Submitted:

17 September 2024

Posted:

18 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Data

2.2. Statistical Analysis and Model Training

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

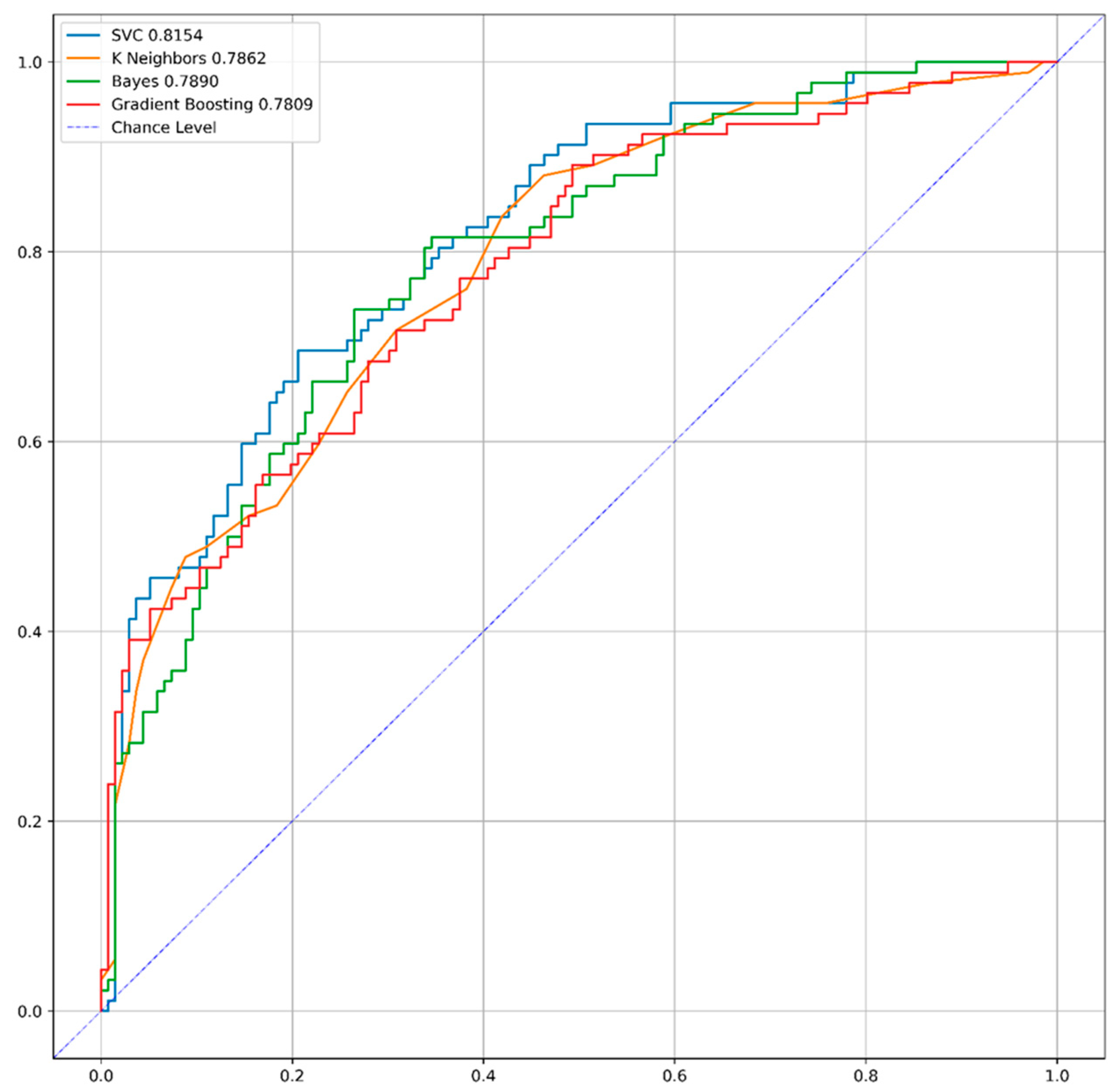

3.2. Model Performance

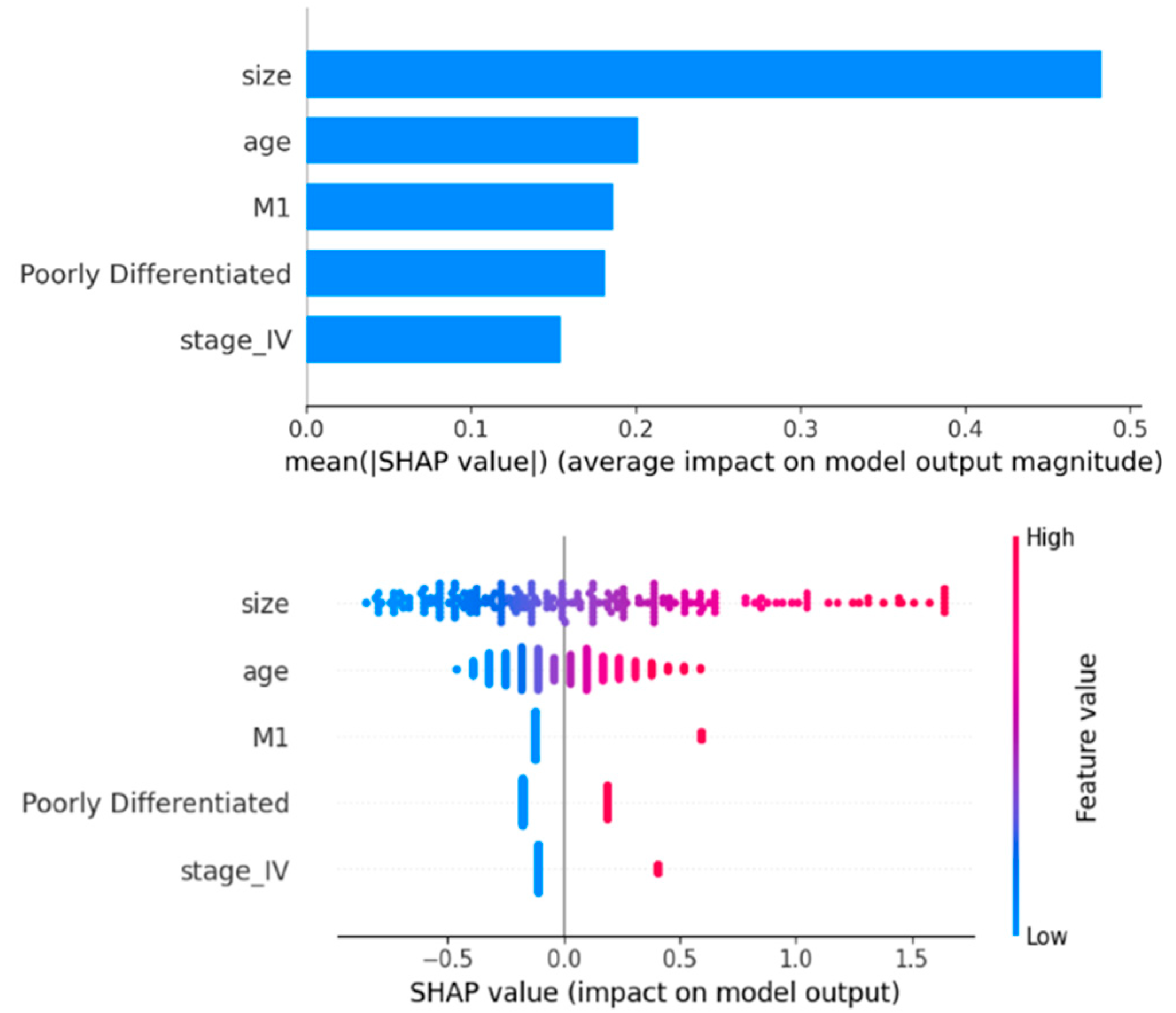

3.3. Feature Importance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aytekin, M.N.; Öztürk, R.; Amer, K.; Yapar, A. Epidemiology, incidence, and survival of synovial sarcoma subtypes: SEER database analysis. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery 2020, 28(2), 2309499020936009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Song, R.; Sun, T.; Hou, B.; Hong, G.; Mallampati, S.; et al. Survival changes in patients with synovial sarcoma, 1983–2012. Journal of Cancer 2017, 8(10), 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, W.; Feng, Q.; Sun, W.; Yan, W.; Wang, C.; et al. Clinical significance and risk factors of local recurrence in synovial sarcoma: A retrospective analysis of 171 cases. Frontiers in Surgery 2022, 8, 736146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Silva, M.C.; McMahon, A.D.; Reid, R. Prognostic factors associated with local recurrence, metastases, and tumor-related death in patients with synovial sarcoma. American Journal of Clinical Oncology 2004, 27(2), 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doll, K.M.; Rademaker, A.; Sosa, J.A. Practical guide to surgical data sets: Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) database. JAMA Surgery 2018, 153(6), 588–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajkomar, A.; Dean, J.; Kohane, I. Machine learning in medicine. New England Journal of Medicine 2019, 380(14), 1347–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourou, K.; Exarchos, K.P.; Papaloukas, C.; Sakaloglou, P.; Exarchos, T.; Fotiadis, D.I. Applied machine learning in cancer research: A systematic review for patient diagnosis, classification and prognosis. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2021, 19, 5546–5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourou, K.; Exarchos, T.P.; Exarchos, K.P.; Karamouzis, M.V.; Fotiadis, D.I. Machine learning applications in cancer prognosis and prediction. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2015, 13, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seger, C. An investigation of categorical variable encoding techniques in machine learning: Binary versus one-hot and feature hashing. 2018.

- Suthaharan, S.; Suthaharan, S. Support vector machine. Machine learning models and algorithms for big data classification: Thinking with examples for effective learning. 2016, 207–35.

- Kramer, O.; Kramer, O. K-nearest neighbors. Dimensionality reduction with unsupervised nearest eighbors. 2013, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Webb, G.I.; Liu, L.; Ma, X. A novel selective naïve Bayes algorithm. Knowledge-Based Systems 2020, 192, 105361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; et al. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Rufibach, K. Use of Brier score to assess binary predictions. Journal of clinical epidemiology 2010, 63(8), 938–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Broeck, G.; Lykov, A.; Schleich, M.; Suciu, D. On the tractability of SHAP explanations. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 2022, 74, 851–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee Y-h Bang, H.; Kim, D.J. How to establish clinical prediction models. Endocrinology and Metabolism 2016, 31(1), 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdar, M.; Acharya, U.R.; Sarrafzadegan, N.; Makarenkov, V. NE-nu-SVC: A new nested ensemble clinical decision support system for effective diagnosis of coronary artery disease. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 167605–167620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Merchant, M. Risk factors including age, stage and anatomic location that impact the outcomes of patients with synovial sarcoma. Medical Sciences 2018, 6(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlenterie, M.; Ho, V.K.; Kaal, S.E.; Vlenterie, R.; Haas, R.; Van Der Graaf, W.T. Age as an independent prognostic factor for survival of localised synovial sarcoma patients. British Journal of Cancer 2015, 113(11), 1602–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazendam, A.M.; Popovic, S.; Munir, S.; Parasu, N.; Wilson, D.; Ghert, M. Synovial sarcoma: A clinical review. Current Oncology 2021, 28(3), 1909–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staartjes, V.E.; Kernbach, J.M. Significance of external validation in clinical machine learning: Let loose too early? The Spine Journal 2020, 20(7), 1159–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).