1. Introduction

As large-scale application domains like scientific computing, social media, and financial analytics continue to expand, the computational and storage requirements of modern systems have surpassed the available resources. In the upcoming decade, it is anticipated that the amount of data managed by global data centers will increase by fifty times, while the number of processors will only grow by a factor of ten [

1]. This indicates that the demand for performance will soon outstrip resource allocations.

Furthermore, Information and Communication Technology (ICT) devices and services currently contribute significantly to the world’s overall energy consumption, with projections indicating that their energy demand will rise to nearly 21% by 2030 [

2] Consequently, it becomes evident that relying solely on over-provisioning resources will not suffice to address the impending challenges facing the computing industry.

In recent decades, significant technological advancements and increasing computational demands have driven a remarkable reduction in the size of integrated circuits and computing systems. This downscaling of CMOS technology has resulted in several key benefits, such as enhanced computational performance, improved energy efficiency, and the ability to increase the number of cores per chip. Smaller transistors allow for faster switching speeds, enabling higher clock frequencies, which translates to quicker data processing and more powerful computing systems. Additionally, as transistors shrink, the power required to switch them can be reduced, leading to lower overall energy consumption, which is crucial for mobile and battery-operated devices.

However, CMOS downscaling is not without its drawbacks. As transistors continue to shrink, the benefits of reduced supply voltage become less significant, and the leakage current (unwanted current that flows even when the transistor is off) becomes more pronounced, leading to higher static power consumption. Moreover, the exponential increase in power consumption due to higher clock frequencies has introduced thermal challenges, as more energy is dissipated as heat, which can damage the chip and reduce its lifespan. The combination of these factors means that the traditional benefits of CMOS scaling are diminishing, and the ability to further increase the number of cores per chip is constrained by power and thermal limits. Consequently, as CMOS technology reaches its scaling limits, it becomes imperative to explore alternative approaches, such as new materials, 3D stacking, or novel architectures, to continue improving computing efficiency without exacerbating these power and thermal issues [

3].

In addition to the trends mentioned above, the nature of the tasks fueling the demand for computing has evolved across the computing spectrum, spanning from mobile devices to the cloud. Within data centers and the cloud, the impetus for computing stems from the necessity to efficiently manage, organize, search, and derive conclusions from vast datasets. In contrast, the predominant computing demand for mobile and embedded devices arises from the desire for more immersive media experiences and more natural, intelligent interactions with users and the surrounding environment. Although computational errors are generally undesirable, a common thread runs through this spectrum: these applications are not primarily concerned with computing precise numerical outputs. Instead, "correctness" is defined as generating results that are sufficiently accurate to deliver an acceptable user experience [

4].

These applications inherently possess a resilience towards errors, meaning they can produce satisfactory outputs even when some of their computations are carried out in an approximate manner [

5]. For instance, in search and recommendation systems, there is not always a single definitive or "golden" result; instead, multiple answers falling within a specific range are considered acceptable. Additionally, iterative applications processing extensive data sets may terminate convergence prematurely or employ heuristics [

6]. In many machine learning applications, even if a golden result exists, the most advanced algorithms may not be able to achieve it. Consequently, users often have to settle for results that are reasonably inaccurate but still adequate. Furthermore, applications such as multimedia, wireless communication, speech recognition, and data mining exhibit a degree of tolerance toward errors. Human perceptual limitations signify that such errors may not significantly affect applications like image, audio, and video processing. Another example pertains to applications dealing with noisy input data (e.g., image and sensor data processing, and speech recognition). The noise in the input naturally leads to imprecise results, and approximations have a similar impact. In simpler terms, applications that can handle noisy inputs also possess the capability to withstand approximations [

7,

8,

9]. Finally, some applications utilize computational patterns like aggregation or iterative refinement, which can mitigate or compensate for the effects of approximations.

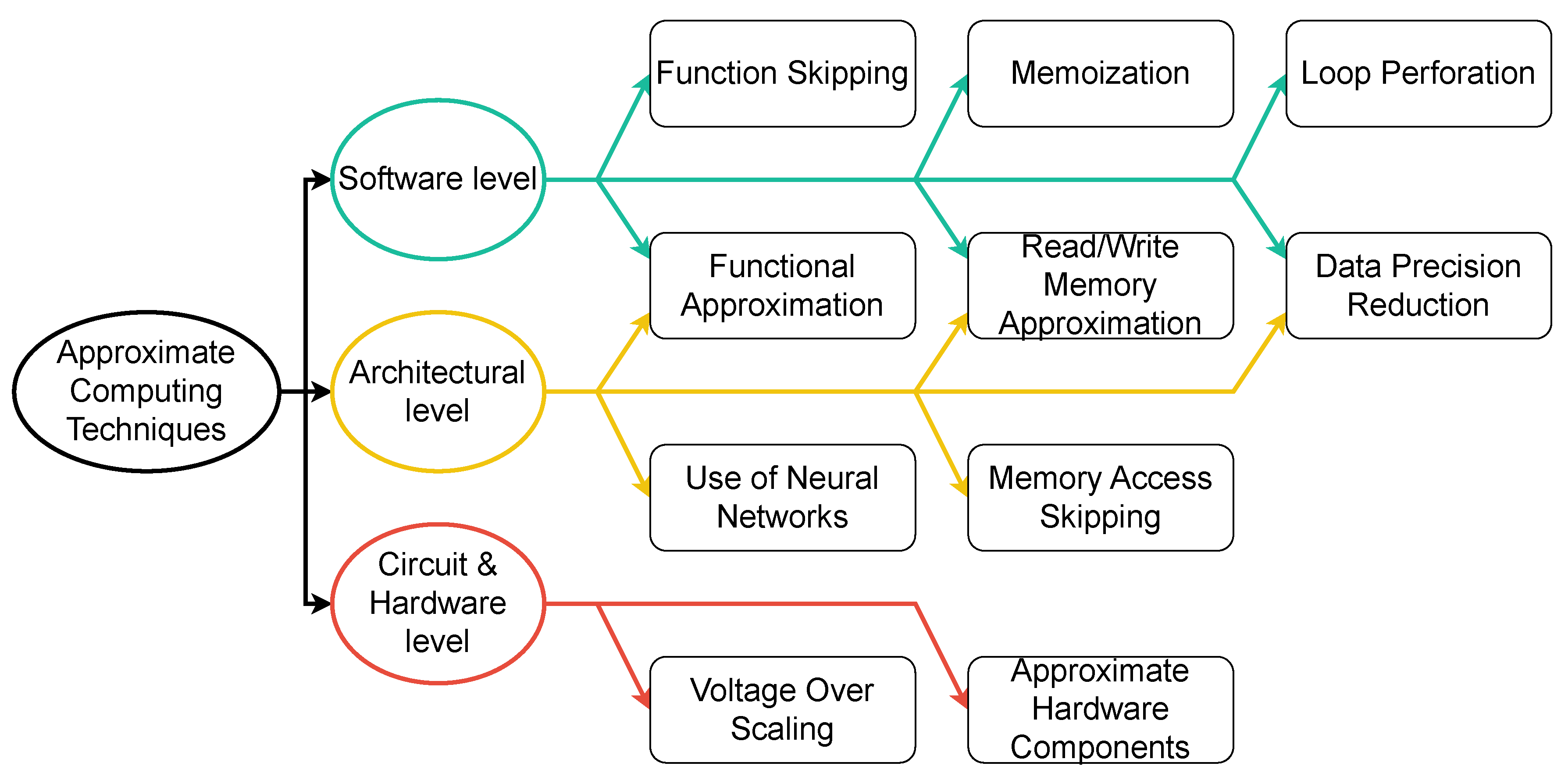

An encouraging approach to enhance computing efficiency is AxC. The concept of AxC encompasses a wide array of techniques that capitalize on the inherent error resilience of applications, ultimately leading to improved efficiency across all layers of the computing stack, ranging from the fundamental transistor-level design to software implementations. These techniques can have varying impacts on both the hardware and the quality of the output. AxC capitalizes on the existence of data and algorithms that can tolerate errors, as well as the limitations in the perception of end-users. It strategically balances accuracy against the potential for performance improvements or energy savings. In essence, it takes advantage of the gap that often exists between the level of accuracy that computer systems can provide and the level of accuracy required by the specific application or the end-users. This required accuracy is typically much lower than what the computer systems can deliver.

Leveraging AxC involves addressing a few aspects and challenges. The first challenge is identifying the segments within the targeted software or hardware component that can be candidates for approximation. Identifying segments of code or data that can be approximated may necessitate a comprehensive understanding of the application on behalf of the designer.

The second challenge is implementing the AxC technique to introduce approximations. On the one hand, there is a limit to the accuracy degradation that can be introduced so the output remains acceptable. On the other hand, the level of accuracy degradation and the performance improvements or energy savings varies depending on the selected AxC technique. Hence, available AxC techniques should be evaluated and compared to find the most suitable AxC technique tailored for a target application or design.

The next challenge is choosing the suitable error measurement criteria, often tailored to the particular application, and executing the actual error assessment process to ensure that the output adheres to the predefined quality standards [

5]. The error assessment usually involves simulating both the precise and approximate versions of applications. However, alternative methods like Bayesian inference [

10,

11] or Machine Learning (ML)-based approaches [

12] have been put forth in the scientific literature.

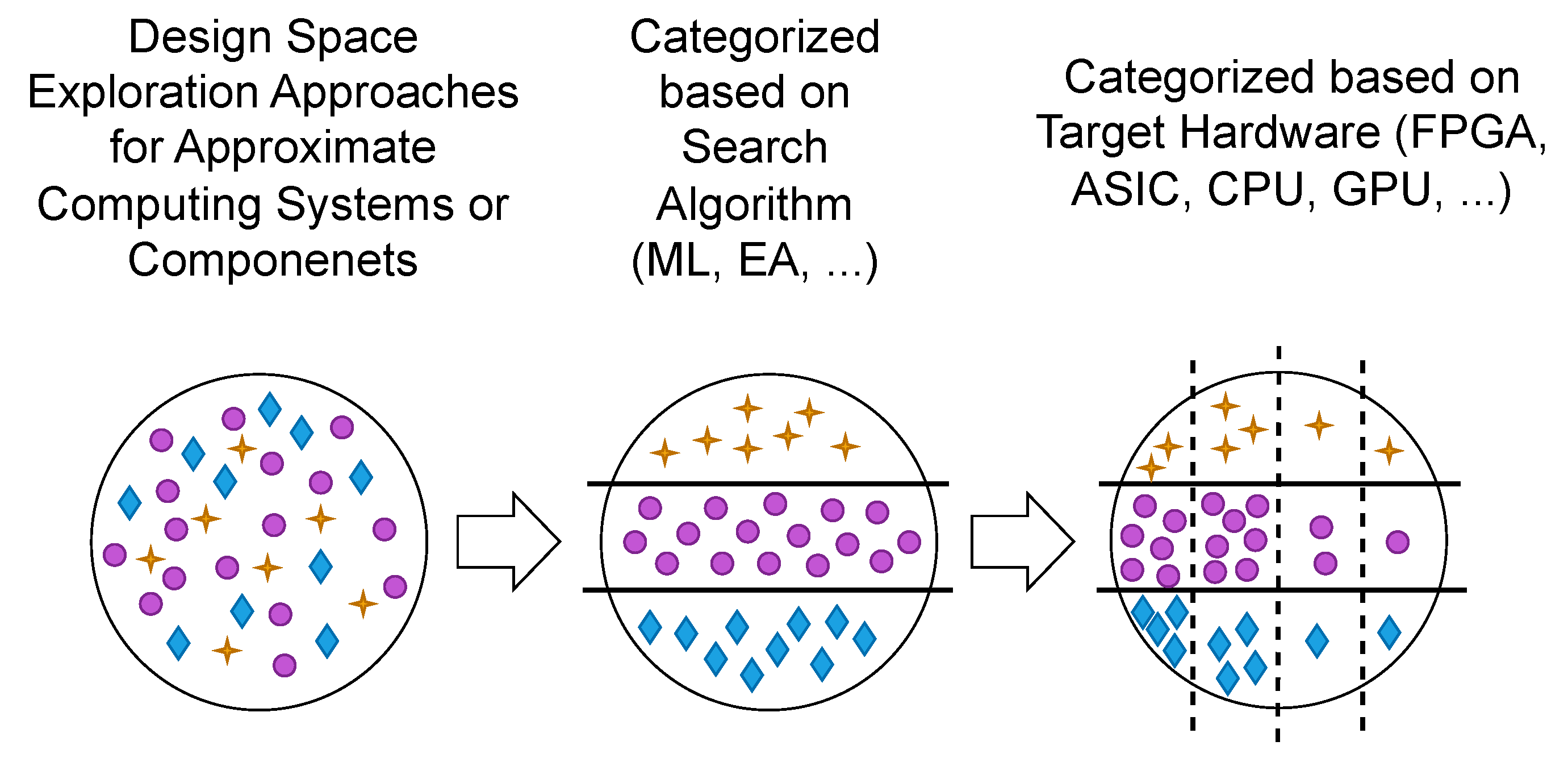

A DSE can be performed to address all the previously mentioned challenges. The goal of performing a DSE is to determine the most optimal approximate configurations from those generated by applying a given set of approximation techniques to the design. Hence, the DSE approaches can help systematically evaluate different approximate designs to choose the most suitable AxC techniques and, consequently, the best configurations for any given combination of AxC techniques. Early DSE approaches either combine multiple design objectives into a single-objective optimization problem or optimize a solitary parameter while keeping the remaining variables constant. More recent research, as seen in published works, has tackled circuit design issues by considering a mop to seek out Pareto-optimal approximate circuit configurations [

13]. Regrettably, these approaches predominantly concentrated on simple systems, specifically arithmetic components like adders and multipliers, as they form the foundational components for more intricate designs [

14].

This paper aims to cover different DSE approaches leveraged in comparing approximate versions of a target application or design. The structure of this paper is as follows: Firstly,

Section 2 provides a background on the AxC techniques and DSE approaches. Then, in

Section 3, the search methodology to find related studies and categorizing them, is explained. In

Section 4 DSE approaches to compare and choose suitable AxC techniques are reviewed and compared. Finally, a conclusion is provided in

Section 5.

4. Comparison and Analysis

This section provides an overview and comparison of the proposed DSE approaches in the literature for applying AxC techniques to programs or hardware designs. Though many different search algorithms have been proposed in the literature to explore the vast design space of approximate programs or hardware designs, two categories of algorithms are commonly leveraged: ML algorithms and ea. ML approaches often leverage data-driven techniques to predict and explore optimal design configurations, while ea use bio-inspired strategies such as ga to navigate the design space.

Table 2 provides information about the research works that took an ML approach to perform the DSE, while

Table 3 includes information about the research works that leveraged ea to perform the DSE. All the remaining research works that perform the DSE using other heuristic algorithms or combining different optimization algorithms are listed in

Table 4 and

Table 5. While

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5, and

Table 6 provide an overview to allow comparison among different studies based on the employed search algorithm, target hardware, and use case domain,

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10, and

Table 11 provide an overview of the same sets of studies to allow comparison among different studies based on AxC techniques applied in each study.

As reported in

Table 2, the most popular ML algorithm is RL [

38,

52,

56,

57]. While [

53] and [

54] use MBO and modified MCTS, respectively; [

12,

55] mention using ML based search algorithm. Among these research works, though the target hardware varies from fpga and asic to general-purpose cpu, the use-case domain always includes image and signal processing benchmarks, ranging from traditional image processing to image classification using nn. Moving the comparison to the AxC techniques applied at different levels, as reported in

Table 7, replacing the exact adders and multipliers with approximate counterparts is the most common hardware-level approximation investigated [

12,

38,

53,

54,

55]. However, the investigated software-level AxC techniques are noticeably application-specific: In [

52,

53], algorithm parameters - that indicate the iterations of executing a code basic block or the size of the inputs processed at each iteration - are decreased to reduce the execution time or program memory while sacrificing output accuracy. A similar approach of loop perforation is applied in [

56] alongside changing the input data structure. Interestingly, in [

57], an ML algorithm is employed to search the design space of an ML application, proposing a DSE framework to find the optimal quantization level for each layer of a dnn.

Table 3 lists the research works that leveraged ea to perform the DSE. Between the prominently used subsets of ea, an es algorithm is only used in [

60]. all approaches enlisted here, either use ga or its subset NSGA-II to explore the design space. More precisely, [

58,

59,

62] employ ga, [

60,

61] use NSGA-II, and [

63] developed a NAS algorithm based on NSGA-II. Comparing the target hardware of the reviewed research works, most works consider optimizing an accelerator design for fpga and asic implementation as expected, while [

63] targets gpu for optimizing cnn designs.

Comparing the benchmarks in

Table 3 to those listed in

Table 2, most of the benchmarks fall under the image processing category, though the types of benchmarks are slightly different. Comparing the applied AxC techniques, as reported in

Table 8,

58,

59] investigate employing sparse lut, precision scaling, and approximate adders for a pixel-streaming pipeline application accelerated with an fpga. Similarly, [

60,

61] explore using approximate adders and multipliers for optimizing video and image compression accelerators. In [

62], authors try to optimize benchmarks from different domains such as scientific computing, 3D gaming, 3D image rendering, signal, and image processing when the approximation is applied at a software level, altering the program static instructions. Distinctively, in [

63], authors propose approximating multipliers using lut and a customized approximate convolutional layer to support quantization-aware training of cnn and dynamically explore the design space. It is noteworthy that the aim is to optimize a cnn design usually trained on a gpu. Hence, approximation at the hardware level is not an option, while such AxC technique can be emulated at the software level.

Table 4 and

Table 5 report a list of reviewed papers that neither rely on ML nor ea to explore the design space. In [

70], authors mention using a TS algorithm, with potential integration of ga into the DSE framework. Notably, TS focuses on iteratively improving a single solution, whereas ga work with a population of solutions and evolve them over generations using crossover, mutation, or other genetic operators. Hence, taking a TS approach might not seem the best choice when the mop does not have a single optimum solution, and a Pareto Front of non-dominated solutions may represent the optima better. In [

72], authors select a GD approach to search the design space. Contrary to the fact that GD is a widely used optimization technique in ML, GD is not employed as a part of an ML search algorithm in the aforementioned work. All the remaining works in

Table 4 and

Table 5 employ custom algorithms. In some cases, the DSE includes multiple stages of exploration, where pruning techniques are used before applying the search algorithm to reduce the design space size or after applying the search algorithm to refine the obtained solution sets.

Table 4 categorizes studies by target hardware, starting with those focused on fpga and asic, and continues through

Table 5 with studies on optimized accelerator design.

Table 9 and

Table 10 report the AxC techniques applied in each study enlisted in

Table 4 and

Table 5. Similar to the other sets of studies presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3, only a few works reported in

Table 4 and

Table 5 are hardware-independent or target general-purpose cpu and gpu. The target hardware in [

64] includes both fpga and asic. In [

64], the DSE is performed to optimize a hardware accelerator design for a video processing application using approximate adders and logic blocks. Similarly, in [

65], the target hardware includes both fpga and asic. In this study, the DSE is performed to optimize the design of dnn accelerated using fpga and asic, while the AxC techniques applied are quantization techniques aimed at approximating the dnn design at the software level. [

66], performs the DSE with a heuristic search algorithm to optimize the hardware implementation of different functions used in a dnn vector accelerator. To apply approximation through logic isolation, the portions of logic in the circuit that consume significant power but contribute only minimally to output accuracy are identified. Then the DSE is performed to find the best trade-off between dnn classification accuracy and energy savings. It can be implied that the target hardware can be categorized as asic. In [

67,

68], the DSE is performed with custom algorithms, applying hardware approximations to hardware implementations of video and image processing benchmarks. The target hardware in these studies can be categorized as asic. In [

69,

70], the authors propose to modify the HLS tools to study the approximation effects.

Continuing through

Table 5,

71] performs the DSE to optimize hardware accelerator design, investigating both hardware level and software level approximation techniques. Other three works also perform the DSE to optimize the accelerator design, specifically for ML applications [

72,

73,

74]. In [

75], authors target a very different type of acceleration using npu. While the use of npu for acceleration purposes can be categorized as applying approximation at the architectural level, the target hardware can be classified in the asic category. Though in [

76], the target hardware is not explicitly mentioned; the proposed methodology applies to any DSE performed on general-purpose cpu as target hardware. In [

77], authors perform the DSE to find the best configuration when applying their proposed hardware level approximation technique which is specific to gpu. However, the approximation technique is also applied to some benchmarks executed on general-purpose cpu to provide a fair comparison between the results obtained by performing the DSE for both hardware targets.

Comparing the use case domains across

Table 4 and

Table 5, image and signal processing are the prevalent categories of applications. Moreover, ML applications for image and text classification, pattern and speech recognition, and NLP tasks are considered in many works. Some works also target image compression tasks. Many works include matrix multiplication, DCT, FIR, and Sobel filters in their studies, as these functions are crucial for many image-processing tasks. Some works also consider benchmarks from financial analysis, robotics, 3D gaming, and scientific computing domains.

Considering the AxC techniques mentioned in

Table 9 and

Table 10, studies in [

64,

67,

70,

71,

76] investigate using approximate adders and multipliers. In [

66], authors propose applying a hardware-level AxC technique called logic isolation using latches or AND/OR gates at the inputs, MUXes at the output, and power gating. In [

68], authors propose applying another hardware-level AxC technique called Clock-gating, alongside the precision reduction of primary inputs at the RTL level. Similarly, [

72] proposes to apply a Clock Overgating technique. In [

71], authors propose to use VOS alongside approximate adders and multipliers at the hardware level, while approximating the additions and multiplications also on the software level. In [

69], authors propose very different AxC techniques: Internal Signal Substitution, and Bit-Level Optimization at the RTL level, Functional Unit Substitution (additions and multiplications) at the HLS level, and Source-Code Pruning Based on Profiling at the software level. Also, in [

73,

74], authors propose applying AxC techniques at multiple levels while designing an AI accelerator. They propose applying precision reduction to dnn data, as well as using approximated versions of fundamental dnn functions such as activation functions, pooling, normalization, and data shuffling in the network accelerator design. Though also aiming at optimizing dnn designs, authors in [

65] propose to apply AxC techniques at the software level to enable dynamic quantization of the dnn during the training phase. Interestingly, in [

75], authors propose to use a very different AxC technique compared to all of these reviewed studies. The proposed approach includes approximating the entire program using an npu as an accelerator. Another interesting AxC technique is proposed in [

77] to tackle memory bottlenecks while executing the program on a gpu and transferring the data from cpu to gpu and vice versa.

Some studies in the literature propose approaches to efficiently explore the design space for approximate logic synthesis and consider approximate versions of circuits generated by approximating selected portions (or sub-functions) of Boolean networks. These studies are reported separately in

Table 6, while the applied AxC techniques in these studies are reported in

Table 11. The approximation is applied at the hardware level and involves logic falsification in [

78,

80]. The approximation technique in [

79] is based on Boolean network simplifications allowed by exdc. The approximation in [

81] is based on BMF for truth tables. And, in [

82], a customized approximation of Boolean networks is applied. The search algorithm to explore the design space is an NSGA-II in [

78,

80,

82] while in [

79,

81] authors employ customized and heuristic algorithms. While the benchmarks for all of these studies include well-known approximate adders and multipliers in the literature, other circuits such as ALUs, decoders, shifters, and multiple combinational circuits have been employed as benchmarks. Interestingly, in [

80], the study targets safety-critical applications. The Quadruple Approximate Modular Redundancy (QAMR) approach is opposed to Triple Modular Redundancy (TMR), where all modules are exact circuits.

While

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5, and

Table 6 provide an overview to allow comparison among different studies based on employed search algorithm, target hardware, use case domain,

Table 12,

Table 13,

Table 14,

Table 15, and

Table 16 provide an overview of the same sets of studies to allow comparison among different studies based on evaluated parameters involved in the trade-off imposed by approximation.

Since AxC trades off accuracy for performance and energy efficiency, the first important parameter to evaluate during DSE is accuracy. Depending on the approximation goals, parameters measured during DSE in different studies may vary.

Predictably, power consumption is a key parameter frequently targeted in the reviewed studies, as it directly impacts energy efficiency. However, many studies choose to target energy consumption instead of power consumption. This approach is entirely valid because energy savings inherently indicate power savings, considering that energy is the product of power and time. By measuring energy directly, these studies effectively capture the combined impact of power reduction and execution time, providing a comprehensive view of the gains in efficiency achieved through AxC techniques.

The second most in-demand parameter, especially when designing accelerators, is the circuit area. Understandably, when approximations are applied to optimize a design, specifically in the case of employing the design on fpga, reducing the area utilization or LUT count is one of the approximation goals.

After area, performance and execution time are the most commonly measured parameters. In applications such as ann, where execution time is inherently high, one of the primary goals of applying approximation is to reduce this execution time, particularly for inference and, when feasible, training. The lengthy execution times of these applications also directly impact the DSE time, as evaluating even a few approximate instances can become highly time-consuming. While typical application execution times may range from seconds to minutes, the DSE time needed to explore and evaluate possible approximations often extends to hours or days. In the case of ann, the execution time for inference alone can take hours, and the DSE time required to assess even a limited number of approximate instances can span several days. Therefore, in applications where the execution time is already considerable and hence a primary target to trade-off with accuracy, proposing DSE methodologies that can assess more approximate instances in a reasonable time becomes crucial.

Memory utilization is often the least frequently evaluated parameter in the reviewed studies. Many AxC techniques are primarily applied to optimize execution time, energy, or performance, rather than specifically targeting memory utilization. However, these techniques can still impact memory utilization. For instance, some techniques aimed at reducing execution time, energy consumption, or improving performance may also affect memory usage as a secondary outcome. This indirect influence on memory is an important consideration, even though it is not the primary focus of these techniques. For example, in [

52] authors propose to explore the design space comprised of approximate versions of an iris scanning pipeline. The approximation includes reducing the search window size and the region of interest in iris images, reducing the parameters of iris segmentation, and reducing the kernel size of the filter. Though the main target is to reduce program execution time, the memory needed to store the intermediate and final output images and program parameters is reduced. In [

77], authors propose an AxC technique to mitigate the bottlenecks of limited off-chip bandwidth and long access latency, when the data is transferred from cpu to gpu and back. When a cache miss happens, RFVP predicts the requested values. In this case, the main goal of approximation is to achieve off-chip memory bandwidth consumption reduction, while speedup and energy reductions are also reported.

Through

Table 12,

Table 13,

Table 14,

Table 15, and

Table 16, besides the accuracy column, there is an error metric(s) column that reports the error metric(s) presented in each study to measure accuracy degradation due to applying approximation. Among all the parameters mentioned - power consumption, execution time, performance, memory utilization, and circuit area - accuracy is unique because the metrics used to measure accuracy degradation are often more complex and application-specific. For example, while power consumption differences are reported simply as ED between the measurements from approximate and exact versions, accuracy degradation error metrics involve a variety of sophisticated measures that are tailored to the specific application domain. In

Table 1, the most popular error metrics are listed.

Finally, every proposed DSE approach results in a solution or a set of optimal solutions for the mop. In some cases, an optimal solution exists. In many other cases, no global optimal solution can be found, and a Pareto Front (a set of non-dominated solutions) is presented. The last column in

Table 12,

Table 13,

Table 14,

Table 15, and

Table 16 indicates the studies that reported a Pareto Front as the result of the DSE performed, or at least compared a set of solutions resulted from the proposed DSE approach with a Pareto Front obtained by exhaustive search or other methods. In most cases, the obtained Pareto Front shows a trade-off between accuracy on the one hand, and an evaluated parameter such as energy efficiency, on the other hand, [

12,

52,

53,

54,

56,

58,

59,

60,

61,

63,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82].

The rest of the reviewed studies that did not obtain a Pareto Front but provided other analysis methods for comparing the DSE results are considered hereafter.

In some studies, a single threshold or multiple thresholds for the acceptable accuracy degradation was set, and then the DSE was performed for each accuracy threshold. For example, in [

55], a solution was provided for each accuracy threshold. In [

64], performance is plotted for different accelerator designs. However, no Pareto front is provided. Also, in [

66], three different dnn accuracy thresholds were set, and the DSE was performed for each threshold. Hence, the plots show the energy reductions for each dnn accuracy threshold instead of a Pareto front. Similarly, in [

72], the plots show the energy reductions for each dnn accuracy threshold instead of a Pareto front.

In [

57], two application-specific error metrics were proposed to evaluate the accuracy for dnn quantization and plot the quantization space Pareto frontier for these two error metrics called State of Relative Accuracy and State of Quantization.

In [

38], an RL approach was selected for performing the DSE, and steps of exploration have been plotted for evaluated parameters, including accuracy; however, a Pareto front is not obtained. In [

62], plots show the accuracy and energy against multiple thresholds for the number of program instructions to be approximated. However, a comparison to the Pareto front is not provided.

In [

65], the quantization is applied dynamically during training and inference of the dnn. Therefore, the plots show the changes in the dnn accuracy concerning the number of MACs used in the computations. Also, in the same plot, the results are compared to other quantization-aware approaches in the literature instead of comparing the results with a Pareto front obtained by other DSE methods. Since in dynamic approximation of the dnn, the changes in accuracy during the training or inference are more representative of the approach effectiveness, plotting a Pareto front seems unnecessary.

In [

73] and the previous studies with the same framework [

74], no Pareto front was presented. Instead, for each dnn, compute efficiency, training throughput, and inference latency were reported. In [

75], an npu is employed as an accelerator for a frequently executed region of code or function to approximate the function by replacing it with a neural network. Since an ann is employed, similar to other works on ann, multiple thresholds for function quality loss, or in other words, different ann accuracy levels, were investigated. Hence, the speedup and energy reduction for multiple thresholds of function quality loss were plotted. In consequence, no Pareto front was demonstrated.