Submitted:

25 September 2024

Posted:

26 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Biobutanol as an Advanced Fuel Option

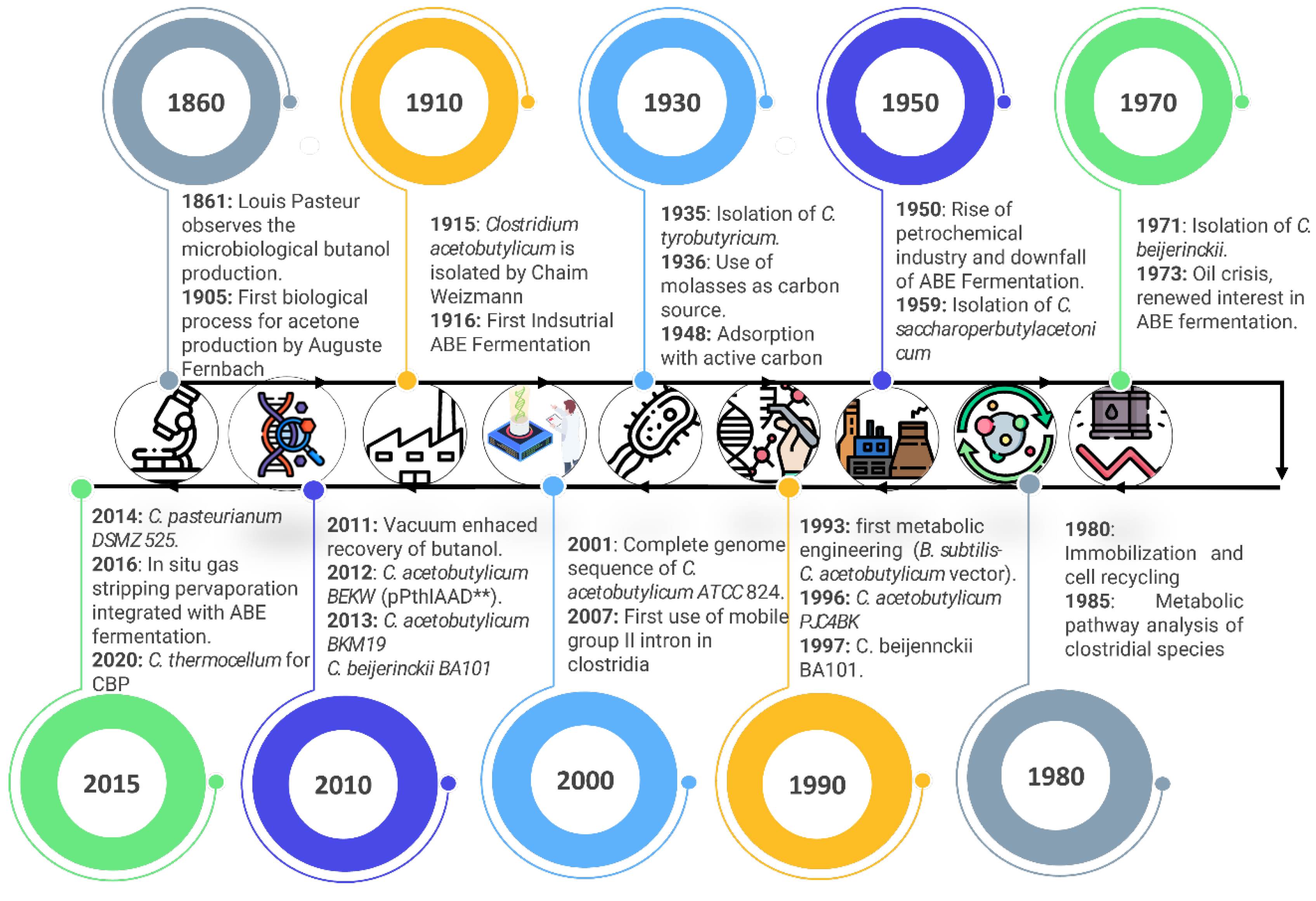

3. Brief History of Biobutanol Production

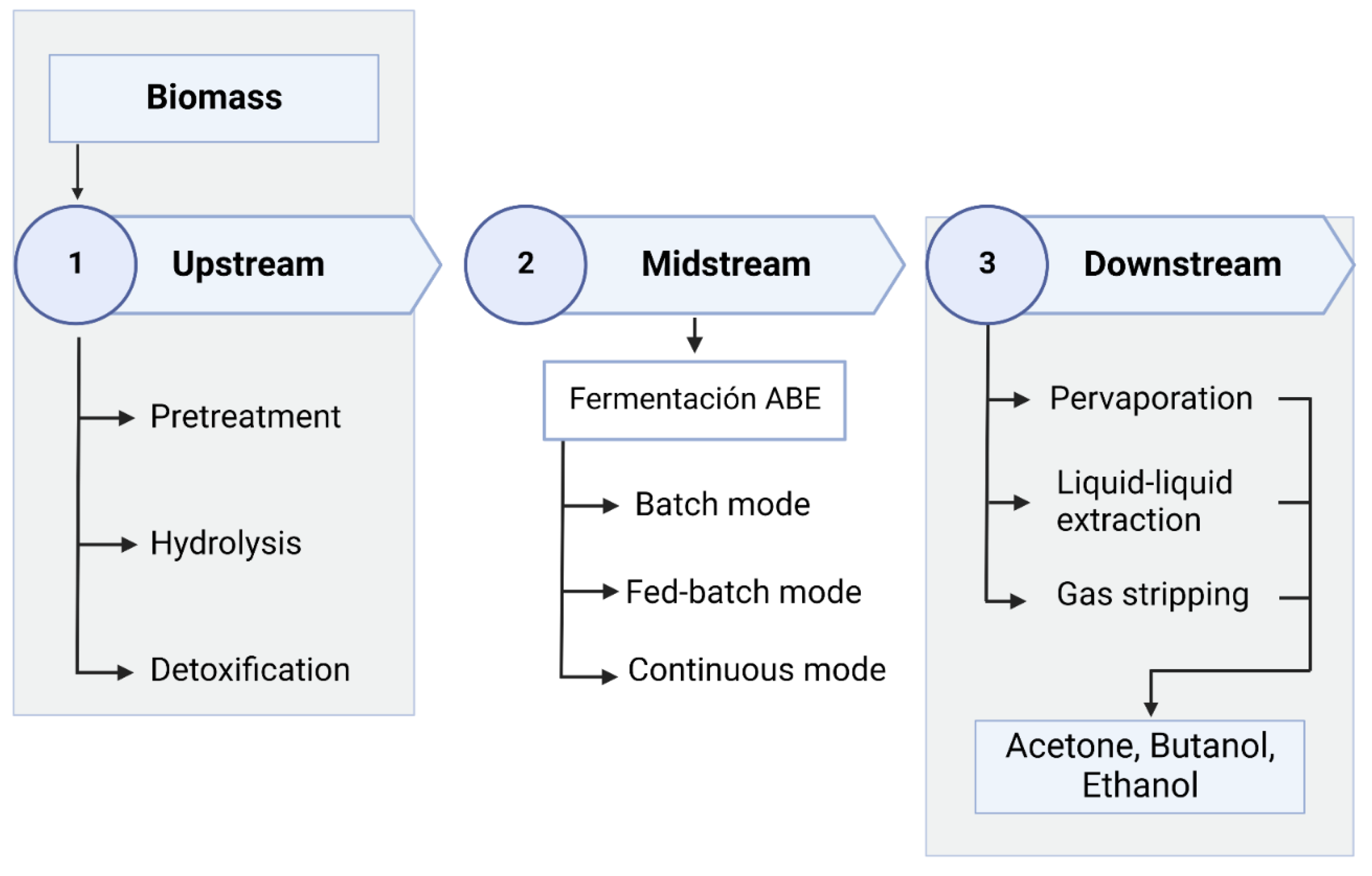

4. Overall Biobutanol Production Process

| Drawbacks of ABE Fermentation | Strategies to improve biobutanol production |

| High Feedstock costs due to competence with alimentary industry |

|

| Product inhibition due to butanol toxicity to strains |

|

| Low butanol titer concentration, and, thus, low yield and productivity |

|

| High cost for downstream processes. |

|

4.1. Feedstock Selection for Biobutanol Production

Biobutanol Production from Lignocellulosic Biomass

4.2. Upstream

| Pretreatment | Hydrolysis | Feedstock and strain | Detoxification process | Novelty | Major Findings | Reference |

| Dilute sulfuric acid | - | Bamboo C.acetobutylicum YM1 |

Overliming adsorption bacterial | Multiple detoxification processes were considered: i) Overliming, ii) adsorption with activated charcoal, iii) bacterial adaptation, and iii) vacuum evaporation. | Overliming did not significantly altered the concentration of inhibitor, since aliphatic acids remained the same, and HMF, was reduced just 20%. Also, the concentration of reducing sugars was 10% less. On the other hand, char coal process was able to reduce 98% and 50% HMF and furfural respectively. Despite that, same result with reducing sugars were obtained comparing to Overliming. |

[95] |

| crushing and sieving | Acid hydrolysis | Corncob Clostridium sp. strain LJ4 |

Electrochemical detoxification | Electrochemical detoxification for the removal of phenolic inhibitors. Use of a novel solventogenic strain isolated by the authors, Clostridium sp. strain LJ4. |

Electrochemical detoxification could eliminate inhibitors without causing sugar loss. The employed strain exhibited resistance to high concentrations of HMF and furfural, resulting in a 60% increase in the final butanol titer. |

[98] |

| Alkaline NaOH pretreatment | Enzymatic hydrolysis with Cellic CTec 2 (Novozyme) | Lettuce residues Clostridium acetobutylicum DSMZ 792 | - | Use of residues from the packaging process of lettuce (Lactuca sativa) as a feedstock for biobutanol production. | I was possible to obtain a 19.5 gL-1 sugar concentration in the hydrolysate. The pre-treatment’s optimal NaOH concentration was 80 gL-1. |

[99] |

| Hydrothermal | Enzymatic Hydrolysis (Cellulase and hemicellulase) | Orange WasteC. acetobutylicum NRRL B-591 | Overliming | A Novel refinery was proposed for sustainable valorization of orange waste for biobutanol, H2 and biogas production. | The efficient conversion of untreated orange waste into biofuels was found to be challenging. Hydrothermal pretreatment was identified as a critical step in facilitating ABE fermentation. Through the process of overliming, successful fermentation of the substrate was achieved. The proposed biorefinery yielded significant results, producing 42.3 g of biobutanol, 33.1 g of acetone, 13.4 g of ethanol, 104.5 L of biohydrogen, and 28.3 L of biomethane per kg of orange waste, which contained an energy content of 4560 kJ. |

[90] |

| Microwave assisted dilute sulfuric acid pretreatment | Enzymatic Hydrolysis (cellulolytic complex) | Spent coffee groundsC. beijerinckii DSM 6422 | - | The valorization of cellulosic and hemicellulosic sugars derived from spent coffee grounds, followed by their subsequent utilization in ABE fermentation, has been explored. |

The integration of microwave and dilute sulfuric acid proved to be suitable for recovering both cellulosic and hemicellulosic sugars.A extraction of 79% and 98% of hemicellulosic and cellulosic sugar, respectively, was achieved after enzymatic hydrolysis. | [115] |

| Liquid hot water extraction | Enzymatic Hydrolysis (Cellulase) | Cassia fistula pods C. acetobutylicum TISTR 2375 | - | The utilization of roadside ornamental tree waste, specifically Cassia fistula pods, for solvent production. | Liquid hot water demonstrated to be a good method for extracting sugars from the pods residue. The final butanol yield was low (0,0006g butanol/ g pods). | [116] |

| Organosolv | Enzymatic Hydrolysis (Cellulase and hemicellulase) | Municipal solid wasteC. acetobutylicum | Organosolv (Simultaneous organosolv pretreatment and detoxification) | The valorization of the organic fraction of municipal solid waste (OFMSW) from a compost plant and the use of an ethanol organosolv process for both detoxification and pretreatment | Biological activity of the strain was inhibited by tannins.Using organosolv process, it was possible to remove tannins, and obtain a 70% starch recovery, which led to a yield of 150 g ABE /kg municipal solid waste. | [117] |

| Acid-catalyzed steam explosion | Enzymatic hydrolysis(Cellulose) | Phenolic-rich willow biomassC. acetobutylicum NRRL B-527 | Activated carbon detoxification | First time that a strategy of prior removal of phenolic extractives by water extraction (debarking) from willow is proposed, showing positive results, not only for enzymatic hydrolysis but for ABE fermentation as well. | The final acetone-butanol-ethanol (ABE) titer concentration obtained for the detoxified willow wood was 12 gL-1, which is considered relatively high compared to the literature reports for this type of biomass. The prior removal of phenolic extractives through debarking or hot water extraction proved to be a beneficial method for preventing the formation of phenol-aldehyde precipitates during steam explosion. This, in turn, resulted in improved enzymatic hydrolysis and ABE fermentation yields. |

[118] |

| Liquid hot water | Enzymatic hydrolysis(Cellulose) | Sugarcane strawC. acetobutylicum NRRL B-527 | Activated charcoal treatment | Search of the optimal condition of biomass load for hydrothermal pretreatment of sugarcane straw, in order of not requiring any detoxification step before fermentation. | Detoxification step was not necessary when 10 % solids were used for fermentation.A concentration of 13 gL-1 of ABE was obtained using 10% of biomass loading.Simultaneous saccharification and fermentation enhanced ABE productivity, compared to separated hydrolysis and fermentation. | [119] |

| Ammonium sulfite pretreatment | Enzymatic hydrolysis(Cellulose and Xylanase) - It was developed separate and simultaneous with Fermentation | Wheat strawClostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824 | - | There are few studies of ABE fermentation using ammonium sulfite pretreated biomass. This study also aimed to assess the potential of integrating enzymatic hydrolysis (saccharification) and fermentation into a single step. |

The utilization of ammonium sulfite pretreatment proved to be effective in enhancing the digestibility of wheat straw. Simultaneous saccharification and fermentation had a better performance (approximately 14% higher) compared to separated hydrolysis and fermentation. |

[120] |

| Hydrothermal microwave-assisted extraction | Enzymatic Hydrolysis (Cellulolytic complex) | Sugar beet pulpClostridium beijerinckii DSM 6422 | - | The pretreatment accomplished to extract pectooligosaccharides from the selected biomass. Since Hydrothermal pretreatment don’t use acids or alkaline solvents, this is and promising and environmentally friendly alternative to valorize sugar beet pulp. | Under the optimal conditions, hydrothermal microwave-assisted pretreatment was able to recover almost 60% of the pectooligosaccharides from the selected biomass. A yield of 53 kg of butanol per ton of sugar beet pulp was achieved in this study. | [121] |

| Sun-dried at greenhouse. | Enzymatic Hydrolysis (Cellulose and Lysases) | Saccharina latissima (macroalgae)Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824 | Hydrophobic adsorption resin | This study addresses the complete valorization of S. latissima from cultivation to biobutanol production. | Enzymatic hydrolysis led to a recovery of 80% of glucose from the biomass.The hydrolysis process was successfully scaled up to a volume of 100 L in this study. The detoxification step implemented in the fermentation process had a notable influence on the lag time, ultimately leading to a yield of 0.23 ABE g/g sugar. |

[122] |

| Microwave assisted dilute sulfuric acid pretreatment | Enzymatic Hydrolysis | Brewers Spent GrainC. beijerinckii DSM 6422 | Activated charcoal. Ion-exchange resins |

A novel approach was employed to valorize all the sugars, including both cellulosic and hemicellulosic, from brewers spent grain. | The optimal conditions for pretreatment were 147 °C, 2 minutes, and 1,26% (w/v) H2SO4. After hydrolysis and detoxification, the slurry sugar concentration achieved 73,9 gL-1 for a biomass loading of 15%. The study achieved a titer concentration of 11 gL-1, accompanied by a yield of 91 kg of butanol and 139 kg of ABE per ton of brewers spent grain. |

[123] |

| Ultrasound-assisted dilute acid hydrolysis | Dilute acid hydrolysis | Puerariae slag Clostridium beijerinckii YBS3 |

- | Diluted acid hydrolysis in combination with ultrasound has not wide research. | The pretreatment-hydrolysis method proposed in this study obtained a high concentration of reducing sugars, specifically 85,79 gL-1. In the absence of detoxification, the study achieved a final titer butanol concentration of 8.79 gL-1. Furthermore, this research reported a yield of 0.19 g butanol/g hydrolysate |

[124] |

| Freeze drying through sublimation | Acid hydrolysis | Wastewater microalgae Clostridium saccharoperbutylacetonicum N1-4 |

- | The optimization of acid hydrolysis as a saccharification method for wastewater microalgae feedstock, followed by valorization through ABE fermentation, remains an area with limited research. | The study determined that the optimal conditions for acid hydrolysis of the algae biomass were as follows: a concentration of 1.0 M H2SO4, a reaction time of 120 minutes, and a temperature range of 80-90°C. These parameters were found to be most effective in breaking down the complex carbohydrates present in the algae biomass and releasing fermentable sugars. Under these optimal conditions, a yield of 166.1 g sugar per kg of dry algae biomass was achieved. Additionally, a titer concentration of 3.74 gL-1 of butanol was obtained. The economic analysis led to rate of USD $ 12,54 per dry algae. |

[125] |

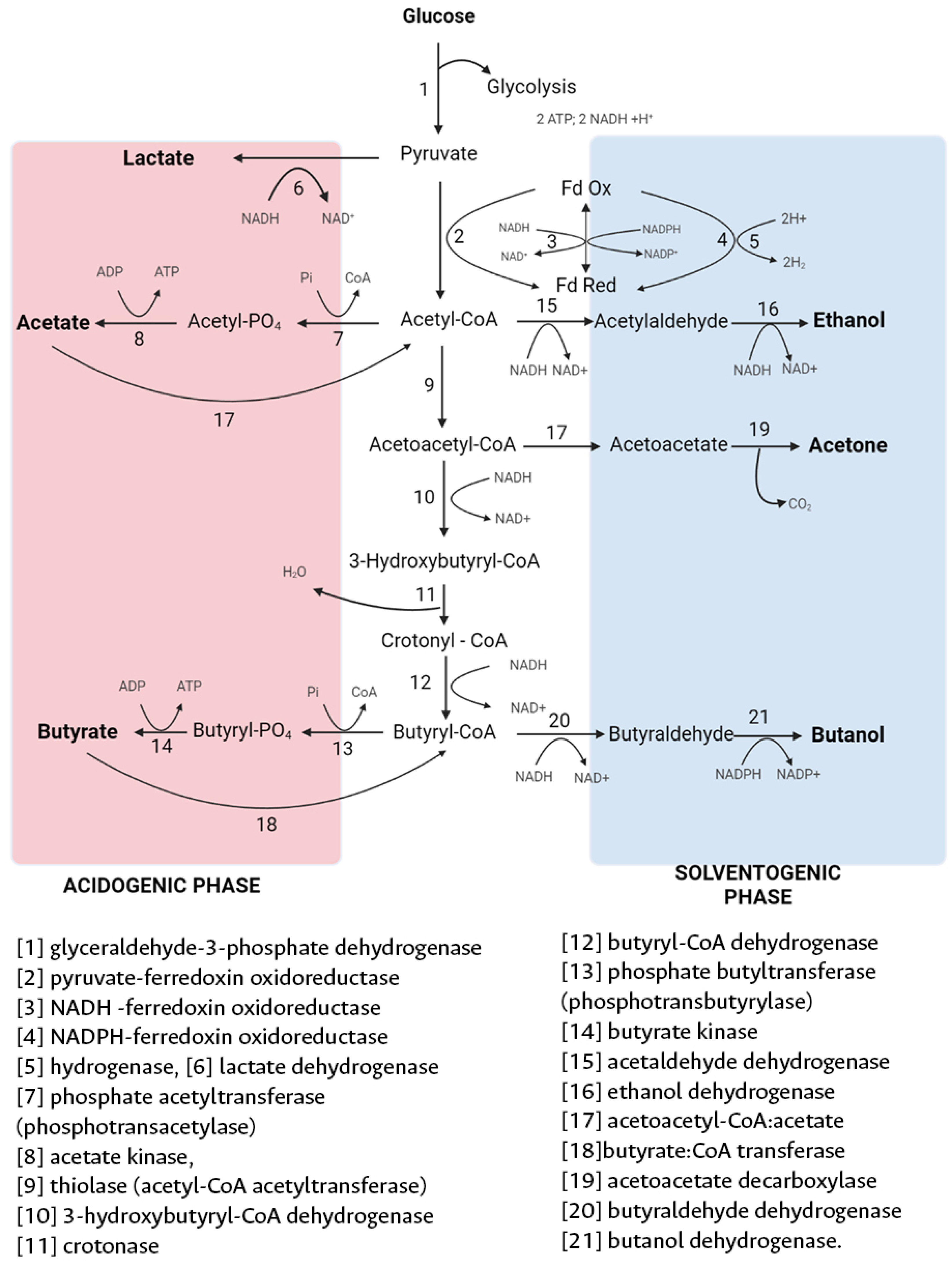

4.3. Midstream—ABE Fermentation

| Operation mode | Substrate | Strain | Culture type | Process Integration | Pretreatment and Detoxification | Solvents Concentration (gL-1) | Novelty |

Butanol yield (gg-1) |

Solvent yield (gg-1) |

Butanol productivity (gL-1h-1) |

Solvent productivity (gL-1h-1) |

Reference | |

| Butanol | Solvents | ||||||||||||

| Batch | wheat straw | Clostridium acetobutylicum CH02 | Suspension | SHF | Hydrotropic pretreatment with xylene sulfonate. Enzymatic hydrolysis with cellulase. | - | 12,41b | Evaluation of a hydrotropic pretreatment using sodium xylene sulfonate on wheat straw. | - | 0,10b | - | - | [81] |

| Batch | rice straw |

Clostridium beijerinckii F-6 and S. cerevisiae |

Co-culture Suspended |

SHF | Thermo-alkaline Dilute acid NaOH/Urea |

4,22 | 5,40b | The utilization of a co-culture system consisting of C. beijerinckii and S. cerevisiae presents a promising alternative approach to enhance butanol production. | 0,13 | 0,18b | 0,152 | - | [84] |

| Batch | Tea waste | C. beijerinckii DSMZ | Suspended | SHF | Diluted acid | 6,21 | 9,73b | The utilization of industrial tea waste as a feedstock and evaluates various factors that impact butanol production. Specifically, they investigate the effects of sugar loading, fermentation time, and nutrient concentrations in the production medium | 0,258 | - | 0,065 | 0,101b | [137] |

| Batch | Bamboo |

Clostridium beijerinckii ATCC 55025-E604 |

Suspended | SHF | Enzymatic hydrolysis with laccase and cellulases | 6,45 | - | Simultaneous pretreatment and saccharification of bamboo. | 0,095 | - | 0,089 | - | [94] |

| Batch | Glucose | Clostridium beijerinckii DSM 6423 | Immobilized | DFiR | N. A | 27,2 a c | 45,4 a c | The production of IBE was achieved using a cell immobilization system comprising concentric annular baskets packed with bagasse. | 0,18 | 0,31c | - | 0,35 c | [138] |

| Fed-batch | brewer’s spent grain | Clostridium beijerinckii DSM 6422 | Suspended | SHFiR | Sulfuric acid pretreatment Enzymatic hydrolysis |

10,20 65 a |

13,70b | Integration of a in-situ gas-stripping with ABE fermentation process, and evaluation of two feeding strategies: i) pulses of sugar and ii) continuous feeding of pretreatment liquids. | 0,14 | 0,20b | 0,11 | 0,15b | [133] |

| Fed-batch | Crude sugarcane bagasse and molasses | C. saccharoperbutylacetonicum DSM 14923 | Suspended | SHF | Diluted sulfuric acid for bagasse. Molasses did not require any previous hydrolysis | 10,80 | - | Use of molasses as a initial stage for bacteria growing before feeding of hydrolysates. | 0,31 | - | 0,15 | - | [139] |

| Fed-batch | Corn syrup | C. saccharobutylicum DSM 13864 | Suspended | DF | N. A | 8,70 | 16,68b | Evaluation of four clostridium strains for solvent production using corn syrup as substrate. | 0,18 | 0,34b | 0,24 | 0,47b | [80] |

| Fed-batch | Steam-exploded corn stover | C. acetobutylicum ABE-P 1201 | Suspended | SHF | Steam explosion Enzymatic hydrolysis with cellulase. Absorption with activated carbon. |

11,75 | 17,75b | A novel fed-batch process was employed, which combined pH adjusting and intermittent feeding, to address the limitations associated with steam explosion pre-treatment of corn stover. | 0,24 | 0,36b | 0,24 | 0,37b | [140] |

| Continuous | Glucose and butyric acid | C. acetobutylicum ATCC55025 | Immobilized | DF | N. A | 10,37 | 14,98b | Use of an asporogenous strain for butanol production in a single-pass fibrous-bed bioreactor. | 0,24 | 0,35b | 1,24 | 1,79b | [141] |

| Continuous | Glucose | Clostridium acetobutylicum DSM 792 | Immobilized | DFiR | N. A | 24 | - | Packed bed biofilm reactor with an integrated recovery using and absorption column. | 0,33 | - | 22 | - | [142] |

| Continuous | Glucose | Clostridium beijerinckii DSM6423 | Immobilized | DFiR | N. A | 7.5 | 13.5c | In this study, a fixed-bed bioreactor system was implemented using polyurethane foams as a solid support for the production of IBE. A model was successfully employed for describing fermentation performance. | 0,22 | 0,35c | 2.5 | - | [143] |

| Continuous | Food Waste | C. saccharoperbutylacetonicum deltptabuk | Immobilized | SHF | Liquefaction and Saccharification with enzymes (amylase and glucoamylase) | 9,46 (Dilution rate of 0,2 h-1) |

17,61b | Low-cost food wasted was used as a raw material for solvent production in batch and continuous bioreactors using a modified strain. | - | 0,43b | 1,90 | 3,45b | [144] |

| a: Condensate concentration, b: ABE, c: IBE | |||||||||||||

4.4. Downstream

| Method | Technique | Principle | Advantages | Drawbacks |

| Vapor-based | Gas stripping | Removing volatile solvents using gases and subsequent cooling to promote condensation. | Versatile, does not result in fouling, and poses no damage to the culture. | Poor selectivity, requires a lot of energy, and is restricted by the vapor-liquid equilibrium. |

| Vacuum fermentation/stripping | Decreasing the pressure of the vapor phase, altering the vapor-liquid equilibrium and solvents partition coefficient. | This technique is simple to use and does not harm the culture. | Low selectivity, high energy requirements, is constrained by vapor-liquid equilibrium, and high costs. | |

| Distillation | Solvents are fractionated based on their varying volatility levels. | Industrial-scale operation is simple, yielding dehydrated solvents of high purity and recovery rates. | The process is energy-intensive and requires high temperatures. | |

| Liquid-based | Liquid-liquid extraction | Differences in solubility between ABE and extractants enable selective separation. | High selectivity | The separation process is expensive and poses toxicity risks to the culture. |

| Salting-out | Salts are added to the aqueous phase in the two-aqueous phase extraction process to reduce ABE solubility. | Feasible, highly selective, and minimally impacts microbes due to its elevated osmotic pressure. | High salt dosage rate, poor continuity, equipment corrosion, and energy-intensive salt recycling | |

| Cloud point extraction | Above the cloud point temperature, a coacervate phase and a surfactant diluted phase are generated. | The process is easy to operate and does not result in fouling | The process is expensive, and surfactant recovery is complex, leading to issues with continuity and reliability. | |

| Adsorbent-based | Adsorption | Hydrophobic solids can be used to adsorb ABE | Ease of operation | High costs and has limited efficiency, capacity, and selectivity. |

| Membrane-based | Reverse osmosis | Semi-permeable membranes are utilized to selectively separate ABE from the fermentation broth. | This process offers high selectivity and does not harm the culture. | Elevated equipment costs and fouling problems. |

| Perstraction | ABE can be extracted into an extractant on the opposite side of a membrane. | High selectivity and has a low impact on the culture | High costs, fouling problems, and the formation of an extractant emulsion | |

| Pervaporation | ABE solvents can pass through a membrane via solution-diffusion by applying vacuum or sweeping gases. | High selectivity, high flux, and does not cause damage to the culture. | Membrane fouling, high costs, and the complexity of the processes involved | |

| Membrane distillation | Separating ABE via a microporous hydrophobic membrane at different temperatures. | No damage to the culture. | It is limited by vapor-liquid equilibrium, has small selectivity, and is a complicated process. | |

| Petlyuk system | Wall column distillation | This method requires different stages, in the preparation of the sample the temperature and pressure are regulated to avoid evaporation, subsequently the sample is heated, favoring the volatilization of the sample belonging to biobutanol. This wall column allows the components to be separated and fractionated, indicating degrees of purity. | Allow the separation of many substances depending on their boiling point and the constant purification of the biobutanol obtained |

It is an expensive, slow process that consumes a large amount of energy and time in the process of heating and cooling the sample. . |

5. New Approaches and Trends for Biobutanol

5.1. Use of Microalgae as Feedstock

| Strain used for ABE fermentation | Microalgae specie as substrate | Type of pretreatment. | Titer concentration of butanol gL-1 | ABE concentration (gL-1) | Source |

| C. acetobutylicum | Chlorella vulgaris JSC-6 | Alkali / acidic treatment with H2SO4 and NaOH | 13,1 | 19,9 | [155] |

| C. acetobutylicum ATCC824 | Biodiesel microalgae residues (Chlorella sorokiniana CY1) | Microwave. 2% H2SO4 heated at 121 °C, 60 min, and then 2% NaOH was added, during 60°C. |

3,9 | 6,3 | [153] |

| C. acetobutylicum ATCC824 | Chlorella sorokiniana | Dilute acid using H2SO4 at 0,5, 1, 5, and 2% (w/v) at 121°C. Enzymatic hydrolysis using α-amylase and amyloglucosidase. |

2,5 | 7,2 | [154] |

| C. acetobutylicum |

Chlorococcum humicola |

Dilute acid with 5% (w/v) H2SO4, and neutralization using CaCO3. | - | - | [160] |

| C. acetobutylicum ATCC824 | Neochloris aquatica | Pretreated with 1% NaOH, followed with 3% of H2SO4. | 12 | 19,6 | [156] |

| (C. acetobutylicum + C. thermocellum) a (C. beijerinckii + C. thermocellum) b |

Stichococcus sp. | Milling with mortar and pestle. Soaking in 2% H2SO4. Enzymatic hydrolysis with β-glucosidase. |

7,4a 8b |

12,3 a 14 b |

[161] |

| Not specified | Nannochloropsis gaditana | Acid treatment using H2SO4, H3PO4 and HCl (1, 2, 3, 4 and 5%). | 3 | - | [157] |

| C. acetobutylicum CGMCC1.0134 | Chlorella vulgaris | Dilute acid with 2% (v/v) H2SO4. Autoclave at 121°C. Neutralization with NaHCO3. |

8,5 | 14,2 | [162] |

5.2. Electron Donors in Fermentation to Enhance Butanol Productivity

5.3. Improving ABE Fermentation Using Co-Cultures

5.4. In-Situ Recovery and Multi-Stage Separation

| Fermentation operation mode | Separation technique | Approach | Solvent in the reactor (gL-1) | Concentrated solvent (gL-1) | References |

| Solvents of laboratory grade were used. | Gas stripping – Condensation | The ABE recovery system integrates gas stripping and a two-stage condensation process, incorporating an absorption section aiming the recovery of butanol. | 20a 13b |

204a 113b |

[184] |

| Fed-batch | in situ extraction-gas stripping | Oleyl acid is used for liquid-liquid extraction in the medium. Then, butanol is continuously removed by nitrogen stripping. The productivity of ABE fermentation is enhanced. | - ≈ 20b |

109,4a 63,8b |

[185] |

| Batch | - - |

360 – 460 a 200 – 250 b |

|||

| Immobilized Fed-Batch | Gas stripping–pervaporation | An immobilized bioreactor is connected to a condenser to recycle its vapor phase. After an initial fermentation of 30 hours, the gas stripping process was initiated, and the fist condensate is collected. Then, this condensate is separated by pervaporation using a Hydrophobic Polydimethylsiloxane membrane. | ≈17-22 a 10-12 b |

177,6 a 108,3 b |

[186] |

| Fed-Batch | Pervaporation and salting-out | The permeate was treated and separated using salting-out. After the in-situ recovery of ABE by pervaporation. | - | 805,5a 486,7b |

[187] |

| Fed-Batch | Gas stripping and salting-out | Recovery of solvents from a stage of gas stripping condensate was achieved using K4P2O7 and K2HPO4. | ≈ 12 -14a ≈ 9-10 b |

747,6a 520,3b |

[188] |

| Fed-batch fermentation with cell immobilization | Pervaporation - pervaporation | Following a first stage pervaporation, the permeate was utilized for feeding the second stage pervaporation, which used hydrophilic and hydrophobic membranes in this study. The permeate obtained from the second stage was collected. | ≈ 20 -23 a 8,9 b |

671,1 a 515.3 b |

[189] |

| Batch | Gas stripping-pervaporation | Butanol was continuously extracted from the fermentation broth using gas stripping, followed by further concentration of the extracted butanol through pervaporation. | ≈ 16,5c ≈ 10b |

712,4 c 558,9 b |

[190] |

| An aqueous butanol solution, close to the current tolerance limit for biofuel microbes. | Membrane vapor extraction | In membrane vapor extraction, the feed and solvent liquids remain unconnected, separated by vapor. A semi-volatile aqueous solute (butanol) undergoes vaporization at the upstream side of a membrane. It then diffuses as a vapor through the membrane pores, subsequently condensing and dissolving into a high-boiling nonpolar solvent that is favorable to the solute but not to water. |

20b | 970b | [191] |

|

Petlyuk arrangement |

Wall column distillation | ||||

| Membrane vapor extraction | |||||

| Gas entrapment membranes | |||||

| Direct steam distillation | |||||

| aABE, b Butanol, c IBE | |||||

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Nomenclature

| ABE | Acetone-butanol-ethanol |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| BSFC | Break Specific Fuel Consumption |

| BTE | Break Thermal Efficiency |

| CO | Carbon Monoxide |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| DF | Direct fermentation |

| DFiR | Direct fermentation within situ recovery |

| FAME | Fatty Acid Methyl Ester |

| H2O | Water |

| HC | Hydrocarbons |

|

IBE IEA |

Isopropanol-n-butanol-ethanol International Energy Agency |

| NOX | Nitrogen Oxides |

| PAH | Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon |

| PM | Particulate matter |

| RPM | Revolutions per minute |

| SHF | Separate hydrolysis and fermentation |

| SHFiR | Separate hydrolysis and fermentation within situ recovery |

| SSF | Simultaneous saccharification and fermentation |

| SSFiR | Simultaneous saccharification and fermentation within situ recovery |

References

- IHS Markit, “Integrated intelligence for the biofuels sector including market reporting, price assessment, trends analysis, and medium to long-term fundamentals-based forecasting across the biofuels value chain.” Accessed: May 16, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://ihsmarkit.com/products/biofuels.html?utm_source=google&utm_medium=ppc&utm_campaign=PC021957&utm_term=biodiesel outlook&utm_network=g&device=c&matchtype=b.

- IEA, “Biofuels,” Low-Emission Fuels. Accessed: Aug. 31, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.iea.org/energy-system/low-emission-fuels/biofuels.

- V. C. A. Ward, “Biofuels,” in New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering, Elsevier, 2020, pp. 153–162. [CrossRef]

- L. Casas-Godoy et al., “Biofuels,” in Biobased Products and Industries, Elsevier, 2020, pp. 125–170. [CrossRef]

- N. Srivastava et al., “Role of Compositional Analysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Efficient Biofuel Production,” in New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering, Elsevier, 2019, pp. 29–43. [CrossRef]

- P. Zhu, O. Y. Abdelaziz, C. P. Hulteberg, and A. Riisager, “New synthetic approaches to biofuels from lignocellulosic biomass,” Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem, vol. 21, pp. 16–21, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Hill, E. Nelson, D. Tilman, S. Polasky, and D. Tiffany, “Environmental, economic, and energetic costs and benefits of biodiesel and ethanol biofuels,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 103, no. 30, pp. 11206–11210, Jul. 2006. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Chandel and O. V. Singh, “Weedy lignocellulosic feedstock and microbial metabolic engineering: advancing the generation of ‘Biofuel,’” Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, vol. 89, no. 5, pp. 1289–1303, Mar. 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. Pant, A. Gupta, G. Pant, K. K. Chaubey, G. Kumar, and N. Patrick, “Second-generation biofuels: Facts and future,” in Relationship Between Microbes and the Environment for Sustainable Ecosystem Services, Volume 3, Elsevier, 2023, pp. 97–115. [CrossRef]

- European Parliament, “Directive 2009/28/EC of the European Parliament and of. Council of 23 April 2009 on the promotion of the use of energy from renewable sources and amending and subsequently repealing Directives 2001/77/EC and 2003/30/EC.” 2009. [Online]. Available: ttps://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=celex%3A32009L0028.

- J. Sánchez, M. D. Curt, N. Robert, and J. Fernández, “Biomass Resources,” in The Role of Bioenergy in the Bioeconomy, Elsevier, 2019, pp. 25–111. [CrossRef]

- N. Scarlat, F. Fahl, and J.-F. Dallemand, “Status and Opportunities for Energy Recovery from Municipal Solid Waste in Europe,” Waste Biomass Valorization, vol. 10, no. 9, pp. 2425–2444, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. A. Situmorang and G. Guan, “Power Production from Biomass,” in Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences, Elsevier, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Loha, M. K. Karmakar, H. Chattopadhyay, and G. Majumdar, “Renewable Biomass: A Candidate for Mitigating Global Warming,” in Encyclopedia of Renewable and Sustainable Materials, Elsevier, 2020, pp. 715–727. [CrossRef]

- P. Zhu, O. Abdelaziz, C. P. Hulteberg, and A. Riisager, “New synthetic approaches to biofuels from lignocellulosic biomass,” Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem, vol. 21, pp. 16–21, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Karim, M. A. Islam, P. Mishra, A. Yousuf, C. K. M. Faizal, and Md. M. R. Khan, “Technical difficulties of mixed culture driven waste biomass-based biohydrogen production: Sustainability of current pretreatment techniques and future prospective,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 151, p. 111519, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Thamizhakaran Stanley et al., “Potential pre-treatment of lignocellulosic biomass for the enhancement of biomethane production through anaerobic digestion- A review,” Fuel, vol. 318, p. 123593, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. J. R. Nunes, “Biomass gasification as an industrial process with effective proof-of-concept: A comprehensive review on technologies, processes and future developments,” Results in Engineering, vol. 14, p. 100408, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Chen et al., “A review on recycling techniques for bioethanol production from lignocellulosic biomass,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 149, p. 111370, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Kushwaha et al., “Waste biomass to biobutanol: recent trends and advancements,” in Waste-to-Energy Approaches Towards Zero Waste, Elsevier, 2022, pp. 393–423. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Hoekman, “Biofuels in the U.S. – Challenges and Opportunities,” Renew Energy, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 14–22, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Mohd Azhar et al., “Yeasts in sustainable bioethanol production: A review,” Biochem Biophys Rep, vol. 10, pp. 52–61, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Das, S. K. Sahu, and A. K. Panda, “Current status and prospects of alternate liquid transportation fuels in compression ignition engines: A critical review,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 161, p. 112358, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Kunwer, S. Ranjit Pasupuleti, S. Sureshchandra Bhurat, S. Kumar Gugulothu, and N. Rathore, “Blending of ethanol with gasoline and diesel fuel – A review,” Mater Today Proc, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Sakthivel, K. A. Subramanian, and R. Mathai, “Experimental study on unregulated emission characteristics of a two-wheeler with ethanol-gasoline blends (E0 to E50),” Fuel, vol. 262, p. 116504, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Mishra and A. Dubey, “Biobutanol: An Alternative Biofuel,” in Advances in Biofeedstocks and Biofuels, Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2017, pp. 155–175. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhen, Y. Wang, and D. Liu, “Bio-butanol as a new generation of clean alternative fuel for SI (spark ignition) and CI (compression ignition) engines,” Renew Energy, vol. 147, pp. 2494–2521, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Choi, J. Han, and J. Lee, “Renewable Butanol Production via Catalytic Routes,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 18, no. 22, p. 11749, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Fernandez, “Global n-Butanol market volume 2015-2029,” Statista. [Online]. Available: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1245211/n-butanol-market-volume-worldwide/.

- C. Karthick and K. Nanthagopal, “A comprehensive review on ecological approaches of waste to wealth strategies for production of sustainable biobutanol and its suitability in automotive applications,” Energy Convers Manag, vol. 239, p. 114219, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Jiang et al., “Current status and perspectives on biobutanol production using lignocellulosic feedstocks,” Bioresour Technol Rep, vol. 7, p. 100245, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Patil, P. G. Suryawanshi, R. Kataki, and V. V. Goud, “Current challenges and advances in butanol production,” in Sustainable Bioenergy, Elsevier, 2019, pp. 225–256. [CrossRef]

- S. Nanda, A. K. Dalai, and J. A. Kozinski, “Butanol and ethanol production from lignocellulosic feedstock: biomass pretreatment and bioconversion,” Energy Sci Eng, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 138–148, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Göktas, M. K. Balki, C. Sayin, and M. Canakci, “An evaluation of the use of alcohol fuels in SI engines in terms of performance, emission and combustion characteristics: A review,” Fuel, vol. 286, no. 2021, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Gupta, P. Mondal, V. B. Borugadda, and A. K. Dalai, “Advances in upgradation of pyrolysis bio-oil and biochar towards improvement in bio-refinery economics: A comprehensive review,” Environ Technol Innov, vol. 21, p. 101276, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Gad, “Diesel Fuel,” in Encyclopedia of Toxicology, 2014, pp. 115–118. [CrossRef]

- Anna and G. Wypych, “Fatty acid methyl esters,” in Databook of Green Solvents, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 135–203. [CrossRef]

- G.-L. Xu, C.-D. Yao, and C. J. Rutland, “Simulations of diesel–methanol dual-fuel engine combustion with large eddy simulation and Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes model,” International Journal of Engine Research, vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 751–769, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. Bay, H. Wanko, and J. Ulrich, “Absorption of Volatile Organic Compounds in Biodiesel,” Chemical Engineering Research and Design, vol. 84, no. 1, pp. 22–28, Jan. 2006. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Hoekman, A. Broch, C. Robbins, E. Ceniceros, and M. Natarajan, “Review of biodiesel composition, properties, and specifications,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 143–169, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- D. Singh, D. Sharma, S. L. Soni, S. Sharma, and D. Kumari, “Chemical compositions, properties, and standards for different generation biodiesels: A review,” Fuel, vol. 253, pp. 60–71, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- I. E. Yousif and A. M. Saleh, “Butanol-gasoline blends impact on performance and exhaust emissions of a four stroke spark ignition engine,” Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, vol. 41, p. 102612, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- World Nuclear Association, “Heat Values of Various Fuels.” [Online]. Available: https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/facts-and-figures/heat-values-of-various-fuels.aspx.

- E. Torres-Jimenez, M. S. Jerman, A. Gregorc, I. Lisec, M. P. Dorado, and B. Kegl, “Physical and chemical properties of ethanol–diesel fuel blends,” Fuel, vol. 90, no. 2, pp. 795–802, Feb. 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. Krishnasamy and K. R. Bukkarapu, “A comprehensive review of biodiesel property prediction models for combustion modeling studies,” Fuel, vol. 302, p. 121085, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. N. A. M. Yusoff et al., “Performance and emission characteristics of a spark ignition engine fuelled with butanol isomer-gasoline blends,” Transp Res D Transp Environ, vol. 57, pp. 23–38, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Z. Tian, X. Zhen, Y. Wang, L. Daming, and X. Li, “Combustion and emission characteristics of n-butanol-gasoline blends in SI direct injection gasoline engine,” Renew Energy, vol. 146, pp. 267–279, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Sayin and M. K. Balki, “Effect of compression ratio on the emission, performance and combustion characteristics of a gasoline engine fueled with iso-butanol/gasoline blends,” Energy, vol. 82, pp. 550–555, Mar. 2015. [CrossRef]

- N. Mittal, R. Leslie Athony, R. Bansal, and K. C. Ramesh, “Study of performance and emission characteristics of a partially coated LHR SI engine blended with n-butanol and gasoline,” Alexandria Engineering Journal, vol. 53, no. 3, pp. 285–293, 2013. [CrossRef]

- I. E. Yousif and A. M. Saleh, “Butanol-gasoline blends impact on performance and exhaust emissions of a four stroke spark ignition engine,” Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, vol. 41, p. 102612, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Şahin, O. Nazım Aksu, and C. Bayram, “The effects of n-butanol/gasoline blends and 2.5% n-butanol/gasoline blend with 9% water injection into the intake air on the SIE engine performance and exhaust emissions,” Fuel, vol. 303, p. 121210, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z.-H. Zhang and R. Balasubramanian, “Influence of butanol addition to diesel–biodiesel blend on engine performance and particulate emissions of a stationary diesel engine,” Appl Energy, vol. 119, pp. 530–536, Apr. 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. Xiao, F. Guo, R. Wang, X. Yang, S. Li, and J. Ruan, “Combustion performance and emission characteristics of diesel engine fueled with iso-butanol/biodiesel blends,” Fuel, vol. 268, p. 117387, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Thakkar, S. S. Kachhwaha, P. Kodgire, and S. Srinivasan, “Combustion investigation of ternary blend mixture of biodiesel/n-butanol/diesel: CI engine performance and emission control,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 137, p. 110468, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Goga, B. S. Chauhan, S. K. Mahla, and H. M. Cho, “Performance and emission characteristics of diesel engine fueled with rice bran biodiesel and n-butanol,” Energy Reports, vol. 5, pp. 78–83, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. Dinesha, S. Mohan, and S. Kumar, “Experimental investigation of SI engine characteristics using Acetone-Butanol-Ethanol (ABE) – Gasoline blends and optimization using Particle Swarm Optimization,” Int J Hydrogen Energy, vol. 47, no. 8, pp. 5692–5708, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. F. dos Santos Vieira, F. Maugeri Filho, R. Maciel Filho, and A. Pinto Mariano, “Acetone-free biobutanol production: Past and recent advances in the Isopropanol-Butanol-Ethanol (IBE) fermentation,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 287, p. 121425, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Z. Guo, X. Yu, Y. Du, and T. Wang, “Comparative study on combustion and emissions of SI engine with gasoline port injection plus acetone-butanol-ethanol (ABE), isopropanol-butanol-ethanol (IBE) or butanol direct injection,” Fuel, vol. 316, p. 123363, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Veza, M. F. M. Said, and Z. A. Latiff, “Progress of acetone-butanol-ethanol (ABE) as biofuel in gasoline and diesel engine: A review,” Fuel Processing Technology, vol. 196, p. 106179, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Balat, H. Balat, and C. Öz, “Progress in bioethanol processing,” Prog Energy Combust Sci, vol. 34, no. 5, pp. 551–573, Oct. 2008. [CrossRef]

- H. Yun, K. Choi, and C. S. Lee, “Effects of biobutanol and biobutanol–diesel blends on combustion and emission characteristics in a passenger car diesel engine with pilot injection strategies,” Energy Convers Manag, vol. 111, pp. 79–88, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- V. L. Pachapur, S. J. Sarma, S. K. Brar, and E. Chaabouni, “Platform Chemicals,” in Platform Chemical Biorefinery, Elsevier, 2016, pp. 1–20. [CrossRef]

- C. Weizmann, “PRODUCTION OF ACETONE AND ALCOHOL BY BACTEBIOLOGTCAL PROCESSES.,” US1315585A, 1919 [Online]. Available: https://patents.google.com/patent/US1315585A/en?oq=Patent+1%2C315%2C585%2C+1919.

- D. T. JONES, “THE STRATEGIC IMPORTANCE OF BUTANOL FOR JAPAN DURING WWII: A CASE STUDY OF THE BUTANOL FERMENTATION PROCESS IN TAIWAN AND JAPAN,” in Systems Biology of Clostridium, IMPERIAL COLLEGE PRESS, 2014, pp. 220–272. [CrossRef]

- N.-P.-T. Nguyen, C. Raynaud, I. Meynial-Salles, and P. Soucaille, “Reviving the Weizmann process for commercial n-butanol production,” Nat Commun, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 3682, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. Qureshi, “Solvent (Acetone–Butanol: AB) Production ☆,” in Reference Module in Life Sciences, Elsevier, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Amiri and K. Karimi, “Biobutanol Production,” in Advanced Bioprocessing for Alternative Fuels, Biobased Chemicals, and Bioproducts, Elsevier, 2019, pp. 109–133. [CrossRef]

- R. Vinoth Kumar, K. Pakshirajan, and G. Pugazhenthi, “Petroleum Versus Biorefinery-Based Platform Chemicals,” in Platform Chemical Biorefinery, Elsevier, 2016, pp. 33–53. [CrossRef]

- H. G. Moon, Y.-S. Jang, C. Cho, J. Lee, R. Binkley, and S. Y. Lee, “One hundred years of clostridial butanol fermentation,” FEMS Microbiol Lett, p. fnw001, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. Birgen, P. Dürre, H. A. Preisig, and A. Wentzel, “Butanol production from lignocellulosic biomass: revisiting fermentation performance indicators with exploratory data analysis,” Biotechnol Biofuels, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 167, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Qureshi, “Solvent (Acetone–Butanol: AB) Production ☆,” in Reference Module in Life Sciences, Elsevier, 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. K. Sarangi and S. Nanda, “Recent Developments and Challenges of Acetone-Butanol-Ethanol Fermentation,” in Recent Advancements in Biofuels and Bioenergy Utilization, Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2018, pp. 111–123. [CrossRef]

- B. O. Abo, M. Gao, Y. Wang, C. Wu, Q. Wang, and H. Ma, “Production of butanol from biomass: recent advances and future prospects,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research, vol. 26, no. 20, pp. 20164–20182, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Nandhini, S. S. Rameshwar, B. Sivaprakash, N. Rajamohan, and R. S. Monisha, “Carbon neutrality in biobutanol production through microbial fermentation technique from lignocellulosic materials – A biorefinery approach,” J Clean Prod, vol. 413, p. 137470, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Qi et al., “Solvents production from cassava by co-culture of Clostridium acetobutylicum and Saccharomyces cerevisiae,” J Environ Chem Eng, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 128–133, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. B. da Silva, B. S. Fernandes, and A. J. da Silva, “Butanol production by Clostridium acetobutylicum DSMZ 792 from cassava starch,” Environmental Sustainability, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 91–102, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. H. Thang and G. Kobayashi, “A Novel Process for Direct Production of Acetone–Butanol–Ethanol from Native Starches Using Granular Starch Hydrolyzing Enzyme by Clostridium saccharoperbutylacetonicum N1-4,” Appl Biochem Biotechnol, vol. 172, no. 4, pp. 1818–1831, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Zuleta-Correa, M. S. Chinn, and J. M. Bruno-Bárcena, “Application of raw industrial sweetpotato hydrolysates for butanol production by Clostridium beijerinckii NCIMB 8052,” Biomass Convers Biorefin, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Avcı, A. Kamiloğlu, and S. Dönmez, “Efficient production of acetone butanol ethanol from sole fresh and rotten potatoes by various Clostridium strains,” Biomass Convers Biorefin, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Niglio, A. Marzocchella, and L. Rehmann, “Clostridial conversion of corn syrup to Acetone-Butanol-Ethanol (ABE) via batch and fed-batch fermentation,” Heliyon, vol. 5, no. 3, p. e01401, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Qi et al., “Hydrotropic pretreatment on wheat straw for efficient biobutanol production,” Biomass Bioenergy, vol. 122, pp. 76–83, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. D. Gottumukkala, B. Parameswaran, S. K. Valappil, K. Mathiyazhakan, A. Pandey, and R. K. Sukumaran, “Biobutanol production from rice straw by a non acetone producing Clostridium sporogenes BE01,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 145, pp. 182–187, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Mohapatra, R. Ranjan Mishra, B. Nayak, B. Chandra Behera, and P. K. Das Mohapatra, “Development of co-culture yeast fermentation for efficient production of biobutanol from rice straw: A useful insight in valorization of agro industrial residues,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 318, p. 124070, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Wu et al., “A novel integrated process to convert cellulose and hemicellulose in rice straw to biobutanol,” Environ Res, vol. 186, p. 109580, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Kuittinen et al., “Technoeconomic analysis and environmental sustainability estimation of bioalcohol production from barley straw,” Biocatal Agric Biotechnol, vol. 43, p. 102427, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Desta, T. Lee, and H. Wu, “Well-to-wheel analysis of energy use and greenhouse gas emissions of acetone-butanol-ethanol from corn and corn stover,” Renew Energy, vol. 170, pp. 72–80, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Lin, Y. Liu, X. Zheng, and N. Qureshi, “High-efficient cellulosic butanol production from deep eutectic solvent pretreated corn stover without detoxification,” Ind Crops Prod, vol. 162, p. 113258, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhang et al., “Impact of corn stover harvest time and cultivars on acetone-butanol-ethanol production,” Ind Crops Prod, vol. 139, p. 111500, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Abedini, H. Amiri, and K. Karimi, “Efficient biobutanol production from potato peel wastes by separate and simultaneous inhibitors removal and pretreatment,” Renew Energy, vol. 160, pp. 269–277, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Saadatinavaz, K. Karimi, and J. F. M. Denayer, “Hydrothermal pretreatment: An efficient process for improvement of biobutanol, biohydrogen, and biogas production from orange waste via a biorefinery approach,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 341, p. 125834, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Khedkar, P. R. Nimbalkar, S. P. Kamble, S. G. Gaikwad, P. V. Chavan, and S. B. Bankar, “Process intensification strategies for enhanced holocellulose solubilization: Beneficiation of pineapple peel waste for cleaner butanol production,” J Clean Prod, vol. 199, pp. 937–947, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Q. Jin, N. Qureshi, H. Wang, and H. Huang, “Acetone-butanol-ethanol (ABE) fermentation of soluble and hydrolyzed sugars in apple pomace by Clostridium beijerinckii P260,” Fuel, vol. 244, pp. 536–544, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Chacón, G. Matias, T. C. Ezeji, R. Maciel Filho, and A. P. Mariano, “Three-stage repeated-batch immobilized cell fermentation to produce butanol from non-detoxified sugarcane bagasse hemicellulose hydrolysates,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 321, p. 124504, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Kumar, L. K. S. Gujjala, and R. Banerjee, “Simultaneous pretreatment and saccharification of bamboo for biobutanol production,” Ind Crops Prod, vol. 101, pp. 21–28, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. I. Al-Tabib, N. K. N. Al-Shorgani, H. A. Hasan, A. A. Hamid, and M. S. Kalil, “Assessment of the detoxification of palm kernel cake hydrolysate for butanol production by Clostridium acetobutylicum YM1,” Biocatal Agric Biotechnol, vol. 13, pp. 105–109, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. Luo et al., “A facile and efficient pretreatment of corncob for bioproduction of butanol,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 140, pp. 86–89, Jul. 2013. [CrossRef]

- K. Gao and L. Rehmann, “ABE fermentation from enzymatic hydrolysate of NaOH-pretreated corncobs,” Biomass Bioenergy, vol. 66, pp. 110–115, Jul. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. Jiang et al., “Inhibitors tolerance analysis of Clostridium sp. strain LJ4 and its application for butanol production from corncob hydrolysate through electrochemical detoxification,” Biochem Eng J, vol. 167, p. 107891, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Procentese, F. Raganati, G. Olivieri, M. Elena Russo, and A. Marzocchella, “Pre-treatment and enzymatic hydrolysis of lettuce residues as feedstock for bio-butanol production,” Biomass Bioenergy, vol. 96, pp. 172–179, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Ebrahimian, K. Karimi, and I. Angelidaki, “Coproduction of hydrogen, butanol, butanediol, ethanol, and biogas from the organic fraction of municipal solid waste using bacterial cocultivation followed by anaerobic digestion,” Renew Energy, vol. 194, pp. 552–560, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Díez, M. Hijosa, A. Paniagua, and X. Gómez, “Effect of nutrient supplementation on biobutanol production from cheese whey by ABE (Acetone-Butanol-Ethanol) fermentation,” Chem Eng Trans, vol. 49, pp. 217–222, 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. D. Gottumukkala, A. K. Mathew, A. Abraham, and R. K. Sukumaran, “Biobutanol Production: Microbes, Feedstock, and Strategies,” in Biofuels: Alternative Feedstocks and Conversion Processes for the Production of Liquid and Gaseous Biofuels, Elsevier, 2019, pp. 355–377. [CrossRef]

- T. Chen et al., “High butanol production from glycerol by using Clostridium sp. strain CT7 integrated with membrane assisted pervaporation,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 288, p. 121530, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. Branska et al., “Chicken feather and wheat straw hydrolysate for direct utilization in biobutanol production,” Renew Energy, vol. 145, pp. 1941–1948, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, H. Zhou, D. Liu, and X. Zhao, “Pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for efficient enzymatic saccharification of cellulose,” in Lignocellulosic Biomass to Liquid Biofuels, Elsevier, 2020, pp. 17–65. [CrossRef]

- G. P. Naik, A. K. Poonia, and P. K. Chaudhari, “Pretreatment of lignocellulosic agricultural waste for delignification, rapid hydrolysis, and enhanced biogas production: A review,” Journal of the Indian Chemical Society, vol. 98, no. 10, p. 100147, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Kumar and S. Sharma, “Recent updates on different methods of pretreatment of lignocellulosic feedstocks: a review,” Bioresour Bioprocess, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 7, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S.-Y. Jeong, L. T. P. Trinh, H.-J. Lee, and J.-W. Lee, “Improvement of the fermentability of oxalic acid hydrolysates by detoxification using electrodialysis and adsorption,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 152, pp. 444–449, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. Llano, N. Quijorna, and A. Coz, “Detoxification of a Lignocellulosic Waste from a Pulp Mill to Enhance Its Fermentation Prospects,” Energies (Basel), vol. 10, no. 3, p. 348, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wu, Z. Wang, X. Ma, and C. Xue, “High temperature simultaneous saccharification and fermentation of corn stover for efficient butanol production by a thermotolerant Clostridium acetobutylicum,” Process Biochemistry, vol. 100, pp. 20–25, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. F. do Nascimento et al., “Detoxification of sisal bagasse hydrolysate using activated carbon produced from the gasification of açaí waste,” J Hazard Mater, vol. 409, p. 124494, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Devi, A. Singh, S. Bajar, D. Pant, and Z. U. Din, “Ethanol from lignocellulosic biomass: An in-depth analysis of pre-treatment methods, fermentation approaches and detoxification processes,” J Environ Chem Eng, vol. 9, no. 5, p. 105798, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Maiti et al., “Two-phase partitioning detoxification to improve biobutanol production from brewery industry wastes,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 330, pp. 1100–1108, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Raj et al., “Critical challenges and technological breakthroughs in food waste hydrolysis and detoxification for fuels and chemicals production,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 360, p. 127512, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. C. López-Linares, M. T. García-Cubero, M. Coca, and S. Lucas, “Efficient biobutanol production by acetone-butanol-ethanol fermentation from spent coffee grounds with microwave assisted dilute sulfuric acid pretreatment,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 320, p. 124348, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Khunchit, S. Nitayavardhana, R. Ramaraj, V. K. Ponnusamy, and Y. Unpaprom, “Liquid hot water extraction as a chemical-free pretreatment approach for biobutanol production from Cassia fistula pods,” Fuel, vol. 279, p. 118393, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Farmanbordar, H. Amiri, and K. Karimi, “Simultaneous organosolv pretreatment and detoxification of municipal solid waste for efficient biobutanol production,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 270, pp. 236–244, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Dou, V. Chandgude, T. Vuorinen, S. Bankar, S. Hietala, and H. Q. Lê, “Enhancing Biobutanol Production from biomass willow by pre-removal of water extracts or bark,” J Clean Prod, vol. 327, p. 129432, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Pratto, V. Chandgude, R. de Sousa, A. J. G. Cruz, and S. Bankar, “Biobutanol production from sugarcane straw: Defining optimal biomass loading for improved ABE fermentation,” Ind Crops Prod, vol. 148, p. 112265, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Qi, D. Huang, J. Wang, Y. Shen, and X. Gao, “Enhanced butanol production from ammonium sulfite pretreated wheat straw by separate hydrolysis and fermentation and simultaneous saccharification and fermentation,” Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments, vol. 36, p. 100549, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. del Amo-Mateos, J. C. López-Linares, M. T. García-Cubero, S. Lucas, and M. Coca, “Green biorefinery for sugar beet pulp valorisation: Microwave hydrothermal processing for pectooligosaccharides recovery and biobutanol production,” Ind Crops Prod, vol. 184, p. 115060, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Schultze-Jena et al., “Production of acetone, butanol, and ethanol by fermentation of Saccharina latissima: Cultivation, enzymatic hydrolysis, inhibitor removal, and fermentation,” Algal Res, vol. 62, p. 102618, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. López-Linares, M. T. Garcia-Cubero, S. Lucas, and M. Coca, “Integral valorization of cellulosic and hemicellulosic sugars for biobutanol production: ABE fermentation of the whole slurry from microwave pretreated brewer’s spent grain,” Biomass Bioenergy, vol. 135, pp. 1–12, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhou, S. Yang, C. D. Moore, Q. Zhang, S. Peng, and H. Li, “Acetone, butanol, and ethanol production from puerariae slag hydrolysate through ultrasound-assisted dilute acid by Clostridium beijerinckii YBS3,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 316, p. 123899, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. A. Castro, J. T. Ellis, C. D. Miller, and R. C. Sims, “Optimization of wastewater microalgae saccharification using dilute acid hydrolysis for acetone, butanol, and ethanol fermentation,” Appl Energy, vol. 140, pp. 14–19, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Amiri and K. Karimi, “Biobutanol Production,” in Advanced Bioprocessing for Alternative Fuels, Biobased Chemicals, and Bioproducts, Elsevier, 2019, pp. 109–133. [CrossRef]

- H. Janssen, Y. Wang, and H. P. Blaschek, “CLOSTRIDIUM | Clostridium acetobutylicum,” in Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 449–457. [CrossRef]

- Y.-N. Zheng et al., “Problems with the microbial production of butanol,” J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol, vol. 36, no. 9, pp. 1127–1138, Sep. 2009. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Sukumaran, L. D. Gottumukkala, K. Rajasree, D. Alex, and A. Pandey, “Butanol Fuel from Biomass,” in Biofuels, Elsevier, 2011, pp. 571–586. [CrossRef]

- B. Kolesinska et al., “Butanol Synthesis Routes for Biofuel Production: Trends and Perspectives,” Materials, vol. 12, no. 3, p. 350, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Y. Lee, J. H. Park, S. H. Jang, L. K. Nielsen, J. Kim, and K. S. Jung, “Fermentative butanol production by clostridia,” Biotechnol Bioeng, vol. 101, no. 2, pp. 209–228, Oct. 2008. [CrossRef]

- C. Xue and C. Cheng, “Butanol production by Clostridium,” 2019, pp. 35–77. [CrossRef]

- P. E. Plaza, M. Coca, S. L. Yagüe, G. Gutiérrez, E. Rochón, and M. T. García-Cubero, “Bioprocess intensification for acetone-butanol-ethanol fermentation from brewer’s spent grain: Fed-batch strategies coupled with in-situ gas stripping,” Biomass Bioenergy, vol. 156, p. 106327, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Valles, J. Álvarez-Hornos, M. Capilla, P. San-Valero, and C. Gabaldón, “Fed-batch simultaneous saccharification and fermentation including in-situ recovery for enhanced butanol production from rice straw,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 342, p. 126020, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Liu et al., “Process optimization of acetone-butanol-ethanol fermentation integrated with pervaporation for enhanced butanol production,” Biochem Eng J, vol. 173, p. 108070, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Cai, C. Chen, C. Zhang, Y. Wang, H. Wen, and P. Qin, “Fed-batch fermentation with intermittent gas stripping using immobilized Clostridium acetobutylicum for biobutanol production from corn stover bagasse hydrolysate,” Biochem Eng J, vol. 125, pp. 18–22, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. Tekin, S. E. Karatay, and G. Dönmez, “Optimization studies about efficient biobutanol production from industrial tea waste by Clostridium beijerinckii,” Fuel, vol. 331, p. 125763, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Ferreira dos Santos Vieira, A. Duzi Sia, F. Maugeri Filho, R. Maciel Filho, and A. Pinto Mariano, “Isopropanol-butanol-ethanol production by cell-immobilized vacuum fermentation,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 344, p. 126313, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Chacón, G. Matias, C. F. dos S. Vieira, T. C. Ezeji, R. Maciel Filho, and A. P. Mariano, “Enabling butanol production from crude sugarcane bagasse hemicellulose hydrolysate by batch-feeding it into molasses fermentation,” Ind Crops Prod, vol. 155, p. 112837, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Su et al., “Combination of pH adjusting and intermittent feeding can improve fermentative acetone-butanol-ethanol (ABE) production from steam exploded corn stover,” Renew Energy, vol. 200, pp. 592–600, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Chang, W. Hou, M. Xu, and S. Yang, “High-rate continuous n -butanol production by Clostridium acetobutylicum from glucose and butyric acid in a single-pass fibrous-bed bioreactor,” Biotechnol Bioeng, vol. 119, no. 12, pp. 3474–3486, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Raganati, A. Procentese, G. Olivieri, M. E. Russo, P. Salatino, and A. Marzocchella, “A novel integrated fermentation/recovery system for butanol production by Clostridium acetobutylicum,” Chemical Engineering and Processing - Process Intensification, vol. 173, p. 108852, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Carrié, H. Velly, F. Ben-Chaabane, and J.-C. Gabelle, “Modeling fixed bed bioreactors for isopropanol and butanol production using Clostridium beijerinckii DSM 6423 immobilized on polyurethane foams,” Biochem Eng J, vol. 180, p. 108355, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Q. Jin et al., “High Acetone-Butanol-Ethanol Production from Food Waste by Recombinant Clostridium saccharoperbutylacetonicum in Batch and Continuous Immobilized-Cell Fermentation,” ACS Sustain Chem Eng, vol. 8, no. 26, pp. 9822–9832, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Chadni, M. Moussa, V. Athès, F. Allais, and I. Ioannou, “Membrane contactors-assisted liquid-liquid extraction of biomolecules from biorefinery liquid streams: A case study on organic acids,” Sep Purif Technol, vol. 317, p. 123927, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Cai et al., “Review of alternative technologies for acetone-butanol-ethanol separation: Principles, state-of-the-art, and development trends,” Sep Purif Technol, vol. 298, p. 121244, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang et al., “Current advances on fermentative biobutanol production using third generation feedstock,” Biotechnol Adv, vol. 35, no. 8, pp. 1049–1059, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Bradley, J. Ling-Chin, D. Maga, L. G. Speranza, and A. P. Roskilly, “Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Algae Biofuels,” in Comprehensive Renewable Energy, Elsevier, 2022, pp. 387–404. [CrossRef]

- T. K. Yeong, K. Jiao, X. Zeng, L. Lin, S. Pan, and M. K. Danquah, “Microalgae for biobutanol production – Technology evaluation and value proposition,” Algal Res, vol. 31, pp. 367–376, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Onay, “Biobutanol from microalgae,” in 3rd Generation Biofuels, Elsevier, 2022, pp. 547–569. [CrossRef]

- H. Shokravi et al., “Fourth generation biofuel from genetically modified algal biomass for bioeconomic development,” J Biotechnol, vol. 360, pp. 23–36, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Shanmugam et al., “Recent developments and strategies in genome engineering and integrated fermentation approaches for biobutanol production from microalgae,” Fuel, vol. 285, p. 119052, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H.-H. Cheng et al., “Biological butanol production from microalgae-based biodiesel residues by Clostridium acetobutylicum,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 184, pp. 379–385, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Yang et al., “Glucose Conversion for Biobutanol Production from Fresh Chlorella sorokiniana via Direct Enzymatic Hydrolysis,” Fermentation, vol. 9, no. 3, p. 284, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, W. Guo, C.-L. Cheng, S.-H. Ho, J.-S. Chang, and N. Ren, “Enhancing bio-butanol production from biomass of Chlorella vulgaris JSC-6 with sequential alkali pretreatment and acid hydrolysis,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 200, pp. 557–564, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang et al., “Nutrients and COD removal of swine wastewater with an isolated microalgal strain Neochloris aquatica CL-M1 accumulating high carbohydrate content used for biobutanol production,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 242, pp. 7–14, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Onay, “Enhancing carbohydrate productivity from Nannochloropsis gaditana for bio-butanol production,” Energy Reports, vol. 6, pp. 63–67, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu et al., “A review on the promising fuel of the future – Biobutanol; the hindrances and future perspectives,” Fuel, vol. 327, p. 125166, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Phillips, “Algal Butanol Production,” 2020, pp. 33–50. [CrossRef]

- G. Narchonai, C. Arutselvan, F. LewisOscar, and N. Thajuddin, “Enhancing starch accumulation/production in Chlorococcum humicola through sulphur limitation and 2,4- D treatment for butanol production,” Biotechnology Reports, vol. 28, p. e00528, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Fiayaz and Y. Dahman, “Greener approach to the comprehensive utilization of algal biomass and oil using novel Clostridial fusants and bio-based solvents,” Engineering Microbiology, vol. 3, no. 2, p. 100068, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Mao and B. Zhang, “Combining ABE fermentation and anaerobic digestion to treat with lipid extracted algae for enhanced bioenergy production,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 875, p. 162691, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C.-G. Liu, J.-C. Qin, and Y.-H. Lin, “Fermentation and Redox Potential,” in Fermentation Processes, InTech, 2017. [CrossRef]

- V. Chandgude et al., “Reducing agents assisted fed-batch fermentation to enhance ABE yields,” Energy Convers Manag, vol. 227, p. 113627, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Ding, H. Luo, F. Xie, H. Wang, M. Xu, and Z. Shi, “Electron receptor addition enhances butanol synthesis in ABE fermentation by Clostridium acetobutylicum,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 247, pp. 1201–1205, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cui, K.-L. Yang, and K. Zhou, “Using Co-Culture to Functionalize Clostridium Fermentation,” Trends Biotechnol, vol. 39, no. 9, pp. 914–926, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Cheng, T. Bao, and S.-T. Yang, “Engineering Clostridium for improved solvent production: recent progress and perspective,” Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, vol. 103, no. 14, pp. 5549–5566, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wen, M. Wu, Y. Lin, L. Yang, J. Lin, and P. Cen, “A novel strategy for sequential co-culture of Clostridium thermocellum and Clostridium beijerinckii to produce solvents from alkali extracted corn cobs,” Process Biochemistry, vol. 49, no. 11, pp. 1941–1949, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- C. L. Tri and I. Kamei, “Butanol production from cellulosic material by anaerobic co-culture of white-rot fungus Phlebia and bacterium Clostridium in consolidated bioprocessing,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 305, p. 123065, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Pinto, X. Flores-Alsina, K. V. Gernaey, and H. Junicke, “Alone or together? A review on pure and mixed microbial cultures for butanol production,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 147, p. 111244, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. G. Oliva-Rodríguez et al., “Clostridium strain selection for co-culture with Bacillus subtilis for butanol production from agave hydrolysates,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 275, pp. 410–415, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Mai et al., “Interactions between Bacillus cereus CGMCC 1.895 and Clostridium beijerinckii NCIMB 8052 in coculture for butanol production under nonanaerobic conditions,” Biotechnol Appl Biochem, vol. 64, no. 5, pp. 719–726, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- G. Qi et al., “Solvents production from cassava by co-culture of Clostridium acetobutylicum and Saccharomyces cerevisiae,” J Environ Chem Eng, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 128–133, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Ebrahimi, H. Amiri, M. A. Asadollahi, and S. A. Shojaosadati, “Efficient butanol production under aerobic conditions by coculture of Clostridium acetobutylicum and Nesterenkonia sp. strain F,” Biotechnol Bioeng, vol. 117, no. 2, pp. 392–405, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Ebrahimi, H. Amiri, and M. A. Asadollahi, “Enhanced aerobic conversion of starch to butanol by a symbiotic system of Clostridium acetobutylicum and Nesterenkonia,” Biochem Eng J, vol. 164, p. 107752, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Wushke, D. B. Levin, N. Cicek, and R. Sparling, “Facultative Anaerobe Caldibacillus debilis GB1: Characterization and Use in a Designed Aerotolerant, Cellulose-Degrading Coculture with Clostridium thermocellum,” Appl Environ Microbiol, vol. 81, no. 16, pp. 5567–5573, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhao, S. Liu, X. Han, Z. Zhou, and J. Mao, “Combined effects of fermentation temperature and Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains on free amino acids, flavor substances, and undesirable secondary metabolites in huangjiu fermentation,” Food Microbiol, vol. 108, p. 104091, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Barker, “Amino Acid Degradation by Anaerobic Bacteria,” Annu Rev Biochem, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 23–40, Jun. 1981. [CrossRef]

- J. Wu et al., “Developing a coculture for enhanced butanol production by Clostridium beijerinckii and Saccharomyces cerevisiae,” Bioresour Technol Rep, vol. 6, pp. 223–228, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Luo et al., “High-efficient n-butanol production by co-culturing Clostridium acetobutylicum and Saccharomyces cerevisiae integrated with butyrate fermentative supernatant addition,” World J Microbiol Biotechnol, vol. 33, no. 4, p. 76, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Behera, K. Konde, and S. Patil, “Methods for bio-butanol production and purification,” in Advances and Developments in Biobutanol Production, Elsevier, 2023, pp. 279–301. [CrossRef]

- J. G. Segovia-Hernández, S. Hernández, E. Sánchez-Ramírez, and J. Mendoza-Pedroza, “A Short Review of Dividing Wall Distillation Column as an Application of Process Intensification: Geographical Development and the Pioneering Contribution of Prof. Arturo Jimenez in Latin America,” Chemical Engineering and Processing - Process Intensification, vol. 160, p. 108275, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- I. Patraşcu, C. S. Bîldea, and A. A. Kiss, “Eco-efficient Downstream Processing of Biobutanol by Enhanced Process Intensification and Integration,” ACS Sustain Chem Eng, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 5452–5461, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Kongjan, N. Tohlang, S. Khaonuan, B. Cheirsilp, and R. Jariyaboon, “Characterization of the integrated gas stripping-condensation process for organic solvent removal from model acetone-butanol-ethanol aqueous solution,” Biochem Eng J, vol. 182, p. 108437, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- K.-M. Lu, Y.-S. Chiang, Y.-R. Wang, R.-Y. Chein, and S.-Y. Li, “Performance of fed-batch acetone–butanol–ethanol (ABE) fermentation coupled with the integrated in situ extraction-gas stripping process and the fractional condensation,” J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng, vol. 60, pp. 119–123, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. Cai et al., “Gas stripping–pervaporation hybrid process for energy-saving product recovery from acetone–butanol–ethanol (ABE) fermentation broth,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 287, pp. 1–10, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Wen et al., “Hybrid pervaporation and salting-out for effective acetone-butanol-ethanol separation from fermentation broth,” Bioresour Technol Rep, vol. 2, pp. 45–52, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Wen et al., “Integrated in situ gas stripping–salting-out process for high-titer acetone–butanol–ethanol production from sweet sorghum bagasse,” Biotechnol Biofuels, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 134, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Xue et al., “Characterization of gas stripping and its integration with acetone–butanol–ethanol fermentation for high-efficient butanol production and recovery,” Biochem Eng J, vol. 83, pp. 55–61, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- E. Rochón et al., “Bioprocess intensification for isopropanol, butanol and ethanol (IBE) production by fermentation from sugarcane and sweet sorghum juices through a gas stripping-pervaporation recovery process,” Fuel, vol. 281, p. 118593, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Chen et al., “Recovery of dilute aqueous butanol by membrane vapor extraction with dodecane or mesitylene,” J Memb Sci, vol. 528, pp. 103–111, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Callegari, S. Bolognesi, D. Cecconet, and A. G. Capodaglio, “Production technologies, current role, and future prospects of biofuels feedstocks: A state-of-the-art review,” Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol, vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 384–436, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- EPA, “Greenhouse Gas Emissions from a Typical Passenger Vehicle,” Green Vehicle Guide. [Online]. Available: https://www.epa.gov/greenvehicles/greenhouse-gas-emissions-typical-passenger-vehicle.

- M. J. Scully, G. A. Norris, T. M. Alarcon Falconi, and D. L. MacIntosh, “Carbon intensity of corn ethanol in the United States: state of the science,” Environmental Research Letters, vol. 16, no. 4, p. 043001, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Holmatov, J. F. Schyns, M. S. Krol, P. W. Gerbens-Leenes, and A. Y. Hoekstra, “Can crop residues provide fuel for future transport? Limited global residue bioethanol potentials and large associated land, water and carbon footprints,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 149, p. 111417, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Väisänen, J. Havukainen, V. Uusitalo, M. Havukainen, R. Soukka, and M. Luoranen, “Carbon footprint of biobutanol by ABE fermentation from corn and sugarcane,” Renew Energy, vol. 89, pp. 401–410, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Levasseur, O. Bahn, D. Beloin-Saint-Pierre, M. Marinova, and K. Vaillancourt, “Assessing butanol from integrated forest biorefinery: A combined techno-economic and life cycle approach,” Appl Energy, vol. 198, pp. 440–452, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. W. King and M. E. Webber, “The Water Intensity of the Plugged-In Automotive Economy,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 42, no. 12, pp. 4305–4311, Jun. 2008. [CrossRef]

- C. D. Scown, A. Horvath, and T. E. McKone, “Water Footprint of U.S. Transportation Fuels,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 45, no. 7, pp. 2541–2553, Apr. 2011. [CrossRef]

- G. Li, S. Ma, X. Xue, S. Yang, F. Liu, and Y. Zhang, “Life cycle water footprint analysis for second-generation biobutanol,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 333, p. 125203, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Li, N. Li, F. Liu, and X. Zhou, “Development of life cycle water footprint for lignocellulosic biomass to biobutanol via thermochemical method,” Renew Energy, vol. 198, pp. 222–227, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

| Properties | Petroleum- based | Oil-based | Bio-alcohols | ||||

| Gasoline | Diesel |

FAME (biodiesel) |

Bio-oil [35] |

Methanol | Ethanol | Butanol | |

| Molecular formula | C4 -C12 | C9 – C20 [36] | C6-C22 [37] | - | CH3OH | C2H5OH | C4H9OH |

| Molecular weight (g/gmol) | 95 - 120 | 190 -220 [38] | ≈295 [39] | - | 32 | 46 | 74 |

| Mass composition of C, H, O (%) | 86, 14, 0 | 86.8, 13.2, 0 [40] | 76.2, 12.6, 11.2 [40] | 54, 5, 34 | 37.5, 12.5, 50 | 52, 13, 35 | 65, 13.5, 21.5 |

| Heating Value (MJ/kg) | 44 – 46 | 43 [40] | 20.8 – 45.6 [41] | 16 - 20 | 22.7 [42] | 24.8[42] | 36.4 [43] |

| Boiling point(°C) | 200 | ≈ 163 -357 [36] | 340 – 375 [37] | - | 65 | 78 | 118 |

| Freezing point (°C) | -40 | -3 a -9 b [44] |

-25 to 26 a -28 to 18 b |

-10 to -20 b | -97 | -114 | -89 |

| Heat of vaporization (MJ/kg) | 0.36 | - | - | - | 1.20 | 0.92 | 0.43 |

| Energy density (MJ/L) | 32 | 36,3 [40] | 33,75 [40] | - | 16 | 19 | 30 |

| Density (Kg/m3) | 760 | 820 – 860 [45] | 860 -890 [45] | 1200 - 1300 | 796 | 790 | 810 |

| Air: fuel ratio | 15:1 | 14.5:1 [36] | 13:1 | - | 7:1 | 9:1 | 12 |

| Cetane number | - | 40 – 45 [40] | 45 – 55[40] | - | - | - | - |

| Motor octane number (MON) | 90 | - | - | - | 92 | 89 | 78 |

| Rating octane number (RON) | 95 | - | - | - | 106 | 107 | 96 |

| Flash point (°C) | -42 | 55 – 65 [41] | >150 [41] | 60 - 80 | 12 | 13 | 35 |

| Lubricity (µm) | - | 448 [44] | 351 – 567 [40] | - | 1100 | 1057 | 591 |

| Auto-ignition temperature (°C) | 257 | 210 | - | - | 463 | 423 | 397 |

| Fuel blending | Engine features | BTE | BSFC | CO | CO2 | HC | NOx | Source |

| N-Butanol 20% | Four cylinder SI engine. 1000-5000 RPM |

≈▼2% | ≈▲ 8% | ≈▼9,07% | ≈▲3,21% | ≈▼18,86% | ≈▼6,41% | [46] |

| Sec-butanol 20% | ≈▲2% | ≈▲15% | ≈▼8,87% | ≈▲5,17% | ≈▼17,67% | ≈▼20,26% | ||

| Tert-butanol 20% | ≈▲2% | ≈▲10% | ≈▼3,07% | ≈▲2,33% | ≈▼12,50% | ≈▼27,79% | ||

| Iso-butanol 20% | ≈▲4% | ≈▲11% | ≈▼14,54% | ≈▲15,53% | ≈▼18,80% | ≈▲43,55% | ||

| n-butanol 10% | Four cylinders turbocharged GDI engine. Urban conditions (throttle opening 10% and 35%), using GT-power simulations software. 1000-5000 RPM |

≈▲1,5% | - | ≈▼3% | - | ≈▲10 % | ≈▼1,5% | [47] |

| n-butanol 20% | ≈▲3,2% | - | ≈▼4% | - | ≈▲20 % | ≈▼2,1% | ||

| n-butanol 30% | ≈▲3,5% | - | ≈▼5% | - | ≈▲28 % | ≈▼3,9% | ||

| n-butanol 40% | ≈▲4,2% | - | ≈▼5% | - | ≈▲34 % | ≈▼4,5% | ||

| n-butanol 100% | ≈▲10,3% | - | ≈▼20% | - | ≈▲85% | ≈▼10% |

||

| Iso-butanol 10% | Single cylinder 2600 RPM. The wide-open throttle condition was investigated at three different compression ratios (CR): 9:1, 10:1, and 11:1. |

≈▲1% | ≈▲5% | ≈▼4% | ≈▲5% | ≈▼8% | - | [48] |

| Iso-butanol 30% | ≈▲2% | ≈▲11% | ≈▼13% | ≈▲12% | ≈▼25% | - | ||

| Iso-butanol 50% | ≈▲12% | ≈▲15% | ≈▼30% | ≈▲22,5% | ≈▼27% | - | ||

| n-butanol 10 % | 10 hp single cylinder 3000 RPM Uncoated |

≈▲2% | ≈▲1% | ≈▼5% | - | ≈▼10% | ≈▲5% | [49] |

| n-butanol 15% | ≈▲2% | ≈▲1,4% | ≈▼9% | - | ≈▼14% | ≈▲10% | ||

| n-butanol 10 % | 10 hp single cylinder 3000 RPM Ceramic coated |

≈▲5,6 | ≈▲1% | ≈▼4% | - | ≈▼12% | ≈▲2% | |

| n-butanol 15% | ≈▲5,6 | ≈▲1% | ≈▼7% | - | ≈▼19% | ≈▲10% | ||

| n-butanol 25% | Four stroke spark ignition engines, under operation conditions of variable engine speed (between 1250 and 3000 RPM). |

≈▲3,6% | ≈▼2% | ▼27,8% | ▼15,9% | ▼3,9% | [50] | |

| n-butanol 50% | ≈▲1,8% | ≈▲2,4 | ▼39,1% | - | ▼28% | ▼1,6% | ||

| n-butanol 2,5% | Four cylinders SI engine operating at different loads and speeds (3000- 5000 RPM). | - | ≈▼7,2% | ≈▼4,8% | - | ≈▼16% | ≈▼10,3% | [51] |

| n-butanol 5% | - | ≈▼ 1% | ≈▼7,8% | - | ≈▼25% | ≈▼3,9% | ||

| n-butanol 7,5% | - | ≈▲5% | ≈▼8% | - | ≈▼15% | ≈▲13,5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).