Submitted:

27 September 2024

Posted:

29 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Article Highlights

- Regulatory Role: microRNA-181a can function as an oncogene or a tumor suppressor by post-transcriptionally regulating many mRNA transcripts and non-coding RNAs involved in cancer.

- Aberrant Expression: microRNA-181a is aberrantly expressed in a large majority of cancers contributing to tumor progression, increased proliferation, immune suppression, and apoptosis.

- Clinical Relevance: miR-181a is a pan-cancer biomarker with altered expression profiles that can be detected in the serum of patients.

- Therapeutic Potential: Pre-clinical studies suggest that targeting miR-181a in vivo can inhibit cancer progression and that knockout of miR-181a is not toxic and presents a potentially favorable safety profile. Thus, miR-181a serves as an ideal therapeutic target.

- Immune Microenvironment: miR-181a plays a major role in immune cell development, particularly NK and T-cells, and can influence the tumor microenvironment.

- Next Steps: Development of a therapeutic platform for targeting miR-181a via nanoparticles, natural products, small molecules, or repurposed drugs is presents a polyvalent therapeutic approach to inhibiting cancer progression.

1. Introduction

2. miR-181a Overview

2.1. miR-181 Family

2.2. Genomic Variations of miR-181a

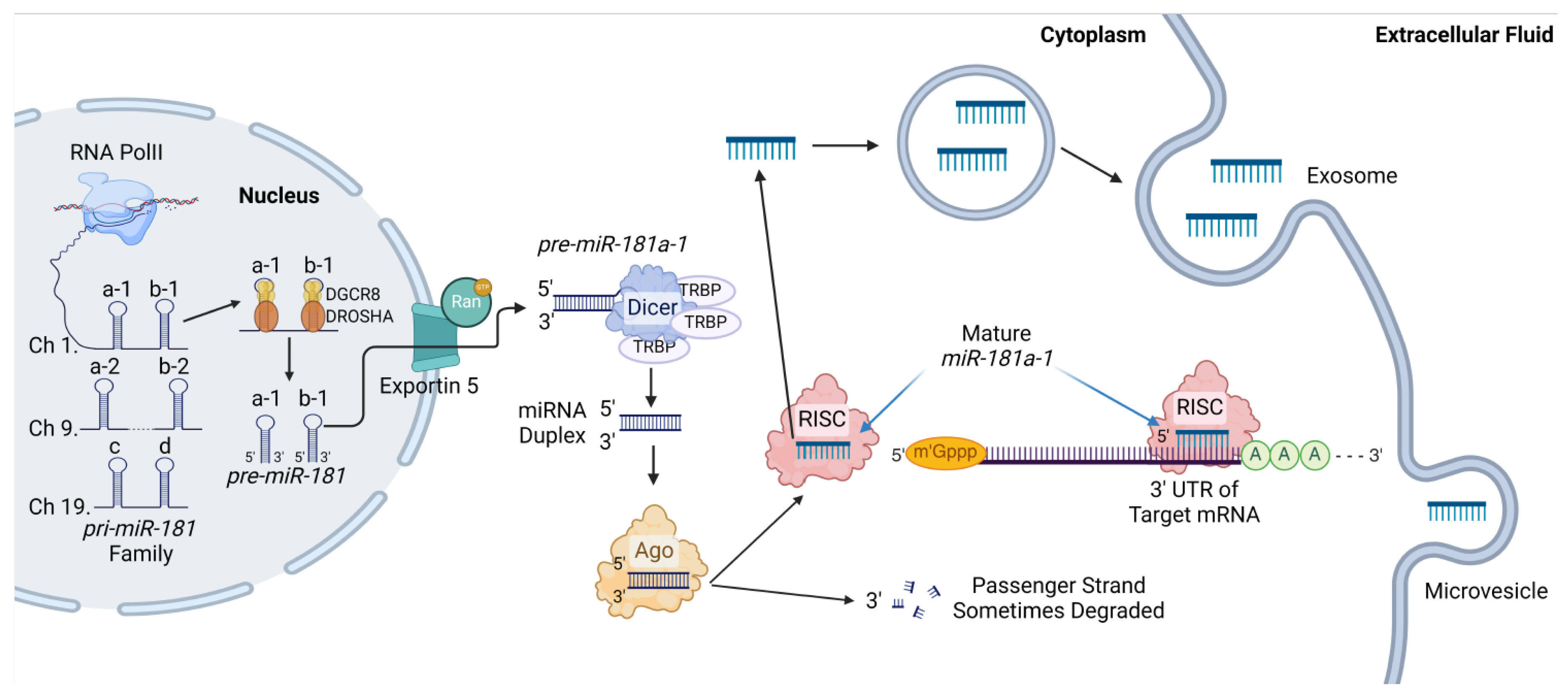

2.3. Canonical and Noncanonical miR-181a Processing

2.4. RNA Binding Protein Interactions with miR-181a

2.5. miR-181a’s Classical Role

3. miR-181a in a Cancer Context

4. Genomic and Epigenetic Changes at the miR-181a Loci in Cancer

4.1. Acetylation Marks

4.2. Methylation Marks

5. Post-Transcriptional Modifications on miR-181a in Cancer

6. Competing Endogenous RNAs with miR-181a in Cancer

7. Signaling Pathways Modulating miR-181a Expression

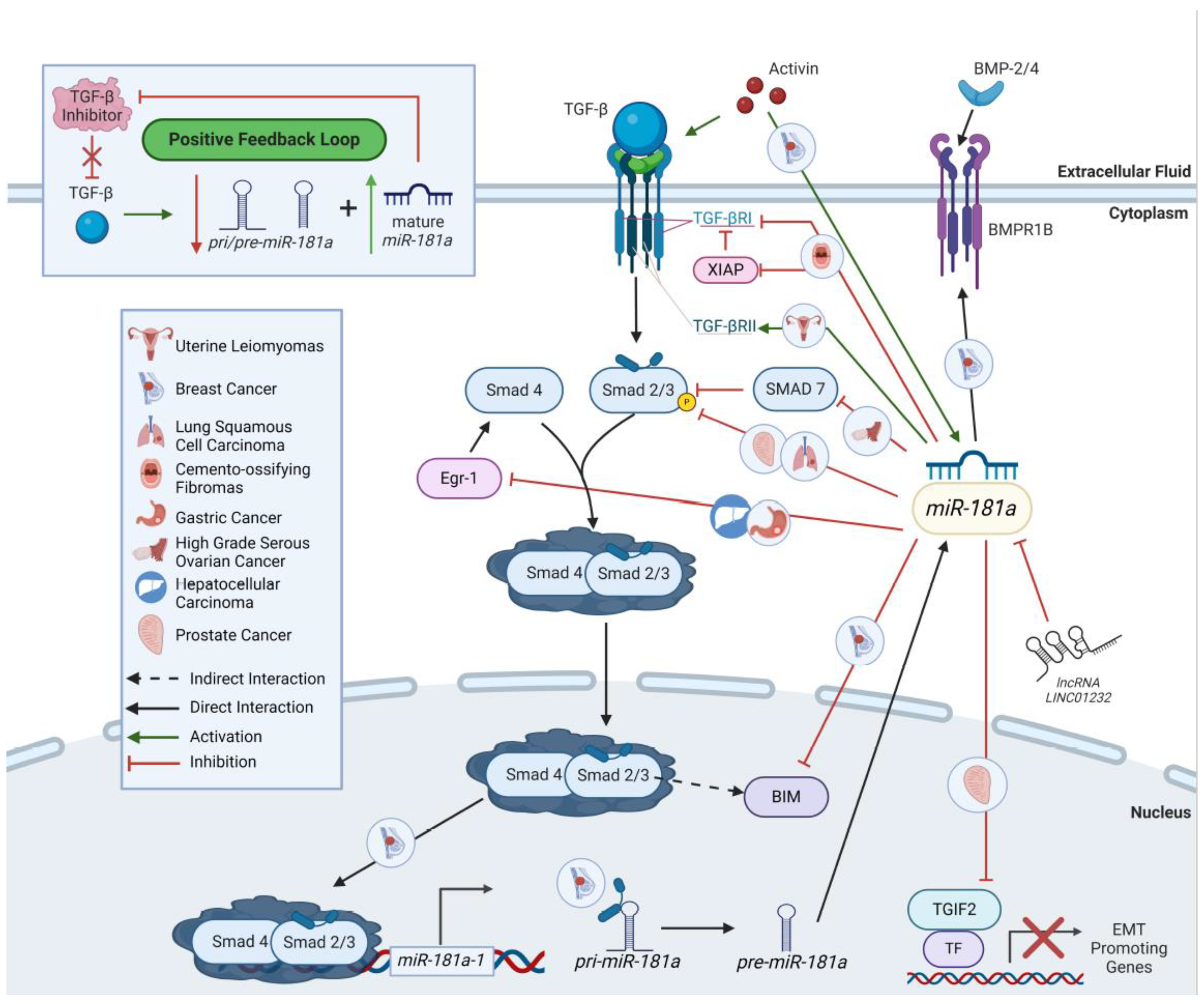

7.1. TGF-β Signaling

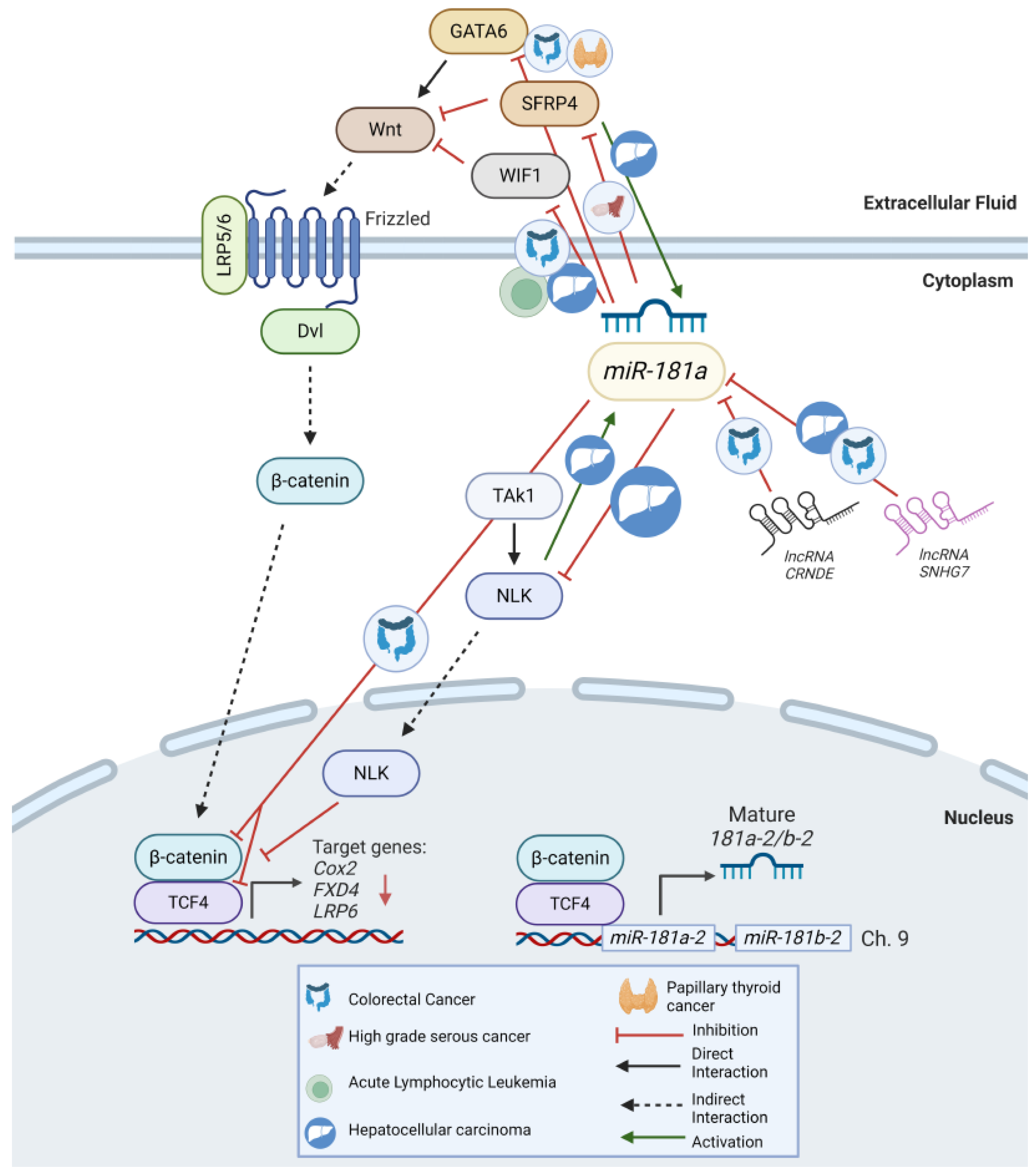

7.2. Wnt Signaling

7.3. STAT Signaling

7.4. SOX2

7.5. HBx

8. Signaling Pathways miR-181a Regulates

8.1. TGF-β

8.2. Wnt/β-Catenin

8.3. Notch

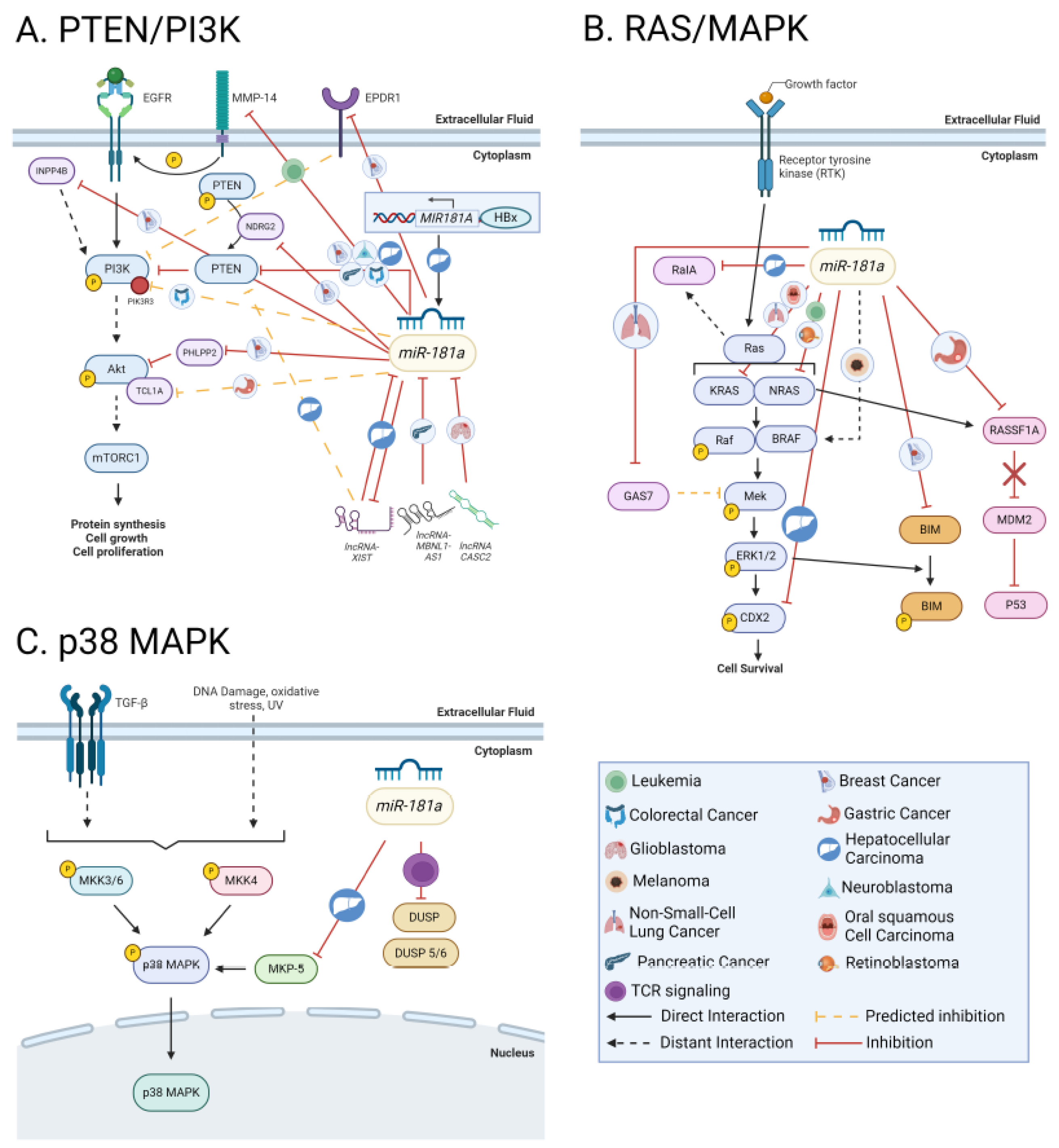

8.4. PTEN-PI3K-AKT-mTOR Network

8.5. RAS/MAPK/ERK

8.5.1. p38 MAPK

8.6. Snail

8.7. Hippo-YAP/TAZ

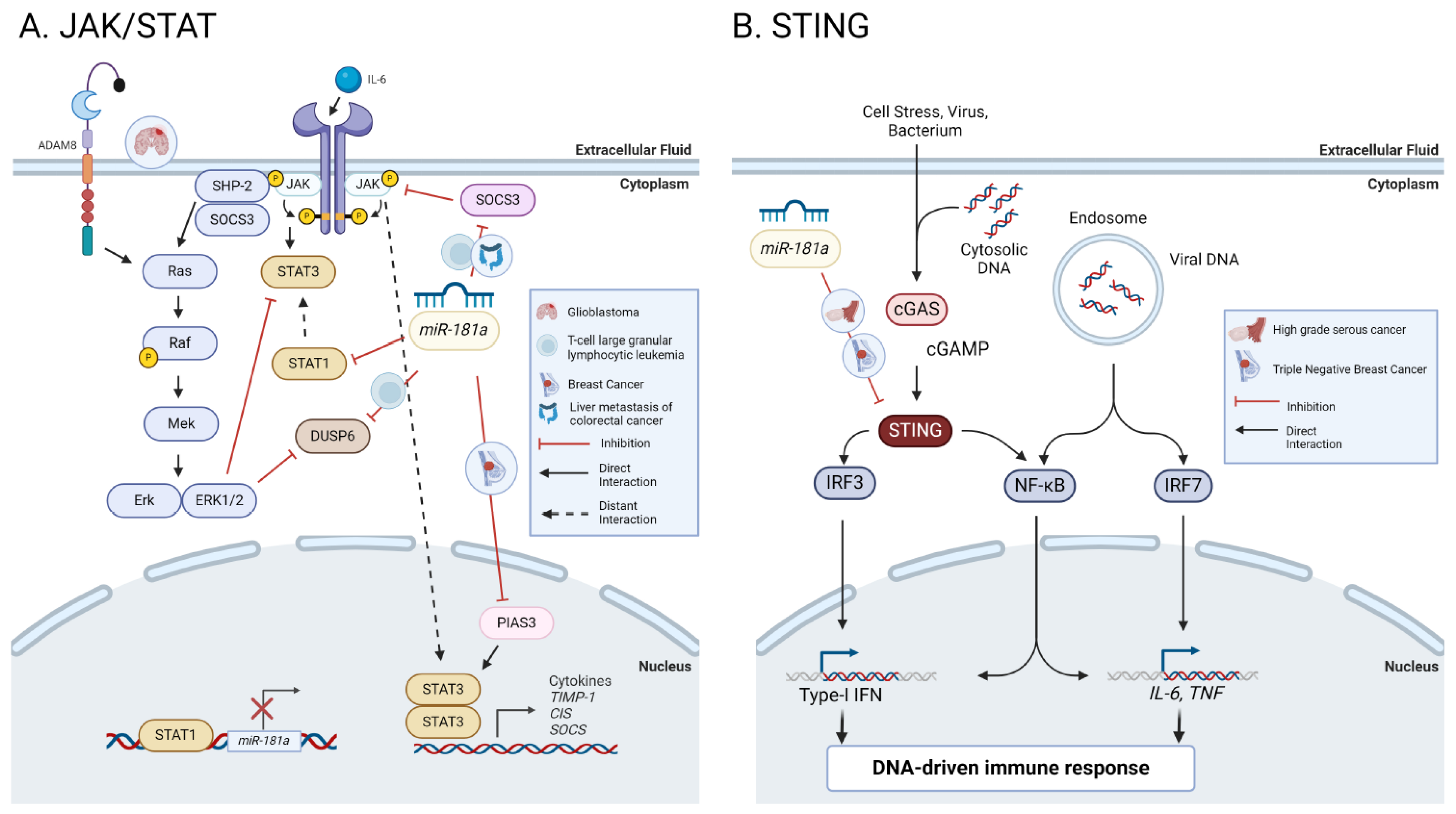

8.8. JAK/STAT

8.9. STING

8.9.1. NF-κβ

10. Immune Microenvironment

10.1. Immune Checkpoints

11. Cell cycle & DNA Repair Regulation

11.1. TP53

11.2. G1/S Regulation

11.3. G2/M Regulation

12. Apoptosis

12.1. BCL-2

12.2. Other Apoptotic Pathways

13. Angiogenesis

14. Hormonal Signaling

15. miR-181a as a Non-Toxic Targetable oncomiR

16. Genetically Engineered miR-181a Murine Models

17. Nanoparticles as a Delivery Platform for miR-181a

18. Pharmacological Inhibition of miR-181a

18.1. Epigenetic Drugs Controlling miR-181a Activity

18.2. Natural Products

18.3. Drug Repurposing

19. miR-181a Governs Cancer Therapeutic Efficacy

19.1. miR-181a Modulates Radiosensitivity

19.2. miR-181a Contributes to Chemotherapy Resistance

20. Concluding Remarks

21. Expert Opinion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Disclosure Statement

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| AFP | Alpha fetoprotein |

| Ago | Argonaut |

| Akt | Protein kinase B |

| ALL | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| AML | Acute myeloid leukemia |

| AS-IV | astragaloside IV |

| ATM | Ataxia telangiectasia mutated protein kinase |

| ATRA | all-trans-retinoic acid |

| BC | Breast cancer |

| BCL-2 | B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2 protein |

| BET | bromodomain and extra-terminal motif |

| CA-AML | Cryogenically normal acute myeloid leukemia |

| CDX2 | Caudal-type homeodomain transcription factor |

| ceRNAs | Competing endogenous RNAs |

| cGAS | Cyclic GMP AMP Synthase |

| cirRNAs | Circular RNAs |

| CLL | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia |

| CML | Chronic myelogenous leukemia |

| COAD | Colon adenocarcinoma |

| COFs | Cemento-ossifying fibromas |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| CSC | Cancer stem cell |

| DACT2 | Disheveled binding antagonist of beta-catenin 2 |

| DLBCL | Diffuse Large B-Cell Leukemia |

| DNMTi | DNA methyltransferase inhibitor |

| EGF | Epidermal growth factor |

| Egr1 | Early growth response factor 1 |

| EMT | Epithelial to mesenchymal transition |

| EOlC | Epithelial ovarian cancer |

| EpCAM | epithelial cellular adhesion molecule |

| EPDR1 | Ependymin Related 1 proteinn |

| ER | Estrogen receptor |

| ERAD | endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation |

| ERK2 | ERK mRNA |

| ESR1 | Estrogen receptor 1 |

| FGF | Fibroblast growth factor |

| FTSEC | Fallopian tube secretory cells |

| GAS7 | Growth arrest specific-7 |

| GC | Gastric cancer |

| GEMM | Genetically engineered mouse model |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HDACi | Histone deacetylase inhibitor |

| HGSC | High-grade serous cancer |

| IFN | Interferon |

| IGF2BP1 | Insulin Like Growth Factor2 mRNA Binding Protein 1 |

| IKKε | IKK-inducible kinase |

| IM | imatinib mesylate |

| INPP5A | Inositol Polyphosphate-5-Phosphatase A |

| IRF3 | Interferon regulatory factor 3 |

| JAK | Janus kinase |

| kb | kilobases |

| lncRNAs | Long non-coding RNAs |

| LUSC | Lung squamous cell carcinoma |

| MET | Mesenchymal to epithelial transition |

| MHC | Major histone compatibility complex |

| MIIP | Migration and invasion inhibitory protein |

| miR-181 | microRNA 181 |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| MKP-5 | MAPK phosphatase 5 |

| MMP | Matrix metallopronteinase |

| MRE | microRNA recognition element |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| NB | Neuroblastoma |

| NDRG2 | N-myc downstream regulated gene 2 |

| NF-κβ | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| NK | Natural Killer Cells |

| NLK | Nemo-like kinase |

| NP | Nanoparticle |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| nt | Nucleotides |

| PaCa | Pancreatic cancer |

| PAM | PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway |

| PARP1 | Poly[ADP-ribose] polymerase 1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed cell death ligand 1 |

| PGR | Progesterone Receptor |

| PI3K | phosphoinositide-3-kinase |

| PN | Pinostrobin |

| PolII | RNA polymerase II |

| PrCa | Prostate caner |

| pri-miRNA | Primary microRNA |

| PTC | Papillary thyroid cancer |

| RBP | RNA binding proteins |

| RISC | RNA-induced silencing complex |

| RTK | Receptor tyrosine kinase |

| RV | Resveratrol |

| SNP | Single nucleotide polymorphism |

| SNV | Single nucleotide variation |

| SRCIN1 | Src kinase signaling inhibitor 1 |

| STAT | Signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| STING | Stimulator of interferon gene |

| SYNCRIP | Synaptotagmin-binding Cytoplasmic RNA-Interacting Protein |

| T-ALL | T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| TAZ | Transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| TCR | T-cell receptor |

| TFs | Transcription factors |

| TGF-β | Canonical transforming growth factor-β |

| TKI | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor |

| T-LGL | T-cell large granular lymphocyte |

| TMBIM6 | Transmembrane Bax Inhibitor Motif-containing 6 |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TNBC | Triple negative breast cancer |

| T-PLL | T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia |

| TRIM5 | Tripartite Motif Containing 5 |

| UPR | Unfolded protein response |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| WIF1 | Wnt inhibitory factor 1 |

| XIST | X-inactivated specific transcript |

| YAP | Yes-associated protein |

References

- Vishnoi, A.; Rani, S. MiRNA Biogenesis and Regulation of Diseases: An Overview. Methods Mol Biol. 2017, 1509, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Okamura, K.; Hagen, J.W.; Duan, H.; et al. The mirtron pathway generates microRNA-class regulatory RNAs in Drosophila. Cell. 2007, 130, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, F.; Pagotto, S.; Soliman, S.; et al. Regulation of miR-483-3p by the O-linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase links chemosensitivity to glucose metabolism in liver cancer cells. Oncogenesis. 2017, 6, e328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veronese, A.; Visone, R.; Consiglio, J.; et al. Mutated beta-catenin evades a microRNA-dependent regulatory loop. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011, 108, 4840–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell-Hensley, A.; Das, S.; McAlinden, A. The miR-181 family: Wide-ranging pathophysiological effects on cell fate and function. J Cell Physiol. 2023, 238, 698–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004, 116, 281–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamanu, T.K.; Radovanovic, A.; Archer, J.A.; et al. Exploration of miRNA families for hypotheses generation. Sci Rep. 2013, 3, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olena, A.F.; Patton, J.G. Genomic organization of microRNAs. J Cell Physiol. 2010, 222, 540–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annese, T.; Tamma, R.; De Giorgis, M.; et al. microRNAs Biogenesis, Functions and Role in Tumor Angiogenesis. Front Oncol. 2020, 10, 581007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.P.; Glasner, M.E.; Yekta, S.; et al. Vertebrate microRNA genes. Science. 2003, 299, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagos-Quintana, M.; Rauhut, R.; Meyer, J.; et al. New microRNAs from mouse and human. RNA. 2003, 9, 175–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dostie, J.; Mourelatos, Z.; Yang, M.; et al. Numerous microRNPs in neuronal cells containing novel microRNAs. RNA. 2003, 9, 180–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presnell, S.R.; Al-Attar, A.; Cichocki, F.; et al. Human natural killer cell microRNA: differential expression of MIR181A1B1 and MIR181A2B2 genes encoding identical mature microRNAs. Genes Immun. 2015, 16, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozomara, A.; Birgaoanu, M.; Griffiths-Jones, S. miRBase: from microRNA sequences to function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D155–D162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheyden, N.A.; Klostermann, M.; Brüggemann, M.; et al. A high-resolution map of functional miR-181 response elements in the thymus reveals the role of coding sequence targeting and an alternative seed match. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024 May 23.

- Wingo, A.P.; Almli, L.M.; Stevens, J.S.; et al. Genome-wide association study of positive emotion identifies a genetic variant and a role for microRNAs. Mol Psychiatry. 2017, 22, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Yao, Q.; Han, J.; et al. SNP rs322931 (C>T) in miR-181b and rs7158663 (G>A) in MEG3 aggravate the inflammatory response of anal abscess in patients with Crohn's disease. Aging (Albany NY). 2022, 14, 3313–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.L.; Yang, J.; Zeng, Z.N.; et al. Interaction of miR-181b and. Biomed Res Int. 2020, 2020, 4757065. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, C.; et al. Association between MEG3/miR-181b polymorphisms and risk of ischemic stroke. Lipids Health Dis. 2018, 17, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhu, P.; Wang, Y.; et al. miR-181a targets PTEN to mediate the neuronal injury caused by oxygen-glucose deprivation and reoxygenation. Metab Brain Dis. 2023, 38, 2077–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, T.M.; Ihssen, N.; Brindley, L.M.; et al. Further support for association between GWAS variant for positive emotion and reward systems. Transl Psychiatry. 2017, 7, e1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Korany, W.A.; Zahran, W.E.; Alm El-Din, M.A.; et al. Rs12039395 Variant Influences the Expression of hsa-miR-181a-5p and PTEN Toward Colorectal Cancer Risk. Dig Dis Sci. 2024 Jun 28.

- Liu, G.; Min, H.; Yue, S.; et al. Pre-miRNA loop nucleotides control the distinct activities of mir-181a-1 and mir-181c in early T cell development. PLoS One. 2008, 3, e3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chira, S.; Ciocan, C.; Bica, C.; et al. Artificial miRNAs derived from miR-181 family members have potential in cancer therapy due to an altered spectrum of target mRNAs. FEBS Lett. 2023, 597, 1989–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, R.A.; Zhang, Q.C.; Spitale, R.C.; et al. Transcriptome-wide interrogation of RNA secondary structure in living cells with icSHAPE. Nat Protoc. 2016, 11, 273–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.J.; Zhang, J.; Li, P.; et al. RNA structure probing reveals the structural basis of Dicer binding and cleavage. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, A.; Gurtan, A.M.; Kumar, M.S.; et al. Proliferation and tumorigenesis of a murine sarcoma cell line in the absence of DICER1. Cancer Cell. 2012, 21, 848–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Kim, B.; Kim, V.N. Re-evaluation of the roles of DROSHA, Export in 5, and DICER in microRNA biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016, 113, E1881–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, S.Y.; Ta, M.; et al. Biallelic Dicer1 Mutations in the Gynecologic Tract of Mice Drive Lineage-Specific Development of DICER1 Syndrome-Associated Cancer. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 3517–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeary, S.E.; Lin, K.S.; Shi, C.Y.; et al. The biochemical basis of microRNA targeting efficacy. Science. 2019, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.Y.; Lin, Y.C.; Cui, S.; et al. miRTarBase update 2022: an informative resource for experimentally validated miRNA-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D222–D230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccioni, V.; Trionfetti, F.; Montaldo, C.; et al. SYNCRIP Modulates the Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Hepatocytes and HCC Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Gao, L.; et al. MiR-181 mediates cell differentiation by interrupting the Lin28 and let-7 feedback circuit. Cell Death Differ. 2012, 19, 378–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunze-Schumacher, H.; Krueger, A. The Role of MicroRNAs in Development and Function of Regulatory T Cells - Lessons for a Better Understanding of MicroRNA Biology. Front Immunol. 2020, 11, 2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrieri, A.; Carrella, S.; Carotenuto, P.; et al. The Pervasive Role of the miR-181 Family in Development, Neurodegeneration, and Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Passos Gibson, V.; Hardy, P. The Role of MiR-181 Family Members in Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and Tumor Angiogenesis. Cells. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel-Hett, S.; D'Amore, P.A. Signal transduction in vasculogenesis and developmental angiogenesis. Int J Dev Biol. 2011, 55, 353–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazenwadel, J.; Michael, M.Z.; Harvey, N.L. Prox1 expression is negatively regulated by miR-181 in endothelial cells. Blood. 2010, 116, 2395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrella, S.; Barbato, S.; D'Agostino, Y.; et al. TGF-β Controls miR-181/ERK Regulatory Network during Retinal Axon Specification and Growth. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0144129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, R.; Grünhagen, J.; Becker, J.; et al. miR-181a promotes osteoblastic differentiation through repression of TGF-β signaling molecules. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013, 45, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Gao, Y.; Xu, M.Q.; et al. miR-181a regulate porcine preadipocyte differentiation by targeting TGFBR1. Gene. 2019, 681, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knarr, M.; Nagaraj, A.B.; Kwiatkowski, L.J.; et al. miR-181a modulates circadian rhythm in immortalized bone marrow and adipose derived stromal cells and promotes differentiation through the regulation of PER3. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, D.; Xu, L.; Zhang, L.; et al. MiR-181a-5p regulates 3T3-L1 cell adipogenesis by targeting Smad7 and Tcf7l2. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2016, 48, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Liu, J.; Tycksen, E.; et al. MicroRNA-181a/b-1 over-expression enhances osteogenesis by modulating PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling and mitochondrial metabolism. Bone. 2019, 123, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Ye, Z.; Weyand, C.M.; et al. miR-181a-regulated pathways in T-cell differentiation and aging. Immun Ageing. 2021, 18, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.J.; Chau, J.; Ebert, P.J.; et al. miR-181a is an intrinsic modulator of T cell sensitivity and selection. Cell. 2007, 129, 147–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordino, G.; Costa-Pereira, S.; Corredeira, P.; et al. MicroRNA-181a restricts human γδ T cell differentiation by targeting Map3k2 and Notch2. EMBO Rep. 2022, 23, e52234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichocki, F.; Felices, M.; McCullar, V.; et al. Cutting edge: microRNA-181 promotes human NK cell development by regulating Notch signaling. J Immunol. 2011, 187, 6171–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Li, S.; Li, X.; et al. Declined miR-181a-5p expression is associated with impaired natural killer cell development and function with aging. Aging Cell. 2021, 20, e13353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rady, M.; Watzl, C.; Claus, M.; et al. Altered expression of miR-181a and miR-146a does not change the expression of surface NCRs in human NK cells. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 41381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Lin, H.S.; Zhang, X.H.; et al. MiR-181 family: regulators of myeloid differentiation and acute myeloid leukemia as well as potential therapeutic targets. Oncogene. 2015, 34, 3226–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, T.; Hejazi, M.; Mansoori, B.; et al. microRNA-181a mediates the chemo-sensitivity of glioblastoma to carmustine and regulates cell proliferation, migration, and apoptosis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020, 888, 173483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, J.; et al. hsa-mir-181a and hsa-mir-181b function as tumor suppressors in human glioma cells. Brain Res. 2008, 1236, 185–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, X.; Li, J.; Yun, X.; et al. miR-181a-5p, an inducer of Wnt-signaling, facilitates cell proliferation in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncol Rep. 2017, 37, 1469–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simiene, J.; Dabkeviciene, D.; Stanciute, D.; et al. Potential of miR-181a-5p and miR-630 as clinical biomarkers in NSCLC. BMC Cancer. 2023, 23, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadaki, C.; Monastirioti, A.; Rounis, K.; et al. Circulating MicroRNAs Regulating DNA Damage Response and Responsiveness to Cisplatin in the Prognosis of Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated with First-Line Platinum Chemotherapy. Cancers (Basel). 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbato, A.; Iuliano, A.; Volpe, M.; et al. Integrated Genomics Identifies miR-181/TFAM Pathway as a Critical Driver of Drug Resistance in Melanoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Guo, S.; Tong, S.; et al. Identification of Keratinocyte Differentiation-Involved Genes for Metastatic Melanoma by Gene Expression Profiles. Comput Math Methods Med. 2021, 2021, 9652768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, K.H.; Bae, S.D.; Hong, H.S.; et al. miR-181a shows tumor suppressive effect against oral squamous cell carcinoma cells by downregulating K-ras. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011, 404, 896–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, M.; Liu, G.; Xiong, C.; et al. microRNA-181a-5p impedes the proliferation, migration, and invasion of retinoblastoma cells by targeting the NRAS proto-oncogene. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2022, 77, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zhou, D.; Yan, G.; et al. Correlation of miR-181a and three HOXA genes as useful biomarkers in acute myeloid leukemia. Int J Lab Hematol. 2020, 42, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadbad, M.A.; Baradaran, B. hsa-miR-181a-5p inhibits glioblastoma development via the MAPK pathway: in-silico and in-vitro study. Oncology Research.

- Király, J.; Szabó, E.; Fodor, P.; et al. Expression of hsa-miRNA-15b, -99b, -181a and Their Relationship to Angiogenesis in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Biomedicines. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.Y.; Chen, J.C.; Jiao, T.T.; et al. MicroRNA-181 targets Yin Yang 1 expression and inhibits cervical cancer progression. Mol Med Rep. 2015, 11, 4541–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Li, X.; Wu, Z.; et al. DNA methylation-mediated repression of miR-181a/135a/302c expression promotes the microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancer development and 5-FU resistance via targeting PLAG1. J Genet Genomics. 2018, 45, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallis, S.P.; Kim, S.K.; Lee, J.H.; et al. Association of NRF2 with HIF-2α-induced cancer stem cell phenotypes in chronic hypoxic condition. Redox Biol. 2023, 60, 102632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozloski, G.A.; Jiang, X.; Bhatt, S.; et al. miR-181a negatively regulates NF-κB signaling and affects activated B-cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma pathogenesis. Blood. 2016, 127, 2856–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandrova, E.; Lamberti, J.; Saggese, P.; et al. Small Non-Coding RNA Profiling Identifies miR-181a-5p as a Mediator of Estrogen Receptor Beta-Induced Inhibition of Cholesterol Biosynthesis in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cells. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, R.; Papulino, C.; Sgueglia, G.; et al. Regulatory Interplay between miR-181a-5p and Estrogen Receptor Signaling Cascade in Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustos, M.A.; Yokoe, T.; Shoji, Y.; et al. MiR-181a targets STING to drive PARP inhibitor resistance in BRCA- mutated triple-negative breast cancer and ovarian cancer. Cell Biosci. 2023, 13, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, R.; et al. Cancer exosome-derived miR-9 and miR-181a promote the development of early-stage MDSCs via interfering with SOCS3 and PIAS3 respectively in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2020, 39, 4681–4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouladi, H.; Ebrahimi, A.; Derakhshan, S.M.; et al. Over-expression of mir-181a-3p in serum of breast cancer patients as diagnostic biomarker. Mol Biol Rep. 2024, 51, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Mu, T.; Zhao, L.; et al. MiR-181a-5p facilitates proliferation, invasion, and glycolysis of breast cancer through NDRG2-mediated activation of PTEN/AKT pathway. Bioengineered. 2022, 13, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Lin, S.; Wen, Z.; et al. Testing the accuracy of a four serum microRNA panel for the detection of primary bladder cancer: a discovery and validation study. Biomarkers. 2024, 29, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh, A.; Lee, C.; Joseph, P.; et al. microRNA-181a has a critical role in ovarian cancer progression through the regulation of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Commun. 2014, 5, 2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrillo, M.; Zannoni, G.F.; Beltrame, L.; et al. Identification of high-grade serous ovarian cancer miRNA species associated with survival and drug response in patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a retrospective longitudinal analysis using matched tumor biopsies. Ann Oncol. 2016, 27, 625–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panoutsopoulou, K.; Avgeris, M.; Magkou, P.; et al. miR-181a overexpression predicts the poor treatment response and early-progression of serous ovarian cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2020, 147, 3560–3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; Li, X.; Zhu, H.; et al. Expression of miR-181a in Circulating Tumor Cells of Ovarian Cancer and Its Clinical Application. ACS Omega. 2021, 6, 22011–22019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geletina, N.S.; Kobelev, V.S.; Babayants, E.V.; et al. PTEN negative correlates with miR-181a in tumour tissues of non-obese endometrial cancer patients. Gene. 2018, 655, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.; Chen, Z.; Li, M.; et al. MicroRNA-181a promotes tumor growth and liver metastasis in colorectal cancer by targeting the tumor suppressor WIF-1. Mol Cancer. 2014, 13, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Mi, Y.; Zheng, B.; et al. Highly-metastatic colorectal cancer cell released miR-181a-5p-rich extracellular vesicles promote liver metastasis by activating hepatic stellate cells and remodelling the tumour microenvironment. J Extracell Vesicles. 2022, 11, e12186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, J.; Handa, R.; Yamamoto, H.; et al. microRNA-181a is associated with poor prognosis of colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2012, 28, 2221–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, M.; Winter, E.; Ress, A.L.; et al. miR-181a is associated with poor clinical outcome in patients with colorectal cancer treated with EGFR inhibitor. J Clin Pathol. 2014, 67, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, X.; Liu, C.; et al. miR-181a-2-3p Stimulates Gastric Cancer Progression. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 687915. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, Y.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, W.; et al. miR-181a-5p promotes the progression of gastric cancer via RASSF6-mediated MAPK signalling activation. Cancer Lett. 2017, 389, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, J. Ascites-derived hsa-miR-181a-5p serves as a prognostic marker for gastric cancer-associated malignant ascites. BMC Genomics. 2024, 25, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.X.; Zhang, M.Y. ; Rui Li, et al. Serum miR-1228-3p and miR-181a-5p as Noninvasive Biomarkers for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Diagnosis and Prognosis. Biomed Res Int. 2020, 2020, 9601876. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Dong, D.; Pan, C.; et al. Identification of Grade-associated MicroRNAs in Brainstem Gliomas Based on Microarray Data. J Cancer. 2018, 9, 4463–4476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiang, P.; Pan, Q.; Fang, C.; et al. MicroRNA-181a-3p as a Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarker for Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2020, 12, e2020012. [Google Scholar]

- Debernardi, S.; Skoulakis, S.; Molloy, G.; et al. MicroRNA miR-181a correlates with morphological sub-class of acute myeloid leukaemia and the expression of its target genes in global genome-wide analysis. Leukemia. 2007, 21, 912–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.; Vaiselbuh, S.R. Vincristine and prednisone regulates cellular and exosomal miR-181a expression differently within the first time diagnosed and the relapsed leukemia B cells. Leuk Res Rep. 2020, 14, 100221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.; Vaiselbuh, S.R. Silencing of Exosomal miR-181a Reverses Pediatric Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia Cell Proliferation. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.X.; Zhu, W.; Fang, C.; et al. miR-181a/b significantly enhances drug sensitivity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells via targeting multiple anti-apoptosis genes. Carcinogenesis. 2012, 33, 1294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J.; Gusev, Y.; Jiang, J.; et al. Expression profiling identifies microRNA signature in pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007, 120, 1046–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.; Chen, B.; Wang, X.; et al. Long non-coding RNA XIST regulates PTEN expression by sponging miR-181a and promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression. BMC Cancer. 2017, 17, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, F.; Luo, P.; Yang, Q.O.; et al. MiR-181a promotes growth of thyroid cancer cells by targeting tumor suppressor RB1. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017, 21, 5638–5647. [Google Scholar]

- Knarr, M.; Avelar, R.A.; Sekhar, S.C.; et al. miR-181a initiates and perpetuates oncogenic transformation through the regulation of innate immune signaling. Nat Commun. 2020, 11, 3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiechert, A.; Saygin, C.; Thiagarajan, P.S.; et al. Cisplatin induces stemness in ovarian cancer. Oncotarget. 2016, 7, 30511–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belur Nagaraj, A.; Joseph, P.; Ponting, E.; et al. A miRNA-Mediated Approach to Dissect the Complexity of Tumor-Initiating Cell Function and Identify miRNA-Targeting Drugs. Stem Cell Reports. 2019, 12, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belur Nagaraj, A.; Knarr, M.; Sekhar, S.; et al. The miR-181a-SFRP4 Axis Regulates Wnt Activation to Drive Stemness and Platinum Resistance in Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 2044–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perepechaeva, M.L.; Studenikina, A.A.; Grishanova, A.Y.; et al. Serum miR-181a and miR-25 in patients with malignant and benign breast diseases. Biomed Khim. 2023, 69, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, L.; Ma, X.; Zhang, N.; et al. Targeting Oncogenic miR-181a-2-3p Inhibits Growth and Suppresses Cisplatin Resistance of Gastric Cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2021, 13, 8599–8609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisso, A.; Faleschini, M.; Zampa, F.; et al. Oncogenic miR-181a/b affect the DNA damage response in aggressive breast cancer. Cell Cycle. 2013, 12, 1679–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaan, Z.; Rai, S.N.; Eichenberger, M.R.; et al. Differential microRNA expression tracks neoplastic progression in inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal cancer. Hum Mutat. 2012, 33, 551–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, C.; Feng, M.; Yin, Z.; et al. RalA, a GTPase targeted by miR-181a, promotes transformation and progression by activating the Ras-related signaling pathway in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Oncotarget. 2016, 7, 20561–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marco, C.; Zoppoli, P.; Rinaldo, N.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of copy number alterations led to the characterisation of PDCD10 as oncogene in ovarian cancer. Transl Oncol. 2021, 14, 101013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.C.; Birkbak, N.J.; Culhane, A.C.; et al. Profiles of genomic instability in high-grade serous ovarian cancer predict treatment outcome. Clin Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 5806–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimova, I.; Orsetti, B.; Negre, V.; et al. Genomic markers for ovarian cancer at chromosomes 1, 8 and 17 revealed by array CGH analysis. Tumori. 2009, 95, 357–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lionetti, M.; Musto, P.; Di Martino, M.T.; et al. Biological and clinical relevance of miRNA expression signatures in primary plasma cell leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 3130–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, J.; Zhou, R.; et al. Gene silencing of MIR22 in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia involves histone modifications independent of promoter DNA methylation. Br J Haematol. 2010, 148, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.R.; Humphreys, K.J.; Simpson, K.J.; et al. Functional high-throughput screen identifies microRNAs that promote butyrate-induced death in colorectal cancer cells. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2022, 30, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhao, M.; et al. The central role of EED in the orchestration of polycomb group complexes. Nat Commun. 2014, 5, 3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, L.A.; Plath, K.; Zeitlinger, J.; et al. Polycomb complexes repress developmental regulators in murine embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2006, 441, 349–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Mani, R.S.; Ateeq, B.; et al. Coordinated regulation of polycomb group complexes through microRNAs in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011, 20, 187–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V.; Purkait, S.; Takkar, S.; et al. Analysis of EZH2: micro-RNA network in low and high grade astrocytic tumors. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2016, 33, 117–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, S.; Monzo, M.; Navarro, A. Epigenetic regulation mechanisms of microRNA expression. Biomol Concepts 2017, 8, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lujambio, A.; Calin, G.A.; Villanueva, A.; et al. A microRNA DNA methylation signature for human cancer metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008, 105, 13556–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Ma, Y.L.; Zhang, P.; et al. SP1 mediates the link between methylation of the tumour suppressor miR-149 and outcome in colorectal cancer. J Pathol. 2013, 229, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, E.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. EpimiR: a database of curated mutual regulation between miRNAs and epigenetic modifications. Database (Oxford). 2014, 2014, bau023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konno, M.; Koseki, J.; Asai, A.; et al. Distinct methylation levels of mature microRNAs in gastrointestinal cancers. Nat Commun. 2019, 10, 3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Cheng, T.; Du, Y.; et al. LncRNA LUCAT1/miR-181a-5p axis promotes proliferation and invasion of breast cancer via targeting KLF6 and KLF15. BMC Mol Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Shen, C.; Zhang, Y.; et al. LncRNA ANRIL negatively regulated chitooligosaccharide-induced radiosensitivity in colon cancer cells by sponging miR-181a-5p. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2021, 30, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, L. SNHG7 Contributes to the Progression of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer via the SNHG7/miR-181a-5p/E2F7 Axis. Cancer Manag Res. 2020, 12, 3211–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Long, Z. LncRNA LINC01232 Enhances Proliferation, Angiogenesis, Migration and Invasion of Colon Adenocarcinoma Cells by Downregulating miR-181a-5p. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2023, 33, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, A.; Wang, W.; Gu, C.; et al. Long non-coding RNA CCAT1 promotes colorectal cancer progression by regulating miR-181a-5p expression. Aging (Albany NY). 2020, 12, 8301–8320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Chen, K.; Chen, P.; et al. Downregulation of LncRNA SNHG7 Sensitizes Colorectal Cancer Cells to Resist Anlotinib by Regulating miR-181a-5p/GATA6. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2023, 2023, 6973723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Jiang, L.; Gao, Y.; et al. LncRNA CCAT1 negatively regulates miR-181a-5p to promote endometrial carcinoma cell proliferation and migration. Exp Ther Med. 2019, 17, 4259–4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Hua, M.; Zhang, N. LINC01232 promotes lung squamous cell carcinoma progression through modulating miR-181a-5p/SMAD2 axis. Am J Med Sci. 2023, 365, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, S.E.; Abdelfattah, S.N.; Hasona, N.A. Crosstalk Between Long Non-coding RNA MALAT1, miRNA-181a, and IL-17 in Cirrhotic Patients and Their Possible Correlation SIRT1/NF-Ƙβ Axis. Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry. 2024 2024/03/26.

- Ding, X.; Xu, X.; He, X.F.; et al. Muscleblind-like 1 antisense RNA 1 inhibits cell proliferation, invasion, and migration of prostate cancer by sponging miR-181a-5p and regulating PTEN/PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling. Bioengineered. 2021, 12, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Shen, L.; Zhao, H.; et al. LncRNA CASC2 Interacts With miR-181a to Modulate Glioma Growth and Resistance to TMZ Through PTEN Pathway. J Cell Biochem. 2017, 118, 1889–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Liu, X.; Cen, A.; et al. HYPOXIA induces lncRNA HOTAIR for recruiting RELA in papillary thyroid cancer cells to upregulate miR-181a and promote angiogenesis. J Endocrinol Invest. 2024 May 15.

- Brockhausen, J.; Tay, S.S.; Grzelak, C.A.; et al. miR-181a mediates TGF-β-induced hepatocyte EMT and is dysregulated in cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer. Liver Int. 2015, 35, 240–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Huang, Y.; Yang, X. TGF-β promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of liver cancer Huh-7 cells by regulating MiR-182/CADM1. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research; 2023.

- Taylor, M.A.; Sossey-Alaoui, K.; Thompson, C.L.; et al. TGF-β upregulates miR-181a expression to promote breast cancer metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2013, 123, 150–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Tsuyada, A.; et al. Transforming growth factor-β regulates the sphere-initiating stem cell-like feature in breast cancer through miRNA-181 and ATM. Oncogene. 2011, 30, 1470–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neel, J.C.; Lebrun, J.J. Activin and TGFβ regulate expression of the microRNA-181 family to promote cell migration and invasion in breast cancer cells. Cell Signal. 2013, 25, 1556–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Sun, H.; Jiang, Y.; et al. MicroRNA-181a suppresses mouse granulosa cell proliferation by targeting activin receptor IIA. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e59667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, J.; Yamashita, T.; Wang, X.W. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling activates microRNA-181 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Biosci. 2011, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Wang, X.W. New kids on the block: diagnostic and prognostic microRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009, 8, 1686–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, J.; Yamashita, T.; Budhu, A.; et al. Identification of microRNA-181 by genome-wide screening as a critical player in EpCAM-positive hepatic cancer stem cells. Hepatology. 2009, 50, 472–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Lopez McDonald, M.C.; Kim, C.; et al. The complementary roles of STAT3 and STAT1 in cancer biology: insights into tumor pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1265818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Tan, F.; et al. STAT1 Inhibits MiR-181a Expression to Suppress Colorectal Cancer Cell Proliferation Through PTEN/Akt. J Cell Biochem. 2017, 118, 3435–3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Yao, K.; Guo, J.; et al. miR-181a and miR-150 regulate dendritic cell immune inflammatory responses and cardiomyocyte apoptosis via targeting JAK1-STAT1/c-Fos pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2017, 21, 2884–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belotte, J.; Fletcher, N.M.; Alexis, M.; et al. Sox2 gene amplification significantly impacts overall survival in serous epithelial ovarian cancer. Reprod Sci. 2015, 22, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Futtner, C.; Rock, J.R.; et al. Evidence that SOX2 overexpression is oncogenic in the lung. PLoS One. 2010, 5, e11022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Xie, F.; Gao, A.; et al. SOX2 regulates multiple malignant processes of breast cancer development through the SOX2/miR-181a-5p, miR-30e-5p/TUSC3 axis. Mol Cancer. 2017, 16, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaňhara, P.; Horak, P.; Pils, D.; et al. Loss of the oligosaccharyl transferase subunit TUSC3 promotes proliferation and migration of ovarian cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2013, 42, 1383–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pils, D.; Horak, P.; Vanhara, P.; et al. Methylation status of TUSC3 is a prognostic factor in ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2013, 119, 946–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, K.; Edmiston, S.N.; Tse, C.K.; et al. Racial variation in breast tumor promoter methylation in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015, 24, 921–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Xiao, X.; Gong, X.; et al. HBx promotes cell proliferation by disturbing the cross-talk between miR-181a and PTEN. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 40089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massagué, J. TGFbeta in Cancer. Cell. 2008, 134, 215–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaei, T.; Amini, M.; Hashemi, Z.S.; et al. microRNA-181 serves as a dual-role regulator in the development of human cancers. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020, 152, 432–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, M.; Li, Y.; Ye, S.; et al. MicroRNA profiling implies new markers of chemoresistance of triple-negative breast cancer. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e96228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autenshlyus, A.I.; Perepechaeva, M.L.; Studenikina, A.A.; et al. Serum miR-181а and miR-25 Levels in Patients with Breast Cancer or Benign Breast Disease. Dokl Biochem Biophys. 2023, 512, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Tabatabaei, S.N.; Ruan, X.; et al. The Dual Regulatory Role of MiR-181a in Breast Cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017, 44, 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azadeh, M.; Salehzadeh, A.; Ghaedi, K.; et al. Integrated High-Throughput Bioinformatics (Microarray, RNA-Seq, and RNA Interaction) and qRT-PCR Investigation of. Adv Biomed Res. 2023, 12, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Zhou, W.; Cheng, C.T.; et al. TGFβ induces "BRCAness" and sensitivity to PARP inhibition in breast cancer by regulating DNA-repair genes. Mol Cancer Res. 2014, 12, 1597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Zhou, X.M.; Li, Y.S.; et al. MicroRNA-181a promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma via the TGF-β/Smad pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhiping, C.; Shijun, T.; Linhui, W.; et al. MiR-181a promotes epithelial to mesenchymal transition of prostate cancer cells by targeting TGIF2. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017, 21, 4835–4843. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, S.; Pandey, M.; Shukla, G.C.; et al. Integrated analysis of miRNA landscape and cellular networking pathways in stage-specific prostate cancer. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0224071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, J.G.; Zheng, J.F.; Li, Q.; et al. MicroRNA-181a-5p suppresses cell proliferation by targeting Egr1 and inhibiting Egr1/TGF-β/Smad pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2019, 106, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ji, J.; Jin, Y.; et al. Tumor-mesothelium HOXA11-PDGF BB/TGF β1-miR-181a-5p-Egr1 feedforward amplifier circuity propels mesothelial fibrosis and peritoneal metastasis of gastric cancer. Oncogene. 2023 Nov 21.

- Erkeland, S.J.; Stavast, C.J.; Schilperoord-Vermeulen, J.; et al. The miR-200c/141-ZEB2-TGFβ axis is aberrant in human T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2022, 107, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Kang, D.; Kwon, M.Y.; et al. MicroRNAs as potential indicators of the development and progression of uterine leiomyoma. PLoS One. 2022, 17, e0268793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira TDSF, Brito, J. A.R.; Guimarães, A.L.S.; et al. MicroRNA profiling reveals dysregulated microRNAs and their target gene regulatory networks in cemento-ossifying fibroma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2018, 47, 78–85.

- Meng, F.; Glaser, S.S.; Francis, H.; et al. Functional analysis of microRNAs in human hepatocellular cancer stem cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2012, 16, 160–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Li, J.W.; Zhang, B.M.; et al. The lncRNA CRNDE promotes colorectal cancer cell proliferation and chemoresistance via miR-181a-5p-mediated regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Mol Cancer. 2017, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Fu, B.; et al. GATA6 activates Wnt signaling in pancreatic cancer by negatively regulating the Wnt antagonist Dickkopf-1. PLoS One. 2011, 6, e22129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borggrefe, T.; Oswald, F. The Notch signaling pathway: transcriptional regulation at Notch target genes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009, 66, 1631–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiu, M.X.; Liu, Y.M. The role of oncogenic Notch2 signaling in cancer: a novel therapeutic target. Am J Cancer Res. 2019, 9, 837–854. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.X.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Weng, G.H.; et al. Upregulation of miR-181a suppresses the formation of glioblastoma stem cells by targeting the Notch2 oncogene and correlates with good prognosis in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017, 486, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragoso, R.; Mao, T.; Wang, S.; et al. Modulating the strength and threshold of NOTCH oncogenic signals by mir-181a-1/b-1. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaviano, A.; Foo, A.S.C.; Lam, H.Y.; et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling transduction pathway and targeted therapies in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2023, 22, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Cui, L.; Mei, Z.; et al. miR-181a mediates metabolic shift in colon cancer cells via the PTEN/AKT pathway. FEBS Lett. 2014, 588, 1773–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.H.; Jiang, M.; Xiong, Z.A.; et al. Upregulation of miR-181a-5p and miR-125b-2-3p in the Maternal Circulation of Fetuses with Rh-Negative Hemolytic Disease of the Fetus and Newborn Could Be Related to Dysfunction of Placental Function. Dis Markers. 2022, 2022, 2594091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strotbek, M.; Schmid, S.; Sánchez-González, I.; et al. miR-181 elevates Akt signaling by co-targeting PHLPP2 and INPP4B phosphatases in luminal breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2017, 140, 2310–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, J.; Mei, H.; Luo, Q.; et al. TCL1A acts as a tumour suppressor by modulating gastric cancer autophagy via miR-181a-5p-TCL1A-Akt/mTOR-c-MYC loop. Carcinogenesis. 2023, 44, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Guan, Y.; Zheng, X.; et al. Hypoxia-induced miR-181a-5p up-regulation reduces epirubicin sensitivity in breast cancer cells through inhibiting EPDR1/TRPC1 to activate PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. BMC Cancer. 2024, 24, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, W.; Gao, Y.; Fan, X.; et al. MiR-181a contributes gefitinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancer cells by targeting GAS7. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018, 495, 2482–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z.X.; Zheng, Z.; Xue, W.; et al. MicroRNA181a Is Overexpressed in T-Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma and Related to Chemoresistance. Biomed Res Int. 2015, 2015, 197241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, G.; Wang, Y.; Houda, T.; et al. MicroRNA-181a suppresses norethisterone-promoted tumorigenesis of breast epithelial MCF10A cells through the PGRMC1/EGFR-PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Transl Oncol. 2021, 14, 101068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrabi, K.; Dufour, A.; Li, J.; et al. Inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase 14 (MMP-14)-mediated cancer cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2011, 286, 33167–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kuscu, C.; Banach, A.; et al. miR-181a-5p Inhibits Cancer Cell Migration and Angiogenesis via Downregulation of Matrix Metalloproteinase-14. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 2674–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Maldonado, C.; Zimmer, Y.; Medová, M. A Comparative Analysis of Individual RAS Mutations in Cancer Biology. Front Oncol. 2019, 9, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Schwind, S.; Santhanam, R.; et al. Targeting the RAS/MAPK pathway with miR-181a in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncotarget. 2016, 7, 59273–59286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Qiu, X.; Wang, D.; et al. MiR-181a-5p inhibits cell proliferation and migration by targeting Kras in non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2015, 47, 630–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, J.; Li, Y.; Zhu, X.; et al. miR-181a post-transcriptionally downregulates oncogenic RalA and contributes to growth inhibition and apoptosis in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). PLoS One. 2012, 7, e32834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.; Choi, H.Y.; Kwak, Y.; et al. TMBIM6-mediated miR-181a expression regulates breast cancer cell migration and invasion via the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. J Cancer. 2023, 14, 554–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.P.; Zheng, J.Y.; Du, J.J.; et al. What is the relationship among microRNA-181, epithelial cell-adhesion molecule (EpCAM) and beta-catenin in hepatic cancer stem cells. Hepatology. 2009, 50, 2047–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooqi, A.A.; Kapanova, G.; Kussainov, A.Z.; et al. Regulation of RASSF by non-coding RNAs in different cancers: RASSFs as masterminds of their own destiny as tumor suppressors and oncogenes. Noncoding RNA Res. 2022, 7, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New, L.; Han, J. The p38 MAP kinase pathway and its biological function. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 1998, 8, 220–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, R.; Lang, R. Dual Specificity Phosphatases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Biological Function. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, H.; Kohanbash, G.; Lotze, M.T. MicroRNAs in immune regulation--opportunities for cancer immunotherapy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010, 42, 1256–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.K.; Park, Y.K.; Ryu, J.C. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH)-mediated upregulation of hepatic microRNA-181 family promotes cancer cell migration by targeting MAPK phosphatase-5, regulating the activation of p38 MAPK. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013, 273, 130–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodosiou, A.; Smith, A.; Gillieron, C.; et al. MKP5, a new member of the MAP kinase phosphatase family, which selectively dephosphorylates stress-activated kinases. Oncogene. 1999, 18, 6981–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrallo-Gimeno, A.; Nieto, M.A. The Snail genes as inducers of cell movement and survival: implications in development and cancer. Development. 2005, 132, 3151–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.; Zhou, X.; Li, S.; et al. MicroRNA-181a suppresses salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma metastasis by targeting MAPK-Snai2 pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013, 1830, 5258–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Sui, X.; Weng, L.; et al. SNAIL1: Linking Tumor Metastasis to Immune Evasion. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 724200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Yan, F.; Ru, Y.; et al. MIIP inhibits EMT and cell invasion in prostate cancer through miR-181a/b-5p-KLF17 axis. Am J Cancer Res. 2020, 10, 630–647. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meng, Z.; Moroishi, T.; Guan, K.L. Mechanisms of Hippo pathway regulation. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ji, H.; et al. The interplay between noncoding RNA and YAP/TAZ signaling in cancers: molecular functions and mechanisms. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cen, A.; Yang, Y.; et al. miR-181a, delivered by hypoxic PTC-secreted exosomes, inhibits DACT2 by downregulating MLL3, leading to YAP-VEGF-mediated angiogenesis. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2021, 24, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorzalska, A.; Kim, J.F.; Roder, K.; et al. Long-Term Exposure to Imatinib Mesylate Downregulates Hippo Pathway and Activates YAP in a Model of Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia. Stem Cells Dev. 2017, 26, 656–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jiang, T.; Jia, Y.; et al. LncRNA MALAT1/miR-181a-5p affects the proliferation and adhesion of myeloma cells via regulation of Hippo-YAP signaling pathway. Cell Cycle. 2019, 18, 2509–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.A. The Jak/STAT pathway. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmann JLJC, Leon, L. G.; Stavast, C.J.; et al. miR-181a is a novel player in the STAT3-mediated survival network of TCRαβ+ CD8+ T large granular lymphocyte leukemia. Leukemia. 2022, 36, 983–993.

- Schäfer, A.; Evers, L.; Meier, L.; et al. The Metalloprotease-Disintegrin ADAM8 Alters the Tumor Suppressor miR-181a-5p Expression Profile in Glioblastoma Thereby Contributing to Its Aggressiveness. Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 826273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoo, L.T.; Chen, L.Y. Role of the cGAS-STING pathway in cancer development and oncotherapeutic approaches. EMBO Rep. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, Y.; Chen, Z.J. STING specifies IRF3 phosphorylation by TBK1 in the cytosolic DNA signaling pathway. Sci Signal. 2012, 5, ra20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; et al. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2017, 2, 17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wei, X.; Wang, Z.; et al. NF-κB activation enhances STING signaling by altering microtubule-mediated STING trafficking. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Zhu, W.; Shi, D.; et al. MicroRNA-181a sensitizes human malignant glioma U87MG cells to radiation by targeting Bcl-2. Oncol Rep. 2010, 23, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hai Ping, P.; Feng Bo, T.; Li, L.; et al. IL-1β/NF-kb signaling promotes colorectal cancer cell growth through miR-181a/PTEN axis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2016, 604, 20–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learn-Han N-SML, Sidik, S.; Rahman, S.; et al. miR-181a regulates multiple pathways in hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. African Journal of Biotechnology; 2014.

- Braicu, C.; Gulei, D.; Cojocneanu, R.; et al. miR-181a/b therapy in lung cancer: reality or myth? Mol Oncol. 2019, 13, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Paula Silva, E.; Marti, L.C.; Andreghetto, F.M.; et al. Extracellular vesicles cargo from head and neck cancer cell lines disrupt dendritic cells function and match plasma microRNAs. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 18534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado, T.; Amorim, A.; Enguita, F.J.; et al. MicroRNA-181a regulates IFN-γ expression in effector CD8. J Mol Med (Berl). 2020, 98, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardoll, D.M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012, 12, 252–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boussiotis, V.A. Molecular and Biochemical Aspects of the PD-1 Checkpoint Pathway. N Engl J Med. 2016, 375, 1767–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; et al. MicroRNA-181a promotes angiogenesis in colorectal cancer by targeting SRCIN1 to promote the SRC/VEGF signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Song, W.; Gao, Y.; et al. Increased PD-L1 Expression in Acquired Cisplatin-Resistant Lung Cancer Cells via Mir-181a. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2022, 257, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, D.; et al. MicroRNA-181a, a potential diagnosis marker, alleviates acute graft versus host disease by regulating IFN-γ production. Am J Hematol. 2015, 90, 998–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Diaz, A.; Shin, D.S.; Moreno, B.H.; et al. Interferon Receptor Signaling Pathways Regulating PD-L1 and PD-L2 Expression. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.X.; Gao, J.; Long, X.; et al. The circular RNA circHMGB2 drives immunosuppression and anti-PD-1 resistance in lung adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas via the miR-181a-5p/CARM1 axis. Mol Cancer. 2022, 21, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . !!! INVALID CITATION !!! [102].

- Shi, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Ye, N.; et al. MiR-181a inhibits non-small cell lung cancer cell proliferation by targeting CDK1. Cancer Biomark. 2017, 20, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; He, X.; Li, F.; et al. The miR-181 family promotes cell cycle by targeting CTDSPL, a phosphatase-like tumor suppressor in uveal melanoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Yang, J.; Yuan, R.; et al. Effects of miR-181a on the biological function of multiple myeloma. Oncol Rep. 2019, 42, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liao, W.; Peng, H.; et al. miR-181a promotes G1/S transition and cell proliferation in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia by targeting ATM. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016, 142, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Z.; Ma, X.; Li, H.; et al. Up-regulation of miR-181a in clear cell renal cell carcinoma is associated with lower KLF6 expression, enhanced cell proliferation, accelerated cell cycle transition, and diminished apoptosis. Urol Oncol. 2018, 36, 93.e23–93.e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Nie, Y.; Li, X.; et al. MicroRNA-181a functions as an oncomir in gastric cancer by targeting the tumour suppressor gene ATM. Pathol Oncol Res. 2014, 20, 381–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Hui, L.; Xu, W. miR-181a sensitizes a multidrug-resistant leukemia cell line K562/A02 to daunorubicin by targeting BCL-2. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2012, 44, 269–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, S.; et al. The function role of miR-181a in chemosensitivity to adriamycin by targeting Bcl-2 in low-invasive breast cancer cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2013, 32, 1225–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Majzoub, R.; Fayyad-Kazan, M.; Nasr El Dine, A.; et al. A thiosemicarbazone derivative induces triple negative breast cancer cell apoptosis: possible role of miRNA-125a-5p and miRNA-181a-5p. Genes Genomics. 2019, 41, 1431–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wan, H.; Zhang, X. LncRNA LHFPL3-AS1 contributes to tumorigenesis of melanoma stem cells via the miR-181a-5p/BCL2 pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Xu, P.; Zhou, X.; et al. MiR-181a enhances drug sensitivity of mixed lineage leukemia-rearranged acute myeloid leukemia by increasing poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase1 acetylation. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021, 62, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bräuer-Hartmann, D.; Hartmann, J.U.; Wurm, A.A.; et al. PML/RARα-Regulated miR-181a/b Cluster Targets the Tumor Suppressor RASSF1A in Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 3411–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Qi, J.; Sun, X.; et al. MicroRNA-181a promotes cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis in gastric cancer by targeting RASSF1A. Oncol Rep. 2018, 40, 1959–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Wang, L.; Yang, C.; et al. Micro-RNA-181a suppresses progestin-promoted breast cancer cell growth. Maturitas. 2018, 114, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ota, D.; Mimori, K.; Yokobori, T.; et al. Identification of recurrence-related microRNAs in the bone marrow of breast cancer patients. Int J Oncol. 2011, 38, 955–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cmarik, J.L.; Min, H.; Hegamyer, G.; et al. Differentially expressed protein Pdcd4 inhibits tumor promoter-induced neoplastic transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999, 96, 14037–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Huang, H.; Li, Y.; et al. Up-regulation of a HOXA-PBX3 homeobox-gene signature following down-regulation of miR-181 is associated with adverse prognosis in patients with cytogenetically abnormal AML. Blood. 2012, 119, 2314–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhai, X.; Ge, T.; et al. miR-181a-5p Promotes Proliferation and Invasion and Inhibits Apoptosis of Cervical Cancer Cells via Regulating Inositol Polyphosphate-5-Phosphatase A (INPP5A). Oncol Res. 2018, 26, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, R.; Lu, Z.; et al. Exosomes from M1-polarized macrophages promote apoptosis in lung adenocarcinoma via the miR-181a-5p/ETS1/STK16 axis. Cancer Sci. 2022, 113, 986–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenone, S.; Manetti, F.; Botta, M. SRC inhibitors and angiogenesis. Curr Pharm Des. 2007, 13, 2118–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summy, J.M.; Gallick, G.E. Src family kinases in tumor progression and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003, 22, 337–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Wei, L.; Chen, Q.; et al. MicroRNA regulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression in chondrosarcoma cells. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015, 473, 907–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillot, G.; Lacroix-Triki, M.; Pierredon, S.; et al. Widespread estrogen-dependent repression of micrornas involved in breast tumor cell growth. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 8332–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilam, A.; Shai, A.; Ashkenazi, I.; et al. MicroRNA regulation of progesterone receptor in breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 25963–25976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, F.; et al. Liver-specific deletion of miR-181ab1 reduces liver tumour progression via upregulation of CBX7. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022, 79, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterson, M.R.; Jackson, K.L.; Dona, M.S.I.; et al. Deficiency of MicroRNA-181a Results in Transcriptome-Wide Cell-Specific Changes in the Kidney and Increases Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2021, 78, 1322–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henao-Mejia, J.; Williams, A.; Goff, L.A.; et al. The microRNA miR-181 is a critical cellular metabolic rheostat essential for NKT cell ontogenesis and lymphocyte development and homeostasis. Immunity. 2013, 38, 984–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Z.; Li, G.; Kim, C.; et al. Regulation of miR-181a expression in T cell aging. Nat Commun. 2018, 9, 3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaffert, S.A.; Loh, C.; Wang, S.; et al. mir-181a-1/b-1 Modulates Tolerance through Opposing Activities in Selection and Peripheral T Cell Function. J Immunol. 2015, 195, 1470–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łyszkiewicz, M.; Winter, S.J.; Witzlau, K.; et al. miR-181a/b-1 controls thymic selection of Treg cells and tunes their suppressive capacity. PLoS Biol. 2019, 17, e2006716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziętara, N.; Łyszkiewicz, M.; Witzlau, K.; et al. Critical role for miR-181a/b-1 in agonist selection of invariant natural killer T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013, 110, 7407–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, K.; Erice, O.; Kostyrko, K.; et al. The Mir181ab1 cluster promotes KRAS-driven oncogenesis and progression in lung and pancreas. J Clin Invest. 2020, 130, 1879–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Schwind, S.; Yu, B.; et al. Targeted delivery of microRNA-29b by transferrin-conjugated anionic lipopolyplex nanoparticles: a novel therapeutic strategy in acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 2355–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaei, S.N.; Derbali, R.M.; Yang, C.; et al. Co-delivery of miR-181a and melphalan by lipid nanoparticles for treatment of seeded retinoblastoma. J Control Release. 2019, 298, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passos Gibson, V.; Tahiri, H.; Yang, C.; et al. Hyaluronan decorated layer-by-layer assembled lipid nanoparticles for miR-181a delivery in glioblastoma treatment. Biomaterials. 2023, 302, 122341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, J.; Yan, Q.; Li, Z.; et al. Multifunctional miR181a nanoparticles promote highly efficient radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Materials Today Advances 2022, 16, 100317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Chen, Y.; Yu, H.; et al. Anti-miRNA Oligonucleotide Therapy for Chondrosarcoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2019, 18, 2021–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norkaew, C.; Subkorn, P.; Chatupheeraphat, C.; et al. Pinostrobin, a fingerroot compound, regulates miR-181b-5p and induces acute leukemic cell apoptosis. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 8084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sun, T.; Yang, X.; et al. Astragaloside IV Overcomes Anlotinib Resistance in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer through miR-181a-3p/UPR-ERAD Axis. Curr Comput Aided Drug Des. 2024 Jan 17.

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Rayess, Y.E.; Rizk, A.A.; et al. Turmeric and Its Major Compound Curcumin on Health: Bioactive Effects and Safety Profiles for Food, Pharmaceutical, Biotechnological and Medicinal Applications. Front Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 01021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, F.; Mhatre, A.; Koroth, J.; et al. Curcumin modulates cell type-specific miRNA networks to induce cytotoxicity in ovarian cancer cells. Life Sci. 2023, 334, 122224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewangan, J.; Tandon, D.; Srivastava, S.; et al. Novel combination of salinomycin and resveratrol synergistically enhances the anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects on human breast cancer cells. Apoptosis. 2017, 22, 1246–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ma, J.; Ma, Q.; et al. Resveratrol inhibits the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of pancreatic cancer cells via suppression of the PI-3K/Akt/NF-κB pathway. Curr Med Chem. 2013, 20, 4185–4194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, Y. ; Ong'achwa MJ, et al. Resveratrol Inhibits the TGF-. Biomed Res Int. 2018, 2018, 8730593. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, H.Y.; Liu, M.W.; Yang, G. Resveratrol suppresses lipopolysaccharide-mediated activation of osteoclast precursor RAW 264. 7 cells by increasing miR-181a-5p expression. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2023, 37, 3946320231154995. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Latson, G.W. Perftoran: History, Clinical Trials, and Pathway Forward. In: Liu, H.; Kaye, A.D.; Jahr, J.S.; editors. Blood Substitutes and Oxygen Biotherapeutics. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 361-367.

- Gamal-Eldeen, A.M.; Alrehaili, A.A.; Alharthi, A.; et al. Effect of Combined Perftoran and Indocyanine Green-Photodynamic Therapy on HypoxamiRs and OncomiRs in Lung Cancer Cells. Front Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 844104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, G.; Liang, L.; Yang, J.M.; et al. MiR-181a confers resistance of cervical cancer to radiation therapy through targeting the pro-apoptotic PRKCD gene. Oncogene. 2013, 32, 3019–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Ke, G.; Han, D.; et al. MicroRNA-181a enhances the chemoresistance of human cervical squamous cell carcinoma to cisplatin by targeting PRKCD. Exp Cell Res. 2014, 320, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyhan, A.A. Trials and Tribulations of MicroRNA Therapeutics. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).