Submitted:

23 September 2024

Posted:

23 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

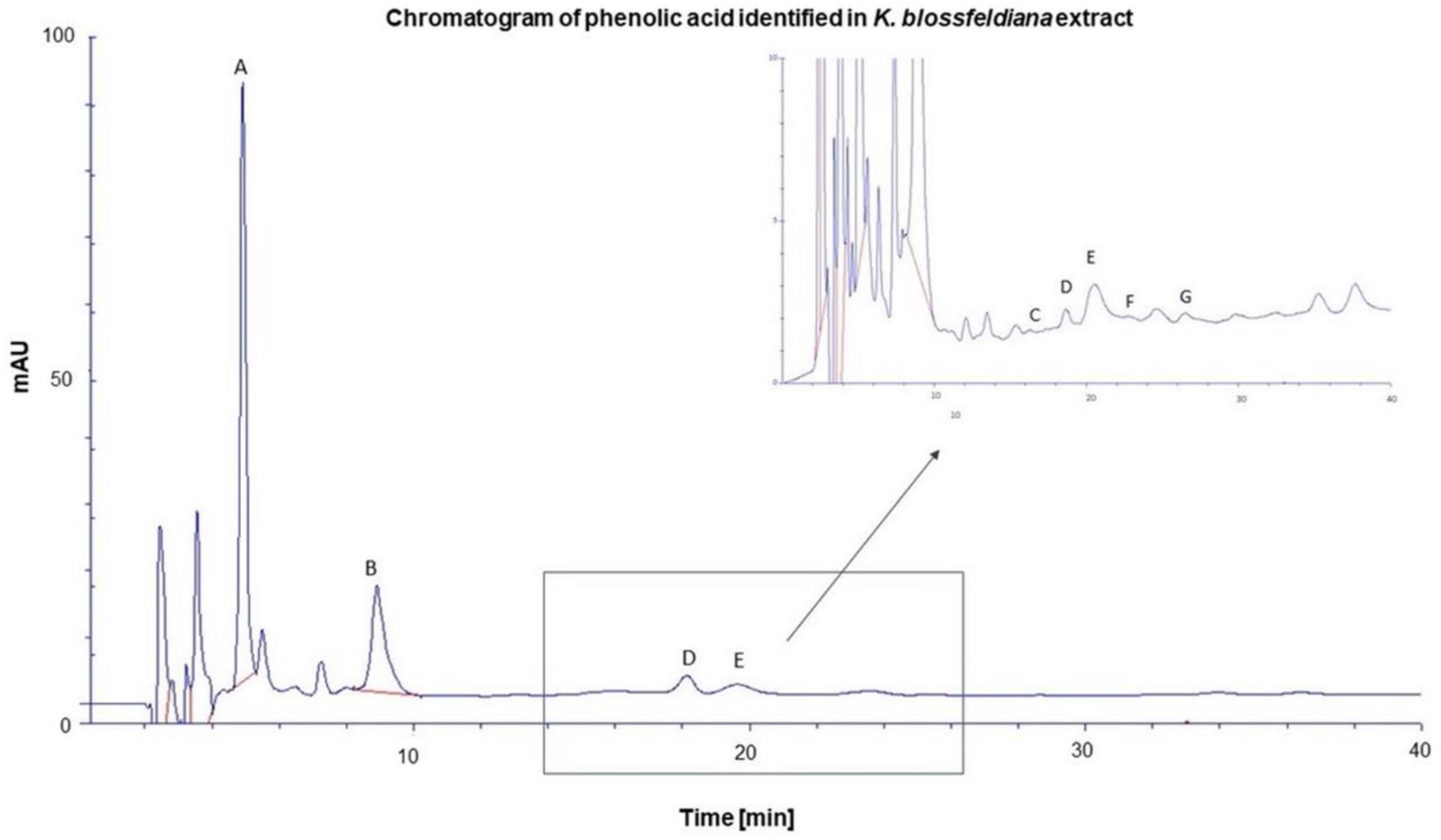

2.1. Phytochemical profiles of K. blossfeldiana

2.2. Biological Activity of Ethanol Extract of K. Blossfeldiana

2.2.1. Antioxidant Activity

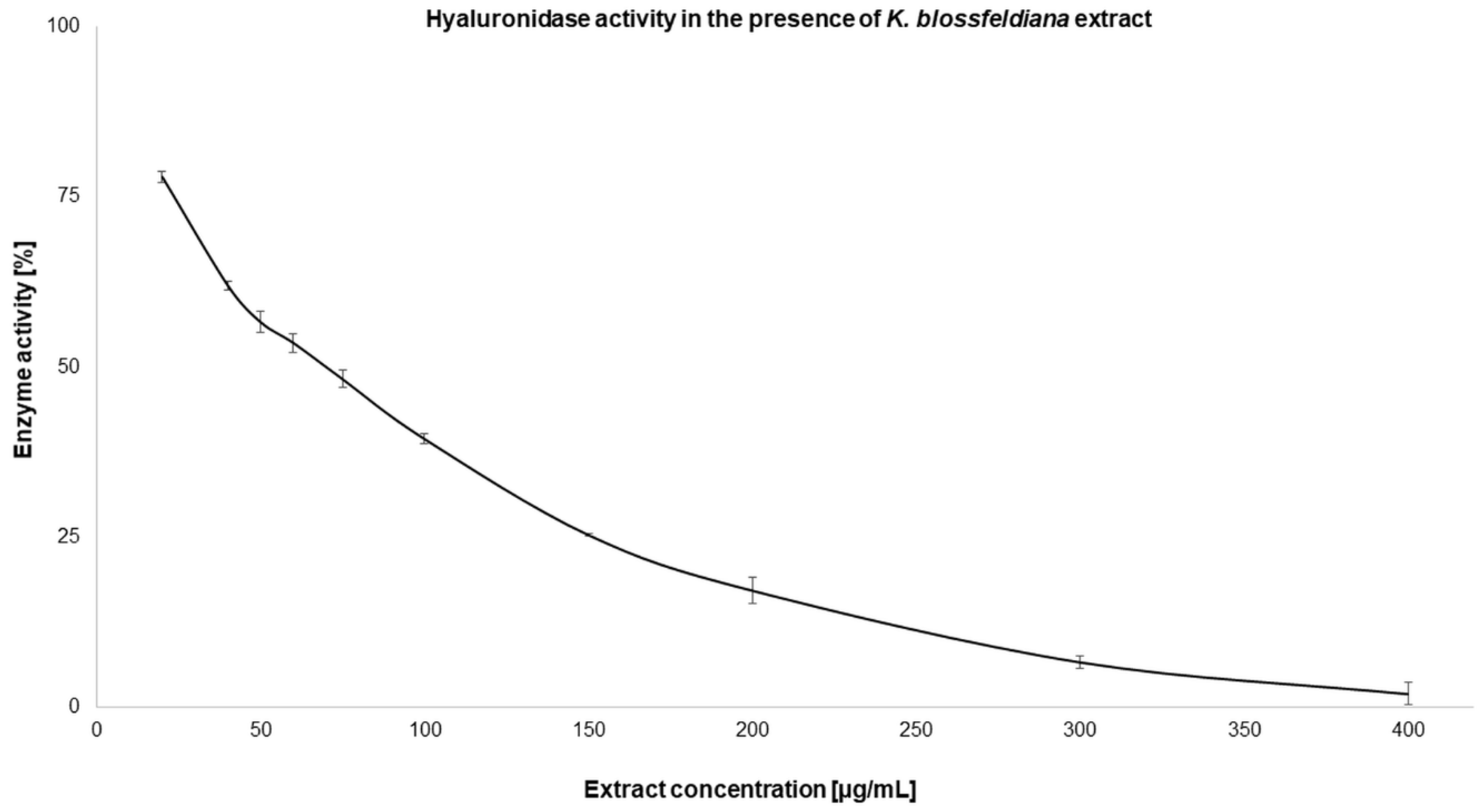

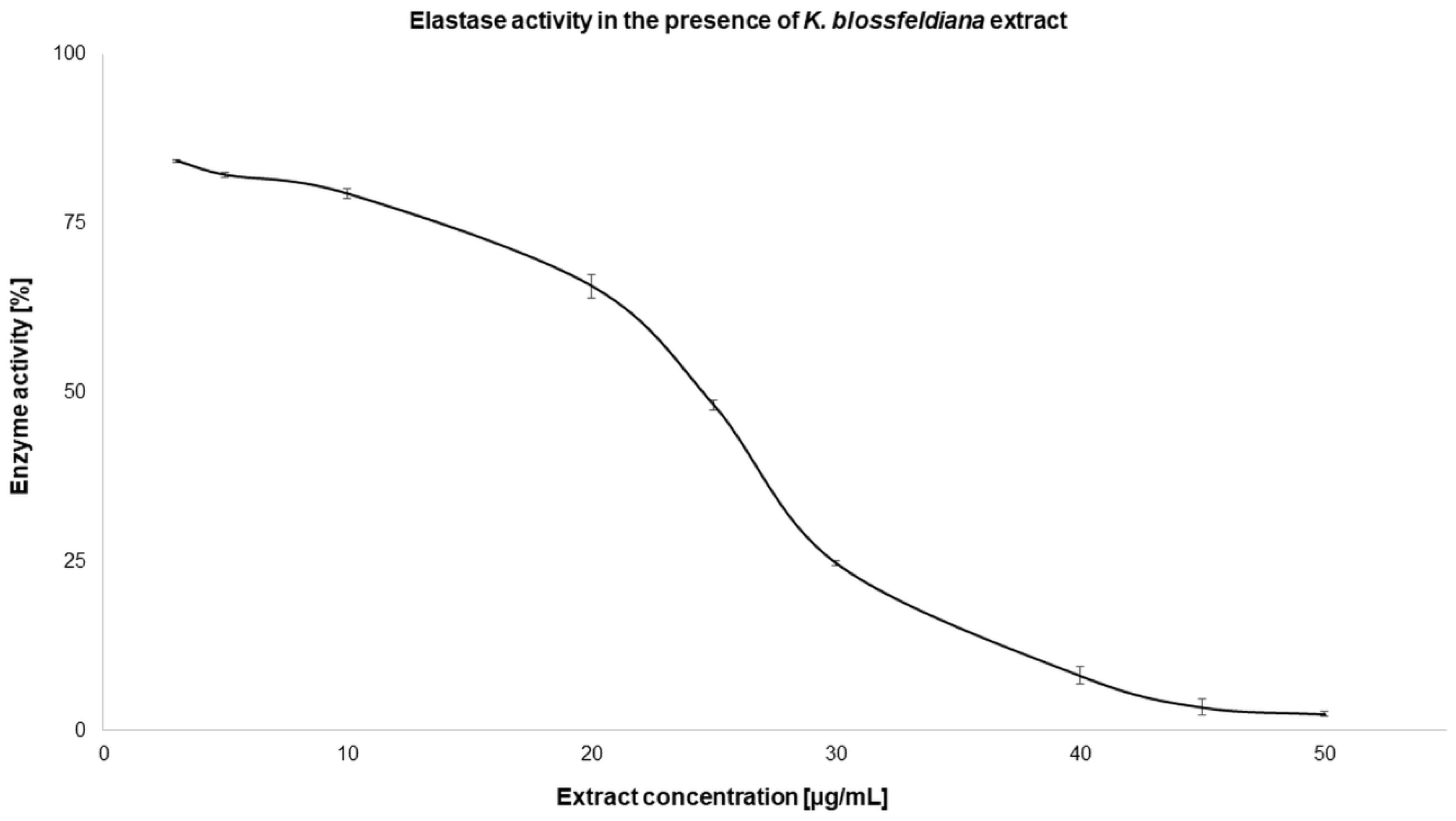

2.2.2. Enzyme Inhibition

2.3. Stability Test of HKB

2.4. Ex Vivo Study with HKB

2.4.1. Permeation Through the Skin

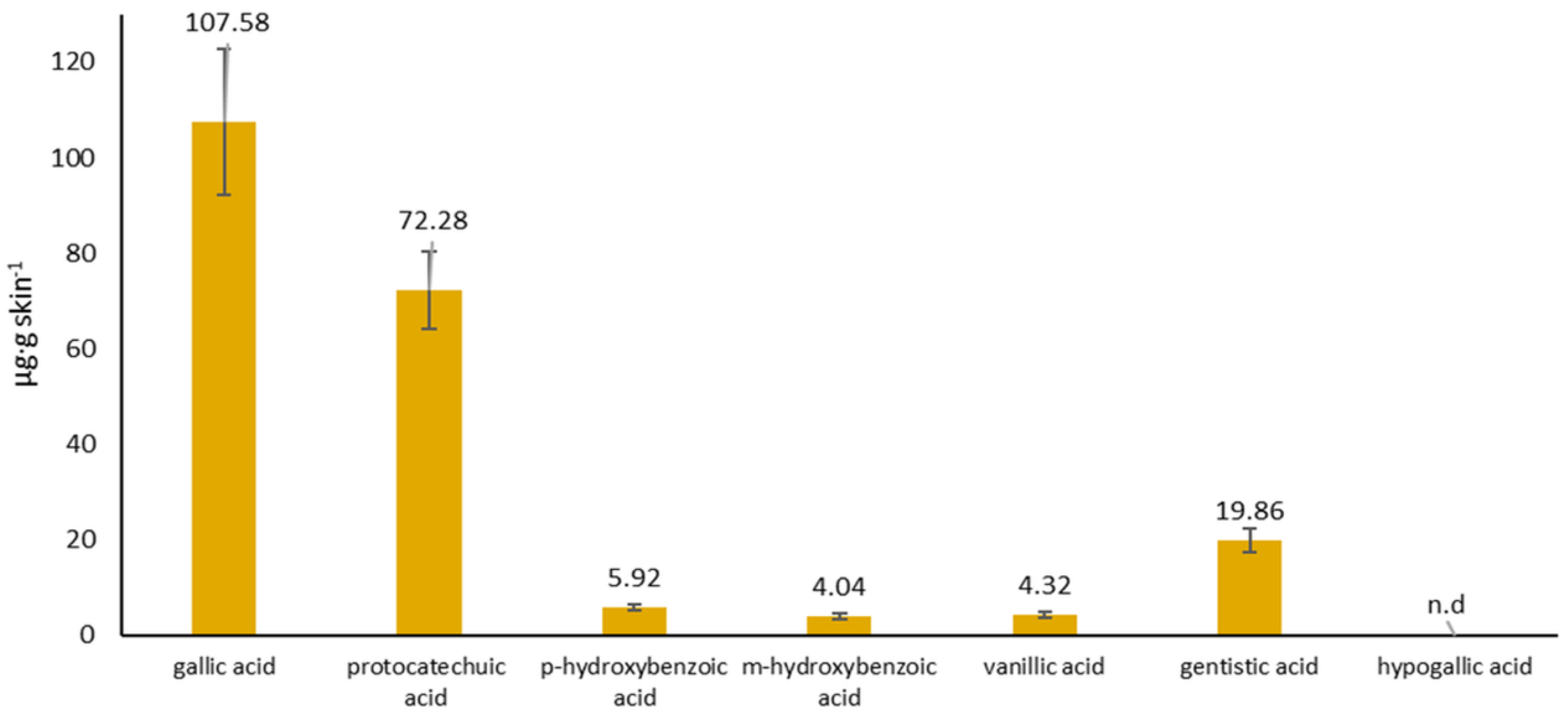

2.4.2. Accumulation in the Skin

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals

4.2. Plant Material and Extraction

4.3. Phytochemical Analysis of K. Blossfeldiana Ethanol Extract

4.4. Antioxidant Tests

4.4.1. DPPH Assay

4.4.2. ABTS Assay

4.4.3. FRAP Assay

4.5. Inhibition of Enzymes

4.5.1. Antihyaluronidase Assay

4.5.2. Antielastase Assay

4.6. Prepared HKB Hydrogel

4.7. Stability of Hydrogel with K. Blossfeldiana Extract

4.8. Ex Vivo Skin Permeation Studies

4.8.1. Human Skin

4.8.2. Permeation Studies

4.9. Accumulation of the Phenolic Acids in the Skin

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sarkar, R.; Kumar, A.; Divya, L.K.; Samanta, S.; Adhikari, D.; Karmakar, S.; Sen, T. Antioxidant Properties of Kalanchoe Blossfeldiana – A Focus on Erythrocyte Membrane Stability and Cytoprotection. Curr. Tradit. Med. 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanowicz-Hajduk, J.; Gucwa, M.; Hajduk, A.; Ochocka, Jr. Kalanchoe Blossfeldiana Extract Induces Cell Cycle Arrest and Necrosis in Human Cervical Cancer Cells. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2019, 15, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanowicz-Hajduk, J.; Hering, A.; Kowalczyk, M.; Hałasa, R.; Gucwa, M.; Ochocka, J.R. Kalanchoe Sp. Extracts—Phytochemistry, Cytotoxic, and Antimicrobial Activities. Plants 2023, 12, 2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldalbahi, A.; Alterary, S.; Ali Abdullrahman Almoghim, R.; Awad, M.A.; Aldosari, N.S.; Fahad Alghannam, S.; Nasser Alabdan, A.; Alharbi, S.; Ali Mohammed Alateeq, B.; Abdulrahman Al Mohsen, A.; et al. Greener Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Characterization and Multifaceted Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assis de Andrade, E.; Machinski, I.; Terso Ventura, A.C.; Barr, S.A.; Pereira, A.V.; Beltrame, F.L.; Strangman, W.; Williamson, R.T. A Review of the Popular Uses, Anatomical, Chemical, and Biological Aspects of Kalanchoe (Crassulaceae): A Genus of Plants Known as “Miracle Leaf”. Molecules 2023, 28, 5574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, A.; Zagórska-Dziok, M.; Perużyńska, M.; Cybulska, K.; Kucharska, E.; Ossowicz-Rupniewska, P.; Piotrowska, K.; Duchnik, W.; Kucharski, Ł.; Sulikowski, T.; et al. Assessment of the Anti-Inflammatory, Antibacterial and Anti-Aging Properties and Possible Use on the Skin of Hydrogels Containing Epilobium Angustifolium L. Extracts. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 896706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.; Zagórska-Dziok, M.; Ossowicz-Rupniewska, P.; Makuch, E.; Duchnik, W.; Kucharski, Ł.; Adamiak-Giera, U.; Prowans, P.; Czapla, N.; Bargiel, P.; et al. Epilobium Angustifolium L. Extracts as Valuable Ingredients in Cosmetic and Dermatological Products. Molecules 2021, 26, 3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossowicz-Rupniewska, P.; Nowak, A.; Klebeko, J.; Janus, E.; Duchnik, W.; Adamiak-Giera, U.; Kucharski, Ł.; Prowans, P.; Petriczko, J.; Czapla, N.; et al. Assessment of the Effect of Structural Modification of Ibuprofen on the Penetration of Ibuprofen from Pentravan® (Semisolid) Formulation Using Human Skin and a Transdermal Diffusion Test Model. Materials 2021, 14, 6808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagórska-Dziok, M.; Sobczak, M. Hydrogel-Based Active Substance Release Systems for Cosmetology and Dermatology Application: A Review. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditta, L.A.; Rao, E.; Provenzano, F.; Sánchez, J.L.; Santonocito, R.; Passantino, R.; Costa, M.A.; Sabatino, M.A.; Dispenza, C.; Giacomazza, D.; et al. Agarose/κ-Carrageenan-Based Hydrogel Film Enriched with Natural Plant Extracts for the Treatment of Cutaneous Wounds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 2818–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagórska-Dziok, M.; Bujak, T.; Ziemlewska, A.; Nizioł-Łukaszewska, Z. Positive Effect of Cannabis Sativa L. Herb Extracts on Skin Cells and Assessment of Cannabinoid-Based Hydrogels Properties. Molecules 2021, 26, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.; Zagórska-Dziok, M.; Ossowicz-Rupniewska, P.; Makuch, E.; Duchnik, W.; Kucharski, Ł.; Adamiak-Giera, U.; Prowans, P.; Czapla, N.; Bargiel, P.; et al. Epilobium Angustifolium L. Extracts as Valuable Ingredients in Cosmetic and Dermatological Products. Molecules 2021, 26, 3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, A.H.; Olsen, C.E.; Møller, B.L. Flavonoids in Flowers of 16 Kalanchoë Blossfeldiana Varieties. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 2829–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmad Darmawan 3’,4’-Dimethoxy Quercetin, a Flavonol Compound Isolated from Kalanchoe Pinnata. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Pryce, R.J. Gallic Acid as a Natural Inhibitor of Flowering in Kalanchoe Blossfeldiana. Phytochemistry 1972, 11, 1911–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briganti, S.; Picardo, M. Antioxidant Activity, Lipid Peroxidation and Skin Diseases. What’s New. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2003, 17, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Han, S.; Gu, Z.; Wu, J. Advances and Impact of Antioxidant Hydrogel in Chronic Wound Healing. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2020, 9, 1901502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, C.; Martí, M.; Barba, C.; Lis, M.; Rubio, L.; Coderch, L. Skin Penetration and Antioxidant Effect of Cosmeto-Textiles with Gallic Acid. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2016, 156, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertges, F.S.; da Penha Henriques do Amaral, M.; Rodarte, M.P.; Vieira Fonseca, M.J.; Sousa, O.V.; Pinto Vilela, F.M.; Alves, M.S. Assessment of Chemical Changes and Skin Penetration of Green Arabica Coffee Beans Biotransformed by Aspergillus Oryzae. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 23, 101512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.; Grimshaw, S.; Hoptroff, M.; Paterson, S.; Arnold, D.; Cawley, A.; Adams, S.E.; Falciani, F.; Dadd, T.; Eccles, R.; et al. Alteration of Barrier Properties, Stratum Corneum Ceramides and Microbiome Composition in Response to Lotion Application on Cosmetic Dry Skin. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zillich, O.V.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U.; Hasenkopf, K.; Eisner, P.; Kerscher, M. Release and in Vitro Skin Permeation of Polyphenols from Cosmetic Emulsions. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2013, 35, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, A.; Cybulska, K.; Makuch, E.; Kucharski, Ł.; Różewicka-Czabańska, M.; Prowans, P.; Czapla, N.; Bargiel, P.; Petriczko, J.; Klimowicz, A. In Vitro Human Skin Penetration, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity of Ethanol-Water Extract of Fireweed (Epilobium angustifolium L.). Molecules 2021, 26, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sae Yoon, A.; Sakdiset, P. Development of Microemulsions Containing Glochidion Wallichianum Leaf Extract and Potential for Transdermal and Topical Skin Delivery of Gallic Acid. Sci. Pharm. 2020, 88, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolai, M.; Mota, J.; Fernandes, A.S.; Pereira, F.; Pereira, P.; P. Reis, C.; Robles Velasco, M.V.; Baby, A.R.; Rosado, C.; Rijo, P. Assessment of the Potential Skin Application of Plectranthus Ecklonii Benth. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavan, A.; Colobatiu, L.; Hanganu, D.; Bogdan, C.; Olah, N.; Achim, M.; Mirel, S. Development and Evaluation of Hydrogel Wound Dressings Loaded with Herbal Extracts. Processes 2022, 10, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagórska-Dziok, M.; Ziemlewska, A.; Mokrzyńska, A.; Nizioł-Łukaszewska, Z.; Wójciak, M.; Sowa, I. Evaluation of the Biological Activity of Hydrogel with Cornus Mas L. Extract and Its Potential Use in Dermatology and Cosmetology. Molecules 2023, 28, 7384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žilius, M.; Ramanauskienė, K.; Juškaitė, V.; Briedis, V. Formulation of Propolis Phenolic Acids Containing Microemulsions and Their Biopharmaceutical Characterization. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2016, 2016, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ossowicz-Rupniewska, P.; Bednarczyk, P.; Nowak, M.; Nowak, A.; Duchnik, W.; Kucharski, Ł.; Klebeko, J.; Świątek, E.; Bilska, K.; Rokicka, J.; et al. Evaluation of the Structural Modification of Ibuprofen on the Penetration Release of Ibuprofen from a Drug-in-Adhesive Matrix Type Transdermal Patch. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, C.; Lucas, R.; Barba, C.; Marti, M.; Rubio, L.; Comelles, F.; Morales, J.C.; Coderch, L.; Parra, J.L. Skin Delivery of Antioxidant Surfactants Based on Gallic Acid and Hydroxytyrosol. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2015, 67, 900–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro e Silva, S.; Calixto, G.; Cajado, J.; de Carvalho, P.; Rodero, C.; Chorilli, M.; Leonardi, G. Gallic Acid-Loaded Gel Formulation Combats Skin Oxidative Stress: Development, Characterization and Ex Vivo Biological Assays. Polymers 2017, 9, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Pei, J.; Zheng, Y.; Miao, Y.; Duan, B.; Huang, L. Gallic Acid: A Potential Anti-Cancer Agent. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2022, 28, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sguizzato, M.; Valacchi, G.; Pecorelli, A.; Boldrini, P.; Simelière, F.; Huang, N.; Cortesi, R.; Esposito, E. Gallic Acid Loaded Poloxamer Gel as New Adjuvant Strategy for Melanoma: A Preliminary Study. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 185, 110613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, A.P.; John, A.A.; Vellayappan, M.V.; Balaji, A.; Jaganathan, S.K.; Supriyanto, E.; Yusof, M. Gallic Acid: Prospects and Molecular Mechanisms of Its Anticancer Activity. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 35608–35621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.; Ferreira, C.; Saavedra, M.J.; Simões, M. Antibacterial Activity and Mode of Action of Ferulic and Gallic Acids Against Pathogenic Bacteria. Microb. Drug Resist. 2013, 19, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyvani-Ghamsari, S.; Rahimi, M.; Khorsandi, K. An Update on the Potential Mechanism of Gallic Acid as an Antibacterial and Anticancer Agent. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 5856–5872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manosroi, A.; Jantrawut, P.; Akihisa, T.; Manosroi, W.; Manosroi, J. In Vitro and in Vivo Skin Anti-Aging Evaluation of Gel Containing Niosomes Loaded with a Semi-Purified Fraction Containing Gallic Acid from Terminalia Chebula Galls. Pharm. Biol. 2011, 49, 1190–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liudvytska, O.; Ponczek, M.B.; Ciesielski, O.; Krzyżanowska-Kowalczyk, J.; Kowalczyk, M.; Balcerczyk, A.; Kolodziejczyk-Czepas, J. Rheum Rhaponticum and Rheum Rhabarbarum Extracts as Modulators of Endothelial Cell Inflammatory Response. Nutrients 2023, 15, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, M.A.; Jüppner, J.; Bajdzienko, K.; Giavalisco, P. Protocol: A Fast, Comprehensive and Reproducible One-Step Extraction Method for the Rapid Preparation of Polar and Semi-Polar Metabolites, Lipids, Proteins, Starch and Cell Wall Polymers from a Single Sample. Plant Methods 2016, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakdawattanakul, R.; Panapisal, P.; Tansirikongkol, A.A. Comparative in Vitro Anti-Aging Activities of Phyllanthus Emblica L. Extract, Manilkara Sapota L. Extract and Its Combination. Thai J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 40, 108–111. [Google Scholar]

- Geeta, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Widodo, W.S.; Widowati, W.; Ginting, C.N.; Lister, I.N.E.; Armansyah, A.; Girsang, E. Comparison of Antioxidant and Anti-Collagenase Activity of Genistein and Epicatechin. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahorun, T.; Luximon-Ramma, A.; Crozier, A.; Aruoma, O.I. Total Phenol, Flavonoid, Proanthocyanidin and Vitamin C Levels and Antioxidant Activities of Mauritian Vegetables. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2004, 84, 1553–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaessler, A.; Nourrisson, M.-R.; Duflos, M.; Jose, J. Indole Carboxamides Inhibit Bovine Testes Hyaluronidase at pH 7.0 and Indole Acetamides Activate the Enzyme at pH 3.5 by Different Mechanisms. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2008, 23, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hering, A.; Stefanowicz-Hajduk, J.; Hałasa, R.; Olech, M.; Nowak, R.; Kosiński, P.; Ochocka, J.R. Polyphenolic Characterization, Antioxidant, Antihyaluronidase and Antimicrobial Activity of Young Leaves and Stem Extracts from Rubus caesius L. Molecules 2022, 27, 6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thring, T.S.; Hili, P.; Naughton, D.P. Anti-Collagenase, Anti-Elastase and Anti-Oxidant Activities of Extracts from 21 Plants. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2009, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochocka, R.; Hering, A.; Stefanowicz–Hajduk, J.; Cal, K.; Barańska, H. The Effect of Mangiferin on Skin: Penetration, Permeation and Inhibition of ECM Enzymes. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0181542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthachan, T.; Tewtrakul, S. Anti-Inflammatory and Wound Healing Effects of Gel Containing Kaempferia Marginata Extract. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 240, 111964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badran, M.M.; Kuntsche, J.; Fahr, A. Skin Penetration Enhancement by a Microneedle Device (Dermaroller®) in Vitro: Dependency on Needle Size and Applied Formulation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 36, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fibrich, B.; Gao, X.; Puri, A.; Banga, A.K.; Lall, N. In Vitro Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Skin Permeation of Myrsine Africana and Its Isolated Compound Myrsinoside B. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 10, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossowicz-Rupniewska, P.; Rakoczy, R.; Nowak, A.; Konopacki, M.; Klebeko, J.; Świątek, E.; Janus, E.; Duchnik, W.; Wenelska, K.; Kucharski, Ł.; et al. Transdermal Delivery Systems for Ibuprofen and Ibuprofen Modified with Amino Acids Alkyl Esters Based on Bacterial Cellulose. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compounds categories | Total number of compounds in each group | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carbohydrate | 1 |

| 2 | Organic acid | 8 |

| 3 | Acyclic alcohol glycoside | 9 |

| 4 | Acyclic nitrile glycoside | 7 |

| 5 | Gallic acid derivative | 10 |

| 6 | Aminoacid | 3 |

| 7 | Acyclic acid glycoside | 2 |

| 8 | Benzoic acid derivative | 9 |

| 9 | Acetophenone derivative | 1 |

| 10 | Phenylpropanoid derivative | 12 |

| 11 | Phenol derivative | 3 |

| 12 | Flavanole | 6 |

| 13 | Sesquiterpenoid derivative | 1 |

| 14 | Dimeric proanthocyanidin | 5 |

| 15 | Megastigmane glycoside | 3 |

| 16 | Dimeric iridoid derivative | 1 |

| 17 | Monoterpene derivative | 1 |

| 18 | Bicyclo[3.1.1] glycoside | 1 |

| 19 | Phenylethane glycoside | 1 |

| 20 | Flavonole glycoside | 5 |

| 21 | Fatty acid glycoside | 1 |

| 22 | Iridoid glycoside | 1 |

| 23 | Lipid | 2 |

| 24 | Unidentified | 50 |

| Total identified compounds | 93 | |

| Phenolic acid | µg·mL extract-1 |

|---|---|

| gallic acid | 284.74 ± 15.64 |

| protocatechuic acid | 74.35 ± 4.30 |

| p-hydroxybenzoic acid | 11.10 ± 0.43 |

| m-hydroxybenzoic acid | 0.85 ± 0.11 |

| vanillic acid | 12.63 ± 0.33 |

| gentistic acid | 9.10 ± 0.39 |

| hypogallic acid | 1.95 ± 0.07 |

| Test | IC50 [µg/mL] | |

|---|---|---|

| K. blossfeldiana ethanol extract | Ascorbic acid | |

| DPPH | 7.72 ± 0.09* | 15.23 ± 0.76 |

| ABTS | 4.21 ± 0.32* | 7.38 ± 0.09 |

| FRAP | 11.25 ± 0.17* | 5.29 ± 0.21 |

| Enzymatic inhibition assay | IC50 [µg/mL] | |

|---|---|---|

| K. blossfeldiana ethanol extract | Oleanolic acid | |

| Hyaluronidase | 77.31 ± 2.44* | 49.33 ± 1.35 |

| Elastase | 26.8 ± 0.13* | 17.25 ± 0.27 |

| Time (h) |

Gallic acid | Protocatechuic acid | p-Hydroxybenzoic acid | m-Hydroxybenzoic acid | Vanillic acid | Gentistic acid | Hypogallic acid | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (µg·cm-2) | ||||||||||

| 1 | 5.59 ± 0.52 |

n.d. |

n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |||

| 2 | 7.97 ± 0.87 |

8.01 ± 1.68 | n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |||

| 3 | 12.31 ± 0.56 | 9.57 ± 3.06 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

n.d. |

|||

| 5 | 24.35 ± 1.36 | 23.38 ± 2.27 | n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. | n.d. | |||

| 8 | 51.70 ± 3.44 | 40.96 ± 2.67 | 4.27 ± 1.27 | 7.19 ± 0.36 | 8.95 ± 1.00 |

n.d. |

n.d. |

|||

| 24 | 249.73 ± 13.69 | 97.55 ± 5.31 | 9.96 ± 2.31 | 4.13 ± 0.56 | 15.41 ± 0.55 | 7.18 ± 0.28 | n.d. |

|||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).