1. Introduction

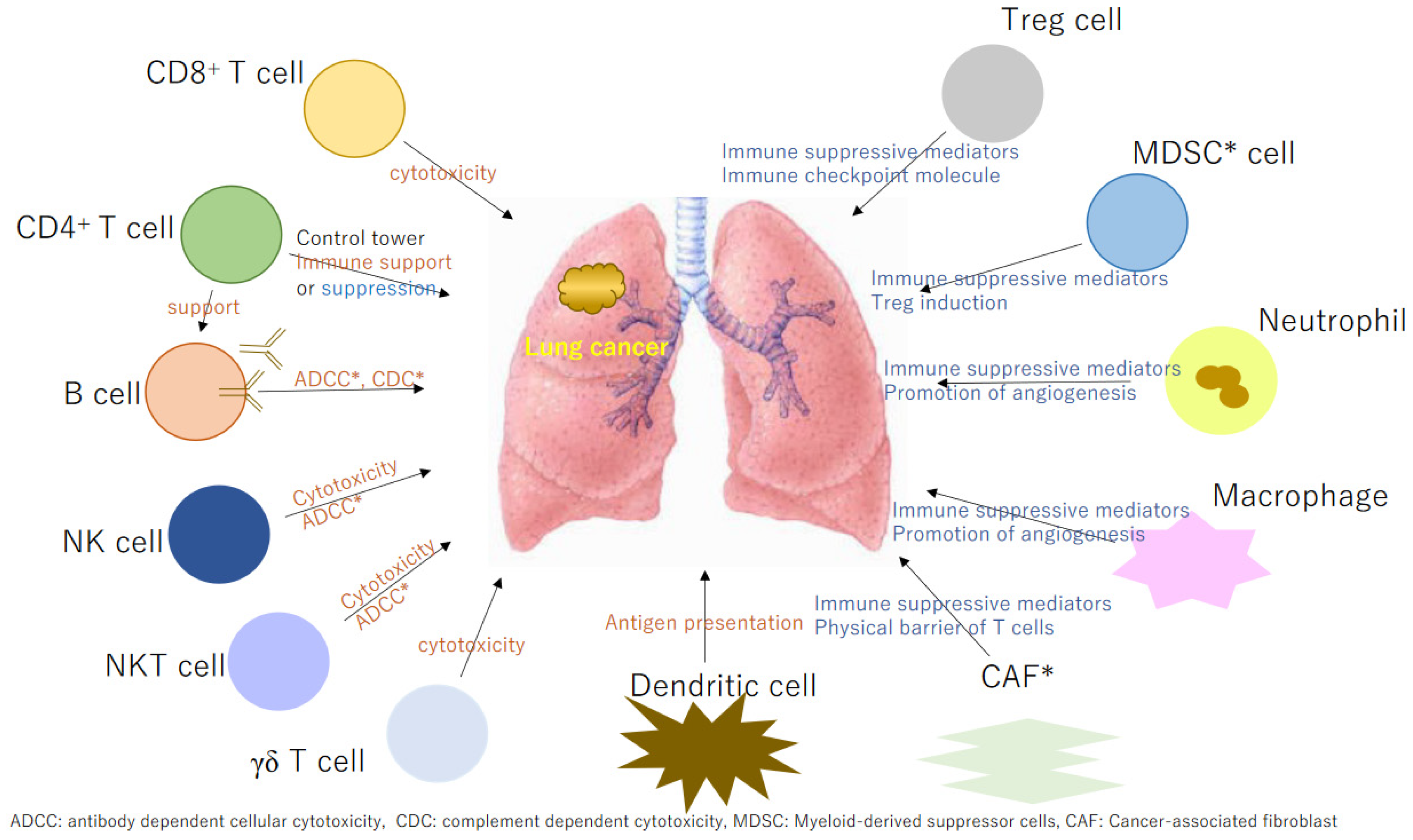

Therapies for lung cancer have undergone dramatic changes, with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) playing key roles. The antitumor immune response that acts locally in the area of the tumor is primed in the regional lymph nodes. However, it is also recognized that there are mechanisms that can maintain the activity of antitumor cells in the locality of the cancer. Examination of the immune tumor microenvironment (TME) has critical prognostic value and can supplement histopathological and molecular biomarkers for the evaluation of patient responses to treatment. The TME refers to the environment surrounding tumor cells; it is dynamic and is constantly subject to various influences from other normal cells and tissues. Humans are inherently equipped with tumor immunity to eliminate tumors; however, in the TME, tumor immunity can be suppressed by various mechanisms. In addition to tumor cells themselves suppressing tumor immunity, the important role of non-tumor cells in the TME is gradually becoming clear, and the effectiveness of ICIs is greatly influenced by the TME. Furthermore, immune responses are multifaceted, with innate and adaptive immunity. Adaptive immunity comprises cellular and humoral immunity. In current cancer treatments, ICIs have demonstrated excellent efficacy; however, in some cases, they are ineffective. To achieve higher therapeutic efficacy, the development of next-generation lung cancer immunotherapies is essential. However, the effector cells involved in cancer immune responses are highly diverse and many cells and mediator molecules promote or suppress effector cells (

Figure 1), which complicates our understanding. In this review, we considered each factor thought to be related to next-generation lung cancer immunotherapy.

2. Tertiary Lymphoid Structures

A cycle exists in which activated T cells gather in the interstitium, particularly in the tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS), where immune cells interact to maintain their effector functions. TLS, which represent organized secondary lymphoid organ-like cellular aggregates occur locally [

1] and may regulate antitumor immune responses through a mechanism distinct from that of the normal cancer immune cycle. At tumor sites, TLS enable the localized presentation of cancer antigens by dendritic cells (DCs) and the production of effector T cells and antibody-producing plasma cells, which is associated with a favorable prognosis in a variety of cancer types [

2]. Within tumors, B cells were not found alone but tended to co-localize with CD4 and CD8 tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), and cases in which B cells and CD8 T cells were found simultaneously within tumors tended to have a better prognosis than cases in which only CD8 T cells were found [

3]. TLS are ectopic lymphoid organs that develops in nonlymphoid tissues at sites of chronic inflammation, including tumors. A T-cell zone containing mature DCs is formed around CD20

+ B cells, plasma cells, follicular helper T cells, and follicular DCs.

In lung cancer, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, oral squamous cell carcinoma, and invasive breast cancer, the presence of TLS have been associated with increased overall and recurrence-free survival [

1].

Tumor-infiltrating B cells within the TLS are associated with the therapeutic effects of ICI [

4,

5,

6].

3. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes

TILs are lymphocytes that infiltrate tumors and include tumor-reactive and antigen-specific lymphocytes. A treatment method in which tumor-reactive T cells in TILs were expanded and infused was attempted. It has been suggested that TILs also contain many cell groups that negatively regulate antitumor immune responses, including regulatory T cells. In addition to lymphocytes, regulatory cell groups in the tumor stroma include myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), and mesenchymal stem cells. Depending on the degree of T-cell infiltration, a tumor can be classified into three types: immune desert, immune-excluded, and inflamed. In the immune desert, immune cells in the tumor are clearly depleted, which may be related to immune cell repulsion or migration (possibly due to a lack of attractive chemokines, hypoxia, and lack of nutrients). In immune exclusion, the presence of inhibitory stroma and extracellular matrix (ECM) may prevent T cells from effectively migrating and coming into direct contact with cancer cells, thereby allowing cancer cells to survive. Peritumoral or intratumoral inflammatory cells that promote immune responses may activate TILs and increase their function and proliferation [

7].

In TILS, programmed cell death-1 (PD-1)

+ CD8

+ T cells are associated with a good prognosis, while PD-1

+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) are associated with a poor prognosis, and the balance of the ratio of PD-1 expression between them could be a biomarker [

8].

4. Tumor Mutation Burden

The greater the tumor mutation burden (TMB), the more cancer-specific CD8+ T cells will be present and infiltrate the tumor, which is thought to result in a hot tumor. When cancer cells are exposed to interferon (IFN)-γ secreted by CD8+ T cells that have infiltrated into the tumor, they increase the expression of programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), thereby suppressing the antitumor effect of CD8+ T cells via the inhibitory receptor PD-1 expressed on activated CD8+ T cells. ICIs are thought to be effective in treating such hot tumors.

In some cancers, reduced mismatch repair (MMR) has been observed. In sporadic MMR-deficient (dMMR) solid tumors, the cause is often acquired hypermethylation of the promoter region of the

MLH1 gene or reduced expression owing to mutations in the MMR genes [

9]. The occurrence of a congenital pathogenic variant of the

MLH1,

MSH2,

MSH6, or

PMS2 genes, or a deletion of the epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EPCAM) gene [

10,

11,

12] adjacent to the upstream region of the

MSH2 gene in one allele, it is called Lynch syndrome, and dMMR tumors are known as Lynch-associated tumors.

4.1. CD8+ T Cells

CD8

+ T cells recognize antigen peptides presented on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I by their specific T cell receptor (TCR) and exert their effector functions by releasing perforin, granzymes, etc. However, CD8

+ T cells become exhausted in cancer and chronic infections, and their cytotoxic activity and proliferative ability decrease. In some cases, CD8

+ T cells infiltrate the tumor, whereas in others, there is little infiltration. If tumor-specific CD8

+ T cells are present, they become cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), infiltrate the tumor, and damage cancer cells. This may make immunotherapy more effective and improve prognosis. It has been reported that CD103

+ CD8

+ T cells infiltrating the tumor can be used as biomarkers for ICI effectiveness [

13]. CD103 is a ligand for the adhesion molecule E-cadherin. E-cadherin is expressed by epithelial cells, forming part of the adherent junctions between epithelial cells. When T cells infiltrate regions with epithelial cells, including cancer cells, they begin to express CD103 [

14]. Therefore, it has been reported that CD103

+ T cells have previously encountered epithelial cells, including cancer cells, and are almost identical to tumor-specific T cells.

Using resected specimens from patients with lung cancer, CD103+ lymphocytes were confirmed by immunostaining in the local tumor area and associated lymph nodes. It has been reported that prognosis after lung cancer resection is better when there was a high level of CD103+ lymphocyte infiltration.

We analyzed the immunological molecular expression in local and regional lymph node microenvironments using resection sections from 50 cases of lung squamous cell carcinoma. The expression of MHC class I and PD-L1 molecules in the tumor did not affect the prognosis; however, CD103

+ lymphocyte infiltration was a good prognostic factor [

15]. Furthermore, an analysis of 21 cases of non-small cell lung cancer suggested that an increase in CD103

+ CD39

+ CD8

+ T cells in the peripheral blood after ICI administration was a favorable prognostic factor, and that an increase in CD103

+ CD39

+ CD8

+ T cells may enhance the cancer immune response [

16]. PD-1

+ and CD8

+ T cells in TILs are associated with a good prognosis, whereas PD-1

+ Tregs in TILs are associated with a poor prognosis, and the balance of their PD-1 expression ratios can serve as a biomarker [

8]. In addition, we induced mutant p53-specific CTL clones from lymphocytes of the regional lymph nodes of patients with lung cancer, and demonstrated by TCR analysis (clonotypic polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method) that these CTL clones were present in the tumor locale and were involved in the cancer immune response [

17]. We also demonstrated that isolating tumor-specific TCR and transferring genes into γδ T cells, in a severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mouse model implanted with a human lung cancer cell line, resulted in tumor regression [

18]. As reviewed in another section, TCR-transduced cell therapy has been applied clinically and is attracting attention as next-generation immunotherapy.

4.2. CD4+ T Cells

CD4

+ T cells recognize antigen peptides presented on MHC class II molecules via their specific TCRs and are activated. They function as effector cells and participate in B-cell differentiation and proliferation. Kagamu et al. reported that patients whose peripheral blood CD62L

low CD4

+ T-cell populations decreased after ICI administration had a weakened therapeutic response, whereas those who survived for a long time maintained a high percentage of CD62L

low CD4

+ T-cells [

19]. Monitoring the immune status of CD4+ T-cells in the peripheral blood of patients receiving ICIs may predict treatment efficacy.

CD4

+ T helper (Th) lymphocytes act as key regulators of inflammation specific to the encountered threat, with a large (and expanding) list of Th subsets defined to date, including Th1, Th2, Th17, Th9, and Th22. Th1 responses are characterized by the production of IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interleukin (IL)-2 by T cells and are thought to be the essential subset for tumor rejection. IFN-γ generated from Th1 responses may synergize with IL-17 produced by Th17 cells to promote the secretion of the chemokines CXCL9 and CXCL10 that can recruit CTLs to the TME to target tumor cells [

20].

In addition to a chronic inflammatory TME, prolonged exposure to tumor antigens induces Th1 and other T cells that lack the typical polyfunctional phenotype (i.e., the ability to secrete large amounts of several cytokines) to express inhibitory receptors, such as PD-L1, lymphocyte activation gene 3 protein (LAG-3), and T-cell immunoglobulin domain and mucin domain protein 3 (TIM-3) [

21]. The antitumor efficiency of exhausted T cells is severely limited. Interestingly, a positive correlation was found between the number of CD8

+ TILs and a favorable clinical prognosis [

21,

22].

4.3. B Cells

B cells play a central role in humoral immunity. They express the membrane-type globulin B-cell receptor (BCR) on their cell surface, take up antigens into the cell, and present them to CD4+ T cells. Through the interactions between B and T cells, B cells differentiate into plasma cells and produce antibodies.

As the TLS mature, lymphoid follicles are often observed and are thought to contribute to the maintenance of the effector function of immune cells by interacting with T cells and B cells. It is also known that cases in which tumor-infiltrating B lymphocytes (TIBs), as well as CD8

+ T cells are present in the TLS, the tumor tend to have a better prognosis than cases in which only CD8

+ T cells are present [

23]. TIBs directly support antitumor immunity. Microdissection of melanoma TLS revealed clonal proliferation, isotype switching, and somatic mutations in BCR-rare cells, suggesting the induction of antigen-specific antibody responses [

24]. TIBs may also be involved in the maintenance of TLS by producing CXCR13 and lymphotoxin [

25]. TLS are associated with increased overall survival and progression-free survival in patients with lung cancer, colon cancer, pancreatic cancer, oral squamous cell carcinoma, and invasive breast cancer [

26]. TIBs in TLS are reportedly related to the therapeutic effects of ICIs [

27,

28,

29]. Activated T cells gather in the interstitium; in particular, in the TLS, immune cells interact with each other, creating a cycle that maintains the effector function of immune cells.

4.4. Regulatory T Cells

Treg cells suppress immune responses, including the excessive immune responses that cause autoimmune diseases, inflammatory diseases, and allergies. Conversely, when Treg cells work excessively, they suppress immune responses against pathogens such as cancer cells and promote cancer growth.

In 2003, Sakaguchi

et al. reported that the transcription factor forkhead box protein P3 (Foxp3), identified as the causative gene of the human autoimmune disease immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked (IPEX) syndrome, is selectively expressed in Treg cells and acts as a "master transcription factor" that controls their development, differentiation, and immunosuppressive functions [

30]. Since this discovery, extensive research on the mechanisms of Treg cell differentiation and function has been conducted, revealing that Foxp3 forms complexes with over 300 other transcription factors in Treg cells, binds to thousands of locations in the genome, and controls gene expression in Treg cells. Tregs maintain systemic immune homeostasis by regulating peripheral tolerance and attenuating autoimmune diseases [

31] via various immunosuppressive mechanisms [

32]. Treg depletion experiments in mice found that this population potently suppresses antitumor effector T cell responses and blocks tumor elimination by endogenous tumor-specific effector T cells [

33,

34]. Wing et al. reported that cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4) on Tregs reduced the expression of CD80/86, a costimulatory molecule on DCs, thereby suppressing T-cell activation [

35]. Anti-CTLA-4 antibodies suppress the function of CTLA-4 and can, therefore, control Treg function.

4.5. Natural Killer Cells

Natural killer (NK) cells kill cancer cells without sensitization. NK cells eliminate cancer cells through effector functions mediated by cytotoxic granule contents such as perforin and granzymes, death ligands such as Fas-ligand and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), and cytokine production such as IFN and TNF-α [

36]. MHC class I chain-related protein A and B (MICA/B) are ligands that activate NK cells through the activating receptor natural killer group 2 member D (NKG2D) [

37,

38,

39,

40], and downregulation of MICA/B expression induces immune evasion [

41,

42]. MHC class I molecules act on inhibitory receptors of NK cells, such as killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR), and suppress the effector functions of NK cells [

43]. Currently, attempts are being made to apply chimeric antigen receptor-T (CAR-T) cells and TCR-transduced T cells in immunotherapy by introducing CAR genes or T-cell receptors into NK cells [

44].

4.6. Natural Killer T Cells

Natural killer T (NKT) cells have an invariant TCR, Vα14Jα18 in mice and Vα24Jα18 in humans. The invariant TCR recognizes glycolipids such as α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) presented on the MHC class I-like molecule CD1d as a ligand [

45]. NKT cells are activated by stimulation with α-GalCer, and express cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF, as well as cytotoxic factors such as perforin, granzymes, FAS ligand, and TRAIL, which can directly damage cancer cells. NKT cells are also activated by DCs [

46], and it is known that activated NKT cells subsequently leads to DC maturation and activation, thereby inducing effective adaptive immunity [

47,

48].

4.7. γδ T Cells

γδ T cells express various receptors [

49]. 4-Hydroxy-3-dimethyl-allyl-pyrophosphate produced by bacteria, exogenous antigens derived from viruses, and endogenous phosphate antigens isopentenylpyrophosphate and triphosphoric acid 1-adenosin-5-yl ester 3-(3-methylbut-3-enyl) ester are recognized by γδ TCRs. MICA/B, which is expressed on the cell surface by stress, is recognized by NKG2D receptors. γδ T cell therapy has been administered to patients with treatment-resistant lung cancer, and 6 of 14 patients showed stable disease using RECIST, with a median progression-free survival of 126 days and a median survival time of 586 days. IFN-γ was detected in the blood of seven patients during treatment, and four of these showed stable disease. Although no statistically significant difference was detected, it is thought that an increase in IFN-γ in the blood may affect prognosis [

50,

51].

It was also reported that dysregulation of the local microbiota stimulated tissue-resident γδ T cells to produce IL-17 and other proinflammatory mediators, promoting neutrophil proliferation and tumor cell growth. This may further enhance inflammation and microbiota dysbiosis, establishing a vicious cycle that exacerbates tumor growth [

52].

5. Tumor-Associated Macrophages

Macrophages release inflammatory mediators and secrete angiogenic factors. In malignant tumors, macrophages are divided into two categories: M1 macrophages that are involved in the Th1 cell response to pathogens and promote antitumor immunity, and M2 macrophages that are involved in the Th2 cell response and suppress antitumor immunity [

53,

54]. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are primarily composed of M2 macrophages that transform the TME into an immunosuppressive and tumor-progressing state, leading to a poor prognosis [

54].

Microparticles released from irradiated tumor cells (RT-MPs) induce a wide range of antitumor effects and immunogenic cell death primarily via iron-dependent pathways. RT-MPs induce DNA double-strand breaks in tumor cells and significantly upregulate MHC-I expression on the membranes of non-irradiated cells, enhancing the recognition and killing of these cells by T cells [

55]. It was reported that RT-MPs can convert M2-TAMs in the pleural effusion microenvironment into M1-TAMs via the JAK-STAT and MAPK pathways [

56].

6. Dendritic Cells

When foreign substances enter the body, DCs phagocytose, process, and present fragmented antigen peptides to the MHC. Naïve T cells recognize and are activated by antigen peptides. DCs are essential for initiating immune responses. Tumors DCs infiltrating the TLS induce a Th1-type immune shift and improve lung cancer prognosis [

57]. Tissue-resident DCs can be divided into two major subsets based on transcription products and function. CD1c

+ DCs are thought to be generated from monocytes during the invasion of tumor sites, whereas CD141

+ DCs appear to be generated from DC-restricted precursors [

58,

59]. The expression of lymphotoxin beta transcripts by CD141

+ DC subsets in lung tumor tissues may reflect the contribution of CD141

+ DCs to TLS formation, possibly due to HEV-mediated lymphocyte recruitment [

60]. The expansion of intratumoral CD141

+ DCs may be an important strategy for inducing potent antitumor immunity. In a multicenter, single-arm, phase I/II study, a combination therapy consisting of anti-PD-L1 blockade and Wilms’ tumor antigen 1-DC vaccination was administered to patients with epithelioid malignant pleural mesothelioma [

61]. It was also reported that the use of a DC vaccine as postoperative adjuvant therapy in patients with pancreatic cancer resulted in good recurrence-free survival rates [

62].

7. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells

MDSCs, a heterogeneous group of immature myeloid cells, have immunosuppressive properties that increase in the blood and lymphatic tissues of patients with both cancer and infectious diseases [

63]. MDSCs are classified into polymorphonuclear MDSCs (CD11b

+CD14

-CD15

+ or CD11b

+CD14

-CD66b

+), which resemble neutrophils, and monocyte MDSCs (CD11b

+CD14

+CD15HLA-DR

low/-), which resemble monocytes. In patients with cancer, MDSCs suppress the anticancer immune reactions of CD4

+ T cells, CD8

+ T cells, and NK cells, inducing tumor progression. Strategies targeting MDSCs in cancer immunotherapy include promotion of MDSC differentiation [

64], inhibition of their suppressive function [

65,

66], and elimination of MDSCs [

67]. Pan et al. reported that MDSCs induce Tregs via CD40-CD40L [

68]. The blockade of CD40-CD40L may suppress the functions of MDSCs and Tregs and may have therapeutic effects.

8. Neutrophils

Neutrophils can also be recruited and infiltrate the TME as tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) [

69,

70]. TANs may promote tumor development by generating reactive oxygen species [

71], releasing neutrophil elastase to accelerate tumor growth [

72], secreting matrix metalloproteinase-9 to induce angiogenesis [

73], and forming neutrophil extracellular traps to promote tumor metastasis [

74]. Neutrophil abundance has prognostic significance in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Patients with a high neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio had reduced progression-free survival and overall survival [

75,

76]. Patients with early stage NSCLC and increased CD66b-positive neutrophil infiltration were more likely to experience recurrence after surgery [

77]. Approaches that inhibit cytokines and chemokines that promote neutrophil infiltration, or mediators involved in neutrophil function, may be necessary.

9. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts

As central components of the TME in primary and metastatic tumors, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) profoundly influence the behavior of cancer cells and are involved in cancer progression through extensive interactions with cancer cells and other stromal cells. CAFs exert immunosuppressive effects by acting as a physical barrier to T cells and releasing immunosuppressive chemical mediators. CAFs secrete matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), including MMP2, MMP3, and MMP9, or activate YES-associated proteins to promote ECM degradation and remodeling, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and cancer stem-cell stemness [

78,

79,

80,

81,

82]. In the TME, the hypoxic niche communicates bidirectionally with the mechanical microenvironment mediated by CAFs. CAFs become elongated and spindle-shaped, secrete increased amounts of type 1 collagen, promote matrix adhesion and mesenchymal morphology, and produce ECM with increased stiffness and collagen fiber alignment, all of which support the invasion and migration of breast cancer cells [

83]. Cords et al. found that CAFs are a heterogeneous group with both poor and good prognostic phenotypes. Therefore, it may be necessary to develop treatments that consider the tailored phenotype [

84].

10. Chimeric Antigen Receptor-T Cells

CAR-T and TCR-transduced effector cells are genetically engineered synthetic biological approaches that target tumor-specific antigens and exert remarkable therapeutic effects [

85,

86]. The components of CAR-T cells have been continuously improved and consist of a single-chain antibody (single-chain antibody variable fragment, scFV), a flexible connecting chain (hinge), a transmembrane domain and the signaling domains of the costimulatory molecule CD28, 4-1BB or OX-40 and stimulatory molecule CD3ζ and FcRγchain (

Figure 2). CAR-T cell immunotherapy has demonstrated remission rates of 80–90% in hematological malignancies, with CD19-targeted CAR-T cells approved for the treatment of blood cancers. The recent success of CAR-T therapy has transformed the cancer treatment landscape and spurred research efforts to apply these therapeutic effects to solid tumors, such as lung cancer [

87]. Novel approaches are currently being investigated to test the applicability of CAR T-cell immunotherapy in lung cancer. CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) is upregulated in lung cancer tissues and cell lines [

88], and has been validated as a target for NSCLC treatment [

89]. The MAGE-A1 antigen was selected by analyzing the cancer/testis antigen database, and MAGE-A1-specific CAR-T cell immunotherapy against lung adenocarcinoma has shown to be effective and safe [

90].

11. T Cell Receptor-Transduced Effector Cells

TCR-transduced effector cell therapy is a promising treatment strategy that induces strong cellular immune responses against lung cancer. However, it has limitations in that it can only be administered to patients with matched cancer antigen expression and HLA types. HLA0802-restricted KRAS mutation-specific TCR-injected autologous T-cell therapy resulted in 72% tumor regression in patients with KRAS mutation-positive pancreatic cancer. Furthermore, TCR-injected autologous T cells were detected in the peripheral blood more than six months after administration [

91]. Robbins et al. reported that NY-ESO-1-specific TCR-transduced T cells were administered to patients with synovial cell sarcoma and melanoma, and clinical responses were observed in four of six patients with synovial cell sarcoma and five of 11 patients with melanoma [

92].

12. Conclusion

The widespread use of ICIs has caused a paradigm shift in lung cancer treatment, which continues to evolve. ICIs have fewer side effects than traditional chemotherapeutic drugs, improve overall survival rates, and play a central role in lung cancer chemotherapy. Currently, patients with lung cancer have several treatment options, ranging from single-agent immunotherapy to quadruple therapy, which combines immunotherapy with chemotherapy and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor drugs. Elucidating the mechanism of resistance to ICIs is important for the development of next-generation immunotherapy; however, as reviewed in this article, the interactions between cells and molecules with the immune system and the immunological environment of the tumor are intricately related, making clarification of resistance mechanisms difficult. Perhaps, we are entering an era in which treatment plans will be individually tailored to each patient's tumor immunological microenvironment and molecular expression.

Cell therapy has the potential to become a powerful next-generation therapy. With the development of molecular biology techniques, it is becoming possible to obtain ideal immunotherapeutic effects by transferring receptors with higher tumor specificity and affinity to more powerful effector cells. To develop promising treatments for effective lung cancer in the future, it is necessary to continue research to deepen our understanding of lung cancer and the surrounding immune system.

Author Contributions

Conception of the view, Y.I.; writing the manuscript, Y.I.; helping with making figures, N.S., R.T., T.U.; revising the manuscript, Y.I, H.N.; proposing constructive suggestion, H.S., H.I., T.K., H.I, K.K., and H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Ichiki acknowledges grant support from JSPS KAKENHI (22K09013).

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at

https://tlcr.amegroups. com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-24-142/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement

The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Abreviations

| ICI |

immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| TLS |

Tertiary lymphoid structures |

| DC |

dendritic cell |

| TIL |

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte |

| MDSC |

myeloid-derived suppressor cell |

| TAM |

tumor-associated macrophage |

| CAF |

cancer-associated fibroblast |

| MSC |

mesenchymal stem cell |

| ECM |

extracellular matrix |

| PD-1 |

programmed cell death -1 |

| Treg |

regulatory T cell |

| TMB |

Tumor mutation burden |

| PD-L1 |

programmed cell death - ligand 1 |

| MMR |

mismatch repair |

| dMMR |

MMR deficient |

| EPCAM |

epithelial cell adhesion molecule |

| MHC |

major histocompatibility complex |

| CTL |

cytotoxic T lymphocyte |

| TCR |

T cell receptor |

| PCR |

polymerase chain reaction |

| SCID mouse |

severe combined immunodeficiency mouse |

| IFN |

interferon |

| TNF |

tumor necrosis factor |

| IL |

interleukin |

| LAG-3 |

lymphocyte activation gene 3 protein |

| TIM-3 |

T cell immunoglobulin domain and mucin domain protein 3 |

| BCR |

B-cell receptor |

| TIB |

tumor infiltrating B lymphocyte |

| IPEX |

immunedysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked |

| Foxp3 |

forkhead box protein P3 |

| CTLA-4 |

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen-4 |

| NK cell |

Natural killer cell |

| TRAIL |

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand |

| MICA/B |

MHC class I chain-related gene A and B |

| NKG2D |

natural killer group 2 member D |

| KIR |

killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors |

| NKT cell |

Natural killer T cell |

| α-GalCer |

α-galactosylceramide |

| TME |

tumor microenvironment |

| RT-MPS |

Microparticles released from irradiated tumor cells |

| DSB |

DNA double-strand break |

| LTB |

lymphotoxin beta |

| TAN |

tumor-associated neutrophils |

| ROS |

reactive oxygen species |

| NE |

neutrophil elastase |

| MMP-9 |

matrix metalloproteinase-9 |

| NSCLC |

non-small cell lung cancer |

| NLR |

neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| PFS |

progression-free survival |

| OS |

overall survival |

| CAR-T cell |

Chimeric antigen receptor- T cell |

| CXCR4 |

CXC chemokine receptor 4 |

References

- Sautès-Fridman, C.; Petitprez, F.; Calderaro, J.; Fridman, W.H. Tertiary lymphoid structures in the era of cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Romero, K.; Rodríguez, R.M.; Amedei, A.; Barceló-Coblijn, G.; Lopez, D.H. Immune Landscape in Tumor Microenvironment: Implications for Biomarker Development and Immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieu-Nosjean, M.-C.; Goc, J.; Giraldo, N.A.; Sautès-Fridman, C.; Fridman, W.H. Tertiary lymphoid structures in cancer and beyond. Trends Immunol. 2014, 35, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitprez, F.; de Reyniès, A.; Keung, E.Z.; Chen, T.W.-W.; Sun, C.-M.; Calderaro, J.; Jeng, Y.-M.; Hsiao, L.-P.; Lacroix, L.; Bougoüin, A.; et al. B cells are associated with survival and immunotherapy response in sarcoma. Nature 2020, 577, 556–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmink, B.A.; Reddy, S.M.; Gao, J.; Zhang, S.; Basar, R.; Thakur, R.; Yizhak, K.; Sade-Feldman, M.; Blando, J.; Han, G.; et al. B cells and tertial lymphoid structures promote immunotherapy response. Nature. 2020, 577, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrita, R.; Lauss, M.; Sanna, A.; Donia, M.; Larsen, M.S.; Mitra, S.; Johansson, I.; Phung, B.; Harbst, K.; Vallon-Christersson, J.; et al. Tertiary lymphoid structures improve immunotherapy and survival in melanoma. Nature 2020, 577, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellman, I.; Chen, D.S.; Powles, T.; Turley, S.J. The cancer-immunity cycle: Indication, genotype, and immunotype. Immunity 2023, 56, 2188–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, S.; Togashi, Y.; Kamada, T.; Sugiyama, E.; Nishinakamura, H.; Takeuchi, Y.; Vitaly, K.; Itahashi, K.; Maeda, Y.; Matsui, S.; et al. The PD-1 expression balance between effector and regulatory T cells predicts the clinical efficacy of PD-1 blockade therapies. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 1346–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGivern, A.; Wynter, C.; Whitehall, V.; Kambara, T.; Spring, K.; Walsh, M.D.; Barker, M.; Arnold, S.; Simms, L.; Leggett, B.; et al. Promoter Hypermethylation Frequency and BRAF Mutations Distinguish Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colon Cancer from Sporadic MSI-H Colon Cancer. Fam. Cancer 2004, 3, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, R.P.; Vissers, L.E.; Venkatachalam, R.; Bodmer, D.; Hoenselaar, E.; Goossens, M.; Haufe, A.; Kamping, E.; Niessen, R.C.; Hogervorst, F.B.; et al. Recurrence and variability of germline EPCAM deletions in Lynch syndrome. Hum. Mutat. 2011, 32, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niessen, R.C.; Hofstra, R.M.W.; Westers, H.; Lightenberg, M.J.L; Kooi, K.; Jager, P.O.J; Groote, M.L. Dijikhuizen, T. ; Olderode-Berends, M.J.W.; Hollema, H.; et al. Germline hypermethylation of MLH1 and EPCAM deletions are a frequent cause of Lynch syndrome. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2009, 48, 737–744. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, A.; Nguyen, T.P; Leung, H.C.E.; Nagasaka, T.; Rhees, J.; Hotchkiss, E.; Arnold, M.; Banerji, P.; Koi, M.; Kwok, C.T; et al. De novo constitutional MLH1 epimutations confer early-onset colorectal cancer in two new sporadic Lynch syndrome cases, with derivation of the epimutation on the paternal allele in one. Int J Cancer. 2011, 128, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banchereau, R.; Chitre, A.S.; Scherl, A.; Wu, T.D.; Patil, N.S.; de Almeida, P.; Kadel, I.E.E.; Madireddi, S.; Au-Yeung, A.; Takahashi, C.; et al. Intratumoral CD103+ CD8+ T cells predict response to PD-L1 blockade. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duhen, T.; Duhen, R.; Montler, R.; Moses, J.; Moudgil, T.; de Miranda, N.F.; Goodall, C.P.; Blair, T.C.; Fox, B.A.; McDermott, J.E.; et al. Co-expression of CD39 and CD103 identifies tumor-reactive CD8 T cells in human solid tumors. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichiki, Y.; Ueno, M.; Yanagi, S.; Kanasaki, Y.; Goto, H.; Fukuyama, T.; Mikami, S.; Nakanishi, K.; Ishida, T. An analysis of the immunological tumor microenvironment of primary tumors and regional lymph nodes in squamous cell lung cancer. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 3520–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichiki, Y.; Fukuyama, T.; Ueno, M.; Kanasaki, Y.; Goto, H.; Takahashi, M.; Mikami, S.; Kobayashi, N.; Nakanishi, K.; Hayashi, S.; et al. Immune profile analysis of peripheral blood and tumors of lung cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2022, 11, 2192–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichiki, Y.; Takenoyama, M.; Mizukami, M.; So, T.; Sugaya, M.; Yasuda, M.; So, T.; Hanagiri, T.; Sugio, K.; Yasumoto, K. Simultaneous Cellular and Humoral Immune Response against Mutated p53 in a Patient with Lung Cancer. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 4844–4850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichiki, Y; Shigematsu, Y.; Baba, T.; Shiota, H.; Fukuyama, T.; Nagata, Y.; So, T.; Yasuda, M.; Takenoyama, M.; Yasumoto, K. Development of adoptive immunotherapy with KK-LC-1 specific TCR transduced γδT cells against lung cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 4021–4030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagamu, H.; Kitano, S.; Yamaguchi, O.; Yoshimura, K.; Horimoto, K.; Kitazawa, M.; Fukui, K.; Shiono, A.; Mouri, A.; Nishihara, F.; et al. Cancer Immunol Res 2020, 8, 334–344. [CrossRef]

- Coussens, L.M.; Zitvogel, L.; Palucka, A.K. Neutralizing tumor-promoting chronic inflammation: a magic bullet? Science. 2013, 339, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speiser, D.E.; Utzschneider, D.T.; Oberle, S.G.; Munz, C.; Romero, P.; Zehn, D. T cell differentiation in chronicinfection and cancer: functional adaptation or exhaustion? Nat Rev Immunol. 2014, 14, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fridman, WH.; Pages, F.; Sautes-Fridman, C.; Galon, J. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012, 12, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wouters, M.C.A.; Nelson, B.H. Prognostic Significance of Tumor-Infiltrating B Cells and Plasma Cells in Human Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 6125–6135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipponi, A.; Mercier, M.; Seremet, T.; Baurain, J.-F.; Théate, I.; Oord, J.v.D.; Stas, M.; Boon, T.; Coulie, P.G.; van Baren, N. Neogenesis of Lymphoid Structures and Antibody Responses Occur in Human Melanoma Metastases. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 3997–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germain, C.; Gnjatic, S.; Dieu-Nosjean, M.-C. Tertiary Lymphoid Structure-Associated B Cells are Key Players in Anti-Tumor Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 67–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sautès-Fridman, C.; Petitprez, F.; Calderaro, J.; Fridman, W.H. Tertiary lymphoid structures in the era of cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitprez, F.; de Reyniès, A.; Keung, E.Z.; Chen, T.W.-W.; Sun, C.-M.; Calderaro, J.; Jeng, Y.-M.; Hsiao, L.-P.; Lacroix, L.; Bougoüin, A.; et al. B cells are associated with survival and immunotherapy response in sarcoma. Nature 2020, 577, 556–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmink, B.A.; Reddy, S.M.; Gao, J.; Zhang, S.; Basar, R.; Thakur, R.; Yizhak, K.; Sade-Feldman, M.; Blando, J.; Han, G.; et al. B cells and tertiary lymphoid structures promote immunotherapy response. Nature 2020, 577, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, R.; Lauss, M.; Sanna, A.; Donia, M.; Larsen, M.S.; Mitra, S.; Johansson, I.; Phung, B.; Harbst, K.; Vallon-Christersson. J. Nature. 2020, 577, 561–565. [Google Scholar]

- Hori, S.; Nomura, T.; Sakaguchi, S. Control of Regulatory T Cell Development by the Transcription Factor Foxp3. Science 2003, 299, 1057–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.A.; Stephen-Victor, E.; Wang, S.; Rivas, M.N.; Abdel-Gadir, A.; Harb, H.; Cui, Y.; Fanny, M. ; Charbonnier, L-M. ; Fong, J.J.H.; et al. Regulatory T cell-derived TGF-β1 controls multiple checkpoints governing allergy and autoimmunity. Immunity. 2020, 53, 1202–1214e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyara, M.; Sakaguchi, S. Natural regulatory T cells: mechanisms of suppression. Trends Mol. Med. 2007, 13, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, H.; Horikawa, T.; Hara, I.; Fukunaga, A.; Oniki, S.; Oka, M.; Nishigori, C.; Ichihashi, M. In vivo elimination of CD25+ regulatory T cells leads to tumor rejection of B16F10 melanoma, when combined with interleukin-12 gene transfer. Exp. Dermatol. 2004, 13, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannull, J.; Su, Z.; Rizzieri, D.; Yang, B.K.; Coleman, D.; Yancey, D.; Zhang, A.; Dahm, P.; Chao, N.; Gilboa, E.; et al. Enhancement of vaccine-mediated antitumor immunity in cancer patients after depletion of regulatory T cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 3623–3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, K.; Onishi, Y.; Martin, P.P.; Tamaguchi, T.; Miyara, M.; Fehervari, Z.; Nomura, T.; Sakaguchi, S. CTLA-4 control over Foxp3+ regulatory T cell function. Science. 2008, 322, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smyth, M.J.; Hayakawa, Y.; Takeda, K.; Yagita, H. New aspects of natural-killer-cell surveillance and therapy of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 211, 850–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos-Martín, Y.; del Moral, M.G.; Gozalbo-López, B.; Suela, J.; Martínez-Naves, E. Expression of Human CD1d Molecules Protects Target Cells from NK Cell-Mediated Cytolysis. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 7297–7305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, S.; Groh, V.; Wu, J.; Steinle, A.; Phillips, J.H.; Lanier, L.L.; Spies, T. Activation of NK Cells and T Cells by NKG2D, a Receptor for Stress-Inducible MICA. Science 1999, 285, 727–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armeanu, S.; Bitzer, M.; Lauer, U.M.; Venturelli, S.; Pathil, A.; Krusch, M.; Kaiser, S.; Jobst, J.; Smirnow, I.; Wagner, A.; et al. Natural Killer Cell–Mediated Lysis of Hepatoma Cells via Specific Induction of NKG2D Ligands by the Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor Sodium Valproate. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 6321–6329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skov, S.; Pedersen, M.T.; Andresen, L.; Straten, P.T.; Woetmann, A.; Ødum, N. Cancer Cells Become Susceptible to Natural Killer Cell Killing after Exposure to Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors Due to Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3–Dependent Expression of MHC Class I–Related Chain A and B. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 11136–11145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khong, H.T.; Restifo, N.P. Natural selection of tumor variants in the generation of ‘tumor escape’ phenotypes. Nat Immunol. 2002, 3, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moretta, L.; Bottino, C.; Pende, D.; Vitale, M.; Mingari, M.; Moretta, A. Different checkpoints in human NK activation. Trends Immunol. 2004, 25, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, T.; Hanagiri, T.; Ichiki, Y.; Kuroda, K.; Shigematsu, Y.; Mizukami, M.; Sugaya, M.; Takenoyama, M.; Sugio, K.; Yasumoto, K. Lack and restoration of sensitivity of lung cancer cells to cellular attack with special reference to expression of human leukocyte antigen class I and/or major histocompatibility complex class I chain related molecules A/B. Cancer Sci. 2007, 98, 1795–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimasaki, N.; Jain, A.; Campana, D. NK cells for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfrey, D.I.; Le Nours, J.; Andrews, D.M.; Uldrich, A.P.; Rossjohn, J. Unconventional T Cell Targets for Cancer Immunotherapy. Immunity 2018, 48, 453–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, S.; Shimizu, K.; Kronenberg, M.; Steinman, R.M. Prolonged IFN-gamma-producing NKT response induced with alpha-galactosylceramide-loaded DCs. Nat Immunol. 2002, 3, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, S.-I.; Shimizu, K.; Smith, C.; Bonifaz, L.; Steinman, R.M. Activation of Natural Killer T Cells by α-Galactosylceramide Rapidly Induces the Full Maturation of Dendritic Cells In Vivo and Thereby Acts as an Adjuvant for Combined CD4 and CD8 T Cell Immunity to a Coadministered Protein. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 198, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K.; Kurosawa, Y.; Taniguchi, M.; Steinman, R.M.; Fujii, S.-i. Cross-presentation of glycolipid from tumor cells loaded with α-galactosylceramide leads to potent and long-lived T cell–mediated immunity via dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2007, 204, 2641–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayday, A. Gammadelta T cells and the lymphoid stress-surveillance response. Immunity. 2009, 31, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, J.; Murakawa, T.; Fukami, T.; Goto, S.; Kaneko, T.; Yoshida, Y.; Takamoto, S.; Kakimi, K. A phase I study of adoptive immunotherapy for recurrent non-small-cell cancer patients with autologous gammadelta T cells. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010, 37, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, M. ; J. ; Nakajima, J.; Murakawa, T.; Fukami, M.; Yoshida, Y.; Murayama, T.; Takamoto, S.; Matsushita, H.; Kakimi, K. Adoptive immunotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer using zoledronate-expanded γδT cells: aphase I clinical study. Immunother. 2011, 34, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Lagoudas, G.K.; Zhao, C.; Bullman, S.; Bhutkar, A.; Hu, B.; Ameh, S.; Sandel, D.; Liang, X.S.; Mazzilli, S.; Whary, M.T.; et al. Commensal microbiota promote lung cancer development via γδ T cell. Cell. 2019, 176, 998–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noy, R.; Pollard, J.W. Tumor-associated macrophages: From mechanisms to therapy. Immunity 2014, 41, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani, A.; Sica, A. Macrophages, innate immunity and cancer: balance, tolerance, and diversity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2010, 22, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, S.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, B.; Deng, Y.; Wei, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wen, L.; et al. Irradiated tumour cell-derived microparticles upregulate MHC-I expression in cancer cells via DNA double-strand break repair pathway. Cancer Lett. 2024, 592, 216898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Sun, Y.; Tian, Y.; Lu, L.; Dai, X.; Meng, J.; Huang, J.; He, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Irradiated tumor cell–derived microparticles mediate tumor eradication via cell killing and immune reprogramming. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaay9789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goc, J.; Germain, C.; Bourgais, T.K.D.; Lupo, A.; Klein, C.; Knockaert, S.; Chaisemartin, L.; Ouakrim, H.; Becht, E.; Alifano, M. Dendritic cells in tumor-associated tertial lymphoid structures signal a Th1 cytotoxic immune contexture and license the positive prognostic value of infiltrating CD8+ T cell. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutertre, C.A.; Wang, L.F. ; Ginhoux. Aligning bona fide dendritic cell populationa cross species. Cell Immunol. 2014, 291, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniffa, M.; Collin, M.; Ginhoux, F. Ontogeny and Functional Specialization of Dendritic Cells in Human and Mouse. Adv. Immunol. 2013, 120, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavin, Y.; Kobayashi, S.; Leader, A.; Amir, E.D.; Elefant, N.; Bigenwald, C.; Remark, R.; Sweeney, R.; Becker, C.D.; Levine, J.H.; et al. Innate Immune Landscape in Early Lung Adenocarcinoma by Paired Single-Cell Analyses. Cell 2017, 169, 750–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossche, J.V.D.; De Laere, M.; Deschepper, K.; Germonpré, P.; Valcke, Y.; Lamont, J.; Stein, B.; Van Camp, K.; Germonpré, C.; Nijs, G.; et al. Integration of the PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab and WT1/DC vaccination into standard-of-care first-line treatment for patients with epithelioid malignant pleural mesothelioma—Protocol of the Immuno-MESODEC study. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0307204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land, F.R.v. .; Willemsen, M.; Bezemer, K.; van der Burg, S.H.; Bosch, T.P.v.D.; Doukas, M.; Fellah, A.; Kolijn, P.M.; Langerak, A.W.; Moskie, M.; et al. Dendritic Cell–Based Immunotherapy in Patients With Resected Pancreatic Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 3083–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veglia, F.; Perego, M.; Gabrilovich, D. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells coming of age. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hengesbach, L.M.; Hoag, K.A. Physiological Concentrations of Retinoic Acid Favor Myeloid Dendritic Cell Development over Granulocyte Development in Cultures of Bone Marrow Cells from Mice. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 2653–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nefedova, Y.; Nagaraj, S.; Rosenbauer, A.; Muro-Cacho, C.; Sebti, S. M.; Gabrilovich, D. I. Regulation of dendritic cell differentiation and antitumor immune response in cancer by pharmacologic-selective inhibition of the Janus-activated kinase 2/signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 pathway. Cancer Research. 2005, 65, 9525–9535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortylewski, M.; Kujawski, M.; Wang, T.; Wei, S.; Zhang, S.; Pilon-Thomas, S.; Niu, G.; Kay, H.; Mulé, J.; Kerr, W.G.; et al. Inhibiting Stat3 signaling in the hematopoietic system elicits multicomponent antitumor immunity. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 1314–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, E.; Kapoor, V.; Jassar, A.S.; Kaiser, L.R.; Albelda, S.M. ; Gemcitabine selectively eliminates splenic Gr-1+ / CD11b+ myeloid suppressor cells in tumor-bearing animals and enhances antitumor immune activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2005, 15, 6713–6721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.-Y.; Ma, G.; Weber, K.J.; Ozao-Choy, J.; Wang, G.; Yin, B.; Divino, C.M.; Chen, S.-H. Immune Stimulatory Receptor CD40 Is Required for T-Cell Suppression and T Regulatory Cell Activation Mediated by Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Cancer. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aruga, A.; Aruga, E.; Cameron, M.J.; E Chang, A. Different cytokine profiles released by CD4+ and CD8+ tumor-draining lymph node cells involved in mediating tumor regression. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1997, 61, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe-Querol, E.; Rosales, C. Neutrophils in Cancer: Two Sides of the Same Coin. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 2015, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canli. ; Nicolas, A.M.; Gupta, J.; Finkelmeier, F.; Goncharova, O.; Pesic, M.; Neumann, T.; Horst, D.; Löwer, M.; Sahin, U.; et al. Myeloid Cell-Derived Reactive Oxygen Species Induce Epithelial Mutagenesis. Cancer Cell 2017, 32, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, A.M.; Rzymkiewicz, D.M.; Ji, H.; Gregory, A.D.; Egea, E.E.; Metz, H.E.; Stolz, D.B.; Land, S.R.; Marconcini, L.A.; Kliment, C.R.; et al. Neutrophil elastase-mediated degradation of IRS-1 accelerates lung tumor growth. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nozawa, H.; Chiu, C.; Hanahan, D. Infiltrating neutrophils mediate the initial angiogenic switch in a mouse model of multistage carcinogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006, 103, 12493–12498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenmeier, C.; Simmons, R.L.; Tohme, S.; Yazdani, H.O. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) in Cancer Metastasis. Cancers 2021, 13, 6131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diem, S.; Schmid, S.; Krapf, M.; Flatz, L.; Born, D.; Jochum, W.; Templeton, A.J.; Früh, M. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte ratio (PLR) as prognostic markers in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with nivolumab. Lung Cancer 2017, 111, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanizaki, J.; Haratani, K.; Hayashi, H.; Chiba, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Yonesaka, K.; Kudo, K.; Kaneda, H.; Hasegawa, Y.; Tanaka, K.; et al. Peripheral Blood Biomarkers Associated with Clinical Outcome in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients Treated with Nivolumab. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2017, 13, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, M.; Hofman, V.; Ortholan, C.; Bonnetaud, C.; Coëlle, C.; Mouroux, J.; Hofman, P. Predictive clinical outcome of the intra-tumoral CD66b-positive neutrophil-to-CD8-positive T-cell ratio in patients with resectable nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer 2012, 118, 1726–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panciera, T.; Azzolin, L.; Cordenonsi, M.; Piccolo, S. Mechanobiology of YAP and TAZ in physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaks, V.; Kong, N.; Werb, Z. The Cancer Stem Cell Niche: How Essential Is the Niche in Regulating Stemness of Tumor Cells? Cell Stem Cell 2015, 16, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, L.; Felipe De Sousa, E.M.; Van Der Heijden, M.; Cameron, K.; De Jong, J.H.; Borovski, T.; Tuynman, J.B.; Todaro, M.; Merz, C.; Rodermond, H.; et al. Wnt activity defines colon cancer stem cells and is regulated by the microenvironment. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, F.; Ege, N.; Grande-Garcia, A.; Hooper, S.; Jenkins, R.P.; Chaudhry, S.I.; Harrington, K.; Williamson, P.; Moeendarbary, E.; Charras, G.; et al. Mechanotransduction and YAP-dependent matrix remodelling is required for the generation and maintenance of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junttila, M.R.; de Sauvage, F.J. Influence of tumour micro-environment heterogeneity on therapeutic response. Nature 2013, 501, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilkes, D.M.; Bajpai, S.; Chaturvedi, P.; Wirtz, D.; Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1) promotes extracellular matrix remodeling under hypoxic conditions by inducing P4HA1, P4HA2 and PLOD2 expression in fibroblasts. J Biol Chem, 2013, 288, 10819–10829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cords, L.; Engler, A.; Heberecker, M.; Ruschoff, J.H.; Moch, H.; Souza, N.; Bodenmiller, B. Cancer-associated fibroblast phenotypes are associated with patient outcome in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2024, 42, 396–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.; Gakhar, N.; Kirtane, K. TCR gene-engineered cell therapy for solid tumors. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Haematol. 2021, 34, 101285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterner, R.C.; Sterner, R.M. CAR-T cell therapy: current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Cui, Y.; Liu, Q.; Chen, S. CAR-T cell therapy for lung cancer: a promising but challenging future. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 4516–4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Wang, B.; Li, J.; Liu, Y. LINC00922 accelerates the proliferation, migration and invasion of lung cancer via the miRNA-204/CXCR4 Axis. Med Sci Monit. 2019, 25, 5075–5086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangadhar, T.; Nandi, S.; Salgia, R. The role of chemokine receptor CXCR4 in lung cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2010, 9, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Fan, W.; Hu, H.; Zhang, L.; Michel, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Jia, L.; Tang, X.; Chen, Y.; et al. MAGE-A1 in lung adenocarcinoma as a promising target of chimeric antigen receptor T cells. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leidner, R.; Silva, N.S.; Huang, H.; Sprott, D.; Zheng, C.; Shih, Y.-P.; Leung, A.; Payne, R.; Sutcliffe, K.; Cramer, J.; et al. Neoantigen T-Cell Receptor Gene Therapy in Pancreatic Cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 2112–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, P.F.; Morgan, R.A.; Feldman, S.A.; Yang, J.C.; Sherry, R.M.; Dudley, M.E.; Wunderlich, J.R.; Nahvi, A.V.; Helman, L.J.; Mackall, C.L.; et al. Tumor Regression in Patients With Metastatic Synovial Cell Sarcoma and Melanoma Using Genetically Engineered Lymphocytes Reactive With NY-ESO-1. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).