1. Introduction

Digital health acts in prevention, assessment, diagnosis, monitoring and treatment and integrates categories such as telehealth. [

1,

2] It overcomes barriers such as distance, transport and the availability of health professionals. [

3,

4] It benefits rural areas that have limited access to health services, as there are barriers related to access to technology and low electronic literacy. [

5] Areas with a higher population density also have advantages in terms of transport, rush hours and the resulting time spent. [

6]

COVID-19 has driven the substantial and sudden development of digital solutions in healthcare, leading to the adoption of telephysiotherapy, which according to the American Physical Therapy Association, was quickly accepted as an effective method. [

1,

3,

7] Digital physiotherapy uses communication devices, often with an internet connection, and can be provided in real time or asynchronously. [

5,

7,

8,

9,

10] This way, people can enjoy it in the comfort of their homes or in other locations, such as at work, as an alternative to the face-to-face approach or as a complement. [

7,

11] According to recent studies, this format is cost-effective, as it improves users’ adherence to treatment and reduces costs inherent in the healthcare process with high levels of satisfaction reported. [

1,

4,

5,

8] A 2023 systematic review found that telerehabilitation is as effective as face-to-face care in assessment, pain control, functionality and health education. [

8] In terms of validity and reliability, the two types of assessment can produce similar results. [

1] However, to be an effective and viable approach, users, interventions and means of communication must be selected, without forgetting preferences, risk profile, socioeconomic status, access to services and literacy and confidence in the use of technologies. [

5,

8,

12] But good results can be achieved without the need for specialised equipment. A study investigating the feasibility and effectiveness of telephone physiotherapy for the treatment of pain in low-resource settings showed a significant reduction in pain. [

12]

Self-assessment and self-monitoring are components that can be part of a physiotherapy regime practised remotely. Making the user responsible for managing and treating their condition helps them achieve better results and increases adherence, including to exercise. [

12] Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of remote functional assessment. Using the TUG test, acceptable results have been demonstrated, with excellent validity and reliability. [

9,

10,

13] Functional tests, rather than maximum effort tests, can be more easily accepted in a home environment. [

9]

The world’s population is ageing, and it is a challenge to maintain the health and well-being of older adults. [

14]

With the demographic trends that have emerged, and the costs associated with healthcare, it is believed that telehealth may be suitable for monitoring and supporting not only rehabilitation processes at home for the elderly, but also monitoring functional capacity and controlling risk factors that can prevent falls. Although this modality has already demonstrated its viability and acceptance by the elderly, there is still some lack of confidence in handling the technology. [

15,

16]

Falls and related injuries are an important public health problem

worldwide. Through screening in the community, it is possible to prevent them by identifying and stratifying the risk, to establish prevention strategies. [

17,

18] One of these pieces of information can be the results of a functional test, which can be fundamental for the physiotherapist to establish an appropriate clinical reasoning at that moment, support advice or justify the progression of an exercise plan. Consequently, the performance of a functional test by the person with or without the help of a family member/carer is potentially useful.

The TUG is a test strongly recommended for predicting falls in community-dwelling older adults. [

19,

20] As well as being simple, it assesses gait and balance through a combination of standing, sitting, walking and turning, and is a quick way of screening for the risk of falls. [

20,

21] Therefore, this study aims to test the validity and reliability of the TUG test result, self-administered at home, when compared to the same administered by a physiotherapist.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design, Setting and Participants

This study reports on a validity and reliability test model approved by the Ethics Committee of the Polytechnic Institute of Coimbra (Registration no. 149 CEIPC/ 2023). This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Registration no. NCT06481384, on 27th June 2024). The participants were adults aged 50 or over, living in the community, who took part in fall risk screening actions advertised in the usual places (municipalities and associations) in the centre of Portugal. The 37 participants who agreed to repeat the TUG test at home, independently, in the following 18-24 hours, were not given the results of that test carried out in person.

2.2. Outcome Measures

The outcome measures used to collect the data belong to the

FallSensing screening protocol [

17], to which were added questions related to the use and preference of communication technologies such as smartphones, tablets or computers and the availability of remote healthcare, namely telephysiotherapy.

2.2.1. Self-Reported Questionnaire

The self-report questionnaire included yes/no questions to characterise the sample in terms of sociodemographic and clinical data, history of falls, fear of falling, sedentary behaviours, measured by spending over 4 hours seated, 5 days or more per week, and questions on education level and health self-perception.

2.2.2. Self-Efficacy for Exercise

This 5-item questionnaire intended to analyse the confidence that a person has to perform exercise according to 5 different emotional states, such as feeling worried or having problems, feeling depressed, feeling tired, feeling tense, and being busy. [

17,

22]

2.2.3. Activities and Participation Profile Related to Mobility (PAPM)

PAPM is an 18-item scale to assess the difficulties an individual experiences while performing certain daily activities in their natural environment, such as interactions and social relations, education, employment, money management, and social and community life and influence a person’s active participation in society. It has a 5-point Likert scale from 0, meaning “no limitation or restriction,” to 4, meaning “complete limitation or restriction.” In between, 1 indicates “mild limitation or restriction,” 2 indicates “moderate limitation or restriction,” and 3 indicates “severe limitation or restriction” and since some activities may not apply, not all activities may be rated. [

17,

23]

2.2.4. Functional Tests

Functional capacity was assessed using a set of three tests, also associated with the cited protocol. [

17] The 10-Meter Walking Speed (10-MWS) test, 30s Seconds Sit to Stand (30s STS) test and TUG test. These tests assess domains such as gait, balance, functional mobility, lower limb strength and fall risk. [

24]

10-Meter Walking Speed test

The 10-MWS test was used to calculate the speed of accelerated walking, without running, timed over a 10-metre course. This can be useful in identifying those who are at risk or in need of intervention. Performing this test requires a 20-meter course, with 5 meters of acceleration and 5 meters of deceleration and 10 meters for timed walking. Markings are made at 5, 10, 15 and 20 meters and the time between 5 and 15 meters is recorded. The person is instructed to walk at their fastest speed, wearing comfortable footwear and walking aids if necessary. [

17]

30 Seconds Sit to Stand

The 30s STS test is a simple instrument used to assess lower limb strength and assess muscle weakness. The person is instructed to perform cycles of sitting and getting up from a chair as many times as possible for 30 seconds. At the end, the number of repetitions is recorded. [

17]

Timed up and Go test

The TUG test evaluates dynamic balance, mobility and strength of the lower limbs. The test begins with the person sitting in a standard chair and is instructed to walk a 3-metre course, turn around and return to the chair and sit down, as quickly as possible, without running and without the aid of the upper limbs. [

17]

2.3. TUG Testing Procedure

The participants were given a new informed consent to take part in the study and explained its purpose and procedure. Each one was measured in person by the physiotherapist (face-to-face assessment) and at home by the participant (self-administered assessment), 18 to 24 hours apart.

The face-to-face assessment was carried out by a physiotherapist. It should be noted that each participant performed a single TUG test and the result was recorded in seconds, to two decimal places. More details of the protocols used for the face-to-face and self-administered TUG test are shown in

Table 1.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out using IBM SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) software, version 29.0.1.0 for Windows. The interpretation of statistical analysis tests was conducted on a significance level of 0.05 (p≤0.05), with a confidence interval of 95%. Pearson´s correlation (r) was used for the analysis of correlations. In the descriptive analysis of the variables, the data was presented according to the mean and standard deviation or percentage, whichever was more appropriate. Pearson´s correlation (r) was used for the analysis of correlations with the values: 0.9-1.0 very strong, 0.70-0.89 strong, 0.40-0.69 moderate, 0.10-0.39 weak and 0.00-0.19 negligible. [

26] The data was also presented in terms of its distribution, with a Q-Q graph and T-test for normality. For the TUG test, the minimum clinically acceptable limit of 5 seconds was used, as previously reported. [

27]

Firstly, the validity between the self-administered assessment and the simultaneous face-to-face assessment was determined using paired t-tests. For concurrent validity between the self-administered assessment and the separate face-to-face assessment, the Bland and Altman limit of agreement statistic was used. [

28] Values that were within the minimum clinically acceptable difference were considered valid and acceptable. [

28]

The validity of the assessment carried out by the participant at home was also established by comparing it with the separate face-to-face assessment, using the mean difference of assessments, paired t-tests and intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC). [

9,

10]

The strength of reliability by ICC was analysed as follows: from 0 to 0.40 as poor, from 0.40 to 0.75 as fair to moderate and from 0.75 to 1.00 as excellent. [

29]

2. Results

Of the 37 participants, the average age was 61.78±6.88 (range 50-81) years and 73% were female.

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the participants, namely sociodemographic data, characteristics related to a history of falls, health perception, level of sedentary lifestyle, access to and preference for technologies and telehealth, the total score of the self-efficacy scale for exercise and the PAPM and the functional tests carried out in person. It also presents the results of the TUG test self-administered.

The

Table 3 represents correlations between the three functional tests carried out face-to-face and the self-administered TUG test, with corresponding Pearson´s correlation coefficient and level of significance.

3.1. Validity

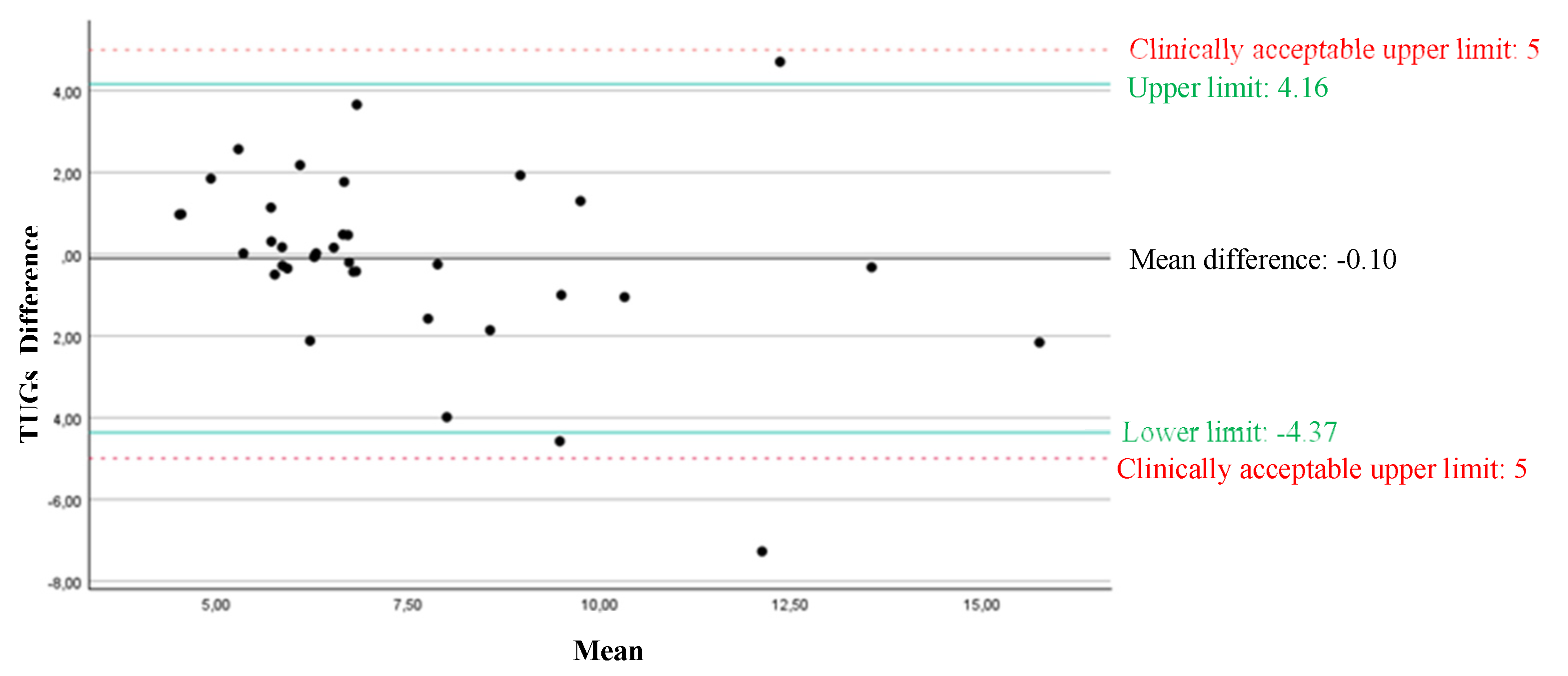

When comparing the face-to-face with the self-administered assessment, there were no significant differences between the two assessments for the TUG test (p>0.05), with a mean difference (95% confidence interval (CI)) of -0.10 (-0.87 to 0.62) seconds.

Figure 1 illustrates the graph with the mean difference and limits of agreement for the TUG test, when comparing the assessment carried out by the participant at home with the separate face-to-face assessment.

The validity of the assessment carried out by the participant at home compared to the separate face-to-face assessment for a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was excellent, with an ICC of 0.82 (0.65-0.91).

4. Discussion

To summarise, this study verified the validity, consistency and agreement of the use of telerehabilitation, using the self-administered TUG test, compared to face-to-face assessment in a group of 37 community-dwelling individuals aged 50 and over. Similar previous studies have also confirmed the validity and reliability of assessing functional capacity by telehealth using this test. The results of the present study are in line with those studies in which two types of assessment were compared, face-to-face and remote, and no statistically significant differences were found in the results of the TUG test in these two measurements. [

9,

10]

The TUG is a test that assesses balance, gait, functional mobility and lower limb strength [

22], and when it was carried out face-to-face it was strongly correlated with the other functional tests that were applied. The same was true when the test was carried out by the person themselves, which suggests that the fact that the person is responsible for carrying out this test in their home environment does not make it invalid or diminish its psychometric properties when compared to other measures.

Regarding validity, the results of this study show no differences between the two assessments for the TUG test, confirming a high degree of concurrent validity of the self-administered functional assessment compared to the face-to-face assessment. According to the ICC, the validity between the assessments was classified as excellent, with the limits of agreement within the clinically acceptable range. This suggests that, for the TUG test, this self-administered assessment method showed acceptable accuracy, with consistency and a low mean difference, meaning that, between the two assessments, the test results were close. Thus, this value supports this assessment method in this population, clearly indicating that a self-administered assessment, at home, using low-cost technologies is technically possible, valid and reliable.

The sample in this study has an above-average functional capacity when compared to the Portuguese population in general, in relation to the three functional tests applied. [

30] A more sedentary lifestyle is practised by more than half of the sample in this study, however it should not be an exclusion criterion to consider when choosing a participant to obtain healthcare through telehealth, since it allowed viable results to be obtained between the two assessments.

It should be noted that most participants reported that they were willing to obtain health care at a distance, particularly telephysiotherapy. Similarly, the smartphone is the preferred technology. This indicates that most of the participants in this study are open and has some level of digital literacy, which may have been a contributing factor to the feasibility and reliability of this method in this study. The literacy level was varied, and within the total sample there were a considerable number of individuals at each level of education, demonstrating that this method can produce successful results regardless of educational level.

4.1. Strongs

As far as we know, this is the first study to investigate self-administered functional assessment by the user themselves in their home environment, using low-cost technology, specifically mobile phones, without the need for internet access. It uses a measure of functional capacity that is commonly used for assessment in hospitals, clinics or other contexts, particularly in community fall risk screening, but may be more acceptable to carry out at home, bringing great benefits for empowering older adults to self-monitor their functional condition over time.

Previous studies on the validity and reliability of assessments using remote digital technology have been carried out in controlled environments, with professional supervision, mostly using technologies such as videoconferencing systems as a strategy for direct communication with the user. [

1,

5,

8,

9,

10,

13,

31] It is therefore questionable whether these results can be generalised to uncontrolled home environments with the person and/or carer alone, where these types of technologies may be inaccessible, limited or poorly handled. The sample size of this study is also considerably larger compared to most studies of this kind.

The fact that all participants took the test in person first can have a learning effect that will influence the result of the home measurement. Whilst this may seem like a bias, teaching and demonstrating the test is part of the process of empowering the person, who should never be left to their own devices when it comes to the performance of a gold standard test.

4.2. Limitations

There are some limitations to this study. Recruitment bias is a limitation, in that those who agreed to take part in the study may be more favourable to this assessment method, since various factors were considered, including levels of understanding and ability.

The sample had high values for all the functional tests, which could make it impossible to use the same method via telehealth to older adults with other characteristics.

5. Conclusions

Community-dwelling adults aged 50 and over can perform the TUG test independently in their own homes after receiving instructions on how to do it, and this functional test is easy and quick to implement since this test has been successfully measured under the real-life conditions of a telephysiotherapy assessment.

Excellent validity and reliability were demonstrated between the two forms of assessment. In general, we can interpret these data considering the context of the study design and the sample size. The limits of agreement were within the predefined clinically acceptable limits for this test.

Teaching the TUG test to be performed at home could represent a strategy for remote monitoring, both from the perspective of empowering older adults to manage their own condition and ageing process, and to provide periodic feedback to the physiotherapist, as part of a fall prevention programme.

Even so, more studies with larger samples and different populations are needed to be able to generalise these results and provide more robust evidence of the practice of telephysiotherapy as an effective and viable method for self-monitoring and implement colaborative preventive strategies for active and healthy ageing, as well as for the awareness for the risk of falling.

Supplementary Materials

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request due to privacy and ethical reasons.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R. and A.C.M.; methodology, M.R. and A.C.M.; validation, M.R. and A.C.M.; formal analysis, M.R., M.T., C.C. and A.C.M.; investigation, M.R., M.T. and C.C.; data curation, M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.; writing—review and editing, M.R. and A.C.M.; supervision, A.C.M.; project administration, M.R., M.T. and C.C.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declara-tion of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Polytechnic University of Coimbra (CEIPC), on the 27th December 2023, in Portugal (Registration code 149_CEIPC_2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and ethical reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bernhardsson S, Larsson A, Bergenheim A, Ho-Henriksson CM, Ekhammar A, Lange E, et al. Digital physiotherapy assessment vs conventional face-to-face physiotherapy assessment of patients with musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review. Chaudhary P, editor. PLOS ONE. 2023 Mar 21;18(3):e0283013. [CrossRef]

- Overview [Internet]. health.ec.europa.eu. Available from: https://health.ec.europa.eu/ehealth-digital-health-and-care/overview_en.

- Telehealth Advocacy [Internet]. APTA. Available from: https://www.apta.org/advocacy/issues/telehealth.

- Roitenberg N, Ben-Ami N. Qualitative exploration of physical therapists’ experiences providing telehealth physical therapy during COVID-19. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice [Internet]. 2023 Aug 1;66:102789. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2468781223000747?casa_token=AratkV_BHkAAAAA:adWZn1Xl6c90LK89DRKsJYR4l80t7Qj_olqq1MwkAc8eqLmSGbJrFjX0MEpO1eLhk3ycBsHQ4RE.

- Zischke C, Simas V, Hing W, Milne N, Spittle A, Pope R. The utility of physiotherapy assessments delivered by telehealth: A systematic review. Journal of Global Health. 2021 Dec 18;11. [CrossRef]

- Digital Health in Practice [Internet]. APTA. Available from: https://www.apta.org/your-practice/practice-models-and-settings/digital-health-in-practice.

- Hwang R, Elkins MR. Telephysiotherapy. Journal of Physiotherapy. 2020 Jul;66(3):143–4.

- Muñoz-Tomás MT, Burillo-Lafuente M, Vicente-Parra A, Sanz-Rubio MC, Suarez-Serrano C, Marcén-Román Y, et al. Telerehabilitation as a Therapeutic Exercise Tool versus Face-to-Face Physiotherapy: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health [Internet]. 2023 Feb 28;20(5):4358. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10002129/.

- Hwang R, Mandrusiak A, Morris NR, Peters R, Korczyk D, Russell T. Assessing functional exercise capacity using telehealth: Is it valid and reliable in patients with chronic heart failure? Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2016 Jul 9;23(2):225–32. [CrossRef]

- Mani S, Sharma S, Omar B, Paungmali A, Joseph L. Validity and reliability of Internet-based physiotherapy assessment for musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare [Internet]. 2017 Apr 1;23(3):379–91. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27036879/.

- Moulaei K, Sheikhtaheri A, Nezhad MS, Haghdoost A, Gheysari M, Bahaadinbeigy K. Telerehabilitation for upper limb disabilities: a scoping review on functions, outcomes, and evaluation methods. Archives of Public Health. 2022 Aug 23;80(1).

- Adhikari SP, Shrestha P, Dev R. Feasibility and Effectiveness of Telephone-Based Telephysiotherapy for Treatment of Pain in Low-Resource Setting: A Retrospective Pre-Post Design. Pain Research and Management. 2020 May 8;2020:1–7.

- Russell TG, Hoffmann TC, Nelson M, Thompson L, Vincent A. Internet-based physical assessment of people with Parkinson disease is accurate and reliable: A pilot study. The Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 2013;50(5):643.

- Liu L, Stroulia E, Nikolaidis I, Miguel-Cruz A, Rios Rincon A. Smart homes and home health monitoring technologies for older adults: A systematic review. International Journal of Medical Informatics [Internet]. 2016 Jul 1;91:44–59. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1386505616300648?via%3Dihub.

- Pol M, Qadeer A, Margo van Hartingsveldt, Mohamed-Amine Choukou. Perspectives of Rehabilitation Professionals on Implementing a Validated Home Telerehabilitation Intervention for Older Adults in Geriatric Rehabilitation: Multisite Focus Group Study. JMIR rehabilitation and assistive technologies. 2023 Jul 18;10:e44498–8.

- Dryden EM, Kennedy MA, Conti J, Boudreau JH, Anwar CP, Nearing K, et al. Perceived benefits of geriatric specialty telemedicine among rural patients and caregivers. Health Services Research. 2022 Sep 14.

- Martins AC, Moreira J, Silva C, Silva J, Tonelo C, Baltazar D, et al. Multifactorial Screening Tool for Determining Fall Risk in Community-Dwelling Adults Aged 50 Years or Over (FallSensing): Protocol for a Prospective Study. JMIR Research Protocols. 2018 Aug 2;7(8):e10304.

- Instrumented timed up and go: Fall risk assessment based on inertial wearable sensors | IEEE Conference Publication | IEEE Xplore [Internet]. ieeexplore.ieee.org. [cited 2024 Feb 8]. Available from: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7533778.

- Lee J, Geller AI, Strasser DC. Analytical Review: Focus on Fall Screening Assessments. PM&R. 2013 Jul;5(7):609–21.

- Montero-Odasso M, van der Velde N, Martin FC, Petrovic M, Tan MP, Ryg J, et al. World guidelines for falls prevention and management for older adults: A global initiative. Age and Ageing. 2022 Sep;51(9).

- Colon, Cinthia & McDermott, Cara & Lee, Deborah & Berry, Sarah.Risk Assessment and Prevention of Falls in Older Community-Dwelling Adults: A Review. JAMA. 2024;331. 10.1001/jama.2024.1416.

- Martins AC, Silva C, Moreira J, Rocha C, Gonçalves A. Escala de autoeficácia para o exercício: validação para a população portuguesa. In: Pocinho R, Ferreira SM, Anjos VN. (coord.). Conversas de Psicologia e do Envelhecimento Ativo. 1ª Edição, Coimbra, Associação Portuguesa Conversas de Psicologia; 2017:126-141.

- Martins, AC. Development and initial validation of the Activities and Participation Profile related to Mobility (APPM). In: BMC Health Serv Res. 2016:78-79.

- INSTRUMENTOS DE MEDIDA EM FISIOTERAPIA CARDIORRESPIRATÓRIA [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://www.apfisio.pt/wpcontent/uploads/2019/07/INSTRUMENTOS_MEDIDA_FISIOTERAPIA_CARDIORRESPIRATORIA.pdf.

- Timed Up and Go [Internet]. Shirley Ryan AbilityLab - Formerly RIC. 2013. Available from: https://www.sralab.org/rehabilitation-measures/timed-and-go.

- Schober P, Boer C, Schwarte LA. Correlation coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2018;126(5):1763–8.

- Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society [Internet]. 1991;39(2):142–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1991946/.

- Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet (London, England) [Internet]. 1986 Feb 8;1(8476):307–10. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2868172/.

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin [Internet]. 1979 Mar 1;86(2):420–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18839484/.

- Martins A. Prevenção de Quedas 14h30 Mesa Redonda QUEM CUIDA DOS MAIS VELHOS? [Internet]. Available from: https://spgg.com.pt/UserFiles/File/023_fallsensing_prevenir_as_quedas.pdf.

- Durfee WK, Savard L, Weinstein S. Technical Feasibility of Teleassessments for Rehabilitation. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2021 Apr 12];15(1):23–9. Available from: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/4126533.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).