Submitted:

16 September 2024

Posted:

17 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. General Analysis

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kauzmann, W. Some Factors in the Interpretation of Protein Denaturation. In Advances in Protein Chemistry; Elsevier, 1959; Volume 14, pp. 1–63. ISBN 978-0-12-034214-3.

- Dill, K.A. Dominant Forces in Protein Folding. Biochemistry 1990, 29, 7133–7155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokzijl, W.; Engberts, J.B.F.N. Hydrophobic Effects. Opinions and Facts. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English 1993, 32, 1545–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southall, N.T.; Dill, K.A.; Haymet, A.D.J. A View of the Hydrophobic Effect. J. Phys. Chem. B 2002, 106, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, P. Water as an Active Constituent in Cell Biology. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 74–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumi, T.; Imamura, H. Water-mediated Interactions Destabilize Proteins. Protein Science 2021, 30, 2132–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, K.P.; Privalov, P.L.; Gill, S.J. Common Features of Protein Unfolding and Dissolution of Hydrophobic Compounds. Science 1990, 247, 559–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzfeld, J. Understanding Hydrophobic Behavior. Science 1991, 253, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, N. Does Hydrophobic Hydration Destabilize Protein Native Structures? Trends in Biochemical Sciences 1992, 17, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oobatake, M.; Ooi, T. Hydration and Heat Stability Effects on Protein Unfolding. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 1993, 59, 237–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhatadze, G.I.; Privalov, P.L. Energetics of Protein Structure. In Advances in Protein Chemistry; Elsevier, 1995; Vol. 47, pp. 307–425 ISBN 978-0-12-034247-1.

- Smith, P.E.; Van Gunsteren, W.F. When Are Free Energy Components Meaningful? J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 13735–13740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, A.E.; Van Gunsteren, W.F. Decomposition of the Free Energy of a System in Terms of Specific Interactions. Journal of Molecular Biology 1994, 240, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boresch, S.; Karplus, M. The Meaning of Component Analysis: Decomposition of the Free Energy in Terms of Specific Interactions. Journal of Molecular Biology 1995, 254, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.; Richards, F.M. The Interpretation of Protein Structures: Estimation of Static Accessibility. Journal of Molecular Biology 1971, 55, 379-IN4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, F.M.; Lim, W.A. An Analysis of Packing in the Protein Folding Problem. Quart. Rev. Biophys. 1993, 26, 423–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gekko, Kunihiko.; Noguchi, Hajime. Compressibility of Globular Proteins in Water at 25.Degree.C. J. Phys. Chem. 1979, 83, 2706–2714. [CrossRef]

- Kharakoz, D.P. Protein Compressibility, Dynamics, and Pressure. Biophysical Journal 2000, 79, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrödinger, E.; Penrose, R. What Is Life?: With Mind and Matter and Autobiographical Sketches; 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press, 1992; ISBN 978-0-521-42708-1.

- Liquori, A.M. The Stereochemical Code and the Logic of a Protein Molecule. Quart. Rev. Biophys. 1969, 2, 65–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozaki, Y.; Tanford, C. The Solubility of Amino Acids and Two Glycine Peptides in Aqueous Ethanol and Dioxane Solutions. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1971, 246, 2211–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodaran, S.; Song, K.B. The Role of Solvent Polarity in the Free Energy of Transfer of Amino Acid Side Chains from Water to Organic Solvents. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1986, 261, 7220–7222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew Karplus, P. Hydrophobicity Regained. Protein Science 1997, 6, 1302–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.; Janin, J.; Lesk, A.M.; Chothia, C. Interior and Surface of Monomeric Proteins. Journal of Molecular Biology 1987, 196, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harpaz, Y.; Gerstein, M.; Chothia, C. Volume Changes on Protein Folding. Structure 1994, 2, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlino, A.; Pontillo, N.; Graziano, G. A Driving Force for Polypeptide and Protein Collapse. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dill, K.A. Additivity Principles in Biochemistry. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1997, 272, 701–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dill, K.A. Polymer Principles and Protein Folding. Protein Science 1999, 8, 1166–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Naim, A. Solvation Thermodynamics; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1987; ISBN 978-1-4757-6552-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B. A Procedure for Calculating Thermodynamic Functions of Cavity Formation from the Pure Solvent Simulation Data. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1985, 83, 2421–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohorille, A.; Pratt, L.R. Cavities in Molecular Liquids and the Theory of Hydrophobic Solubilities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 5066–5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasi, J.; Persico, M. Molecular Interactions in Solution: An Overview of Methods Based on Continuous Distributions of the Solvent. Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 2027–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, G. Scaled Particle Theory Study of the Length Scale Dependence of Cavity Thermodynamics in Different Liquids. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 11421–11426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, G. Dimerization Thermodynamics of Large Hydrophobic Plates: A Scaled Particle Theory Study. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 11232–11239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuarrie, D.A. Statistical Mechanics; Harper’s chemistry series; Harper & Row: New York, 1976; ISBN 978-0-06-044366-5.

- Graziano, G. Contrasting the Hydration Thermodynamics of Methane and Methanol. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 21418–21430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bologna, A.; Graziano, G. Remarks on the Hydration Entropy of Polar and Nonpolar Species. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2023, 391, 123437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soper, A.K.; Finney, J.L. Hydration of Methanol in Aqueous Solution. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 71, 4346–4349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan, P.; Aldiwan, N.; Soper, A.K.; Creek, J.L.; Koh, C.A. Decreased Structure on Dissolving Methane in Water. Chemical Physics Letters 2005, 415, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, G. Structural Order in the Hydration Shell of Nonpolar Groups versus That in Bulk Water. ChemPhysChem 2024, 25, e202400102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graziano, G. The Gibbs Energy Cost of Cavity Creation Depends on Geometry. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2015, 211, 1047–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierotti, R.A. A Scaled Particle Theory of Aqueous and Nonaqueous Solutions. Chem. Rev. 1976, 76, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallqvist, A.; Berne, B.J. Molecular Dynamics Study of the Dependence of Water Solvation Free Energy on Solute Curvature and Surface Area. J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 2885–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.J.; Varilly, P.; Chandler, D.; Garde, S. Quantifying Density Fluctuations in Volumes of All Shapes and Sizes Using Indirect Umbrella Sampling. J Stat Phys 2011, 145, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosso, G.C.; Caravati, S.; Rotskoff, G.; Vaikuntanathan, S.; Hassanali, A. On the Role of Nonspherical Cavities in Short Length-Scale Density Fluctuations in Water. J. Phys. Chem. A 2017, 121, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royer, C.A. Revisiting Volume Changes in Pressure-Induced Protein Unfolding. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology 2002, 1595, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalikian, T.V. Volumetric Properties of Proteins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2003, 32, 207–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.R.; Makhatadze, G.I. Molecular Determinant of the Effects of Hydrostatic Pressure on Protein Folding Stability. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 14561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graziano, G. On the Molecular Origin of Cold Denaturation of Globular Proteins. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 14245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, G. On the Mechanism of Cold Denaturation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 21755–21767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pica, A.; Graziano, G. Shedding Light on the Extra Thermal Stability of Thermophilic Proteins. Biopolymers 2016, 105, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liquori, A.M.; Sadun, C. Close Packing of Amino Acid Residues in Globular Proteins: Specific Volume and Site Binding of Water Molecules. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 1981, 3, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head-Gordon, T.; Hura, G. Water Structure from Scattering Experiments and Simulation. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 2651–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dill, K.A.; Chan, H.S. From Levinthal to Pathways to Funnels. Nat Struct Mol Biol 1997, 4, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolynes, P.G. Evolution, Energy Landscapes and the Paradoxes of Protein Folding. Biochimie 2015, 119, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxa, M.C.; Haddadian, E.J.; Jumper, J.M.; Freed, K.F.; Sosnick, T.R. Loss of Conformational Entropy in Protein Folding Calculated Using Realistic Ensembles and Its Implications for NMR-Based Calculations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014, 111, 15396–15401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, H.; Porter, L.L.; Rose, G.D. Counting Peptide-water Hydrogen Bonds in Unfolded Proteins. Protein Science 2011, 20, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, G.D. Reframing the Protein Folding Problem: Entropy as Organizer. Biochemistry 2021, 60, 3753–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, G.D. Protein Folding - Seeing Is Deceiving. Protein Science 2021, 30, 1606–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harano, Y.; Kinoshita, M. Translational-Entropy Gain of Solvent upon Protein Folding. Biophysical Journal 2005, 89, 2701–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, M. A New Theoretical Approach to Biological Self-Assembly. Biophys Rev 2013, 5, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita, M. Importance of Translational Entropy of Water in Biological Self-Assembly Processes like Protein Folding. IJMS 2009, 10, 1064–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, Y.; Harano, Y. Does Water Drive Protein Folding? Chemical Physics Letters 2013, 581, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamo, F.; Ishizuka, R.; Matubayasi, N. Correlation Analysis for Heat Denaturation of Trp-cage Miniprotein with Explicit Solvent. Protein Science 2016, 25, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, Y.; Yamamori, Y.; Matubayasi, N. Probabilistic Analysis for Identifying the Driving Force of Protein Folding. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2018, 148, 125101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

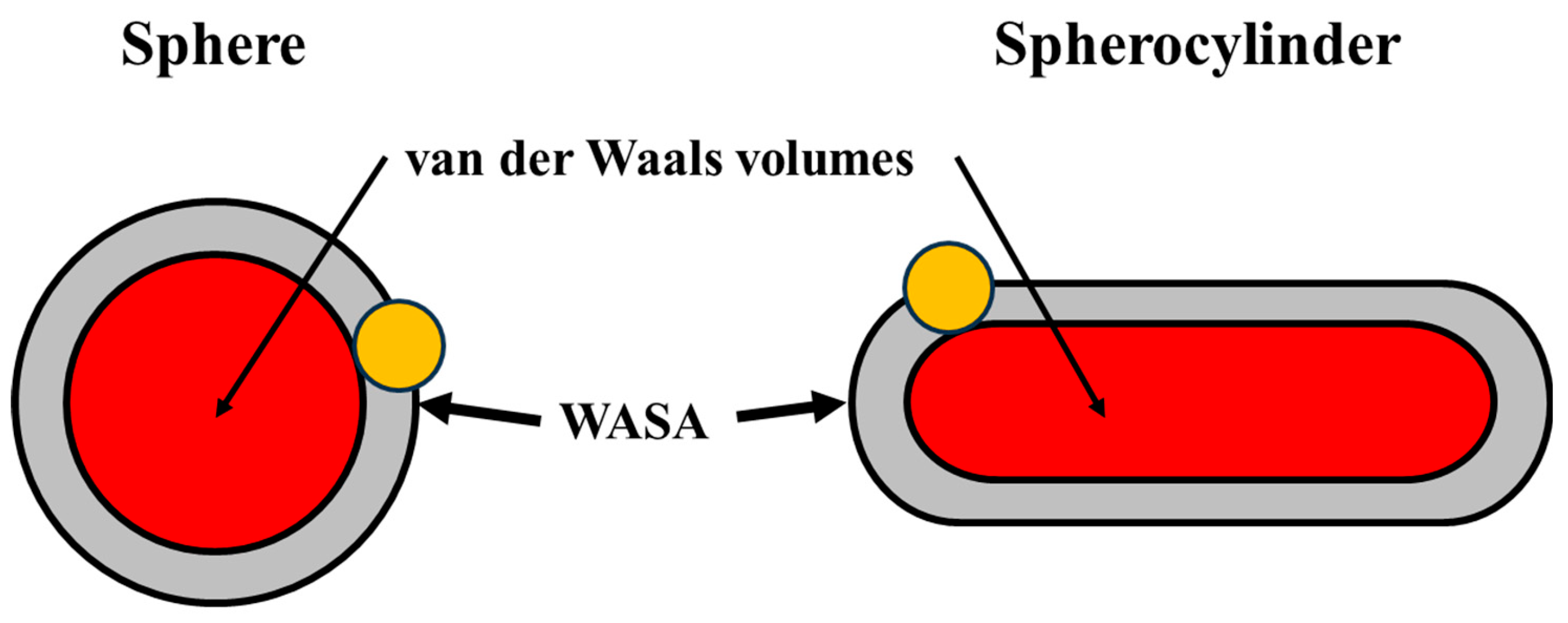

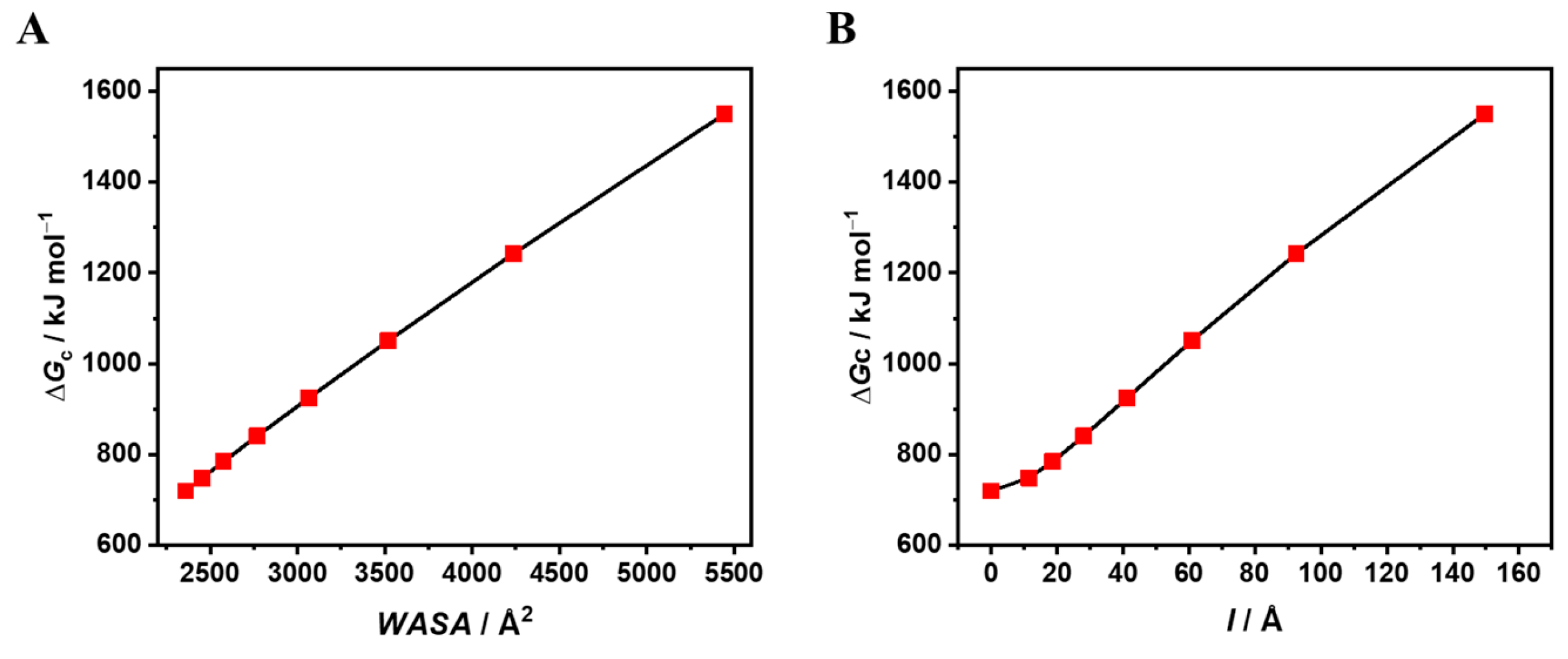

|

a Å |

l Å |

VvdW Å3 |

WASA Å2 |

ΔGc kJ mol-1 |

ΔGc/WASA J mol-1 Å-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12.3 | / | 7790 | 2359 | 719.8 | 305.1 |

| 10.0 | 11.46 | 7790 | 2454 | 748.6 | 305.1 |

| 9.0 | 18.61 | 7790 | 2575 | 784.6 | 304.7 |

| 8.0 | 28.07 | 7790 | 2768 | 840.7 | 303.7 |

| 7.0 | 41.27 | 7790 | 3065 | 925.2 | 301.9 |

| 6.0 | 60.88 | 7790 | 3519 | 1050.9 | 298.6 |

| 5.0 | 92.51 | 7790 | 4235 | 1242.2 | 293.3 |

| 4.0 | 149.65 | 7790 | 5444 | 1550.1 | 284.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).