Introduction

The cells of fungi, like those of some other organisms (bacteria, plants, etc.), are covered with the cell wall. A common characteristic of organisms with the cell wall is the presence of intracellular hydrostatic pressure (turgor pressure or simply turgor). Turgor occurs because the overall osmolarity of the cytoplasm is usually higher than that of the extracellular environment. Water entering the cell (or moving as cytoplasm from other parts of the colony, for example, in aerial hyphae) creates pressure from the plasma membrane/protoplast on the cell wall (Lew, 2019). Fungi can quickly regulate turgor pressure in their cells through various mechanisms: osmolyte synthesis (one of the main pathways is the high-osmolar glycerol (HOG) pathway), active transport of ions across the plasma membrane, certain types of intrahyphal transport, hyphal growth, and other mechanisms such as regulation of membrane permeability to water through aquaporins and changes in the hydrophobicity of cell covers (Lew & Nasserifar, 2009; Lew, 2010; Lew, 2019; de Oliveira et al., 2021; Herman & Bleichrodt, 2022). Turgor is of great importance for fungi: it regulates the size and shape of cells, as well as the tension of the plasma membrane; participates in the mechanism of apical growth and transport within hyphae; ensures the penetration of hyphae or haustoria into the substrate or tissue of the host; and takes part in the active release of spores or conidia, in the capture of prey by predatory fungi, etc. (Weber, 2002; Lew et al., 2004; Lew, Nasserifar, 2009; Abadeh, Lew, 2013; Steinberg et al., 2018; Herman, Bleichrodt, 2022; Chen et al., 2023; Panstruga et al., 2023).

It is known that in specialized fungal cells, turgor pressure can reach high values (up to 8 MPa in the appressorium of Magnaporthe grisea, for example; Ryder et al., 2019; Gow & Lenardon, 2023). It was previously believed that turgor pressure in unspecialized cells of filamentous fungi under normal conditions (on standard nutrient media, for example) was also quite high (1-1.5 MPa and higher). However, modern studies indicate more modest values of average turgor pressure in vegetative hyphae. This divergence is due to different methods of assessing turgor. The previously used method of primary plasmolysis gives an overestimated result in fungi due to the strong adhesion of the plasma membrane to the cell wall (Robertson & Rizvi, 1968; Heath & Steinberg, 1999; Walker & White, 2017). For example, Lew and colleagues have shown in several studies using the pressure probe method that the turgor in Neurospora crassa cells averages about 0.5 MPa, which is approximately three times lower than the values reported in earlier works (Robertson & Rizvi, 1968; Lew et al., 2004; Lew & Nasserifar, 2009; Municio-Diaz et al., 2022). Chevalier and coworkers (2024), using the deflation assay, demonstrated that even in the apical cells of several species of ascomycetes and Mucor circinelloides, the turgor value ranges from only 0.3 to 0.7 MPa (only in Aspergillus nidulans does it exceed 1 MPa). This is despite the fact that the average pressure in the apical cell (at least in the growing one) usually exceeds the pressure in the rest of the hypha. Moreover, the same authors showed that even such a canonical function of turgor as participation in the elongation of the apical cell during fungal growth is not so clear – they did not find a positive correlation between the value of turgor pressure in the apices and growth rate in a number of species of filamentous fungi (Chevalier et al., 2024).

Two groups of fungi and fungi-like organisms are distinguished based on their relationship to maintaining constant turgor values. Unfortunately, too few organisms have been studied in this regard to draw a complete picture for different systematic groups of fungi. In N. crassa, after placing its mycelium in a moderate hyperosmotic environment, the turgor first decreases significantly. Then, due to the uptake of ions from the outside and the synthesis of osmolytes, the fungus almost restores the initial pressure within about an hour (Lew et al., 2004; Lew, Nasserifar, 2009). The oomycete Achlia bisexualis, under the same conditions, also loses turgor but does not attempt to restore it (Lew et al., 2004). It is known that oomycetes can live without turgor pressure; even their apical growth is possible at zero turgor (Harold et al., 1996; Lew et al., 2004). Moreover, their strategy for penetrating the substrate is different – the tip of the penetrating hypha may not be under pressure, and the actin cap at the tip disassembles so that the apex becomes soft and flattened (Walker et al., 2006). Halotolerant fungi living in environments with high salt concentrations have zero or low turgor values (Lew, 2019).

Our recent studies have shown that basidiomycetes, including the xylotroph Stereum hirsutum, the coprotroph Coprinus comatus, and the plant pathogen Rhizoctonia solani, likely do not consistently allocate resources to maintain constant turgor. By examining changes in hyphal diameter, which correlate with turgor pressure, under moderate hyperosmotic conditions, it has been found that these fungi do not tend to quickly restore their original size. It has been shown that, in some cases, the actin cytoskeleton affects the diameter of hyphae. With depolymerization of F-actin, the thickness of the vegetative hyphae of S. hirsutum changes (Mazheika et al., 2024 preprint). It was previously observed that the destruction of F-actin in basidiomycetes, and possibly other fungi, leads to increased formation of large invaginations (macroinvaginations) of the plasma membrane, an increase in their size, and stimulation of tubular invagination formation (Mazheika et al., 2020a, 2022). These results evidently contradict established ideas about the fungal cell, which has been compared to a bicycle tire, where an elastic rubber chamber (plasma membrane) is pressed tightly against an elastic but reinforced tire (the cell wall; Lew, 2019). In such a cell, even endocytosis with pin sizes up to 100 nm requires a lot of energy and fully developed cross-linked F-actin elements. The formation of macroinvaginations larger than 200 nm, which in xylotrophic basidiomycetes can take the form of thick tubes up to several tens of microns long, would be simply impossible, especially with disassembled F-actin.

All of the above indicates that turgor pressure is important in fungal physiology, but it is not the only factor determining the shape and size (and their rapid change) of fungal cells, influencing plasma membrane tension and other vital functions, at least for certain groups of fungi. On the other hand, much suggests that the actin cytoskeleton of fungi is the primary candidate for supplementing or replacing turgor functions. Of course, the idea is not new: for example, Heath and Steinberg, in their 1999 work, discussed an alternative turgor physiological model for fungi, in which the contractile actin cytoskeleton and focal adhesion of the plasma membrane to the cell wall played an important role. However, over the past quarter-century, new data have emerged in mycology that can be used to develop concepts alternative (complementary) to the turgor physiological model.

An important idea underlying this work can be expressed differently. A basidiomycete fungus, particularly a mycorrhiza-former or xylotroph, forms colonies extending hundreds of meters in the soil litter, connecting living or dead trees and their remains. These fungi constantly undergo rapid changes in environmental conditions and face aggressiveness from other organisms, along with frequent nitrogen starvation. They possess high-speed and complex long-distance transport along hyphae and cords. Therefore, they cannot afford to rely significantly on turgor pressure, as such dependence would create inertia and hinder their ability to quickly adapt to fluctuations in environmental conditions of any magnitude. This review reconsiders and expands the previously proposed curtain model, which describes certain aspects of the organization and physiology of a non-apical and unspecialized fungal cell (Mazheika et al., 2020a). The model focuses on basidiomycetes, but it is likely that, in one variation or another, it can be applied to a wide range of fungi. In addition to reviewing the major components of the curtain model, this review discusses group-specific structural defense mechanisms that enable fungi to survive and maintain continuous cellular functionality in rapidly changing environmental conditions.

The Curtain Model

The curtain model describes the equilibrium physiological state of fungal hyphae. In an equilibrium state, osmotic and other parameters of the external environment change either slightly or slowly, allowing the fungal cell to adapt without a non-equilibrium lag. In a nonequilibrium state with rapid and significant changes in external conditions (stress), the curtain model is unsuitable for describing the status of the fungal cell. This is because, in many fungi and oomycetes, disassembly of F-actin, a key element of the curtain model, occurs during hyperosmotic shock (Slaninova et al., 2000; Walker et al., 2006; Bitsikas et al., 2011; Elhasi, Blomberg, 2019). Under stressful conditions, fungi trigger rapid structural-physiological defense mechanisms, similar to airbags in cars, to prevent cell damage in the initial minutes of a shock. One example of such an airbag is the complex system of macroinvaginations in xylotrophic basidiomycetes (Mazheika et al., 2022); other examples will be provided later as the material is presented.

In addition to the above properties, the curtain model is characterized by the following: i. It works only in cells with relatively low or medium turgor, making it unsuitable for apical and various specialized fungal cells. ii. It is optimal for filamentous basidiomycetes but can also be applied to other groups of fungi. iii. The model is an open system—new components can be added as new scientific knowledge emerges.

The essence of the curtain model is as follows: the actin cytoskeleton, working in coordination with other components of the curtain model, can replace or supplement the functions of turgor pressure in the fungal cell. In cells without turgor or with low turgor values that have already reached an equilibrium state, the curtain system completely takes over the functions of turgor. In cells with moderate turgor pressure, the curtain system compensates for membrane tension, elastic strain of the cell wall, cell form and size, and other parameters when there are small changes in turgor pressure both throughout the cell and with uneven pressure distribution in different parts of the same cell or hypha. The curtain system allows the fungal hyphae to continue their normal, uninterrupted life activities and functions despite equilibrium changes in external and internal conditions.

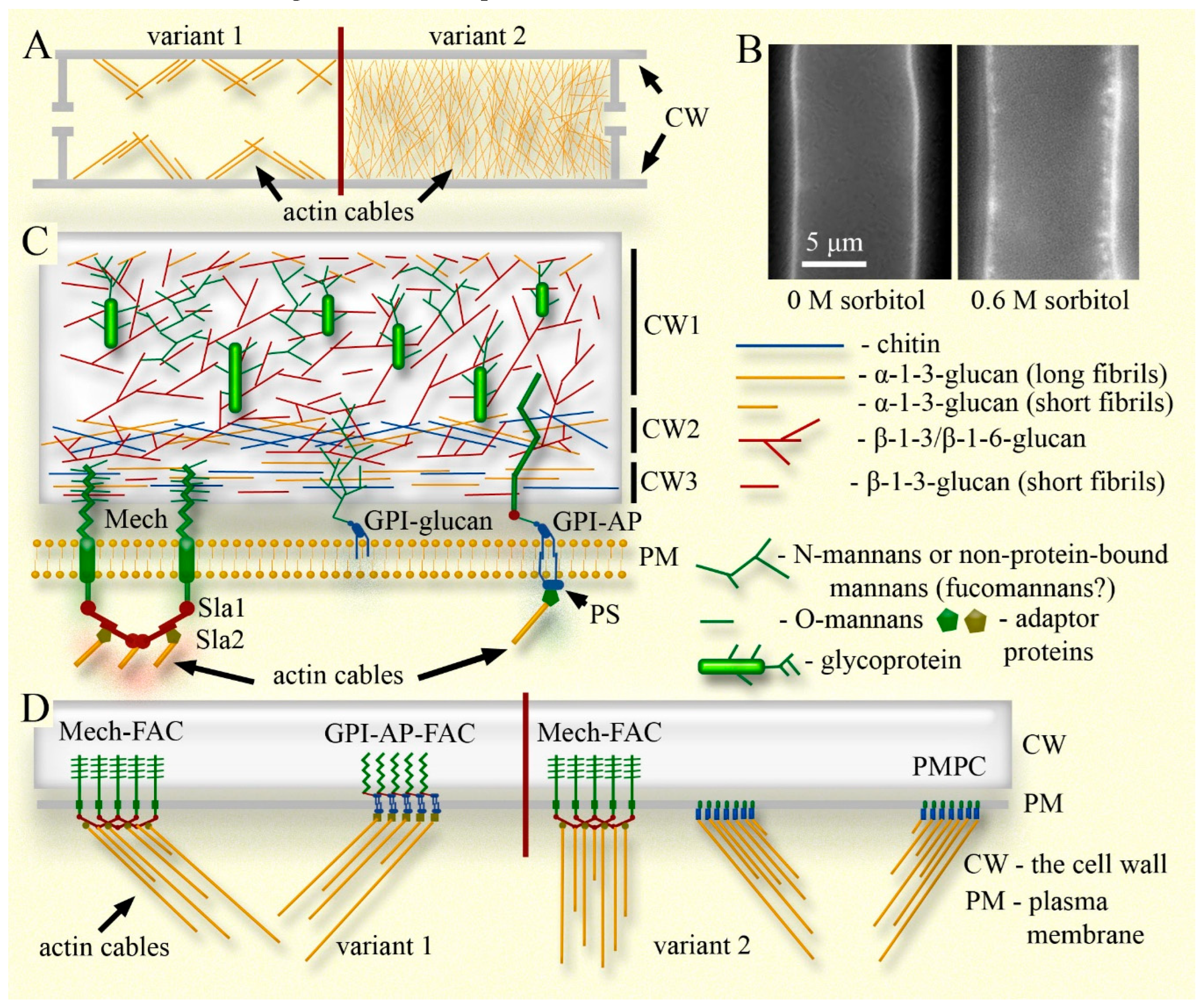

The curtain model includes the following four components (see Figs. 1 and 2): i) actin cables connected to focal adhesion complexes and sites (FACs/FASs) on the cytoplasmic side (possibly to other elements of the plasma membrane), which, in cells with not high turgor, perform several important functions, primarily regulating the tension of the plasma membrane and maintaining or regulating the size and shape of the hyphae. ii) The elastic cell wall, which stretches or shrinks with the entire cell, capable of quickly changing its elasticity if necessary. iii) The plasma membrane tightly adhered to the cell wall (preserving the periplasmic space) through FACs/FASs and other connections. iv) Systems of macroinvagination of the plasma membrane that provide a membrane pool, allow rapid changes in the working surface of the plasma membrane, and prevent damage and dysfunction during both equilibrium and sudden changes in the size of the fungal cell. It should be noted that although the curtain model works in conjunction with turgor, supplementing or replacing it, turgor itself is not a component of the model, as the model can also describe cells with zero turgor.

If all the listed components are combined into a single system, the following analogy can be given: a curtain hanging on a window represents the plasma membrane; the curtain folds represent macroinvaginations; the curtain rod represents the cell wall; rings securing the curtain to the rod represent FACs/FASs; and curtain drivers (sticks used to push high curtains from below) represent actin cables. Of course, such an analogy is incomplete; it does not account for the elasticity of the cell wall, changes in cell size and the role of actin in this, the influence of turgor, and many other parameters of the fungal cell. However, it provides a superficial idea of what the curtain model describes and why it has such a name. Next, the components of the curtain model will be examined in detail.

Component I: Actin Cytoskeleton

Fungal Actin Cables

Fungi have three main types of intracellular structures formed by F-actin: Arp2/3-dependent patches, formin-dependent contractile rings, and formin-dependent cables (Berepiki et al., 2011; Lichius et al., 2011). Additionally, fungi exhibit other specific actin structures (Dagdas et al., 2012; Kopecka et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2021). The cables are bundles of parallel-displaced F-actin filaments, nucleated by formin and cross-linked by tropomyosin and other proteins. Cables can be quite long, usually a few micrometers in length, but can reach 25 μm (Berepiki et al., 2011). At the same time, they are a very dynamic structure, typically assembled and disassembled within a few seconds (Bergs et al., 2016; Takeshita, 2019). In filamentous fungi, actin cables perform important functions in the apical cells. These cables serve as rails for active transport, involving myosin V motors, of secretory vesicles into the apical body (Spitzenkörper), intercepting cargo from microtubules. Actin cables not only ensure the concentration of enzymes and structural materials at the hyphal tip, necessary for apical growth. They are in a loop of mutual regulation with microtubules, which supply protein polar markers to the apex that regulate the assembly of actin cables. Actin cables, in turn, regulates the convergence of microtubule ends into the apex and enhances growth polarity (Takeshita et al., 2014; Peñalva et al., 2017; Steinberg et al., 2018; Takeshita, 2019). However, individual mechanisms of apical growth may vary among different fungi and fungi-like organisms (Lilje, Lilje, 2006; Wernet et al., 2021).

Functions of Actin Cables in the Curtain Model

Actin cables in the curtain model are assigned a control-power role and perform several functions. Two of the most important ones are as follows. The first function: actin cables regulate plasma membrane tension in cells with not high turgor pressure. By connecting to FACs/FASs proteins through adapter proteins (see next sections and

Figure 1; another variant of the curtain model will also be described there, with regulation of membrane tension by actin not through FACs/FASs), the cables move them along the inner layer of the cell wall, providing tension on the plasma membrane. In this case, a complex system of cables can not only tension the entire plasma membrane of the cell, replacing turgor pressure, but also provide a local change in membrane tension. For example, a cable system can relax a local region of the plasma membrane without altering the tension of the entire membrane, to accelerate endocytosis in this segment or for another purpose. Such a local change in plasma membrane tension is probably possible even with high turgor pressure but requires significant energy costs (Mazheika et al., 2020a). The described function of actin cables in the curtain model is confirmed by the behavior of the plasma membrane when fungal mycelium is treated with actin polymerization inhibitors. In several publications, photographs of hyphae from various fungal species treated with these inhibitors show numerous parietal invaginations of the plasma membrane (not always noted by the authors; Yamashita and May, 1998; Lee et al., 2007; Upadhyay and Shaw, 2008; Lewis et al., 2009). The disassembly of F-actin leads to an increase in the number and size of plasma membrane macroinvaginations, including tubular forms, in individual cells of

R. solani (Mazheika et al., 2020a). A similar result was obtained for

S. hirsutum (

Figure 2). In this fungus, latrunculin A (an actin depolymerizer) increases the size and number of lomasomes (a type of macroinvagination) in hyphal cells by an average of 2–3 times (Mazheika et al., 2022). These results indicate that in fungi, plasma membrane tension in many cells is provided not by turgor but by the actin cytoskeleton. Its depolymerization leads to a sharp relaxation of the membrane and the activation of a protective mechanism during sudden changes in conditions (airbag), such as the formation of macroinvaginations of the plasma membrane.

The second function of actin cables in the curtain model is to participate in changing or maintaining the size (shape) of cells. It has been shown that depolymerization of F-actin can lead to changes in the diameter of S. hirsutum hyphae (Mazheika et al., 2024 preprint). Such changes are not large – on average no more than 7% of the hyphal diameter – and hyphae can both shrink and expand under the influence of latrunculin A. However, the destruction of F-actin does not affect the size of R. solani and C. comatus hyphae (Mazheika et al., 2024 preprint). This likely indicates that the shape-restraining function of actin in fungal cells is expressed differently across species, in contrast to its role in regulating plasma membrane tension. It is also known that depolymerization of actin often leads to swelling of the hyphal tips. This is shown for Allomyces macrogynus, a number of oomycetes, A. nidulans, R. solani, etc. (Heath, 1990; Heath et al., 2003; Gupta, Heath, 1997; Srinivasan et al., 1996; Torralba et al., 1998; Heath, Steinberg, 1999; Walker et al., 2006; Lichius et al., 2011; Mazheika et al., 2020a). For oomycetes, it was shown that immediately after treating the mycelium with actin polymerization inhibitors, the apical cells, under pressure, first accelerate their growth, then stop and often swell (in oomycetes, it is not the tip itself that often swells, but the subapex). Apical cells without turgor do not accelerate in growth before stopping and rarely swell (Gupta & Heath, 1997). Often, swelling of the apices is explained by a failure of growth polarity – without actin cables, polar markers are distributed throughout the periphery of the apex, leading to softening and radial synthesis of the cell wall (Lichius et al., 2011). However, judging by the rapidity and uniformity of the swelling of the apices, the swelling occurs primarily due to the disruption of actin cables holding and shaping the hyphal tip with a thin apical cell wall. Without actin cables, turgor pressure in the growing apex easily inflates it. This can also explain the sharp acceleration of growth at the beginning of mycelium treatment with actin inhibitors. Therefore, the function of actin cables in the hyphal tip is not only to transport vesicles to the apical body and regulate growth polarity but also to create a rigid frame for the soft cell wall of the apex. A similar mechanism likely operates in non-apical cells, but it is less apparent there (the hypha changes only slightly in diameter as actin is disassembled) and is expressed differently in various fungi (for example, S. hirsutum vs. R. solani). In Botrytis cinerea, mutants with a deletion of one of the actin genes exhibit slower hyphal growth compared to the wild type and are more compact, which may be associated with a reduction in the cell shape-restraining function of actin (Li et al., 2020). In a study on the germination of fungal hyphae through a thin channel of a microfluidic device (Fukuda et al., 2021), growth cessation and swelling of apices in certain species of fungi may be associated with the disassembly of actin (the authors and other researchers offer another explanation; Fukuda et al., 2021; Wernet et al., 2021). In those fungi where, during growth through a thin channel, mechanoreceptors are triggered and the CWI pathway is activated, the actin cables disassemble, causing the apices to swell and growth to stop. In fungi with a lower growth rate and hyphal diameter, such actin disassembly does not occur, apparently due to differences in the sensitivity of triggering the CWI pathway.

It cannot be ruled out that the actin cytoskeleton performs its form-restraining function not only by creating mechanical resistance to cell shrinkage or expansion but also through contractility. Contractility of not only actomyosin rings in septa but also the cytoplasm as a whole has been shown for several fungi, although this issue remains open and poorly studied (Heath, Steinberg, 1999; Reynaga-Peña, Bartnicki-García, 2005; Steinberg et al., 2017). Budding yeast has been shown to have a cell wall that constantly vibrates at a frequency of approximately four oscillations per millisecond. The authors suggest that such oscillation is associated with the work of molecular motors, including myosin (Pelling et al., 2004). If actin cables can actively shrink or expand the fungal cell, then the actin cytoskeleton can more fully replace turgor pressure, both buffering changes in cell size during osmotic fluctuations and substituting the turgor gradient to create mass flow transport inside the hyphae. Data shows that disassembly of F-actin leads to a decrease in the rate of cytosolic streaming in A. niger, which can confirm the actin contractile hypothesis, although the authors explain this effect differently (Bleichrodt et al., 2015).

It should be noted once again that the curtain model describes the equilibrium physiological state of the mycelium. Accordingly, actin performs its functions within a certain small range of fluctuations in osmotic and other conditions. In the case of a non-equilibrium process, such as a rapid and strong change in the osmolarity of the medium and a sharp drop in turgor, disassembly of F-actin occurs in many fungi (Slaninova et al., 2000; Walker et al., 2006; Bitsikas et al., 2011). A comparison can be made with a sailing ship in a storm – sailors remove the sails; otherwise, both the sails and the ship may be damaged.

Microscopic Visualization of the Actin Cable System as a Component of the Curtain Model

In classical work on oomycetes with fluorescent labeling, for example see review by Heath (1990), it is evident that not only the hyphal apices, which possess a powerful cap of actin cables, but also the hyphae themselves are permeated with a dense matrix of actin cables/filaments (Gupta & Heath, 1997; Walker et al., 2006).

In filamentous fungi, the actin cable system is not as well visualized as in oomycetes. It is shown that the cables are well developed in the germ tubes of some fungi and in conidial anastomosis tubes; there is an actin cap in the apical cells of

M. grisea also (Lichius et al., 2011; Li et al., 2020). A network of actin cables is observed in some fine penetration hyphae and in specific areas of vegetative hyphae during septa and anastomoses formation, in the distribution of nuclei during clamp connection formation, after hyphal damage, and during the formation of new hyphae at the damage site (Salo et al., 1989; Roberson, 1992; Timsonen et al., 1993; Gorfer et al., 2001; Timonen & Peterson, 2002; Berg et al., 2016; Jung et al., 2018; Raudaskoski, 2019; Li et al., 2020; Garduño-Rosales et al., 2022; Wernet et al., 2023). According to the curtain model, the actin cable system should be well-developed and present in most cells, not just occasionally visualized in certain areas of hyphae. The lack of systematic visualization of the actin system may be due to imperfections in our methods for fluorescent labeling of actin. Phalloidin in many fungi does not effectively label actin; and expressing actin in the same ORF with a fluorescent protein leads to artifacts and poorly identifies actin cables (Heath et al., 2003; Takeshita & Fisher, 2019). Mycologists often use either lifeact fused with a fluorescent protein or the expression of tropomyosin with a fluorescent tag (Delgado-Alvarez et al., 2010; Lichius et al., 2011; Berg et al., 2016; Takeshita & Fisher, 2019; Garduño-Rosales et al., 2022). However, labeled Lifeact can also affect the assembly of actin cables, and there is evidence that in animals, it does not label all types of actin structures (Lichius et al., 2011). Instead of tropomyosin, other crosslinkers may be included in the cables involved in the curtain model. It is possible that the actin cables in question are even more dynamic than those in the apices, and their rapid assembly and disassembly make visualization even more difficult. It is also possible that we are not looking for exactly what we need: the regulation of plasma membrane tension and the form-restraining function may not be performed by powerful actin cables, which are easy to visualize microscopically, but rather by a network of very thin cables or filaments (

Figure 1A). Indeed, in the work of Garduño-Rosales et al. (2022), the authors indicate that in the hyphae of

Trichoderma atroviride, there are individual cables that are part of “a very fine network of actin filaments that run the entire length of the hyphal tube” (see the supplementary videos for this work). Assumptions about the presence in the cytoplasm of hyphae of a dense meshwork of actin, not detectable by available means, were proposed back in the 1980s (McKerracher, Heath, 1987).

Component II: The Cell Wall

The fungal cell wall is an important component of the curtain model. The fungal cell wall paradigm has recently undergone changes. It is now clear that the cell wall is not a permanently rigid and low-permeability outer shell of the fungal cell. It is a dynamic, complex structure that quickly changes its elasticity, easily alters its size and internal structure, and is permeable, if necessary, not only to small molecules but also to larger particles, extracellular vesicles, and even bacteria (Casadevall & Gow, 2022; Gow et al., 2023). Casadevall and Gow (2022) even proposed abandoning the usual term and renaming the cell wall, suggesting alternatives like “cell plegma” or “reticulum.”

The understanding of the structure and molecular composition of the fungal cell wall has also evolved in recent years with the advent of modern non-invasive techniques such as ssNMR (solid-state Nuclear Magnetic Resonance; Fernando et al., 2023a). The molecular composition of the cell wall varies among different groups of fungi, but the main components in ascomycetes and basidiomycetes are generally similar: glucans, chitin, and glycoproteins (Kang et al., 2018; Panstruga et al., 2023).

The Structure of the Yeast Cell Wall

In Candida albicans and other model ascomycetous yeasts, the cell wall consists of two main layers. The inner layer contains long fibrils of chitin and β-1,3-glucans cross-linked with each other. This layer is responsible for the elasticity of the cell wall. The higher the level of fibril cross-linking and the longer the chitin fibrils, the more rigid the cell wall will be (Lenardon et al., 2020; Gow, Lenardon, 2023). This layer of the cell wall thickens in response to hyperosmotic shock: it is assumed that cross-links between fibrils are destroyed, and β-1,3-glucan fibrils are compressed along their axis. As a result, the glucan-chitin layer expands and encroaches upon the mannoprotein outer layer of the cell wall, leading to a significant thickening of the wall as a whole (Morris et al., 1986; Slaninova et al., 2000; Ene et al., 2015; Elhasi, Blomberg, 2019; Gow, Lenardon, 2023). If the glucan-chitin layer is relatively weakly cross-linked (in the case of C. albicans, this depends on factors such as the carbon source in the nutrient medium), it will expand less during hyperosmotic shock and will not significantly increase the overall thickness of the cell wall. More precisely the wall thickens during osmotic shock in any case as the cell shrinks, but not so substantially. Yeast with a more cross-linked glucan-chitin complex tolerates hyperosmotic shock better. This is believed to be due to a lower rate of cell shrinkage under hypertonic conditions, attributed to the greater rigidity of the cell wall (Ene et al., 2015; Gow & Lenardon, 2023). However, perhaps, here is more important the greater expansion of the wall – another version of the airbag – the expanding cell wall in a shrinking cell, follows the protoplast faster, does not allow the protoplast to tear away from the wall, and reduces the damageability of the plasma membrane.

The outer layer of the yeast cell wall is represented by mannoproteins. Most mannoproteins are linked to the glucan-chitin complex via GPI (glycophosphatidylinositol) and β-1-6-glucans (Patel, Free, 2019; Gow, Lenardon, 2023). The GPI linkage here is modified and is discussed in more detail in the next section. Other linking patterns are possible, for example, mannoproteins may be PIR proteins (De Groot et al., 2005; Montano-Silva et al., 2024). In ascomycetous yeasts, short β-1-6-glucans are thought to perform the main cross-linking function between the two layers of the cell wall, and have other important functions (Garcia-Rubio et al., 2020; Bekirian et al., 2024 preprint). Long N-mannan branched chains of the mannoproteins form the negative charged (due to phosphomannans – individual N-mannan side chains are linked to other chains via phosphate) hydrophobic outer layer of the wall. The mannanoprotein layer is responsible for the relative hydrophobicity of the cell surface (partly replacing hydrophobins, which are absent in yeast), limited permeability of the cell wall for large molecules, and protects the inner rigid layer from lytic enzymes (Gow, Lenardon, 2023; Lopatukhin et al., 2024).

The Structure of the Cell Wall in Filamentous Ascomycetes

Among the filamentous ascomycetes, A. fumigatus, and to a lesser extent other aspergilli and N. crassa, have been primarily studied (Kang et al., 2018; Patel & Free, 2019; Chihara et al., 2020; Garcia-Rubio et al., 2020; Chakraborty et al., 2021; Latge & Wang, 2022; Lamon et al., 2023; Fernando et al., 2023b; Gautam et al., 2024a, b). The cell wall of A. fumigatus and some other ascomycetes, like the yeast wall, consists of two main layers, but they differ from those of yeast. The inner layer consists of a rigid hydrophobic scaffold formed by an α-1-3-glucan-chitin complex. The scaffold is immersed in a hygroscopic matrix of long branched β-1-3/β-1-6-glucan fibrils, which in some fungi have terminal short β-1-3/β-1-4-glucan regions. The outer layer is soft and mobile, composed of short fibrils of various glucans, galactomannans, and aminopolysaccharides. The latter imparts a positive charge to the surface of the cell wall. The outer layer is weaker than that of yeast cross-linked to the rigid layer (Gautam et al., 2024a, b). Let us consider the most important distinctive features of the cell wall of filamentous ascomycetes, keeping in mind that many questions remain unresolved and pluralistic:

(i) Based on the ssNMR method, Kang and colleagues (2018) showed that in the inner rigid layer of the cell wall of A. fumigatus, α-1-3-glucans are closely associated with chitin, and not β-1-3-glucans as in yeast. This ssNMR model has been further developed, and now a number of authors believe that α-1-3-glucan is the most rigid molecule in the aspergillus cell wall, even more rigid than chitin. However, in the outer mobile layer of the wall, the α-1-3-glucan fibrils are also found, but here they are shorter and less rigid than in the inner layer and serve a different function (Latge, Wang, 2022; Fernando et al., 2023b; Gautam et al., 2024a, b). The presence of α-1-3-glucan in the outer layer is confirmed by experiments with fluorescent probes in A. orizae (Nakazawa et al., 2024). Other authors also note the presence of α-1-3-glucans in the cell wall of A. fumigatus and N. crassa, although they attribute less structural significance to it (Patel & Free, 2019; Chihara et al., 2020; Garcia-Rubio et al., 2020). α-1,3-Glucan is also present in the cell wall of the basidiomycete yeast Cryptococcus neoformans (Garcia-Rubio et al., 2020). Fernando and colleagues (2023b) showed that in several halotolerant Aspergillus species, at optimal growth concentrations of sodium chloride, there is no α-1-3-glucan in the cell wall. It appears only when the nutrient medium is highly salinized. In another study on A. fumigatus using echinocandins, inhibitors of β-1,3-glucan synthesis, it was shown that β-1,3-glucan deficiency is compensated not only by an increase in the amount of α-1,3-glucan in the cell wall but also by the appearance of two new forms of α-1,3-glucan in the rigid and mobile phases (Widanage et al., 2024). These data reflect an important general property of the fungal cell wall: the polysaccharide composition changes dynamically depending on conditions, and some polysaccharides can structurally and functionally replace others if necessary.

(ii) It is traditionally believed that in yeast, both mannoproteins and the less common non-protein mannans bind to the β-1-3-glucan-chitin core through short β-1-6-glucans (independent, not included in the β-1-3/β-1-6-glucans; Kang et al., 2018; Gow, Lenardon, 2023). Many authors believe that filamentous ascomycetes do not have independent β-1-6-glucans, and their function is performed by β-1-3/β-1-6 or β-1-3/β-1-6/β-1-4-glucans (Patel, Free, 2019; Chihara et al., 2020; Garcia-Rubio et al., 2020; Chakraborty et al., 2021; Fernando et al., 2023b).

(iii) The mannans of yeasts and filamentous ascomycetes also differ. First, yeast N-mannans can be very long (more than 100 mannose residues) and form the outer mannanoprotein layer of the yeast cell wall. Filamentous ascomycetes also have many N-mannans, including in the outer mobile layer of the cell wall, but they are not as long (Tefsen et al., 2012; Patel, Free, 2019). However, non-protein-bound filamentous fungal mannans (FTGM – fungal-type galactomannans) can also be very long. The main chain can consist of 9-10 repeats of a module of several mannose quartets with an α-1-3 linkage and an α-1-6 connection between the quartets (Chihara et al., 2020; Garcia-Rubio et al., 2020). Second, unlike yeast, in filamentous ascomycetes, mannans are represented by galactomannans. Both short N- and O-galactomannans and long branched non-protein-associated FTGMs are composed of mannose backbones with α-1-3- and α-1-6-linkages, and galactofuranose side chains with β-1-5- and β-1-6 bonds. In short N-mannans, galactofuranose can be represented by single terminal molecules (Tefsen et al., 2012; Patel & Free, 2019; Chihara et al., 2020). Third, in yeasts, mannoproteins are covalently linked to the glucan-chitin core. In contrast, in filamentous ascomycetes, many galactomannans are not linked to the rigid inner layer of the cell wall and are relatively mobile (Gautam et al., 2024a, b).

(iv) Mannans bind differently to glucans and the glucan-chitin complex in yeasts and filamentous ascomycetes. It is assumed that most yeast mannanoproteins are GPI-APs (GPI-anchored proteins). GPI anchors can have various modifications, but in fungi, they most often represent inositolphosphoceramide with two chains of fatty acids, connected through glucosamine and short mannan with either the C-terminus of the protein through phosphoethanolamine or without ethanolamine with galactomannan (in filamentous fungi; Tefsen et al., 2012; Komath et al., 2022; Guo & Kundu, 2024). The main function of the GPI anchor is to bind a glycoprotein or galactomannan to the plasma membrane by inserting ceramide fatty chains into the outer lipid layer of the membrane (

Figure 1C). However, many yeast GPI anchors serve to attach mannanoproteins through β-1,6-glucan to the β-1,3-glucan-chitin complex (Patel & Free, 2019; Gow & Lenardon, 2023). It is assumed that such a bond is formed through the binding of the first mannose (closest to glucosamine and phosphatidylinositol) with β-1,6-glucan (De Groot et al., 2005; Komath et al., 2022). It is unclear whether the glucosamine-inositol phosphoceramide residue is lost or remains in the mannanoprotein-glucan complex. In yeast, mannanoproteins can be PIR proteins and covalently bind through glutamine in their PIR repeats to β-1,3-glucans or through disulfide bridges in their cysteine-rich domains to other cell wall proteins (De Groot et al., 2005; Montano-Silva et al., 2024). In filamentous ascomycetes, GPI most often serves to anchor glycoproteins and non-protein-bound galactomannans to the plasma membrane. If glycoproteins are associated with the glucan-chitin complex, it is rarely through a PIR or GPI connection. Such a connection may occur through the terminal galactofuranose residues of short N- or O-galactomannans, which bind to the crosslinking glucan and, through it, to the glucan-chitin complex (Tefsen et al., 2012; Patel, Free, 2019; Gow, Lenardon, 2023).

(v) An important component of the outer layer of the cell wall of aspergilli is the aminopolysaccharide galactosaminogalactan (GAG). This is the most mobile polysaccharide of the cell wall. The GAG chain consists of residues of galactosamine, galactosamine acetate, and galactose with an α-1-4 bond (Fontaine et al., 2011; Chihara et al., 2020; Garcia-Rubio et al., 2020; Gautam et al., 2024a). The galactosamine residue often has a positive charge. By regulating the composition and quantity of GAGs in the outer layer, the fungus can alter the hydrophilic, adhesive, and other properties of its cell wall surface (Gautam et al., 2024a, b; Widanage et al., 2024). It has been shown that the amount of GAG in the cell wall increases with higher salinity in halotolerant aspergilli and is greater in germinating than in dormant conidia of A. fumigatus (Lamon et al., 2023; Fernando et al., 2023b).

The Structure of the Cell Wall in Filamentous Basidiomycetes

The cell wall of filamentous basidiomycetes has been studied less extensively than that of ascomycetes (

Figure 1B, C). There are classical and modern (ssNMR-based) studies on the structure of the cell wall of

Schizophyllum commune, and some data regarding the structure of the wall of

Pleurotus ostreatus (Sietsma, Wessels, 1977; Ehren et al., 2020; Safeer et al., 2023; Nakazawa et al., 2024). No fundamental differences from the cell wall of filamentous ascomycetes are shown, but there is still some dissimilarity. ssNMR analysis revealed that the internal rigid layer of the cell wall in

S. commune, like in ascomycetes, is represented by the α-1-3-glucan-chitin complex (Ehren et al., 2020; Safeer et al., 2023). The complex is crosslinked and embedded in a matrix of branched β-1-3/β-1-6-glucans, short linear β-1-3-glucans, and mannans (

Figure 1C). These same short and mobile glucans form the outer soft layer of the cell wall. In addition, short α-glucans and branched mannans are present in the outer layer. N-acetylgalactosamine and N-galactosamine were also detected here, which may indicate that the mobility and hydrophilicity of the outer layer of the wall, as in ascomycetes, can be regulated by changes in the content of aminopolysaccharides. An important feature of the cell wall of

S. commune (and other basidiomycetes) is the presence of fucans in the inner layer (Ehren et al., 2020; Safeer et al., 2023). It is possible that fucose replaces galactofuranose in basidiomycetes, but further research is needed. There is evidence of significant fucose presence in the cell walls of zygomycete fungi as well (Yugueros et al., 2024).

The Curtain Model and Mechanics of the Cell Wall

The concept of elastic strain of the cell wall (D) refers to the degree of rapid deformation of the cell wall under a certain force or pressure (Zhao et al., 2005; Municio-Diaz et al., 2022). For filamentous fungi, D is often estimated through the change in hyphal radius, expressed as a percentage: 100 x (R1 - R0)/R0, where R0 is the initial radius of the hypha before applying force, and R1 is the final radius after applying force (Atilgan et al., 2015; Davi et al., 2019; Municio-Diaz et al., 2022; Chevalier et al., 2023, 2024). Change in R is convenient to use to estimate D, first, because turgor is used simplistically as tensile pressure, neglecting other forces acting on the fungal hyphae, and turgor acts perpendicular to the cell surface; that is, the pressure vector coincides with the radius of the cell. Second, stretching of the cell wall along the long axis of the hypha can be neglected. It is assumed that the elasticity of the fungal cell wall is isotropic (the same along and across). Under such conditions, the change in the volume of an elongated cell is more influenced by changes in its radius than by its length (the volume of a cylinder linearly depends on its height and on the square of its radius). Therefore, as experimentally confirmed, the radius of an elongated fungal cell decreases twice as fast when the cell shrinks compared to its length (Atilgan et al., 2015; Municio-Diaz et al., 2022). In addition, the real hypha is most often adhered to the substrate, which means there is significant resistance to shrinkage-extension of the hypha along the longitudinal, but not transverse, axis. If we take the radius of the hypha Rr as R0, where the cell wall is in a completely relaxed state (zero turgor, no other acting forces), then D = 100 x (R1 - Rr)/Rr ~ (P x Rr)/(E x T). Here, P is turgor pressure (more precisely ∆P = P1-Pr, but Pr = 0), E is Young’s modulus or elastic modulus, and T is cell wall thickness. In other words, the extent to which the hypha expands and the radius it reaches (R1) will be directly proportional to the magnitude of turgor pressure and the thickness of the hypha itself, and inversely proportional to the elasticity of the cell wall. Of course, this dependence is relatively linear only within a certain range of P values. At high P values, the resistance of the cell wall material will slow down elongation; at values close to zero, it may also do so. Additionally, T (and possibly E) is not strictly constant and depends on the degree of rapid stretching of the wall (the more the elastic material is stretched, the thinner it becomes). Therefore, it is better to present the formula in a simplified form: D = 100 x (R1 - Rr)/Rr ~ (P x Rr)/(Er x Tr), where Er and Tr correspond to the elasticity of the relaxed wall. It should also be taken into account that R1 may be less than Rr. Under conditions of high hyperosmoticity, the protoplast tightly adheres to the cell wall, compressing it below the relaxation point (resulting in a state similar to negative turgor; Atilgan et al., 2015; Chevalier et al., 2023, 2024).

E represents the potential ability of the cell wall to elastically deform, depending on its structure, composition, degree of cross-linking and melanization, and other properties, calculated per unit cell wall thickness (Municio-Diaz et al., 2022; Chevalier et al., 2023, 2024). A higher E indicates a stiffer cell wall that is more difficult to deform (Lew & Nasserifar, 2009; Lew, 2019; Tsugawa et al., 2022). In fungi, E can vary from several MPa to several hundred MPa (Lew, 2019; Municio-Diaz et al., 2022). It should also be taken into account that both E and T values can change dynamically within a few minutes, especially in the apical cells of the hyphae (Chevalier et al., 2023). However, these changes are not associated with the physical stretching or compressing of the wall mentioned above but with fast physiological remodeling of the cell wall. This is exactly how the yeast cell wall thickens under hyperosmotic conditions – not just physical thickening of the wall occurs due to the removal of its stretching, but internal rearrangements of the glucan-chitin and mannan layers (Ene et al., 2015; Gow & Lenardon, 2023).

Let’s go back to the top of the formula (P x Rr)/(Er x Tr). The dependence of D on the size of the hypha itself (Rr) has not been unambiguously confirmed in real experiments. Our experiments showed that the average thickness of S. hirsutum hyphae is 1.4 times greater than that of C. comatus (Mazheika et al., 2024 preprint). The mycelium of both fungi shrinks by approximately 12-13% on average in Triton X-100. Triton X-100 treatment acts as an analogue of deflation assay: the protoplast is permeabilized, turgor is reset to zero, and the protoplast detaches from the cell wall, leading to its relaxation. Treatment with 0.6 M sorbitol results in the same shrinkage of S. hirsutum and C. comatus hyphae as in Triton X-100, indicating the same average turgor pressure in both fungi. If the hyphal radius had a directly proportional effect on D, the percentages of shrinkage and expansion in these fungi would differ. In the work of Chevalier and colleagues (2024), using a deflation assay on the apical cells of hyphae, there is also no correlation between D and R.

Finally, the curtain model allows for an important amendment to the formula. Due to the form-restraining function of actin, D will depend not only on turgor but also on the total force or resistance applied by the actin cytoskeleton to the cell wall. If actin is contractile and actively shrinks or expands the hyphae, it should refer to force (A). If actin holds the cell wall, resisting turgor, or supports the cell wall, preventing it from compressing when turgor drops, it should refer to resistance (Ars).

In contrast to turgor, A can be either positive or negative when R > Rr, depending on whether the actin cytoskeleton acts in the same direction as turgor or against it. Unlike turgor, A is a force generated by individual actin cables, not pressure. Its vector can be directed at different angles to the cell wall. Therefore, in addition to the projection perpendicular to the surface of the cell wall, expanding/shrinking the hypha as turgor does, A has projections of vectors directed parallel to the surface of the cell wall. Such vector projections stretch or compress the cell wall unevenly and in different directions. The effect of A on the cell wall will depend on the number of FACs/FASs. If, for simplicity, we consider only the perpendicular projections of A to the cell wall and disregard the discreteness of FACs/FASs, then formula D will take the following form: D ~ ((P + A/S) x Rr x k)/(Er x Tr). Here S is the area of the inner surface of the cell wall in μm2, and k is a reduction factor for Rr (since the actual effect of hyphal size on D is not so significant). A can be either positive or negative; if at A<0, |A/S|>P, the cell will shrink.

Ars should be placed at the bottom of the formula: D ~ (P x Rr x k)/((Er + Ars) x Tr)). Ars will be measured in MPa (N/μm²). Ars is an even more dynamic quantity than the elastic modulus, as the cell wall remodeling that leads to a change in E is clearly a slower process than the reorganization of actin cables.

Do Filamentous Fungi Have Instant Cell Wall Thickening Like Yeast?

For yeast cells, changes in the thickness of the cell wall during shrinkage or expansion play an important role; perhaps, as mentioned above, it is one variant of an airbag response to environmental variability (Ene et al., 2015; Gow & Lenardon, 2023). It is not known exactly whether the thickness and structure of the cell wall change in the first minutes of hyperosmotic shock in filamentous fungi. Due to the relatively small thickness of the cell wall compared to the diameter and size of the hyphae, such changes are difficult to detect using conventional light microscopy. There is only information that the inner side of the cell wall, in contact with the periplasmic space, is loosened (

Figure 1B; Mazheika et al., 2020a). Additionally, Chevalier et al. (2023), using a “sandwich” of two fluorophores, demonstrated that the wall thickness in the apical cell of

A. nidulans can change rapidly. However, there is no data on the relationship between hyperosmotic shock and wall thickness. A TEM study of

A. nidulans showed that in a hypertonic environment, thickening of the cell wall does not occur (Zhao et al., 2005). However, the authors grew mycelium in a medium with high osmolarity and did not add an osmotic agent immediately before analysis, allowing the fungus time to adapt to hypertonic conditions. In contrast, Fernando and colleagues (2023b) demonstrated that in halotolerant

Aspergillus, the thickness of the cell wall during mycelial growth on 2 M sodium chloride increases almost 1.5 times compared to growth on 0.5 M salt, largely due to the outer mobile layer of the wall. However, this is not about instant changes in the fungal cell when the external environment’s osmolarity changes, but rather about gradual adjustment to conditions during growth. In any case, halotolerant aspergilli, like ascomycete yeasts, do not have α-1-3-glucans in the rigid layer of the cell wall. It is possible that in fungi with β-1-3-glucans in the inner layer, as the main linear polymer forming a complex with chitin, the cell wall can thicken more rapidly than in fungi with α-1-3-glucans due to the greater rigidity of the latter compared to β-1-3-glucans. We hypothesize that in filamentous fungi, the rapid wall thickening in response to hyperosmotic shock is not as pronounced as in yeast. Some changes in thickness and composition occur; as mentioned, cell expansion or shrinkage is accompanied by a change in wall thickness, but the mechanisms of airbags in filamentous fungi are different.

The Cell Wall as a Curtain Rod of the Curtain Model

The next section will discuss some variants of the curtain model. In one case, FACs/FASs are universal elements and should move comparably freely along the inner surface of the cell wall under the control of actin cables, similar to rings on a curtain rod. For such a mechanism to work, not only are certain properties of FACs required (discussed in the next section), but an appropriate cell wall structure is also necessary. It can be assumed that basidiomycetes and other filamentous fungi have an additional innermost sublayer of the cell wall. Under hyperosmotic conditions, this layer loosens and is carried away by the adhesive bonds of the membrane and wall during hypha shrinkage. It is possible that in this sublayer, glucan fibrils have few crosslinks and branches, facilitating the sliding of protein domains responsible for adhesion (see CW3 in

Figure 1C).

Component III: Plasma Membrane Adhesion to the Cell Wall

Plasmolysis and Changes in Cell Size with Changes in Osmotic and Other Conditions

Mycological studies indicate that the fungal plasma membrane is firmly adhered to the cell wall, making plasmolysis (detachment of the plasma membrane from the cell wall, such as in a hyperosmotic environment) more difficult to achieve than in plants (Walker, White, 2017). This is confirmed by the overestimation of turgor measurements using the method of primary (incipient) plasmolysis compared to direct measurement methods (Heath, Steinberg, 1999; Lew et al., 2004). In addition, turgor measurements using a deflation assay are indicative in this regard. The shrinkage of a fungal cell at high osmolarity levels of the medium is often twice as high (in radius) as the shrinkage of a perforated cell (microdamaged by laser; Atilgan et al., 2015; Chevalier et al., 2024). This may mean that the protoplast tightly adhered to the cell wall, shrinking under hyperosmotic conditions, drags the cell wall with it, compressing it further relative to the wall relaxed state. However, other interpretations of this effect are possible. For example, the hydrophobic polysaccharide matrix of the cell wall can itself compact under hyperosmotic conditions.

In the cells of higher plants during hyperosmotic shock, various types of plasmolysis are possible (see Oparka, 1994). In any case, the protoplast gradually detaches from the cell wall, shrinking but remaining connected to the wall through thin Hechtian strands and wider connections—the Hechtian reticulum. These connections to the cell wall are permeated with actin cables (Hechtian strands) and microtubules (Hechtian reticulum). The connection involves the cortical endoplasmic reticulum, and the connection with the cell wall occurs through FACs/FASs. Shrinkage of the protoplast can take several tens of minutes. The cell wall usually does not change its size significantly, at least in cells connected into tissue (Morris et al., 1986; Oparka, 1994; Cheng et al., 2017).

Under hyperosmotic conditions, fungi exhibit different responses. First, the fungal cell rapidly shrinks, including the cell wall, within seconds to a few minutes (Morris et al., 1986; Lew & Nasserifar, 2009; Mazheika et al., 2024 preprint). A yeast cell can lose up to 70% of its volume, resulting in a decrease in cell diameter by approximately 20-40%, depending on the cell’s shape. At the same time, the thickness of the yeast cell wall can rapidly increase, as described earlier (Morris et al., 1986; Slaninova et al., 2000; Atilgan et al., 2015; Ene et al., 2015; Elhasi & Blomberg, 2019; Gow & Lenardon, 2023). In filamentous fungi, the diameter of hyphae under moderate osmotic shock decreases by 10-25%. These values are derived from experimental data from two publications for several species of fungi and specific concentrations of osmolytics. For other species and hyperosmotic conditions, different shrinkage values may occur (Lew, Nasserifar, 2009; Mazheika et al., 2024 preprint). Other studies have measured the shrinkage of apical cells in several species of filamentous fungi (mainly ascomycetes) at different medium osmolarity levels (Chevalier et al., 2023, 2024). The reduction in radius reaches about 40%, but it is difficult to determine whether this result will apply to non-apical hyphal cells.

Second, plasmolysis in fungi under moderate osmotic shock occurs rarely and only in individual cells. However, if it does occur, it is usually faster than in plants. Fungi lack analogues of Hechtian strands. In cases of concave-type plasmolysis (see Oparka, 1994), the plasma membrane remains connected to the cell wall at distinct points, likely some FACs/FASs, which are more or less evenly distributed along the cell’s perimeter. Between these points, the membrane detaches from the cell wall (Mazheika et al., 2020a; Mazheika et al., 2024 preprint). Fungal plasmolysis strongly depends on environmental conditions, the state of the cell, and can be species-specific. For example, in S. hirsutum, if the mycelium grown on an agarized nutrient medium is not immediately placed in a hyperosmotic liquid medium (with 0.6 M sorbitol), but after preincubation in the same growth medium without agar, then the probability of concave plasmolysis increases (Mazheika et al., 2024 preprint). This is likely because the pressure (cytoplasmic osmolarity) in aerial hyphae coated with hydrophobins, which are part of a colony growing on a solid medium, is higher than in hyphae immersed in liquid or agar gel, even if the composition of the solid and liquid nutrient media is the same (the only difference being the agar). Another example: it turned out that R. solani has its own mechanism for quickly responding to a nonequilibrium change in conditions. In this fungus, under moderate hyperosmotic stress, rapid concave plasmolysis occurs in many cells, but within ten minutes after being placed in a hyperosmotic environment, the protoplast restores its shape (Mazheika et al., 2024 preprint).

What Is the Mechanism of Tight Adhesion between the Plasma Membrane and the Cell Wall in Fungi?

In animal cells, the plasma membrane adheres to the ECM (extracellular matrix) using receptor proteins collectively called integrins. These are heterodimeric transmembrane proteins, whose outer domains bind with affinity to various ECM ligands, while the cytoplasmic domains are associated with actin through adapter proteins (such as talin). In the activated state, integrins cluster in the plasma membrane in focal adhesion complexes (FACs) and form focal adhesion sites (FASs). Depending on the adhesion force, the size and frequency of adhesive complexes will vary, up to fibrillar adhesion (Elhasi & Blomberg, 2019; Kechagia et al., 2019). In fungi, homologs of integrins are not found (there are only short regions of homology), but it is assumed that there are integrin-like proteins that also provide FACs/FASs. Confirmation of the existence of integrin-like proteins is indirect – it has been shown that in some fungi and oomycetes, antibodies to animal integrins give a positive signal; RGD peptides can act on fungi (they inhibit signal transduction and adhesion in animal cells since RGD is a common motif in ligands to which integrins bind) (Kaminskyj & Heath, 1995; Heath & Steinberg, 1999; Chitcholtan & Garrill, 2005; Elhasi & Blomberg, 2019).

It is assumed that in fungi, the functions of integrins can be performed by various mechanosensors, which are the initial step of the CWI pathway (Elhasi & Blomberg, 2019). Several types of cell wall mechanosensors are known in yeasts and filamentous ascomycetes. The main ones are Wsc- and Mid-type mechanosensors and signaling mucins (Yoshimi et al., 2022). Most often, the mechanosensors consist of an extracellular domain embedded in the cell wall, a transmembrane domain, and a short intracellular domain. The extracellular domain is highly O-glycosylated, and in some sensors, it is also N-glycosylated. In other words, the sensory domain is similar to a brush inserted between cell wall fibrils, where branched bristles (O- and N-glycans) interact with glucans and mannanoproteins of the cell wall (see Mech and Mech-FAC in

Figure 1C, D). Typically, extracellular domains contain serine- and threonine-rich regions, which act as nanosprings, compressing and stretching under the influence of forces arising from perturbations in the cell wall. The signal is transmitted to the cytoplasmic tail of the sensor, which changes its conformation. Then, Rho1 GTPase is activated, and various CWI pathways are launched (Kock et al., 2015; Elhasi & Blomberg, 2019; Yoshimi et al., 2022; Gow & Lenardon, 2023). Elhasi and Blomberg (2019) indicate that yeast Wsc1 is associated with F-actin through a protein complex involving Sla1 and Sla2. It is likely that Wsc1 is responsible for the disassembly of actin cables during osmotic shock or cell wall destruction. The Sla1/Sla2 complex functions analogously to human talin (notably, chytrid fungi have actual homologues of talin; Prostak et al., 2021). Hinze and Boucrot (2018) suggest that Sla1 and Sla2 are homologues of the human F-BAR proteins intersectin and Hip1/R, respectively. In clathrin-dependent endocytosis in animals and yeast, they regulate actin assembly in pits/patches. In

S. pombe, Sla2 is involved in the polar organization of actin during cytokinesis (Castagnetti et al., 2005). Fungal Sla2, animal Hip1/R, and talin belong to the same superfamily of actin-binding proteins that have an I/LWEQ module at the C-terminus. This module in talin is responsible for binding with F-actin; without it, focal adhesion is impossible (Smith, McCann, 2007). It is likely that Sla1 mimics the N-terminus of talin, which contains domains that bind to the inner side of the plasma membrane and integrins. Accordingly, actin, through adapter proteins like Sla1/Sla2, can cluster mechanosensors in the plasma membrane into FACs, ensuring focal adhesion at specific membrane sites. Indeed, in yeast, it has been shown that Wsc1 is often clustered in the plasma membrane (

Figure 1C, D; Heinisch et al., 2010). Moreover, due to the transmembrane domains of mechanosensors (or other proteins) clustered in the plasma membrane, when such a cluster is moved by actin along the cell wall, lateral resistance of the lipid bilayer is created, enabling changes in membrane tension. Evidence suggests that in

A. nidulans strains deficient in WscA (a homolog of yeast Wsc1), cells swell more often under hyperosmotic conditions (Futagami et al., 2011). This result may indicate that actin in

A. nidulans performs the form-restraining function through WscA-FACs. Unfortunately, cell wall mechanosensors in filamentous basidiomycetes have not been practically studied. In

Ustilago maydis and

Cryptococcus neoformans, only signaling mucins are known as mechanosensors (Yoshimi et al., 2022).

Different Variants of the Curtain Model, Differing in the Mechanism of Interaction between Actin, the Plasma Membrane and the Cell Wall

In accordance with the curtain model (with one of its variants), FACs/FASs should slide along the inner surface of the cell wall. This means that the variant with animal integrins, which have affinity bound to ECM ligands, is not suitable for fungi because the strength of the affinity bond is difficult to regulate. A strong bond will not allow FACs/FASs to be motile, and even a weak affinity bond is specific to its ligand—once detached, the protein will lose contact with the cell wall. Fungal mechanoreceptors or other adhesive proteins must be connected to the inner layer of the cell wall or the special sublayer, as described in previous sections, by bonds similar to hydrophobic ones – weak and with little specificity. If the mechanosensor brush of O- and N-glucans does not form covalent bonds with the glucan fibrils of the cell wall, it can provide strong fixation (perpendicular to the wall fibrils) but remain mobile (parallel to the fibrils) within the cell wall.

A different variant for organizing FACs/FASs is possible (

Figure 1D). As described above, in filamentous fungi, some cell wall proteins and non-protein-bound mannans are associated with the plasma membrane through GPI anchors (Tefsen et al., 2012; Komath et al., 2022; Guo, Kundu, 2024). In animal cells, there is a model for the formation of lipid rafts where actin interacts with phosphatidylserine located in the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane through adapter proteins. Actin clusters phosphatidylserine, which interacts in the middle of the lipid bilayer through its long saturated fatty acid chains with chains of GPI-APs. As a result, GPI-APs and glycosphingolipids cluster in the outer leaflet of the membrane, forming lipid rafts (Saha et al., 2016; Komath et al., 2022). In animal cells, the clustering of GPI-APs does not have mechanical functions; instead, it regulates various properties of the plasma membrane and is involved in transmitting signals into the cell (Saha et al., 2016). However, in fungi, it is possible to form GPI-FACs that correspond to the characteristics of the curtain model if the lateral resistance of the lipid bilayer to the movement of the GPI-APs cluster by actin is sufficient to regulate membrane tension. Interestingly,

N. crassa has a specific cell wall mechanosensor, HAM-7, which lacks the typical transmembrane and intracellular domains but is inserted into the plasma membrane via a GPI anchor (Maddi et al., 2012).

Finally, another variant for the curtain model is possible. Until now, we have accepted that actin performs both the regulation of membrane tension and the form-restraining function through the same FACs/FASs. However, this may not be the case. It is possible that actin changes or maintains cell size by interacting with the cell wall through proteins of FACs/FASs (mechanoreceptors or GPI-APs). In this scenario, FACs/FASs proteins may not be mobile and could even be anchored in the cell wall by covalent bonds. At the same time, actin can regulate the tension of the plasma membrane by interacting with plasma membrane proteins not associated with the cell wall. These proteins likely cluster in the plasma membrane to create sufficient resistance to the lipid bilayer and ensure its tension under the action of actin (

Figure 1D, right side).

In addition, the strong adhesion of the plasma membrane to the cell wall and the rarity of plasmolysis in fungi may be ensured not only by FACs/FASs. Single adhesion proteins can be distributed between clusters of actin-associated mechanosensors and GPI-APs. They are not necessarily actin-associated and are not directly involved in regulating membrane tension or maintaining cell shape. They provide additional adhesion that prevents membrane detachment from the cell wall between FASs under moderate osmotic stress (see GPI-glucan in

Figure 1C).

Component IV: Plasma Membrane Macroinvagination Systems

Macroinvaginations and Endocytosis

In both plants and yeast, as well as filamentous fungi, invaginations of the plasma membrane form during osmotic shock and other stresses. In a number of fungi, these invaginations are a permanent feature of the cells (Morris et al., 1986; Oparka, 1994; Slaninova et al., 2000; Bitsikas et al., 2011; Ene et al., 2015; Elhasi, Blomberg, 2019; Mazheika, Kamzolkina, 2021; Mazheika et al., 2022). It does not matter whether the entire cell shrinks, as in fungi, or just the protoplast, as in plants, but when the cell or protoplast volume rapidly decreases, the excess plasma membrane must be structurally packaged to avoid membrane damage and maintain the functionality of the remaining unpacked membrane. Such packaging is provided by special structures, in some cases having a rather complex organization, known as plasma membrane invaginations, or more accurately, macroinvaginations. Their sizes can range from a couple of hundred nanometers to tens of micrometers, differentiating them from fungal endocytic pins, which rarely exceed 100 nm (Mazheika, Kamzolkina, 2021). Macroinvaginations also differ from endocytic pins in their negative rather than positive connection with actin (depolymerization of actin often stimulates the formation of macroinvaginations rather than blocking them) and their ambiguous connection with endocytosis (see below; Oparka, 1994; Yamashita and May, 1998; Lee et al., 2007; Upadhyay and Shaw, 2008; Lewis et al., 2009; Mazheika et al., 2020a, 2022). Many authors on plants and fungi have found that the lumen of macroinvaginations is labeled with calcofluor or primulin, and in TEM, macroinvaginations may contain material similar to cell wall material (Oparka, 1994; Slaninova et al., 2000; Elhasi, Blomberg, 2019). Previously, it was assumed that macroinvaginations are invaginations of the cell wall itself into the cell (Morris et al., 1986). In fact, as discussed earlier, this phenomenon is a consequence of the tight adhesion of the plasma membrane to the cell wall (the shrinkting protoplast draws the loosening inner layer of the cell wall, pulling the wall material into a macroinvagination). However, it cannot be ruled out that during a strong hyperosmotic shock, when the cell wall surpasses its relaxed state and begins to shrink further along with the protoplast, the cell wall deforms, and its excess can actually protrude into the cell.

The relationship between endocytosis and macroinvaginations remains unclear (Mazheika, Kamzolkina, 2021). Early studies on plants assumed that macroinvaginations, after turgor restoration and deplasmolysis, are severed from the plasma membrane but may not follow the classical endocytotic path of merging with endosomes and vacuoles (Oparka, 1994). A separate term for this process – osmocytosis – was even proposed (Robinson, Milliner, 1990). Using time-lapse video and labeling of the mycelium of S. hirsutum and other xylotrophic basidiomycetes with AM4-64 (a styryl fluorophore, an analogue of FM4-64, which embeds in the lipid bilayer of the plasma membrane), it was shown that macroendocytosis occurs. The mechanism is evidently different from macropinocytosis in animals, justifying the introduction of a separate term. However, this process is infrequent; it occurs only with certain types of macroinvaginations, and the further fate of the detached membrane structure is unknown (Mazheika et al., 2022).

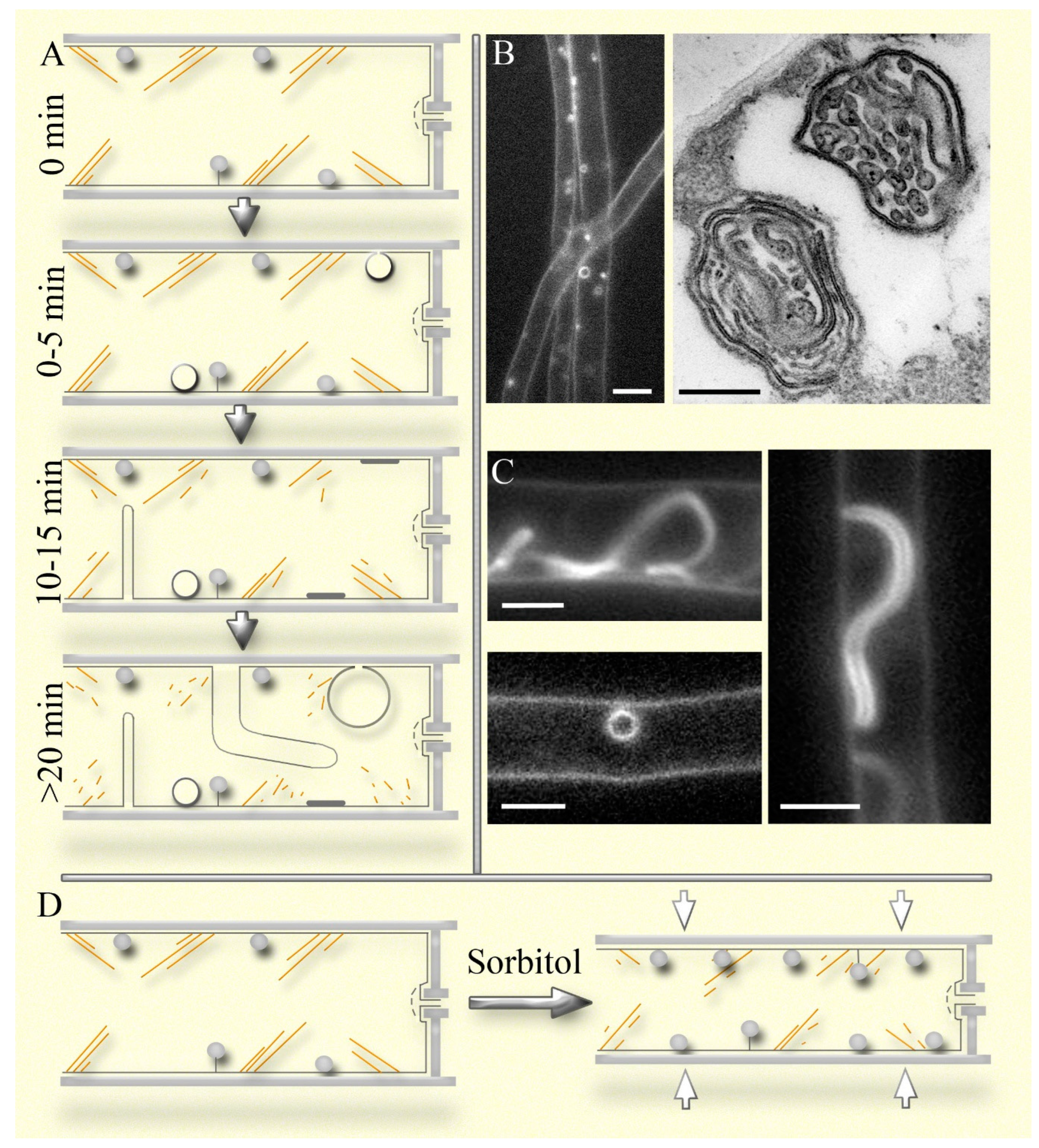

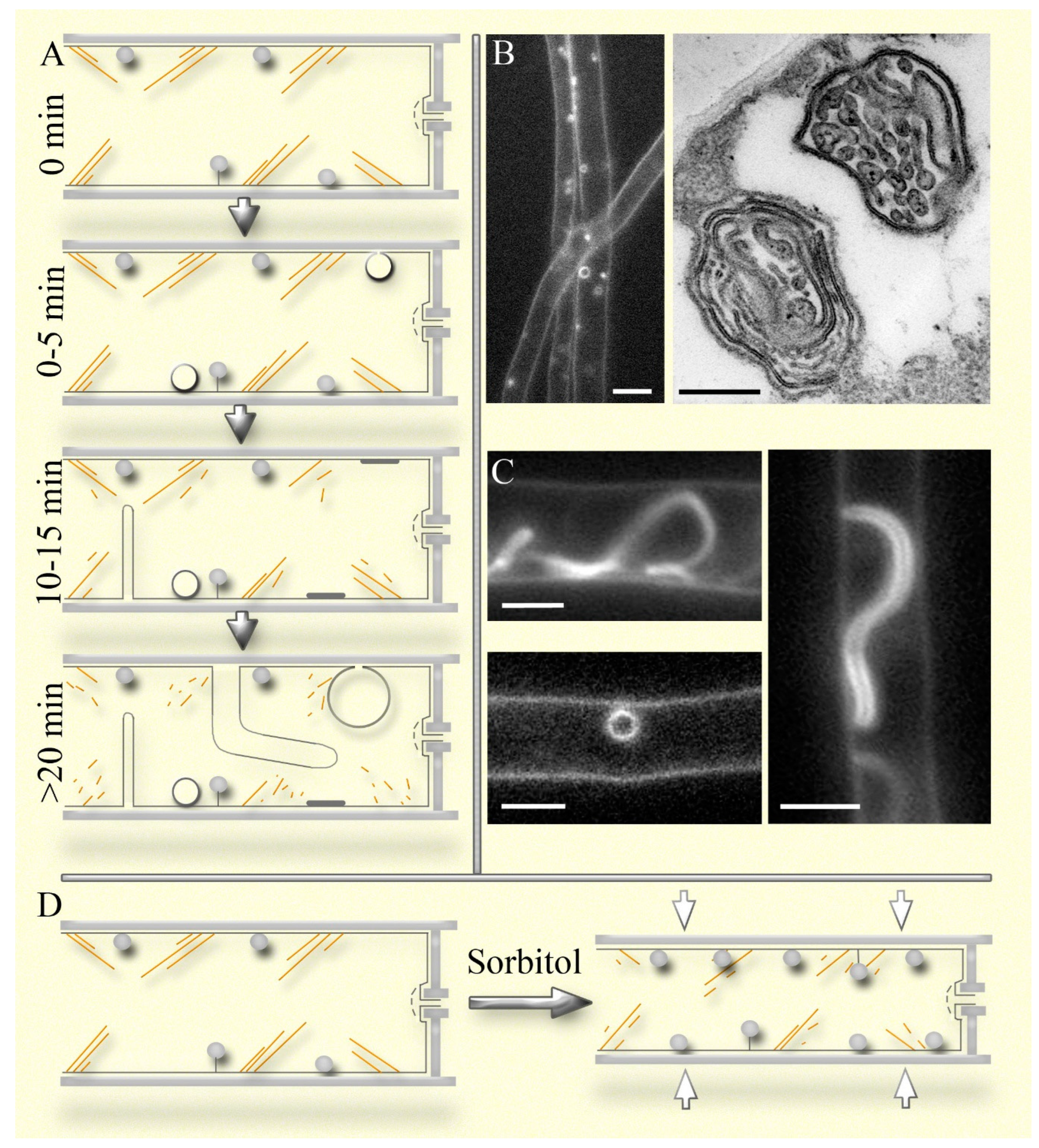

In our earlier works, we mistakenly identified different types of AM4-64-labeled macroinvaginations as structures representing various steps in the endocytic pathway (Kamzolkina et al., 2017; Mazheika et al., 2020a, b). Small parietal dense lomasomes (different types of macroinvaginations are described in Mazheika et al., 2022;

Figure 2; also see below) resemble endocytic pins, small vesicles and focal sections through transverse thin tubes resemble endosomes, while large vesicular macroinvaginations and focal sections through thick tubes resemble vacuoles, into which endosomes delivered AM4-64. The similarity with the endocytic pathway is enhanced by the gradual appearance of the listed types of macroinvaginations on a microscopic slide: for example, lomasomes are labeled immediately, and thick tubular and large vesicular macroinvaginations appear about twenty minutes after the preparation of the sample (

Figure 2A; Mazheika et al., 2022). This phenomenon is due to the stressful conditions in which the microscopic sample is located: a thin layer of liquid, mechanical impact of the cover glass, gradual drying, etc. Most likely, disassembly or remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton begins in the microscopic specimen mycelium (

Figure 2A). This is why the use of latrunculin A does not affect the formation of late large macroinvaginations (as F-actin is already disassembled at this stage) but significantly affects early ones, as previously described. However, large macroinvaginations should not be classified as artifacts. The stressful conditions of the microscopic specimen are not unique; the fungus likely encounters similar conditions in nature, which means it forms large macroinvaginations not only in a laboratory. Moreover, the presence of macroinvaginations and their imitation of the endocytic pathway does not mean that fungi lack true endocytosis in non-apical cells. It was shown that among the large vacuole-like macroinvaginations labeled with AM4-64, VLCs (vacuole-lysosome candidates) were found (Mazheika et al., 2022). They have a weaker AM4-64 signal than macroinvaginations, and some are co-labeled with CFDA (vacuolar probe). There are 13 times fewer VLCs than large macroinvaginations and 60 times fewer than large vacuoles in the hyphae of

S. hirsutum. This result indicates that the vacuolar system of fungi, under normal conditions, is only minimally involved in degrading substances from the outside and the plasma membrane by endocytosis. However, this situation likely changes if mass autophagy is triggered in the hyphae.

Two Types of Macroinvagination Systems in Fungi

Plasma membrane macroinvaginations in fungi can vary, but during formation, they all progress through a stage involving a tube or lamella of varying thickness (ranging from a thin filament or lamella of several tens of nanometers to a tube more than a micrometer thick; Mazheika et al., 2022). We distinguish two types of macroinvagination systems in fungi: simple and complex. Previously, we did not differentiate between the concepts of the two systems of macroinvaginations and the two types of fungal endocytosis—classical endocytosis and macroendocytosis (Mazheika et al., 2020a, b). The simple macroinvagination system is characteristic of yeasts, filamentous ascomycetes, and some basidiomycetes, such as

R. solani. In this system, macroinvaginations are not large: tubes or lamellae usually do not exceed five µm in length, and rounded macroinvaginations rarely exceed half a micrometer in diameter (Mazheika et al., 2020a). Secondary invagination in macroinvaginations (formation of true lomasomes) is rare. In xylotrophic basidiomycetes (and likely in mycorrhizal basidiomycetes, though no data is available), the system of macroinvaginations is complex. They exhibit up to seven different types of macroinvaginations (

Figure 2A-C: Mazheika et al., 2022). The most common type is small parietal macroinvaginations that lack a lumen when fluorescently labeled; they appear as small dense balls pressed against the plasma membrane or attached to the membrane by a filamentous tube or lamella (

Figure 2A, B). At the electron microscopic level, they have a complex internal structure, typically consisting of secondary invaginations in the form of lamellae and tubes that fill the lumen of the primary invagination (

Figure 2B, right side). These are classic fungal lomasomes (Moore, McAlear, 1961; Brushaber, Jenkins, 1971; Mazheika, Kamzolkina, 2021). Lomasomes are always present in the cells of xylotrophs, at least when the hypha is in an aquatic environment. In an airy or low-moisture environment, they may be absent or few, but this remains an open question. During moderate hyperosmotic shock or actin depolymerization, their number increases, under certain conditions up to five times, and can reach up to fifty lomasomes per cell (

Figure 2D; Mazheika et al., 2022). In xylotrophs, it is likely that lomasomes, and to a lesser extent other macroinvaginations, are the main components of the curtain model. They form new lomasomes instantly and increase the size and complexity of existing ones with slight cell shrinkage, while disbanding lomasomes during the equilibrium expansion of the hyphae. The disbandment occurs as follows: lomasomes are stretched into flat plaques – the primary invagination turns inside out, exposing the internal secondary invaginations into the periplasmic space (Mazheika et al., 2022). Lomasomes also function as elements of airbags during strong osmotic changes. However, other types of macroinvaginations are involved, which are structurally less complex than lomasomes but can quickly deposit or release a significant surface area of the plasma membrane due to their size.

Figure 2.

The system of macroinvaginations as a component of the curtain model using the example of S. hirsutum. A – sequential appearance of different types of macroinvaginations in a microscopic specimen depending on the observation time. Small dense macroinvaginations – lomasomes (shown as gray balls without a lumen) – residents of the fungal cell; later, small vesicular macroinvaginations appear in the preparations (shown as hollow spheres). Many small vesicles are actually short transverse tubes or rolls. Ten to fifteen minutes after the start of observation, thin (<1 µm in diameter) invagination tubes appear in some cells. Thick tubes (>1 µm in diameter) and large invaginated vesicles (>2 µm) can be observed in individual cells not earlier than 20 minutes, which can be confused with vacuoles. The yellow lines indicate actin cables, which presumably disassemble upon long-term observation of the specimen. B, C – fluorescent (labeling with FM4-64 analogue) and electron microscopic photographs of different types of macroinvaginations, corresponding to the images in panel A. In the TEM photograph, the slice passed through two classic tubular-lamellar lomasomes. Fragments of photographs taken from Mazheika et al., 2022. Scale bar 5 µm (except TEM photo – 0.2 µm). C – it is shown how the hypha of S. hirsutum shrinks in a moderate hyperosmotic environment, while the number of lomasomes increases by 2-3 times, and F-actin is possibly depolymerized.

Figure 2.

The system of macroinvaginations as a component of the curtain model using the example of S. hirsutum. A – sequential appearance of different types of macroinvaginations in a microscopic specimen depending on the observation time. Small dense macroinvaginations – lomasomes (shown as gray balls without a lumen) – residents of the fungal cell; later, small vesicular macroinvaginations appear in the preparations (shown as hollow spheres). Many small vesicles are actually short transverse tubes or rolls. Ten to fifteen minutes after the start of observation, thin (<1 µm in diameter) invagination tubes appear in some cells. Thick tubes (>1 µm in diameter) and large invaginated vesicles (>2 µm) can be observed in individual cells not earlier than 20 minutes, which can be confused with vacuoles. The yellow lines indicate actin cables, which presumably disassemble upon long-term observation of the specimen. B, C – fluorescent (labeling with FM4-64 analogue) and electron microscopic photographs of different types of macroinvaginations, corresponding to the images in panel A. In the TEM photograph, the slice passed through two classic tubular-lamellar lomasomes. Fragments of photographs taken from Mazheika et al., 2022. Scale bar 5 µm (except TEM photo – 0.2 µm). C – it is shown how the hypha of S. hirsutum shrinks in a moderate hyperosmotic environment, while the number of lomasomes increases by 2-3 times, and F-actin is possibly depolymerized.

Non-Equilibrium States Not Controlled by the Curtain Model, Examples of the Airbags

In the equilibrium state in cells with low or moderate turgor, actin regulates plasma membrane tension and provides a framework that prevents the cell from quickly changing its size during small shifts in osmolarity. Additionally, the actin cytoskeleton, along with other components of the curtain model, likely aligns the hypha along its axis if there are different turgor pressures in different parts. Actin may also participate in creating mass flow inside the hyphae. However, everything changes with a non-equilibrium shift in external conditions: a sharp change in the osmolarity of the substrate, rapid drying or watering of the substrate, the transition of the hypha from the aqueous to the air phase or vice versa, mechanical stress, aggressive influence of the host or competitor, etc. Since such changes can occur frequently and all can lead to a sharp change in osmotic pressure, the fungus needs not only to avoid cellular damage but also to minimize the period during which it loses physiological functionality. In this regard, all fungi, from ascomycete yeast to basidiomycetes, have adopted a single general strategy: with osmotic changes or alterations in the permeability of the plasma membrane, they instantly change the diameter of the hyphae (or yeast cell). Consequently, the cell changes its volume as a whole – the cell wall along with the protoplast (Morris et al., 1986; Lew, Nasserifar, 2009; Atilgan et al., 2015; Chevalier et al., 2024; Mazheika et al., 2020a, 2024 preprint). In conjunction with this, the plasma membrane forms macroinvaginations to maintain its integrity and functionality (Mazheika et al., 2022). However, within the general strategy, different groups of fungi have their own specific protective mechanisms. These “airbags,” as we called them above, are structural-physiological defense mechanisms that are the first to respond to stress and prevent cell damage in the initial seconds or minutes of shock exposure. In yeast, an important element of the airbag is the cell wall itself, which can be structurally rearranged quickly and significantly change its thickness (more than with just physical compression of the wall), reducing the risk of damage to the protoplast during cell shrinkage or expansion (Morris et al., 1986; Slaninova et al., 2000; Atilgan et al., 2015; Ene et al., 2015; Elhasi, Blomberg, 2019; Gow, Lenardon, 2023).