1. Introduction

Honey, as stated in Legislative Decree No. 179 of 21 May 2004, [

1] is ‘the natural sweet substance that bees (

Apis mellifera L.) produce from the nectar of plants or from secretions from living parts of plants or from substances secreted by sucking insects on living parts of plants that they forage, transform, combine with their own specific substances, deposit, dehydrate, store and allow to mature in the honeycombs of the hive’ [

2].

Attracted by the bright colours and smells of the flowers, the foraging bees use a special mouth structure, the ligule, to collect the nectar and hold it inside an oesophageal appendage, the bursa melaria, before regurgitating it back into the hive, where it will go on to the next stages of honey production thanks to the activity of the worker and fan bees. The honey, which is not yet ripe, is laid in thin layers and dehydrated by the fan bees, which, by swirling their wings, generate air flows that cause water to evaporate from the honey until an ideal aqueous concentration for storage is reached. From the foraging stage, the conversion of the sucrose present in the nectar into monosaccharides, glucose and fructose, begins through the catalytic activity of the invertase enzyme with which bees are equipped. When the honey is mature, it is finally stored and sealed in the comb cells [

2].

When collecting nectar, the bees load themselves with pollengrains, present on the visited flower, which remain trapped between the hairs covering their legs and body.

Honey is a highly energetic food due to its high concentration of monosaccharides, particularly glucose and fructose, which are rapidly assimilated without requiring a digestive process. The presence of disaccharides such as maltose and sucrose, and trisaccharides like melezitose, contributes to the sugar composition of honey. The water concentration in honey, influenced by various factors such as botanical origin, production season, and atmospheric conditions, is crucial for its preservation and quality [

3].

Honey contains a small percentage (0.2-2%) of nitrogen compounds, including free amino acids and enzymatic proteins such as glucose oxidase and invertase. The presence of amylase contributes to the breakdown of starch into glucose. Honey also contains minerals, primarily potassium, absorbed by plants and present in nectar. Both inorganic and organic acidic compounds, including gluconic acid, are present.

Traces of vitamins, mainly vitamin C and B-group vitamins, are found in honey due to pollen grains. Minor constituents such as aldehydes, ketones, esters, ethers, and phenols influence the organoleptic properties of honey, affecting its color and aroma. Phenolic compounds, though present in small quantities, play a significant role in the beneficial properties of honey [

4]

Honeyhas proven healing properties supported by contemporary scientific evidence. Acknowledging its dual nature as both nourishment and medicine, scientific research has validated honey’s efficacy in accelerating wound healing and re-epithelialization [

5,

6,

7].

Honey’s therapeutic effects result from a synergistic combination of its antibacterial activity [

8,

9,

10], osmotic and moisturizing action, and high viscosity [

11]. These properties collectively create a protective barrier that hinders pathogen penetration and fosters an optimal environment for rapid healing.

Described as eudermic, honey combines antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties with emollient, soothing, and moisturizing actions, leading to improved skin turgidity, elasticity, and tone.

Honey’s therapeutic prowess is rooted in its chemical and physical characteristics. Its high sugar content, hygroscopicity, acidic pH, and rich concentration of antioxidants, such as polyphenols and flavonoids, contribute to its healing potential [

12,

13]. Key amino acids present in honey, particularly proline, play a crucial role in the re-epithelialization phase, accounting for a significant portion of collagen composition [

14]). Experiments on human keratinocytes demonstrate honey’s ability to induce the expression of extracellular matrix metalloprotease (MMP-9), an enzyme involved in collagen degradation during tissue remodeling in wound repair [

15,

16,

17].

This study aims to delve into the skin protection abilities of various honey types, specifically five citrus varieties, (Citrusspp. L.), produced from the nectar collected from the flowers of plants of the ‘Citrus’ genus (to which lemon, orange, grapefruit, mandarin, citron and bergamot belong), one variety of acacia honey (Robinia pseudoacacia L.), one of chestnut honey (Castanea sativa Mill.) and, finally, one of multifloral honey.

This exploration seeks to uncover not only the healing potential of different honey types, but also to establish correlations between their chemical-physical properties and therapeutic effects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

Five different citrus honeys from lowland citrus-growing areas in the province of Chieti(CH), Acacia (Robinia pseudacacia), chestnut and multifloral honeys also used in this analysis were from Montalcino (Siena).

The samples were stored at +5-7°C and in the dark, optimal storage conditions to preserve the chemical and physical properties of the honey.

2.2. Water Content

The water contentmeasurement was performed using a portable refractometer, ATAGO HHR-2N, calibrated at a temperature of 20 °C.

A small quantity of the honey sample was spread on the prism provided, and after closing the glass dish, turning the refractometer toward the light, it was possible to read the value of the water content (expressed as percentage by weight, g of water per 100 g of honey). For measurements made at temperatures other than the calibration temperature, the values returned by the refractometer were corrected by the addition of a factor automatically determined by the instrument itself.

2.3. Determination of the Sugar Profile

The sugar profile was determined by Waters LC-Module 1 HPLC system coupled to a Waters RI 2410 refractive index detector. Honey samples were diluted 1:20 with Milli-Q water. Details of the instrumental method used, taken from an application sheet provided by Waters, are given in

Table 1:

2.4. Determination of Free Amino Acids

The determination of free amino acids was performed by Waters LC-Module 1 HPLC system coupled with Waters 470 Scanning Fluorescence detector, using a method taken from Ma et al. (2015) [

18]. Because the amino acids are not themselves visible by fluorimetry, it was necessary to derivatize them by employing 6-amino quinolyl-N-hydroxysuccinimidyl carbamate (AQC), which reacts with the primary and secondary amino acids, converting them into stable fluorescent derivatives.

Each honey sample was diluted 1:20 with Milli-Q water. Of this solution, 70 µL was taken to which 10 µL of AQC reagent, 20 µL of AccQ.Tag kit buffer was added. The solution was mixed on Vortex and then transferred to an oven at 55 °C for 15 min. Details of the experimental method used are described in

Table 2. Quantification was obtained by external standards method. The analyses were carried out in triplicate.

2.5. Determination of Total Polyphenols

Total polyphenols content (TPP) of honeys was evaluated by means of Folin-Ciocalteau (FC) colorimetric method as described in Finetti et al., 2020 [

19]: briefly, 100 µL of honey (100 mg/mL)was diluted to 3 mL with ddH

2O.; 500 µL of FC reactive diluted 10 fold in water (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy) were added, the mixture was shaked and, finally, 1000 µL of a 30% w/V sodium carbonate water solution were added. After incubation for 1 h in the dark at room temperature, absorbance of samples was read at 750 nm, using ddH

2O. Gallic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as reference standard. Calibration curve was created using gallic acid 5000 to 78 mg/l. The analyses were carried out in triplicate, thus calculating an average of the values obtained.

2.6. Total Flavonoid Content of Extracts

Total flavonoid content (TF) of different extracts was evaluated by means of spectrophotometric quantification and expressed as hyperoside [

20]. Briefly, samples (100 mg/mL) were diluted 10 folds in the distilled water and the absorbance was recorded at 353 nm, which is the maximum absorbance of quercetin (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan), used as a reference standard (calibration curve: 5000 to 78 mg/L).

The analyses were carried out in triplicate.

2.7. Qualitative Melissopalinological Characterization

10 g of honey (15-20 g in the case of pollen-poor honeys) was weighed into a conical-bottomed test tube to which 20 mL of distilled water (temperature not exceeding 40 °C) was added. The tube was subjected to centrifugation for 15 min at 2500 rpm. After this was finished, the supernatant was removed and the sediment resuspended with 10 mL of distilled water. Then, further centrifugation was carried out for 10 min at 2500 rpm. The supernatant obtained was removed and the sediment collected and spread evenly on a glass slide. This was covered and sealed with a coverslip on which a drop of glyceratedgelatin was placed. Finally, microscopic observation (at 40x or 100x magnification), recognition and counting of pollen grains were carried out. Recognition was done by comparison with melissopalinologicalatlases [

21,

22] and with reference preparations. Counts were performed on two slides prepared from the same honey independently to obtain greater reliability of the figure calculated as the average of the two values.

2.8. Antioxidant Activit

The radical scavenging activity of the honey samples was measured by means of the DPPH assay, as previously reported [

23]. Briefly, 10 µL of different concentrations (2-200 mg/mL) of the samples were added to 190 µL of freshly prepared methanolic DPPH solution (0.1 mM) and incubated for 30 min at rt in the dark with shaking. Then, absorbance was recorded at 517nm using a Victor

® Nivo™ plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). ddH2O was used as the blank control. The antiradical activity of the samples was calculated according to the following formula:

Data were plotted using Microsoft Excel for each sample.

2.9. Collagenase Inhibition Assay

Inhibitory effect of collagenase was performed using Collagenase Activity colorimetric Assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, MAK293). Assay kit measures proteolytic degradation when collagenase interacts with synthetic FALGPA, a synthetic peptide that mimics collagen’s structure, this leads to a reduction in the absorption of 340 nm in the presence of collagenase inhibitors. Absorbance of reaction mix was determined at 5 min intervals for 20 min. Collagenase activity (U/mL) and subsequent percentual inhibition produced by honey sample was calculated.

2.10. Cell Cultures

Human keratinocytes (HaCaT) cells were cultured in 75-cm³ flasks (Euroclone, Milan) in high-glucose DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium) medium (4500 mg/l) supplemented with 10% m/V FBS (Fetal Bovine Serum, Sigma-Aldrich, Milan) and 1% m/V L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich,Milan, Italy), incubating at 37 °C in a humid atmosphere enriched with CO₂ (5%). The cells were then removed from the flasks by employing trypsin-EDTA solution (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy). Cell counts were performed microscopically (Leica, Milan, 25x) using a hemocytometer.

2.11. Cell Viability

Cell viability assay was performed using Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy) on human keratinocytes (HaCaT) treated for 24 hours with extracts of the various honeys prepared at three different concentrations: 10 mg/mL, 1 mg/mL, 0.1 mg/mL.The cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5000 cells per well in DMEM and 10% FBS and allowed to grow until they occupied about 70% of the same,incubated for 24 hours at a temperature of 37 °C in a humid atmosphere enriched with CO₂ (5%). After 24 hours, the complete medium was aspirated to be then replaced by fresh medium with a lower percentage of FBS (3% m/V). Then treatments were performed with the honeys at the different concentrations. CCK-8 was added for each well at a ratio of 1:10 to the total volume of the sample well, and after two hours, spectrophotometric readings were taken with aa Victor® Nivo™ plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA), at a wavelength of 450 nm.

2.12. Proliferation Assay

The same test was repeated by also treating the cells with methylprednisolone 1 mg/mL (Euroclone, Milan), used as a cell viability inhibitor. Methylprednisolone was used alone or in cotreatment with the honeys. After 24hwas aspirated and replaced by fresh medium. CCK-8 was added at a ratio of 1:10 to the total volume of the well and, after two hours, spectrophotometric readings were taken with a Victor plate reader at a wavelength of 450 nm.

2.13. Statistical Data

The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed using the open-source software R (version 4.0.3, base library), operating on a dataset consisting of the results of amino acids and carbohydrates determinations of all analyzed honey samples. The data matrix was standardized (as the observations were expressed in different units), applying the z-standardization technique, before extracting the principal components, whose number was chosen based on the methodology proposed by Joliffe (1972) [

24]The choice of PCA technique to obtain clustering of observations (instead of cluster analysis) was driven by the desire to seek a chemical-physical interpretation of the classification, through the dimensionality reduction of data, summarized in the new derived variables. Furthermore, PCA also allows for visually depicting relationships among latent variables, which is essential for the objectives of this study aimed at investigating causes and differences in the eudermic properties of different types of honey.

The statistical difference of the test results between the different samples was determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Student’s t-test. Statistically significant values were those with p<0.05 against the reference considered. Graphs and calculations were performed using the Microsoft Excel.

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Determination of Water Content

Data on the water content of honeys, obtained by refractometer measurement, are shown in

Table 3.

The results show a water content less than or equal to 18%, a condition that would prevent the occurrence of fermentation processes that would compromise the quality of the product. So, all samples have an optimal moisture content to ensure good honey preservation.

3.2. Determinationof the Sugars

The carbohydrates most represented in all the honey samples are the two monosaccharides glucose and fructose, as can be seen from

Table 4, with the concentration of fructose slightly higher than that of glucose.

Also present are traces of the trisaccharide melezitose and pectins (heteropolysaccharides) in rather similar concentrations in citrus honeys, higher in acacia, chestnut and multifloral honeys. Higher sucrose concentrations are recorded in multifloral and chestnut honeys, however, the dominant sugars are always glucose and fructose in agreement with literature data [

2].

3.3. Determination of Free Amino Acids

The quality profile of free amino acids in the honeys analysed includes: glutamic acid, alanine, β-alanine, arginine, asparagine, phenylalanine, glycine, isoleucine, histidine, leucine, lysine, ornithine, proline, serine, taurine, tyrosine, threonine, valine.

Among the various amino acids quantified, the concentration of proline is remarkablythe highestin all honeys, with a maximum value of 4866 nmol/mL recorded in multifloral honey (

Table 5). This evidence is particularly significant given the role of this amino acid in the collagen biosynthesis process [

25].

3.4. Determination of Total Polyphenols and Flavonoids and Antioxidant Power

The results of the analysis for the determination of polyphenols and total flavonoids are shown in

Table 6. Undoubtedly, a particular abundance of these antioxidant compounds emerges in chestnut and multifloral honey, which is in agreement with the relevant literature [

26].

In the first, a concentration of 762.13 mg/Kg was recorded (highest value among the honeys analysed) for total polyphenols and 514.45 mg/Kg for total flavonoids. In the second, a concentration of 688.14 mg/Kg was recorded for total polyphenols, while the highest value among the honeys analysed, 540.46 mg/Kg, was recorded for total flavonoids.

Considerably lower concentrations of total polyphenols and flavonoids were found in citrus and acacia honeys, where the values ranged from a minimum of 201.92 mg/Kg (citrus honey 2) to a maximum of 293.97 mg/Kg (acacia honey) for polyphenols, and from 46.82 mg/Kg (citrus honey 4) to 58.67 mg/Kg (acacia honey) for flavonoids.

3.5. Antioxidant Activity

These data therefore make it possible to understand and interpret the results of the DPPH assay, shown in

Table 7, from which a clear correlation between polyphenol content and antioxidant activity concentration of 10 mg/mL is remarkable. On the other hand, no significant antioxidant activity has been attested for multifloral honey (8.77%), despite its abundance in polyphenols and flavonoids. Finally, the lack of antioxidant power on the part of citrus honeys and no appreciable activity on the part of acacia honey, given their low polyphenol and flavonoid content, is not surprising.

3.5. Qualitative Melissopalinological Characterization

Melissopalynological analyses were a key step in confirming the botanical origin of the honeys as they made it possible to identify the flowers from which the bees foraged the nectar needed to produce the honey.

All analysed honeys except, of course, the multifloral honey were ascertained to be monofloral varieties (

Table 8). In chestnut honey, a percentage of 92% of chestnut pollen grains was calculated (over-represented species), in acacia honey, a considerable percentage of 25% was reached, being a hypo-represented species (15% acacia pollen is sufficient to define monofloral honey [

27]. The results for citrus honeys were very satisfactory, with percentages ranging from 33% to 56% citrus pollen grains (in this case, the pollen percentage required to consider honey unifloral is above 10% [

28].

On the other hand, the microscopic recognition of multifloral honey showed an abundance of chestnut pollen grains (51%) in this variety of multifloral honey. This finding can be correlated with the very similar values of total polyphenols and flavonoids that this honey shares with chestnut honey.

In addition to the pollens mentioned above, pollen grains of sulla (HedysarumcoronariumL.), grass, acacia and sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) pollen were recognised in the honey sediments. Amongst these, the percentage of sulla pollen found in citrus honeys 1 and 5 was rather conspicuous, where percentages of 21% and 22%, respectively, were calculated. Abundant, however, in the sediment of citrus honey 3, was the presence of honeydew.

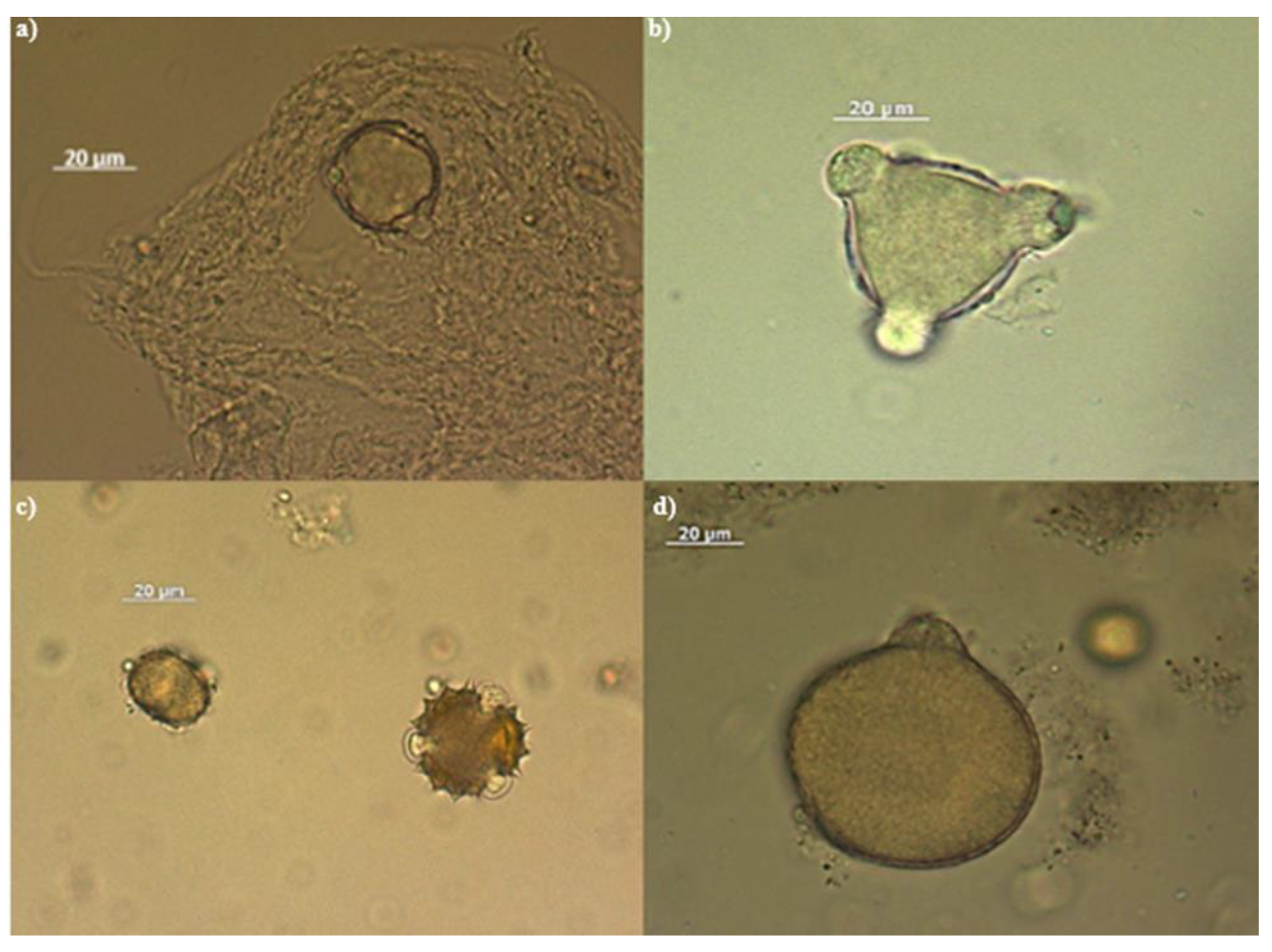

Figure 1.

Photographs of some pollens recognised in the analysed honeys. Top from left: a)Traces of honeydew and citrus pollen granule; b) Acacia pollen (Robinia pseudacacia); c) Pollen granule of sulla on the left, of sunflower on the right; d) Grass pollen granule.

Figure 1.

Photographs of some pollens recognised in the analysed honeys. Top from left: a)Traces of honeydew and citrus pollen granule; b) Acacia pollen (Robinia pseudacacia); c) Pollen granule of sulla on the left, of sunflower on the right; d) Grass pollen granule.

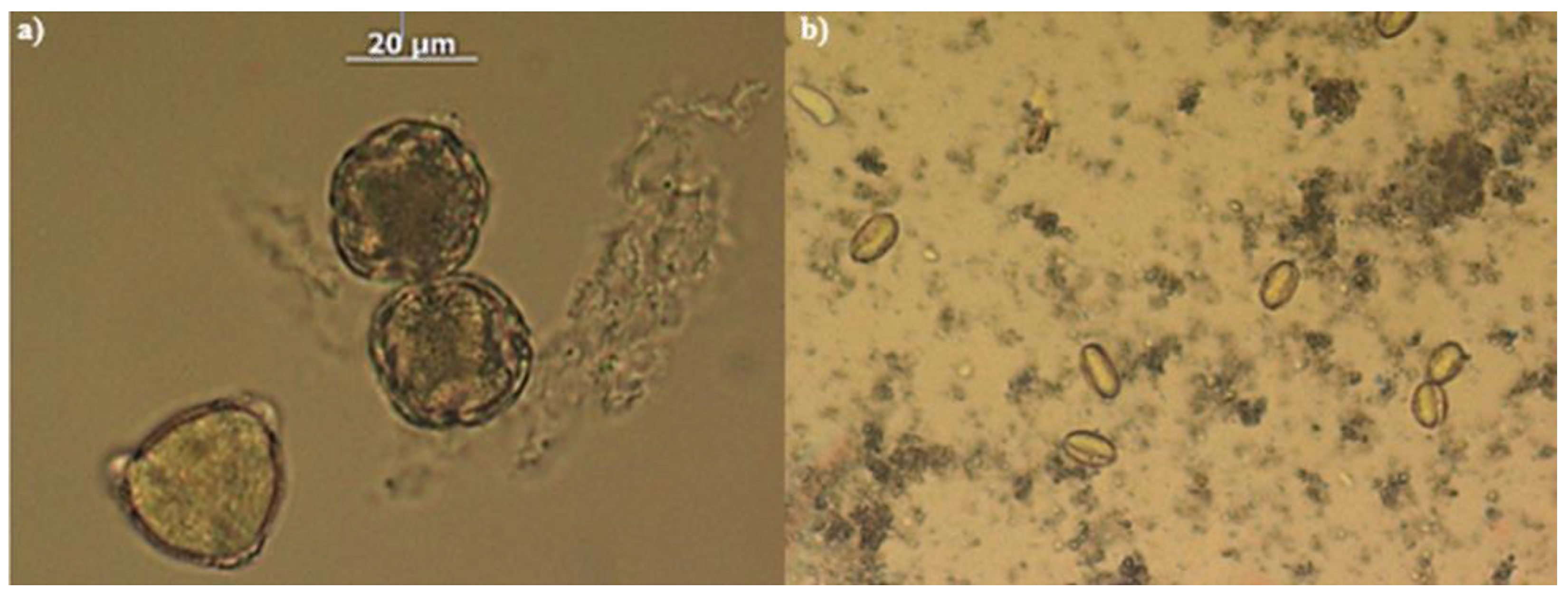

Figure 2.

Photographs of some pollens recognised in the analysed honeys. From left: a) Pollen from Citrus spp;b)Chestnut pollen.

Figure 2.

Photographs of some pollens recognised in the analysed honeys. From left: a) Pollen from Citrus spp;b)Chestnut pollen.

3.6. Collagenase Inhibition Assay

The collagenase inhibition assay, as well as the subsequent ones on cell cultures, was performed on five honeys, selecting two of the citrus honeys (1 and 3, chosen from the 5 honeys with high amino acid content and different pollen percentages), chestnut honey, acacia honey and multi-flower honey.

The results of the analysis, shown in

Table 9, revealed a modest but detectable collagenase-inhibiting power of citrus honey 3 (7.09%) and 1 (6.45%), followed by chestnut honey (5.71%), at a concentration of 10 mg/mL.

On the other hand, at the same concentration no decreasing effect on collagenase functionality was observed from acacia honey and multifloral honey. At the lower concentrations tested, no honey provided effacacy data.

3.7. In Vitro Experimentation

The two tests on keratinocytes had different modes of execution and objectives. In the first test, cells cultured in low-serum medium, i.e., under conditions mimicking the normal condition of keratinocytes in intact human epidermis, were treated for 24 hours with the honeys at different concentrations (0.1, 1, 10 mg/mL), and the objective of the test was to assess the influence of the samples in modulating the metabolic response compared to untreated controls. In the second test, the cells were treated for 24 hours with a cortisone that minimises the metabolic activity of keratinocytes and mimics an aged epidermis condition. The objective of this test was to verify the possible counteracting effect of the cortisone by the honeys.

The results obtained in cell tests on human keratinocytes showed that the tested honeys all have a relevant influence in positively modulating the cellular metabolic response.

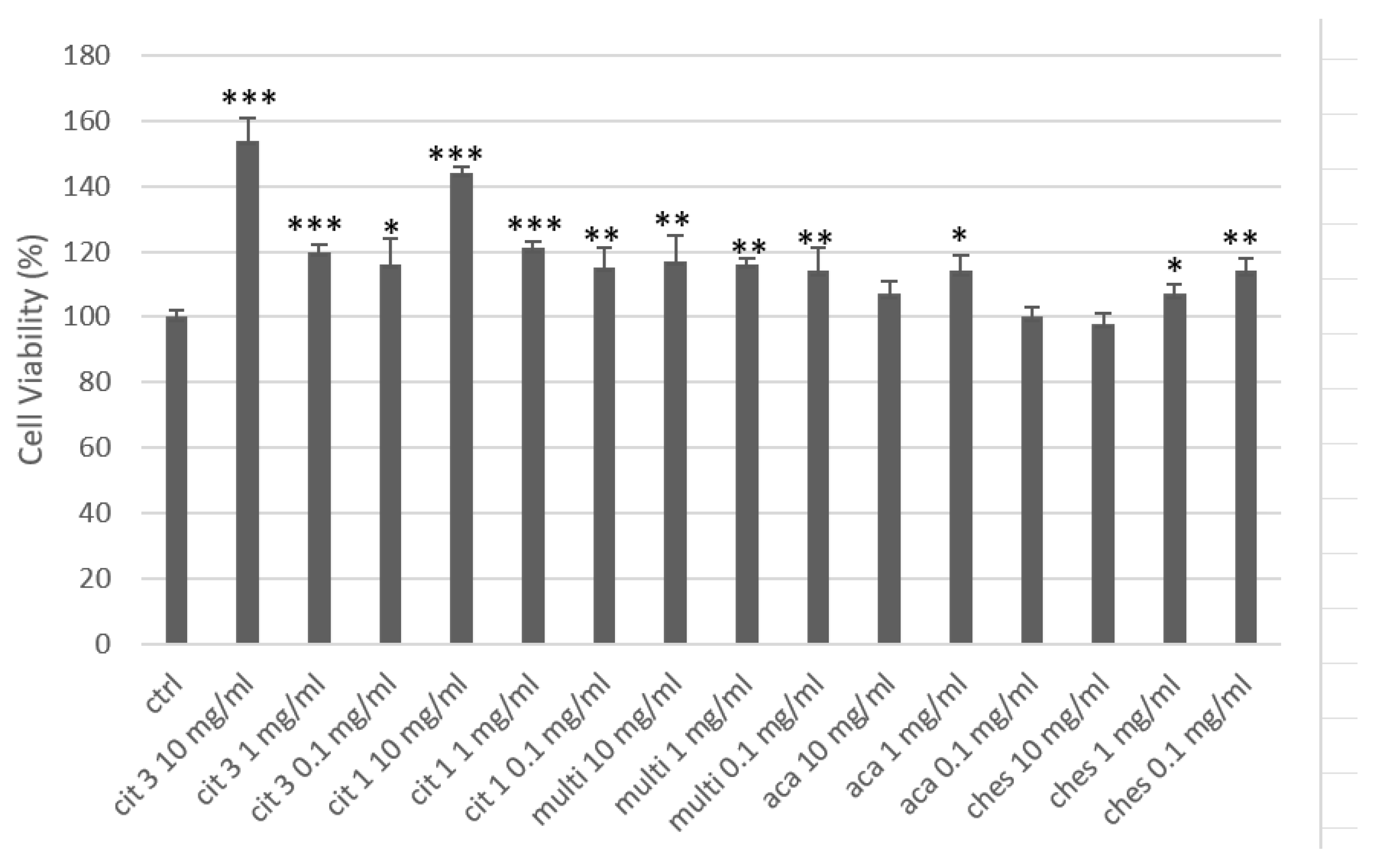

Under basal conditions, all five honeys showed efficacy in increasing keratinocyte cell metabolism (

Figure 3). The two citrus honeys were the most effective, with a concentration-dependent effect. Citrus honey 3 (CIT 3) at 10 mg/mL, increased metabolism and cell viability by more than 50% compared to the control, which was highly significant. Citrus honey 1 (CIT 1) had a similar effect, only slightly less: +44% compared to the control. At concentrations of 1 and 0.1 mg/mL, both honeys significantly increased cell viability by approximately 20% and 15% respectively compared to the control, with no significant difference between the two honeys. Multifloral honey (Multi) showed very similar cell viability increase data, at the three concentrations, of about 15% compared to the control. Acacia honey (ACA)isthe one that gave the least obvious results in this test: the changes in increased viability compared to the control were only significant at 1 mg/mL (+14% vs control). Chestnut honey (Chest) showed a different behaviour, i.e., an effect inversely correlated with the concentration used: the best efficacy figure was at 0.1 mg/mL (+14%

vs ctrl), the worst at 10 mg/mL, with a total loss of efficacy. The reason for this effect of chestnut honey is to be found in its high polyphenol content (the highest among the samples tested), which exerts a known anti-inflammatory power that can in fact minimise the trophic effect characteristic of the honey phytocomplex; the effect is already reported in the literature and also widely observed in the Pharmaceutical Biology laboratory in which we carried out part of this experimental work [

29].

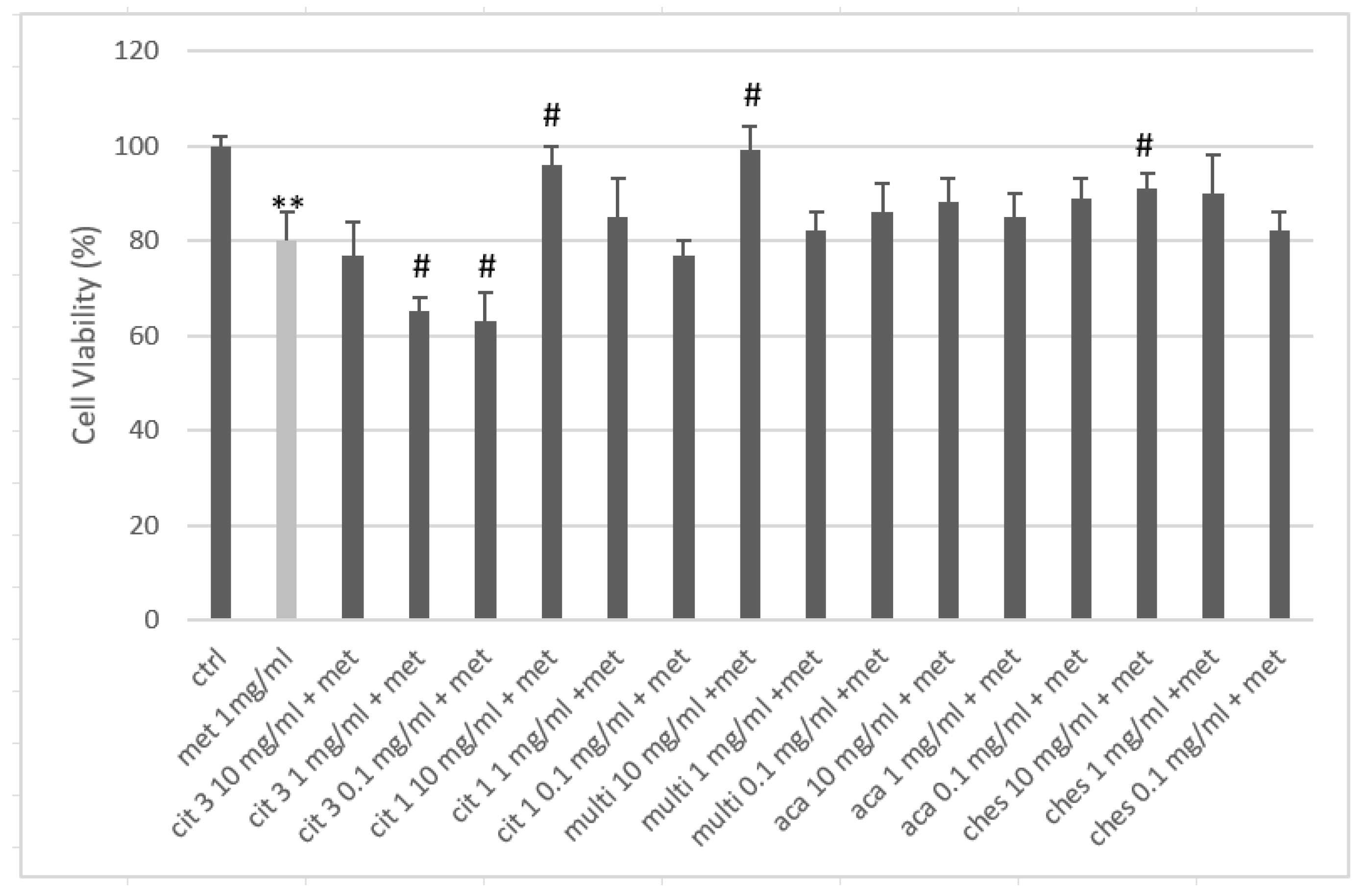

After co-treatment with the methylprednisolone 1 mg/mL (Met 1 mg/mL), the cell viability of the keratinocytes was reduced by 20%, confirming the premise of the experimental model used. With the exception ofCIT 3 at all concentrations and CIT 1 at the concentration of 0.1 mg/mL, allthe other samples tested resulted in an improvement in cell viability compared to the cell groups stimulated with cortisone alone (

Figure 4). The cell viability resulted in an increase of more than 50% for CIT 1 and multifloral honey at 10 mg/mL (with almost complete suppression of the negative effect of the cortisone) and for Chest at 10 mg/mL, compared to the cortisone treatment. The figure for chestnut honey is further confirmation of how the anti-inflammatory effect of polyphenols modulates the trophic activity of keratinocytes. Acacia honey showed a mild positive effect, but never significant as a change compared to the control. The effect of CIT 3 was noteworthy which, in co-treatment with cortisone, was worse than the cortisone itself. The reason for this effect is not clearly identifiable from the tests performed but can plausibly be found in a synergistic interaction on the glucocorticoid receptor response of the keratinocytes.

Overall, broad considerations can be produced from the keratinocyte tests and application implications deduced. All honeys tested proved effective in promoting an improved of keratinocyte viability and metabolism under normal conditions. However, CIT 1, Multi and Chest have also been shown to increase cellular activity under conditions of slowed vitality.

3.8. Exploratory Data Analysis

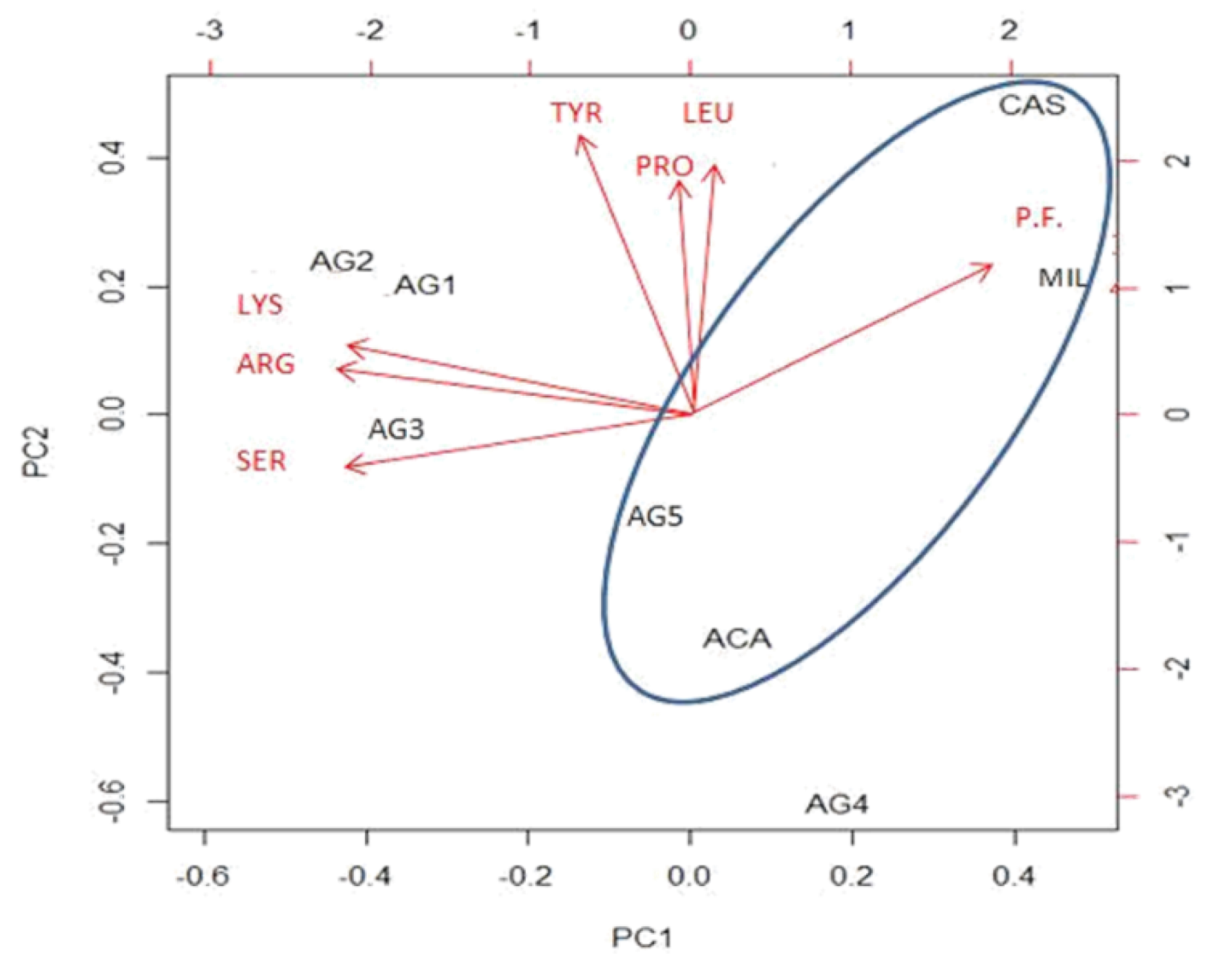

Figure 5 shows the percentages of variance explained by the principal components obtained. The first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) cumulatively explain 67% of the variance.

This percentage makes it possible to project the representative sample vectors onto a two-dimensional space (PC1 and PC2), the graph of which is shown in

Figure 6, retaining approximately 70 per cent of the information.

The red arrows on the graph indicate the most significant original variables, represented as vectors. It is evident that all citrus honeys are located below or close to the bisectors of quadrants IV and II, whereas multifloral and chestnut honey are well separated in the upper right-hand corner. Considering that a high percentage of chestnut pollen was found in the multifloral honey, it is evident that PCA on the metabolites analysed is a powerful tool for identifying the botanical origin of honey.

Interestingly, along the dimension represented by PC2 we find arranged precisely those honeys tested for collagenase-inhibiting action, ordered, from bottom to top, from most effective to least effective. Consequently, it is possible to interpret PC2 as a variable measuring the action of honey on collagenase. The amino acid that contributes most on this axis is tyrosine, whose influence on collagenase activity is unknown. Other significant amino acids on PC2 are leucine (LEU), proline (PRO), valine (VAL) and ornithine (ORN). The blue oval identifies honeys that have been shown to exert some antioxidant action, first of which is chestnut honey, followed by acacia honey, multifloral honey and citrushoney 5. Geometrically, it can be observed that the polyphenol carrier has the greatest influence on antioxidant activity, confirming what has been seen in laboratory tests. On PC1, the most important analytes are the amino acids serine (SER), arginine (ARG), lysine (LYS), the sugars sucrose and melezitose, and polyphenols.

4. Conclusions

The aim of this work was to test the eudermic properties of honeys in order to assess their natural efficacy in exerting skin protection activity. The analyses carried out allowed us to investigate the relationship between the botanical origin of honey and its therapeutic properties, finding that honeys of different botanical origins are able to exert different biological effects.

Among the honey samples tested, five were selected for the in vitro experiments: chestnut honey, chosen for its richness in polyphenol content, followed by multi-flower honey; citrus honeys 1 and 3, for their amino acid composition; and acacia honey, for obvious comparison.

This comparative study on Italian honeys with different chemical-physical characteristics and botanical origin adds information on how this bee product can be an important resource for skin care and provides positive experimental evidence to what was suggested in the

review by Burlando and Cornara (2012) [

30]concerning the use of honey in dermatology.

With the aim of going beyond the healing effect, other elements for skin protection were also taken into consideration in this research work, in particular the antioxidant action, a basic element for protection from solar radiation and atmospheric pollution, at the basis of skin ageing, and the activity on the enzyme collagenase, an important target in chrono- and photo-induced ageing because it is responsible for the degradation of collagen produced by skin fibroblasts, which guarantees vigour to the dermal layer and maintenance of skin texture.

The honeys tested did not have a high antioxidant potency, but chestnut honey stood out in this test, showing the importance, decisive for this biological effect, of the polyphenols present in the phytocomplex. Chestnut honey and citrus 3 honey also distinguished themselves by having a modest but detectable collagenase-inhibiting effect at 10 mg/mL. The data obtained in in vitro tests all agreed on an ideal active concentration of the honeys at 10 mg/mL, i.e., 1% m/m. Also noteworthy is the noted importance of the pool of amino acids tyrosine (especially), valine, leucine, proline, and ornithine on collagenase activity, an aspect that certainly merits further investigation.

In conclusion, this research work, brings new scientific knowledge on the use of honey in dermatology and highlights in particular two territorial excellences such as citrus and chestnut honey, chemically characterised, one by a rich amino acid profile, which plays a fundamental role in maintaining skin homeostasis [

31], the other by an abundant concentration of polyphenols, which intervene by modulating cellular ageing processes [

32].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M. and G.B.; Methodology, G.C. and G.B.; Validation, E.G. and E.M.; Formal Analysis, C.DC. and M.G.; Investigation, M.N. and E.M.; Data Curation, M.B.; Writing–Original Draft Preparation, G.B.; Writing–Review & Editing, E.M. and M.N..; Visualization, M.B.; Supervision, E.M. and G.B.; Project Administration, E.M. and G.B.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gazzetta Ufficiale. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/gazzetta/serie_generale/caricaDettaglio?dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2003-08-11&numeroGazzetta=185 (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Sabatini, G.A.; Bortolotti, L.; Marcazzan, G.L. Conoscere Il Miele; Sabatini, A.G., Bortolotti, L., Marcazzan, G.L., Eds.; 2nd ed.; Edizioni Avenue Media, 2007.

- Alghamdi, B.A.; Alshumrani, E.S.; Saeed, M.S. Bin; Rawas, G.M.; Alharthi, N.T.; Baeshen, M.N.; Helmi, N.M.; Alam, M.Z.; Suhail, M. Analysis of Sugar Composition and Pesticides Using HPLC and GC–MS Techniques in Honey Samples Collected from SaudiArabian Markets. Saudi J Biol Sci 2020, 27, 3720–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasupuleti, V.R.; Sammugam, L.; Ramesh, N.; Gan, S.H. ; Honey, Propolis, and Royal Jelly: A Comprehensive Review of Their Biological Actions and Health Benefits. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 2017, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molan, P.C. Potential of Honey in the Treatment of Wounds and Burns. Am J Clin Dermatol 2001, 2, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandamme, L.; Heyneman, A.; Hoeksema, H.; Verbelen, J.; Monstrey, S. Honey in Modern Wound Care: A Systematic Review. Burns 2013, 39, 1514–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minden-Birkenmaier, B.A.; Bowlin, G.L. Honey-Based Templates in Wound Healing and Tissue Engineering. Bioengineering (Basel) 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, J.; Dryden, M.; Patton, T.; Brennan, J.; Barrett, J. The Antimicrobial Activity of Prototype Modified Honeys That Generate Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Hydrogen Peroxide. BMC Res Notes 2015, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryden, M.; Lockyer, G.; Saeed, K.; Cooke, J. Engineered Honey: In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity of a Novel Topical Wound Care Treatment. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2014, 2, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, V.C.; Harrison, J.; Cox, J.A.G. Dissecting the Antimicrobial Composition of Honey. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasaudi, S. The Antibacterial Activities of Honey. Saudi J Biol Sci 2021, 28, 2188–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunnill, C.; Patton, T.; Brennan, J.; Barrett, J.; Dryden, M.; Cooke, J.; Leaper, D.; Georgopoulos, N.T. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Wound Healing: The Functional Role of ROS and Emerging ROS--modulating Technologies for Augmentation of the Healing Process. Int Wound J 2017, 14, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yupanqui Mieles, J.; Vyas, C.; Aslan, E.; Humphreys, G.; Diver, C.; Bartolo, P. Honey: An Advanced Antimicrobial and Wound Healing Biomaterial for Tissue Engineering Applications. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvo, J.; Sandoval, C.; Schencke, C.; Acevedo, F.; del Sol, M. Healing Effect of a Nano-Functionalized Medical-Grade Honey for the Treatment of Infected Wounds. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caley, M.P.; Martins, V.L.C.; O’Toole, E.A. Metalloproteinases and Wound Healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2015, 4, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majtan, J.; Kumar, P.; Majtan, T.; Walls, A.F.; Klaudiny, J. Effect of Honey and Its Major Royal Jelly Protein 1 on Cytokine and MMP--9 MRNA Transcripts in Human Keratinocytes. Exp Dermatol 2010, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majtan, J.; Bohova, J.; Garcia-Villalba, R.; Tomas-Barberan, F.A.; Madakova, Z.; Majtan, T.; Majtan, V.; Klaudiny, J. Fir Honeydew Honey Flavonoids Inhibit TNF-α-Induced MMP-9 Expression in Human Keratinocytes: A New Action of Honey in Wound Healing. Arch Dermatol Res 2013, 305, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhao, D.; Li, X.; Meng, L. Chromatographic Method for Determination of the Free Amino Acid Content of Chamomile Flowers. PharmacognMag 2015, 11, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finetti, F.; Biagi, M.; Ercoli, J.; Macrì, G.; Miraldi, E.; Trabalzini, L. PhaseolusVulgaris, L. Var. Venanzio Grown in Tuscany: Chemical Composition and In Vitro Investigation of Potential Effects on Colorectal Cancer. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetti, A.; Faraloni, C.; Venturini, S.; Baini, G.; Miraldi, E.; Biagi, M. Characterization of Phenolic Profile and Antioxidant Activity of the Leaves of the Forgotten Medicinal Plant Balsamita Major Grown in Tuscany, Italy, during the Growth Cycle. Plant Biosystems–An International Journal Dealing with all Aspects of Plant Biology 2021, 155, 908–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardelli D’Albore GMediterraneanMelissopalynology, Università degli Studi Di Perugia, 1998.

- Ricciardelli D’Albore, G. ; Persano Oddo L Istituto Sperimentale per la zoologia agraria. 1978,.

- Governa, P.; Manetti, F.; Miraldi, E.; Biagi, M. Effects of in Vitro Simulated Digestion on the Antioxidant Activity of Different Camellia Sinensis (L.) Kuntze Leaves Extracts. European Food Research and Technology 2022, 248, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal Component Analysis: A Review and Recent Developments. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbul, A. Proline Precursors to Sustain Mammalian Collagen Synthesis. J Nutr 2008, 138, 2021S–2024S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güneş, M.E.; Şahin, S.; Demir, C.; Borum, E.; Tosunoğlu, A. Determination of Phenolic Compounds Profile in Chestnut and Floral Honeys and Their Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities. J Food Biochem 2017, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matkovits, A.; Nagy, K.; Fodor, M.; Jókai, Z. Analysis of Polyphenolic Components of Hungarian Acacia (Robinia Pseudoacacia) Honey; Method Development, Statistical Evaluation. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2023, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiente, J.M.; Juan-Borrás, M.; López-García, F.; Escriche, I. Automatic Pollen Recognition Using Convolutional Neural Networks: The Case of the Main Pollens Present in Spanish Citrus and Rosemary Honey. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2023, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiocchio, I.; Poli, F.; Governa, P.; Biagi, M.; Lianza, M. Wound Healing and in Vitro Antiradical Activity of Five Sedum Species Grown within Two Sites of Community Importance in Emilia-Romagna (Italy). Plant Biosyst 2019, 153, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlando, B.; Cornara, L. Honey in Dermatology and Skin Care: A Review. J Cosmet Dermatol 2013, 12, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, H.; Shimbo, K.; Inoue, Y.; Takino, Y.; Kobayashi, H. Importance of Amino Acid Composition to Improve Skin Collagen Protein Synthesis Rates in UV-Irradiated Mice. Amino Acids 2012, 42, 2481–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, J.A.; Katiyar, S.K. Skin Photoprotection by Natural Polyphenols: Anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant and DNA Repair Mechanisms. Arch Dermatol Res 2010, 302, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).