1. Introduction

Water buffalo (

Bubalus bubalis swamp-type) is an economically important livestock species in Southeast Asia, including the Philippines. The Philippine carabao or native swamp buffalo was considered as the Philippines’ national animal. In addition, these species are robust and adaptable to harsh environments and display resiliency or susceptibility to pathogens [

1,

2]. These characteristics play an essential role in areas where they thrive best. The native carabao is the farmer’s best companion as the source of draft power in the rural farming communities. This animal was also the source of meat, milk, and organic fertilizer, which are important for a sustainable agriculture system [

3]. Despite their economic contribution to the livelihood of the farmers and livestock industry, the Philippine carabao is facing threats and challenges.

In developing countries, the market demand for a consistent source of the product usually dictates the livestock industry trends. The domestic livestock sector’s response to the market signals that has a negative tendency to reduce the number of breeds. In addition, others responded to market demand that required the utilization of imported genetic resources, which resulted in the loss of local or domestic animal diversity. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) reported in 2000 on the status of the world’s breeds that had a loss of genetic variation: 12% have become extinct, 17% are endangered, 9% are in critical condition, and 39% are not at risk [

4]. In the Philippines, conserving swamp buffaloes would resolve various concerns such as uncontrolled crossbreeding, high animal market demand, and drastic effects due to climate change.

Through artificial insemination (AI) service, crossbreeding is commonly practiced in the country to produce crossbred offspring (swamp x riverine) or upgraded swamp buffalo. The crossbreeding program aims to improve and increase milk and meat production [

5]. The uncontrolled crossbreeding could result in the rapid loss of the native breeds in favor of the crossbred and riverine breeds. Since these improved breeds provide higher income to farmers, they would be easily enticed to exchange and sell their native animals. While they keep crossbreds and riverine breeds for milk and meat production, the high animal extraction rates favor the native carabao breed since it can be easily sold and become a source of fast cash for the farmers.

The drastic effects of climate change could result in potential risks to animal health primarily due to changes in environmental conditions [

6]. For instance, livestock animals such as buffaloes suffer from nutrient deficiency, inadequate diet, and heat stress during extreme environments due to the non-availability of feed and poor pasture conditions [

7]. The threats to sustaining the demands of local stocks are very alarming. Therefore, the appeal to go back to increase the production of the native buffalo breed, which could easily adapt to the effects of climate change, needs pressing attention.

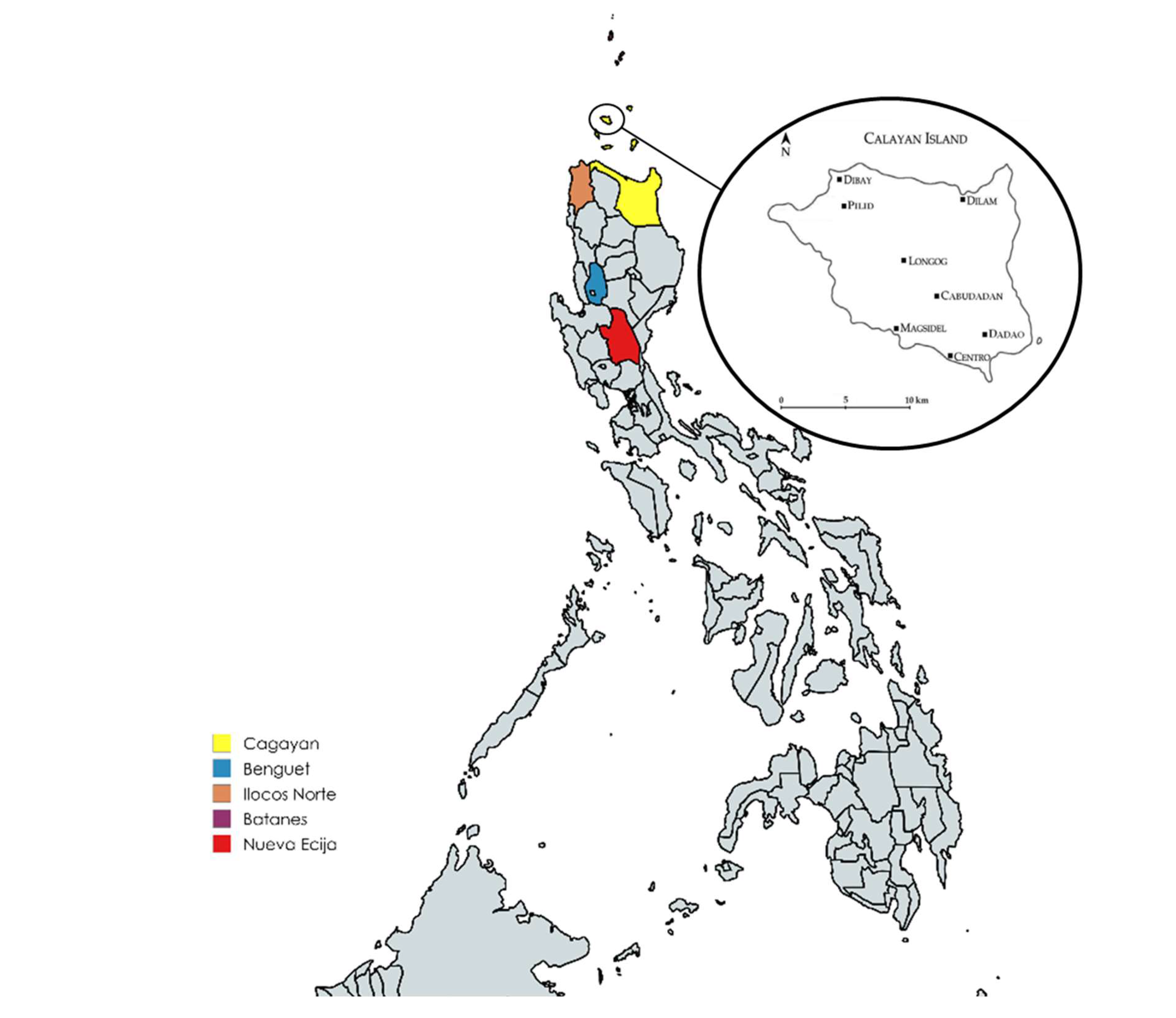

In 2022, the Municipal Agriculture Office reported a total population of 7,793 carabaos on Calayan Island. In addition, the Island for several centuries had the absence of crossbreeding or introduction of riverine buffalo semen, or shipment of live bulls. This leads the carabaos in the area to remain purebred and a strong candidate as the conservation area. Thus, the paper aimed to report on the morphometry and population structure that implied species identification, the survey on animal health profile, and concerted efforts by various stakeholders approaches for strategic conservation and management of Philippine swamp buffalo on Calayan Island.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sites and Sample Collection

This study was approved by the Department of Agriculture – Philippine Carabao Center Research Ethical Committee (BG-15002-RC) with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval of handling animals (PCC-ACUP-005-2024). In addition, all experiments followed relevant local government unit (LGU) regulations and verbal consent from the local swamp buffalo farmers. A total of 79 unrelated swamp buffaloes were identified for this study. Due to the unavailability of pedigree records, the basis of measuring the relatedness of individual animals was done through interviews with farmers to determine the absence of full-sibs and half-sibs among the animals before sampling collection. Whole blood and serum samples were obtained in the jugular vein using a sterile vacutainer needle in EDTA-treated and plain vacutainer tubes from swamp buffaloes in Calayan Island, Cagayan. Additional unrelated swamp samples from Batanes, Benguet, and Ilocos Norte were included in the morphological and molecular analysis for population comparison (

Table 1 and

Figure 1). The collected samples were stored in a cooler with coolants and transported to the laboratory for further investigation.

2.2. Morphological Characteristics and Physical Features

Morphological traits of swamp buffaloes and photo documentation for individual animals were recorded following the recommendation by Khan et al. [

9]. Phenotypic characteristics such as body coat color, forehead, foreleg, hind leg, muzzle, and iris were noted. In addition, coat pattern, horn orientation, ear shape, and orientation were also recorded. The general body morphology such as body length (BL), height at withers (HT), heart girth (HG), face length, and neck circumference was also measured, and univariate analyses were performed following the published linear model formula [

10].

2.3. DNA Isolation and PCR Optimization

The genomic DNA was extracted from the whole blood samples using the commercially available DNA extraction kit from RealiPrep™ Blood gDNA with some modifications including the additional centrifugation (14,000 rpm) for 1 min after the third washing to remove traces of cell wash solution (CWS) before the first elution and extension of 5 minutes incubation time of DNA in nuclease-free water before the elution step to obtain a high yield and good quality of DNA [

11].

Twenty-seven polymorphic microsatellite markers recommended by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) were amplified following the optimized PCR reactions and thermal cycler conditions [

3]. The PCR products with various allele sizes were visualized using 2% agarose gel. Amplified PCR products were sent to 1stBASE Sequencing Malaysia for fragment analysis.

2.4. Microsatellite Analysis

The genotyping for each locus was scored using Geneious 10.1.3 software with an internal size standard of GeneScan™ 500LIZ™. Analysis of the genetic structure and membership coefficient (Q) was carried through an alternative model-based Bayesian clustering analysis using STRUCTURE [

12] and the optimum ∆K value was visualized and calculated using the STRUCTURE Harvester program [

13].

2.5. Animal Health Screening

Seventy-nine whole blood samples were tested for

Trypanosoma evansi using a PCR-based method targeting variable surface protein (RoTat 1.2 gene) according to the previous study [

14]. Only 14 serum samples were tested for brucellosis using a serological rapid plates test (Bengatest

® Synbiotics, Country) according to the manufacturer’s protocol as the remaining samples were hemolyzed and unfit for testing.

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Characteristics and Physical Features

The morphological and physical features of swamp buffaloes in Calayan Island showed that the predominant coat color was black and gray, the muzzle and iris were black, and the stocking color of both forelegs and hindlegs was white (

Figure 2). Moreover, all swamp buffaloes on the island showed a plain coat pattern. The average morphometric values of swamp buffaloes on the island with two other locations sampled in Northern Luzon are presented in

Table 2.

3.2. Population Structure

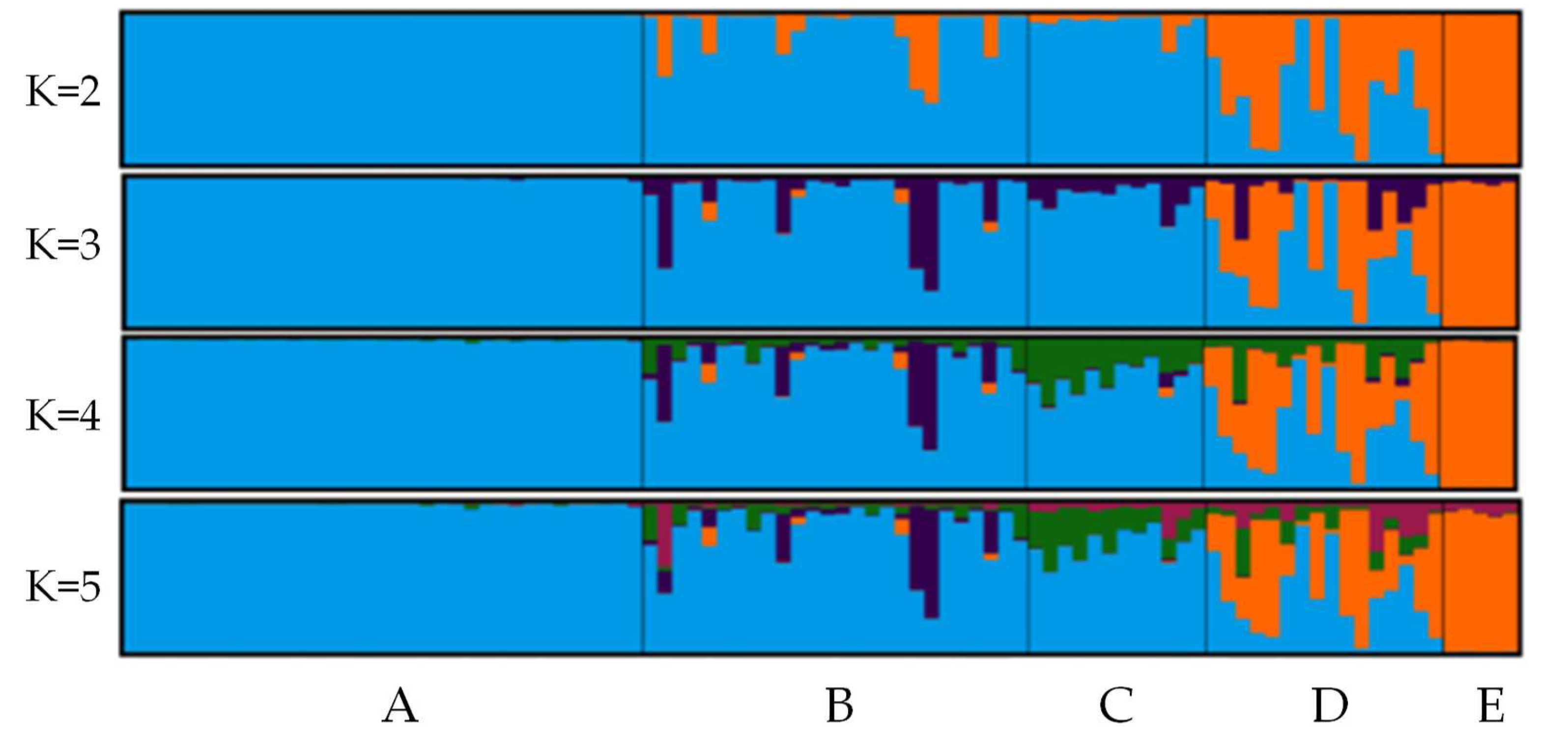

In total, 35 out of 79 animals were subjected to population structure analysis due to the elimination of full-sibs and haft-sibs among the individuals to maximize the genetic diversity within the sampled population. The STRUCTURE analysis from K=2 to K=5 unveiled the presence of population structure across swamp buffalo populations in the Northern part of the Philippines (

Figure 3). The K=2 analysis revealed the clear separation of swamp and riverine buffaloes. At optimum ∆K=3, the analysis showed the delineation of swamp buffalo in Calayan Island and other swamp buffalo populations in Northern Luzon that were included in the study. The swamp buffaloes in Calayan Island showed the highest average Q value of 0.998 as compared with Benguet (0.878), Batanes (0.852), and Ilocos (0.433). Additionally, incorporating riverine buffalo as a reference sample revealed that 43.7% of the Ilocos population (7/16) had male introgression of the riverine bloodline (

Table 3).

3.3. Animal Health Screening

A total of 79 samples were tested for Surra and 14 samples for Brucella infection. Results showed that the incidence rate for Surra and Brucella spp. infection in the newly established native carabao sanctuary in Calayan Island was 2.53% (2/79) and 50% (7/14), respectively.

4. Discussion

Physical features of swamp buffaloes in Calayan showed that the coat color was predominantly black and gray. According to a study, black-colored animals were more likely heat-intolerant which explained by their wallowing behavior [

15]. On the other hand, the gray coat color of the animals on the island could be attributed to the presence of coral limestone in the area [

16]. According to earlier data [

17,

18] the gray color was the dominant color of swamp buffaloes found in the Sylhet district, Trishal, and Companiganj sub-district of Bangladesh found to have abundant limestone deposits because of frequent earthquakes and rocky areas due to the draining of the Old Brahmaputra River. Similarly to the previous reports, swamp buffaloes on the island had whitish forelegs and hindlegs as one of the diagnostic features of swamp buffaloes [

10].

In this study, the morphology data gathered provided the baseline information showing descriptive traits of swamp buffaloes selected for conservation on the island. The average morphometric measurements of the buffaloes on Calayan Island are generally tall and hefty but have a shorter body length compared to the swamp buffaloes in Benguet and Batanes Island. The body trait morphometry specifically the height at withers, heart girth, and body length were the essential traits that are being considered for draft together with sound feet and legs and temperament. The heftiness can be extended to the neck circumference as well. The swamp buffalo head appeared longer but narrower, on average, as indicated by face length and width between horns. The horns were also generally longer but the distance between horns, measured as the distance between the tips, is wider for buffaloes from Batanes Island indicating the horns in Calayan may be more sickle-shaped or more curved. Thus, the average measurements suggest that swamp buffaloes from Calayan appear to be bigger except for body length.

The Bayesian analysis of the population structure of the Northern Luzon swamp buffalo populations indicated the presence of three clusters composed of Calayan Island (cluster 1), riverine buffaloes (cluster 2), and genetic admixture of swamp buffaloes from Benguet, Batanes, and Ilocos Norte (cluster 3). Following the published Q value threshold of 0.80 in the Saler cattle breed [

19], the increased Q value of 0.90 in all Calayan Island swamp buffaloes confirmed its distinctness from the rest of Northern Luzon populations. According to studies, animals with an arbitrary cut-off of 80% genetic membership coefficient were attributed as a pure population or specific cluster while below 80% were considered admixture population [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. The presence of the distinct sub-populations reflects the old and recent population history of Philippine carabao which is further explained by two factors. First, its isolation of population by distance. The geographic location of Calayan Island, situated about 24 miles west-south-west of Babuyan Island, Philippines which requires approximately a six-hour boat ride, could explain why this island has a distinct population structure [

10]. The island has not been connected to any land bridges in either Luzon or Taiwan since the Middle or Late Pleistocene [

24]. The physical barrier provided by great bodies of water between Calayan Island and mainland Northern Luzon caused difficulty in inter-island transportation. This factor limits the island from agricultural opportunities for livelihood improvement offered by the national and local government programs. The second factor was the initiatives and efforts toward the Carabao sanctuary implemented by its LGU. In 2017, the Calayan LGU institutionalized a local ordinance that limits the introduction of riverine buffalo lineage to preserve its native carabao population. This initiative will further the establishment of the Carabao Sanctuaries on the island. The implementation of this ordinance was supported by the Department of Agriculture - Philippine Carabao Center, together with its regional center at Cagayan State University, and facilitated the construction of the Carabao facility on the island.

It was interesting to discover that some animals tested were positive for diseases that may harm livestock production. Surra, caused by

Trypanosoma. evansii, is primarily transmitted by insect vectors such as

Tabanus spp., a biting fly [

25,

26], and blood-containing infectious trypanosomes are required for transmission from one animal to another. Surra was an exotic disease in the Philippines until the introduction of imported cavalry horses from China brought by the American soldiers during the American-Spanish war in the 19th century [

27]. The first Surra outbreak was recorded in 1901 in Manila and then spread to other provinces in Luzon Island, and resulted in high mortality in horses [

25,

27]. Moreover, brucellosis is transmitted through direct contact with the infected animal [

28,

29] and has zoonotic potential [

29,

30]. This finding is the first reported case of both diseases on Calayan Island. The island was isolated, and animals from other areas in the country were not nor seldom introduced. Possible transmission of these diseases by the movement of animals without properly examined [

26] before they travel to the island. The Calayan Island LGU furthermore has no program or disease surveillance among its livestock on the island. Therefore, the study reported the baseline information of the first incidence of swamp-positive in Surra and Brucellosis. This finding became the basis for strengthening the animal health program for swamp buffaloes on Calayan Island. The obtained knowledge also provided a pertinent document for the Surra and Brucellosis control program in swamp buffaloes.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the morphological and molecular characterizations of swamp buffaloes in Calayan Island are necessary for conservation and management. A comprehensive assessment of swamp buffaloes on Calayan Island revealed a population characterized by larger morphometric measurements and a distinct genetic profile, indicative of a purebred Philippine carabao lineage. Furthermore, the study reported the first incidence of surra and brucellosis on the island, thus an animal health control program in swamp buffaloes shall be implemented. These findings highlight that the future of the Calayan swamp buffaloes requires efforts beyond the current undertaking. It is recommended to strengthen the in-situ and expand the ex-situ conservation and health management of the local swamp buffalo on the island.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.P.V.; methodology, L.P.V., A.J.E.C., T.P.C.C., A.M.P., L.P.B., and M.M.B.; software, A.J.E.C., T.P.C.C., A.M.P.; validation, L.P.V., and E.B.F; formal analysis, A.J.E.C., T.P.C.C., A.M.P., L.P.B., and M.M.B.; investigation, A.J.E.C., T.P.C.C., A.M.P., L.P.B., and M.M.B.; resources, X.X.; data curation, A.J.E.C., T.P.C.C., A.M.P., L.P.B., and M.M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, L.P.V., M.A.V., E.B.F., and F.T.R.; writing—review and editing, L.P.V., A.J.E.C., T.P.C.C., A.M.P., L.P.B., and M.M.B.; visualization, L.P.V., A.J.E.C., T.P.C.C., A.M.P., L.P.B., and M.M.B.; supervision, L.P.V. and F.T.R.; project administration, A.J.E.C., T.P.C.C. and A.M.P.; funding acquisition, L.P.V., M.A.V., E.B.F., and F.T.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Department of Agriculture Biotechnology Program grant number DABIOTECHR-1506, and the APC was supported by the Research Development Division Department, Philippine Carabao Center National Headquarters Gene Pool of Department of Agriculture – Philippines.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Department of Agriculture – Philippine Carabao Center Research Ethical Committee (BG-15002-RC) with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval of handling animals (PCC-ACUP-005-2024).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the technical and field staff of the PCC regional centers at Cagayan State University, Don Mariano Marcos State University, and Mariano Marcos State University. We also appreciate the provincial and local government units and village-based artificial insemination technicians (VBAIT) for their assistance in collecting samples in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cruz, L. C. Trends in Buffalo Production in Asia. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 6 (SUPPL. 2), 9–24. (). [CrossRef]

- Mingala, C. N.; Belotindos, L. P.; Abes, N. S.; Cruz, L. C. Genotyping and Molecular Characterization of NRAMP1/-2 Genes as Location of Markers for Resistance and/or Susceptibility to Mycobacterium Bovis in Swamp and Riverine Type Water Buffaloes. Buffalo Bull. 2013, 32 (SPECIAL ISSUE 2).

- Escuadro, A. J. D.; Villamor, L. P. Genotyping and Assessment of Microsatellite DNA Markers for Genetic Diversity and Potential Forensic Efficacy of Philippine Carabao (Bubalus Bubalis) Swamp Buffalo. Sci. Eng. J. 2021, 14 (02 |), 235–240. Sci. Eng. J.

- Blackburn, H. D. Development of National Animal Genetic Resource Programs. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2004, 16 (1–2), 27–32. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, L. C. Transforming Swamp Buffaloes to Producers of Milk and Meat through Crossbreeding and Backcrossing. Wartazoa 2010, 19 (3), 103–116.

- Lacetera, N. Impact of Climate Change on Animal Health and Welfare. Anim. Front. 2019, 9 (1), 26–31. [CrossRef]

- Chaidanya, K.; Shaji, S.; Niyas, P. A. A.; Sejian, V. Journal of Veterinary Science & Medical Diagnosis Climate Change and Livestock Nutrient Availability : Impact and Mitigation. 2015.

- Española, C. P.; Oliveros, C. H. Conservation of an Island Endemic: Calayan Rail Gallirallus Calayanensis. Final Report; 2005.

- Khan, M.; Rahim, I.; Rueff, H.; Jalali, S.; Saleem, M.; Maselli, D.; Muhammad, S.; Wiesmann, U. Morphological Characterization of the Azikheli Buffalo in Pakistan. Anim. Genet. Resour. génétiques Anim. genéticos Anim. 2013, 52, 65–70. [CrossRef]

- Paraguas, A. M.; Cailipan, C.; Flores, E. B.; Villamor, L. P. Morphology and Phylogeny of Swamp Buffaloes (Bubalus Bubalis) in Calayan Island, Cagayan. Philipp J Vet Anim Sci 2018, 44 (1), 59–67.

- Villamor, L. P.; Takahashi, Y.; Nomura, K.; Amano, T. Genetic Diversity of Philippine Carabao (Bubalus Bubalis) Using Mitochondrial Dna d-Loop Variation: Implications to Conservation and Management. Philipp. J. Sci. 2021, 150 (3), 837–846. [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, J. K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of Population Structure Using Multilocus Genotype Data. Genetics 2000, 155 (2), 945–959. [CrossRef]

- Earl, D. A.; vonHoldt, B. M. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: A Website and Program for Visualizing STRUCTURE Output and Implementing the Evanno Method. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2012, 4 (2), 359–361. [CrossRef]

- Barghash, S. M.; Darwish, A. M.; Abou-ElNaga, T. R. Molecular Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis of Trypanosoma Evansi from Local and Imported Camels in Egypt. J. Phylogenetics Evol. Biol. 2016, 4 (3). [CrossRef]

- Marai, I. F. M.; Haeeb, A. A. M. Buffalo’s Biological Functions as Affected by Heat Stress - A Review. Livest. Sci. 2010, 127 (2–3), 89–109. [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.; Oliveros, C. H.; Española, C.; Broad, G.; Gonzalez, J. C. T. A New Species of Gallirallus from Calayan Island, Philippines. Forktail 2004, 20 (January), 1–7.

- Siddiquee, N.; Faruque, M.; Islam, F.; Mijan, M.; Habib, M. Morphometric Measurements, Productive and Reproductive Performance of Buffalo in Trishal and Companiganj Sub-Districts of Bangladesh. Int. J. BioRes 2010, 1 (6), 15–21.

- Rahman, M.; Islam, R.; Hossain, M. K.; Lucky, N. S.; Zahan, N. Full Length Research Paper Phenotypic Characterization of Indigenous Buffalo at Sylhet District. Int. J. Sci. Res. Agric. Sci. 2015, 2 (1), 1–6.

- Gamarra, D.; Lopez-Oceja, A.; De Pancorbo, M. M. Genetic Characterization and Founder Effect Analysis of Recently Introduced Salers Cattle Breed Population. Animal 2017, 11 (1), 24–32. [CrossRef]

- Winkler, L. R.; Bonman, J. M.; Chao, S.; Yimer, B. A.; Bockelman, H.; Klos, K. E. Population Structure and Genotype-Phenotype Associations in a Collection of Oat Landraces and Historic Cultivars. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Goodman, M.; Muse, S.; Smith, J. S.; Buckler, E.; Doebley, J. Genetic Structure and Diversity among Maize Inbred Lines as Inferred from DNA Microsatellites. Genetics 2003, 165 (4), 2117–2128. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F. M.; Zhang, N. N.; Liu, X. J.; Yang, Z. J.; Jia, H. Y.; Xu, D. P. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure Analysis of Dalbergia Odorifera Germplasm and Development of a Core Collection Using Microsatellite Markers. Genes (Basel). 2019, 10 (4). [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chappell, M.; Zhang, D. Assessing Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Kalmia Latifolia L. in the Eastern United States: An Essential Step towards Breeding for Adaptability to Southeastern Environmental Conditions. Sustain. 2020, 12 (19), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Heaney, L. R. Zoogeographic Evidence for Middle and Late Pleistocene Land Bridges to the Philippine Islands. Mod. Quat. Res. Southeast Asia. Vol. 9 1985, No. 9, 127–143.

- Dargantes, A. P. Epidemiology, Control and Potential Insect Vectors of Trypanosoma Evansi (Surra) in Village Livestock in Southern Philippines, Doctor of Philosophy (Veterinary Epidemiology and Disease Ecology) Dissertation, Murdoch University, Perth, Australia, August, 2010.

- Desquesnes, M.; Dargantes, A.; Lai, D. H.; Lun, Z. R.; Holzmuller, P.; Jittapalapong, S. Trypanosoma Evansi and Surra: A Review and Perspectives on Transmission, Epidemiology and Control, Impact, and Zoonotic Aspects. Biomed Res. Int. 2013, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Manuel, M. F. Sporadic Outbreaks of Surra in the Philippines and Its Economic Impact. J. Protozool. Res. 1998, No. 8, 131–138.

- Perumal, P.; Kiran Kumar, T.; Srivastava, S. K. Infectious Causes of Infertility in Buffalo Bull (Bubalus Bubalis). Buffalo Bull. 2013, 32 (2), 71–82.

- Qureshi, K. A.; Parvez, A.; Fahmy, N. A.; Abdel Hady, B. H.; Kumar, S.; Ganguly, A.; Atiya, A.; Elhassan, G. O.; Alfadly, S. O.; Parkkila, S.; Aspatwar, A. Brucellosis: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Treatment–a Comprehensive Review. Ann. Med. 2023, 55 (2). [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, A.; Li, Z.; Radwanska, M.; Magez, S. Recent Progress in the Detection of Surra, a Neglected Disease Caused by Trypanosoma Evansi with a One Health Impact in Large Parts of the Tropic and Sub-Tropic World. Microorganisms 2024, 12 (1). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).