1. Introduction

Charitable contributions from the public (e.g., donations or volunteering) are important for sustaining non-profit organizations (NPO) that play an important role in the development of a society, especially in least developed countries, where many products and services that the public needs are insufficient. However, the question is how far or how long will the support or services be provided by the NPOs? What NPOs can do to ensure the sustainable support from donors remains an open and important question (i.e., White & Peloza, 2009; Xie & Bagozzi, 2014). Answers regarding how to motivate individuals giving to NPOs have not been sufficiently considered by researchers, including NPOs themselves.

Emotion is one of factor generally used to encourage people to donate (Batson, Sager, et al., 1997). Charitable organizations are proposed to exploit emotions via persuasive appeals to gain individuals' support (Bagozzi & Moore, 1994). Feeling pity for someone who is in need, for instance, was the leading factor to motivate people to help another person (Batson et al., 1983; Dickert et al., 2011; S. J. Kim & Kou, 2014). Though there is a relationship between compassion and reported donation to conservation charities (Pfattheicher et al., 2015 as cited by Young et al., 2018), whether the empathy which is aroused by exposure to suffering of animals lead to actual donations towards helping the animals remains empirically unverified.

Nature may be used to trigger positive and altruistic emotions and according to Weinstein et al., (2009), subjects more immersed in natural settings were more generous. Exposure to nature reduces stress (Bakir-Demir et al., 2021) and leads to pro-social behaviors (Mayer & Frantz, 2004), such as increasing charitable donations (Castelo et al., 2021) and this is still the case where the immersion was made via video (Piff et al., 2015). Subjects in experimental settings treated to view natural beauty also reported greater pro-social tendencies (Zhang et al., 2014). So, there are indications of a direct effect from being exposed to nature on prosocial behaviors. However, whether variation in pro-social behavior is explained more by being exposure to nature or to humans remains less clear.

The present study used other-benefit appeals (i.e., White & Peloza, 2009), as an intervention to evoke empathy. We extended the study of N. Kim, 2014 by testing the types of non-profit advertisements that are more effective in generating actual charitable giving.

2. Theories and Hypotheses

Several researchers have found support for the hypothesis of empathy-altruism (i.e., Schroeder et al., 1988; R. Cialdini et al., 1989; Batson et al., 1991; Batson, Polycarpou, et al., 1997; Batson & Ahmad, 2001; Snyder & Lopez, 2002; FeldmanHall et al., 2015; Piff et al., 2015; Milaniak et al., 2018) which means that empathy is the source of altruistic motivation. Thus, the greater empathy is, the greater the altruistic motivation will be, resulting in pro-social behaviors (Batson et al., 1981; Toi & Daniel Batson, 1982; Batson, 1987; Batson, 2014). In the case where subjects are exposed to two different sadness-inducing ads (i.e., empathy aroused by human suffering vs. empathy aroused by animal suffering), we believe that the subject’s pro-social act, the donating behavior, is unlikely different as the behaviors are similarly influenced by the intensity of the empathy aroused by each ad (Hypothesis 1).

Just like empathy, personal values, the guiding principles in people’s lives, could drive a person’s actions (Schwartz, 1992). Although there is a gap (i.e., Stern et al., 1999), personal values influenced various types of behavior (Roccas & Sagiv, 2010; Maio, 2011; Sagiv et al., 2011). Two dimensions of human values (i.e. universalism and benevolence) have been shown to be positively correlated with the intention to donate to cancer research (e.g., Maio & Olson, 1995; Sagiv et al., 2011). Sneddon et al., (2020) have argued that the focus must be more on donor’s values as the elicitation of emotion is, to a certain degree, moderated by values (Wymer & Gross, 2023). So, a donation difference is likely detected if the empathy is moderated by the subject’s personal values which were found affecting behaviors (for a review, see Roccas & Sagiv, 2010; Maio, 2011; Sagiv et al., 2011).

Personality also plays a role. Some people are more inclined to altruism, while the others are more likely prone to egoism or hedonism (self-interest or selfism) (Wesley Schultz, 2000; Steg et al., 2014; Ros & Kaneko, 2022). Whether more self-interested subjects are likely to abstain or donate to a charity remains understudied and untested. Moreover, whether egoistic values moderate the effect of empathy evoked by sadness-inducing ads is as of yet empirically unknown. It seems necessary to find out whether egoistic subjects primed to have empathic feeling will keep more for themselves or donate more to a charity (Hypothesis 2).

3. Materials

This experimental study was conducted in May 2022 and targeted teacher students or pre-service teachers (N = 350) who were randomly selected from two colleges, the Teacher Education College in [

1] Phnom Penh capital (N = 166/732) and [

2] Battambang province (N = 184/722) in Cambodia. Teacher students are those who take responsibility for improving teaching effectiveness by modifying teacher’s behaviors. In addition to knowledge and skills, an ideal teacher should be a person who is flexible and open-minded, who encourages and cares for students and has a harmonious relationship with students (Keeley et al., 2006; Komarraju, 2013). The caring behavior of the teacher appears to be the dominant predictor of students’ satisfaction, according to Geier (2021). However, whether an ideal teacher is selfless or not is the question central to the present study. The sample was 72.2% female, and the average age was 21.87 years (SD = 2.08) (For descriptive statistics, see

SI Table S1).

3.1. Experimental Procedures

First, research subjects of the study were asked to sit indoors in front of a desktop. After providing informed consent, the 350 randomly selected subjects were once again randomly assigned to watch one of three five-minute videos, [

1]: a human suffering sadness inducing video (N = 143 as Testing 1) and [

2]: an animal suffering sadness inducing video (N = 119 as Testing 2), and video on a lecture about the environment (N = 88 as Control).

After watching the video, subjects were asked to play a game known as ‘Charitable Giving Dictator Game’ which has been found to have an important influence on prosocial behaviors (Edele et al., 2013; Batson & Ahmad, 2001; Batson & Moran, 1999; Pelligra, 2011; Pelligra & Vásquez, 2020). In the game, subjects were required to choose between a list of worthy charities and stipulate an amount they would be willing to donate (Kamas & Preston, 2021). The participants were then asked to complete another series of questions related to behavioral variables (religious practices; experience in pro-environmental and pro-social practices, including hard practices such as blood donation (i.e., Neaman et al., 2018); nature connections; national pride; gender, age, marital status; education; part-time job; etc.; and personal values. Qualtrics was the only software employed in the study (

SI Appendix).

The research was also designed to avoid undue influence, which could result from [

1] a decision made as a group representative (Dannenberg & Martinsson, 2021), [

2] a decision made under the observation of friends or family (Meyer & Tripodi, 2021) and [

3] a decision made under a situation where most others also donate (R. B. Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004; Everett et al., 2015 as cited by Jaeger & van Vugt, 2022; Krupka & Weber, 2009).

3.2. Stimulus Material

Two original videos from two non-profit organizations (NPOs) operating in Cambodia, the Cambodian Children’s Fund (CCF) and the Wildlife Alliance (WA), were used as baits for responses varying in empathy. The videos were purposively produced to elicit financial support. Different from the video used by N. Kim (2014), these two five-minute videos showed a helped beneficiary, but one beneficiary was human, a suffering girl, while the other was a suffering wild elephant. The third video was on a lecture of environment where it was used as Control to be compared with the two testing groups (see

SI Stimulus Material).

3.3. Manipulation

The present study used 12 items adopted from Davis, 1980 & Davis, 1983’s Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) as cited by Tam (2013) to gauge subjects’ empathy evoked by emotional videos (example item: To what extent do you agree with the emotive statements while watching the video? Responses were given on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1: strongly disagree to 7: strongly agree). The scale was combined from two subscales, empathic concern and perspective taking, which were found significantly relevant to empathy (i.e., Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004; Jolliffe & Farrington, 2006; Konrath et al., 2011 as cited by Tam, 2013). These 12 items were merged into one construct, namely dispositional empathy with nature (Tam, 2013), which assessed to be valid as the eigen value was λ = 6.46 and the average empathy was M = 5.68. The internal reliability of this measure was also very high as well with ∝ = 0.929 (

SI Table S2).

As cited by Vitaglione & Barnett (2003), Hechler & Kessler (2018) and Keck (2019), an individual, on behalf of a particular suffering victim, may feel angry at a transgressor if he or she attributes the cause of a person’s suffering to another person (a “transgressor”). Similarly, when a victim shows some signs of relief or joy after receiving help, the helper may also feel relieved (Hoffman, 1981). It is therefore necessary, in addition to empathy, subjects were asked to report other affective states, such as empathic anger and empathic joy. As expected, subjects experienced not only empathic feeling, but also empathic anger and empathic joy. Subjects in Testing 1 felt more empathic than did those in Testing 2 (

t = 2.514, p = 0.006, 95% CI [5.823,5.984]), and subjects in Testing 2 experienced the feelings of empathic anger (

t = -3.123,

p = 0.001, 95% CI [2.937,3.376]) and empathic joy (

t = -5.184,

p = 0.000, 95% CI [3.821,4.369]) in addition to empathy (

SI Table S3).

According to the Schwartz values theory, as cited by Bouman et al. (2018), this study used items from the Environmental Portrait Value Questionnaire (E-PVQ) to gauge two types of values, egoism and hedonism, of respondents. These two constructs were measured via a self-report questionnaire in which respondents were asked to complete a 6-point Likert scale on an eight-item scale (1 = not like me at all to 6 = like me the most). A mean score was computed after the reliability and validity of each construct were measured. Higher scores indicate greater inclination toward egoistic or hedonistic values. A dummy variable for each construct was also developed.

Self-enhancement values, combined with egoism and hedonism, are personal values referring to making individuals focus on self-interest (Stern et al., 1998; de Groot & Steg, 2008b; Steg et al., 2014, as cited by Bouman et al., 2018). After analysis with Stata 17, principal component factor analysis (PCA) was performed, which revealed that merging egoism and hedonism into the self-enhancement dimension was less reliable. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) validated the result, as the factor loadings of hedonism ranged from 0.14 to 0.17, which was far less than 0.50. The construct was also less fit with the data since the chi-square test for degree of freedom was X

2 (15) = 28.513 with

p < 0.05 (> 0.05), the comparative fit index (CFI) was 0.965 (≥ 0.95), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was 0.062 (≤ 0.05) (

SI Tables S4 and S5). Therefore, we used only egoism as a construct to moderate the effects of sadness-inducing ads on the amount of donation.

We also employed the graded response model (GRM) of item response theory (IRT), which is an analytical tool for determining how reliable a construct is (Samejima, 1969). Using the Stata 17 package, we developed a graph to show how each item information function (IIF) of the construct differed (Alan C. Acock, 2018). The peak in the graph represents the location on which each item measuring personal values (i.e., egoistic values) provides the most information. The amount of information basically reflects the ability of an item to measure personal values (Bankert et al., 2017 as cited by Ros & Kaneko, 2022).

Figure 1 below clearly shows the supplement of the five items belonging to the construct, egoistic values. The supplement confirmed validity of the construct, as it covered a better range of concerns for self (i.e., -2 > θ < 2). Item 3: ‘

It is important to me to be influential’ provides the most information (

b = 2.78, p = 0.000, 95% CI [1.894,3.671]), followed by item 2: ‘

It is important to me to have authority over others’ (

b = 1.93,

p = 0.000, 95% CI [1.361,2.503]). For the other three items, item 4 ‘

It is important to me to have money and possessions’ (

b = 1.34,

p = 0.000, 95% CI [0.969, 1.713]; item 1 ‘

It is important to me to have control over others’ actions’ (

b = 1.19,

p = 0.000, 95% CI [0.840,1.544]; and item 5 ‘

It is important to me to work hard and be ambitious’ (

b = 1.18,

p = 0.000, 95% CI [0.815,1.541] provided less information.

The reliability of the information provided depends on the range and the value of θ (Theta), whether it is below or above zero.

Table 1 shows that the information provided in the egoistic values was in locations where the θ values were greater than zero (θ > 0). For instance, P1 = 0.827 and P2 = 0.798 indicated that 0.173 (17.3%) and 0.202 (20.2%) of the variance in the measure of egoistic values at the two locations was not reliable, but up to 82.7% and 79.8%, respectively, were reliable. A dummy variable of the construct was then developed. Subjects whose score was above the mean (M = 3.43, SD = 1.03) were assumed to be egoistic (e.g., 1 = high-egoistic values, 0 = otherwise).

4. Methods

To estimate the video’s effects on the amount of donation given, we employed an econometric analysis, the Tobit Regression

1. The intent was to test for a statistically significant difference between the two testing groups (Testing 1 vs. Testing 2) in terms of the amount donated. The Tobit Regression equation is as the following:

where

Amountij is the money of individual

i donated to charity

j which is between 0.00 USD and 2.50 USD.

Testingig is a binary indicator of individual

i in treatment group

g.

Valuesig is a personality trait of individual

i in treatment group

g.

θig is city-level fixed effects at which individual

i in group

g is living. As subjects in each group were randomly selected, the balance is assumed, whereby the variation of outcome is presumed to be caused by the video effects (

SI Table S6).

5. Results and Discussion

90.9% of subjects in Testing 1 decided to donate to humanitarian charity after watching the ad on human suffering-induced sadness. Analyzing with one-sample test of a proportion, we could reject the null hypothesis that proportion is 0.5 for subjects in Testing 1 (z = 9.78, p = 0.000, 95% CI [.861,.956]). However, this was not the case for subjects in Testing 2 where only 47.8% chose conservation charity to donate to after watching the ad on animal suffering-induced sadness (z = 0.458, p = 0.323, 95% CI [.431,.610]). It could be presumed the video appeals of Testing 2 were not as empathic as Testing 1. In short, in a context where beneficiaries have an empathic feeling, the weight of helping humans was likely heavier than helping animals.

Regarding the amount donated, the average of donation of Testing 1 (M = 1.43 USD, SD = 0.81) was almost equal to Testing 2 (M = 1.44 USD, SD = 0.81), so no significant difference in donation size between the two groups was statistically detected (

b = -0.013,

p = 0.925, 95% CI [-.285,.257]) (see., Model 1

Table 2). As the average donation of the two Testing groups was higher than the median (

μ = 1.25 USD), subjects within each group appeared to keep less for themselves but donated a little bit more to others. The observed variation of donating behavior might be explained by empathic feeling, such that neither aroused by human suffering-induced sadness nor animal suffering-induced sadness was significantly different.

To test whether empathic feeling affected the amount donated, we ran a t-test to compare the mean difference between Testing 1 and Testing 2 against the Control group. As expected, the amount donated by Testing 1 was 0.22 USD greater than that donated by the Control group (M = 1.42 USD – M = 1.20 USD), with a statistically significant difference at 5% level (t = 2.145, p = 0.016, 95% CI [0.018,0.429]), and the amount donated by Testing 2 was 0.24 USD greater than that donated by the Control (M = 1.44 USD – M = 1.20 USD), with a statistically significant difference at 5% level (t = 2.201, p = 0.014, 95% CI [0.024,0.448]). This result supported hypothesis 1 that subject’s pro-social act, the donating behavior, was unlikely to be different as the behaviors are similarly influenced by the intensity of the empathy aroused by each ad.

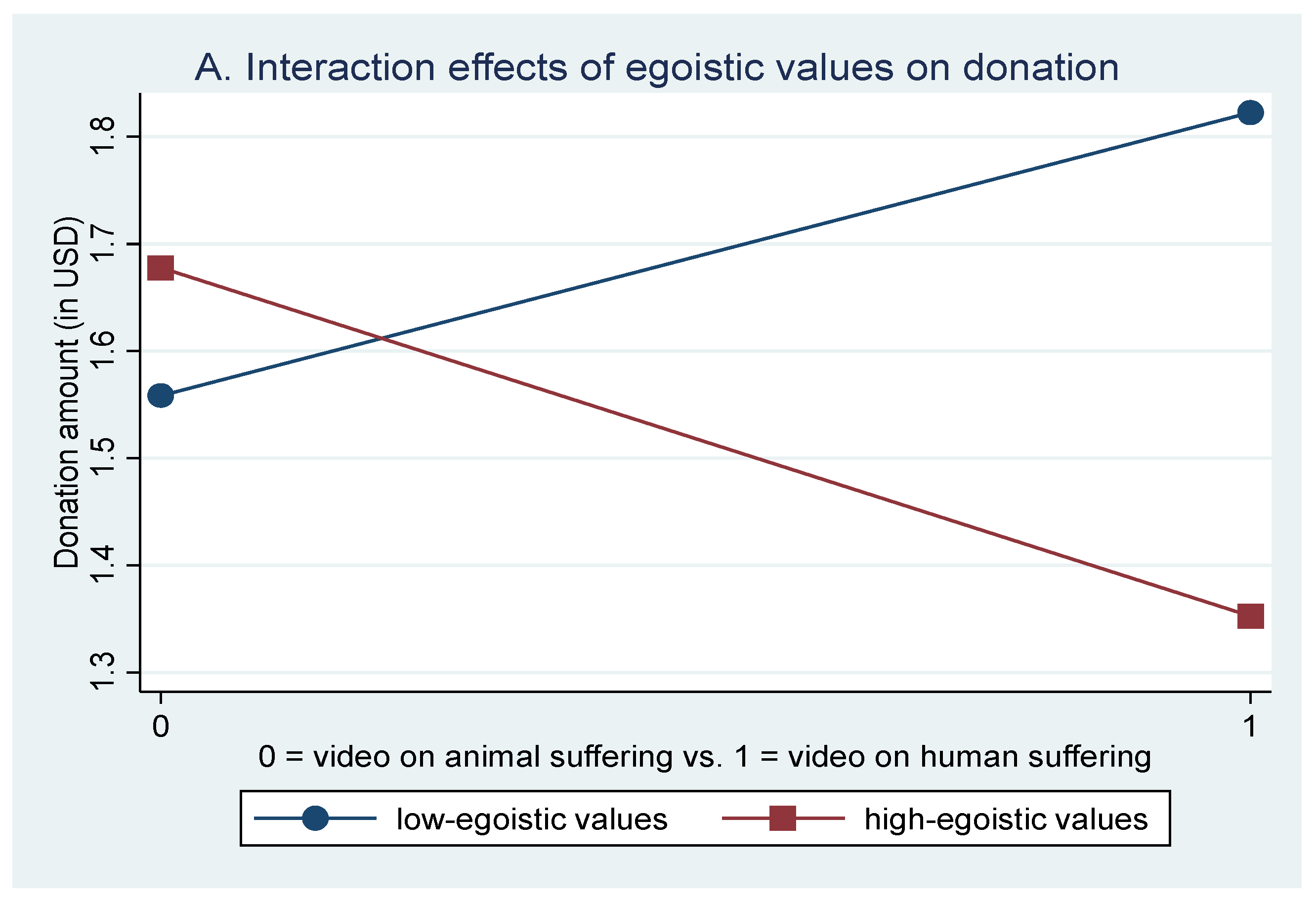

According to Model 2

Table 2, there were interaction effects between personal values and empathy, on the outcome variable (

b = -0.589,

p = 0.032, 95% CI [-1.127, -0.051]). The simple effects tests were employed to test if each slope was statistically significantly different (Michael, 2012; Rosenthal & Rosnow, 1985 as cited by Sagiv et al., 2011). Looking at negative slope, the average donation of subjects with high-egoistic values in Testing 1 and Testing 2 was M = 1.35 USD and M = 1.68 USD respectively (

Plot A, Figure 2). The moderating effect of high-egoistic values of Testing 1 against Testing 2 was m = -0.33 USD (1.35 USD - 1.68 USD). Although Testing 1 donated 0.33 USD less than Testing 2, the difference was statistically insignificant (

t = -1.64,

p = 0.102). This result appeared to illustrate that there are no moderating effects of high-egoistic values over empathy.

Figure 2.

The role of personal values in moderating the effects of empathy on amount of donation.

Figure 2.

The role of personal values in moderating the effects of empathy on amount of donation.

As previously claimed, the weight of helping humans was likely heavier than helping animals, though insignificant, why was the amount donated to human suffering less than that to animal suffering? Since subjects experienced also empathic anger (i.e., Vitaglione & Barnett, 2003; Hechler & Kessler, 2018; Keck, 2019) and empathic joy (Hoffman, 1981), it is presumed that variation in donation might, to a certain degree, be explained by the emotions, either empathic anger or empathic joy. To prove this, we once again ran a one-level Tobit Regression by adding empathic anger and empathic joy, the categorical variables, as additional moderators. Subjects whose score was one standard deviation (SD) above the mean (M = 3.20, SD = 1.77) were assumed to have high-empathic anger (e.g., 1 = high-empathic anger, 0 = otherwise). The Tobit Regression equation with categorical-by-categorical-by-categorical interactions (Mitchell, 2012) is as follows:

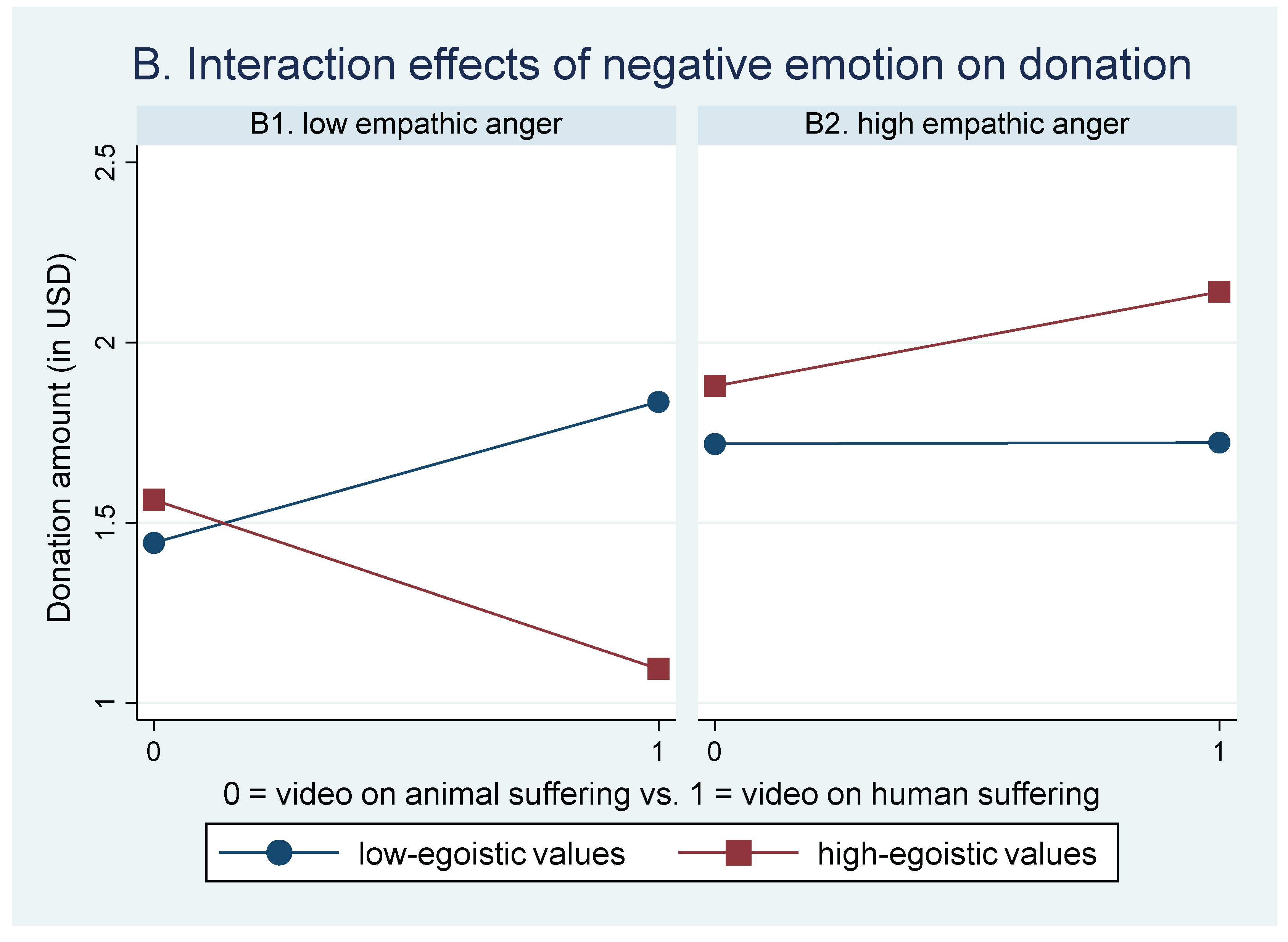

According to Model 3,

Table 2, there were interaction effects of empathic anger on the outcome variable with significant level at 10% (

b = 1.118,

p = 0.083, 95% CI [-.148,2.386]). The simple effects tests showed that with high-empathic anger, subjects with high-egoistic values in Testing 1 donated 0.26 USD (M=2.14 USD – M = 1.88 USD) more than those in Testing 2, but statistically insignificant (

t = 0.46

, p = 0.649). The result indicates the robustness of hypothesis 1 and seemed to prove that donating behavior, no matter under the moderating effects of either personal values or the combination between personal values and anger, is unlikely different as the behavior itself is similarly influenced by the intensity of the empathy aroused by each ad. As each amount donated was higher than the median (i.e., Testing 1: M = 2.14 USD & Testing 2: M =1.88 USD). Therefore, subjects with high-egoistic values could likely be persuaded to maintain the amount of donation if they are exposed to a video in which empathic anger in addition to empathy is produced (

Plot B2 Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The role of negative emotion in moderating the effects of empathy on amount of donation.

Figure 3.

The role of negative emotion in moderating the effects of empathy on amount of donation.

According to Model 4,

Table 2, empathic joy didn’t play the role as well as empathic anger (

b = 0.187,

p = 0.827, 95% CI [-1.503,1.878]). With high-empathic joy, the slope difference between subjects with high-egoistic values in Testing 1 and Testing 2 was statistically insignificant with m = 0.03 USD (M=1.49 USD – M = 1.46 USD). Nevertheless, high-empathic joy appeared to not decrease the amount donated to a charity too (i.e., Testing 1: M = 1.49 USD & Testing 2: M = 1.46 USD). Therefore, it was primarily assumed that high-empathic joy itself likely convinced subjects with high-egoistic values in each group to just not decrease their donation to a charity (

SI, Plot A2 Figure A).

The above-mentioned results implied that at the similar valence of empathic intensity, high-egoistic values did not explain the variation of donating behavior of the two testing groups, even upon being interacted with high-empathic anger or high-empathic joy. This was a good sign for both NPOs working in conservation as well as in humanitarian aid. However, for NPOs in humanitarian aid, high-empathic anger is more helpful, increasing significantly the amount donated by subjects, especially among those with high-egoistic values. Comparing the high-empathic anger versus low-empathic anger, the difference of amount donated among those subjects with high-egoistic values in Testing 1 was m = 1.05 USD (M = 2.14 USD – M = 1.09 USD) and statistically significant at 1% level (t = 2.92, p = 0.004).

For NPOs in environmental conservation, the difference of amount donated among those subjects with high-egoistic values in Testing 2 was m = 0.32 USD (M = 1.88 USD – M = 1.56 USD) and statistically insignificant (t = 0.93, p = 0.353). So, high-empathic anger in Testing 2 seemed not to be as necessary as in Testing 1. The amount donated by subjects watching animal-suffering induced sadness neither decreased nor significantly increased, regardless of the donors’ personal values and high-empathic anger. So, it was believed that subjects with high-egoistic values likely keep less for themselves but give more to others if they are exposed to an ad upon which they are aroused by empathic anger in addition to empathy, particularly for an ad on human suffering.

To prove the robustness of the claim, we hypothesized that high-egoistic values did not or negatively correlate with empathy and without being interacted with high-empathic anger, the donation amount of subjects with high-egoistic values in Testing 1 against Control was not statistically significant too. As hypothesized, the result of the pairwise correlation indicated that high-egoistic values indeed did not have correlation with empathy aroused by human suffering (Testing 1;

r(143) = -.017,

p = .836) (

SI Table S7), while the simple effects test also supported the hypothesis as the slope of subjects with high-egoistic values in Testing 1 against Control was m = 0.09 USD (

t = 0.56,

p = 0.579), and statistically insignificant (

SI Plot B1, Figure B). However, it turned to statistical significance at 1% level (m = 1.12 USD;

t = 3.41,

p = 0.001) upon being interacted with high-empathic anger (

SI Plot C2, Figure C), but not with high-empathic joy (m = 0.29 USD;

t = 0.98,

p = 0.329) (

SI Plot C4, Figure C).

As the amount donated by subjects with high-egoistic values in Testing 2 kept increasing (i.e., between M = 1.68 USD & M = 1.88 USD), it was believed that it was likely the role of aversive feeling aroused by the innocent animal suffering. It’s commonly believed that animals or wildlife are innocent, so a high valence of empathic anger would be aroused to a higher extent by being immersed with any harms on the innocent animal which are attributed to a particular transgression. The aversive feeling could also result from the innocent animal as an elephant which, has been specifically identified as an animal species that exhibits empathy eliciting characteristics (Young et al., 2018).

Was it true that the innocent animal suffering aroused those subjects with high-egoistic values, resulting in keeping less, but giving more to others? If this was true, we hypothesized that high-egoistic values would have positive correlation with the empathy aroused by animals suffering. In addition, we also hypothesized that subjects with high-egoistic values in Testing 2 donated more than those subjects in Control, and much more upon being interacted with high-empathic anger, but not with high-empathic joy.

The results of the pairwise correlation indicated that high-egoistic values indeed had positive correlation with empathy aroused by animal suffering (Testing 2;

r(119) = .158,

p = .084) (

SI Table S7). Based on results from simple effects test, subjects with high-egoistic values in Testing 2 always donated more than Control. Upon being interacted with high-egoistic values, the donation amount was 0.43 USD (

t = 2.20,

p = 0.029) more than Control (

SI Plot B2, Figure B) and it increased statistically significantly to m = 0.97 USD (

t = 3.26,

p = 0.001) upon being interacted with high-empathic anger (

SI Plot D2 Figure D). Nevertheless, it turned to statistical insignificance (m= 0.44 USD;

t = 1.41,

p = 0.160) upon being interacted with high-empathic joy (

SI Plot D4 Figure D). The insignificance of the interaction effects of high-empathic joy on donation amount appears to imply that videos produced to mobilize funds from individuals should show mainly empathy and empathic anger of a victim either aroused by human suffering or animal suffering. The signs of relief or joy of the victim after getting helped appeared to be optional.

6. Conclusions

This study set out to understand whether there is a difference in donating behavior between individuals exposed to human suffering and to animal suffering. It further seeks to examine how emotions and personal values, egoism, shape these behavioral responses. Our analysis suggests that donations to humans in need seemed more valuable than to animals in need. Though they were aroused by being exposed to sadness, around 50% of those viewing the animal suffering-induced sadness chose to donate to the humanitarian charity. As human beings, helping humans in need makes more sense, especially in a situation where they were required to choose between humans and animals.

No statistically significant difference was detected between the effect of animal suffering-induced sadness and human suffering-induced sadness on the amount of donation. We observed the roles of personal values, egoism, in moderating the effects of empathy on donation. Egoistic values appeared to negatively explain the variation of donating behavior. However, with the present of negative feeling, empathic anger, the egoistic values became less significant. So, to attract funding from individuals regardless of their personal values NPOs could design marketing ads in which audiences are stimulated not only by compassion, but also empathic anger. This means that a convincing video should move from sadness to empathic anger which is attributed to a particular transgressor and finally and, optionally, to empathic happiness at the end. Remarkably, this finding was prominent and could be used by NPOs as guidance in its marketing strategy to raise financial support from young (what age group/range?) individual donors.

The study also found that who was the actor in the ads – human or nonhuman – had a significant role. We found that videos in which empathic feeling aroused by animals impressed egoistic audients’ decision to donate to a charity more than humans as actors. This finding is likely true among those with high-egoistic values who appeared to believe that hardship was just a normal way of living as human beings and happens to everyone. They likely believe that humans should work hard to have money, authority and influence over others rather than show their weaknesses to others to get their mercy or empathy. However, this thought does not seem to apply to empathy aroused by innocent animals as actors. A video on animals in need attracted audiences including those with high-egoistic values to not keep money for themselves, but to give to others instead.

7. Limitations and Future Directions

One of the main limitations of our study was that the videos for experiment were not pretested beforehand, so subjects were unexpectedly aroused not only by compassion, but also the extraneous ones, including empathic anger and empathic joy. The second limitation was about the endowment. Though it was real money, it was still money given but not their own money. In the future, such research should be replicated with subjects in general and look at the difference in donating behavior between human suffering and the suffering of other animals, especially the ones whose characteristics elicit empathy such as canines, primates, etc. (Young et al., 2018).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

| 1 |

Since 25.4% of observations donated 2.5 USD at the upper limit, Tobit Regression is more likely an appropriate tool to do analysis with Limited Dependent Variable (LDV). |

References

- Alan C. Acock. (2018). A Gentle Introduction to Stata.

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Moore, D. J. (1994). Public Service Advertisements: Emotions and Empathy Guide. Journal of Marketing, 58(1), 56–70. [CrossRef]

- Bakir-Demir, T., Berument, S. K., & Akkaya, S. (2021). Nature connectedness boosts the bright side of emotion regulation, which in turn reduces stress. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 76. [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S., & Wheelwright, S. (2004). The Empathy Quotient: An Investigation of Adults with Asperger Syndrome or High Functioning Autism, and Normal Sex Differences. In Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (Vol. 34, Issue 2).

- Batson, C. D. (1987). Prosocial Motivation: Is it ever Truly Altruistic? Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 20(C), 65–122. [CrossRef]

- Batson, C. D. (2014). The Altruism Question: Toward A Social-psychological Answer. In The Altruism Question. Psychology Press. [CrossRef]

- Batson, C. D., & Ahmad, N. (2001). Empathy-induced altruism in a prisoner’s dilemma II: what if the target of empathy has defected? European Journal of Social Psychology Eur. J. Soc. Psychol, 31, 25–36.

- Batson, C. D., Batson, J. G., Slingsby, J. K., Harrell, K. L., Peekna, H. M., & Todd, R. M. (1991). Empathic Joy and the Empathy-Altruism Hypothesis. In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (Vol. 61, Issue 3).

- Batson, C. D., Duncan, B. D., Ackerman, P., Buckley, T., & Birch, K. (1981). Is Empathic Emotion a Source of Altruistic Motivation? In journal of Personality and Social Psychology (Vol. 40, Issue 2).

- Batson, C. D., O’quin, K., Fultz, J., Vanderplas, M., & Isen, A. M. (1983). Influence of Self-Reported Distress and Empathy on Egoistic Versus Altruistic Motivation to Help. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(3), 706–718. [CrossRef]

- Batson, C. D., Polycarpou, M. R., Harmon-Jones, E., Imhoff, H. J., Mitchener, E. C., Bednar, L. L., Klein, T. R., & Highberger, L. (1997). Empathy and Attitudes: Can Feeling for a Member of a Stigmatized Group Improve Feelings Toward the Group? In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (Vol. 72, Issue 1).

- Batson, C. D., Sager, K., Garst, E., Kang, M., Rubchinsky, K., & Dawson, K. (1997). Is Empathy-Induced Helping Due to Self-Other Merging? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(3), 495–509. [CrossRef]

- Bouman, T., Steg, L., & Kiers, H. A. L. (2018). Measuring values in environmental research: A test of an environmental Portrait Value Questionnaire. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(APR). [CrossRef]

- Castelo, N., White, K., & Goode, M. R. (2021). Nature promotes self-transcendence and prosocial behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 76. [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R., Arps, K., Batson, C. D., Batson, J. G., Griffitt, C. A., Barrientos, S., Brandt, J. R., Sprengelmeyer, P., & Bayly, M. J. (1989). Negative-State Relief and the Empathy-Altruism Hypothesis. In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (Vol. 56, Issue 6).

- Cialdini, R. B., & Goldstein, N. J. (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 591–621. [CrossRef]

- Dannenberg, A., & Martinsson, P. (2021). Responsibility and prosocial behavior - Experimental evidence on charitable donations by individuals and group representatives. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 90. [CrossRef]

- Davis, M. H. (1980). A Multidimensional Approach to Individual Differences in Empathy. JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology, 10, 85.

- Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy. Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 113–126. [CrossRef]

- de Groot, J. I. M., & Steg, L. (2008). Value orientations to explain beliefs related to environmental significant behavior: How to measure egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric value orientations. Environment and Behavior, 40(3), 330–354. [CrossRef]

- Dickert, S., Sagara, N., & Slovic, P. (2011). Affective motivations to help others: A two-stage model of donation decisions. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 24(4), 361–376. [CrossRef]

- Everett, J. A. C., Caviola, L., Kahane, G., Savulescu, J., & Faber, N. S. (2015). Doing good by doing nothing? The role of social norms in explaining default effects in altruistic contexts. European Journal of Social Psychology, 45(2), 230–241. [CrossRef]

- FeldmanHall, O., Dalgleish, T., Evans, D., & Mobbs, D. (2015). Empathic concern drives costly altruism. NeuroImage, 105, 347–356. [CrossRef]

- Geier, M. T. (2021). Students’ Expectations and Students’ Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Excellent Teacher Behaviors. Teaching of Psychology, 48(1), 9–17. [CrossRef]

- Hechler, S., & Kessler, T. (2018). On the difference between moral outrage and empathic anger: Anger about wrongful deeds or harmful consequences. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76, 270–282. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, M. L. (1981). Is Altruism Part of Human Nature? Personality and Social Psychology, 40(1), 121–137.

- Jaeger, B., & van Vugt, M. (2022). Psychological barriers to effective altruism: An evolutionary perspective. Current Opinion in Psychology, 44, 130–134. [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, D., & Farrington, D. P. (2006). Development and validation of the Basic Empathy Scale. Journal of Adolescence, 29(4), 589–611. [CrossRef]

- Kamas, L., & Preston, A. (2021). Empathy, gender, and prosocial behavior. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 92. [CrossRef]

- Keck, S. (2019). Gender, leadership, and the display of empathic anger. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92(4), 953–977. [CrossRef]

- Keeley, J., Smith, D., & Buskist, W. (2006). The Teacher Behaviors Checklist: Factor Analysis of Its Utility for Evaluating Teaching. Teaching of Psychology, 33(2), 84–91. [CrossRef]

- Kim, N. (2014). Advertising strategies for charities: Promoting consumers’ donation of time versus money. International Journal of Advertising, 33(4), 707–724. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. J., & Kou, X. (2014). Not All Empathy Is Equal: How Dispositional Empathy Affects Charitable Giving. Journal of Nonprofit and Public Sector Marketing, 26(4), 312–334. [CrossRef]

- Komarraju, M. (2013). Ideal Teacher Behaviors: Student Motivation and Self-Efficacy Predict Preferences. In Teaching of Psychology (Vol. 40, Issue 2, pp. 104–110). [CrossRef]

- Konrath, S. H., O’Brien, E. H., & Hsing, C. (2011). Changes in dispositional empathy in American college students over time: A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(2), 180–198. [CrossRef]

- Krupka, E., & Weber, R. A. (2009). The focusing and informational effects of norms on pro-social behavior. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(3), 307–320. [CrossRef]

- Maio, G. R. (2011, August). Don’t Mind the Gap Between Values and Action. https://commoncausefoundation.org/_resources/dont-mind-the-gap-between-values-and-action/.

- Maio, G. R., & Olson, J. M. (1995). Relations between Values, Attitudes, and Behavioral Intentions: The Moderating Role of Attitude Function. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 31(3), 266–285. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F. S., & Frantz, C. M. P. (2004). The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24(4), 503–515. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C. J., & Tripodi, E. (2021). Image concerns in pledges to give blood: Evidence from a field experiment. Journal of Economic Psychology, 87. [CrossRef]

- Michael, M. N. (2012). Interpreting and Visualizing Regression Models Using Stata (First edition, Vol. 558). College Station, TX: Stata Press.

- Milaniak, I., Wilczek-Rużyczka, E., & Przybyłowski, P. (2018). Role of Empathy and Altruism in Organ Donation Decisionmaking Among Nursing and Paramedic Students. Transplantation Proceedings, 50(7), 1928–1932. [CrossRef]

- Neaman, A., Otto, S., & Vinokur, E. (2018). Toward an integrated approach to environmental and prosocial education. Sustainability (Switzerland), 10(3). [CrossRef]

- Pfattheicher, S., Sassenrath, C., & Schindler, S. (2015). Feelings for the Suffering of Others and the Environment: Compassion Fosters Proenvironmental Tendencies. Environment and Behavior, 48(7), 929–945. [CrossRef]

- Piff, P. K., Dietze, P., Feinberg, M., Stancato, D. M., & Keltner, D. (2015). Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(6), 883–899. [CrossRef]

- Roccas, S., & Sagiv, L. (2010). Personal Values and Behavior: Taking the Cultural Context into Account. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(1), 30–41. [CrossRef]

- Ros, B., & Kaneko, S. (2022). Is Self-Transcendence Philanthropic? Graded Response Model Approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, R., & Rosnow, R. L. (1985). Contrast analysis: Focused comparisons in the analysis of variance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sagiv, L., Sverdlik, N., & Schwarz, N. (2011). To compete or to cooperate? Values’ impact on perception and action in social dilemma games. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41(1), 64–77. [CrossRef]

- Samejima, F. (1969). Estimation of latent ability using a response pattern of graded scores. Psychometrika Monograph Supplement, 34(4, Pt. 2), 100. www.comped-cam.org.

- Schroeder, D. A., Dovidio, J. F., Sibicky, M. E., Matthews, L. L., & Allen, J. L. (1988). Empathic concern and helping behavior: Egoism or altruism? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 24(4), 333–353. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 1–65. [CrossRef]

- Sneddon, J. N., Evers, U., & Lee, J. A. (2020). Personal Values and Choice of Charitable Cause: An Exploration of Donors’ Giving Behavior. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 49(4), 803–826. [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C. R., & Lopez, S. J. (2002). Handbook of Positive Psychology (C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopex, Eds.). Oxford University Press, Inc.

- Steg, L., Perlaviciute, G., van der Werff, E., & Lurvink, J. (2014). The Significance of Hedonic Values for Environmentally Relevant Attitudes, Preferences, and Actions. Environment and Behavior, 46(2), 163–192. [CrossRef]

- Stern, P. C., Dietz, T., Abel, T., Guagnano, G. A., & Kalof, L. (1999). A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Human Ecology Review, 6(2), 81–97.

- Stern, P. C., Dietz, Thomas., & Guagnano Gregory A. (1998). A Brief Inventory of Values. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 58(6), 984–1001. [CrossRef]

- Tam, K. P. (2013). Dispositional empathy with nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 35, 92–104. [CrossRef]

- Toi, M., & Daniel Batson, C. (1982). More Evidence That Empathy Is a Source of Altruistic Motivation. In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (Vol. 43, Issue 2).

- Vitaglione, G. D., & Barnett, M. A. (2003). Assessing a New Dimension of Empathy: Empathic Anger as a Predictor of Helping and Punishing Desires 1. Motivation and Emotion, 27(4). [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N., Przybylski, A. K., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Can nature make us more caring? Effects of immersion in nature on intrinsic aspirations and generosity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(10), 1315–1329. [CrossRef]

- Wesley Schultz, P. (2000). Empathizing With Nature: The Effects of Perspective Taking on Concern for Environmental Issues. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 391–406.

- White, K., & Peloza, J. (2009). Self-Benefit Versus Other-Benefit Marketing Appeals: Their Effectiveness in Generating Charitable Support. Journal of Marketing, 73, 109–124.

- Wymer, W., & Gross, H. (2023). Charity advertising: A literature review and research agenda. Journal of Philanthropy and Marketing, 28(4). [CrossRef]

- Xie, C., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2014). The Role of Moral Emotions and Consumer Values and Traits in the Decision to Support Nonprofits. Journal of Nonprofit and Public Sector Marketing, 26(4), 290–311. [CrossRef]

- Young, A., Khalil, K. A., & Wharton, J. (2018). Empathy for Animals: A Review of the Existing Literature. In Curator (Vol. 61, Issue 2, pp. 327–343). Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. W., Piff, P. K., Iyer, R., Koleva, S., & Keltner, D. (2014). An occasion for unselfing: Beautiful nature leads to prosociality. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 37, 61–72. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).