Submitted:

04 October 2024

Posted:

07 October 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

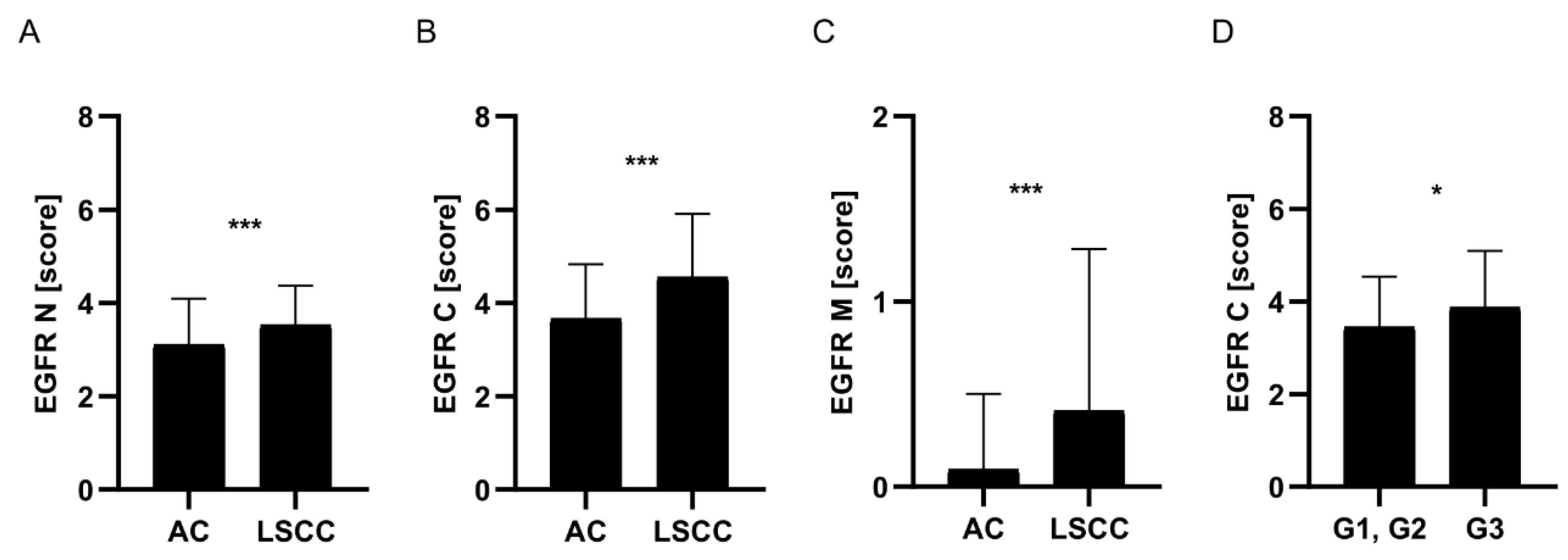

EGFR Expression Was Significantly Higher in LSCC Comparing to AC Tumours

There Were No Relationships between EGFR mRNA Expression and Clinical-Pathological Data of the Patients

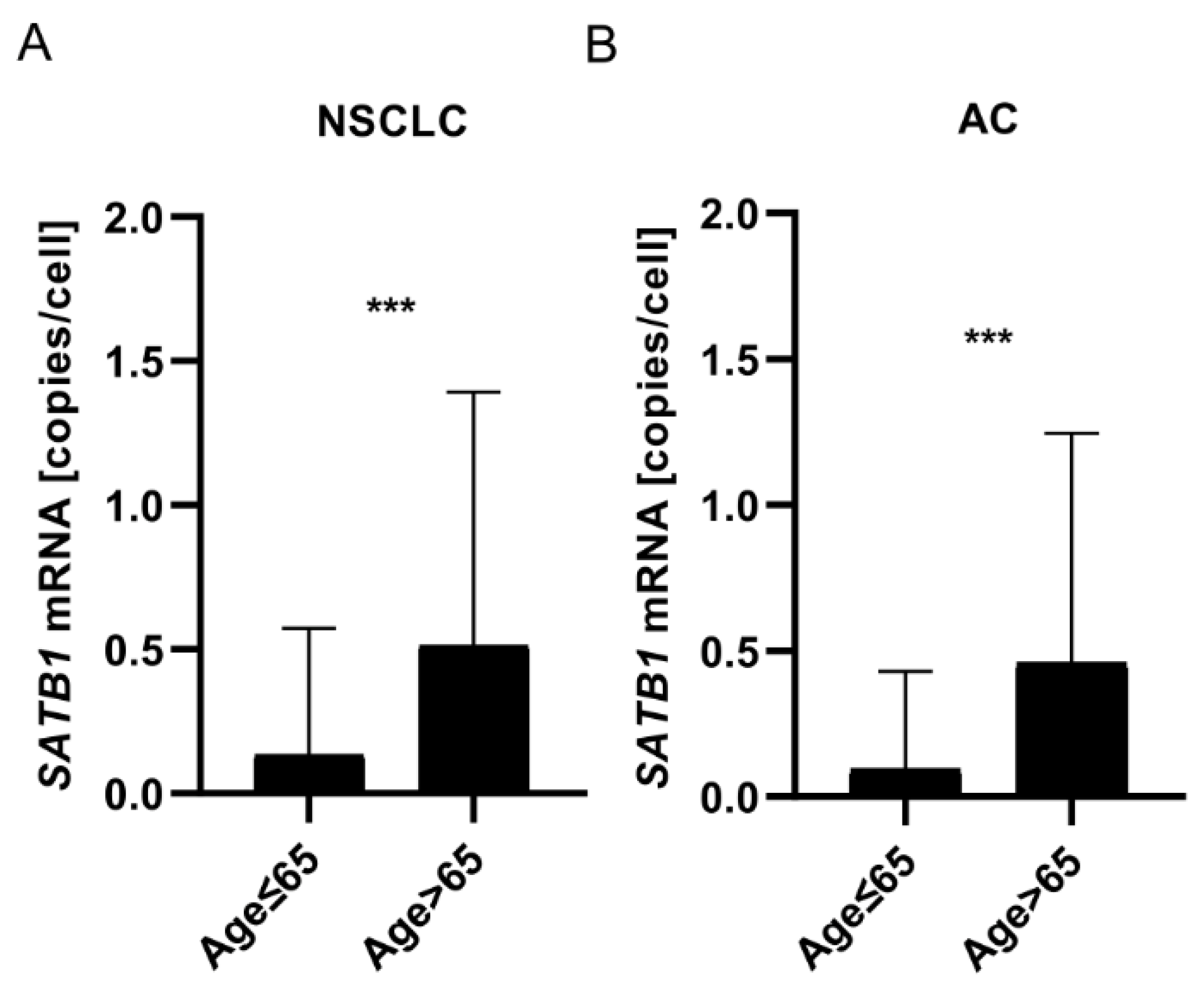

Expression of SATB1 mRNA Increased with Patients’ Age

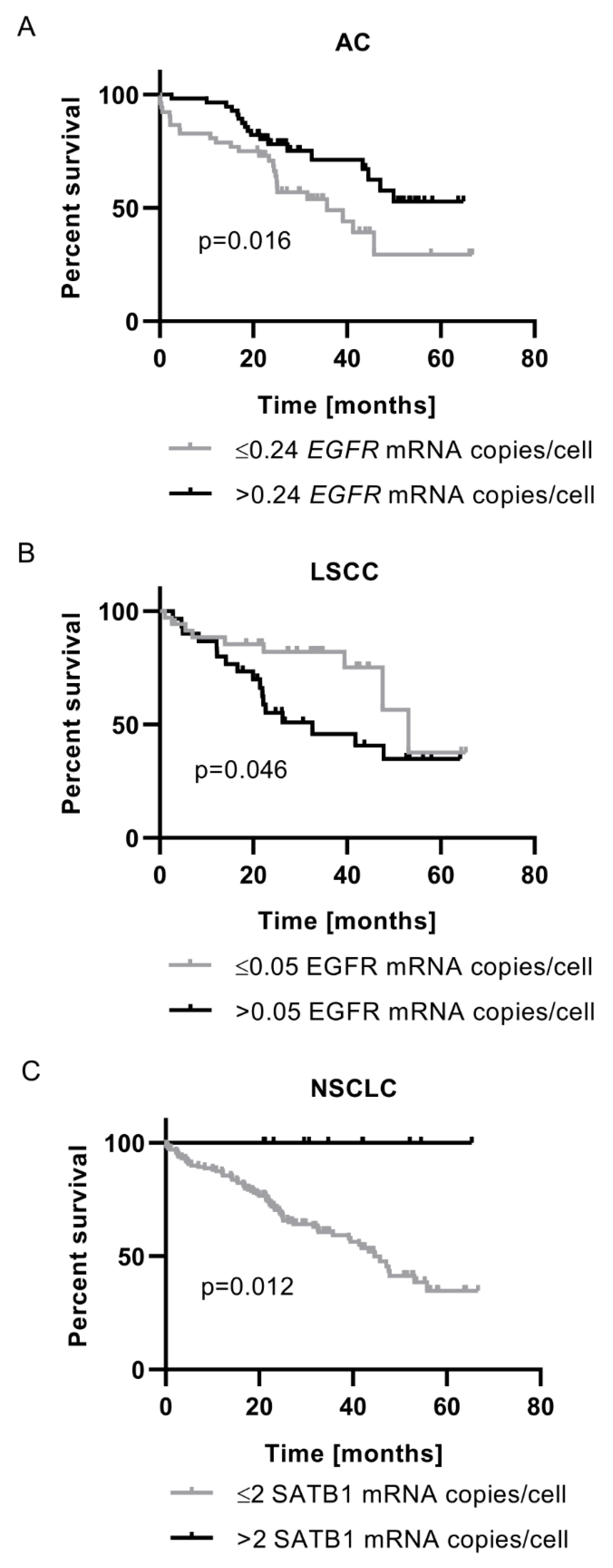

The Prognostic Significance of EGFR mRNA Expression Depended on Tumour Histology

SATB1 mRNA Expression Was Associated with Better Prognosis for NSCLC Patients

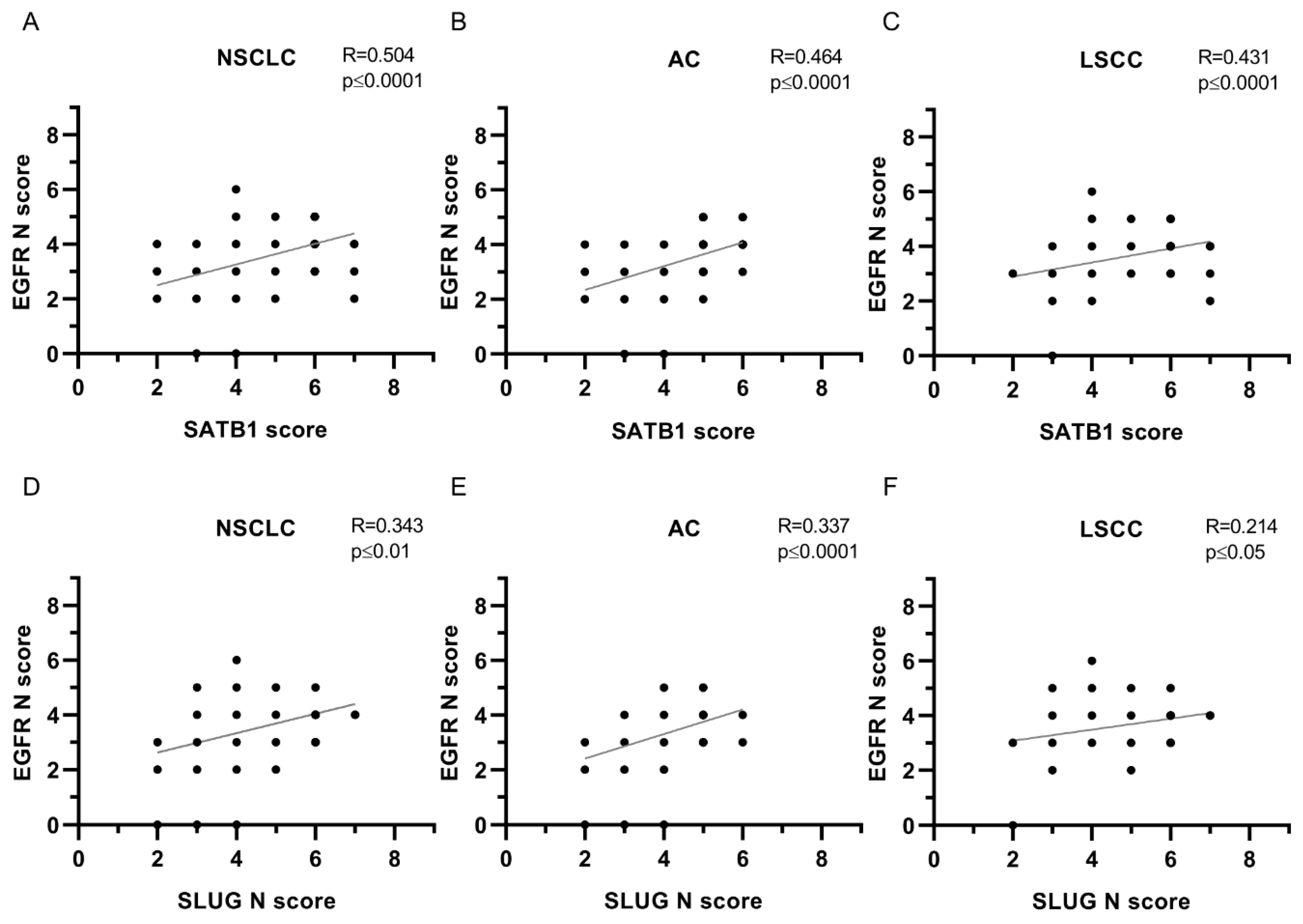

In LSCC, Membranous EGFR Expression Was Not Associated with the Level of Any of the Analysed Proteins

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Patient Cohort

Tissue Microarrays (TMAs)

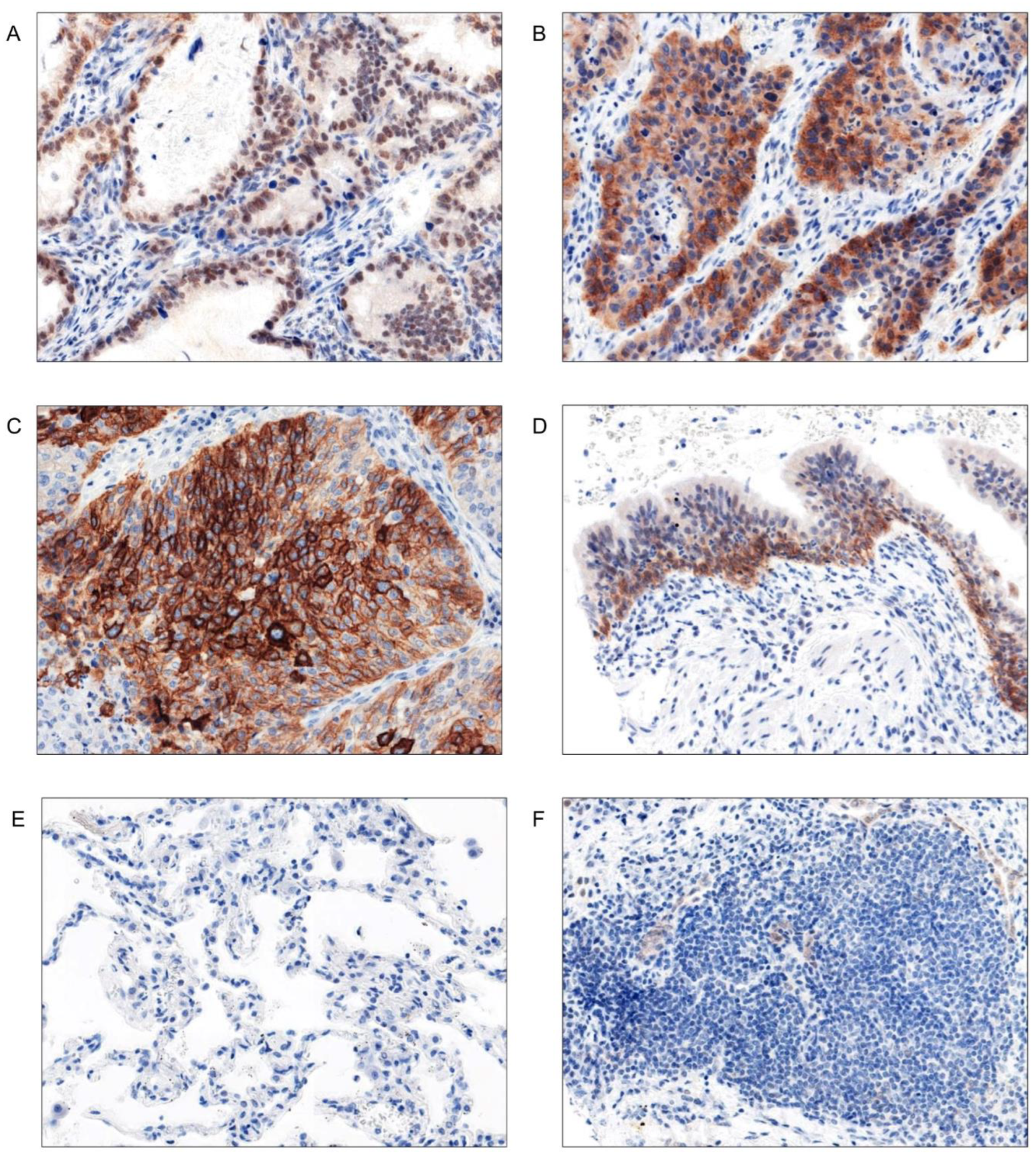

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Evaluation of the IHC Stainings

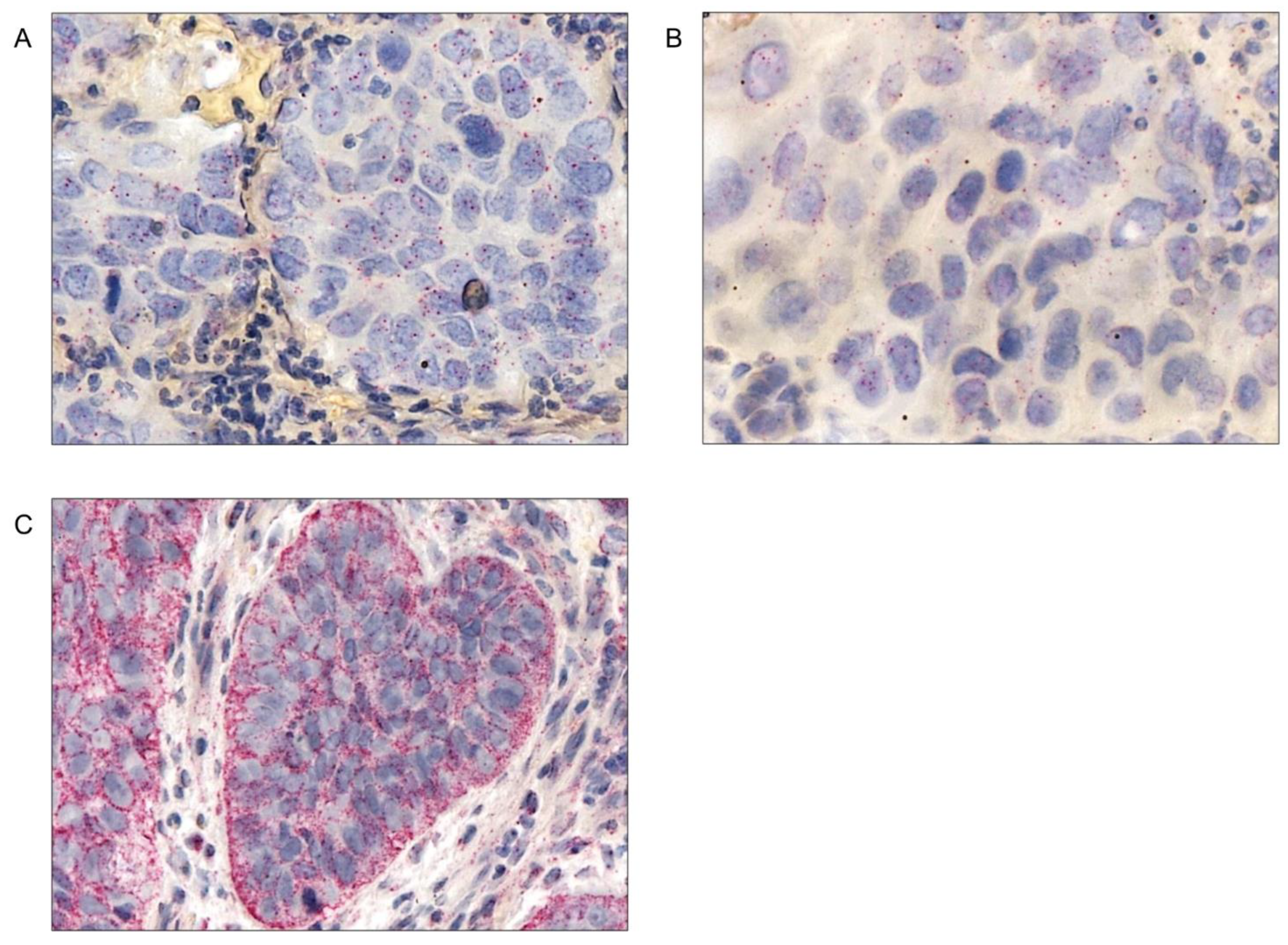

Chromogenic In Situ Hybridization (CISH)

Evaluation of the CISH Slides

Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality.

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Laversanne, M.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Pineros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Cancer Today (Version 1.1). Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/today.

- Roser, M.; Ritchie, H. Cancer. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/cancer.

- Ritchie, H.; Mathieu, E. How Many People Die and How Many Are Born Each Year? Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/births-and-deaths.

- Travis, W.D.; Brambilla, E.; Burke, A.P.; Marx, A.; Nicholson, A.G. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart; Lyon, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Travis, W.D.; Brambilla, E.; Nicholson, A.G.; Yatabe, Y.; Austin, J.H.M.; Beasley, M.B.; Chirieac, L.R.; Dacic, S.; Duhig, E.; Flieder, D.B.; et al. The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Genetic, Clinical and Radiologic Advances Since the 2004 Classification. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2015, 10, 1243–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Vaccarella, S.; Morgan, E.; Li, M.; Etxeberria, J.; Chokunonga, E.; Manraj, S.S.; Kamate, B.; Omonisi, A.; Bray, F. Global Variations in Lung Cancer Incidence by Histological Subtype in 2020: A Population-Based Study. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, 1206–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodak, O.; Peris-Díaz, M.D.; Olbromski, M.; Podhorska-Okołów, M.; Dzięgiel, P. Current Landscape of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Epidemiology, Histological Classification, Targeted Therapies, and Immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13, 4705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, B.W.; Wild, C.P. World Cancer Report 2014; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Selinger, C.I.; Cooper, W.a.; Al-Sohaily, S.; Mladenova, D.N.; Pangon, L.; Kennedy, C.W.; McCaughan, B.C.; Stirzaker, C.; Kohonen-Corish, M.R.J. Loss of Special AT-Rich Binding Protein 1 Expression Is a Marker of Poor Survival in Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2011, 6, 1179–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziej, J.; Marciniak, M. Rak Płuca; I.; Termedia Wydawnictwa Medyczne: Poznań, 2010; ISBN 978-83-62183-31-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ostroverkhova, D.; Przytycka, T.M.; Panchenko, A.R. Cancer Driver Mutations: Predictions and Reality. Trends Mol. Med. 2023, 29, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallier, M.; Borgeaud, M.; Addeo, A.; Friedlaender, A. Oncogenic Driver Mutations in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Past, Present and Future. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 12, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassem, J.; Drosik, K.; Dziaduszko, R.; Kordek, R.; Kozielski, J.; Kowalski, D.; Krzakowski, M.; Nikliński, J.; Olszewski, W.; Orłowski, T.; et al. Systemowe Leczenie Niedrobnokomórkowego Raka Płuc i Złośliwego Międzybłoniaka Opłucnej: Uaktualnione Zalecenia Oparte Na Wynikach Wiarygodnych Badań Klinicznych. Nowotwory. J. Oncol. 2007, 57, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, F.R.; Scagliotti, G.V.; Mulshine, J.L.; Kwon, R.; Curran, W.J.; Wu, Y.-L.; Paz-Ares, L. Lung Cancer: Current Therapies and New Targeted Treatments. Lancet 2016, 389, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, R.; Meernik, C.; Jeon, J.; Cote, M.L. Lung Cancer Incidence Trends by Gender, Race and Histology in the United States, 1973-2010. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0121323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normanno, N.; De Luca, A.; Bianco, C.; Strizzi, L.; Mancino, M.; Maiello, M.R.; Carotenuto, A.; De Feo, G.; Caponigro, F.; Salomon, D.S. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Signaling in Cancer. Gene 2006, 366, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Goldstein, D.; Crowe, P.J.; Yang, J.-L. Next-Generation EGFR/HER Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors for the Treatment of Patients with Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Harboring EGFR Mutations: A Review of the Evidence. Onco. Targets. Ther. 2016, 9, 5461–5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Cunha Santos, G.; Shepherd, F.A.; Tsao, M.S. EGFR Mutations and Lung Cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2011, 6, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zappa, C.; Mousa, S.A. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Current Treatment and Future Advances. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2016, 5, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araki, T.; Kanda, S.; Horinouchi, H.; Ohe, Y. Current Treatment Strategies for EGFR-Mutated Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: From First Line to beyond Osimertinib Resistance. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 53, 547–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, D.A.E.; Ashton, S.E.; Ghiorghiu, S.; Eberlein, C.; Nebhan, C.A.; Spitzler, P.J.; Orme, J.P.; Finlay, M.R.V.; Ward, R.A.; Mellor, M.J.; et al. AZD9291, an Irreversible EGFR TKI, Overcomes T790M-Mediated Resistance to EGFR Inhibitors in Lung Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2014, 4, 1046–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxnard, G.R.; Hu, Y.; Mileham, K.F.; Husain, H.; Costa, D.B.; Tracy, P.; Feeney, N.; Sholl, L.M.; Dahlberg, S.E.; Redig, A.J.; et al. Assessment of Resistance Mechanisms and Clinical Implications in Patients With EGFR T790M–Positive Lung Cancer and Acquired Resistance to Osimertinib. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 1527–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.C.; Tan, D.S.W. Targeted Therapies for Lung Cancer Patients With Oncogenic Driver Molecular Alterations. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keedy, V.L.; Temin, S.; Somerfield, M.R.; Beasley, M.B.; Johnson, D.H.; McShane, L.M.; Milton, D.T.; Strawn, J.R.; Wakelee, H.A.; Giaccone, G. American Society of Clinical Oncology Provisional Clinical Opinion: Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Mutation Testing for Patients with Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Considering First-Line EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 2121–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Fu, S.; Shao, Q.; Zhou, Y.-B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Xue, C.; Lin, J.-G.; Huang, L.-X.; Zhang, L.; et al. High EGFR Copy Number Predicts Benefits from Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Treatment for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients with Wild-Type EGFR. J. Transl. Med. 2013, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Fang, W.; Mu, L.; Tang, Y.; Gao, L.; Ren, S.; Cao, D.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, A.; Liu, D.; et al. Overexpression of Wildtype EGFR Is Tumorigenic and Denotes a Therapeutic Target in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 3884–3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, B.; Meyer-Staeckling, S.; Schmidt, H.; Agelopoulos, K.; Buerger, H. Mechanisms of Egfr Gene Transcription Modulation: Relationship to Cancer Risk and Therapy Response. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 7252–7260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.-J.; Russo, J.; Kohwi, Y.; Kohwi-Shigematsu, T. SATB1 Reprogrammes Gene Expression to Promote Breast Tumour Growth and Metastasis. Nature 2008, 452, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohwi-Shigematsu, T.; Kohwi, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Richards, H.W.; Ayers, S.D.; Han, H.-J.; Cai, S. SATB1-Mediated Functional Packaging of Chromatin into Loops. Methods 2012, 58, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galande, S.; Purbey, P.K.; Notani, D.; Kumar, P.P. The Third Dimension of Gene Regulation: Organization of Dynamic Chromatin Loopscape by SATB1. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2007, 17, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohwi-Shigematsu, T.; Poterlowicz, K.; Ordinario, E.; Han, H.-J.; Botchkarev, V.A.; Kohwi, Y. Genome Organizing Function of SATB1 in Tumor Progression. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2013, 23, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.O.; Zhou, H.; Wang, S.; Lang, X.P.; Wang, X. Effect of Silencing SATB1 on Proliferation, Invasion and Apoptosis of A549 Human Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 12, 3818–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, F.; Cheng, C.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, X.; Zeng, H.; Xing, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. SATB1 Overexpression Regulates the Development and Progression in Bladder Cancer through EMT. PLoS One 2015, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.-Q.; Chen, Z.-Q.; Cao, X.-X.; Xu, J.-W.J.-D.J.-W.J.-D.J.-W.; Xu, J.-W.J.-D.J.-W.J.-D.J.-W.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Wang, W.-J.; Chen, Q.; Tang, F.; Liu, X.-P.; et al. Involvement of NF-ΚB/MiR-448 Regulatory Feedback Loop in Chemotherapy-Induced Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition of Breast Cancer Cells. Cell Death Differ. 2011, 18, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.H.; Wang, F.; Shen, M.H.; Wang, X.; Zhou, X.J.; Zhou, X.J.; Yanfen-Wang; Shen, M.H.; Wang, X.; Zhou, X.J.; et al. SATB1 Expression Is Correlated with Betha-Catenin Associated Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2016, 17, 254–261. [CrossRef]

- Hanker, L.C.; Karn, T.; Mavrova-Risteska, L.; Ruckhäberle, E.; Gaetje, R.; Holtrich, U.; Kaufmann, M.; Rody, A.; Wiegratz, I. SATB1 Gene Expression and Breast Cancer Prognosis. The Breast 2011, 20, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tian, X.; Ji, H.; Guan, X.; Xu, W.; Dong, B.; Zhao, M.; Wei, M.; Ye, C.; Sun, Y.; et al. Expression of SATB1 Promotes the Growth and Metastasis of Colorectal Cancer. PLoS One 2014, 9, e100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, S.; Sharma, H.; Abbas, A.; MacLennan, G.T.; Fu, P.; Danielpour, D.; Gupta, S. Upregulation of SATB1 Is Associated with Prostate Cancer Aggressiveness and Disease Progression. PLoS One 2013, 8, e53527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nodin, B.; Hedner, C.; Uhlén, M.; Jirström, K. Expression of the Global Regulator SATB1 Is an Independent Factor of Poor Prognosis in High Grade Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. J. Ovarian Res. 2012, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatzel-Plucinska, N.; Piotrowska, A.; Grzegrzolka, J.; Olbromski, M.; Rzechonek, A.; Dziegiel, P.; Podhorska-Okolow, M. SATB1 Level Correlates with Ki-67 Expression and Is a Positive Prognostic Factor in Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2018, 38, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glatzel-Plucinska, N.; Piotrowska, A.; Rzechonek, A.; Podhorska-Okolow, M.; Dziegiel, P. SATB1 Protein Is Associated with the Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Process in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 45, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frömberg, A.; Rabe, M.; Oppermann, H.; Gaunitz, F.; Aigner, A. Analysis of Cellular and Molecular Antitumor Effects upon Inhibition of SATB1 in Glioblastoma Cells. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frömberg, A.; Rabe, M.; Aigner, A. Multiple Effects of the Special AT-Rich Binding Protein 1 (SATB1) in Colon Carcinoma. Int. J. cancer 2014, 135, 2537–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamio, T.; Shigematsu, K.; Sou, H.; Kawai, K.; Tsuchiyama, H. Immunohistochemical Expression of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptors in Human Adrenocortical Carcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 1990, 21, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, T.M.; Iida, M.; Li, C.; Wheeler, D.L. The Nuclear Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Signaling Network and Its Role in Cancer. Discov. Med. 2011, 12, 419–432. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.L.; Fang, C.L.; Tzeng, Y.T.; Hsu, H.L.; Lin, S.E.; Yu, M.C.; Bai, K.J.; Wang, L.S.; Liu, H.E. Prognostic Value of Localization of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor in Lung Adenocarcinoma. J. Biomed. Sci. 2018, 25, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marijić, B.; Braut, T.; Babarović, E.; Krstulja, M.; Maržić, D.; Avirović, M.; Kujundžić, M.; Hadžisejdić, I. Nuclear EGFR Expression Is Associated with Poor Survival in Laryngeal Carcinoma. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2021, 29, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traynor, A.M.; Weigel, T.L.; Oettel, K.R.; Yang, D.T.; Zhang, C.; Kim, K.; Salgia, R.; Iida, M.; Brand, T.M.; Hoang, T.; et al. Nuclear EGFR Protein Expression Predicts Poor Survival in Early Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Lung Cancer 2013, 81, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.C.; Lin, L.C.; Lin, Y.W.; Tian, Y.F.; Lin, C.Y.; Sheu, M.J.; Li, C.F.; Tai, M.H. Higher Nuclear EGFR Expression Is a Better Predictor of Survival in Rectal Cancer Patients Following Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy than Cytoplasmic EGFR Expression. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 17, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braut, T.; Krstulja, M.; Rukavina, K.M.; Jonjić, N.; Kujundžić, M.; Manestar, I.D.; Katunarić, M.; Manestar, D. Cytoplasmic EGFR Staining and Gene Amplification in Glottic Cancer: A Better Indicator of EGFR-Driven Signaling? Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2014, 22, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloura, V.; Vougiouklakis, T.; Zewde, M.; Deng, X.; Kiyotani, K.; Park, J.H.; Matsuo, Y.; Lingen, M.; Suzuki, T.; Dohmae, N.; et al. WHSC1L1-Mediated EGFR Mono-Methylation Enhances the Cytoplasmic and Nuclear Oncogenic Activity of EGFR in Head and Neck Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, S.; Ogata, S.; Tsuda, H.; Kawarabayashi, N.; Kimura, M.; Sugiura, Y.; Tamai, S.; Matsubara, O.; Hatsuse, K.; Mochizuki, H. The Correlation Between Cytoplasmic Overexpression of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor and Tumor Aggressiveness. Poor Prognosis in Patients With Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. J. Neuroendocr. Tumous Pancreat. Dis. Sci. 2004, 29, e1–e8. [Google Scholar]

- Tsao, A.S.; Ming Tang, X.; Sabloff, B.; Lianchun, X.; Shigematsu, H.; Roth, J.; Spitz, M.; Ki Hong, W.; Gazdar, A.; Wistuba, I. Clinicopathologic Characteristics of the EGFR Gene Mutation in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2006, 1, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italiano, A.; Burel Vandenbos, F.; Otto, J. Mouroux, D.; Fontaine, D.; Marcy, P.-Y.; Cardot, N.; Thyss, A.; Pedeutour, F. Comparison of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Gene and Protein in Primary Non-Small-Cell-Lung Cancer and Metastatic Sites: Implications for Treatment with EGFR-Inhibitors. Ann. Oncol. 2006, 17, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maramotti, S.; Paci, M.; Manzotti, G.; Rapicetta, C.; Gugnoni, M.; Galeone, C.; Cesario, A.; Lococo, F. Soluble Epidermal Growth Factor Receptors (SEGFRs) in Cancer: Biological Aspects and Clinical Relevance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maramotti, S.; Paci, M.; Miccichè, F.; Ciarrocchi, A.; Cavazza, A.; De Bortoli, M.; Vaghi, E.; Formisano, D.; Canovi, L.; Sgarbi, G.; et al. Soluble Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Isoforms in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Tissue and in Blood. Lung Cancer 2012, 76, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantus-Lewintre, E.; Sirera, R.; Cabrera, A.; Blasco, A.; Caballero, C.; Iranzo, V.; Rosell, R.; Camps, C. Analysis of the Prognostic Value of Soluble Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Plasma Concentration in Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Clin. Lung Cancer 2011, 12, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, P.; Zhao, J.; Wang, S.; Ming Kong, F. The Plasma Level of Soluble Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) and Overall Survival (OS) in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, e19091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lococo, F.; Paci, M.; Rapicetta, C.; Rossi, T.; Sancisi, V.; Braglia, L.; Cavuto, S.; Bisagni, A.; Bongarzone, I.; Noonan, D.M.; et al. Preliminary Evidence on the Diagnostic and Molecular Role of Circulating Soluble EGFR in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 19612–19630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meert, A.-P.; Martin, B.; Delmotte, P.; Berghmans, T.; Lafitte, J.-J.; Mascaux, C.; Paesmans, M.; Steels, E.; Verdebout, J.-M.; Sculier, J.-P. The Role of EGF-R Expression on Patient Survival in Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 2002, 20, 975–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, H.; Kawasaki, N.; Taguchi, M.; Kabasawa, K. Survival Impact of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Overexpression in Patients with Non-small Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-analysis. Thorax 2006, 61, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz Seyhan, E.; Altin, S.; Cetinkaya, E.; Sokucu, S.; Abali, H.; Buyukpinarbasili, N.; Fener, N. Prognostic Value of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Expression in Operable Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma. Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 2010, 5, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanini, G.; Vignati, S.; Bigini, D.; Mussi, A.; Lucchi, H.; Angeletti, A.; Pingitore, R.; Pepe, S.; Basolo, F.; Bevilacqua, G. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFr) Expression in Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinomas Correlates with Metastatic Involvement of Hilar and Mediastinal Lymph Nodes in the Squamous Subtype. Eur. J. Cancer 1995, 31A, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gately, K.; Forde, L.; Cuffe, S.; Cummins, R.; Kay, E.W.; Feuerhake, F.; O’Byrne, K.J. High Coexpression of Both EGFR and IGF1R Correlates with Poor Patient Prognosis in Resected Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer 2014, 15, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, F.R.; Varella-Garcia, M.; Bunn, P.A., Jr.; Di Maria, M.V.; Veve, R.; Bremmes, R.M.; Baron, A.E.; Zeng, C.; Franklin, W.A. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor in Non-Small-Cell Lung Carcinomas: Correlation between Gene Copy Number and Protein Expression and Impact on Prognosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 3798–3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Li, C.; Kang, B.; Gao, G.; Li, C.; Zhang, Z. GEPIA: A Web Server for Cancer and Normal Gene Expression Profiling and Interactive Analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W98–W102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Cho, M.; Wang, X. OncoDB: An Interactive Online Database for Analysis of Gene Expression and Viral Infection in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D1334–D1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, G.; Saeed, M.E.M.; Foersch, S.; Schneider, J.; Roth, W.; Efferth, T. Relationship between EGFR Expression and Subcellular Localization with Cancer Development and Clinical Outcome. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 1918–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, T.; Kollisnyk, B.; Aswathy, B.S.; Wan Kim, T.; Martin, J.; Plessis-Belair, J.; Ni, J.; Pearson, J.A.; Park, E.J.; Sher, R.B.; et al. The SATB1-MIR22-GBA Axis Mediates Glucocerebroside Accumulation Inducing a Cellular Senescence-like Phenotype in Dopaminergic Neurons, 2023.

- Riessland, M.; Kolisnyk, B.; Wan Kim, T.; Cheng, J.; Ni, J.; Pearson, J.A.; Park, E.J.; Dam, K.; Acehan, D.; Ramos-Espiritu, L.S.; et al. Loss of SATB1 Induces P21-Dependent Cellular Senescence in Post-Mitotic Dopaminergic Neurons. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 25, 514–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Poplawski, M.; Yen, K.; Cheng, H.; Bloss, E.; Zhu, X.; Patel, H.; Mobbs, C.V. Role of CBP and SATB-1 in Aging, Dietary Restriction, and Insulin-like Signaling. PLoS Biol. 2009, 7, e1000245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.I.; Pickup, M.E.; Rimmer, A.G.; Alam, M.; Mardaryev, A.N.; Poterlowicz, K.; Botchkareva, N.V.; Botchkarev, V.A. Interplay of MicroRNA-21 and SATB1 in Epidermal Keratinocytes during Skin Aging. J Invest Dermatol 2020, 139, 2538–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lena, A.M.; Mancini, M.; Rivetti di Val Cervo, P.; Saintigny, G.; Mahé, C.; Melino, G.; Candi, E.; Mahe, C.; Melino, G.; Candi, E. MicroRNA-191 Triggers Keratinocytes Senescence by SATB1 and CDK6 Downregulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2012, 423, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-C.; Chen, Y.-J.; Li, L.-Y.; Wei, Y.-L.; Hsu, S.-C.; Tsai, S.-L.; Chiu, P.-C.; Huang, W.-P.; Wang, Y.-N.; Chen, C.-H.; et al. Nuclear Translocation of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor by Akt-Dependent Phosphorylation Enhances Breast Cancer-Resistant Protein Expression in Gefitinib-Resistant Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 20558–20568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Xue, Z.; Yang, G.; Shi, B.; Yang, B.; Yan, Y.; Wang, X.; Han, D.; Huang, Y.; Dong, W. Akt-Signal Integration Is Involved in the Differentiation of Embryonal Carcinoma Cells. PLoS One 2013, 8, e64877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, T.; Tsubaki, M.; Matsuda, T.; Kimura, A.; Jinushi, M.; Obana, T.; Takegami, M.; Nishida, S. EGFR Inhibition Reverses Epithelial-mesenchymal Transition, and Decreases Tamoxifen Resistance via Snail and Twist Downregulation in Breast Cancer Cells. Oncol. Rep. 2022, 47, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusewitt, D.F.; Choi, C.; Newkirk, K.M.; Leroy, P.; Li, Y.; Chavez, M.G.; Hudson, L.G. Slug/Snai2 Is a Downstream Mediator of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Stimulated Reepithelialization. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronte, G.; Bravaccini, S.; Bronte, E.; Burgio, M.A.; Rolfo, C.; Delmonte, A.; Crinò, L. Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in the Context of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibition in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Biol. Rev. 2018, 93, 1735–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakobsen, K.R.; Demuth, C.; Sorensen, B.S.; Nielsen, A.L. The Role of Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition in Resistance to Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Transl. lung cancer Res. 2016, 5, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. Staging Manual in Thoracic Oncology, 2nd ed.; 2016; ISBN 978-0-9832958-6-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bankhead, P.; Loughrey, M.B.; Fernández, J.A.; Dombrowski, Y.; McArt, D.G.; Dunne, P.D.; McQuaid, S.; Gray, R.T.; Murray, L.J.; Coleman, H.G.; et al. QuPath: Open Source Software for Digital Pathology Image Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACD. Technical Notes. 2020; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

| EGFR N | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | NSCLC | AC | LSCC | |||

| Spearman’s R | P-value | Spearman’s R | P-value | Spearman’s R | P-value | |

| SATB1 | 0.504 | **** | 0.464 | **** | 0.431 | **** |

| Ki67 | 0.206 | *** | 0.106 | ns | 0.186 | ns |

| E-cadherin | 0.043 | ns | 0.004 | ns | 0.088 | ns |

| N-cadherin | 0.035 | ns | -0.013 | ns | 0.052 | ns |

| SNAIL | 0.129 | * | 0.205 | * | -0.086 | ns |

| SLUG N | 0.343 | ** | 0.337 | **** | 0.214 | * |

| SLUG C | 0.173 | **** | 0.227 | ** | 0.160 | ns |

| Twist1 | 0.249 | *** | 0.156 | ns | 0.241 | * |

| EGFR C | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | NSCLC | AC | LSCC | |||

| Spearman’s R | P-value | Spearman’s R | P-value | Spearman’s R | P-value | |

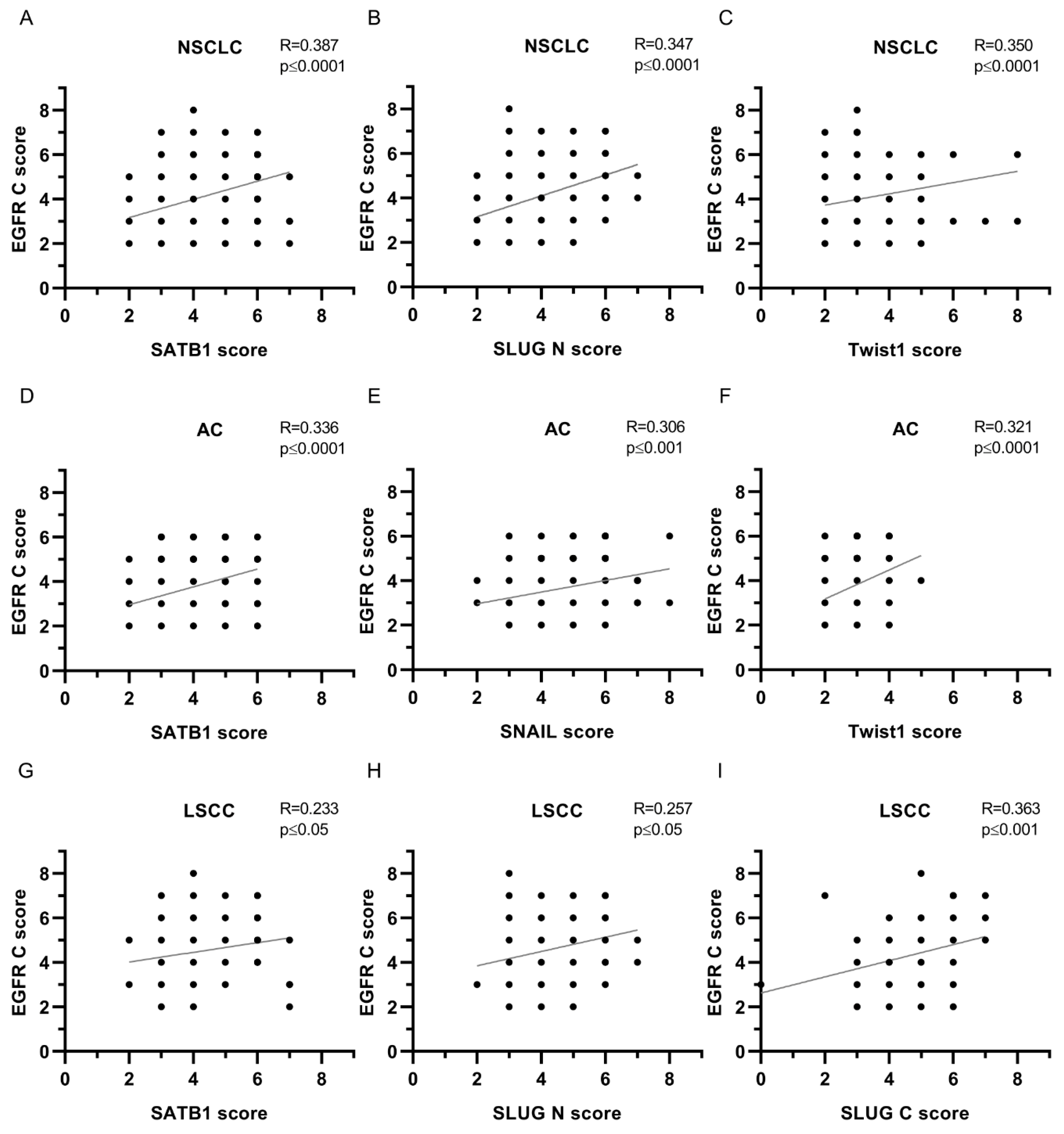

| SATB1 | 0.387 | **** | 0.336 | **** | 0.233 | * |

| Ki67 | 0.217 | *** | 0.084 | ns | 0.117 | ns |

| E-cadherin | 0.071 | ns | 0.015 | ns | 0.132 | ns |

| N-cadherin | 0.039 | ns | -0.138 | ns | 0.118 | ns |

| SNAIL | 0.220 | *** | 0.306 | *** | 0.008 | ns |

| SLUG N | 0.347 | **** | 0.248 | ** | 0.257 | * |

| SLUG C | 0.226 | *** | 0.203 | * | 0.363 | *** |

| Twist1 | 0.350 | **** | 0.321 | **** | 0.151 | ns |

| EGFR M | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | NSCLC | AC | LSCC | |||

| Spearman’s R | P-value | Spearman’s R | P-value | Spearman’s R | P-value | |

| SATB1 | 0.166 | ** | 0.044 | ns | 0.137 | ns |

| Ki67 | 0.186 | ** | 0.206 | * | 0.027 | ns |

| E-cadherin | 0.065 | ns | 0.053 | ns | 0.053 | ns |

| N-cadherin | 0.093 | ns | 0.072 | ns | 0.065 | ns |

| SNAIL | 0.093 | ns | 0.204 | * | -0.031 | ns |

| SLUG N | 0.184 | ** | 0.102 | ns | 0.135 | ns |

| SLUG C | 0.080 | ns | 0.063 | ns | 0.142 | ns |

| Twist1 | 0.075 | ns | 0.009 | ns | -0.041 | ns |

| EGFR mRNA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | NSCLC | AC | LSCC | |||

| Spearman’s R | P-value | Spearman’s R | P-value | Spearman’s R | P-value | |

| EGFR N | -0.196 | ** | -0.345 | *** | 0.094 | ns |

| EGFR C | -0.195 | ** | -0.260 | ** | -0.088 | ns |

| EGFR M | -0.081 | ns | 0.008 | ns | -0.149 | ns |

| SATB1mRNA | -0.078 | ns | -0.226 | ns | -0.092 | ns |

| SATB1 | -0.131 | ns | -0.170 | ns | -0.073 | ns |

| Ki67 | -0.021 | ns | 0.075 | ns | -0.153 | ns |

| E-cadherin | -0.011 | ns | 0.054 | ns | -0.180 | ns |

| N-cadherin | -0.128 | ns | -0.079 | ns | -0.165 | ns |

| SNAIL | -0.185 | * | -0.133 | ns | -0.283 | * |

| SLUG N | -0.251 | *** | -0.247 | ** | -0.260 | * |

| SLUG C | -0.118 | ns | -0.076 | ns | -0.188 | ns |

| Twist1 | -0.183 | * | -0.280 | ** | -0.048 | ns |

| Parameters | All cases (N=239) n (%) |

AC (N=149) n (%) |

LSCC (N=90) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 144 (60.2) | 85 (57.0) | 59 (65.6) |

| Female | 95 (39.8) | 64 (43.0) | 31 (34.4) |

| Age | |||

| Mean | 66.21±7.69 | 65.84±8.16 | 66.83±6.84 |

| Range | 44-84 | 44-84 | 44-82 |

| Malignancy grade | |||

| G1 | 3 (1.3) | 3 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| G2 | 149 (62.3) | 72 (48.3) | 77 (85.6) |

| G3 | 87 (36.4) | 74 (49.7) | 13 (14.4) |

| Tumour size | |||

| pT1 | 75 (31.4) | 56 (37.6) | 19 (21.1) |

| pT2 | 122 (51.0) | 65 (43.6) | 57 (63.3) |

| pT3 | 23 (9.6) | 11 (7.4) | 12 (13.3) |

| pT4 | 5 (2.1) | 4 (2.7) | 1 (1.1) |

| No data | 23 (9.6) | 13 (8.7) | 1 (1.1) |

| Lymph nodes | |||

| pN0 | 144 (60.2) | 82 (55.0) | 62 (68.9) |

| pN1 | 40 (16.7) | 23 (15.4) | 17 (18.9) |

| pN2 | 41 (17.2) | 31 (20.8) | 10 (11.1) |

| No data | 14 (5.9) | 13 (8.7) | 1 (1.1) |

| Stage | |||

| I | 102 (42.7) | 64 (43.0) | 38 (42.2) |

| II | 76 (31.8) | 36 (24.2) | 40 (44.4) |

| III | 45 (18.8) | 34 (22.8) | 11 (12.2) |

| IV | 2 (0.83) | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| No data | 14 (5.9) | 13 (8.7) | 1 (1.1) |

| Overall survival | |||

| Deaths | 94 (39.3) | 62 (41.6) | 32 (35.6) |

| Alive | 144 (60.3) | 86 (57.7) | 58 (64.4) |

| No data | 1 (0.42) | 1 (0.67) | 0 (0.0) |

| Parameters | All cases (N=170) n (%) |

AC (N=104) n (%) |

LSCC (N=66) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 104 (61.18) | 58 (55.77) | 46 (69.70) |

| Female | 66 (38.82) | 46 (44.23) | 20 (30.30) |

| Age | |||

| Mean | 66.21±7.42 | 65.70±7.93 | 67.03±6.49 |

| Range | 44-82 | 44-82 | 52-82 |

| Malignancy grade | |||

| G1 | 1 (0.59) | 1 (0.96) | 0 (0.0) |

| G2 | 105 (61.76) | 49 (47.11) | 56 (84.85) |

| G3 | 64 (37.65) | 54 (51.92) | 10 (15.15) |

| Tumour size | |||

| pT1 | 51 (30.00) | 36 (34.61) | 15 (22.73) |

| pT2 | 87 (51.18) | 47 (45.19) | 40 (60.61) |

| pT3 | 16 (9.41) | 6 (5.77) | 10 (15.15) |

| pT4 | 5 (2.94) | 4 (3.85) | 1 (1.51) |

| No data | 11 (6.47) | 11 (10.58) | 0 (0.0) |

| Lymph nodes | |||

| pN0 | 105 (61.76) | 58 (55.77) | 47 (71.21) |

| pN1 | 23 (13.53) | 12 (11.54) | 11 (16.67) |

| pN2 | 31 (18.24) | 23 (22.11) | 8 (12.12) |

| No data | 11 (6.47) | 11 (10.58) | 0 (0.0) |

| Stage | |||

| I | 70 (41.18) | 45 (43.27) | 25 (37.88) |

| II | 53 (31.18) | 21 (20.19) | 32 (48.48) |

| III | 34 (20.00) | 25 (24.03) | 9 (13.64) |

| IV | 2 (1.18) | 2 (1.92) | 0 (0.0) |

| No data | 11 (6.47) | 11 (10.58) | 0 (0.0) |

| Overall survival | |||

| Deaths | 100 (58.82) | 42 (40.38) | 39 (59.09) |

| Alive | 69 (40.59) | 61 (58.65) | 27 (40.91) |

| No data | 1 (0.59) | 1 (0.96) | 0 (0.0) |

| Score | Percentage of the positive cells and intensity of the staining |

|---|---|

| 0 | No staining is observed or staining is observed in <10% of the tumour cells |

| 1 | A faint membrane staining is observed in >10% of the tumour cells |

| 2 | A weak or moderate, complete membrane staining is observed in >10% of the tumour cells |

| 3 | A strong, complete membrane staining is observed in >10% of the tumour cells |

| Target molecule | Gene name | Probe number |

|---|---|---|

| mRNA for EGFR protein | EGFR | VA1-11736-VT (Thermo Fisher Scientific) |

| mRNA for SATB1 protein | SATB1 | VA1-13726-VT (Thermo Fisher Scientific) |

| 18S ribosomal RNA | 555RN18S1 | VA1-3020734-VT (Thermo Fisher Scientific) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).