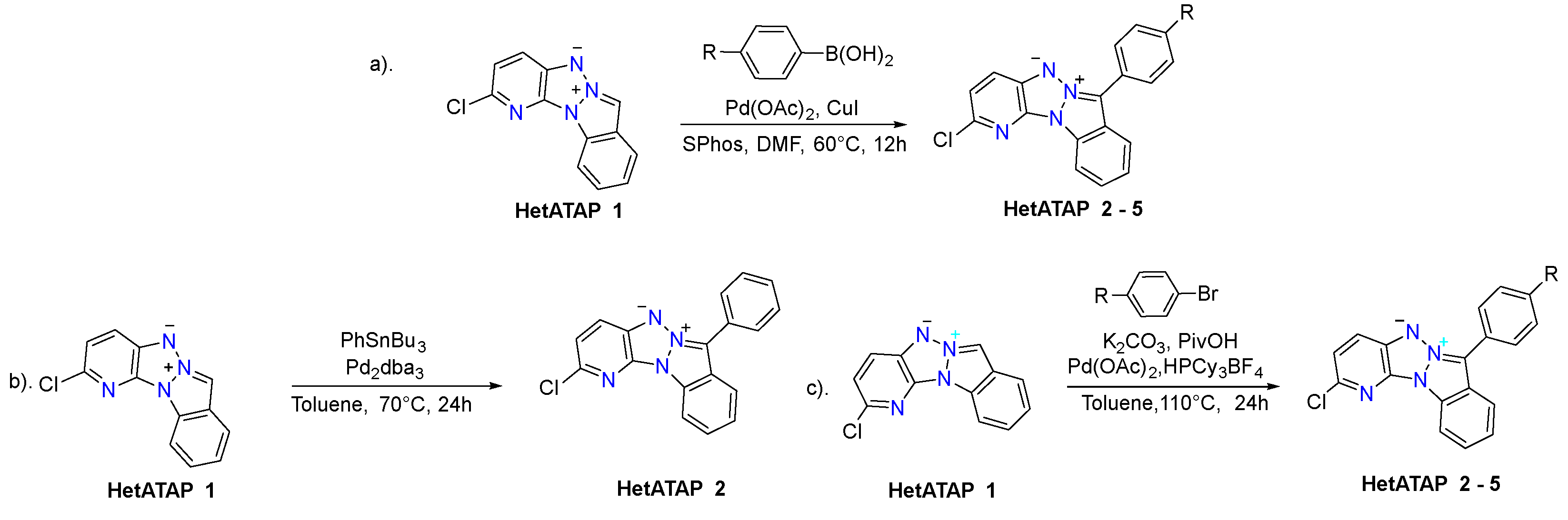

2.1. Synthesis

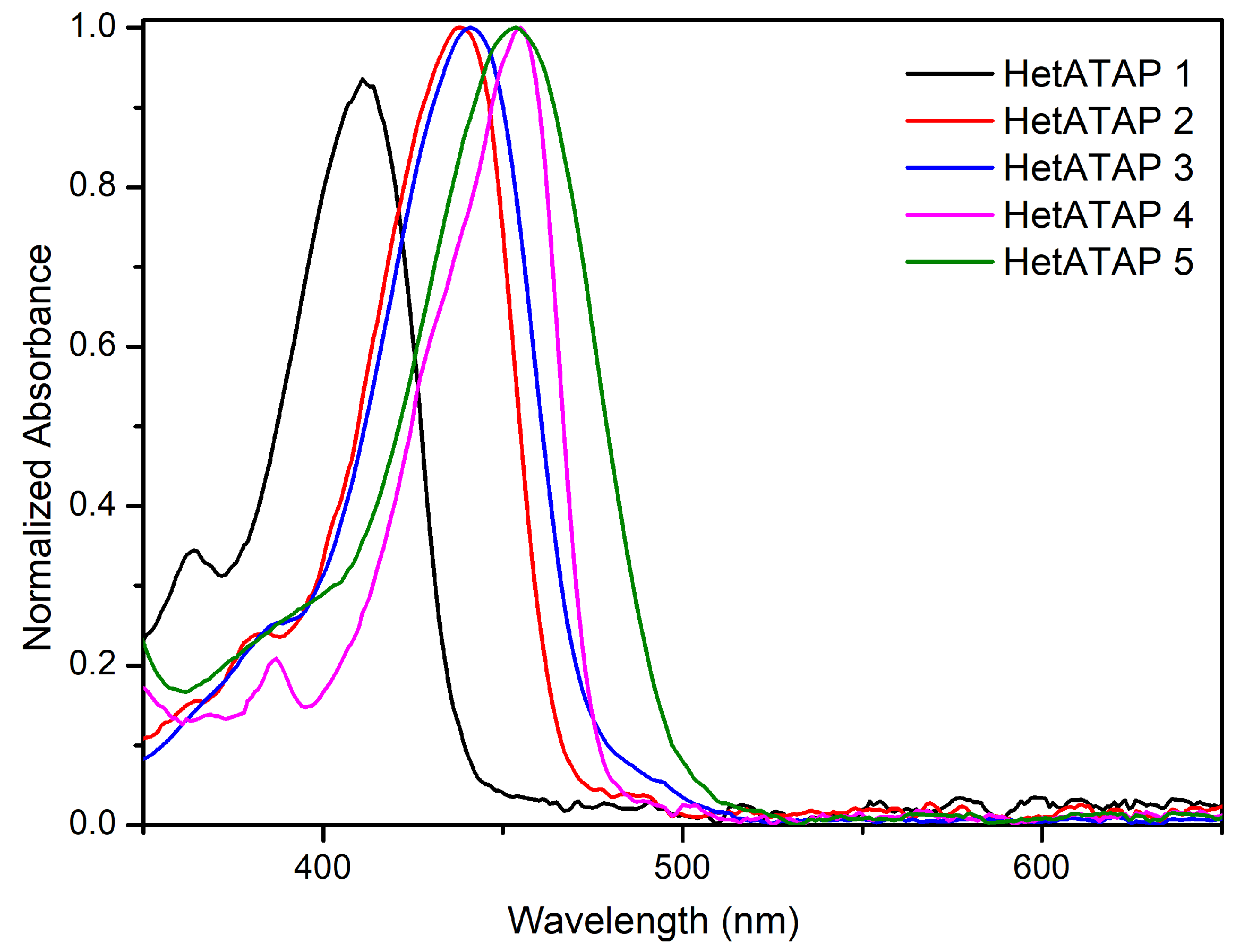

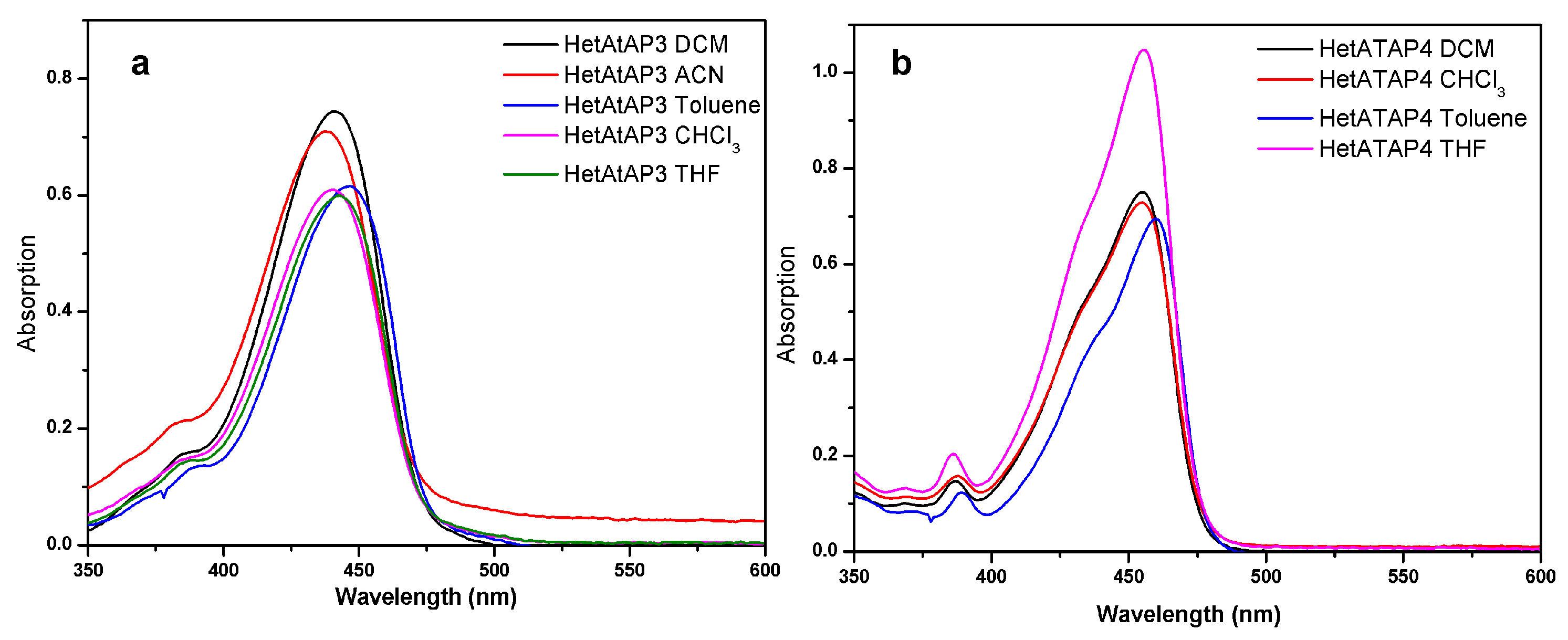

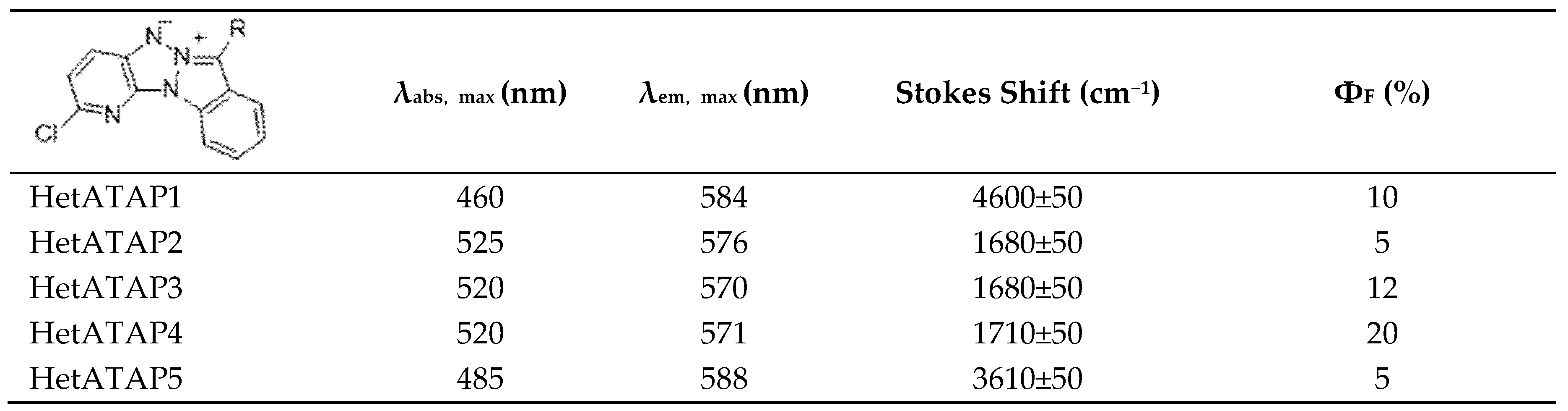

2.2. Photophysical Measurements

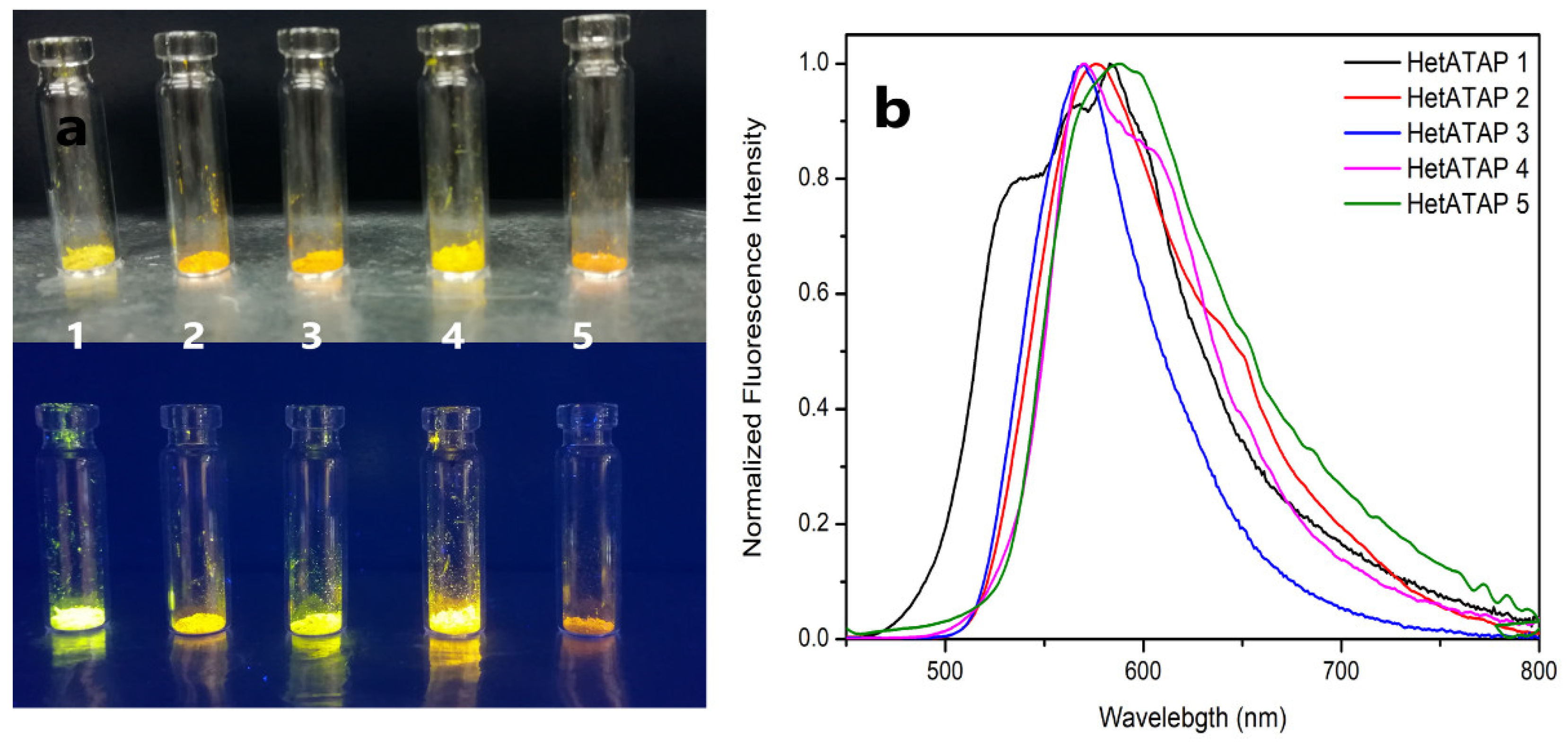

2.2.1. Fluorescence in the Solid-State

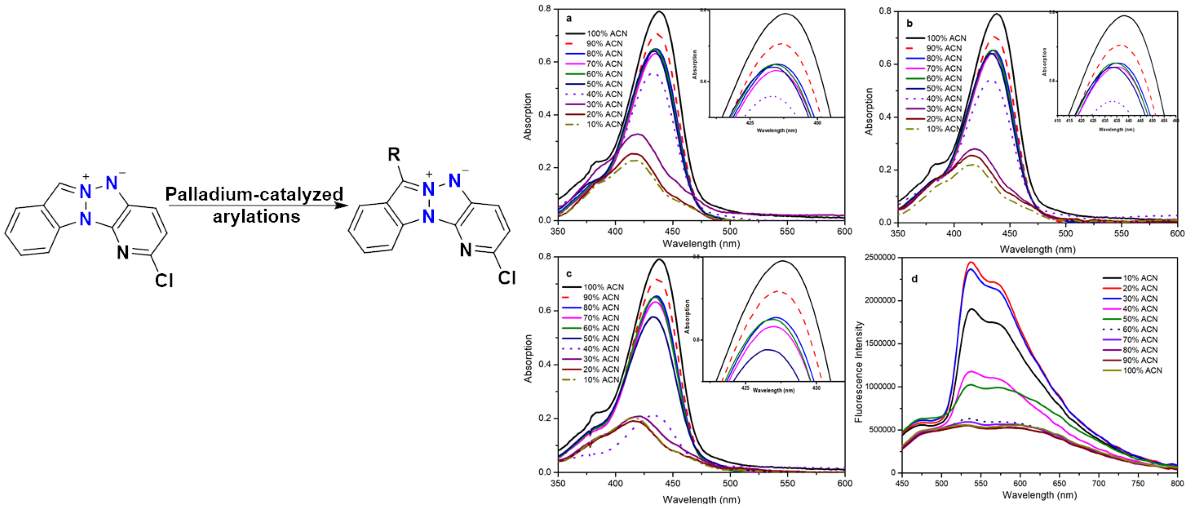

2.2.2. Fluorescence in Solution

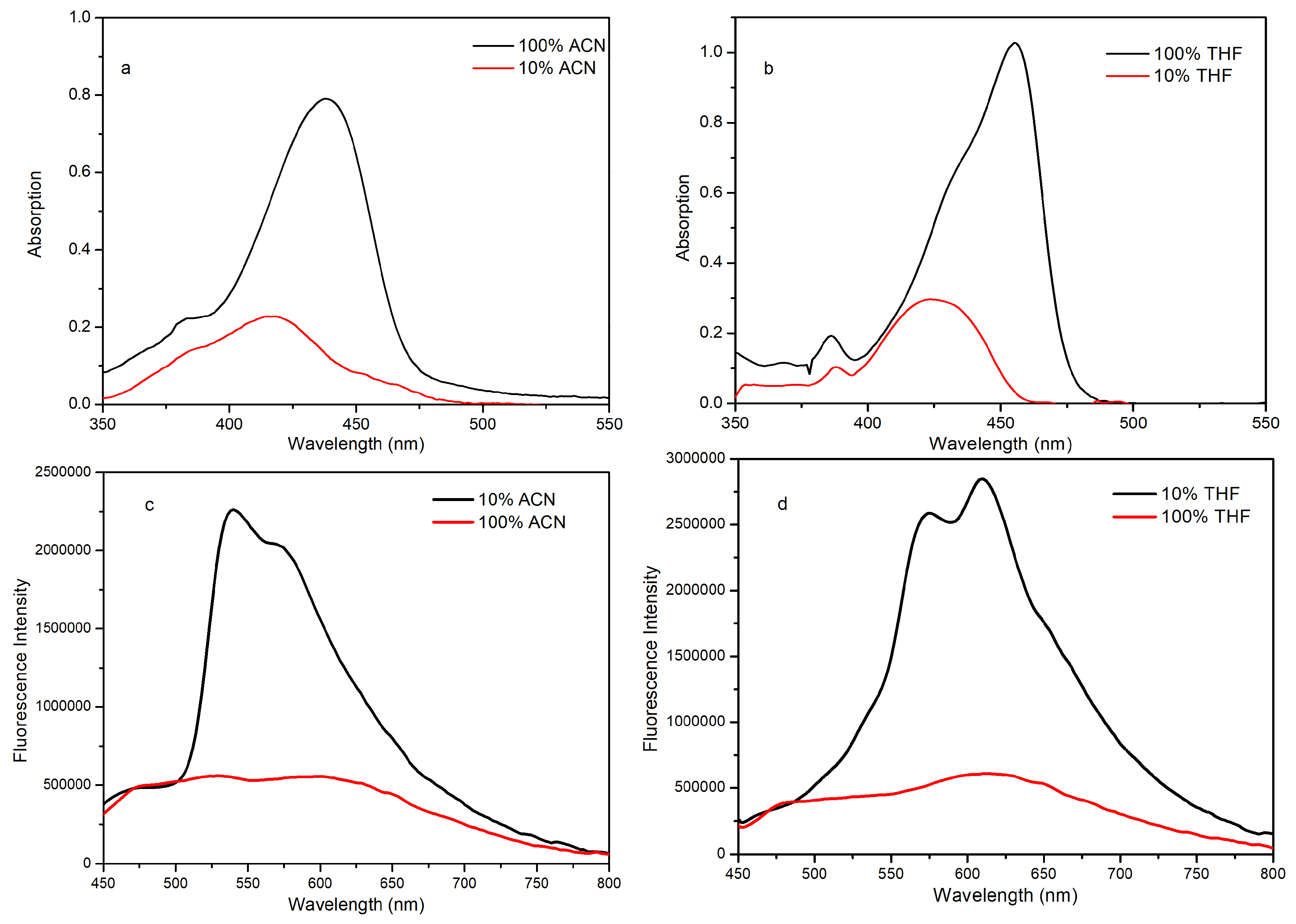

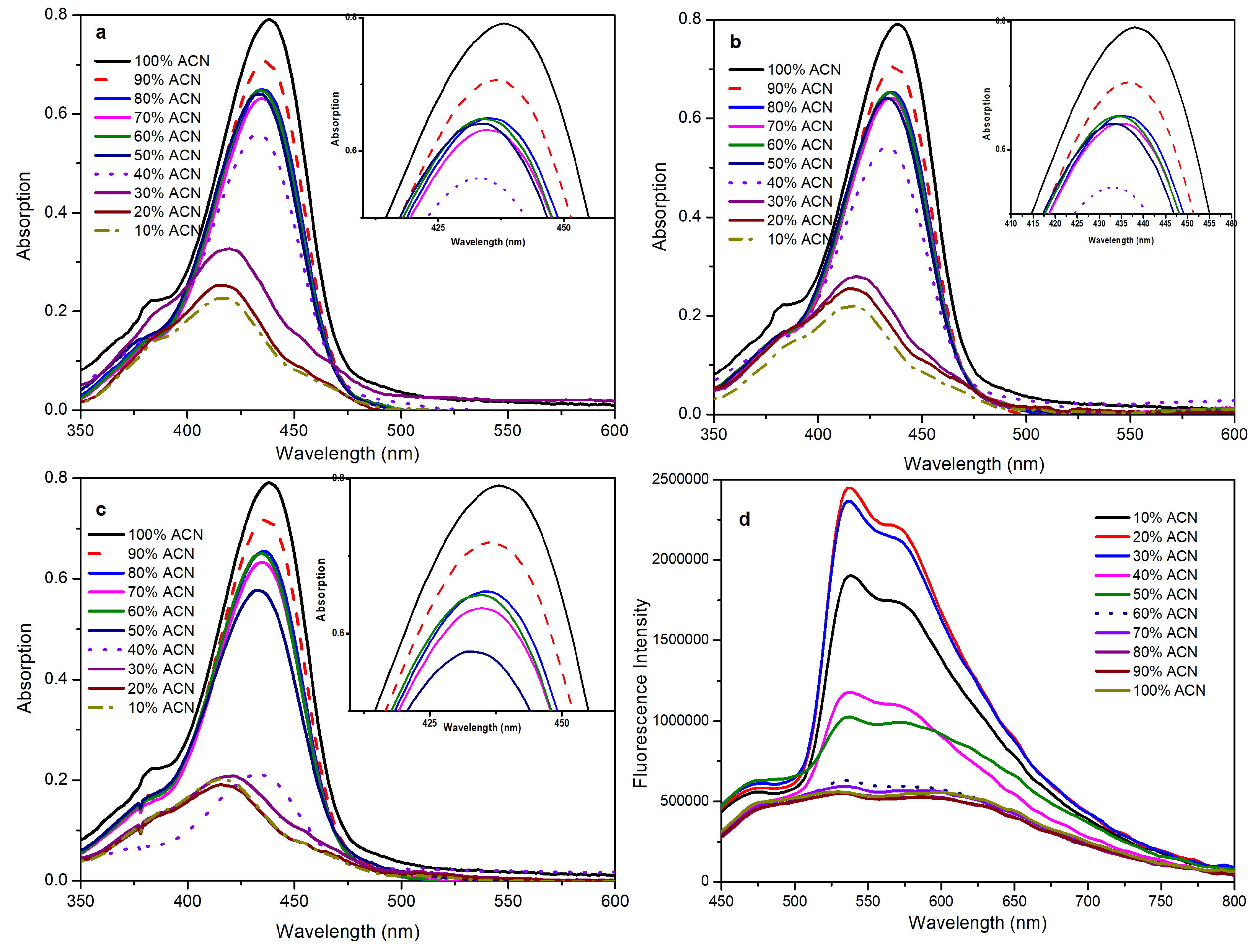

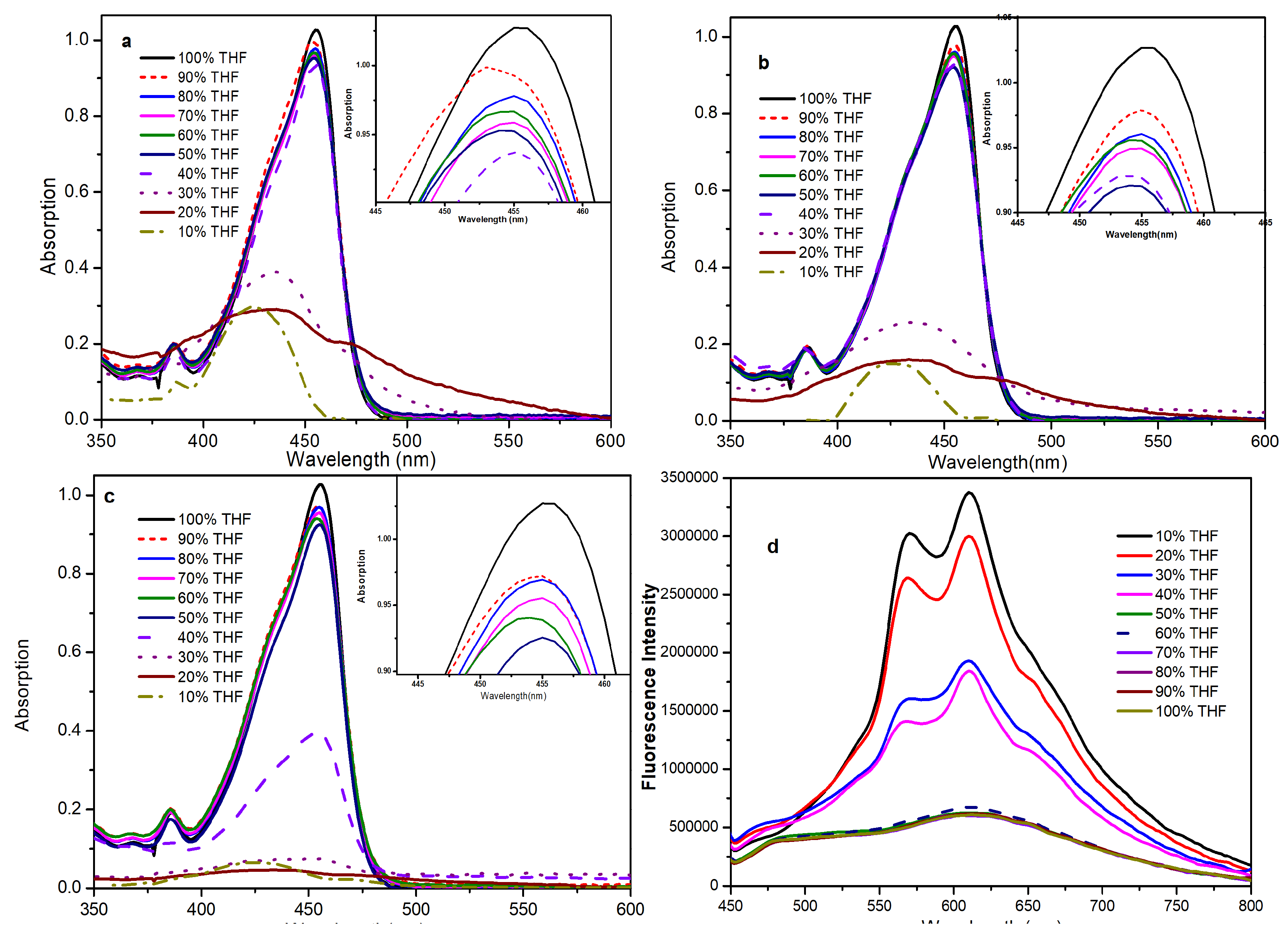

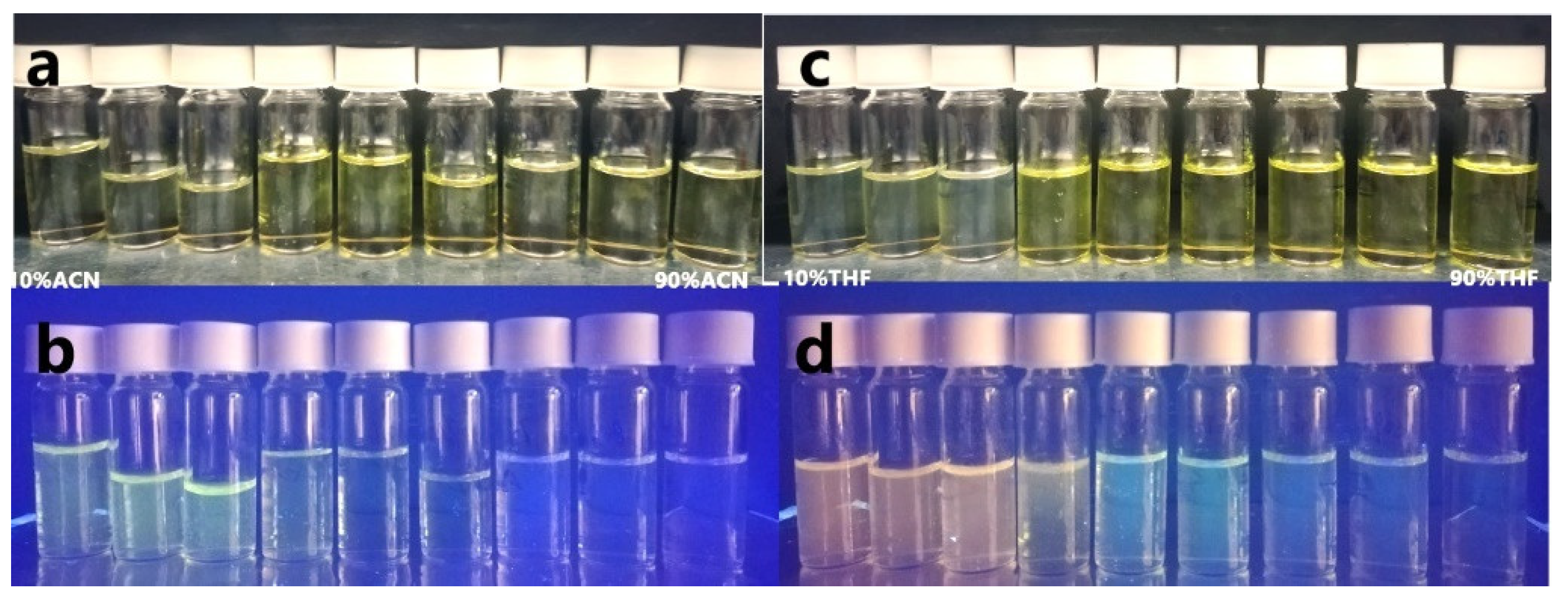

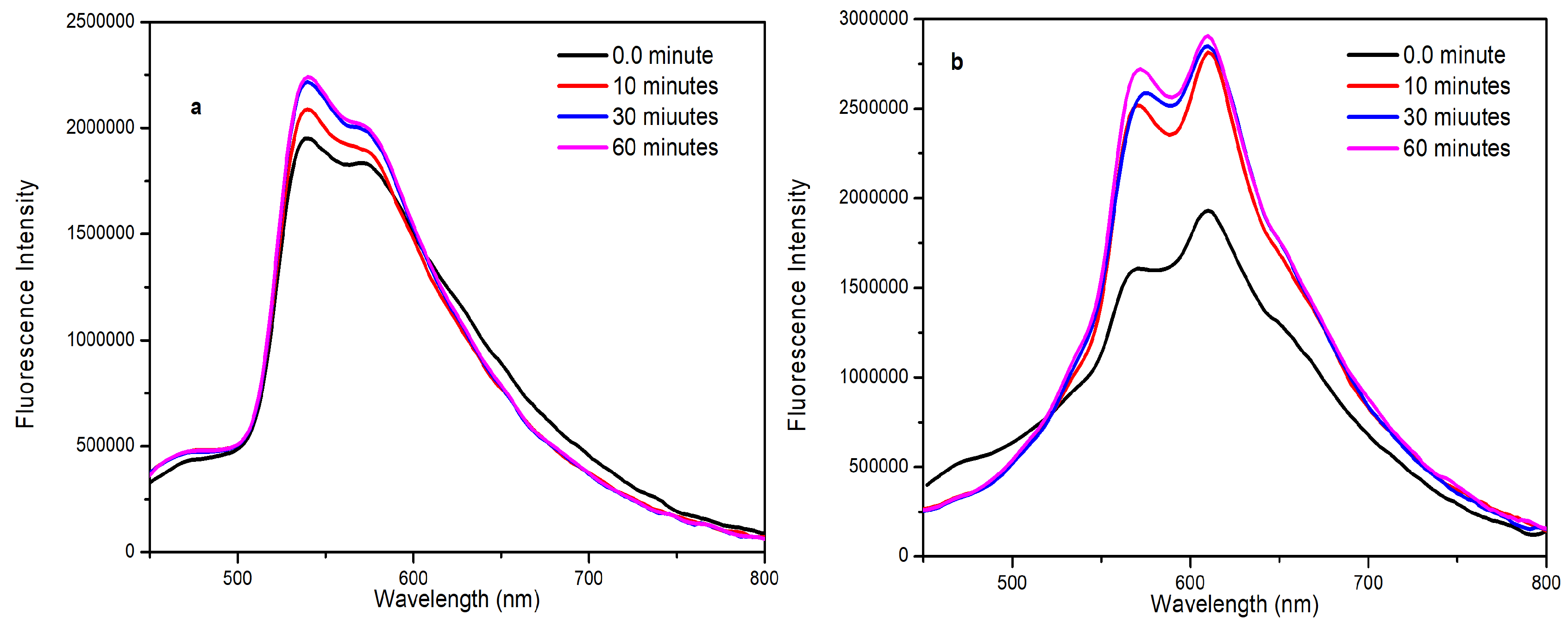

2.3. Fluorescence in the Aggregated State

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemical and Materials

3.2. Instrumentation

3.3. Synthesis

3.3.1. General Procedure for Suzuki Cross-Coupling Reaction

3.3.2. Stille Coupling Reaction of Compound HetATAP1

3.3.3. General Procedure for Palladium-Catalyzed CH Arylation

3.3.4. Experimental Details and Characterization Data

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang Y, Opsomer T, Dehaen W. Developments in the chemistry of 1,3a,6a-triazapentalenes and their fused analogs [Internet]. 1st ed. Vol. 137, Advances in Heterocyclic Chemistry. Elsevier Inc.; 2022. 25–70 p. [CrossRef]

- Nyffenegger C, Pasquinet E, Suzenet F, Poullain D, Guillaumet G. Synthesis of nitro-functionalized polynitrogen tricycles bearing a central 1,2,3-triazolium ylide. Synlett. 2009;3(8):1318–20.

- Nyffenegger C, Pasquinet E, Suzenet F, Poullain D, Jarry C, Léger JM, et al. An efficient route to polynitrogen-fused tricycles via a nitrene-mediated N-N bond formation under microwave irradiation. Tetrahedron. 2008;64(40):9567–73.

- González J, Santamaría J, Suárez-Sobrino ÁL, Ballesteros A. One-Pot and Regioselective Gold-Catalyzed Synthesis of 2-Imidazolyl-1-pyrazolylbenzenes from 1-Propargyl-1H-benzotriazoles, Alkynes and Nitriles through α-Imino Gold(I) Carbene Complexes. Adv Synth Catal. 2016;358(9):1398–403.

- Legentil P, Chadeyron G, Therias S, Chopin N, Sirbu D, Suzenet F, et al. Luminescent N-heterocycles based molecular backbone interleaved within LDH host structure and dispersed into polymer. Appl Clay Sci [Internet]. 2020;189(March):105561. [CrossRef]

- Daniel M, Hiebel MA, Guillaumet G, Pasquinet E, Suzenet F. Intramolecular Metal-Free N−N Bond Formation with Heteroaromatic Amines: Mild Access to Fused-Triazapentalene Derivatives. Chem - A Eur J. 2020;26(7):1525–9.

- Sirbu D, Diharce J, Martinić I, Chopin N, Eliseeva S V., Guillaumet G, et al. An original class of small sized molecules as versatile fluorescent probes for cellular imaging. Chem Commun. 2019;55(54):7776–9.

- Katritzky AR, Hür D, Kirichenko K, Ji Y, Steel PJ. Synthesis of 2, 4-disubstituted furans and 4, 6-diaryl-substituted 2, 3-benzo-1, 3a, 6a-triazapentalenes. Arkivoc. 2004;2:109–21.

- VOl N, Lynch BM, Hung YY. Pyrazolo [ 1,2-a] benzotriazole and Related Compounds (1). J Heterocycl Chem. 1965;2(1):218–9.

- Albini A, Bettinetti G, Minoli G. The effect of the p-nitro group on the chemistry of phenylnitrene. A study via intramolecular trapping. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 2. 1999;(12):2803–7.

- Albini BA, Bettinetti GF, Minoli G, Pietra S. Singlet Oxygen Photo-oxidation of some Triazapentalenes By. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1980;0(2904):2–6.

- Sirbu D, Diharce J, Martinić I, Chopin N, Eliseeva S V, Guillaumet G, et al. An original class of small sized molecules as versatile fluorescent probes for cellular imaging. Chem Commun [Internet]. 2019;55(54):7776–9. [CrossRef]

- Luo J, Xie Z, Xie Z, Lam JWY, Cheng L, Chen H, et al. Aggregation-induced emission of 1-methyl-1,2,3,4,5-pentaphenylsilole. Chem Commun. 2001;18:1740–1.

- Lian X, Sun J, Zhan Y. Dibenzthiophene and carbazole modified dicyanoethylene derivative exhibiting aggregation-induced emission enhancement and mechanochromic luminescence. J Lumin. 2023;263:120023.

- Zhuang Q, Zeng C, Mu Y, Zhang T, Yi G, Wang Y. Lead (II)-triggered aggregation-induced emission enhancement of adenosine-stabilized gold nanoclusters for enhancing photoluminescence detection of nabam—disodium ethylenebis (dithiocarbamate). Chem Eng J. 2023;470:144113.

- Liu D, Guo X, Wu H, Chen X. Aggregation-induced emission enhancement of gold nanoclusters triggered by sodium heparin and its application in the detection of sodium heparin and alkaline amino acids. Spectrochim Acta Part A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2024;304:123255.

- An Y, Li B, Yu Y, Zhou Y, Yi J, Li L, et al. A rapid and specific fluorescent probe based on aggregation-induced emission enhancement for mercury ion detection in living systems. J Hazard Mater. 2024;465:133331.

- Nelson M, Santhalingam G, Ashokkumar B, Ayyanar S, Selvaraj M. Aggregation induced emission enhancement (AIEE) receptor for the rapid detection of Cu2+ ions with in vivo studies in A549 and AGS gastric cancer cells. Microchem J. 2023;194:109294.

- Nurnabi M, Gurusamy S, Wu JY, Lee CC, Sathiyendiran M, Huang SM, et al. Aggregation-induced emission enhancement (AIEE) of tetrarhenium (I) metallacycles and their application as luminescent sensors for nitroaromatics and antibiotics. Dalt Trans. 2023;52(7):1939–49.

- Chen G, Wang J, Chen W, Gong Y, Zhuang N, Liang H, et al. Triphenylamine-functionalized multiple-resonance TADF emitters with accelerated reverse intersystem crossing and aggregation-induced emission enhancement for narrowband OLEDs. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33(12):2211893.

- Arshad M, AT JR, Joseph V, Joseph A. Selective detection of picric acid in aqueous medium using a novel naphthaldehyde-based aggregation induced emission enhancement (AIEE) active “turn-off” fluorescent sensor. J Lumin. 2023;258:119818.

- Turelli M, Ciofini I, Wang Q, Ottochian A, Labat F, Adamo C. Organic compounds for solid state luminescence enhancement/aggregation induced emission: a theoretical perspective. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2023;25(27):17769–86.

- Li S, Zhang H, Huang Z, Jia Q. Fluorometric and colorimetric dual-mode sensing of α-glucosidase based on aggregation-induced emission enhancement of AuNCs. J Mater Chem B. 2024;12(6):1550–7.

- Yin S, Peng Q, Shuai Z, Fang W, Wang Y hua, Luo Y. Aggregation-enhanced luminescence and vibronic coupling of silole molecules from first principles. Phys Rev B [Internet]. 2006;73:205409. Available from: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:121544093.

- Liu J, Lam JWY, Tang BZ. Aggregation-induced Emission of Silole Molecules and Polymers: Fundamental and Applications. J Inorg Organomet Polym Mater [Internet]. 2009;19(3):249–85. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Z, He B, Tang BZ. Aggregation-induced emission of siloles. Chem Sci. 2015;6(10):5347–65.

- Wang Z, Gu Y, Liu J, Cheng X, Sun JZ, Qin A, et al. A novel pyridinium modified tetraphenylethene: AIE-activity, mechanochromism, DNA detection and mitochondrial imaging. J Mater Chem B. 2018;6(8):1279–85.

- Dong Y, Lam JWY, Qin A, Liu J, Li Z, Tang BZ, et al. Aggregation-induced emissions of tetraphenylethene derivatives and their utilities as chemical vapor sensors and in organic light-emitting diodes. Appl Phys Lett. 2007;91(1).

- Ito F, Fujimori J ichi, Oka N, Sliwa M, Ruckebusch C, Ito S, et al. AIE phenomena of a cyanostilbene derivative as a probe of molecular assembly processes. Faraday Discuss. 2017;196:231–43.

- Ito F, Fujimori J ichi, Oka N, Sliwa M, Ruckebusch C, Ito S, et al. AIE phenomena of a cyanostilbene derivative as a probe of molecular assembly processes. Faraday Discuss. 2016 Nov 30;196.

- Bhongale CJ, Chang CW, Lee CS, Diau EWG, Hsu CS. Relaxation dynamics and structural characterization of organic nanoparticles with enhanced emission. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109(28):13472–82.

- Itami K, Ohashi Y, Yoshida JI. Triarylethene-based extended π-systems: Programmable synthesis and photophysical properties. J Org Chem. 2005;70(7):2778–92.

- Ziółek M, Filipczak K, Maciejewski A. Spectroscopic and photophysical properties of salicylaldehyde azine (SAA) as a photochromic Schiff base suitable for heterogeneous studies. Chem Phys Lett. 2008;464(4–6):181–6.

- Arcovito G, Bonamico M, Domenicano A, Vaciago A. Crystal and molecular structure of salicylaldehyde azine. J Chem Soc B Phys Org. 1969;733–41.

- Sirbu D, Chopin N, Martinić I, Ndiaye M, Eliseeva S V., Hiebel MA, et al. Pyridazino-1,3a,6a-triazapentalenes as versatile fluorescent probes: Impact of their post-functionalization and application for cellular imaging. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(12):1–10.

- Wang Y, Opsomer T, de Jong F, Verhaeghe D, Mulier M, Van Meervelt L, et al. Palladium-Catalyzed Arylations towards 3,6-Diaryl-1,3a,6a-triazapentalenes and Evaluation of Their Fluorescence Properties. Molecules. 2024;29(10).

- Gorelsky SI, Lapointe D, Fagnou K. Analysis of the concerted metalation-deprotonation mechanism in palladium-catalyzed direct arylation across a broad range of aromatic substrates. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(33):10848–9.

- Zheng J, Huang F, Li Y, Xu T, Xu H, Jia J, et al. The aggregation-induced emission enhancement properties of BF2 complex isatin-phenylhydrazone: Synthesis and fluorescence characteristics. Dye Pigment. 2015;113:502–9.

- Turchini GM, Ng WK, Tocher DR. Fish oil replacement and alternative lipid sources in aquaculture feeds. CRC Press; 2010.

- Zhang Y, Qi X, Cui X, Shi F, Deng Y. Palladium catalyzed N-alkylation of amines with alcohols. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52(12):1334–8.

| HetATAP | R | Yield (%) | ||

| a | b | c | ||

| 2 | H | 53 | 13 | 66 |

| 3 | OMe | 47 | -a | 62 |

| 4 | COOEt | 35 | -a | 51 |

| 5 | N(Me)2 | 30 | -a | 73 |

|

| Dye | Matrix | λabs,max (nm) | ɛ(dm3 mol⁻¹ cm⁻¹) | λem,max (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HetATAP3 | DCM | 441 | 39, 194 | 604 |

| CHCl3 | 440 | 30, 454 | 610 | |

| ACN | 438 | 35, 482 | 606 | |

| Toluene | 447 | 30, 799 | 610 | |

| THF | 443 | 29, 989 | 614 | |

| Solid | 570 | |||

| HetATAP4 | DCM | 455 | 37, 524 | 616 |

| CHCl3 | 455 | 36, 420 | 622 | |

| Toluene | 460 | 34, 741 | 606 | |

| THF | 456 | 52, 373 | 642 | |

| Solid | 571 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).