1. Introduction

The global population is experiencing a significant demographic shift with an increased number of older adults. This trend, known as demographic aging, is driven by declining birth rates and increased life expectancy. According to the World Health Organization [

1], in 2030, 1 in 6 people worldwide will be 60 years old or older. At that time, the proportion of the population aged 60 and over will increase from 1 billion in 2020 to 1.4 billion. By 2050, the global population of 60 and over is expected to double to 2.1 billion. The number of people aged 80 and over is projected to triple between 2020 and 2050, reaching 426 million. Portugal is one of the countries with the highest Aging Index in the world, and recent statistics place Portugal as the 4th fastest-aging country [

2]. These projections are also related to the increase in life expectancy in Portugal, which rose by more than five years, from 76.4 years to 81 years, between 2000 and 2021 [

3]. With increased longevity, older adults have had a higher dependency rate, rising from 24.4% in 2001 to 37.6% in 2022 [

4]. Storeng et al. [

5] concluded in a cross-sectional analysis that individuals aged 60 to 69 who suffer from three or more diseases fit within a profile of complex morbidity. Over the years, these individuals are those who develop severe disability in performing basic activities of daily living and have a moderate risk of mortality.

In the perioperative and acute care settings, understanding the illness and planning the surgery represent situational transitions of health and illness for both the person and their family, which involve uncertainties, fragility, and vulnerability [

6]. Therefore, the relationship between the nurse, the hospitalized person, and the family needs to be supported by a partnership intervention model. This model should ensure genuine sharing of power and the right to make choices [

7]. Exacerbation of chronic illness or sudden event affects the person’s health condition by potentially leading to functional deficits (loss or alteration of an anatomical, physiological, or psychological structure or function), activity restrictions (limitation or loss of the ability to perform usual activities due to functional deficits), and limitations in participation in decision-making about their health project [

8,

9,

10]. Therefore, the implementation of safe, individualized, and quality care is a universal concern [

11].

Given the growing concern about the rising burden of chronic diseases and the prevalence of multimorbidity, it is necessary to innovate healthcare to effectively respond to increasingly complex therapeutic regimens [

12]. Individualized nursing care is essential for addressing the complex and diverse needs of patients in various healthcare settings. It goes beyond the one-size-fits-all model, recognizing that each patient's health status, personal history, and preferences play a crucial role in shaping their care needs [

13,

14,

15,

16]. For individualized nursing care, establishing an interpersonal, ethical, and understanding relationship is essential, serving as a key to successfully identifying and implementing the most appropriate nursing intervention [

17]. This relationship enables understanding the individual and their context, as well as fostering a collaborative approach with the patient or caregiver to promote self-care in its dual sense: self-care of oneself and others [

7]. So, the definition of individualized care includes the various actions that occur during interactions between nurses and patients. Initially, nurses obtained wide information regarding the patient's preferences, needs, fears, and viewpoints. Next, they mobilize this data about the patient's traits and circumstances, as well as their responses to health issues, to plan and execute the necessary activities and interventions. Lastly, nurses encourage patient involvement in the planning and implementation of nursing interventions [

18,

19]. From the patients' perspective, individualized care should be defined based on their evaluation, perception, or understanding of the interventions provided by nurses [

14]. From the nurses' perspective, individualized care is achieved when interventions are adjusted to meet and respond to the specific needs of each patient [

18].

Recent studies have demonstrated the positive effect of individualized care on patient outcomes. For instance, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease receiving individualized nursing care had better results in longer walking distances, in all domains of both the physical and mental composites and improved quality of life, compared with patients receiving traditional nursing care [

20]. According to Suhonen et al. [

15] individualized interventions impact the effectiveness of educational interventions, rehabilitation success, satisfaction with nursing care, quality of life improvements, individual autonomy, cost-effectiveness of nursing interventions, quality of communication, adherence to therapeutic regimens, and increased motivation and job satisfaction among nursing teams. Individualized nursing was identified as a feasible intervention, that has resulted in rehabilitation after percutaneous coronary procedures, with an improvement of the levels of anxiety, sleep quality, and quality of life, as well as the reduction of postoperative complications [

21].

Previous studies have assessed nurses' perceptions of individualized care in medical and surgical wards [

9,

14,

18,

19,

21,

20], intensive care units [

10], and primary care settings [

18]. This study integrates new contexts, such as emergency and perioperative care, specifically in the operating room. Despite its benefits, the implementation of individualized nursing care faces several challenges. These include limitations in the resources, variability in care practices, organizational culture, leadership styles, and ratios [

22,

23]. The nonattendance of individualized care results in insufficient identification of patient dimensions, which have an important role in the unmet needs, that can compromise negatively the health trajectories of persons, families, and caregivers [

24,

25,

26]. Therefore, this research was conducted to evaluate the individualized care perceptions of nurses in acute medical and perioperative settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Aim, Design, and Setting

The study aimed to characterize the sociodemographic profile of nurses in acute medical and perioperative care settings; and identify the items of nursing care individualization, through ICS-A-NURSE and ICS-B-NURSE, that nurses perceive as most integrated into their clinical practice. This is a cross-sectional study including two assessments: ICS-A-NURSE and ICS-B-NURSE, which are primary tools utilized to measure nurses' perceptions regarding the customization of care including the Individualized Care Scale nursing version (ICS-Nurse), which is better suited for acute care environments. The two scales were applied simultaneously from January 10th to February 29th, 2024, in Portugal (Lisbon) at a University Hospital Center, in the Ophthalmology Service (operating room and inpatient ward), in the Cardiology Service, in the Medicine Service, and in the Medical Emergency Unit.

This study is part of Study I of the Research Project titled "Individualization of Care: The Nursing Partnership Intervention in Hospital Settings” (

INbyCARE). It aims to establish the baseline of nurses perceived and provided individualized care, which will contribute to the characterization of usual care and stratify the aspects of individualization that are less incorporated into clinical practice. This will enable the subsequent implementation of a Partnership Intervention Program [

7] designed to enhance the implementation of individualized care in the included environments.

2.2. Participants and Measures

The sample comprised 112 nurses practicing in the acute medical and perioperative settings, from 146 nurses (participation rate = 76.7%). The sample was non-probabilistic, based on convenience [

27]. The inclusion criteria were: i) nurses with at least 6 months of professional experience in the medical and surgical specialty services where they are allocated; ii) those nurses who express their voluntary and informed consent to participate in the study.

The ICS-Nurse is a self-administered scale developed originally in Finland by Suhonen et al. [

18]. Amaral et al. [

19] translated and validated the Portuguese population's ICS Nurse (A and B) scale. An email was sent to the author [

19], who responded by granting permission for the use of the translated scale. The ICS-A-Nurse subscale aims to assess nurses’ perceptions of how they support their patients' individuality through specific nursing activities during their current activity. The ICS-B-Nurse subscale seeks to assess nurses’ perceptions of how they evaluate the maintenance of individuality in their care, such as during their last shift. Within these two dimensions, individualized care includes three subscales: clinical situation (ClinA-Nurse and ClinB-Nurse) (items: 1–7), personal life situation (PersA-Nurse and PersB-Nurse) (items: 8–11), and decisional control over care-related decisions (DecA-Nurse and DecB-Nurse) (items: 12–17). The response options range from 1 to 5 (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree to some extent, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree to some extent, 5 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicate a higher perception of individuality in care (Suhonen et al., 2010; Rodríguez-Martín et al., 2022).

The

Clinical Situation sub-dimension explored care behaviors that assist in maintaining patients' individuality concerning their reactions to the illness, their emotions, and the personal significance of the illness. The

Personal Life Situation sub-dimension examines care behaviors that help preserve patients' individuality concerning their beliefs and values, routines, activities, preferences, family relationships, and experiences both at work and in the hospital. The

Decisional Control over Care sub-dimension investigates care behaviors that support patients' individuality by considering their emotions, thinking, requests, and their ability to have input and participate in decisions regarding their care [

18].

2.3. Research Ethics

This study protocol was submitted and reviewed by the Health Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Center, where the research was conducted, and received approval number: I/25010/2023 (16/11/2023). All participants were provided with comprehensive information about the study’s objectives, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before their inclusion in the study, ensuring they understood their rights, including the right to withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences.

Data were collected via responses to a provided link and securely stored with password protection. Access to the data was restricted exclusively to the principal investigators, ensuring confidentiality and data integrity.

2.4. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 27 software. A descriptive analysis was performed to examine the socio-demographic and employment characteristic variables.

Internal consistency reliability analysis was assessed using Cronbach's Alpha to ensure that the items on the scale reliably measure the dimensions of individualized nursing care. Cronbach's Alpha values above 0.7 are generally considered acceptable, the values more proximally of the 1 indicating better internal consistency [

28]. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used on a validated scale to better understand the relationships between the variables, with the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin index confirming the adequacy of the data for this analysis. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test shows that the variables related to the individualization of nursing care do not follow a normal or uniform distribution in the population. The Kruskal-Wallis was considered a non-parametric alternative to one-way ANOVA [

28]. However, no statistically significant differences were found between the relationship of age groups, education level, and professional experience with the sub-dimensions of the individualization of care. In all statistical tests, only a 5% acceptable error probability was considered, meaning that a result was deemed statistically significant if

p < 0.05 [

27].

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

The sample consisted of 112 nurses, of which 14.3% were from the Ophthalmology Service, 26.8% from the Medical Service, 24.1% from the Cardiology Service, and 34.8% from the Medical Emergency Unit (

Table 1). The average age of the nurses included was 39.4 years ± 12.736 (minimum age = 22 years and maximum age = 65 years), with the most represented age group being 36 to 40 years. Regarding gender, 82.1% were female, and 72.3% of the total nurses held an undergraduate degree, followed by a master’s degree (14.3%) and a postgraduate degree (13.4%). Concerning the professional category, 75.0% were nurses; 24.1% were specialist nurses, and 1.0% were nurse managers. Most of the nurses had 11 or more years of professional experience (59.8%).

3.2. Sub-Dimensions and Items of Individualization Nursing Care

The principal component analysis (PCA) revealed key findings for the sub-dimensions of individualized nursing care. For the sub-dimension clinical situation, Cronbach's Alpha values were 0.862 for ICS-A-NURSE and 0.868 for ICS-B-NURSE, indicating excellent internal consistency (

Table 2 and

Table 3). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) values were 0.867 for ICS-A-NURSE and 0.877 for ICS-B-NURSE, suggesting an excellent correlation between the variables.

For the personal life situation sub-dimension, Cronbach's Alpha values were 0.748 for ICS-A-NURSE and 0.759 for ICS-B-NURSE, indicating good internal consistency. The KMO values were 0.697 for ICS-A-NURSE and 0.736 for ICS-B-NURSE, showing a moderated correlation between the variables.

The decisional control sub-dimension presented varied Cronbach's Alpha values: 0.684 for ICS-A-NURSE and 0.774 for ICS-B-NURSE (acceptable). The KMO values were 0.719 for ICS-A-NURSE and 0.829 for ICS-B-NURSE, indicating good adequacy, especially for ICS-B-NURSE.

These results indicate that the internal consistency of the indicators of the sub-dimensions was more robust for the clinical situation and decisional control (ICS-B-NURSE) than for the personal life situation and decisional control (ICS-A-NURSE). This suggests that nurses' perceptions of the individualization of care are more cohesive and well-defined in the dimensions related to clinical situations and decisional control than in the personal life situation of patients.

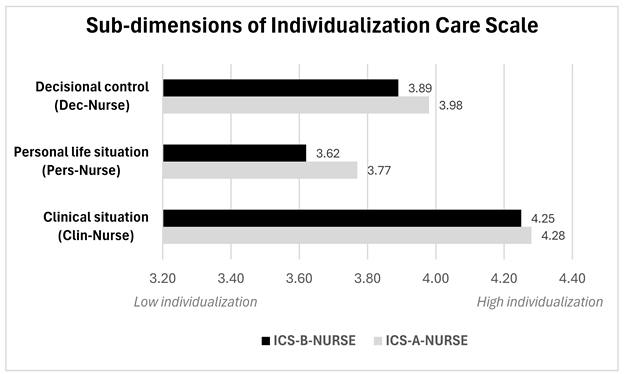

The results indicate that the ICS-A-NURSE group consistently reported higher levels of individualization across all three sub-dimensions compared to the ICS-B-NURSE group (Graphic 1). These results suggest that while nurses value the sub-dimensions of individualization in overall care, their incorporation into the most recent nursing shift was lower. The higher scores were obtained in the clinical situation sub-dimension (ICS-A-NURSE= 4.28 and ICS-B-NURSE=4.25), and the underscores in the inclusion of the aspects that contained personal life situation dimension (ICS-A-NURSE= 3.77 and ICS-B-NURSE=3.62).

Graphic Summary of the sub-dimensions of ICS-Nurse.

The highest-scoring items included "Instructions to patients" (ICS-A: 4.62; ICS-B: 4.37). "Needs that require care and attention" (ICS-A: 4.35; ICS-B 4.44). and "Feelings about illness/health condition" (ICS-A: 4.38; ICS-B 4.31), as shown the

Table 4.

Both responses to the scales had lower averages in items such as "Ask patients at what time they want to wash" (ICS-A: 3.21; ICS-B: 3.11). "Family to take part in their care" (ICS-A: 3.46; ICS-B: 3.55) and “Previous experiences of hospitalization” (ICS-A: 3.57; ICS-B 3.52), indicating areas for potential improvement in the individualization of nursing care. There is a need too for greater focus on patient participation in decisions (ICS-A: 3.93; ICS-B: 3.76) and understanding patients' daily habits (ICS-A: 3.09; ICS-B: 3.66).

The items that have intermediate ponderation were encouraging patients to express their opinions, giving them a chance to take responsibility as far as possible, understanding what they want to know about their illness or health condition, considering patients’ wishes regarding their care, exploring what the illness condition means to them, talking with patients about their fears and anxieties.

4. Discussion

The sociodemographic characteristics of nurses have been associated with the degree of individualization of the care they provide; however, in this study, no statistically significant differences were found. Nurses with more professional experience, advanced nursing education, or postgraduate qualifications tend to provide more individualized care [

30]. Nurses with more years of experience and higher education levels possess the skills and maturity needed to deliver tailored patient care effectively [

31]. Previous investigations have confirmed that higher levels of education, namely a master’s degree, among nurses. correlate with greater decision-making autonomy, which is crucial for integrating individualized care into their practice [

32,

33].

The Cronbach's alpha coefficient was reported for ICS-A-Nurse subscales as 0.88 (range 0.72–0.83). and 0.90 (range 0.73–0.84) for ICS-B-Nurse subscales as 0.88 in the study by Suhonen et al. [

18] and Cronbach's alpha coefficient total 0.91 in the research conducted by Acaroglu et al. [

34]. In a cross-cultural international study, the alpha coefficient for ICS-A was 0.88 and for ICS-B was 0.87 in Finland; ICS-A was 0.95 and ICS-B was 0.84 in Greece; ICS-A was 0.91 and ICS-B was 0.90 in Portugal; and ICS-A was 0.95 and ICS-B was 0.93 in the U.S.A. [

35]. In this study, the Cronbach's alpha values were 0.886 for ICS-A-NURSE and 0.905 for ICS-B-NURSE. These values are consistent with those found in the previous studies, suggesting that the scales used are reliable and internally consistent, additionally confirmed to the PCA, with all sub-dimensions KMO > 0.697 (p<.001). The high values of Cronbach's alpha in all these studies demonstrate that the items within each subscale and the overall scales are measuring the same underlying concept effectively.

The average score of 4.06 ± 0.46 obtained by nurses from ICS-A-NURSE indicates a good perception of individualized care among the participants. The ICS-B-NURSE presented a slightly lower score of 3.97 ± 0.Comparing these findings with other studies conducted in the Netherlands and Belgium, the nurses' mean scores obtained from the ICS-A-NURSE were higher (4.23 ± 0.58) [

36]. Turkish nurses' mean score obtained from the ICSA-Nurse was 3.96 ± 0.72 [

33]. Another study was conducted in Turkey with nurses working in intensive care, surgery, and internal medicine services at a state hospital. with a sample of 97 nurses. found that the mean score of total items of ICS-A for the nurses is 3.75±0.74 [

37].

ICS-A-NURSE demonstrated higher average scores across most evaluated items, which denotes an overall recognition by nurses of the need for individualized care, but difficulties in its translation to practice are evident in the ICS-B-NURSE, which provides important insights. This study found a greater emphasis on the sub-dimension Clinical Situation (ClinA and ClinB), which reflects a concern with integrating the current state of illness, how it affects the patient's physical, psychological, and emotional well-being, and what needs require intervention [

38,

39]. In contrast, other research places a bigger weight on Decisional Control (DecA), which facilitates patients in making their own choices about their care [

40,

41].

Feelings about health conditions received notably high scores, indicating a strong prominence on clear communication, attentiveness to patient needs, and emotional support. Babaei et al. [

42] found that emotional support and understanding patients' feelings about their illness are essential components of high-quality nursing care. Their study revealed that nurses who actively engage in empathetic communication and provide emotional support can significantly reduce patient anxiety and improve overall patient satisfaction. This approach not only helps in building trust and rapport between nurses and patients but also contributes to better adherence to treatment plans and faster recovery. The study also emphasized the importance of training nurses in emotional intelligence and communication skills to enhance their ability to deliver individualized care effectively.

The instructions provided to patients were a highly valued item, included in the sub-dimension of decisional capacity, which may be particularly associated with the promotion of self-care and self-management. This is a very relevant aspect of individualization in the control of multimorbidity, mainly in diabetes mellitus [

43]. The relatively low scores for asking patients about their preferred times for personal care routines like washing can reflect a lack of personalization in care schedules. This omission can lead to decreased patient satisfaction and a sense of autonomy, which are vital for recovery and overall well-being. A low level of individualized care results in insufficient identification of the person’s needs, contributing to missed nursing care [

44]. High rates of missed nursing care have been documented. ranging from 52% to 86% [

45,

46]. Ergezen et al. [

47] research has shown that emotional support, patient bathing, and ambulation are the nursing care activities most often overlooked. Nurses should recognize the person as responsible for their own life and health project, endowed with the power to make decisions and with the right to participate in their care [

7].

Incorporating family into patient care had one of the worst scores. Family involvement is a key component of patient-centered care, contributing to better management of chronic conditions, improving patient compliance, and enhancing emotional support [

48]. Wong et al. [

49]. developed and evaluated a multidisciplinary intervention for patients undergoing surgery, which included patient education and family integration into care, and concluded that it improved health literacy for both. However, when nurses do not adequately involve families, it can lead to increased stress for the patient and a potential decline in the quality of care, verified in perioperative and critical care [

50,

51]. Kiston et al. [

52] argue that a care biography is vital to nursing fundamental care. It guarantees life and well-being because it considers a personalized account of an individual's self-care abilities, capacity for care, family relationships, and understanding of the care they receive and expect from others. Like a personalized health record, a care biography tracks a person's self-care skills, preferences, and needs throughout their life, as confirmed by Ramos et al. [

53] and Fonseca et al. [

54]. Fundamental care encompasses the essential support required for everyone to ensure survival, maintenance, protection, or a peaceful end, regardless of their clinical condition or care environment [

52]. When the provision of fundamental care is inadequate, it negatively affects patients, families or caregivers, healthcare professionals, and the overall healthcare system [

55,

56]. It also contributes to the risk of adverse events, once planned or recommended care isn’t implemented [

57].

5. Limitations of the Study

The study’s cross-sectional nature provides only a view of individualized nursing care at one point in time, limiting the ability to assess changes or trends over time. The sample is not representative of all acute medical and perioperative settings, because it was non-probabilistic, which does not allow generalization. Furthermore, the sample did not follow a normal distribution, so the use of parametric statistical tests was not possible, and it would have been more robust.

6. Conclusions

Future efforts should focus on addressing the gaps identified to improve individualized care. This includes adopting more flexible scheduling practices to accommodate patient preferences, enhancing family involvement in care processes, and fostering a more participatory approach to decision-making. The aspects most integrated and valued by nurses in acute medical and perioperative care were instructions to patients, needs that require care and attention, feelings about illness/health condition, and how their health condition affects them, highlighting an emphasis on the physical and psycho-emotional dimensions. In nurses' perceptions of individualized care, no statistically significant differences were found in the newly included contexts, such as the operating room and emergency settings

Furthermore, continuous professional development and training programs emphasizing these aspects can further strengthen the implementation of individualized care practices. Integrating these improvements can lead to better patient outcomes, reduced missed care, increased satisfaction, and overall improved quality of care.

We suggest conducting future studies that incorporate the perspectives of patients in acute and perioperative care for comparative analysis with the views of nurses. The integration of qualitative study designs is recommended to identify better factors that influence the individualization of nursing care. Additionally, pilot studies should be undertaken to demonstrate the effectiveness of individualized care in the health conditions of populations.

Author Contributions

Writing – original draft, A.R, S.P, E.S, I.G, E.A, C.F., and A.C; Writing – review & editing, A.R, S.P, E.S, I.G, E.A, C.F., and A.C; Investigation, A.R, S.P, E.S, I.G; Validation, E.S, I.G, E.A, C.F., and A.C; Methodolo3gy, A.R, S.P, E.S, I.G, E.A, C.F., and A.C; Conceptualization A.R, S.P, E.S, and I.G; Project administration, E.S, and I.G; Funding acquisition, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Fundação Ciência e Tecnologia, IP national support through CHRC (UIDP/04923/2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was conducted in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration guidelines. This research was submitted and accepted by the Health Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Center, where the research was conducted: I/25010/2023 (16/11/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all the study participants.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Ageing and health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and- (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- EUROSTAT. Archive: Estrutura populacional e envelhecimento. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Archive:Estrutura_populacional_e_envelhecimento&oldid=510113 (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- PORDATA. Esperança de vida à nascença: total e por sexo (base: triénio a partir de 2001). Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/portugal/esperanca+de+vida+aos+65+anos+total+e+por+sexo+(base+trienio+a+partir+de+2001)-419 (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- PORDATA. Índice de dependência de idosos. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/Municipios/%C3%8Dndice+de+depend%C3%AAncia+de+idosos-461 (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Storeng SH, Vinjerui KH, Sund ER, Krokstad S. Associations between complex multimorbidity, activities of daily living and mortality among older Norwegians. A prospective cohort study: the HUNT Study, Norway. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):Published 2020 Jan 21. [CrossRef]

- Meleis, A. Theoretical Nursing Development & Progress, 5th edition, Lippincott William & Wilkins, Wolters Kluwer, Philadelphia, 2012.

- Gomes, I. Partnership of Care in the Promotion of the Care-of-the-Self: An Implementation Guide with Elderly People, In: García-Alonso J., Fonseca C. (eds) Gerontechnology III. IWoG Lecture Notes in Bioengineering. Springer, Cham, 2021, p. 345 – 356.

- World Health Organization (WHO). The international classification of functioning, disability and health, World Health Organization, Geneva, 2001.

- Zhang, L., & Pan, W. Effect of a nursing intervention strategy oriented by Orem's self-care theory on the recovery of gastrointestinal function in patients after colon cancer surgery. American journal of translational research. 2021, 13(7), 8010–8020.

- Yu H, Wu L. Analysis of the Effects of Evidence-Based Nursing Interventions on Promoting Functional Recovery in Neurology and General Surgery Intensive Care Patients. Altern Ther Health Med. 2024.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Quality health services. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/quality-health-services (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Chowdhury, S. R., Chandra Das, D., Sunna, T. C., Beyene, J., & Hossain. A. Global and regional prevalence of multimorbidity in the adult population in community settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2023, 57, 101860. [CrossRef]

- Suhonen, R., Välimäki, M., & Leino-Kilpi, H. "Individualised care" from patients', nurses' and relatives' perspective: a review of the literature. International journal of nursing studies. 2002, 39(6)) 645–654. [CrossRef]

- Suhonen, R. , Leino-Kilpi, H., & Välimäki, M. Development and psychometric properties of the Individualized Care Scale, Journal of evaluation in clinical practice. 2005, 11(1), 7–20. [CrossRef]

- Suhonen, R. , Stolt, M., & Papastavrou, E. Individualized care theory, measurement, research and practice; Springer International Publishing, New York, 2019.

- Suhonen, R., Stolt, M., & Edvardsson, D. Personalized Nursing and Health Care: Advancing Positive Patient Outcomes in Complex and Multilevel Care Environments. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2022, 12, 1801.

- Byrne, A. L., Baldwin, A., & Harvey, C. Whose centre is it anyway? Defining person-centered care in nursing: An integrative review. PLoS One. 2020, 15(3), e0229923. [CrossRef]

- Suhonen, R., Gustafsson, M. L., Katajisto, J., Välimäki, M., & Leino-Kilpi, H. Nurses' perceptions of individualized care. Journal of advanced nursing. 2010, 66(5), 1035–1046. [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A. F., Ferreira P. L., & Suhonen, R. Translation and Validation of the Individualized Care Scale. International Journal of Caring Sciences. 2014, 7(1), 90–101.

- Hu Y, Zhu N, Wen B, Dong H. Individualized Nursing Interventions in Patients with Comorbid Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Chronic Heart Failure. Altern Ther Health Med. 2023, 29(8), 329-333.

- He, J. , Dai, F., Liao, H., & Fan, J. Effect of individualized nursing intervention after percutaneous coronary intervention, International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 2019, 12(6), 7434-7441. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/doi/10.1002/central/CN-02002874/full.

- FIirat Kiliç, H., Sü, S., & Gk, N. D. Perceived Individualized Care and the Satisfaction Levels of Patients Hospitalized in Internal Medicine Departments: A Cross-Sectional and Correlational Survey. Clinical and Experimental Health Sciences. 2022, 12(2), 454–461. [CrossRef]

- Suhonen, R. , Välimäki, M., & Leino-Kilpi, H. Hospitals' organizational variables and patients' perceptions of individualized nursing care in Finland. Journal of Nursing Management. 2007, 15(2), 197-206. [CrossRef]

- Bagnasco, A., Dasso, N., Rossi, S., Galanti, C., Varone, G., Catania, G., Zanini, M., Aleo, G., Watson, R., Hayter, M., & Sasso, L. Unmet nursing care needs on medical and surgical wards: A scoping review of patients' perspectives. Journal of clinical nursing. 2020, 29(3-4), 347–369. [CrossRef]

- Beach, S. R., Schulz, R., Friedman, E. M., Rodakowski, J., Martsolf, R. G., & James, A. E. Adverse Consequences of Unmet Needs for Care in High-Need/High-Cost Older Adults. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences. 2020, 75(2), 459–470. [CrossRef]

- Bankole, A. O. , Girdwood, T., Leeman, J., Womack, J., & Toles, M. Identifying unmet needs of older adults transitioning from home health care to independence at home: A qualitative study. Geriatric nursing. 2023, 51, 293–302. [CrossRef]

- Marôco, J. Análise estatística com o PASW Statistics,ReportNumber, Lda, Lisboa 2021.

- Peterson. R. A. A meta-analysis of Cronbach's coefficient alpha, Journal of Consumer Research. 1994, 21(2), 381-391. [CrossRef]

- Kruskal. W. H. & Wallis. W. A. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1952, 47(260), 583-621. [CrossRef]

- Danaci E, Koç Z. The association of job satisfaction and burnout with individualized care perceptions in nurses. Nurs Ethics. 2020, 27(1), 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idvall, E., Berg, A., Katajisto, J., Acaroglu, R., Luz, M. D., Efstathiou, G., Kalafati, M., Kanan, N., Leino-Kilpi, H., Lemonidou, C., Papastavrou, E., Sendir, M., & Suhonen, R. Nurses' sociodemographic background and assessments of individualized care. Journal of nursing scholarship. 2012, 44(3), 284–293. [CrossRef]

- Avci. D. & Yilmaz. F. A. Association between Turkish clinical nurses' perceptions of individualized care and empathic tendencies. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2021, 57(2), 524–530. [CrossRef]

- Yildirim. G. Kaya. N. & Altunbas. N. Relationship between nurses' perceptions of conscience and perceptions of individualized nursing care: A cross-sectional study. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2021, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Acaroglu, R., Suhonen, R., Sendir, M., & Kaya, H. Reliability and validity of Turkish version of the Individualized Care Scale. J Clin Nurs. 2011, 20(12), 136-145.

- Antunes. D. Batuca C. Ramos A. Fonseca C. Ferreira M. Suhonen R. Papastavrou E. Lemonidou C. Idvall E. Acaroglu R. Sousa VD. Estudo comparativo transcultural internacional sobre as perceções dos enfermeiros em relação aos cuidados de enfermagem individualizados. Revista Investigação Em Enfermagem. 2011, 7(15), 7-15.

- Theys. S. Van Hecke. A. Akkermans. R. & Heinen. M. The Dutch Individualised Care Scale for patients and nurses - a psychometric validation study. Scandinavian journal of caring sciences. 2021, 35(1), 308–318. [CrossRef]

- Tok Yildiz. F. Cingol. N. Yildiz. I. & Kasikcki. M. Nurses’ Perceptions of Individualized Care: A Sample from Turkey. International Journal of Caring Sciences. 2018, 246–253.

- Sá, E., & Romão, R. A pessoa com doença hemato-oncológica. Que modelo de cuidados. OncoNews, 2015, 28, 20-28.

- Karayurt Ö, Erol Ursavaş, F, İşeri Ö. Examination of the status of nurses to provide individualized care and their opinions. Acıbadem University Health Sciences Journal. 2018, 9(2), 163169.

- Dogan, P. , Tarhan, M., & Kurklu, A. The relationship between individualized care perceptions and moral sensitivity levels of nursing students. Journal of Education and Research in Nursing. 2019, 16(2), 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Can, Ş. The relationship between the individualized care perceptions of nurses and their professional commitment: Results from a descriptive correlational study in Turkey. Nurse Education in Practice. 2021, 55, 0–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babaei, S., Taleghani, F., & Farzi, S. Components of Compassionate Care in Nurses Working in the Cardiac Wards: A Descriptive Qualitative Study. Journal of caring sciences. 2022, 11(4), 239–245. [CrossRef]

- Bartkeviciute. B. Lesauskaite. V. & Riklikiene. O. Individualized Health Care for Older Diabetes Patients from the Perspective of Health Professionals and Service Consumers. Journal of personalized medicine. 2021, 11(7), 608. [CrossRef]

- Papastavrou, E. & Suhonen, R. Impacts of rationing and missed nursing care: challenges and solutions: RANCARE Action, Springer, New York, 2021.

- Saar. L. Unbeck. M. Bachnick. S. Gehri. B. & Simon. M. Exploring omissions in nursing care using retrospective chart review: An observational study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2021, 122. 104009. [CrossRef]

- Simonetti. M. Ceron. C. Galiano. A. Lake. E. T. & Aiken. L. H. Hospital work environment. nurse staffing and missed care in Chile: A cross-sectional observational study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2021, 31(17–18), 2518–2529. [CrossRef]

- Ergezen. F. Çiftçi. B. Yalın. H. Geçkil. E. Korkmaz Doğdu. A. İlter. S. M. Terzi. B. Kol. E. Kaşıkçı. M. & Ecevit Alpar. Ş., Missed nursing care: A cross-sectional and multi-centric study from Turkey. International journal of nursing practice. 2023, 29(5), e13187. [CrossRef]

- Park. M. Giap. T.-T.-T. Lee. M. Jeong. H. Jeong. M. Go. Y. Patient and family- centered care interventions for improving the quality of health care: A review of systematic reviews. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 87, 69–83.

- Wong. J. Mulamira. P. Arizu. J. Nabwire. M. Mugabi. D. Nabulime. S. Driwaru. D. Nankya. E. Batumba. R. Hagara. A. Okoth. A. Lindan Namugga. J. Ajeani. J. Nakisige. C. Ueda. S. M. Havrilesky. L. J. & Lee. P. S. Standardization of caregiver and nursing perioperative care on gynecologic oncology wards in a resource-limited setting. Gynecologic oncology reports. 2021, 39, 100915. [CrossRef]

- Alsabban. W. Alhadithi. A. Alhumaidi. F. S. Al Khudhair. A. M. Altheeb. S. & Badri. A. S. Assessing needs of patients and families during the perioperative period at King Abdullah Medical City. Perioperative medicine. 2020, 9, 10. [CrossRef]

- Bohart. S. Møller. A. M. Andreasen. A. S. Waldau. T. Lamprecht. C. & Thomsen. T. Effect of Patient and Family Centred Care interventions for adult intensive care unit patients and their families: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive & critical care nursing. 2022, 69, 103156. [CrossRef]

- Kitson. A. Feo. R. Lawless. M. Arciuli. J. Clark. R. Golley. R. Lange. B. Ratcliffe. J. & Robinson. S. Towards a unifying caring life-course theory for better self-care and caring solutions: A discussion paper. Journal of advanced nursing. 2022, 78(1), e6–e20. [CrossRef]

- Ramos. A. Fonseca. C. Pinho. L. Lopes. M. Brites. R. & Henriques. A. Assessment of Functioning in Older Adults Hospitalized in Long-Term Care in Portugal: Analysis of a Big Data. Frontiers in medicine. 2022, 9, 780364. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca. C. Ramos. A. Morgado. B. Quaresma. P. Garcia-Alonso. J. Coelho. A. & Lopes. M. Long-term care units: a Portuguese study about the functional profile. Frontiers in aging. 2023, 4, 1192718. [CrossRef]

- Kitson, A., Carr, D., Feo, R., Conroy, T., & Jeffs, L. The ILC Maine statement: Time for the fundamental care [r]evolution. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2024, 00, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A., Leone, C., Ribeiro, V., Sá Moreira, P., & Dussault, G. Integrated disease management: a critical review of foreign and Portuguese experience. Acta medica portuguesa. 2014, 27(1), 116–125. [CrossRef]

- Aiken. L. H. Sloane. D. M. Bruyneel. L. Van den Heede. K. & Sermeus. W. Nurses' reports of working conditions and hospital quality of care in 12 countries in Europe. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2013, 50(2), 143–153.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of nurses in acute medical and perioperative settings.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of nurses in acute medical and perioperative settings.

| Settings of care |

Ophthalmology |

Medicine |

Cardiology |

Medical emergency unit |

Total |

| |

N (%) |

N (%) |

N (%) |

N (%) |

N (%) |

| Age category (years) |

|---|

| ≤ 25 |

0 (0.0) |

2 (1.8) |

5 (4.5) |

9 (8.0) |

16 (14.3) |

| 26 – 30 |

0 (0.0) |

8 (7.1) |

5 (4.5) |

8 (7.1) |

21 (18.8) |

| 31 – 35 |

1 (0.9) |

3 (2.7) |

3 (2.7) |

1 (0.9) |

8 (7.1) |

| 36 – 40 |

5 (4.5) |

5 (4.5) |

5 (4.5) |

9 (8.0) |

24 (21.4) |

| 41 – 50 |

3 (2.7) |

8 (7.1) |

3 (2.7) |

6 (5.4) |

20 (17.9) |

| ≥ 51 |

7 (6.3) |

4 (3.6) |

6 (5.4) |

6 (5.4) |

23 (20.5) |

| Sex |

| Female |

12 (12.5) |

26 (23.2) |

20 (17.9) |

32 (28.6) |

92 (82.1) |

| Male |

2 (1.8) |

4 (3.6) |

7 (6.3) |

7 (6.3) |

20 (17.9) |

| Level of education |

| Undergraduate degree |

12 (10.7) |

22 (19.6) |

20 (17.9) |

27 (24.1) |

81 (72.3) |

| Postgraduate |

2 (1.8) |

7 (6.3) |

2 (1.8) |

4 (3.6) |

15 (13.4) |

| Master |

2 (1.8) |

1 (0.9) |

5 (4.5) |

8 (7.1) |

16 (14.3) |

| Professional category |

| Nurse |

13 (11.6) |

21 (18.8) |

21 (18.8) |

29 (25.9) |

84 (75.0) |

| Specialized nurse |

3 (2.7) |

9 (8.0) |

6 (5.4) |

9 (8.0) |

27 (24.1) |

| Nurse manager |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (0.9) |

1 (0.9) |

| Professional experience (years) |

| ≤ 2 |

0 (0.0) |

3 (2.7) |

5 (4.5) |

10 (8.9) |

18 (16.1) |

| 3 – 5 |

0 (0.0) |

6 (5.4) |

3 (2.7) |

4 (3.6) |

13 (11.6) |

| 6 – 10 |

1 (0.9) |

3 (2.7) |

5 (4.5) |

5 (4.5) |

14 (12.5) |

| ≥ 11 |

15 (13.4) |

18 (16.1) |

14 (12.5) |

20 (17.9) |

67 (59.8) |

| Total |

16 (14.3) |

30 (26.8) |

27 (24.1) |

39 (34.8) |

112 (100.0) |

Table 2.

Analysis of the main components of ICS-A-NURSE and alpha coefficients (N= 112).

Table 2.

Analysis of the main components of ICS-A-NURSE and alpha coefficients (N= 112).

| ITEMS CONTENT |

Component Matrix |

h2 |

| ICS-A-NURSE |

Clinical situation (Clin-Nurse) |

|

| Feelings about illness/health condition |

.827 |

|

|

.706 |

| Needs that require care and attention |

.842 |

|

|

.563 |

| Chance to take responsibility as far as possible |

.857 |

|

|

.445 |

| Identify changes in how they have felt |

.847 |

|

|

.506 |

| Talk with patients about fears and anxieties |

.835 |

|

|

.628 |

| Find out how their health condition affects them |

.844 |

|

|

.528 |

| What the illness /health condition means to them |

.847 |

|

|

.522 |

| |

Personal life situation (Person-Nurse) |

|

| What kind of things they do in their everyday life |

|

.689 |

|

.606 |

| Previous experiences of hospitalization |

|

.733 |

|

.475 |

| Everyday habits |

|

.592 |

|

.774 |

| Family to take part in their care |

|

.735 |

|

.464 |

| |

Decisional control (Dec-Nurse) |

|

| Instructions to patients |

|

|

.687 |

.617 |

| What they want to know about illness/health condition |

|

|

.669 |

.559 |

| Patients’ wishes regarding their care |

|

|

.619 |

.598 |

| Help patients take part in decisions |

|

|

.613 |

.671 |

| Encourage patients to express their opinions |

|

|

.592 |

.585 |

| Ask patients at what time they want to wash |

|

|

.671 |

.530 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha |

.862 |

.748 |

.684 |

.886 |

|

Kaiser- Meyer-Olkin |

.867 |

.697 |

.719 |

|

| Bartlett's Test of Sphericity |

321.380 |

118.334 |

122.062 |

|

| 21 |

6 |

15 |

|

| <.001 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

|

Table 3.

Analysis of the main components of ICS-B-NURSE and alpha coefficients (N= 112).

Table 3.

Analysis of the main components of ICS-B-NURSE and alpha coefficients (N= 112).

| ITENS CONTENT |

Component Matrix |

h2 |

| ICS-B-NURSE |

Clinical situation (Clin-Nurse) |

|

| Feelings about illness/health condition |

.842 |

|

|

.635 |

| Needs that require care and attention |

.844 |

|

|

.627 |

| Chance to take responsibility as far as possible |

.898 |

|

|

.241 |

| Identify changes in how they have felt |

.837 |

|

|

.681 |

| Talk with patients about fears and anxieties |

.840 |

|

|

.682 |

| Find out how their health condition affects them |

.843 |

|

|

.647 |

| What the illness /health condition means to them |

.841 |

|

|

.654 |

| |

Personal life situation (Person-Nurse) |

|

| What kind of things they do in their everyday life |

|

.638 |

|

.736 |

| Previous experiences of hospitalization |

|

.663 |

|

.695 |

| Everyday habits |

|

.687 |

|

.626 |

| Family to take part in their care |

|

.806 |

|

.320 |

| |

Decisional control (Dec-Nurse) |

|

| Instructions to patients |

|

|

.744 |

.485 |

| What they want to know about illness/health condition |

|

|

.730 |

.538 |

| Patients’ wishes regarding their care |

|

|

.729 |

.573 |

| Help patients take part in decisions |

|

|

.701 |

.668 |

| Encourage patients to express their opinions |

|

|

.711 |

.633 |

| Ask patients at what time they want to wash |

|

|

.824 |

.177 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha |

.868 |

.759 |

.774 |

.905 |

|

Kaiser- Meyer-Olkin |

.877 |

.736 |

.829 |

|

| Bartlett's Test of Sphericity |

392.166 |

128.400 |

199.846 |

|

| 21 |

6 |

15 |

|

| <.001 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

|

Table 4.

Description of ICS-Nurse items.

Table 4.

Description of ICS-Nurse items.

| ITEMS |

ICS-A-NURSE |

ICS-B-NURSE |

| |

Mean± SD

|

Median |

Range |

Mean± SD

|

Median |

Range |

| Clinical situation (Clin-Nurse) |

| Feelings about illness/health condition |

4.38 ± .602 |

4 |

2 -5 |

4.31 ± .658 |

4 |

2 - 5 |

| Needs that require care and attention |

4.45 ± .551 |

4 |

3 -5 |

4.44 ± .582 |

4 |

3 – 5 |

| Chance to take responsibility as far as possible |

4.19 ± .704 |

4 |

2 -5 |

3.95 ± .909 |

4 |

1 – 5 |

| Identify changes in how they have felt |

4.23 ± .585 |

4 |

3 -5 |

4.29 ± .653 |

4 |

3 – 5 |

| Talk with patients about fears and anxieties |

4.32 ± .647 |

4 |

2 -5 |

4.24 ± .661 |

4 |

3 – 5 |

| Find out how their health condition affects them |

4.36 ± .656 |

4 |

2 -5 |

4.29 ± .653 |

4 |

3 – 5 |

| What the illness /health condition means to them |

4.05 ± .733 |

4 |

2 -5 |

4.21 ± .659 |

4 |

3 – 5 |

| Personal life situation (Person-Nurse) |

| What kind of things they do in their everyday life |

4.16 ± .789 |

4 |

2 – 5 |

3.73 ± .939 |

4 |

2 – 5 |

| Previous experiences of hospitalisation |

3.57 ± .984 |

4 |

1 – 5 |

3.52 ± .986 |

4 |

1 – 5 |

| Everyday habits |

3.90 ± .920 |

4 |

2 – 5 |

3.66 ± .876 |

4 |

1 - 5 |

| Family to take part in their care |

3.46 ± .958 |

4 |

1 – 5 |

3.55 ± 1.02 |

4 |

1 – 5 |

| Decisional control (Dec-Nurse) |

| Instructions to patients |

4.62 ± .524 |

5 |

3 – 5 |

4.37 ± .615 |

4 |

3 – 5 |

| What they want to know about illness/health condition |

4.02 ± .849 |

4 |

2 - 5 |

4.06 ± .763 |

4 |

1 – 5 |

| Patients’ wishes regarding their care |

4.17 ± .599 |

4 |

3 – 5 |

4.11 ± .662 |

4 |

2 – 5 |

| Help patients take part in decisions |

3.93 ± .791 |

4 |

2 – 5 |

3.76 ± .713 |

4 |

2 – 5 |

| Encourage patients to express their opinions |

3.93 ± .824 |

4 |

2 – 5 |

3.94 ± .675 |

4 |

2 – 5 |

| Ask patients at what time they want to wash |

3.21 ± 1.08 |

3 |

1 – 5 |

3.11 ± 1.02 |

3 |

- 5 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).