Submitted:

04 October 2024

Posted:

07 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

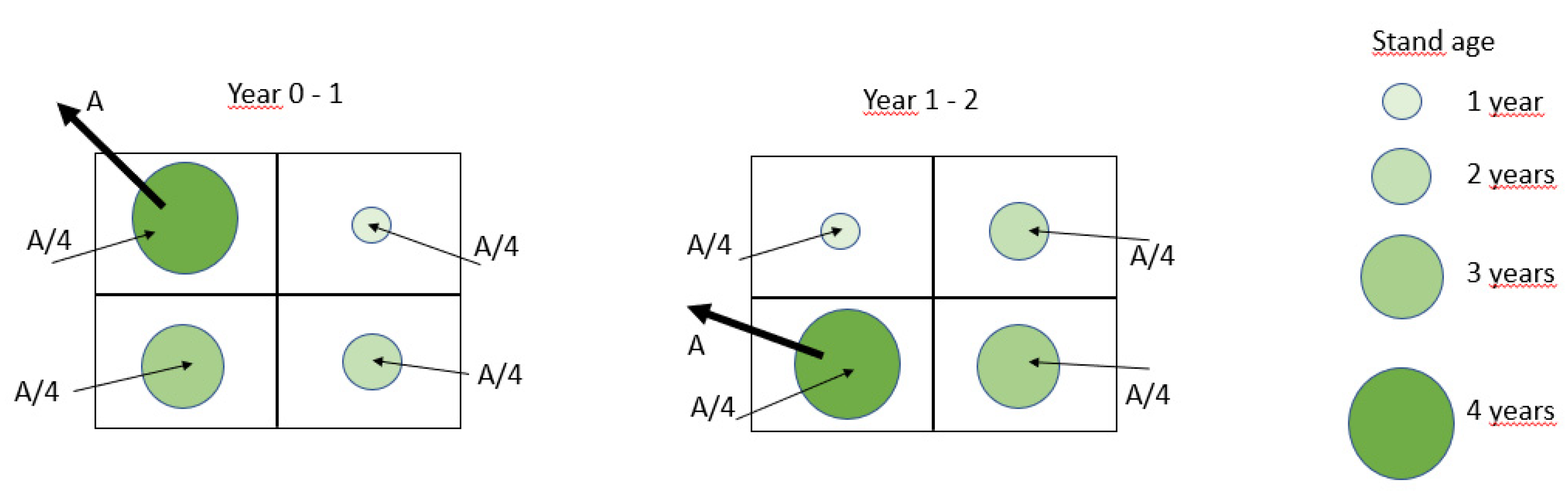

2.1. Qualitative Overview

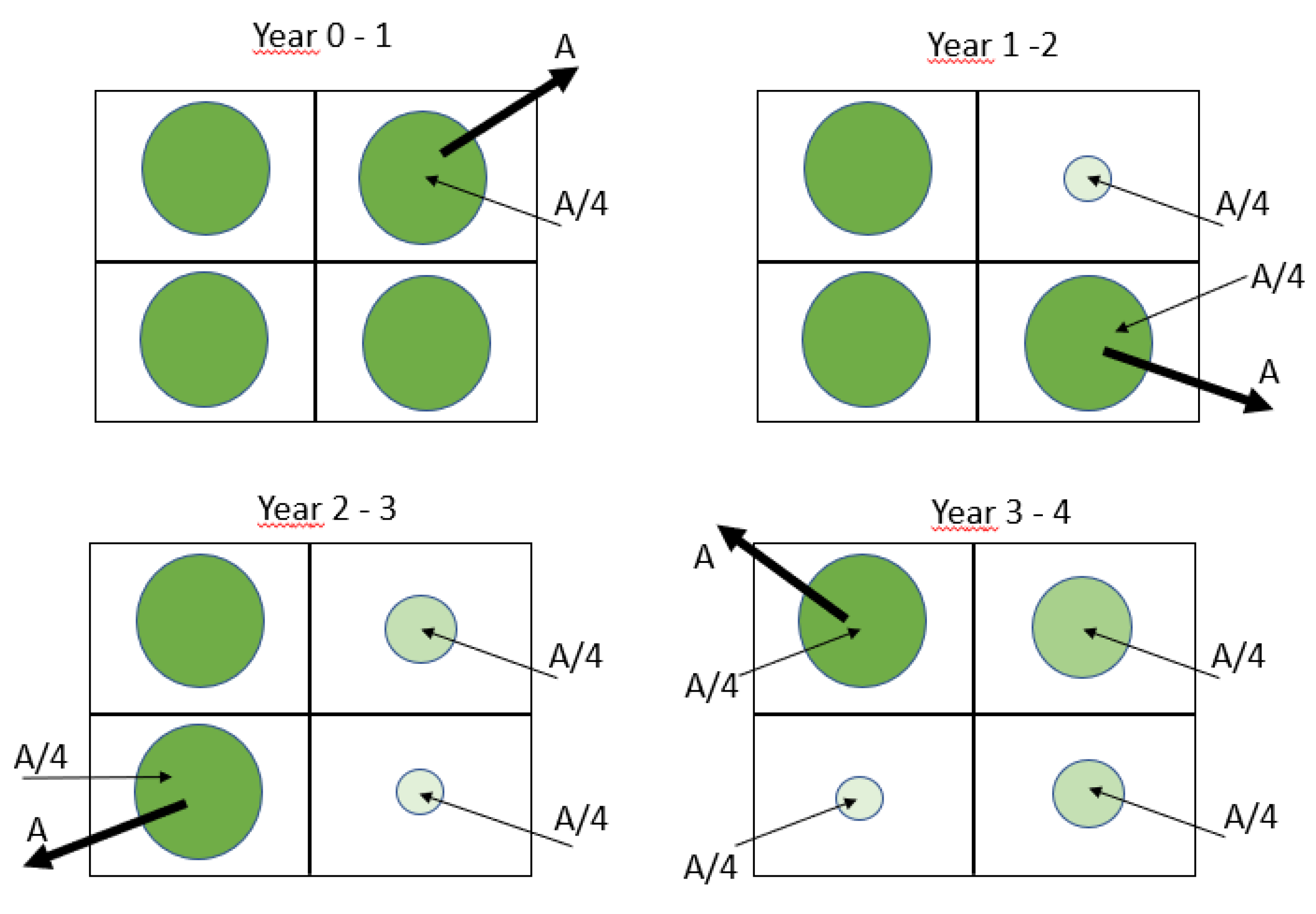

2.2. Analytical Approach

3. Results

3.1. General

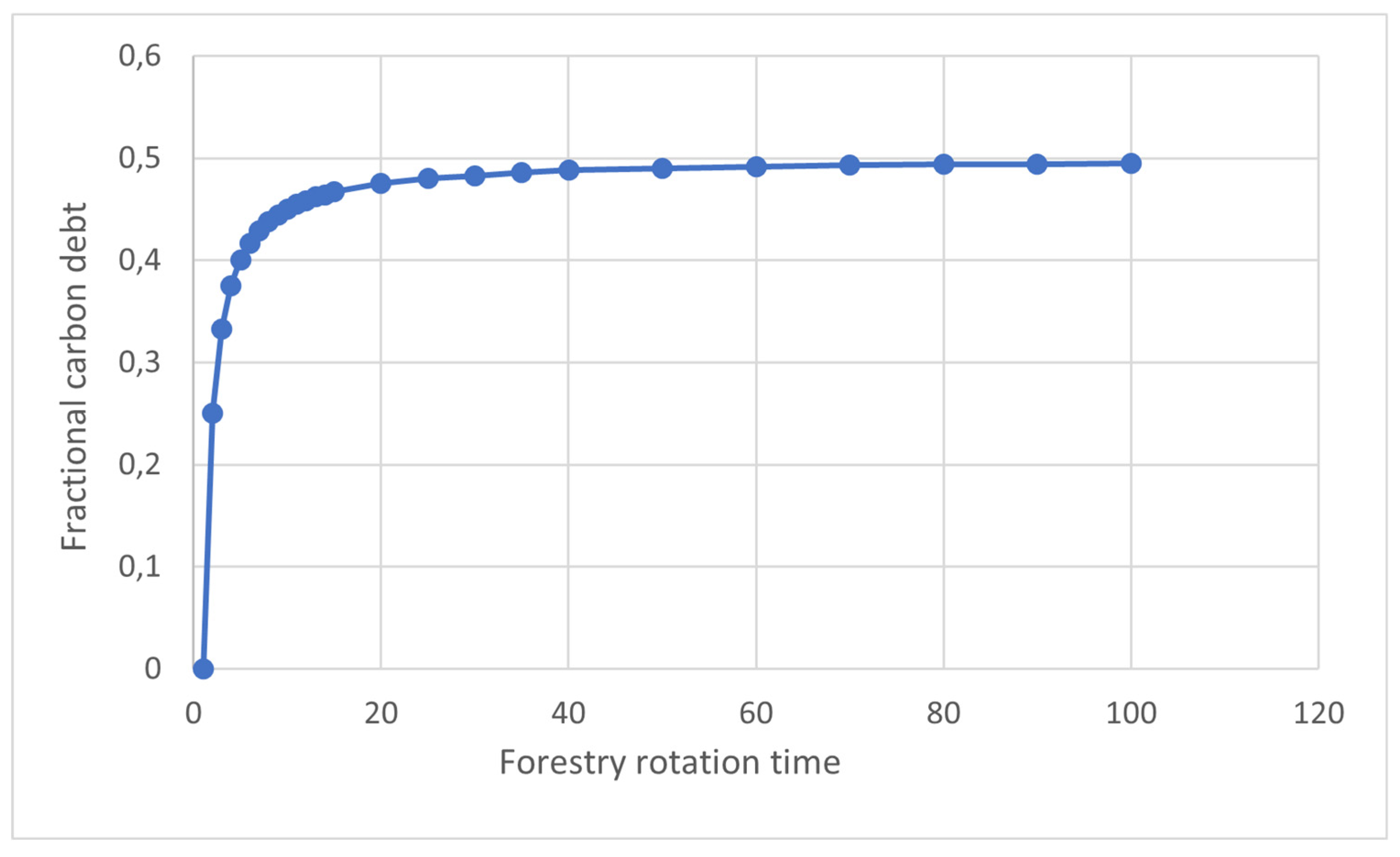

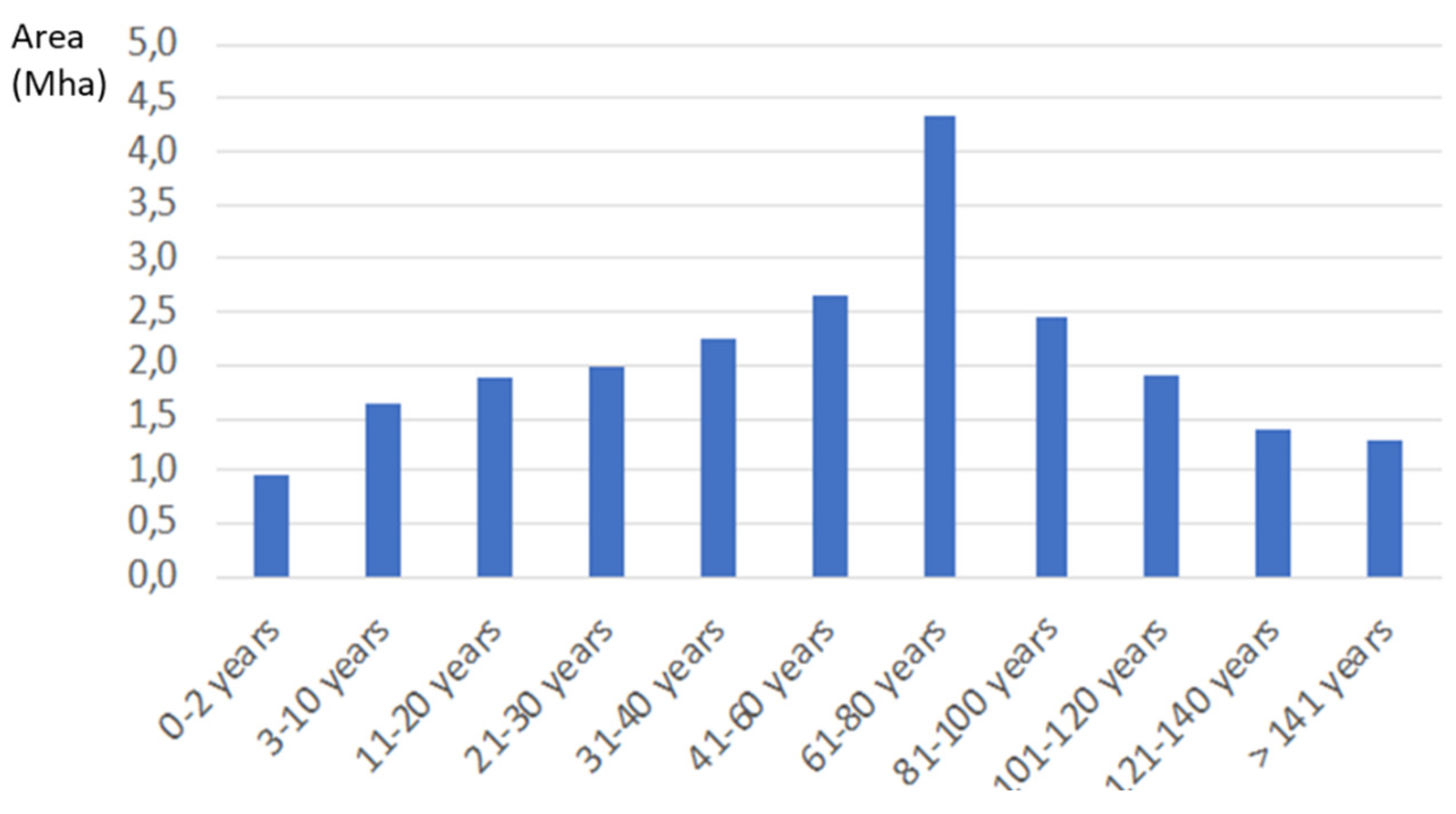

3.2. Case Study: Sweden

3.2.1. Swedish Total Climate Gas Emissions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- J. R. Malcolm, B. Holtsmark, and P. W. Piascik. Forest harvesting and the carbon debt in boreal east-central Canada. Clim Change 2020, 161, 433–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. R. Mitchell, M. E. Harmon, and K. E. B. O’Connell. Carbon debt and carbon sequestration parity in forest bioenergy production. GCB Bioenergy 2012, 4, 818–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. -D. Schulze, C. Körner, B. E. Law, H. Haberl, and S. Luyssaert. Large-scale bioenergy from additional harvest of forest biomass is neither sustainable nor greenhouse gas neutral. GCB Bioenergy 2012, 4, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Zanchi, N. Pena, and N. Bird. Is woody bioenergy carbon neutral? A comparative assessment of emissions from consumption of woody bioenergy and fossil fuel. GCB Bioenergy 2012, 4, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repo, J.-P. Tuovinen, and J. Liski. Can we produce carbon and climate neutral forest bioenergy? GCB Bioenergy 2015, 7, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, J. B. Kirkpatrick, and A. J. Friedland. Conventional intensive logging promotes loss of organic carbon from the mineral soil. Glob Chang Biol 2017, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. N. Stokland. Volume increment and carbon dynamics in boreal forest when extending the rotation length towards biologically old stands. For Ecol Manage 2021, 488, 119017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. S. Bentsen. Carbon debt and payback time – Lost in the forest? Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 73, 1211–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Soimakallio, T. Kalliokoski, A. Lehtonen, and O. Salminen. On the trade-offs and synergies between forest carbon sequestration and substitution. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Chang 2021, 26, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Q. Wang, J. Han, Z. Haq, W. E. Tyner, M. Wu, and A. Elgowainy. Energy and greenhouse gas emission effects of corn and cellulosic ethanol with technology improvements and land use changes. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 1885–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Leturcq. GHG displacement factors of harvested wood products: the myth of substitution. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 20752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- V. Daioglou et al. Greenhouse gas emission curves for advanced biofuel supply chains. Nat Clim Chang 2017, 7, 920–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. D. Searchinger, S. Wirsenius, T. Beringer, and P. Dumas. Assessing the efficiency of changes in land use for mitigating climate change. Nature 2018, 564, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. E. Harmon. Have product substitution carbon benefits been overestimated? A sensitivity analysis of key assumptions. Environmental Research Letters 2019, 14, 065008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Merfort et al. Bioenergy-induced land-use-change emissions with sectorally fragmented policies. Nat Clim Chang, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Haberl et al. Correcting a fundamental error in greenhouse gas accounting related to bioenergy. Energy Policy 2012, 45, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Babiker et al. Cross-sectoral perspectives. In IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. M. DeCicco and W. H. Schlesinger. Reconsidering bioenergy given the urgency of climate protection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 9642–9645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. R. et al. Shukla. Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Working Group III Contribution to the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Lewis, C. E. Wheeler, E. T. A. Mitchard, and A. Koch. Restoring natural forests is the best way to remove atmospheric carbon. Nature 2019, 568, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Rogers et al. Using ecosystem integrity to maximize climate mitigation and minimize risk in international forest policy. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. -H. Erb et al. Unexpectedly large impact of forest management and grazing on global vegetation biomass. Nature 2018, 553, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Skytt, G. Englund, and B.-G. Jonsson. Climate mitigation forestry—temporal trade-offs. Environmental Research Letters 2021, 16, 114037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Seppälä et al. Effect of increased wood harvesting and utilization on required greenhouse gas displacement factors of wood-based products and fuels. J Environ Manage 2019, 247, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T. Hammar and F. Levihn. Time-dependent climate impact of biomass use in a fourth generation district heating system, including BECCS. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 138, 105606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiffault, A. Gianvenuti, X. Zuzhang, and S. Walter, The role of wood residues in the transition to sustainable bioenergy. FAO, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Cowie et al. Applying a science-based systems perspective to dispel misconceptions about climate effects of forest bioenergy. GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13, 1210–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deahl, L. Walloe, and M. Norton. EASAC Open Letter to IEA-Bioenergy.” Accessed: Feb. 11, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://easac.eu/news/details/iea-bioenergy-critique-of-easac-publications-on-forest-bioenergy/.

- United Nations Climate Change. Reporting and accounting of LULUCF activities under the Kyoto Protocol. 2008. Accessed: Feb. 19, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://unfccc.int/topics/land-use/workstreams/lulucf-under-the-kyoto-protocol/reporting-and-accounting-of-lulucf-activities-under-the-kyoto-protocol.

- European Commission. Taxonomy Regulation. https://ec.europa.eu/finance/docs/level-2-measures/taxonomy-regulation-delegated-act-2021-2800-annex-1_en.pdf.

- S. Luyssaert et al. The European carbon balance. Part 3: forests. Glob Chang Biol 2010, 16, 1429–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Quéré; et al. Global Carbon Budget 2018. Earth Syst Sci Data 2018, 10, 2141–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Högberg et al. Sustainable boreal forest management – challenges and opportunities for climate change mitigation. 2021, Accessed: Feb. 20, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.skogsstyrelsen.se/globalassets/om-oss/rapporter/rapporter-20222021202020192018/rapport-2021-11-sustainable-boreal-forest-management-challenges-and-opportunities-for-climate-change-mitigation-002.pdf.

- Y. Huang et al. Impacts of species richness on productivity in a large-scale subtropical forest experiment. Science (1979) 2018, 362, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, C. Real, J. G. Álvarez-González, and M. A. Rodríguez-Guitián. Forest structure and C stocks in natural Fagus sylvatica forest in southern Europe: The effects of past management. For Ecol Manage 2007, 250, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Keith, B. G. Mackey, and D. B. Lindenmayer. Re-evaluation of forest biomass carbon stocks and lessons from the world’s most carbon-dense forests. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 11635–11640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Pelkman. IEA Bioenergy Countries’ Report – update 2021. IEA Bioenergy https://www.ieabioenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/CountriesReport2021_final.pdf.

- Swedish Forest Agency. Forestry Production. https://www.skogsstyrelsen.se/en/statistics/.

- S. Swedish Official Statistics. Skogsdata 2022. Umeå, 2022. Accessed: May 13, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.slu.se/globalassets/ew/org/centrb/rt/dokument/skogsdata/skogsdata_2022_webb.pdf.

- Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. UN GHG National Inventiry Report Sweden.” Accessed: Feb. 11, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://unfccc.int/documents/461776.

- M. Crippa, D. Guizzardi, E. Solazzo, and M. Muntean. European Commission, JRC Report: GHG emissions of all world countries. 2021. Accessed: Feb. 11, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/173513.

- P. Wikström et al. THE HEUREKA FORESTRY DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEM: AN OVERVIEW. Mathematical and Computational Forestry & Natural-Resource Sciences 2011, 3, 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- L. Peng, T. D. L. Peng, T. D. Searchinger, J. Zionts, and R. Waite. The carbon costs of global wood harvests. Nature, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. U. Department of Forest Resource Management. Skogsdata (Forest data) 2023. https://www.slu.se/globalassets/ew/org/centrb/rt/dokument/skogsdata/skogsdata_2023_webb.pdf.

- IRENA. Bioenergy from boreal forests: Swedish approach to sustainable wood use. Abu Dhabi, 2019. Accessed: Feb. 25, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2019/Mar/IRENA_Swedish_forest_bioenergy_2019.pdf.

- H. Keith et al. Accounting for Biomass Carbon Stock Change Due to Wildfire in Temperate Forest Landscapes in Australia. PLoS One 2014, 9, e107126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. E. Harmon, C. T. Hanson, and D. A. DellaSala. Combustion of Aboveground Wood from Live Trees in Megafires, CA, USA. Forests 2022, 13, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. W. Meigs, D. C. Donato, J. L. Campbell, J. G. Martin, and B. E. Law. Forest Fire Impacts on Carbon Uptake, Storage, and Emission: The Role of Burn Severity in the Eastern Cascades, Oregon. Ecosystems 2009, 12, 1246–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Campbell, D. Donato, D. Azuma, and B. Law. Pyrogenic carbon emission from a large wildfire in Oregon, United States. J Geophys Res Biogeosci 2007, 112, G4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindroth. Clarifying the carbon balance recovery time after clear-cutting. Glob Chang Biol 2023, 29, 4178–4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. Linder and L. Östlund. Structural changes in three mid-boreal Swedish forest landscapes, 1885–1996. Biol Conserv 1998, 85, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Davis, B. Sohngen, and D. J. Lewis. The effect of carbon fertilization on naturally regenerated and planted US forests. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 5490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinerstein, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. A Global Deal For Nature: Guiding principles, milestones, and targets. Sci Adv 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parlament. Deforestation Regulation. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2022-0311_EN.pdf.

- K. B. Lindahl et al. The Swedish forestry model: More of everything? For Policy Econ 2017, 77, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Angelstam et al. Sweden does not meet agreed national and international forest biodiversity targets: A call for adaptive landscape planning. Landsc Urban Plan 2020, 202, 103838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fossil | Biogenic | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sweden | 5 | 12 | 17 |

| USA | 16 | 2 | 18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).