Submitted:

29 September 2024

Posted:

01 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

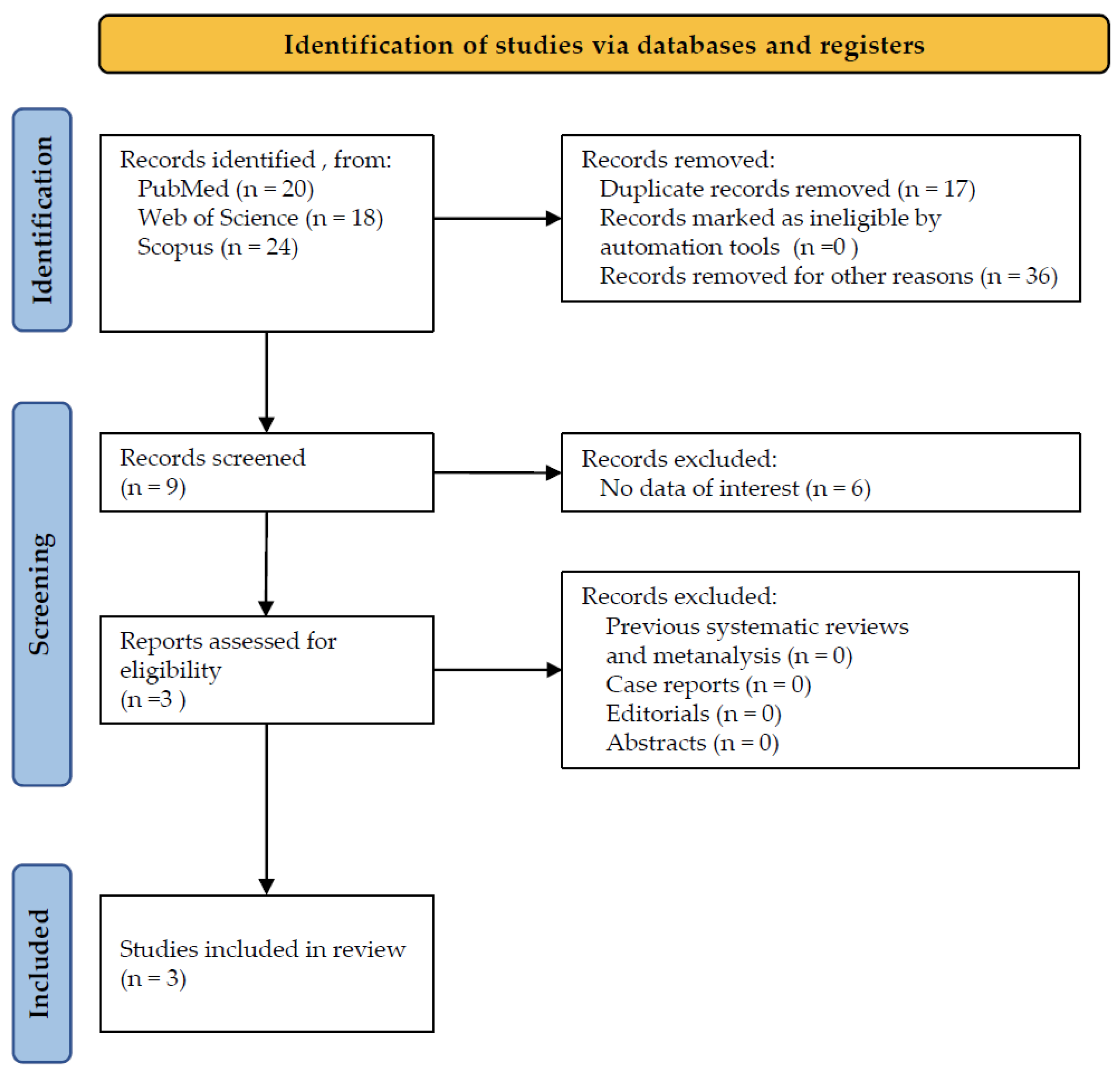

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Detailed Results

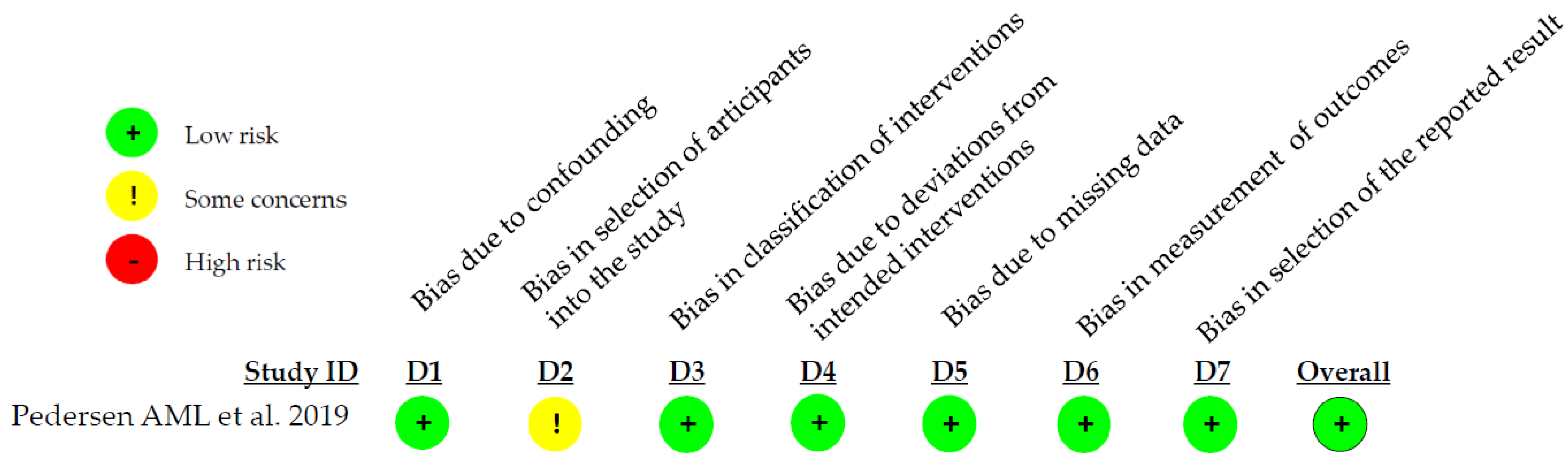

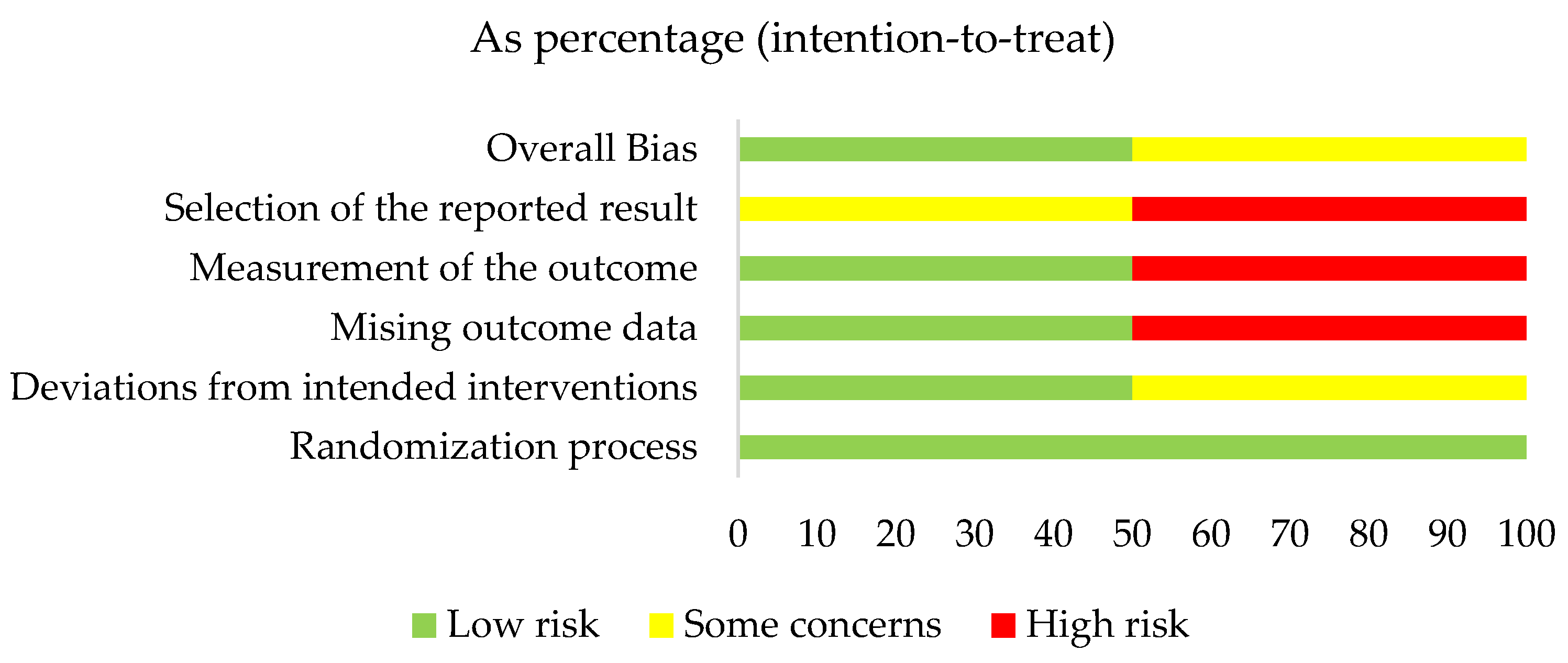

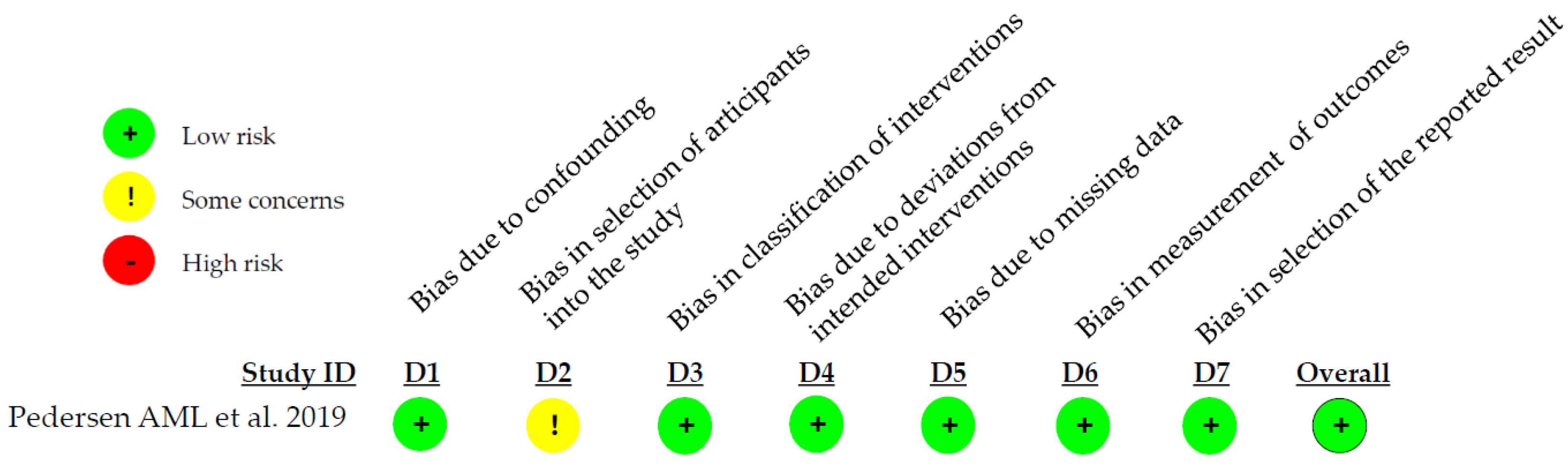

3.3. Quality Assessment Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

Clinical Relevance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams SE, Arnold D, Murphy B, Carroll P, Green AK, Smith AM, Marsh PD, Chen T, Marriott RE, Brading MG. A randomised clinical study to determine the effect of a toothpaste containing enzymes and proteins on plaque oral microbiome ecology. Sci Rep. 2017 Feb 27;7:43344. PMID: 28240240; PMCID: PMC5327414. [CrossRef]

- Lynge Pedersen AM, Belstrøm D. The role of natural salivary defences in maintaining a healthy oral microbiota. J Dent. 2019 Jan;80 Suppl 1:S3-S12. PMID: 30696553. [CrossRef]

- Sanz M, Beighton D, Curtis MA, Cury JA, Dige I, Dommisch H, Ellwood R, Giacaman RA, Herrera D, Herzberg MC, Könönen E, Marsh PD, Meyle J, Mira A, Molina A, Mombelli A, Quirynen M, Reynolds EC, Shapira L, Zaura E. Role of microbial biofilms in the maintenance of oral health and in the development of dental caries and periodontal diseases. Consensus report of group 1 of the Joint EFP/ORCA workshop on the boundaries between caries and periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2017 Mar;44 Suppl 18:S5-S11. PMID: 28266109. [CrossRef]

- Cawley A, Golding S, Goulsbra A, Hoptroff M, Kumaran S, Marriott R. Microbiology insights into boosting salivary defences through the use of enzymes and proteins. J Dent. 2019 Jan;80 Suppl 1:S19-S25. Epub 2018 Oct 30. PMID: 30389429. [CrossRef]

- Thomas EL, Milligan TW, Joyner RE, Jefferson MM. Antibacterial activity of hydrogen peroxide and the lactoperoxidase-hydrogen peroxide-thiocyanate system against oral streptococci. Infect Immun. 1994 Feb;62(2):529-35. PMID: 8300211; PMCID: PMC186138. [CrossRef]

- Wertz PW, de Szalay S. Innate Antimicrobial Defense of Skin and Oral Mucosa. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020 Apr 3;9(4):159. PMID: 32260154; PMCID: PMC7235825. [CrossRef]

- Ihalin R, Loimaranta V, Tenovuo J. Origin, structure, and biological activities of peroxidases in human saliva. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2006 Jan 15;445(2):261-8. Epub 2005 Aug 2. PMID: 16111647. [CrossRef]

- van 't Hof W, Veerman EC, Nieuw Amerongen AV, Ligtenberg AJ. Antimicrobial defense systems in saliva. Monogr Oral Sci. 2014;24:40-51. Epub 2014 May 23. PMID: 24862593. [CrossRef]

- Soares RV, Lin T, Siqueira CC, Bruno LS, Li X, Oppenheim FG, Offner G, Troxler RF. Salivary micelles: identification of complexes containing MG2, sIgA, lactoferrin, amylase, glycosylated proline-rich protein and lysozyme. Arch Oral Biol. 2004 May;49(5):337-43. PMID: 15041480. [CrossRef]

- Marsh PD, Do T, Beighton D, Devine DA. Influence of saliva on the oral microbiota. Periodontol 2000. 2016 Feb;70(1):80-92. PMID: 26662484. [CrossRef]

- Nandlal B, Anoop NK, Ragavee V, Vanessa L. In-vitro Evaluation of toothpaste containing enzymes and proteins on inhibiting plaque re-growth of the children with high caries experience. J Clin Exp Dent. 2021 Jan 1;13(1):e43-e47. PMID: 33425230; PMCID: PMC7781222. [CrossRef]

- Min K, Bosma ML, John G, McGuire JA, DelSasso A, Milleman J, Milleman KR. Quantitative analysis of the effects of brushing, flossing, and mouthrinsing on supragingival and subgingival plaque microbiota: 12-week clinical trial. BMC Oral Health. 2024 May 17;24(1):575. PMID: 38760758; PMCID: PMC11102210. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 372.

- Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng HY, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Emberson JR, Hernán MA, Hopewell S, Hróbjartsson A, Junqueira DR, Jüni P, Kirkham JJ, Lasserson T, Li T, McAleenan A, Reeves BC, Shepperd S, Shrier I, Stewart LA, Tilling K, White IR, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019 Aug 28;366:l4898. PMID: 31462531. [CrossRef]

- Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, Henry D, Altman DG, Ansari MT, Boutron I, Carpenter JR, Chan AW, Churchill R, Deeks JJ, Hróbjartsson A, Kirkham J, Jüni P, Loke YK, Pigott TD, Ramsay CR, Regidor D, Rothstein HR, Sandhu L, Santaguida PL, Schünemann HJ, Shea B, Shrier I, Tugwell P, Turner L, Valentine JC, Waddington H, Waters E, Wells GA, Whiting PF, Higgins JP. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016 Oct 12;355:i4919. PMID: 27733354; PMCID: PMC5062054. [CrossRef]

- Carelli M, Zatochna I, Sandri A, Burlacchini G, Rosa A, Baccini F, Signoretto C. Effect of A Fluoride Toothpaste Containing Enzymes and Salivary Proteins on Periodontal Pathogens in Subjects with Black Stain: A Pilot Study. Eur J Dent. 2024 Feb;18(1):109-116. Epub 2023 Mar 4. PMID: 36870327; PMCID: PMC10959611. [CrossRef]

- Daly S, Seong J, Newcombe R, Davies M, Nicholson J, Edwards M, West N. A randomised clinical trial to determine the effect of a toothpaste containing enzymes and proteins on gum health over 3 months. J Dent. 2019 Jan;80 Suppl 1:S26-S32. PMID: 30696552. [CrossRef]

- Pedersen AML, Darwish M, Nicholson J, Edwards MI, Gupta AK, Belstrøm D. Gingival health status in individuals using different types of toothpaste. J Dent. 2019 Jan;80 Suppl 1:S13-S18. PMID: 30696551. [CrossRef]

- Kilian M, Chapple IL, Hannig M, Marsh PD, Meuric V, Pedersen AM, Tonetti MS, Wade WG, Zaura E. The oral microbiome - an update for oral healthcare professionals. Br Dent J. 2016 Nov 18;221(10):657-666. PMID: 27857087. [CrossRef]

- Helmerhorst EJ, Oppenheim FG. Saliva: a dynamic proteome. J Dent Res. 2007 Aug;86(8):680-93. PMID: 17652194. [CrossRef]

- Magacz M, Kędziora K, Sapa J, Krzyściak W. The Significance of Lactoperoxidase System in Oral Health: Application and Efficacy in Oral Hygiene Products. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Mar 21;20(6):1443. PMID: 30901933; PMCID: PMC6472183. [CrossRef]

- Haberska K, Svensson O, Shleev S, Lindh L, Arnebrant T, Ruzgas T. Activity of lactoperoxidase when adsorbed on protein layers. Talanta. 2008 Sep 15;76(5):1159-64. Epub 2008 May 21. PMID: 18761171. [CrossRef]

- Roger V., Tenovuo J, Lenander-Lumikari M, Söderling E, Vilja P. Lysozyme and lactoperoxidase inhibit the adherence of Streptococcus mutans NCTC 10449 (serotype c) to saliva-treated hydroxyapatite in vitro. Caries Research, 1994, 28.6: 421-428.

- Korpela A, Yu X, Loimaranta V, Lenander-Lumikari M, Vacca-Smith A, Wunder D, Bowen WH, Tenovuo J. Lactoperoxidase inhibits glucosyltransferases from Streptococcus mutans in vitro. Caries Res. 2002 Mar-Apr;36(2):116-21. PMID: 12037368. [CrossRef]

- Justiz Vaillant AA, Sabir S, Jan A. Physiology, Immune Response. 2024 Jul 27. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 30969623.

- Ramenzoni LL, Hofer D, Solderer A, Wiedemeier D, Attin T, Schmidlin PR. Origin of MMP-8 and Lactoferrin levels from gingival crevicular fluid, salivary glands and whole saliva. BMC Oral Health. 2021 Aug 5;21(1):385. PMID: 34353321; PMCID: PMC8340507. [CrossRef]

- Jalil RA, Ashley FP, Wilson RF, Wagaiyu EG. Concentrations of thiocyanate, hypothiocyanite, 'free' and 'total' lysozyme, lactoferrin and secretory IgA in resting and stimulated whole saliva of children aged 12-14 years and the relationship with plaque accumulation and gingivitis. J Periodontal Res. 1993 Mar;28(2):130-6. PMID: 8478785. [CrossRef]

- Paqué PN, Schmidlin PR, Wiedemeier DB, Wegehaupt FJ, Burrer PD, Körner P, Deari S, Sciotti MA, Attin T. Toothpastes with Enzymes Support Gum Health and Reduce Plaque Formation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jan 19;18(2):835. PMID: 33478112; PMCID: PMC7835853. [CrossRef]

- Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, Estupinan-Day S, Ndiaye C. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005 Sep;83(9):661-9. Epub 2005 Sep 30. PMID: 16211157; PMCID: PMC2626328.

- Belstrøm D, Holmstrup P, Nielsen CH, Kirkby N, Twetman S, Heitmann BL, Klepac-Ceraj V, Paster BJ, Fiehn NE. Bacterial profiles of saliva in relation to diet, lifestyle factors, and socioeconomic status. J Oral Microbiol. 2014 Apr 1;6. PMID: 24765243; PMCID: PMC3974179. [CrossRef]

- Green A, Crichard S, Ling-Mountford N, Milward M, Hubber N, Platten S, Gupta AK, Chapple ILC. A randomised clinical study comparing the effect of Steareth 30 and SLS containing toothpastes on oral epithelial integrity (desquamation). J Dent. 2019 Jan;80 Suppl 1:S33-S39. PMID: 30696554. [CrossRef]

| Authors/Year | Study design |

Population /age |

Aim of administration | Follow-up | Systemic conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carelli M. et al. 2024 [16] | RCT | 26/22,5 | Effects on DMFT, gingival indexes (GBI, Plaque control) and black stains | 14 weeks | Healthy |

| Daly S. et al. 2019 [17] | RCT | 229/32,6 | Effects on gingival indexes (MGI, BI, PI modified by Quigley and Hein) | 12 weeks | Healthy |

| Pedersen AML. et al. 2019 [18] | N-RCT | 305/18->56 | Effects on gingival indexes (MGI, BI, PI modified by Quigley and Hein) | 12 months | Healthy |

| Authors/Year | Conclusions |

|---|---|

| Carelli M. et al. 2024 [16] | Brushing with an electric toothbrush seemed to be more effective at reducing black stains compared to manual brush. This improvement was seen regardless of the toothpaste used. |

| Daly S. et al. 2019 [17] | Brushing with the enzyme and protein toothpaste resulted in lower plaque and bleeding indexes. |

| Pedersen AML. et al. 2019 [18] | Using a fluoride toothpaste containing enzymes and proteins for at least 1 year is associated with improved gum health compared to other fluoride toothpastes lacking these additional ingredients. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).