1. Introduction

Hypercholesterolemia is a major risk factor in atherosclerosis, and guidelines recommend its aggressive reduction to prevent severe diseases like myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke and more[

1]. Statins (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors ) are a cornerstone of this reduction, their use being highly recommended[

2]. However, statin-associated myopathy is a frequent side effect, whose frequency has been estimated in 10%-25% of the cases, that often forces to stop their assumption[

3,

4]. Currently, several alternative treatments are available in cases of statin intolerance, including ezetimibe, anti PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies, inclisiran, and bempedoic acid[

5,

6]. However, non-statin treatments are expensive, and their widespread use would probably not be sustainable for health systems, both of developing countries and of western countries as well [

7,

8,

9]. As an example,

Table 1 shows the cost of some cholesterol-lowering treatments in Italy. Our group and others have shown that creatine, a widespread nutritional supplement, is able to counter statin toxicity and to prevent or reduce statin-associated myopathy[

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Supplementation of creatine is safe[

11], moreover one month of creatine supplementation at the dose of 3 g/day (the dose we used in the present study) costs in Italy about € 15/month (see for example [

16]). Thus, creatine supplementation may represent an alternative to expensive cholesterol-lowering drugs in some cases of statin-associated myopathy. From this point of view, an issue to be considered is that creatine is usually administered at relatively high doses, for example Shewmon and Craig in the paper that initially reported its effectiveness in statin myopathy used creatine, 5 g twice daily for 5 days (creatine loading) followed by creatine, 5 g/day as a continuation. In Italy the Ministry of Health recommends creatine supplementation to the maximum dose of 6g/day for one month, 3g/day as a long-term therapy[

17]. Thus, we carried out this preliminary study to investigate if such a relatively low dose of creatine might be sufficient to counter the symptoms of statin-associated myopathy.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was preliminarily approved by our regional Ethics Committee. Patients were referred to this study from the outpatient services of either the Cardiology or the Neurology outpatient services of our hospital. All patients were in charge to the outpatient service for prevention of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular ischemic disease, or both.

Table 2 lists inclusion and exclusion criteria, and preset criteria for study withdrawal.

Serum creatinine, cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol and creatine kinase (CK) were assessed at baseline, and so was creatinine clearance (Cockcroft-Gault formula). Patients had to be intolerant to at least one statin to enter the trial (see

Table 2). After enrollment, the statin was stopped, and creatine was administered at a loading dose of 2g t.i.d. for 7 days. Afterwards, the same statin was resumed at the same dosage, and creatine supplementation was continued at the dose of 1g t.i.d. for 4 months. Patients were visited each month. At each visit, history was taken, a physical and a neurological examination were carried out, and a survey of muscle symptoms was performed. Additionally, at each visit the Shewmon and Craig’s “myopathy score”[

10] was calculated. The latter takes into consideration muscle pain, muscle weakness and cramps severity (i.e. cramps frequency, duration and painfulness). The severity of each symptom is gauged by the patient in the 0-10 range by drawing a cross along a horizontal line, graduated from 0 to 10. All scores had to be whole numbers; decimals were not allowed. The sum of the three scores was the “myopathy score”. Additionally, we carried out the following biochemical evaluations: at the month 1 visit, serum creatinine; at month 2, serum creatinine, total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, CK; at month 3, serum creatinine; at month 4, serum creatinine, total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, CK. The primary endpoint was to verify whether at least half of the patients treated with creatine and the statin, to which they were intolerant, completed the study. Secondary endpoints were: (1) difference in Shewmon and Craig’s “myopathy scores” between baseline and visit 4, and (2) difference in serum CK values between baseline and visit 4. All patients were given a commercially available preparation (Novacrea

®), containing 1g creatine monohydrate, 0.5g honey and excipients in the form of chewable tablets.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.0.0 for Windows, GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts USA,

www.graphpad.com. We chose not parametric statistics because the small size of the sample does not allow to assume a gaussian distribution.

3. Results

3.1. Patients, General Data

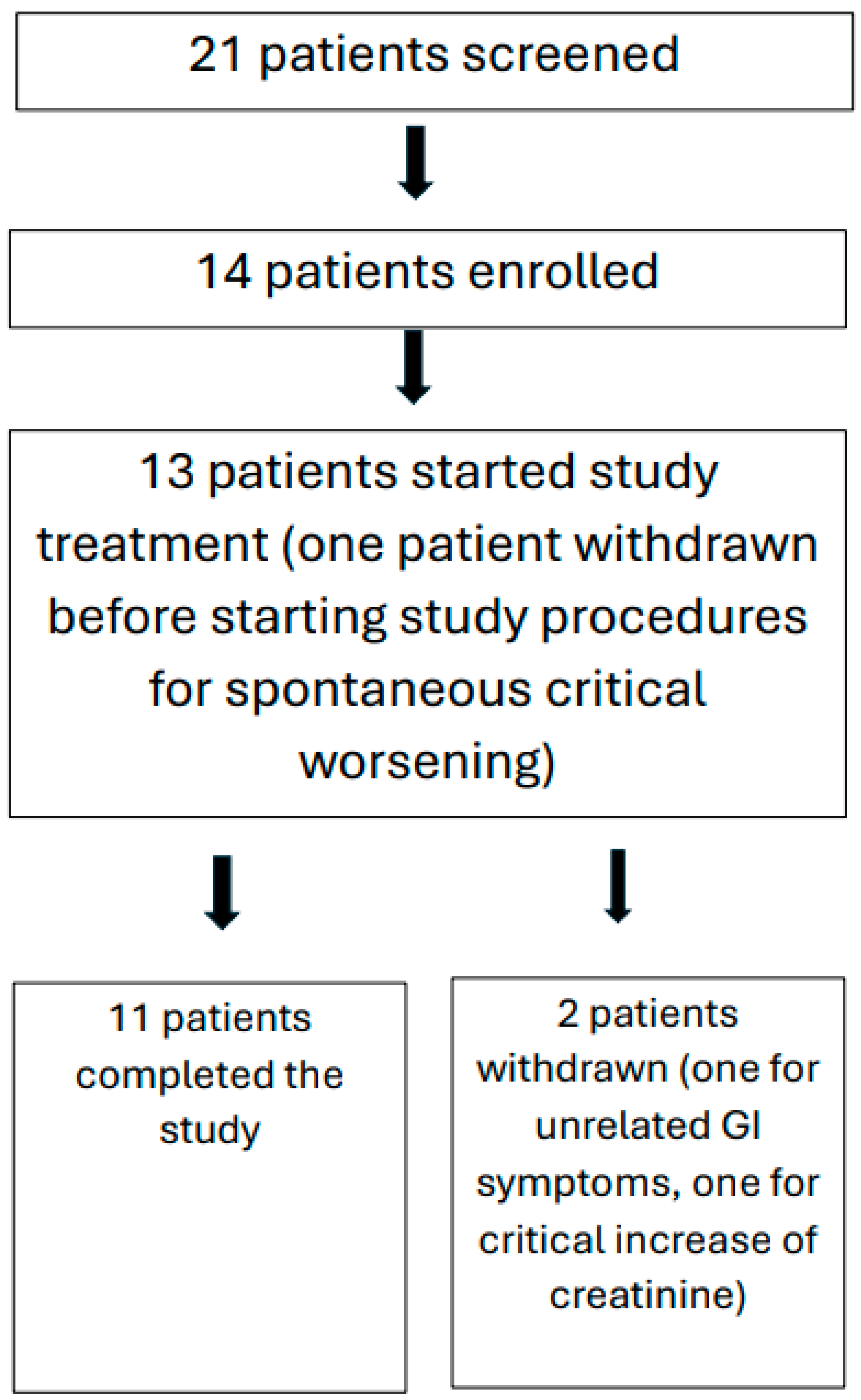

A total of 21 patients were screened, 13 females and 8 males, aged 53 to 81 years. Of these:

- Five patients were excluded at screening because they did not meet inclusion criteria.

- Two patients were excluded at screening because they were assuming red rice supplements instead of statins.

Of the remaining 14 patients that were enrolled, 3 patients had to be withdrawn from the study for the following reasons. One male patient was withdrawn after the screening evaluation, before beginning of study treatment, because serum CK rose to >1200 U/L; one female patient was withdrawn because of gastrointestinal symptoms that occurred after two months supplementation; such symptoms were of rather acute onset and were judged to be of infectious (probably viral) etiology, unrelated to creatine supplementation. Another female patient was withdrawn due to worsening of renal function above 1.5 times the ULN of creatinine (see preset criteria for study withdrawal in

Table 2).

Finally, 11 enrolled patients completed the study. Of them, 6 were taking Rosuvastatin, 4 were taking Atorvastatin, 1 was taking Simvastatin.

Figure 1 graphically represents these data.

Four patients were taking statin in primary prevention of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseaes; 5 patients were taking statin in secondary prevention for ischemic heart disease (all had had myocardial infarction and coronary stent placement); 2 patients were taking statin in secondary prevention of ischemic stroke (1 had had middle cerebral artery occlusion, 1 had had Percheron's artery occlusion).

The most frequent comorbidities were high blood pressure, overweight, and diabetes mellitus. None had personal nor family history of neuromuscular diseases.

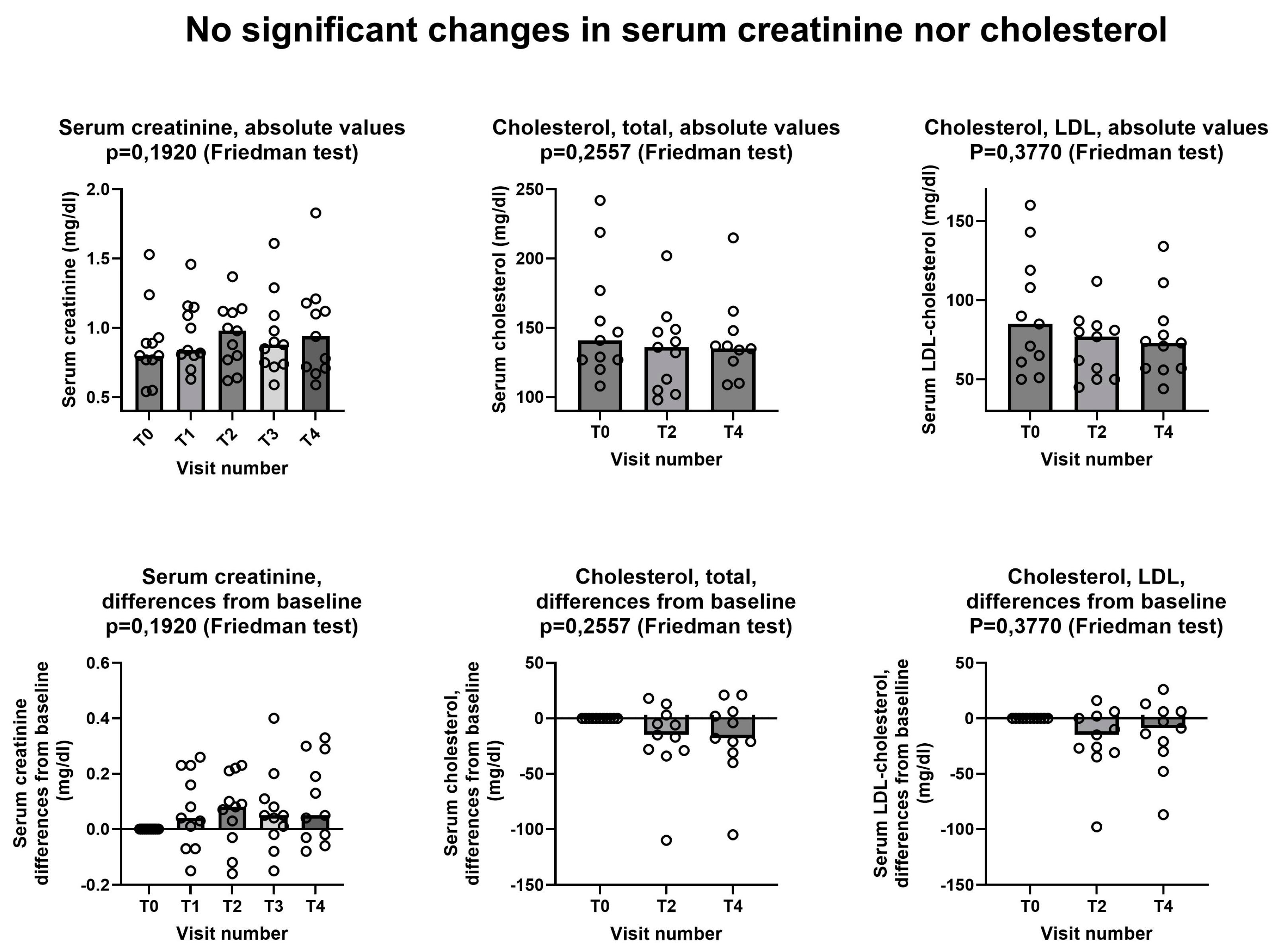

3.2. Creatinine and Cholesterol Dosages

Figure 2 shows that no significant changes were observed in neither serum creatinine nor in serum cholesterol, either total cholesterol or LDL-cholesterol. Creatinine data are in agreement with literature data, including the literature review by two of us, showing that creatine supplementation does not cause kidney damage [

11,

23,

24]. The fact that both total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol did not increase during the study confirms that, as one might have expected, the one-week stop of statin assumption at the beginning of the study does not affect adversely the level of cholesterol in the blood.

3.3. Effects on Statin Myopathy

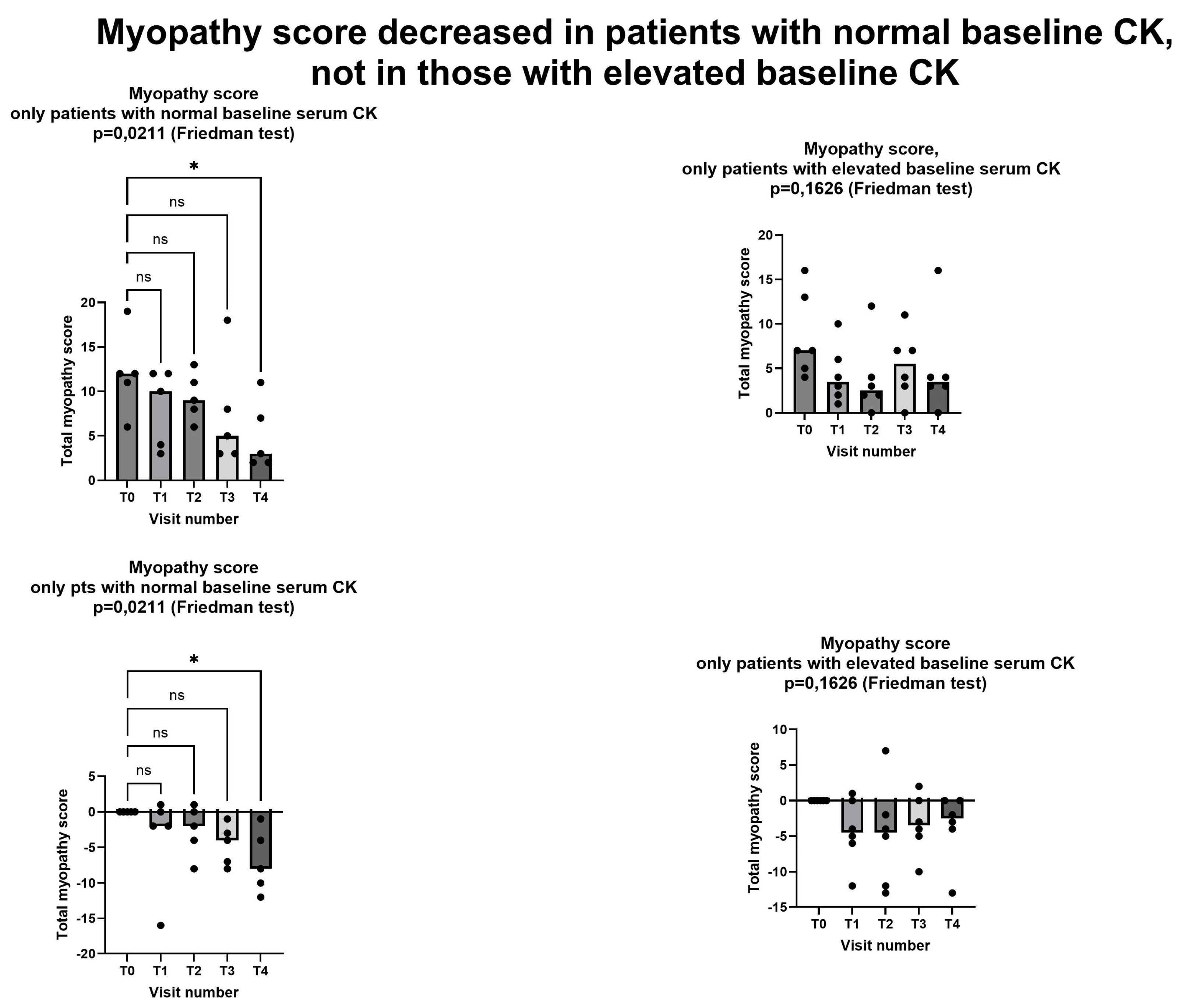

3.2.1. Myopathy Score

Figure 3 shows that Shewmon and Craig’s “myopathy score”[

10] significantly decreased during the study period, with scores at the fourth month being significantly lower than at baseline. The average decrease was -5.2 points between T0 and T4. It is noteworthy that in 6 out of the 11 patients the decrease at T4 compared was greater than 50% compared to baseline, representing a substantial and clinically significant decrease. No patient had a myopathy score higher at T4 than it was at T0.

Since elevated baseline CK is probably a marker of more severe myopathy, we considered the effects of creatine supplementation separately in the 5 patients with and in the 6 patients without elevated serum CK at baseline. Shewmon and Craig’s myopathy score [

10] decreased in a statistically significant way in patients with normal baseline CK, while the decrease did not reach statistical significant in those with abnormal baseline CK (

Figure 4).

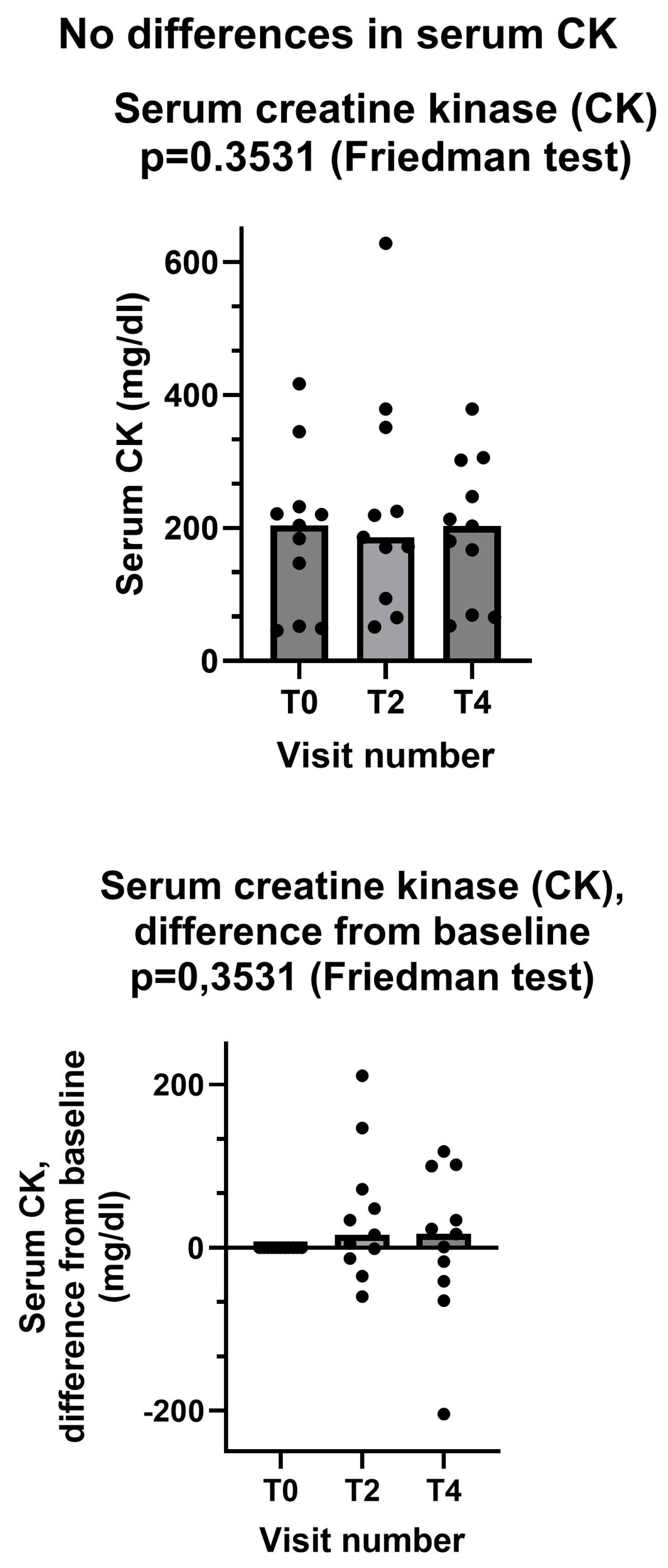

3.3.2. Serum Creatine Kinase

By contrast, serum creatine kinase did not show any change after creatine supplementation (

Figure 5). We should consider that only 6 patients has an abnormal CK value at baseline. In these 6 patients serum CK at baseline was (mean±standard deviation) 273±87 mg/dl. At the end of the study CK value was normalized in 2 patients, still in the abnormal range in 4 patients. In one patient serum CK was borderline but still within normal range at baseline (184 mg/dl), and it was abnormal (302 mg/dl) at the end of the study.

4. Discussion

This is a pilot study that was carried out to investigate the feasibility and possible effectiveness of low-dose creatine supplementation in statin myopathy. As a first endpoint, we tested whether at least half of the patients treated with creatine and the statin, to which they were intolerant, completed the study. The answer was positive, in fact 11 out of 13 patients who entered the active phase of the study (85%) completed the study (

Figure 1). We did not count in this computation the single patient that was withdrawn after enrollment but before starting study treatment, however the percentage of study completion remains very high (79%) if we include him. Of the few withdrawn patients, only one retired because of a creatine-related effect, i.e. increase of creatinine more than 1.5 its upper limit of normality (ULN). This effect is related to creatine because creatinine is the metabolite of creatine, thus it is prone to increase in the blood when blood creatine increases, as it is the cases during creatine supplementation [

25]. It is important to emphasize that this increase is not an index of kidney damage, being simply the consequence of increased blood creatine. To precisely investigate renal function and its possible changes during creatine supplementation, methods not relying on creatinine dosage should be used, the main one being plasma clearance of 51Cr-EDTA [

26,

27]. Nevertheless, it is prudent (1) not to prescribe creatine supplementation to patients with impaired renal function and (2) to stop creatine supplementation should serum creatinine raise to 1.5-2 times its ULN [

11]. However, it is important to note that in our study, that involved middle- and older-age patients, a very high percentage was able to complete the study without showing any significant creatinine increase.

As for the two secondary endpoints, we met the first one, insofar as after creatinine supplementation Shewmon and Craig’s “myopathy score” was significantly lower at T4 than at T0 (

Figure 3). This is an important finding, because it strongly suggests that creatine supplementation may indeed mitigate statin myopathy, as previous data already suggested [

10,

12,

13]. By contrast, we did not meet the other secondary endpoint, because CK was not statistically different at T4 compared to T0 (

Figure 5). It is important to note that CK elevation indicates a structural damage to muscle cells, namely a membrane breakdown that allows intracellular CK to leak into the bloodstream [

28]. Since not all patients with statin myopathy show elevated serum CK, and in fact statin myopathy can occur in the absence of clinically elevated CK [

29], it is easy to hypothesize that muscle pain is probably an early symptom of statin-associated myopathy and that it initially occurs in the absence of a structural damage to muscle cells, i.e. in the absence of CK serum elevation. In this early phase, our data strongly suggest that creatine supplementation may be capable of mitigating the clinical picture, and perhaps preventing further damage. By contrast, once structural muscle damage has occurred, i.e. after serum CK elevation, creatine supplementation is less effective (

Figure 4).

The main limitation of our study is its observational nature. Even with this limitation, our data strongly suggest that creatine supplementation may improve statin myopathy, especially in its milder and/or initial phase when serum CK is not elevated. Further research shall try to confirm our data in a randomized, controlled trial.

5. Conclusions

Our data confirm previous report showing that creatine supplementation is safe even in older subjects. Specifically, 2 g creatine t.i.d. for 1 week followed by 1 g. t.i.d. was well tolerated by most of our patients. Nevertheless, it is prudent not to administer it to patients with renal insufficiency, and to monitor serum creatinine during supplementation.

Moreover, this low-dose creatine supplementation may be capable to significantly improve the symptoms of statin myopathy, especially in the milder and/or earlier stage when serum CK is not elevated.

Creatine supplementation may be a feasible option to allow continuation of statin treatment, thus preventing or delaying prescription of second-line anti-cholesterol treatments, whose high cost is problematic for developed countries and even more for emerging economies (see above,

Table 1) [

7].

Further research should be done to hopefully further confirm these findings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. The full database is available as supplementary material online.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Enrico Adriano and Maurizio Balestrino; Data curation, Elena Scarsi; Formal analysis, Elena Scarsi and Maurizio Balestrino; Funding acquisition, Maurizio Balestrino; Investigation, Elena Scarsi, Ulrico Dorighi, Marina Grandis and Maurizio Balestrino; Methodology, Maurizio Balestrino; Project administration, Elena Scarsi and Maurizio Balestrino; Resources, Enrico Adriano and Maurizio Balestrino; Supervision, Marina Grandis and Maurizio Balestrino; Writing – original draft, Elena Scarsi and Maurizio Balestrino; Writing – review & editing, Elena Scarsi, Ulrico Dorighi, Enrico Adriano and Marina Grandis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente) and by the IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino (Genoa, Italy).

Institutional Review Board Statement

the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ligurian region (N. Registro CER Liguria: 610/2021 - DB id 11868).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The whole database is provided as supplementary material to this article.

Acknowledgments

we thank NovaNeuro Srl for donating the creatine preparation we used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. EA and MB are founding members of NovaNeuro Srl, a University of Genoa spinoff that produces Novacrea, the creatine supplement that was used in this study.

References

- ESC Guidelines on Dyslipidaemias (Management Of). Available online: https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Dyslipidaemias-Management-of (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Bansal, A.B.; Cassagnol, M. HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitors. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vinci, P.; Panizon, E.; Tosoni, L.M.; Cerrato, C.; Pellicori, F.; Mearelli, F.; Biasinutto, C.; Fiotti, N.; Di Girolamo, F.G.; Biolo, G. Statin-Associated Myopathy: Emphasis on Mechanisms and Targeted Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 11687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckert, E.; Hayem, G.; Dejager, S.; Yau, C.; Bégaud, B. Mild to Moderate Muscular Symptoms with High-Dosage Statin Therapy in Hyperlipidemic Patients--the PRIMO Study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2005, 19, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscoli, S.; Ifrim, M.; Russo, M.; Candido, F.; Sanseviero, A.; Milite, M.; Di Luozzo, M.; Marchei, M.; Sangiorgi, G.M. Current Options and Future Perspectives in the Treatment of Dyslipidemia. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elis, A. Current and Future Options in Cholesterol Lowering Treatments. European Journal of Internal Medicine 2023, 112, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garattini, L.; Padula, A. Cholesterol-Lowering Drugs: Science and Marketing. J R Soc Med 2017, 110, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, J. The Cost of High Cholesterol Available online:. Available online: https://www.webmd.com/cholesterol-management/cost-high-cholesterol (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Current Indications, Cost, and Clinical Use of Anti-PCSK9 Monoclonal Antibodies. Available online: https://www.acc.org/Latest-in-Cardiology/Articles/2016/05/18/14/34/http%3a%2f%2fwww.acc.org%2fLatest-in-Cardiology%2fArticles%2f2016%2f05%2f18%2f14%2f34%2fCurrent-Indications-Cost-and-Clinical-Use-of-Anti-PCSK9-Monoclonal-Antibodies (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Shewmon, D.A.; Craig, J.M. Creatine Supplementation Prevents Statin-Induced Muscle Toxicity. Ann Intern Med 2010, 153, 690–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balestrino, M.; Adriano, E. Beyond Sports: Efficacy and Safety of Creatine Supplementation in Pathological or Paraphysiological Conditions of Brain and Muscle. Med Res Rev 2019, 39, 2427–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balestrino, M.; Adriano, E. Statin-Induced Myopathy Prevented by Creatine Administration. BMJ Case Rep 2018, 2018, bcr-2018–225395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balestrino, M.; Adriano, E. Creatine as a Candidate to Prevent Statin Myopathy. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neu, A.; Hornig, S.; Sasani, A.; Isbrandt, D.; Gerloff, C.; Tsikas, D.; Schwedhelm, E.; Choe, C.-U. Creatine, Guanidinoacetate and Homoarginine in Statin-Induced Myopathy. Amino Acids 2020, 52, 1067–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasani, A.; Hornig, S.; Grzybowski, R.; Cordts, K.; Hanff, E.; Tsikas, D.; Böger, R.; Gerloff, C.; Isbrandt, D.; Neu, A.; et al. Muscle Phenotype of AGAT- and GAMT-Deficient Mice after Simvastatin Exposure. Amino Acids 2020, 52, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NEOVIS PLUS 20 BUSTINE. Available online: https://www.basefarma.it/neovis-plus-20-bustine (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Italian Ministry of Health Altri Nutrienti e Altre Sostanze Ad Effetto Nutritivo o Fisiologico (Revisione Ottobre 2022). Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pagineAree_1268_4_file.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Cerca Un Farmaco. Available online: https://www.federfarma.it/Farmaci-e-farmacie/Cerca-un-farmaco.aspx (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Netribe Business Solutions Srl Ezetimibe - Area Farmacisti - Farmacie Comunali Riunite. Available online: https://fcrinforma.fcr.re.it/ezetimibe (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2023-01-27&atto.codiceRedazionale=23A00339&elenco30giorni=false (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2022/06/15/22A03455/sg (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Gazzetta Ufficiale della Rebubblica Italiana. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2022/10/03/22A05449/sg (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Longobardi, I.; Gualano, B.; Seguro, A.C.; Roschel, H. Is It Time for a Requiem for Creatine Supplementation-Induced Kidney Failure? A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creatine. Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements-creatine/art-20347591 (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Wyss, M.; Kaddurah-Daouk, R. Creatine and Creatinine Metabolism. Physiol Rev 2000, 80, 1107–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugaresi, R.; Leme, M.; de Salles Painelli, V.; Murai, I.H.; Roschel, H.; Sapienza, M.T.; Lancha Junior, A.H.; Gualano, B. Does Long-Term Creatine Supplementation Impair Kidney Function in Resistance-Trained Individuals Consuming a High-Protein Diet? J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2013, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, F.S.R.; Sapienza, M.T.; Prado, E.S.; Agena, F.; Shimizu, M.H.M.; Lemos, F.B.C.; Buchpiguel, C.A.; Ianhez, L.E.; David-Neto, E. Validation of Plasma Clearance of 51Cr-EDTA in Adult Renal Transplant Recipients: Comparison with Inulin Renal Clearance. Transpl Int 2009, 22, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aujla, R.S.; Zubair, M.; Patel, R. Creatine Phosphokinase. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, B.A.; Thompson, P.D. Statin-Associated Muscle Disease: Advances in Diagnosis and Management. Neurotherapeutics 2018, 15, 1006–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).