Submitted:

17 September 2024

Posted:

18 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

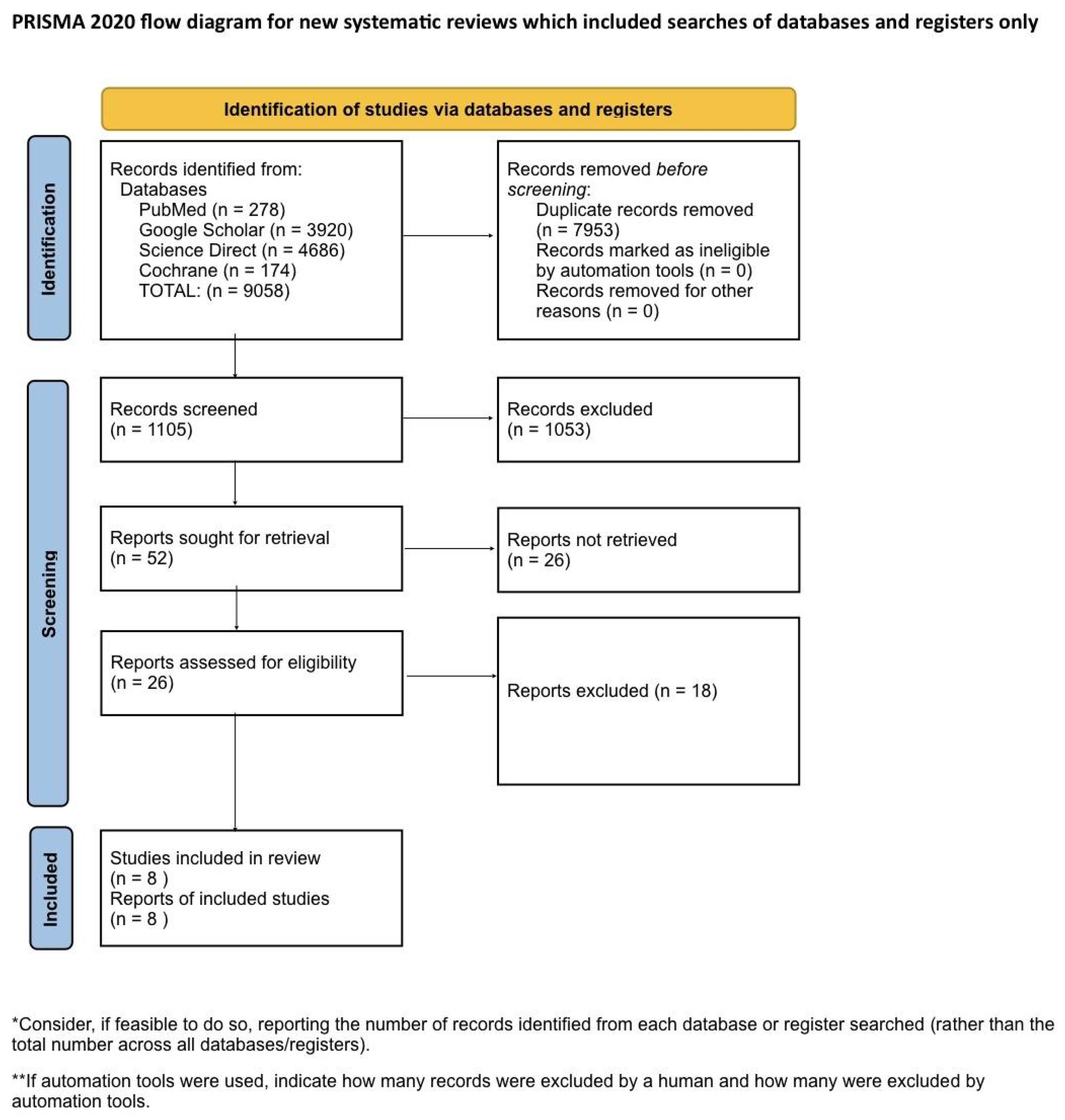

Systematic Literature Search and Study Selection

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Population: adult patients diagnosed with TS.

- Intervention: treatment with CBM.

- Comparison: placebo or no intervention.

- Outcome: tic severity, premonitory urges symptoms were measured by the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) and Premonitory Urge for Tics Scale (PUTS).

Search Strategy

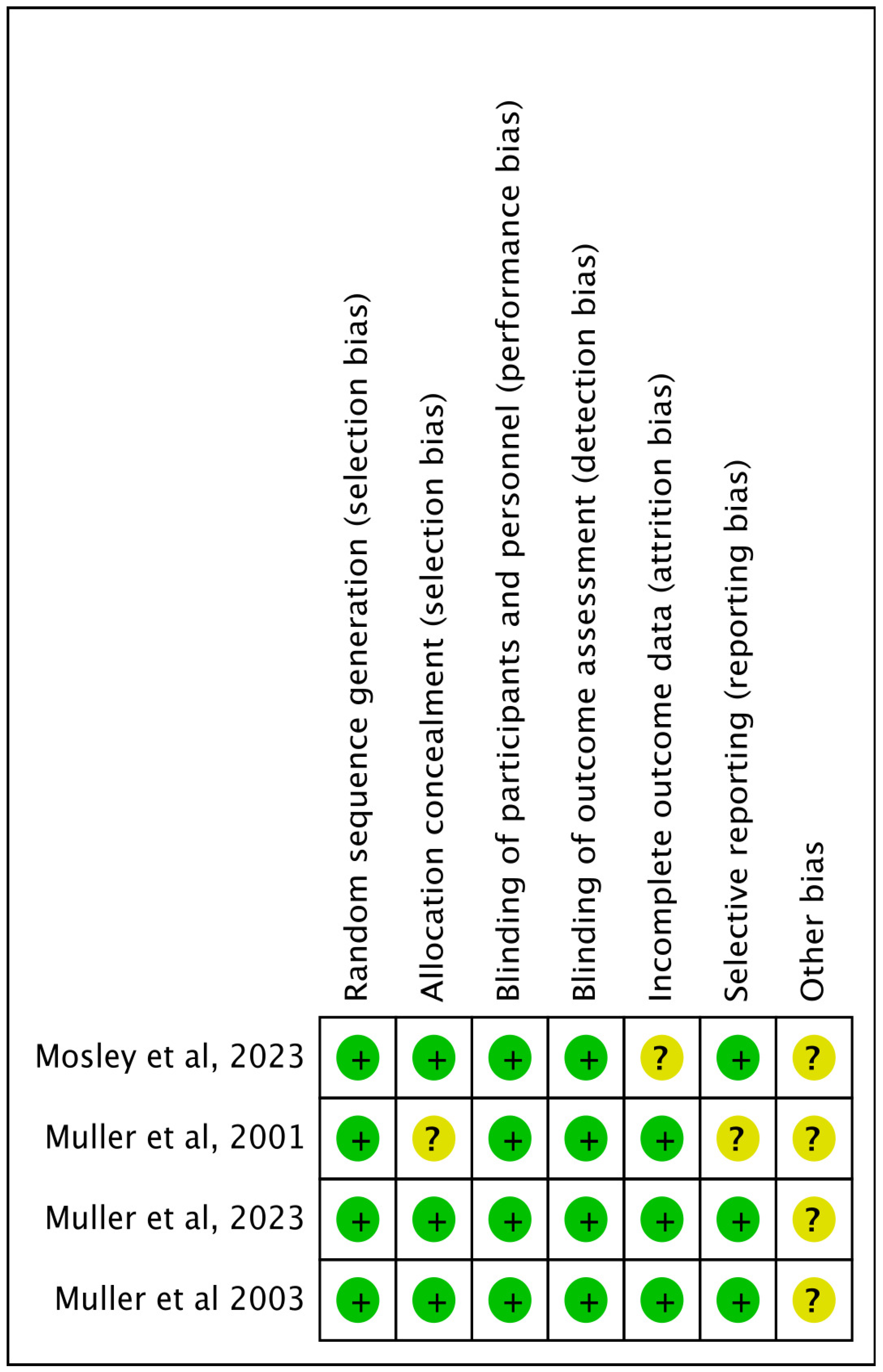

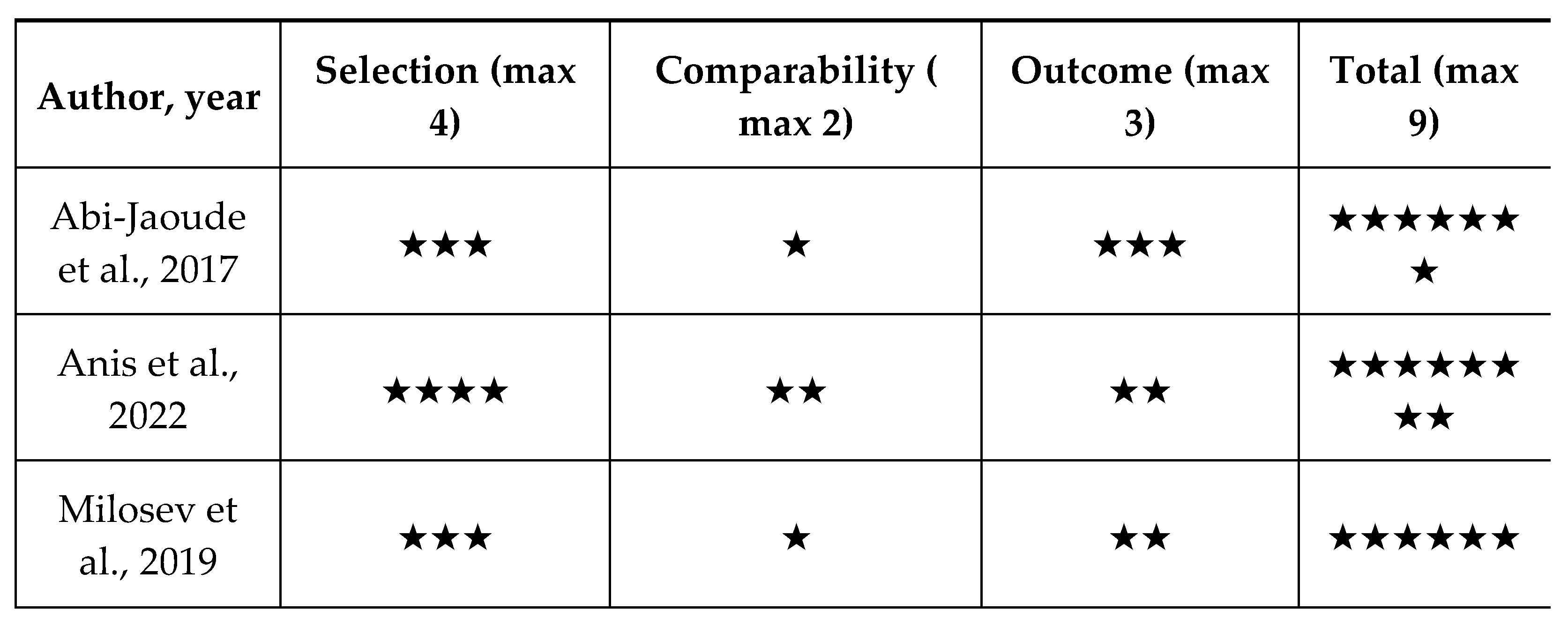

Quality Appraisal

Data Extraction and Outcome Measures

Meta-Analysis

Results

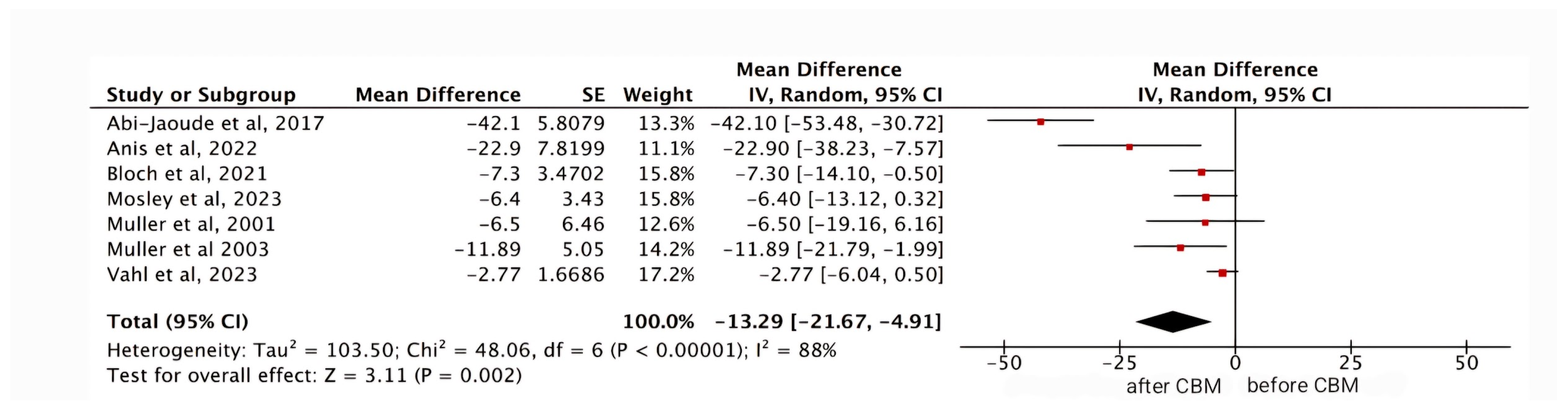

YGTSS

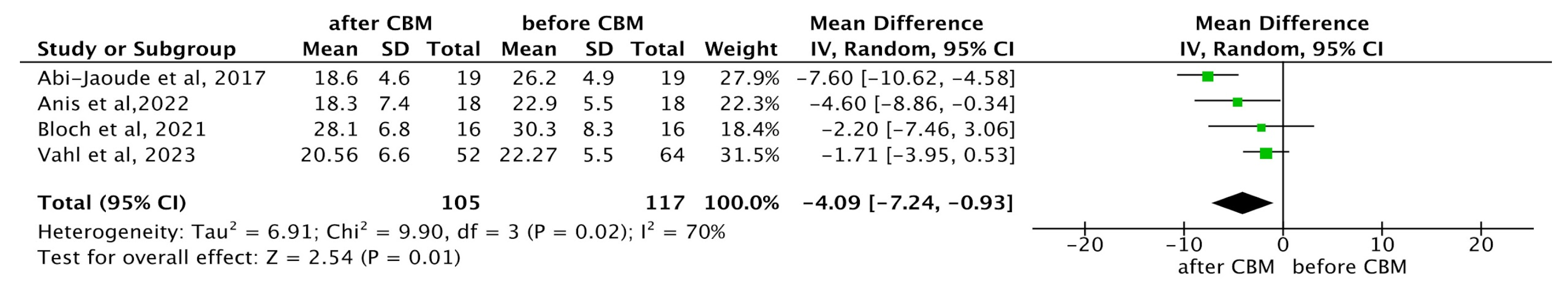

PUTS

Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Ethical Approval

Competing interests

References

- Milosev LM, Psathakis N, Szejko N, et al. Treatment of Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome with Cannabis-Based Medicine: Results from a Retrospective Analysis and Online Survey. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2019;4(4):265–74. [CrossRef]

- Müller-Vahl KR, Pisarenko A, Szejko N, et al. CANNA-TICS: Efficacy and safety of oral treatment with nabiximols in adults with chronic tic disorders – Results of a prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, phase IIIb superiority study. Psychiatry Res. 2023;323:115135. [CrossRef]

- Jafari F, Abbasi P, Rahmati M, Hodhodi T, Kazeminia M. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Tourette Syndrome Prevalence; 1986 to 2022. Pediatr Neurol. 2022 Dec;137:6–16. [CrossRef]

- Levine JLS, Szejko N, Bloch MH. Meta-analysis: Adulthood prevalence of Tourette syndrome. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019 Dec;95:109675. [CrossRef]

- Lin WD, Tsai FJ, Chou IC. Current understanding of the genetics of Tourette syndrome. Biomed J. 2022;45(2):271–9. [CrossRef]

- Woods DW, Watson TS, Wolfe E, et al. Analyzing the influence of tic-related talk on vocal and motor tics in children with Tourette’s syndrome. J Appl Behav Anal. 2001;34(3):353–6. [CrossRef]

- Olive MF. Tourette syndrome. Infobase Publishing; 2010. Available from: https://www.google.lk/books/edition/Tourette_Syndrome/OkRnYQ_MECAC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=symptoms+of+tourette+syndrome+article&printsec=frontcover.

- Worbe Y, Marrakchi-Kacem L, Lecomte S, Valabregue R, Poupon F, Guevara P, et al. Altered structural connectivity of cortico-striato-pallido-thalamic networks in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Brain. 2015;138(2):472–82. [CrossRef]

- Thenganatt MA, Jankovic J. Recent Advances in Understanding and Managing Tourette Syndrome. F1000Res. 2016;5:152. [CrossRef]

- Rae CL, Critchley HD. Mechanistic insight into the pathophysiological basis of Tourette syndrome. In: International Review of Movement Disorders. Elsevier; 2022. p. 209–44.

- Singer HS, Augustine F. Controversies Surrounding the Pathophysiology of Tics. J Child Neurol. 2019;34(13):851–62. [CrossRef]

- Leckman JF, Bloch MH, Smith ME, Larabi D, Hampson M. Neurobiological substrates of Tourette’s disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(4):237–47. [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke JA, Scharf JM, Yu D, Pauls DL. The genetics of Tourette syndrome: A review. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67(6):533–45. [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra PJ, Kallenberg CGM, Korf J, Minderaa RB. Is Tourette’s syndrome an autoimmune disease? Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7(5):437–45.

- Lamothe H, Tamouza R, Hartmann A, Mallet L. Immunity and Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence for immune implications in Tourette syndrome. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28(9):3187–200. [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra PJ, Dietrich A, Edwards MJ, Elamin I, Martino D. Environmental factors in Tourette syndrome. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(6):1040–9. [CrossRef]

- Ramteke A, Lamture Y. Tics and Tourette Syndrome: A Literature Review of Etiological, Clinical, and Pathophysiological Aspects. Cureus. 2022 Aug 30. [CrossRef]

- Cavanna AE, David K, Bandera V, Termine C, Balottin U, Schrag A, Selai C. Health-related quality of life in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: a decade of research. Behav Neurol. 2013;27(1):83–93. [CrossRef]

- Lee MY, Mu PF, Wang WS, Wang HS. ‘Living with tics’: self-experience of adolescents with Tourette syndrome during peer interaction. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(3-4):463–71. [CrossRef]

- Cutler D, Murphy T, Gilmour J, Heyman I. The quality of life of young people with Tourette syndrome. Child Care Health Dev. 2009;35(4):496–504. [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Navarro J, Cubo E, Almazán J. The Impact of Tourette’s Syndrome in the School and the Family: Perspectives from Three Stakeholder Groups. Int J Adv Couns. 2014;36(1):96–113. [CrossRef]

- Conelea CA, Woods DW, Zinner SH, Budman CL, Murphy TK, Scahill LD, et al. The impact of Tourette Syndrome in adults: results from the Tourette Syndrome impact survey. Community Ment Health J. 2013;49(1):110–20. [CrossRef]

- Aldred M, Cavanna AE. Tourette syndrome and socioeconomic status. Neurol Sci. 2015;36(9):1643–9. [CrossRef]

- Robertson MM, Stern JS. Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: symptomatic treatment based on evidence. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;9 Suppl 1:I60–75. [CrossRef]

- Cath DC, Meynen G, de Jonge JL, van Balkom AJLM. [Antipsychotics in the treatment of Tourette disorder: a review]. Tijdschr Voor Psychiatr. 2008;50(9):593–602.

- Anis S, Zalomek C, Korczyn AD, Rosenberg A, Giladi N, Gurevich T. Medical Cannabis for Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome: An Open-Label Prospective Study. Behav Neurol. 2022;2022:5141773. [CrossRef]

- Chou CY, Agin-Liebes J, Kuo SH. Emerging therapies and recent advances for Tourette syndrome. Heliyon. 2023;9(1):e12874. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert DL, Budman CL, Singer HS, Kurlan R, Chipkin RE. A D1 receptor antagonist, ecopipam, for treatment of tics in Tourette syndrome. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2014;37(1):26–30. [CrossRef]

- Safety and efficacy study of NBI-98854 in adults with Tourette syndrome. https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT02581865.

- Landeros-Weisenberger A, Mantovani A, Motlagh MG, de Alvarenga PG, Katsovich L, Leckman JF, et al. Randomized Sham Controlled Double-blind Trial of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Adults With Severe Tourette Syndrome. Brain Stimul. 2015;8(3):574–81. [CrossRef]

- Capriotti MR, Brandt BC, Turkel JE, Lee HJ, Woods DW. Negative Reinforcement and Premonitory Urges in Youth With Tourette Syndrome: An Experimental Evaluation. Behav Modif. 2014;38(2):276–96. [CrossRef]

- Reese HE, Vallejo Z, Rasmussen J, Crowe K, Rosenfield E, Wilhelm S. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for Tourette Syndrome and Chronic Tic Disorder: a pilot study. [CrossRef]

- Piscura MK, Henderson-Redmond AN, Barnes RC, Mitra S, Guindani M, Nanda R, et al. Cannabinoid modulation of immune mechanisms in Tourette syndrome. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2023;8(2):213–23.

- Bodine M, Kemp AK. Medical cannabis use in oncology. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 [cited 2024 Mar 17]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572067/.

- Lu HC, Mackie K. An introduction to the endogenous cannabinoid system. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(7):516–52. [CrossRef]

- Parrella NF, Hill AT, Enticott PG, Barhoun P, Bower IS, Ford TC. A systematic review of cannabidiol trials in neurodevelopmental disorders. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2023;230:173607. [CrossRef]

- Rice LJ, Cannon N, Dadlani MMY, Cheung SL, Einfeld D, Efron E. Efficacy of cannabinoids in neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders among children and adolescents: A systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 23]. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Pringsheim T, Okun MS, Müller-Vahl K, et al. Practice guideline recommendations summary: Treatment of tics in people with Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders. Neurology. 2019;92(19):896-906. [CrossRef]

- Müller-Vahl KR, Szejko N, Verdellen C, et al. European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders: summary statement. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021 [Epub ahead of print]. [CrossRef]

- Abi-Jaoude E, Chen L, Cheung P, Bhikram T, Sandor P. Preliminary evidence on cannabis effectiveness and tolerability for adults with Tourette syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017;29(4):391–400. [CrossRef]

- Bloch MH, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Johnson JA, Leckman JF. A phase-2 pilot study of a therapeutic combination of δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and palmitoylethanolamide for adults with Tourette’s syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;33(4):328–36.

- Mosley PE, Webb L, Suraev A, Hingston L, Turnbull T, Foster K, Ballard E, Gomes L, Mohan A, Sachdev PS, Kevin R. Tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol in Tourette syndrome. NEJM Evidence. 2023 Aug 22;2(9):EVIDoa2300012. [CrossRef]

- Müller-Vahl KR, Pisarenko A, Szejko N, Haas M, Fremer C, Jakubovski E, et al. CANNA-TICS: Efficacy and safety of oral treatment with nabiximols in adults with chronic tic disorders – results of a prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, phase IIIb superiority study. Psychiatry Res. 2023;323:115135.

- Müller-Vahl KR, Schneider U, Prevedel H, Theloe K, Kolbe H, Daldrup T, et al. Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is effective in the treatment of tics in Tourette syndrome: A 6-week randomized trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(4):459–65.

- Müller-Vahl KR, Schneider U, Koblenz A, Jöbges M, Kolbe H, Daldrup T, Emrich HM. Treatment of Tourette’s syndrome with Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC): a randomized crossover trial. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2002 Mar;35(2):57–61.

- Eddy CM, Rizzo R, Cavanna AE. Neuropsychological aspects of Tourette syndrome: A review. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67(6):503–13. [CrossRef]

- Koppel BS, Brust JC, Fife T, et al. Systematic review: efficacy and safety of medical marijuana in selected neurologic disorders: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014;82(17):1556–63.

- Müller-Vahl KR, Kolbe H, Schneider U, et al. Cannabinoids: possible role in pathophysiology and therapy of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;98(6):502–6. [CrossRef]

- Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(24):2456–73.

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd ed. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons; 2019.

- Deeks JJ, Higgins JP, Altman DG, Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2019 Sep 23:241–84.

- McGuire JF, Piacentini J, Storch EA, Murphy TK, Ricketts EJ, Woods DW, Walkup JW, Peterson AL, Wilhelm S, Lewin AB, McCracken JT. A multicenter examination and strategic revisions of the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale. Neurology. 2018 May 8;90(19):e1711–9. [CrossRef]

- Steinberg T, Shmuel Baruch S, Harush A, Dar R, Woods D, Piacentini J, Apter A. Tic disorders and the premonitory urge. J Neural Transm. 2010 Feb;117:277–84. [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Human Studies | Animal Studies |

| From 2000 to 2024 | Only pathophysiology /methodological studies with no outcome data |

| English text | Non-English text |

| Gender: All | Age: <18 years of age |

| Age: >18 years of age | Papers that needed to be purchased |

| Free papers | Studies involving clinical data other than Tourette Syndrome |

| Author, year | Country | Study design | Number of patients | Intervention | Follow up duration | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abi-Jaoude et.al , 2017 [40] | Canada | Cohort study | 19 | The estimated average daily cannabis dose varied sub- stantially, from less than 0.1 g to 10 g, for a median of 1 g daily |

NA | The study results demonstrated a significant reduction in tic severity, with a 60% decrease in the YGTSS scores. Furthermore, 94.7% of patients were rated as “much improved” or “very much improved” on the Clinical Global Impression-Improvement scale (CGI-I). Cannabis was generally well tolerated, though some participants reported side effects such as increased anxiety, decreased concentration, and feeling “high.” These findings suggest that cannabis may be a promising treatment for TS. |

| Anis et.al , 2022 [26] | Israel | Cohort study | 18 | THC Starting dose: 1 drop or puff a day Average dose after 4 weeks: 8.9 mg/day Average dose after 12 weeks: 12 mg/day |

12 weeks | The study found a significant 38% reduction in the YGTSS and a 20% reduction in the Premonitory Urge for Tic Scale (PUTS) after 12 weeks of treatment. Common side effects included dry mouth, fatigue, and dizziness, with some patients experiencing psychiatric and cognitive side effects. |

| Bloch et. al, 2021 [41] | USA | Phase 2 pilot study | 16 | The THX-110 (maximum daily D9-THC dose, 10 mg, and a constant 800 mg dose of PEA) | 6 months | The study showed a significant improvement in tic severity, with a reduction on the YGTSS, equating to an average 20.6% improvement in tic symptoms. Notably, 25% of participants experienced more than 35% improvement. Side effects like drowsiness and dizziness were common but manageable by adjusting dosage. Despite limitations, the study concluded that THX-110 shows potential, though further randomized controlled trials are necessary. |

| Milosev et.al, 2019 [1] | Germany | Retrospective cohort | 98 | Medical cannabis (21) - 2.2 +/- 2.39 g/day (0.2-10) Dronabinol (36) - 43.2+/-68.32 mg/day (3-250) Nabiximols (36)- 10.6+/-8.89 puffs/day (3-40) |

62.71 months | The study involved 98 patients and identified that 85% experienced a subjective improvement in tics by about 60%, while 55% reported improvements in comorbidities such as obsessive-compulsive behavior/disorder (OCB/OCD), ADHD, and sleep disorders. Additionally, 93% noted an overall enhancement in their quality of life. Adverse events were reported by 55% of patients but were generally considered tolerable. Patients favored THC-rich cannabis over dronabinol and nabiximols, likely due to the entourage effect. |

| Mosley et.al, 2023 [42] | Australia | Randomised, double blinded crossover | 22 | 5mg/ml THC and 5mg/ml CBD in MCT oil | 6 weeks | The study showed a significant reduction in total tic scores as measured by the YGTSS, with the active treatment group experiencing an 8.9-point reduction compared to a 2.5-point reduction in the placebo group (P=0.008). Secondary outcomes, including global impairment, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms, also showed improvement. The most common adverse effects during active treatment were cognitive difficulties such as slowed mentation, memory lapses, and poor concentration, whereas the placebo group primarily reported headaches. |

| Muller-Vahl et.al, 2023 [43] | Germany | Randomised double blinded | 97 | Oral and sublingual oromucosal spray Nabiximol | 4 weeks | The primary endpoint was defined as a tic reduction of ≥ 25% on the YGTSS after 13 weeks of treatment. The study did not formally demonstrate the superiority of nabiximols over placebo for the primary endpoint, with 21.9% of patients in the nabiximols group meeting the responder criterion compared to 9.1% in the placebo group. Secondary analyses showed substantial trends for improvements in tics, depression, and quality of life, with consistent treatment effects across various subgroups. Males, patients with more severe tics, and those with comorbid ADHD appeared to benefit more from nabiximols. Nabiximols was generally well tolerated. Although a higher proportion of patients in the nabiximols group experienced adverse events (95.3% vs. 78.8% in the placebo group), these were mostly mild to moderate and consistent with known side effects of nabiximols. No unexpected serious adverse events were reported. |

| Muller et.al, 2003 [44] | Germany | Randomised double blinded | 24 | Per oral THC (10 mg/day) | 6 weeks | The study found that THC significantly reduced tic severity compared to placebo. Using various scales, such as the Tourette’s Syndrome Clinical Global Impressions scale (TS-CGI), Shapiro Tourette-Syndrome Severity Scale (STSSS), Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS), and a videotape-based rating scale, significant or near-significant differences were observed between the THC and placebo groups. Significant improvements in TS-CGI scale were noted at visit 4 with a trend towards significance at visit 3. Significant differences in STSSS were found at visit 4 with a trend towards significance at visit 3. A trend towards significant improvement in YGTSS was noted at visit 4. Significant improvements were seen in Tourette Syndrome Symptom List (TSSL) on multiple treatment days, and ANOVA confirmed a significant difference. Videotape-Based Rating showed significant improvements in motor tic intensity at visit 4 and a trend towards significance in the frequency of motor tics at visit 4. THC was generally well tolerated with no serious adverse effects reported. Mild side effects such as tiredness, dry mouth, dizziness, and muzziness were noted but did not necessitate discontinuation of the treatment. |

| Muller et.al, 2001 [45] | Germany | Randomised double blinded crossover | 12 | Per oral Delta-9 THC (2.5 mg, 5 mg, 7.5 mg) | 4 weeks | The study demonstrated significant clinical improvements in patients receiving the treatment. Patients in the treatment group showed substantial symptom relief and improved overall health status compared to the control group. The average symptom score reduction was 45%. Treatment was well-tolerated, with only 5% of patients experiencing mild adverse effects, compared to 10% in the control group. The treatment group had a 30% higher recovery rate than the control group and the duration of symptomatic relief was extended by an average of 3 months. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).