Submitted:

12 September 2024

Posted:

14 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- What are the key criteria that influence the social sustainability of urban parks in Konya, Turkey?

- How do these criteria impact social sustainability in these spaces?

2. Methodology

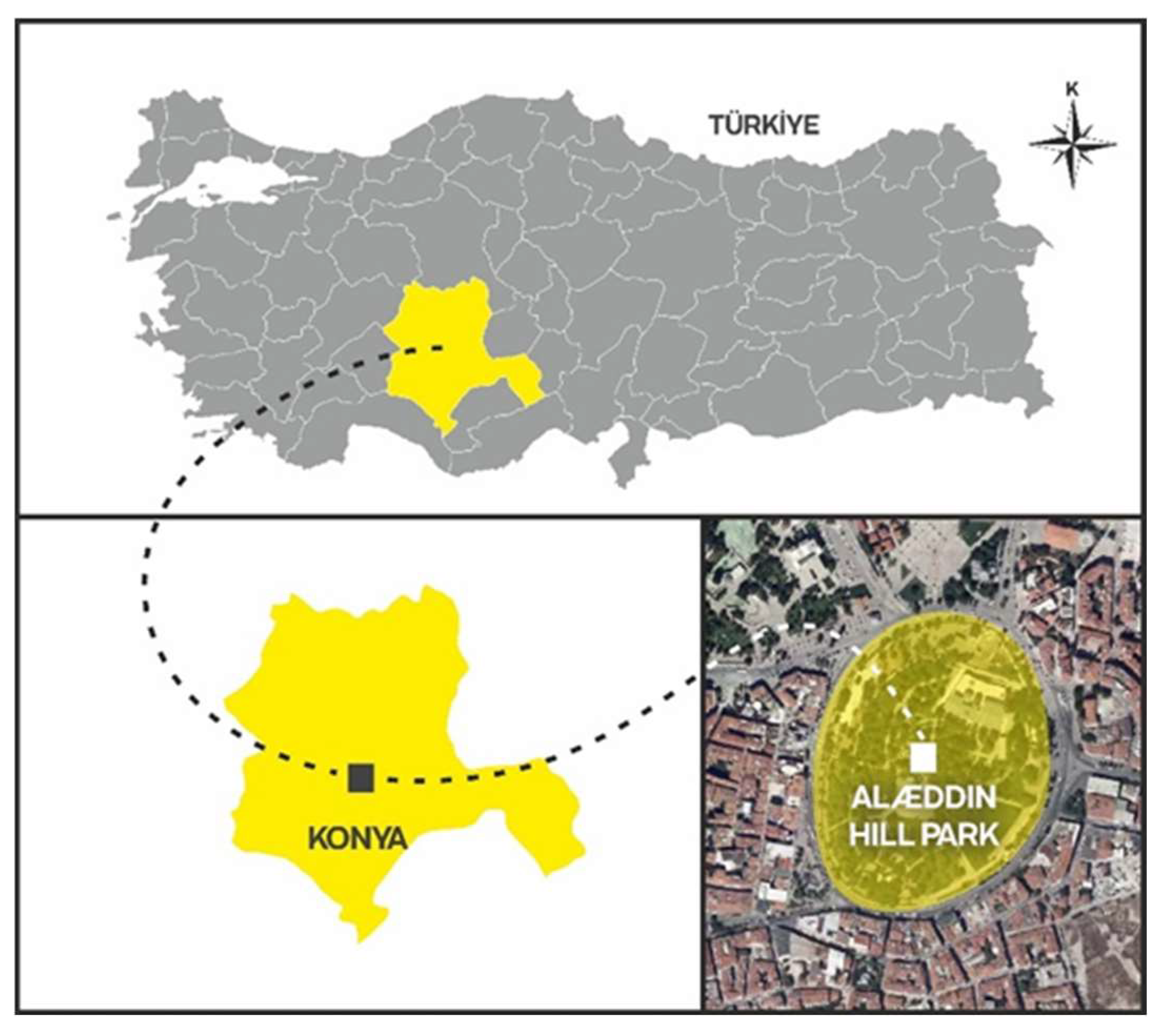

2.1. Case Study

2.2. Data and Sampling

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Jeannotte, M.S. Singing alone? The contribution of cultural capital to social cohesion and sustainable communities. The International Journal of Cultural Policy 2003, 9, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Landorf, C. Evaluating social sustainability in historic urban environments. International Journal of Heritage Studies 2011, 17, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talan, A.; Tyagi, R.; Surampalli, R.Y. Social dimensions of sustainability. Sustainability: Fundamentals and Applications, 2020: P. 183-206.

- Gehl, J. Cities for people. 2013: Island press.

- Talen, E. Measuring the public realm: A preliminary assessment of the link between public space and sense of community. Journal of architectural and planning research, 2000: P. 344-360.

- Dempsey, N.; et al. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustainable development 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, E. The compact city: Just or just compact? A preliminary analysis. Urban studies 2000, 37, 1969–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, S. Social sustainability: Towards some definitions. 2004.

- Barron, L.; Gauntlett, E. Stage 1 report-model of social sustainability. Housing and Sustainable Communities’ Indicators Project. Perth, Murdoch University, Western Australia, 2002.

- Polèse, M.; Stren, R.E.; Stren, R. The social sustainability of cities: Diversity and the management of change. 2000: University of Toronto press.

- Davidson, K.; Wilson, L. A critical assessment of urban social sustainability. In Proceedings of the 2009 4th State of Australian Cities National Conference, 24-27 November 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Partridge, E. Social sustainability’: A useful theoretical framework. in Australasian political science association annual conference. 2005.

- Holden, M. Urban policy engagement with social sustainability in metro Vancouver. Urban Studies 2012, 49, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, K. The social pillar of sustainable development: A literature review and framework for policy analysis. Sustainability: Science, practice and policy 2012, 8, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.; Lee, G.K. Critical factors for improving social sustainability of urban renewal projects. Social indicators research 2008, 85, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littig, B.; Griessler, E. Social sustainability: A catchword between political pragmatism and social theory. International journal of sustainable development 2005, 8, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, H.; Gülersoy, N.Z. Developing Social Sustainability Criteria and Indicators in Urban Planning: A Holistic and Integrated Perspective. ICONARP International Journal of Architecture and Planning, 2023.

- Ghahramanpouri, A.; Lamit, H.; Sedaghatnia, S. Urban social sustainability trends in research literature. Asian Social Science 2013, 9, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvi, H.; et al. Cultivating Community: Addressing Social Sustainability in Rapidly Urbanizing Hyderabad City, Pakistan. Societies 2024, 14, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyedi, G. Social sustainability of large cities. Ekistics, 2002: P. 142-144.

- Shrivastava, V.; Singh, J. Social sustainability of residential neighbourhood: A conceptual exploration. International Journal of Emerging Technologies 2019, 10, 427–434. [Google Scholar]

- Karuppannan, S.; Sivam, A. Social sustainability and neighbourhood design: An investigation of residents' satisfaction in Delhi. Local Environment 2011, 16, 849–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafieian, M. Evaluation of social sustainability in urban neighbourhoods of Karaj city. Iran University of Science & Technology 2014, 24, 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- Dave, S. Neighbourhood density and social sustainability in cities of developing countries. Sustainable development 2011, 19, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, D.C.W.; et al. Social sustainability in urban renewal: An assessment of community aspirations. Urbani izziv 2012, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.S.; Siu, Y.F.P. Urban governance and social sustainability: Effects of urban renewal policies in Hong Kong and Macao. Asian Education and Development Studies 2015, 4, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darchen, S.; Ladouceur, E. Social sustainability in urban regeneration practice: A case study of the Fortitude Valley Renewal Plan in Brisbane. Australian Planner 2013, 50, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantonio, A. Urban social sustainability themes and assessment methods. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Urban Design and Planning 2010, 163, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramley, G.; Power, S. Urban form and social sustainability: The role of density and housing type. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 2009, 36, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, J.; Dillard, J. Social sustainability: An organizational-level analysis, in Understanding the social dimension of sustainability. 2008, Routledge. p. 173-189.

- Glasson, J.; Wood, G. Urban regeneration and impact assessment for social sustainability. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 2009, 27, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Domesticated nature: Motivations for gardening and perceptions of environmental impact. Journal of environmental psychology 2007, 27, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Smith, L.D.G.; Weiler, B. Relationships between place attachment, place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviour in an Australian national park. Journal of Sustainable tourism 2013, 21, 434–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.S.; Chan, E.H. Building Hong Kong: Environmental Considerations. Vol. 1. 2000: Hong Kong University Press.

- Moulay, A.; Ujang, N.; Said, I. Legibility of neighborhood parks as a predicator for enhanced social interaction towards social sustainability. Cities 2017, 61, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavik, T.; Keitsch, M.M. Exploring relationships between universal design and social sustainable development: Some methodological aspects to the debate on the sciences of sustainability. Sustainable development 2010, 18, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradian, O.; Rakhshandehroo, M.; Abdolahzade Fard, A. The role of urban parks in the social sustainability of cities, case study Azadi park, Shiraz. 2019.

- Wang, C.; et al. The social equity of urban parks in high-density urban areas: A case study in the core area of Beijing. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunışık, R.; et al. Sosyal bilimlerde araştırma yöntemleri: SPSS uygulamalı. 2007: Sakarya yayıncılık.

- Shrestha, NFactor analysis as a tool for survey analysis. American journal of Applied Mathematics and statistics 2021, 9, 4–11.

- Sim, M.; Kim, S.-Y.; Suh, Y. Sample size requirements for simple and complex mediation models. Educational and Psychological Measurement 2022, 82, 76–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.; Shaw, P. The contribution of culture to regeneration in the UK: A review of evidence: A report to the Department for Culture Media and Sport. 2004.

- Wagoner, J.A.; Belavadi, S.; Jung, J. Social identity uncertainty: Conceptualization, measurement, and construct validity. Self and Identity 2017, 16, 505–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, A.; et al. Structural functionalism, social sustainability and the historic environment: A role for theory in urban regeneration. The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice, 2020, 11, 158–180. [Google Scholar]

- Bacon, N.; et al. Creating strong communities: How to measure the social sustainability of new housing developments. The Berkeley Group: London, UK, 2012: P. 38.

- Friedkin, N.E. Social cohesion. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2004, 30, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiefer, D.; Van der Noll, J. The essentials of social cohesion: A literature review. Social Indicators Research 2017, 132, 579–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, H. Urban form and locality, in Sustainable Communities. 2013, Routledge. p. 105-122.

- Pierson, J.H. Tackling social exclusion: Promoting social justice in social work. 2009: Routledge.

- Dempsey, N.; Brown, C.; Bramley, G. The key to sustainable urban development in UK cities? The influence of density on social sustainability. Progress in planning 2012, 77, 89–141. [Google Scholar]

- Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y. Social sustainability: A new conceptual framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, H. Sustainable communities: The potential for eco-neighbourhoods. 2000: Earthscan.

- Crabtree, A.; Gasper, D. Conclusion: The sustainable development goals and capability and human security analysis. Sustainability, capabilities and human security, 2020: P. 169-182.

- Shaftoe, H. Community safety and actual neighbourhoods, in Sustainable Communities. 2013, Routledge. p. 252-267.

- Mehta, V. Evaluating public space. Journal of Urban design 2014, 19, 53–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charkhchian, M.; Abdolhadi Daneshpour, S. Introduction to Multiple Dimensions of a Responsive Public Space; A case study in Iran. Prostor: Znanstveni časopis za arhitekturu i urbanizam 2010, 18, 218–227. [Google Scholar]

- Low, S.; Taplin, D.; Scheld, S. Rethinking urban parks: Public space and cultural diversity. 2005: University of Texas Press.

- Talen, E. Reconciling the link between new urbanism and community. in American Planning Association 2001 National Planning Conference, New Orleans. 2001.

- Lewicka, M. What makes neighborhood different from home and city? Effects of place scale on place attachment. Journal of environmental psychology 2010, 30, 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. Journal of environmental psychology 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. The instinctoid nature of basic needs. Journal of personality 1954.

- Chappells, H. Comfort, well-being and the socio-technical dynamics of everyday life. Intelligent Buildings International 2010, 2, 286–298. [Google Scholar]

- Fincher, W.; Boduch, M. Standards of human comfort: Relative and absolute. 2009.

| Dimension | Variables | Sub-dimension |

|---|---|---|

| Identitity | It holds an important place in the city's history. | Historical identity Environmental identity |

| It has contributed to the preservation of the city's historical and cultural values. | ||

| It has unique spaces. | ||

| It is among the symbols of the city. | ||

| Place attachment | I feel comfortable in the park. | Belonging to the area Belonging to the community |

| I am happy to be here. | ||

| I feel like I can be myself here. | ||

| While spending time here, I feel a sense of belonging to this place. | ||

| Comfort | There are sufficient seating elements within the park area. | General needs The presence of facilities Maintenance and cleaning |

| There are dining facilities such as restaurants, cafes, and kiosks available. | ||

| There are adequate facilities (toilets, fountains, etc.) to meet general needs. | ||

| The maintenance and cleanliness are sufficient. | ||

| Security and Safety | The security (such as guards, private security, etc.) is adequate. | Individual perception of security Security of the area |

| Evening lighting is sufficient. | ||

| During the day, I feel safe in the park when I am alone. | ||

| It is safe to be alone in the park after dark. | ||

| It is safe for children. | ||

| Social Equity | There is gender equality. | Gender equality Equilaty of faith Appealing to all ages Social cohesion |

| Regardless of language, religion, or beliefs, everyone uses the park equally. | ||

| It is suitable for use by all age groups. | ||

| Everyone can participate in all recreational activities. | ||

| It contributes to the integration of different cultures. | ||

| It is open to all socio-economic groups. | ||

| Facilities | The lawns are sufficient for various activities such as exercise and relaxation. | Activity area suitability Activity facility and infrastructure adequacy |

| The facilities are diverse enough to meet the recreational needs of different groups. The walking paths are well-designed. | ||

| Accessibility | Access to the area is varied. | Accessibility to park Accessibility in park |

| The walking areas are sufficient. | ||

| It is possible to reach every part of the area on foot. |

| Dimensions | Frequency | Frequency Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 64 | 53.3 |

| Male | 56 | 46.7 | |

| Age | 18-24 | 39 | 32.5 |

| 25-35 | 38 | 31.7 | |

| 36-45 | 17 | 14.2 | |

| 46-55 | 18 | 15.0 | |

| Over 56 | 8 | 6.7 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 52 | 43.3 |

| Single | 68 | 56.7 | |

| Educational Status | Primary | 12 | 10.0 |

| High | 42 | 35.0 | |

| University | 50 | 41.7 | |

| Postgraduate | 16 | 13.3 | |

| Working Status | Public instution | 15 | 12.5 |

| Private sector | 40 | 33.3 | |

| Unemployed | 65 | 54.2 | |

| Income | Low | 99 | 82.5 |

| Middle | 18 | 15 | |

| High | 3 | 2.5 |

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy. | ,769 | |

| Bartlett's Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 1232,877 |

| df | 300 | |

| Sig. | ,000 | |

| Component | Initial Eigenvalues | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings | Rotation Sums of Squared Loadingsa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | |

| 1 | 5,834 | 23,337 | 23,337 | 5,834 | 23,337 | 23,337 | 4,506 |

| 2 | 3,176 | 12,704 | 36,041 | 3,176 | 12,704 | 36,041 | 3,179 |

| 3 | 2,329 | 9,318 | 45,359 | 2,329 | 9,318 | 45,359 | 3,631 |

| 4 | 1,460 | 5,840 | 51,200 | 1,460 | 5,840 | 51,200 | 2,092 |

| 5 | 1,356 | 5,422 | 56,622 | 1,356 | 5,422 | 56,622 | 2,821 |

| 6 | 1,148 | 4,592 | 61,214 | 1,148 | 4,592 | 61,214 | 1,939 |

| 7 | 1,114 | 4,455 | 65,669 | 1,114 | 4,455 | 65,669 | 1,248 |

| 8 | 1,015 | 4,059 | 69,729 | 1,015 | 4,059 | 69,729 | 1,757 |

| 9 | ,842 | 3,370 | 73,098 | ||||

| 10 | ,763 | 3,052 | 76,151 | ||||

| 11 | ,670 | 2,679 | 78,830 | ||||

| Maddeler | F1_Ide | F2_Pl.at | F3_Com | F4_Fa | F5_Acc | F6_Equ | F7_Co | F8_Sa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S24 | ,626 | ,307 | ||||||

| S25 | ,674 | |||||||

| S26 | ,899 | |||||||

| S27 | ,817 | |||||||

| S28 | ,829 | |||||||

| S14 | ,372 | ,473 | ||||||

| S15 | ,642 | |||||||

| S16 | ,894 | |||||||

| S17 | ,860 | |||||||

| S1 | -,666 | |||||||

| S2 | -,728 | |||||||

| S3 | -,844 | |||||||

| S4 | -,783 | |||||||

| S8 | ,754 | |||||||

| S9 | ,746 | |||||||

| S5 | ,761 | |||||||

| S6 | ,810 | |||||||

| S7 | ,360 | ,635 | ||||||

| S21 | ,686 | |||||||

| S22 | ,788 | |||||||

| S23 | ,699 | |||||||

| S18 | ,312 | ,651 | ||||||

| S19 | ,749 | |||||||

| S20 | ,690 | |||||||

| S10 | ,367 | ,715 | ||||||

| S11 | ,801 | |||||||

| S12 | ,679 | |||||||

| S13 | ,535 |

| Mean | Median | Mode | Std. Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comfort | 2,7583 | 3 | 3 | 1,02896 | 1 | 5 |

| Accessibility | 3,1417 | 3 | 3 | 0,98983 | 1 | 5 |

| Facilities | 3,4333 | 3 | 3 | 1,17204 | 1 | 5 |

| Safety | 2,4417 | 2 | 3 | 1,08307 | 1 | 5 |

| Place Attachment | 2,5417 | 2 | 2 | 1,15879 | 1 | 5 |

| Equity | 3,375 | 3 | 4 | 1,11568 | 1 | 5 |

| Cohesion | 3,4917 | 4 | 4 | 1,20221 | 1 | 5 |

| Identity | 3,775 | 4 | 5 | 1,08048 | 2 | 5 |

| Social Sustainability | 3,100 | 3 | 3 | 0,65337 | 1 | 5 |

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comfort | 2,594 | 4 | ,648 | ,604 | ,660 |

| Accessibility | ,942 | 4 | ,236 | ,234 | ,919 |

| Facilities | 3,857 | 4 | ,964 | ,653 | ,626 |

| Safety | 4,754 | 4 | 1,188 | 1,014 | ,403 |

| Place attachment | 4,287 | 4 | 1,072 | ,793 | ,532 |

| Equity | 9,339 | 4 | 2,335 | 1,935 | ,109 |

| Cohesion | ,959 | 4 | ,240 | ,161 | ,958 |

| Identity | 9,746 | 4 | 2,437 | 2,169 | ,077 |

| Social sustainability | 2,640 | 4 | ,660 | 1,576 | ,185 |

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Correlations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Zero-order | Partial | Part | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | -,004 | ,154 | -,028 | ,978 | ||||

| Comfort | ,128 | ,032 | ,202 | 4,003 | ,000 | ,561 | ,355 | ,168 | |

| Access. | ,082 | ,031 | ,124 | 2,665 | ,009 | ,394 | ,245 | ,112 | |

| Facilities | ,139 | ,024 | ,257 | 5,766 | ,000 | ,464 | ,480 | ,242 | |

| Safety | ,146 | ,029 | ,242 | 5,120 | ,000 | ,412 | ,437 | ,215 | |

| Place att. | ,126 | ,026 | ,223 | 4,778 | ,000 | ,383 | ,413 | ,200 | |

| Equity | ,127 | ,028 | ,216 | 4,506 | ,000 | ,501 | ,393 | ,189 | |

| Cohesion | ,101 | ,028 | ,187 | 3,630 | ,000 | ,536 | ,326 | ,152 | |

| Identity | ,147 | ,031 | ,243 | 4,720 | ,000 | ,532 | ,409 | ,198 | |

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate | Change Statistics | ||||

| R Square Change | F Change | df1 | df2 | Sig. F Change | |||||

| 1 | ,897a | ,805 | ,791 | ,29899 | ,805 | 57,158 | 8 | 111 | ,000 |

| Model | Ide. | Pl_at. | Fac. | Acc. | Sa. | Equ. | Com. | Co. | ||

| Correlations | Ide. | 1,000 | ,004 | -,025 | ,055 | ,042 | -,341 | -,115 | -,327 | |

| Pl_at. | ,004 | 1,000 | ,071 | -,071 | -,383 | -,056 | -,106 | ,076 | ||

| Fac. | -,025 | ,071 | 1,000 | ,052 | -,123 | -,057 | -,227 | -,069 | ||

| Acc. | ,055 | -,071 | ,052 | 1,000 | -,196 | -,019 | -,309 | -,072 | ||

| Sa. | ,042 | -,383 | -,123 | -,196 | 1,000 | -,006 | ,047 | ,006 | ||

| Equ. | -,341 | -,056 | -,057 | -,019 | -,006 | 1,000 | ,008 | -,159 | ||

| Com. | -,115 | -,106 | -,227 | -,309 | ,047 | ,008 | 1,000 | -,252 | ||

| Co. | -,327 | ,076 | -,069 | -,072 | ,006 | -,159 | -,252 | 1,000 | ||

| Rank | Mean | Sig | Priority | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comfort | 3,71 | 2,7583 | 0.000 | 6 |

| Accessibility | 4,61 | 3,1417 | 5 | |

| Facilities | 5,18 | 3,4333 | 2 | |

| Safety | 3,31 | 2,4417 | 8 | |

| Place attachment | 3,37 | 2,5417 | 7 | |

| Equity | 4,95 | 3,3750 | 4 | |

| Cohesion | 5,16 | 3,4917 | 3 | |

| Identity | 5,72 | 3,7750 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).