1. Introduction

Pigeons (

Columba livia) are hosts to a variety of diseases, including bacterial, viral, and parasitic. One infectious agent of particular importance in this species is pigeon paramyxovirus type 1 (PPMV-1) [

1]. PPMV-1 is the primary cause of diseases in free-ranging and captive pigeons and doves [

2,

3]. It is closely related to Newcastle Disease virus (NDV), which causes severe outbreaks in chickens. Both PPMV-1 and NDV are enveloped viruses containing a negative-sense, single-stranded RNA genome that belongs to class II genotype VI (formerly known as genotype Vib or lineage 4b) of Paramyxovirus type 1 [

4,

5,

6]. These viruses are classified into the same serotype within the

Orthoavulavirus genus,

Avulavirinae subfamily, and

Paramyxoviridae family within the order

Mononegavirales [

7,

8].

In the late 1970s, PPMV-1 was predicted to have originated in the Middle East and spread to Europe [

9], where the first outbreak was reported in pigeons in the early 1980s [

10,

11]. Since then, PPMV-1 has become endemic in many countries globally [

12,

13,

14]. The global spread of PPMV-1 is likely due to long-distance migration, competition flights, ornamental exhibitions, and the trade of live birds [

15].

Since 1981, pigeons in Egypt exhibited clinical signs comparable to NDV infection, and the presence of NDV antigens was detected in serum samples taken from diseased pigeons in 1984 [

9,

16]. As the viruses of PPMV-1 genotype VI are known to infect the members of the family

Columbidae they can also infect other wild birds and domestic poultry [

17,

18,

19]. The virulence of NDV strains in chickens is quite variable and classified into three pathotypes: Lentogenic, mesogenic, and velogenic. These pathotypes are determined using assays such as mean death time (MDT) of chicken embryos, intracerebral pathogenicity index (ICPI), intravenous pathogenicity index (IVPI), and genomic sequences analysis [

20,

21,

22]. However, most PPMV-1 strains are virulent in pigeons; their virulence in chickens is largely predicted based on the presence of multiple basic amino acids at the cleavage site motif of the viral fusion (F) protein [

23,

24,

25]. This modulates the virulence phenotype from non-virulent to highly virulent phenotype in chickens [

26,

27]. Thus, the pigeon-originated viruses pose a constant threat to the poultry industry [

23,

28,

29]. Depending on the genetic makeup of the infecting PPMV-1 strain, the pigeons experience a range of differential clinical signs, including nervous (tremors of the neck and wings, bilateral or unilateral locomotor disorders, torticollis, paralysis, and disturbed equilibrium), digestive (polydipsia, polyuria, anorexia, and diarrhea) [

24,

30,

31] and/or respiratory (gasping, coughing, sneezing, and tracheal rales) signs [

19].

PPMV-1 is enzootic in Egypt and causes significant negative economic impacts on commercial poultry production [

19,

32]. Proper and effective methods of prevention and control, in addition to diagnostic methods, are important for pigeon paramyxoviruses [

13]. While vaccination of racing pigeons against NDV is compulsory in many countries [

33], most pigeon-rearing strategies in Egypt vary and do not necessitate routine immunization against NDV [

32]. Therefore, they are exposed to spillover from wild, unvaccinated pigeons. Thus, improving pigeon vaccination regimen against PPMV-1 could potentially reduce the disease burden in Egypt.

Several vaccination studies have evaluated the protective efficacy of available NDV poultry vaccines, such as live formulation of NDV LaSota or its variant Clone-30 strains which belong to Genotype II of Class II paramyxovirus [

34]. The immunogenicity of pigeon-derived Genotype VI differs from the chicken-origin Genotype II vaccine strain of NDV [

35,

36]. However, little is known about the protective properties of an inactivated PPMV-1 vaccine in comparison to commercial NDV LaSota vaccine in pigeons [

37].

Despite extensive research on the virus, further studies on the phenotypic characteristics of different strains of PPMV-1 prevalent in nature are needed. Experimental infections with contemporary strains dominating in the field could provide insights into their virulence phenotypes and assess the effectiveness of available commercial vaccines in mitigating their impacts.

This study evaluates the phenotypic properties (MDT, ICPI, IVPI) of the PPMV-1 strain isolated from pigeons (Pigeon/Egypt/Sharkia-19/2015/KX580988) in both chickens and pigeons. Additionally, it assesses the effectiveness of available commercial paramyxovirus vaccines in protecting pigeons from this PPMV-1 isolate.

These findings will enhance our understanding, diagnosis, and prevention of PPMV-1 infections in regions with intensive pigeon rearing. They will also help in reducing the risk of disease transmission and optimizing vaccination programs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Considerations

The experiment design and protocol were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Zagazig University, Egypt (approval ID ZU-IACUC/2/F/26/2020). This study was conducted in strict accordance with the approved guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Birds were allowed to acclimatise to the facilities before the study began. Welfare checks were performed on the birds two to three times daily, and clinical scores were recorded to assess humane endpoints. Any bird showing signs of disease that met a humane endpoint was euthanised.

2.2. Birds

Domestic pigeons (Colomba livia) N=99 used in this study were hatched and reared in a backyard rearing system for 4 weeks and kept non-vaccinated against NDV and PPMV-1. One-day-old specific-pathogen free (SPF) white leghorn chicks N=20 (Koom Oshiem, Fayoum, Egypt) were used to characterise the PPMV-1 strain and evaluate the vaccine’s efficacy. All birds were housed in separate experimental units at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Zagazig University.

Before the experiment, the health status of domestic pigeons was observed for 7–14 days. Five pigeons were randomly selected and euthanized, and then all tissues and organs were carefully examined for any macro-pathological lesions. Blood samples and tracheal and cloacal swabs were collected from the remaining pigeons.

It was found that the pigeons did not show any signs, and none of the euthanized birds had pathological lesions. The collected serum samples lacked avian paramyxovirus-1 (APMV-1) and avian influenza virus (AIV)-specific hemagglutination inhibition (HI) antibodies by the HI test. The HI test was performed using hyperimmune serum against NDV, PPMV-1 [

38], and H5, H9 AIV (Department of Avian and Rabbit Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Zagazig University) according to the standard method of World Organisation of Animal Health (WOAH) [

39]. Antibody titers of 1:4 or greater were used to indicate past infection, current exposure, maternal antibodies, or vaccination titers. Likewise, none of the swab samples had hemagglutinating agents using isolation in SPF embryonated chicken eggs (SPF-ECEs) and then identification by a rapid hemagglutination (HA) assay.

All animals, experimental procedures and protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Zagazig University, Egypt. The humane endpoints for chickens and pigeons inoculated with PPMV-1 were followed such that any infected bird showing signs of green watery diarrhoea, nervous symptoms (such as twisting of the head and neck or loss of balance), or difficulty in breathing (mouth breathing with an extended neck) was immediately euthanised and recorded as having reached severe disease signs.

2.3. Vaccines

Two vaccines used in this study. (i) Live freeze-dried form of LaSota lentogenic strain of Newcastle Disease virus (CEVAC® NEW L, Ceva Sante Animale Egypt, Al Sheikh Zayed, Giza) which contained 106 EID50 of vaccinal virus/dose and was delivered via eye drops of 50 µL per dose. (ii) Formalized inactivated pigeon paramyxovirus vaccine (containing 1010 EID50 /mL) obtained from the Veterinary Serum and Vaccine Research Institute (VSVRI, Abassia, Cairo, Egypt, Batch number 1907) and delivered via subcutaneous injection in the third middle of the neck at 0.5 mL dose per bird.

2.4. Pigeon Paramyxovirus-1 (PPMV-1) Isolate

The current study used the A PPMV-1 isolate named Pigeon/Egypt/Sharkia-19/2015/KX580988, (GenBank ID: KX580988) [

32]. This isolate originated from a native pigeon flock in Al-Shabanat, Sharkia, Egypt, which had an outbreak in 2015. This flock was vaccinated with NDV LaSota vaccine and suffered from noteworthy nervous symptoms and diarrhea, with up to 80% mortality. Nephrosis, nephritis, enteritis, and a congested brain were recorded during necropsy. This isolate was identified as PPMV-1 by using hyperimmune serum against PPMV-1 prepared by Hamouda

et al. [

38] with a titer of 4 log

2 in the HI test. Subsequently, RT-PCR was used to identify the viral RNA, and sequencing analysis of the isolate confirmed the presence of a poly-basic fusion protein cleavage site

112KRQKRF

117, identifying the strain as velogenic PPMV-1 and belonged to subgenotype Vib.2, class II [

32]. PPMV-1 isolate was propagated using inoculation in the allantoic sac of 10-day-old SPF embryonated chicken eggs (SPF-ECEs). After 5 days incubation at 37°C and relative humidity of 70%, ECEs with both live and dead embryos were investigated and allantoic fluids (Afs) harvested. Collected Afs were tested for hemagglutinating virus titer by a micro-plate hemagglutination (HA) test using 1% (v/v) washed chicken red blood cells (RBCs) as recommended by WOAH [

39].

2.5. Biological Characterization

The pathogenic potential of the isolate was determined by mean death time (MDT), intracerebral pathogenicity index (ICPI), and intravenous pathogenicity index (IVPI) tests.

2.5.1. Mean Death Time (MDT) and Virus Titration

The MDT test was conducted using 10-day-old SPF-ECEs and calculated according to the method previously described [

4]. The value of MDT was determined as the mean time in hours necessary for the death of all ECEs. Specifically, MDT values greater than 90 h indicate low virulence, between 60 and 90 h indicate moderate virulence, and less than 60 h indicate high virulence. The embryonic infectious dose of 50% (EID

50) of the isolate was calculated using the Reed and Muench method [

40] in SPF-ECEs. The virus stock was diluted in phosphate-buffered saline and standardized to 10

6 EID

50/0.1 mL.

2.5.2. Intracerebral Pathogenicity Index (ICPI), and Intravenous Pathogenicity Index (IVPI)

A total of thirty clinically healthy, 5-week-old domestic pigeons (

Colomba livia) and twenty, one-day-old SPF chicks were used to detect the ICPI [

39,

41] and IVPI [

4]. To further elucidate the pathogenic potential of the virus via this pathway, ICPI was performed in SPF chicks as specified in all standard methods and was also applied in pigeons, which are natural hosts of the virus.

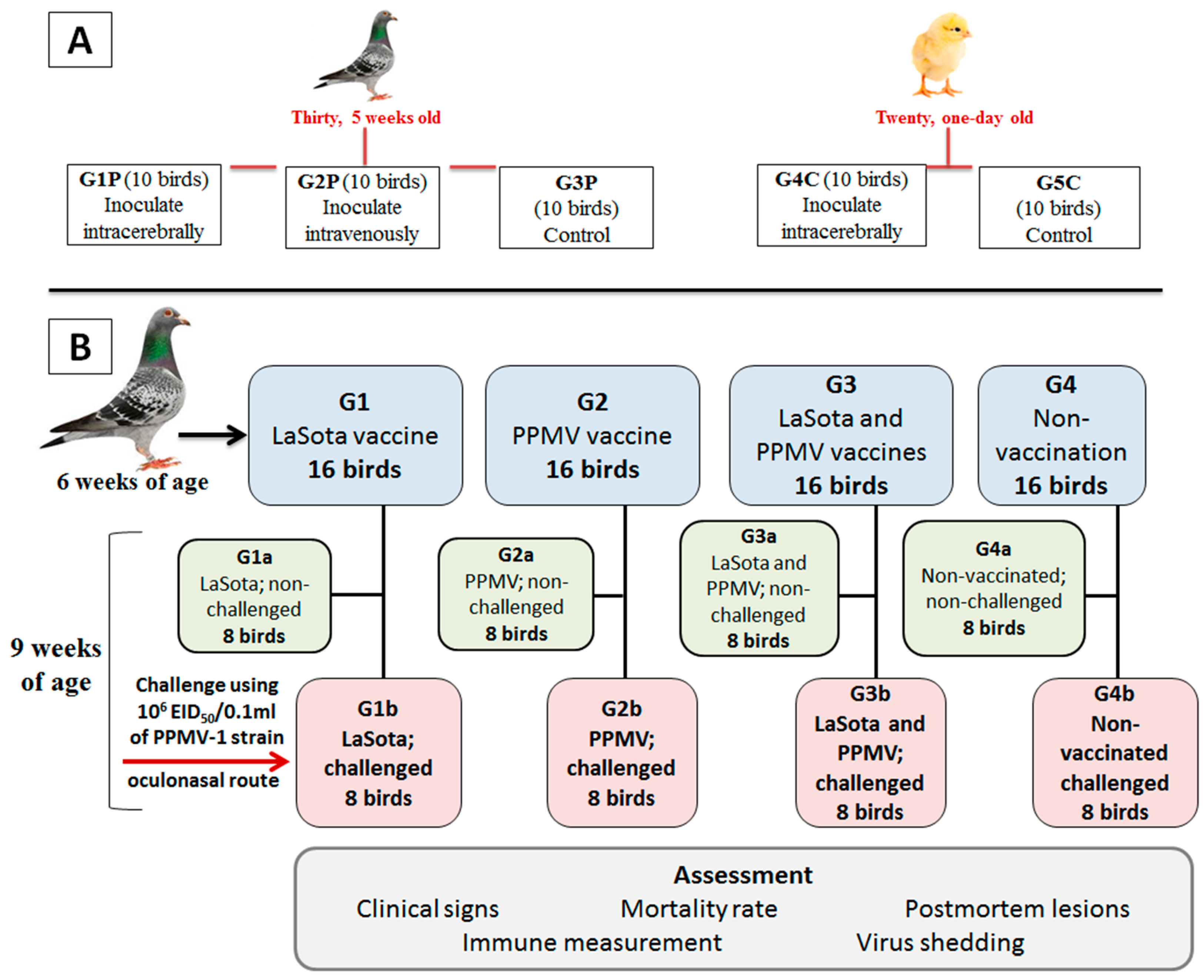

Three groups (G1P–G3P) of 10 pigeons per group and two groups (G4C–G5C) of 10 SPF chicks per group were prepared for inoculation. Groups G1P and G4C were inoculated intracerebrally (I/C) with 50 µL of the ten-fold dilution of the fresh virus AF stock containing HA titre of 2

10 (10

7.6 EID

50) in 0.1 ml. Group G2P was inoculated intravenously (I/V) with 0.1 ml of the ten-fold dilution of the same fresh virus AF stock (

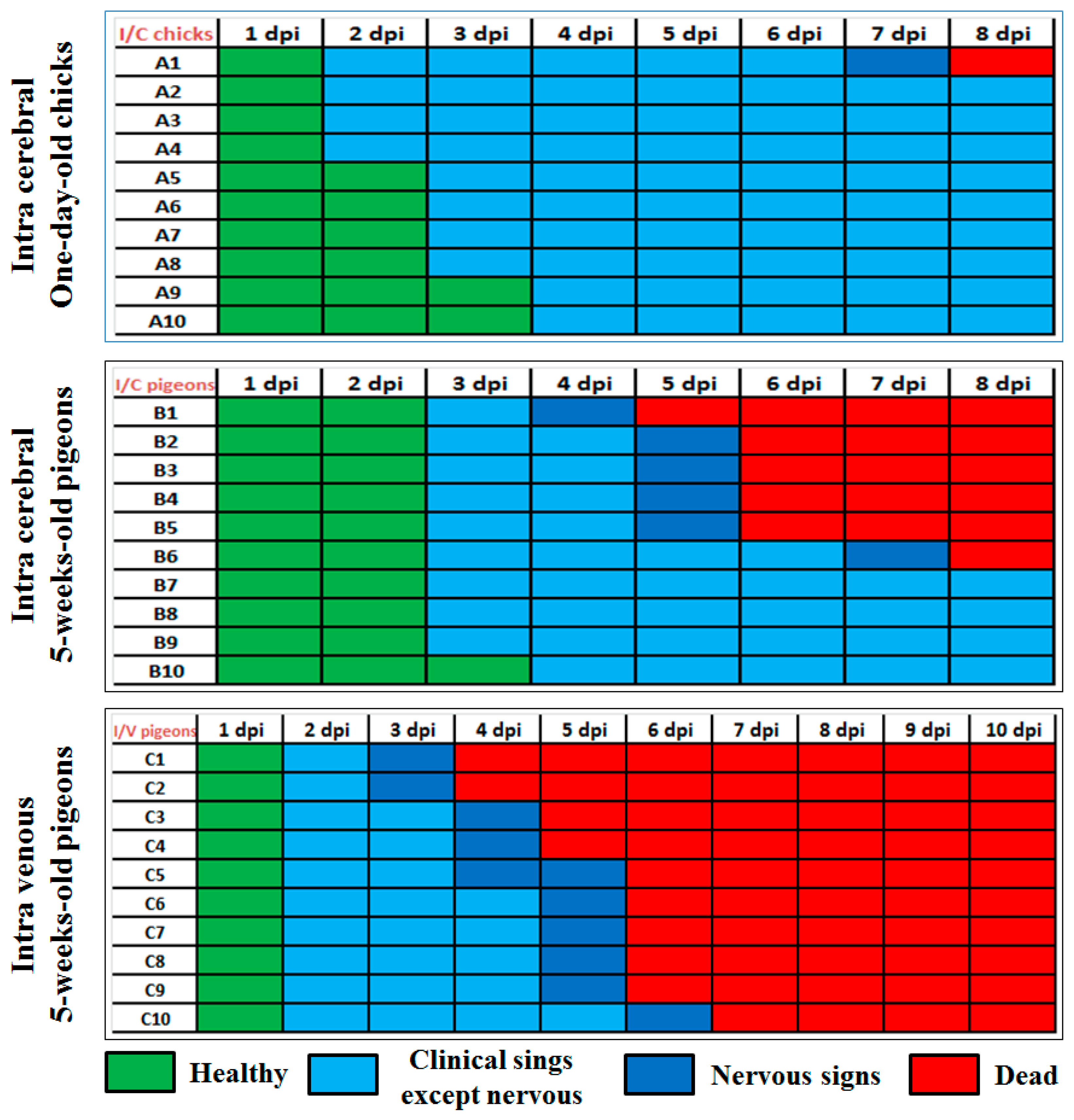

Figure 1A). Groups G3P and G5C were used as mock-inoculated control birds and were housed separately from the other birds. The birds were observed and examined daily for 8 and 10 days in intracerebrally and intravenously inoculated groups, respectively. The observed clinical signs and mortalities were recorded and scored to determine the pathogenicity indexes.

The ICPI Involves scoring sick or dead (0 = normal; 1 = sick; and 2 = dead). ICPI below 0.7 was considered to be of low virulence, and those with an ICPI equal to or greater than 0.7 were considered to be virulent [

39,

42]. The IVPI involves scoring illness (0 = normal; 1 = sick; 2 = paralyzed or nervous signs; and 3 = dead) after IV inoculation. The velogenic strains have an IVPI score of 2–3, mesogenic 0–0.5, and lentogenic of zero [

41].

2.6. Evaluating Vaccine Efficacy

2.6.1. Pigeon Experiment Design

Sixty-four 6-week-old clinically healthy domestic pigeons (

Colomba livia) were divided into 4 groups (G1–G4) of 16 birds each. The experimental pigeons were kept in the experiment units under controlled conditions for the period of the study and received consistent feed and water ad libitum. The birds in groups 1, 2, and 3 were vaccinated with live NDV LaSota, inactivated PPMV, and dual vaccine- one dose each of NDV LaSota and PPMV, respectively (

Figure 1B). The NDV LaSota vaccine was applied on the first day of the experiment and boosted after two weeks (8 weeks of age). On the second day of the experiment, the formalized-inactivated PPMV vaccine was administered once. Pigeons in group 4 were kept as the control (non-vaccinated) group.

At 9 weeks of age, four pigeon groups were subdivided into 8 subgroups (G1a, G2a, G3a, and G4a) and (G1b, G2b, G3b, and G4b). The G1b, G2b, G3b and G4b subgroups were challenged intra-oculonasally with dose of 0.1 mL containing 106 EID50 of the challenge virus “Pigeon/Egypt/Sharkia-19//2015/KX580988”. The G1a, G2a, G3a and G4a subgroups remained unchallenged. Serum samples were collected weekly from each subgroup (3 birds per subgroup) to determine the avian paramyxovirus-specific antibody titers using the hemagglutination inhibition (HI) test. Post-challenge, pigeons were monitored twice daily for 14 days to record clinical signs and mortality. The clinical signs of pigeons in the different groups were scored daily according to their clinical condition (0 = healthy; 1 = diseased; 2 = nervous signs; 3 = dead). The clinical index was calculated analogously to determining the intravenous pathogenicity index (IVPI). As determined by IVPI, the course of disease from inoculation was nearly the same as that from natural infection via the oculonasal route. In addition, the observation period was extended to 14 days to cover the time period from productive infection till complete recovery. Pigeons that died suddenly during the experiment were immediately necropsied. Birds that were culled upon reaching humane endpoints, as well as those that recovered from infection and did not experience humane endpoints, were euthanised at the end of the observation period for post-mortem examination and tissue collection to detect disease lesions. Three pooled tracheal and cloacal swabs were collected from 6 randomly selected pigeons (2 swabs per pool) at 3-, 5-, and 7-day post-challenge (dpc) to determine the virus shedding.

2.6.2. Immune Response

The HI test was performed on the collected serum samples according to the procedures listed in the WOAH [

39] using 4 hemagglutination units (HAU) of the PPMV-1 strain (Pigeon/Egypt/Sharkia-19/2015/KX580988) as a whole virus, the LaSota vaccine strain of NDV (Pestikal

® LASOTA SPF), and 1% chicken red blood cells (RBCs). The serum samples were thermally inactivated for 30 minutes at 56 °C. Twofold serial dilutions were carried out, and the HI titer was expressed as log

2 of the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution, which suppressed the HA activity.

2.6.3. Virus Shedding Determination

As previously mentioned, tracheal and cloacal swabs were collected on the third, fifth and 7

th dpc from different subgroups. These swabs were suspended in 1.5 mL minimum essential media (MEM) containing antibiotics (Penstrept, Lonza) then clarified by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. Virus titration was implemented using Real-Time Quantitative Reverse Transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). Viral RNA was extracted from the supernatant using the QIAamp MinElute Virus Spin kit (QiagenGmbH, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturers’ protocol. The extracted RNA was subjected to one-step real time RT-PCR using AgPath-ID

TM one –step RT-PCR Kit (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA) for detection and titration of PPMV-1. The following primers and probe specific to F protein gene as designed by Sabra

et al. [

43] were used: forward primer 5′- TGATTCCATCCGCAGGATACAAG -3′, reverse primer 5′- GCTGCTGTTATCTGTGCCGA-3′, and probe: F-4876 5–[6-FAM] AAGCGYTTCTGTCTCYTTCCT CCT [BHQ_1]–3′. The amplification was performed in an Applied Biosystems™ StepOne™ Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), with cycle conditions as mentioned by Fuller

et al. [

44]. Overall, the amount of viral RNA in the swab samples was based on the threshold cycle (Ct) values obtained by RT- qPCR.

2.7. Microscopic Examination to Track the Pathological Pathway of PPMV-1 (Pigeon/Egypt/Sharkia-19/2015/KX580988) Strain in Infected Pigeons

2.7.1. Histopathology

In the non-vaccinated challenged group, in which the pigeons were oculonasaly inoculated with PPMV-1 at 9 weeks of age, tissue samples were collected from different organs (brain, trachea, lung, heart, liver, pancreas, spleen, proventriculus, intestine and kidneys) from the freshly dead and euthanized symptomatic pigeons. The collected tissues were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin before being embedded in paraffin and sectioned in duplicate to 3 µm thickness. For histopathology, slides were stained by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain and examined by a light microscope [

45].

2.7.2. Immunohistochemistry

To produce hyperimmune serum against PPMV-1, rabbits were given a series of injections in accordance with the schedule outlined by Samiullah

et al. [

46]. MagneProtein G Beads for Antibody Purification (Promega Corporation, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) were used to purify antibodies in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

Tissue sections were placed on slides coated with poly-L-lysine, which were then deparaffinized and rehydrated. Heat-induced antigen retrieval, blocking of nonspecific protein binding and endogenous peroxide application were performed. Tissue sections were incubated overnight with a monoclonal primary antibody (rabbit anti-PPMV-1 Ig), followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat polyclonal secondary antibody to rabbit Ig (SM802 EnVision

TM FLEX/HRP). Color was developed with a 3,3'-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate (DM827 EnVision

TM FLEX DAB þ chromogen) [

47]. Positive results appeared as a brown precipitate localized at the site of binding and were observed under an optical microscope. Negative tissue slides were established by adding negative serum instead of the primary antibody on non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b) tissue specimens and used as a reaction guide. Additionally, tissue specimens of non-vaccinated non-challenged pigeons (G4a) were incubated with the primary anti-PPMV-1 antibodies.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Several linear and generalized linear models were performed, and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was used to select the model with the best quality to fit the data. A generalized linear model (GLM) with a gamma distribution and log link function was employed to analyze hemagglutination inhibition (HI) titers as it had the lowest AIC. The HI titers are continuous, positively skewed data, and the gamma distribution is well-suited for modeling such data. The log link function ensures that predicted values remain positive on the original HI titer scale.

The generalized linear model gamma regression with log link function is used to assess the pattern of the HI titer change using two different antigens within five groups over the subsequent five weeks of the experiment. The probability function of the gamma distribution is as follows:

for

y (HI titre) > 0,

α > 0 (the shape parameter) and

β > 0 (the scale or the spread parameter), where E[

y] =

αβ and var[

y] =

αβ2. Note that

Γ () is the gamma function. The y variable is now changed to z as: y → z = exp{y} to receive the density of the log-gamma distributed random variable Z = exp{

Y} [

48].

The analysis was conducted in R (version 2023.06.1) using the “glm” function. Maximum likelihood estimation was used to fit the model. Goodness-of-fit was evaluated using chi-square tests and residual deviance. Estimated coefficients and their p-values were reported to assess the significance of predictor variables on the log-transformed mean change in HI titers. P value < 0.05 is considered a significant level. The model coefficients were exponentiated to provide insights into the actual effects of the predictors (antigen type, treatment groups, and weeks of experiment) on HI titer change.

4. Discussion

PPMV-1 is now a serious global hazard to bird populations, with pigeons being particularly vulnerable [

49,

50]. The strain "Pigeon/Egypt/Sharkia-19//2015/KX580988," previously isolated from a vaccinated native pigeon flock in Egypt, was classified as a velogenic strain that belonged to subgenotype VIb.2, class II. The study was designated to determine the virus pathotype characteristics in pigeons and chickens and to evaluate the protective efficacy of available commercial paramyxovirus vaccines against the velogenic strains of PPMV-1. [

35]. Based on the observed MDT value (86.4±5.88 in 10-day-old SPF-ECEs), ICPI value (0.8 ad 0.96 in 1-day-old SPF-chicks and 5-week-old pigeons respectively), and IVPI scores (insert relevant IVPI score), the Pigeon/Egypt/Sharkia-19//2015/KX580988 strain exhibits moderate virulence pathotype characteristics. Earlier reported studies displayed similar pathogenicity for PPMV-1 using MDT and ICPI in chicks [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56], although the poly-basic fusion protein in the cleavage site identified this strain as velogenic PPMV-1 [

32]. The majority of PPMV-1 strains are mesogenic or lentogenic for chickens, according to ICPI and MDT tests, even though they have been demonstrated to have deduced amino acid motifs, suggesting high pathogenicity [

25,

57]. These imply that other factors affect the pathogenic phenotype of these viruses and that the cleavage site is not the only factor regulating PPMV-1's pathogenicity in various species [

26,

35]. According to WOAH standards, the ICPI of the strain used in present study belongs to the virulent or velogenic category [

39]. Notably, the ICPI (0.96) was relatively high in pigeons, with more pigeons showing nervous signs (n = 4/10) and mortalities (n = 6/10) than chicks. Considering that pigeons are the natural host of the PPMV-1, it may not be suitable for its assessment to be carried out in chickens only [

37]. However, when the PPMV-1 strain was tested for pathogenicity and clinical symptoms after successive passages in chickens, it became more virulent [

1,

13,

26]. This pilot study and others [

37] concluded that in order to evaluate the real virulence of PPMV-1, pigeons should be employed for pathogenicity testing.

It is interesting to note that the IVPI value suggested the PPMV-1 was velogenic with a score of 2.11 in pigeons, accompanied by mortality (n = 10/10) within 7 days post-inoculation. The different degrees of virus pathogenicity in pigeons relate to different inoculation routes. In the intravenous route, the virus enters the bloodstream immediately and subsequently spreads to different organs at a faster rate [

58]. This systemic route of virus inoculation is the cause of the nervous involvement [

59], and high mortality that reaches 100%. According to the results of the bioassays used in this prospective study, the PPMV-1 strain used in the present study showed pathogenicity in both chicks and pigeons.

Considering the increase in PPMV-1 infections in recent years, disease prevention is required. Effective vaccinations or other preventative and control measures need to be developed and applied in pigeon lofts to reduce losses and the risk of disease transmission to other birds [

60]. The commercial vaccines usually used in most countries to control variant paramyxovirus-1 (PPMV-1) are classical paramyxovirus-1 and chicken NDV-live or inactivated vaccines [

34]. In contrast to most other countries, Egypt provides commercially accessible inactivated pigeon paramyxovirus (PPMV) in addition to the conventional NDV vaccines. The available commercial paramyxovirus vaccines under investigation in this study were the live attenuated NDV vaccine (LaSota) and the formalized inactivated pigeon paramyxovirus (PPMV).

To complete the understanding of PPMV-1 pathogenicity and identify the markers of its natural pathologic pathway, the pigeons infected via the pigeons oculonasal route were thoroughly investigated. Clinical findings and morbidity and mortality rates were recorded daily. Histopathology examination was used to document the microscopic lesions in the various tissue organs. Additionally, immunohistochemistry (IHC) was used to determine the gene expression of the viral strain and confirm that the lesions were the result of PPMV-1 infection.

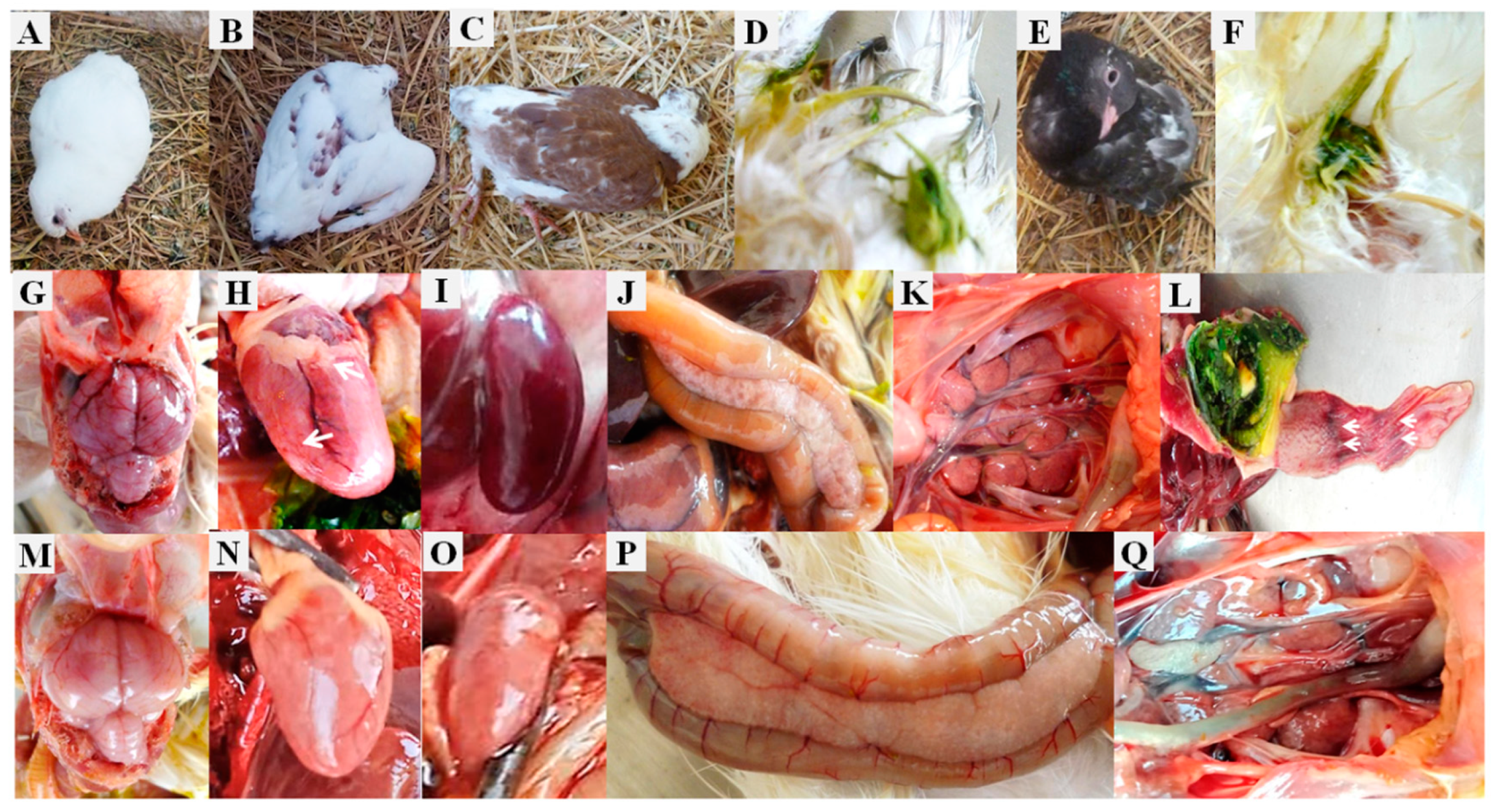

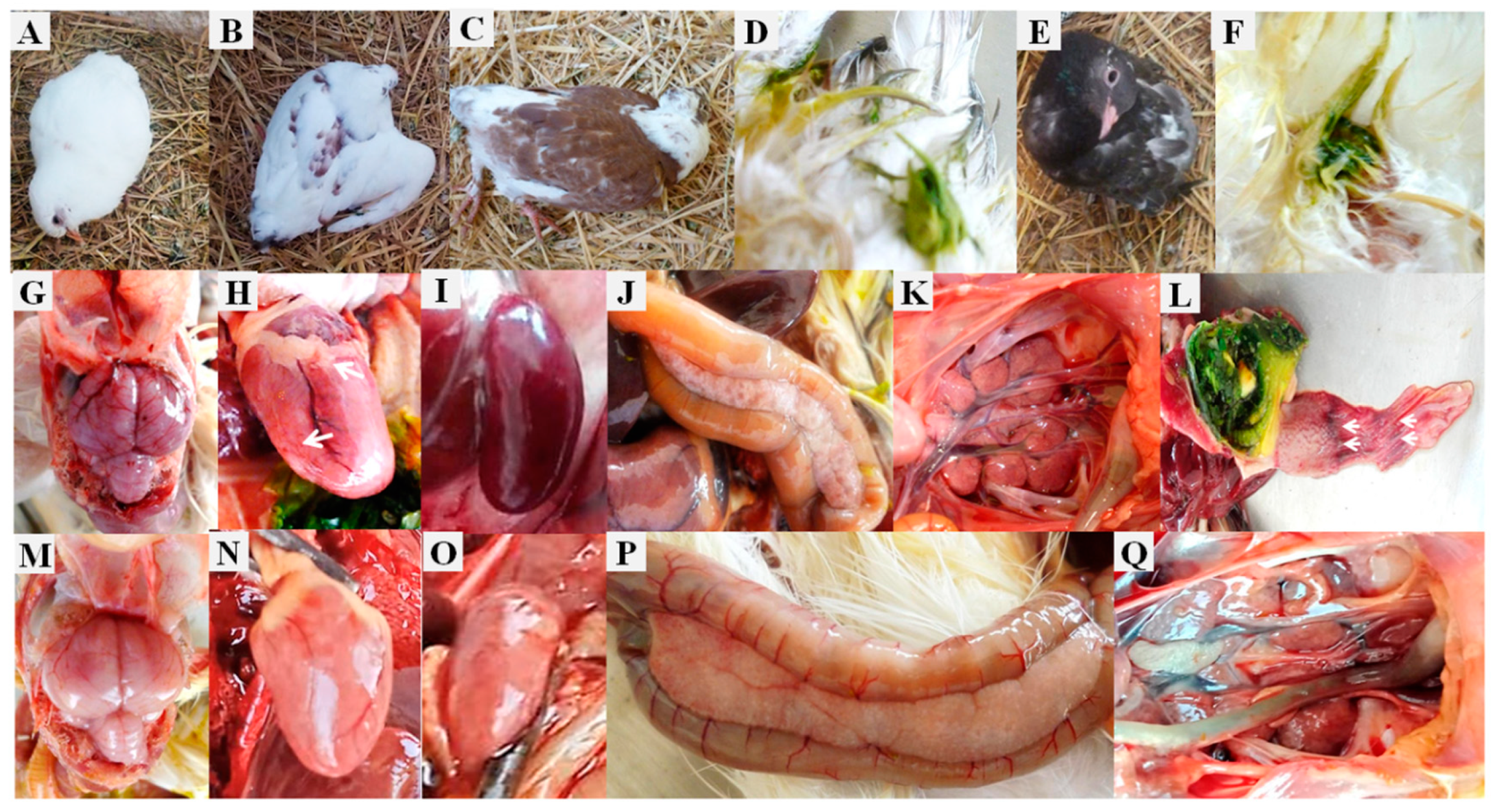

Consistent with previous studies [

53,

55,

56,

61], the non-vaccinated challenged pigeons exhibited typical clinical signs and gross lesions. It is important to note that the nervous signs and greenish diarrhea were the common signs as documented by Śmietanka

et al. [

1], Zhan

et al. [

55], Shalaby

et al. [

62], and were accompanied by lesions recorded in the brain and digestive tract of 100% of pigeons. Primarily through the pattern of noticed signs and lesions, it is expected that this PPMV-1 strain has neurotropic and viscerotropic potentiality. Moreover, Chang

et al. [

53] have concluded that virus titer was higher in the brain, intestine, and lung than in other tissues.

The signs in the current study started at 5 dpi, as previously recorded by Xie

et al. [

36] and Chang

et al. [

53]. However, other studies showed signs as early as 2-4 dpi [

55,

56,

61]. This variation in the incubation period depends on the virus’s properties, the dose in the inoculum, and host features such as age, breed, and immune response [

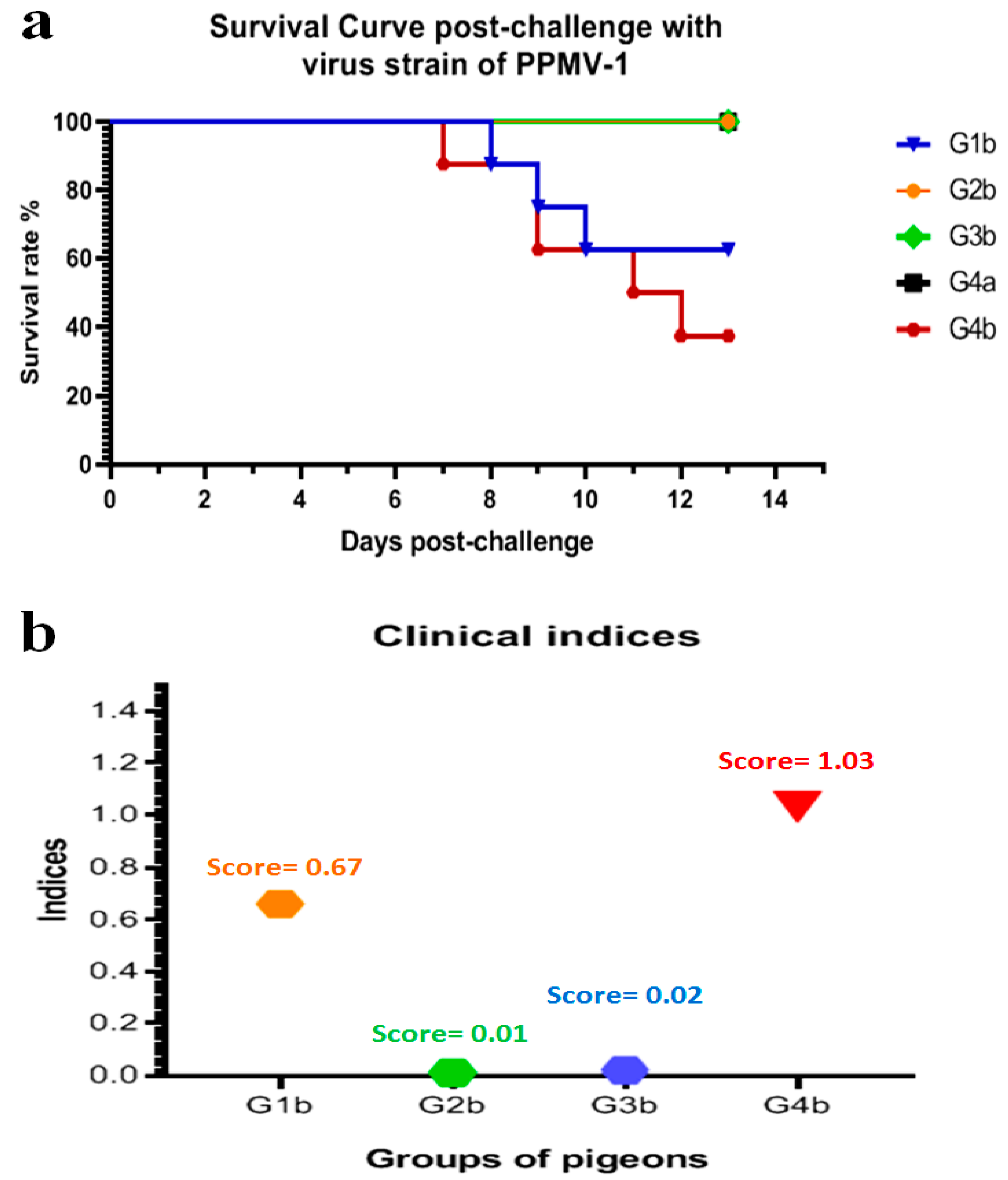

1]. Additionally, the clinical score recorded by the infected pigeons reached 1.03, and the morbidity and mortality rates were 100% and 62.5%, respectively, factoring in birds that died or reached the humane endpoint within 2 days of the onset of clinical signs.

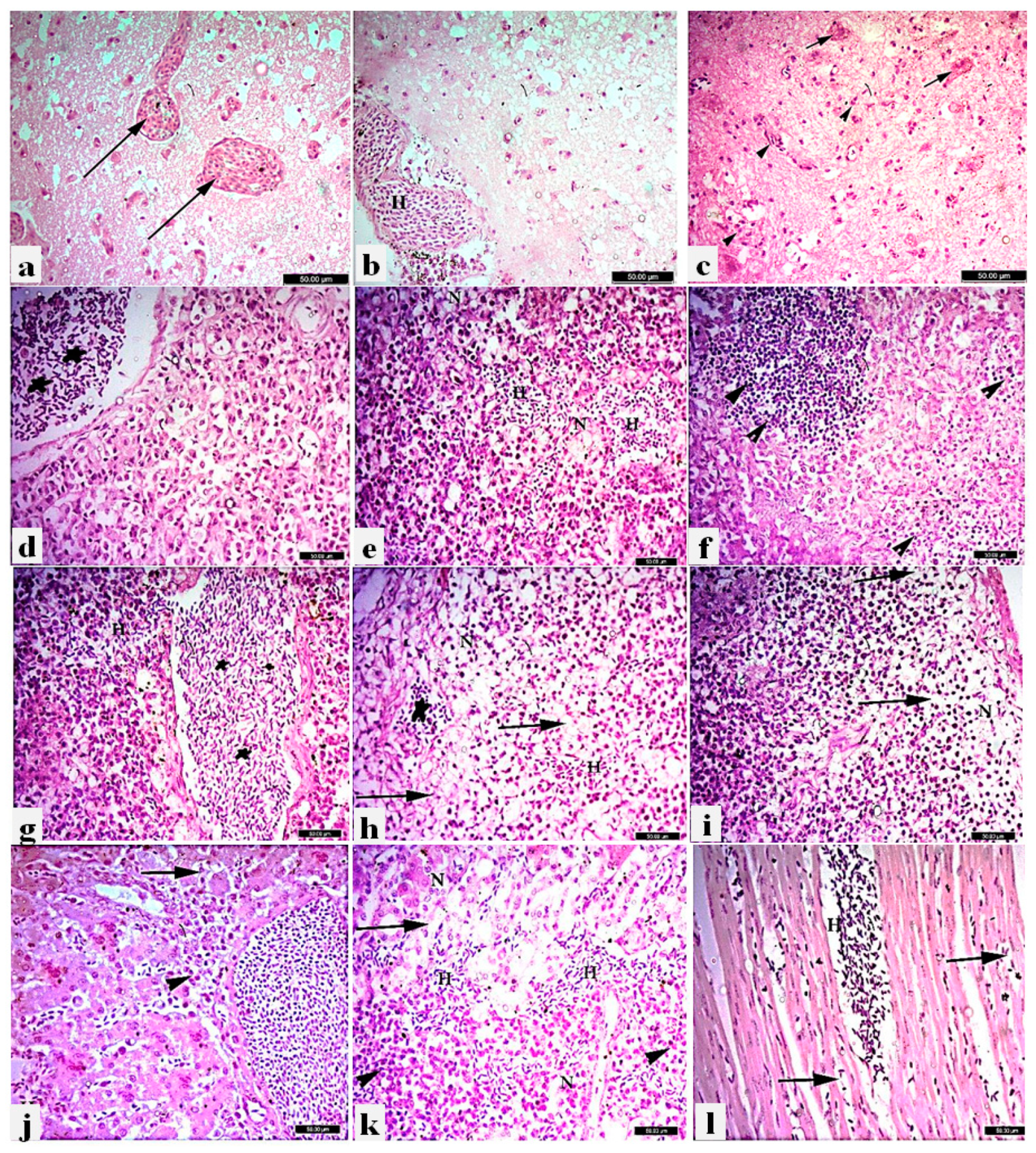

The microscopic lesions observed in multiple organs of PPMV-1 infected pigeons were similar to those noted in previous reports [

37,

61,

62,

63,

64]. This in-depth microscopic examination of the infected organs revealed the extent of virus dissemination and the direct damage it causes, negatively impacting the birds' health and contributing to morbidity and mortality. Among the common gross lesions and microscopic changes that caught our attention were in the brain, informing sub-meningeal and focal cortical hemorrhages, multifocal degeneration, and swelling of neurons with focal gliosis. The involvement of the central nervous system (CNS) in PPMV-1 disease was prevalent, particularly given the neurologic clinical signs often observed. This indicates the tropism of the PPMV-1 strain for the nervous tissues. Necrotizing pancreatitis was most often observed in pigeons and is considered an acute change which might cause animal death due to systemic inflammatory response syndrome and multi-organic failure as a result of releasing activated proteolytic enzymes and pro-inflammatory cytokines into the bloodstream [

65]. Tubulointerstitial nephritis was observed which could contribute to the loss of homeostasis. Only a few studies had reliable confirmation of lymphocytosis [

63]. On the other hand, notable alterations in lymphoid organs have not always been described in PPMV-1 outbreaks [

66,

67]. In the present study, lymphoid depletion of the spleen's white pulp was recorded in the presence of viral antigen expression in the IHC, which suggests that PPMV-1 may cause lymphoid depletion. Although IHC analysis has been adopted a few times in prior studies [

62,

63], it confirmed incrimination of PPMV-1 responsibility for changes in the collected tissue organs by detecting a strong PPMV-1 antigen expression. This suggests that the use of IHC to detect PPMV-1 infections in tissues could be a potential tool to trace the viral pathway in tissues and confirm its lesions.

PPMV-1 was able to cause systemic infection, which had a wide range of tissue distribution in pigeons, along with the prominent neurological and intestinal symptoms, and was broadly consistent with pronounced lesions in these organs. This suggests that PPMV-1 is a systemic virus with neuro- and viscero-tropism.

All the vaccinated groups had a lower severity and frequency of the signs of disease compared to the non-vaccinated pigeons. Importantly, the pigeons were more protected against the PPMV-1 challenge by both programs of the inactivated PPMV vaccine and LaSota with PPMV, which inhibited the appearance of clinical symptoms. The clinical scores for both vaccination programs were 0.01 and 0.02, respectively, and their corresponding morbidity rates were 12.5%. On the other hand, the LaSota vaccination had the lower protection rate, which the clinical score was 0.67 and a 62.5% morbidity rate. Both vaccine programs containing inactivated PPMV protected 100% of pigeons against mortality, while the LaSota vaccine was 62.5%. This indicated that the inactivated PPMV vaccine provided good protection. Similar observations were reported by Zhang

et al. [

37], Amer

et al. [

60], Stone [

68], Hassan, [

69], who conducted their investigation on the inactivated PPMV vaccine either locally commercial [

60,

69] or prepared from an isolated strain [

37,

68] and ND(V?) vaccines against PPMV-1 challenge in pigeons. They recommended that the homologous vaccine is more efficacious than the ND(V?) vaccines such as Ulster, LaSota, and Hitchner B1. And the protection rate reached 100% against morbidity and mortality.

It is well known that antibodies against viruses protect the host from damage caused by the virus [

70,

71]. Comparing the immune efficacies in the vaccinated groups using the HI test, the vaccination containing inactivated PPMV whether alone or with LaSota developed significant high antibody levels in pigeons from 3 weeks post-vaccination (initial PPMV-1 challenge) than in the LaSota vaccine alone. Antibody level also increased over time post-challenge. This suggests that the PPMV-1-matched vaccine could induce elevated humoral response. This finding mirrors the results of Zhang

et al. [

37].

Using either LaSota or PPMV-1 as diagnostic antigens against HI antibodies of PPMV-1 showed similar inhibition. This could be attributed to the use of polyclonal antibodies rather than monoclonal ones since only monoclonal antibodies prepared against the PPMV-1 variant virus can inhibit all PPMV-1 isolates in HI test but no other NDV strains [

72]. Monoclonal specific epitopes on the F polypeptide induce greater neutralization than those against HN in vitro and in vivo tests [

73].

Likewise, the two vaccination programs containing inactivated PPMV resulted in no pigeons shedding virus. In contrast, the LaSota vaccine did not prevent virus shedding from the cloaca or orally, which was detectable from the fifth day post-challenge, although it decreased the number of birds that shed the virus in comparison with non-vaccinated pigeons.

A notable problem of this disease is the virus shedding from the infected pigeons [

51,

53]. The main risk from the virus is its ability to transmit from infected birds to other bird populations (wild or domesticated) and evolutionary changes which potentially increases its virulence phenotype. So, protection against virus shedding is considered one of the important priorities for evaluating the success of vaccination programs. In this study, LaSota vaccine provided insufficient protection against morbidity, mortality, virus shedding with low antibody level pre- and post-challenge. Previous studies detected that the ND-derived strain vaccines were inadequate for the protection of pigeons against PPMV-1, such as LaSota vaccine [

37,

74] and Hitchner B1 vaccine [

60]. Additionally, confirmed by field practices, it is shown that despite the use of LaSota vaccine in pigeons, the disease outbreaks continue [

19,

35], and this is the case in the pigeons from which the strain under study was obtained. This is attributed to the presence of biological, serological, and genetic differences between the prevalence both the NDV and the PPMV-1 strain [

34,

37,

51,

75] even if it was minor [

35]. The known transmitted NDV strains have undertaken major shifts in their genotypes over the past few decades, although they still belong to a single serotype [

70].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.M.E. and M.I.; methodology, A.A.M.E., R.M.E., E.E.H., H.F.G., A.A.D., and A.H.E..; formal analysis, H.F.G., A.A.M.E., and R.M.E.; investigation, A.A.M.E., R.M.E., and E.E.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.M.E., R.M.E., E.E.H., and H.F.G.; writing—review and editing, A.A.M.E., M.I., and R.M.E.; visualization, A.A.M.E., R.M.E., E.E.H., H.F.G., A.A.D., A.H.E., and M.I.; project administration, A.A.M.E., and M.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Summary of experimental design: A) Design of biological characterization. B) Design of vaccines assessment against challenged with field strain of PPMV-1 "Pigeon/Egypt/ Sharkia-19/2015/KX580988". G1a, G2a, G3a, and G4a were kept as control groups to monitor any natural infection exposure from the environment to these pigeons. G1b, G2b, G3b, and G4b were challenged with PPMV-1 strain.

Figure 1.

Summary of experimental design: A) Design of biological characterization. B) Design of vaccines assessment against challenged with field strain of PPMV-1 "Pigeon/Egypt/ Sharkia-19/2015/KX580988". G1a, G2a, G3a, and G4a were kept as control groups to monitor any natural infection exposure from the environment to these pigeons. G1b, G2b, G3b, and G4b were challenged with PPMV-1 strain.

Figure 2.

Virulence (ICPI, and IVPI) assessment of the PPMV-1 strain (Pigeon/ Egypt/Sharkia-19/2015/KX580988) in pigeons and chickens. The birds were inoculated via intracerebral (I/C) and intravenous (I/V) routes to 1-day-old chicks and 5-week-old pigeons. The clinical scores were recorded until 10 days post infection (dpi). The clinical scores are represented as healthy (green color), displaying variable clinical signs, such as ruffled feather, depression, anorexia, and greenish diarrhea (light blue color, except nervous signs with (dark blue color)), and dead (red color).

Figure 2.

Virulence (ICPI, and IVPI) assessment of the PPMV-1 strain (Pigeon/ Egypt/Sharkia-19/2015/KX580988) in pigeons and chickens. The birds were inoculated via intracerebral (I/C) and intravenous (I/V) routes to 1-day-old chicks and 5-week-old pigeons. The clinical scores were recorded until 10 days post infection (dpi). The clinical scores are represented as healthy (green color), displaying variable clinical signs, such as ruffled feather, depression, anorexia, and greenish diarrhea (light blue color, except nervous signs with (dark blue color)), and dead (red color).

Figure 3.

Survival rates and clinical indices. a) Survival curves of vaccinated pigeons with tested vaccines post-challenge. b) Clinical indices of vaccinated pigeons with tested vaccines post-challenge. G1b: vaccinated with NDV LaSota and challenged, G2b: vaccinated with PPMV and challenged, G3b: dual vaccinated with LaSota and PPMV and challenged, G4a: non-vaccinated non-challenged, G4b: non-vaccinated challenged.

Figure 3.

Survival rates and clinical indices. a) Survival curves of vaccinated pigeons with tested vaccines post-challenge. b) Clinical indices of vaccinated pigeons with tested vaccines post-challenge. G1b: vaccinated with NDV LaSota and challenged, G2b: vaccinated with PPMV and challenged, G3b: dual vaccinated with LaSota and PPMV and challenged, G4a: non-vaccinated non-challenged, G4b: non-vaccinated challenged.

Figure 4.

Clinical and post-mortem findings of pigeons infected/challenged with PPMV-1 strain. A) Torticollis in non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b). B) Wing paralysis in non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b). C) Complete paralysis in non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b). D) Severe greenish diarrhea in non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b). E) Opisthotonus position in pigeon of NDV LaSota group (G1b). F) Greenish diarrhea in pigeon of NDV LaSota group (G1b). G) Severe congested and hemorrhagic brain in non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b). H) Congested heart with minute petechial hemorrhages in non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b). I) Enlarged and severe congested spleen with hemorrhages in non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b). J) Pancreatitis with punctate hemorrhages in non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b). K) Severe nephrosis in non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b). L) Hemorrhages at junction between esophagus and proventriculus with greenish content in the gizzard of non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b). M) Moderate congestion in brain of pigeon in NDV LaSota group (G1b). N) Mild congestion (apparently normal) of heart in pigeon of NDV LaSota group (G1b). O) Enlarged spleen with few hemorrhages in pigeon of NDV LaSota group (G1b). P) Pancreatitis with necrosis in pigeon of NDV LaSota group (G1b). Q) Moderate nephrosis in pigeon of NDV LaSota group (G1b).

Figure 4.

Clinical and post-mortem findings of pigeons infected/challenged with PPMV-1 strain. A) Torticollis in non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b). B) Wing paralysis in non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b). C) Complete paralysis in non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b). D) Severe greenish diarrhea in non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b). E) Opisthotonus position in pigeon of NDV LaSota group (G1b). F) Greenish diarrhea in pigeon of NDV LaSota group (G1b). G) Severe congested and hemorrhagic brain in non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b). H) Congested heart with minute petechial hemorrhages in non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b). I) Enlarged and severe congested spleen with hemorrhages in non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b). J) Pancreatitis with punctate hemorrhages in non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b). K) Severe nephrosis in non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b). L) Hemorrhages at junction between esophagus and proventriculus with greenish content in the gizzard of non-vaccinated challenged pigeon (G4b). M) Moderate congestion in brain of pigeon in NDV LaSota group (G1b). N) Mild congestion (apparently normal) of heart in pigeon of NDV LaSota group (G1b). O) Enlarged spleen with few hemorrhages in pigeon of NDV LaSota group (G1b). P) Pancreatitis with necrosis in pigeon of NDV LaSota group (G1b). Q) Moderate nephrosis in pigeon of NDV LaSota group (G1b).

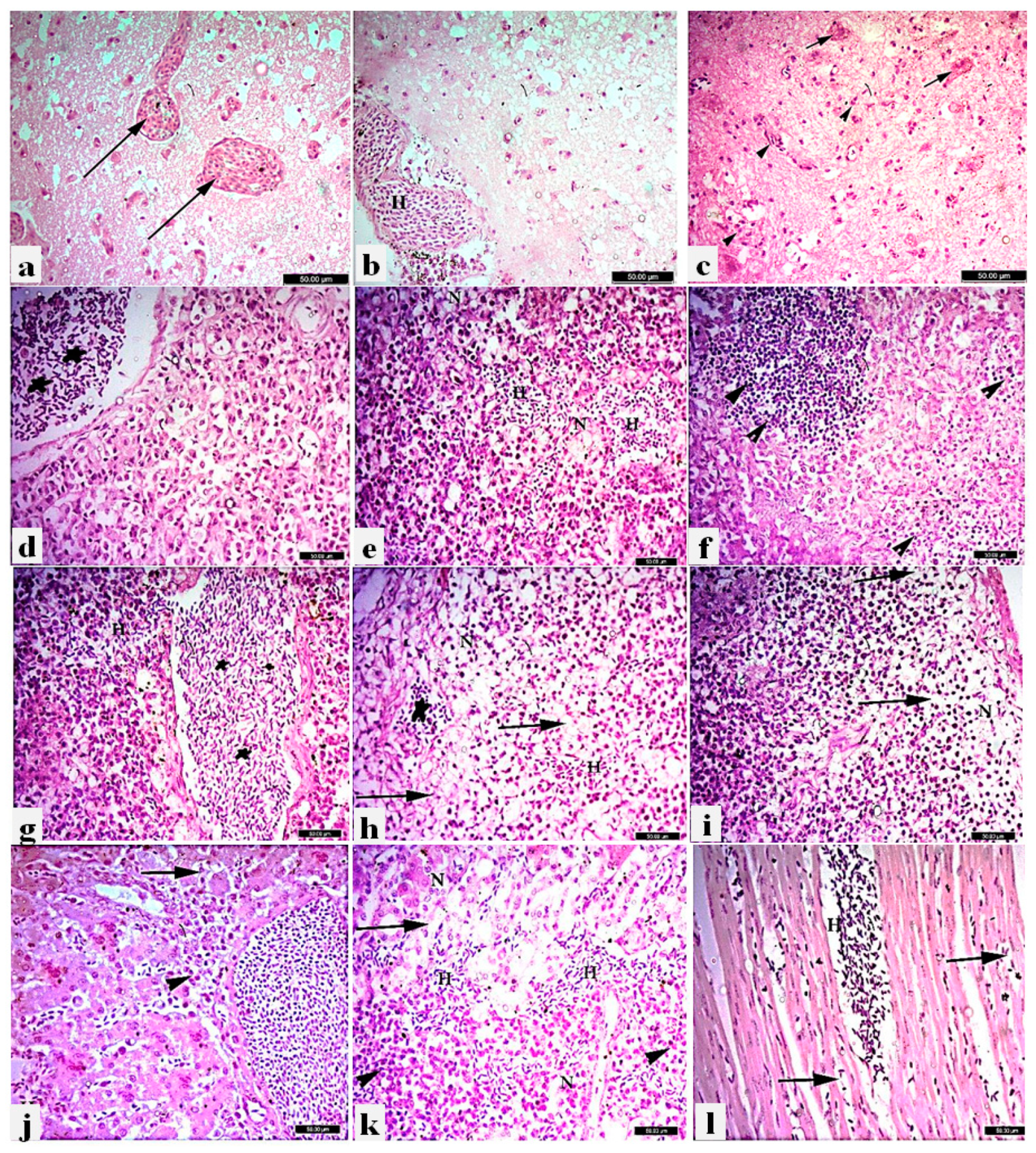

Figure 5.

Histopathological lesions in different tissue organs of nin-vaccinated infected pigeons with PPMV-1 strain, H&E X400, Bar 50um. Brain: a) Congestion of brain capillaries (long arrows). b) Sub meningeal hemorrhages (H). c) Multifocal degeneration and swelling of neurons gliosis (arrow heads), degenerated neurons (short arrows). Pancreas: d) Severe congestion (stars). e) Multifocal hemorrhages (H) with degeneration and necrosis of pancreatic acini (N). f) Multifocal aggregations of lymphocytic infiltrations (arrow head). Spleen: g) Severe congestion of sinusoids and splenic blood vessels (stars). h) Multifocal hemorrhages (H), severe depletion of subcapsular lymphoid follicles (long arrows). i) Severe depletion of subcapsular lymphoid follicles (long arrows). j) Liver; severe congestion, focal degeneration (long arrow) and discrete necrosis of some hepatic cells, along with mild leukocytes around bile duct (arrow head). k) Kidney; intertubular hemorrhages (H), degeneration of renal tubular epithelium (long arrow) and focal necrosis (N) with leukocyte infiltration (arrow head). l) Heart; Inter-muscular congestion (long arrows), and hemorrhages (H).

Figure 5.

Histopathological lesions in different tissue organs of nin-vaccinated infected pigeons with PPMV-1 strain, H&E X400, Bar 50um. Brain: a) Congestion of brain capillaries (long arrows). b) Sub meningeal hemorrhages (H). c) Multifocal degeneration and swelling of neurons gliosis (arrow heads), degenerated neurons (short arrows). Pancreas: d) Severe congestion (stars). e) Multifocal hemorrhages (H) with degeneration and necrosis of pancreatic acini (N). f) Multifocal aggregations of lymphocytic infiltrations (arrow head). Spleen: g) Severe congestion of sinusoids and splenic blood vessels (stars). h) Multifocal hemorrhages (H), severe depletion of subcapsular lymphoid follicles (long arrows). i) Severe depletion of subcapsular lymphoid follicles (long arrows). j) Liver; severe congestion, focal degeneration (long arrow) and discrete necrosis of some hepatic cells, along with mild leukocytes around bile duct (arrow head). k) Kidney; intertubular hemorrhages (H), degeneration of renal tubular epithelium (long arrow) and focal necrosis (N) with leukocyte infiltration (arrow head). l) Heart; Inter-muscular congestion (long arrows), and hemorrhages (H).

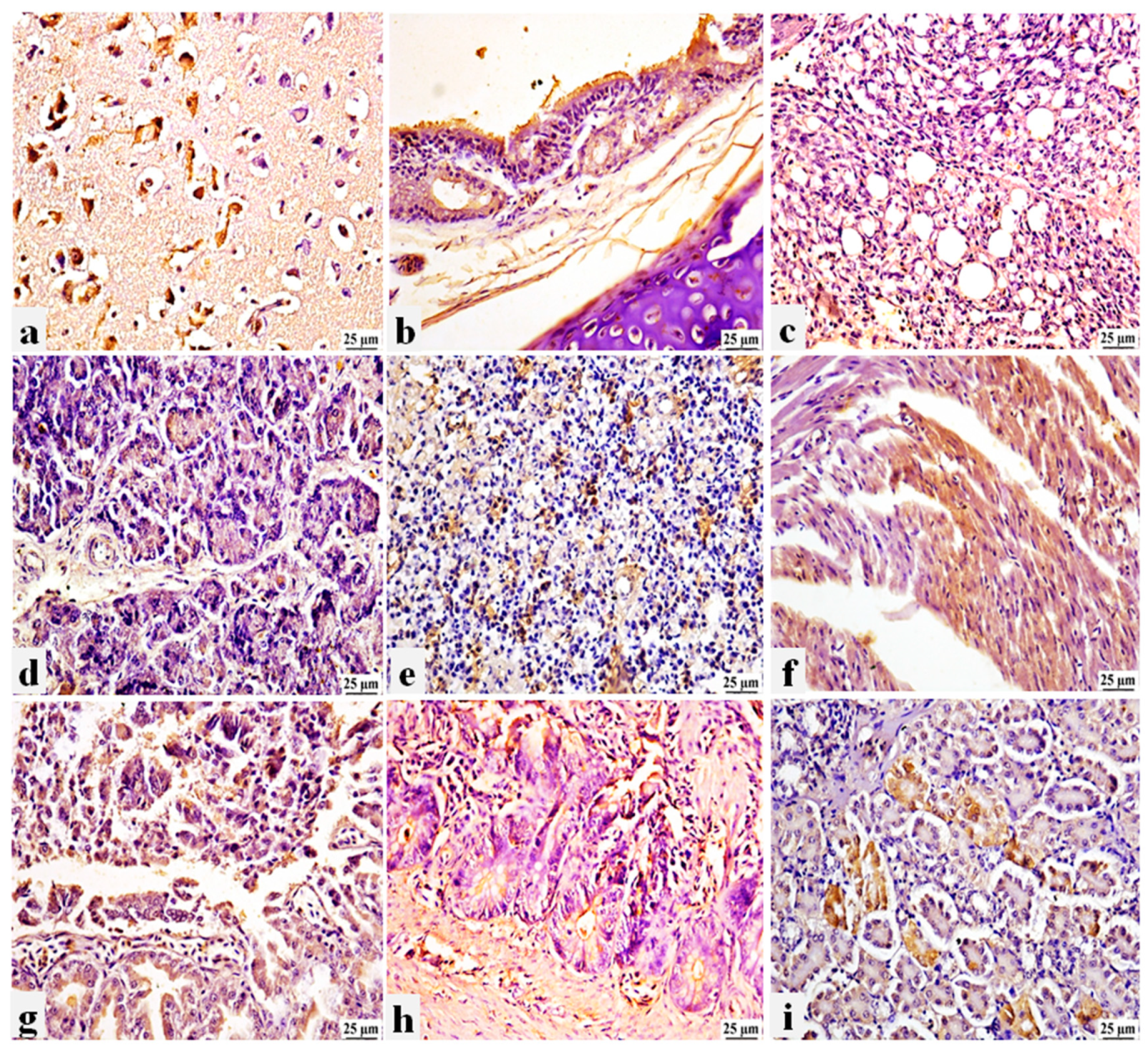

Figure 6.

Photomicrograph of immunohistochemistry (IHC) in different tissue organs of non-vaccinated and infected pigeons with PPMV-1 strain, Bar 25um. a) Brain showing positive expression of viral antigen in the degenerated neurons. b) Trachea showing positive expression of viral antigen in the tracheal epithelium and in the inflammatory cells in the propria submucosa. c) Lung showing positive expression of viral antigen in air capillaries. d) Pancreas showing positive expression of viral antigen in the exocrine epithelial cells. e) Spleen showing positive expression of viral antigen in the splenic parenchyma. f) Heart showing positive expression of viral antigen in the cardiac muscle. g) Proventriculus showing positive expression of viral antigen in the glandular epithelium and desquamated epithelial cells. h) Intestine showing positive expression of intestinal mucosa. i) Kidney showing positive expression of viral antigen in the renal tubular epithelium.

Figure 6.

Photomicrograph of immunohistochemistry (IHC) in different tissue organs of non-vaccinated and infected pigeons with PPMV-1 strain, Bar 25um. a) Brain showing positive expression of viral antigen in the degenerated neurons. b) Trachea showing positive expression of viral antigen in the tracheal epithelium and in the inflammatory cells in the propria submucosa. c) Lung showing positive expression of viral antigen in air capillaries. d) Pancreas showing positive expression of viral antigen in the exocrine epithelial cells. e) Spleen showing positive expression of viral antigen in the splenic parenchyma. f) Heart showing positive expression of viral antigen in the cardiac muscle. g) Proventriculus showing positive expression of viral antigen in the glandular epithelium and desquamated epithelial cells. h) Intestine showing positive expression of intestinal mucosa. i) Kidney showing positive expression of viral antigen in the renal tubular epithelium.

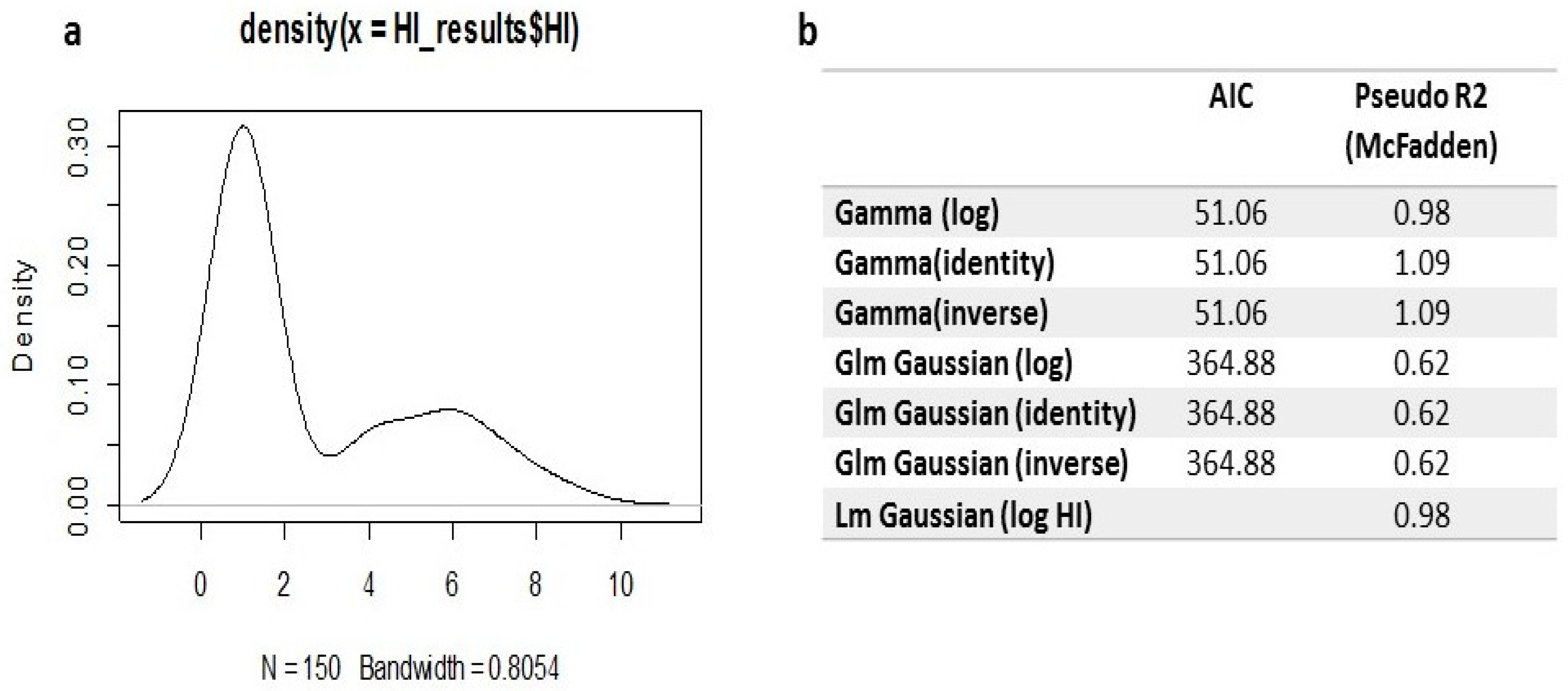

Figure 7.

a) Density plot showing the positive skewness in the HI titer distribution. b) Model selection criteria for linear and generalized linear designs based on Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

Figure 7.

a) Density plot showing the positive skewness in the HI titer distribution. b) Model selection criteria for linear and generalized linear designs based on Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

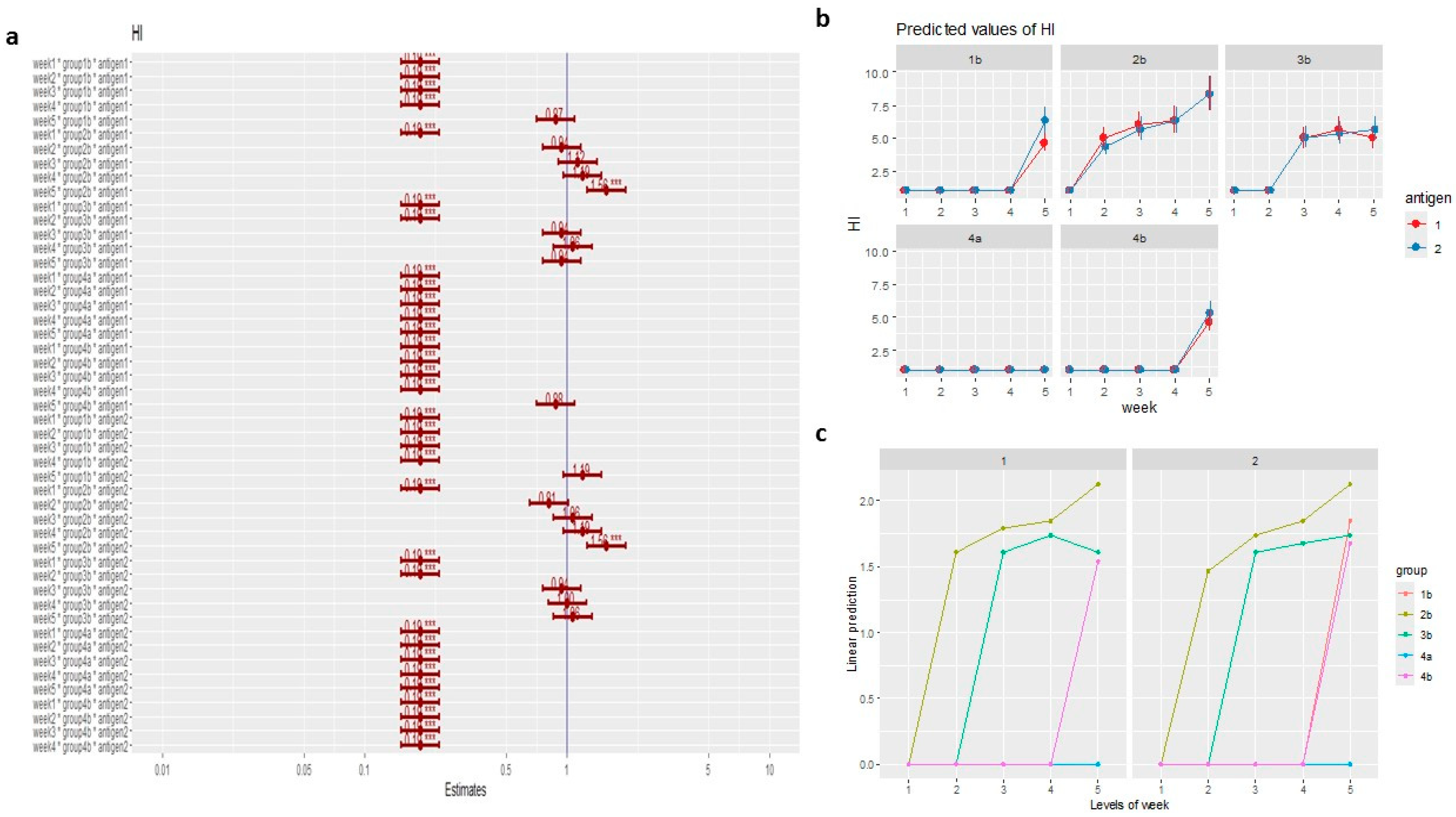

Figure 8.

a) The GLM model estimates with 95% confidence interval; *** representing the significance of the model coefficient estimates. b) Predicted values of the GLM for HI titers to detect the difference between using LaSota as heterologous antigen (antigen 1) and PPMV-1 as homologous antigen (antigen 2) within the 5 groups. c) Predicted values of the GLM for HI titers to detect the difference between the 5 groups within NDV LaSota (antigen 1) and PPMV-1 (antigen 2) at consecutive 5 weeks.

Figure 8.

a) The GLM model estimates with 95% confidence interval; *** representing the significance of the model coefficient estimates. b) Predicted values of the GLM for HI titers to detect the difference between using LaSota as heterologous antigen (antigen 1) and PPMV-1 as homologous antigen (antigen 2) within the 5 groups. c) Predicted values of the GLM for HI titers to detect the difference between the 5 groups within NDV LaSota (antigen 1) and PPMV-1 (antigen 2) at consecutive 5 weeks.

Table 1.

General and specific clinical signs, morbidities and mortalities of differentially PPMV-1 virus−vaccinated groups 14 days post-challenge, with clarification of the healthy condition in the vaccinated-non-challenged groups.

Table 1.

General and specific clinical signs, morbidities and mortalities of differentially PPMV-1 virus−vaccinated groups 14 days post-challenge, with clarification of the healthy condition in the vaccinated-non-challenged groups.

| Groups |

Subgroups |

General signs * |

Respiratory Signs |

Greenish diarrhea |

Nervous signs |

Morbidity number (%) |

Clinical indices ** |

Mortality number (%) |

| G1 |

A |

0/8 |

0/8 |

0/8 |

0/8 |

0/8 (0) |

0 |

0/8 (0) |

| B |

5/8 |

0/8 |

2/8 |

2/8 |

5/8 (62.5) |

0.66 |

3/8 (37.5) |

| G2 |

A |

0/8 |

0/8 |

0/8 |

0/8 |

0/8 (0) |

0 |

0/8 (0) |

| B |

1/8 |

0/8 |

1/8 |

0/8 |

1/8 (12.5) |

0.01 |

0/8 (0) |

| G3 |

A |

0/8 |

0/8 |

0/8 |

0/8 |

0/8 (0) |

0 |

0/8 (0) |

| B |

1/8 |

0/8 |

0/8 |

1/8 |

1/8 (12.5) |

0.02 |

0/8 (0) |

| G4 |

A |

0/8 |

0/8 |

0/8 |

0/8 |

0/8 (0) |

0 |

0/8 (0) |

| B |

8/8 |

1/8 |

5/8 |

6/8 |

8/8 (100) |

1.03 |

5/8 (62.5) |

Table 2.

Pathological lesions among the dead and sacrificed morbid pigeons of differentially PPMV-1 virus−vaccinated groups post-challenge with unvaccinated challenged group.

Table 2.

Pathological lesions among the dead and sacrificed morbid pigeons of differentially PPMV-1 virus−vaccinated groups post-challenge with unvaccinated challenged group.

| Sub-groups |

Total No. |

No. of dead and euthanized morbid pigeons |

Congested/ hemorrhagic brain |

Enlarged/ atrophied spleen |

Pancreas with hemorrhages/ necrosis |

Hemorrhages on heart |

Hemorrhages between esophagus and proventriculus |

Enteritis with greenish content |

Kidneys |

Atrophy thymus |

Atrophy of Bursa of fabricius |

| G1b |

8 |

5 |

4

Congested |

3 |

3

(1 hemorrhagic, 2 necrosis) |

0 |

1 |

3 |

3

(1 nephritis, 2 nephrosis) |

3 |

3 |

| G2b |

8 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1

Necrosis |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| G3b |

8 |

1 |

1

Congested |

0 |

1

Necrosis |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1

nephrosis |

0 |

0 |

| G4b |

8 |

8 |

8

congested and hemorrhagic |

5 |

8

(6 hemorrhagic, 2 necrosis) |

2 |

2 |

8 |

7

(2 nephritis, 5 nephrosis) |

5 |

4 |

Table 3.

Estimated marginal means ± SEM for the HI titer values over 5 weeks for 5 groups with 2 antigens.

Table 3.

Estimated marginal means ± SEM for the HI titer values over 5 weeks for 5 groups with 2 antigens.

| Antigen |

Groups |

Weeks post-vaccination |

| Week1 |

Week2 |

Week3 |

Week4 |

Week5 |

| LaSota |

1b |

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

4.67±0.37 b

|

| 2b |

1±0.08 c

|

5±0.39 b

|

6±0.47 ab |

6.33±0.49ab

|

8.33±0.66 a

|

| 3b |

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

5±0.39b |

5.67±0.45 ab

|

5±0.39 b

|

| 4a |

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

| 4b |

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

4.67±0.37 b

|

| PPMV-1 |

1b |

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

6.33±0.49 ab

|

| 2b |

1±0.08 c

|

4.33±0.34 b

|

5.67±0.45 ab |

6.33±0.49ab

|

8.33±0.66 a

|

| 3b |

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

5±0.39b |

5.33±0.42 ab

|

5.67±0.45 ab

|

| 4a |

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

| 4b |

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

1±0.08 c

|

5.33±0.42 b

|

Table 4.

Detection of viral shedding from collected swabs after the challenge of vaccinated and unvaccinated pigeons with the PPMV-1 isolate at 3, 5, and 7 days post challenge (dpc) and estimated by quantitative real-time-PCR (RT-qPCR).

Table 4.

Detection of viral shedding from collected swabs after the challenge of vaccinated and unvaccinated pigeons with the PPMV-1 isolate at 3, 5, and 7 days post challenge (dpc) and estimated by quantitative real-time-PCR (RT-qPCR).

| Groups |

Tracheal swab |

Cloacal swab |

| 3dpc |

5dpc |

7dpc |

3dpc |

5dpc |

7dpc |

| No of swabs *

|

Ct value **

|

No of swabs |

Ct value |

No of swabs |

CT value |

No of swabs |

Ct value |

No of swabs |

Ct value |

No of swabs |

Ct value |

|

G1b; LaSota-challenged |

0/3 |

- |

1/3 |

37.6 |

1/3 |

30.9 |

0/3 |

- |

2/3 |

32.6-34.9 |

1/3 |

28.4 |

|

G2b; PPMV-challenged |

0/3 |

- |

0/3 |

- |

0/3 |

- |

0/3 |

- |

0/3 |

- |

0/3 |

- |

|

G3b; LaSota &PPMV-challenged |

0/3 |

- |

0/3 |

- |

1/3 |

39.3***

|

0/3 |

- |

0/3 |

- |

1/3 |

37 |

|

G4b; unvaccinated challenged |

0/3 |

- |

1/3 |

37.3 |

3/3 |

35-36 |

0/3 |

- |

3/3 |

32.8-33.9 |

3/3 |

33.9-35.4 |