1. Introduction

Phenothiazines are an interesting class of heterocyclic compounds possessing a tricyclic dibenzo-[

1,

4]-thiazine ring system with high therapeutical potential [

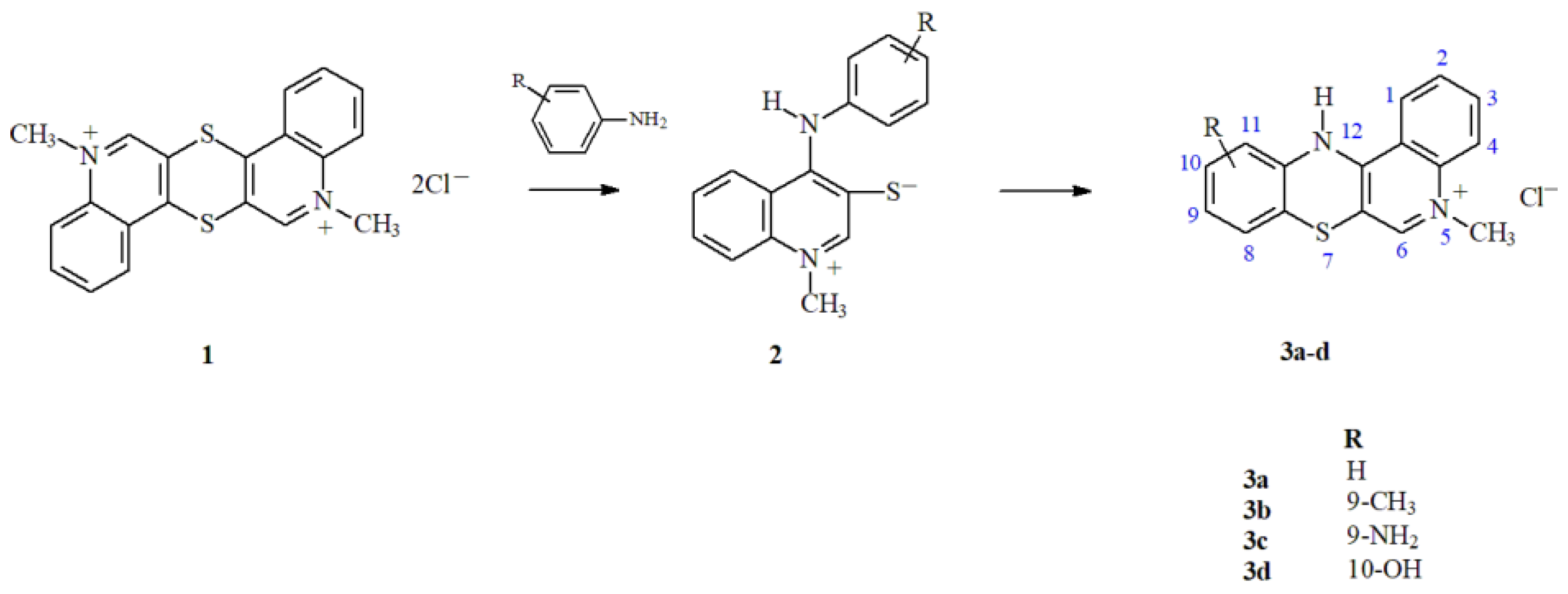

1]. Even more effective in treatment of anticancer diseases may be phenothiazine derivatives. In an earlier work, a unique, original method for the synthesis of azaphenothiazine derivatives was presented [

2]. This method allows the formation of derivatives containing specific substitutes at different positions of the tetracyclic quinobenzothiazinium system. The method involves the reaction of thioquinanthrenediinium bis-chloride (1) with substituted isomeric anilines. The intermediate product of these reactions is a betaine system with the structure of 1-methyl-4-(phenylamino)quinoline-3-thiolate (2), the cyclization of which leads to the formation of a thiazine ring (

Scheme 1). The control of the parameters of the cyclization reaction enables its selective course and allows the unique introduction of various types of substitutes in the 9, 10 and 11 positions of the quino[3,4-b][

1,

4]benzothiazine scaffold. Using this synthetic method, derivatives 3a-d containing different types of substituents (CH

3, NH

2, OH) in the quinobenzothiazinium system were obtained.

The activity of the obtained 5-methyl-12

H-quino[3,4-

b][

1,

4]benzothiazinium chlorides (

Scheme 1) was investigated

in vitro using cultured human colon carcinoma (Hct11) and Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cell lines [

2]. The obtained results demonstrated a structure activity relationship. The greatest activity was shown by the compound with substituents in 9- and 10-position of the quinobenzothiazine ring and by the compound which does not feature any additional substituents. However, along with development of novel compounds with anticancer potential, it is also necessary to develop an appropriate drug delivery system (DDS). The use of systemic anticancer chemotherapy is limited by its toxicity, because small doses of drug after systemic administration reach effective intratumoral concentrations, while high doses with significant tumor inhibition effects may also increase toxicity to healthy cells [

3]. Therefore, various strategies based on DDS for avoiding the systemic toxicity have been designed. They should protect drugs from early elimination, control drug release, increase tumor exposure to anticancer drugs by extending their circulation time or steadily releasing drugs into the tumor sites.

One of the most extensively studied types of carriers of anticancer drugs are nanoparticles (NP). Compared to conventional drugs, nanoparticle-based DDS have shown many advantages in cancer treatment, such as improved pharmacokinetics, stability, biocompatibility, enhanced permeability and retention effect, reduction of side effects and drug resistance [

4]. However, development of the optimal DDS is a quite complex and needs considering many factors that have an impact on their functionality [

5,

6]. We have selected two types of NP – nanospheres (NS) and micelles (M) obtained from PLA-based polymers for discovering their potential for delivery of four types of phenothiazine derivatives (3a-d,

Scheme 1). The NS are defined as homogenous matrix systems wherein a dispersed or dissolved active compound is entrapped within the polymeric matrix structure through the solid sphere [

7]. Loading of drug(s) into the NS enables local drug delivery, because during a specific time period, these nanostructures undergo slow hydrolytic degradation, disintegration of the matrix and sustained release of the drug. NS have small particle size and thus, they are suitable to be administered orally, locally, and systemically. Most NS are prepared using polymers that are biodegradable and biocompatible. Currently, NP obtained from poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA), a US FDA approved biocompatible polymer, has been widely explored [

8]. Aliphatic polyesters characterize biocompatibility and tailorable degradation rate (e.g. by molar mass, composition and copolymer microstructure). The main advantage of aliphatic polyesters such as PLGA is their hydrolytic degradation to the products that are naturally present in human body (e.g. lactic acid and glycolic acid) [

9].

Polymeric micelles are another example of nanocarriers extensively studied for anticancer drug delivery and some of them have already been applied in different stages of clinical trials [

10]. Polymeric micelles are the nano-scaled sized particles (5–200 nm), which are self-assembled by amphiphilic polymers. They consist of the inside hydrophobic core and hydrophilic part on the outside (shell). Therefore, the hydrophobic core can serve as a solubilization depot for agents with poor aqueous solubility. The hydrophilic shell provides advantages including longer blood circulation time and increased stability in the blood

[10-12]. Particularly, micelles obtained from poly(lactide)-polyethylene glycol (PLA–PEG) have been considered as drug delivery, because the PEG shell effectively prevents the adsorption of proteins and phagocytes, thereby evidently extending the blood circulation period and the hydrophobic PLA core can effectively encapsulate many therapeutic agents [

10,

13,

14]. Micelles have many advantages over other types of nano-assemblies, including processability, simple architecture, drug solubilization, improved biocompatibility, pharmacokinetics, and biodistribution, and more engineering possibilities [

15].

The aim of the study was evaluation of two types of nanopartciles – nanospheres and micelles obtained from PLA-based polymers for discovering their potential for delivery of four types of 5-methyl-12

H-quino[3,4-

b][

1,

4]benzothiazinium chlorides with anticancer potential (

Scheme 1). Our previous study showed that the functionality of the PLA-based injectable delivery systems strongly depends on the type of DDS and their polymeric composition [

16].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Nanoparticles

Preparation of nanospheres

Drug-free and drug-loaded NS were prepared by emulsification technique. Poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) synthesized in bulk with the use of Zr(Acac)

4 as non-toxic initiator was used to form NS. Briefly, 125 mg of polymer was dissolved in 4 mL of methylene chloride. 15 mg of drug (5-methyl-12

H-quino[3,4-

b][

1,

4]benzothiazinium chlorides: 3a, 3b, 3c or 3d) was dissolved in mixture of methylene chloride and methanol (2:1 v/v). The drug solution and polymer solution were mixed and added dropwise to 50 mL of ice-cold 5% polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) solution (w/v) and emulsified at 20 500 rpm for 2 min. The emulsion was gently stirred at room temperature (RT) to evaporate methylene chloride overnight. The NS were collected by centrifugation at 10 000 rpm for 10 min. Then, they were washed three times with deionized water following centrifugation at 5 000 rpm. The final NS were lyophilized and stored at 4 °C until further analysis.

The obtained nanospheres were marked as NS - drug-free nanospheres and NS/3a, NS/3b, NS/3c or NS/3d – nanospheres loaded with 3a, 3b, 3c or 3d, respectively.

Preparation of micelles

The micelles (M) were obtained from poly(L-lactide)-polyethylene glycol (PLLA-PEG) (RuixiBiotech Co. Ltd) by co-solvent evaporation method [

17]. The number-average molar mass (Mn) of PLLA was 3000 Da and the Mn of PEG block was 5000 Da. The polymer was dissolved in chloroform (5 w/v %) and mixed with 5 mL of deionized water under vigorous stirring. The micellar solutions were left at RT for 24 h for solvent evaporation. The blank micelles were filtered through syringe filters (0.8 μm) to remove the precipitated polymer, frozen at -80°C and lyophilized.

To encapsulate a drug (3a, 3b, 3c or 3d) in micelles, each compound was dissolved in ethanol (2 w/v%) and 50 μL of drug solution was added to micellar solution and stirred magnetically. The initial (theoretical) drug content was 20 w/w%. The vials were left at RT for 24 h for solvent evaporation in a laminar box. Subsequently, the solution was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min. to separate unloaded drugs. The supernatant was collected, frozen, lyophilized and stored at 4°C for further analysis.

The obtained micelles were marked as M - drug-free micelles and M/3a, M/3b, M/3c or M/3d – micelles loaded with 3a, 3b, 3c or 3d, respectively.

2.2. Microscopic Analysis

The morphology of the freeze-dried NS was observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM; FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR, USA; Quanta 250 FEG). Powder samples were stuck to the microscopic stubs by the double-sided adhesive carbon type. The micrographs were obtained under low vacuum (80 Pa) with an acceleration voltage 5 kV from secondary electrons collected by a Large Field Detector (LFD).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of micelles were obtained by means of a Tecnai F20 X TWIN microscope (FEI Company) equipped with field emission gun (acceleration voltage of 200 kV). Images were recorded on the Gatan Rio 16 CMOS 4 k camera (Gatan Inc.). The Gatan Microscopy Suite software (Gatan Inc.) was used for the processing of images. 6 μL of the micellar solution was placed on a copper grid covered with carbon film and air dried at RT before measurements.

2.3. Drug Encapsulation Properties and In Vitro Release study

The loading content (LC) was calculated from the following equation: LC [%] = (weight of the drug / weight of the drug-loaded NS or M) x 100. The drug-loaded NS or M were dissolved in the DMSO and analyzed spectrophotometrically at the Spark 10M multiplate reader (Tecan). The 3a was analyzed at 298 nm, 3b at 480 nm, 3c at 514 nm and 3d at 303nm.

Drug release from NS

5 mg of the drug-loaded NS was suspended in 15 mL of phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4) using 15 mL screw-capped tubes and incubated at 37 °C under constant rotation (Loopster digital rotating shaker, IKA). At the specified time point the samples were centrifuged (12 000 rpm for 15 min at 20 °C), the supernatants were removed and the precipitate (NS) was saved for analysis of the remaining drug. For this purpose, the modified extraction method was used [

18]. Briefly, the NS remaining after each incubation period were dissolved in the DMSO and analyzed spectrophotometrically at the Spark 10M multiplate reader (Tecan). The experiment was conducted in triplicate.

Drug Release From Micelles

The dialysis method was used for analysis of drug from micelles. The lyophilized micelles (2 mg/mL) were dispersed in PBS (pH 7.4). 1 mL of the micellar solution was placed in a dialysis device (Float-A-Lyzer G2, MWCO of 3.5–5 kDa; Spectra/Por). The dialysis was conducted against PBS (15 mL). The collected samples were lyophilized, dissolved in DMSO and before quantitative assessment of the drug by spectrophotometric measurements at the multiplate reader (Spark®, Tecan). The experiment was conducted in triplicate.

2.4. Cytotoxicity Study

The cytocompatibility o the blank NS and M was studied according to the ISO 10993-5 standard with the use of L-929 mouse fibroblast cell line (CCL-1, ™, American Type Culture Collection). The cytotoxic activity of native drugs, drug loaded-NS and drug-loaded M was studied against human cervical carcinoma HeLa cell line (CCL-2™, American Type Culture Collection). L-929 and HeLa cells were cultured in Eagle's Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM) supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum. The experimental medium was additionally supplied with a 10 mM HEPES. The cells were maintained at 37 °C, in a humidified atmosphere containing 5 % CO2.

CCK-8 assay

For analysis of cytotompatibility of drug-free NS and M and cytotoxic activity of the free drugs and developed nanoformulations, 100 μL of cell suspension, containing 2x10

3 cells, was transferred to wells of the 96-well plates and cultured in standard medium for 24 hours. Then, the medium was exchanged to the medium containing the tested formulations, which were prepared directly before experiment. The free drug was prepared by dissolution in DMSO (stock solution) and addition to the medium to obtain the final concentration range of 3a, 3b, 3c and 3d from 0.4 – 32 µg/mL. The final concentration of DMSO in the samples was below 0.4 %. It has been confirmed that the concentration of DMSO below 1 % does not affect the viability of HeLa cells [

12,

19]. The NS and M were directly suspended in EMEM and diluted in the range of 63.0 – 500 µg/mL or 2.0 – 500 µg/mL, respectively. The concentration of drug in NS and M is presented in

Table 1. The cells were incubated with the tested samples for 72 hours. Untreated cells were used as negative control and cells treated with 5 % of DMSO as positive control. The viability of cells was evaluated with the use of Cell Counting Kit – 8 (CCK-8). Absorbance was read at 450 nm (reference: 650 nm) at the Spark 10M (Tecan).

Sulforhodamine B assay

The In Vitro Toxicology Assay Kit, Sulforhodamine B (SRB) based (Sigma Aldrich) was used to study the viability by measuring of total biomass by staining cellular proteins with SRB. The HeLa cells were seeded in 96-well plates at the density of 2x103 per well in 100 μL of medium and cultured for 24 h. Then, the medium was removed and replaced with a fresh one (200 μL), containing blank micelles at a concentration range of 64, 125, 250 and 500 μg/mL or 3d-loaded micelles (M/3d) at the range of concentration of 2-500 μg/mL. The cells were incubated with the tested samples for 72 h. Subsequently, the culture medium was removed and cells were fixed at 4 °C with 10 % trichloroacetic acid, washed with deionized water and stained with SRB. According to the protocol of the SRB assay, the absorbance was read at 570 and 690 nm (reference wavelength) using the Spark 10M microplate reader (Tecan).

LDH assay

The cytotoxicity of M/3d was analyzed also by measuring activity of lactate dehydragenase (LDH) (Cytotoxicity LDH Assay Kit). The cell culture was prepared in the same way as for CCK-8 assay. Apart cells cultured with M/3d at the concentration of 2-500 μg/mL for 24 h, two kinds of the control groups were prepared. One set of cell culture wells was lysed by addition of 10 μL of Lysis Solution to determine the Maximum LDH Release. The second set of cell culture wells was used to determine the Spontaneous LDH release by addition of 10 μL of medium. The percent of cytotoxicity was determined by the following equation: Cytotoxicity (%) = [(X-Z)/(Y-Z)] × 100%, where X: Absorbance of Samples - Background Blank; Y: Absorbance of High Control - High Blank Control; Z: Absorbance of Low Control - Background Blank

BrdU assay

The bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assay (the Cell Proliferation ELISA, BrdU colorimetric kit; Roche) was used for the analysis of the rate of DNA synthesis. The HeLa cells were seeded in 96-well plates at the density of 4x103 per well in 100 μL of medium and cultured

in standard conditions for 24 h. Then, the medium was removed and replaced with a fresh one (200 μL), containing blank micelles at a concentration range of 64, 125, 250 and 500 μg/mL or 3d-loaded micelles (M/3d) at the range of concentration of 2-500 μg/mL. The cells were incubated with the tested samples for 72 h. Subsequently, the culture medium was removed and FixDenat was added to fix the cells and denature DNA. The amount of BrdU retained in cells was evaluated according to the protocol. Absorbance was measured at 370 and 492 nm (reference wavelength) with the use of the Spark 10M microplate reader (Tecan).

Statistical analysis

The results were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey post hoc test. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.5. Hemolysis Assay

Hemolysis assay was conducted for drug free NS (NS), drug free micelles (M), drug-loaded NS (NS/3a, NS/3b, NS/3c and NS/3d) and drug-loaded micelles (M/3a, M/3b, M/3c and M/3d) according to the procedure described by Sæbø et al. [

20]. The study was conducted after receiving approval of Bioethical Commission of the Medical University of Silesia No. BNW/NWN/0052/KB1/25/24). A 10 % Triton X-100 was used as a positive control (C+) and PBS pH~7 as a negative control (C-) in identical volumes as test compounds. The blood from healthy volunteers was collected in lithium heparin tubes and centrifuged at 1700× g for 5 min. The supernatant was removed by aspiration and erythrocytes were washed by addition of 2 mL of PBS pH~7 and centrifuged. The washing step was repeated three times until supernatant was clear. Then, the supernatant was removed and the erythrocyte pellet was diluted 1:100 in PBS pH~7 to obtain a 1 % erythrocyte suspension. The 500 μL of erythrocyte suspension was mixed with 500 μL of the tested compound and incubated at 37 °C for 60 min. The samples were centrifuged and 250 μL of the supernatant was transferred to a transparent, flat-bottom 96-well plate to measure absorption at 405 nm in a Spark 10M microplate reader (Tecan).

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Characteristics of the NPs

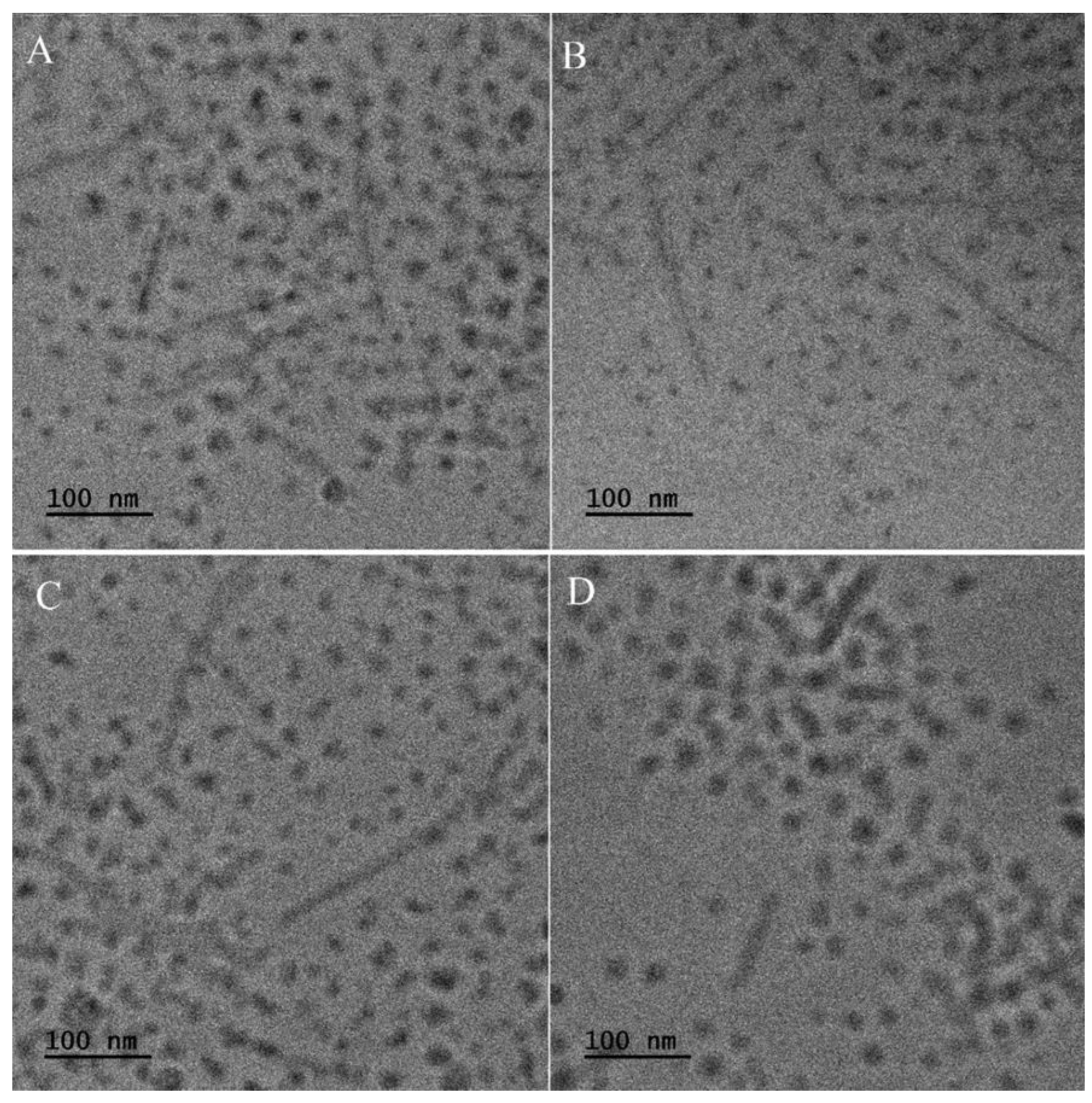

Two kinds of NPs with phenothiazine derivatives have been developed – nanospheres and micelles. The morphology of NS loaded with 3a, 3b, 3c and 3d, observed in SEM, is presented in

Figure 1. All kinds of NS characterize very regular spherical shape with smooth surface and the average diameter of ≈ 870 nm. Thus, it may be concluded that the size and morphology of NS does not depend on the type of encapsulated active compound. Similarly, no differences in size and morphology have been observed for phenothiazine derivatives-loaded micelles (

Figure 2). In all cases, two types of micelles have been formed with spherical and elongated shape. The micelles possess the diameter of ≈ 25 nm and the length of elongated nanocarriers is ≈ 150 nm.

3.2. Drug Loading and Release Properties

The loading content of 3a, 3b, 3c and 3d in nanospheres and micelles is presented in Table 2. It can be observed that the drug loading properties differ significantly depending on the type of NP. Generally, the LC of all phenothiazine derivatives in NS is significantly lower than the LC of micelles. The highest loading capacity was observed for NS with 3d (3.07%) and the lowest for 3a (0.75%). In the case of micelles, the LC is similar for 3a, 3c and 3d (≈21%) and slightly lower for 3b.

Drug release was studied under

in vitro environment. The drug release from NS was very insignificant and below detection even after 30 days of incubation. The release process from micellar formulations proceeded much faster, as presented in

Figure 3, because after 24h even 50% of drug was released from M/3d and 33% from M/3a. The slowest release was observed for M/3b and M/3c.

Table 1.

Drug loading capacity of the nanospheres and micelles.

Table 1.

Drug loading capacity of the nanospheres and micelles.

| Name of drug delivery system |

LC [%] |

| NS/3a |

0.75 ± 0.07 |

| NS/3b |

2.74 ± 0.13 |

| NS/3c |

1.82 ± 0.10 |

| NS/3d |

3.07 ± 0.17 |

| M/3a |

21.74 ± 1.34 |

| M/3b |

18.51 ± 0.49 |

| M/3c |

21.15 ± 0.45 |

| M/3d |

21.40 ± 1.11 |

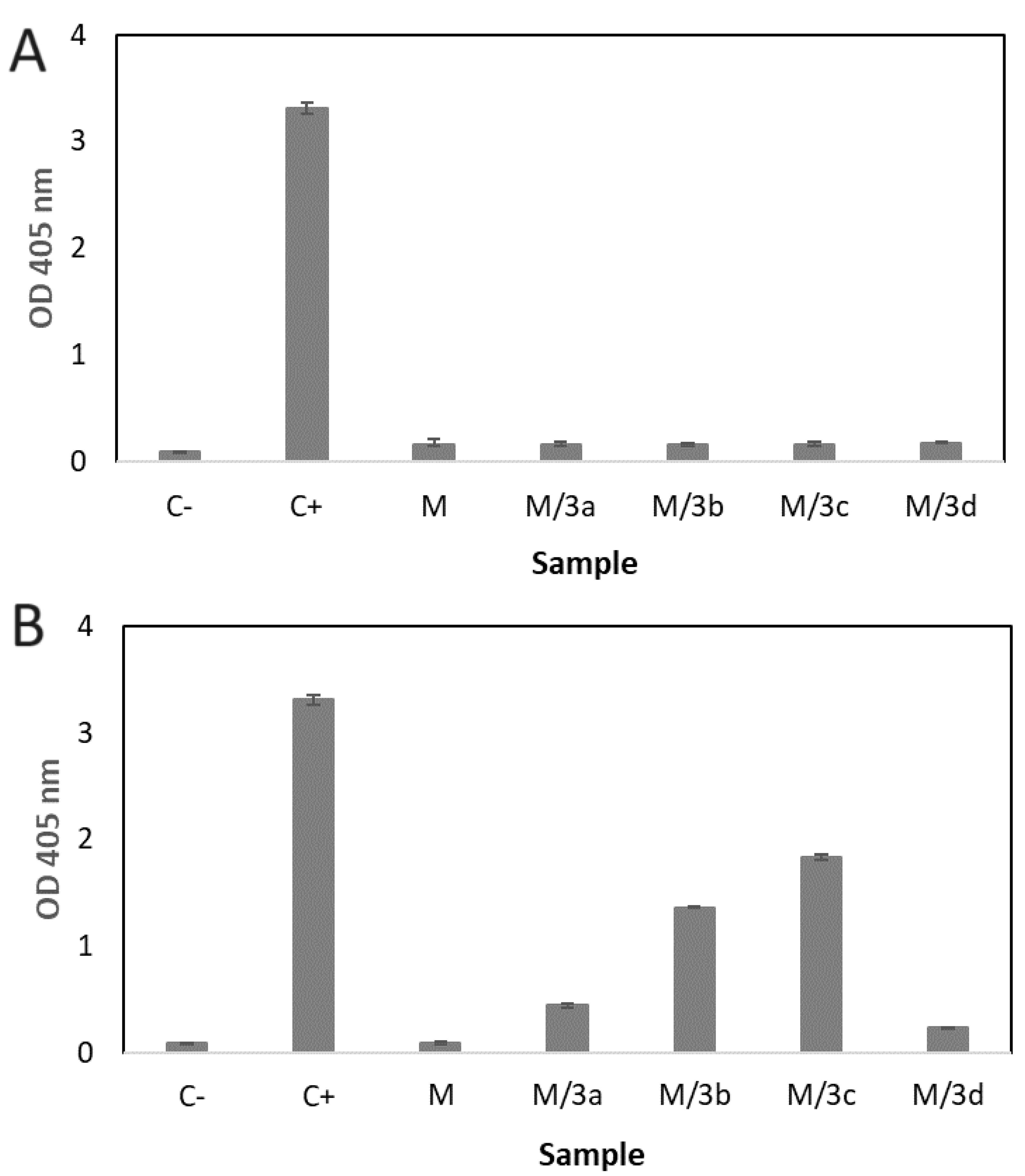

3.3. Hemolytic Effect

Hemolytic assay was conducted to evaluate the hemocompatibility of the developed formulations. Hemolysis is defined as rupturing the membrane of erythrocytes that causes the release of hemoglobin and other internal component into the surrounding fluid [

21]. Hemolytic effect is presented in

Figure 4. All kinds of NS, both, drug-loaded (NS/3a, NS/3b, NS/3c and NS/3d) and drug free (NS) did not show any hemolytic effect (

Figure 4A). Contrary, differences were observed in the effect of micelles on the erythrocytes (

Figure 4B). Drug-free micelles (M) showed effect similar to negative control. Insignificant hemolytic effect exhibited micelles loaded with 3a (M/3a) and 3d (M/3d). Significantly increased hemolysis was observed for M/3b and M/3c.

3.4. Hemolytic Effect

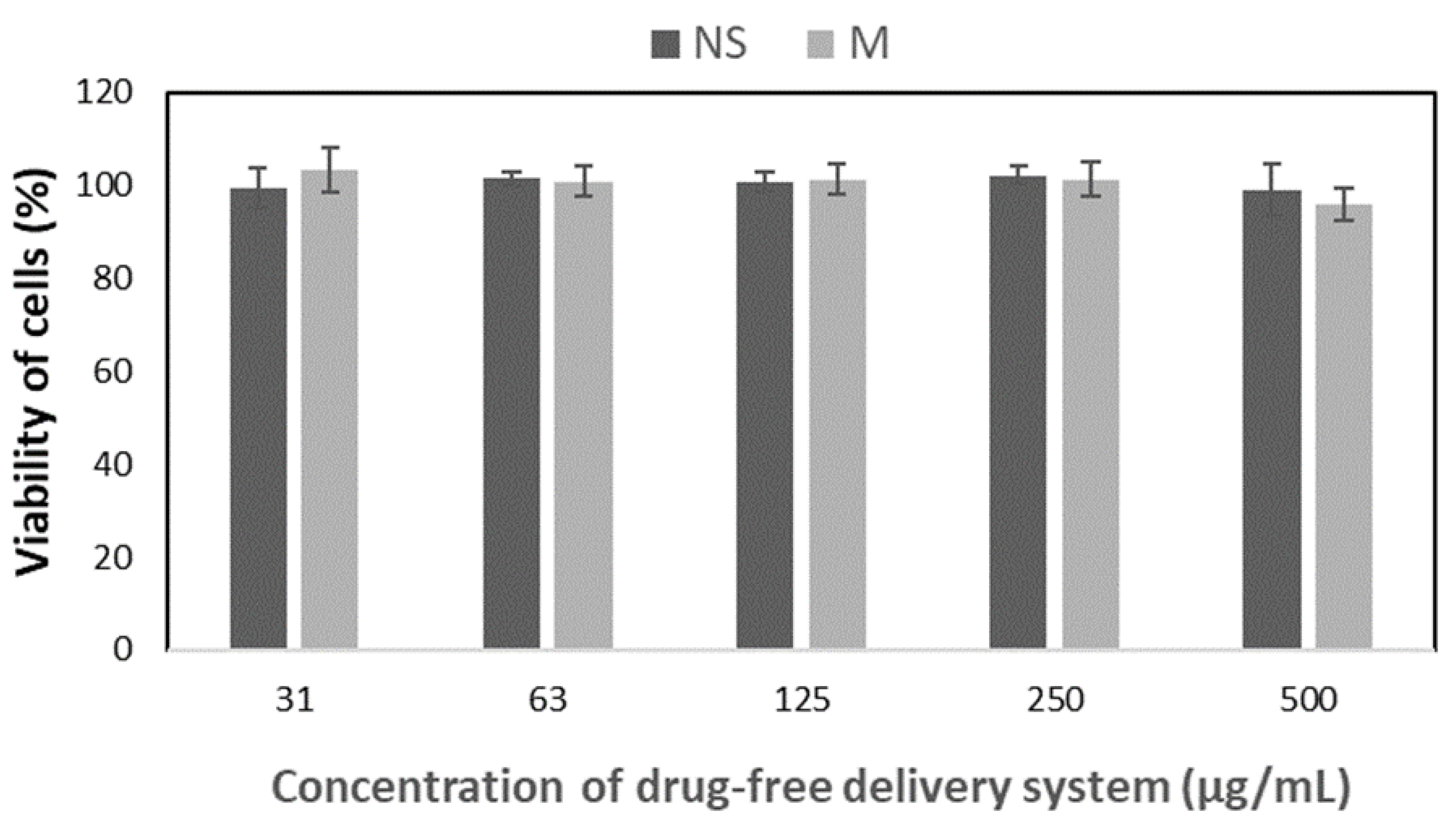

The

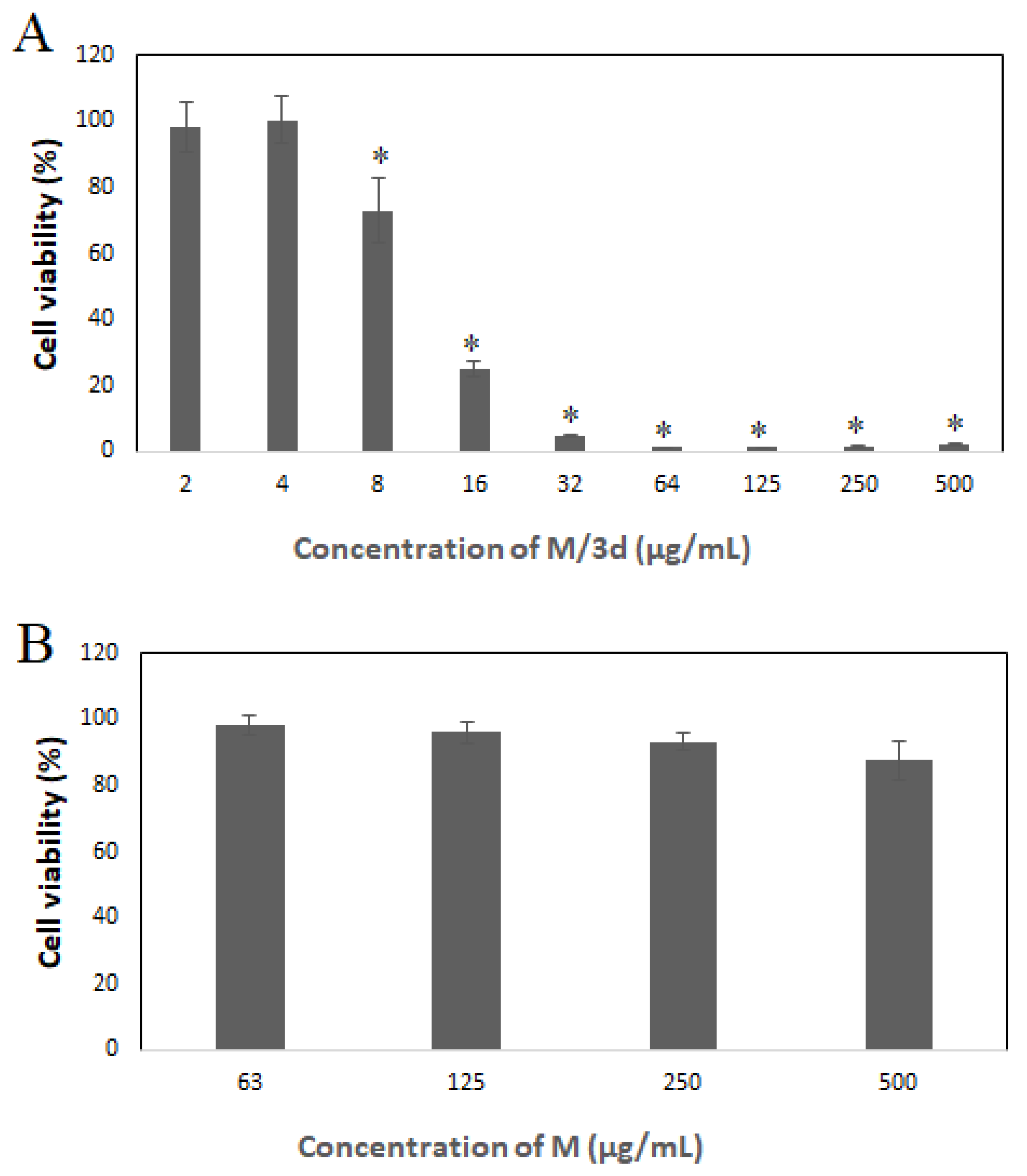

in vitro cytotocompatibility of the drug-free nanospheres and micelles has been analyzed according to the ISO 10993-5 standard with the use of L-929 fibroblasts and CCK-8 assay. The CCK-8 assay is a sensitive colorimetric technique used for the determination of the cell viability using WST-8 (2-(2-methoxy-4-nitrophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulfophenyl)-2H tetrazolium, monosodium salt) that is reduced by cellular dehydrogenases to an orange formazan product. The amount of the produced formazan is directly proportional to the number of living cells. As shown in

Figure 5, proliferation of in all tested drug-free formulations did not differ with the standard cell culture, which confirms cytocompatibility of all the studied drug-free nanoparticles.

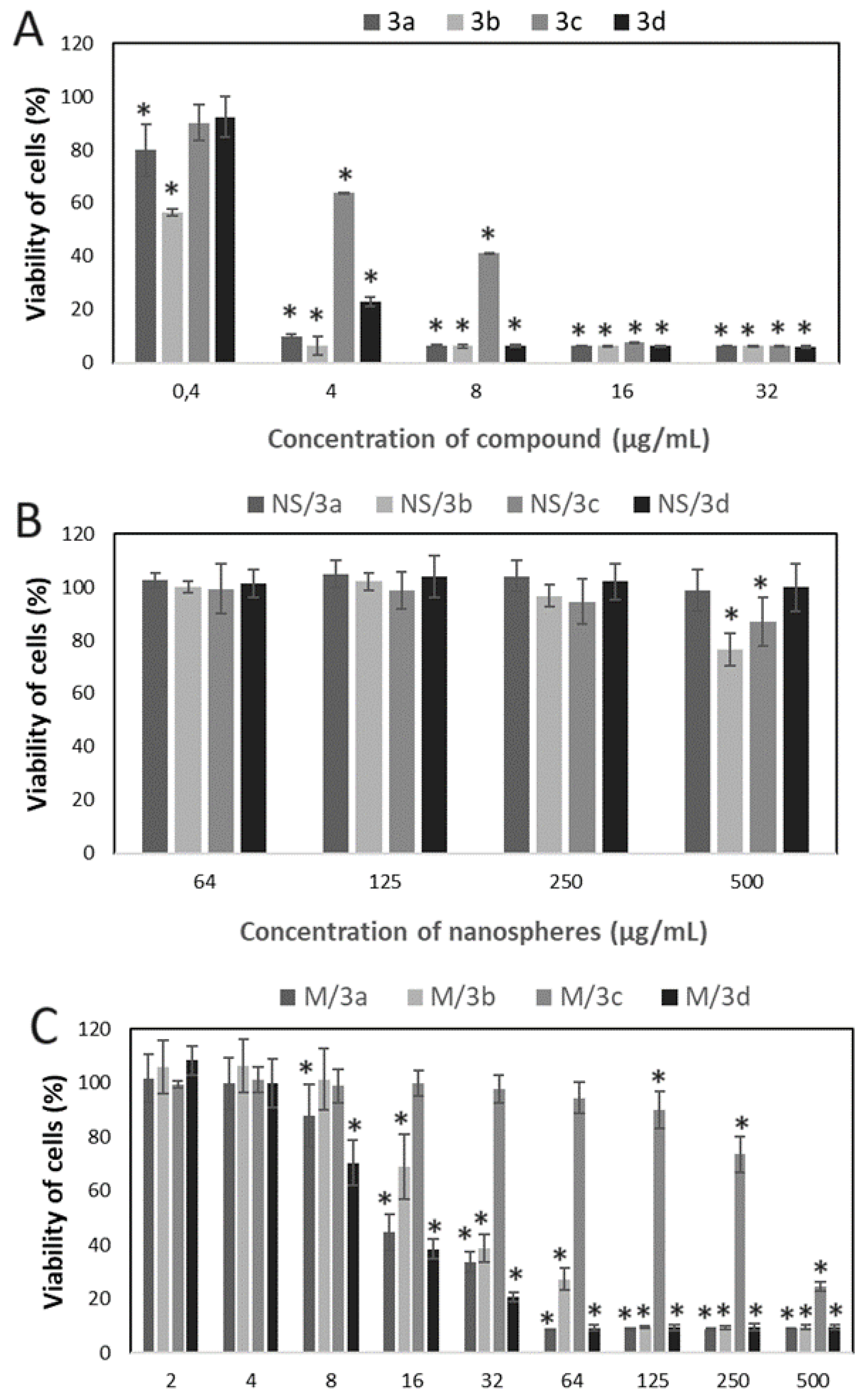

In the next step, cytotoxicity study was conducted to evaluate the effect of native drug, drug-encapsulated in NS and drug encapsulated in M against cervical cancer cells (HeLa) (

Figure 6). According to the expectations the strongest effect was observed for free drug, which caused the decrease of viability of cells even at the lowest studied concentration (0.4 µg/mL) in the case of 3a and 3b (

Figure 6A). At the concentration equal and above 4 µg/mL, all the compounds showed cytotoxic effect, however it was less significant for 3c at 8 and 16 µg/mL.

The drugs encapsulated into NS revealed significantly slighter cytotoxic effect on HeLa cells (

Figure 6B). Decrease of cells viability was observed only for NS/3b and NS/3c at 500 µg/mL.

Significantly stronger cytotoxic effect was observed for drugs-loaded micelles (

Figure 6C). Inhibition of cells growth in the presence of M/3a and M/3d was observed at the concentration range from 8 – 500 µg/mL, M/3b from 16 to 500 µg/mL. The lowest inhibitory effect exhibited M/3c (125 – 500 µg/mL).

Additional cytotoxicity study was conducted for selected type of nanoparticles – M/3d. The decrease of viability of HeLa cells cultured in the presence of M/3d at the concentration range of equal or above 8 µg/mL was confirmed by SRB assay (

Figure 7A). The drug-free micelles did not affect viability of cells as shown in

Figure 7B.

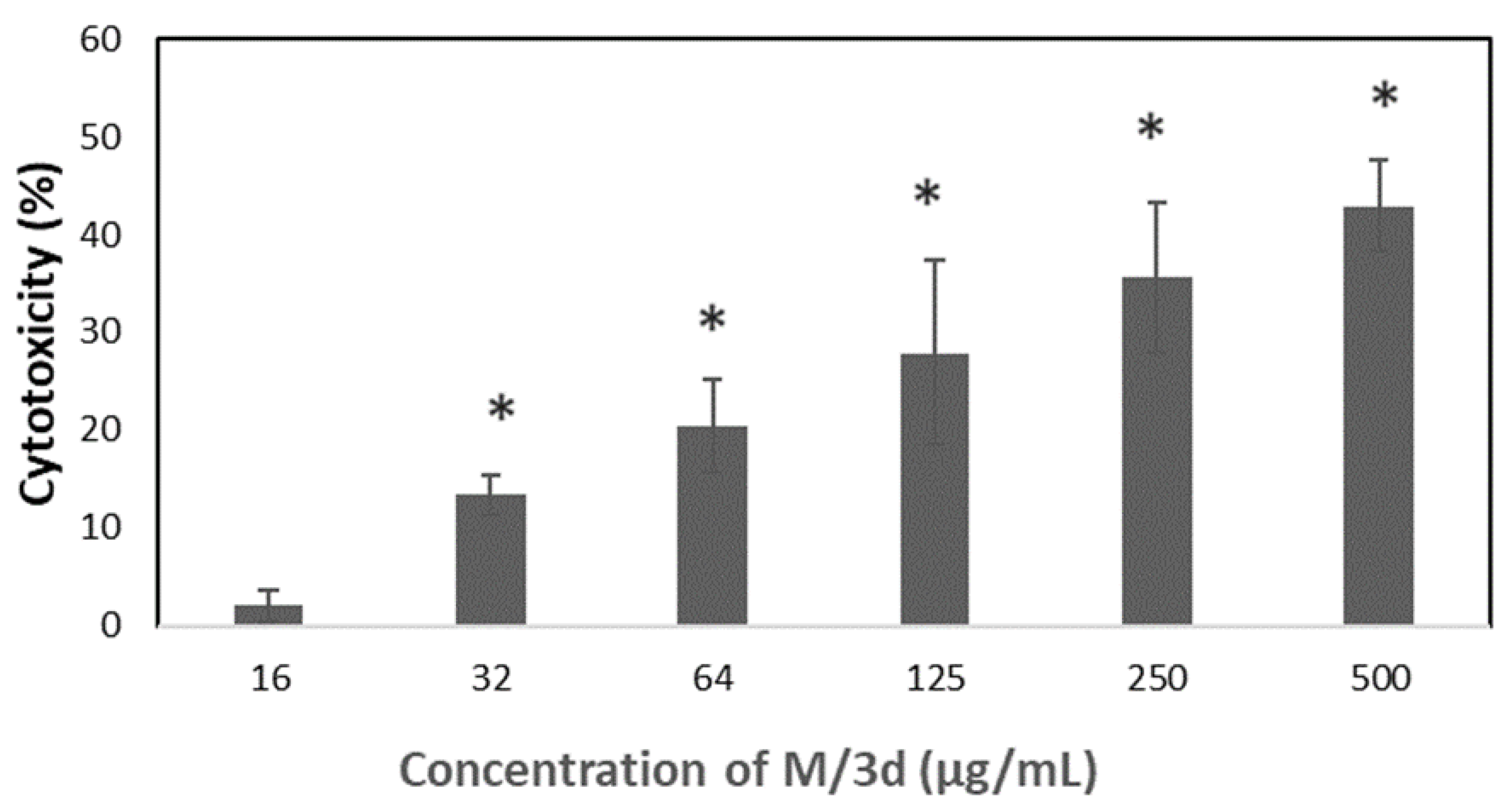

The M/3d of concentration equal or above 32 µg/mL caused also significant increase of LDH release as presented in

Figure 8.

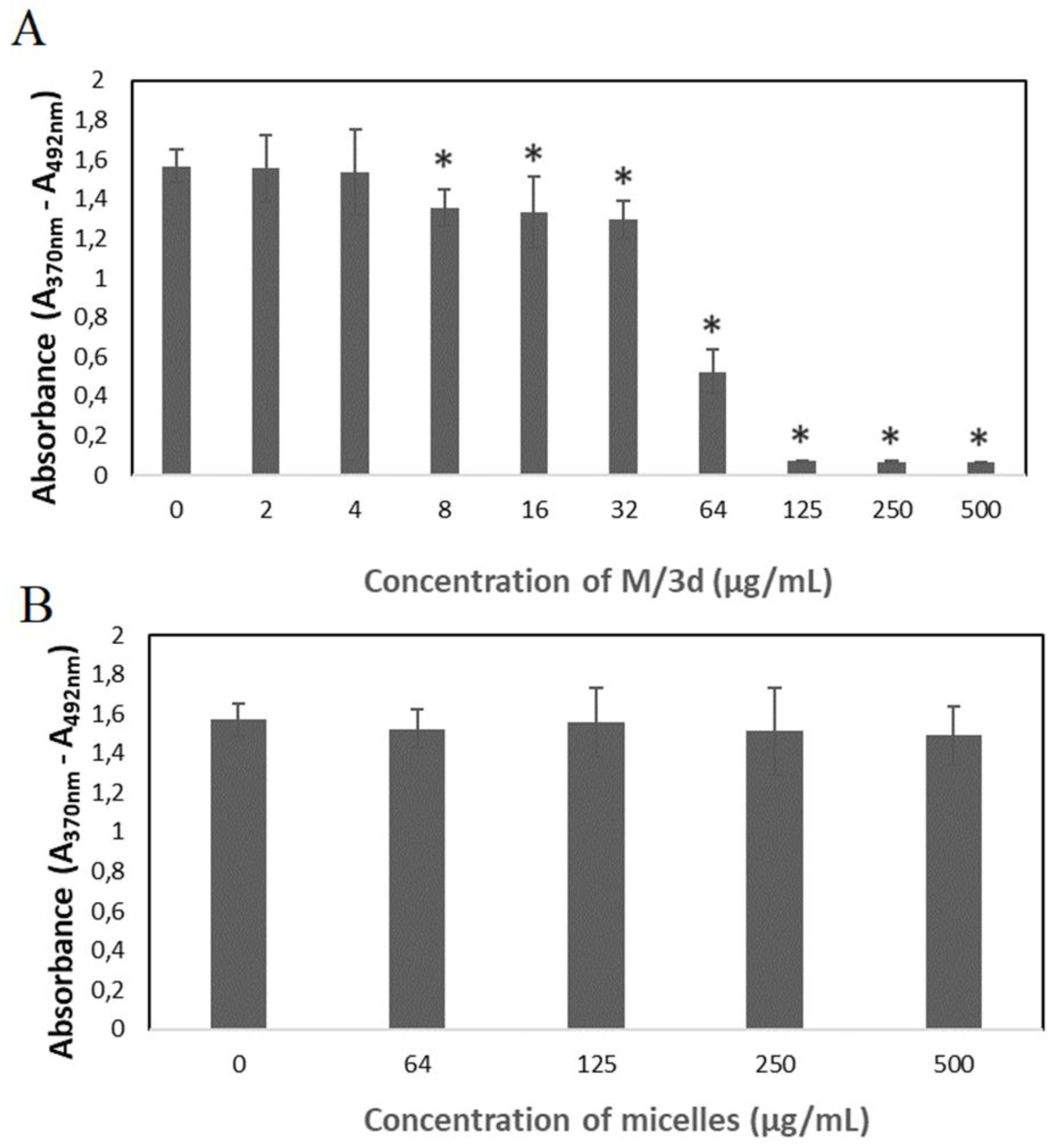

Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assay was conducted to analyze the synthesis of DNA in cells treated with M/3d. The results show that the M/3d at the concentration of 8 µg/mL and higher caused a significant reduction of cell divisions (

Figure 9A). The cell divisions were not affected in the presence of blank micelles (

Figure 9B), confirming their biocompatibility and the fact that the cytotoxic effect was caused by the 3d compound released from the micelles.

4. Discussion

Cancer is the second leading cause of death and this burden continues to increase. Conventional cancer treatments often suffer from limitations such as systemic toxicity, poor pharmacokinetics and drug resistance. Therefore, there is an urgent need for novel drugs with increased efficacy for the treatment of different cancers [

22,

23]. In our previous study, new 5-methyl-12

H-quino[3,4-

b][

1,

4]benzothiazinium chlorides have been synthesized and characterized (

Scheme 1). The activity of the obtained compounds was investigated

in vitro using cultured human colon carcinoma (Hct11) and Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cell lines [

2] and the results demonstrated a structure activity relationship. The greatest activity was shown by the compound with substituents in 9- and 10-position of the quinobenzothiazine ring and by the compound which does not feature any additional substituents. Despite therapeutic potential, the new compounds display some drawbacks that can reduce their effectiveness, e.g. limited solubility in water. Therefore, along with development of novel compounds with anticancer potential, it is also necessary to develop an appropriate DDS. To overcome these limitations, various DDS have been developed and one of a leading direction is nanotechnology. Nanoparticles are carriers with a submicron size that can be created to contain and deliver therapeutic substances to specific locations in the body, including tumors. Compared to the traditional chemotherapy, nano-delivery has many benefits, such as excellent drug solubility, prolonged drug release, and enhanced cellular uptake, leading to increased efficacy and reduced toxicity [

23].

Two kinds of nanoparticles have been selected to evaluate their potential in delivery of phenothiazine derivatives to cancer cells – nanospheres and micelles. The obtained nanoparticles have been characterized for their morphology and drug encapsulation properties. It has been determined that the type of active agent (phenothiazine derivative) did not affect the nanoparticles morphology, because all kinds of NS possess the same regular spherical shape with smooth surface and the average diameter of ≈ 870 nm (

Figure 1). Similarly, no differences in size and morphology have been observed for phenothiazine derivatives-loaded micelles (

Figure 2). Significant differences have been observed in drug loading properties between NS and M, because the content of all kinds of active compounds was much higher in the case of micelles (Table 2). Apparently, the matrix-type of DDS, typical for NS was not efficient for encapsulation of phenothiazine derivatives. Also, despite both kinds of drug-free nanoparticles showed cytocompatibility evaluated according to the ISO 10994-5 standard (

Figure 5), the drug-loaded NS did not show any cytotoxic effect against HeLa cancer cells at the concentration below 500 µg/mL. Moreover, even at the concentration of 500 µg/mL, only NS/3b and NS/3c showed some cytotoxicity against HeLa cells. The reason of such insignificant cytotoxic effect of drug-loaded NS may be their low drug content (Table 2) and negligible drug release. Contrary, the drug-loaded micelles showed cytotoxic effect against cancer cells at much lower concentration (

Figure 6C), because inhibition of cells’ growth in the presence of M/3a and M/3d was observed already at the concentration of 8 µg/mL, M/3b from 16 µg/mL and M/3c from 125 µg/mL. This effect may have been facilitated by high drug content of drug in micelles (≈20 %) (Table 2) and their faster release, which reached even 50 % in the case of M/3d.

In the next step, the hemolytic effect was evaluated for NS and M, which influences also their pharmaceutical potential. Determination of hemolytic properties

in vitro is a common and important method for preliminary evaluation of cytotoxicity of various materials, chemicals, drugs, or any blood-contacting medical devices [

20]. As presented in Figure4, all kinds of NS, both, drug-loaded and drug free did not show any hemolytic effect (

Figure 4A). Contrary, differences were observed in the effect of micelles on the erythrocytes (

Figure 4B). Drug-free micelles (M) showed effect similar to negative control (C-). The M/3a and M/3d caused very insignificant hemolytic effect. Significantly increased hemolysis was observed for M/3b and M/3c. Apparently, the hemolytic has been caused by released active agent (3a-3d). In fact, the hemolysis of human erythrocytes of some phenothiazine drugs and phenothiazine derivatives has been reported [24-26].

Based on the preliminary study, the 3d-loaded micelles (M/3d) have been selected for the more detailed analysis of the cytotoxicity against cancer cells. In fact, M/3d showed the highest drug loading content, the most rapid release and the lowest hemolytic activity, which make them the most promising formulation. The SRB assay confirmed decrease of cell viability above 8 µg/mL of M/3d (

Figure 7A). The cytotoxicity of M/3d was analyzed also by measuring activity of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). The LDH is a stable enzyme, present in all cell types that is rapidly released into the cell medium upon damage of the plasma membrane, making it useful marker in cytotoxicity study. The M/3d above 32 µg/mL caused significantly increased LDH release (

Figure 8). The effect of M/3d on synthesis of DNA was analyzed by means of BrdU incorporation assay. It has been observed that M/3d at a concentration of 8 µg/mL and higher caused a significant reduction of cell divisions (

Figure 9A). The effect of drug-free micelles did not affect the HeLa cell viability and proliferation (

Figure 7B and 9B), confirming their biocompatibility and the fact that the cytotoxic effect was caused by the 3d compound released from the micelles.

5. Conclusions

PLA-based nanospheres and micelles have been evaluated as delivery system of four types of 5-methyl-12

H-quino[3,4-

b][

1,

4]benzothiazinium chlorides with anticancer potential. The analyzed compounds (3a-d) differed in the type of substituents (CH

3, NH

2, OH) (

Scheme 1). The micelles appeared much more efficient for loading of active compounds and their release, which caused significantly higher cytotoxic effect against cancer cells than observed for nanospheres. Thus, despite cytocompatibility of both types of nanoparticles, only micelles confirmed their feasibility as carriers of phenothiazine derivatives. The micelles containing 3d – the compound with OH group as substituent in the 10-position of the quinobenzothiazine ring showed the highest drug loading content, the most efficient drug release, the lowest hemolytic activity and the most significant cytotoxic effect against cancer cells. Therefore, the M/3d has been selected as the most promising formulation for anticancer application. The conducted study enabled to develop delivery system for the new anticancer compound and showed that the choice of drug carrier has a crucial effect on its cytotoxic potential against cancer cells.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Z. and K.J; methodology, A.Z, K.J, M.M-K; investigation, A.Z, K.J, M.M-K, M.P, A.F; writing—original draft preparation, K.J; writing—review and editing, A.Z, K.J, J.K, M.M-K; supervision, J.K; funding acquisition, J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by grant of Medical University of Silesia in Katowice No. PCN-1-061/K/2/F.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Morak-Młodawska, B.; Jeleń, M.; Pluta, K. Phenothiazines Modified with the Pyridine Ring as Promising Anticancer Agents. Life 2021, 11, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zięba, A.; Sochanik, A.; Szurko, A.; Rams, M.; Mrozek, A.; Cmoch, P. Synthesis and in vitro antiproliferative activity of 5-alkyl-12(H)-quino[3,4-b] [1,4]benzothiazinium salts. Eur J Med Chem 2010, 45, 4733–4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, C.; Baião, A.; Ding, T.; Cui, W.; Sarmento, B. Recent advances in long-acting drug delivery systems for anticancer drug. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2023, 194, 114724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, L.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shao, A. Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery in Cancer Therapy and Its Role in Overcoming Drug Resistance. Frontiers in molecular biosciences 2020, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredenberg, S.; Wahlgren, M.; Reslow, M.; Axelsson, A. The mechanisms of drug release in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-based drug delivery systems—A review. Int J Pharmaceut 2011, 415, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A.; Almotairy, A.R.Z.; Henidi, H.; Alshehri, O.Y.; Aldughaim, M.S. Nanoparticles as Drug Delivery Systems: A Review of the Implication of Nanoparticles’ Physicochemical Properties on Responses in Biological Systems. Polymers 2023, 15, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumustas, M.; Sengel-Turk, C.T.; Gumustas, A.; Ozkan, S.A.; Uslu, B. Effect of Polymer-Based Nanoparticles on the Assay of Antimicrobial Drug Delivery Systems.

- Song, X.; Zhao, Y.; Hou, S.; Xu, F.; Zhao, R.; He, J.; Cai, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q. Dual agents loaded PLGA nanoparticles: Systematic study of particle size and drug entrapment efficiency. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2008, 69, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Cheng, D.; Niu, B.; Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Wang, A. Properties of Poly (Lactic-co-Glycolic Acid) and Progress of Poly (Lactic-co-Glycolic Acid)-Based Biodegradable Materials in Biomedical Research. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, S.; Han, Y.; Guan, J.; Chung, S.; Wang, C.; Li, D. Poly(Ethylene Glycol)-Polylactide Micelles for Cancer Therapy. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, S.; Atchudan, R.; Lee, W. A Review of Polymeric Micelles and Their Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuru, M.M.; Dalgakiran, E.A.; Kacar, G. Investigation of morphology, micelle properties, drug encapsulation and release behavior of self-assembled PEG-PLA-PEG block copolymers: A coarse-grained molecular simulations study. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2021, 629, 127445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Gao, J.; Kwon, G.S. PEG-b-PLA micelles and PLGA-b-PEG-b-PLGA sol-gels for drug delivery. J Control Release 2016, 240, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Estevez, A.M.; Gref, R.; Alonso, M.J. A journey through the history of PEGylated drug delivery nanocarriers. Drug Delivery and Translational Research 2024, 14, 2026–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hari, S.K.; Gauba, A.; Shrivastava, N.; Tripathi, R.M.; Jain, S.K.; Pandey, A.K. Polymeric micelles and cancer therapy: an ingenious multimodal tumor-targeted drug delivery system. Drug Delivery and Translational Research 2023, 13, 135–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelonek, K.; Zajdel, A.; Wilczok, A.; Kaczmarczyk, B.; Musiał-Kulik, M.; Hercog, A.; Foryś, A.; Pastusiak, M.; Kasperczyk, J. Comparison of PLA-Based Micelles and Microspheres as Carriers of Epothilone B and Rapamycin. The Effect of Delivery System and Polymer Composition on Drug Release and Cytotoxicity against MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cells. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurczyk, M.; Musiał-Kulik, M.; Foryś, A.; Godzierz, M.; Kaczmarczyk, B.; Kasperczyk, J.; Wrześniok, D.; Beberok, A.; Jelonek, K. Comparison of PLLA-PEG and PDLLA-PEG micelles for co-encapsulation of docetaxel and resveratrol. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials 2024, 112, e35318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelonek, K.; Karpeta, P.; Jaworska, J.; Pastusiak, M.; Wlodarczyk, J.; Kasperczyk, J.; Dobrzynski, P. Comparison of extraction methods of sirolimus from polymeric coatings of bioresorbable vascular scaffolds. Materials Letters 2018, 214, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentrivedi, A.; Kitabatake, N.; Doi, E. Toxicity of Dimethyl-Sulfoxide as a Solvent in Bioassay System with Hela-Cells Evaluated Colorimetrically with 3-(4,5-Dimethyl Thiazol-2-Yl)-2,5-Diphenyl-Tetrazolium Bromide. Agr Biol Chem Tokyo 1990, 54, 2961–2966. [Google Scholar]

- Sæbø, I.P.; Bjørås, M.; Franzyk, H.; Helgesen, E.; Booth, J.A. Optimization of the Hemolysis Assay for the Assessment of Cytotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.G.; Idrovo, J.P.; Nicastro, J.; McMullen, H.F.; Molmenti, E.P.; Coppa, G. A retrospective analysis of the incidence of hemolysis in type and screen specimens from trauma patients. The International journal of angiology : official publication of the International College of Angiology, Inc 2009, 18, 182–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.M.-L.; Chan, B.D.; Wong, W.-Y.; Leung, T.-W.; Qu, Z.; Huang, J.; Zhu, L.; Lee, C.-S.; Chen, S.; Tai, W.C.-S. Synthesis and Evaluation of Novel Anticancer Compounds Derived from the Natural Product Brevilin A. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 14586–14596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzari-Tavakoli, A.; Babajani, A.; Tavakoli, M.M.; Safaeinejad, F.; Jafari, A. Integrating natural compounds and nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems: A novel strategy for enhanced efficacy and selectivity in cancer therapy. Cancer Medicine 2024, 13, e7010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvanova, B.; Tacheva, B.; Ivanov, I. Prehemolytic impact of phenothiazine drugs on the attachment of spectrin network in red blood cells. Folia Med (Plovdiv) 2023, 65, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Martinez, J.; Aviles, T.A.; Laboy-Torres, J.A. The hemolytic effect of some phenothiazine derivatives in vitro and in vivo. Archives internationales de pharmacodynamie et de therapie 1972, 196, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Aki, H.; Yamamoto, M. Biothermodynamic characterization of erythrocyte hemolysis induced by phenothiazine derivatives and anti-inflammatory drugs. Biochemical Pharmacology 1990, 39, 396–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).