1. Introduction

In immunocompromised patients, the risk of opportunistic infections is high. Viral, bacterial, or fungal agents contribute to increased morbidity and mortality [

1].

These patients have an incompetent immune system either as a primary defect of the innate immune system or adaptive immunity, immune dysregulation [

2], or secondary to immunosuppressive therapy and other prior therapies (chemotherapy, longtime administration of steroids or antimicrobials), but also in the case of organ transplant, altered integrity of the mucocutaneous barrier, metabolic and endocrine disorders.

Nocardiosis is an infectious disease caused by Nocardia, which is a gram-positive bacillus with branching hyphae found throughout the environment in soil, decomposing vegetation, and other organic matter [

3], that can cause localized or disseminated disease. It usually manifests as localized cutaneous and pulmonary disease with abscess formation. The disseminated nocardiosis can affect any organ with lesions in the brain or meninges being most common [

4].

There are currently 54 known Nocardia species, N. nova complex, N. abscessus complex, N. transvalensis complex, and N. farcinica being the most common species involved in human pathology [

5]. There are approximately 500-1000 cases per year in the United States, and Italy reported around 100 cases during a five-year period in Europe.

In the last two decades, the incidence rate of Nocardiosis has increased from 0.33 to 0.87 per 100,000 patients. This rise can be attributed to various factors such as aging, increased use of immunosuppressive drugs, chemotherapy, biological agents, and monoclonal antibodies. All of these factors impact the ability of the host to adapt and react to bacterial infections.

2. Case Report

A male patient, employed in the forestry industry, aged 58 and a nonsmoker, was diagnosed with chronic membranous glomerulonephritis and nephrotic syndrome in 2016. He was given 150mg of azathioprine (Imuran®) once a day (2mg/kg) for immunosuppressive therapy.

However, there was no improvement in proteinuria reduction, so after 4 weeks, methylprednisolone, an oral corticoid, was added to his treatment (64mg once a day). The steroid treatment helped to reduce proteinuria to about 500mg/l and it remained stable. The azathioprine treatment was stopped after 8 weeks because the patient developed an extensive area of herpes zoster covering 3 intercostal dermatomes.

The patient continued to receive chronic steroid treatment and had regular check-up visits in the nephrology department between 2016 and 2022. He was admitted several times for edema during this period and also developed hypertension and steroid-induced diabetes mellitus. To manage these conditions, he was prescribed ACE inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, high-potency statin, and insulin in a basal-bolus regimen. The proteinuria was dose-dependent and at lower doses than the 16 mg methylprednisolone threshold, the proteinuria was not controlled.

During this period the serum creatinine remained at a stable level of 1 mg/dL

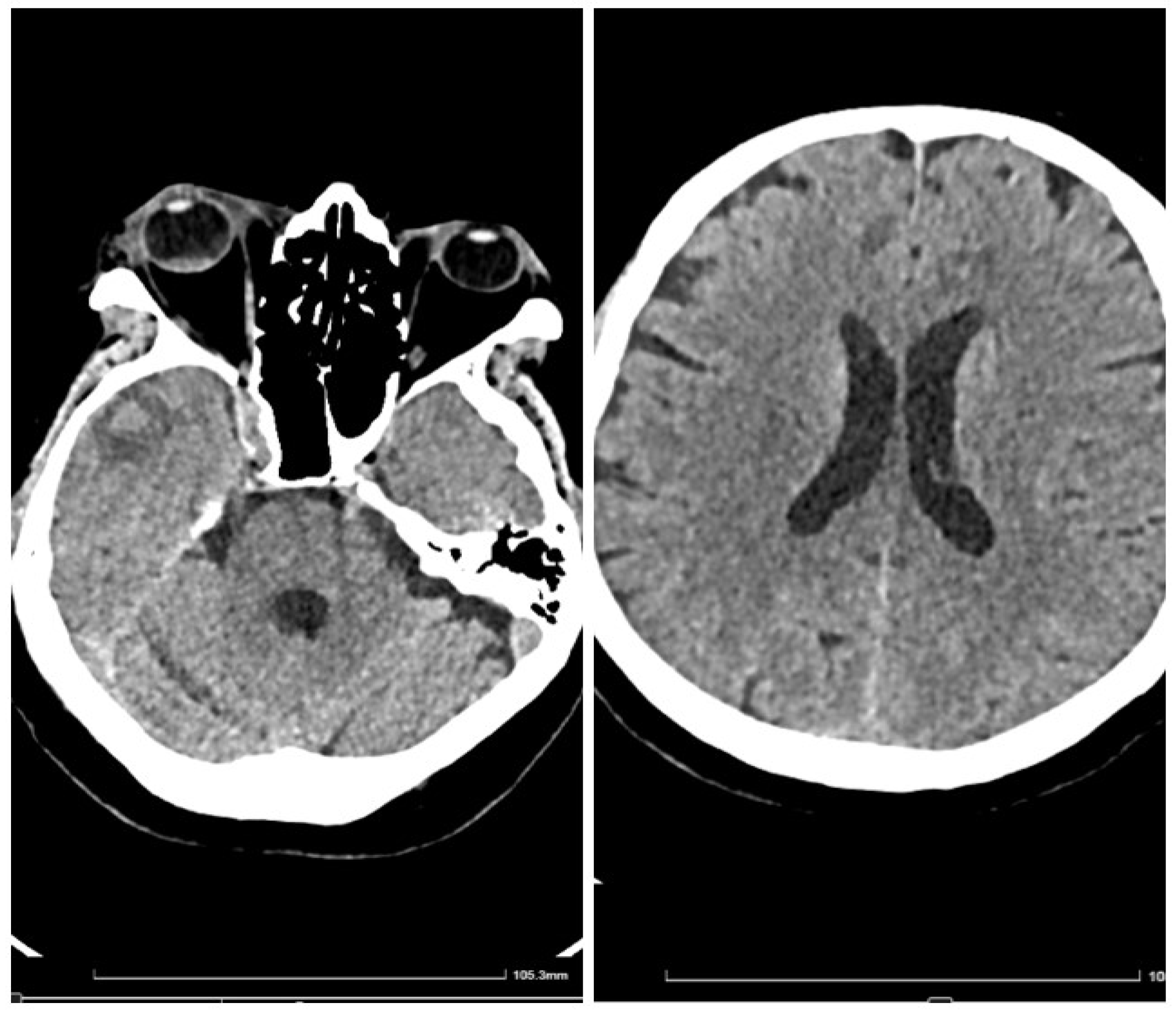

In early May 2023, the patient developed a respiratory illness that was treated with iv. gentamycin and ceftriaxone for 7 days in a territorial hospital and discharged. In late May 2023 he developed right retrorbital pain, painful right red eye with acute vision loss, headaches, 7 kg weight loss, and aggravated fatigue that were not controlled with usual medication and cough. The patient was admitted to the Internal Medicine Department for further evaluation. We performed a native cranial CT (

Figure 1) and an MRI without contrast which showed multiple lesions -10- that were classified as undetermined lesions on CT scan and possible abscessed metastases on the MRI.

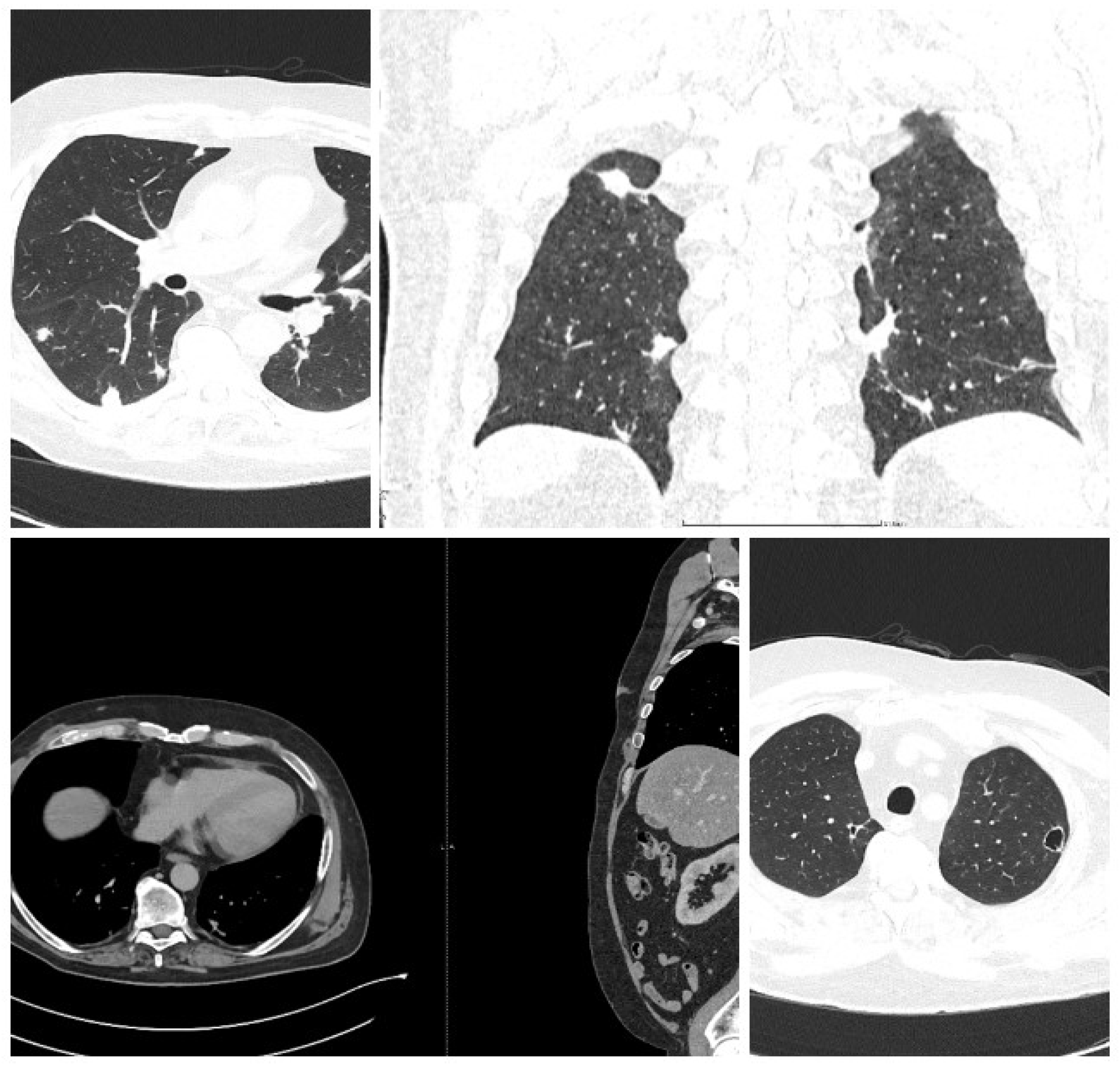

It was suspected that there was a metastatic tumor and a full-body CT scan was performed (

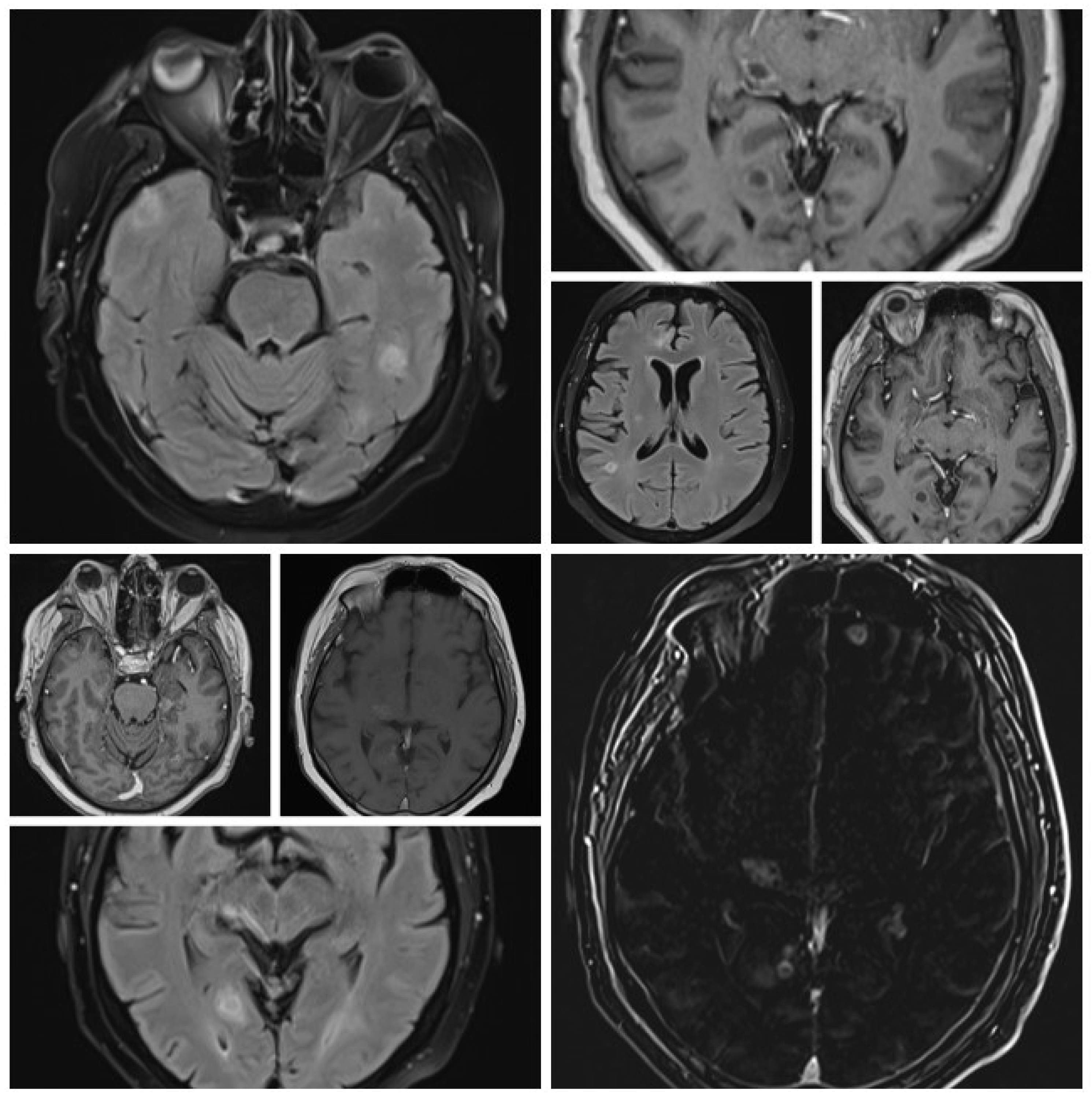

Figure 2). The CT scan discovered multiple abscesses in the lungs and under the skin. A second contrast MRI (

Figure 3) scan was conducted which revealed abscesses in all parts of the brain, including the right thalamus and left cerebellar hemisphere, with ring-like contrast-enhancing lesions. However, the lesions were relatively stable compared to the previous MRI.

The full-body CT scan showed multiple nodular cavitating lesions spread throughout the pulmonary area and several subcutaneous abscesses in various locations, with one notable abscess in the distal portion of the anterior serratus muscle and right pre-pectoral subcutaneous fat. Additionally, there were multiple nodules on the peritoneum and perisplenic fat, all measuring between 2-3 cm in diameter.

The initial bloodwork showed mild leucocytosis (15000/mm3), with normal procalcitonin and a CRP of 11.6 mg/L, an ESR of 49 mm/h, a 2.3g proteinuria, a creatinine of 1.2 mg/dL and otherwise unremarkable biochemistry. Blood cultures were sterile and a subcutaneous abscess was drained and sent to the laboratory for analysis (

Figure 4). The patient was started on empirical antibiotics with iv meropenem 500 mg t.i.d. and amoxicillin/clavulanate 1g b.i.d. The initial clinical course was favorable, with remission of head pain.

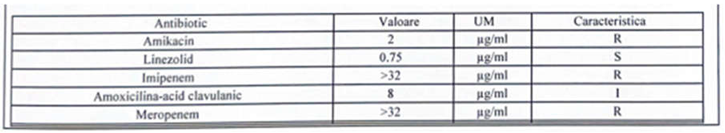

The antibiogram showed that the species was in fact rod-shaped with filamentous ramification gram-negative bacteria, which was identified as Nocardia farcinica which had a susceptibility to linezolid and was resistant to imipenem, amikacin, and intermediate to amoxicillin-clavulanate (

Figure 6). The patient was started on a combination of linezolid 600mg bid, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 400 mg/ 80 mg t.i.d. Also a meropenem resistance study was performed which showed resistance to meropenem, and thus it was stopped in day 6 and continued on the other two antimicrobials, but relapsed on the pain scale

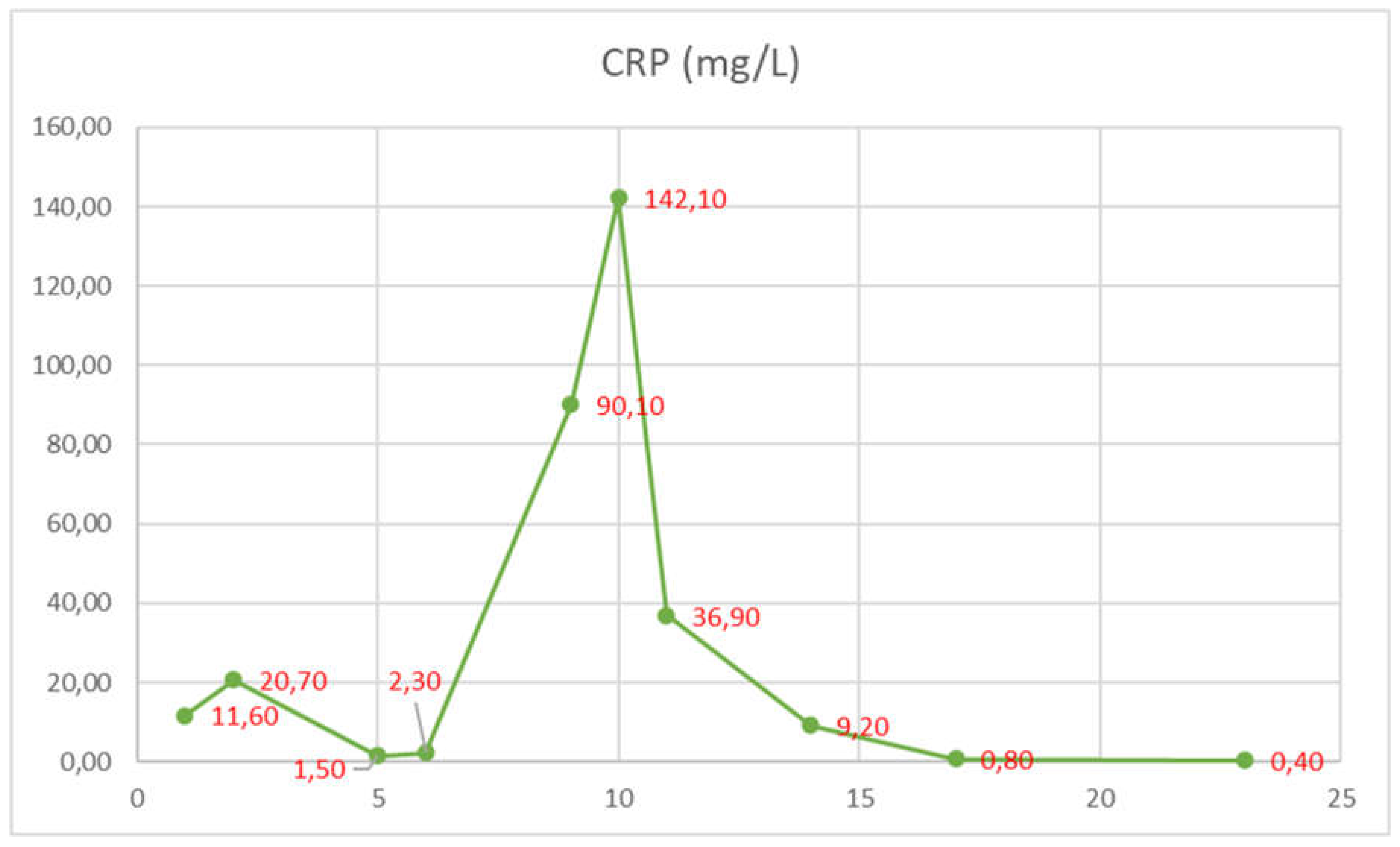

The subsequent clinical course after meropenem was stopped was relatively severe, with the patient developing intense right eye pain and a sudden drop in visual acuity, that required a step-up of pain medication, eventually, the patient received a combination of metamizole, tramadol, acetaminophen, pethidine, and nefopam. Even so, the patient declared a 10/10 Borg RPE pain score. The second MRI showed right posterior eye pole thickening and retroorbital edema, highly suspicious of retinal detachment, which the ophtalmology consult confirmed as no light perception, so the decision was made to readminister meropenem, again with a decrease in the pain scale. Also there was a spike in CRP level corroborated with withdrawal of meropenem and improvement with its re-administration. After re-administration of meropenem, the clinical course dramatically improved, and the patient received only on-demand acetaminophen.

The patient received also a regimen aimed at reducing brain edema with dexamethasone, mannitol, and complex B vitamin, altogether reducing the proteinuria to 0.3 g/L.

The total duration of the three antibiotics combined was 35 days, and the patient was discharged with a diagnosis of disseminated Nocardia farcinica infection, recommending a continuation of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for at least one year.

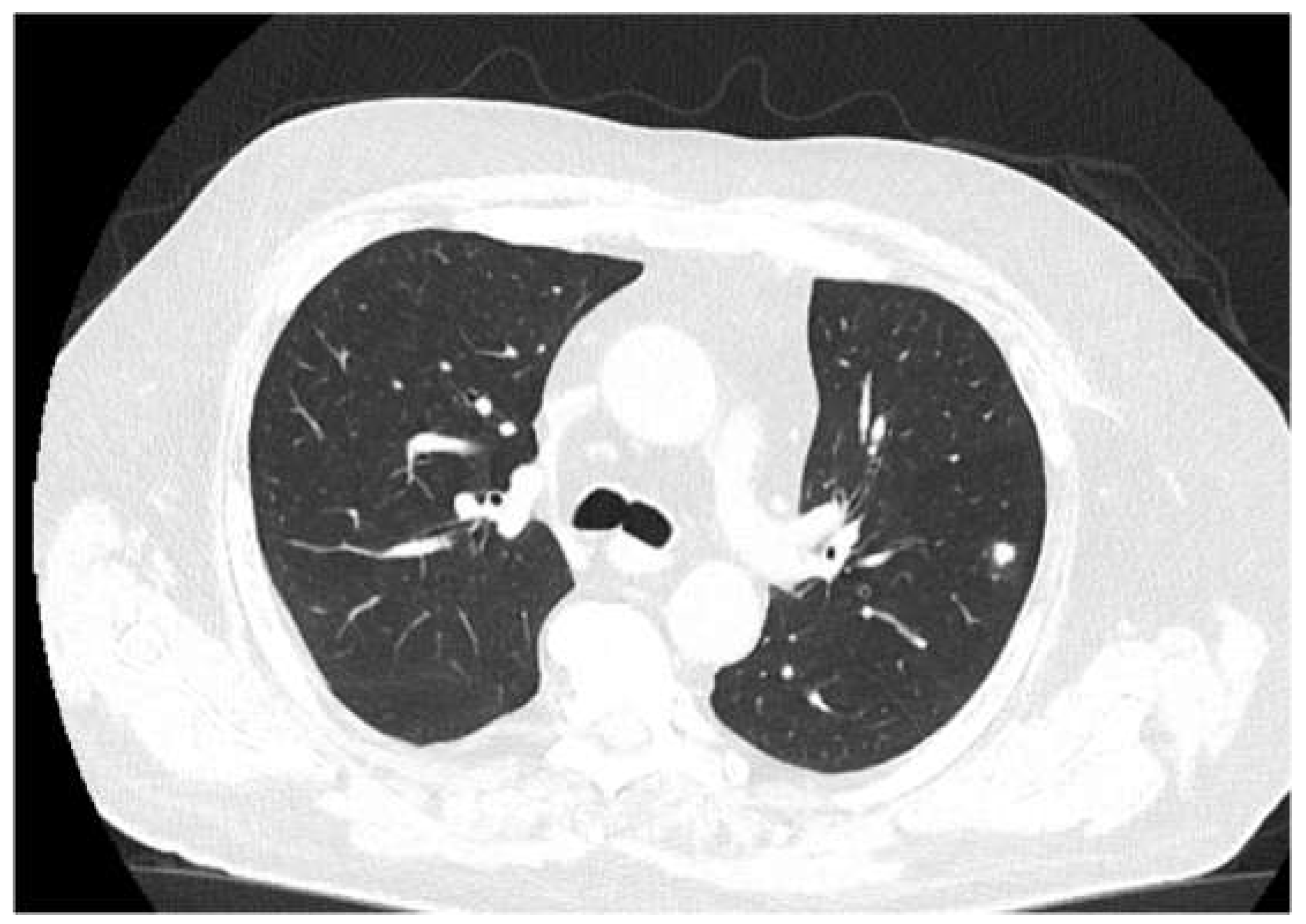

The patient received a follow-up brain MRI and chest CT (

Figure 5) at 3 months, which showed complete remission of the brain abscess.

Figure 1.

Initial cranial CT (no contrast).

Figure 1.

Initial cranial CT (no contrast).

Figure 2.

-CT (with contrast, showing disseminated lesions in lungs, abdomen, and soft tissues (the arrows indicate the evacuated abscess).

Figure 2.

-CT (with contrast, showing disseminated lesions in lungs, abdomen, and soft tissues (the arrows indicate the evacuated abscess).

Figure 3.

MRI (different sequences showing brain abscesses).

Figure 3.

MRI (different sequences showing brain abscesses).

Figure 4.

Macroscopic aspect of the evacuated subcutaneous abscess and microscopic aspect with ramified filamentous Gram-positive bacilli growing in an aerobic environment.

Figure 4.

Macroscopic aspect of the evacuated subcutaneous abscess and microscopic aspect with ramified filamentous Gram-positive bacilli growing in an aerobic environment.

Figure 5.

-Follow-up Ct at three months. The chest CT does not show any cavitating lesions, with residual scaring and healing processes of the lesions.

Figure 5.

-Follow-up Ct at three months. The chest CT does not show any cavitating lesions, with residual scaring and healing processes of the lesions.

Figure 6.

CRP level dynamics (the spike indicates meropenem withdrawal and corroborates with the sharp increase in headache intensity and retroorbital pain).

Figure 6.

CRP level dynamics (the spike indicates meropenem withdrawal and corroborates with the sharp increase in headache intensity and retroorbital pain).

Table 1.

Antibiogram for Nocardia farcinica (R-resistant, I-intermediate resistance, S-sensitive, Valoare-denotes minimal inhibitory concentration-MIC).

Table 1.

Antibiogram for Nocardia farcinica (R-resistant, I-intermediate resistance, S-sensitive, Valoare-denotes minimal inhibitory concentration-MIC).

4. Discussion

Although nocardiosis is a predominantly tropical disease, Nocardia spp. are found all over the world, with some species found more commonly in specific areas [

8]. There are over 100 species described, for example, Nocardia brasiliensis is found more often in tropical regions, while Nocardia nova is found predominantly in northern states and midwest of the USA, while in south-eastern states Nocardia farcinica was more common [

9]. In Europe, in France Nocardia farcinica and Nocardia abscessus were found in one-fifth of the cases each.[

10]

Nocardia can be responsible for severe opportunistic infections in immunocompromised patients and patients with chronic bronchopulmonary diseases.

Recipients of solid organ transplants and HIV-infected individuals are usually the most common type of patients because of their ineffective immune system.[

9]

Pulmonary nocardiosis is the most common form of the disease, often mimicking tuberculosis or other fungal infections. Some estimates suggest that more than two-thirds of the patients have only pulmonary involvement [

11]. Cutaneous involvement along lymphadenopathy is also frequently described.[

12]. The disseminated form involves at least three different organs, with virtually any organ involved. CNS involvement usually means a disseminated form, patients describing paresthesia, numbness, motor function loss or focal neurological signs.

This case we present has some peculiarities. At first, although the patient has some exposure because of working in forestry, he did not mention any cutaneous lesion in the preceding months, which could provide an entry point and we suspect that the patient had its initial form as a pulmonary one through inhalation. Secondly, the patient did not have any major neurologic symptoms as expected, although the retroorbital pain grew stronger, which required high doses of several strong antalgic drugs. Thirdly, the meropenem treatment improved the clinical outcome even if the antibiogram showed resistance, which could mean that it probably had a synergistic effect along the linezolid-trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole combination.

The patient is an immunocompromised one, because of the long-term use of for his cortico-sensitive glomerulonephritis. Indeed, after high doses of dexamethasone were administered for the brain abscess the proteinuria dropped to 0.4 g/24h, confirming the corticosensitivity of the glomerulonephritis.

The presentation in this case with cavitating lesions is highly suspicious of disseminated forms in immunocompromised patients [

13], and is associated with doses of corticosteroids. Steinbrink et al. [

13] found 135 patients in whom cavitation occurred only in the immunocompromised one, with almost 20% mortality. The lung was the most common site of infection, and only 27% had a disseminated form, with Nocardia asteroides being the most common in the immunocompromised patients (67%), and Nocardia farcinica in only 16% of the cases of the same group.

Whether dissemination ensued, following respiratory tract infection is dependent on the containment of the initial infection by the host. With obvious immunosuppression, such as with high-dose corticosteroids dissemination is more common. In our patient, cutaneous and subcutaneous infection could have been the first point of entry as the patient could have been easily bruised at work, but it is described more common in Nocardia brasiliensis infections [

14].

The most interesting aspect is the response to meropenem, even though the antibiogram showed resistance to this drug, highlighting a possible potentiating effect of one on another. We also presumed that it might have been another bacteria that we did not identify, and that could have been the cause of the orbital pain ans subsequent spike in CRP levels, but we cannot ascertain for sure.