Submitted:

18 September 2024

Posted:

18 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Period

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

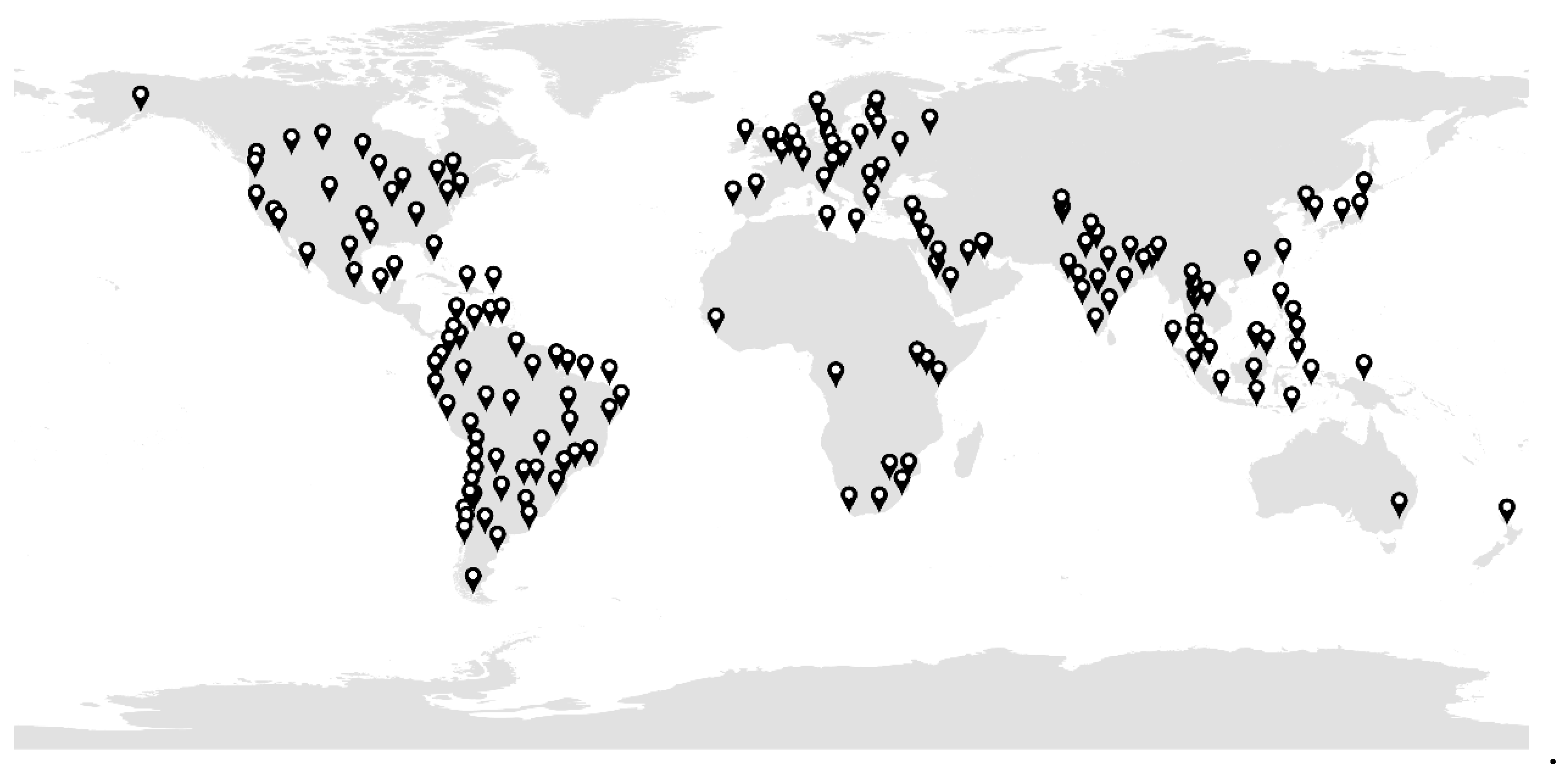

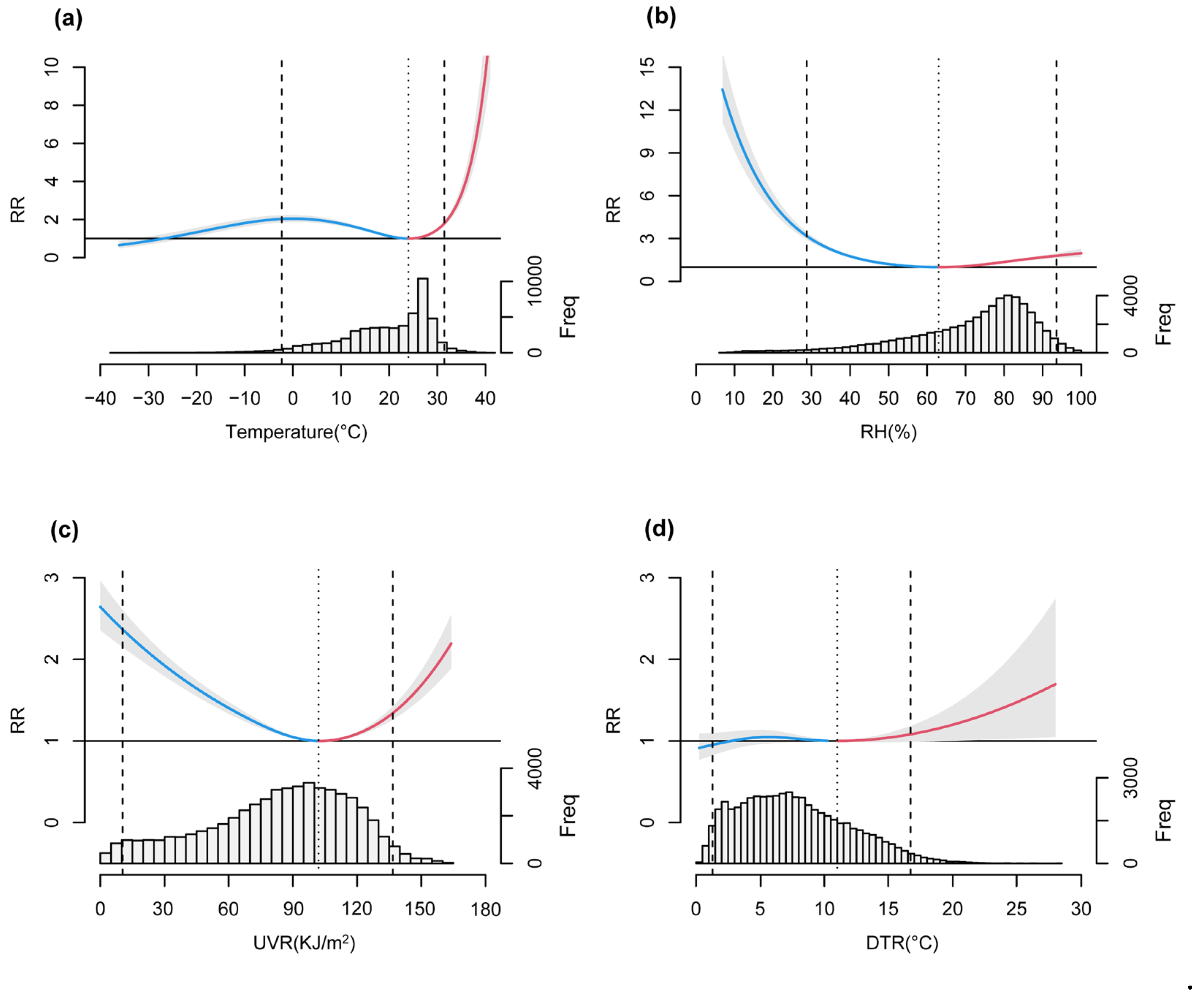

3.2. Nonlinear Relationships and Lagged Effects between COVID-19 Transmission and Meteorological Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. 2024. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- WHO. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2022-14.9-million-excess-deaths-were-associated-with-the-covid-19-pandemic-in-2020-and-2021 (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Adam, D. The Pandemic’s True Death Toll: Millions More than Official Counts. Nature 2022, 601, 312–315. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Paulson, K. R.; Pease, S. A.; Watson, S.; Comfort, H.; Zheng, P.; Aravkin, A. Y.; Bisignano, C.; Barber, R. M.; Alam, T.; et al. Estimating Excess Mortality Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Analysis of COVID-19-Related Mortality, 2020–21. The Lancet 2022, 399, 1513–1536. [CrossRef]

- WHO. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing---5-may-2023 (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Matteson, N. L.; Hassler, G. W.; Kurzban, E.; Schwab, M. A.; Perkins, S. A.; Gangavarapu, K.; Levy, J. I.; Parker, E.; Pride, D.; Hakim, A.; et al. Genomic Surveillance Reveals Dynamic Shifts in the Connectivity of COVID-19 Epidemics. Cell 2023, 186, 5690-5704.e20. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Campbell, H.; Kulkarni, D.; Harpur, A.; Nundy, M.; Wang, X.; Nair, H. The Temporal Association of Introducing and Lifting Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions with the Time-Varying Reproduction Number (R) of SARS-CoV-2: A Modelling Study across 131 Countries. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 193–202. [CrossRef]

- Flaxman, S.; Mishra, S.; Gandy, A.; Unwin, H. J. T.; Mellan, T. A.; Coupland, H.; Whittaker, C.; Zhu, H.; Berah, T.; Eaton, J. W.; et al. Estimating the Effects of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature 2020, 584, 257–261. [CrossRef]

- Hsiang, S.; Allen, D.; Annan-Phan, S.; Bell, K.; Bolliger, I.; Chong, T.; Druckenmiller, H.; Huang, L. Y.; Hultgren, A.; Krasovich, E.; et al. The Effect of Large-Scale Anti-Contagion Policies on the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nature 2020, 584, 262–267. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, W.; Liu, Y.; Du, B.; Chen, C.; Liu, Q.; Uddin, Md. N.; Jiang, S.; Chen, C.; et al. Identifying Novel Factors Associated with COVID-19 Transmission and Fatality Using the Machine Learning Approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 764, 142810. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, L.; Liang, Y.; Li, N.; Lourenço, J.; Yang, Y.; Lin, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhao, H.; et al. Indian Ocean Temperature Anomalies Predict Long-Term Global Dengue Trends. Science 2024, 384, 639–646. [CrossRef]

- Chan, K. H.; Peiris, J. S. M.; Lam, S. Y.; Poon, L. L. M.; Yuen, K. Y.; Seto, W. H. The Effects of Temperature and Relative Humidity on the Viability of the SARS Coronavirus. Adv. Virol. 2011, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, E. G.; Kelton, D.; Poljak, Z.; Van Kerkhove, M.; von Dobschuetz, S.; Greer, A. L. A Case-Crossover Analysis of the Impact of Weather on Primary Cases of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 113. [CrossRef]

- Tamerius, J. D.; Shaman, J.; Alonso, W. J.; Bloom-Feshbach, K.; Uejio, C. K.; Comrie, A.; Viboud, C. Environmental Predictors of Seasonal Influenza Epidemics across Temperate and Tropical Climates. PLOS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003194. [CrossRef]

- Sooryanarain, H.; Elankumaran, S. Environmental Role in Influenza Virus Outbreaks. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2015, 3, 347–373. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, X.; Ji, D.; Liu, J.; Yin, J.; Guo, Z. Climate Change Impacts the Epidemic of Dysentery: Determining Climate Risk Window, Modeling and Projection. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 104019. [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.-Y.; Bi, P.; Cazelles, B.; Zhou, S.; Huang, S.-Q.; Yang, J.; Pei, Y.; Wu, X.-X.; Fu, S.-H.; Tong, S.-L.; et al. How Environmental Conditions Impact Mosquito Ecology and Japanese Encephalitis: An Eco-Epidemiological Approach. Environ. Int. 2015, 79, 17–24. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, X.; Li, C.; Zhou, S. Decline in Malaria Incidence in a Typical County of China: Role of Climate Variance and Anti-Malaria Intervention Measures. Environ. Res. 2018, 167, 276–282. [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Gongsang, Q.; Wang, L.; Li, C.; Wu, X. Identification of Vulnerable Populations and Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Analysis of Echinococcosis in Tibet Autonomous Region of China. Environ. Res. 2020, 190, 110061. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. W.; Ramakrishnan, M. A.; Raynor, P. C.; Goyal, S. M. Effects of Humidity and Other Factors on the Generation and Sampling of a Coronavirus Aerosol. Aerobiologia 2007, 23, 239–248. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Qi, Y.; Luzzatto-Fegiz, P.; Cui, Y.; Zhu, Y. COVID-19: Effects of Environmental Conditions on the Propagation of Respiratory Droplets. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 7744–7750. [CrossRef]

- Matson, M. J.; Yinda, C. K.; Seifert, S. N.; Bushmaker, T.; Fischer, R. J.; van Doremalen, N.; Lloyd-Smith, J. O.; Munster, V. J. Effect of Environmental Conditions on SARS-CoV-2 Stability in Human Nasal Mucus and Sputum. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 2276–2278. [CrossRef]

- Chin, A. W. H.; Chu, J. T. S.; Perera, M. R. A.; Hui, K. P. Y.; Yen, H.-L.; Chan, M. C. W.; Peiris, M.; Poon, L. L. M. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in Different Environmental Conditions. The Lancet Microbe 2020, 1, e10. [CrossRef]

- Sagripanti, J.-L.; Lytle, C. D. Estimated Inactivation of Coronaviruses by Solar Radiation With Special Reference to COVID-19. Photochem. Photobiol. 2020, 96, 731–737. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Fareed, Z.; Shahzad, F.; He, X.; Shahzad, U.; Lina, M. The Nexus between COVID-19, Temperature and Exchange Rate in Wuhan City: New Findings from Partial and Multiple Wavelet Coherence. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 729, 138916. [CrossRef]

- Pequeno, P.; Mendel, B.; Rosa, C.; Bosholn, M.; Souza, J. L.; Baccaro, F.; Barbosa, R.; Magnusson, W. Air Transportation, Population Density and Temperature Predict the Spread of COVID-19 in Brazil. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9322. [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhu, Y. Association between Ambient Temperature and COVID-19 Infection in 122 Cities from China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 724, 138201. [CrossRef]

- Cherrie, M.; Clemens, T.; Colandrea, C.; Feng, Z.; Webb, D. J.; Dibben, C.; Weller, R. B. Ultraviolet A Radiation and COVID-19 Deaths: A Multi Country Study. medRxiv 2020. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Ma, W.; Huang, H.; Xu, K.; Qi, X.; Yu, H.; Deng, F.; Bao, C.; Huo, X. The Effect of Ambient Temperature on the Activity of Influenza and Influenza like Illness in Jiangsu Province, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 684–691. [CrossRef]

- Chan, K. H.; Peiris, J. S. M.; Lam, S. Y.; Poon, L. L. M.; Yuen, K. Y.; Seto, W. H. The Effects of Temperature and Relative Humidity on the Viability of the SARS Coronavirus. Adv. Virol. 2011, 2011, 734690. [CrossRef]

- Moriyama, M.; Hugentobler, W. J.; Iwasaki, A. Seasonality of Respiratory Viral Infections. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2020, 7, 83–101. [CrossRef]

- Nottmeyer, L.; Armstrong, B.; Lowe, R.; Abbott, S.; Meakin, S.; O’Reilly, K. M.; von Borries, R.; Schneider, R.; Royé, D.; Hashizume, M.; et al. The Association of COVID-19 Incidence with Temperature, Humidity, and UV Radiation – A Global Multi-City Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158636. [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Zhao, W.; Pereira, P. Meteorological Factors’ Effects on COVID-19 Show Seasonality and Spatiality in Brazil. Environ. Res. 2022, 208, 112690. [CrossRef]

- Sobral, M. F. F.; Duarte, G. B.; da Penha Sobral, A. I. G.; Marinho, M. L. M.; de Souza Melo, A. Association between Climate Variables and Global Transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 729, 138997. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhou, J.; Yao, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Xu, X.; He, X.; Wang, B.; Fu, S.; Niu, T.; et al. Impact of Meteorological Factors on the COVID-19 Transmission: A Multi-City Study in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 726, 138513. [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, F.; Shahzad, U.; Fareed, Z.; Iqbal, N.; Hashmi, S. H.; Ahmad, F. Asymmetric Nexus between Temperature and COVID-19 in the Top Ten Affected Provinces of China: A Current Application of Quantile-on-Quantile Approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 736, 139115. [CrossRef]

- Karim, R.; Akter, N. Effects of Climate Variables on the COVID-19 Mortality in Bangladesh. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2022, 150, 1463–1475. [CrossRef]

- Babu, S. R.; Rao, N. N.; Kumar, S. V.; Paul, S.; Pani, S. K. Plausible Role of Environmental Factors on COVID-19 Transmission in the Megacity Delhi, India. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 2075–2084. [CrossRef]

- Colston, J. M.; Hinson, P.; Nguyen, N.-L. H.; Chen, Y. T.; Badr, H. S.; Kerr, G. H.; Gardner, L. M.; Martin, D. N.; Quispe, A. M.; Schiaffino, F.; et al. Effects of Hydrometeorological and Other Factors on SARS-CoV-2 Reproduction Number in Three Contiguous Countries of Tropical Andean South America: A Spatiotemporally Disaggregated Time Series Analysis. IJID Regions 2023, 6, 29–41. [CrossRef]

- Ogaugwu, C.; Mmaduakor, C.; Adewale, O. Association of Meteorological Factors With COVID-19 During Harmattan in Nigeria. Environ. Health Insights 2023, 17, 11786302231156298. [CrossRef]

- Sera, F.; Armstrong, B.; Abbott, S.; Meakin, S.; O’Reilly, K.; von Borries, R.; Schneider, R.; Royé, D.; Hashizume, M.; Pascal, M.; et al. A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Meteorological Factors and SARS-CoV-2 Transmission in 409 Cities across 26 Countries. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5968. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Wu, Y.; Jing, W.; Liu, J.; Du, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, M. Non-Linear Correlation between Daily New Cases of COVID-19 and Meteorological Factors in 127 Countries. Environ. Res. 2021, 193, 110521. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Wu, Y.; Jing, W.; Liu, J.; Du, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, M. Association between Meteorological Factors and Daily New Cases of COVID-19 in 188 Countries: A Time Series Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 780, 146538. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Bo, Y.; Lin, C.; Li, H. B.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hossain, M. S.; Chan, J. W. M.; Yeung, D. W.; Kwok, K.; et al. Meteorological Factors and COVID-19 Incidence in 190 Countries: An Observational Study. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 757, 143783. [CrossRef]

- Zha, Q.; Chai, G.; Sha, Y.; Zhang, Z.-G. Impact of Diurnal Temperature Range on Rhinitis in Lanzhou, China: Accounting for COVID-19 Effects. Urban Clim. 2023, 52, 101693. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Gao, L.; Shao, N.-Y. Non-Linear Link between Temperature Difference and COVID-19: Excluding the Effect of Population Density. J. Infect. Dev. Countr. 2021, 15, 230–236. [CrossRef]

- Guasp, M.; Laredo, C.; Urra, X. Higher Solar Irradiance Is Associated With a Lower Incidence of Coronavirus Disease 2019. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2269–2271. [CrossRef]

- Merow, C.; Urban, M. C. Seasonality and Uncertainty in Global COVID-19 Growth Rates. Proc Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117, 27456–27464. [CrossRef]

- Isaia, G.; Diémoz, H.; Maluta, F.; Fountoulakis, I.; Ceccon, D.; di Sarra, A.; Facta, S.; Fedele, F.; Lorenzetto, G.; Siani, A. M.; et al. Does Solar Ultraviolet Radiation Play a Role in COVID-19 Infection and Deaths? An Environmental Ecological Study in Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 757, 143757. [CrossRef]

- Carleton, T.; Cornetet, J.; Huybers, P.; Meng, K. C.; Proctor, J. Global Evidence for Ultraviolet Radiation Decreasing COVID-19 Growth Rates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2021, 118, e2012370118. [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Bukhari, Q.; Jameel, Y.; Shabnam, S.; Erzurumluoglu, A. M.; Siddique, M. A.; Massaro, J. M.; D’Agostino, R. B. COVID-19 and Climatic Factors: A Global Analysis. Environ. Res. 2021, 193, 110355. [CrossRef]

- Sarkodie, S. A.; Owusu, P. A. Impact of Meteorological Factors on COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from Top 20 Countries with Confirmed Cases. Environ. Res. 2020, 191, 110101. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yin, J.; Li, C.; Xiang, H.; Lv, M.; Guo, Z. Natural and Human Environment Interactively Drive Spread Pattern of COVID-19: A City-Level Modeling Study in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 756, 143343. [CrossRef]

- Ledebur, K.; Kaleta, M.; Chen, J.; Lindner, S. D.; Matzhold, C.; Weidle, F.; Wittmann, C.; Habimana, K.; Kerschbaumer, L.; Stumpfl, S.; et al. Meteorological Factors and Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions Explain Local Differences in the Spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Austria. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1009973. [CrossRef]

- Tzampoglou, P.; Loukidis, D. Investigation of the Importance of Climatic Factors in COVID-19 Worldwide Intensity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7730. [CrossRef]

- Naffeti, B.; Bourdin, S.; Ben Aribi, W.; Kebir, A.; Ben Miled, S. Spatio-Temporal Evolution of the COVID-19 across African Countries. Front. Public Health 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Diouf, I.; Sy, S.; Senghor, H.; Fall, P.; Diouf, D.; Diakhaté, M.; Thiaw, W. M.; Gaye, A. T. Potential Contribution of Climate Conditions on COVID-19 Pandemic Transmission over West and North African Countries. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 34. [CrossRef]

- Chu, B.; Chen, R.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H. Effects of High Temperature on COVID-19 Deaths in U.S. Counties. GeoHealth 2023, 7, e2022GH000705. [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, J. A.; Lopez-Feldman, A.; Pereda, P. C.; Rivera, N. M.; Ruiz-Tagle, J. C. Association between Long-Term Air Pollution Exposure and COVID-19 Mortality in Latin America. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0280355. [CrossRef]

- Chelani, A. B.; Gautam, S. The Influence of Meteorological Variables and Lockdowns on COVID-19 Cases in Urban Agglomerations of Indian Cities. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2022, 36, 2949–2960. [CrossRef]

- Bolaño-Ortiz, T. R.; Camargo-Caicedo, Y.; Puliafito, S. E.; Ruggeri, M. F.; Bolaño-Diaz, S.; Pascual-Flores, R.; Saturno, J.; Ibarra-Espinosa, S.; Mayol-Bracero, O. L.; Torres-Delgado, E.; et al. Spread of SARS-CoV-2 through Latin America and the Caribbean Region: A Look from Its Economic Conditions, Climate and Air Pollution Indicators. Environ. Res. 2020, 191, 109938. [CrossRef]

- Wahltinez, O.; Cheung, A.; Alcantara, R.; Cheung, D.; Daswani, M.; Erlinger, A.; Lee, M.; Yawalkar, P.; Lê, P.; Navarro, O. P.; et al. COVID-19 Open-Data a Global-Scale Spatially Granular Meta-Dataset for Coronavirus Disease. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 162. [CrossRef]

- Badr, H. S.; Zaitchik, B. F.; Kerr, G. H.; Nguyen, N.-L. H.; Chen, Y.-T.; Hinson, P.; Colston, J. M.; Kosek, M. N.; Dong, E.; Du, H.; et al. Unified Real-Time Environmental-Epidemiological Data for Multiscale Modeling of the COVID-19 Pandemic. medRxiv 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 Global Reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [CrossRef]

- Gasparrini, A.; Armstrong, B.; Kenward, M. G. Distributed Lag Non-Linear Models. Stat. Med. 2010, 29, 2224–2234. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, C.; Ding, C.; Zhai, M.; Xu, K.; Wei, L.; Wang, J. Random Forest Regression on Joint Role of Meteorological Variables, Demographic Factors, and Policy Response Measures in COVID-19 Daily Cases: Global Analysis in Different Climate Zones. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 79512–79524. [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Yao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Meng, X.; Ji, J. S.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W.; Kan, H. Warmer Weather Unlikely to Reduce the COVID-19 Transmission: An Ecological Study in 202 Locations in 8 Countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 753, 142272. [CrossRef]

- Analitis, A.; Katsouyanni, K.; Biggeri, A.; Baccini, M.; Forsberg, B.; Bisanti, L.; Kirchmayer, U.; Ballester, F.; Cadum, E.; Goodman, P. G.; et al. Effects of Cold Weather on Mortality: Results from 15 European Cities within the PHEWE Project. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 168, 1397–1408. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B. G.; Bell, M. L. Weather-Related Mortality: How Heat, Cold, and Heat Waves Affect Mortality in the United States. Epidemiology 2009, 20, 205–213. [CrossRef]

- Gasparrini, A.; Guo, Y.; Hashizume, M.; Lavigne, E.; Zanobetti, A.; Schwartz, J.; Tobias, A.; Tong, S.; Rocklöv, J.; Forsberg, B.; et al. Mortality Risk Attributable to High and Low Ambient Temperature: A Multicountry Observational Study. The Lancet 2015, 386, 369–375. [CrossRef]

- Pastorino, B.; Touret, F.; Gilles, M.; de Lamballerie, X.; Charrel, R. Evaluation of Heating and Chemical Protocols for Inactivating SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv 2020. [CrossRef]

- Fares, A. Factors Influencing the Seasonal Patterns of Infectious Diseases. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 4, 128–132.

- Cheng, J.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, R.; Wang, X.; Jin, L.; Song, J.; Su, H. Impact of Diurnal Temperature Range on Human Health: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2014, 58, 2011–2024. [CrossRef]

- Sapolsky, R. M.; Romero, L. M.; Munck, A. U. How Do Glucocorticoids Influence Stress Responses? Integrating Permissive, Suppressive, Stimulatory, and Preparative Actions. Endocr. Rev. 2000, 21, 55–89. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; He, L.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, L.; Qin, W.; Zhang, X. Evaluation and analysis of MODIS and VIIRS satellite aerosol optical depth products over China. China Environ. Sci. 2024, 44, 4211-4229.

- Cai, J.; Sun, W.; Huang, J.; Gamber, M.; Wu, J.; He, G. Indirect Virus Transmission in Cluster of COVID-19 Cases, Wenzhou, China, 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1343–1345. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qian, H.; Hang, J.; Chen, X.; Cheng, P.; Ling, H.; Wang, S.; Liang, P.; Li, J.; Xiao, S.; et al. Probable Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in a Poorly Ventilated Restaurant. Build. Environ. 2021, 196, 107788. [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Jimenez, J. L.; Prather, K. A.; Tufekci, Z.; Fisman, D.; Schooley, R. Ten Scientific Reasons in Support of Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2. The Lancet 2021, 397, 1603–1605. [CrossRef]

- Morris, D. H.; Yinda, K. C.; Gamble, A.; Rossine, F. W.; Huang, Q.; Bushmaker, T.; Fischer, R. J.; Matson, M. J.; Van Doremalen, N.; Vikesland, P. J.; et al. Mechanistic Theory Predicts the Effects of Temperature and Humidity on Inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 and Other Enveloped Viruses. eLife 2021, 10, e65902. [CrossRef]

- Kormuth, K. A.; Lin, K.; Qian, Z.; Myerburg, M. M.; Marr, L. C.; Lakdawala, S. S. Environmental Persistence of Influenza Viruses Is Dependent upon Virus Type and Host Origin. mSphere 2019, 4, 10.1128/msphere.00552-19. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Elankumaran, S.; Marr, L. C. Relationship between Humidity and Influenza A Viability in Droplets and Implications for Influenza’s Seasonality. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e46789. [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Marr, L. C. Humidity-Dependent Decay of Viruses, but Not Bacteria, in Aerosols and Droplets Follows Disinfection Kinetics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 1024–1032. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, R. P.; Lee, T. K. Adverse Effects of Ultraviolet Radiation: A Brief Review. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2006, 92, 119–131. [CrossRef]

| Types | Variables | Mean | Min | Median | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 | Cumulative incidence rate (per million) | 41647.9 | 3.1 | 32969.6 | 217288.7 |

| Daily incidence rate (per million) | 133.7 | 0 | 39.6 | 8184.2 | |

| Meteorological factors | Daily mean temperature (°C) | 19.6 | -36.1 | 22 | 41.2 |

| Diurnal temperature range (°C) | 7.7 | 0.2 | 7.2 | 28.1 | |

| Daily mean relative humidity (%) | 71.6 | 6.9 | 76 | 100 | |

| Daily mean ultraviolet radiation (KJ/m2) | 82.8 | 0.4 | 87.6 | 164.8 | |

| Daily mean surface pressure(kPa) | 97.4 | 72.9 | 99.9 | 104.1 | |

| Daily mean cloud cover (%) | 57.4 | 0 | 62.4 | 100 | |

| Daily mean wind speed (m/s) | 3 | 0.3 | 2.6 | 13.8 | |

| Daily precipitation (mm) | 2.6 | 0 | 0 | 410 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).