Submitted:

23 September 2024

Posted:

24 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling Procedure

2.2.1. Monthly and Seasonally Samplings

2.2.2. Experimental Sampling

2.2.3. Macroscopical Examination of Ovaries

2.2.4. Ovarian Histological Analysis

2.2.5. Fecundity

2.2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

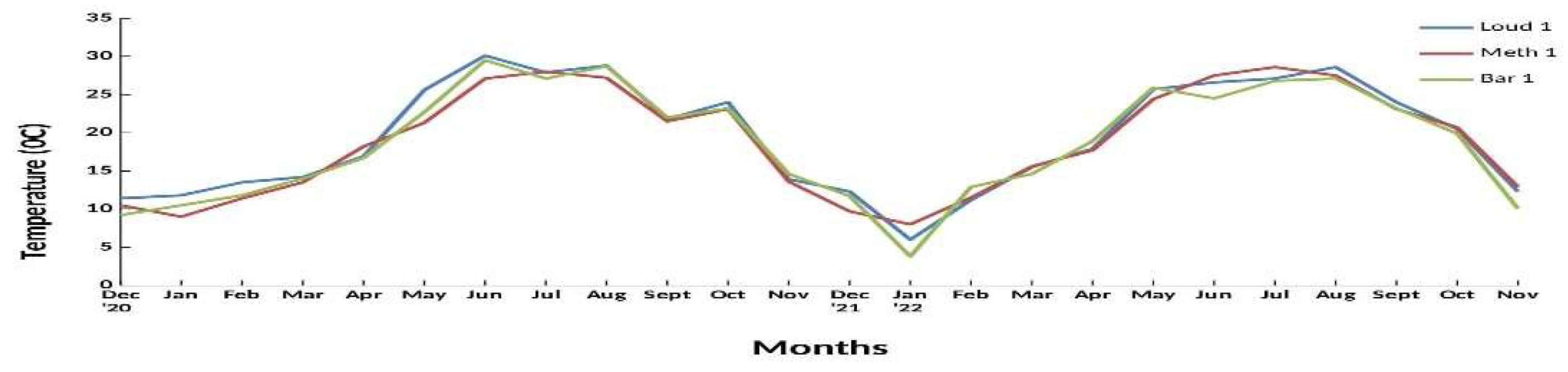

3.1. Physicochemical Parameters

3.1.1. Temperature

3.1.2. Salinity

3.1.3. Oxygen

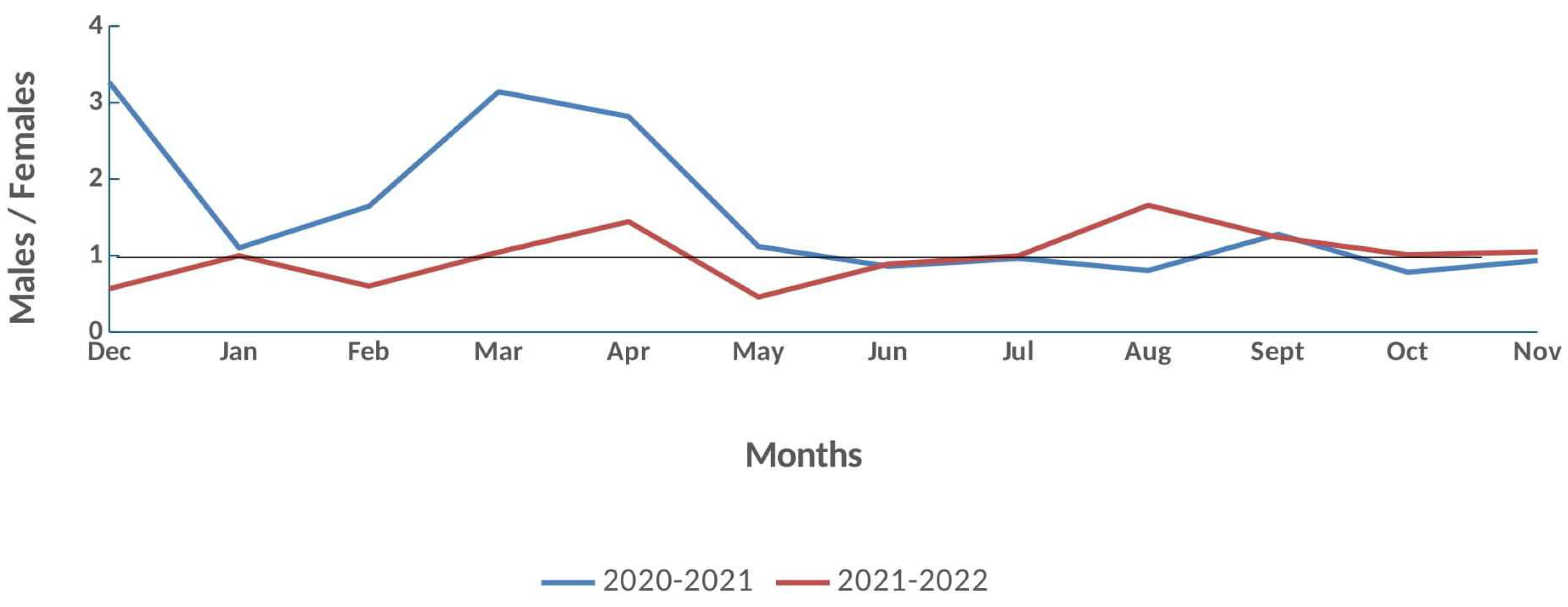

3.2. Sex Ratio

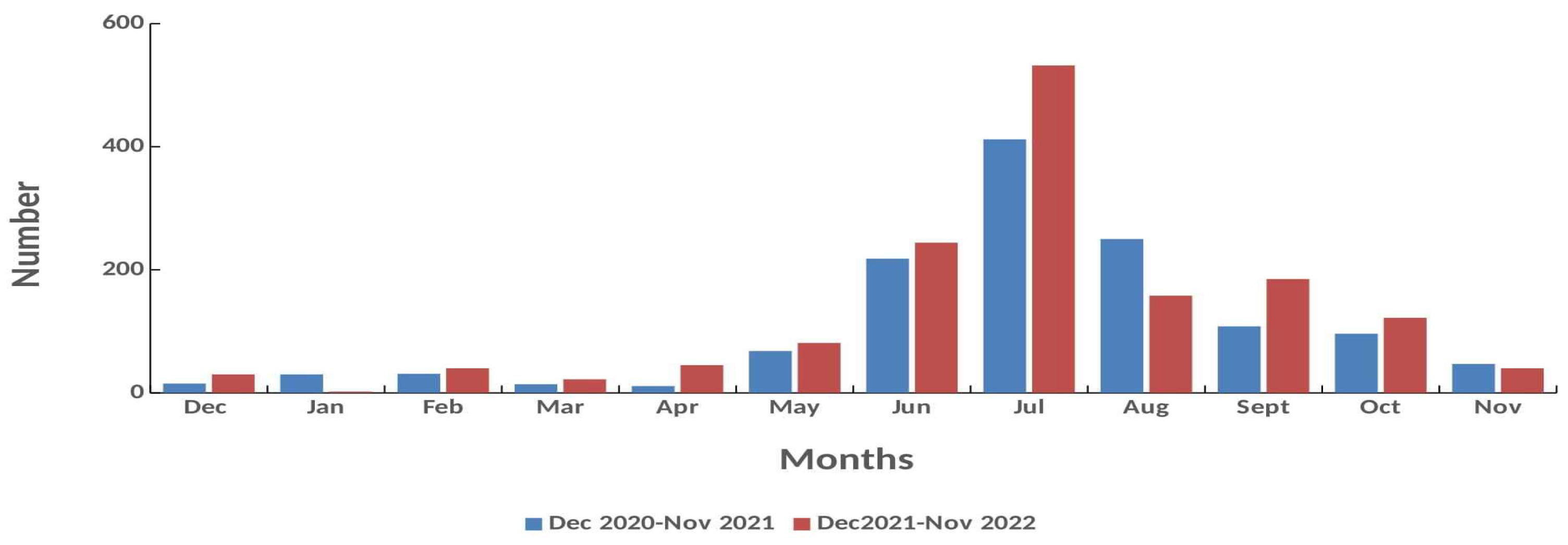

3.3. Females Monthly Distribution

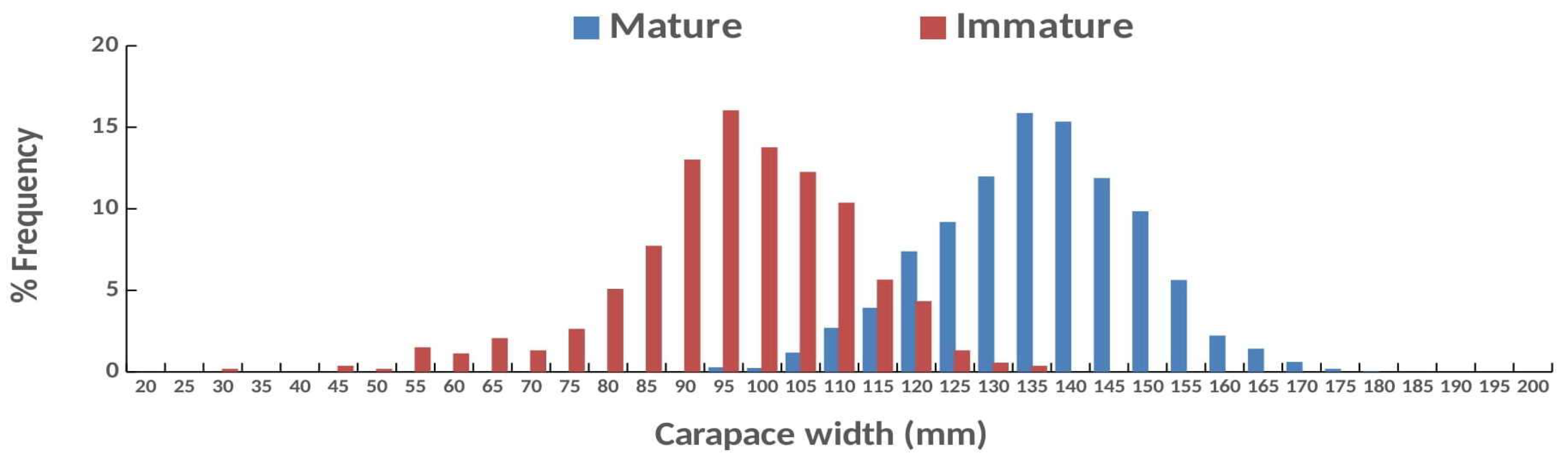

3.4. Females Size (CW) Frequency Distribution

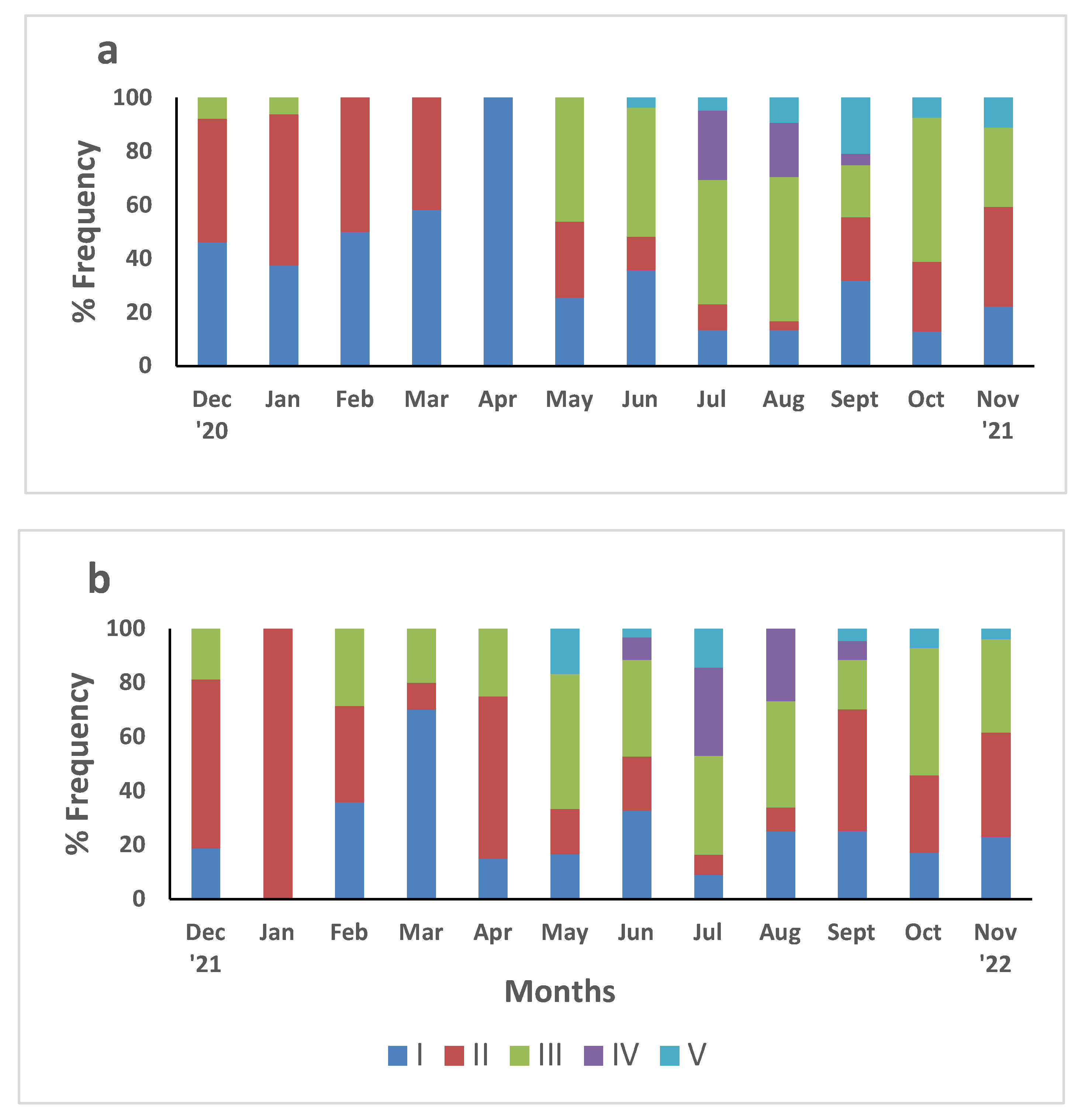

3.5. Ovarian Stages

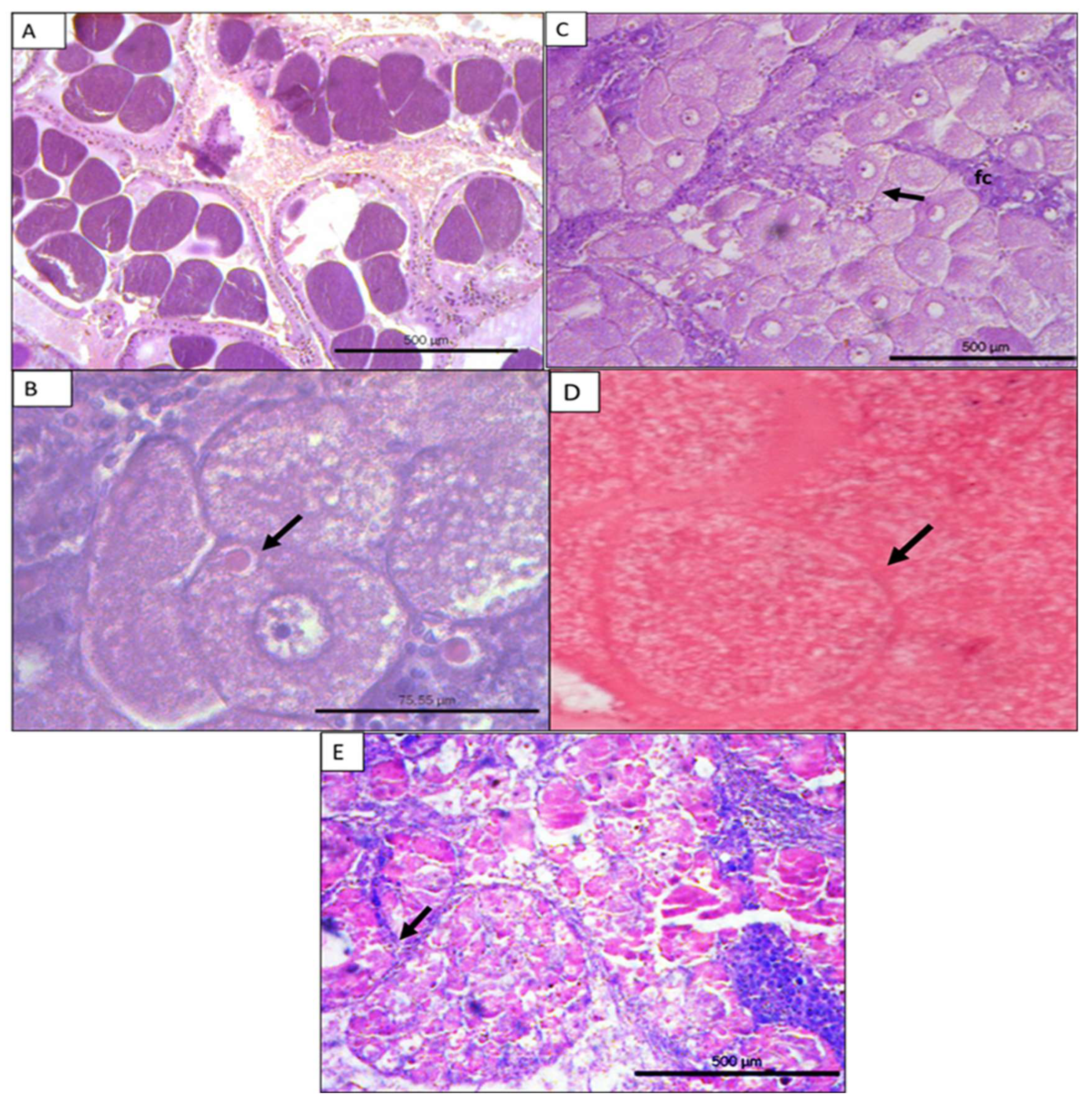

3.5.1. Gross Appearance of Ovaries

3.5.2. Histological Analysis of Ovarian Stages

3.6. Size (Carapace Width) - Ovarian Weight

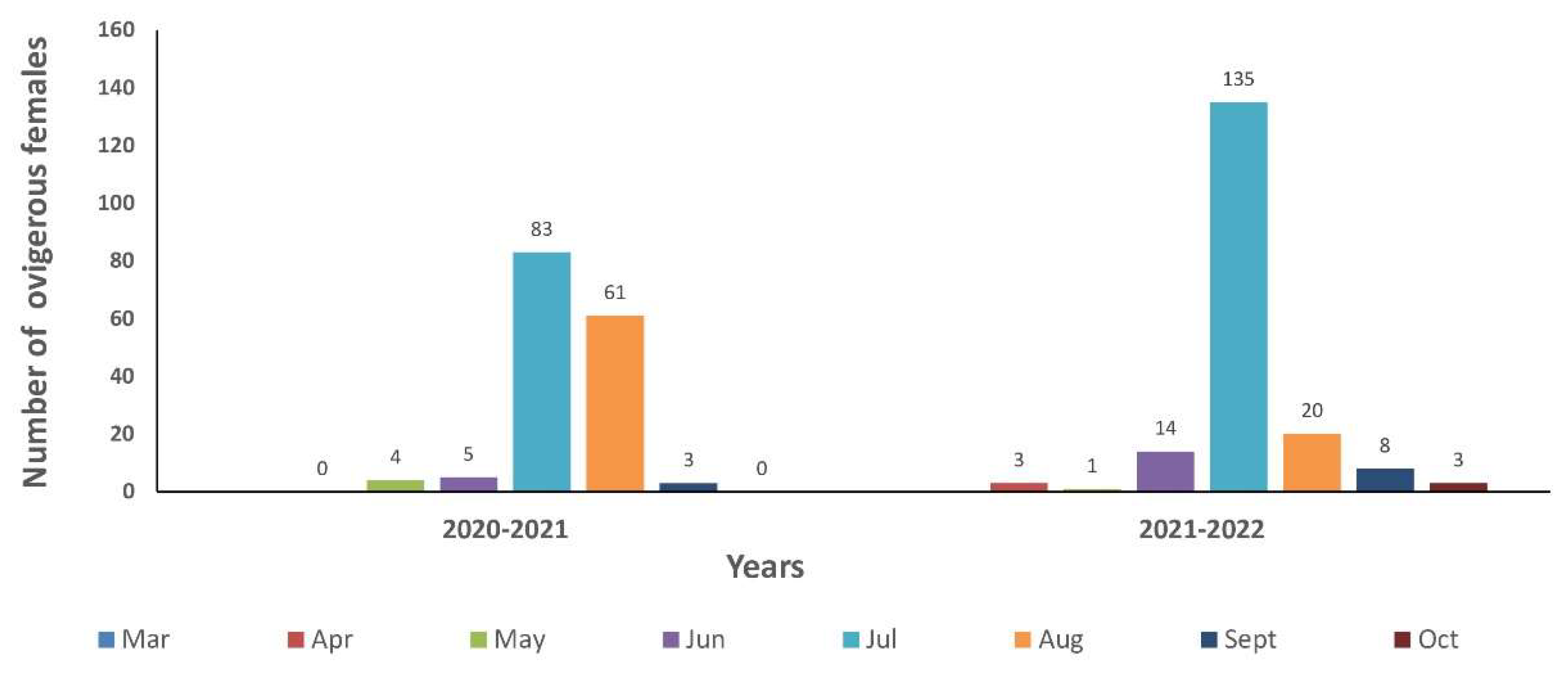

3.7. Ovigerous Females

3.7.1. Temperature – Ovigerous Females

3.7.2. Monthly Distribution of Ovigerous Females and Ovigerous Females with Eggs at Developmental Stage 5

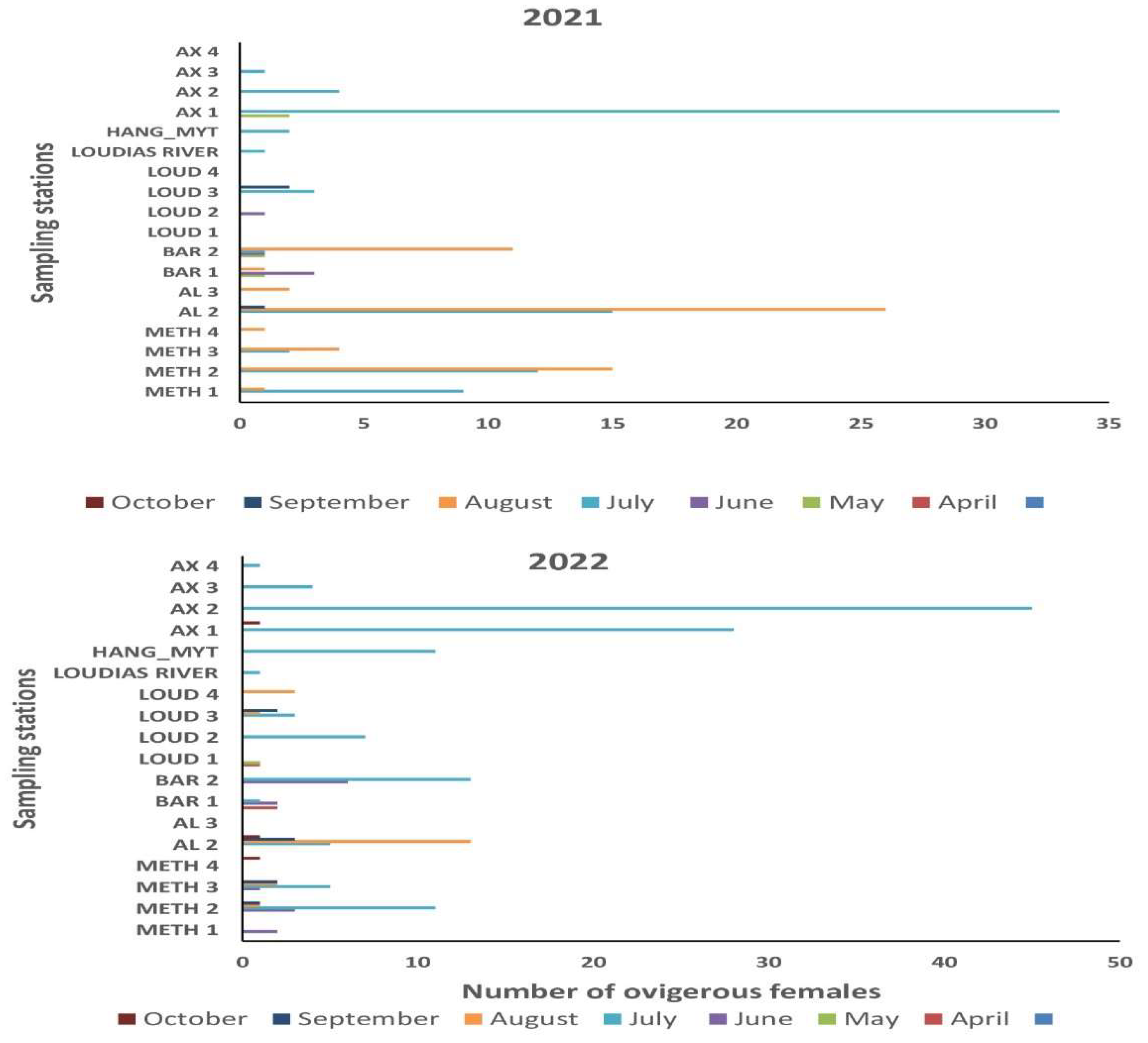

3.7.3. Spatial Distribution of Ovigerous Females and Ovigerous Females with Eggs at Developmental Stage 5

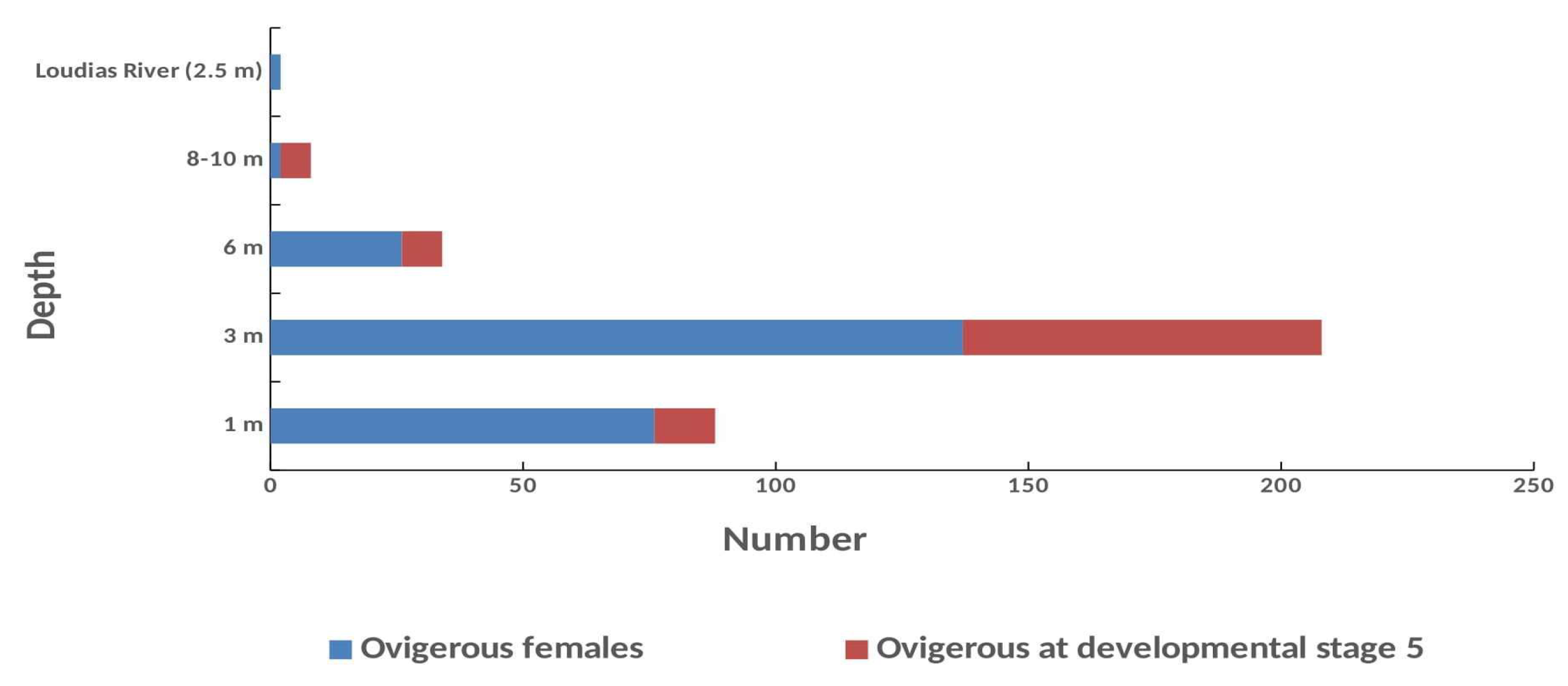

3.7.4. Bathymetrical Distribution of Ovigerous Females and Ovigerous Females with Eggs at Developmental Stage 5

3.7.5. Size of Ovigerous Females and Ovigerous Females with Eggs at Developmental Stage 5

3.7.6. Size of Ovigerous Females and Ovigerous Females with Eggs at Developmental Stage 5 with Depth Gradient

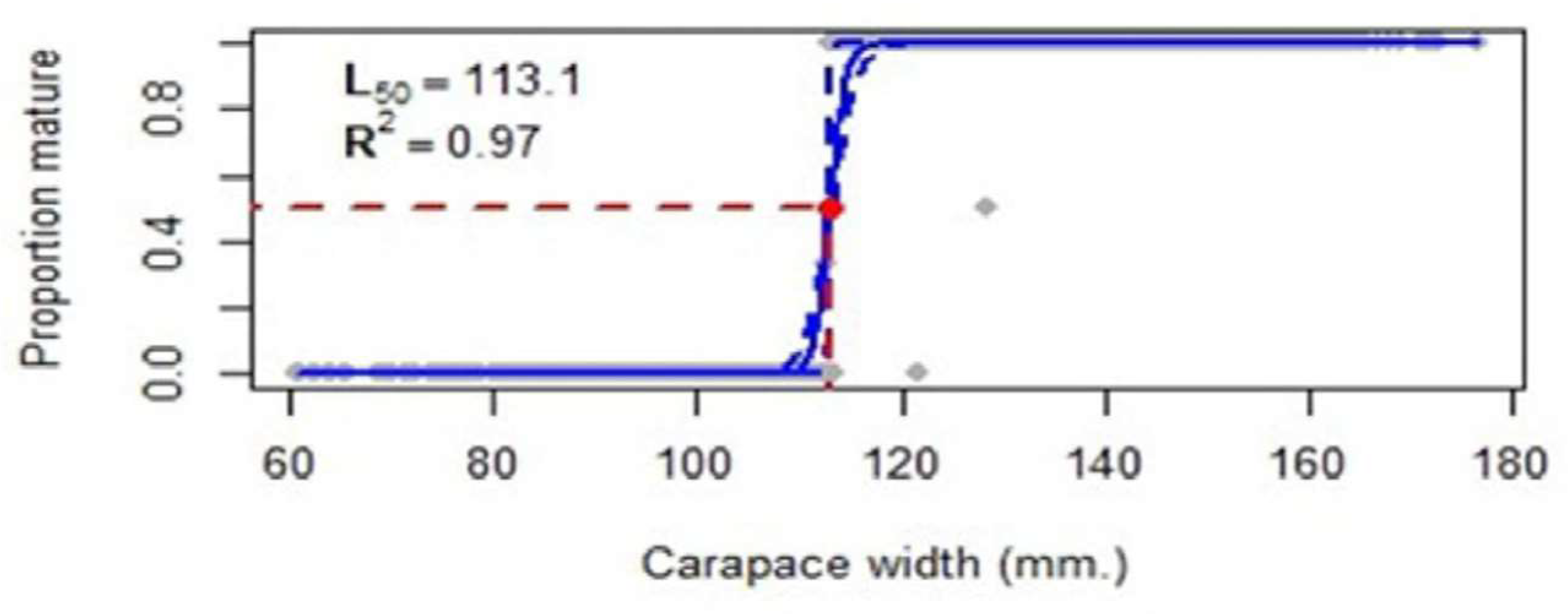

4. Size (CW50) at First Maturity

5. Experimental Sampling

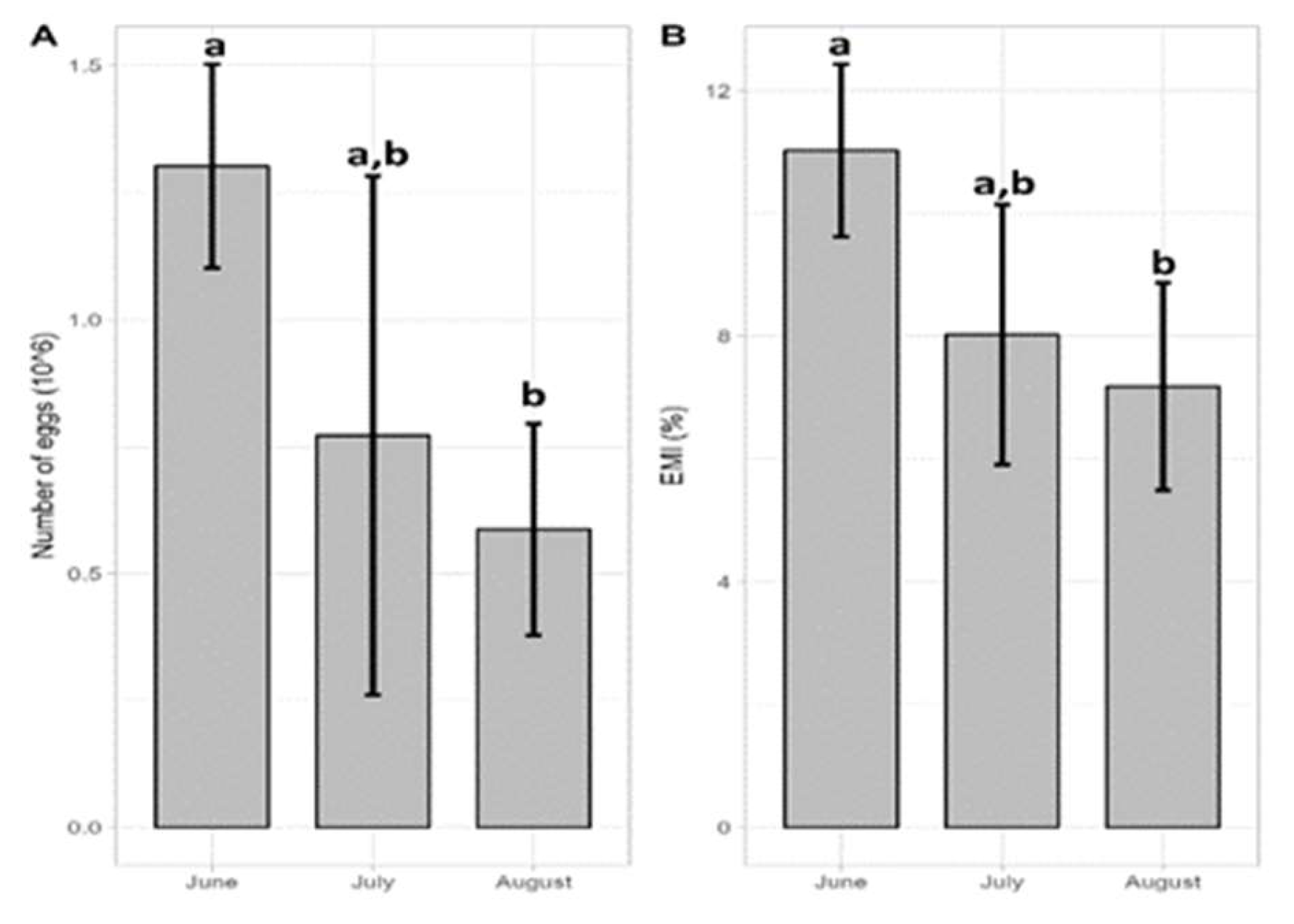

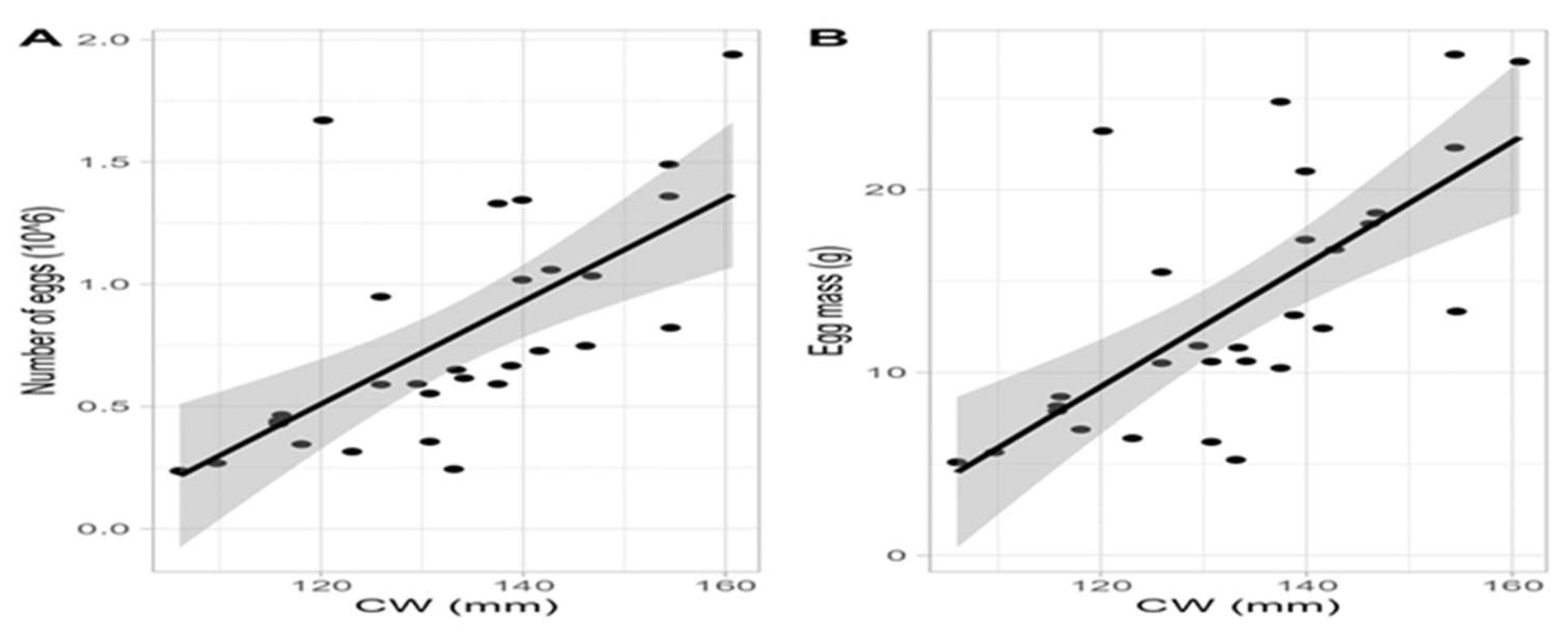

6. Fecundity

7. Discussion

Sex Ratio and Mating

Size at First Maturity

Ovarian Development

Ovigerous Females

Fecundity

Management Implications

References

- Thongda, W.; Chung, J.S.; Tsutsui, N.; Zmora, N.; Katenta, A. Seasonal Variations in Reproductive Activity of the Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus: Vitellogenin Expression and Levels of Vitellogenin in the Hemolymph during Ovarian Development. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 2015, 179, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, A.B. THE SWIMMING CRABS OF THE GENUS CALLINECTES (DECAPODA: PORTUNIDAE). Fishery Bulletin 1974, 72, 685–798. [Google Scholar]

- Millikin, M.R. Synopsis of Biological Data on the Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.S. The Savory Swimmer Swims North: A Northern Range Extension of the Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus? Journal of Crustacean Biology 2015, 35, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancinelli, G.; Bardelli, R.; Zenetos, A. A Global Occurrence Database of the Atlantic Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus. Sci Data 2021, 8, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouvier, E.L. Sur Un Callinectes Sapidus M. Rathbun Trouvé à Rochefort. Bull. Mus. Hist. Nat. 1901, 7, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Giordani, S. Neptunus Pelagicus (L.) Nell’Alto Adriatico (Neptunus Pelagicus in the Northern Adriatic). Natura 1951, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Serbetis, C. Un Nouveau Crustacé Comestible En Mer Egée Callinectes Sapidus Rathb. (Décapode Brachyoure). Proc. Gen. Fish. Comm. Mediterran. 1959, 5, 505–507. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiadis, C.; Georgiadis, G. Zur Kenntnis Der Crustacea Decapoda Des Golfes von Thessaloniki. Crustaceana 1974, 26, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedl, R. Fauna Und Flora Des Mittelmeeres. Internationale Revue der gesamten Hydrobiologie und Hydrographie 1985, 70, 442–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehring, S. Invasion History and Success of the American Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus in European and Adjacent Waters. In the Wrong Place - Alien Marine Crustaceans: Distribution, Biology and Impacts; Galil, B.S., Clark, P.F., Carlton, J.T., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; ISBN 978-94-007-0591-3. [Google Scholar]

- Holthuis, L.B.; Gottlieb, E. The Occurrence of the American Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun, in Israel Waters. Bull. Res. Counc. of Israel. 1955, 5, 154–156. [Google Scholar]

- Holthuis, L. Report on a Collection of Crustacea Decapoda and Stomatopoda from Turkey and the Balkans. Zoologische Verhandelingen 1961, 47, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Banoub, M.W. Survey of the Blue-Crab Callinectus Sapidus (Rath.), in Lake Edku in 1960. Alex. Institute. of Hydrobiology Egypt 1963, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kevrekidis, K.; Antoniadou, C. Abundance and Population Structure of the Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus (Decapoda, Portunidae) in Thermaikos Gulf (Methoni Bay), Northern Aegean Sea. Crustaceana 2018, 69, 641–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevrekidis, K.; Kevrekidis, T.; Mogias, A.; Boubonari, T.; Kantaridou, F.; Kaisari, N.; Malea, P.; Dounas, C.; Thessalou-Legaki, M. Fisheries Biology and Basic Life-Cycle Characteristics of the Invasive Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun in the Estuarine Area of the Evros River (Northeast Aegean Sea, Eastern Mediterranean). Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2023, 11, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, Sh.E.; Dowidar, N.M. Brachyura (Decapoda Crustacea) from the Mediterranean Waters of Egypt. Thalassia Jugoslavica 1972, 8, 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel Razek, F.A.; Ismaiel, M.; Ameran, M.A.A. Occurrence of the Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus, Rathbun, 1896, and Its Fisheries Biology in Bardawil Lagoon, Sinai Peninsula, Egypt. The Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Research 2016, 42, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgurkov, K.I. Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun in the Black Sea. Izvest. Niors. 1968, 9, 97–99. [Google Scholar]

- ENZENRO§, R.; ENZENRO§, L.; BİNGEL, F. Occurrence of Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus (RATHBUN, 1896) (Crustacea, Brachyura) on the Turkish Mediterranean and the Adjacent Aegean Coast and Its Size Distribution in the Bay of Iskenderun. Turkish Journal of Zoology 1997, 21, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türeli, C.; Miller, T.J.; Gündoğdu, S.; Yeşilyurt, İ.N. Growth and Mortality of Blue Crab (Callinectes Sapidus) in the North-Eastern Mediterranean Sea. Journal of FisheriesSciences.com 2016, 10, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- F. Mehanna, S.; G. Desouky, M.; E. Farouk, A. Population Dynamics and Fisheries Characteristics of the Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus (Rathbun, 1896) as an Invasive Species in Bardawil Lagoon, Egypt. Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology and Fisheries 2019, 23, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdikaris, C.; Konstantinidis, E.; Gouva, E.; Ergolavou, A.; Klaoudatos, D.; Nathanailides, C.; Paschos, I. Occurrence of the Invasive Crab Species Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun, 1896, in NW Greece. Walailak Journal of Science and Technology (WJST) 2016, 13, 503–510. [Google Scholar]

- Kevrekidis, K. Callinectes Sapidus (Decapoda, Brachyura): An Allochthonous Species in Thermaikos Gulf. Fish. News 2010, 340, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Castriota, L.; Falautano, M.; Perzia, P. When Nature Requires a Resource to Be Used—The Case of Callinectes Sapidus: Distribution, Aggregation Patterns, and Spatial Structure in Northwest Europe, the Mediterranean Sea, and Adjacent Waters. Biology 2024, 13, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaouti, A.; Belattmania, Z.; Nadri, A.; Serrão, E.; Encarnação, J.; Teodósio, A.; Reani, A.; Sabour, B. The Invasive Atlantic Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun, 1896 Expands Its Distributional Range Southward to Atlantic African Shores: First Records along the Atlantic Coast of Morocco. BIR 2022, 11, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, M.; Karadurmuş, U.; VEREP, B.; Gözler, A. Expansion of the Distribution Range and Size of the Invasive Blue Crab on the Turkish Coast of the Black Sea. Journal of Anatolian Environmental and Animal Sciences 2024, 9, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gómez, G.; García-Herrero, Á.; Sánchez, N.; Pardos, F.; Izquierdo-Muñoz, A.; Fontaneto, D.; Martínez, A. Meiofauna Is an Important, yet Often Overlooked, Component of Biodiversity in the Ecosystem Formed By. Invertebrate Biology 2022, 141, e12377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAAFisheries(2024). Available online: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/foss/f?p=215:200:11552239188158 (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Schneider, A.K.; Fabrizio, M.C.; Lipcius, R.N. Reproductive Potential of the Blue Crab Spawning Stock in Chesapeake Bay across Eras and Exploitation Rates Using Nemertean Worms as Biomarkers. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2023, 716, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, P.; Baeta, M.; Mestre, E.; Solis, M.A.; Sanahuja, I.; Gairin, I.; Camps-Castellà, J.; Falco, S.; Ballesteros, M. Trophic Role and Predatory Interactions between the Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus, and Native Species in Open Waters of the Ebro Delta. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifi, M.; Basti, L.; Rizzo, L.; Tanduo, V.; Radulovici, A.; Jaziri, S.; Uysal, İ.; Souissi, N.; Mekki, Z.; Crocetta, F. Tackling Bioinvasions in Commercially Exploitable Species through Interdisciplinary Approaches: A Case Study on Blue Crabs in Africa’s Mediterranean Coast (Bizerte Lagoon, Tunisia). Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2023, 291, 108419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancinelli, G.; Chainho, P.; Cilenti, L.; Falco, S.; Kapiris, K.; Katselis, G.; Ribeiro, F. The Atlantic Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus in Southern European Coastal Waters: Distribution, Impact and Prospective Invasion Management Strategies. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2017, 119, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glamuzina, L.; Conides, A.; Mancinelli, G.; Glamuzina, B. A Comparison of Traditional and Locally Novel Fishing Gear for the Exploitation of the Invasive Atlantic Blue Crab in the Eastern Adriatic Sea. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2021, 9, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öndes, F.; Gökçe, G. Distribution and Fishery of the Invasive Blue Crab (Callinectes Sapidus) in Turkey Based on Local Ecological Knowledge of Fishers. JAES 2021, 6, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chairi, H.; González-Ortegón, E. Additional Records of the Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun, 1896 in the Moroccan Sea, Africa. BIR 2022, 11, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, J.M. Biological Invasions. Current Biology 2008, 18, R57–R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavero, M.; Franch, N.; Bernardo-Madrid, R.; López, V.; Abelló, P.; Queral, J.M.; Mancinelli, G. Severe, Rapid and Widespread Impacts of an Atlantic Blue Crab Invasion. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2022, 176, 113479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thresher, R.E.; Kuris, A.M. Options for Managing Invasive Marine Species. Biological Invasions 2004, 6, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usseglio, P.; Selwyn, J.D.; Downey-Wall, A.M.; Hogan, J.D. Effectiveness of Removals of the Invasive Lionfish: How Many Dives Are Needed to Deplete a Reef? PeerJ 2017, 5, e3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giakoumi, S.; Katsanevakis, S.; Albano, P.G.; Azzurro, E.; Cardoso, A.C.; Cebrian, E.; Deidun, A.; Edelist, D.; Francour, P.; Jimenez, C.; et al. Management Priorities for Marine Invasive Species. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 688, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Engel, W.A. The Blue Crab and Its Fishery in Chesapeake Bay. Part 1. Reproduction, Early Development, Growth, and Migration. Commercial Fisheries Review 1958, 20, 6–17. [Google Scholar]

- Jivoff, P.R.; Hines, A.H.; Quackenbush, S. Chapter 7: Reproduction and Embryonic Development. In Blue Crab: Callinectes Sapidus. 2007, 181–223.

- Hines, A.H. Allometric Constraints and Variables of Reproductive Effort in Brachyuran Crabs. Mar. Biol. 1982, 69, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tankersley, R.A.; Wieber, M.G.; Sigala, M.A.; Kachurak, K.A. Migratory Behavior of Ovigerous Blue Crabs Callinectes Sapidus: Evidence for Selective Tidal-Stream Transport. The Biological Bulletin 1998, 195, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hines, A.H. Chapter 14: Ecology of Juvenile and Adult Blue Crabs. In Biology of the Blue Crab; Kenney, V.S., Cronin, E., Eds.; Maryland Sea Grant Program: College Park, MD, USA, 2007; pp. 575–665. [Google Scholar]

- Epifanio, C.E. Early Life History of the Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus: A Review. shre 2019, 38, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.K.; Shields, J.D.; Fabrizio, M.C.; Lipcius, R.N. Spawning History, Fecundity, and Potential Sperm Limitation of Female Blue Crabs in Chesapeake Bay. Fisheries Research 2024, 278, 107094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prager, M.; McConaugha, J.; Jones, C.; Geer, P. Fecundity of Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus, in Chesapeake Bay: Biological, Statistical and Management Considerations. Bulletin of Marine Science 1990, 46, 170–179. [Google Scholar]

- Hines, A.H.; Lipcius, R.N.; Haddon, A.M. Population Dynamics and Habitat Partitioning by Size, Sex, and Molt Stage of Blue Crabs Callinectes Sapidus in a Subestuary of Central Chesapeake Bay. Marine Ecology-Progress Series 1987, 36, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, P.; Bert, T.M. Population Ecology of the Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun. In A Subtropical Estuary: Population Structure, Aspects of Reproduction, and Habitat Partitioning; Florida Marine Research Institute Publication: St. Petersburg, FL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Türeli, C.; Yeşilyurt, İ.N.; Nevşat, İ.E. Female Reproductive Pattern of Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun, 1896 (Brachyura: Portunidae) in Iskenderun Bay, Eastern Mediterranean. Zoology in the Middle East 2018, 64, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchessaux, G.; Gjoni, V.; Sarà, G. Environmental Drivers of Size-Based Population Structure, Sexual Maturity and Fecundity: A Study of the Invasive Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus (Rathbun, 1896) in the Mediterranean Sea. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0289611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumer, C.; Teksam, İ.; Karatas, H.; Beyhan, T.; Aydin, C.M. Growth and Reproduction Biology of the Blue Crab, Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896, in the Beymelek Lagoon (Southwestern Coast of Turkey). Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2013, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androulidakis, Y.; Makris, C.; Kombiadou, K.; Krestenitis, Y.; Stefanidou, N.; Antoniadou, C.; Krasakopoulou, E.; Kalatzi, M.-I.; Baltikas, V.; Moustaka-Gouni, M.; et al. Oceanographic Research in the Thermaikos Gulf: A Review over Five Decades. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2024, 12, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykousis, V.; Chronis, G. Mechanisms of Sediment Transport and Deposition: Sediment Sequences and Accumulation during the Holocene on the Thermaikos Plateau, the Continental Slope, and Basin (Sporadhes Basin), Northwestern Aegean Sea, Greece. Marine Geology 1989, 87, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykousis, V.; Collins, M.B.; Ferentinos, G. Modern Sedimentation in the N.W. Aegean Sea. Marine Geology 1981, 43, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulos, S.E.; Chronis, G.T.; Collins, M.B.; Lykousis, V. Thermaikos Gulf Coastal System, NW Aegean Sea: An Overview of Water/Sediment Fluxes in Relation to Air–Land–Ocean Interactions and Human Activities. Journal of Marine Systems 2000, 25, 47–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmi, E.J., III; Bishop, J.M. Variations in Total Width-Weight Relationships of Blue Crabs, Callinectes Sapidus, in Relation to Sex, Maturity, Molt Stage, and Carapace Form. Journal of Crustacean Biology 1983, 3, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadman, L.R.; Weinstein, M.P. Size-Weight Relationships of Postecdysial Juvenile Blue Crabs ( Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun) from the Lower Chesapeake Bay. Journal of Crustacean Biology 1985, 5, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugolo, L.J.; Knotts, K.S.; Lange, A.M.; Crecco, V.A. Stock Assessment of Chesapeake Bay Blue Crab (Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun). J. Shellfish Res. 1998, 17, 1321–1345. [Google Scholar]

- Hard, W.L. Ovarian Growth and Ovulation in the Mature Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun; Chesapeake Biological Laboratory: Solomons, ML, USA, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Sainte-Marie, B. Reproductive Cycle and Fecundity of Primiparous and Multiparous Female Snow Crab, Chionoecetes Opilio, in the Northwest Gulf of Saint Lawrence. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1993, 50, 2147–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemberling, A.A.; Darnell, M.Z. Distribution, Relative Abundance, and Reproductive Output of Spawning Female Blue Crab (Callinectes Sapidus) in Offshore Waters of the Gulf of Mexico. FB 2020, 118, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, E.P., Jr. Life History of the Blue Crab. Bulletin of the United States Bureau of Fisheries 1919, 36, 95–128. [Google Scholar]

- Lipcius, R. Blue-Crab Population-Dynamics In Chesapeake Bay - Variation In Abundance (York River, 1972-1988) And Stock-Recruit Functions. Bulletin of Marine Science 1990, 46, 180–194. [Google Scholar]

- Forward, R.B.; Cohen, J.H. Factors Affecting the Circatidal Rhythm in Vertical Swimming of Ovigerous Blue Crabs, Callinectes Sapidus, Involved in the Spawning Migration. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 2004, 299, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, R.; Hines, A.H.; Wolcott, T.G.; Wolcott, D.L.; Kramer, M.A.; Lipcius, R.N. The Timing and Route of Movement and Migration of Post-Copulatory Female Blue Crabs, Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun, from the Upper Chesapeake Bay. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 2005, 319, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, H.V.; Wolcott, D.L.; Wolcott, T.G.; Hines, A.H. Post-Mating Behavior, Intramolt Growth, and Onset of Migration to Chesapeake Bay Spawning Grounds by Adult Female Blue Crabs, Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 2003, 295, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, S.D.; Tankersley, R.A.; Hench, J.L.; Forward, R.B.; Luettich, R.A. Movement Patterns and Trajectories of Ovigerous Blue Crabs Callinectes Sapidus during the Spawning Migration. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2004, 60, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipcius, R.N.; Stockhausen, W.T. Concurrent Decline of the Spawning Stock, Recruitment, Larval Abundance, and Size of the Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus in Chesapeake Bay. Marine Ecology-Progress Series 2002, 226, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epifanio, C.E. Larval Biology. In Biology of the Blue Crab,edited by Kenney, V. S. and E. Cronin.; College Park, MD: Maryland Sea Grant, 2007; pp. 513–533. [Google Scholar]

- Hines, A.H. Ecology of Juvenile and Adult Blue Crabs: Summary of Discussion of Research Themes and Directions. Bulletin of Marine Science. 2003, 72, 423–433. [Google Scholar]

- Millikin, M.R.; Williams, A.B. Synopsis of Biological Data on the Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Darnell, M.Z.; Kemberling, A.A. Large-Scale Movements of Postcopulatory Female Blue Crabs Callinectes Sapidus in Tidal and Nontidal Estuaries of North Carolina. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 2018, 147, 716–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnell, M.; Rittschof, D.; Darnell, K.; McDowell, R. Lifetime Reproductive Potential of Female Blue Crabs Callinectes Sapidus in North Carolina, USA. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2009, 394, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzano, A.J.; McConaugha, J.R.; Philips, K.B.; Johnson, D.F.; Clark, J. Vertical Distribution of First Stage Larvae of the Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus, at the Mouth of Chesapeake Bay. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 1983, 16, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epifanio, C.E.; Valenti, C.C.; Pembroke, A.E. Dispersal and Recruitment of Blue Crab Larvae in Delaware Bay, U.S.A. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 1984, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipcius, R.; Engel, W.A.V. Blue-Crab Population-Dynamics In Chesapeake Bay - Variation In Abundance (York River, 1972-1988) And Stock-Recruit Functions. Bulletin of Marine Science 1990, 46, 180–194. [Google Scholar]

- Epifanio, C.E.; Garvine, R.W. Larval Transport on the Atlantic Continental Shelf of North America: A Review. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2001, 52, 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesilyurt, I.N.; Tureli, C. Settlement of Blue Crab (Callinectes Sapidus) Megalopae in the North Shore of Yumurtalik Cove (Turkey). Fresenius Environmental Bulletin 2016, 25, 1007–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Fernández, A.; Rodilla, M.; Prado, P.; Falco, S. Early Life Stages of the Invasive Atlantic Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus in the Western Mediterranean Sea. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2024, 296, 108593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitz, H.C.; Wiegert, R.G. Local Population Dynamics of Estuarine Blue Crabs: Abundance, Recruitment and Loss. Marine Ecology Progress Series 1992, 87, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancinelli, G.; Carrozzo, L.; Costantini, M.L.; Rossi, L.; Marini, G.; Pinna, M. Occurrence of the Atlantic Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun, 1896 in Two Mediterranean Coastal Habitats: Temporary Visitor or Permanent Resident? Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2013, 135, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrozzo, L.; Potenza, L.; Carlino, P.; Costantini, M.L.; Rossi, L.; Mancinelli, G. Seasonal Abundance and Trophic Position of the Atlantic Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun 1896 in a Mediterranean Coastal Habitat. Rend. Fis. Acc. Lincei 2014, 25, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lycett, K.A.; Shields, J.D.; Chung, J.S.; Pitula, J.S. Population Structure of the Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus in the Maryland Coastal Bays. shre 2020, 39, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jivoff, P. A Review of Male Mating Success in the Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus, in Reference to the Potential for Fisheries-Induced Sperm Limitation. Bulletin of Marine Science. 2003, 72, 273–286. [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson, R.A. Pheromone Communication in the Reproductive Behavior of the Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus †. Marine Behaviour and Physiology 1980, 7, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jivoff, P.; Hines, A.H. Female Behaviour, Sexual Competition and Mate Guarding in the Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus. Anim Behav 1998, 55, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rains, S.A.M.; Wilberg, M.J.; Miller, T.J. Sex Ratios and Average Sperm per Female Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus in Six Tributaries of Chesapeake Bay. Marine and Coastal Fisheries 2016, 8, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.L.; Fehon, M.M. Blue Crab (Callinectes Sapidus) Population Structure in Southern New England Tidal Rivers: Patterns of Shallow-Water, Unvegetated Habitat Use and Quality. Estuaries and Coasts 2021, 44, 1320–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, H.R.; Crowley, C.E.; Walters, E.A. Blue Crab Spawning and Recruitment in Two Gulf Coast and Two Atlantic Estuaries in Florida. Marine and Coastal Fisheries 2021, 13, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.J.; Branco, J.O.; Christoffersen, M.L.; Junior, F.F.; Fracasso, H.A.A.; Pinheiro, T.C. Population Biology of Callinectes Danae and Callinectes Sapidus (Crustacea: Brachyura: Portunidae) in the South-Western Atlantic. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 2009, 89, 1341–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severino-Rodrigues, E.; Musiello-Fernandes, J.; Mour, Á.A.S.; Branco, G.M.P.; Canéo, V.O.C. Fecundity, Reproductive Seasonality and Maturation Size of Callinectes Sapidus Females (Decapoda: Portunidae) in the Southeast Coast of Brazil. Revista de Biología Tropical 2013, 61, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.R. Effect of Temperature and Salinity on Size at Maturity of Female Blue Crabs. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 1999, 128, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho-Saucedo, L.; Ramírez-Santiago, C.; Pérez, C. Histological Description of Gonadal Development of Females and Males of Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun, 1896 (Decapoda: Portunidae). jzoo 2015, 32, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R. 1982.

- Lipcius, R.N.; Eggleston, D.B.; Heck, K.L.; Seitz, R.D.; Montfrans, J.V. Post-Settlement Abundance, Survival, and Growth of Postlarvae and Young Juvenile Blue Crabs in Nursery Habitats. In Biology of the Blue Crab; Kenney, V.S., Cronin, E., Eds.; Maryland Sea Grant Program: College Park, MD, USA, 2007; pp. 535–565. [Google Scholar]

- Archambault, J.A.; Wenner, E.L.; Whitaker, J.D. Life History and Abundance of Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun, at Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. Bulletin of Marine Science 1990, 46, 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Tagatz, M.E. Biology of the Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun, in the St. Johns River, Florida. United States Fish and Wildlife Service Fishery Bulletin 1968, 67, 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hines, A.H.; Johnson, E.G.; Darnell, M.Z.; Rittschof, D.; Miller, T.J.; Bauer, L.J.; Rodgers, P.; Aguilar, R. Predicting Effects of Climate Change on Blue Crabs in Chesapeake Bay. In Proceedings of the Biology and Management of Exploited Crab Populations under Climate Change; Alaska Sea Grant, University of Alaska Fairbanks, April 27 2011; pp. 109–127. [Google Scholar]

- Epifanio, C.E.; Masse, A.K.; Garvine, R.W. Transport of Blue Crab Larvae by Surface Currents off Delaware Bay, USA. Marine Ecology Progress Series 1989, 54, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipcius, R.; Stockhausen, W.T.; Seitz, R.; Geer, P.J. Spatial Dynamics and Value of a Marine Protected Area and Corridor for the Blue Crab Spawning Stock in Chesapeake Bay. Bulletin of Marine Science 2003, 72, 453–469. [Google Scholar]

- Gelpi, C.; Condrey, R. e; Fleeger, J. w; Dubois, S.; Fleeger, J. w; Dubois, S. Discovery, Evaluation, and Implications of Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus, Spawning, Hatching, and Foraging Grounds in Federal (Us) Waters Offshore of Louisiana. Bulletin Of Marine Science 2009, 85, 203–222. [Google Scholar]

- Gelpi, C.; Fry, B.; Condrey, R.; Fleeger, J.; Dubois, S. Using δ13C and δ15N to Determine the Migratory History of Offshore Louisiana Blue Crab Spawning Stocks. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2013, 494, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Olsen, Z.; Glen Sutton, T.W.; Gelpi, C.; Topping, D. Environmental Drivers of the Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Spawning Blue Crabs Callinectes Sapidus in the Western Gulf of Mexico. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 2017, 37, 920–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogburn, M.B.; Habegger, L.C. Reproductive Status of Callinectes Sapidus as an Indicator of Spawning Habitat in the South Atlantic Bight, USA. Estuaries and Coasts 2015, 38, 2059–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnell, M.Z.; Wolcott, T.G.; Rittschof, D. Environmental and Endogenous Control of Selective Tidal-Stream Transport Behavior during Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus Spawning Migrations. Mar Biol 2012, 159, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggleston, D.B.; Millstein, E.; Plaia, G. Timing and Route of Migration of Mature Female Blue Crabs in a Tidal Estuary. Biology Letters 2015, 11, 20140936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epifanio, C.E.; Cohen, J.H. Behavioral Adaptations in Larvae of Brachyuran Crabs: A Review. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 2016, 482, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, A.H.; Wolcott, T.G.; González-Gurriarán, E.; González-Escalante, J.L.; Freire, J. Movement Patterns and Migrations in Crabs: Telemetry of Juvenile and Adult Behaviour in Callinectes Sapidus and Maja Squinado. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 1995, 75, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Engel, W. Factors Affecting The Distribution And Abundance Of The Blue Crab In Chesapeake Bay; Pennsylvania Academy of Science, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Truitt, R.V. The Blue in Our Water Resources and Their Eonscrvstlon. Chesapeake Biol. Lab. Corttríb. 1939, 27, 10–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh, P.-W.; McClintock, J.B.; Hopkins, T.S. Population Dynamics and Life History Characteristics of the Blue Crabs Callinectes Similis and C. Sapidus in Bay Environments of the Northern Gulf of Mexico. Marine Ecology 1993, 14, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, D.J.; Perry, H.; Biesiot, P.; Fulford, R. Fecundity and Egg Diameter of Primiparous and Multiparous Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus (Brachyura: Portunidae) in Mississippi Waters. Journal of Crustacean Biology 2012, 32, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, G.H.; Rittschof, D.; Latanich, C. Spawning Biology of the Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus, in North Carolina. Bulletin of Marine Science 2006, 79, 273–285. [Google Scholar]

- Darnell, M.Z.; Rittschof, D.; Forward, R.B. Endogenous Swimming Rhythms Underlying the Spawning Migration of the Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus: Ontogeny and Variation with Ambient Tidal Regime. Mar Biol 2010, 157, 2415–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q. Modification of the Ricker Stock Recruitment Model to Account for Environmentally Induced Variation in Recruitment with Particular Reference to the Blue Crab Fishery in Chesapeake Bay. Fisheries Research 1985, 3, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, M.J.; Lipcius, R.N. Population Dynamics and Fisheries. In Biology of the Blue Crab,edited by Kenney, V. S. and E. Cronin.; College Park, MD: Maryland Sea Grant, 2007; pp. 711–755. [Google Scholar]

- Willan, R.C.; Russell, B.C.; Murfet, N.B.; Moore, K.L.; McEnnulty, F.R.; Horner, S.K.; Hewitt, C.L.; Dally, G.M.; Campbell, M.L.; Bourke, S.T. Outbreak of Mytilopsis Sallei (Récluz, 1849) (Bivalvia: Dreissenidae) in Australia. Molluscan Research 2000, 20, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bax, N.; Carlton, J.T.; Mathews-Amos, A.; Haedrich, R.L.; Howarth, F.G.; Purcell, J.E.; Rieser, A.; Gray, A. The Control of Biological Invasions in the World’s Oceans. Conservation Biology 2001, 15, 1234–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampert, A. Optimizing Strategies for Slowing the Spread of Invasive Species. PLOS Computational Biology 2024, 20, e1011996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| A. Monthly sampling stations. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling stations (and code) | Depth (m) | Latitude | Longitude | ||

| Methoni Bay (ΜETH 1) | ≤1 | 40°27’37.50”N | 22°35’23.88”E | ||

| Methoni Bay (ΜETH 2) | 3 | 40°27’31.98”N | 22°35’57.00”E | ||

| Methoni Bay (ΜETH 3) | 6 | 40°27’38.70”N | 22°37’30.48”E | ||

| Methoni Bay (ΜETH 4) | 9 | 40°27’31.62”N | 22°38’4.74”E | ||

| Bara (BAR 1) | ≤1 | 40°29’10.98”N | 22°39’37.56”E | ||

| Bara (BAR 2) | 2.5 | 40°29’4.92”N | 22°40’1.98”E | ||

| Off Aliakmonas Delta (AL 2) | 3 | 40°28’18.90”N | E | ||

| Off Aliakmonas Delta (AL 3) | 9 | 40°28’14.46”N | 22°40’12.60”E | ||

| Loudias Bay (LOUD 1) | ≤1 | 40°30’4.08”N | 22°39’32.40”E | ||

| Loudias Bay (LOUD 2) | 3 | 40°30’8.58”N | 22°39’53.16”E | ||

| Loudias Bay (LOUD 3) | 6 | 40°30’10.98”N | 22°40’19.32”E | ||

| Loudias bay (LOUD 4) | 9 | 40°30’12.66”N | 22°40’43.62”E | ||

| B. Seasonal sampling stations. | |||||

| Sampling stations (and code) | Depth (m) | Latitude | Longitude | ||

| Off Aliakmonas Delta (AL 4) | 15 | 40°27’38.82”N | 22°39’50.64”E | ||

| Off Aliakmonas Delta (AL 5) | 25 | 40°27’24.60”N | 22°40’12.90”E | ||

| Off Axios Delta (AX 1) | ≤1 | 40°30’9.30”N | 22°44’2.34”E | ||

| Off Axios Delta (AX 2) | 3 | 40°30’1.86”N | 22°44’6.42”E | ||

| Off Axios Delta (AX 3) | 6 | 40°29’58.74”N | 22°44’9.54”E | ||

| Off Axios Delta (AX 4) | 9 | 40°29’54.42”N | 22°44’13.56”E | ||

| Long line mussel (Mytilus galloprovinciallis) culture unit (LL_MYT) |

7-10 | 40°30’50.04”N | 22°40’44.64”E | ||

| Hang mussel (Mytilus galloprovinciallis culture unit (H_MYT) |

3.5 | 40°30’52.08”N | 22°41’5.10”E | ||

| Loudias River (LOUD_R) | 2.5-3 (800 m from the sea) |

40°32’6.72”N 40°32’7.56”N |

22°40’47.58”E 22°40’46.14”E |

||

| C. Experimental sampling stations. | |||||

| Sampling stations (and code) | Depth (m) | Latitude | Longitude | ||

| Bara (BAR 1) | <1 | 40°29’10.98”N | 22°39’37.56”E | ||

| Bara (BAR 3) | <1 | 400 29’ 9.19’’ Ν | 220 39’16. 31’’Ε | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).