1. Introduction

Pleural drainage consists of inserting a flexible tube, called

chest tube or

thoracostomy tube, through the chest wall, into the pleural space. It is an essential procedure in the diagnostic and therapeutic management of pleural diseases including pleural effusion, empyema, hemothorax, and pneumothorax. Instruments and techniques for pleural drainage have evolved significantly over time, reflecting medical technology advances and deeper understanding of pleural pathophysiology. ([

1])

2. Historical Background

The concept of pleural drainage dates back to ancient times. Hippocrates (460-370 BC) is often credited with describing the first form of pleural drainage using hollow reeds to drain empyemas. ([

2]) However, it was only in the 19th century that chest tube thoracostomy, as it is recognized today, began to take its current shape. ([

3])

2.1. Nineteenth Century Developments

Before the development of antibiotics, closed-space infections were an almost exclusive concern of surgeons, who generally approached them with early, aggressive, open drainage. Little was known about the pathophysiology of the pleural space and open pneumothorax was considered the inevitable consequence of surgical evacuation except for cases in which the empyema caused adhesions between the visceral and parietal pleura, thus preventing lung collapse.

In 1871, British physician William Smoult Playfair devised subaqueous drainage to completely drain thoracic empyemas in children while preventing air from entering the pleural cavity. ([

4])

Similarly, in 1875, German internist Gotthard Bülau, introduced the closed drainage system using a siphon principle, which significantly reduced the risk of infection compared to open drainage. ([

5]) His technique was published in 1891, but was rarely used for several years.

2.2. Twentieth Century Advancements

In 1917–1918, during World War I, the influenza pandemic resulted in many cases of subsequent group-A streptococcal pneumonia and hemorrhagic pleural effusions in military camps, with very high mortality rates despite the use of open drainage. It was then that Evarts Ambrose Graham, a captain in the Army Medical Corps, was appointed to the U.S. Army Empyema Commission and began treating empyema successfully with closed drainage systems. ([

6])

The World War II period saw further advancements in the emergency use of chest tubes for pleural diseases in soldiers. Indeed, the need for effective management of traumatic hemothorax and pneumothorax spurred innovations in chest drainage systems.

The introduction of plastic materials in the mid-20th century revolutionized chest tube design, making them more flexible and less prone to kinking. Closed thoracostomy and underwater seal drainage became the standard of care for blunt thoracic trauma and treatment in the Vietnam War. ([

7])

In 1968, Heimlich designed a unidirectional valve which, when connected to the drainage tube, ensured the drainage of gas or fluid from the pleural space without backflow. ([

8]) This system was sterile and disposable and had the advantage of allowing patient ambulation compared to bulky underwater drainage bottles.

3. Modern Equipment

Modern chest tube thoracostomy involves several key components (tube, drainage system, and suction system) and techniques designed to improve patient outcomes, reduce clogging, and minimize complications.

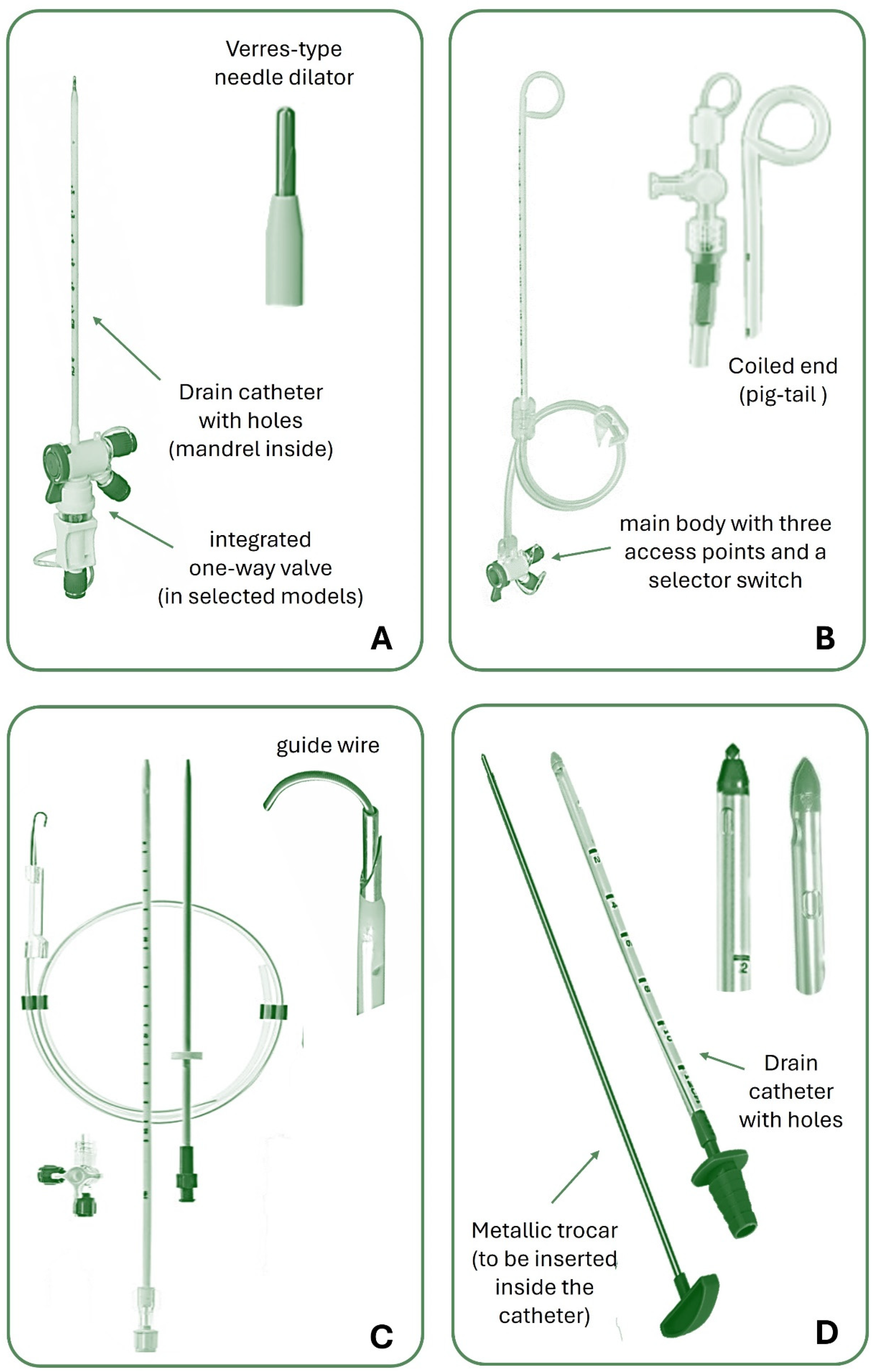

3.1. Chest Tubes

Chest tubes are typically made from polyvinyl chloride (PVC) or silicone, and vary in size and design to suit different clinical scenarios. With the advancement of technology, different chest tube types have been produced. They can be straight, angled, spiral or coiled at the end (called “pig-tail”). They can drain through a central channel, with distal fenestrations at the tip and sides or have several channels (i.e., a Blake drain, Ethicon, USA) to facilitate pleural fluid drainage. A radiopaque stripe aids tube recognition on chest X-ray and there is typically a marker that is a set distance to the most proximal drain hole (sentinel hole). Some tubes can have a double lumen for aspiration or infusion simultaneously. ([

9]) It should be noted that the shape of the tube and their ability to “lock” are completely separate – and indeed, locking chest tubes should be avoided in pleural drainage due to the risk of intercostal artery laceration on removal.

The size of a chest tube is typically measured according to the French system, where it is expressed in “Ch” (Charrière, from the name of the creator) or more simply in “Fr” (French, from the country where Charrière lived). ([

10]) The value of Ch or Fr corresponds to the external circumference of the catheter, so the diameter in millimeters can be approximately calculated by dividing the “Fr” by 3. For example, a 12 Fr/Ch tube has an external diameter of about 4 mm.

Commonly “small-bore” chest tubes (SBCTs) range from 8 to 14 Fr and their insertion is less invasive. They are the most used tubes to drain air (pneumothorax) as well as all different types of pleural effusion (including empyema and hemothorax), due to their high maneuverability, limited complications, and better tolerability by patients in comparison with large-bore chest tubes (LBCTs). ([

11])

Among LBCTs (> 14 Fr), those with a diameter between 16 and 24 Fr (sometimes referred to as medium-bore chest tubes) are often used for draining air or liquids including pus and blood, whereas 28 to 36 Fr tubes are usually reserved for drainage of thick fluids (hemothorax, empyema), especially in cases of severe trauma, need for rapid evacuation, or post-surgical drainage where there may be a large air leak. Larger tubes unavoidably lead to greater pain and complications.

Figure 1 shows some commonly used types of chest tubes.

Note that large-bore tubes should not be inserted with a trocar due to the risk of tissue damage and complications. Blunt dissection is preferred, as it minimizes trauma and allows for safer placement compared to the guide wire technique, which is better suited for smaller catheters

3.2. Chest Drainage Units

An adequate chest drainage system aims to remove pleural fluid and/or air, prevent their reflux into the pleural space, and restore negative pleural pressure (less than atmospheric pressure) to allow lung re-expansion. ([

12])

Overall, a chest drainage unit (CDU) is a sterile, disposable device consisting of a flexible tube connected to one or more chambers that collect the fluid, to be positioned below the level of the chest tube insertion to allow the fluid to escape by gravity.

CDUs have evolved significantly since their introduction but essentially include one-way valves (Heimlich valve) or water-seal drainage systems to prevent the backflow of air or fluid into the pleural space.

An underwater-seal chest drainage system consists of a two or three-chamber plastic unit with vertical columns displaying milliliter measurements (

Figure 2). Their development stems from the original single-bottle system designed by Bülau, where a rigid straw, connected to the chest tube, entered the bottle and found itself with the tip immersed in saline solution. An opening with a one-way valve allowed air to escape and prevented pressure build-up in the system. However, the one-bottle system worked well if only air exits the pleural cavity, whereas if a pleural effusion is drained, the fluid level in the bottle will increase and reduce the efficiency of removing additional air or fluid from the patient. [

12]

In two-bottle systems, the first bottle is responsible for collecting fluid, whereas the second bottle contains the water seal. They are preferred over the one-bottle system when large quantities of pleural liquid are drained, as fluid drainage does not affect the pressure gradient for further evacuation of fluid or air from the pleural space. Three-bottle systems have a third bottle or chamber, useful if suction is required.

All these chambers are currently integrated into modern, multifunctional, easy-to-manage boxes.

Recently, smart digital drainage systems have been introduced, capable of recording the flows of evacuated air or liquid, monitoring the pleural pressure, and graphically reporting all the data. ([

13,

14])

3.3. Suction Systems for Pleural Drainage

The application of suction to pleural drainage systems can be useful in particular conditions not resolving with gravity drainage alone, to facilitate lung re-expansion and fluid or air removal. Data regarding the efficacy of suction following open or thoracoscopic lung surgery is controversial. ([

15,

16,

17,

18]) Similarly, data to support a benefit in patients with pneumothorax are weak. ([

19]) In theory, the lung expansion obtained through external suction would allow apposition of the visceral and parietal pleura to exert a compression effect on the area of a visceral pleural defect and consequently stop air leaks. However, excessive negative intrapleural pressure produced by suction may induce an increased airflow through the defect, especially in patients with non-expandable lung. ([

20,

21]) Traditional water-seal CDUs have been associated with a significantly shorter duration of postoperative air leak and chest drainage compared with continuous suction and digital drainages. ([

22])

Application of suction should be avoided immediately after chest tube insertion as it may increase the risk of reexpansion pulmonary edema (RPO), particularly in young patients with complete pneumothorax or if the lung has been deflated for a prolonged time. ([

23,

24])

Water-seals regulate the amount of suction by the height of a column of water in the suction control chamber. The suction control chamber is filled with water to the desired level. An external vacuum source generates a negative pressure pulling air through the water column. The water column height resists this pull, thereby regulating the suction pressure to the set level. Wall suction provides consistent and adjustable suction pressure that is set by the depth of the column of liquid in the collection system and not by the suction read on the wall pressure gauge. With a 20 cmH₂O water column in the suction control chamber, the maximum suction pressure exerted on the pleural space will be -20 cmH₂O, regardless of the external vacuum source’s strength. This method ensures a consistent and precise level of suction.

This system requires regular checking and maintenance to ensure the water level is correct, as evaporation could alter the water level over time. ([

25]) Newer systems use a ‘dry’ technique, where the amount of suction is applied by a setting on the drainage box. As with the ‘wet’ systems, pressure to the patient can never be more negative than the pressure set on the chest drain.

Wall suction can be used in inpatients as it utilizes the hospital’s central vacuum system. The suction pressure is regulated through a control valve and applied to the pleural drainage system via tubing connected to the drainage chamber. In addition to being limited to hospital settings with central vacuum infrastructure, this system restricts patient’s mobility and involves a risk of applying excessive pressure if not properly regulated.

Portable Suction Devices can be used in both hospital and outpatient settings, particularly for ambulatory patients or those requiring home care. They use battery or electrical power to generate negative pressure, and are connected to the drainage system via tubing, providing adjustable suction settings. These devices enhance patient mobility and independence, although they can be less powerful than wall suction and require regular maintenance and battery charging.

Mechanical suction regulators are used in conjunction with water-seal or dry suction pleural drainage systems in hospitals to control the amount of negative pressure applied to the drainage system. They are connected between the wall suction source and the drainage system, ensuring that the pressure remains within a safe and therapeutic range, typically between -10 and -20 cmH₂O.They require careful calibration and monitoring to ensure effective function.

4. Clinical Applications

Chest tubes are employed in various pleural diseases, each with specific indications and management protocols.

Table 1 provides a summary of the indications for chest tube placement in both pleural effusion and pneumothorax, including relevant descriptions.

4.1. Pleural Effusion

Transudative effusions are typically managed medically, with chest tube drainage reserved for symptomatic relief or diagnostic purposes. ([

26]) These effusions are usually the result of systemic conditions such as heart failure, liver cirrhosis, or nephrotic syndrome, where the underlying issue causes fluid to accumulate in the pleural space. ([

27]) Treatment focuses on addressing the root cause, and in cases where significant symptoms, such as breathlessness, occur, a chest tube may be inserted to drain the fluid and provide relief. ([

28])

Refractory symptomatic transudative pleural effusions despite maximal therapy constitute an indication for pleural drainage alternative to repeated thoracentesis. ([

29])

Some observational evidence has supported the use of indwelling pleural catheters (IPCs) in such patients, whose main role lies in the symptomatic management of malignant pleural effusion.

However, the data regarding trasudates are not univocal and a recent randomized trial did not highlight a significant difference in breathlessness palliation over 12 weeks between IPCs and standard care with therapeutic thoracentesis. Thoracentesis was associated with fewer complications while IPCs reduced the number of invasive pleural procedures. ([

30])

In patients with refractory hepatic hydrothorax waiting for liver transplantation or for whom it is contraindicated, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) placement represents the most useful treatment, although serial thoracenteses and insertion of an indwelling pleural catheter (IPC) represent possible second-line options. ([

31,

32])

Exudative effusions, on the other hand, are often associated with infections, malignancy, or inflammatory diseases, resulting from local factors affecting the pleura, such as increased capillary permeability, infection, or neoplastic pleura infiltration. Therapeutic drainage via chest tube is commonly required not only to relieve symptoms but also to obtain a sample for diagnostic analysis, which can guide further treatment. ([

33])

In some instances, particularly when pleural effusion is recurrent, pleurodesis might be an option to reduce the risk of relapses. ([

34]) Pleurodesis can be performed via the introduction of a sclerosing agent through the chest tube into the pleural space (“slurry technique”), causing adherences between the pleural layers, obliterating the space, and thus preventing the reaccumulation of fluid. This procedure is particularly beneficial in malignant pleural effusions or chronic conditions where repeated fluid buildup significantly impairs the patient’s quality of life. Pleurodesis can be achieved using various agents such as talc, autologous blood, tetracycline, doxycycline, or bleomycin, and can also be performed under direct visualization during medical thoracoscopy or video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) to ensure even distribution of the sclerosant and maximize efficacy (“poudrage technique”). Two large randomized trials have not shown a difference between slurry and poudrage. ([

35,

36])

The TIME1 randomized clinical trial demonstrated that larger chest tubes (i.e., 24F) are more efficient than smaller (12F) to induce talc slurry pleurodesis in patients with malignant pleural effusion ([

37]). The authors would certainly recommend a tube size greater than 12F for pleurodesis attempts with talc due to issues with blockage with smaller tubes.

4.2. Complicated Pleural Effusion or Empyema

A pleural effusion is defined as “complicated” when the pleural effusion becomes loculated, pH and glucose fall and LDH increases. In this stage, antibiotic therapy alone is generally not sufficient for healing. Empyema is a type of complicated pleural effusion in which the pleural cavity contains frank pus or if the Gram stain / culture are positive. Complicated pleural effusion (CPE) and empyema require prompt drainage to increase the chance of resolving local infection, reduce the risk of further spread of microbes and sepsis, and prevent long-term sequelae such as fibrothorax. ([

38]) The use of chest tubes in these settings is a well-established cornerstone of therapeutic intervention.

CPE can progress through three stages: exudative, fibrinopurulent, and organizing. During the early exudative phase of a CPE, the pleural fluid is free-flowing and easily drained by thoracentesis. As the condition advances to the fibrinopurulent stage, the fluid becomes more viscous due to fibrin deposition, often necessitating chest tube placement or adjunctive therapies such as rTPA/DNAse to facilitate drainage. In the organizing phase, where fibrous septations form, chest tube drainage alone may be insufficient, and additional interventions like medical thoracoscopy, VATS, or open decortication might be required. ([

39,

40])

The effectiveness of chest tube drainage is influenced by several factors, including the size and location of the effusion, the viscosity of the pleural fluid, and the presence of loculations. Consequently, careful patient selection and technique are paramount. ([

41]) LBCTs of 20-28 French were generally preferred for their superior drainage capabilities in thick, purulent effusions. However, small-bore catheters (10-14 French) have gained popularity due to their less invasive nature and comparable efficacy in certain scenarios, particularly when combined with rTPA/DNAse therapy. ([

42,

43])

In addition to mechanical drainage, the role of intrapleural fibrinolytics and enzymatic debridement has been increasingly recognized, especially when simple drainage fails and the patient is not suitable for surgery. Agents such as tissue plasminogen activator (rTPA) combined with DNase can enhance drainage efficacy by breaking down fibrinous septations and reducing fluid viscosity, thereby improving outcomes in patients with loculated effusions. [

38]

4.3. Hemothorax

Pleural drainage, specifically the use of chest tubes, plays a critical role in the management of hemothorax, which is the accumulation of blood in the pleural cavity. The primary objectives of pleural drainage in hemothorax are to evacuate the blood, restore normal respiratory function, prevent clot formation, monitor for ongoing bleeding, and prevent long-term complications such as fibrothorax. ([

44])

Hemothorax often results from traumatic injury, surgical complications, or spontaneous causes such as rupture of blood vessels in the pleura. Conservative treatment of occult hemothorax fails in over one patient out of five and the presence of hemothorax greater than 300 mL and the need for mechanical ventilation predict failure of conservative treatment and the need for a thoracostomy tube. ([

45])

Immediate pleural drainage is essential to mitigate the risk of respiratory distress and to facilitate lung re-expansion. The placement of 28-32 French LBCTs has been historically recommended for initial management to ensure effective evacuation of blood and clots. Recent evidence suggests that 14Fr percutaneous pig-tail catheters can be equally effective as 28-32Fr tubes in patients with traumatic hemothorax or hemopneumothorax, resulting in reduced patient discomfort during and after insertion. ([

46])

The initial volume of blood drained can provide crucial diagnostic information. Drainage of more than 1,500 mL of blood upon chest tube insertion, or continued bleeding of more than 200 mL per hour over 2-4 hours, often indicates the need for surgical intervention, such as thoracotomy, to control the source of bleeding. Moreover, in cases of retained hemothorax, where clotted blood remains in the pleural space despite initial drainage, early VATS has been shown to be effective. VATS allows for direct visualization and removal of clots, reducing the risk of infection and fibrothorax ([

47])

The management of hemothorax with pleural drainage is associated with a significant reduction in morbidity and mortality when promptly and appropriately administered. Recent studies highlight the importance of early intervention and the use of adjunctive techniques such as VATS or thrombolytic therapy (tPA and DNase) in cases where conventional drainage fails to evacuate the hemothorax completely ([

48,

49,

50]). These advancements underline the evolving landscape of hemothorax management and the critical role of pleural drainage in improving patient outcomes.

4.4. Pneumothorax

Pneumothorax, characterized by the presence of air in the pleural cavity, can be classified as spontaneous or traumatic. Spontaneous pneumothorax can in turn be primary (occurring without any apparent underlying lung disease) or secondary (associated with pre-existing lung pathology). It has been suggested though, that many patients with primary spontaneous pneumothorax actually have emphysema like changes / pleural porosity, that has not been identified by chest imaging and the distinction between primary and secondary pneumothorax may not be as important. ([

51])

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax (PSP) typically affects young, healthy individuals. It often results from the rupture of subpleural blebs or bullae, which are more common in tall, thin, young men. The most common causes of secondary spontaneous pneumothorax (SSP) are chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cystic fibrosis, lung malignancy, or infections. These conditions compromise alveolar integrity, leading to air leakage into the pleural space. Traumatic pneumothorax results from blunt or penetrating chest injury (e.g., rib fractures, stab wounds). Iatrogenic pneumothorax is a subtype caused by medical procedures such as lung biopsies or central venous catheter placements.

Pneumothorax often requires chest tube placement for the evacuation of air and re-expansion of the lung (

Table 1), while needle aspiration may be sufficient for small pneumothoraces. Chest tube insertion is highly effective in managing PSP. Success rates for lung re-expansion are high, typically around 80-90%. However, recurrence rates can be significant, with 23-50% of patients experiencing another episode.

In the last decade, the choice of whether to drain a PSP pneumothorax was mainly chosen on the distance > 2 cm between the lung and the chest wall at the hilum (or 3cm at the apicies) on a posteroanterior chest x-ray. ([

52]) However, many experts are adopting a more conservative approach in selected cases. [

24]

A recent randomized controlled study showed that 94% of patients with large but minimally symptomatic PSP treated conservatively achieved complete re-expansion within 8 weeks. The enrolled subjects had an SPS size ≥ 32%, corresponding to the sum of interpleural distances > 6 cm on erect posteroanterior chest X-ray, according to the Collins method. ([

53]) The success achieved with drainage was 98% but the difference was not statistically significant. Furthermore, patients treated conservatively experienced significantly lower rates of 12-month recurrence (8.8% versus 16.8% of patients undergoing thoracic drainage). ([

54])

Accordingly, the most recent British Thoracic Society (BTS) guideline for pleural disease emphasized that asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients with PSP pneumothorax may be managed conservatively without immediate invasive procedures. (Roberts_BTS_2023,[

55])

In SSP, chest tube insertion is crucial due to potentially large and prolonged air leaks, and the increased risk of morbidity and mortality. Success rates are lower compared to PSP due to the underlying lung pathology. Persistent air leaks are more common, and additional interventions such as surgery or chemical pleurodesis may be required. In the presence of high surgical risk, maintaining the tube for a long time may be the only way to allow continuous evacuation of air from the pleural cavity and prevent tension pneumothorax. ([

56])

Chest tube insertion is critical in managing traumatic pneumothorax, particularly when bilateral, when there is associated hemothorax or large air leaks. The management of pneumothorax has seen significant advances with the introduction of portable long-term air leak devices. These devices allow for safe and effective outpatient treatment, reducing hospital stays and healthcare costs while providing continuous monitoring of pleural air leaks. Moreover, they offer patients greater mobility and quality of life during the recovery process, making them an essential option in the management of both spontaneous and post-surgical pneumothorax. ([

57])

Tension pneumothorax is an emergency condition where immediate chest tube insertion can be lifesaving by relieving pressure on the mediastinum and restoring cardiovascular stability.

5. Measures for Appropriate Chest Tube Placement

5.1. Insertion Site

Chest X-ray and computed tomography (CT) scan provide essential information for the diagnostic workup of pleural diseases that may require a chest drain. Thoracic ultrasound (TUS) has become the method of choice to define the indication for the procedure and choose the type of chest tube and the insertion site. Imaging examinations should always precede the placing of a chest tube unless the situation’s urgency and the setting do not allow it (for example, in the case of tension pneumothorax, especially in an out-of-hospital setting).

In adults, the fourth or fifth intercostal space (approximately at the level of the nipple) along the midaxillary line is commonly used as the chest tube insertion site to drain a pleural effusion. This corresponds to the “safe triangle” area, posterior to the pectoralis major muscle, and anterior to the latissimus dorsi muscle. ([

58]) An incision 1 cm anterior to the midaxillary line appears to reduce the risk of damaging the peripheral nerves of the lateral thoracic wall. ([

59]) Loculated pleural effusion may require different insertion positions, identified by ultrasound. Apical pneumothorax and tension pneumothorax are often drained through the second or third intercostal space at the midclavicular line. However, this site may be uncomfortable for the patient and leave an unsightly scar, so it should not be the first choice. ([

60])

Occasionally two simultaneous or consecutive chest tubes may be necessary to effectively drain non-communicating infected fluid collections after attempted intrapleural fibrinolytics/DNAse. It is common practice to insert the chest tube using the so-called freehand technique, in which the doctor marks the entry point under ultrasound guidance and then performs the procedure immediately afterward without moving the patient.

5.2. Chest Tube Insertion Techniques

In most circumstances, nowadays chest drainages are inserted at the patient’s bedside. Except for penetrating chest injuries, prophylactic administration of antibiotics ahead of chest tube placement is not required. ([

61]) SBCTs can be inserted using the Seldinger technique, also known as the guidewire technique, or through an atraumatic stylet that introduces the drain in the pleural space without needing a guidewire. Modern kits for inserting SBCT have a Verres-type needle and an inner stylet with a dull tip to protect the lungs from injury. During insertion, the stylet’s blunt tip is pushed into the needle, exposing the cutting profile. After the needle reaches the pleural cavity, a spring pushes the atraumatic tip out to its previous position. These are the most widespread methods due to the ease of insertion and increased patient comfort. ([

62])

The trocar technique consists of introducing the tube thoracostomy together with a trocar into the pleural space by strength. Its use is decreasing due to the greater risk of damaging surrounding tissues, including blood vessels and lung parenchyma, leading to complications such as hemorrhage or lung injury. Thus, the authors would not recommend use of the trocar. Blunt dissection, on the other hand, allows for a controlled and gradual separation of tissue layers, minimizing trauma. Unlike the guide wire technique, which is better suited for smaller bore catheters, blunt dissection ensures safer placement of large-bore tubes in cases of significant pleural effusions or pneumothorax requiring rapid drainage. ([

63])

To place a chest tube, the patient usually lies in the lateral or supine recumbent position. Once the intercostal space has been chosen, the skin must be disinfected and local anesthesia (usually Lidocaine) administered to the insertion site, up to the deeper tissues. Placement of the chest tube over an area of skin affected by infection or tumor infiltration should be avoided. The needle goes over the upper edge of the rib to reduce the risk of damage to the neurovascular bundle. Aspiration into the syrinx of air bubbles (in pneumothorax) or fluid (in pleural effusions) confirms that the needle reached the pleural space. A small incision in the skin facilitates the introduction of the catheter. ([

64])

To insert LBCTs, a blunt dissection is needed to reach the pleural space.

The tube should be directed posteriorly and downwards to drain a pleural effusion or toward the front, and upward to remove air in pneumothorax. Once the tube is placed, it is sutured in place and connected to a drainage system with underwater seal or suction.

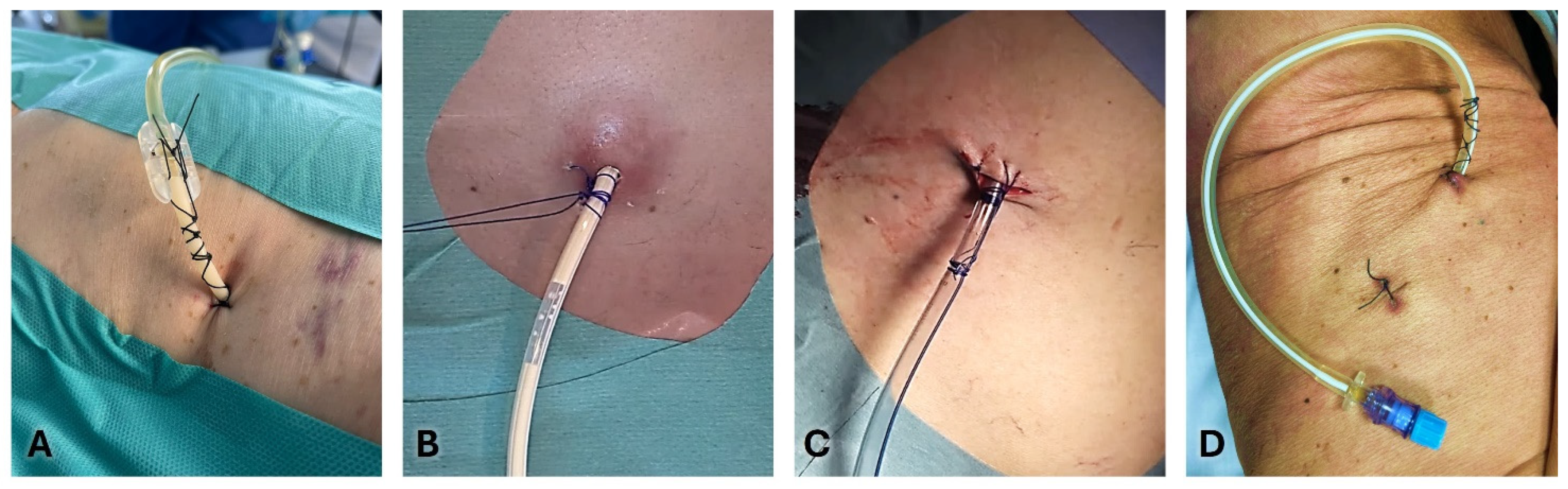

5.3. Securing the Chest Tube

Anchoring a chest tube is essential to ensure its proper function and to prevent infections and dislodgement. ([

65]) There is evidence that suturing chest tubes can lower the rates of their unintentional dislodgment outside the pleural cavity before a clinical decision to remove the drain (6.6% versus 14.8% of non-sutured drains). ([

66])

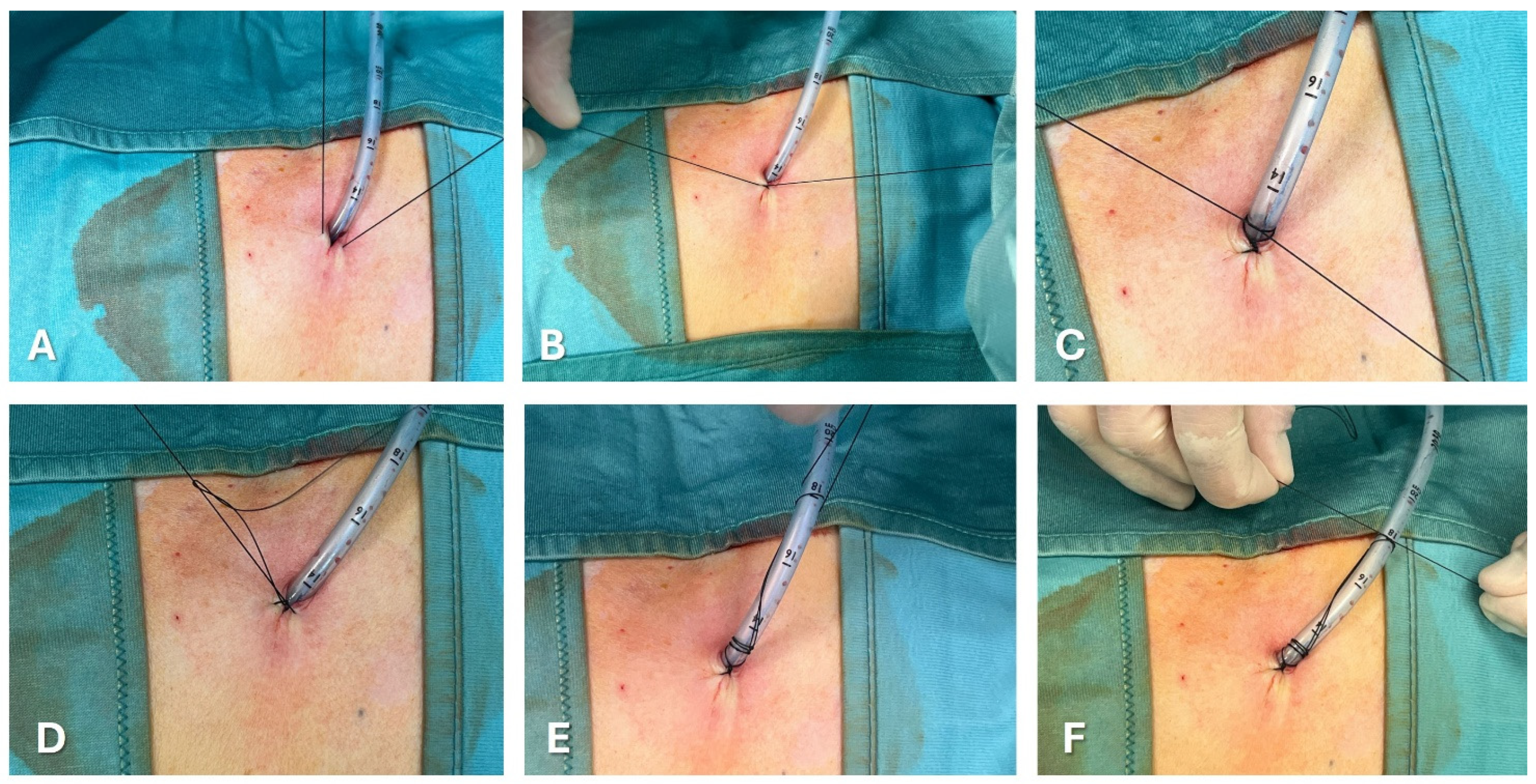

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show the most common methods for anchoring a pleural drain and the progressive steps to secure a large-bore chest tube using the purse-string technique.A recent multicenter trial compared a ballooned 12 Fr intercostal drain to a similar-sized tube secured with a single suture. The balloon integrated into the drain works like a bladder catheter which can be inflated with sterile water when it lies inside the pleural space to stop it from slipping out. ([

67]) The analyses showed a trend favorable to ballooned drain, although not statistically significant, of displacement rate (3.9% versus 10.1%). The control group’s displacement rate was less than expected in real-life practice, probably due partially to the high degree of utilization of ultrasound during the study.

The simple Donati stitch (horizontal mattress suture) uses a large-bore needle to place a suture through the skin, around the chest tube insertion site, and out through the skin again, forming a figure-of-eight or mattress suture.

In the purse-string suture technique, a suture is placed circularly around the chest tube insertion site. When tied, it cinches the tissue around the tube.

The Roman sandal technique is a common strategy to reduce dislodgement risk.

The suture thread is placed around the tube, crisscrossed, and tied in a manner resembling a Roman sandal’s lacing.

Tube securement devices are commercially available, which adhere to the skin and grip the tube, providing an alternative to sutures. They offer a quick and often more comfortable way to secure the chest tube, with less risk of skin irritation and infection.

Finally, sterile adhesive dressings and tapes are used to anchor the tube to the chest wall. They reinforce the stability provided by sutures or securement devices, reducing movement and the risk of dislodgement.

Usually, number 1 or 0 silk sutures are used for large bore tubes, and 00 for small bore tubes.

When the incision has left space next to the drain, a second suture may be necessary to prevent the passage of liquid or air. The retaining stitches are commonly maintained 10-15 days after removing chest tube.

6. Complications and Management

Despite advancements, chest tube placement is not without risks. Complications include tube malposition, infection, bleeding, organ injury, and re-expansion pulmonary edema. Preventative measures and prompt management of complications are critical.

6.1. Preventative Measures

Rigorous adherence to sterile procedures minimizes the risk of infection, which is crucial given the direct access to the pleural space and the potential introduction of pathogens. This includes the use of full barrier precautions, proper skin antisepsis, and the sterile handling of equipment throughout the procedure. Ensuring that clinicians are adequately trained in both the technical and anatomical aspects of chest tube placement reduces the risk of complications significantly. This training should encompass a thorough understanding of chest wall anatomy, appropriate site selection for tube insertion, and the proper technique for securing and maintaining the chest tube. Furthermore, using imaging guidance such as ultrasound during insertion can enhance accuracy and safety. Regular competency assessments and continuing education can help maintain high standards of practice. Additionally, the use of protocols and checklists can standardize procedures and reduce the likelihood of errors, contributing to improved patient outcomes and reduced complication rates. ([

68])

6.2. Management of Complications

Chest tube management also involves meticulous care to prevent complications such as tube dislodgment, infection, and re-expansion pulmonary edema.

Awareness of anatomical landmarks and the use of imaging guidance can reduce the risk of injuring the lung, diaphragm, or abdominal organs.

Misplaced tubes may require repositioning (i.e., partial withdrawal) or replacement, often guided by imaging techniques.

Antibiotic prophylaxis may be warranted in certain high-risk scenarios, and any signs of infection should prompt immediate evaluation and treatment.

Regular monitoring of the output, fluid characteristics, and imaging studies are essential to guide ongoing management and to determine the appropriate timing for tube removal.

Moreover, when chest tubes are used to drain pus and other infectious materials, the viscosity of the fluid and the potential presence of fibrinous materials can increase the risk of occlusion. To prevent the blockage of drainage, as well as to cleanse the pleural cavity, continuous or intermittent flushing is recommended. [

19]

6.3. Training, Learning, and Practicing Chest Tube Management

Acquiring the skills and undergoing training to place and manage a chest tube is a multifaceted process that combines theoretical knowledge, simulation-based practice, and clinical experience. Initially, trainees should understand the indications, contraindications, and anatomical considerations of chest tube insertion. Comprehensive knowledge of pleural anatomy and pathophysiology is essential, as it underpins the decision-making process and procedural steps involved in chest tube placement. Theoretical learning is often supported by detailed guidelines and instructional videos.

Simulation-based training plays a critical role in skill acquisition, providing a risk-free environment for trainees to practice the insertion technique. ([

69]) High-fidelity dummies and virtual reality simulators allow for repeated practice of needle insertion, guidewire manipulation, and catheter placement, helping trainees develop muscle memory and procedural confidence. Simulation also includes the use of bedside ultrasound, which is crucial for guiding the procedure and reducing complications such as organ puncture.

Hands-on clinical training, supervised by experienced physicians, is essential for translating simulation skills into real-world competence. During clinical rotations, trainees perform chest tube insertions on patients under direct supervision, receiving immediate feedback and guidance. This practical experience is invaluable for learning to manage complications, make quick and accurate decisions, and ensure patient safety.

Ongoing assessment and continuous professional development are integral to maintaining proficiency in chest tube management. Regular workshops, peer discussions, and advanced training courses help clinicians stay updated with the latest techniques and best practices. By integrating comprehensive theoretical education, hands-on practice, and continuous learning, clinicians are equipped to perform chest tube insertions safely and effectively, thereby improving patient outcomes in the management of pleural diseases.

A recent study investigated the state of training and experience among UK medical higher specialty trainees (HSTs) in performing Seldinger chest tube insertions in acute care settings. ([

70]) The authors found that non-respiratory trainees had fewer procedures, and lower confidence and knowledge, posing a training and service delivery challenge with significant patient safety implications. Addressing these gaps is crucial for improving outcomes in pleural disease management.

7. Conclusions

Chest tube thoracostomy and pleural drainage remain cornerstone interventions in the management of pleural effusion and pneumothorax. The evolution from ancient techniques to modern, sophisticated systems underscores the importance of continuous innovation and education in this field. Recent advances include the use of smaller bore catheters, which are less invasive and have shown similar efficacy to traditional chest tubes in select patients. Additionally, digital chest drainage systems offer real-time monitoring of intrapleural pressures and air leaks, enhancing clinical decision-making.

Ongoing research and technological advancements hold the promise of further improving the efficacy and safety of these critical procedures, ultimately enhancing patient outcomes in pleural disease management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S., N.M.R. and D.F-K.; methodology, C.S. and D.F-K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S., F.M., S.A, G.M. and M.M.; supervision, C.S., D.F-K and N.M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lobdell KW, Engelman DT. Chest Tube Management: Past, Present, and Future Directions for Developing Evidence-Based Best Practices. Innovations (Phila). 2023 Jan-Feb;18(1):41-48. [CrossRef]

- Christopoulou-Aletra H, Papavramidou N. “Empyemas” of the thoracic cavity in the Hippocratic Corpus. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008 Mar;85(3):1132-4. [CrossRef]

- Santoshi RK, Chandar P, Gupta SS, Kupfer Y, Wiesel O. From Chest Wall Resection to Medical Management: The Continued Saga of Parapneumonic Effusion Management and Future Directions. Cureus. 2022 Jan 7;14(1):e21017. [CrossRef]

- Desimonas N, Tsiamis C, Sgantzos M. The Innovated “Closed Chest Drainage System” of William Smoult Playfair (1871). Surg Innov. 2019 Dec;26(6):760-762. [CrossRef]

- Meyer JA. Gotthard Bülau and closed water-seal drainage for empyema, 1875-1891. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989 Oct;48(4):597-9. [CrossRef]

- Aboud FC, Verghese AC. Evarts Ambrose Graham, empyema, and the dawn of clinical understanding of negative intrapleural pressure. Clin Infect Dis. 2002 Jan 15;34(2):198-203. [CrossRef]

- Hughes RK. Thoracic trauma. Ann Thorac Surg. 1965 Nov;1(6):778-804. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heimlich HJ. Valve drainage of the pleural cavity. Dis Chest. 1968 Mar;53(3):282-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porcel JM. Chest Tube Drainage of the Pleural Space: A Concise Review for Pulmonologists. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2018 Apr;81(2):106-115. Epub 2018 Jan 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lococo F, Sorino C, Marchetti G, Feller-Kopman D. Chylothorax Associated With Indolent Follicular Lymphoma. In: Sorino C, Pleural diseases. p. 59-67, Elsevier Inc; 1st ed. 2021, ISBN: 9780323795418.

- Roberts ME, Rahman NM, Maskell NA, et al.; BTS Pleural Guideline Development Group. British Thoracic Society Guideline for pleural disease. Thorax. 2023 Jul;78(Suppl 3):s1-s42. [CrossRef]

- Zisis C, Tsirgogianni K, Lazaridis G, et al. Chest drainage systems in use. Ann Transl Med. 2015 Mar;3(3):43. [CrossRef]

- Sorino C, Squizzato A, Inzirillo F, Feller-Kopman D. Posttraumatic Hemothorax and Pneumothorax in a Patient on Oral Anticoagulant. In: Sorino C, Pleural diseases. p. 189-199, Elsevier Inc; 1st ed. 2021, ISBN: 9780323795418.

- Lee SA, Kim JS, Chee HK, et al. Clinical application of a digital thoracic drainage system for objectifying and quantifying air leak versus the traditional vacuum system: a retrospective observational study. J Thorac Dis. 2021 Feb;13(2):1020-1035. [CrossRef]

- Qiu Y, Zhou J, Wu D, et al. Suction versus non-suction drainage strategy after uniportal thoracoscopic lung surgery: a prospective cohort study. J Thorac Dis. 2024 Apr 30;16(4):2285-2295. Epub 2024 Mar 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Holbek BL, Christensen M, Hansen HJ, Kehlet H, Petersen RH. The effects of low suction on digital drainage devices after lobectomy using video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019 Apr 1;55(4):673-681. [CrossRef]

- Cerfolio RJ, Bass C, Katholi CR. Prospective randomized trial compares suction versus water seal for air leaks. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001 May;71(5):1613-7. [CrossRef]

- Gocyk W, Kużdżał J, Włodarczyk J, Grochowski Z, Gil T, Warmus J, Kocoń P, Talar P, Obarski P, Trybalski Ł. Comparison of Suction Versus Nonsuction Drainage After Lung Resections: A Prospective Randomized Trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016 Oct;102(4):1119-24. Epub 2016 Aug 23. [CrossRef]

- Asciak R, Bedawi EO, Bhatnagar R, et al. British Thoracic Society Clinical Statement on pleural procedures. Thorax. 2023 Jul;78(Suppl 3):s43-s68. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopra A, Doelken P, Hu K, Huggins JT, Judson MA. Pressure-Dependent Pneumothorax and Air Leak: Physiology and Clinical Implications. Chest. 2023 Sep;164(3):796-805. Epub 2023 May 13. [CrossRef]

- Walker SP, Hallifax R, Rahman NM, Maskell NA. Challenging the Paradigm of Persistent Air Leak: Are We Prolonging the Problem? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 Jul 15;206(2):145-149. [CrossRef]

- Adachi H, Wakimoto S, Ando K, et al. Optimal Chest Drainage Method After Anatomic Lung Resection: A Prospective Observational Study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2023 Apr;115(4):845-852. Epub 2022 Jul 19. [CrossRef]

- Petiot A, Tawk S, Ghaye B. Re-expansion pulmonary oedema. Lancet. 2018 Aug 11;392(10146):507. Epub 2018 Aug 9. [CrossRef]

- Walker S, Hallifax R, Ricciardi S, Fitzgerald D, et al. Joint ERS/EACTS/ESTS clinical practice guidelines on adults with spontaneous pneumothorax. Eur Respir J. 2024 May 28;63(5):2300797. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., et al. “Evaluating mechanical suction regulators in pleural drainage systems.” Thoracic Surgery Clinics 2021.

- Feller-Kopman D, Light R. Pleural Disease. N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 22;378(8):740-751. [CrossRef]

- Korczyński P, Górska K, Konopka D, Al-Haj D, Filipiak KJ, Krenke R. Significance of congestive heart failure as a cause of pleural effusion: Pilot data from a large multidisciplinary teaching hospital. Cardiol J. 2020;27(3):254-261. [CrossRef]

- Porcel JM. Pleural effusions from congestive heart failure. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010 Dec;31(6):689-97. [CrossRef]

- Ferreiro L, Porcel JM, Valdés L. Diagnosis and Management of Pleural Transudates. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017 Nov;53(11):629-636. English, Spanish. Epub 2017 Jun 19. [CrossRef]

- Walker SP, Bintcliffe O, Keenan E, et al. Randomised trial of indwelling pleural catheters for refractory transudative pleural effusions. Eur Respir J. 2022 Feb 24;59(2):2101362. [CrossRef]

- Porcel JM. Management of refractory hepatic hydrothorax. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2014 Jul;20(4):352-7. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert CR, Shojaee S, Maldonado F, Yarmus LB, Bedawi E, Feller-Kopman D, Rahman NM, Akulian JA, Gorden JA. Pleural Interventions in the Management of Hepatic Hydrothorax. Chest. 2022 Jan;161(1):276-283. Epub 2021 Aug 12. [CrossRef]

- Kuhajda I, Zarogoulidis K, Kougioumtzi I, Huang H, Li Q, Dryllis G, Kioumis I, Pitsiou G, Machairiotis N, Katsikogiannis N, Papaiwannou A, Lampaki S, Papaiwannou A, Zaric B, Branislav P, Porpodis K, Zarogoulidis P. Tube thoracostomy; chest tube implantation and follow up. J Thorac Dis. 2014 Oct;6(Suppl 4):S470-9. [CrossRef]

- Terra RM, Dela Vega AJM. Treatment of malignant pleural effusion. J Vis Surg. 2018 May 22;4:110. [CrossRef]

- Dresler CM, Olak J, Herndon JE 2nd, Richards WG, et al.; Cooperative Groups Cancer and Leukemia Group B; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; North Central Cooperative Oncology Group; Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Phase III intergroup study of talc poudrage vs talc slurry sclerosis for malignant pleural effusion. Chest. 2005 Mar;127(3):909-15. [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar R, Piotrowska HEG, Laskawiec-Szkonter M, et al. Effect of Thoracoscopic Talc Poudrage vs Talc Slurry via Chest Tube on Pleurodesis Failure Rate Among Patients With Malignant Pleural Effusions: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020 Jan 7;323(1):60-69. [CrossRef]

- Rahman NM, Pepperell J, Rehal S, et al. Effect of Opioids vs NSAIDs and Larger vs Smaller Chest Tube Size on Pain Control and Pleurodesis Efficacy Among Patients With Malignant Pleural Effusion: The TIME1 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015 Dec 22-29;314(24):2641-53. Erratum in: JAMA. 2016 Feb 16;315(7):707. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.0428. Erratum in: JAMA. 2016 Apr 19;315(15):1661. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.3928. [CrossRef]

- Sorino C, Mondoni M, Lococo F, Marchetti G, Feller-Kopman D. Optimizing the management of complicated pleural effusion: From intrapleural agents to surgery. Respir Med. 2022 Jan;191:106706. [CrossRef]

- Mondoni M, Saderi L, Trogu F, Terraneo S, Carlucci P, Ghelma F, Centanni S, Sotgiu G. Medical thoracoscopy treatment for pleural infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2021 Apr 20;21(1):127. [CrossRef]

- Bedawi EO, Ricciardi S, Hassan M, et al. ERS/ESTS statement on the management of pleural infection in adults. Eur Respir J. 2023 Feb 2;61(2):2201062. [CrossRef]

- Elsheikh A, Bhatnagar M, Rahman NM. Diagnosis and management of pleural infection. Breathe (Sheff). 2023 Dec;19(4):230146. Epub 2024 Jan 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman NM, Maskell NA, West A, et al. Intrapleural use of tissue plasminogen activator and DNase in pleural infection. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 11;365(6):518-26. [CrossRef]

- Mei F, Rota M, Bonifazi M, Zuccatosta L, Porcarelli FM, Sediari M, Bedawi EO, Sundaralingam A, Addala D, Gasparini S, Rahman NM. Efficacy of Small versus Large-Bore Chest Drain in Pleural Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Respiration. 2023;102(3):247-256. [CrossRef]

- Rösch RM. From diagnosis to therapy: the acute traumatic hemothorax - an orientation for young surgeons. Innov Surg Sci. 2024 Feb 16;8(4):221-226. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert RW, Fontebasso AM, Park L, Tran A, Lampron J. The management of occult hemothorax in adults with thoracic trauma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020 Dec;89(6):1225-1232. [CrossRef]

- Bauman ZM, Kulvatunyou N, Joseph B, et al. Randomized Clinical Trial of 14-French (14F) Pigtail Catheters versus 28-32F Chest Tubes in the Management of Patients with Traumatic Hemothorax and Hemopneumothorax. World J Surg. 2021 Mar;45(3):880-886. [CrossRef]

- Zeiler J, Idell S, Norwood S, Cook A. Hemothorax: A Review of the Literature. Clin Pulm Med. 2020 Jan;27(1):1-12. Epub 2020 Jan 10. [CrossRef]

- Patel NJ, Dultz L, Ladhani HA, Cullinane DC, Klein E, McNickle AG, Bugaev N, Fraser DR, Kartiko S, Dodgion C, Pappas PA, Kim D, Cantrell S, Como JJ, Kasotakis G. Management of simple and retained hemothorax: A practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. Am J Surg. 2021 May;221(5):873-884. [CrossRef]

- Pastoressa M, Ma T, Panno N, Firstenberg M. Tissue plasminogen activator and pulmozyme for postoperative-retained hemothorax: A safe alternative to postoperative re-exploration. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2017 Apr-Jun;7(2):122-125. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Janowak CF, Becker BR, Philpott CD, Makley AT, Mueller EW, Droege CA, Droege ME. Retrospective Evaluation of Intrapleural Tissue Plasminogen Activator With or Without Dornase Alfa for the Treatment of Traumatic Retained Hemothorax: A 6-Year Experience. Ann Pharmacother. 2022 Feb 20:10600280221077383. [CrossRef]

- Bintcliffe OJ, Hallifax RJ, Edey A, Feller-Kopman D, Lee YC, Marquette CH, Tschopp JM, West D, Rahman NM, Maskell NA. Spontaneous pneumothorax: time to rethink management? Lancet Respir Med. 2015 Jul;3(7):578-88. [CrossRef]

- MacDuff A, Arnold A, Harvey J; BTS Pleural Disease Guideline Group. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax. 2010 Aug;65 Suppl 2:ii18-31. [CrossRef]

- Collins CD, Lopez A, Mathie A, Wood V, Jackson JE, Roddie ME. Quantification of pneumothorax size on chest radiographs using interpleural distances: regression analysis based on volume measurements from helical CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995 Nov;165(5):1127-30. [CrossRef]

- Brown SGA, Ball EL, Perrin K, et al.; PSP Investigators. Conservative versus Interventional Treatment for Spontaneous Pneumothorax. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jan 30;382(5):405-415. [CrossRef]

- Shorthose M, Barton E, Walker S. The contemporary management of spontaneous pneumothorax in adults. Breathe (Sheff). 2023 Dec;19(4):230135. [CrossRef]

- Feller-Kopman D, Light RW. Advances in the management of pneumothorax. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10(5):431-441. [CrossRef]

- Maskell NA, Medford ARL. Outpatient management of pneumothorax: Portable air leak devices. Thorax. 2023;78(4):307-310. [CrossRef]

- Havelock T, Teoh R, Laws D, Gleeson F; BTS Pleural Disease Guideline Group. Pleural procedures and thoracic ultrasound: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax. 2010 Aug;65 Suppl 2:ii61-76. [CrossRef]

- Bowness J, Kilgour PM, Whiten S, Parkin I, Mooney J, Driscoll P. Guidelines for chest drain insertion may not prevent damage to abdominal viscera. Emerg Med J. 2015 Aug;32(8):620-5. [CrossRef]

- Marchetti G, Sorino C, Negri S, Pinelli V. Pyopneumothorax in Necrotizing Pneumonia With Bronchopleural Fistula. In: Sorino C, Pleural diseases. p. 101-111, Elsevier Inc; 1st ed. 2021, ISBN: 9780323795418.

- Bosman A, de Jong MB, Debeij J, van den Broek PJ, Schipper IB. Systematic review and meta-analysis of antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent infections from chest drains in blunt and penetrating thoracic injuries. Br J Surg. 2012 Apr;99(4):506-13. [CrossRef]

- McElnay PJ, Lim E. Modern Techniques to Insert Chest Drains. Thorac Surg Clin. 2017 Feb;27(1):29-34. [CrossRef]

- John M, Razi S, Sainathan S, Stavropoulos C. Is the trocar technique for tube thoracostomy safe in the current era? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014 Jul;19(1):125-8. [CrossRef]

- Adlakha S, Roberts M, Ali N. Chest tube insertion. Eur Respir Monogr. 2016;74:229–239.

- Ringel Y, Haberfeld O, Kremer R, Kroll E, Steinberg R, Lehavi A. Intercostal chest drain fixation strength: comparison of techniques and sutures. BMJ Mil Health. 2021 Aug;167(4):248-250. [CrossRef]

- Asciak R, Addala D, Karimjee J, Rana MS, Tsikrika S, Hassan MF, Mercer RM, Hallifax RJ, Wrightson JM, Psallidas I, Benamore R, Rahman NM. Chest Drain Fall-Out Rate According to Suturing Practices: A Retrospective Direct Comparison. Respiration. 2018;96(1):48-51. [CrossRef]

- Mercer RM, Mishra E, Banka R, et al. A randomised controlled trial of intrapleural balloon intercostal chest drains to prevent drain displacement. Eur Respir J. 2022 Jul 21;60(1):2101753. [CrossRef]

- Shafiq M, Russo S, Davis J, Hall R, Calhoun J, Jasper E, Berg K, Berg D, O’Hagan EC, Riesenberg LA. Development and content validation of the checklist for assessing placement of a small-bore chest tube (CAPS) for small-bore chest tube placement. AEM Educ Train. 2023 Mar 22;7(2):e10855. [CrossRef]

- Berger M, Weber L, McNamara S, Shin-Kim J, Strauss J, Pathak S. Simulation-Based Mastery Learning Course for Tube Thoracostomy. MedEdPORTAL. 2022 Jul 26;18:11266. [CrossRef]

- Probyn B, Daneshvar C, Price T. Training, experience, and perceptions of chest tube insertion by higher speciality trainees: implications for training, patient safety, and service delivery. BMC Med Educ. 2024 Jan 3;24(1):12. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).