Submitted:

01 October 2024

Posted:

02 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Newcastle Disease Virus (NDV) and Genotypes

2.1. NDV Genotypes: A Global Update

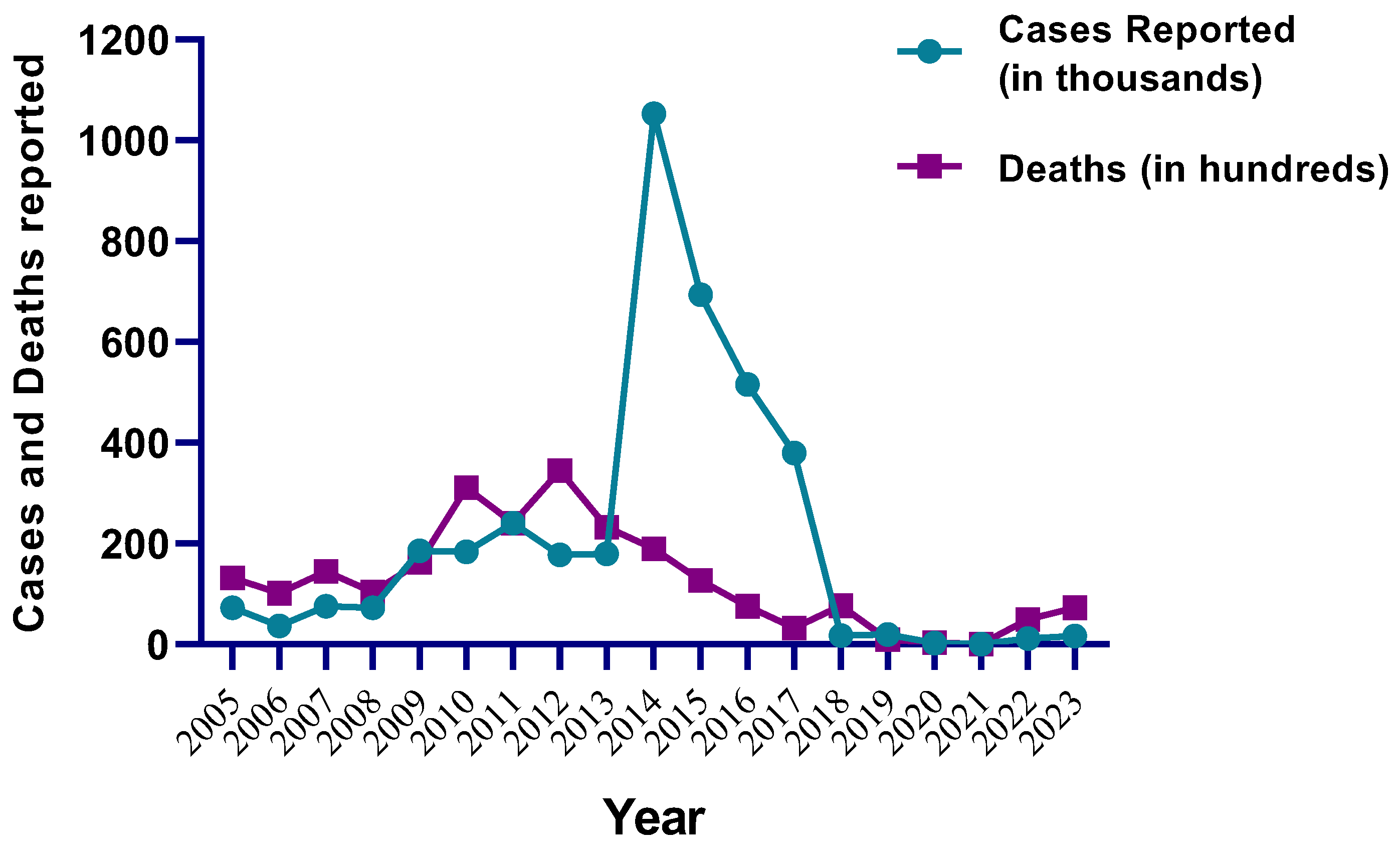

| Region | Total cases (in lakhs) |

Deaths (in lakhs) |

% Deaths | Genotype | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | 2135.32 | 828.61 | 38.80 | VIId | [40] |

| VII | [41] | ||||

| VIIi | [42] | ||||

| VIII | [43] | ||||

| XIII | [44] | ||||

| VII.1.1 | [45] | ||||

| XIII.2.1 | [46] | ||||

| VII.2 | [47] | ||||

| XIII.2 | [48] | ||||

| Africa | 411.33 | 203.33 | 49.43 | NT | - |

| America | 46.40 |

10.35 |

22.31 |

VII VIIa, VIId |

[49,50] |

| Europe | 13.01 | 5.83 | 44.81 | VIIa | [51] |

| VII.2 |

[52,53] | ||||

| Oceania | 0.00017 | 0.00017 | 100.00 | NT | No genotypes reported |

2.2. NDV Genotypes: An Indian Update

| Year | Region | Species | Genotype | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006-2012 | Central India | Chicken | XIIIb | [62] |

| 2016-2020 | North-Eastern India | Chicken | XXII.1, XXII.2 & XIII | [69] |

| 2010-2012 | Southern India | Emu | XIII | [74] |

| 2011-2013 | Northern India | Pea fowl | VIIi & XIII | [75] |

| 2014 | Southern and Northern India | Chicken | XIII | [76] |

| 2015 | North-Eastern India | Chicken | XIII & XIIIc | [77] |

| 2015-2016 | Northern India | Chicken | XIIIa | [60] |

| 2015-2016 | Southern India | Chicken | XIII & XIIIe | [68,78] |

| 2019 | Eastern India | Commercial and backyard poultry | XIII | [79] |

| 2023 | Northern India | Chicken | VII.2 | [61] |

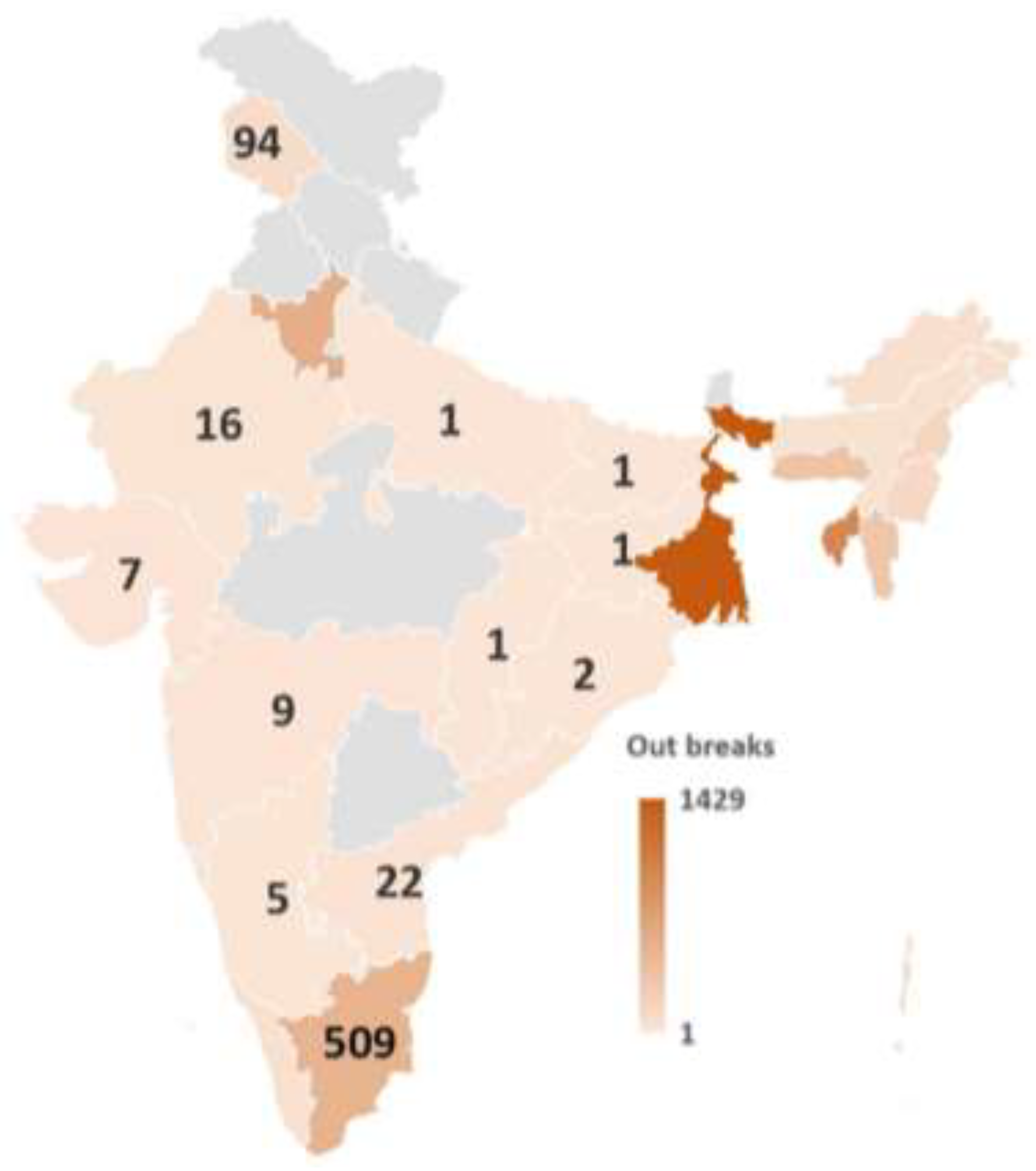

| Region | Cases | Deaths | % Deaths | Genotype | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andhra Pradesh | 2941 | 1581 | 53.76 | XIII | [65] |

| Andaman and Nicobar | 26843 | 2437 | 9.08 | ||

| Arunachal Pradesh | 1889 | 762 | 40.34 | ||

| Assam | 20496 | 5996 | 29.25 | XIII & XIIIc | [77] |

| Bihar | 35 | 15 | 42.86 | ||

| Chhattisgarh | 4869 | 1213 | 24.91 | ||

| Daman & Diu | 83 | 4 | 48.19 | ||

| Goa | 24 | 4 | 16.67 | ||

| Gujarat | 3773 | 442 | 11.71 | XIII | [57,80] |

| Haryana | 2624586 | 59284 | 2.26 | VIIi |

[64,75] |

| XIII | [65] | ||||

| Jammu & Kashmir | 30773 | 4642 | 15.08 | ||

| Jharkhand | 32 | 0 | 0.00 | ||

| Karnataka | 5720 | 4709 | 82.32 | ||

| Kerala | 55936 | 3701 | 6.62 | ||

| Lakshadweep | 26473 | 11735 | 44.33 | ||

| Maharashtra | 13496 | 12768 | 94.61 | XIIIb | [62] |

| Manipur | 73240 | 3516 | 4.80 | ||

| Meghalaya | 23847 | 7801 | 32.71 | ||

| Mizoram | 26694 | 9115 | 34.30 | ||

| Nagaland | 25934 | 5439 | 20.97 | ||

| Orissa | 205 | 25 | 12.20 | ||

| Pondicherry | 9552 | 2932 | 30.70 | ||

| Rajasthan | 13140 | 3130 | 23.82 | ||

| Tamil Nadu | 684845 | 17540 | 2.56 | XIII &XIIIe | [65,68,78] |

| Tripura | 144320 | 34160 | 23.67 | ||

| Uttar Pradesh | 12 | 9 | 75.00 | XIIIa | [60] |

| XIII, VIIi | [64] | ||||

| West Bengal | 95642 | 40390 | 42.23 | XIII | [65] |

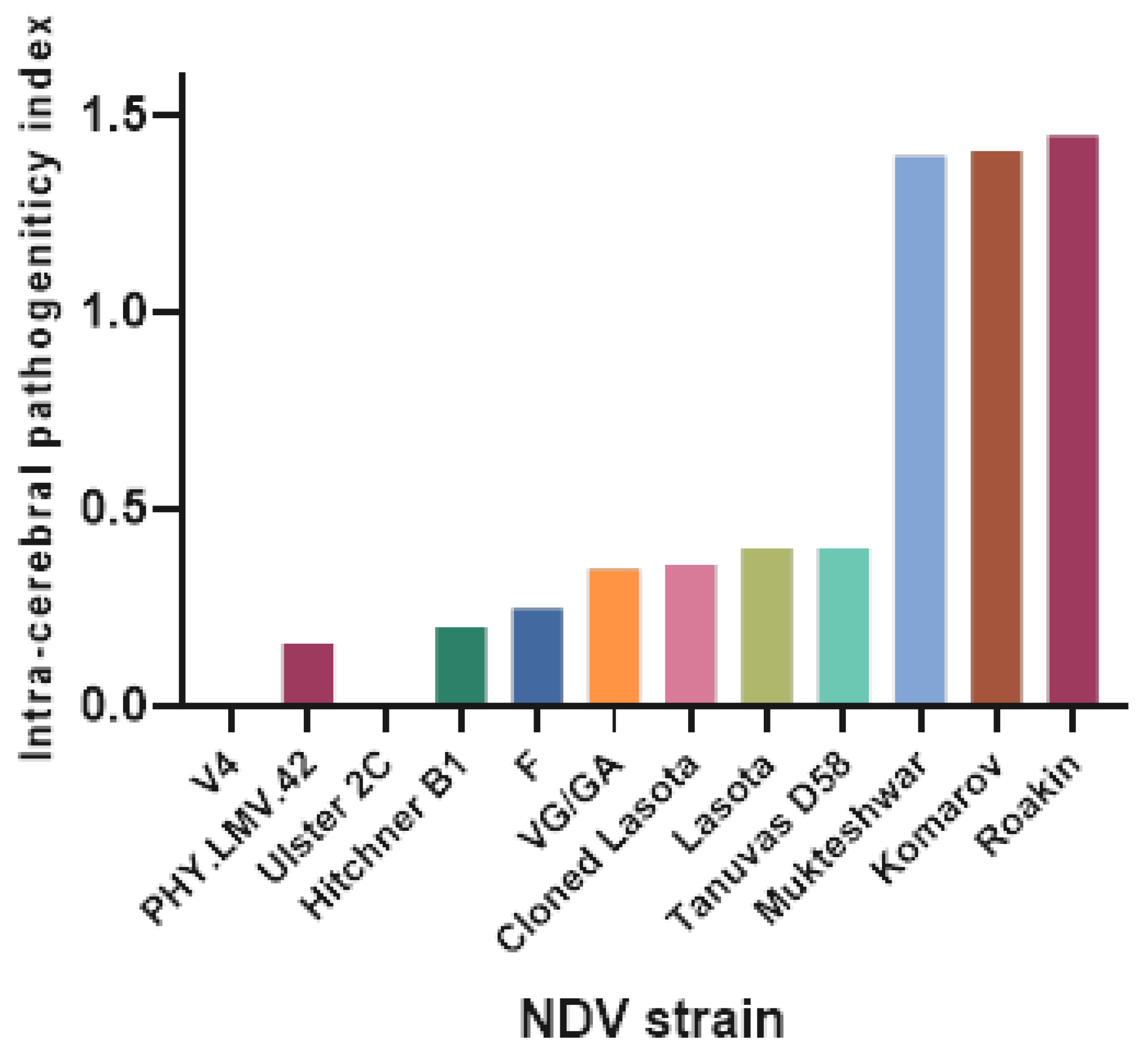

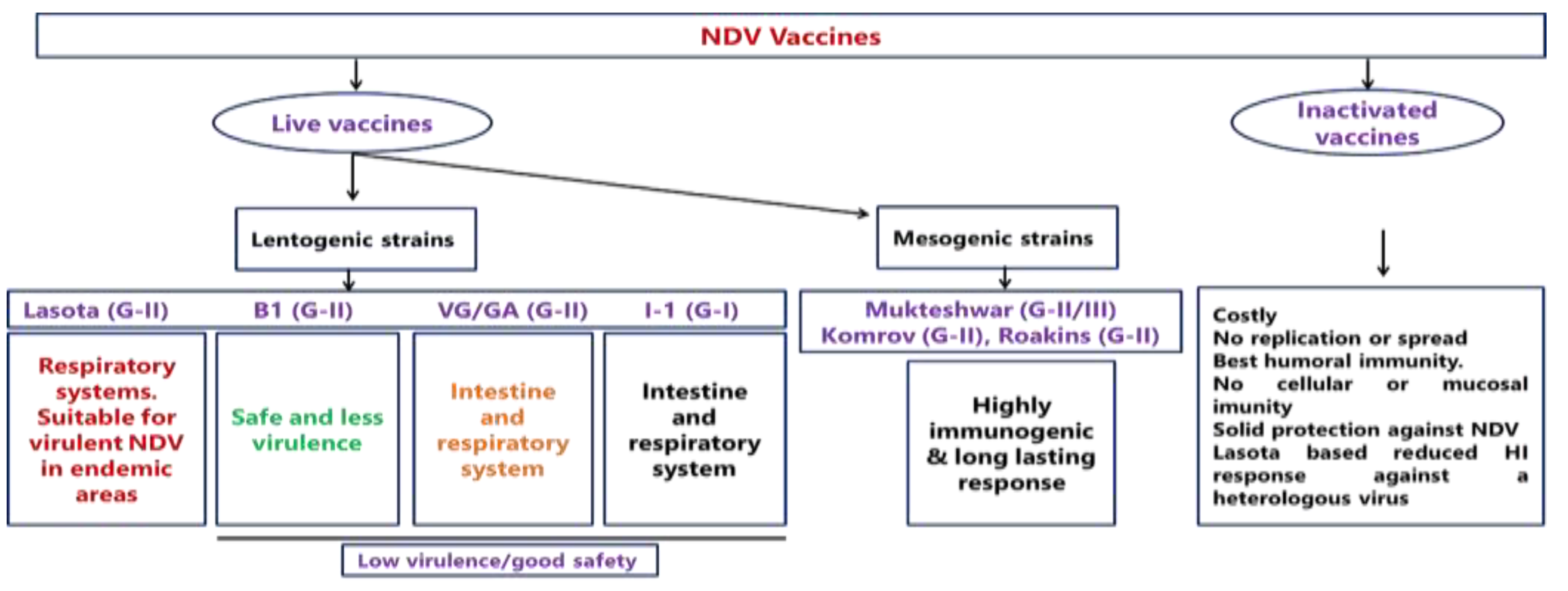

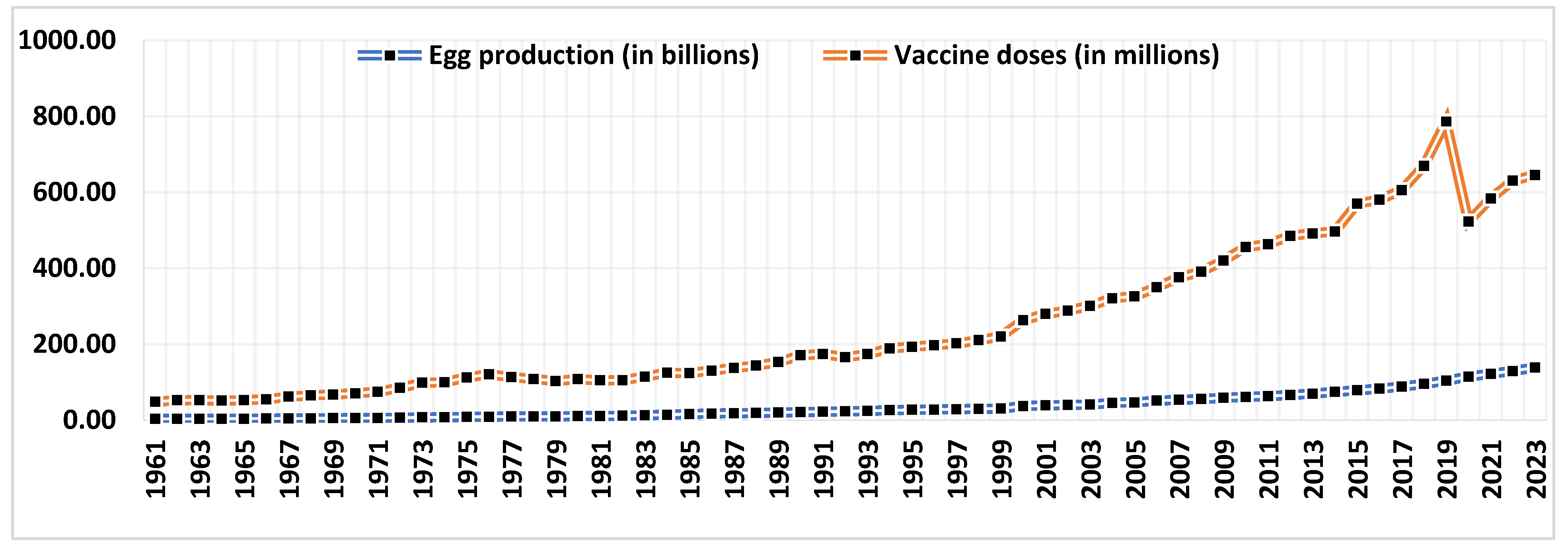

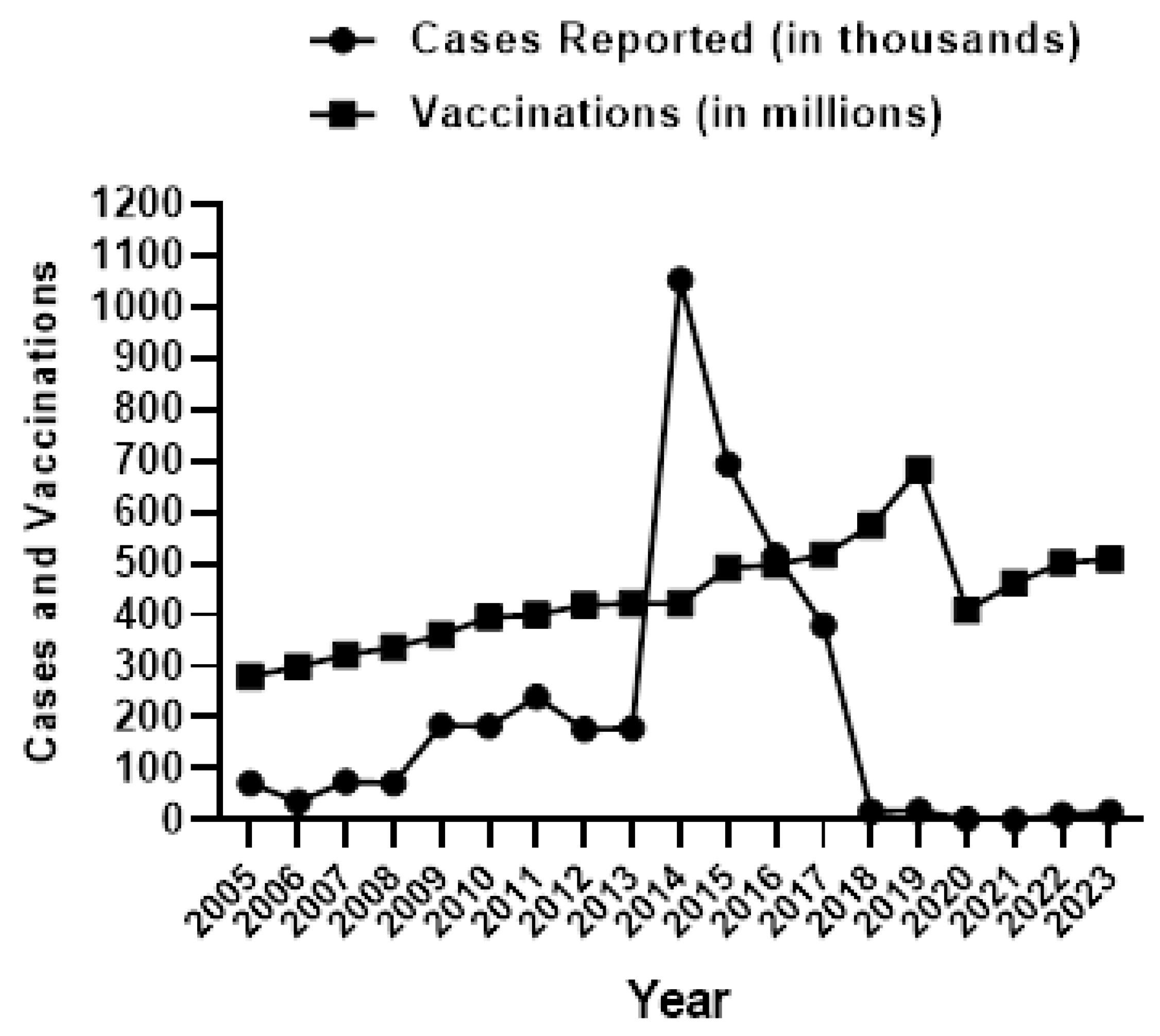

3. Newcastle Disease: Vaccines and Vaccination

4. Does Heterologous Genotype-Based Vaccines Offer Better Protection than Homologous?

5. Strategies for Updating Vaccine Genotype to Mitigate Dominant Field Virus Strains

5.1. Classical Inactivation of Field Viruses

5.2. Reverse Genetics Approach

5.3. CRISPR-Based Gene Editing Vaccines

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/poultry-production tonnes, Accessed on 20.09.2024.

- Statista. Leading egg production countries. https://www.statista.com/statistics/263971/top-10-countries-worldwide-in-egg-production, Statista, 2024.

- Kolluri, G.; Tyagi, J.S.; Sasidhar, P.V.K. Research Note: Indian poultry industry vis-à-vis coronavirus disease 2019: a situation analysis report. Poult. Sci. 2020, 100, 100828–100828. [CrossRef]

- DAHD. Government of India, Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying, Department of Animal Husbandry and Dairying, Krishi Bhavan, New Delhi. 2023.

- Statista. India: poultry meat production volume. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1358419/india-economic-contribution-of-poultry-meat, Statista, 2023.

- Kolluri, G. and Tiwari, A.K. Newcastle disease virus in chickens: Time to revisit the vaccine updation in India? In International symposium on animal viruses, vaccines and immunity (AVVI 2024), Orissa, India, 9-11, February.

- Charkhkar, S.; Bashizade, M.; Sotoudehnejad, M.; Ghodrati, M.; Bulbuli, F.; Akbarein, H. The evaluation and importance of Newcastle disease’s economic loss in commercial layer poultry. 2024, 2, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Cattoli, G.; Susta, L.; Terregino, C.; Brown, C. Newcastle disease: a review of field recognition and current methods of laboratory detection. J. vet. Diagn. Invest. 2011, 23, 637-56.

- Khatun, M.; Islam, I.; Ershaduzzaman, M.; Islam, H.; Yasmin, S.; Hossen, A.; Hasan, M. Economic impact of newcastle disease on village chickens-a case of Bangladesh. Asian. Inst. Res. J. Econ. Bus. 2018, 1, 358-67.

- Alexander, D. J. Newcastle disease. Br. Poult. Sci. 2001, 42, 5–22.

- Aldous, E.W.; Mynn, J.K.; Banks, J.; Alexander, D.J. A molecular epidemiological study of avian paramyxovirus type 1 (Newcastle disease virus) isolates by phylogenetic analysis of a partial nucleotide sequence of the fusion protein gene. Avian Pathol. 2003, 32, 237–255. [CrossRef]

- WOAH-WAHIS. World Organization for Animal Health Information System Interface (WAHIS). Available online: http://wahis.woah.org/#/home (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- World Organization for Animal Health. Infection with Newcastle disease, Chapter 10.9, Article 10.9.1. Terrestrial Code Online Access - WOAH - World Organisation for Animal Health. 2024, Accessed on September 10, 2023.

- World Bank. World livestock disease atlas: a quantitative analysis of global animal health data (2006-2009). Washington, DC: World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2011/11/15812714/worldlivestock-disease-atlas-quantitative-analysis-global-animal-health-data-2006-2009, 2011.

- Glickman, R.L.; Syddall, R.J.; Iorio, R.M.; Sheehan, J.P.; A Bratt, M. Quantitative basic residue requirements in the cleavage-activation site of the fusion glycoprotein as a determinant of virulence for Newcastle disease virus. J. Virol. 1988, 62, 354–356. [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.M.; King, D.J.; Curry, P.E.; Suarez, D.L.; Stallknecht, D.E.; Slemons, R.D.; Pedersen, J.C.; Senne, D.A.; Winker, K.; Afonso, C.L. Phylogenetic Diversity among Low-Virulence Newcastle Disease Viruses from Waterfowl and Shorebirds and Comparison of Genotype Distributions to Those of Poultry-Origin Isolates. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 12641–12653. [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.M.; King, D.J.; Suarez, D.L.; Wong, C.W.; Afonso, C.L. Characterization of class I Newcastle disease virus isolates from HongKong live bird markets and detection using real-time reverse transcription-PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007b, 45, 1310–1314.

- Czeglédi, A.; Ujvári, D.; Somogyi, E.; Wehmann, E.; Werner, O.; Lomniczi, B. Third genome size category of avian paramyxovirus serotype 1 (Newcastle disease virus) and evolutionary implications. Virus Res. 2006, 120, 36–48. [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.J.; Decanini, E.L.; Afonso, C.L. Newcastle disease: Evolution of genotypes and the related diagnostic challenges. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2010, 10, 26–35. [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, K.M.; Abolnik, C.; Afonso, C.L.; Albina, E.; Bahl, J.; Berg, M.; Briand, F.-X.; Brown, I.H.; Choi, K.-S.; Chvala, I.; et al. Updated unified phylogenetic classification system and revised nomenclature for Newcastle disease virus. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019, 74, 103917. [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Xia, J.; Li, S.; Shen, Y.; Chen, W.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wen, Y.; Wu, R.; Yan, Q.; et al. Evolutionary dynamics and transmission patterns of Newcastle disease virus in China through Bayesian phylogeographical analysis. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0239809. [CrossRef]

- Amoia, C.F.A.N.; Nnadi, P.A.; Ezema, C.; Couacy-Hymann, E. Epidemiology of Newcastle disease in Africa with emphasis on Côte d'Ivoire: A review. Veter- World 2021, 14, 1727–1740. [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.J.; Kovesdy, L. STUDIES ON THE EPIZOOTIOLOGY OF INFECTION WITH AVIRULENT NEWCASTLE DISEASE VIRUS IN BROILER CHICKEN FLOCKS IN VICTORIA. Aust. Veter- J. 1974, 50, 155–158. [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.; Shabbir, M.Z. Suppl-2, M3: Adaptation of Newcastle disease virus (NDV) in feral birds and their Potential Role in Interspecies Transmission. The Open Virol. J. 2018, 12, 52.

- Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, W.; Zheng, D.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ge, S.; Lv, Y.; Zuo, Y.; et al. Genomic Characterizations of Six Pigeon Paramyxovirus Type 1 Viruses Isolated from Live Bird Markets in China during 2011 to 2013. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0124261–e0124261. [CrossRef]

- Bello, M.B.; Yusoff, K.; Ideris, A.; Hair-Bejo, M.; Peeters, B.P.H.; Omar, A.R. Diagnostic and Vaccination Approaches for Newcastle Disease Virus in Poultry: The Current and Emerging Perspectives. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.W.; Heron, B.R.; Mixson, M.A. Exotic Newcastle Disease Eradication Program in the United States. Avian Dis. 1973, 17, 486–503. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, G.L.; McCann, M.K. The role of indigenous wild, semidomestic, and exotic birds in the epizootiology of velogenic viscerotropic Newcastle disease in southern California, 1972-1973.. 1975, 167, 610–4.

- Herczeg, J.; Wehmann, E.; Bragg, R.R.; Dias, P.M.T.; Hadjiev, G.; Werner, O.; Lomniczi, B. Two novel genetic groups (VIIb and VIII) responsible for recent Newcastle disease outbreaks in Southern Africa, one (VIIb) of which reached Southern Europe. Arch. Virol. 1999, 144, 2087–2099. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.-J.; Cho, S.-H.; Ahn, Y.-J.; Seo, S.-H.; Choi, K.-S.; Kim, S.-J. Molecular epidemiology of Newcastle disease in Republic of Korea. Veter- Microbiol. 2003, 95, 39–48. [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.W.; Ideris, A.; Omar, A.R.; Yusoff, K.; Hair-Bejo, M. Sequence and phylogenetic analysis of Newcastle disease virus genotypes isolated in Malaysia between 2004 and 2005. Arch. Virol. 2009, 155, 63–70. [CrossRef]

- Goudarzi, H.; VAN Borm, S.; Bashashati, M.; Sabouri, F.; Abdoshah, M.; Nouri, A.; Banani, M.; Ebrahimi, M.M.; Molouki, A. Characterization and full genome sequencing of a velogenic Newcastle disease virus (NDV) strain Ck/IR/Beh/2011 belonging to subgenotype VII(L). Acta Virol. 2019, 63, 217–222. [CrossRef]

- Absalón, A.E.; Cortés-Espinosa, D.V.; Lucio, E.; Miller, P.J.; Afonso, C.L. Epidemiology, control, and prevention of Newcastle disease in endemic regions: Latin America. Trop. Anim. Heal. Prod. 2019, 51, 1033–1048. [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, P.D. Virulent Newcastle disease virus in Australia: in through the ‘back door’. Aust. vet. J. 2000, 78, 331-333.

- Murray, G. Australia officially free of Newcastle disease. Aust. Vet. J. 2003, 81, 460-462.

- Yu, L.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Chang, L.; Kwang, J. Characterization of Newly Emerging Newcastle Disease Virus Isolates from the People's Republic of China and Taiwan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 3512–3519. [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.J.; Haddas, R.; Simanov, L.; Lublin, A.; Rehmani, S.F.; Wajid, A.; Bibi, T.; Khan, T.A.; Yaqub, T.; Setiyaningsih, S.; et al. Identification of new sub-genotypes of virulent Newcastle disease virus with potential panzootic features. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015, 29, 216–229. [CrossRef]

- Munir, M.T.; Chowdhury, M.R; Ahmed, Z. Emergence of new sub-genotypes of Newcastle disease virus in Pakistan. J Avian Res, 2016, 2, 1-7.

- Ghalyanchilangeroudi, A.; Hosseini, H.; Jabbarifakhr, M.; Mehrabadi, M.H.F.; Najafi, H.; Ghafouri, S.A.; Mousavi, F.S.; Ziafati, Z.; Modiri, A. Emergence of a virulent genotype VIIi of Newcastle disease virus in Iran. Avian Pathol. 2018, 47, 509–519. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-Y.; Shao, M.-Y.; Yu, X.-H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, G.-Z. Molecular characterization of chicken-derived genotype VIId Newcastle disease virus isolates in China during 2005–2012 reveals a new length in hemagglutinin–neuraminidase. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014, 21, 359–366. [CrossRef]

- Ewies, S.S.; Ali, A.; Tamam, S.M.; Madbouly, H.M. Molecular characterization of Newcastle disease virus (genotype VII) from broiler chickens in Egypt. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2017, 6, 232–237. [CrossRef]

- Wajid, A.; Dimitrov, K.M.; Wasim, M.; Rehmani, S.F.; Basharat, A.; Bibi, T.; Arif, S.; Yaqub, T.; Tayyab, M.; Ababneh, M.; et al. Repeated isolation of virulent Newcastle disease viruses in poultry and captive non-poultry avian species in Pakistan from 2011 to 2016. Prev. Veter- Med. 2017, 142, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Sabouri, F.; Marandi, M.V.; Bashashati, M. Characterization of a novel VIIl sub-genotype of Newcastle disease virus circulating in Iran. Avian Pathol. 2018, 47, 90–99. [CrossRef]

- Kabiraj, C.K.; Mumu, T.T.; Chowdhury, E.H.; Islam, M.R.; Nooruzzaman, M. Sequential Pathology of a Genotype XIII Newcastle Disease Virus from Bangladesh in Chickens on Experimental Infection. Pathogens 2020, 9, 539. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.M.; Amer, S.A.; Abdel-Alim, G.A.; Elbayoumi, K.M.; Kutkat, M.A.; and Amer, M.M. Molecular characterization of recently classified Newcastle disease virus genotype VII. 1.1 isolated from Egypt. Int. J. Vet. Sci. 2022, 11, 295-301.

- Hejazi, Z.; Tabatabaeizadeh, S.; Toroghi, R.; Farzin, H.; Saffarian, P. First detection and characterisation of sub-genotype XIII.2.1 Newcastle disease virus isolated from backyard chickens in Iran. Veter- Med. Sci. 2022, 8, 2521–2531. [CrossRef]

- Kariithi, H.M.; Volkening, J.D.; Chiwanga, G.H.; Goraichuk, I.V.; Olivier, T.L.; Msoffe, P.L.M.; Suarez, D.L. Virulent Newcastle disease virus genotypes V.3, VII.2, and XIII.1.1 and their coinfections with infectious bronchitis viruses and other avian pathogens in backyard chickens in Tanzania. Front. Veter- Sci. 2023, 10, 1272402. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, I.; Subarna, J.F.; Kabiraj, C.K.; Begum, J.A.; Parvin, R.; Martins, M.; Diel, D.G.; Chowdhury, E.H.; Islam, M.R.; Nooruzzaman, M. A Booster with a Genotype-Matched Inactivated Newcastle Disease Virus (NDV) Vaccine Candidate Provides Better Protection against a Virulent Genotype XIII.2 Virus. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1005. [CrossRef]

- Perozo, F.; Marcano, R.; Afonso, C.L. Biological and Phylogenetic Characterization of a Genotype VII Newcastle Disease Virus from Venezuela: Efficacy of Field Vaccination. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 1204–1208. [CrossRef]

- Diel, D.G.; Susta, L.; Garcia, S.C.; Killian, M.L.; Brown, C.C.; Miller, P.J.; Afonso, C.L. Complete Genome and Clinicopathological Characterization of a Virulent Newcastle Disease Virus Isolate from South America. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 378–387. [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C.; Löndt, B.; Dimitrov, K.M.; Lewis, N.; van Boheemen, S.; Fouchier, R.; Coven, F.; Goujgoulova, G.; Haddas, R.; Brown, I. An Epizootiological Report of the Re-emergence and Spread of a Lineage of Virulent Newcastle Disease Virus into Eastern Europe. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2015, 64, 1001–1007. [CrossRef]

- Steensels, M.; Van Borm, S.; Mertens, I.; Houdart, P.; Rauw, F.; Roupie, V.; Snoeck, C.J.; Bourg, M.; Losch, S.; Beerens, N.; et al. Molecular and virological characterization of the first poultry outbreaks of Genotype VII.2 velogenic avian orthoavulavirus type 1 (NDV) in North-West Europe, BeNeLux, 2018. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 2147–2160. [CrossRef]

- Turan, N.; Ozsemir, C.; Yilmaz, A.; Cizmecigil, U.Y.; Aydin, O.; Bamac, O.E.; Gurel, A.; Kutukcu, A.; Ozsemir, K.; Tali, H.E.; et al. Identification of Newcastle disease virus subgenotype VII.2 in wild birds in Turkey. BMC Veter- Res. 2020, 16, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Edwards J. A New Fowl Disease. March 31st, Mukteshwar, Vet. Res. 1928, 14–15.

- Kylasamaier, K. A. Study on Madras Fowl Pest. 1931.

- Ravishankar, C.; Ravindran, R.; John, A.A.; Divakar, N.; Chandy, G.; Joshi, V.; Chaudhary, D.; Bansal, N.; Singh, R.; Sahoo, N.; et al. Author response for "Detection of Newcastle disease virus and assessment of associated relative risk in backyard and commercial poultry in Kerala, India". 2021. [CrossRef]

- Khorajiya, J.; Joshi, B.; Mathakiya, R.; Prajapati, K.; Sipai, S. Economic Impact of Genotype- Xiii Newcastle Disease Virus Infection on Commercial Vaccinated Layer Farms in India. Int. J. Livest. Res. 2018, 8, 280. [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Kumar, S. Evidence of independent evolution of genotype XIII Newcastle disease viruses in India. Arch. Virol. 2016, 162, 997–1007. [CrossRef]

- Tirumurugaan, K.G.; Kapgate, S.; Vinupriya, M.K.; Vijayarani, K.; Kumanan, K.; Elankumaran, S. Genotypic and Pathotypic Characterization of Newcastle Disease Viruses from India. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e28414. [CrossRef]

- Mariappan, A.K.; Munusamy, P.; Kumar, D.; Latheef, S.K.; Singh, S.D.; Singh, R.; Dhama, K. Pathological and molecular investigation of velogenic viscerotropic Newcastle disease outbreak in a vaccinated chicken flocks. VirusDisease 2018, 29, 180–191. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, N.; Patil, K.; Shah, N.; Rathod, P.; Chavda, N.; Ruparel, F.; Chhikara, M.K. Deciphering whole genome sequence of a Newcastle disease virus genotype VII. 2 isolate from a commercial poultry farm in India. Gene Rep. 2024, 34, 101884.

- Morla, S.; Shah, M.; Kaore, M.; Kurkure, N.V.; Kumar, S. Molecular characterization of genotype XIIIb Newcastle disease virus from central India during 2006–2012: Evidence of its panzootic potential. Microb. Pathog. 2016, 99, 83–86. [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Venugopalan, A.; Koteeswaran, A. Antigenetically unusual Newcastle disease virus from racing pigeons in India.. Trop. Anim. Heal. Prod. 2000, 32, 183–188. [CrossRef]

- Desingu, P.A.; Singh, S.D.; Dhama, K.; Karthik, K.; Kumar, O.R.V.; Malik, Y.S. Phylogenetic analysis of Newcastle disease virus isolates occurring in India during 1989–2013. VirusDisease 2016, 27, 203–206. [CrossRef]

- Jakhesara, S.J.; Prasad, V.V.S.P.; Pal, J.K.; Jhala, M.K.; Prajapati, K.S.; Joshi, C.G. Pathotypic and Sequence Characterization of Newcastle Disease Viruses from Vaccinated Chickens Reveals Circulation of Genotype II, IV and XIII and in India. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2014, 63, 523–539. [CrossRef]

- Khulape, S.A.; Gaikwad, S.S.; Chellappa, M.M.; Mishra, B.P.; Dey, S. Complete Genome Sequence of a Newcastle Disease Virus Isolated from Wild Peacock ( Pavo cristatus ) in India. Genome Announc. 2014, 2, e00495-14. [CrossRef]

- Gowthaman, V.; Ganesan, V.; Murthy, T.R.G.K.; Nair, S.; Yegavinti, N.; Saraswathy, P.V.; Kumar, G.S.; Udhayavel, S.; Senthilvel, K.; Subbiah, M. Molecular phylogenetics of Newcastle disease viruses isolated from vaccinated flocks during outbreaks in Southern India reveals circulation of a novel sub-genotype. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 66, 363–372. [CrossRef]

- Gowthaman, V.; Singh, S.D.; Dhama, K.; Ramakrishnan, M.A.; Malik, Y.P.S.; Murthy, T.R.G.K.; Chitra, R.; Munir, M. Co-infection of Newcastle disease virus genotype XIII with low pathogenic avian influenza exacerbates clinical outcome of Newcastle disease in vaccinated layer poultry flocks. VirusDisease 2019, 30, 441–452. [CrossRef]

- Rajkhowa, T.K.; Zodinpuii, D.; Bhutia, L.D.; Islam, S.J.; Gogoi, A.; Hauhnar, L.; Kiran, J.; Choudhary, O.P. Emergence of a novel genotype of class II New Castle Disease virus in North Eastern States of India. Gene 2023, 864, 147315. [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, R.; Gul, I.; Wani, S.; Kashoo, Z.; Gul, N.; Islam, S.U.; Ahmad, W.; Wali, A.; Qureshi, S. Molecular Characterisation and Dynamics of the Fusion Protein of an Emerging Genotype VIIi of Newcastle Disease Virus. Agric. Res. 2024, 1–12. [CrossRef]

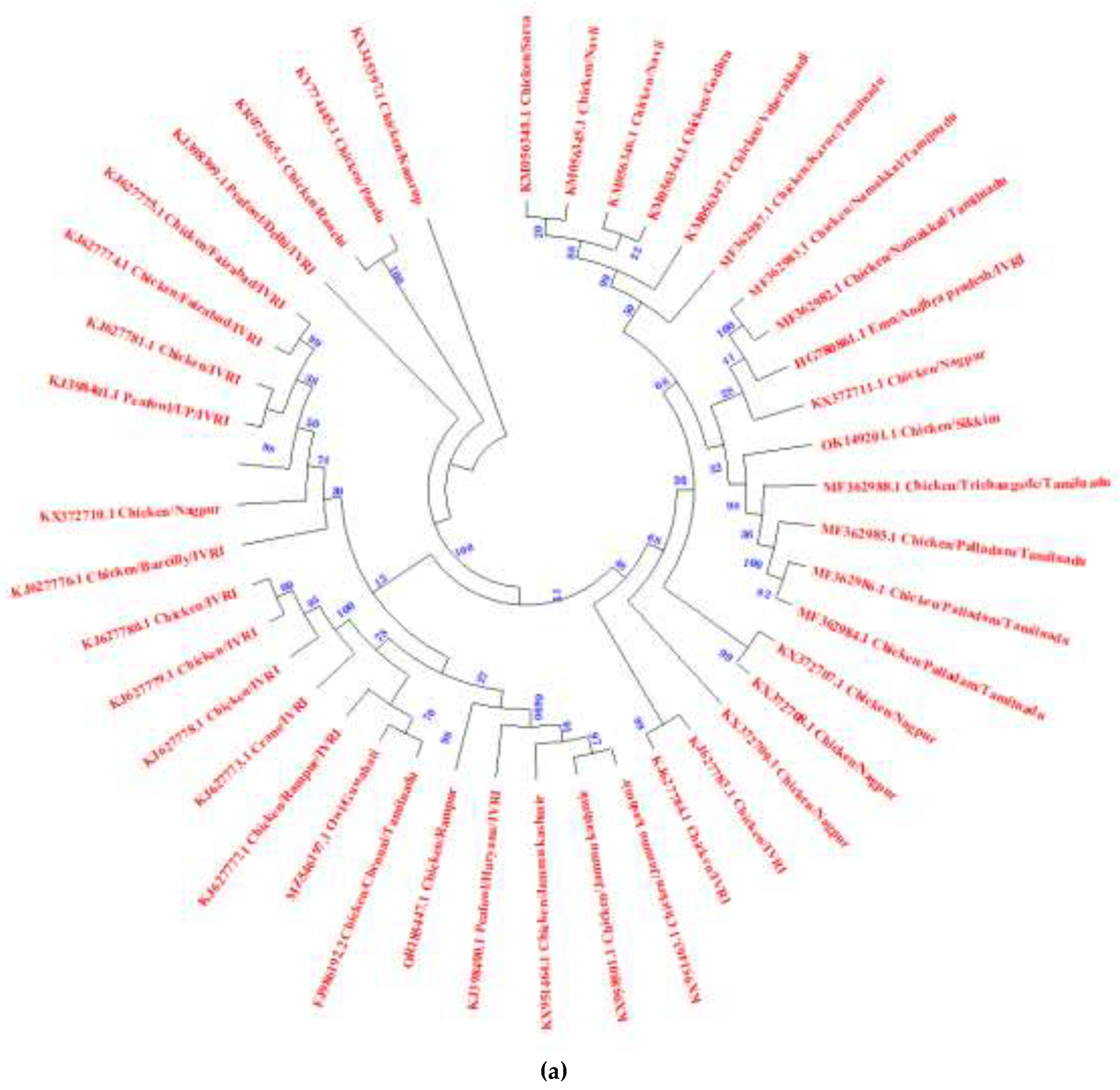

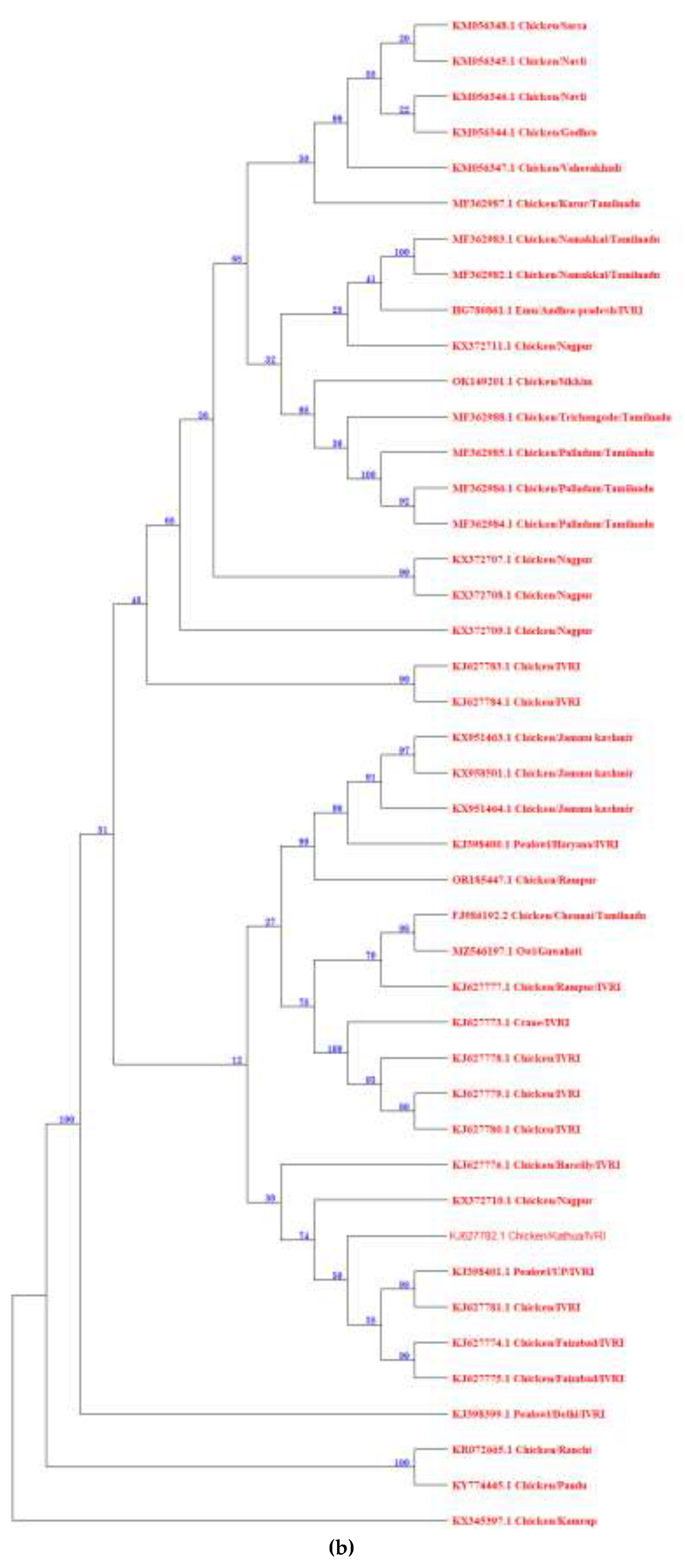

- Tamura K.; Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1993, 10, 512-526.

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evol. 1985, 39, 783-791.

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [CrossRef]

- Gowthaman, V.; Singh, S.D.; Dhama, K.; Desingu, P.A.; Kumar, A.; Malik, Y.S.; Munir, M. Isolation and characterization of genotype XIII Newcastle disease virus from Emu in India. VirusDisease 2016, 27, 315–318. [CrossRef]

- Desingu, P.A.; Singh, S.D.; Dhama, K.; Vinodhkumar, O.R.; Barathidasan, R.; Malik, Y.S.; Singh, R.; and Singh, R.K. Molecular characterization, isolation, pathology and pathotyping of peafowl (Pavo cristatus) origin Newcastle disease virus isolates recovered from disease outbreaks in three states of India. Avian Pathol. 2016b, 45, 674-682.

- Jakhesara, S.J.; Prasad, V, V.; Pal, J.K.; Jhala, M.K.; Prajapati, K, S.; Joshi, C, G.; Pathotypic and Sequence Characterization of Newcastle Disease Viruses from Vaccinated Chickens Reveals Circulation of Genotype II, IV and XIII and in India. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2016, 63, 523-39.

- Nath, B.; Kumar, S. Emerging variant of genotype XIII Newcastle disease virus from Northeast India. Acta Trop. 2017, 172, 64–69. [CrossRef]

- Gowthaman, V.; Ganesan, V.; Murthy, T.R.G.K.; Nair, S.; Yegavinti, N.; Saraswathy, P.V.; Kumar, G.S.; Udhayavel, S.; Senthilvel, K.; Subbiah, M. Molecular phylogenetics of Newcastle disease viruses isolated from vaccinated flocks during outbreaks in Southern India reveals circulation of a novel sub-genotype. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 66, 363–372. [CrossRef]

- Deka, P.; Nath, M.K.; Das, S.; Das, B.C.; Phukan, A.; Lahkar, D.; Bora, B.; Shokeen, K.; Kumar, A.; Deka, P. A study of risk factors associated with Newcastle disease and molecular characterization of genotype XIII Newcastle disease virus in backyard and commercial poultry in Assam, India. Res. Veter- Sci. 2022, 150, 122–130. [CrossRef]

- Jakhesara, S.J.; Patel, A.K.; Malsaria, P.; Pal, J.K.; Joshi, C.G. Seroconversion Studies of Indian Newcastle Disease Virus Isolates of Genotype XIII in 3 week Old Chickens. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Asia 2019, 16, 27–31. [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, M.; Abedi, M.; Bashashati, M.; Yousefi, A.R.; Abdoshah, M.; Mirzaie, S. Evaluation of the Newcastle disease virus genotype VII–mismatched vaccines in SPF chickens: A challenge efficacy study. Veter- Anim. Sci. 2024, 24, 100348. [CrossRef]

- Geetha, M.; Malmarugan, S.; Dinakaran, A.M.; Sharma, V.K.; Mishra, R.K.; Jagadeeswaran, D. Seroprevalence of New Castle disease, infectious Bursal disease and egg drop syndrome 76 in ducks. Ind. J. Vet. Anim. Res. 2008, 4, 200–202.

- Vegad, J. Drift variants of low pathogenic avian influenza virus: observations from India. World's Poult. Sci. J. 2014, 70, 767–774. [CrossRef]

- Kolluri, G. and Tyagi, J.S. Biosecurity and vaccination approaches in commercial (layers, broilers and broiler breeders) and backyard Poultry stocks. In: Tyagi, J.S. Gautham K. , Gopi, M., and Rokade, J.J., Eds.; 2019. Capacity Building of Field Functionaries on Diversified Poultry Production and Processing Technology under Off-Campus Collaborative Training Programme for Field Functionaries with MANAGE, Hyderabad ed.; Tyagi, J.S., G Kolluri., Gopi, M. and Rokade, J.J., Eds.; ICAR-CARI, Bareilly, India. 2019: Volume 1, pp. 114-133.

- Dey, S.; Chellappa, M.M.; Gaikwad, S.; Kataria, J.M.; Vakharia, V.N. Genotype Characterization of Commonly Used Newcastle Disease Virus Vaccine Strains of India. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e98869. [CrossRef]

- Iyer, G.S.; Hashmi, Z.A. Studies on Newcastle (Ranikhet) disease virus strain differences in amenability to attenuations. Indian J. Vet. Sci. 1945, 15, 155–157.

- Sharma, R.; Sandeep, S.; Sanjay, K. Estimated Incremental Benefits of Complete Vaccination Against Newcastle Disease in Layers”. Acta. Sci. Vet. Sci. 2023, 5, 55-57.

- Hu, Z.; Hu, S.; Meng, C.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Liu, X. Generation of a Genotype VII Newcastle Disease Virus Vaccine Candidate with High Yield in Embryonated Chicken Eggs. Avian Dis. 2011, 55, 391–397. [CrossRef]

- Roohani, K.; Tan, S.W.; Yeap, S.K.; Ideris, A.; Bejo, M.H.; Omar, A.R. Characterisation of genotype VII Newcastle disease virus (NDV) isolated from NDV vaccinated chickens, and the efficacy of LaSota and recombinant genotype VII vaccines against challenge with velogenic NDV. J. Veter- Sci. 2015, 16, 447–457. [CrossRef]

- Dewidar, A.A.A.; Kilany, W.H.; El-Sawah, A.A.; Shany, S.A.S.; Dahshan, A.-H.M.; Hisham, I.; Elkady, M.F.; Ali, A. Genotype VII.1.1-Based Newcastle Disease Virus Vaccines Afford Better Protection against Field Isolates in Commercial Broiler Chickens. Animals 2022, 12, 1696. [CrossRef]

- Sultan, H.A.; Elfeil, W.K.; Nour, A.A.; Tantawy, L.; Kamel, E.G.; Eed, E.M.; El Askary, A.; Talaat, S. Efficacy of the Newcastle Disease Virus Genotype VII.1.1-Matched Vaccines in Commercial Broilers. Vaccines 2021, 10, 29. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.-H.; Kwon, H.-J.; Kim, T.-E.; Kim, J.-H.; Yoo, H.-S.; Park, M.-H.; Park, Y.-H.; Kim, S.-J. Characterization of a Recombinant Newcastle Disease Virus Vaccine Strain. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2008, 15, 1572–1579. [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.J.; Estevez, C.; Yu, Q.; Suarez, D.L.; King, D.J. Comparison of Viral Shedding Following Vaccination With Inactivated and Live Newcastle Disease Vaccines Formulated With Wild-Type and Recombinant Viruses. Avian Dis. 2009, 53, 39–49. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Nayak, B.; Samuel, A.; Paldurai, A.; Kanabagattebasavarajappa, M.; Prajitno, T.Y.; Bharoto, E.E.; Collins, P.L.; Samal, S.K. Generation by Reverse Genetics of an Effective, Stable, Live-Attenuated Newcastle Disease Virus Vaccine Based on a Currently Circulating, Highly Virulent Indonesian Strain. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e52751. [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, K.M.; Afonso, C.L.; Yu, Q.; Miller, P.J. Newcastle disease vaccines-A solved problem or a continuous challenge? Vet. Microbiol. 2017, 206, 126–136.

- Sultan, H.A.; Talaat, S.; Elfeil, W.K.; Selim, K.; Kutkat, M.A.; Amer, S.A.; Choi, K.-S. Protective efficacy of the Newcastle disease virus genotype VII–matched vaccine in commercial layers. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 1275–1286. [CrossRef]

- Fawzy, M.; Ali, R.R.; Elfeil, W.K.; Saleh, A.A.; El-Tarabilli, M.M.A. Efficacy of inactivated velogenic Newcastle disease virus genotype VII vaccine in broiler chickens. 2020, 11, 113–120. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Huang, M.; Fung, T.S.; Luo, Q.; Ye, J.X.; Du, Q.R.; Wen, L.H.; Liu, D.X.; Chen, R.A. Rapid Development of an Effective Newcastle Disease Virus Vaccine Candidate by Attenuation of a Genotype VII Velogenic Isolate Using a Simple Infectious Cloning System. Front. Veter- Sci. 2020, 7. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.A.; Panickan, S.; Bindu, S.; Kumar, V.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Saxena, S.; Shrivastava, S.; Dandapat, S. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of an inactivated Newcastle disease virus vaccine encapsulated in poly-(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102679. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-W.; Bakre, A.; Olivier, T.L.; Alvarez-Narvaez, S.; Harrell, T.L.; Conrad, S.J. Toll-like Receptor Ligands Enhance Vaccine Efficacy against a Virulent Newcastle Disease Virus Challenge in Chickens. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1230. [CrossRef]

- Hongzhuan, Z.; Ying, T.; Xia, S.; Jinsong, G.; Zhenhua, Z.; Beiyu, J.; Yanyan, C.; Lulu, L.; Jue, Z.; Bing, Y.; et al. Preparation of the inactivated Newcastle disease vaccine by plasma activated water and evaluation of its protection efficacy. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 104, 107–117. [CrossRef]

- Baylor, N.W.; Egan, W.; Richman, P. Aluminum salts in vaccines—US perspective. Vaccine. 2002, 20, S18-S23.

- Moni, S.S.; Abdelwahab, S.I.; Jabeen, A.; Elmobark, M.E.; Aqaili, D.; Gohal, G.; Oraibi, B.; Farasani, A.M.; Jerah, A.A.; Alnajai, M.M.A.; et al. Advancements in Vaccine Adjuvants: The Journey from Alum to Nano Formulations. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1704. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Guo, S.; Jin, Z.; Zhao, K. Adjuvanted quaternized chitosan composite aluminum nanoparticles-based vaccine formulation promotes immune responses in chickens. Vaccine 2023, 41, 2982–2989. [CrossRef]

- Palese, P.; Zheng, H.; Engelhardt, O.G.; Pleschka, S.; García-Sastre, A. Negative-strand RNA viruses: genetic engineering and applications.. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1996, 93, 11354–11358. [CrossRef]

- Peeters, B.P.H.; de Leeuw, O.S.; Koch, G.; Gielkens, A.L.J. Rescue of Newcastle Disease Virus from Cloned cDNA: Evidence that Cleavability of the Fusion Protein Is a Major Determinant for Virulence. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 5001–5009. [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, R.; Chan, J.; Prabakaran, M. Vaccines against Major Poultry Viral Diseases: Strategies to Improve the Breadth and Protective Efficacy. Viruses 2022, 14, 1195. [CrossRef]

- Veits, J.; Wiesner, D.; Fuchs, W.; Hoffmann, B.; Granzow, H.; Starick, E.; Mundt, E.; Schirrmeier, H.; Mebatsion, T.; Mettenleiter, T.C.; et al. Newcastle disease virus expressing H5 hemagglutinin gene protects chickens against Newcastle disease and avian influenza. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006, 103, 8197–8202. [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Chellappa, M.M.; Pathak, D.C.; Gaikwad, S.; Yadav, K.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Vakharia, V.N. Newcastle Disease Virus Vectored Bivalent Vaccine against Virulent Infectious Bursal Disease and Newcastle Disease of Chickens. Vaccines 2017, 5, 31. [CrossRef]

- Basavarajappa, M.K.; Kumar, S.; Khattar, S.K.; Gebreluul, G.T.; Paldurai, A.; Samal, S.K. A recombinant Newcastle disease virus (NDV) expressing infectious laryngotracheitis virus (ILTV) surface glycoprotein D protects against highly virulent ILTV and NDV challenges in chickens. Vaccine 2014, 32, 3555–3563. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, D.P.; Yadav, K.; Pathak, D.C.; Ramamurthy, N.; D’silva, A.L.; Marriappan, A.K.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Vakharia, V.N.; Chellappa, M.M.; Dey, S. Recombinant Newcastle Disease Virus (NDV) Expressing Sigma C Protein of Avian Reovirus (ARV) Protects against Both ARV and NDV in Chickens. Pathogens 2019, 8, 145. [CrossRef]

- Shirvani, E.; Paldurai, A.; Manoharan, V.K.; Varghese, B.P.; Samal, S.K. A Recombinant Newcastle Disease Virus (NDV) Expressing S Protein of Infectious Bronchitis Virus (IBV) Protects Chickens against IBV and NDV. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11951, Correction in Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 762. [CrossRef]

- Chellappa, M.M.; Dey, S.; Pathak, D.C.; Singh, A.; Ramamurthy, N.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Mariappan, A.K.; Dhama, K.; Vakharia, V.N. Newcastle Disease Virus Vectored Chicken Infectious Anaemia Vaccine Induces Robust Immune Response in Chickens. Viruses 2021, 13, 1985. [CrossRef]

- Palya, V.; Kiss, I.; Tatar-Kis, T.; Mato, T.; Felfoldi, B.; Gardin, Y. Advancement in vaccination against Newcastle disease: recombinant HVT NDV provides high clinical protection and reduction challenge virus shedding, with the absence of vaccine reaction. Avian Dis. 2012, 56, 282–287.

- Lee, K.; A Mackley, V.; Rao, A.; Chong, A.T.; A Dewitt, M.; E Corn, J.; Murthy, N.; Inc, G.; Berkeley; States, U. Synthetically modified guide RNA and donor DNA are a versatile platform for CRISPR-Cas9 engineering. eLife 2017, 6. [CrossRef]

- Véron, N.; Qu, Z.; Kipen, P.A.; Hirst, C.E.; Marcelle, C. CRISPR mediated somatic cell genome engineering in the chicken. Dev. Biol. 2015, 407, 68–74. [CrossRef]

- Oishi, I.; Yoshii, K.; Miyahara, D.; Kagami, H.; Tagami, T. Targeted mutagenesis in chicken using CRISPR/Cas9 system. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23980–23980. [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.W.; Joshi, P. Egg allergy: An update. J. Paediatr. Child Heal. 2013, 50, 11–15. [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.D.; Lee, J.H.; Song, S.; Kim, S.W.; Han, J.S.; Shin, S.P.; Park, B.C.; Park, T.S. Generation of myostatin-knockout chickens mediated by D10A-Cas9 nickase. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 5688-5696.

- Idoko-Akoh, A.; Goldhill, D.H.; Sheppard, C.M.; Bialy, D.; Quantrill, J.L.; Sukhova, K.; Brown, J.C.; Richardson, S.; Campbell, C.; Taylor, L.; et al. Creating resistance to avian influenza infection through genome editing of the ANP32 gene family. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Alkhodairy, H.F.; Ashraf, I.; Khalil, A.B. CRISPR/Cas System Toward the Development of Next-Generation Recombinant Vaccines: Current Scenario and Future Prospects. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2022, 48, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Vilela, J.; Rohaim, M.A.; Munir, M. Application of CRISPR/Cas9 in Understanding Avian Viruses and Developing Poultry Vaccines. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Bassett, A; Nair, V. Targeted editing of avian herpesvirus vaccine vector using CRISPR/Cas9 nucleases. Vaccine Technol. 2016, 1,1-7.

- Tang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Pedrera, M.; Chang, P.; Baigent, S.; Moffat, K.; Shen, Z.; Nair, V.; Yao, Y. A simple and rapid approach to develop recombinant avian herpesvirus vectored vaccines using CRISPR/Cas9 system. Vaccine 2017, 36, 716–722. [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Sadigh, Y.; Moffat, K.; Shen, Z.; Nair, V.; Yao, Y. Generation of A Triple Insert Live Avian Herpesvirus Vectored Vaccine Using CRISPR/Cas9-Based Gene Editing. Vaccines 2020, 8, 97. [CrossRef]

- Dronina, J.; Samukaite-Bubniene, U.; Ramanavicius, A. Towards application of CRISPR-Cas12a in the design of modern viral DNA detection tools (Review). J. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Atasoy, M.O.; Rohaim, M.A.; Munir, M. Simultaneous Deletion of Virulence Factors and Insertion of Antigens into the Infectious Laryngotracheitis Virus Using NHEJ-CRISPR/Cas9 and Cre–Lox System for Construction of a Stable Vaccine Vector. Vaccines 2019, 7, 207. [CrossRef]

| Type of bird | Vaccination regime |

|---|---|

| Commercial layers (BV300, IB) | 5-6 days ND Lasota, + ND Killed, 11 wk R2B/RDVK, 16 wk ND Killed |

| Commercial broilers (Cobb 430Y, Ross) | DOH: ND Killed, 5-6 days ND Lasota, 10 days ND Killed, 28 days ND Live Booster |

| Dual-purpose and coloured birds | 0 day: ND D58, 21 days: D58, 56 days: R2B, 14 wk: D58 clone, 16 wk: ND Killed |

| Vaccine strains | Combination (if any) | |

|---|---|---|

| Live | Killed | |

| F/B1/Lasota/D58/ D26+FC126/Nobilis ND clone 30/VH clone/R2B/CH-80 cloned/CL-79 | Lasota/VH | ND+IB ND+IB+IBD |

| Strains | F1 region | Fusion protein clevage site | F2 region | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 8 | 9 | 13 | 16 | 20 | 22 | 29 | 30 | 82 | 112 | 113 | 114 | 115 | 116 | 117 | 121 | 124 | 145 | 192 | 195 | 203 | 231 | 232 | 272 | 288 | 396 | 421 | 482 | 552 | 553 | ||||

| AEL75045.1 (LaSota) | R | K | N | M | T | A | V | A | N | D | G | R | Q | G | R | L | I | G | K | K | Q | A | N | K | N | T | M | K | E | K | M | |||

| AHN09749.1 (F) | R | K | N | M | T | A | V | A | N | D | G | R | Q | G | R | L | I | G | K | K | Q | A | N | K | N | T | M | K | E | K | M | |||

| AFX98109.1 (R2B) | R | K | N | M | T | A | V | A | N | D | R | R | Q | K | R | F | I | G | K | K | Q | A | N | K | N | T | M | K | E | K | M | |||

| UQW17861.1 (Genotype 7) | K | R | I | L | I | M | I | T | S | E | K | R | Q | K | R | F | V | S | N | N | R | T | T | Q | Y | N | I | R | A | R | A | |||

| AHG26218.1 (Genotype VII) | K | R | I | L | I | M | I | T | S | E | R | R | Q | K | R | F | V | S | N | N | R | T | T | Q | Y | N | I | R | A | R | A | |||

| ATU83336.1 (Genotype XIII) | K | R | I | L | I | M | I | T | S | E | R | R | Q | K | R | F | V | S | N | N | R | T | T | Q | Y | N | I | R | A | R | A | |||

| AIQ78308.1 (Genotype XIII) | K | R | I | L | I | M | I | T | S | E | R | R | Q | K | R | F | V | S | N | N | R | T | T | Q | Y | N | I | R | A | R | A | |||

| Strain | JF950510.1_Lasota | KC987036.1_F | JX316216.1_R2B |

|---|---|---|---|

| JF950510.1_Lasota | - | 96.07 | 93.616 |

| KC987036.1_F | 96.07 | - | 93.04 |

| JX316216.1_R2b | 93.62 | 93.04 | - |

| KF740478.1_ Genotype VII | 84.58 | 84.05 | 84.73 |

| MZ546197.1_Genotype VII | 83.05 | 84.96 | 82.69 |

| KY774445.1_Genotype XIII | 83.22 | 82.88 | 83.81 |

| KM056347.1_Genotype XIII | 83.20 | 85.43 | 83.56 |

| F gene | AEL75045.1_Lasota | AHN09749.1 _F | AFX98109.1_ R2B |

|---|---|---|---|

| AEL75045.1 _Lasota | - | 98.37 | 94.03 |

| AHN09749.1_F | 98.37 | - | 94.94 |

| AFX98109.1_R2B | 94.03 | 94.94 | - |

| AHG26218.1_Genotype VII | 89.67 | 89.67 | 89.86 |

| UQW17861.1_Genotype VII | 88.77 | 88.77 | 88.77 |

| ATU83336.1 _Genotype XIII | 88.77 | 88.59 | 88.95 |

| AIQ78308.1_Genotype XIII | 88.77 | 88.77 | 88.95 |

| HN gene | AEL75044.1_ Lasota | AHN09747.1_ F | AFX98110.1_ R2B |

| AEL75044.1_Lasota | - | 96.19 | 92.55 |

| AHN09747.1_F | 96.19 | - | 90.99 |

| AFX98110.1_R2B | 92.55 | 90.99 | - |

| AHG26219.1_Genotype VII | 86.97 | 86.27 | 88.01 |

| UQW17859.1_Genotype VII | 87.52 | 86.29 | 88.05 |

| ATU83337.1_Genotype XIII | 88.25 | 87.19 | 87.72 |

| AIQ78309.1_Genotype XIII | 85.92 | 85.04 | 86.60 |

| Features | Vaccine strains | |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional genotypes | Newer genotypes | |

| GI, GII across the globe | GV (America), GVI (Pigeons), GVII (Asia and Africa) | |

| Protection from morbidity & mortality |

++ |

+++ |

| Reduction in virus shedding | + | +++ |

| Field virus silent dissemination & spill over | +++ | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).