Submitted:

18 September 2024

Posted:

19 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

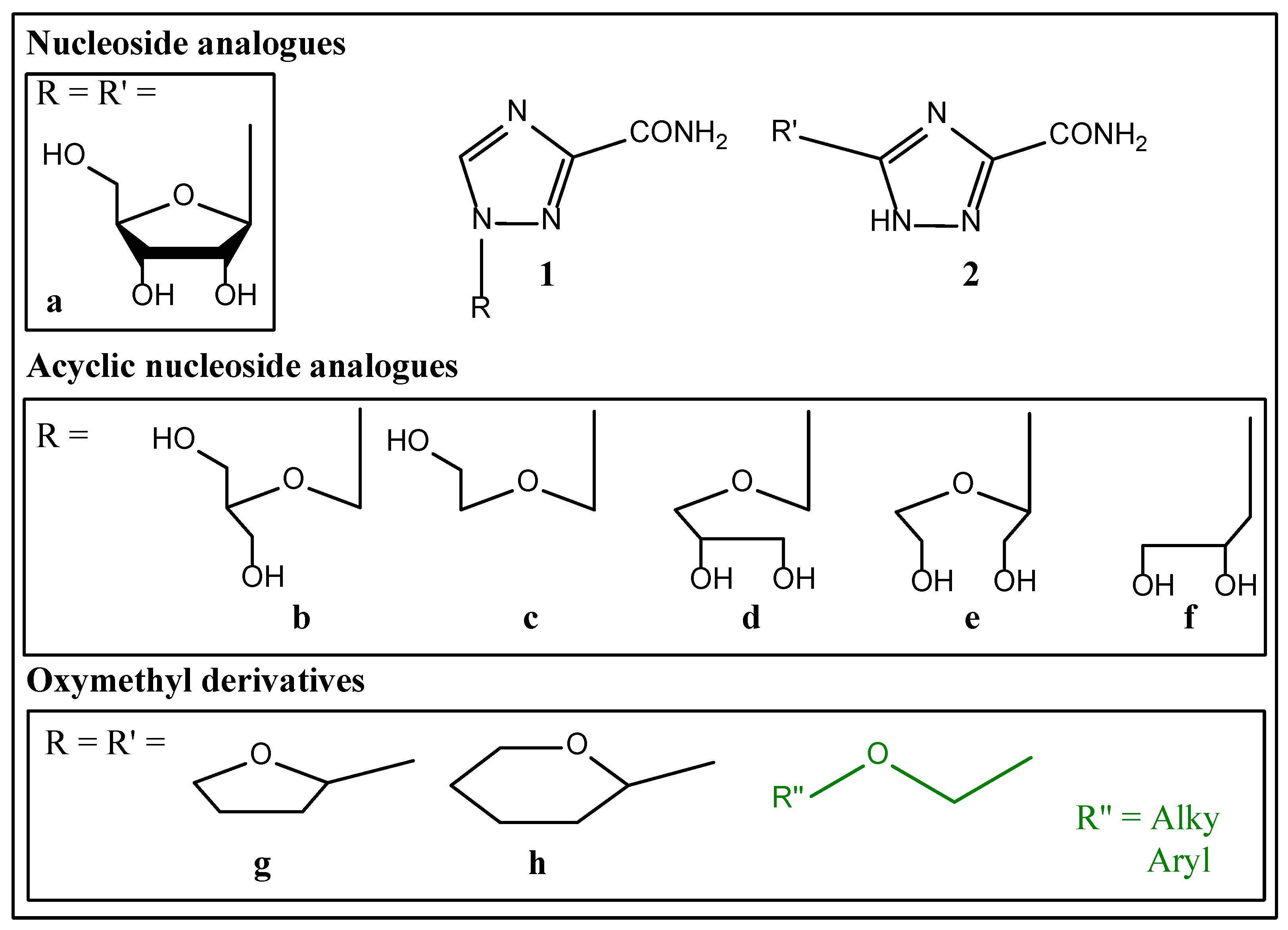

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussions

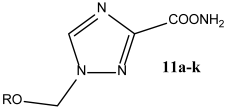

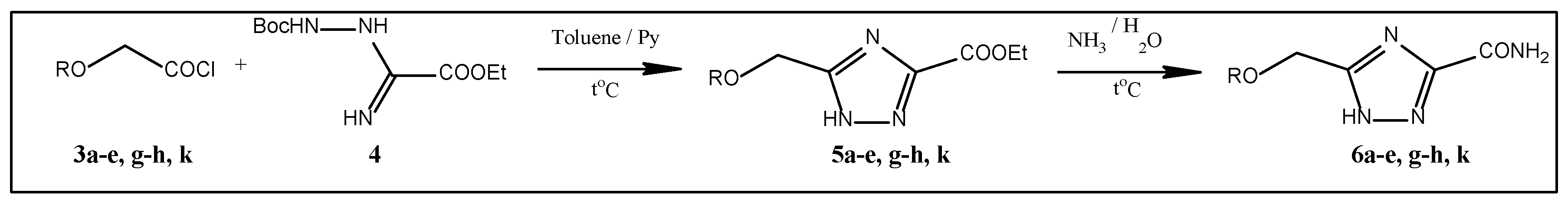

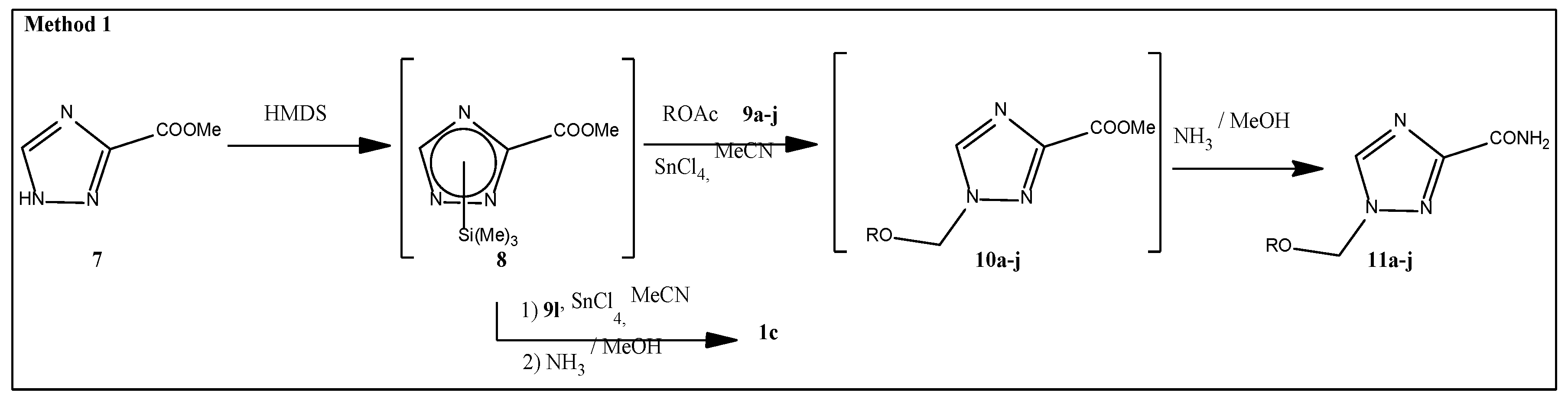

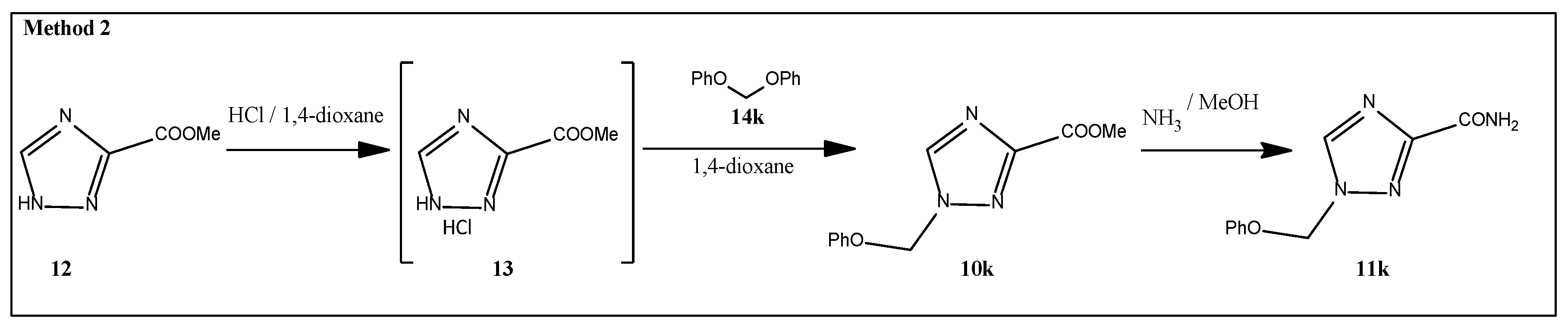

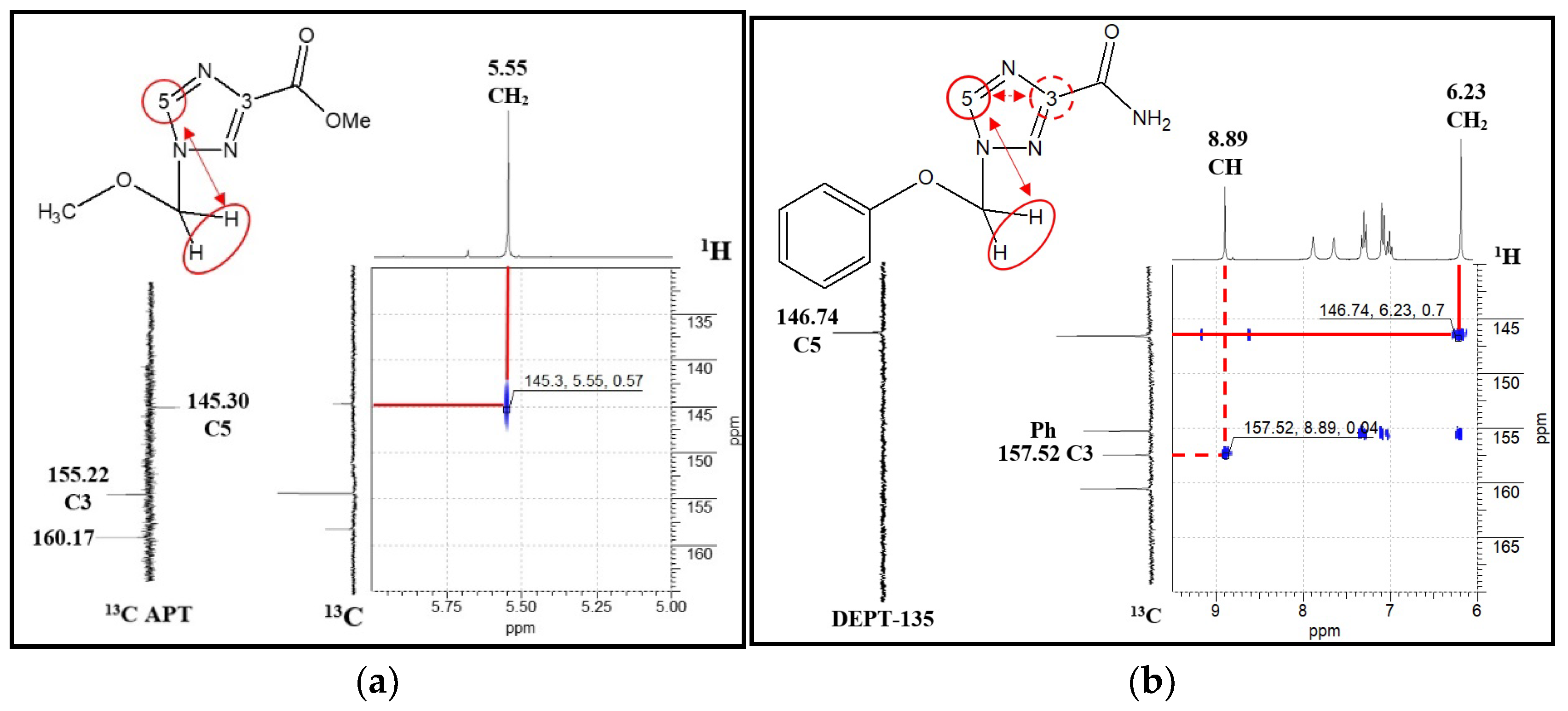

2.1. Synthesis

|

||

| S. No. | R | Yield |

| 11a | Me | 87% |

| 11b | Et | 78% |

| 11c | n-Pr | 78% |

| 11d | i-Pr | 91% |

| 11e | n-Bu | 81% |

| 11f | t-Bu | 49% |

| 11g | n-C10H21 | 78% |

| 11h | Bn | 89% |

| 11i | cyclo-C5H10 | 82% |

| 11j | cyclo-C6H12 | 53% |

| 11k | Ph | 52% |

| 1c | HO(CH2)2 | 83% |

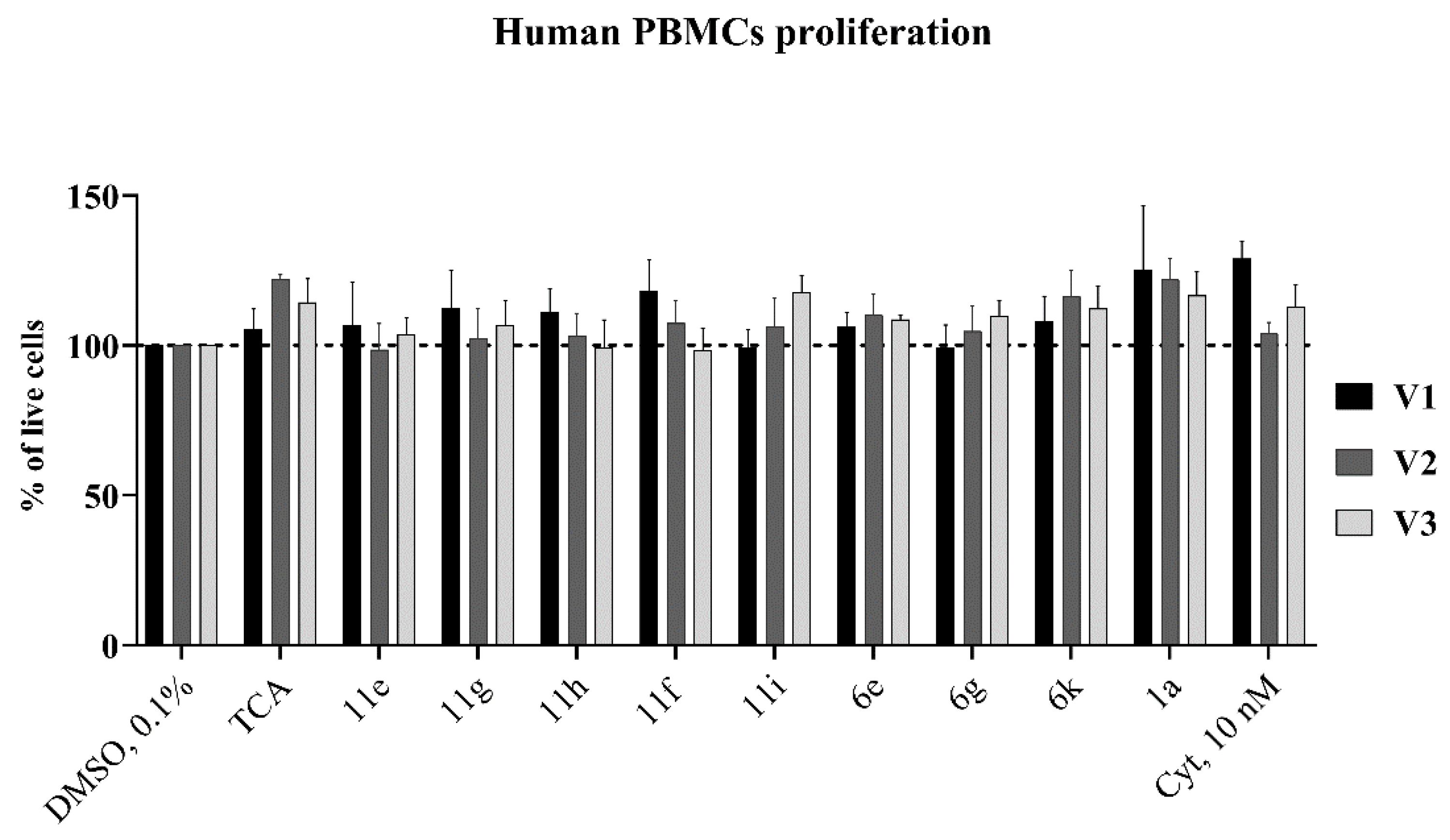

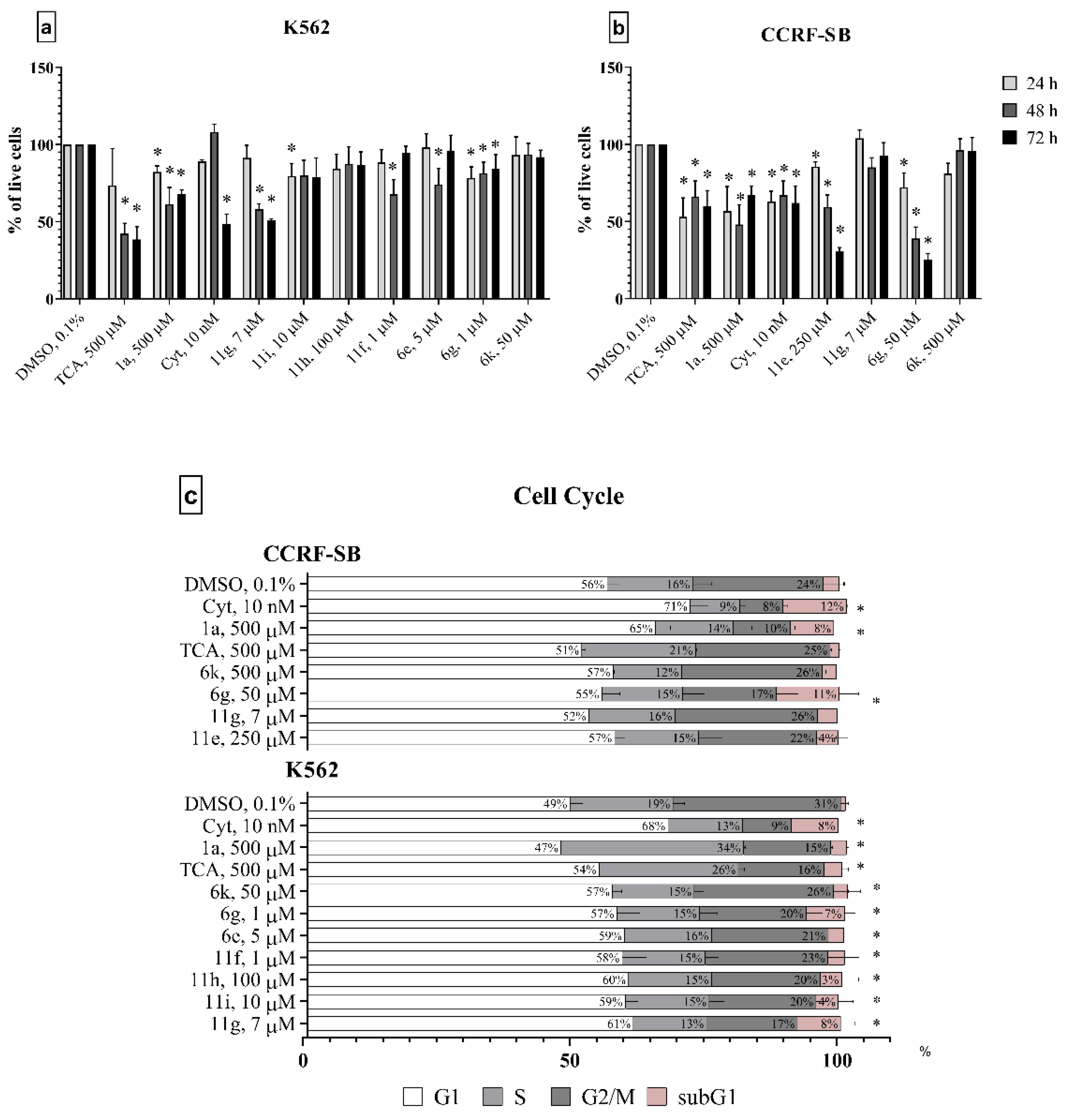

2.2. In Vitro Stu

2.2.1. Anti-Cancer Activity In Vitro

2.2.2. Antimicrobial Effects Studies

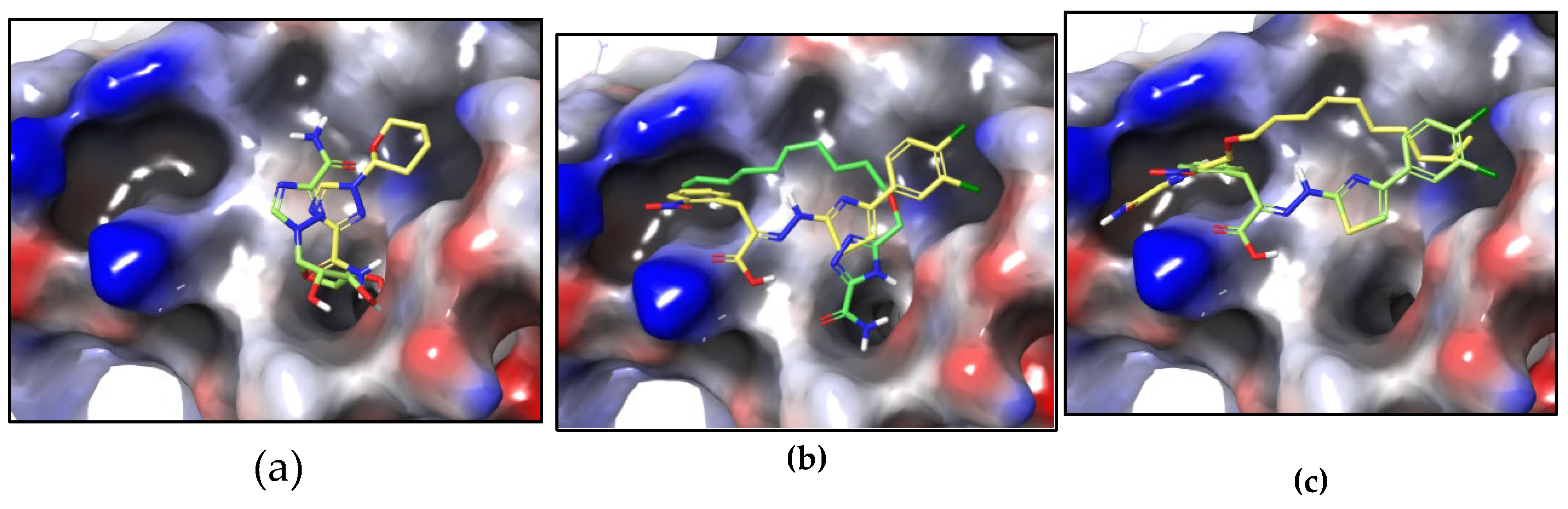

2.3. Molecular Docking

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthetic Section

3.1.1. 5-(n-Propoxymethyl)-1,2,4-Triazole-3-Carboxamide 6c

3.1.2. Methyl 1-(Methoxymethyl)-1,2,4-Triazole-3-Carboxylate (10a)

3.1.3. 1-(Methoxymethyl)-1,2,4-Triazole-3-Carboxamide (11a)

3.1.4. General Procedure for the Preparation of 1-Substituted of 1,2,4-Triazole-3-Carboxamides 11b-j, 1c

3.1.5. Methyl 1-(Phenoxymethyl)-1,2,4-Triazole-3-Carboxylate (10k)

3.2. Antiproliferative Assays

3.2.1. Cell Cultures

3.2.2. MTT Assay

3.2.3. Cell Proliferation

3.2.4. Cell Cycle

3.2.5. Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) Isolation and Culture

3.3. Antimicrobial Assays

3.4. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chudinov, M.V. Ribavirin and its analogues: Сan you teach an old dog new tricks? Fine Chemical Technologies. 2019, 14, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, S. Anti-HCV and Zika activities of ribavirin C-nucleosides analogues. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2022, 68, 116850–116858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardushkin, M.V.; Shiryaeva, Y.K.; Donskaya, L.; Vifor, R.; Donina, M.V. Colloid-Chemical and Antimicrobial Properties of Ribavirin Aqueous Solutions. Sys Rev Pharm. 2020, 11, 2050–2053. [Google Scholar]

- Assouline, S.; Culjkovic-Kraljacic, B.; Bergeron, J.; Caplan, S.; Cocolakis, E.; Lambert, C.; Borden, K.L.B. A phase I trial of ribavirin and low-dose cytarabine for the treatment of relapsed and refractory acute myeloid leukemia with elevated eIF4E. Haematologica. 2014, 100, e7–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, H.; Roh, J.; Venteicher, B.; Chandra, S.; Thomas, A.A. Synthesis of ribavirin 1,2,3- and 1,2,4-triazolyl analogs with changes at the amide and cytotoxicity in breast cancer cell lines. Nucleosides, Nucleotides & Nucleic Acids. 2020, 42, 38–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bózsity, N.; Minorics, R.; Szabó, J.; Mernyák, E.; Schneider, G.; Wölfling, J.; Wang, Н.С.; Wuc, С.С.; Ocsovszki, I.; Zupkó, I. Mechanism of antiproliferative action of a new d -secoestrone-triazole derivative in cervical cancer cells and its effect on cancer cell motility. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017, 165, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, J.; Bacsa, I.; Wölfling, J.; Schneider, G.; Zupkó, I.; Varga, M.; Hermab, B.E.; Kalmar, L.; Szecsi, M.; Mernyák, E. Synthesis and in vitro pharmacological evaluation of N-[(1-benzyl-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl]-carboxamides on d-secoestrone scaffolds. J. Enzym Inhib. 2015, 31, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilovaisky, A.I.; Scherbakov, A.M.; Chernoburova, E.A.; Povarov, A.A.; Shchetinina, M.A.; Merkulova, V.M.; Salnikova, D.I.; Sorokin, D.V.; Bozhenko, E.I.; Zavarzin, I.V.; Terentev, A.O. Secosteroid thiosemicarbazides and secosteroid–1,2,4-triazoles as antiproliferative agents targeting breast cancer cells: Synthesis and biological evaluation. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2023, 234, e1–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhidkova, E.; Stepanycheva, D.; Grebenkina, L.; Mikhina, E.; Maksimova, V.; Grigoreva, D.; Matveev, A.; Lesovaya, E. Synthetic 1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamides Induce Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in Leukemia Cells. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2023, 29, 3478–3487. [Google Scholar]

- Wittine, K.; Stipković, B.M.; Makuc, D.; Plavec, J.; Kraljević, P.S.; Sedić, M.; Pavelić, K.; Leyssen, P.; Neyts, J.; Balzarini, J.; Mintas, M. Novel 1,2,4-triazole and imidazole derivatives of L-ascorbic and imino-ascorbic acid: Synthesis, anti-HCV and antitumor activity evaluations. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 3675–3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, G.Y.; Robins, R.K.; Revankar, G.R. Synthetic Studies on the Isomeric N-Methyl Derivatives of C-Ribavirin. Nucleosides and Nucleotides. 1991, 10, 1707–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.Q.; Xia, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.H.; Rocchi, P.; Yao, J.H.; Qu, F.Q.; Neyts, J.; Iovanna, J.L.; Peng, L. Discovery of novel arylethynyltriazole ribonucleosides with selective and effective antiviral and antiproliferative activity. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, e1144–e1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, R.Z.; Wang, M.H.; Xia, Y.; Qu, F.Q.; Neytsc, J.; Peng, L. Arylethynyltriazole acyclonucleosides inhibit hepatitis C virus replication. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, e3321–e3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Chunxian, L.; Lianjia, Z. Advance of structural modification of 13 nucleosides scaffold. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 214, e1–e22. [Google Scholar]

- Grebenkina, L.E.; Prutkov, A.N.; Matveev, A.V.; Chudinov, M.V. Synthesis of 5-oxymethyl-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamides. Fine Chemical Technologies 2022, 17, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsilevich, T.L.; Shchaveleva, I.L.; Nosach, L.N.; Zhovnovataia, V.L.; Smirnov, I.P. Acyclic analogues of ribavirine. Synthesis and antiviral activity. Bioorg. Chem. 1988, 14, 689–693. [Google Scholar]

- Tsilevich, T.L.; Zavgorodniĭ, S.G.; Marks, U.; Ionova, L.V.; Florentev, V.L. Synthesis of ribavirin acyclic analogues. Bioorg. Chem. 1986, 12, 819–827. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, W.B.; Kleene, R.D. Reaction of Methylal with Some Acid Anhydrides. Service Research and Development Company. 1954, 31, 5159–5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thenet, K.; Beydoun, K.; Wiesenthal, J.; Leitner, W.; Klankermayer, J. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Synthesis of Dialkoxymethane Ethers Utilizing Carbon Dioxide and Molecular Hydrogen. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, H.; Kaneko, C.; Yamada, K.; Takeuchi, T.; Mori, T.; Mizuno, Y. A Convenient Synthesis of 9-(2-Hydroxyethoxymethyl)guanine (Acyclovir) and Related Compounds. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1988, 36, 1153–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenming, L.; Szewczy, J.; Liladhar, W. Practical Synthesis of Diaryloxymethanes. J. Synth. Org. Chem Jpn. 2003, 33, 2719–2723. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Hernandez, E.; Medina-Franco, J.; Trujillo, J.; Chavez-Blanco, A.; Dominguez-Gomez, G.; Perez-Cardenas, E.; Gonzalez-Fierro, A.; Taja-Chayeb, L.; Dueïas-Gonzalez, A. Ribavirin as a tri-targeted antitumor repositioned drug. Oncology Reports. 2015, 33, 2384–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedstrom, L. IMP Dehydrogenase: Structure, Mechanism, and Inhibition. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 2903–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konno, Y.; Natsumeda, Y.; Nagai, M.; Yamaji, Y.; Ohno, S.; Suzuki, K.; Weber, G. Expression of human IMP dehydrogenase types I and II in Escherichia coli and distribution in human normal lymphocytes and leukemic cell lines. J Biol Chem. 1991, 266, 506–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongxia, T.; Li, H.; Zhenshun, C. Inhibition of eIF4E signaling by ribavirin selectively targets lung cancer and angiogenesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 529, 519–525. [Google Scholar]

- Nagai, M.; Natsumeda, Y.; Konno, Y.; Hoffman, R.; Irino, S.; Weber, G. Selective up-regulation of type II inosine 5’-monophosphate dehydrogenase messenger RNA ex-pression in human leukemias. Cancer Res. 1991, 51, 3886–3890. [Google Scholar]

- Urtishak, K.A.; Wang, L.S.; Culjkovic-Kraljacic, B.; Davenport, J.W.; Porazzi, P.; Vincent, T.L.; Teachey, D.T.; Tasian, S.K.; Moore, J.S.; Seif, A.E.; Jin, S.; Barrett, J.S.; Robinson, B.W.; Chen, I.L.; Harvey, R.C.; Carroll, M.P.; Carroll, A.J.; Heerema, N.A.; Devidas, M.; Dreyer, Z.E.; Hilden, J.M.; Hunger, S.P.; Willman, C.L.; Borden, K.L.B.; Felix, C.A. Targeting EIF4E signaling with ribavirin in infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncogene. 2019, 38, 2241–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpin, F.; Casaos, J.; Sesen, J.; Mangraviti, A.; Choi, J.; Gorelick, N.; Frikeche, J.; Lott, T.; Felder, R.; Scotland, S.J.; Eisinger-Mathason, T.S.K.; Brem, H.; Tyler, B.; Skuli, N. Use of an anti-viral drug, Ribavirin, as an anti-glioblastoma therapeutic. Oncogene. 2017, 36, 3037–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraljaci, B.C.; Arguello, M.; Amri, A.; Cormack, G.; Borden, K. Inhibition of eIF4E with ribavirin cooperates with common chemotherapies in primary acute myeloid leukemia specimens. Leukemia. 2011, 25, 1197–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kentsis, A.; Volpon, L.; Topisirovic, I.; Soll, C.E.; Culjkovic, B.; Shao, L.; Borden, K.L. Further evidence that ribavirin interacts with eIF4E. RNA. 2005, 11, 1762–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvera, D.; Formenti, S.C.; Schneider, R.J. Translational control in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2010, 10, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, E.; Jenni, S.; Kabha, E.; Wagner, G. Structure of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4E in complex with 4EGI-1 reveals an allosteric mechanism for dissociating eIF4G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014, 111, E3187–E3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, S.; Li, Y.; Yue, P.; Khuri, F.R.; Sun, S.Y. The eIF4E/eIF4G interaction inhibitor 4EGI-1 augments TRAIL-mediated apoptosis through c-FLIP Down-regulation and DR5 induction independent of inhibition of cap-dependent protein translation. Neoplasia. 2010, 12, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moerke, N.J.; Aktas, H.; Chen, H.; Cantel, S.; Reibarkh, M.Y.; Fahmy, A.; Gross, J.D.; Degterev, A.; Yuan, J.; Chorev, M.; Halperin, J.A.; Wagner, G. Small-molecule inhibition of the interaction between the translation initiation factors eIF4E and eIF4G. Cell. 2007, 128, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Aktas, B.H.; Wang, Y.; He, X.; Sahoo, R.; Zhang, N.; Denoyelle, S.; Kabha, E.; Yang, H.; Freedman, R.Y.; Supko, J.G.; Chorev, M.; Wagner, G.; Halperin, J.A. Tumor suppression by small molecule inhibitors of translation initiation. Oncotarget. 2012, 3, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamburini, J.; Green, A.S.; Bardet, V.; Chapuis, N.; Park, S.; Willems, L.; Uzunov, M.; Ifrah, N.; Dreyfus, F.; Lacombe, C.; Mayeux, P.; Bouscary, D. Protein synthesis is resistant to rapamycin and constitutes a promising therapeutic target in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2009, 114, 1618–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Descamps, G.; Gomez-Bougie, P.; Tamburini, J.; Green, A.; Bouscary, D.; Maiga, S.; Moreau, P.; Gouill, S.L.; Pellat-Deceunynck, C.; Amiot, M. The cap-translation inhibitor 4EGI-1 induces apoptosis in multiple myeloma through Noxa induction. Br. J. Cancer. 2012, 106, 1660–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

||

| S. No. | R | Yield |

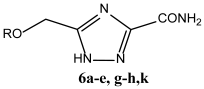

| 6a | Me | 60% |

| 6b | Et | 53% |

| 6c | n-Pr | 62% |

| 6d | i-Pr | 24% |

| 6e | n-Bu | 33% |

| 6g | n-C10H21 | 43% |

| 6h | Bn | 68% |

| 6k | Ph | 76% |

| 5-oxymethyl-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamides | 1-oxymethyl-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamides | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC50, µM | CC50, µM | ||||||||

| S. No. | K562 | CCRF-SB | S. No. | K562 | CCRF-SB | ||||

| 24h | 72h | 24h | 72h | 24h | 72h | 24h | 72h | ||

| 1a(ribavirin) | 270±11 | 10±1 | - | 188±31 | |||||

| 2g | 260±12* | 240±16* | 1g | 240±22* | 230±18* | ||||

| 2h | 240±21* | 250±13* | 1h | 230±13* | 270±25* | ||||

| 6a | - | - | - | - | 11a | - | - | - | - |

| 6b | - | - | - | - | 11b | - | - | - | - |

| 6c | - | - | - | - | 11c | - | - | - | - |

| 6d | - | - | - | - | 11d | - | - | - | - |

| 6e | - | - | - | - | 11e | - | - | - | - |

| 11f | - | - | - | - | |||||

| 6g | 391±15 | 43±7 | 500±100 | - | 11g | 14±0 | 13±3 | 112±19 | 62±2 |

| 6h | - | - | - | - | 11h | - | - | - | - |

| 11i | - | - | - | - | |||||

| 11j | - | - | - | - | |||||

| 6k | - | - | - | - | 11k | - | - | - | - |

| 1c | - | - | - | - | |||||

| Сyt | 59.4±14.0 | 58.1±16.9 | 15.8±4.1 | 0.1±0.1 | |||||

| S. No. | Zone of growth inhibition, mm | |||

| S. aureus | M. luteus | P. aeruginosa | C. albicans | |

| 1-oxymethyl-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamides | ||||

| 1a | - | - | 25±1 | 30±1 |

| 11a | - | - | - | - |

| 11b | - | - | - | - |

| 11c | - | - | 12±1 | - |

| 11d | - | - | - | - |

| 11e | - | - | - | - |

| 11f | - | - | - | - |

| 11g | - | - | - | - |

| 11h | - | - | - | - |

| 11i | - | 12±1 | - | - |

| 11j | - | 12±1 | - | - |

| 11k | - | - | - | - |

| 1c | - | 12±1 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).