Submitted:

20 September 2024

Posted:

24 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Safety of Sputum Induction in Children

Tolerance of Sputum Induction in Children

Side Effects of Sputum Induction in Children

Utilization of Sputum Induction in Children with Respiratory Diseases

- 1.

- Asthma

- 2.

- Cystic Fibrosis

- 3.

- Pneumonia

- 4.

- Opportunistic Infections in Immunocompromised Children

- 5.

- Pulmonary tuberculosis

- 6.

- Other respiratory diseases

Conclusion & Future Directions

Author Contributions

References

- Pitchenik, A.E.; Ganjei, P.; Torres, A.; Evans, D.A.; Rubin, E.; Baier, H. Sputum examination for the diagnosis of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis 1986, 133, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickerman, H.A.; Sproul, E.E.; Barach, A.L. An aerosol method of producing bronchial secretions in human subjects: a clinical technic for the detection of lung cancer. Dis Chest 1958, 33, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pin, I.; Gibson, P.G.; Kolendowicz, R.; Girgis-Gabardo, A.; Denburg, J.A.; Hargreave, F.E.; Dolovich, J. Use of induced sputum cell counts to investigate airway inflammation in asthma. Thorax 1992, 47, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavord, I.D.; Pizzichini, M.M.; Pizzichini, E.; Hargreave, F.E. The use of induced sputum to investigate airway inflammation. Thorax 1997, 52, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanevello, A.; Migliori, G.B.; Sharara, A.; Ballardini, L.; Bridge, P.; Pisati, P.; Neri, M.; Ind, P.W. Induced sputum to assess airway inflammation: a study of reproducibility. Clin Exp Allergy 1997, 27, 1138–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, P.G.; Henry, R.L.; Thomas, P. Noninvasive assessment of airway inflammation in children: induced sputum, exhaled nitric oxide, and breath condensate. Eur Respir J 2000, 16, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gibson, P.G.; Grootendor, D.C.; Henry, R.L.; Pin, I.; Rytila, P.H.; Wark, P.; Wilson, N.; Djukanovic, R. Sputum induction in children. Eur Respir J Suppl 2002, 37, 44s–46s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paggiaro, P.L.; Chanez, P.; Holz, O.; Ind, P.W.; Djukanovic, R.; Maestrelli, P.; Sterk, P.J. Sputum induction. Eur Respir J Suppl 2002, 37, 3s–8s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djukanovic, R.; Sterk, P.J.; Fahy, J.V.; Hargreave, F.E. Standardised methodology of sputum induction and processing. Eur Respir J Suppl 2002, 37, 1s–2s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fireman, E. Induced sputum as a diagnostic tactic in pulmonary diseases. Isr Med Assoc J 2003, 5, 524–527. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, N.M.; Bridge, P.; Spanevello, A.; Silverman, M. Induced sputum in children: feasibility, repeatability, and relation of findings to asthma severity. Thorax 2000, 55, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagel, S.D.; Kapsner, R.; Osberg, I.; Sontag, M.K.; Accurso, F.J. Airway inflammation in children with cystic fibrosis and healthy children assessed by sputum induction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001, 164, 1425–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brightling, C.E. Clinical applications of induced sputum. Chest 2006, 129, 1344–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conde, M.B.; Soares, S.L.; Mello, F.C.; Rezende, V.M.; Almeida, L.L.; Reingold, A.L.; Daley, C.L.; Kritski, A.L. Comparison of sputum induction with fiberoptic bronchoscopy in the diagnosis of tuberculosis: experience at an acquired immune deficiency syndrome reference center in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000, 162, 2238–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suri, R.; Marshall, L.J.; Wallis, C.; Metcalfe, C.; Shute, J.K.; Bush, A. Safety and use of sputum induction in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2003, 35, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forton, J. Induced sputum in young healthy children with cystic fibrosis. Paediatr Respir Rev 2015, 16 Suppl 1, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zar, H.J.; Hanslo, D.; Apolles, P.; Swingler, G.; Hussey, G. Induced sputum versus gastric lavage for microbiological confirmation of pulmonary tuberculosis in infants and young children: a prospective study. Lancet 2005, 365, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochmann, A.; Artusio, L.; Robson, K.; Nagakumar, P.; Collins, N.; Fleming, L.; Bush, A.; Saglani, S. Infection and inflammation in induced sputum from preschool children with chronic airways diseases. Pediatr Pulmonol 2016, 51, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchetti, K.; Tame, J.D.; Paisey, C.; Thia, L.P.; Doull, I.; Howe, R.; Mahenthiralingam, E.; Forton, J.T. The CF-Sputum Induction Trial (CF-SpIT) to assess lower airway bacterial sampling in young children with cystic fibrosis: a prospective internally controlled interventional trial. Lancet Respir Med 2018, 6, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLuca, A.N.; Hammitt, L.L.; Kim, J.; Higdon, M.M.; Baggett, H.C.; Brooks, W.A.; Howie, S.R.C.; Deloria Knoll, M.; Kotloff, K.L.; Levine, O.S.; et al. Safety of Induced Sputum Collection in Children Hospitalized With Severe or Very Severe Pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 2017, 64, S301–S308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, H.A.; Apolles, P.; de Villiers, P.J.; Zar, H.J. Sputum induction for microbiological diagnosis of childhood pulmonary tuberculosis in a community setting. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011, 15, 1185–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lex, C.; Payne, D.N.; Zacharasiewicz, A.; Li, A.M.; Wilson, N.M.; Hansel, T.T.; Bush, A. Sputum induction in children with difficult asthma: safety, feasibility, and inflammatory cell pattern. Pediatr Pulmonol 2005, 39, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joel, D.R.; Steenhoff, A.P.; Mullan, P.C.; Phelps, B.R.; Tolle, M.A.; Ho-Foster, A.; Mabikwa, V.; Kgathi, B.G.; Ncube, R.; Anabwani, G.M. Diagnosis of paediatric tuberculosis using sputum induction in Botswana: programme description and findings. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2014, 18, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boeck, K.; Alifier, M.; Vandeputte, S. Sputum induction in young cystic fibrosis patients. Eur Respir J 2000, 16, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.D.; Hankin, R.; Simpson, J.; Gibson, P.G.; Henry, R.L. The tolerability, safety, and success of sputum induction and combined hypertonic saline challenge in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001, 164, 1146–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, X.; Zou, W.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Hu, S. Global trends in the incidence and mortality of asthma from 1990 to 2019: An age-period-cohort analysis using the global burden of disease study 2019. Front Public Health 2022, 10, 1036674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covar, R.A.; Spahn, J.D.; Martin, R.J.; Silkoff, P.E.; Sundstrom, D.A.; Murphy, J.; Szefler, S.J. Safety and application of induced sputum analysis in childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004, 114, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drews, A.C.; Pizzichini, M.M.M.; Pizzichini, E.; Pereira, M.U.; Pitrez, P.M.; Jones, M.H.; Sly, P.D.; Stein, R.T. Neutrophilic airway inflammation is a main feature of induced sputum in nonatopic asthmatic children. Allergy 2009, 64, 1597–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eller, M.C.N.; Vergani, K.P.; Saraiva-Romanholo, B.M.; Antonangelo, L.; Leone, C.; Rodrigues, J.C. Can inflammatory markers in induced sputum be used to detect phenotypes and endotypes of pediatric severe therapy-resistant asthma? Pediatr Pulmonol 2018, 53, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansal, P.; Nandan, D.; Agarwal, S.; Patharia, N.; Arya, N. Correlation of induced sputum eosinophil levels with clinical parameters in mild and moderate persistent asthma in children aged 7-18 years. J Asthma 2018, 55, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, R.H.; Brightling, C.E.; McKenna, S.; Hargadon, B.; Parker, D.; Bradding, P.; Wardlaw, A.J.; Pavord, I.D. Asthma exacerbations and sputum eosinophil counts: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002, 360, 1715–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciolkowski, J.; Stasiowska, B.; Mazurek, H. [Control of asthma symptoms and cellular markers of inflammation in induced sputum in children and adolescents with chronic asthma]. Pol Merkur Lekarski 2009, 26, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fleming, L.; Wilson, N.; Regamey, N.; Bush, A. Use of sputum eosinophil counts to guide management in children with severe asthma. Thorax 2012, 67, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petsky, H.L.; Li, A.; Chang, A.B. Tailored interventions based on sputum eosinophils versus clinical symptoms for asthma in children and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017, 8, CD005603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossny, E.; El-Awady, H.; Bakr, S.; Labib, A. Vascular endothelial growth factor overexpression in induced sputum of children with bronchial asthma. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2009, 20, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fireman, E.; Bliznuk, D.; Schwarz, Y.; Soferman, R.; Kivity, S. Biological monitoring of particulate matter accumulated in the lungs of urban asthmatic children in the Tel-Aviv area. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2015, 88, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagakumar, P.; Denney, L.; Fleming, L.; Bush, A.; Lloyd, C.M.; Saglani, S. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells in induced sputum from children with severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016, 137, 624–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzaoui, A.; Ammar, J.; Hamzaoui, K. Regulatory T cells in induced sputum of asthmatic children: association with inflammatory cytokines. Multidiscip Respir Med 2010, 5, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felicio-Junior, E.L.; Barnabe, V.; de Almeida, F.M.; Avona, M.D.; de Genaro, I.S.; Kurdejak, A.; Eller, M.C.N.; Verganid, K.P.; Rodrigues, J.C.; Tiberio, I.; et al. Randomized trial of physiotherapy and hypertonic saline techniques for sputum induction in asthmatic children and adolescents. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2020, 75, e1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buendia, J.A.; Talamoni, H.L. Cost-utility of use of sputum eosinophil counts to guide management in children with asthma. J Asthma 2022, 59, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, S.M.; Miller, S.; Sorscher, E.J. Cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2005, 352, 1992–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmiel, J.F.; Davis, P.B. State of the art: why do the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis become infected and why can't they clear the infection? Respir Res 2003, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoltz, D.A.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Welsh, M.J. Origins of cystic fibrosis lung disease. N Engl J Med 2015, 372, 1574–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenfeld, M.; Emerson, J.; Accurso, F.; Armstrong, D.; Castile, R.; Grimwood, K.; Hiatt, P.; McCoy, K.; McNamara, S.; Ramsey, B.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of oropharyngeal cultures in infants and young children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 1999, 28, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forton, J.T. Detecting respiratory infection in children with cystic fibrosis: Cough swab, sputum induction or bronchoalveolar lavage. Paediatr Respir Rev 2019, 31, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, A.; Caudri, D. Cough swabs less useful but induced sputum very useful in symptomatic older children with cystic fibrosis. Lancet Respir Med 2018, 6, 410–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussaffi, H.; Fireman, E.M.; Mei-Zahav, M.; Prais, D.; Blau, H. Induced sputum in the very young: a new key to infection and inflammation. Chest 2008, 133, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.A.; Ball, R.; Morrison, L.J.; Brownlee, K.G.; Conway, S.P. Clinical value of obtaining sputum and cough swab samples following inhaled hypertonic saline in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2004, 38, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saleh, S.; Dell, S.D.; Grasemann, H.; Yau, Y.C.; Waters, V.; Martin, S.; Ratjen, F. Sputum induction in routine clinical care of children with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr 2010, 157, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, H.; Linnane, B.; Carzino, R.; Tannenbaum, E.L.; Skoric, B.; Robinson, P.J.; Robertson, C.; Ranganathan, S.C. Induced sputum compared to bronchoalveolar lavage in young, non-expectorating cystic fibrosis children. J Cyst Fibros 2014, 13, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Sylva, P.; Caudri, D.; Shaw, N.; Turkovic, L.; Douglas, T.; Bew, J.; Keil, A.D.; Stick, S.; Schultz, A. Induced sputum to detect lung pathogens in young children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2017, 52, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiser, R.; Oakley, J.; Ronchetti, K.; Tame, J.D.; Hoehn, S.; Jurkowski, T.P.; Mahenthiralingam, E.; Forton, J.T. The lung microbiota in children with cystic fibrosis captured by induced sputum sampling. J Cyst Fibros 2022, 21, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, J.E.; Towler, E.; Wagner, B.D.; Accurso, F.J.; Sagel, S.D.; Zemanick, E.T. Sputum induction improves detection of pathogens in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2015, 50, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.I.; Kulkarni, H.; Shajpal, S.; Patel, D.; Patel, P.; Claydon, A.; Modha, D.E.; Gaillard, E.A. Early detection of non-tuberculous mycobacteria in children with cystic fibrosis using induced sputum at annual review. Pediatr Pulmonol 2019, 54, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagel, S.D.; Wagner, B.D.; Anthony, M.M.; Emmett, P.; Zemanick, E.T. Sputum biomarkers of inflammation and lung function decline in children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012, 186, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepissier, A.; Addy, C.; Hayes, K.; Noel, S.; Bui, S.; Burgel, P.R.; Dupont, L.; Eickmeier, O.; Fayon, M.; Leal, T.; et al. Inflammation biomarkers in sputum for clinical trials in cystic fibrosis: current understanding and gaps in knowledge. J Cyst Fibros 2022, 21, 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, V.D.; Moncada-Giraldo, D.; Margaroli, C.; Brown, M.R.; Silva, G.L.; Chandler, J.D.; Peng, L.; Tirouvanziam, R.; Guglani, L.; Program, I.-C. Pilot study of inflammatory biomarkers in matched induced sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage of 2-year-olds with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2022, 57, 2189–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schupp, J.C.; Khanal, S.; Gomez, J.L.; Sauler, M.; Adams, T.S.; Chupp, G.L.; Yan, X.; Poli, S.; Zhao, Y.; Montgomery, R.R.; et al. Single-Cell Transcriptional Archetypes of Airway Inflammation in Cystic Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020, 202, 1419–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kockar Kizilirmak T., G. A. , Yin H., Bruscia E., Egan M., Britto-Leon C. Understanding Impact of CFTR Dysfunction on Airway Immune Cell Composition in Early Lung Disease Pathogenesis. In Proceedings of Am J Respir Crit Care Med; p. 6357.

- Ruddy, J.; Emerson, J.; Moss, R.; Genatossio, A.; McNamara, S.; Burns, J.L.; Anderson, G.; Rosenfeld, M. Sputum tobramycin concentrations in cystic fibrosis patients with repeated administration of inhaled tobramycin. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 2013, 26, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordonez, C.L.; Henig, N.R.; Mayer-Hamblett, N.; Accurso, F.J.; Burns, J.L.; Chmiel, J.F.; Daines, C.L.; Gibson, R.L.; McNamara, S.; Retsch-Bogart, G.Z.; et al. Inflammatory and microbiologic markers in induced sputum after intravenous antibiotics in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003, 168, 1471–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Burden of Disease, C.; Adolescent Health, C.; Kassebaum, N.; Kyu, H.H.; Zoeckler, L.; Olsen, H.E.; Thomas, K.; Pinho, C.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Dandona, L.; et al. Child and Adolescent Health From 1990 to 2015: Findings From the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors 2015 Study. JAMA Pediatr 2017, 171, 573–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, D.R.; Morpeth, S.C.; Hammitt, L.L.; Driscoll, A.J.; Watson, N.L.; Baggett, H.C.; Brooks, W.A.; Deloria Knoll, M.; Feikin, D.R.; Kotloff, K.L.; et al. The Diagnostic Utility of Induced Sputum Microscopy and Culture in Childhood Pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 2017, 64, S280–S288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.; Cockroft, J.L.; Kaufman, R.A.; McCullers, J.A.; Arnold, S.R. Utility of Induced Sputum in Assessing Bacterial Etiology for Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Hospitalized Children. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2022, 11, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramper-Stranders, G.A. Childhood community-acquired pneumonia: A review of etiology- and antimicrobial treatment studies. Paediatr Respir Rev 2018, 26, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahti, E.; Peltola, V.; Waris, M.; Virkki, R.; Rantakokko-Jalava, K.; Jalava, J.; Eerola, E.; Ruuskanen, O. Induced sputum in the diagnosis of childhood community-acquired pneumonia. Thorax 2009, 64, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurade, A.; Dhanawade, S.; Shetti, S. Induced Sputum as a Diagnostic Tool in Pneumonia in Under Five Children-A Hospital-based Study. J Trop Pediatr 2018, 64, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, M.; Hoshina, T.; Abushawish, A.; Kusuhara, K. Evaluation of the usefulness of culture of induced sputum and the optimal timing for the collection of a good-quality sputum sample to identify causative pathogen of community-acquired pneumonia in young children: A prospective observational study. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2023, 56, 1036–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thea, D.M.; Seidenberg, P.; Park, D.E.; Mwananyanda, L.; Fu, W.; Shi, Q.; Baggett, H.C.; Brooks, W.A.; Feikin, D.R.; Howie, S.R.C.; et al. Limited Utility of Polymerase Chain Reaction in Induced Sputum Specimens for Determining the Causes of Childhood Pneumonia in Resource-Poor Settings: Findings From the Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health (PERCH) Study. Clin Infect Dis 2017, 64, S289–S300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honkinen, M.; Lahti, E.; Osterback, R.; Ruuskanen, O.; Waris, M. Viruses and bacteria in sputum samples of children with community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012, 18, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, C.K.; Mirdha, B.R.; Singh, S.; Seth, R.; Bagga, A.; Lodha, R.; Kabra, S.K. Use of Induced sputum to determine the prevalence of Pneumocystis jirovecii in immunocompromised children with pneumonia. J Trop Pediatr 2014, 60, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRocque, R.C.; Katz, J.T.; Perruzzi, P.; Baden, L.R. The utility of sputum induction for diagnosis of Pneumocystis pneumonia in immunocompromised patients without human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis 2003, 37, 1380–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zar, H.J.; Tannenbaum, E.; Hanslo, D.; Hussey, G. Sputum induction as a diagnostic tool for community-acquired pneumonia in infants and young children from a high HIV prevalence area. Pediatr Pulmonol 2003, 36, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 2023, W.G.t.r. WHO Global Tuberculosis Report 2023. WHO report. Availabe online: https://www.who. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zar, H.J.; Tannenbaum, E.; Apolles, P.; Roux, P.; Hanslo, D.; Hussey, G. Sputum induction for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in infants and young children in an urban setting in South Africa. Arch Dis Child 2000, 82, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Zahrani, K.; Al Jahdali, H.; Poirier, L.; Rene, P.; Menzies, D. Yield of smear, culture and amplification tests from repeated sputum induction for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2001, 5, 855–860. [Google Scholar]

- Hatherill, M.; Hawkridge, T.; Zar, H.J.; Whitelaw, A.; Tameris, M.; Workman, L.; Geiter, L.; Hanekom, W.A.; Hussey, G. Induced sputum or gastric lavage for community-based diagnosis of childhood pulmonary tuberculosis? Arch Dis Child 2009, 94, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.P.; Higdon, M.M.; Hammitt, L.L.; Prosperi, C.; DeLuca, A.N.; Da Silva, P.; Baillie, V.L.; Adrian, P.V.; Mudau, A.; Deloria Knoll, M.; et al. The Incremental Value of Repeated Induced Sputum and Gastric Aspirate Samples for the Diagnosis of Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Young Children With Acute Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 2017, 64, S309–S316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioos, V.; Cordel, H.; Bonnet, M. Alternative sputum collection methods for diagnosis of childhood intrathoracic tuberculosis: a systematic literature review. Arch Dis Child 2019, 104, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Angulo, Y.; Wiysonge, C.S.; Geldenhuys, H.; Hanekom, W.; Mahomed, H.; Hussey, G.; Hatherill, M. Sputum induction for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2012, 31, 1619–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinsohn, D.M.; Leonard, M.K.; LoBue, P.A.; Cohn, D.L.; Daley, C.L.; Desmond, E.; Keane, J.; Lewinsohn, D.A.; Loeffler, A.M.; Mazurek, G.H.; et al. Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis of Tuberculosis in Adults and Children. Clin Infect Dis 2017, 64, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.P.; Ren, S.F.; Wang, X.F.; Wang, M.S. Comparison of bronchial brushing and sputum in detection of pediatric pulmonary tuberculosis. Ital J Pediatr 2016, 42, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Lin, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, W.; Shi, Y. Comparison of sputum induction and bronchoscopy in diagnosis of sputum smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis: a systemic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med 2020, 20, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olbrich, L.; Verghese, V.P.; Franckling-Smith, Z.; Sabi, I.; Ntinginya, N.E.; Mfinanga, A.; Banze, D.; Viegas, S.; Khosa, C.; Semphere, R.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a three-gene Mycobacterium tuberculosis host response cartridge using fingerstick blood for childhood tuberculosis: a multicentre prospective study in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Infect Dis 2024, 24, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.M.; Hung, E.; Tsang, T.; Yin, J.; So, H.K.; Wong, E.; Fok, T.F.; Ng, P.C. Induced sputum inflammatory measures correlate with disease severity in children with obstructive sleep apnoea. Thorax 2007, 62, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ervine, E.; McMaster, C.; McCallion, W.; Shields, M.D. Pepsin measured in induced sputum-a test for pulmonary aspiration in children? J Pediatr Surg 2009, 44, 1938–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosewich, M.; Zissler, U.M.; Kheiri, T.; Voss, S.; Eickmeier, O.; Schulze, J.; Herrmann, E.; Ducker, R.P.; Schubert, R.; Zielen, S. Airway inflammation in children and adolescents with bronchiolitis obliterans. Cytokine 2015, 73, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Lessmann, A.; Plaza, V.; Consensus, G. Multidisciplinary consensus on sputum induction biosafety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Allergy 2021, 76, 2407–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

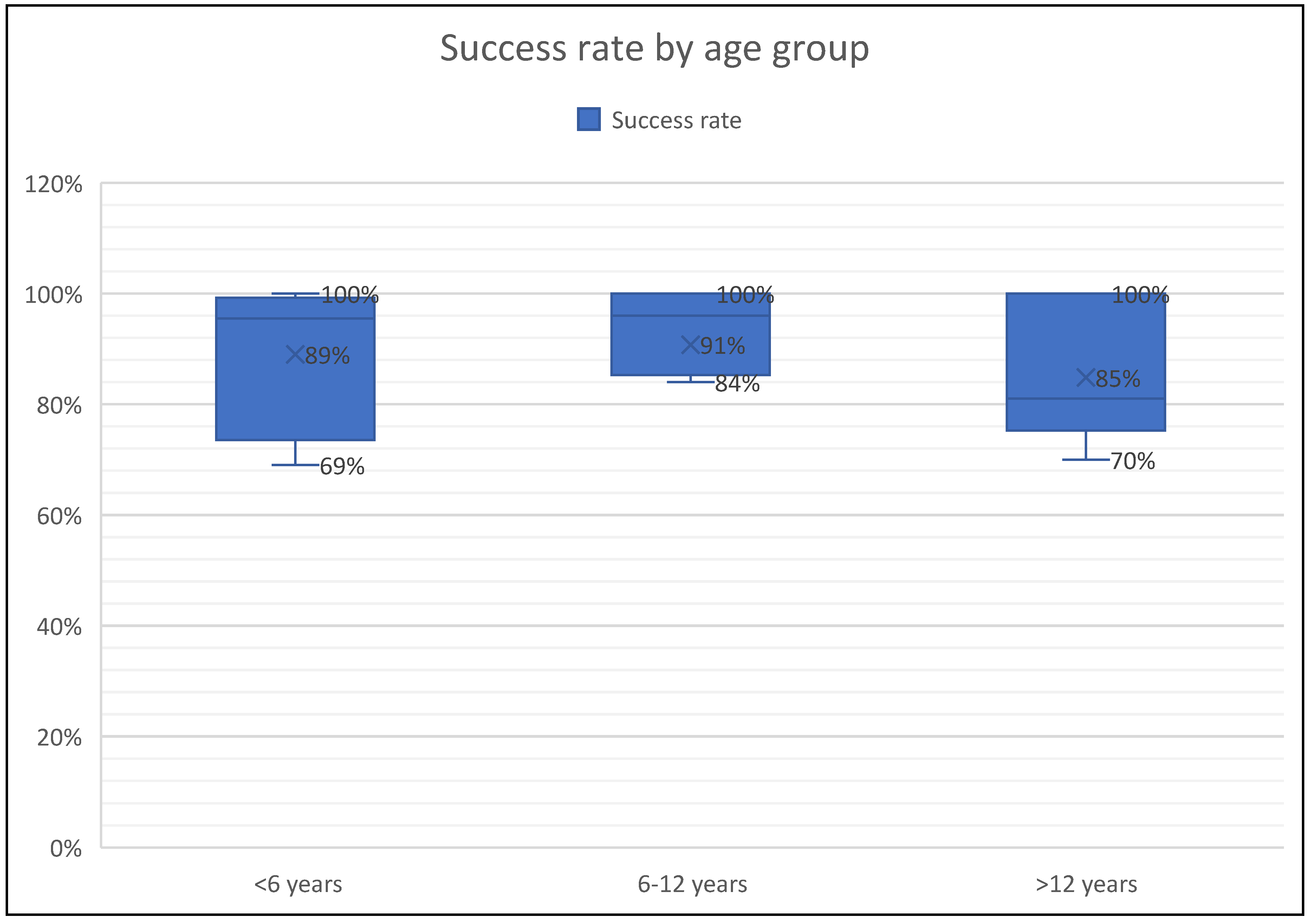

| First Author | N of subjects | Age (y) | Diseases | Analysis | Success rate | Side effects |

| De Boeck et al. (2000) [24] |

19 | 8.6 (4.3-15.2) | Cystic fibrosis | Microbiological yield | N/A | Salty taste Fall in FEV1>6 Fall in FEV1> Wheezing and cough(5.2%) |

| Wilson et al. (2000) [11] | Asthma:60 HC:27 |

10.2 (8.4-11) | Asthma | eosinophil counts and ECP levels | 61% | Dry cough |

| Jones PD et al. (2001) [25] | 53 | 7-16 (10.8) | Asthma | Safety and success of SI | 92% | Dry cough (3.7%) Fall in FEV1 >20% (3.7 %) |

| Sagel et al. (2001) [12] | CF:20 HC:11 |

6-12 | Cystic fibrosis | Total cell counts, ANC, IL-8, NE activity | 92% in CF 64% in HC |

Fall in FEV1 >10% (43%) Fall in FEV1 >20% (14%) |

| Covar R.A. et al. (2004) [27] | 117 | 13 (11-15) | Asthma | eosinophil counts, SPEos, ECP levels | 76.9% | Bronchospasm (7.7%) GI dyscomfort, nausea |

| Lex C et al. (2005) [22] | 38 | 6-16 | Asthma | Eosinophil, neutrophil counts | 73.6% | Dyspnea and wheezing (18.4%), Fall in FEV1>20% (7.8%) |

| Ciolkowski J et al. (2009) [32] | 154 | 8-21 | Asthma | Eosinophil, neutrophil counts | 78% | Not reported |

| Drews C.A et al. (2009) [28] | 77 | 12-13 | Asthma | eosinophil counts | 70.1% | Not reported |

| Ervine E et al. (2009) [86] | 21 | 8.7 (4-16) | GER | Pepsin | 100% | No side effects |

| Hossny E et al. (2009) [35] | Asthma:18 HC:34 |

9.8 (6-16) | Asthma | VEGF levels | 100% | Not reported |

| Lahti E et al. (2009) [66] | 101 | 3.4 (1.7-6.8) | CAP | Microbiological yield | 75.2% | unpleasant due to nasophayngeal aspiration |

| Hamzaoui et al. (2010) [38] | Asthma: 40 HC:20 |

11 (5-16.5) | Asthma | Treg cells, cytokines | 100% | Not reported |

| Moore et al. (2011) [21] | 270 | 3.2 (0.2-13 years | Pulmonary TB | Microbiological yield (Diagnosis of TB) | 99% | Mild epistaxis (15%), mild wheeze (0.6%), increased cough (6%) |

| Fleming et al. (2012) [33] |

45 | 13 (10.2-15.8) | Severe asthma | Eosinophils, neutrophil counts | 85% | Not reported |

| Das C.K et al. (2014) [71] | 105 | 74.5 ± 43.7 months | Intensive care with pneumonia | Microbiological yield (PCR assay) | 100% | Vomiting (8.5%), epistaxis (3.8%), transient bronchospasm(1.9%) |

| Joel et al. (2014) [23] | 1294 | 3.8 (<18 years) | Pulmonary TB | Microbiological yield (Diagnosis of TB) | 100% | Vomiting (0.5%), Mild epistaxis (0.4%), mild wheeze (0.08%), increased cough (0.17%) |

| Blau et al. (2014) [50] | 10 | 3 - 7.4 years | Cystic fibrosis | Microbiological yield | 91% | ‘Distressed’(n:2): crying and resisting somewhat. ‘Very distressed’ (n:1): crying and resisting a lot |

| Fireman E. et al. (2015) [36] | 136 | 12.6 ± 2.9 years | Asthma | Particulate matter level | 100% | Not reported |

| Jochmann et al. (2016) [18] | 64 | 2.7 (0.6 -6.3) | Chronic airway diseases | Microbiological yield | 96% | 4.6% (3/64) did not tolerate procedure, none |

| Nagakumar et al. (2016) [37] | Asthma:13 LRTI: 6 |

12.5 (8-16) years | Severe asthma | Flow cytometry | 100% | Not reported |

| D’Sylva et al. (2017) [51] | 57 | 3.3 (0.9-6.7) years |

Cystic fibrosis | Microbiological yield | 95% | Not reported |

| Murdoch et al. (2017) [63] | 3772 | 0.7 (0.1-5) | CAP | Microbiological yield | 69.1% | Transient drop in oxygen saturation (0.34%) |

| Eller et al. (2018) [29] | 40 | 12.8 (6-18) | Severe asthma | Total cell counts, IL-10, GM-CSF, IFN-gamma, and TNF-alpha | 70% | Not reported |

| Ronchetti et al., (2018) [19] | 124 | 8.2 (4.9-12.6) | Cystic fibrosis | Microbiological yield | 84% | upset(9%), mild wheeze(3%), vomiting(2%) transient dizziness(<1%) |

| Ahmed M.I et al. (2019) [54] | 42 | 11.4 (5-17) | Cystic fibrosis | Microbiological yield- NTM detection | 89% | Not reported |

| Felicio-Junior et al. (2020) [39] | 33 | 7-18 | Asthma | Differential cell count | 91% | No side effects |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).