1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a public health problem with increasing incidence in the global population and a high mortality rate that is a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) [

1]. Although type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and hypertension (HT) are the primary causes of CKD, studies have appeared in recent years that suggest that changes in intestinal microbiota and permeability may be related to this disease. As a result of impaired intestinal permeability due to various reasons (tight junction downregulation, viral intestinal infections, environmental toxins, toxic food, etc.), pathogens and toxins originating from the intestine pass into the systemic blood circulation [

2]. As a matter of fact, impaired intestinal permeability, together with an increased toxin load in the circulation, paves the way for the formation of T2DM, HT, and eventually CKD [

2,

3].

Endothelial dysfunction (ED) is the initial stage of the pathological process leading to CVD and adversely affects the prognosis of patients with CKD [

4]. VCAM-1, demonstrated as a marker of ED, plays a role in the pathogenesis of many different metabolic disorders including CKD [

5]. In addition, systemic inflammation (SI) is another important paradigm that occurs as a result of renal function deterioration in CKD patients and negatively affects the prognosis of the disease. IL-6 is strongly associated with SI and has shown importance in clinical progression in patients with CKD [

6].

Zo, identified for the first time by Fasano et al., is remarkable among the molecules that are indicators of intestinal permeability [

7]. Dysbiosis in the intestinal system and decreased mucosal permeability pave the way for an increase in plasma Zo levels. Zo, which is associated with many clinical pathologies, especially celiac disease, is in the spotlight as a marker of increased intestinal permeability [

8]. Additionally, a few studies conducted in recent years emphasize that serum Zo level may play a role in the pathogenesis of CKD. However, plasma Zo levels in patients with CKD vary in the literature. Indeed, Karataş et al. observed that Zo levels in hemodialysis patients were higher compared to the control group [

9]. On the other hand, Lukaszyk et al. showed that Zo was significantly lower in patients with CKD than in the control group [

10]. In light of these data, although a few studies in the literature remark that Zo may be associated with CKD, the pathophysiology of this relationship and the role of the molecule in the disease process are unclear [

11,

12].

Today, we know that in CKD patients, disease prognosis is negatively affected by ED, SI, impaired metabolic regulation, and increased toxic load, especially impaired renal functions. On the other hand, the role of Zo with pathogenetic processes in patients with CKD has not been fully elucidated. In this study, we aimed to examine the relationship between plasma Zo level and ED, SI, metabolic components, and especially renal functions in patients with CKD.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted at a single center and was cross-sectional, and informed consent was obtained from all participants before commencement. It was designed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and local ethics committee approval was obtained from the Local Ethics Committee of Balikesir University Medical School (date: 19.04.2023, approval number: 2023/51).

Study Design and Population

One hundred sixty-three participants were enrolled in this study and were divided into patient and control groups, according to the presence of stage 3-5 CKD. Exclusion criteria were active infection, acute inflammatory diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, etc.), malignancies, pregnancy, abnormal thyroid dysfunction, and receiving renal replacement therapy.

Anthropometric Measurements

All participants provided a medical history and underwent a clinical examination. The height and weight of all patients were measured using a standard method, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight (kg) by height squared (m2) (Figure 1). Waist circumference (WC) was measured using the lower costal margin and the anterior superior iliac crests as the reference. Blood pressure (BP) was measured three times in the outpatient clinic and the average value was registered.

Figure 1. Body mass index assessment formula. BMI = [weight (kg)] / [height squared (m2)].

Biomarker function

The circulating Zo level was investigated as a marker of intestinal permeability. Additionally, another intestinal permeability marker, the Claudin-3 molecule, was examined as a control for possible erroneous results in Zo measurement [

13]. Furthermore, VCAM-1 and IL-6 biomarkers were used for ED and SI assessment, respectively [

5,

6].

Biochemical Analysis

The complete blood count (CBC) was performed using the DxH 800 (Beckman Coulter Inc., USA) analyzer. Serum fasting plasma glucose (FPG), creatinine, urea, total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), triglycerides (TGL), sodium, potassium, and albumin levels were measured with the AU680 (Beckman Coulter Inc., USA) biochemical autoanalyzer. The Friedewald formula and the Chronic Kidney Disease–Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula were used to calculate low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and glomerular filtration rate (GFR), respectively [

14,

15].

Zo (Cat No: 201-12-5578, SunRed Biological Technology, Shanghai, China), claudin-3 (Cat No: 201-12-2303, SunRed), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) (Cat No: 201-12-0204, SunRed), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (Cat No: 201-12-0091, SunRed) levels were analyzed in serum samples using the ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) method. The measurement ranges for Zo, claudin-3, VCAM-1, and IL-6 were 0.25-70 ng/ml, 0.5-60 ng/ml, 0.4-60 ng/ml, and 3-600 ng/L, respectively. Before the analyses, serum samples were diluted with physiological saline solution at ratios of 1/10 for Zo analysis and 1/50 for VCAM-1 analysis. No pretreatment was applied to the serum samples for claudin-3 and IL-6 analyses.

CKD definition

In this clinical study, patients with CKD stages 3-5 not on dialysis were enrolled. CKD was defined as the patient group whose GFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m

2 for three months. In our clinic, where pre-dialysis patients were primarily followed up, this group was excluded from this study because there were too few stage 1 and 2 patients. On the other hand, the control group was defined as patients with GFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m

2 and without any signs of renal damage (albuminuria, urinary sediment abnormalities, etc.) [

16].

Statistical analysis

All participants were divided into two groups and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was applied to determine the suitability of continuous variables for normal distribution among these two groups. Continuous variables are shown as the mean ± standard deviation, while categorical variables are expressed as the percentage (%). The chi-square test was performed to compare categorical variables. Continuous variables were compared in pairs using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test when they were not normally distributed, whereas the parametric independent Student’s t test was used when they were normally distributed.

The Spearman correlation analysis was performed between Zo levels and other parameters. Linear regression analysis was performed to show the interaction between GFR and Zo levels. The relationship between these variables was examined in an adjusted model that included the covariates identified in the initial univariate analyses. Unadjusted and model 1- and model 2-adjusted β values were calculated. While model 1 was created according to age, model 2 was created according to systolic (SBP) and diastolic (DBP) blood pressure in addition to model 1.

The SPSS package program was performed in the statistical analysis and a p-value of <0.05 was found to be statistically significant.

3. Results

A total of 104 patients with CKD (mean age 58.9 ±1.4) and 59 control subjects (mean age 59.0 ±1.1) were included. The causes of CKD in the patient group were HT (44.2%), T2DM (33.3%), glomerulonephritis (12.2%), polycystic kidney disease (6.1%), and unknown (4.2%). Age (p = 0.934) and gender (p = 0.196) ratios were similar between the groups, and comparisons of the demographic and the laboratory parameters are given in

Table 1.

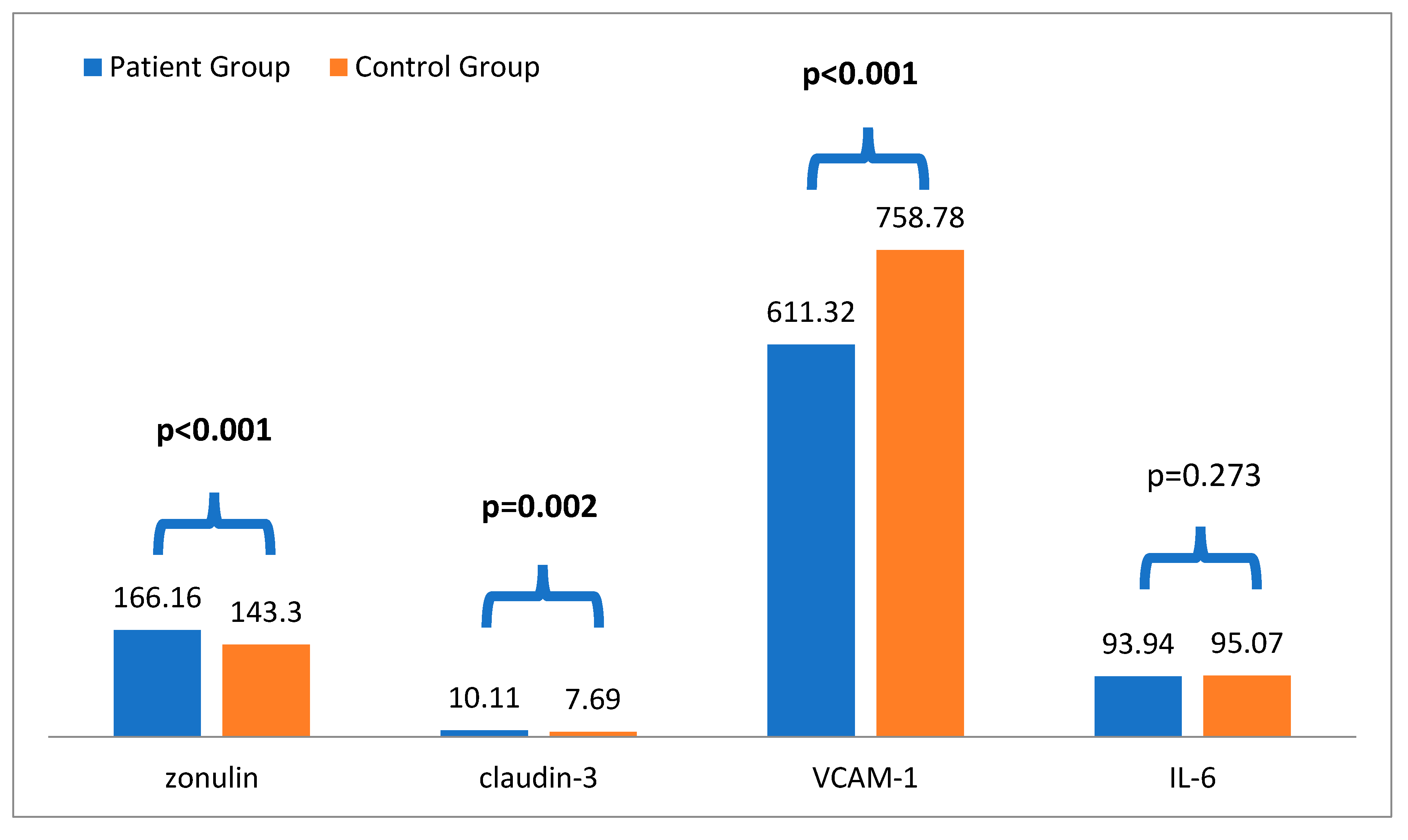

According to the results, in the comparison analysis, plasma Zo levels in the stage 3-5 CKD group (166.16 ± 53.54) were significantly higher than those in the control group (143.30 ± 60.92) (p < 0.001). Additionally, plasma claudin-3 levels in the stage 3-5 CKD group (10.11 ± 9.24) were significantly higher than those in the control group (7.69 ± 6.43) (p = 0.002). Furthermore, patients with CKD had higher systolic blood pressure (p = 0.005), blood urea, creatinine, and potassium (p < 0.001 for all) than the controls. On the other hand, hemoglobin, GFR, and VCAM-1 levels (p < 0.001 for all) were lower in patients with stage 3-5 CKD compared to the control groups (

Table 1 and

Figure 2).

In the correlation analysis, serum Zo level showed a positive correlation with claudin-3 (r = 0.612, p < 0.001), IL-6 (r = 0.307, p < 0.001), and creatinine (r = 0.313, p < 0.001) and a negative correlation with GFR (r = -0.320, p < 0.001) and TC (r = -0.074, p = 0.047) (

Table 2). This result is important in terms of showing the consistency of circulating levels of Zo, a marker of intestinal permeability. Additionally, our results show that there was a correlation, albeit weak, between circulating Zo levels and renal function and IL-6. Moreover, in linear regression analysis, Zo level was significantly associated with GFR after adjusting for age and SBP (β value = -0.918, p = 0.012) (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

In the present study, it was found that plasma Zo levels were statistically significantly higher in patients with CKD compared to the control group. Additionally, plasma Zo levels were statistically correlated with impaired renal function tests, claudin-3, and IL-6—a marker of SI—but this relationship was not detected in terms of ED. Furthermore, our results demonstrated that circulating Zo level was observed to predict GFR independently of age and BP. In light of these data, current findings suggest that serum Zo levels are negatively correlated with CKD levels and positively correlated with SI. Therefore, CKD patients may be screened for Zo levels and circulating Zo levels may be used as an SI marker in this patient group.

Claudin-3 is a key protein used in the assessment of intestinal barrier integrity and is an important component of tight junctions [

17]. In various studies, zonulin and claudin-3 have been evaluated together as indicators of gastrointestinal integrity [

18,

19]. In our study, the detection of elevated claudin-3 levels along with zonulin in CKD supports the notion of increased intestinal permeability in CKD. Furthermore, by using both intestinal markers together, we aimed to prevent any misinterpretation that could arise from potential technical errors during the measurement process. Indeed, the present study, Zo levels were positively correlated with claudin-3 levels, which have been used as a permeability marker for many years.

Zo is a haptoglobin protein that can cause an opening in the tight junctions of the intestinal epithelium and plays a role in regulating permeability in the intestinal mucosa [

20,

21]. High Zo levels increase mucosal permeability, and increased mucosal permeability causes endotoxins in the intestinal lumen to pass into the systemic circulation [

22]. Moreover, CKD patients experience an increased formation of indoles, phenols, and amines as a result of changes in the intestinal microflora that occur over time. These gut-derived uremic toxins have been associated with the progression of renal damage, increased SI, and oxidative stress in patients with CKD [

23]. Moreover, this condition suggests that elevated Zo levels may play a role in diseases characterized by SI, especially T2DM and obesity [

24,

25]. However, the role of plasma Zo levels is unclear in patients with CKD. In a cross-sectional study, Şirin et al. investigated serum Zo levels in ninety patients with T2DM and 30 healthy controls. No difference was found between the groups in terms of serum Zo levels [

26]. In another study, Lukaszyk et al. studied zonulin levels in 88 patients with early stages of CKD and 23 healthy subjects. The patient group had significantly lower serum Zo levels than the healthy subjects [

10]. In a case–control study, Carpes et al. evaluated zonulin levels in patients with diabetic kidney disease. T2DM patients (n = 26) had higher zonulin levels than non-T2DM (n = 18) controls and advanced diabetic kidney disease cases (n = 22). Furthermore, plasma Zo level was correlated positively with GFR and negatively with albuminuria level [

27]. On the other hand, in a prospective cohort study, Karataş et al. investigated the relationship between Zo level and disease progression in patients with CKD. In this study, three groups consisting of 37 patients with pre-dialysis, 30 patients with hemodialysis, and 20 healthy subjects were evaluated. Interestingly, serum Zo levels had been shown to be lower in the pre-dialysis patient group and higher in the hemodialysis patient group compared to the control group [

9]. In light of these data, we found that plasma Zo levels were higher in patients with CKD stage 3-5 not on dialysis compared to the control group. In addition, the fact that Zo levels were correlated negatively with GFR and positively with creatinine levels supported our findings. Indeed, in the current modeling, Zo predicted the change in GFR independently of age and BP. Our results showed that Zo, a marker of a damaged intestinal mucosal barrier, was elevated in patients with CKD and correlates with impaired renal function tests.

SI is mechanistically related to renal kidney injury and CVD in patients with CKD [

28]. The deterioration in the intestinal microbiota causes an increase in a few different bacterial toxins [

29]. Together with impaired intestinal permeability, increased plasma Zo levels cause toxic end products from the intestinal mucosa to enter the systemic circulation, which may lead to increased SI over time [

30]. Furthermore, this process may lead to progression to renal damage in the background of inflammation over time. However, the relationship between plasma Zo levels with SI has not been fully demonstrated in the current literature. In a cross-sectional study, Al-Obaide et al. investigated the gut microbiota associated with inflammatory biomarkers in patients with T2DM and CKD. Plasma Zo measurement showed an increased level in twenty patients with T2DM-CKD compared to twenty healthy subjects. Furthermore, plasma Zo levels were positively correlated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) endotoxin levels in the patient group [

29]. In a case–control study, Ficek et al. investigated 150 hemodialysis patients and 30 healthy subjects for intestinal permeability and inflammation. Interestingly, plasma Zo levels were higher in hemodialysis patients compared to the control groups, but there was no correlation between Zo levels and plasma IL6, TNFα, LPS, and d-lactates [

31]. Additionally, Lukaszyk et al. showed that plasma Zo levels were similar in CKD patients with and without inflammation [

10]. On the other hand, in the study of Şirin et al., there was a significant positive correlation between plasma Zo levels and IL-6 in patients with diabetic kidney disease [

26]. In light of all these data, in the present study, as acute inflammatory conditions were excluded, Il-6 levels were similar between the patient and control groups, as expected. However, plasma Zo level was positively correlated with Il-6 in the whole-group analysis. We believe that this is important in terms of showing that an increase in Zo levels may lead to inflammatory processes.

The endothelium is a crucial factor that plays a role in maintaining vascular wall tone, integrity, and structure. ED may occur over time in CKD patients secondary to increased uremic toxins and proinflammatory cytokines [

32]. In the literature, there are a few studies investigating the relationship between VCAM-1, which can be used as an ED indicator, and circulating Zo. In a cross-sectional study conducted by Ntlahla et al., the relationship between gut permeability and ED markers was evaluated in 151 South African youth. Interestingly, plasma zonulin levels negatively associated with ADMA but positively associated with NO in males [

33]. In a case–control study, Loffredo et al. investigated the relationship between plasma Zo levels and NADPH oxidase-2 activation in patients with coronary microvascular angina. Plasma Zo level was a significant predictor of elevated NADPH oxidase-2 activation in multiple linear regression analysis [

34]. In light of these data, we investigated the relationship between plasma Zo level and VCAM-1, which is considered an ED marker, and there was no significant correlation between these two biomarkers. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the relationship between Zo with VCAM-1 in patients with CKD stage 3-5 not on dialysis. Our findings showed the need to elucidate the relationship between Zo and ED in patients with CKD.

The strength of this study is that the relationship between plasma Zo levels and many different paradigms (renal function, SI, and ED) was evaluated together. The present study has several limitations: First, the results from this study should be generalized with caution, as it was conducted at a single center. Second, as the design of our study was cross-sectional, it does not allow us to make a strong causal inference between Zo and CKD. Third, the uremic toxin analysis of the patients could not be evaluated. Fourth, due to the cross-sectional study design, the mechanistic relationship between Zo and renal function and between SI and ED cannot be fully assessed. Lastly, ED was evaluated using biomarkers, and imaging methods showing morphological change could not be used.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our results suggest that a high Zo level is independently associated with impaired renal function in patients with CKD stage 3-5 not on dialysis. Furthermore, Zo might be associated with SI but not with ED markers. Therefore, checking the serum Zo levels in patients with CKD stage 3-5 not on dialysis seems to be a useful guide for assessing renal function and inflammation. However, prospective, randomized controlled trials are needed to improve our findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K., O.T., and S.E.K.; methodology, A.K., O.T., S.E.K., and H.S.; software, A.K., S.E.K., and O.K.B.; validation, A.K., O.T., S.E.K., and S.U.; formal analysis, A.K., S.E.K., S.U., and T.M.; investigation, A.K., O.T., and H.S.; resources; A.K.; data curation, A.K., H.S., O.K.B., I.B., E.P., S.U., and T.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K., O.T., S.E.K., and S.U.; writing—review and editing, A.K., O.T., S.E.K. H.S., OK.B., and S.U., supervision, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was designed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and local ethics committee approval was obtained from the Local Ethics Committee of Balikesir University Medical School (date: 19.04.2023, approval number: 2023/51).

Informed Consent Statement

Consent was obtained from all included patients.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Balıkesir University Scientific Research Project unit for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jha V.; Garcia-Garcia G.; Iseki K.; Li Z.; Naicker S.; Plattner B.; Saran R.Ü.; Wang A.Y.; Yang C.W. Chronic kidney disease: global dimension and perspectives. Lancet. 2013, 382, 260-272. [CrossRef]

- Linh H.T.; Iwata Y.; Senda Y.; Sakai-Takemori Y.; Nakade Y.; Oshima M.; Nakagawa-Yoneda S.; Ogura H.; Sato K.; Minami T.; et al. Intestinal Bacterial Translocation Contributes to Diabetic Kidney Disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2022, 33, 1105-1119. [CrossRef]

- Bischoff S.C.; Barbara G.; Buurman W.; Ockhuizen T.; Schulzke J.D.; Serino M.; Tilg H.; Watson A.; Wells J.M. Intestinal permeability-a new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014, 14, 189. [CrossRef]

- Baaten CCFMJ.; Vondenhoff S.; Noels H. Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and Increased Cardiovascular Risk in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease. Circ Res. 2023, 132, 970-992. [CrossRef]

- Liew H.; Roberts M.A.; Pope A.; McMahon L.P. Endothelial glycocalyx damage in kidney disease correlates with uraemic toxins and endothelial dysfunction. BMC Nephrol. 2021, 22, 21. [CrossRef]

- Batra G.; Ghukasyan Lakic T.; Lindbäck J.; Held C.; White H.D.; Stewart R.A.H.; Koenig W.; Cannon C.P.; Budaj A.; Hagström E.; et. al.; STABILITY Investigators. Interleukin 6 and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease and Chronic Coronary Syndrome. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 6, 1440-1445. [CrossRef]

- Fasano A.; Not T.; Wang W.; Uzzau S.; Berti I.; Tommasini A.; Goldblum S.E. Zonulin, a newly discovered modulator of intestinal permeability, and its expression in coeliac disease. Lancet. 2000, 355, 1518–1519. [CrossRef]

- Serek P.; Oleksy-Wawrzyniak M. The Effect of Bacterial Infections, Probiotics and Zonulin on Intestinal Barrier Integrity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11359. [CrossRef]

- Karatas A.; Cihan M.; Dugeroglu H.; Kaya Y.; Bayrak T.; Canakci E. The relation of zonulin level to inflammation and metabolic conditions in patients with chronic kidney disease. Acta Medica Mediterr. 2019, 35, 1061.

- Lukaszyk E.; Lukaszyk M.; Koc-Zorawska E.; Bodzenta-Lukaszyk A.; Malyszko J. Zonulin, inflammation and iron status in patients with early stages of chronic kidney disease. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2018, 50, 121-125. [CrossRef]

- Yu J.; Shen Y.; Zhou N. Advances in the role and mechanism of zonulin pathway in kidney diseases. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2021, 53, 2081-2088. [CrossRef]

- Dschietzig T.B.; Boschann F.; Ruppert J.; Armbruster F.P.; Meinitzer A.; Bankovic D.; Mitrovic V.; Melzer C. Plasma Zonulin and its Association with Kidney Function, Severity of Heart Failure, and Metabolic Inflammation. Clin. Lab. 2016, 62, 2443-2447. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Diaz-del-Campo, N.; Castelnuovo, G.; Ribaldone, D.G.; Caviglia, G.P. Fecal and Circulating Biomarkers for the Non-Invasive Assessment of Intestinal Permeability. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1976. [CrossRef]

- Friedewald W.T.; Levy R.I.; Fredrickson D.S. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 1972, 18, 499-502.

- Levey A.S.; Stevens L.A.; Schmid C.H.; Zhang Y.L.; Castro A.F. 3rd; Feldman H.I.; Kusek J.W.; Eggers P.; Van Lente F.; Greene T.; et al.; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration). A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009; 150, 604-612. [CrossRef]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, S117-S314. [CrossRef]

- Sikora M.; Chrabąszcz M.; Waśkiel-Burnat A.; Rakowska A.; Olszewska M.; Rudnicka L. Claudin-3 - a new intestinal integrity marker in patients with psoriasis: association with disease severity. J. Eur. Acad Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 1907-1912. [CrossRef]

- Mooren F.C.; Maleki B.H.; Pilat C.; Ringseis R.; Eder K.; Teschler M.; Krüger K. Effects of Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 on exercise-induced disruption of gastrointestinal integrity. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2020, 120, 1591-1599. [CrossRef]

- Karim A.; Muhammad T.; Shahid Iqbal M.; Qaisar R. A multistrain probiotic improves handgrip strength and functional capacity in patients with COPD: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2022, 102, 104721. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi A.; Lammers K.M.; Goldblum S.; Shea-Donohue T.; Netzel-Arnett S.; Buzza M.S.; Antalis T.M.; Vogel S.N.; Zhao A.; Yang S.; et al. Identification of human zonulin, a physiological modulator of tight junctions, as prehaptoglobin-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 16799-16804. [CrossRef]

- Fasano A. Zonulin and its regulation of intestinal barrier function: the biological door to inflammation, autoimmunity, and cancer. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91, 151-175. [CrossRef]

- Sturgeon C.; Fasano A. Zonulin, a regulator of epithelial and endothelial barrier functions, and its involvement in chronic inflammatory diseases. Tissue Barriers. 2016, 4, e1251384. [CrossRef]

- Cigarran Guldris S.; González Parra E.; Cases Amenós A. Gut microbiota in chronic kidney disease. Nefrologia. 2017, 37, 9-19. [CrossRef]

- Zhang D.; Zhang L.; Zheng Y.; Yue F.; Russell R.D.; Zeng Y. Circulating zonulin levels in newly diagnosed Chinese type 2 diabetes patients. Diabetes Res. Clin Pract. 2014, 106, 312-318. [CrossRef]

- Zak-Gołąb A.; Kocełak P.; Aptekorz M.; Zientara M.; Juszczyk L.; Martirosian G.; Chudek J.; Olszanecka-Glinianowicz M. Gut microbiota, microinflammation, metabolic profile, and zonulin concentration in obese and normal weight subjects. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2013, 2013, 674106. [CrossRef]

- Sirin F.B.; Korkmaz H.; Eroglu I.; Afsar B.; Kumbul Doguc D. Serum zonulin levels in type 2 diabetes patients with diabetic kidney disease. Endokrynol. Pol. 2021, 72, 545-549. [CrossRef]

- Carpes L.S.; Nicoletto B.B.; Canani L.H.; Rheinhemer J.; Crispim D.; Souza G.C. Could serum zonulin be an intestinal permeability marker in diabetes kidney disease? PLoS One. 2021, 16, :e0253501. [CrossRef]

- Cobo G.; Lindholm B.; Stenvinkel P. Chronic inflammation in end-stage renal disease and dialysis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2018, 33, iii35-iii40. [CrossRef]

- Al-Obaide M.A.I.; Singh R.; Datta P.; Rewers-Felkins K.A.; Salguero M.V.; Al-Obaidi I.; Kottapalli K.R.; Vasylyeva T.L. Gut Microbiota-Dependent Trimethylamine-N-oxide and Serum Biomarkers in Patients with T2DM and Advanced CKD. J. Clin. Med. 2017, 6, 86. [CrossRef]

- Fasano A. All disease begins in the (leaky) gut: role of zonulin-mediated gut permeability in the pathogenesis of some chronic inflammatory diseases. F1000Res. 2020, 9, F1000 Faculty Rev-69. [CrossRef]

- Ficek J.; Wyskida K.; Ficek R.; Wajda J.; Klein D.; Witkowicz J.; Rotkegel S.; Spiechowicz-Zatoń U.; Kocemba-Dyczek J.; Ciepał J.; et al. Relationship between plasma levels of zonulin, bacterial lipopolysaccharides, D-lactate and markers of inflammation in haemodialysis patients. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2017, 49, 717-725. [CrossRef]

- Roumeliotis, S.; Mallamaci, F.; Zoccali, C. Endothelial Dysfunction in Chronic Kidney Disease, from Biology to Clinical Outcomes: A 2020 Update. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2359. [CrossRef]

- Ntlahla E.E.; Mfengu M.M.; Engwa G.A.; Nkeh-Chungag B.N.; Sewani-Rusike C.R. Gut permeability is associated with hypertension and measures of obesity but not with Endothelial Dysfunction in South African youth. Afr. Health Sci. 2021, 21, 1172-1184. [CrossRef]

- Loffredo L.; Ivanov V.; Ciobanu N.; Ivanov M.; Ciacci P.; Nocella C.; Cammisotto V.; Orlando F.; Paraninfi A.; Maggio E.; et. al. Low-grade endotoxemia and NOX2 in patients with coronary microvascular angina. Kardiol. Pol. 2022, 80, 911-918. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).