Submitted:

12 September 2024

Posted:

14 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Bacterial Sources of Antimicrobials

3. Bacterial Sources of Antifungal Compounds

4. Fungal Sources of Antimicrobials

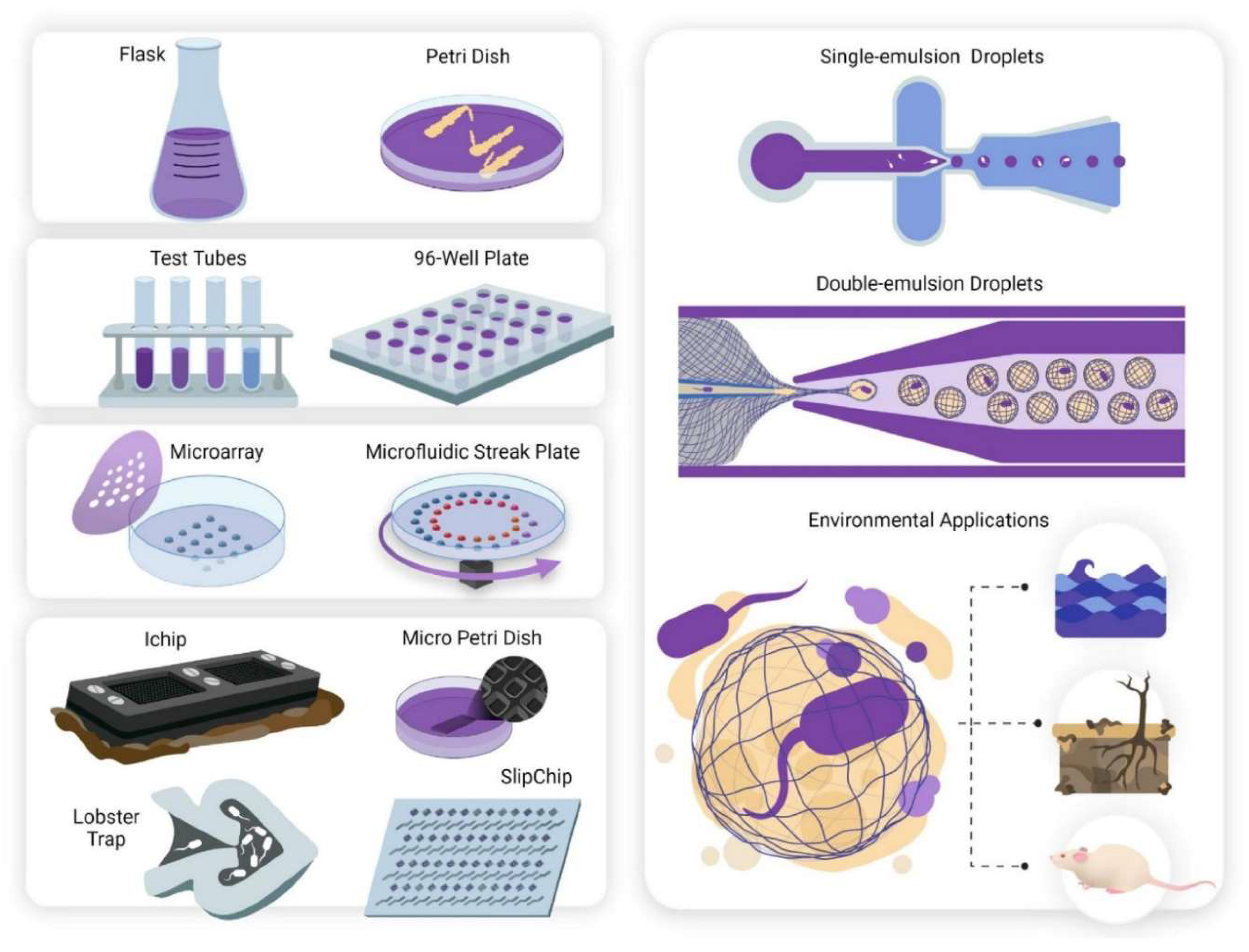

5. Advances in Micro-Culturing Technology

6. Microarrays

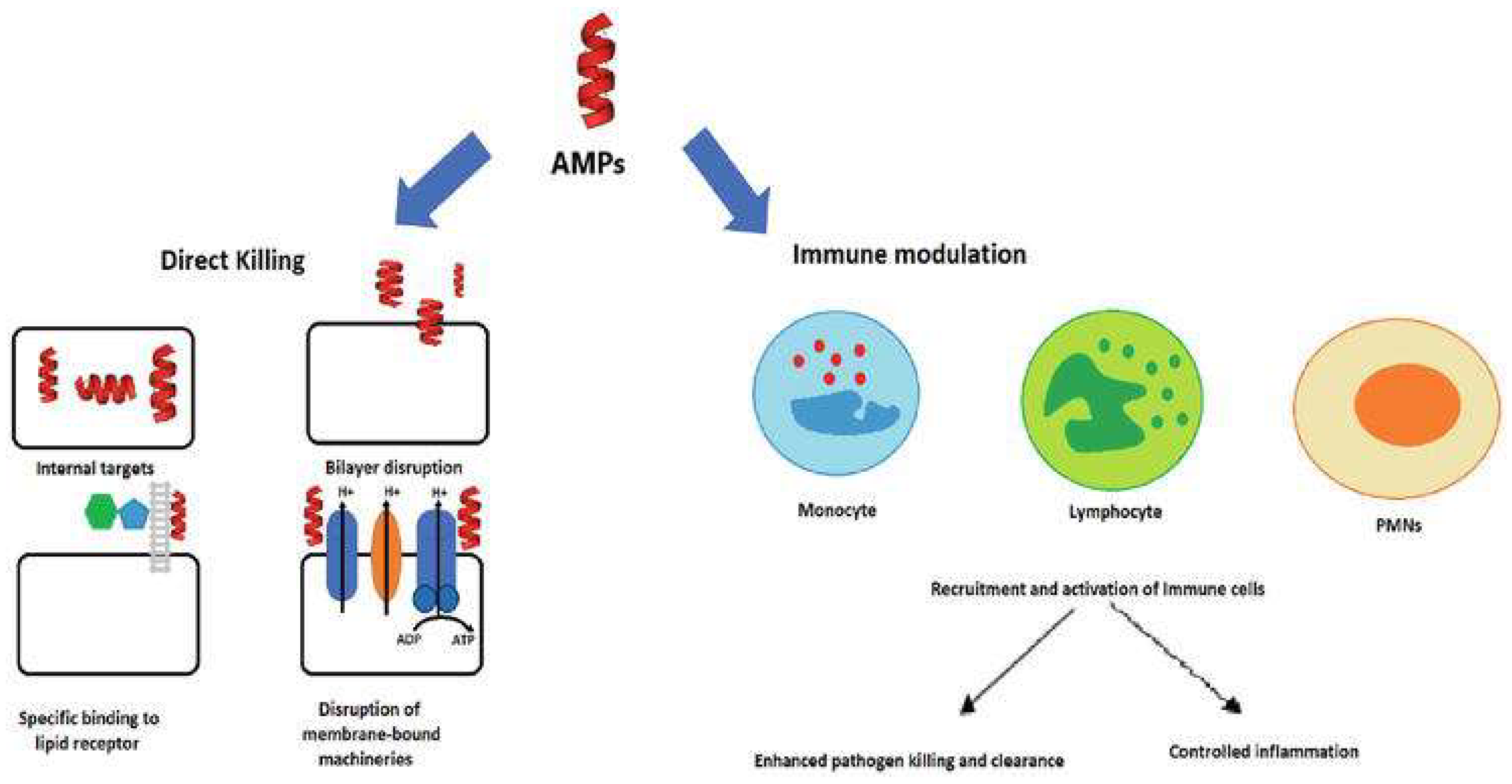

7. Antimicrobial Peptides

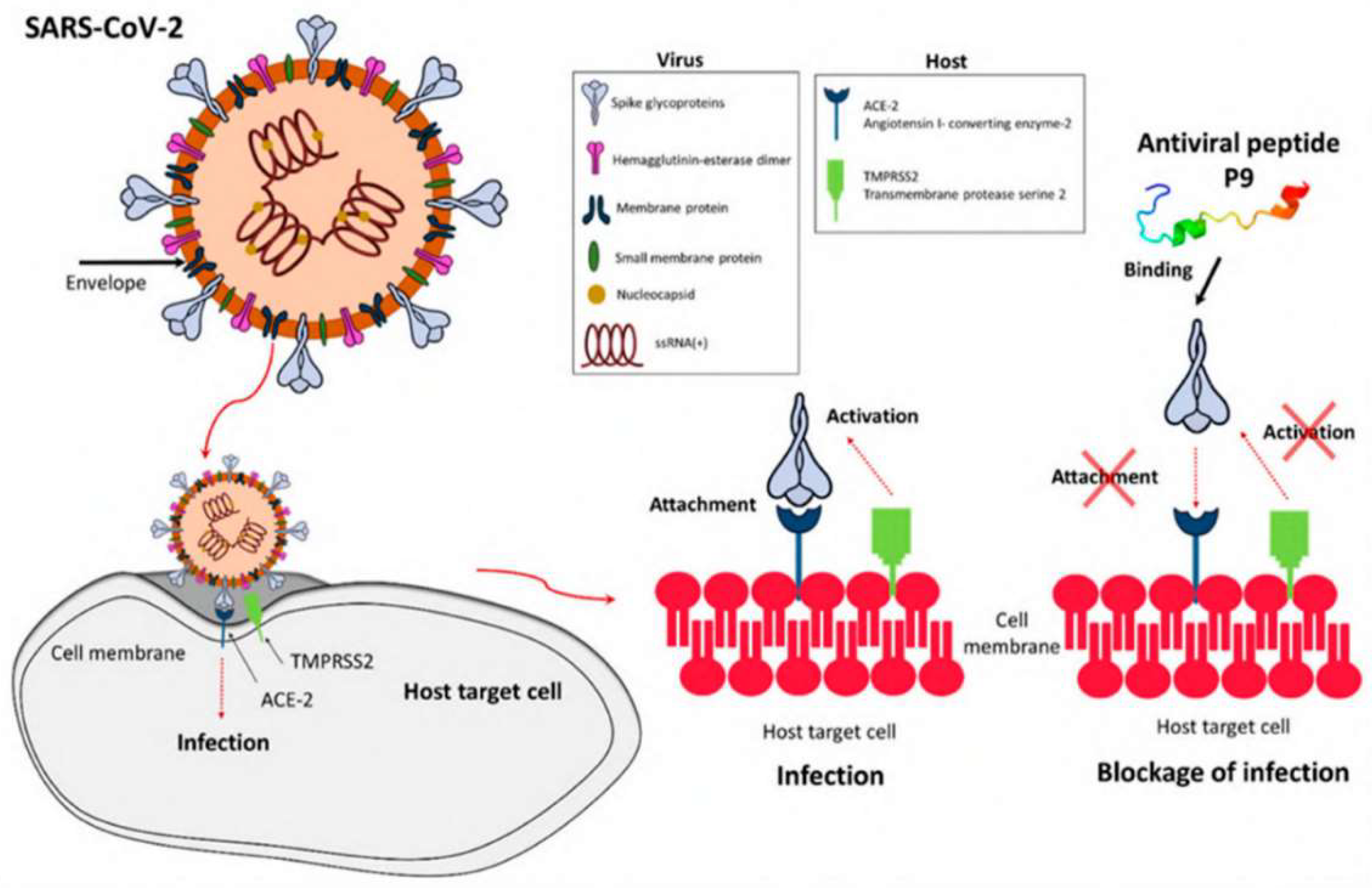

8. Antiviral Peptides

9. Microorganisms Affect Climate Change

10. Terrestrial Biome

11. Climate Change Affects Microorganisms

12. Infectious Diseases

13. Tools and Techniques

- Examples of diffusion processes include Agar discs, antimicrobial gradients, wells, plugs, cross streaks, and poisoned food. The agar disc diffusion method was created in 1940 to determine bacterial resistance [159]. Detecting some bacterial infections is difficult [160]. This comprises Streptococci, H. influenzae, N. gonorrhoea, N. meningitidis, and H. parainfluenzae. Agar-grown bacteria are exposed to a predefined dosage of the test chemical in this assay. The test compound's antimicrobial properties permeate into the agar, stopping the growth of sensitive bacteria. The zone's diameter is measured when a growth inhibitor is used [161,162]. Agar disc diffusion is a simple and cost-effective method for determining the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). Nevertheless, the outcomes are imprecise. [161].

- The antimicrobial gradient technique (Etest) may be utilized to calculate the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antibacterials, antifungals, and other antimicrobials, which combines dilution and diffusion techniques. This technique can also be utilized to analyze medication interactions [161,163,164,165].

- Several methods exist for screening and determining the susceptibility of microorganisms to antimicrobial medications. These include the time-kill test [168], the ATP bioluminescence assay [169,170,171,172], and the flow-cytofluorometric approach [173]. ATP bioluminescence has allowed for the evaluation of cellular ATP levels. The luciferin-luciferase bioluminescent test is popular due to its high sensitivity. A high quantum yield chemiluminescent reaction with MgATP2+ oxidizes luciferin catalytically via the luciferase. Light intensity correlates with ATP levels under ideal conditions. Stimulating ATP release from a disintegrating cell to react with luciferin-luciferase and produce light can determine cellular ATP. A luminometer is used to quantify the brightness of an object.

- A flow cytometer and flow cytofluorometric approach can identify antimicrobial resistance and predict the chemical's effect on microbe cell damage and viability [174].

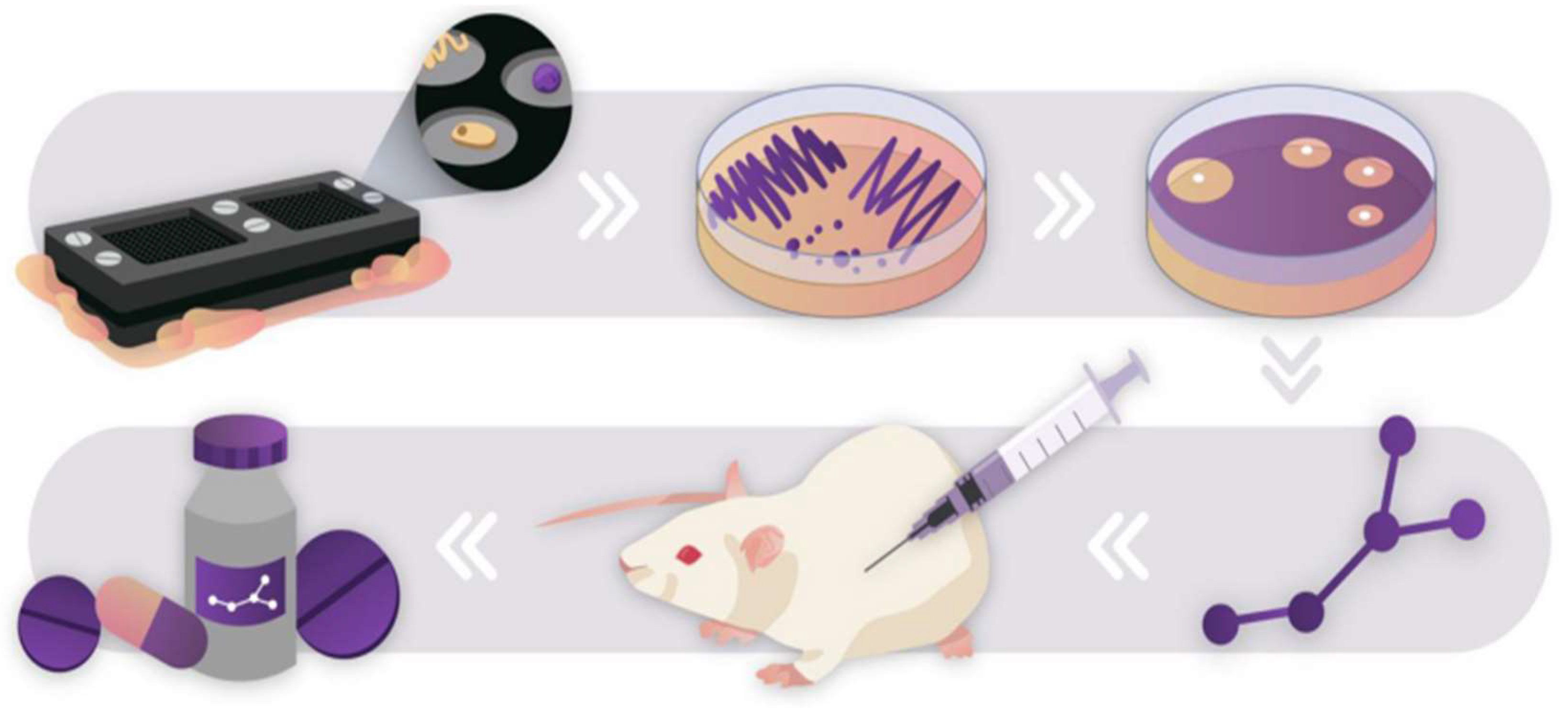

14. Micromachined Devices

15. Single Emulsion Droplet Microfluidics

16. Double Emulsion Droplet Microfluidics and Polymer-Based Nanocultures

17. Applications of Microbial-based Microsystems and Perceived Challeanges

18. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O'Neill, J. 2014. Antimicrobial Resistance: Tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. Rev. Antimicrob. Resist.

- Laws, M.; Shaaban, A.; Rahman, K.M. 2019. Antibiotic resistance breakers: Current approaches and future directions. FEMS Microbiol. Rev., 43, 490–516.

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. 2012. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the 30 years from 1981 to 2010. J. Nat. Prod., 75, 311–335. [CrossRef]

- Elissawy, A.M.; Dehkordi, E.S.; Mehdinezhad, N.; Ashour, M.L.; Pour, P.M. 2021. Cytotoxic Alkaloids Derived from Marine Sponges: A Comprehensive Review. Biomolecules, 11, 258. [CrossRef]

- El-Demerdash, A.; Tammam, M.A.; Atanasov, A.G.; Hooper, J.N.A.; Al-Mourabit, A.; Kijjoa, A. 2018. Chemistry and Biological Activities of the Marine Sponges of the Genera Mycale (Arenochalina), Biemna and Clathria. Mar. Drugs, 16, 214. [CrossRef]

- Karpinski, T.M. 2019. Marine Macrolides with Antibacterial and/or Antifungal Activity. Mar. Drugs, 17, 241. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Meng, W.; Cao, C.; Wang, J.; Shan, W.; Wang, Q. 2015. Antibacterial and antifungal compounds from marine fungi. Mar. Drugs, 13, 3479–3513. [CrossRef]

- Swift, C.L.; Louie, K.B.; Bowen, B.P.; Olson, H.M.; Purvine, S.O.; Salamov, A.; Mondo, S.J.; Solomon, K.V.; Wright, A.T.; Northen, T.R.; et al. 2021. Anaerobic gut fungi are an untapped reservoir of natural products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 118, e2019855118. [CrossRef]

- Maghembe, R.; Damian, D.; Makaranga, A.; Nyandoro, S.S.; Lyantagaye, S.L.; Kusari, S.; Hatti-Kaul, R. 2020. Omics for Bioprospecting and Drug Discovery from Bacteria and Microalgae. Antibiot, 9, 229. [CrossRef]

- Moir, D.T.; Shaw, K.J.; Hare, R.S.; Vovis, G.F. 1999. Genomics and Antimicrobial Drug Discovery. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., 43, 439. [CrossRef]

- Schnappinger, D. 2015. Genetic Approaches to Facilitate Antibacterial Drug Development. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med., 5, a021139. [CrossRef]

- Tortorella, E.; Tedesco, P.; Espositom, F.P.; January, G.G.; Fani, R.; Jaspars, M.; de Pascale, D. 2018. Antibiotics from Deep-Sea Microorganisms: Current Discoveries and Perspectives. Mar. Drugs, 16, 355. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Tiwari, S.P.; Rai, A.K.; Mohapatra, T.M. 2011. Cyanobacteria: An emerging source for drug discovery. J. Antibiot., 64, 401–412. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, V.; Rivas, L.; Cardenas, C.; Guzman, F. 2020. Cyanobacteria and Eukaryotic Microalgae as Emerging Sources of Antibacterial Peptides. Molecules, 25, 5804. [CrossRef]

- Alsenani, F.; Tupally, K.R.; Chua, E.T.; Eltanahy, E.; Alsufyani, H.; Parekh, H.S.; Schenk, P.M. 2020. Evaluation of microalgae and cyanobacteria as potential sources of antimicrobial compounds. Saudi. Pharm. J, 28, 1834–1841. [CrossRef]

- Santovito, E.; Greco, D.; Marquis, V.; Raspoet, R.; D’Ascanio, V.; Logrieco, A.F.; Avantaggiato, G. 2019. Antimicrobial Activity of Yeast Cell Wall Products Against Clostridium perfringens. Foodborne Pathog. Dis., 16, 638–647. [CrossRef]

- Hatoum, R.; Labrie, S.; Fliss, I. (2012) Antimicrobial and probiotic properties of yeasts: From fundamental to novel applications. Front. Microbiol., 3, 421. [CrossRef]

- Mitcheltree, M.J.; Pisipati, A.; Syroegin, E.A.; Silvestre, K.J.; Klepacki, D.; Mason, J.D.; Terwilliger, D.W.; Testolin, G.; Pote, A.R.; Wu, K.J.Y.; et al. 2021. A synthetic antibiotic class overcoming bacterial multidrug resistance. Nature, 599, 507–512. [CrossRef]

- Tenea, G.N.; Yépez, L. 2016. Bioactive Compounds of Lactic Acid Bacteria. Case Study: Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activity of Bacteriocin-producing Lactobacilli Isolated from Native Ecological Niches of Ecuador. Probiotics Prebiotics Hum. Nutr. Health, xxx, 149–167.

- Todorov, S.D.; Dicks, L.M.T. .2007. Bacteriocin production by Lactobacillus pentosus ST712BZ isolated from boza. Braz. J. Microbiol., 38, 166–172. [CrossRef]

- Oscáriz, J.C.; Pisabarro, A.G. 2001. Classification and mode of action of membrane-active bacteriocins produced by Gram-positive bacteria. Int. Microbiol., 4, 13–19. [CrossRef]

- Klaenhammer, T.R. 1993. Genetics of bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev., 12, 39–85. [CrossRef]

- Güllüce, M.; Karadayı, M.; Barı¸s, Ö. 2013. Bacteriocins: Promising natural antimicrobials. Local Environ., 3, 6.

- Cotter, P.D.; Hill, C.; Ross, R.P. 2005. Food microbiology: Bacteriocins: Developing innate immunity for food. Nat. Rev. Microbiol., 3, 777–788. [CrossRef]

- Drider, D.; Fimland, G.; Héchard, Y.; McMullen, L.M.; Prévost, H. 2006. The Continuing Story of Class IIa Bacteriocins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 70, 564–582. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-González, J.C.; Martínez-Tapia, A.; Lazcano-Hernández, G.; García-Pérez, B.E.; Castrejón-Jiménez, N.S. 2021. Bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria. A powerful alternative as antimicrobials, probiotics, and immunomodulators in veterinary medicine. Animals, 11, 979. [CrossRef]

- Parada, J.L.; Caron, C.R.; Medeiros, A.B.P.; Soccol, C.R. 2007. Bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria: Purification, properties and use as biopreservatives. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol., 50, 521–542. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R.; Dicks, L.M.T. 2005 Mode of action of lipid II-targeting lantibiotics. Int. J. Food Microbiol., 101, 201–216. [CrossRef]

- Paiva, A.D.; Breukink, E.; Mantovani, H.C. (2011) Role of lipid II and membrane thickness in the mechanism of action of the lantibiotic bovicin HC5. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., 55, 5284–5293. [CrossRef]

- Nissen-Meyer, J.; Oppegård, C.; Rogne, P.; Haugen, H.S.; Kristiansen, P.E. 2010. Structure and Mode-of-Action of the Two-Peptide (Class-IIb) Bacteriocins. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins, 2, 52–60. [CrossRef]

- Perez, R.H.; Zendo, T.; Sonomoto, K. 2018 Circular and Leaderless Bacteriocins: Biosynthesis, Mode of Action, Applications, and Prospects. Front Microbiol., 9, 2085. [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, R.S.; Pearson, L.; Kennedy, R.C. 2018. Mode of Action of a Lysostaphin-Like Bacteriolytic Agent Produced by Streptococcus zooepidemicus 4881. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 62, 4536–4541. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, H.; Zou, Y.; Li, P.; Sun, C.; Xu, W. 2018. Class III bacteriocin Helveticin-M causes sublethal damage on target cells through impairment of cell wall and membrane. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 45, 213–227. [CrossRef]

- Swe, P.M.; Cook, G.M.; Tagg, J.R.; Jack, R.W. 2009. Mode of Action of Dysgalacticin: A Large Heat-Labile Bacteriocin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother., 63, 679–686. [CrossRef]

- Meade, E.; Slattery, M.A.; Garvey, M. 2020. Bacteriocins, Potent Antimicrobial Peptides and the Fight against Multi Drug Resistant Species: Resistance Is Futile? Antibiotics, 9, 32. [CrossRef]

- Mclller, E.; Radler, F. Caseicin. 1993. a Bacteriocin from Lactobacillus casei. Folia Microbiol., 38, 441–446. [CrossRef]

- Bollenbach, T. 2015. Antimicrobial interactions: Mechanisms and implications for drug discovery and resistance evolution. Curr. Opin. Microbiol., 27, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Herzog, M.; Tiso, T.; Blank, L.M.; Winter, R. 2020. Interaction of rhamnolipids with model biomembranes of varying complexity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr., 1862, 183431. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zu, Y.; Li, X.; Meng, Q.; Long, X. 2020. Recent progress towards industrial rhamnolipids fermentation: Process optimization and foam control. Bioresour. Technol., 298, 122394. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, P.; Saini, N.K.; Thakur, V.K.; Gupta, V.K.; Saini, R.V.; Saini, A.K. 2021. Rhamnolipid the Glycolipid Biosurfactant: Emerging trends and promising strategies in the field of biotechnology and biomedicine. Microb. Cell Factories, 20, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Christova, N.; Tuleva, B.; Kril, A.; Georgieva, M.; Konstantinov, S.; Terziyski, I.; Nikolova, B.; Stoineva, I. 2013. Chemical Structure and In Vitro Antitumor Activity of Rhamnolipids from Pseudomonas aeruginosa BN10. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol., 170, 676–689. [CrossRef]

- Borah, S.N.; Goswami, D.; Sarma, H.K.; Cameotra, S.S.; Deka, S. 2016. Rhamnolipid biosurfactant against Fusarium verticillioides to control stalk and ear rot disease of maize. Front. Microbiol., 7, 1505. [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Black, W.; Sawyer, T. 2021. Application of Environment-Friendly Rhamnolipids against Transmission of Enveloped Viruses Like SARS-CoV2. Viruses, 13, 322. [CrossRef]

- Remichkova, M.; Galabova, D.; Roeva, I.; Karpenko, E.; Shulga, A.; Galabov, A.S. 2008. Anti-herpesvirus activities of Pseudomonas sp. S-17 rhamnolipid and its complex with alginate. Zeitschrift Fur Naturforsch Sect. C J. Biosci., 63, 75–81. [CrossRef]

- Giugliano, R.; Buonocore, C.; Zannella, C.; Chianese, A.; Esposito, F.P.; Tedesco, P.; De Filippis, A.; Galdiero, M.; Franci, G.; de Pascale, D. 2021. Antiviral Activity of the Rhamnolipids Mixture from the Antarctic Bacterium Pseudomonas gessardii M15 against Herpes Simplex Viruses and Coronaviruses. Pharmaceutics, 13, 2121. [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, J.R.; Chou, Y.C.; Gillies, K.; Kondo, J.K. 1989. Nisin Inhibits Several Gram-Positive, Mastitis-Causing Pathogens. J. Dairy Sci., 72, 3342–3345. [CrossRef]

- Lebel, G.; Piché, F.; Frenette, M.; Gottschalk, M.; Grenier, D. 2013. Antimicrobial activity of nisin against the swine pathogen Streptococcus suis and its synergistic interaction with antibiotics. Peptides, 50, 19–23. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J.; Draper, L.A.; O'Connor, P.M.; Coffey, A.; Hill, C.; Ross, R.P.; Cotter, P.D.; O'Mahony, J. 2010. Comparison of the activities of the lantibiotics nisin and lacticin 3147 against clinically significant mycobacteria. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents, 36, 132–136. [CrossRef]

- Campion, A.; Casey, P.G.; Field, D.; Cotter, P.D.; Hill, C.; Ross, R.P. 2013. In vivo activity of Nisin A and Nisin v against Listeria monocytogenes in mice. BMC Microbiol., 13, 23. [CrossRef]

- Grilli, E.; Messina, M.; Catelli, E.; Morlacchini, M.; Piva, A. 2009. Pediocin a improves growth performance of broilers challenged with Clostridium perfringens. Poult. Sci., 88, 2152–2158. [CrossRef]

- Lauková, A.; Styková, E.; Kubašová, I.; Gancarˇcíková, S.; Plachá, I.; Mudro ˇnová, D.; Kandriˇcáková, A.; Miltko, R.; Belzecki, G.; Valocký, I. 2018. Enterocin M and its Beneficial Effects in Horses—A Pilot Experiment. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins, 10, 420–426. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Cui, Y.; Wang, W.; Xu, J.; Xu, L. 2012. Production of two bacteriocins in various growth conditions produced by gram-positive bacteria isolated from chicken cecum. Can. J. Microbiol., 58, 93–101. [CrossRef]

- Line, J.E.; Svetoch, E.A.; Eruslanov, B.V.; Perelygin, V.V.; Mitsevich, V.; Mitsevich, I.P.; Levchuk, V.P.; Svetoch, O.E.; Seal, B.S.; Siragusa, G.R.; et al. 2008. Isolation and Purification of Enterocin E-760 with Broad Antimicrobial Activity against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., 52, 1094–1100. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.P.; Flynn, J.; Hill, C.; Ross, R.P.; Meaney, W.J. 1999. The natural food grade inhibitor, lacticin 3147, reduced the incidence of mastitis after experimental challenge with Streptococcus dysgalactiae in nonlactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci., 82, 2625–2631. [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, R.; Todorov, S.D.; Dicks, L.M.T. 2010. Mode of action and in vitro susceptibility of mastitis pathogens to macedocin ST91KM and preparation of a teat seal containing the bacteriocin. Braz. J. Microbiol., 41, 133–145. [CrossRef]

- Tomita, K.; Nishio, M.; Saitoh, K.; Yamamoto, H.; Hoshino, Y.; Ohkuma, H.; Konishi, M.; Miyaki, T.; Oki, T. 1990. Pradimicins A, B and C: New antifungal antibiotics. I. Taxonomy, production, isolation and physico-chemical properties. J. Antibiot, 43, 755–762. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, T.J.; Giri, N. 1997. Pradimicins: A novel class of broad-spectrum antifungal compounds. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis., 16, 93–97. [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.R. 1999. Bacterial inhibition of fungal growth and pathogenicity. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis., 11, 129–142. [CrossRef]

- Boumehira, A.Z.; El-Enshasy, H.A.; Hacene, H.; Elsayed, E.A.; Aziz, R.; Park, E.Y. 2016. Recent progress on the development of antibiotics from the genus Micromonospora. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng., 21, 199–223. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, R.E.; Giacobbe, R.A.; Monaghan, R.L. 1989. L-671,329, a new antifungal agent. I. Fermentation and isolation. J. Antibiotic, 42, 163–167. [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, N.; Kondo, Y.; Koyama, M.; Omoto, S.; Iwata, M.; Tsuruoka, T.; Inouye, S. 1983. Studies on a new nucleotide antibiotic, Dapiramicin. J. Antibiot., 37, 1–5.

- Dunlap, C.A.; Bowman, M.J.; Rooney, A.P. 2019. Iturinic lipopeptide diversity in the bacillus subtilis species group-important antifungals for plant disease biocontrol applications. Front. Microbiol., 10, 1794. [CrossRef]

- Lebbadi, M.; Gálvez, A.; Maqueda, M.; Martínez-Bueno, M.; Valdivia, E. Fungicin M4: 1994. A narrow spectrum peptide antibiotic from Bacillus licheniformis M-4. J. Appl. Bacteriol., 77, 49–53. [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, A.; Maqueda, M.; Martínez-Bueno, M.; Lebbadi, M.; Valdivia, E. 1993. Isolation and physico-chemical characterization of an antifungal and antibacterial peptide produced by Bacillus licheniformis A12. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 39, 438–442. [CrossRef]

- Chernin, L.; Brandis, A.; Ismailov, Z.; Chet, I. 1996. Pyrrolnitrin production by an Enterobacter agglomerans strain with a broad spectrum of antagonistic activity towards fungal and bacterial phytopathogens. Curr. Microbiol., 32, 208–212. [CrossRef]

- Greiner, M.; Winkelmann, G. 1991. Fermentation and isolation of herbicolin A, a peptide antibiotic produced by Erwinia herbicola strain A 111. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 34, 565–569. [CrossRef]

- Winkelmann, G.; Lupp, R.; Jung, G. 1980. Herbicolins—New peptide antibiotics from erwinia herbicola. J. Antibiot., 33, 353–358. [CrossRef]

- Shoji, J.; Hinoo, H.; Sakazaki, R.; Kato, T.; Hattori, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Tawara, K.; Kikuchi, J.; Terui, Y. 1989. Isolation of CB-25-I, an antifungal antibiotic, from serratia plymuthica. J. Antibiot., 42, 869–874. [CrossRef]

- Serino, L.; Reimmann, C.; Visca, P.; Beyeler, M.; Chiesa, V.D.; Haas, D. 1997. Biosynthesis of pyochelin and dihydroaeruginoic acid requires the iron-regulated pchDCBA operon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol., 179, 248–257. [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.R.; Taylor, G.W.; Rutman, A.; Høiby, N.; Cole, P.J.; Wilson, R. 1999. Pseudomonas aeruginosa pyocyanin and 1-hydroxyphenazine inhibit fungal growth. J. Clin. Pathol., 52, 385–387. [CrossRef]

- Vincent, M.N.; Harrison, L.A.; Brackin, J.M.; Kovacevich, P.A.; Mukerji, P.; Weller, D.M.; Pierson, E.A. 1991. Genetic analysis of the antifungal activity of a soilborne Pseudomonas aureofaciens strain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 57, 2928–2934. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, L.; Teplow, D.B.; Rinaldi, M.; Strobel, G. Pseudomycins. 1991. a family of novel peptides from Pseudomonas syringae possessing broad-spectrum antifungal activity. J. Gen. Microbiol., 137, 2857–2865. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Park, H.J.; Ishizuka, S.; Omata, K.; Hirama, M. 1995. Chemistry and Antimicrobial Activity of Caryoynencins Analogs. J. Med. Chem., 38, 5015–5022. [CrossRef]

- Barker, W.R.; Callaghan, C.; Hill, L.; Noble, D.; Acred, P.; Harper, P.B.; Sowa, M.A.; Fletton, R.A. G1549. 1979. A new cyclic hydroxamic acid antibiotic, isolated from culture broth of pseudomonas alcaligenes. J. Antibiot., 32, 1096–1103. [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.; Suh, J.W.; Kim, S.; Hyun, B.; Kim, C.; Lee, C. 1994. hoon Cepacidine A, A novel antifungal antibiotic produced by pseudomonas cepacia. II. Physico-chemical properties and structure elucidation. J. Antibiot., 47, 1406–1416. [CrossRef]

- Abe, M.; Nakazawa, T. 1994. Characterization of Hemolytic and Antifungal Substance, Cepalycin, from Pseudomonas cepacia.Microbiol. Immunol, 38, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Bisacchi, G.S.; Parker, W.L.; Hockstein, D.R.; Koster, W.H.; Rathnum, M.L.; Unger, S.E. 1987. Xylocandin: A new complex of antifungal peptides. II. Structural studies and chemical modifications. J. Antibiot., 40, 1520–1529. [CrossRef]

- Saalim, M.; Villegas-Moreno, J.; Clark, B.R. 2020. Bacterial Alkyl-4-quinolones: Discovery, Structural Diversity and Biological Properties. Molecules, 25, 5689. [CrossRef]

- Knappe, T.A.; Linne, U.; Zirah, S.; Rebuffat, S.; Xie, X.; Marahiel, M.A. 2008. Isolation and structural characterization of capistruin, a lasso peptide predicted from the genome sequence of Burkholderia thailandensis E264. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 130, 11446–11454. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Izaki, K.; Takahashi, H. 1982. New polyenic antibiotics active against gram-positive and -negative bacteria: I. Isolation and purification of antibiotics produced by gl uconobacter sp. W-315. J. Antibiot., 35, 1141–1147. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Deshmukh, S.K.; Reddy, M.S.; Prasad, R.; Goel, M. 2020. Endolichenic fungi: A hidden source of bioactive metabolites. S. Afr. J. Bot., 134, 163–186. [CrossRef]

- Pelaez, F.; Cabello, A.; Platas, G.; Díez, M.T.; Del Val, A.G.; Basilio, A.; Martán, I.; Vicente, F.; Bills, G.F.; Giacobbe, R.A.; et al. 2000. The discovery of enfumafungin, a novel antifungal compound produced by an endophytic Hormonema species biological activity and taxonomy of the producing organisms. Syst. Appl. Microbiol., 23, 333–343. [CrossRef]

- Kuhnert, E.; Li, Y.; Lan, N.; Yue, Q.; Chen, L.; Cox, R.J.; An, Z.; Yokoyama, K.; Bills, G.F. 2018. Enfumafungin synthase represents a novel lineage of fungal triterpene cyclases. Environ. Microbiol., 20, 3325–3342. [CrossRef]

- Sauter, H.; Steglich, W.; Anke, T. 1999. Strobilurins: Evolution of a new class of active substances. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed., 38, 1328–1349.

- Chepkirui, C.; Richter, C.; Matasyoh, J.C.; Stadler, M. 2016. Monochlorinated calocerins A–D and 9-oxostrobilurin derivatives from the basidiomycete Favolaschia calocera. Phytochemistry, 132, 95–101. [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Xu, J.; Rapior, S.; Jeewon, R.; Lumyong, S.; Niego, A.G.T.; Abeywickrama, P.D.; Aluthmuhandiram, J.V.S.; Brahamanage, R.S.; Brooks, S.; et al. 2019. The amazing potential of fungi: 50 ways we can exploit fungi industrially. Fungal Divers., 97, 1–136. [CrossRef]

- Chepkirui, C.; Cheng, T.; Matasyoh, J.; Decock, C.; Stadler, M. 2018. An unprecedented spiro [furan-2,1’-indene]-3-one derivative and other nematicidal and antimicrobial metabolites from Sanghuangporus sp. (Hymenochaetaceae, Basidiomycota) collected in Kenya. Phytochem. Lett., 25, 141–146. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Chen, Z.; Liu, P.; Wang, Y.; Xin, Z.; Zhu, W. 2014. New rubrolides from the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus terreus OUCMDZ-1925. J. Antibiot., 67, 315–318. [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Zhang, XS.; Du, L.; Wang, W.; Zhu, T.; Gu, Q.; Li, D. 2014. Sorbicatechols A and B, antiviral sorbicillinoids from the marinederived fungus Penicillium chrysogenum PJX-17. J. Nat. Prod., 77, 424–428. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Hao, X.; Li, S.; Jia, J.; Guan, Y.; Peng, Z.; Bi, H.; Xiao, C.; Cen, S.; et al. 2019. Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Natural Products from the Marine-Derived Penicillium sp. IMB17-046. Molecules, 24, 2821. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Fang, W.; Tan, S.; Lin, X.; Xun, T.; Yang, B.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y. 2016. Aspernigrins with anti-HIV-1 activities from the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus niger SCSIO Jcsw6F30. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett., 26, 361–365. [CrossRef]

- Raveh, A.; Delekta, P.C.; Dobry, C.J.; Peng, W.; Schultz, P.J.; Blakely, P.K.; Tai, A.W.; Matainaho, T.; Irani, D.N.; Sherman, D.H.; et al. 2013. Discovery of potent broad spectrum antivirals derived from marine actinobacteria. PLoS ONE, 8, e82318. [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Sun, X.; Yu, G.; Wang, W.; Zhu, T.; Gu, Q.; Li, D. 2014. Cladosins A–E, hybrid polyketides from a deep-sea-derived fungus, Cladosporium sphaerospermum. J. Nat. Prod., 77, 270–275. [CrossRef]

- Banks, P. 2009. The Microplate Market Past, Present and Future [Online]. Drug Discovery World. Available online: https://www.ddw-online.com/themicroplate-market-past-present-and-future-1127-200904/ (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Ingham, C.J.; Sprenkels, A.; Bomer, J.; Molenaar, D.; Van Den Berg, A.; Van Hylckama Vlieg, J.E.; et al. 2007. The micro-Petri dish, a million-well growth chip for the culture and high-throughput screening of microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 18217–18222. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.-Y.; Dong, L.; Zhao, J.-K.; Hu, X.; Shen, C.; Qiao, Y.; et al. 2016. Highthroughput single-cell cultivation on microfluidic streak plates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82:2210. [CrossRef]

- Aleklett, K.; Kiers, E.T.; Ohlsson, P.; Shimizu, T.S.; Caldas, V.E.A.; Hammer, E.C. 2018. Build your own soil: exploring microfluidics to create microbial habitat structures. ISME J. 12, 312–319. [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Girguis, P.R.; Buie, C.R. 2016. Nanoporous microscale microbial incubators. Lab Chip 16, 480–488. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, A.; Leung, K.P.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L.; Ramasubramanian, A.K. 2013. High-throughput nano-biofilm microarray for antifungal drug discovery. mBio 4:e00331-00313. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dou, X.; Song, J.; Lyu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Xu, L.; Li, W.; Shan, A. 2019. Antimicrobial peptides: Promising alternatives in the post feeding antibiotic era. Med. Res. Rev., 39, 831–859. [CrossRef]

- Narayana, J.L.; Chen, J.Y. 2015. Antimicrobial peptides: Possible anti-infective agents. Peptides, 72, 88–94. [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Dong, F.; Shi, C.; Liu, S.; Sun, J.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Xu, H.; Lao, X.; Zheng, H. DRAMP 2.0. 2019. an updated data repository of antimicrobial peptides. Sci. Data, 6, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- da Cunha, N.B.; Cobacho, N.B.; Viana, J.F.C.; Lima, L.A.; Sampaio, K.B.O.; Dohms, S.S.M.; Ferreira, A.C.R.; de la Fuente-Núñez, C.; Costa, F.F.; Franco, O.L.; et al. 2017. The next generation of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) as molecular therapeutic tools for the treatment of diseases with social and economic impacts. Drug Discov. Today, 22, 234–248. [CrossRef]

- Huerta-Cantillo, J.; Navarro-García, F. 2016. Properties and design of antimicrobial peptides as potential tools againstpathogens and malignant cells. Investig. En Discapac., 5, 96–115.

- Li, C.; Zhu, C.; Ren, B.; Yin, X.; Shim, S.H.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, P.; Liu, C.; Yu, R.; et al. 2019. Two optimized antimicrobial peptides with therapeutic potential for clinical antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Eur. J. Med. Chem., 183, 111686. [CrossRef]

- Huan, Y.; Kong, Q.; Mou, H.; Yi, H. 2020. Antimicrobial Peptides: Classification, Design, Application and Research Progress in Multiple Fields. Front. Microbiol., 11, 582–779. [CrossRef]

- Carriel-Gomes, M.C.; Kratz, J.M.; Barracco, M.A.; Bachére, E.; Barardi, C.R.M.; Simões, C.M.O. 2007. In vitro antiviral activity of antimicrobial peptides against herpes simplex virus 1, adenovirus, and rotavirus. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz, 102, 469–472. [CrossRef]

- Kobori, T.; Iwamoto, S.; Takeyasu, K.; Ohtani, T. 2007. Biopolymers Volume 85/Number 4295. Biopolymers, 85, 392–406.

- Xia, S.; Liu, M.; Wang, C.; Xu, W.; Lan, Q.; Feng, S.; Qi, F.; Bao, L.; Du, L.; Liu, S.; et al. 2020. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 (previously 2019-nCoV) infection by a highly potent pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting its spike protein that harbors a high capacity to mediate membrane fusion. Cell Res., 30, 343–355. [CrossRef]

- Yasin, B.; Pang, M.; Turner, J.S.; Cho, Y.; Dinh, N.N.; Waring, A.J.; Lehrer, R.I.; Wagar, E.A. 2000. Evaluation of the inactivation of infectious herpes simplex virus by host-defense peptides. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis., 19, 187–194. [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, D.A.; Boyd, P.W. 2016. Marine phytoplankton and the changing ocean iron cycle. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 1072–1079. [CrossRef]

- Behrenfeld, M. J. 2014. Climate-mediated dance of the plankton. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 880–887. [CrossRef]

- De Baar, H. J. W.; et al. 1995. Importance of iron for plankton blooms and carbon dioxide drawdown in the Southern Ocean. Nature 373, 412–415. [CrossRef]

- Boyd, P. W.; et al. 2007. Mesoscale iron enrichment experiments 1993-2005: synthesis and future directions. Science 315, 612–617. [CrossRef]

- Behrenfeld, M. J.; et al. 2016. Revaluating ocean warming impacts on global phytoplankton. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 323–330. [CrossRef]

- Behrenfeld, M. J.; et al. 2017. Annual boom-bust cycles of polar phytoplankton biomass revealed by space-based lidar. Nat. Geosci. 10, 118–122. [CrossRef]

- Pachiadaki, M. G.; et al. 2017. Major role of nitrite-oxidizing bacteria in dark ocean carbon fixation. Science 358, 1046–105. [CrossRef]

- Grzymski, J. J.; et al. 2012. A metagenomic assessment of winter and summer bacterioplankton from Antarctic Peninsula coastal surface waters. ISME J. 6, 1901–1915. [CrossRef]

- Field, C.B.; Behrenfeld, M.J.; Randerson, J.T.; Falkowski, P. 1998. Primary production of the biosphere: integrating terrestrial and oceanic components. Science 281, 237–240. [CrossRef]

- Behrenfeld, M. J.; et al. 2001. Biospheric primary production during an ENSO transition. Science 291, 2594–2597. [CrossRef]

- Boetius, A.; et al. 2013. Massive export of algal biomass from the melting Arctic sea ice. Science 339, 1430. [CrossRef]

- Danovaro, R.; et al. 2011. Marine viruses and global climate change. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35, 993–1034. [CrossRef]

- Brum, J. R.; et al. 2015. Patterns and ecological drivers of ocean viral communities. Science 348, 1261498. [CrossRef]

- Hanson, C.A.; Fuhrman, J.A.; Horner-Devine, M.C.; Martiny, J.B.H. 2012. Beyond biogeographic patterns: processes shaping the microbial landscape. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 497–506. [CrossRef]

- Zinger, L.; Boetius, A.; Ramette, A. 2014. Bacterial taxa-area and distance-decay relationships in marine environments. Mol. Ecol. 23, 954–964. [CrossRef]

- Archer, S. D. J.; et al. 2019. Airborne microbial transport limitation to isolated Antarctic soil habitats. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 925–932. [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, D.; van Sebille, E.; Rintoul, S.R.; Lauro, F.M.; Cavicchioli, R. 2013. Advection shapes Southern Ocean microbial assemblages independent of distance and environment effects. Nat. Commun. 4, 2457. [CrossRef]

- Cavicchioli, R. 2015. Microbial ecology of Antarctic aquatic systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 691–706. [CrossRef]

- Riebesell, U.; Gattuso, J.-P. 2015. Lessons learned from ocean acidification research. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 12–14. [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, D.A.; Fu, F.X. 2017. Microorganisms and ocean global change. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 17508. [CrossRef]

- Bunse, C.; et al. 2016. Response of marine bacterioplankton pH homeostasis gene expression to elevated CO2. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 483–491. [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.K.; Bardgett, R.D.; Smith, P.; Reay, D.S. 2010. Microorganisms and climate change: terrestrial feedbacks and mitigation options. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 779–790. [CrossRef]

- Bardgett, R.D.; van der Putten, W.H. 2014. Belowground biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Nature 515, 505–511. [CrossRef]

- Fellbaum, C.R.; Mensah, J.A.; Pfeffer, P.E.; Kiers, E.T.; Bücking, H. 2012. The role of carbon in fungal nutrient uptake and transport Implications for resource exchange in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Plant Signal. Behav. 7, 1509–1512. [CrossRef]

- Bonan, G. B. 2012. Forests and climate change: forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests. Science 320, 1444–1449. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; et al. 2011. A large and persistent carbon sink in the world's forests. Science 333, 988–993. [CrossRef]

- Hovenden, M. J.; et al. 2019. Globally consistent influences of seasonal precipitation limit grassland biomass response to elevated CO2. Nat. Plants 5, 167–173. [CrossRef]

- Evans, R. D.; et al. 2014. Greater ecosystem carbon in the Mojave Desert after ten years exposure to elevated CO2. Nat. change.4, 394–397. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, T. A.; et al. 2018. Synergy between nutrients and warming enhances methane ebullition from experimental lakes. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 156–160. [CrossRef]

- van Bergen, T. J. H. M.; et al. Seasonal and diel variation in greenhouse gas emissions from an urban pond and its major drivers. Limnol. Oceanogr. [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; et al. 2015. The links between ecosystem multifunctionality and above- and belowground biodiversity are mediated by climate. Nat. Commun. 6, 8159. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; et al. 2016. Microbial diversity drives multifunctionality in terrestrial ecosystems. Nat. Commun. 7, 10541. [CrossRef]

- Walker, T. W. N.; et al. 2018. Microbial temperature sensitivity and biomass change explain soil carbon loss with warming. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 885–889. [CrossRef]

- Altizer, S.; Ostfeld, R.S.; Johnson, P.T.; Kutz, S.; Harvell, C.D. 2013. Climate change and infectious diseases: from evidence to a predictive framework. Science 341, 514–519. [CrossRef]

- Harvell, C. D.; et al. 2002. Climate warming and disease risks for terrestrial and marine biota. Science 296, 2158–2162. [CrossRef]

- Bourne, D.G.; Morrow, K.M.; Webster, N.S. 2016. Insights into the coral microbiome: Underpinning the health and resilience of reef ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 70, 317–340. [CrossRef]

- Frommel, A. Y.; et al. 2012A. Severe tissue damage in Atlantic cod larvae under increasing ocean acidification. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 42–46. [CrossRef]

- Anderegg, W.R.L.; Kane, J.M.; Anderegg, L.D.L. 2013. Consequences of widespread tree mortality triggered by drought and temperature stress. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 30–36. [CrossRef]

- Raffel, T. R.; et al. 2013. Disease and thermal acclimation in a more variable and unpredictable climate. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 146–151. [CrossRef]

- Pounds, J. A.; et al. 2006. Widespread amphibian extinctions from epidemic disease driven by global warming. Nature 439, 161–167. [CrossRef]

- MacFadden, D.R.; McGough, S.F.; Fisman, D.; Santillana, M.; Brownstein, J.S. 2018. Antibiotic resistance increases with local temperature. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 510–514. [CrossRef]

- Bouma, M.J.; Dye, C. 1997. Cycles of malaria associated with El Niño in Venezuela. JAMA 278, 1772–1774. [CrossRef]

- Baylis, M.; Mellor, P.S.; Meiswinkel, R. 1999. Horse sickness and ENSO in South Africa. Nature 397, 574. [CrossRef]

- Rohani, P. 2009. The link between dengue incidence and El Nino Southern Oscillation. PLOS Med. 6, e1000185. [CrossRef]

- Kreppel, K. S.; et al. 2014. A non-stationary relationship between global climate phenomena and human plague incidence in Madagascar. PLOS Neglect. Trop. Dis. 8, e3155. [CrossRef]

- Caminade, C.; et al. 2017. Global risk model for vector-borne transmission of Zika virus reveals the role of El Niño 2015. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 119–124. [CrossRef]

- DiMasi, J.A.; Grabowski, H.G.; Hansen, R.W. 2016. Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: New estimates of R&D costs. J. Health Econ., 47, 20–33. [CrossRef]

- Trussell, P.C.; Baird, E.A. 1947. A rapid method for the assay of penicillin. Can. J. Res., 25, 5–8. [CrossRef]

- Rex, J.; Ghannoum, M.A.; Alexander, D.B.; Andes, D.; Brown, D.A.; Diekema, D.J.; Espinel-Ingroff, A.; Fowler, C.L.; Johnson, E.J.; Knapp, C.C.; et al. 2010. Method for Antifungal Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Testing of Nondermatophyte Filamentous Fungi; Approved Guideline; CLSI Document M51-A; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA,; Volume 30, pp. 1–29.

- Balouiri, M.; Sadiki, M.; Ibnsouda, S.K. 2016. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J. Pharm. Anal., 6, 71–79. [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, M.P.; Patel, J.B.; Bobenchik, A.M.; Campeau, S.; Cullen, S.K.; Gallas, M.F.; Gold, H.; Humphries, R.M.; Kirn, T.J.; Lewis, J.S.; et al. 2019. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk Susceptibility Tests: Approved Standard, 29th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Supplement M100; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA,; Volume 32.

- White, R.L.; Burgess, D.S.; Manduru, M.; Bosso, J.A. 1996 Comparison of three different in vitro methods of detecting synergy: Time-kill, checkerboard, and E test. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., 40, 1914–1918. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Esquilín, A.E.; Roane, T.M. 2005. Antifungal activities of actinomycete strains associated with high-altitude sagebrush rhizosphere. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 32, 378–381. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.N.; Nambisan, B.; Sundaresan, A.; Mohandas, C.; Anto, R.J. 2014. Isolation and identification of antimicrobial secondary metabolites from Bacillus cereus associated with a rhabditid entomopathogenic nematode. Ann. Microbiol., 64, 209–218. [CrossRef]

- Menon, T.; Umamaheswari, K.; Kumarasamy, N.; Solomon, S.; Thyagarajan, S.P. 2001. Efficacy of fluconazole and itraconazole in the treatment of oral candidiasis in HIV patients. Acta Trop., 80, 151–154. [CrossRef]

- Imhof, A.; Balajee, S.A.; Marr, K.A. 2003. New Methods To Assess Susceptibilities of Aspergillus Isolates to Caspofungin. J. Clin. Microbiol., 41, 5683–5688. [CrossRef]

- Pfaller, M.A.; Sheehan, D.J.; Rex, J.H. 2004. Determination of Fungicidal Activities against Yeasts and Molds: Lessons Learned from Bactericidal Testing and the Need for Standardization. Clin. Microbiol. Rev., 17, 268–280. [CrossRef]

- Crouch, S.P.M.; Kozlowski, R.; Slater, K.J.; Fletcher, J. 1993. Use of ATP as a measure of cell proliferation and cell toxicity. J. Immunol. Methods, 160, 81–88. [CrossRef]

- Paloque, L.; Vidal, N.; Casanova, M.; Dumètre, A.; Verhaeghe, P.; Parzy, D.; Azas, N. 2013. A new, rapid and sensitive bioluminescence assay for drug screening on Leishmania. J. Microbiol. Methods, 95, 320–323. [CrossRef]

- Finger, S.; Wiegand, C.; Buschmann, H.J.; Hipler, U.C. 2013. Antibacterial properties of cyclodextrin-antiseptics-complexes determined by microplate laser nephelometry and ATP bioluminescence assay. Int. J. Pharm., 452, 188–193. [CrossRef]

- Galiger, C.; Brock, M.; Jouvion, G.; Savers, A.; Parlato, M.; Ibrahim-Granet, O. 2013. Assessment of efficacy of antifungals against Aspergillus fumigatus: Value of real-time bioluminescence imaging. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., 57, 3046–3059. [CrossRef]

- Peyron, F.; Favel, A.; Guiraud-Dauriac, H.; El Mzibri, M.; Chastin, C.; Duménil, G.; Regli, P. 1997. Evaluation of a flow cytofluorometric method for rapid determination of amphotericin B susceptibility of yeast isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., 41, 1537–1540. [CrossRef]

- Paparella, A.; Taccogna, L.; Aguzzi, I.; Chaves-López, C.; Serio, A.; Marsilio, F.; Suzzi, G. 2008. Flow cytometric assessment of the antimicrobial activity of essential oils against Listeria monocytogenes. Food Control, 19, 1174–1182. [CrossRef]

- Landaburu, L.U.; Berenstein, A.J.; Videla, S.; Maru, P.; Shanmugam, D.; Chernomoretz, A.; Agüero, F. TDR Targets 6. 2020. Driving drug discovery for human pathogens through intensive chemogenomic data integration. Nucleic Acids Res., 48, D992. [CrossRef]

- Wondraczek, L.; Pohnert, G.; Schacher, F.H.; Köhler, A.; Gottschaldt, M.; Schubert, U.S.; et al. 2019. Artificial microbial arenas: materials for observing and manipulating microbial consortia. Adv. Mater. 31:1900284. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, E. J. 2012. Growing unculturable bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 194, 4151–4160. [CrossRef]

- Kaeberlein, T.; Lewis, K.; Epstein, S.S. 2002. Isolating "uncultivable" microorganisms in pure culture in a simulated natural environment. Science 296, 1127–1129. [CrossRef]

- Bollmann, A.; Lewis, K.; Epstein, S.S. 2007. Incubation of environmental samples in a diffusion chamber increases the diversity of recovered isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 6386–6390. [CrossRef]

- Berdy, B.; Spoering, A.L.; Ling, L.L.; Epstein, S.S. 2017. In situ cultivation of previously uncultivable microorganisms using the ichip. Nat. Protoc. 12, 2232–2242. [CrossRef]

- Sizova, M. V.; Hohmann, T.; Hazen, A.; Paster, B.J.; Halem, S.R.; Murphy, C.M.; et al. 2012. New approaches for isolation of previously uncultivated oral bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 194–203. [CrossRef]

- Nichols, D.; Cahoon, N.; Trakhtenberg, E.M.; Pham, L.; Mehta, A.; Belanger, A.; et al. 2010. Use of Ichip for high-throughput in situ cultivation of "uncultivable" microbial species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 2445–2450. [CrossRef]

- Sherpa, R.T.; Reese, C.J.; Montazeri Aliabadi, H. 2015. Application of iChip to grow "Uncultivable" microorganisms and its impact on antibiotic discovery. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 18, 303–315. [CrossRef]

- Lodhi, A.F.; Zhang, Y.; Adil, M.; Deng, Y. 2018. Antibiotic discovery: combining isolation chip (iChip) technology and co-culture technique. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102, 7333–7341. [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.L.; Schneider, T.; Peoples, A.J.; Spoering, A.L.; Engels, I.; Conlon, B.P.; et al. 2015. A new antibiotic kills pathogens without detectable resistance. Nature 517, 455–459. [CrossRef]

- Beneyton, T.; Wijaya, I.P.M.; Postros, P.; Najah, M.; Leblond, P.; Couvent, A.; et al. 2016. High-throughput screening of filamentous fungi using nanoliterrange droplet-based microfluidics. Sci. Rep. 6:27223. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.S.; Yang, C.H.; Lu, K.; Huang, K.S.; Zheng, Y.Z. 2011. Synthesis of agar microparticles using temperature-controlled microfluidic devices for Cordyceps militaris cultivation. Electrophoresis 32, 3157–3163. [CrossRef]

- Alkayyali, T.; Pope, E.; Wheatley, S.K.; Cartmell, C.; Haltli, B.; Kerr, R.G.; et al. 2021. Development of a microbe domestication pod (MD Pod) for in situ cultivation of micro-encapsulated marine bacteria. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 118, 1166–1176. [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Whitesides, G.M. 1998. Soft Lithography. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 37, 550–575.

- Weibel, D.B.; Diluzio, W.R.; Whitesides, G.M. 2007. Microfabrication meets microbiology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 209–218. [CrossRef]

- Zinchenko, A.; Devenish, S.R.A.; Kintses, B.; Colin, P.-Y.; Fischlechner, M.; Hollfelder, F. 2014. One in a million: flow cytometric sorting of single celllysate assays in monodisperse picolitre double emulsion droplets for directed evolution. Anal. Chem. 86, 2526–2533. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Volinsky, A.A.; Gallant, N.D. 2014. Crosslinking effect on polydimethylsiloxane elastic modulus measured by custom-built compression instrument. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 134:2014. [CrossRef]

- Nichols, D.; Lewis, K.; Orjala, J.; Mo, S.; Ortenberg, R.; Connor, P.; et al. 2008. Short peptide induces an "uncultivable" microorganism to grow in vitro. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 4889. [CrossRef]

- CDC (2020). Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States 2019. Atlanta, GA: CDC.

- Hu, B.; Xu, P.; Ma, L.; Chen, D.; Wang, J.; Dai, X.; et al. 2021. One cell at a time: droplet-based microbial cultivation, screening and sequencing. Mar. Life Sci. Technol. 3, 169–188. [CrossRef]

- Boedicker, J.Q.; Li, L.; Kline, T.R.; Ismagilov, R.F. 2008. Detecting bacteria and determining their susceptibility to antibiotics by stochastic confinement in nanoliter droplets using plug-based microfluidics. Lab Chip 8, 1265–1272. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhao, W. 2017. Emerging microtechnologies and automated systems for rapid bacterial identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing. Slas Technol. 22, 585–608. D. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.N.; Park, C.; Whitesides, G.M. 2003. Solvent compatibility of poly(dimethylsiloxane)-based microfluidic devices. Anal. Chem. 75, 6544–6554. [CrossRef]

| Microorganism | Molecular Class | Chemical Compound | Antimicrobial Activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomyces scopuliridis | Cyclic peptide | Desotamide B | S. aureus, S. aureus | (Tortorella et al.,2018) |

| Marinactinospora thermotolerans | Cyclic peptide | Marthiapeptide A | S. aureus, M. luteus, B. subtillis, B. thuringiensis | |

| Verrucosispora spp. | Spirotetronate polyketides | Abyssomicin C | Staphylococcus aureus that is resistant to both methicillin and vancomycin | |

| Streptomyces drozdowiczii | Cyclic peptide | Marfomycins A, B, E | M. luteus | |

| Streptomyces spp. | Spirotetronate polyketides | Lobophorin H | B. subtilis | |

| Streptomyces spp. | Spirotetronate polyketides | Lobophorin F | S. aureus, E. feacalis | |

| Streptomyces niveus | Sesquiterpene derivative | Marfuraquinocin A, D | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or simply S. aureus | |

| Streptomyces spp. | Alkaloid | Caboxamycin | S. epidermis, S. lentus, B. subtillis |

| Bacteriocin | Susceptible Microorganisms | Bacteriocin Producer | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nisin A | S. equinus, E. faecalis,. S. suis. S. epidermidis, S. aureus, S. dysgalactiae, S. uberis, S. agalactiae | Lactococcus lactic subsp. lactis | (Broadbent et al.,1989,Lebel et al.,2013,Carroll et al.,2010) |

| Nisin ANisin V | Listeria monocytogenes | L. lactis | (Campion et al.,2013) |

| Pediocin A | Clostridium perfringens | Pediococcus pentosaceus FBB61 | (Grili et al.,2009) |

| Enterocin M | Clostridium spp., Campylobacter spp. | Enterococcus faecium AL41 | (Laukova et al.,2018) |

| Enterocin CLE34 | Salmonella pullorum | Enterococcus faecium CLE34 | (Hernandez-Gonzalez et al.,2021),Wang et al.,2012) |

| Enterocin E-760 | Yersinia enterocolitica, E. coli, S. aureus, and Salmonella enterica serovars Enteritidis, Choleraesuis, Campylobacter jejuni; Typhimurium | Enterococcus faecium, Enterococcus durans, Enterococcus hirae | (Line et al.,2008) |

| Lacticin 3147 | S. agalactiae, S. dysgalactiae, S. aureus, S. uberis, paratuberculosis, Mycobacterium avium subsp. | Lactococcus lactis | (Carroll et al.,2010,Ryan et al.,1999) |

| Macedocin ST91KM | S. dysgalactiae, S. agalactiae, S. aureus, S. uberis | Streptococcus gallolyticus | (Pieterse et al.,2010) |

| Microorganism | Susceptible Organism(s) | Compound(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. hibisca | Aspergillus spp., Candida spp. | Pradimicins A, B, C | (Tomita et al.,1990) |

| Actinoplanes spp. | T. mentagrophytes | Purpuromycin | (kerr et al.,1999) |

| B. cereus | Aspergillus spp., Saccharomyces spp, and C. albicans | Azoxybacilin, Bacereutin, Cispentacin, and Mycocerein | (kerr et al.,1999) |

| M. neiheumicin | S. cerevisiae | Neihumicin | (Boumehira et al.,2016) |

| Micromonospora species | A. cladosporium, C. albicans, and Cryptococcus spp. | Spartanamycin B | (Boumehira et al.,2016) |

| Micromonospora species SCC 1792 | Dermatophytes and Candida spp. | Sch 37137 | (Schwartz et al.,1989) |

| Micromonospora species SF-1917 | R. solania | Dapiramicins A and B | (Nishizawa et al.,1983) |

| B. subtilis | Phytopathogens | Iturin A | (kerr et al.,1999,Dunlap et al.,2019) , |

| B. lichenformis | Mucor spp., Microsporum canis, Sporothrix spp. | Fungicin M-4 | (Lebbadi et al.,1994,Galvez et al.,1993) , |

| Microorganism | Antimicrobial Activity | Compounds | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hormonema spp. | Aspergillus spp., Candida spp. | Enfumafungin | (Pelaez at al.,2000) |

| F. calocera | Mucor plumbeus, Candida tenuis | Favolon | (Chepkirui et al.,2016) |

| C. comatus | P. aeruginosa | Coprinuslactone | (Hyde et al.,2019) |

| Sanghuangporus spp. | C. albicans, S. aureus | Microporenic acid A | (Chepkirui et al.,2018) |

| Aspergillus terreus | Influenza A virus | Rubrolide S | (Zhu et al.,2014) |

| Cladosporium sphaerospermum | Influenza A H1N1 | Cladosin C | (Wu et al.,2014) |

| Penicillium sp. | HCV, HIV | β-hydroxyergosta-8,14,24 (28)-trien-7-one, Trypilepyrazinol | (Li et al.,2019) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).