Submitted:

23 September 2024

Posted:

23 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

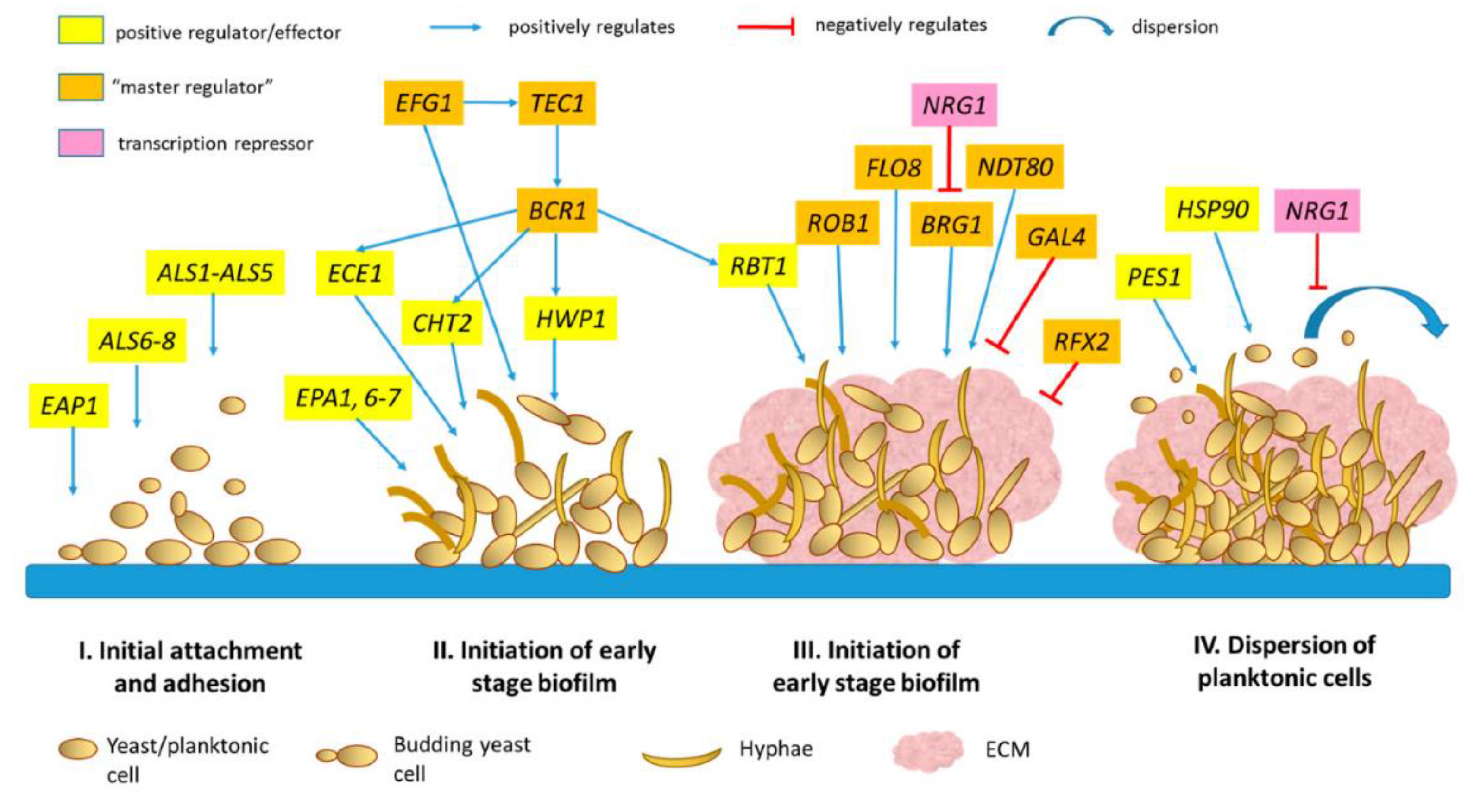

2. Mechanisms of Biofilm Formation in Unicellular Eukaryotes

2.1. Stages of Biofilm Development

2.2. Key Regulatory Pathways

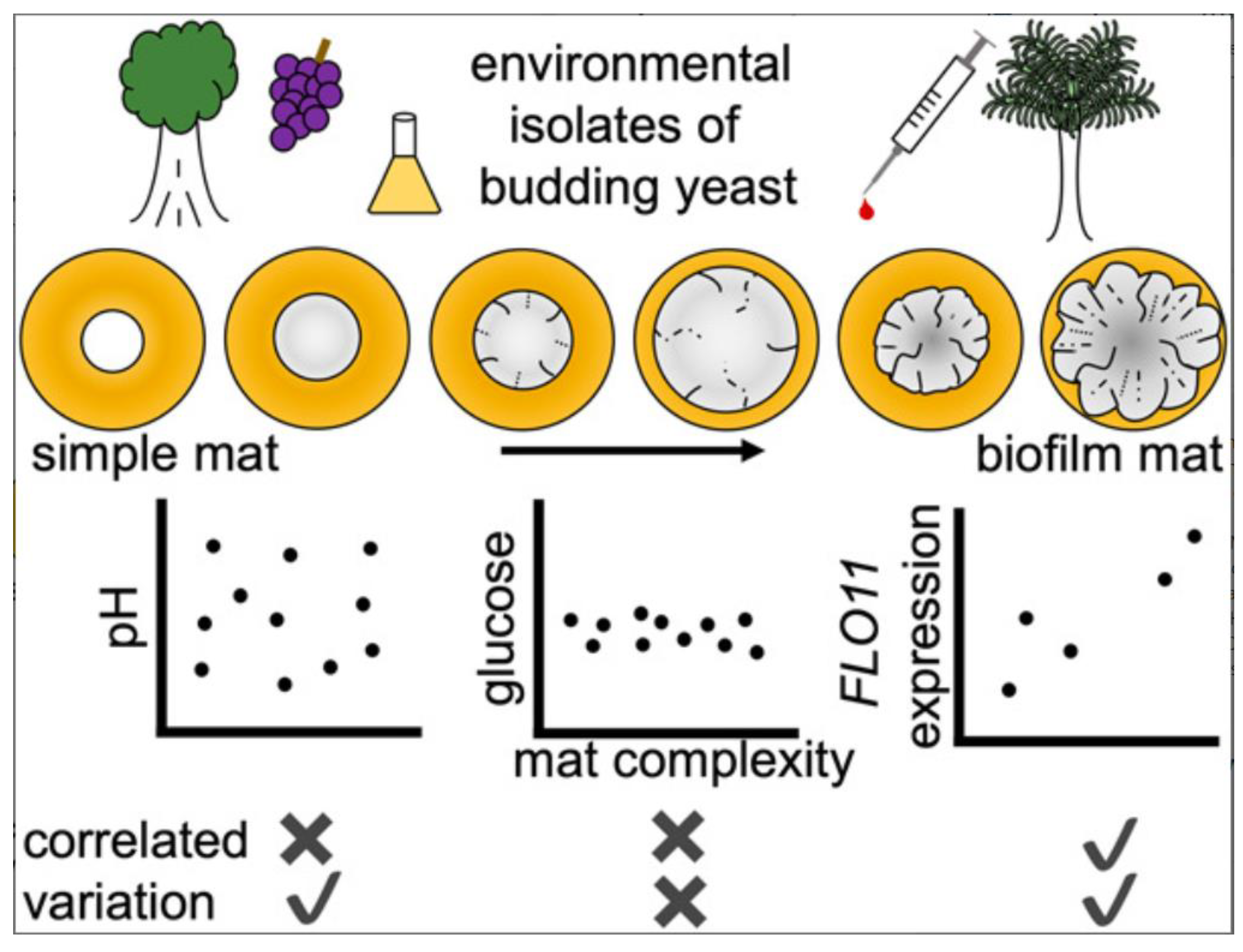

2.3. Species-Specific Mechanisms

3. Advances in Compounds Targeting Biofilm Regulatory Mechanisms (2024)

3.1. Inhibition of Quorum Sensing

3.2. Disrupting Extracellular Matrix Synthesis

3.3. Targeting Transcriptional and Post-Transcriptional Regulation

3.4. Synergistic Compounds

4. Applications and Challenges in Vietnam

5. Future Directions

5.1. Emerging Compounds and Technologies

5.2. Towards Personalized Treatments

5.3. Opportunities for Vietnam-Based Research

6. Discussion

7. Conclusion

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hall-Stoodley, L., J.W. Costerton, and P. Stoodley, Bacterial biofilms: from the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nature reviews microbiology, 2004. 2(2): p. 95-108.

- Wang, X., et al., Biofilm formation: mechanistic insights and therapeutic targets. Molecular Biomedicine, 2023. 4(1): p. 49.

- Palková, Z. and L. Váchová, Life within a community: benefit to yeast long-term survival. FEMS microbiology reviews, 2006. 30(5): p. 806-824.

- O'Toole, G., H.B. Kaplan, and R. Kolter, Biofilm formation as microbial development. Annual Reviews in Microbiology, 2000. 54(1): p. 49-79.

- Jiang, Y., M. Geng, and L. Bai, Targeting biofilms therapy: current research strategies and development hurdles. Microorganisms, 2020. 8(8): p. 1222.

- Carradori, S., et al., Biofilm and quorum sensing inhibitors: The road so far. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents, 2020. 30(12): p. 917-930.

- Trebino, M.A., et al., Strategies and approaches for discovery of small molecule disruptors of biofilm physiology. Molecules, 2021. 26(15): p. 4582.

- Nguyen, H.T.T., G.N.T. Nguyen, and A.V. Nguyen, Hospital-acquired infections in ageing Vietnamese population: current situation and solution. MedPharmRes, 2020. 4(2): p. 1-10.

- Alvarez-Ordóñez, A., et al., Biofilms in food processing environments: challenges and opportunities. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology, 2019. 10(1): p. 173-195.

- Wingender, J. and H.-C. Flemming, Biofilms in drinking water and their role as reservoir for pathogens. International journal of hygiene and environmental health, 2011. 214(6): p. 417-423.

- Velmourougane, K., R. Prasanna, and A.K. Saxena, Agriculturally important microbial biofilms: present status and future prospects. Journal of basic microbiology, 2017. 57(7): p. 548-573.

- Ho, C.S., et al., Antimicrobial resistance: a concise update. The Lancet Microbe, 2024.

- Kumar, D. and A. Kumar, Molecular determinants involved in Candida albicans biofilm formation and regulation. Molecular Biotechnology, 2024. 66(7): p. 1640-1659.

- Čáp, M., et al., Cell differentiation within a yeast colony: metabolic and regulatory parallels with a tumor-affected organism. Molecular cell, 2012. 46(4): p. 436-448.

- Su, C., J. Yu, and Y. Lu, Hyphal development in Candida albicans from different cell states. Current genetics, 2018. 64: p. 1239-1243.

- Uppuluri, P., et al., Dispersion as an important step in the Candida albicans biofilm developmental cycle. PLoS pathogens, 2010. 6(3): p. e1000828.

- Kovács, R. and L. Majoros, Fungal quorum-sensing molecules: a review of their antifungal effect against Candida biofilms. Journal of Fungi, 2020. 6(3): p. 99.

- Hollomon, J.M., et al., Global role of cyclic AMP signaling in pH-dependent responses in Candida albicans. Msphere, 2016. 1(6): p. 10.1128/msphere. 00283-16.

- Finkel, J.S. and A.P. Mitchell, Genetic control of Candida albicans biofilm development. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2011. 9(2): p. 109-118.

- Čáp, M. and Z. Palková, Non-Coding RNAs: Regulators of Stress, Ageing, and Developmental Decisions in Yeast? Cells, 2024. 13(7): p. 599.

- Wang, D., et al., Fungal biofilm formation and its regulatory mechanism. Heliyon, 2024. 10(12).

- Nobile, C.J., et al., A recently evolved transcriptional network controls biofilm development in Candida albicans. Cell, 2012. 148(1): p. 126-138.

- Finkel, J.S., et al., Portrait of Candida albicans adherence regulators. PLoS pathogens, 2012. 8(2): p. e1002525.

- Glazier, V.E., et al., Genetic analysis of the Candida albicans biofilm transcription factor network using simple and complex haploinsufficiency. PLoS genetics, 2017. 13(8): p. e1006948.

- Andersen, K.S., et al., Genetic basis for Saccharomyces cerevisiae biofilm in liquid medium. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics, 2014. 4(9): p. 1671-1680.

- Forehand, A.L., et al., Variation in pH gradients and FLO11 expression in mat biofilms from environmental isolates of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. MicrobiologyOpen, 2022. 11(2): p. e1277.

- Meylani, V., et al., Computational Prediction of Cinnamomum zeylanicum Bioactive Compounds as Potential Antifungal by Inhibit Biofilm Formation of Candida albicans. Trends in Sciences, 2024. 21(8): p. 7986-7986.

- Erdal, B., et al., Investigation of the Effect of Farnesol on Biofilm Formation by Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis Complex Isolates. Mikrobiyoloji bulteni, 2024. 58(1): p. 49-62.

- Lee, J.-H., et al., Antifungal and antibiofilm activities of chromones against nine Candida species. Microbiology Spectrum, 2023. 11(6): p. e01737-23.

- Iloputaife Emmanuel Jaluchimike, A.J., Ewoh Anthonia Ngozi, Antimicrobial and Phytochemical Activities of Garlic (Allium sativum) on Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans Isolated from High Vaginal Swab samples and Female Students with UTI. Scholars Journal of Medical Case Reports, 2023 Sep. 11(9): p. 6.

- Abd Kadhum, A., Virulence Factors and the Effect of Garlic Extract against Proteus mirabilis Isolated from Patients with UTI at Thi-Qar Province. Haya Saudi J Life Sci, 2024. 9(7): p. 258-262.

- Indira, M., et al., Antibacterial Activity of the Allium sativum Crude Extract against Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Pure & Applied Microbiology, 2024. 18(2).

- do Nascimento Dias, J., et al., Synergic Effect of the Antimicrobial Peptide ToAP2 and Fluconazole on Candida albicans Biofilms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2024. 25(14): p. 7769.

- Zou, P., et al., Antifungal Activity, Synergism with Fluconazole or Amphotericin B and Potential Mechanism of Direct Current against Candida albicans Biofilms and Persisters. Antibiotics, 2024. 13(6): p. 521.

- Massey, J., R. Zarnowski, and D. Andes, Role of the extracellular matrix in Candida biofilm antifungal resistance. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 2023. 47(6): p. fuad059.

- Khadam, A.A. and J.A. Salman, Antibacterial and Antibiofilm of Purified β-glucan from Saccharomyces cerevisiae against Wound Infections Causative Bacteria. Iraqi Journal of Science, 2024: p. 2397-2409.

- David, H., S. Vasudevan, and A.P. Solomon, Mitigating candidiasis with acarbose by targeting Candida albicans α-glucosidase: in-silico, in-vitro and transcriptomic approaches. Scientific Reports, 2024. 14(1): p. 11890.

- Clavijo-Giraldo, D.M., et al., Contribution of N-Linked Mannosylation Pathway to Candida parapsilosis and Candida tropicalis Biofilm Formation. Infection and Drug Resistance, 2023: p. 6843-6857.

- Razmi, M., et al., Candida albicans Mannosidases, Dfg5 and Dcw1, Are Required for Cell Wall Integrity and Pathogenesis. Journal of Fungi, 2024. 10(8): p. 525.

- Tian, D., et al., Anti-biofilm mechanism of a synthetical low molecular weight poly-d-mannose on Salmonella Typhimurium. Microbial Pathogenesis, 2024. 187: p. 106515.

- Karyani, T.Z., S. Ghattavi, and A. Homaei, Application of enzymes for targeted removal of biofilm and fouling from fouling-release surfaces in marine environments: A review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2023: p. 127269.

- Kumar, D. and A. Kumar, Deciphering druggability potential of some proteins of Candida albicans biofilm using subtractive proteomics approach. Rendiconti Lincei. Scienze Fisiche e Naturali, 2024. 35(1): p. 273-292.

- Upadhyay, A., D. Pal, and A. Kumar, Combinatorial enzyme therapy: A promising neoteric approach for bacterial biofilm disruption. Process Biochemistry, 2023. 129: p. 56-66.

- Rahman, M.A., et al., Comparison of the proteome of Staphylococcus aureus planktonic culture and 3-day biofilm reveals potential role of key proteins in biofilm. Hygiene, 2024. 4(3): p. 238-257.

- Pan, S., et al., A putative lipase affects Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix production. Msphere, 2023. 8(5): p. e00374-23.

- Montoya, C., et al., Cyclic strain of Poly (methyl methacrylate) surfaces triggered the pathogenicity of Candida albicans. Acta Biomaterialia, 2023. 170: p. 415-426.

- Le, P.H., et al., Impact of multiscale surface topography characteristics on Candida albicans biofilm formation: from cell repellence to fungicidal activity. Acta Biomaterialia, 2024.

- Kaur, J. and C.J. Nobile, Antifungal drug-resistance mechanisms in Candida biofilms. Current opinion in microbiology, 2023. 71: p. 102237.

- Widanage, M.C.D., et al., Structural Remodeling of Fungal Cell Wall Promotes Resistance to Echinocandins. bioRxiv, 2023: p. 2023.08. 09.552708.

- Kosmeri, C., et al., Antibiofilm Strategies in Neonatal and Pediatric Infections. Antibiotics, 2024. 13(6): p. 509.

- Banerjee, A., et al., Inhibition and eradication of bacterial biofilm using polymeric materials. Biomaterials Science, 2023. 11(1): p. 11-36.

- Zainab, S., et al., Fluconazole and biogenic silver nanoparticles-based nano-fungicidal system for highly efficient elimination of multi-drug resistant Candida biofilms. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 2022. 276: p. 125451.

- Araújo, D., et al., Combined application of antisense oligomers to control transcription factors of Candida albicans biofilm formation. Mycopathologia, 2023. 188(3): p. 231-241.

- Lohse, M.B., N. Ziv, and A.D. Johnson, Variation in transcription regulator expression underlies differences in white–opaque switching between the SC5314 reference strain and the majority of Candida albicans clinical isolates. Genetics, 2023. 225(3): p. iyad162.

- Zhang, Y., et al., DNA Damage Checkpoints Govern Global Gene Transcription and Exhibit Species-Specific Regulation on HOF1 in Candida albicans. Journal of Fungi, 2024. 10(6): p. 387.

- Qin, L., et al., An effective strategy for identifying autogenous regulation of transcription factors in filamentous fungi. Microbiology Spectrum, 2023. 11(6): p. e02347-23.

- Hall, R.A. and E.W. Wallace, Post-transcriptional control of fungal cell wall synthesis. The Cell Surface, 2022. 8: p. 100074.

- Reynaud, K., et al., Surveying the global landscape of post-transcriptional regulators. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 2023. 30(6): p. 740-752.

- Pastora, A.B. and G.A. O’Toole, The regulator FleQ both transcriptionally and post-transcriptionally regulates the level of RTX adhesins of Pseudomonas fluorescens. Journal of Bacteriology, 2023. 205(9): p. e00152-23.

- Martínez, A., et al., Effect of essential oil from Lippia origanoides on the transcriptional expression of genes related to quorum sensing, biofilm formation, and virulence of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics, 2023. 12(5): p. 845.

- Chakravarty, D., et al., Targeting microbial biofilms using genomics-guided drug discovery, in Microbial Biofilms: Challenges and Advances in Metabolomic Study. 2023, Elsevier. p. 315-324.

- Thomann, A., et al., Application of dual inhibition concept within looped autoregulatory systems toward antivirulence agents against Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. ACS chemical biology, 2016. 11(5): p. 1279-1286.

- Liu, C., et al., Small Molecule Attenuates Bacterial Virulence by Targeting Conserved Response Regulator. Mbio, 2023. 14(3): p. e00137-23.

- Mejía-Manzano, L.A., et al., Advances in Material Modification with Smart Functional Polymers for Combating Biofilms in Biomedical Applications. Polymers, 2023. 15(14): p. 3021.

- Qu, Y., et al., Disruption of Communication: Recent Advances in Antibiofilm Materials with Anti-Quorum Sensing Properties. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2024. 16(11): p. 13353-13383.

- Verma, N., et al., Inhibition and disintegration of Bacillus subtilis biofilm with small molecule inhibitors identified through virtual screening for targeting TasA (28-261), the major protein component of ECM. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics, 2023. 41(6): p. 2431-2447.

- Lobo, C.I.V., A.C.U.d.A. Lopes, and M.I. Klein, Compounds with distinct targets present diverse antimicrobial and antibiofilm efficacy against Candida albicans and Streptococcus mutans, and combinations of compounds potentiate their effect. Journal of Fungi, 2021. 7(5): p. 340.

- Goller, C., et al., The cation-responsive protein NhaR of Escherichia coli activates pgaABCD transcription, required for production of the biofilm adhesin poly-β-1, 6-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine. Journal of bacteriology, 2006. 188(23): p. 8022-8032.

- Morris, A.R., C.L. Darnell, and K.L. Visick, Inactivation of a novel response regulator is necessary for biofilm formation and host colonization by Vibrio fischeri. Molecular microbiology, 2011. 82(1): p. 114-130.

- Xiao, Y., et al., Identification of c-di-GMP/FleQ-regulated new target genes, including cyaA, encoding adenylate cyclase, in Pseudomonas putida. Msystems, 2021. 6(3): p. 10.1128/msystems. 00295-21.

- Nguyen, X.C., et al., Antifouling 26, 27-cyclosterols from the Vietnamese marine sponge Xestospongia testudinaria. Journal of natural products, 2013. 76(7): p. 1313-1318.

- Buommino, E., et al., Recent advances in natural product-based anti-biofilm approaches to control infections. Mini reviews in medicinal chemistry, 2014. 14(14): p. 1169-1182.

- Kour, D., et al., Microbial biofilms: functional annotation and potential applications in agriculture and allied sectors, in New and future developments in microbial biotechnology and bioengineering: microbial biofilms. 2020, Elsevier. p. 283-301.

- Hemmati, F., et al., Novel strategies to combat bacterial biofilms. Molecular biotechnology, 2021. 63(7): p. 569-586.

- Pal, S., A. Qureshi, and H.J. Purohit, Antibiofilm activity of biomolecules: gene expression study of bacterial isolates from brackish and fresh water biofouled membranes. Biologia, 2016. 71(3): p. 239-246.

- CCR de Carvalho, C., Biofilms: new ideas for an old problem. Recent Patents on Biotechnology, 2012. 6(1): p. 13-22.

- Speziale, P. and J.A. Geoghegan, Biofilm formation by staphylococci and streptococci: structural, functional, and regulatory aspects and implications for pathogenesis. 2015, Frontiers Media SA. p. 31.

- Malott, R.J. and P.A. Sokol, Expression of the bviIR and cepIR quorum-sensing systems of Burkholderia vietnamiensis. Journal of bacteriology, 2007. 189(8): p. 3006-3016.

- Karunakaran, E., et al., “Biofilmology”: a multidisciplinary review of the study of microbial biofilms. Applied microbiology and biotechnology, 2011. 90: p. 1869-1881.

- Tada, T., et al., Emergence of 16S rRNA methylase-producing Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates in hospitals in Vietnam. BMC infectious diseases, 2013. 13: p. 1-6.

- Parry, C.M., et al., Emergence in Vietnam of Streptococcus pneumoniae resistant to multiple antimicrobial agents as a result of dissemination of the multiresistant Spain23F-1 clone. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2002. 46(11): p. 3512-3517.

- Krukiewicz, K., et al., Recent advances in the control of clinically important biofilms. International journal of molecular sciences, 2022. 23(17): p. 9526.

- Ohno, K., Comment on “Challenges in Searching for Vietnam's Growth Drivers Through 2030”. Asian Economic Policy Review, 2024.

- Herrador, M., et al., The unique case study of circular economy in Vietnam remarking recycling craft villages. SAGE Open, 2023. 13(3): p. 21582440231199939.

- Jakobsen, T.H., T. Tolker-Nielsen, and M. Givskov, Bacterial biofilm control by perturbation of bacterial signaling processes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2017. 18(9): p. 1970.

- Samrot, A.V., et al., Mechanisms and impact of biofilms and targeting of biofilms using bioactive compounds—A review. Medicina, 2021. 57(8): p. 839.

- Jagadeesh, N. and M. Karabasappa, Control of microbial biofilms: application of natural and synthetic compounds, in New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering: Microbial Biofilms. 2020, Elsevier. p. 101-115.

| QSI Compound | Target Organism | Mechanism of Action | Biofilm Reduction (%) | Study Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Furanones | Candida albicans | Inhibition of farnesol production, disrupting QS | 65% biofilm biomass reduction | [27] |

| Garlic Extract (Allicin) | Candida albicans | Downregulates biofilm genes (FLO11, EFG1) | 50% biofilm biomass reduction | [30] |

| Peptide-based QSIs | Candida spp., Saccharomyces spp. | Blocks signal receptors, prevents biofilm maturation | Not quantified | [33] |

| Synergistic QSI + Fluconazole | Candida albicans | Combined inhibition of quorum sensing and antifungal action | 75% biofilm viability reduction | [33] |

| QSI Compound | Target Organism | Mechanism of Action | Biofilm Reduction (%) | Additional Effects | Study References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Glucanase Enzymes | Candida albicans | Degrades β-glucans in the biofilm matrix, reducing structural integrity | 60% reduction in biomass | Increased susceptibility to fluconazole | [37] |

| Mannosidase Inhibitors | Candida glabrata | Inhibits mannan synthesis, reducing biofilm stability | 50% reduction in biomass | Enhanced susceptibility to echinocandins | [39] |

| Proteolytic Enzymes | Candida glabrata | Disrupts protein-mediated cell adhesion, impairing biofilm cohesion | 40% reduction in adhesion | Prevented biofilm maturation | [44] |

| β-Glucanase + Fluconazole | Candida albicans | Combination therapy degrading β-glucans and enhancing antifungal action | 75% enhanced efficacy | Significant biofilm viability reduction | [52] |

| Mannosidase + Echinocandins | Candida glabrata | Inhibits matrix mannans and enhances echinocandin antifungal effects | 50% increased susceptibility | Improved drug penetration into biofilm layers | [48] |

| Mechanism/ Strategy | Target Organism | Key Regulators/ Compounds | Effects on Biofilm Formation | Biofilm Reduction (%) or Quantitative Data | Study References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factor Inhibition (ASOs) | Candida albicans | EFG1, BRG1, ROB1 (Antisense oligomers) | Reduces gene expression of key biofilm genes, decreases biofilm matrix and thickness | 40–60% reduction in biofilm thickness and matrix content | [53] |

| White-Opaque Switching | Candida albicans | Mating-type regulators (strain SC5314) | Affects biofilm development, strain-specific variation in white-opaque switching | Reduced biofilm formation in clinical strains; variation across strains | [54] |

| DNA Damage Checkpoints | Candida albicans | Rad53 kinase, Mcm1, HOF1 | Regulates biofilm-associated genes through DNA damage response pathways | Reduced biofilm stability linked to impaired DNA damage response | [55] |

| Autogenous Regulation of Transcription | Candida albicans, other fungi | Transcription factors regulating own expression | Disrupting autogenous regulation weakens transcription of biofilm-related genes | Data on specific biofilm reduction not yet available | [56] |

| RNA-Binding Proteins | Candida albicans | Ssd1, Slr1 | Regulates cell wall component translation, affecting biofilm stability | 30–50% reduction in biofilm stability via mRNA regulation | [57] |

| Post-Transcriptional Regulatory Networks | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Modular mRNA-targeting regulatory proteins | Modulates mRNA fate, affecting biofilm gene expression | 45% reduction in biofilm-associated gene expression | [58] |

| FleQ Regulation | Pseudomonas fluorescens | FleQ regulator (Adhesin modulation) | Controls adhesin production and post-transcriptional adhesin abundance | Significant reduction in biofilm adhesion and stability in bacteria | [59] |

| Antisense Oligomers (ASOs) | Candida albicans | ASOs targeting transcription factors | Reduces biofilm-related gene expression, inhibits biofilm formation | 50% reduction in biofilm formation | [53] |

| Natural Compounds (Essential Oils) | Various bacterial species | Lippia origanoides (Essential oils) | Disrupts quorum sensing and biofilm formation | 55–70% reduction in biofilm biomass in bacterial species | [60] |

| Targeting α-Glucosidase | Candida albicans | Acarbose (α-glucosidase inhibitor) | Inhibits α-glucosidase, reducing adhesion and biofilm formation | 60% reduction in biofilm formation | [37] |

| Genomics-Guided Drug Discovery | Candida albicans | Novel drug targets identified through omics | Potential for targeted disruption of biofilm regulatory mechanisms | Early-stage research; data on biofilm reduction pending | [61] |

| Focus Area | Mechanisms/ Compounds | Effectiveness | Potential Applications in Vietnam | Challenges | Study Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Mechanisms of Biofilm Formation | NhaR Protein in Escherichia coli | Activates biofilm gene expression under NaCl and alkaline pH conditions, regulating the pgaABCD operon | Potential for biocontrol in saline and alkaline environments | Requires further testing in environmental conditions in Vietnam | [68] |

| Two-Component Systems in Biofilms | RscS-SypG System in Vibrio fischeri | Regulates biofilm formation and host colonization via SypE | Applications in aquaculture and water management in Vietnam | Complexity of host-pathogen interactions in different ecosystems | [69] |

| Cyclic Di-GMP Pathways | FleQ Regulation in Pseudomonas putida | Regulates biofilm genes, influencing the shift from planktonic to biofilm states | Could be applied in industrial biofilm control in Vietnam's water systems | Environmental persistence of biofilm-forming organisms | [70] |

| Marine-Derived Antibiofilm Compounds | Aragusterol B from Xestospongia testudinaria | Inhibits bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation by 50–70% | Marine-based biofilm control in aquaculture and antifouling agents | Scalability and sustainable sourcing of marine compounds | [71] |

| Plant-Based Antibiofilm Compounds | Halogenated Furanones and Flavonoids | Effective biofilm inhibitors, disrupting quorum sensing | Potential therapeutic applications in Vietnam’s agricultural and healthcare sectors | Limited studies on specific fungal biofilms in Vietnam | [72] |

| Agricultural Biofilms for Bioinoculants | Biofilm-based bioinoculants | Enhances soil fertility and plant growth by 20–40% | Increased crop productivity in Vietnamese agriculture | Adaptation to local soil and crop conditions | [73] |

| Healthcare Applications | Quorum Sensing Inhibitors (QSIs) | Reduces chronic infections and industrial biofouling by up to 60% | Improved patient outcomes in hospitals and biofouling reduction in industries | Challenges in resistance development and broad-spectrum activity | [74] |

| Industrial Biofouling Challenges | Natural antifouling compounds | Prevents biofilm development on surfaces, reducing maintenance costs by up to 50% | Industrial applications in marine and freshwater systems | Ensuring environmental safety and long-term efficacy | [75] |

| Broader Perspectives | Omics-guided discovery of novel biofilm targets | Identification of new drug targets for biofilm disruption | Future potential in pharmaceutical and industrial applications in Vietnam | High cost and complexity of omics-based interventions | [61] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).