1. Introduction

Depression, characterized by a persistent low mood and negatively biased cognitive patterns, remains a widespread mental health concern globally. According to the World Health Organization (2023), an estimated 3.8% of the global population suffers from depression. Along with its high prevalence, the recurrence rate of depressive episodes is notably high (Buckman et al., 2018). These factors underscore the need for a more comprehensive understanding of depression's cognitive underpinnings. One key aspect is the cognitive impairments associated with depression, particularly those involving negatively biased thoughts and impaired cognitive control (Gotlib & Joormann, 2010).

Cognitive control refers to the ability to maintain and update task goals and behavior in response to changing demands, allowing for adaptive cognitive and behavioral responses (Miller & Cohen, 2001). Tt encompasses a range of functions and has been conceptualized through various models (Botvinick et al., 2001; Miyake et al., 2001). Among these, the Dual Mechanisms of Control (DMC) framework (Braver, 2007) distinguishes between two modes of cognitive

control: reactive control, which operates in a bottom-up fashion by responding to stimuli as they occur, and proactive control, a top-down process that involves maintaining goal-relevant information over time (Braver, 2012; Braver et al., 2007). The DMC framework has been influential in understanding cognitive control in various contexts, including aging (Kopp et al., 2014), schizophrenia (Kwashie et al., 2023), and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Cai et al., 2023).

Several studies have demonstrated that depressive symptoms are closely linked with deficits in cognitive control (Joormann & Tanovic, 2015). These deficits manifest in various depression-related cognitive phenomena, such as attention and memory biases, rumination, and automatic negative thoughts (Gotlib & Joormann, 2010). Studies within the DMC framework have shown that individuals with depression tend to rely more on reactive control and less on proactive control during tasks that require both (Msetfi et al., 2009). Additionally, reactive control is further impaired when individuals with depression are exposed to negative emotional stimuli (Masuyama et al., 2018). Mood induction procedures have also demonstrated that negative mood exacerbates proactive control deficits in depressive individuals, suggesting an imbalance between the two control processes (Masuyama & Mochizuki, 2020). While these findings are valuable, many questions remain, particularly regarding how stress affects cognitive control processes in depression.

Stress is a well-documented factor influencing cognitive function, particularly in the context of depression. Stress has been shown to impair cognitive control across various domains (Starcke et al., 2017; Vargas et al., 2020; Vrshek-Schallhorn et al., 2019). For instance, studies have found that cognitive control can predict how individuals respond to stressful life events (Gabrys et al., 2018). Tn experimental settings, individuals with depression tend to perform worse on cognitive control tasks after being exposed to stress (Quinn & Joormann, 2014). Moreover, cognitive control has been found to predict rumination and stress responses, even after a short delay (Zareian et al., 2021), and cognitive control training has been shown to enhance resilience to stress (Hoorelbeke et al., 2015). These results suggest that stress may have a profound impact on cognitive control, particularly in individuals with depression.

While several studies have investigated the effects of stress on cognitive control, the specific impact of stress on the balance between reactive and proactive control within the DMC framework remains unclear. For example, a study by Husa et al. (2022) found that physiological changes induced by stress led to a predominance of proactive control. However, this study did not focus on individuals with depression, and the effects of stress on reactive and proactive control in depressive populations are still not fully understood.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the impact of experimentally induced stress on reactive and proactive control in individuals with depressive symptoms. Specifically, we aimed to determine whether the balance between these two modes of control, as described by the DMC framework, changes after exposure to an experimental stressor. The experimental stressor used was an anagram task, a method widely adopted in previous studies (Yang et al., 2018). By examining the effects of stress on cognitive control in depression, this study seeks to contribute to a deeper understanding of the cognitive vulnerabilities associated with depression and may inform new treatment strategies targeting cognitive processes, such as cognitive control training and attentional bias training (Hoorelbeke et al., 2015; Maciejewski et al., 2020; ).

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 142 individuals (55 female, 84 male, 3 unspecified) participated in this study (mean age = 40.46, SD = 7.99). Participants were recruited through a cloud-sourcing service (Crowdworks:

https://crowdworks.jp). Eligibility criteria included being between the ages of 18 and 65, having normal or corrected-to-normal vision, access to a stable internet connection, and a desktop or laptop computer, as well as a distraction-free environment during the tasks. All study procedures were conducted using the online experiment platform Pavlovia (

https://pavlovia.org), where participants completed the tasks on desktop or laptop computers with sufficient internet speed. Participants received an explanation of the study online, and informed consent was obtained electronically.

Participants were pseudo-randomly assigned to either the high-stress (experimental) condition (n = 82) or the low-stress (control) condition (n = 55). Tn addition, based on the cut-off score of the Beck Depression Tnventory-TT (BDT-TT), participants were classified into the depressive group (BDT-TT score > 13) or the non-depressive group (BDT-TT score < 14) within each condition. The final distribution was as follows: in the high-stress condition, 48 participants were classified as depressive and 34 as non-depressive, and in the low-stress condition, 21 were classified as depressive and 34 as non-depressive. Due to technical issues, the allocation of participants to the high-stress and control groups did not converge to an equal distribution, resulting in a slightly larger number of participants in the experimental group.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Beck Depression Tnventory-TT (BDT-TT)

BDT-TT is a 21-item self-report scale that evaluates the severity of depressive symptoms (Beck et al., 1996). Each item is rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3. Participants completed the Japanese version of BDT-TT, which has well validation and reliability (Kojima et al., 2002). The internal consistency in this study was ³ = 0.929.

2.2.2. AX-Version Continuous Performance Task (AX-CPT)

The AX-CPT is a cognitive task designed to measure the degree of reactive and proactive control processes (Braver, 1999). Cognitive control is assessed by determining whether participants can appropriately respond to a probe stimulus while retaining information from a previously presented cue stimulus (Braver, 2012). Cue and probe stimuli are presented as letters from the alphabet. Participants are instructed to press the "target" key ("j") when the probe letter "X" is preceded by the correct cue letter "A" (AX trial). Tn all other cases-"A" followed by a non-"X" (AY trial), a non-"A" followed by "X" (BX trial), or both non-"A" and non-"X" (BY trial)- participants are required to press the "non-target" key ("f").

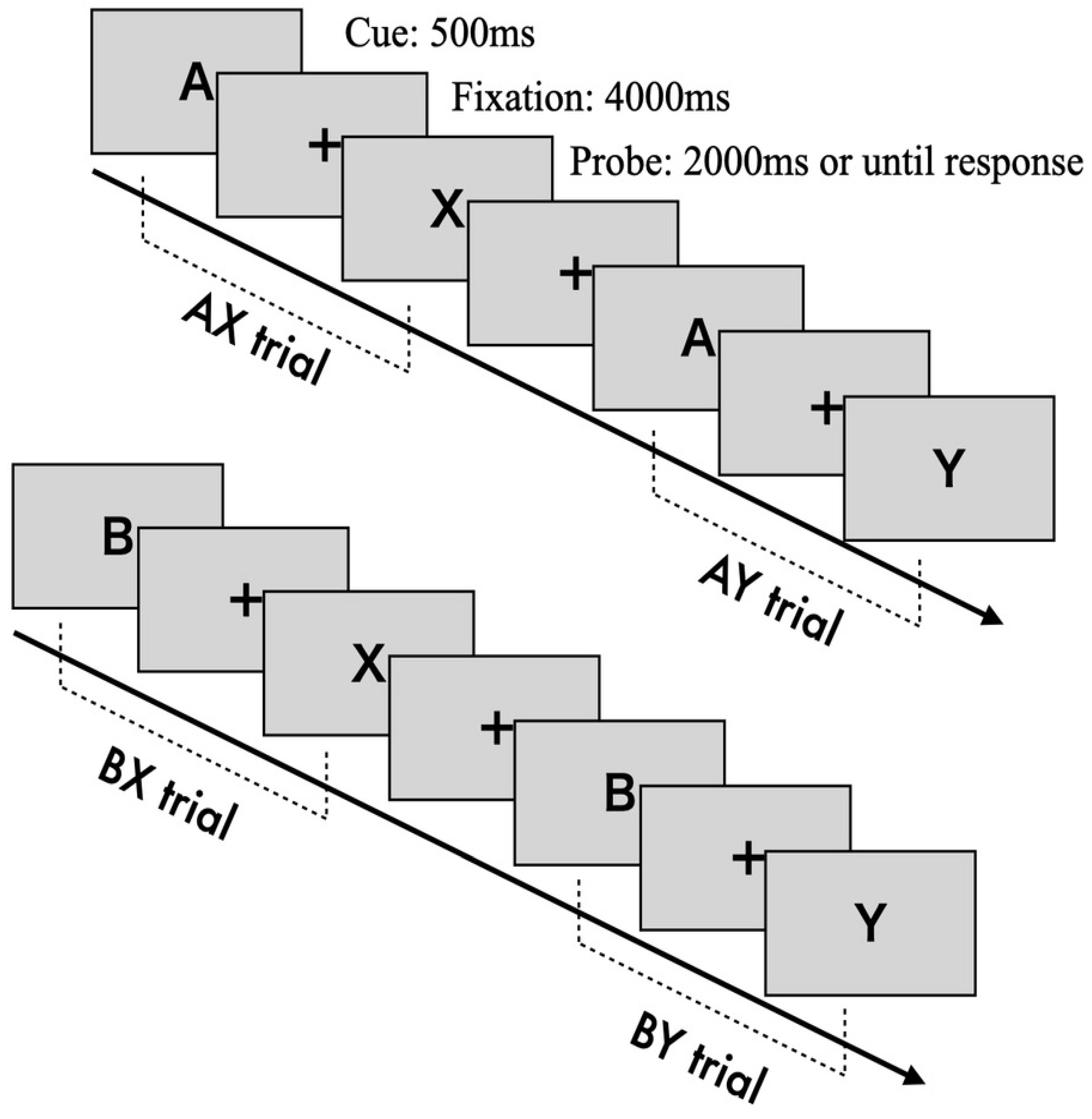

Each trial consists of the following sequence (see

Figure 1): a fixation cross (500 ms), the presentation of the cue stimulus (500 ms), a blank screen with fixation (4000 ms), and the presentation of the probe stimulus (until response or a 2000 ms timeout). The fixation, cue, and probe letters are displayed in approximately 70-point Arial font. The task includes 100 trials in total, with 70 AX trials and 10 trials each for the AY, BX, and BY conditions.

2.2.3. Anagram Task

The Anagram task was used to induce an experimental stress state. Participants were asked to rearrange five Japanese hiragana characters into meaningful words. The stimuli were sourced from a database of 5-letter Hiragana Anagrams (Tchimura, 2017). The difficulty level of the anagrams was manipulated to create high- and low-stress conditions. Based on the difficulty indices-correct rate, solving time, and subjective difficulty-from the database (Tchimura, 2017), stimuli were selected for each stress condition. For the high-stress group, the average correct rate was 73%, solving time was 49.12 seconds, and subjective difficulty was 4.61 (on a scale from 1 to 7). Tn contrast, the low-stress group had an average correct rate of 98%, solving time of 10.65 seconds, and subjective difficulty of 1.84.

Both the high- and low-stress conditions consisted of 10 anagrams. Participants were given 30 seconds to solve each anagram by typing the correct letters. Tf the 30-second time limit was exceeded, the next anagram automatically began.

2.2.4. Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)

To assess the stress induced by the anagram task, three Visual Analogue Scales (VAS), each ranging from 1 to 100, were used. These scales measured: Stress (from "no stress" to "severe stress"), Fatigue (from "not tired" to "very tired"), and Mood (from "sad" to "happy").

Participants rated their current state on each scale according to how they felt at the time.

2.3. Procedures

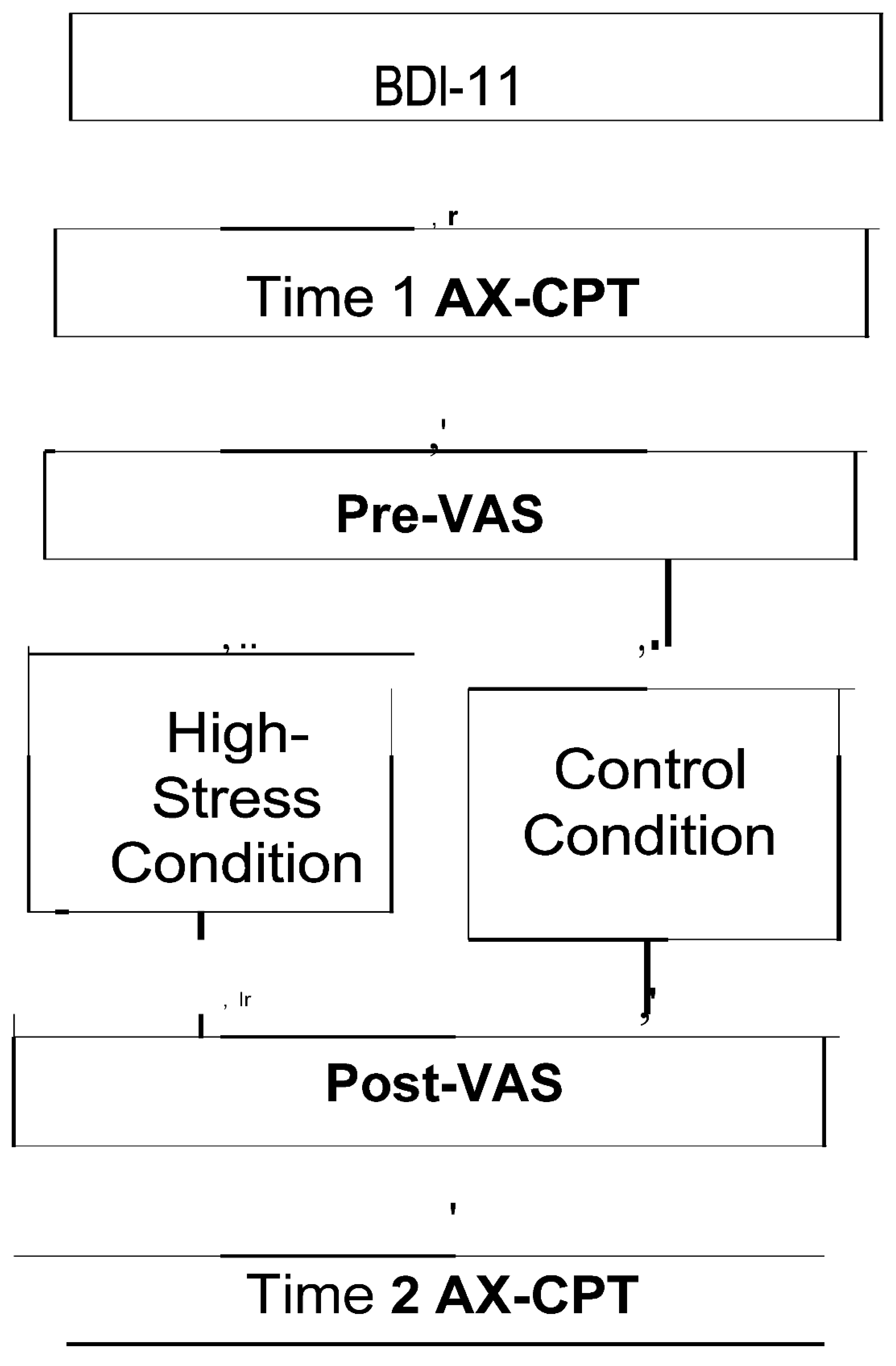

Figure 2 outlines the study procedures. First, participants provided informed consent and completed the Beck Depression Tnventory (BDT). Then, the AX-CPT and VAS assessments were conducted as baseline measurements. Participants pseudo-randomly assigned to the high-stress group completed difficult anagrams, while those in the control group solved easier anagrams.

The VAS was repeated to assess stress manipulation. Finally, the AX-CPT was administered again. The experiment concluded with a debriefing for both groups, and participants in the high- stress group were shown a simple relaxation method to alleviate their stress. The procedures were conducted online. All study procedures were approved by the ethics committee of the Aichi University of Education (Approval No. AUE20240203HUM).

2.4. Data Analyses

The error rates and average reaction times in the AX-CPT were recorded for each trial type: AX, AY, BX, and BY. These data were used to compute three indices that reflect cognitive control activity: the Proactive Behavior Tndex (PBT), d'-context, and A-cue bias. The PBT, calculated as (AY - BX) / (AY + BX) using error rates and reaction times, reflects the balance between proactive and reactive control (Braver et al., 2009). Higher cue interference, leading to more errors and delayed responses in AY trials, indicates a dominance of proactive control.

Conversely, higher probe interference in BX trials suggests a dominance of reactive control. Therefore, a positive PBT value indicates a greater reliance on proactive control, while a negative value suggests a shift toward reactive control.

The d'-context and A-cue bias indices are based on signal detection theory. d'-context was calculated as Z(AX hit rate) - Z(BX error rate), with Z representing the z-transformation. This index reflects the ability to discriminate between the correct cue ("A") and noise ("B"). A higher d'-context value indicates better retention of contextual information, while a lower value reflects poorer retention. A-cue bias was calculated as 1/2 * (Z(AX hit rate) + Z(AY error rate)). This index measures participants' ability to form correct responses based on cue information ("A"), with higher values indicating more accurate cue-based responses regardless of the probe stimuli.

Exclusion criteria, based on the performance in the AX-CPT, were adopted following the guidelines from Gonthier et al. (2016) and Snijder et al. (2024). Fourteen participants were excluded from the analysis due to extremely poor performance: five had an error rate of 50% or more in AX trials, four had an error rate of 90% or more in AY, BX, and BY trials, and five had an average error rate of 40% or more in AY, BX, and BY trials.

Mixed ANOVAs were conducted for each variable. To improve normality, log- transformed reaction times and z-transformed error rates were used in the ANOVAs for AX-CPT performance. The Tukey correction was applied in post hoc analyses.

3. Results

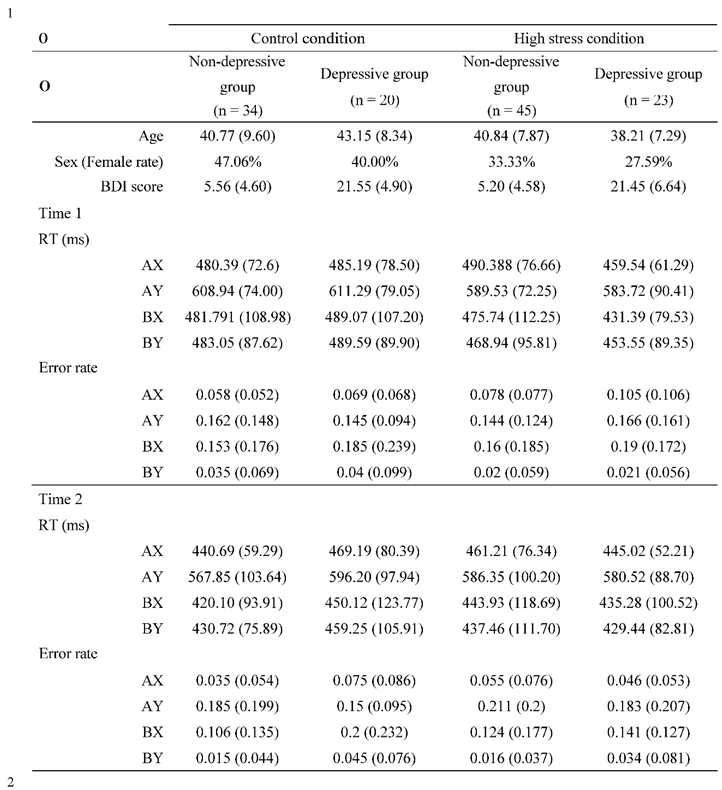

The descriptive statistics were summarized in

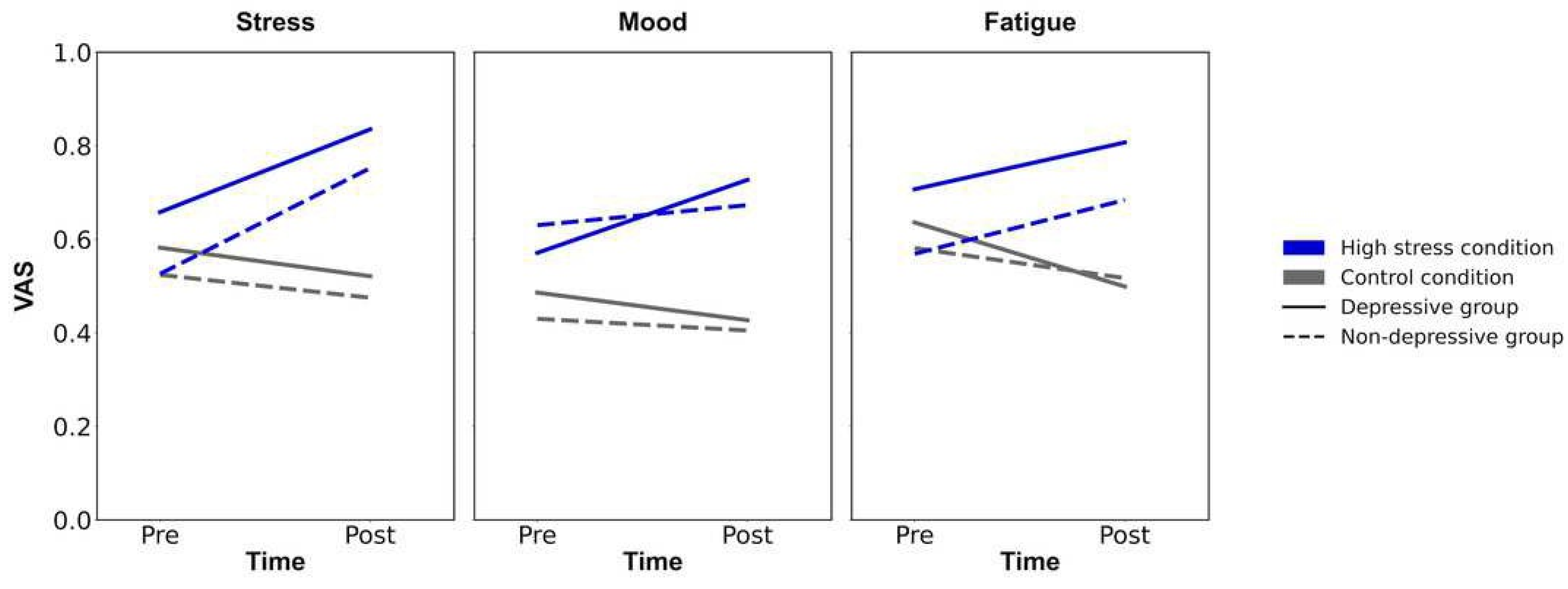

Table 1. Firstly, to confirm the experimental manipulation, repeated ANOVAs were conducted for each VAS (mood, stress, and fatigue) with time (pre/ post) and condition (high stress/ control condition;

Figure 3). For VAS of stress, the analysis revealed the significant main effects of time and condition (

F(124, 1) > 10.554,

p f .001,

·p² > .078) and their interaction (

F (124, 1) = 32.201,

p < .001,

·p² = .206). The post hoc analysis showed that the VAS of stress in high-stress condition on post-timepoint was greater than the VAS in high-stress condition on pre-timepoint (

p < .001, Cohen's

d = 0.78), and the VAS in the control condition on post-timepoint (

p < .001, Cohen's

d = 1.15). For VAS for fatigue, the significant main effect of condition and interaction of time and condition were also observed (

Fs (1, 124) > 12.766,

ps < .001,

·p² > .093). The post hoc analysis revealed that the VAS of fatigue in high stress condition on post-timepoint was greater than on pre-timepoint (

p < .001, Cohen's

d = 0.47), and the VAS in control condition on post-timepoint (

p < .001, Cohen's

d = 1.04). However, the ANOVA for VAS of mood revealed a non-significant interaction of time and condition (

F (124, 1) = 0.273,

p = .776,

·p² = .000), suggesting that the experimental manipulation of stress state in this study did not affect the VAS of mood. Through all ANOVAs for VAS of stress, fatigue, and mood, there were no significant main effects of group (

Fs (1, 124) > 3.652,

ps < .058), showing the irrelevance of depressive symptoms for the induction of stress states. Summing up, the results showed that the participants in high stress condition felt stress and mental fatigue compared to before they administered the difficult anagram task, and to participants in control condition, suggesting the success of experimental manipulation.

Secondly, to identify the effect of stress on AX-CPT performance, repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted for error rates and reaction times, with the following independent variables: trial type (AX, AY, BX, BY; within-subject), time (Time 1/Time 2; within-subject), condition (high stress/control; between-subject), and group (depressive/non-depressive; between- subject). The analysis of reaction times revealed a significant main effect of trial type (F (124, 3) = 234.913, p < .001, ·p² = .655) and time (F (124, 1) = 29.908, p < .001, ·p² = .194), as well as an interaction of time and condition (F (124, 3) = 4.248, p = .041, ·p² = .033). However, none of the other main effects or interactions were significant (Fs > 3.767, ps < .055). The post hoc test revealed that the reaction times for the AY trial were significantly greater than for the AX, BX, and BY trials (ps < .001, Cohen's ds > 1.366). The analysis also showed that the reaction times at Time 1 for participants in the non-depressive group and control condition were significantly greater than at Time 2 (p < .001, Cohen's d = 0.406). Similarly, the reaction times at Time 1 for participants in the depressive group and high-stress condition were significantly greater than at Time 2 (p = .037, Cohen's d = 0.184). These results suggest that improvements in reaction time due to habituation from repeated AX-CPT trials occurred regardless of condition and group. For the error rates, the same analysis revealed a significant main effect of trial type (F (124, 3) = 55.956, p < .001, ·p² = .311) and an interaction between trial type and time (F (124, 3) = 4.075, p = .007, ·p² = .032). Tn contrast, none of the other main effects or interactions were significant (Fs < 2.467, ps > .119). The post hoc analysis showed that the error rates for the AY and BX trials were significantly greater than those for the AX and BY trials (ps < .001, Cohen's ds > .706). Similar results were obtained from the post hoc analysis for the interaction between trial type and time (ps < .001, Cohen's ds > .586), suggesting consistently higher error rates for both AY and BX trials. These results indicate a specificity of the AY and BX trials in the AX-CPT, supporting the validity of computed indices such as PBT, which is discussed below.

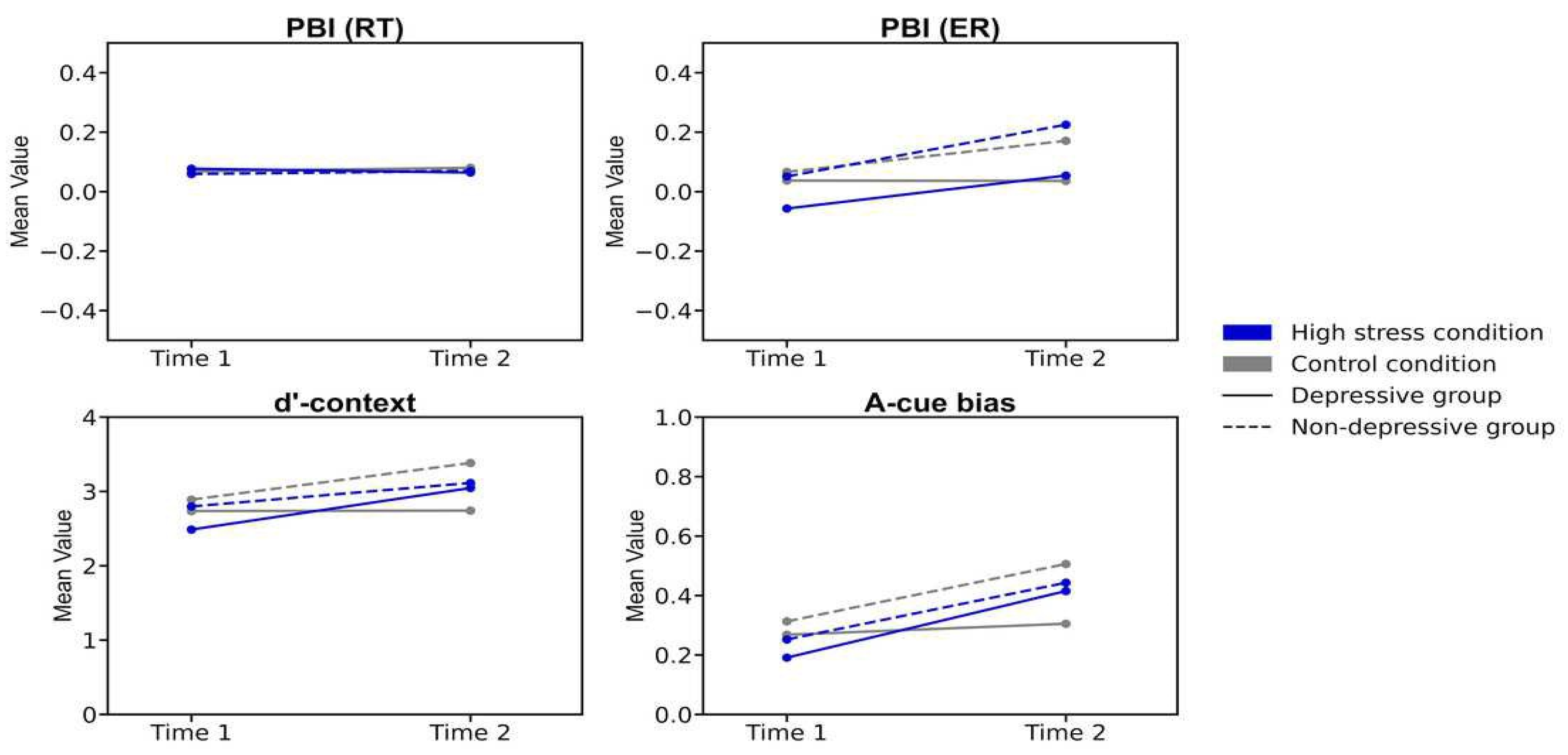

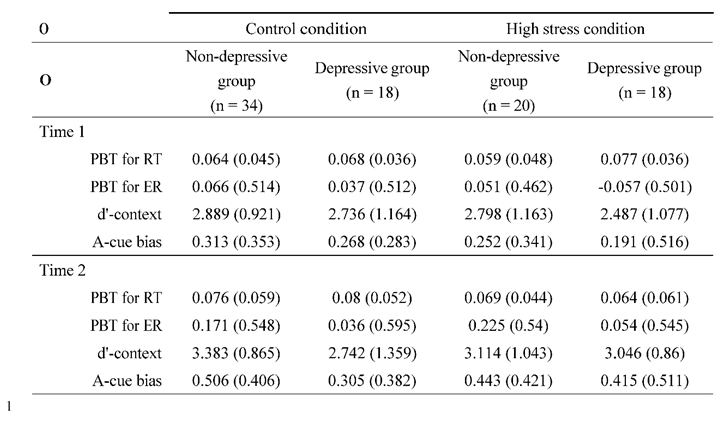

Lastly, repeated ANOVAs were conducted on each index: PBT,

d'-context, and A-cue bias (

Table 2;

Figure 3). The analyses included the factors of time (Time 1/Time 2), condition (high stress/control), and group (depressive/non-depressive). The analysis for PBT showed that none of the main effects or interactions reached statistical significance (

Fs (1, 124) < 0.722,

p > .08,

·p²< .024). The result suggested that there were no significant changes in the balance between reactive and proactive control before and after experiencing stress, regardless of the presence or absence of depressive symptoms.

The analysis for d'-context revealed a significant main effect of time (F (124, 1) = 6.940, p < .001, ·p² = .012) and a three-way interaction of time, condition, and group (F (124, 1) = 4.739, p = .03, ·p² = .004). The post hoc analysis showed that the score in the high-stress condition for the depressive group at Time 2 was lower than that at Time 1 (p = .026, Cohen's d = 0.531) and also lower than the score for the non-depressive group in the control condition at Time 2 (p= .020, Cohen's d = 0.852). The results suggested that individuals in the depressive group under high stress experienced a greater decline in d'-context from Time 1 to Time 2, with their scores being lower at Time 2 compared to those in the non-depressive group in the control condition. This indicates that the combination of high stress and depressive symptoms may have a more pronounced negative impact on cognitive control over time.

The analysis for A-cue bias showed a significant main effect of time (F (124, 1) = 13.296, p < .001, ·p² = .097). However, none of the other main effects or interactions reached statistical significance (Fs (1, 124) < 1.867, p > .17, ·p² < .015). The post hoc analysis revealed that the score in the high-stress condition at Time 2 was significantly lower than that at Time 1 (p = .002, Cohen's d = 0.508). The results suggested that A-cue bias decreased after experiencing high stress, regardless of the presence or absence of depressive symptoms.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the impact of experimental stress on cognitive control within the context of depression psychopathology. To achieve this, participants were divided into high-stress and control conditions and further classified into depressive and non-depressive groups based on the BDT cutoff score. The AX-CPT task was administered both before and after exposure to the experimental stressor in the high-stress condition, while the control condition involved exposure to a non-stressful or low-stress environment. Subsequently, the effects of stress on depression and cognitive control were examined by comparing AX-CPT performance and cognitive control measures after stress in the depressed group with their performance before stress, as well as with the control group. The analyses revealed that the balance between reactive and proactive control, as conceptualized in the Dual Mechanisms of Control (DMC) framework, did not change after exposure to higher experimental stressors. However, the function of cognitive control related to retaining contextual information decreased after exposure to experimental stress in the depressive group. This suggests that stress selectively impacts aspects of cognitive control associated with the psychopathology of depression.

The statistical analysis revealed that the PBT in the high-stress condition for the depressive group did not differ from any other conditions or groups. This suggests that the balance between reactive and proactive control was not affected by stress in relation to depression, consistent with findings from previous studies (Birk et al., 2018; Husa et al., 2022). Birk et al. (2018) examined the effect of proactive control training on anxiety-related characteristics. Their results showed that proactive control training did not improve PBT scores; however, state anxiety increased less during social stress tasks compared to the control condition. Similarly, Husa et al. (2022) found no differences in PBT scores, calculated using both reaction times and error rates, before and after exposure to the experimental stressor, despite evidence of physiological stress changes.

Taken together, these findings suggest that changes in the balance of cognitive control, as reflected in the PBT, may depend on more stable factors and conditions rather than those that induce transient fluctuations. Tndeed, Cooper et al. (2017) reported that individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia exhibited stable performance in the AX-CPT compared to healthy controls, indicating a consistent influence of psychiatric-related factors on reactive and proactive control. Therefore, to more precisely identify the effects of stress on the balance between reactive and proactive control, it would be necessary to focus on relatively long-term time points.

The analysis for PBT did not reveal a main effect of group (depressive/non-depressive), suggesting that depression is not related to the balance between reactive and proactive control. While well-documented links between cognitive control and depression exist (e.g., Koster et al., 2017; Paulus, 2015; Villalobos et al., 2021), research specifically examining the relationship between PBT and depressive symptoms remains limited. Therefore, the lack of an association between PBT and depressive symptoms in this study is noteworthy. A study by Masuyama and Mochizuki (2020) similarly found no relationship between PBT and depressive symptoms, aligning with our findings. However, other studies have demonstrated a link between depression- related characteristics and cognitive control within the DMC framework (Masuyama et al., 2018; Vanderhasselt et al., 2014). Given the lack of association between PBT and depression in this study, there are two possible explanations. First, the validity of PBT as an index for the balance between reactive and proactive control may be in question. As Snijder et al. (2024) suggested, PBT-calculated solely based on performance in AY and BX trials-may require an alternative or supplementary indicator. Second, impaired reactive or proactive control processes may be specific to negative-related cognitive processes, consistent with the distinction between "hot" and "cold" cognition (Roiser & Shahakian, 2013). Tndeed, Masuyama et al. (2018) reported that cognitive control impairments in depressive individuals were only evident when negative- valenced distractors were present. Thus, the relationship between depression and cognitive control within the DMC framework still requires further exploration, and additional research is necessary to advance our understanding.

However, partial effects of both stress and depression on cognitive control were suggested by the results of the d'-context index in this study. Tn contrast, the results for A-cue bias did not reach statistical significance. Considering the nature of these indices-d'-context being related to the retention of cue information, while A-cue bias pertains to probe-response processes-the findings can be interpreted as the interaction of depression and stress primarily affecting cue- related information processing. As schematically depicted in Braver (2012) and Li et al. (2018), from cue presentation to probe presentation, individuals need to activate proactive control, which is involved in goal activation and maintenance. Then, from probe presentation to response, they must activate reactive control, which is involved in conflict resolution and response inhibition.

Notably, the switch from proactive to reactive control at the time of probe presentation is considered crucial for appropriate cognition and behavior (Braver, 2016). Therefore, the results of this study, where the interaction between depression and stress was only associated with cue- related processes but not with probe-related processes, likely reflect impaired proactive control. Specifically, the findings suggest that depressive individuals exhibit impaired proactive control after exposure to stress. Tndeed, several studies have reported that depressive individuals exhibit deficits in maintaining contextual information (Masuyama et al., 2018; Msetfi et al., 2009).

Given the possibility that reactive and proactive control processes are not entirely independent, the results of this study suggest that depression and stress are associated with impaired proactive control.

Tn the end, this study had several limitations. First, because this study was conducted on a general population, caution is needed when extending the interpretation of the results to clinically depressed patients. Some previous studies have demonstrated the influence of psychiatric conditions on cognitive control among patients (Jia et al., 2023; Kwashie et al., 2023; Lesh et al., 2013). These studies compared patients with healthy controls, and therefore may have accurately detected differences in cognitive control. Future research on the cognitive control mechanisms of depression should be conducted on clinically diagnosed individuals.

Second, this study was experimental and did not examine the effects of medium-term or long- term stress. As previously mentioned, the actual effects of prolonged stress on cognitive control should be investigated in more detail in future studies.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to examine the effects of experimental stress on cognitive control within the context of depression. By dividing participants into high-stress and control conditions and further classifying them into depressive and non-depressive groups, we sought to understand how stress interacts with depression to affect cognitive processes. Using the AX-CPT task, we found that while the balance between reactive and proactive control remained unaffected by stress, individuals in the depressive group showed a decline in cognitive control related to retaining contextual information after exposure to stress. These findings suggest that stress selectively impairs proactive control mechanisms in individuals with depression, providing important insights into the cognitive vulnerabilities associated with depression psychopathology. Future research should explore these effects in clinically diagnosed populations and under prolonged stress conditions to better understand the mechanisms linking stress and cognitive control deficits in depression.

References

- Birk, J. L., Rogers, A. H., Shahane, A. D., & Urry, H. L. (2018). The heart of control: Proactive cognitive control training limits anxious cardiac arousal under stress. Motivation and Emotion, 42(1), 64-78. [CrossRef]

- Braver, T. S., Gray, J. S., & Burgess, G. C. (2007). Explaining the many varieties of working memory variation: Dual mechanisms of cognitive control. Tn A. Conway, C. Jarrold, M. Kane, A. Miyake, & J. Towse (Eds.), Variation in working memory (pp. 76-106). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Braver, T. S. (2012). The variable nature of cognitive control: A dual mechanisms framework. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16, 106- 113. [CrossRef]

- Braver, T. S. (2016). Motivation and cognitive control. Psychology Press.

- Botvinick, M. M., Braver, T. S., Barch, D. M., Carter, C. S., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). Conflict Monitoring and Cognitive Control. Psychological Review, 108(3), 624-652. [CrossRef]

- Buckman, J. E., Underwood, A., Clarke, K., Saunders, R., Hollon, S. D., Fearon, P., & Pilling, S. (2018). Risk factors for relapse and recurrence of depression in adults and how they operate: A four-phase systematic review and meta-synthesis. Clinical psychology review, 64, 13-38. [CrossRef]

- Cai, W., Warren, S. L., Duberg, K., Yu, A., Hinshaw, S. P., & Menon, V. (2023). Both reactive and proactive control are deficient in children with ADHD and predictive of clinical symptoms. Translational Psychiatry, 13(1), 179. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S. R., Gonthier, C., Barch, D. M., & Braver, T. S. (2017). The Role of Psychometrics in Tndividual Differences Research in Cognition: A Case Study of the AX-CPT. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1482. [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior research methods, 39(2), 175-191.

- Gabrys, R. L., Tabri, N., Anisman, H., & Matheson, K. (2018). Cognitive Control and Flexibility in the Context of Stress and Depressive Symptoms: The Cognitive Control and Flexibility Questionnaire. Frontiers in psychology, 9, 2219. [CrossRef]

- Gonthier, C., Macnamara, B. N., Chow, M., Conway, A. R. A., & Braver, T. S. (2016). Tnducing Proactive Control Shifts in the AX-CPT. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1822. [CrossRef]

- Gotlib, T. H., & Joormann, J. (2010). Cognition and Depression: Current Status and Future Directions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6(1), 285-312. [CrossRef]

- Hoorelbeke, K., Koster, E. H., Vanderhasselt, M. A., Callewaert, S., & Demeyer, T. (2015). The influence of cognitive control training on stress reactivity and rumination in response to a lab stressor and naturalistic stress. Behaviour research and therapy, 69, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Husa, R. A., Buchanan, T. W., & Kirchhoff, B. A. (2022). Subjective stress and proactive and reactive cognitive control strategies. European Journal of Neuroscience, 55(9-10), 2558- 2570. [CrossRef]

- Jia, L., Zheng, Q., Cui, J., Shi, H., Ye, J., Yang, T., Wang, Y., & Chan, R. C. K. (2023). Proactive and reactive response inhibition of individuals with high schizotypy viewing different facial expressions: An ERP study using an emotional stop-signal task. Brain Research, 1799, 148191. [CrossRef]

- Joormann, J., & Tanovic, E. (2015). Cognitive vulnerability to depression: examining cognitive control and emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 4, 86-92. [CrossRef]

- Kwashie, A. N., Ma, Y., Barch, D. M., Chafee, M., Ragland, J. D., Silverstein, S. M.,... & MacDonald TTT, A. W. (2023). Comparing the functional neuroanatomy of proactive and reactive control between patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 23(1), 203-215. [CrossRef]

- Kopp, B., Lange, F., Howe, J., & Wessel, K. (2014). Age-related changes in neural recruitment for cognitive control. Brain and Cognition, 85, 209-219. [CrossRef]

- Koster, E. H. W., Hoorelbeke, K., Onraedt, T., Owens, M., & Derakshan, N. (2017). Cognitive control interventions for depression: A systematic review of findings from training studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 53, 79-92. [CrossRef]

- Lesh, T. A., Westphal, A. J., Niendam, T. A., Yoon, J. H., Minzenberg, M. J., Ragland, J. D., Solomon, M., & Carter, C. S. (2013). Proactive and reactive cognitive control and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex dysfunction in first episode schizophrenia. NeuroTmage: Clinical, 2, 590-599. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Liu, F., Zhang, Q., Liu, X., & Wei, P. (2018). The Effect of Mindfulness Training on Proactive and Reactive Cognitive Control. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1002. [CrossRef]

- Maciejewski, D., Brieant, A., Lee, J., King-Casas, B., & Kim-Spoon, J. (2020). Neural Cognitive Control Moderates the Relation between Negative Life Events and Depressive Symptoms in Adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 49(1), 118-133. [CrossRef]

- Masuyama, A., Kaise, Y., Sakano, Y., & Mochizuki, S. (2018). The interference of negative emotional stimuli on context processing in mildly depressed undergraduates. Cogent Psychology, 5(1), 1424681. [CrossRef]

- Masuyama, A., & Mochizuki, S. (2020). Tnduced sad mood affects context processing in cognitive control in mildly depressive undergraduates. Current Psychology, 39(4), 1476- 1484. [CrossRef]

- McDermott, R., & Dozois, D. J. A. (2015). The Causal Role of Attentional Bias in a Cognitive Component of Depression. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology, 6(4), 343-355. [CrossRef]

- Miller, E. K., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 24, 167-202. [CrossRef]

- Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D. (2000). The Unity and Diversity of Executive Functions and Their Contributions to Complex "Frontal Lobe" Tasks: A Latent Variable Analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41(1), 49-100. [CrossRef]

- Msetfi, R. M., Murphy, R. A., Kornbrot, D. E., & Simpson, J. (2009). Short article: Tmpaired context maintenance in mild to moderately depressed students. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 62(4), 653-662. [CrossRef]

- Parekh, Ruchit, and Charles Smith. "Innovative AI-driven software for fire safety design: Implementation in vast open structure." World Journal of Advanced Engineering Technology and Sciences 12.2 (2024): 741-750.

- Quinn, M. E., & Joormann, J. (2014). Stress-Tnduced Changes in Executive Control Are Associated With Depression Symptoms. Clinical Psychological Science, 3(4), 628-636. [CrossRef]

- Roiser, J. P., & Sahakian, B. J. (2013). Hot and cold cognition in depression. CNS Spectrums, 18(3), 139-149. [CrossRef]

- Snijder, J.-P., Tang, R., Bugg, J. M., Conway, A. R. A., & Braver, T. S. (2024). On the psychometric evaluation of cognitive control tasks: An Tnvestigation with the Dual Mechanisms of Cognitive Control (DMCC) battery. Behavior Research Methods, 56(3), 1604-1639. [CrossRef]

- Starcke, K., Agorku, J. D. & Brand, M. (2017). Exposure to Unsolvable Anagrams Tmpairs Performance on the Towa Gambling Task. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 11, 114. [CrossRef]

- Vanderhasselt, M.-A., Raedt, R. D., Paepe, A. D., Aarts, K., Otte, G., Dorpe, J. V., & Pourtois, G. (2014). Abnormal Proactive and Reactive Cognitive Control During Conflict Processing in Major Depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123(1), 68-80. [CrossRef]

- Vargas, T., Haeffel, G. J., Jacobucci, R., Boyle, J. T., Mayer, S. E. & Lopez-Duran, N. L. (2020). Negative Cognitive Style and Cortisol Reactivity to a Laboratory Stressor: a Preliminary Study. Tnternational Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 13(1), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, D., Pacios, J., & Vazquez, C. (2021). Cognitive Control, Cognitive Biases and Emotion Regulation in Depression: A New Proposal for an Tntegrative Tnterplay Model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 628416. [CrossRef]

- Vrshek-Schallhorn, S., Velkoff, E. A. & Zinbarg, R. E. (2019). Trait rumination and response to negative evaluative lab-induced stress: neuroendocrine, affective, and cognitive outcomes. Cognition and Emotion, 33(3), 466-479. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (2023). Depressive disorder (Depression). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression.

- Yang, X., Garcia, K. M., Jung, Y., Whitlow, C. T., McRae, K., & Waugh, C. E. (2018). vmPFC activation during a stressor predicts positive emotions during stress recovery. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 13(3), 256-268. [CrossRef]

- Zareian, B., Wilson, J., & LeMoult, J. (2021). Cognitive Control and Ruminative Responses to Stress: Understanding the Different Facets of Cognitive Control. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 660062. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).