1. Introduction

The

P versus

problem is a fundamental question in computer science that asks whether problems whose solutions can be easily checked can also be easily solved [

1]. “Easily” here means solvable in polynomial time, where the computation time grows proportionally to the input size [

1,

2]. Problems solvable in polynomial time belong to the class

P, while

includes problems whose solutions can be verified efficiently given a suitable “certificate” [

2].

The central question is whether

P and

are the same. Most researchers believe that

P is a strict subset of

, meaning that some problems are inherently harder to solve than to verify. Resolving this problem has profound implications for fields like cryptography and artificial intelligence [

3,

4]. The

P versus

problem is widely considered one of the most challenging open questions in computer science. Techniques like relativization and natural proofs have yielded inconclusive results, suggesting the problem’s difficulty [

5,

6]. Similar problems, such as the

versus

problem in algebraic complexity, remain unsolved [

7].

Resolving the

P versus

problem is often described as a “holy grail” of computer science. A positive resolution could revolutionize our understanding of computation and potentially lead to groundbreaking algorithms for critical problems. The problem is listed among the Millennium Prize Problems. While recent years have seen progress in related areas, such as finding efficient solutions to specific instances of

-complete problems, the core question of

P versus

remains unanswered [

8]. A polynomial-time algorithm for any

-complete problem would directly imply

P equals

[

9]. Our work focuses on presenting such an algorithm for a well-known

-complete problem.

2. Background and Ancillary Results

-complete problems are the Everest of computational challenges. Despite the ease of verifying proposed solutions with a succinct certificate, finding these solutions efficiently remains an elusive goal. A problem is classified as -complete if it satisfies two stringent criteria within computational complexity theory:

Efficient Verifiability: Solutions can be quickly checked using a concise proof [

9].

Universal Hardness: Every problem in the class

can be reduced to this problem without significant computational overhead [

9].

The implications of finding an efficient algorithm for a single

-complete problem are profound. Such a breakthrough would serve as a master key, unlocking efficient solutions for all problems in

, with transformative consequences for fields like cryptography, artificial intelligence, and planning [

3,

4].

Illustrative examples of -complete problems include:

Boolean Satisfiability (SAT) Problem: Given a logical expression, determine if there exists an assignment of truth values to its variables that makes the entire expression true [

10].

Boolean 3-Satisfiability (3SAT) Problem: Given a Boolean formula in conjunctive normal form with exactly three literals per clause, determine if there exists a truth assignment to its variables that makes the formula evaluate to true [

10].

Exact k-Coloring Problem: Given a graph

G and a positive integer

k, determine if there exists a valid coloring of

G such that exactly

k vertices have the same color and no adjacent vertices have the same color. This problem is equivalent to finding an independent set of size

k, an

-complete problem [

11].

Partition into Triangles (PT) Problem: Given a graph

, where

V is the set of vertices and

E is the set of edges, the PT problem asks whether the vertices of

G can be partitioned into disjoint sets

, each containing exactly 3 vertices, such that each

induces a triangle in

G [

11]. In other words, we want to know if we can divide the graph into

q disjoint triangles.

The provided examples represent a small subset of the extensively studied -complete problems relevant to our current work. A bipartite graph, denoted as , is an undirected graph characterized by the existence of two node sets and edges in E that only connect nodes from opposite sets. An independent set is a subset of vertices in a graph G where no two vertices in the set are connected by an edge. In addition, a vertex cover (sometimes called a node cover) of a graph G is a subset of its vertices, denoted by , such that every edge in G has at least one endpoint in .

Definition 2.1. Exact Independent Vertex Cover (XIVC) Problem

INSTANCE: An undirected graph and a positive integer k.

QUESTION: Is there set of exactly k vertices such that is both a vertex cover and an independent set in G?

REMARKS: Solving the XIVC problem is akin to determining a 2-coloring of a bipartite graph such that one of the partitions contains exactly k vertices. This task can be accomplished in polynomial time, given the efficient solvability of the 2-coloring problem in bipartite graphs.

Formally, an instance of Boolean Satisfiability (SAT) Problem is a Boolean formula which is composed of:

Boolean variables: ;

Boolean connectives: Any Boolean function with one or two inputs and one output, such as ∧(AND), ∨(OR), ¬(NOT), ⇒(implication), ⇔(if and only if);

and parentheses.

A truth assignment for a Boolean formula

is a mapping from the variables of

to the Boolean values

. A truth assignment is satisfying if it makes

evaluate to true. A Boolean formula is satisfiable if it has at least one satisfying truth assignment. The SAT problem asks whether a given Boolean formula is satisfiable [

11].

A literal is a Boolean variable or its negation. A Boolean formula is in Conjunctive Normal Form (

) if it is a conjunction (AND) of clauses, where each clause is a disjunction (OR) of one or more literals [

9]. A

formula is a

formula in which each clause contains exactly two distinct literals [

9].

For example, the following formula is in

:

The first clause, , contains the two literals and . In addition, a formula is a Boolean formula in conjunctive normal form with exactly three literals per clause. We now introduce some well-known problems:

Definition 2.2. Monotone One-in-three 3-Satisfiability (1-IN-3-3MSAT) Problem

INSTANCE: Given a Boolean formula in with monotone clauses (meaning the variables are never negated)

QUESTION: Is there exists a satisfying truth assignment in which exactly one variable is true for each clause?

REMARKS: This problem is complete for [10].

Definition 2.3. Exact Monotone Xor 2-Satisfiability (XX2MSAT) Problem

INSTANCE: An n-variable formula with monotone clauses (meaning the variables are never negated) using logic operators ⊕ (instead of using the operator ∨) and a positive integer k.

QUESTION: Is there exists a satisfying truth assignment in which exactly k of the variables are true?

By presenting the -completeness and an efficient solution to SAT, we would establish a proof that P equals .

3. Main Result

Even though the following reductions are widely known, we will rely on them as supporting results in our analysis [

11].

Theorem 3.1. The problem SAT can be reduced to 3SAT in polynomial time.

Proof. We will not delve into the specific steps of this reduction, as it is a standard technique in computer science [

9]. To reduce a general SAT formula to a 3SAT formula, we can follow these steps:

-

Converting a Logic Expression to Clause Form: To convert a logic expression into clause form (), we need to transform it into a conjunction of clauses, where each clause is a disjunction of literals. Here’s a general approach:

- (a)

Eliminate Implications: Replace implications with equivalent disjunctions using the rule: is equivalent to .

- (b)

Push Negations Inward: Use De Morgan’s laws to move negations inward, so they apply directly to individual variables. For example, becomes .

- (c)

Convert to Conjunctive Normal Form: Use the distributive law to distribute disjunctions over conjunctions. This may involve introducing new variables to represent intermediate expressions.

- (d)

Standardize Variables: Ensure that each variable appears with a unique name throughout the formula.

- (e)

Clause Form: The resulting expression will be in , where each clause is a disjunction of literals.

Identify Long Clauses: Find all clauses with more than three literals.

Introduce New Variables: For a clause with n literals (where ), introduce new variables.

Create New Clauses: Create a chain of clauses with three literals each, using the original literals and the new variables. Ensure that the satisfiability of the original clause is preserved in this chain of new clauses.

By systematically applying this reduction to each long clause, we can transform any SAT formula into an equivalent 3SAT formula. This reduction demonstrates that 3SAT is at least as hard as the general SAT problem, and thus, it is an NP-complete problem. □

Theorem 3.2. The problem 3SAT can be reduced to 1-IN-3-3MSAT in polynomial time.

Proof. It is well-known that any Boolean formula in 3SAT can be reduced to an equivalent 1-IN-3-3MSAT instance. This reduction involves the following steps:

-

Variable Introduction:

Literal Variables: For each variable x in , introduce two variables: representing the positive literal x and representing the negative literal . Additionally, we introduce three new variables , , and for each variable x in .

Clause Variables: For each clause in , introduce four new variables: , , , and .

-

Clause Construction:

-

Clause Reduction: For each clause , construct three 1-IN-3-3MSAT clauses:

- -

, where if x is positive and otherwise.

- -

, where if y is positive and otherwise.

- -

, where if z is positive and otherwise.

-

Variable Consistency: For each variable x in , construct three 1-IN-3-3MSAT clauses:

- -

, , and . These clauses ensure that exactly one of and is true.

By construction, a satisfying truth assignment for corresponds to an appropriate satisfying truth assignment for the 1-IN-3-3MSAT instance, and vice versa. Thus, this reduction proves that 1-IN-3-3MSAT is -complete. □

Theorem 3.3. The problem 1-IN-3-3MSAT can be reduced to PT in polynomial time.

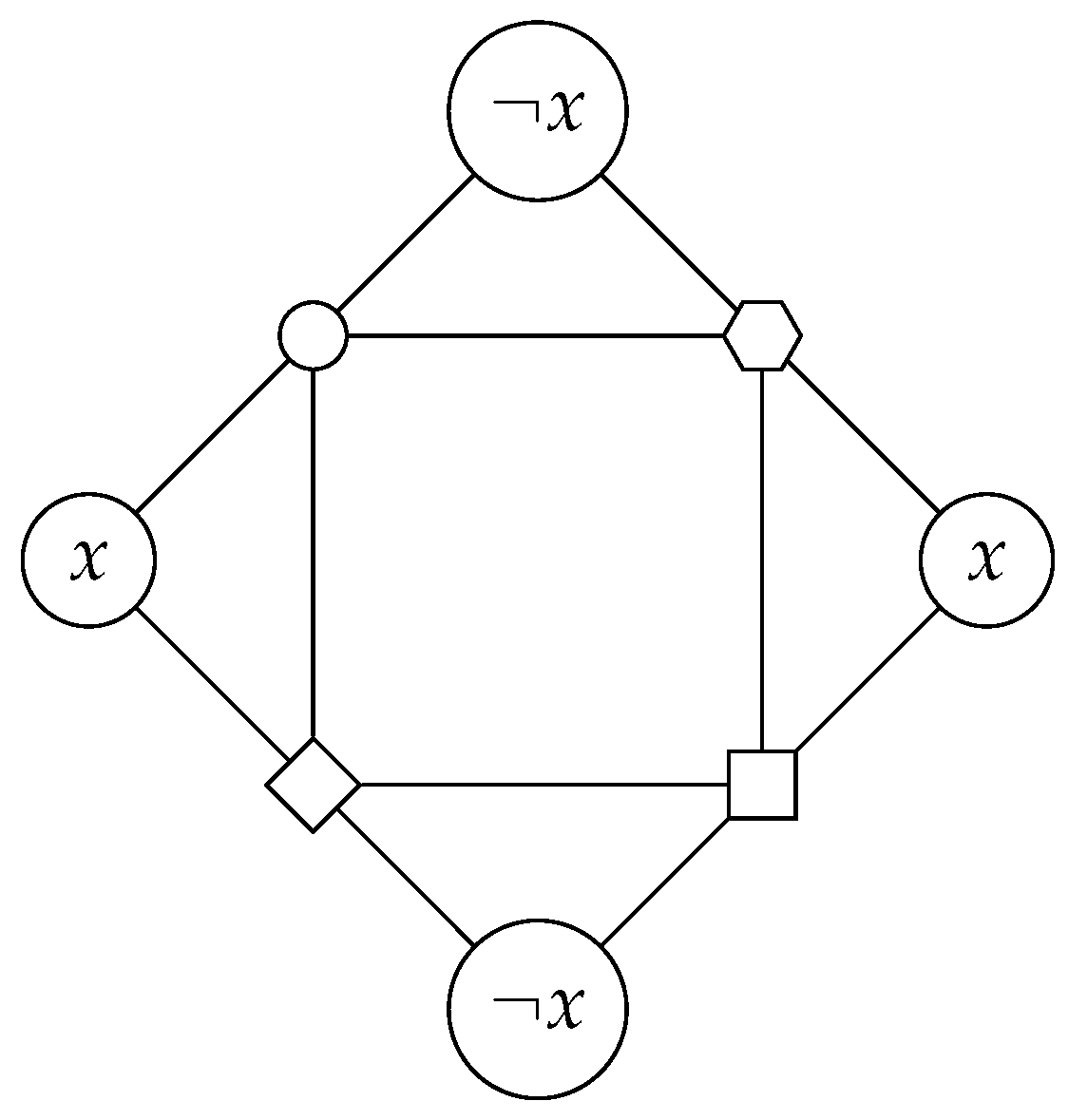

Proof. To represent a 1-IN-3-3MSAT formula

as an undirected graph

, we introduce a gadget for each variable

x in

. This gadget consists of

triangles, where

k is the larger of the number of occurrences of

x in

. Each triangle in the gadget corresponds to a possible truth assignment for the variable

x. The tips of the triangles are labeled with

x or

to indicate the corresponding truth assignment.

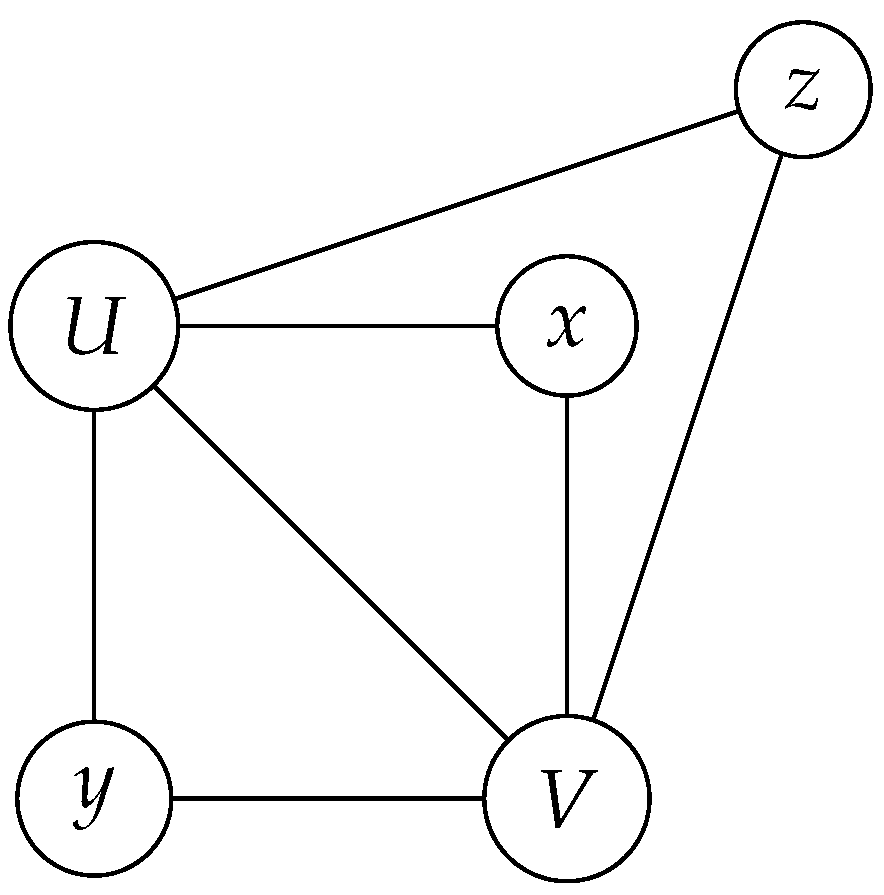

To represent each clause

in

, we introduce three new vertices:

U,

V, and

W. We connect

U and

V to the positive literals of

c in the graph. As

Figure 2 shows, exactly one positive literal from

c, along with

U and

V, must form a triangle. This ensures that exactly one of the positive literals in

c is true, thereby satisfying the 1-IN-3-3MSAT requirement.

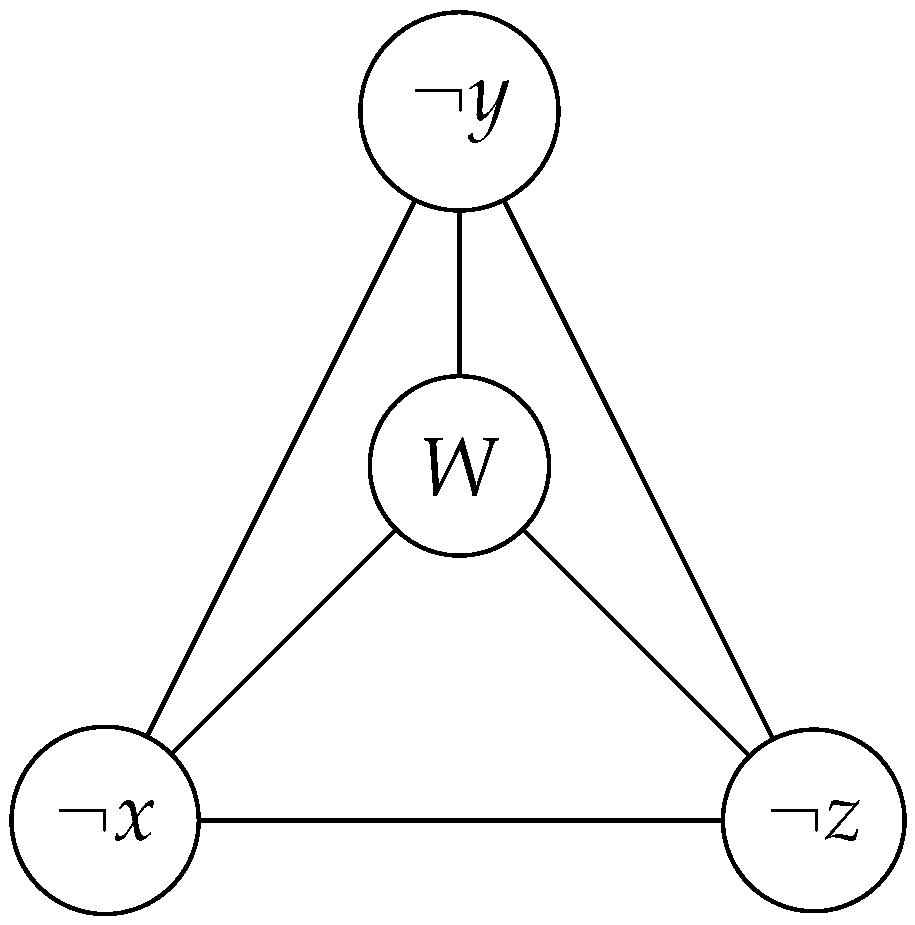

We then connect the negative literals to the logical constraints that involve their corresponding positive literals. As depicted in

Figure 3, this design ensures that exactly two negative literals will be part of triangles if only one positive literal in the clause is chosen. This condition is necessary to satisfy the 1-IN-3-3MSAT requirement.

The topology of the gadget ensures consistency. The construction (e.g.,

Figure 1) guarantees that if any

x vertex is matched with some vertices outside of the this gadget then all

x vertex can only be matched by the triangles inside this gadget, and vice versa. Thus the “availability” of a vertex to be matched by an outside vertex corresponds to the truth assignment.

A Boolean formula satisfies the 1-IN-3-3MSAT requirement if and only if its corresponding graph G can be partitioned into exactly disjoint triangles, where m is the number of clauses in . This equivalence is evident from the construction of G, which faithfully captures the logical structure of .

The graph G incorporates two types of triangles:

Variable Triangles: For each occurrence of a variable in , the variable gadget introduces a triangle. Since each clause contains the occurrence of three distinct variables, there are exactly such triangles.

Clause Triangles: For each clause in

, the construction described in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 introduces two triangles if and only if exactly one variable in the clause is true. This ensures that there are exactly

clause triangles in a satisfying truth assignment according to the 1-IN-3-3MSAT requirement.

Therefore, an appropriate satisfying truth assignment for directly corresponds to a partition of G into disjoint triangles: variable triangles and clause triangles. Conversely, any such partition of G can be interpreted as an appropriate satisfying truth assignment for . This one-to-one correspondence establishes the equivalence between the appropriate satisfiability of and the existence of a -triangle partition in G.

Obviously PT problem is in , and it is also -hard because 1-IN-3-3MSAT can be reduced to PT. So PT is -complete. □

This is a main insight.

Theorem 3.4. The problem PT can be reduced to XX2MSAT in polynomial time.

Proof. We can build an equivalent XX2MSAT instance for any given instance of the PT problem:

-

Variables:

Create a variable for each vertex v in the original graph G. Denote this variable as v itself.

For each pair of disconnected vertices u and v in G (i.e., ), introduce a new variable denoted by .

-

Clauses:

-

For every two disconnected vertices (i.e., ), construct two clauses using the new variables:

- -

: This enforces that either u is true or the new variable is true (XOR).

- -

: This enforces that either the new variable is true or v is true (XOR).

Key Points about the Construction:

The two clauses for each pair of disconnected vertices u and v in G ensures that both variables u and v have the same truth value.

Moreover, the two clauses together imply that is true exactly when both u and v are false. This means that for any pair of vertices u and v that are not directly connected in the graph, at least one of the three variables u, v, or must be assigned the value true.

Mapping between PT solutions and XX2MSAT assignments:

Why this construction works:

The clauses guarantee that, in a satisfying truth assignment, the original variables (representing vertices) and the corresponding new variables must have compatible truth values.

If a graph can be partitioned into q triangles, then there exists a corresponding truth assignment where the original variables (representing vertices) are false and the single new variable is true for each pair of disconnected vertices u and v.

Equivalence and Complexity:

A q-triangle partition of G can be mapped to a satisfying truth assignment of the XX2MSAT formula with exactly true variables, and vice versa.

If we partition the graph into q disjoint sets, each vertex in a set will be disconnected from vertices that belong to the sets . By summing the number of disconnected pairs for all vertices in all sets, we arrive at a total of disconnected pairs due to . For any pair of disconnected vertices u and v, the variable is assigned the value true if and only if both u and v are assigned the value false. As a result, there will be a total of true variables in the satisfying truth assignment, since all the original variables corresponding to vertices are set to false. It’s important to note that a satisfying truth assignment with exactly true variables directly corresponds to a partition of the graph G into q triangles.

Given that PT is an -complete problem and we have demonstrated a polynomial-time reduction from PT to XX2MSAT, we can conclude that XX2MSAT is also -complete.

In essence, the proof demonstrates that solving XX2MSAT is equivalent to finding a q-triangle partition in the PT problem. This implies that XX2MSAT inherits the -completeness property from PT. □

These are the main theorems.

Theorem 3.5. .

Proof. Given the efficient solvability of the 2-coloring problem in bipartite graphs, we claim that the XIVC problem can be accomplished within polynomial time. This is a straightforward dynamic programming algorithm similar to solve subset sum: Let be the sides of partitions and in a connected component i of the bipartite graph , such that every vertex in a single partition has the same color.

Now, we create a dynamic programming table

that stores whether it is possible to have a bipartite graph with exactly

t vertices on one color using the

i first components. The bi-dimensional array

of dimensions

by

(i.e., using zero-based indexing) is initialized such that all elements are

, with the exception of

which is set to

(i.e., assuming that array indices start from zero). Using the recurrence

we correctly decide whether there exists an entire partitioning of exactly

k vertices with the same color after by examining

. The recurrence evaluates

as false for any

i and

t that do not satisfy

and

. This is a polynomial time algorithm since the running time is bounded by

. Identifying 2-color partitions takes

time using breadth-first search algorithm (BFS), while finding

k vertices of the same color requires

iterations. We can easily determine if a graph is two-colorable by performing a breadth-first search and assigning alternating colors to the nodes. Similarly, the subset sum problem (in this specific variation) can be solved by systematically checking all possible values from 0 to

k using each pair of partitions for every connected component. □

Proof. There is a connection between finding a satisfying truth assignment in XX2MSAT with exactly k true variables and finding a set of exactly k vertices that is both a vertex cover and an independent set in a specific graph construction.

Here’s a breakdown of the equivalence:

-

Graph Construction:

Each vertex in the new graph represents a variable in the XX2MSAT formula.

Edges are created between variables based on the structure of the clauses: If two variables appear in a clause (e.g., ), then an edge is drawn between the corresponding vertices in the graph.

-

XX2MSAT and the Graph:

A truth assignment in XX2MSAT where exactly k variables are true directly translates to a set of exactly k vertices in the constructed graph where true variables correspond to the vertices included in the set.

-

The properties of XX2MSAT clauses ensure that:

- -

Vertex Cover: The chosen vertices cover all the edges (due to the structure of the clauses and the way edges are formed). This satisfies the vertex cover condition.

- -

Independent Set: The chosen vertices don’t have any edges connecting them (because the variables are connected in the graph, and only one variable from each clause can be true). This satisfies the independent set condition.

Therefore, finding a satisfying truth assignment with exactly k true variables in XX2MSAT is indeed equivalent to finding a set of exactly k vertices that fulfills both vertex cover and independent set requirements in the corresponding graph. However, we know the problem of finding a set of exactly k vertices that is both a vertex cover and an independent set can be solved in polynomial time. Consequently, the instances of the problem XX2MSAT can be solved in polynomial time as well. □

This is a key finding.

Proof. A polynomial-time solution to any

-complete problem would establish the equivalence of

P and

[

9]. Given that SAT is an

-complete problem, a polynomial-time solution for it, as presented here, would directly imply

P equals

. □

4. Conclusion

A definitive proof that P equals would fundamentally reshape our computational landscape. The implications of such a discovery are profound and far-reaching:

In conclusion, a proof of would usher in a new era of computational power with transformative effects on science, technology, and society. While challenges and uncertainties exist, the potential benefits are immense, making this a compelling area of continued research.

References

- Cook, S.A. The P versus NP Problem, Clay Mathematics Institute. https://www.claymath.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/pvsnp.pdf, 2022. Accessed September 26, 2024.

- Sudan, M. The P vs. NP problem. http://people.csail.mit.edu/madhu/papers/2010/pnp.pdf, 2010. Accessed September 26, 2024.

- Fortnow, L. The status of the P versus NP problem. Communications of the ACM 2009, 52, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, S. P=?NP. Open Problems in Mathematics, 2016; 1–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.; Gill, J.; Solovay, R. Relativizations of the P=? NP Question. SIAM Journal on computing 1975, 4, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razborov, A.A.; Rudich, S. Natural Proofs. Journal of Computer and System Sciences 1997, 1, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigderson, A. Mathematics and Computation: A Theory Revolutionizing Technology and Science; Princeton University Press, 2019.

- Fortnow, L. Fifty Years of P vs. NP and the Possibility of the Impossible. Communications of the ACM 2022, 65, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormen, T.H.; Leiserson, C.E.; Rivest, R.L.; Stein, C. Introduction to Algorithms, 3rd ed.; The MIT Press, 2009.

- Schaefer, T.J. The complexity of satisfiability problems. Proceedings of the tenth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing, 1978, pp. 216–226. [CrossRef]

- Garey, M.R.; Johnson, D.S. Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness, 1 ed.; San Francisco: W. H. Freeman and Company, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Vega, F. Note for the P versus NP Problem. IPI Letters 2024, 2, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).