1. Introduction

Phosphatidylserine (PS) regulates the functional state of key membrane proteins[

1], demonstrating significant benefits in neuronal repair, cognitive enhancement[

2], treatment of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder[

3], depression[

4], and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease[

5]. It has important potential applications in the pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetic industries[

6,

7]. However, the low total content of PS in nature and the difficulty of extraction make it expensive and limit its further application. A compelling solution involves the synthesis of PS through the enzymatic action of phospholipase D (PLD, EC3.1.4.4) on phosphatidylcholine (PC) and L-serine, characterized by readily available raw materials, mild reaction conditions, eco-friendly practices, and few by-products[

8,

9,

10].

The PLD catalyzed transphosphatidylation is a bi-substrate enzymatic reaction. Phospholipid substrates, such as PC, are insoluble in the aqueous phase, while the second substrate, such as L-serine, is insoluble in the organic phase[

10]. Consequently, the reaction system usually comprises a biphasic mixture consisting of an organic phase that is immiscible in water (e.g., ether, ethyl acetate, etc.) and an aqueous phase. In this system, PC dissolves in the organic phase, while PLD and L-serine are present in the aqueous phase, with PS synthesis occurring at the liquid-liquid interface. Prolonged exposure of free PLD to organic solvents compromises its structural integrity, leading to protein denaturation and disassembly. Since PLD is insoluble in the organic phase, it often aggregates in substantial quantities, diminishing enzyme utilization efficiency. The interphase mass transfer resistance is notable, reducing the contact area between the enzyme and substrates, which results in suboptimal efficiency[

11,

12]. Additionally, recovering free PLD enzymes is challenging. These drawbacks make free PLD ill-suited for large-scale PS production. Enzyme immobilization emerges as an effective strategy to address these issues. Anchoring the enzyme to a suitable carrier enlarges the interaction surface with substrates and establishes a protective milieu that bolsters the enzyme’s tolerance to organic solvents and thermal stresses[

13,

14,

15,

16].

Graphene oxide (GO), as a novel two-dimensional nanomaterial, possesses advantages such as a large specific surface area, good biocompatibility, low mass transfer resistance, and an abundance of surface functional groups[

17,

18]. As an enzyme immobilization medium, GO exhibits remarkable catalytic activity, operational stability, and storage stability[

19,

20,

21]. However, the pronounced water solubility of GO complicates its separation from the reaction system. Magnetic nanoparticles, known for their unique magnetic properties, ease of separation, and low cost, are extensively used in material recovery[

22]. The synthesis of magnetic graphene oxide (MGO) by combining magnetic nanoparticles with GO merges the strengths of both materials[

23,

24]. Utilizing MGO as a carrier for enzyme immobilization offers significant benefits. With the application of an external magnetic field, immobilized enzymes can be directionally moved and rapidly separated from the reaction system. Futhermore, functional group modification of MGO can increase its enzyme loading capacity[

25]. Currently, there is extensive research on MGO for enzyme immobilization, including studies on lipases[

26,

27], laccases[

28], cellulases[

29], etc. However, there is a notable absence of study exploring MGO’s role in PLD immobilization.

The principal aim of this study is the development of APTES-modified MGO for the immobilization of PLD. The resulting PLD-loaded MGO can be effortlessly recovered and reutilized, thereby overcoming the constraints of conventional GO and free PLD. Additionally, the characteristics of the immobilized PLD such as thermal stability, pH stability, the number of reuses, and storage stability were evaluated and compared to those of the free PLD. Ultimately, the immobilized PLD was applied to PS synthesis, and the synthesis conditions were optimized.

Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of Nanocomposites and Immobilized PLD

2.1.1. FTIR Spectra

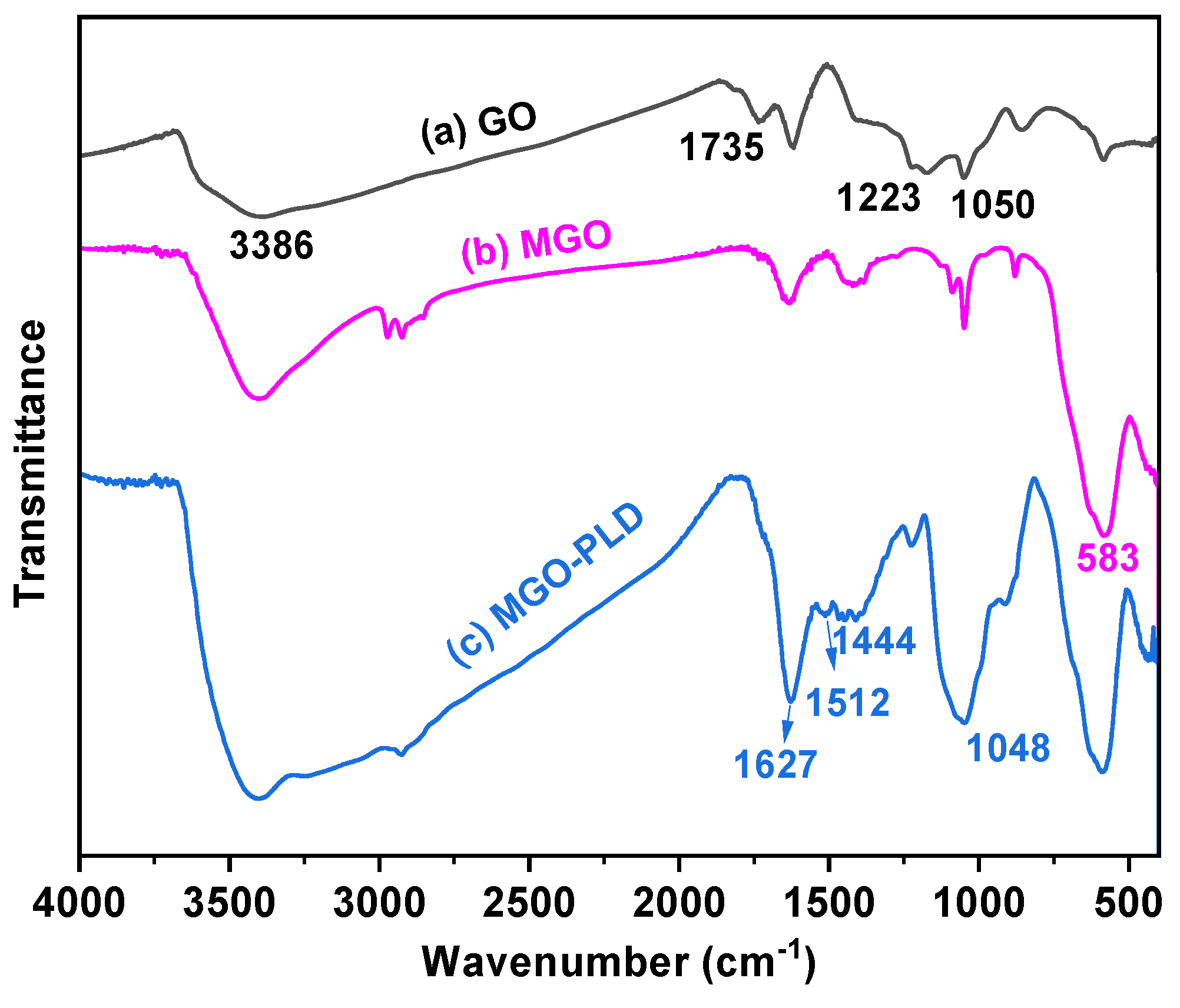

The characteristic absorption peaks of GO, MGO, and MGO-PLD were observed using a FTIR spectrometer (

Figure 1). The FTIR spectrum of GO confirmed the successful oxidation of graphite. As shown in

Figure 1a, several strong peaks corresponding to various oxygen functionalities were evident. These include the C-O stretching vibration peak attributable to the C-O-C of the epoxide group at 1050 cm

-1, the C-OH stretching vibration peak at 1223 cm

-1, the C=O stretching vibration peak at 1735 cm

-1, and the O-H stretching vibration peak at 3386 cm

-1 [

30]. After ultrasonication with magnetic nanoparticles, a distinct absorption peak was observable at 583 cm

-1 which corresponds to the Fe-O-Fe vibrational mode [

27](

Figure 1b). This indicates that Fe

3O

4 nanoparticles were effectively anchored onto the GO surface. The peak at 1048 cm

-1 can be attributed to the asymmetric stretching vibration of Si-O-Si. Additionally, the peaks at 1444, 1512 and 1627 cm

-1 are due to C-N,C=N and C=O stretching vibrations can be associated to the amide group(CO-NH

2)[

31](

Figure 1c). These findings substantiate that PLD has been immobilized on MGO-NH

2 through covalent linkage.

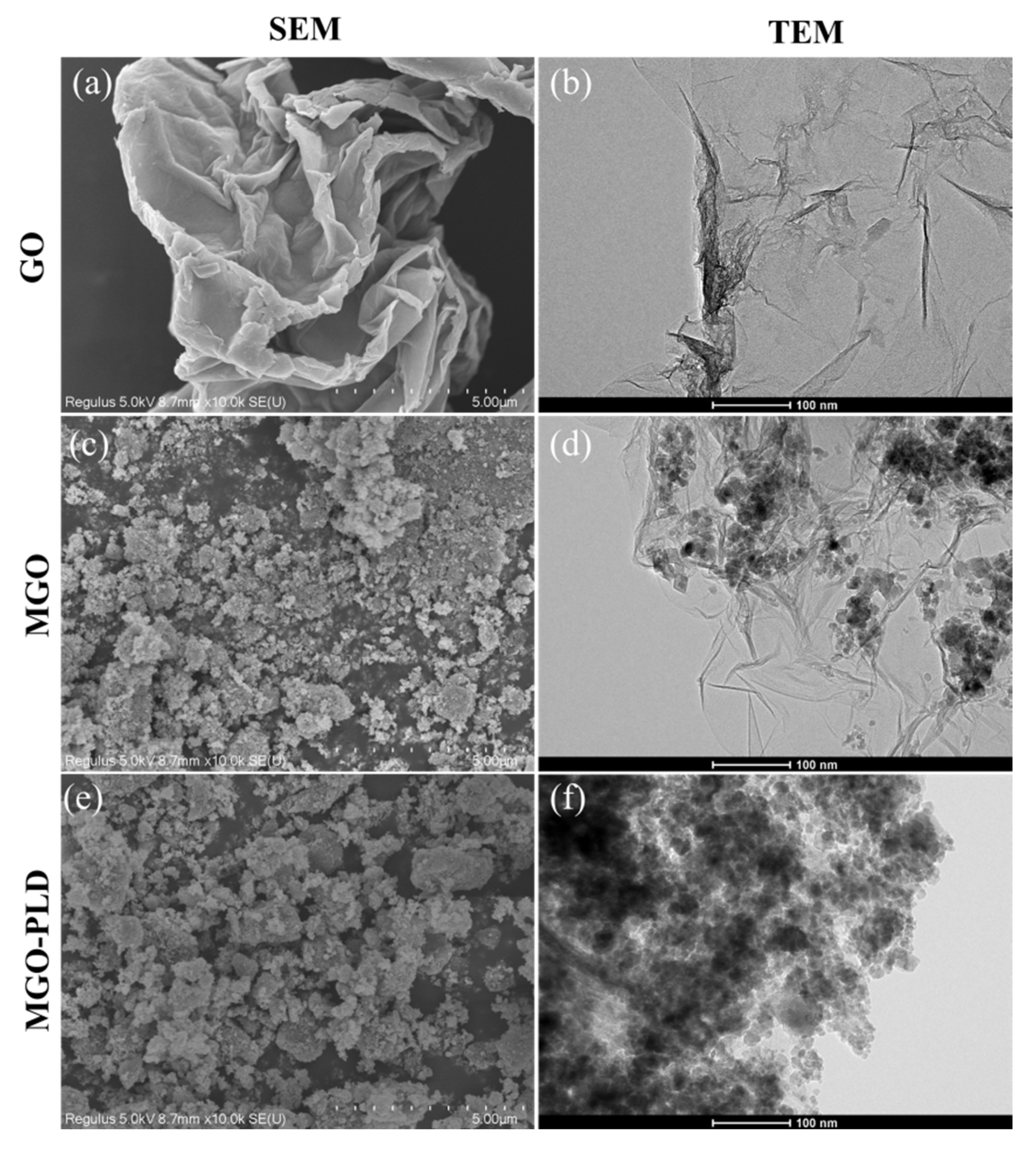

2.1.2. SEM and TEM Analysis

The morphological characteristics of GO, MGO, and MGO-PLD were investigated utilizing both SEM and TEM. In

Figure 2a, GO exhibited a thin layer morphology with extensive surface wrinkles that increased the carrier’s specific surface area, thereby enabling the loading of more Fe

3O

4 particles and enzymes.

Figure 2c shows spherical Fe

3O

4 particles on the GO surface with partial aggregation. The morphology of APTES-functionalized MGO and PLD-loaded MGO in

Figure 2e confirmed successful NH

2 modification and PLD immobilization. Additional insights into the nanoparticles’ morphology and structure are provided by TEM measurements, as illustrated in

Figure 2b,d,f. The TEM image is consistent with the SEM image and confirms the size distribution at higher magnification. In

Figure 2f, following PLD immobilization on MGO-NH

2, there is a reduction in the degree of wrinkling on the GO surface and the presence of small globular PLD, indicating the successful loading of PLD on the modified magnetic carrier.

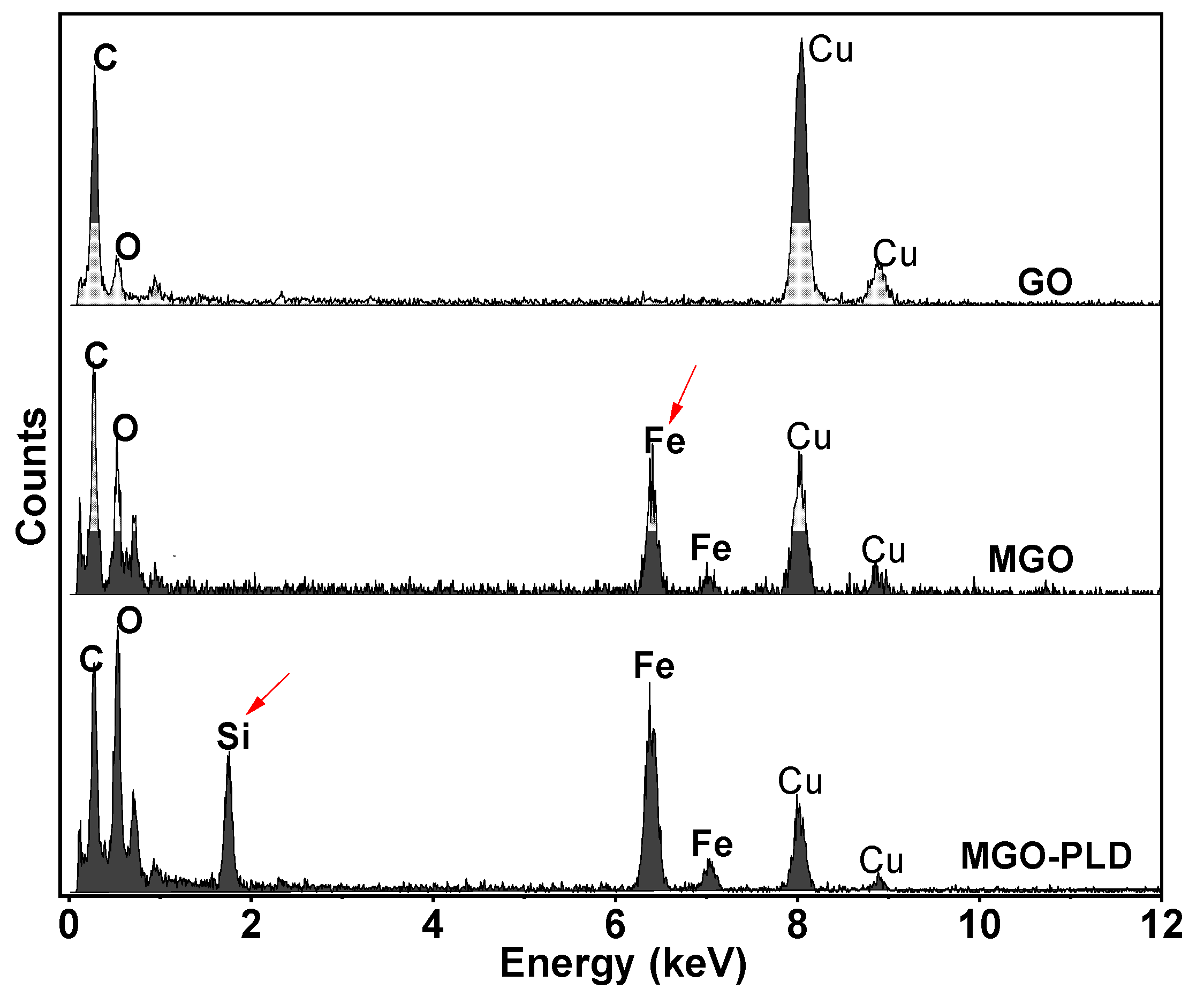

2.1.3. EDS Analysis

As demonstrated in the

Figure 3, EDS analysis confirmed the presence of Fe

3O

4 particles. This analysis revealed that apart from the C peak attributed to GO and the Cu peaks originating from the TEM grid, only Fe and O elements were discerned. Subsequent to the functionalization of MGO with APTES, a distinct Si peak emerged, signifying the successful synthesis of MGO-NH

2. Surface modification and reagent coupling are crucial because directly attaching the enzyme to MGO induces strain on its molecular motion, which subsequently leads to a decline in its reactivity. Therefore, in this study, we amino-functionalized MGO using APTES and subsequently immobilized the PLD enzyme on it through covalent attachment mediated by GA.

2.1.4. Appearance and Magnetic Property

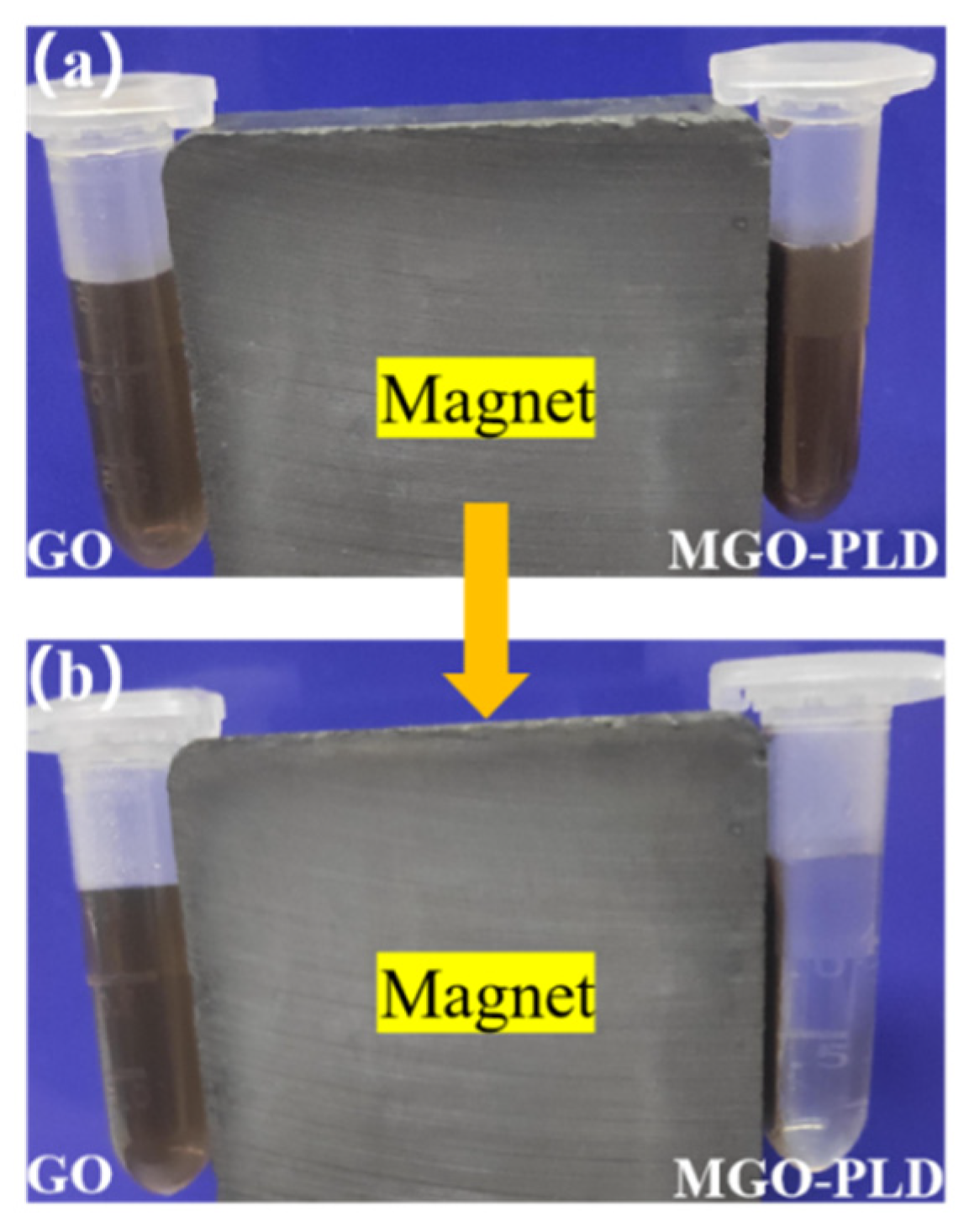

As shown in

Figure 4a, the immobilized PLD can be uniformly dispersed in double-distilled water, creating a stable brown suspension. Notably, there appears to be no significant difference between GO and MGO-PLD in terms of appearance. However, upon applying an external magnetic field, MGO-PLD is drawn to the wall of the EP tube due to the magnetic properties of MGO (

Figure 4b). This indicates that the magnetically immobilized enzymes were successfully synthesized. The capacity for recyclability is a defining feature of immobilized enzymes. Compared to traditional recycle methods like centrifugation or filtration, the use of an external magnetic field presents a more cost-effective and industrially viable option.

2.2. Optimization of PLD Immobilization on MGO-NH2

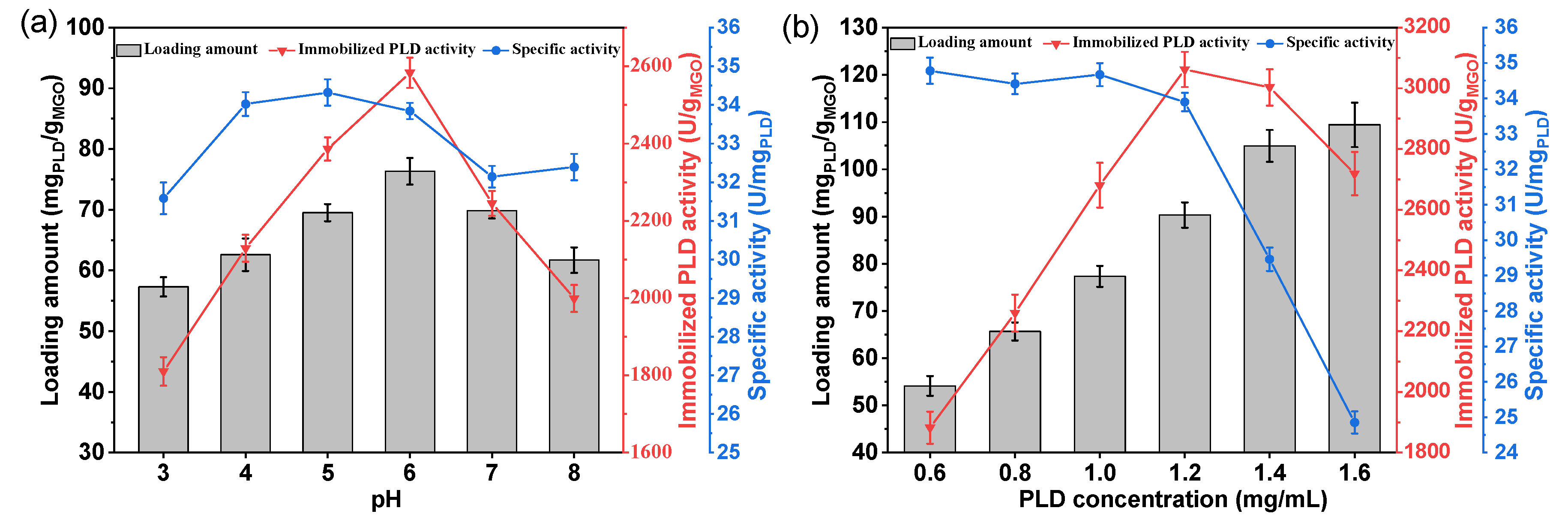

In the immobilization process, the factors affecting the adsorption capacity of MGO and enzyme activity, such as pH and enzyme concentration were investigated. As illustrated in the

Figure 5a, within the pH range of 3-8, the loading amount of PLD and the activity of the immobilized PLD initially increased and then decreased with the increase in pH. At pH 6, the maximum loading amount was achieved at 76.34 mg

PLD/g

MGO, and at this point, the immobilized enzyme also exhibited its highest activity, reaching 2583 U/g

MGO, accompanied by a specific activity of 33.8 U/mg

PLD, consistent with that of the free PLD. When the pH exceeded 6, both the loading amount and enzyme activity decreased. This may be attributed to theoretical isoelectric point of PLD is 5.97; thus, around pH 6.0, it has the minimum solubility and is easily adsorbed and immobilized by the MGO.

The influence of PLD concentration on immobilization is presented in the

Figure 5b, unlike pH, as the PLD concentration increases, the loading amount continuously rises, reaching a maximum of 109.4 mg

PLD/g

MGO. However, at this juncture, the specific activity of the immobilized PLD is only 24.9 U/mg

PLD, resulting in a total enzyme activity of merely 2719 U/g

MGO. This may be attributed to the multilayer deposition of PLD on the MGO surface, which impedes the enzyme’s interaction with the substrate. When the PLD concentration was set at 1.2 mg/mL, the immobilized PLD exhibited maximal activity, achieving 3062 U/g

MGO, with an loading amount of 90.3 mg

PLD/g

MGO and a specific activity of 33.9 U/mg

PLD, nearly identical to that of the free PLD. Immobilization customarily leads to a reduction in enzymatic specific activity[

32]. Yet, in this investigation, following the amino-modification of MGO and its subsequent covalent linkage with PLD via GA, there was an insignificant decline in the enzyme’s specific activity under optimal immobilization conditions. The optimal parameters for immobilization were determined to be pH 6.0 and a PLD concentration of 1.2 mg/mL.

2.3. Analysis of Enzymatic Properties of Free and Immolibized PLD

2.3.1. Optimal Temperature and Thermal Stability

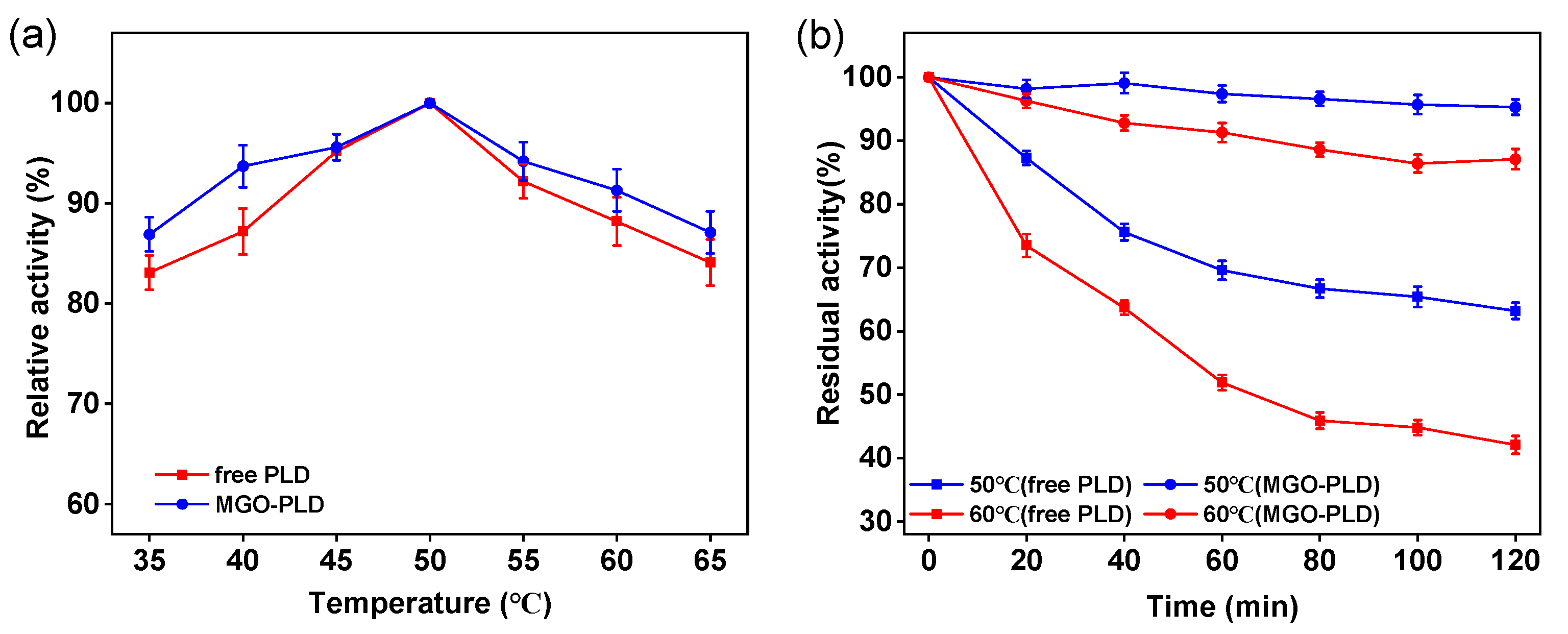

Within the temperature range of 35-65 °C, the influence of temperature on PLD activity was examined. As shown in the

Figure 6a,

the optimal temperature for the immobilized PLD is 50 °C, which is consistent with that of the free PLD. Additionally, the immobilized PLD maintains elevated relative activity over a wider temperature range compared to its free counterpart. This may be attributed to immobilization enhancing the stability of PLD enzyme, allowing the enzymatic conformation to remain relatively stable under suboptimal conditions.

The thermal stability of immobilized PLD is a key attribute for its practical utility. In order to assess this stability, both free and immobilized PLD were subjected to incubation at 50 °C and 60 °C for durations of 120 minutes, followed by an evaluation of residual activity.

Figure 6b illustrates that immobilized PLD demonstrates superior activity compared to the free counterpart, attributable to the enhanced structural rigidity conferred by immobilization. Upon incubation at 50 °C for 120 minutes, the activity of immobilized PLD remained virtually unchanged, while the free PLD exhibited a significant decline, preserving only 60% of its initial activity. When the temperature was raised to 60 °C , free PLD retaining merely 42% of its initial activity, in contrast to the immobilized PLD, which preserved approximately 90% of its initial activity. Consequently, immobilized PLD displays augmented thermal stability relative to free PLD.

2.3.2. Optimal pH and pH Stability

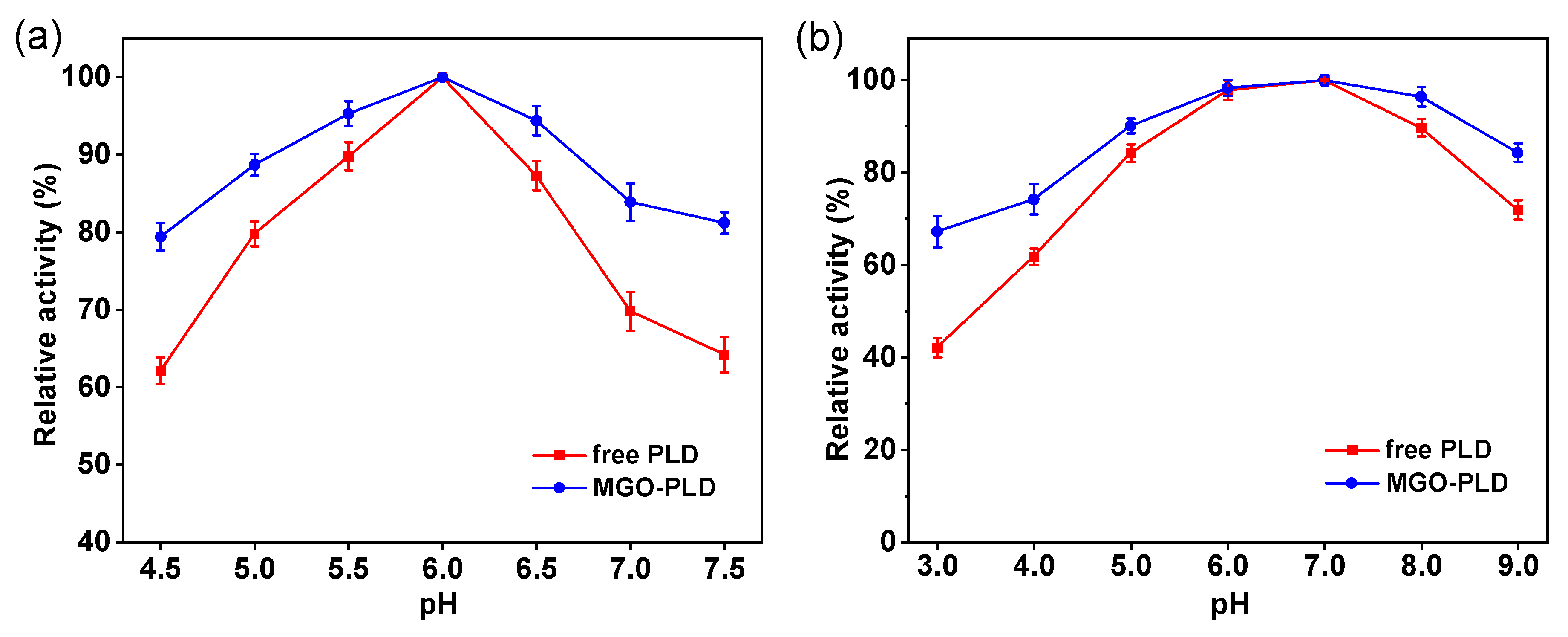

As illustrated in

Figure 7a, the optimum pH for immobilized PLD is 6.0, identical to that of free PLD. Compared to the free enzyme, the immobilized PLD shows enhanced pH tolerance over a broad range, which may be attributed to the role of MGO in the immobilized PLD system, functioning not only as a carrier but also as a “solid buffer.” This phenomenon arises because the surface of MGO possesses an abundance of hydroxyl groups, which can adsorb in aqueous solutions and balance the nearby microenvironment’s pH, thereby serving as a buffering agent. The pH stability of both free and immobilized PLD was measured, and the results are shown in the

Figure 7b. The results indicate that at pH values of 6 and 7, both the free and immobilized PLD exhibit relatively high stability; however, at other pH values, the immobilized enzyme demonstrates greater robustness and minimal activity fluctuation compared to its free counterpart.

2.4. Synthesis of PS by MGO-PLD in a Butyl Acetate-Aqueous System

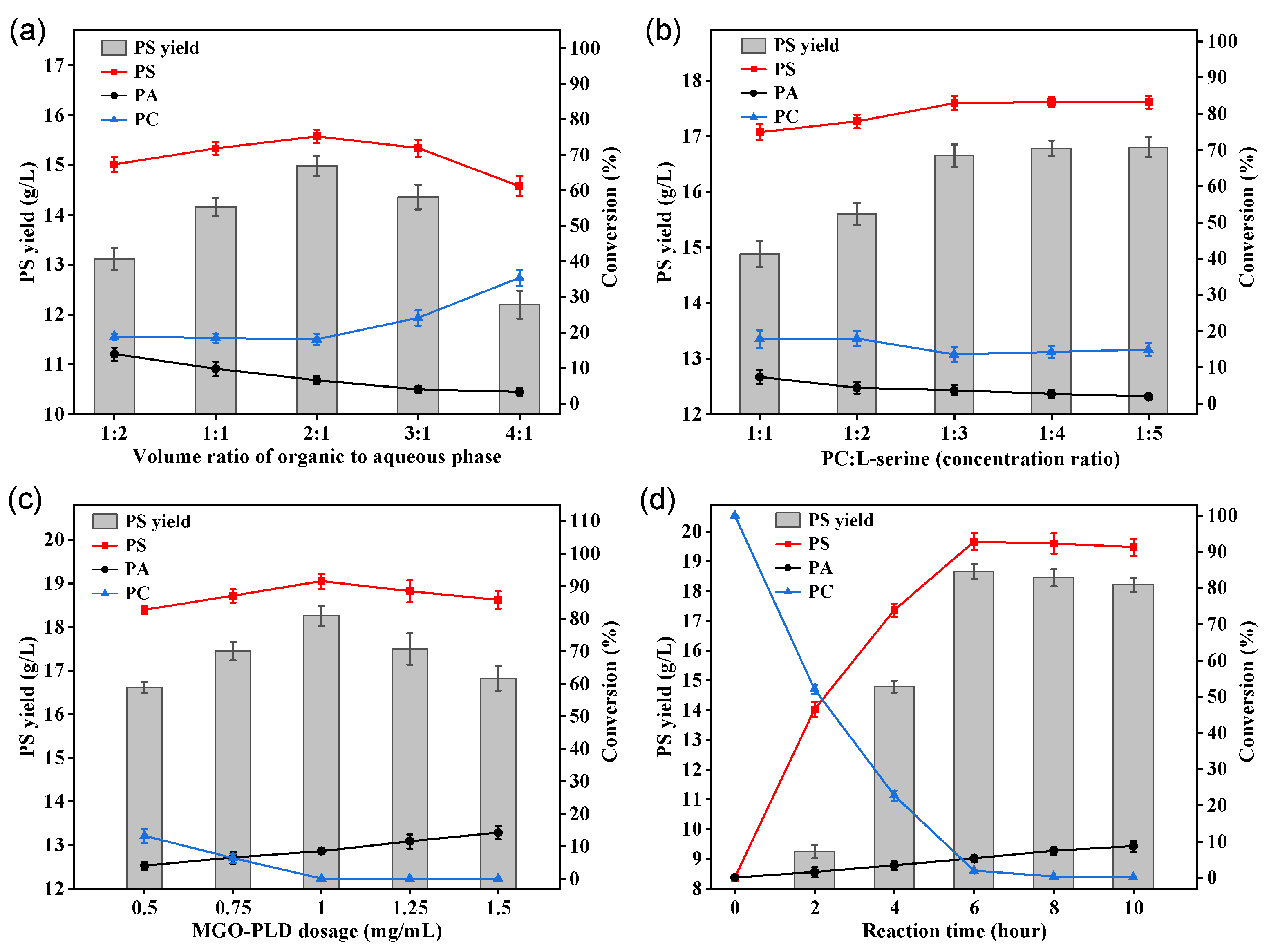

2.4.1. Effect of Organic Phase to Aqueous Ratio on PS Synthesis

The synthesis of PS from PC by PLD is commonly accompanied by hydrolysis reactions, leading to the production of PA. Water content in the reaction system is vital for this process[

33]. Elevated water levels enhance the efficiency of PC hydrolysis, while exceedingly low water contents result in decreased enzymatic activity. Therefore, this study examined the impact of various volume ratios between the orgain and aqueous phases on PS yield. The data illustrated in

Figure 8a demonstrate that the yield of PS exhibits an initial increase followed by a decline with the continuous rise of phase ratio, while the byproduct PA shows a consistent decrease. Optimal PS production is observed at a phase ratio of 2:1, wherein the yield and conversion rate stand at 14.98 g/L and 75.2%, respectively. Nevertheless, upon further elevation of the phase ratio, a diminishing trend in PS yield is noticed, concomitant with a marked escalation in PC content. This phenomenon could be ascribed to the rising concentration of butyl acetate, which potentially modifies the aqueous milieu around the PLD, thereby leading to a reduction in enzymatic activity.

2.4.2. Effect of Substrate Concentration Ratio on PS Synthesis

In addition to the volume ratio of the two phases, the concentration ratio of the dual substrates (PC and L-serine) can also affect the conversion rate of PS[

16]. An imbalance in the concentration ratio may lead to a low conversion rate of PS or an excess of substrates, causing unnecessary waste. This study investigated the effects on PS yield within a mass concentration ratio range of PC to L-serine from 1:1 to 1:5. As shown in

Figure 8b, with the increase in the proportion of L-serine, the yield and conversion rate of PS initially rose and then plateaued, and the content of the by-product PA also showed a downward trend. This might be because increasing the concentration of L-serine can inhibit the hydrolysis reaction, directing the reaction toward PS synthesis. At a substrate concentration ratio of 1:3, the PS yield was 16.65 g/L with a conversion rate of 82.9%. As the proportion of serine continued to increase, the PS yield only slightly improved due to L-serine’s concentration approaching saturation. Considering the cost of substrates, a PC to L-serine concentration ratio of 1:3 is considered optimal.

2.4.3. Effect of Enzyme Dosage on PS Synthesis

The immobilized enzyme dosage significantly affects PS yield. To study this, reactions were executed with MGO-PLD concentrations from 0.25 mg/mL to 1.5 mg/mL[

15]. As shown in the

Figure 8c, PS yield rapidly escalated with rising enzyme dosage within the experimental range before stabilizing. The maximum PS yield and conversion rate of 18.25 g/L and 91.5% respectively, were attained at an enzyme dosage of 1 mg/mL. This could be due to a higher likelihood of effective collisions between substrate and enzyme molecules as enzyme quantity rises, enhancing PS conversion efficiency. While increasing the enzyme dosage past a specific threshold failed to enhance the conversion rate of PS and resulted in a minor elevation in the formation of the byproduct PA. This phenomenon is probably due to the enzyme dosage surpassing the substrate’s available quantity. This surplus promotes competition among the enzymes for substrate interaction, given the saturated conditions. Consequently, some PLD remains unbound in the aqueous phase, exacerbating the hydrolysis reaction and hindering the augmentation of PS production. Therefore, an optimal enzyme dosage is 1 mg/mL.

2.4.4. Effect of Reaciton Time on PS Synthesis

Investigating the reaction time needed to achieve the highest yield is crucial as it optimizes cost-effectiveness[

34].

Figure 8d depictes the relationship between PS conversion rate and reaction time. The PS yield escalates with time, peaking at 6 h when the yield and conversion rate stand at 18.66 g/L and 92.8% respectively. An extension of the reaction beyond 6 h results in an augmentation of the byproduct PA, leading to a slight decline in PS yield. In summary, the most favourable conditions for synthesizing PS from PC and L-serine via MGO-PLD catalysis are specified as follows: V

butyl acetate:V

aqueous is 2:1, the concentration ratio between PC and L-serine is 1:3, MGO-PLD concentration of 1mg/mL, 50°C, aqueous solution pH maintained at 6.0, and a reaction time of 6 h. Under such conditions, the PS yield reaches 18.66 g/L, with a productivity of 3.11 g/L/h.

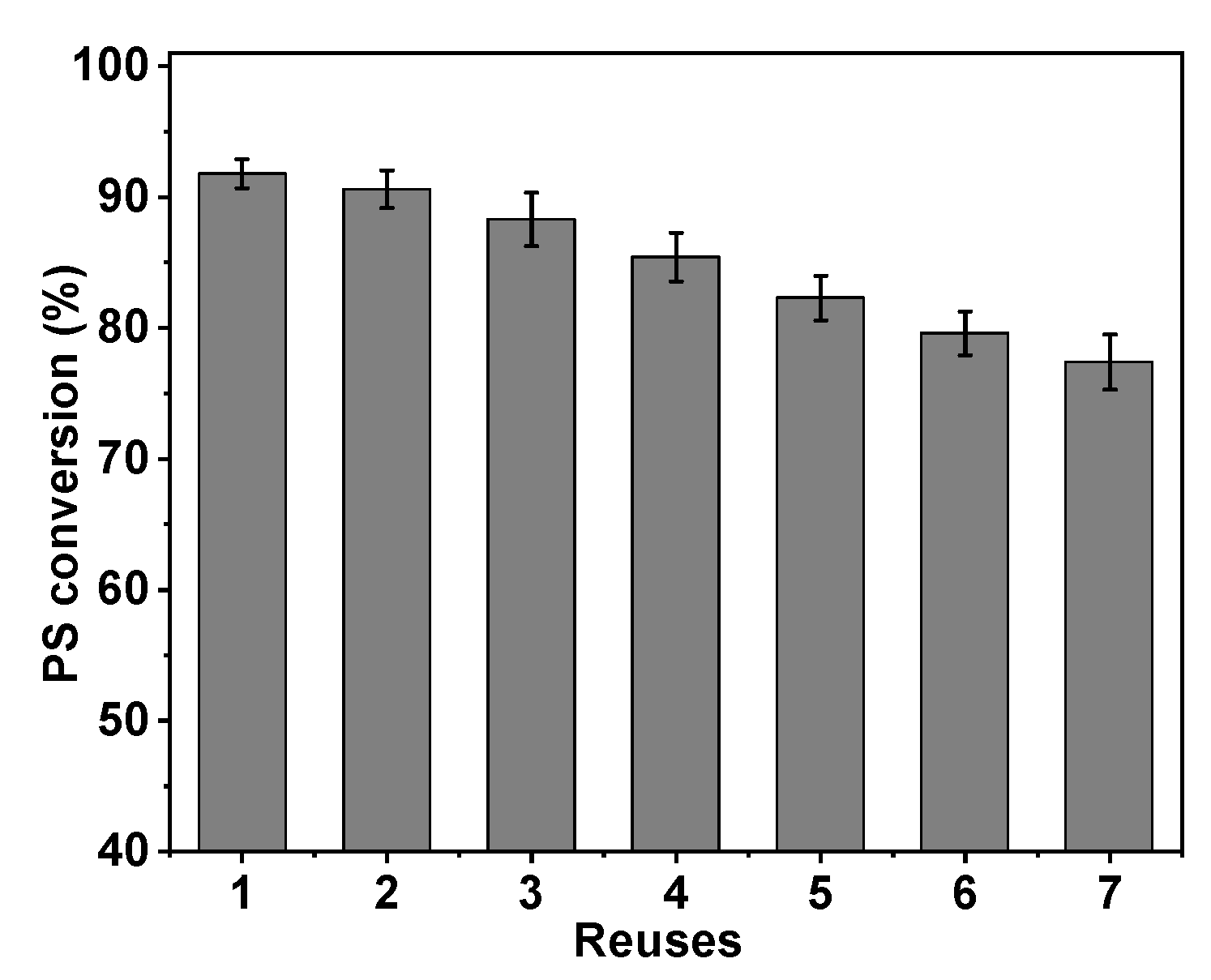

2.5. Operational and Storage Stability of Immobilized PLD

The reuse of the immobilized PLD is crucial for achieving economic viability, particularly in large-scale applications, as it significantly impacts the cost-effective usage of PLD[

32,

35]. To assess the operational stability of immobilized PLD, consecutive transphosphatidylation reactions were performed under optimal conditions with fresh substrates each time. At the conclusion of each reaction cycle, the immobilized PLD was isolated and reused by applying an external magnetic field. The PS conversion rate remained above 80% even after five reuses. Following seven rounds of reuse, the PS conversion decreased slightly to 77.4%, yet the relative yield still remained at an acceptable level of 83% (

Figure 9).

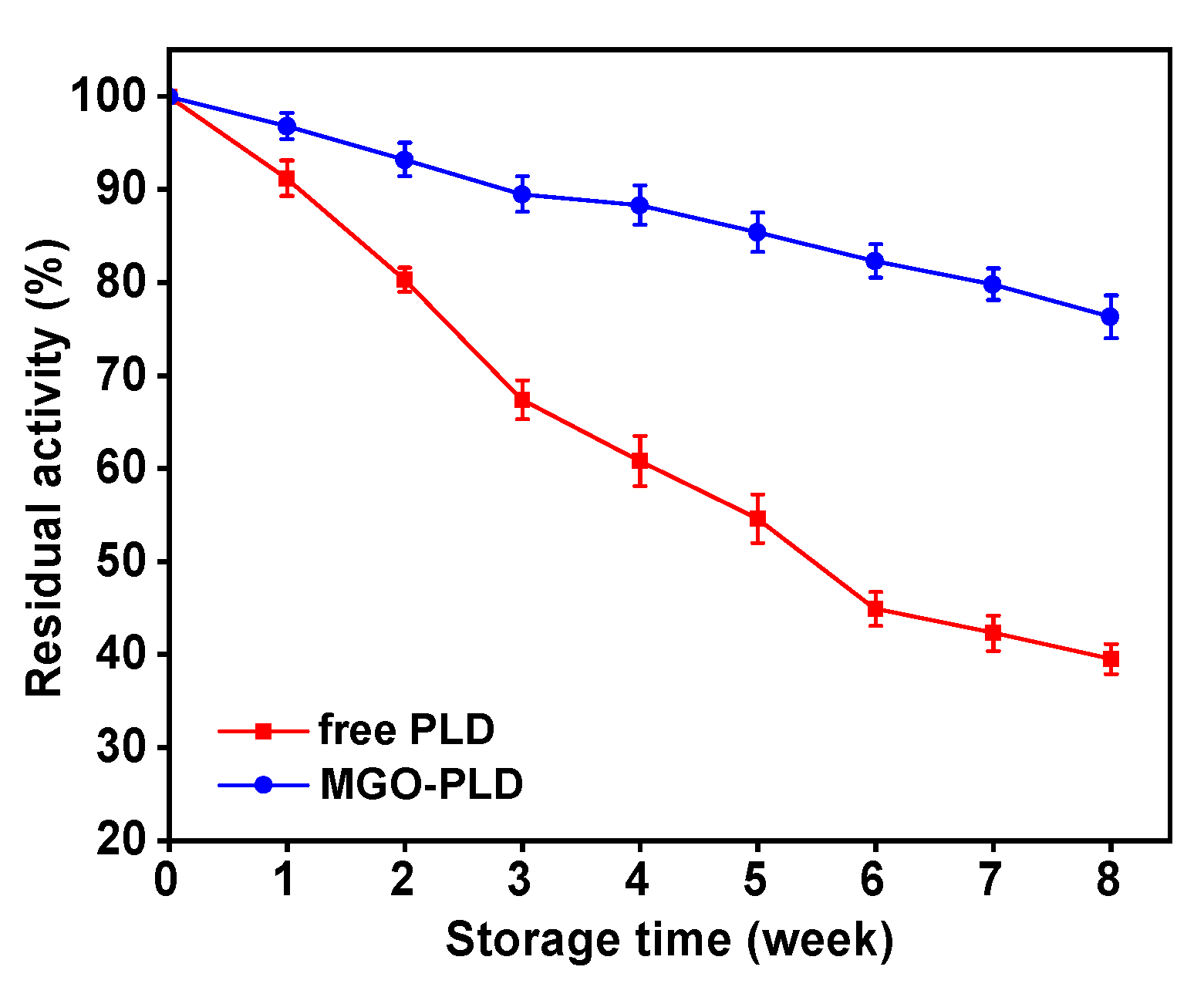

Storage stability plays a pivotal role in the adoption and utility of enzymes in industrial processes. Data illustrated in

Figure 10 demonstrate that the immobilized PLD retained 76.3% of its initial activity following eight weeks of storage at 4 °C, whereas free PLD only maintained 39.5%. In summary, the immobilized form of PLD significantly outperforms its free counterpart in storage stability, enhancing its potential for industrial applications.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Phospholipase D (PLD) from

Streptomyces antibioticus, was expressed in the recombinant strain SK-3, which was constructed in our laboratory[

36]. PLD was purified and stored in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (33.8 U/mg

protein, 1.6 mg

protein/mL, 4 ℃, pH = 7.0). Soybean lecithin (PC content ≥ 98%) and L-serine were purchased from Yuanye Biotechnology Co, Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Standard phosphatidyl lipids (PC, PS, and phosphatidic acid) were obained from Sigma-Aldrich Trading Co, Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The BCA Protein Assay Kit was purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology Co, Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Additionally, graphite powder, Fe

3O

4 magnetic nanoparticles (20 nm), 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES), and glutaraldehyde (GA) (25% w/v) were acquired from Macklin Biochemical Technology Co, Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All reagents utilized were of standard laboratory grade and procured from commercial suppliers.

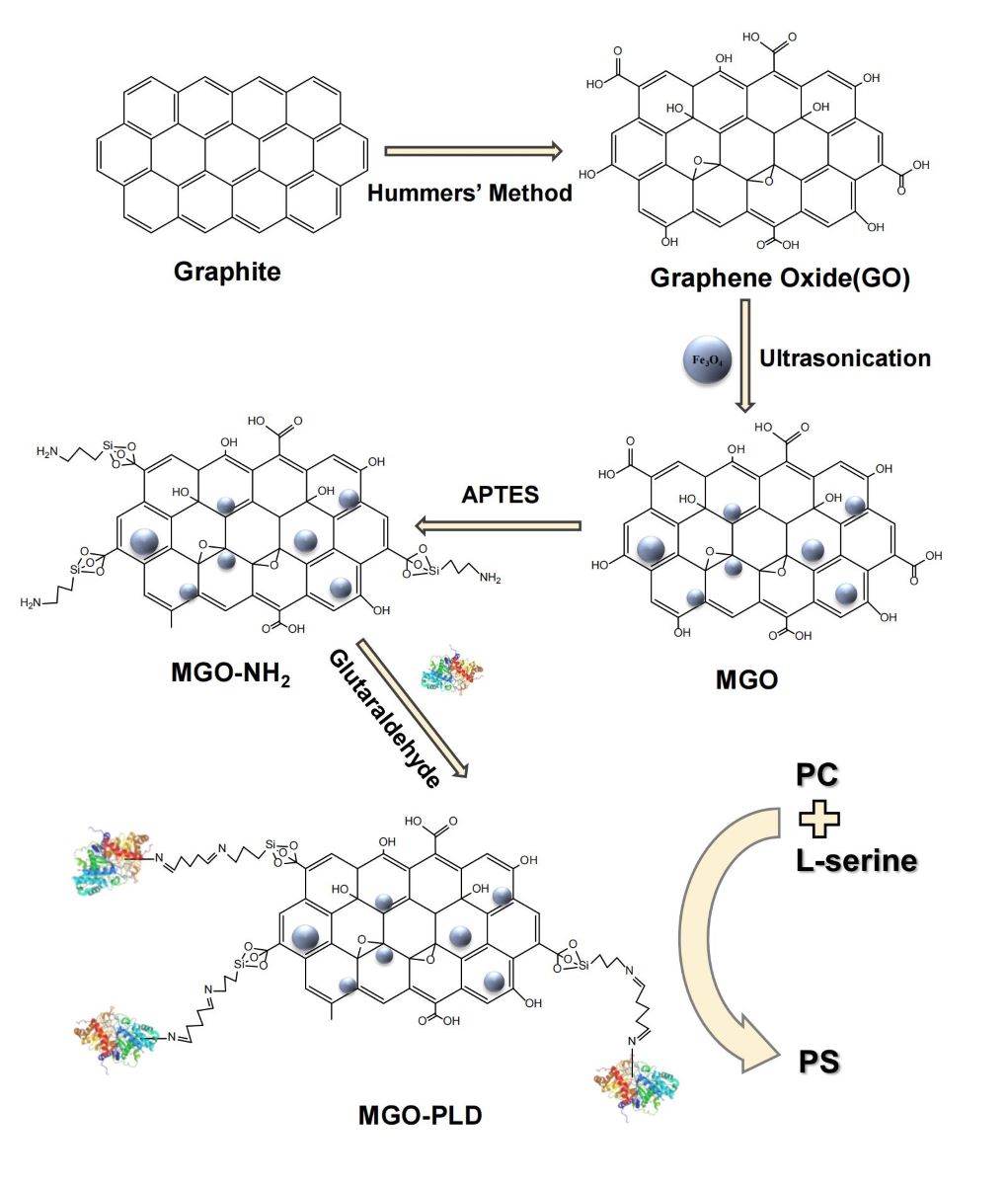

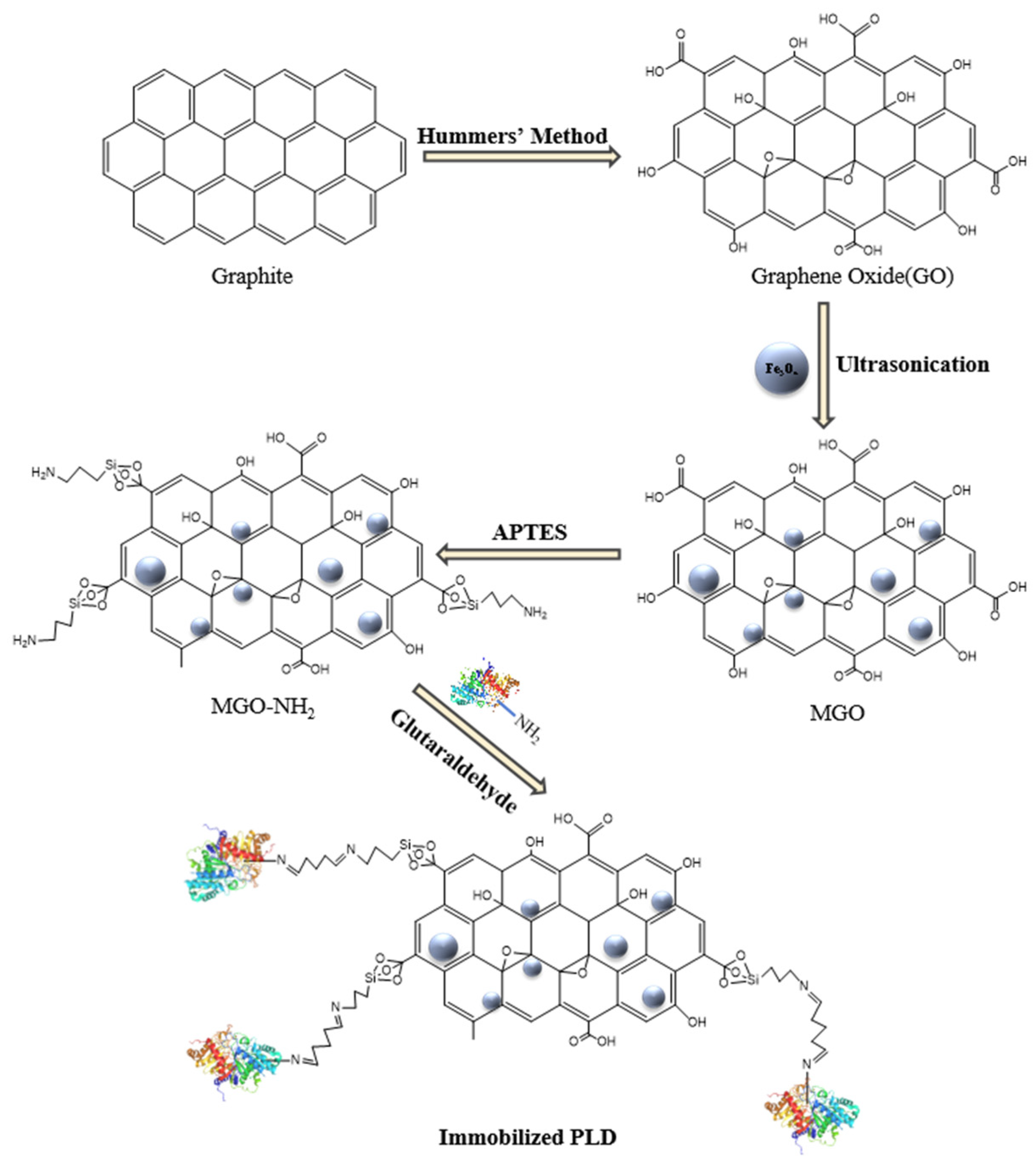

3.2. Synthesis and Modification of MGO

GO was prepared from graphene powder using the modified Hummer’s method[

37,

38]. The MGO was synthesized by impregnating GO with magnetic nanoparticles according to the literature[

30]. Specifically, 0.1 g of GO was dispersed in 100 mL of distilled water via sonication for a duration of 30 minutes. Subsequently, 0.1 g of Fe

3O

4 nanoparticles were introduced to the dispersion and further sonicated for 1 hour to achieve a uniform suspension. The resulting nanocomposites were isolated through centrifugation and subsequently freeze-dried.

In order to synthesize amino-modified MGO, 0.1 g of MGO particles were initially dispersed in 50 mL of ethanol utilizing a 20-minute ultrasonic vibration treatment. Subsequently, 0.3 mL of APTES was introduced to the reaction mixture, which was then incubated in a water bath thermostatic shaker at 30 ℃ and agitated at 180 rpm for a duration of 12 hours. Post-reaction, the modified MGO was magnetically separated, re-suspended, and subsequently washed three times in 100 mL of ethanol, employing an ultrasonic vibration for 10 minutes each time to eliminate any residual unreacted APTES. The resulting amino-modified MGO particles, designated as MGO-NH2, were subsequently vacuum dried at 50 ℃ for a period of 12 hours.

3.3. Immobilization of PLD on MGO-NH2

The modified MGO nanoparticles were functionalized with GA to facilitate the formation of a covalent bond between the enzyme and the carrier. Specifically, 2 mg of previously vacuum-dried MGO-NH

2 was dispersed in 2.0 mL of phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH = 7.0). Subsequently, 50 μL of a 25% (w/v) GA solution was introduced to initiate the reaction, which proceeded for 4 hours at 25 ℃. The resulting nanocomposites underwent three washes with phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH = 7.0) to eliminate any unreacted GA. Following this, the GA-activated carriers were suspended in 1.5 mL of buffer (0.1 M, pH ranging from 3.0 to 8.0). To this mixture, 0.5 mL of PLD, at a concentration of 0.6-1.6 mg/mL, was added and the solution was gently agitated at 25 ℃ for 6 hours to achieve immobilization. The PLD, once immobilized, was magnetically separated, rigorously washed with phosphate buffer solution (0.1 M, pH = 7.0), freeze-dried overnight, and subsequently stored at 4 ℃ for prospective applications. The final product in which the enzyme is immobilized was named MGO-PLD. A complete scheme of MGO- PLD is illustrated in

Figure 11.

This study explored the impacts of pH and PLD concentrations on both protein loading amount and enzyme activity. Protein loaded on nanoparticles was calculated by subtracting the amount of protein detected in the supernatant and washing solutions from the initial quantity used for immobilization. The concentration of unbound PLD in the supernatant and washing solutions was determined using a BCA Protein Assay Kit.

Loading amount is calculated from the Formula (1):

where

C1 is the concentration of the PLD added (mg/mL);

C2 and

C3 are the concentration of PLD in the supernatant and washing solutions, respectively (mg/mL);

V1 is the volume of the PLD added (mL);

V2 is the volume of the supernatant after immobilization (mL);

V3 is the total volume of the washing solutions (mL);

m is the weight of the nanoparticles (g).

3.4. Characterization Techniques

The surface morphologies of the samples were examined using a scanning electron microscopy (SEM; SU8010, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) at 5 kV. The crystallite sizes of the samples was analyzed by dispersing the nanopowder on carbon-coated copper grid using transmission electron microscopy (TEM; JEM-2100, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). The chemical composition of the samples was identified through Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR; Nicolet 6700, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA), with spectra recorded between 400 and 4000 cm-1.

3.5. Measurements of Free and Immobilized PLD Activity

The catalytic activities of free and immobilized PLD were evaluated in the transphosphatidylation of PC with L-serine within a biphasic system. The reaction mixture consisted of 1 mL butyl acetate containing 10 mg PC from soybean, 1 mL acetate buffer solution (0.2 M, pH6.0) containing 10 mg L-serine, and 1 mg immobilized PLD (or 50 μL free PLD). The reaction was carried out at 50℃, under constant stirring at 200 rpm for 40 minutes. Following this, the quantity of PS produced was determined using an analytical method described previously[

39]. One unit (U) of PLD transphosphatidylation activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to produce 1 μmol of PS per hour under optimal conditions.

3.6. Characterization of Free and Immobilized PLD

The optimal temperature and pH for both free and immobilized PLD were assessed using the relative enzyme activity as a metric. Under optimal conditions, the relative enzyme activities were normalized to 100%. The effect of temperature on both free and immobilized PLD was investigated within the range of 35-65℃. To test thermal stability, the enzyme was incubated at 50 and 60℃ for periods ranging from 20 to 120 minutes. Samples were periodically collected, with residual activity measured under standard assay protocols, with initial activity set as 100%. Additionally, the influence of pH was explored at the optimal temperature within a pH range of 4.5-7.5. To determine pH stability, both free and immobilized PLD were incubated for 12 hours at 4 ℃ in buffers of varying pH (3.0-9.0). Subsequently, residual activity was measured under standard assay conditions, with maximum enzyme activity taken as 100%.

3.7. Preparation of PS Using MGO-PLD

PS was synthesized from L-serine and PC by MGO-PLD in a butyl acetate-aqueous system. The PC is dissolved in butyl acetate, at a concentration of 20 mg/mL, as the organic phase. L-serine is dissolved in an acetate buffer, at a concentration of 20 mg/mL, as the aqueous phase. The total volume of the reaction is 2 mL.The reaction took place at pH 6.0, 50℃ with stirring at 200 rpm, for 10 h. Factors such as the ratio of organic to aqueous phase volumes(V

butyl acetate:V

aqueous), substrate concentration ratio, immobilized PLD dosage (mg/mL), and reaction time were systematically evaluated for their impact on PS yield. The compositon of the production after reaction was analyzed using the method we previously reported[

39]. The conversion of PS, PA and the content of PC were calculated by Formula (2)–(4).

Where mPS, mPA, and mPC are respectively the weight of PS, PA and PC.

3.8. Operational and Storage Stability of Immobilized PLD

The operational stability of the immobilized PLD was measured by quantifying PS yield during continuous cycles of repeated use. After each batch reaction, the immobilized PLD was recovered through magnetic separation, then washed with a phosphate buffer solution (0.1 M, pH = 7.0), and used for the next batch reaction. By adding fresh substrates under optimal conditions, the immobilized PLD was repeatedly used for multiple rounds of PS production.

The storage stabilities of free PLD and immobilized PLD were assessed by monitoring their residual activities at various time points during storage at 4 °C.

3.9. Statistical Analysis

The experiments were carried out by triplicate. Statistical analyses were accomplished by using SPSS 25.0, and Origin 2024. The results were expressed to be mean ± standard deviation.

4. Conclusions

This investigation involved the creation of MGO nanocomposites through impregnation method, which were then modified with -NH2 groups. Utilizing MGO-NH2 as a carrier, PLD was immobilized after it was activated with glutaraldehyde. Compared to free PLD, MGO-PLD demonstrated superior pH stability, thermal stability, and storage stability, indicating its potential as a novel biocatalyst for PS production. Furthermore, the immobilized PLD achieved a 92.8% PS conversion rate with a productivity of 3.11 g/L/h. Notably, even after being recycled seven times, the conversion rate of PS remains steady at 77.4%. The findings suggest that MGO-PLD has robust stability and high efficiency in PS conversion, making it potentially suitable for large scale industrial PS production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S.; methodology, H.S. and J.W.; validation, H.S., J.W. and B.G.; writing -original draft, H.S. ; writing -review and editing, B.G., H.L. and H.Z. ; supervision, H.L. and H.Z.; funding acquistion, H.S. and H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by The Scientific and Technological Research Project of Henan Province (Project No. 242102310343), The Fundamental Research Fund of Henan Academy of Sciences (Project NO. 230618039), Joint Fund of Henan Province Science and Technology R&D Program (Project NO. 235200810005), High-level Talent Research Start-up Project Funding of Henan Academy of Sciences (Project NO. 231816042), and Innovation Team Project of Henan Academy of Sciences (Project NO. 20230104).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data of this study are presented. Additional data will be provided upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alenka, Č.; Thibaud, D.; Guillaume, L. Phosphatidylserine transport in cell life and death. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2023, 83, 102192. [Google Scholar]

- Arjan, B.; Wiel, H.; Fred, B.; et al. Cognition-enhancing properties of subchronic phosphatidylserine (PS) treatment in middle-aged rats: comparison of bovine cortex PS with egg PS and soybean PS. Nutrition 1999, 15, 778–783. [Google Scholar]

- Sylvain, R.; Vania, H.; Ségolène, G.; et al. Phosphatidylserine enriched with polyunsaturated n-3 fatty acid supplementation for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents with epilepsy: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Epilepsia Open 2024, 9, 582–591. [Google Scholar]

- João C, C.; Juliana C, P.; Roberto, A.; et al. Phosphatidylserine: an antidepressive or a cognitive enhancer? Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 2004, 28, 731–738. [Google Scholar]

- EW, F.; Baggen M; Nedwidek P; et al. Double-blind study with phosphatidylserine (PS) in parkinsonian patients with senile dementia of Alzheimer’s type (SDAT). Progress in clinical and biological research 1989, 317, 1235–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Hee-Don, C.; Jeong-Jun, H.; Ji-Hee, Y.; et al. Effect of soy phosphatidylserine supplemented diet on skin wrinkle and moisture in Vivo and clinical trial. Journal of the Korean Society for Applied Biological Chemistry.

- Jingnan, C.; Jun, L.; Haoyu, X.; et al. Phosphatidylserine: An overview on functionality, processing techniques, patents, and prospects. Grain & Oil Science and Technology 2023, 6, 206–218. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, J.L.; Toru, K.; Naomi, G.; et al. Conversion of phosphatidylcholine to phosphatidylserine by various phospholipases D in the presence of L-or D-serine. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Lipids and Lipid Metabolism 1989, 1003, 277–283. [Google Scholar]

- Wen-Bin, Z.; Jin-Song, G.; Hai-Juan, H.; et al. Mining of a phospholipase D and its application in enzymatic preparation of phosphatidylserine. Bioengineered 2018, 9, 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Hai-Juan, H.; Jin-Song, G.; Yu-Xiu, D.; et al. Phospholipase D engineering for improving the biocatalytic synthesis of phosphatidylserine. Bioprocess and biosystems engineering 2019, 42, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Shuang, S.; Ling-Zhi, C.; Zheng, G.; et al. Phospholipase D (PLD) catalyzed synthesis of phosphatidyl-glucose in biphasic reaction system. Food chemistry 2012, 135, 373–379. [Google Scholar]

- Xun, A.; Hong, C.; Ji-Qian, X.; et al. Preparation and functionality of lipase-catalysed structured phospholipid–A review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2019, 88, 373–383. [Google Scholar]

- Binglin, L.; Jiao, W.; Xiaoli, Z.; et al. An enzyme net coating the surface of nanoparticles: a simple and efficient method for the immobilization of phospholipase D. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2016, 55, 10555–10565. [Google Scholar]

- Maria, R.L.A.; Mohammad, M.; Eleonora, R.; et al. Phospholipase D Immobilization on Lignin Nanoparticles for Enzymatic Transformation of Phospholipids. ChemSusChem 2024, 17, e202300803. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.; Ling, Z.; Gangcheng, W.; et al. A novel immobilized enzyme enhances the conversion of phosphatidylserine in two-phase system. Biochemical Engineering Journal 2021, 172, 108035. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.; Ling, Z.; Gangcheng, W.; et al. Design of amino-functionalized hollow mesoporous silica cube for enzyme immobilization and its application in synthesis of phosphatidylserine. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2021, 202, 111668. [Google Scholar]

- Chul, C.; Young-Kwan, K.; Dolly, S.; et al. Biomedical applications of graphene and graphene oxide. Accounts of chemical research 2013, 46, 2211–2224. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer Daniel R, Park Sungjin, Bielawski Christopher W, et al. The chemistry of graphene oxide. Chemical society reviews 2010, 39, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A.; Muhammad, B.; Tahir, R.; et al. Graphene and graphene oxide: Functionalization and nano-bio-catalytic system for enzyme immobilization and biotechnological perspective. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2018, 120, 1430–1440. [Google Scholar]

- Karan, C.; Krishan, K.; Pannuru, V.; et al. Protein immobilization on graphene oxide or reduced graphene oxide surface and their applications: Influence over activity, structural and thermal stability of protein. Advances in colloid and interface science, 2021, 289, 102367. [Google Scholar]

- Soňa, H.; Marie, Z.; Daniel, B.; et al. Graphene oxide immobilized enzymes show high thermal and solvent stability. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 5852–5858. [Google Scholar]

- Vatta Laura, L.; Sanderson Ron, D.; Koch Klaus, R. Magnetic nanoparticles: Properties and potential applications. Pure and applied chemistry 2006, 78, 1793–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, L.L.; Reddy, K.J.; Rao, K.R. A comprehensive review of applications of magnetic graphene oxide based nanocomposites for sustainable water purification. Journal of Environmental Management 2019, 231, 622–634. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, H.; Chen, Y.; Xiliu, Z.; et al. Magnetic graphene oxide: synthesis approaches, physicochemical characteristics, and biomedical applications. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2021, 136, 116191. [Google Scholar]

- Jiayong, D.; Hongyan, Z.; Yuting, Y.; et al. Improving the selectivity of magnetic graphene oxide through amino modification. Water Science and Technology 2017, 76, 2959–2967. [Google Scholar]

- Dianyu, Y.; Ziyue, L.; Xiaonan, Z.; et al. Study on the modification of magnetic graphene oxide and the effect of immobilized lipase. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 216, 498–509. [Google Scholar]

- Wenlei, X.; Mengyun, H. Immobilization of Candida rugosa lipase onto graphene oxide Fe3O4 nanocomposite: Characterization and application for biodiesel production. Energy Conversion and Management 2018, 159, 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.; Yifei, Z.; Zeping, L.; et al. Enhanced stability and catalytic performance of laccase immobilized on magnetic graphene oxide modified with ionic liquids. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 346, 118975. [Google Scholar]

- Roberto, P.-C.F.; Miguel, C.J.; Sara, I.; et al. Magnetic graphene oxide as a platform for the immobilization of cellulases and xylanases: Ultrastructural characterization and assessment of lignocellulosic biomass hydrolysis. Renewable Energy 2021, 164, 491–501. [Google Scholar]

- George Z, K.; Nikolina A, T.; Orestis, K.; et al. Magnetic graphene oxide: effect of preparation route on reactive black 5 adsorption. Materials 2013, 6, 1360–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahkameh, A.; Asghar, T.-K. Immobilization of glucoamylase on triazine-functionalized Fe3O4/graphene oxide nanocomposite: Improved stability and reusability. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2016, 93, 1183–1191. [Google Scholar]

- Jia-Qin, W.; Xiao-Mei, X.; Ding-Lin, W.; et al. Immobilization of phospholipase D on macroporous SiO2/cationic polymer nano-composited support for the highly efficient synthesis of phosphatidylserine. Enzyme and Microbial Technology 2020, 142, 109696. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, C.; Lin, X.; Yan, L.; et al. Bioconversion of phosphatidylserine by phospholipase D from Streptomyces racemochromogenes in a microaqueous water-immiscible organic solvent. Bioscience, biotechnology, and biochemistry 2013, 77, 1939–1941. [Google Scholar]

- Chengmei, Y.; Jianan, S.; Weilong, G.; et al. High-Yield Synthesis of Phosphatidylserine in a Well-Designed Mixed Micellar System. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2023, 72, 504–515. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Jia-Qin, W.; Neng-Bing, L.; et al. Efficient immobilization of phospholipase D on novel polymer supports with hierarchical pore structures. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 141, 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Juntan, W.; Haihua, Z.; Huiyi, S.; et al. Development of a thiostrepton-free system for stable production of PLD in Streptomyces lividans SBT5. Microbial Cell Factories 2022, 21, 263. [Google Scholar]

- Leila, S.; Anjali A, A. Graphene oxide synthesized by using modified hummers approach. Int J Renew Energy Environ Eng 2014, 2, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hummers Jr William, S.; Offeman Richard, E. Preparation of graphitic oxide. Journal of the american chemical society 1958, 80, 1339–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishan, G.; Juntan, W.; Mengxue, Z.; et al. Efficient Biosynthesis of Phosphatidylserine in a Biphasic System through Parameter Optimization. Processes 2023, 11, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).