Submitted:

17 September 2024

Posted:

17 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

| Selected Technology | Definition |

| Digital Phenotyping | Mobile phone data, such as the number and length of calls and texts, accelerometry, GPS, and voice quality, can be used in conjunction with machine learning algorithms to predict, differentiate, and track mental illness. |

| Wearables | Devices that measure skin conductance, EKG, heart-rate, heart-rate variability, and EEG to detect changes in respiration, cardiac activity, and circadian rhythm. These data can be used to provide information about an individual’s autonomic function, a potentially useful indicator for PTSD severity and treatment outcomes. |

| Natural language processing (NLP) and Facial detection | AI-assisted analysis of the tone, content, quality, and sophistication of patient speech and writing can be used to identify different mood states, detect presence of psychiatric symptoms, and predict future behavior. Facial recognition can also detect facial valence and mood state in response to questions or emotional stimuli to predict diagnostic status and symptom severity. |

| Immersive technologies (VR, AR, 3DMR) | Use of an immersive head-mounted display (HMD), 180-degree monitors, or projection goggles can aid extinction training by recreating virtual environments and/or projecting virtual objects relevant to a patient’s traumatic experience onto the real-life environment. Can be used in conjunction with a treadmill (3MDR) or with other sensory information to increase environmental immersion and reduce avoidance behaviors. |

| Neurofeedback Training | EEG, when used with a computer interface, can provide real-time data of patient brain activity. Patients can learn to modulate their brain activity in response to stimuli presented through the computer interface when targeted brain rhythms are achieved. |

| Apps | Mobile platforms accessed via smartphone that screen for psychiatric symptoms, provide psychoeducation, coping strategies, CBT, and additional treatment resources. |

| Study | Technology | Purpose | Sample Demographic | Method | Findings | Notes |

| Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Facial Feature Interpretation | ||||||

| [Schultebraucks et al. (2022)] | Voice and audio feature extraction with ML | PTSD and MDD diagnostic prediction post-trauma | 81 patients admitted to an emergency department of a Level-1 Trauma Unit following a life-threatening traumatic event | The audio and video of the patient responses to five open-ended questions acted as an input for a deep neural network which was trained to extract facial features of emotion and their intensity, speech prosody, movement parameters, and natural language content. | The algorithm was able to predict a CAPS-5 PTSD diagnosis with an AUC of .90 as well as depression status with an AUC of .86 | |

| [Marmar et al. (2019)] | Speech extraction with ML | PTSD detection from recordings of clinical interviews (with clinical psychologist) | Warzone veterans—52 with PTSD and 77 without | RF algorithm to predict PTSD presence based on speech features in clinical interviews | AUC of .954 and classification accuracy of 89.1%. Probability of PTSD was higher for markers that indicated slower, more monotonous speech, less change in tonality, and less activation | |

| [Gavrilescu et al. (2019)] | Facial microexpression detection with ML | PTSD, anxiety, depression detection | 128 caucasian, half male. 20 with MDD, 19 GAD, 17 PTSD | Multi-layered ML algorithm used to predict presence of PTSD, MDD, or anxiety through analyzing facial features while subjects watched emotion-inducing or emotion-neutral videos | The model was able to discriminate with 93% accuracy between healthy subjects and those affected by Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) or Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and 85% for Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) | |

| [He et al. (2017)] | Natural language processing | PTSD detection from patient narratives | 300 Veterans- half with diagnosed PTSD | Used NLP and text mining using “N-gram” features approach on patient writing narratives to predict likelihood of PTSD diagnosis | AUCs of the four text classifiers—DT, NB, SVM, and PSM—were .68, .90, .86 and .94 respectively | N-gram features count the number of co-occurring words within a given window of word. DT: decision tree; NB: naive Bayes; SVM: support vector machine; PSM: product score model |

| [He et al. (2019)] | Natural language processing | PTSD detection from patient narratives and online-survey responses | 99 trauma survivors, 34 with a self-reported PTSD diagnosis and 65 without PTSD | Used PSM model on patient writing narratives alone or in conjunction with responses to a 21-question online-survey to predict presence of PTSD diagnosis | Analysis of patient text-responses alone yielded an accuracy of 84%, and a sensitivity of 100% while combining online survey responses with Bayesian modeling increased accuracy to 97%. | |

| [Sawalha et al. (2022)] | Natural language processing | PTSD detection from interview transcripts | 188 individuals with PTSD, 87 without. Used text data from a popular dataset, the Audio/Visual Emotion Challenge and Workshop [(AVEC 2019)] (23) | Sentiment text analysis (sub-branch of NLP) gathered from computer conducted semi-structured interview to detect PTSD | Achieved highest mean accuracy rate of 80.4%, with an AUC of .80 and an F1 score of .85 and .72 for the non-PTSD and PTSD groups, respectively. | |

| Digital phenotyping | ||||||

| [Place et al. (2017)] | Digital phenotyping using smartphone | PTSD and depression symptom prediction | 73 participants (67% male, 33% veterans) who reported at least one symptom of PTSD or depression on the Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD) or the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) | Participants were given an Android device to use as their normal phone. A mobile app app gathered data on messaging, outgoing calls, location, device use, speaking rate, and voice quality during normal phone use in addition to weekly voicemail diary entries for a period of 12 weeks. | Fatigue, interest in activities, and social connectedness were predicted using LASSO regression trained on data (GPS, messages sent, outgoing calls) from the prior week with AUCs of .56, .75, and .83 respectively. Depressed mood was predicted from audio data with an AUC of .74 | |

| [Friedman et al. (2020)] | Digital phenotyping using smartphone | PTSD diagnostic prediction | 228 Females, 150 with PTSD+emotional instability and history of child abuse, 35 healthy trauma controls with child abuse history, and 45 healthy controls | Passively-collected smartphone-based GPS data of distance travelled from home over a period of seven days | Average time away from home and distance traveled from home did not correlate with avoidance symptoms (PCL5-7 item). Both trauma-exposed groups stayed closer to their homes on weekends when compared to controls (PTSD: b = -0.618, p = .004; HTC: b = − 0.593, p = .032), with only the PTSD group differing significantly from controls on weekdays (b = − 0.340, p = .048). Including covariates for depression and health status dropped this relationship out of significance |

|

| [Lekkas and Jacobson (2021)] | Digital phenotyping using smartphone | PTSD diagnostic prediction | 185 females, 150 with PTSD and 35 healthy trauma controls (same as above, but without healthy control group) | Used leave one subject out (LOSO) and k-fold cross-validation on GPS data tracking daily time spent away from home and maximum distance travelled from home to predict PTSD diagnostic likelihood using data from Friedman et al., 2020 | Diagnostic group status predicted with an AUC = .816, sensitivity = .743, specificity = .8, and an accuracy = .771. | |

| Wearables | ||||||

| [Hinrichs et al. (2017)] | Mobile skin conductance | PTSD diagnostic prediction | 63 trauma-exposed patients in the emergency department (51% male, 76% Black). Motor vehicle accident was most commonly reported trauma (65.1%) | Feasibility study for measuring skin conductance (SC) via mobile device (eSense) in emergency department patients who had experienced a trauma approximately 1 year before | Individuals with PTSD showed significantly greater SCR than individuals without PTSD during trauma interview (P = .006). The AUC for the ROC curve analysis for SCR on PTSD diagnosis was 0.79 (p = .001). SCR during trauma interview also correlated positively with PTSD symptom total score on the PSS(b = 0.42, p = .001). | SCR: Skin Conductance Reactivity, PSS: PTSD Symptom Scale |

| [Hinrichs et al. (2019)] | Mobile skin conductance | PTSD diagnostic prediction | 107 trauma-exposed patients in the emergency department (56% male, 82% Black). Motor vehicle accident was the most commonly reported trauma (59%) | Used mobile SC (eSense) to predict the future incidence of PTSD in emergency department patients who had experienced a trauma within the past 12 hours. Used a series latent growth mixture modeling (LGMM) to classify participants into future PTSD symptom trajectories | SCR during trauma interview was significantly correlated with the probability of being in the chronic PTSD trajectory (r = 0.489, p < 0.000001; AUC = .90), with SCR being the most significant predictor of the chronic PTSD trajectory (p < 0.00001) when controlling for demographic and clinical measures. | |

| [Wiltshire et al. (2022)] | Mobile skin conductance | PTSD symptom assessment | 62 trauma-exposed children (54% male, 79% black, average age 9.11, SD = 0.37) | Measured SC using eSense in trauma-exposed children during a standardized trauma interview | Degree of trauma exposure was significantly correlated with SCR (i.e., change in SCL from baseline to maximum SCL) during the TESI-C interview (r(55) = 0.30, p = .023, ) trauma exposure alone significantly predicted SCR after controlling for other variables, R2change = 0.129, F (1,50)change = 8.31, p = .006. Hyperarousal symptoms predict SCL habituation r2 = .05, F(1,48) change = 4.31, p = .043 | SCL habituation is difference between maximum SC and end of interview SC. |

| [Grasser et al. (2022)] | Mobile skin conductance | PTSD symptom assessment | 86 refugee youth (aged 7-17, 41.8% male, all Arab) with an average of 4 traumatic experiences | Measured SC using eSense in trauma-exposed children during a standardized trauma interview | Trauma exposure was significantly associated with SCR during trauma interview (R2 = .084, p = .042). SCR during trauma interview was positively correlated with reexperiencing (R2 = .127, p = .028), and hyperarousal symptoms (R2 = .123, p = .048) | |

| [Cakmak et al. (2021)] | Wrist-worn sensor | PTSD diagnostic prediction | 1618 emergency department patients with recent (<72hour) trauma-exposure (36% male) | Collected survey and HRV data from ED patients recently exposed to trauma and used these data with a machine learning model (SVM log regression, Multilayer perceptron) to detect PTSD diagnostic status in the 8 weeks following trauma | AUC of .74 in predicting PTSD at 8wk using survey, only .54 with HRV, and .73 when combining survey and HRV | |

| [Tsanas et al. (2020)] | Wrist-worn sensor | PTSD symptom tracking | 42 participants with PTSD (38% male), 43 traumatized controls, and 30 healthy controls. | Wrist-worn sensor detecting actigraphy, light, and temperature data over 7 days | Participants with PTSD showed more fragmented sleep patterns and greater intraday variability compared with traumatized and healthy control groups, showing statistically significant (p < .05) and strong associations (|R| > 0.3). | |

| [Reinersten et al. (2017)] | Ambulatory ECG (Holter) monitor | PTSD diagnostic prediction | 24 male veterans with clinical diagnosis of PTSD and 25 healthy controls | Detected heart rate variability (HRV) features (statistical moments, power spectral density components, entropy, and acceleration / deceleration capacity) using a 24-hour Holter monitor to create a machine learning model for predicting PTSD diagnostic status | Using logistic regression models on an out-of-sample test set data yielded an AUC of 0.86 for detecting PTSD diagnostic status. 24-hours of data from sample yielded AUC of 0.72 and random segments resulted in AUC of .67 | |

| [Sadeghi et al. (2022)] | Smartwatch | PTSD symptom detection | 99 veterans with PTSD diagnosis (83% male) | Used a smartwatch-based app to collect data related to heart rate, body acceleration, and self-reported hyperarousal events over several days to create machine learning models for predicting onset of PTSD hyperarousal events | Of several machine learning algorithms (Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, Logistic Regression and XGBoost), XGBoost had the best performance in detecting onset of PTSD symptoms with 83% accuracy and an AUC of 0.70, where average heart rate, minimum heart rate and average body acceleration were the greatest predictors. | Model was trained on a subset of the sample (70%) and tested on the remaining participants (30%). |

| Immersive Technologies | ||||||

| [McLay et al. (2017)] | VR head-mounted display (HMD) | PTSD treatment | 83 active-duty service members (100% male) combat-related PTSD randomized to VRET (n = 42) or control (n = 41) | VRET + PE + in vivo exposure vs control group that viewed a moving image on computer during imaginal exposure. Participants completed 8-12 90-minute sessions over nine weeks. | Both treatment groups showed significant reduction in CAPS scores after nine weeks of treatment and at three-month follow up (p < .001), but there were no between-group differences. | |

| [Bisson et al. (2020)] | 3MDR (VRET+ EMDR + treadmill) | PTSD treatment | 42 veterans (all male) with treatment-resistant combat-related PTSD randomized to 3MDR (n = 21) or waitlist control (n=21). | During exposure, instead of immersing in the VR environment, participants viewed an image of the VR environment on a computer screen while walking on treadmill (3MDR). Participants received two preparation sessions followed by six 60 minute 3MDR sessions and one concluding session over nine weeks. Control group received intervention after 12 weeks. | At week 12, difference in mean CAPS scores between the immediate and delayed 3MDR arms was 9.56 (95% CI [− 17.15, −1.97], p = .014) with an estimated effect size of d = 0.65. These effects were maintained at 26 week follow-up. PCL-5 (−11.67, 95% CI [–20.06, −3.27], p = .006), GAD-7 (-5.14, 95% CI [−9.42, −0.86], p = .0018) and insomnia (ISI; -7.34, 95% CI [−10.64, −4.01], p < .001) also were improved at 12 weeks. |

3MDR: multimodal motion-assisted exposure therapy. |

| Van [Gelderen et al. (2020)] | 3MDR (VRET+ EMDR + treadmill) | PTSD treatment | 42 veterans (98% male) with treatment-resistant combat-related PTSD randomized to 3MDR (n = 21) or waitlist control (n = 21) | Same protocol as Bisson et al. except control group consisted of treatment as usual without trauma-related treatment. Both groups received similar amount of treatment hours. Experimental group received six 70-90 minute sessions over six weeks with an option of continuing up to 10 weeks. | Greater decrease in CAPS scores in 3MDR group vs control group at 16 weeks (F(1,37) = 6.43, p = .016; d = 0.83). PCL-5 was not significant (F(1,37) = 2.51, p = .121; d = 0.51) | |

| [Difede et al. (2022)] | VR head-mounted display (HMD) | PTSD treatment | 192 veterans (90% male) with treatment-resistant combat-related PTSD randomized to VRET (n = 97) or PE (n = 95) | “Wizard of Oz protocol.” Participants received two preparatory sessions followed by seven 90-minute weekly sessions, with 30-45 minutes of exposure and 30 minutes of processing discussion. At session 3, participants received either D-cycloserine or placebo | Both treatment groups improved CAPS scores (F (1,190) = 51.18, p < 0.001), but there we differences between groups (F(1,190) = 2.36, p = .126). Therapy-by-MDD interaction (F = 4.07, p = .045) suggested that VRE was more effective for depressed participants (CAPS mean difference = .51, 95% CI [1.17, 5.86], p = .004, effect size = 0.14) but PE was more effective for nondepressed participants (CAPS mean symptom difference = −8.87 [95% CI [−11.33, −6.40], p < .001, effect size = −0.44) | “Wizard of Oz” protocol: During VRET, patients verbally describe events of their traumatic memory in the first person to the therapist, who customizes the VR scene to match the patient’s memory. D-cycloserine (DCS) is a partial agonist at the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor. |

| Neurofeedback Training | ||||||

| [Nicholson et al. (2020)] | Neurofeedback Training | PTSD treatment | 36 civilians with PTSD (28% male) were randomized to experimental NFT (n = 18) or sham NFT (n = 18) and compared to healthy controls (n= 36). Military occupational trauma (n = 3), first responder occupational trauma (n = 2), and civilian physical/sexual abuse or neglect (n = 13) | Digitally-guided alpha-rhythm desynchronization neurofeedback measured from the parietal lobe vs sham neurofeedback. Minimum of 17 20-minute weekly NFT training sessions for 20 weeks | No significant difference in CAPS score reductions from pre- vs. post NFT training between the experimental and sham groups (F(1.42, 48.37) = 0.911, η2 = 0.026, ns). Only the experimental group showed significant CAPS-total scores from pre- to post-NFT (t(17) = 3.00, p < .008, dz = 0.71) and from pre-NFT to the 3-month follow-up (t(17) = 3.24, p < .005, dz = 0.77). Higher remission rates in experimental group vs sham group (61% vs 33%). Aberrant connectivity in large-scale brain networks trended towards normalization post-treatment | |

| [Leem et al. (2021)] | Neurofeedback Training | PTSD treatment | 22 adults with PTSD (10% male) randomized to NFT group (n = 10) or waitlist-control (n=9). Domestic violence trauma (n = 16), traffic accident (n = 2), school violence (n = 1) | Audio-based NFT training activation of parietal lobe alpha- and theta-rhythms and suppression of beta-rhythms. 16 50-minute sessions (30 minutes active and 20 minutes resting) over eight weeks | After eight weeks of treatment, scores on the Korean Version of the PTSD Checklist-5 (PCL-5-K) improved more in the NFT group than in the waitlist control group (NSRT group: 24.90 ± 13.13 vs. waitlist control group: 4.11 ± 9.03; p < 0.01), and this difference was maintained at one month follow-up. Measures of anxiety (BAI, p < .01), depression (BDI, p < .01), and quality of life (QOl-EQ-VAS, p <.01) were also significantly improved in the NFT group compared to waitlist controls at one-month follow-up. | |

| [Fruchtman-Steinbok et al. (2021)] | Neurofeedback Training | PTSD treatment | 59 adults with PTSD randomized to three groups: Trauma-script feedback interface (Trauma-NFT; n = 13), neutral feedback interface (Neutral-NFT; n = 14), and a waitlist control group of No-NF (n = 13) |

Trauma-oriented NFT protocol in which experimental group listening to an audio clip of a personal trauma-interview. Another group listened to neutral music. Down-regulation of amygdalar activity (AmygEFP) reduced the volume of the audio clip. 15 40-minute sessions over 13 weeks | Both NFT groups showed reductions in CAPS scores compared to controls (F(2,34) = 6.21, p = .005, η2 = 0.26), with a marginal difference between the NFT groups (p = .07). Relative to No-NF control, Trauma-NF showed the largest decrease in symptoms (−35.13%; p = .001), followed by Neutral-NF (−19.48%; p = .04). Both NFT groups also improved on anxiety (STAI), and only the Neutral-NFT group significantly improved on depression (BDI), where Trauma-NFT showed a marginal improvement. Neither experimental group significantly improved in emotional regulation or alexithymia. | EEG recording used a machine-learning based modeling of previous EEG sessions recorded in conjunction with fMRI, which allowed EEG-alone to be related to predicted decreases in amygdalar fMRI BOLD activity |

| [Rogel et al. (2020)] | Neurofeedback Training | PTSD treatment | 37 children (aged 6-13 years old, 65% male) with PTSD randomized to NFT group (n = 20) and treatment as usual control (n = 17). Chronic neglect (n = 33), impaired caregiver (n = 33), separation from primary caregiver (n =35), physical abuse, and domestic violence were most commonly reported traumas | Audio and visual NFT training inhibition of delta-, theta-, and beta- rhythms and the activation of each individual’s maximal amplitude alpha-rhythm in the parietal cortex vs. treatment as usual. 24 6-12 minute sessions of biweekly NFT over 12 weeks | After 12 weeks, fewer NFT participants met diagnostic criteria for PTSD compared to controls, as assessed by K-SADS (10/16 controls vs 4/16 NFT, p = .033). At one-month follow-up, this difference was no longer significant (7/14 controls vs 10/15 NFT, p = .362) | |

| du [Bois et al. (2021)] | Neurofeedback Training | PTSD treatment | 29 adults with PTSD randomized into three groups: Neurofeedback (n =1 0), Motor-imagery (n = 10), and control (n = 9) | Videogame-based NFT protocol training alpha-rhythm suppression over the parietal cortex vs motor imagery (MI) game training mu- and beta-rhythm modulation over the sensorimotor cortex. Six to seven 20-minute sessions | Only the NFT group showed significant reductions in PTSD symptom severity in four of the seven clinical measures: the PCL-5 (p = .005, d = 2.24), the PC-PTSD for DSM-5 (p = .005, d = 3.1), the Harvard Trauma questionnaire (p = .005, d = 2.41), and the 10-item CD-RISC (p = .041, d = −0.4). Significant differences between NFT and MI groups in their pre- and post-intervention differences in two of the seven clinical questionnaires (PCL-5 [p = .001, d = 2.22] and HTQ [p = .001, d = 2.19]). | Conducted outside of the clinical setting (in public buildings |

| Mobile Apps | ||||||

| [Pacella-LaBarbara et al. (2020)] | PTSD coach mobile app | PTSD treatment | 64 trauma-exposed patients in the emergency department assigned to PTSD Coach (n = 33) or treatment as usual (TAU; n = 31) | Patients used the PTSD coach app ad libitum for one month | At 1- and 3-month follow-ups, there were no significant PTSD symptom differences between groups, as assessed via the abbreviated 8-item PTSD checklist. Although, at 3-month follow-up, black participants assigned to the intervention group (n = 21) reported marginally lower PTSD symptoms (95% CI [−0.30, 37.77] and higher self-coping efficacy (95% CI [−58.20, −3.61]) according to a nine-item scale created by the authors. | |

| [Hensler et al. (2021/2022)] | Swedish version of PTSD coach mobile app | PTSD treatment |

179 adults in Sweden with trauma in the past two years assigned to have access to a Swedish version of PTSD coach (n = 89) or waitlist control (n = 90) | Participants were assessed twice daily with questions about self-reported health as well as app usage and use of strategies for 21 consecutive days | After 24 days, there were no significant differences in self-reported health between the two groups. A follow-up study using the same participant data revealed significant differences in posttraumatic stress in the group with access to the PTSD coach for three months (d = −0.45, 95% CI [−0.70, −0.20]), as assessed by the PCL-5. Participants with access to the app were also more likely to experience clinical improvements (χ²1,150) = 4.62; p = .03 (2(1, 150) = 4.62; p = .03) and less likely to meet diagnostic criteria for probable PTSD compared to waitlist controls (2(1, 150) = 7.74; p = .005). |

|

| [Kuhn et al. (2017)] | PTSD Coach mobile app | PTSD treatment | 120 trauma-exposed participants with elevated PCL-C scores asigned to PTSD coach access (n=60) or waitlist control (n=60) | Participants were assessed for PTSD symptom scores with PCL-C after three months of ad libitum use | After three months, participants with access to the app showed significant reductions in PCL-C scores compared to waitlist controls (F(1, 117) = 4.55, p = .035). Mean scores did not significantly differ after the waitlist controls received treatment (t(118) = 0.73, p = .466). The PTSD Coach group also showed significant reductions in depression symptoms (PHQ-8; F(1,117) = 8.34, p = .005). | |

| [Cox et al. (2019)] | Mobile app-based mindfulness program | PTSD treatment | 80 ICU patients discharged after being treated for cardiorespiratory failure, divided between mobile mindfulness (n=31), telephone mindfulness (n=31), or psychoeducation (n=18) | The patients were each allocated to a month-long treatment program; either mobile mindfulness, therapist-led telephone-based mindfulness, or psychoeducation. Patients were assessed with patient health questionnaire and Post Traumatic Stress Scale (PTSS) at 3-month follow-up. | At 3-month follow-up, clinically insignificant decreases in all groups on PTSS: mobile (−2.6, 95% CI[−6.3, 1.2]), telephone (−2.2, 95% CI [−5.6, 1.2]), education (−3.5, 95% CI [−8.0, 1.0]). | |

| [Elbogen et al. (2019)] | CALM mobile app | PTSD management | 112 dyads of veterans and their support person completed this study. Of the veteran participants, 90% were male with an average age of 36.52. | Participants were instructed to follow the novel CALM program for six months and had a mobile device to access apps supplementary to their program. Active control group participants received psychoeducational material and did visual memory training. | Both the experimental group (p < 0.001) and the active control group (p = 0.002) improved on PTSS. Among secondary outcomes, there was a larger decrease in anger over 6 months compared the control (B= −5.27, p = .008). Family/friends reported that veterans randomized to CALM engaged fewer maladaptive interpersonal behaviors (eg, aggression) over 6 months than the control (B = −2.08, p = .016). | CALM: Cognitive Applications for Life Management, TBI: Traumatic Brain Injury |

| [Niles et al. (2020)] | “Resolving Psychological Stress”(RePS) mobile app | PTSD management | 689 patients with PTSD symptoms in the United States (20% male) assigned to have personalized ABM (n = 234), non-personalized ABM (n = 219), or placebo (n = 236) | RePS mobile app trained attention bias by presenting participants with two words, where at least one was neutral, and one associated with threat. Both words were neutral in placebo condition, and in the personalized ABM, the threat word was chosen based on what the model predicted to be most threatening to the participant. Participants were instructed to use the app for 21 days. | After 21 days of training, all three groups showed reductions in PCL-5 scores from baseline (p < .001), but not at 5 week follow-up (p= .484). There were no significant difference in PCL-5 scores between the groups (p = .786) | |

| Van der [Meer et al. (2017)] | Smart Assessment on your Mobile (SAM) | PTSD and depression identification | 89 trauma-exposed participants in the Netherlands consisting of 88 police officers and 1 ambulance worker (75.3% male) | SAM was used to assess PTSD symptoms, general functioning, depression, etc. and involves a shortened, Dutch version of the PCL-5. Participants completed the SAM on average 5.6 days before completing in-person CAPS-5 interview | There was 77.5% agreement between the CAPS-5 and the PCL-5 in SAM. Also, participants with a clinician-rated PTSD diagnosis had significant higher scores on the PCL-5 (mean = 43.10, SD = 13.55) than participants without a PTSD diagnosis (mean = 25.75, SD = 11.01), (t = −6.43, p < .001) | |

| [Röhr et al. (2021)] | Sanadak mobile app | PTSD management | 133 trauma-exposed Syrian refugees residing in Germany aged 18-65 divided into an intervention group n = 65, and a control group n = 68. Participants were 61.7% male | Sanadak is a smartphone-based mobile app that provides CBT-based self-help in the Arabic language. Participants were allocated to either an intervention group that used the Sanadak app for four weeks or a control group that received psychoeducational reading material. |

After 4 weeks, no significant difference found between the intervention group using the Sanadak app (n = 65) and the psychoeducation control group (n = 68) on the PDS-5 (mean difference= –0.39, 95% CI [–3.24, 2.46], p = .79) | |

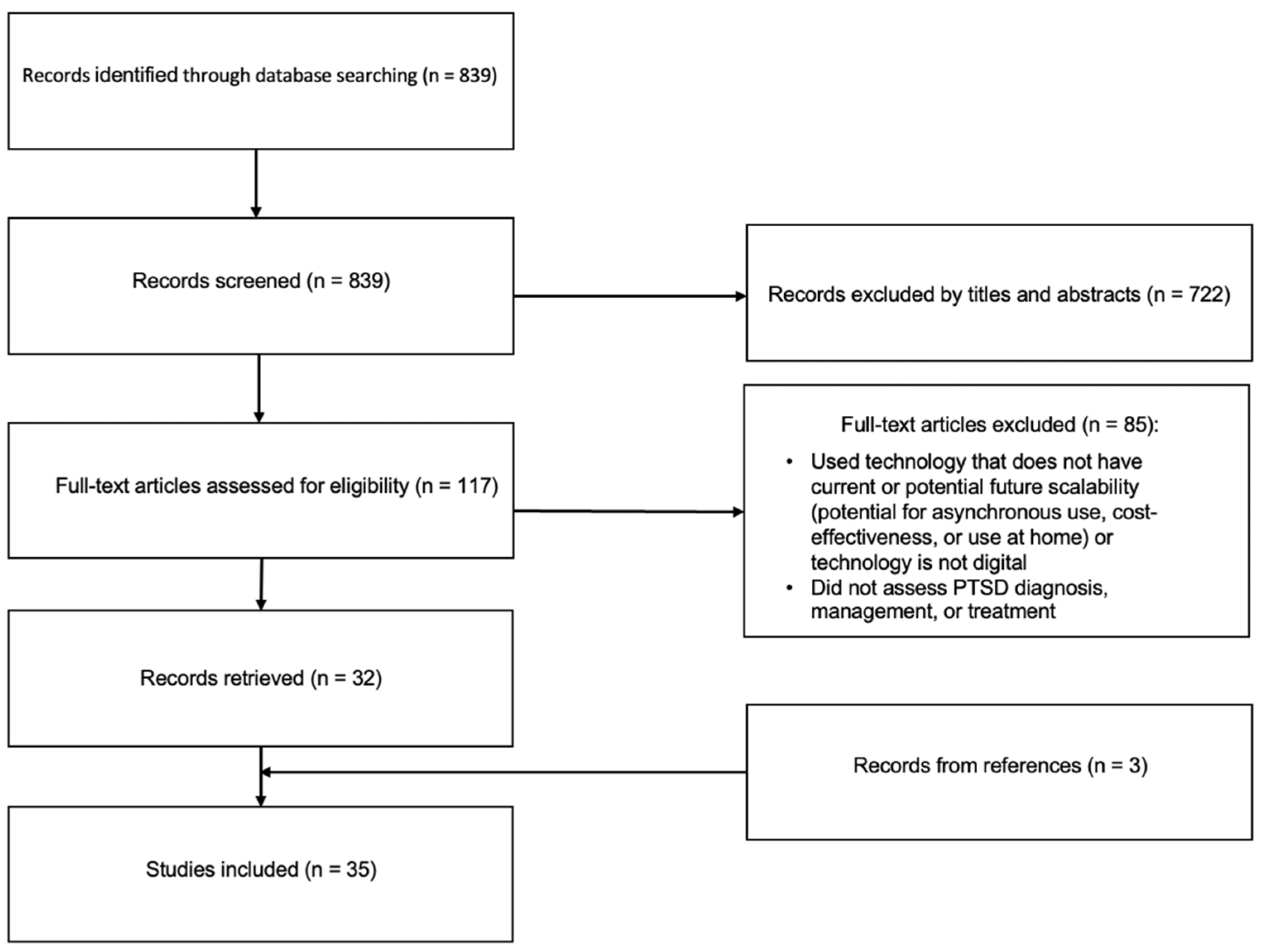

Methods

Results

Digital Tools for PTSD Diagnosis and Symptom Assessment

Digital Phenotyping

Wearables

Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Facial Feature Interpretation

Mobile Apps

Digital Tools for PTSD Treatment Augmentation

Immersive Technology (VR, AR, 3DMR)

Mobile Apps

Neurofeedback

Discussion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acierno, R., Jaffe, A. E., Gilmore, A. K., Birks, A., Denier, C., Muzzy, W.,... Tuerk, P. W. (2021). A randomized clinical trial of in-person vs. home-based telemedicine delivery of Prolonged Exposure for PTSD in military sexual trauma survivors. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 83, 102461. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5 Task Force. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.

- Andrilla, C. H. A., Patterson, D. G., Garberson, L. A., Coulthard, C., & Larson, E. H. (2018). Geographic variation in the supply of selected behavioral health providers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 54(6 Suppl 3), S199-S207. [CrossRef]

- Barnett, I., Torous, J., Staples, P., Sandoval, L., Keshavan, M., & Onnela, J. P. (2018). Relapse prediction in schizophrenia through digital phenotyping: A pilot study. Neuropsychopharmacology, 43(8), 1660-1666. [CrossRef]

- Beck, J. G., Palyo, S. A., Winer, E. H., Schwagler, B. E., & Ang, E. J. (2007). Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for PTSD symptoms after a road accident: An uncontrolled case series. Behavior Therapy, 38(1), 39–48. [CrossRef]

- Bedi, G., Carrillo, F., Cecchi, G. A., Fernández Slezak, D., Sigman, M., Mota, N. B.,... Kortholm, J. (2015). Automated analysis of free speech predicts psychosis onset in high-risk youths. NPJ Schizophrenia, 1, 15030. [CrossRef]

- Bisson, J. I., Roberts, N. P., Andrew, M., Cooper, R., & Lewis, C. (2013). Psychological therapies for chronic post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2013(12), CD003388. [CrossRef]

- Bisson, J. I., van Deursen, R., Hannigan, B., Kitchiner, N., Barawi, K., Jones, K.,... Humphreys, L. (2020). Randomized controlled trial of multi-modular motion-assisted memory desensitization and reconsolidation (3MDR) for male military veterans with treatment-resistant post-traumatic stress disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 142(2), 141-151. [CrossRef]

- Bourla, A., Mouchabac, S., El Hage, W., & Ferreri, F. (2018). e-PTSD: An overview on how new technologies can improve prediction and assessment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(sup1), 1424448. [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, A. S., Alday, E. A. P., Da Poian, G., Rad, A. B., Metzler, T. J., Neylan, T. C.,et al. (2021). Classification and prediction of post-trauma outcomes related to PTSD using circadian rhythm changes measured via wrist-worn research watch in a large longitudinal cohort. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, 25(8), 2866-2876. [CrossRef]

- Cox, C. E., Hough, C. L., Jones, D. M., Ungar, A., Reagan, W., Key, M. D., et al. (2019). Effects of mindfulness training programmes delivered by a self-directed mobile app and by telephone compared with an education programme for survivors of critical illness: A pilot randomised clinical trial. Thorax, 74(1), 33-42. [CrossRef]

- Cully, J. A., Jameson, J. P., Phillips, L. L., Kunik, M. E., & Fortney, J. C. (2010). Use of psychotherapy by rural and urban veterans. Journal of Rural Health, 26(3), 225-233. [CrossRef]

- de Hond, A. A. H., Steyerberg, E. W., & van Calster, B. (2022). Interpreting area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. The Lancet Digital Health, 4(12), e853-e855. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, P. B. F., Dornelles, T. M., Gosmann, N. P., & Camozzato, A. (2023). Efficacy of telemedicine interventions for depression and anxiety in older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 38(5), e5920. [CrossRef]

- Department of Veterans Affairs & Department of Defense. (2023). VA/DOD Practice Guideline for Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Disorder (Version 3.0). U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs & U.S. Department of Defense.

- Di Carlo, F., Sociali, A., Picutti, E., Pettorruso, M., Vellante, F., Verrastro, V.,... Martinotti, G. (2021). Telepsychiatry and other cutting-edge technologies in COVID-19 pandemic: Bridging the distance in mental health assistance. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 75(1), e13716. [CrossRef]

- Difede, J., Rothbaum, B. O., Rizzo, A. A., Wyka, K., Spielman, L., Reist, C.,... D., Rizzo, A. A. (2022). Enhancing exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): A comparison of virtual reality graded exposure with traditional imaginal exposure in a controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 90(1), 79-93. [CrossRef]

- du Bois, N., Bigirimana, A. D., Korik, A., Kéthina, L. G., Rutembesa, E., Mutabaruka, J., Mutesa, L., Prasad, G., Jansen, S., & Coyle, D. H. (2021). Neurofeedback with low-cost, wearable electroencephalography (EEG) reduces symptoms in chronic Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of affective disorders, 295, 1319–1334. [CrossRef]

- Elbogen, E. B., Dennis, P. A., Van Voorhees, E. E., Blakey, S. M., Johnson, J. L., Johnson, S. C., et al. (2019). Cognitive Rehabilitation With Mobile Technology and Social Support for Veterans With TBI and PTSD: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 34(1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Eshuis, L. V., van Gelderen, M. J., van Zuiden, M., Nijdam, M. J., Vermetten, E., Olff, M., et al. (2021). Efficacy of immersive PTSD treatments: A systematic review of virtual and augmented reality exposure therapy and a meta-analysis of virtual reality exposure therapy. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 143, 516-527. [CrossRef]

- Foa, E. B., Chrestman, K. R., & Gilboa-Schechtman, E. (2008). Prolonged Exposure Therapy for Adolescents with PTSD Therapist Guide: Emotional Processing of Traumatic Experiences. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Forbes, D., Pedlar, D., Adler, A. B., Benner, C., Bryant, R., Busuttil, W., et al. (2019). Treatment of military-related post-traumatic stress disorder: Challenges, innovations, and the way forward. International Review of Psychiatry, 31(1), 95-110. [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, F., Santangelo, P., Ebner-Priemer, U., Hill, H., Neubauer, A. B., Rausch, S., et al. (2020). Life within a limited radius: Investigating activity space in women with a history of child abuse using global positioning system tracking. PLoS One, 15(5), e0232666. [CrossRef]

- Fruchtman-Steinbok, T., Keynan, J. N., Cohen, A., Jaljuli, I., Mermelstein, S., Drori, G., Routledge, E., Krasnoshtein, M., Playle, R., Linden, D. E. J., & Hendler, T. (2021). Amygdala electrical-finger-print (AmygEFP) NeuroFeedback guided by individually-tailored Trauma script for post-traumatic stress disorder: Proof-of-concept. NeuroImage. Clinical, 32, 102859. [CrossRef]

- Gavrilescu, M., & Vizireanu, N. (2019). Predicting Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Levels from Videos Using the Facial Action Coding System. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 19(17), 3693. [CrossRef]

- Gerin, M. I., Fichtenholtz, H., Roy, A., Walsh, C. J., Krystal, J. H., Southwick, S., & Hampson, M. (2016). Real-Time fMRI Neurofeedback with War Veterans with Chronic PTSD: A Feasibility Study. Frontiers in psychiatry, 7, 111. [CrossRef]

- Giovanetti, A. K., Punt, S. E. W., Nelson, E. L., & Ilardi, S. S. (2022). Teletherapy Versus In-Person Psychotherapy for Depression: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health, 28(8), 1077-1089. [CrossRef]

- Goreis, A., Felnhofer, A., Kafka, J. X., Probst, T., & Kothgassner, O. D. (2020). Efficacy of Self-Management Smartphone-Based Apps for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 14, 3. [CrossRef]

- Grasser, L. R., Saad, B., Bazzi, C., Wanna, C., Suhaiban, H. A., Mammo, D., et al. (2022). Skin conductance response to trauma interview as a candidate biomarker of trauma and related psychopathology in youth resettled as refugees. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2083375. [CrossRef]

- He, Q., Veldkamp, B. P., Glas, C. A., & de Vries, T. (2017). Automated Assessment of Patients’ Self-Narratives for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Screening Using Natural Language Processing and Text Mining. Assessment, 24(2), 157–172. [CrossRef]

- He, Q., Veldkamp, B. P., Glas, C. A. W., & van den Berg, S. M. (2019). Combining Text Mining of Long Constructed Responses and Item-Based Measures: A Hybrid Test Design to Screen for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2358. [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, L., de Kleine, R. A., Broekman, T. G., Hendriks, G. J., & van Minnen, A. (2018). Intensive prolonged exposure therapy for chronic PTSD patients following multiple trauma and multiple treatment attempts. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1425574. [CrossRef]

- Hensler, I., Sveen, J., Cernvall, M., & Arnberg, F. K. (2021). Ecological momentary assessment of self-rated health, daily strategies and self-management app use among trauma-exposed adults. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1920204. [CrossRef]

- Hensler, I., Sveen, J., Cernvall, M., & Arnberg, F. K. (2022). Efficacy, Benefits, and Harms of a Self-management App in a Swedish Trauma-Exposed Community Sample (PTSD Coach): Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(3), e31419. [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, A. S., Roesmann, K., Planert, J., Machulska, A., Otto, E., & Klucken, T. (2022). Self-guided virtual reality therapy for social anxiety disorder: A study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 23(1), 395. [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, R., Michopoulos, V., Winters, S., Rothbaum, A. O., Rothbaum, B. O., Ressler, K. J., et al. (2017). Mobile assessment of heightened skin conductance in posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 34(6), 502-507. [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, R., van Rooij, S. J., Michopoulos, V., Schultebraucks, K., Winters, S., Maples-Keller, J., et al. (2019). Increased Skin Conductance Response in the Immediate Aftermath of Trauma Predicts PTSD Risk. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks), 3, 2470547019844441. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M., Ahern, D. K., & Suzuki, J. (2020). Digital Phenotyping to Enhance Substance Use Treatment During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JMIR Mental Health, 7(10), e21814. [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, A., Papastavrou, E., Avraamides, M. N., & Charalambous, A. (2020). Virtual Reality and Symptoms Management of Anxiety, Depression, Fatigue, and Pain: A Systematic Review. SAGE Open Nursing, 6, 2377960820936163. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, N. C., Weingarden, H., & Wilhelm, S. (2019). Digital biomarkers of mood disorders and symptom change. NPJ Digital Medicine, 2, 3. [CrossRef]

- [name deleted to maintain the integrity of the review process]. (2021). Real-life contextualization of exposure therapy using augmented reality: A pilot clinical trial of a novel treatment method. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 33(4), 220-231. [CrossRef]

- [name deleted to maintain the integrity of the review process]. (2023). Augmented Reality Might Be the Future of Exposure Therapy for PTSD. Biological Psychiatry, 93(9, Supplement), S246. [CrossRef]

- Jericho, B., Luo, A., & Berle, D. (2022). Trauma-focused psychotherapies for post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 145(2), 132-155. [CrossRef]

- Jones, C., Miguel-Cruz, A., Smith-MacDonald, L., Cruikshank, E., Baghoori, D., Chohan, A. K., et al. (2020). Virtual Trauma-Focused Therapy for Military Members, Veterans, and Public Safety Personnel With Posttraumatic Stress Injury: Systematic Scoping Review. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 8(9), e22079. [CrossRef]

- Kamath, J., Leon Barriera, R., Jain, N., Keisari, E., & Wang, B. (2022). Digital phenotyping in depression diagnostics: Integrating psychiatric and engineering perspectives. World journal of psychiatry, 12(3), 393–409. [CrossRef]

- Kazdin, A. E., & Blase, S. L. (2011). Interventions and models of their delivery to reduce the burden of mental illness: Reply to commentaries. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(5), 507-510. [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 617-627. [CrossRef]

- Keynejad, R. C., Dua, T., Barbui, C., & Thornicroft, G. (2018). WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) Intervention Guide: A systematic review of evidence from low and middle-income countries. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 21(1), 30-34. [CrossRef]

- Kilpatrick, D. G., Resnick, H. S., Milanak, M. E., Miller, M. W., Keyes, K. M., & Friedman, M. J. (2013). National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(5), 537-547. [CrossRef]

- Kleiman, E. M., Turner, B. J., Fedor, S., Beale, E. E., Picard, R. W., Huffman, J. C., & Nock, M. K. (2018). Digital phenotyping of suicidal thoughts. Depression and anxiety, 35(7), 601–608. [CrossRef]

- Koenen, K. C., Ratanatharathorn, A., Ng, L., McLaughlin, K. A., Bromet, E. J., Stein, D. J.,... & Kessler, R. C. (2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the World Mental Health Surveys. Psychological Medicine, 47(13), 2260-2274. [CrossRef]

- Koppe, G., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., & Durstewitz, D. (2021). Deep learning for small and big data in psychiatry. Neuropsychopharmacology, 46(1), 176-190. [CrossRef]

- Kothgassner, O. D., Goreis, A., Kafka, J. X., Van Eickels, R. L., Plener, P. L., & Felnhofer, A. (2019). Virtual reality exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): A meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1654782. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, E., Greene, C., Hoffman, J., Nguyen, T., Wald, L., Schmidt, J.,... & Ruzek, J. (2014). Preliminary evaluation of PTSD Coach, a smartphone app for post-traumatic stress symptoms. Military Medicine, 179(1), 12-18. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, E., Kanuri, N., Hoffman, J. E., Garvert, D. W., Ruzek, J. I., & Taylor, C. B. (2017). A randomized controlled trial of a smartphone app for posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(3), 267-273. [CrossRef]

- Le Glaz, A., Haralambous, Y., Kim-Dufor, D. H., Lenca, P., Billot, R., Ryan, T. C.,... & Saporta, G. (2021). Machine learning and natural language processing in mental health: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(5), e15708. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. J., Schnitzlein, C. W., Wolf, J. P., Vythilingam, M., Rasmusson, A. M., & Hoge, C. W. (2016). Psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: Systematic review and meta-analyses to determine first-line treatments. Depression and Anxiety, 33(9), 792-806. [CrossRef]

- Leem, J., Cheong, M. J., Lee, H., Cho, E., Lee, S. Y., Kim, G. W., & Kang, H. W. (2021). Effectiveness, Cost-Utility, and Safety of Neurofeedback Self-Regulating Training in Patients with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 9(10), 1351. [CrossRef]

- Lekkas, D., & Jacobson, N. C. (2021). Using artificial intelligence and longitudinal location data to differentiate persons who develop posttraumatic stress disorder following childhood trauma. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 10303. [CrossRef]

- Loucks, L., Yasinski, C., Norrholm, S. D., Maples-Keller, J., Post, L., Zwiebach, L.,... & Rothbaum, B. O. (2019). You can do that?!: Feasibility of virtual reality exposure therapy in the treatment of PTSD due to military sexual trauma. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 61, 55–63. [CrossRef]

- Martin, A., Naunton, M., Kosari, S., Peterson, G., Thomas, J., & Christenson, J. K. (2021). Treatment guidelines for PTSD: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(18), 4175. [CrossRef]

- Marmar, C. R., Brown, A. D., Qian, M., Laska, E., Siegel, C., Li, M., Abu-Amara, D., Tsiartas, A., Richey, C., Smith, J., Knoth, B., & Vergyri, D. (2019). Speech-based markers for posttraumatic stress disorder in US veterans. Depression and anxiety, 36(7), 607–616. [CrossRef]

- Marzbani, H., Marateb, H. R., & Mansourian, M. (2016). Neurofeedback: A Comprehensive Review on System Design, Methodology and Clinical Applications. Basic and clinical neuroscience, 7(2), 143–158. [CrossRef]

- McLay, R. N., Baird, A., Webb-Murphy, J., Deal, W., Tran, L., Anson, H.,... & Johnston, S. (2017). A randomized, head-to-head study of virtual reality exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 20(4), 218-224. [CrossRef]

- Meyerbröker, K., & Morina, N. (2021). The use of virtual reality in assessment and treatment of anxiety and related disorders. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 28(3), 466–476. [CrossRef]

- Morland, L. A., Wells, S. Y., Glassman, L. H., Greene, C. J., Hoffman, J. E., & Rosen, C. S. (2020). Advances in PTSD treatment delivery: Review of findings and clinical considerations for the use of telehealth interventions for PTSD. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry, 7(3), 221–241. [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, A. A., Ros, T., Densmore, M., Frewen, P. A., Neufeld, R. W. J., Théberge, J., Jetly, R., & Lanius, R. A. (2020). A randomized, controlled trial of alpha-rhythm EEG neurofeedback in posttraumatic stress disorder: A preliminary investigation showing evidence of decreased PTSD symptoms and restored default mode and salience network connectivity using fMRI. NeuroImage. Clinical, 28, 102490. [CrossRef]

- Niles, A. N., Woolley, J. D., Tripp, P., Pesquita, A., Vinogradov, S., Neylan, T. C.,... & Rauch, S. A. (2020). Randomized controlled trial testing mobile-based attention-bias modification for posttraumatic stress using personalized word stimuli. Clinical Psychological Science, 8(4), 756-772. [CrossRef]

- Orr, S. P., Metzger, L. J., & Pitman, R. K. (2002). Psychophysiology of post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 25(2), 271-293. [CrossRef]

- Pacella-LaBarbara, M. L., Suffoletto, B. P., Kuhn, E., Germain, A., Jaramillo, S., Repine, M.,... & Simon, N. M. (2020). A pilot randomized controlled trial of the PTSD Coach app following motor vehicle crash-related injury. Academic Emergency Medicine, 27(11), 1126-1139. [CrossRef]

- Place, S., Blanch-Hartigan, D., Rubin, C., Gorrostieta, C., Mead, C., Kane, J.,... & Fulcher, J. A. (2017). Behavioral indicators on a mobile sensing platform predict clinically validated psychiatric symptoms of mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(3), e75. [CrossRef]

- Premkumar, P., Heym, N., Brown, D. J., Battersby, S., Sumich, A., Huntington, B., Daly, R., & Zysk, E. (2021). The effectiveness of self-guided virtual-reality exposure therapy for public-speaking anxiety. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 694610. [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Lima, L. F., Waikamp, V., Antonelli-Salgado, T., Passos, I. C., & Freitas, L. H. M. (2020). The use of machine learning techniques in trauma-related disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 121, 159–172. [CrossRef]

- Reinertsen, E., Nemati, S., Vest, A. N., Vaccarino, V., Lampert, R., Shah, A. J.,... & Clifford, G. D. (2017). Heart rate-based window segmentation improves accuracy of classifying posttraumatic stress disorder using heart rate variability measures. Physiological Measurement, 38(6), 1061-1076. [CrossRef]

- Reinertsen, E., & Clifford, G. D. (2018). A review of physiological and behavioral monitoring with digital sensors for neuropsychiatric illnesses. Physiological Measurement, 39(5), 05TR01. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Villa, E., Rauseo-Ricupero, N., Camacho, E., Wisniewski, H., Keshavan, M., & Torous, J. (2020). The digital clinic: Implementing technology and augmenting care for mental health. General Hospital Psychiatry, 66, 59-66. [CrossRef]

- Rogel, A., Loomis, A. M., Hamlin, E., Hodgdon, H., Spinazzola, J., & van der Kolk, B. (2020). The impact of neurofeedback training on children with developmental trauma: A randomized controlled study. Psychological trauma : theory, research, practice and policy, 12(8), 918–929. [CrossRef]

- Röhr, S., Jung, F. U., Pabst, A., Grochtdreis, T., Dams, J., Nagl, M.,... & Hinkelmann, L. (2021). A Self-Help App for Syrian Refugees With Posttraumatic Stress (Sanadak): Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 9(1), e24807. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M., McDonald, A. D., & Sasangohar, F. (2022). Posttraumatic stress disorder hyperarousal event detection using smartwatch physiological and activity data. PLOS ONE, 17(5), e0267749. [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, L. R., Torous, J., & Keshavan, M. S. (2017). Smartphones for smarter care? Self-management in schizophrenia. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(8), 725-728. [CrossRef]

- Satiani, A., Niedermier, J., Satiani, B., & Svendsen, D. P. (2018). Projected workforce of psychiatrists in the United States: A population analysis. Psychiatric Services, 69(6), 710-713. [CrossRef]

- Sawalha, J., Yousefnezhad, M., Shah, Z., Brown, M. R. G., Greenshaw, A. J., & Greiner, R. (2022). Detecting Presence of PTSD Using Sentiment Analysis From Text Data. Frontiers in psychiatry, 12, 811392. [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M., Qassem, M., & Kyriacou, P. A. (2021). Wearable, environmental, and smartphone-based passive sensing for mental health monitoring. Frontiers in Digital Health, 3, 662811. [CrossRef]

- Slater, M., & Sanchez-Vives, M. V. (2016). Enhancing our lives with immersive virtual reality. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 3. [CrossRef]

- Torous, J., Bucci, S., Bell, I. H., Kessing, L. V., Faurholdt-Jepsen, M., Whelan, P.,... & Firth, J. (2021). The growing field of digital psychiatry: Current evidence and the future of apps, social media, chatbots, and virtual reality. World Psychiatry, 20(3), 318-335. [CrossRef]

- Torous, J., Onnela, J. P., & Keshavan, M. (2017). New dimensions and new tools to realize the potential of RDoC: digital phenotyping via smartphones and connected devices. Translational psychiatry, 7(3), e1053. [CrossRef]

- Tsanas, A., Woodward, E., & Ehlers, A. (2020). Objective characterization of activity, sleep, and circadian rhythm patterns using a wrist-worn actigraphy sensor: Insights into posttraumatic stress disorder. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 8(4), e14306. [CrossRef]

- van der Meer, C. A. I., Bakker, A., Schrieken, B. A. L., Hoofwijk, M. C., & Olff, M. (2017). Screening for trauma-related symptoms via a smartphone app: The validity of Smart Assessment on your Mobile in referred police officers. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 26(3), e1579. [CrossRef]

- van Gelderen, M. J., Nijdam, M. J., Haagen, J. F. G., & Vermetten, E. (2020). Interactive motion-assisted exposure therapy for veterans with treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 89(4), 215-227. [CrossRef]

- Watkins, L. E., Sprang, K. R., & Rothbaum, B. O. (2018). Treating PTSD: A review of evidence-based psychotherapy interventions. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 12, 258. [CrossRef]

- Watts, B. V., Schnurr, P. P., Mayo, L., Young-Xu, Y., Weeks, W. B., & Friedman, M. J. (2013). Meta-analysis of the efficacy of treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(6), e541-e550. [CrossRef]

- Wickersham, A., Petrides, P. M., Williamson, V., & Leightley, D. (2019). Efficacy of mobile application interventions for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. Digital health, 5, 2055207619842986. [CrossRef]

- Wiltshire, C. N., Wanna, C. P., Stenson, A. F., Minton, S. T., Reda, M. H., Davie, W. M., et al. (2022). Associations between children’s trauma-related sequelae and skin conductance captured through mobile technology. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 150, 104036. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., Mao, K., Dennett, L., Zhang, Y., & Chen, J. (2023). Systematic review of machine learning in PTSD studies for automated diagnosis evaluation. npj Mental Health Research, 2, 16. [CrossRef]

- Zoellner, L. A., Feeny, N. C., Bittinger, J. N., Bedard-Gilligan, M. A., Slagle, D. M., Post, L. M., et al. (2011). Teaching Trauma-Focused Exposure Therapy for PTSD: Critical Clinical Lessons for Novice Exposure Therapists. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 3(3), 300-308. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).