Submitted:

13 September 2024

Posted:

14 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

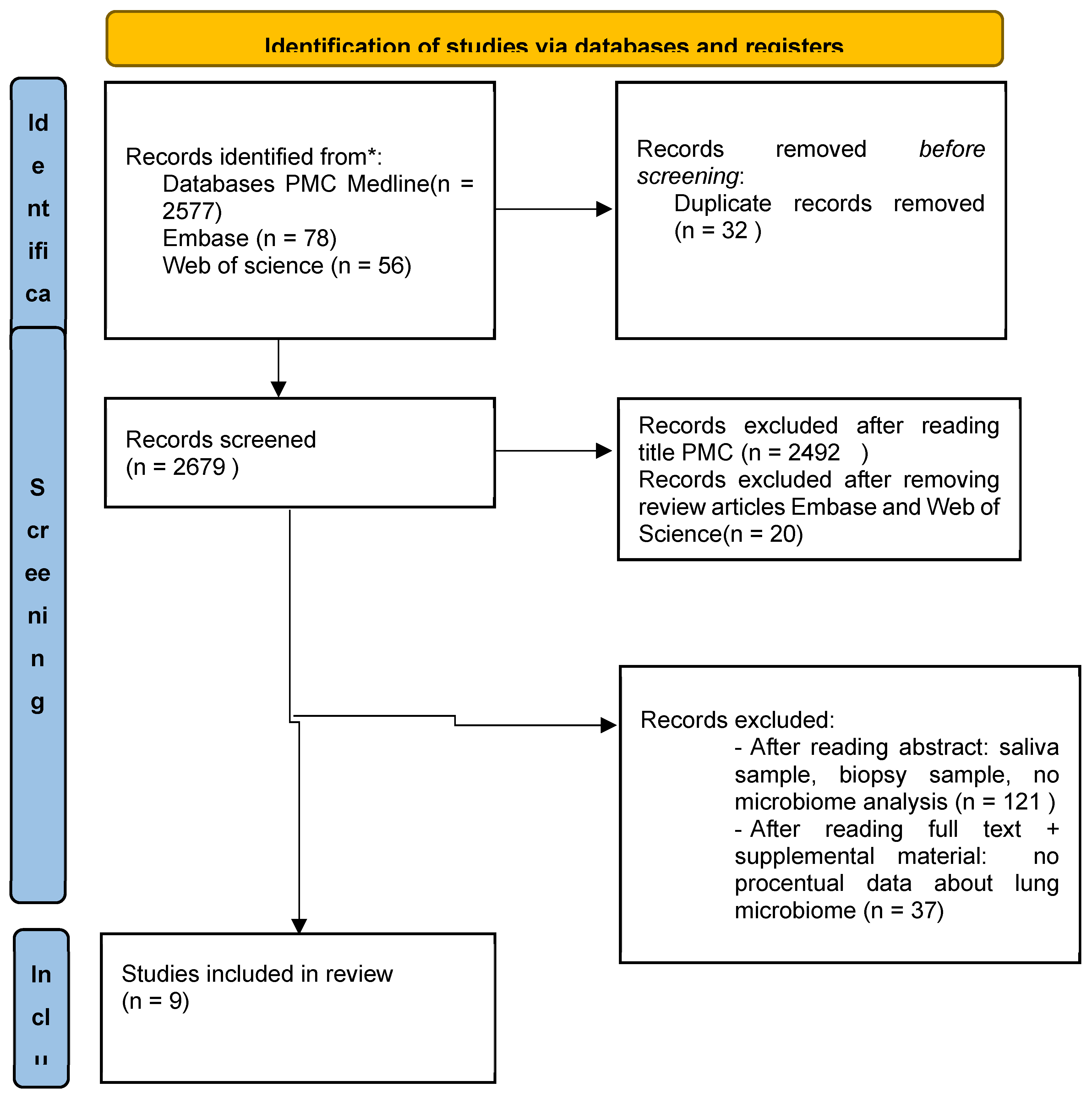

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection and Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Objectives

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

| Authors | Country | Inclusion Criteria | No* | What was compared | Sample | Metod of analysis | alpha diversity | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bingula R et al. (2020) | France | NSCLC eligible for surgical treatment; 18-80 yo; IMB < 29,9; no previous airway surgery or cancer treatment, no AB, Corticotherapy, Immunospressive drugs or pulmonary infections for at least the past 2 months | 15 | microbiota in saliva, BAL (obtained directly on excised lobe), non-malignant, peritumoural and tumour tissue |

the removed lung or lung lobe was placed in a sterile vessel and the tumour position was determined by palpation. First, a piece of non-malignant lung distal to the tumour (opposite side of the lobe) with an average size of 1 cm3 wa5s clamped 2 × 40 mL of sterile physiological saline into the bronchus; was retrieved (8–10 mL in total) |

Illumina MiSeq technology, performed 16S ribosomal rRNA targeted region V3-V4. |

Shannon diversity index and Faith’s phylogenetic Diversity No differences in alpha diversity metrics were detected between four lung samples |

At phylum level: Firmicutes 45.7%; Bacteriodes 13.3%; Actinobacteria 11.9%; Proteobacteria 28%; Fusobacteria 0.23%; Cyanobacteria 0.16%; Acidobacteria0.11%; Other 0.07% At genus level: Pseudomonas 10.3%; Blautia 5.9%; Streptococcus 5.1%; Capnocytophaga 4.8%; Acinetobacter 2.9%; Prevotella 2.3% Propionibacterium 2.3%; Lactobacillus 2.1%; Sphingomonas 1.8%; Bacteroides 1.5%; Veillonella 1.4%; Other each <1% |

| Wang K et al. (2019) |

China | primary bronchogenic carcinoma-confirmed; no glucocorticoid or antibiotic treatment for at least 30 days before sample collection; |

47 | the difference in microbiota diversity in the oral cavity and fluid bronchoalveolar lavage (BALF) of patients with lung cancer and healthy controls |

local anesthesia, flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy, subsegmental bronchus in the involved focal lobe 3x 50 mL of sterile normal saline were instilled, gently aspirated. Suction channel use was avoided until the tip of the bronscope extended beyond the carina; pooled and collected in a siliconized plastic bottle placed on ice | Illumina MiSeq technology, performed 16S ribosomal rRNA targeted region V4. QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit |

Shannon and Simpson indexes Lung cancer patients had less lung and oral microbiota diversity than healthy controls |

At phylum level: FIRMICUTES 38.42%; FUSOBACTERIA 5.12%; SPIROCHAETES 0.11%; TENERICUTES 0.11%; SYNERGISTETES 0.03%; |

| Jang, H.J. et al. (2021) |

South Korea | pathologically diagnosed with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | 84 | the differences in the lung microbiomes of patients with lung cancer. | rinsed mouth twice with sterile saline; topical anesthesia (lidocaine) using a nebulizer; sedated with midazolam and fentanyl; When the bronchoscope reached the “involved” airway containing the lung mass or the lung nodule, the bronchi were washed with 30–50 mL sterile saline (0.9%); approximately 15 mL BAL fluid was acquired for sequencing analysis; samples were immediately stored at -70 °C in a freezer, and DNA extraction was performed within 24 h | Illumina HiSeq technology, performed 16S ribosomal rRNA targeted region V3-V4. FastDNA® SPIN Kit for Soil CleanPCR kit |

Shannon and Simpson the difference was not significant (p = 0.307 for Shannon; p = 0.540 for Simpson index). |

At phylum level: PDL-1>10%: Bacteroidetes 39.4%; Firmicutes 30.5%; Proteobacteria19.1%; Fusobacteria 6.4%; Acinetobacter 3.2% PDL-1<10% Bacteroidetes 39.4%; Proteobacteria 28.2%; Firmicutes 23.2%; Fusobacteria 5.1%; Acinetobacter 2.8% At genus level: PDL-1>10%: Prevotella; Streptococcus; Veillonella; Haemophilus; Neisseria; Porphyromonas; Fusobacterium; Megasphaera; Leptotrichia; Rothia; Escheichia; PDL-1<10%: Prevotella; Neisseria; Haemophilus; Veillonella; Streptococcus; Porphyromonas; Fusobacterium; Megasphaera; Leptotrichia; Rothia; Pseudomonas; |

| Zhuo M et al. (2020) | China | lung cancer - no one with cancer treatment | 50 | association of the microbiota with lung cancer | Bronchoendoscope, which avoided contamination of the upper respiratory tract or oral microbiota, was performed to obtain paired BALF samples in lung cancer patients (one from the cancerous lung, the other from the contralateral non-cancerous lung). All samples were immediately frozen and maintained at -80C until further DNA extraction |

Illumina MiSeq technology, performed 16S ribosomal rRNA targeted region V3- V4 PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit |

Shannon diversity index and Simpson diversity index Cancer lung was not significantly different from normal lung in a-diversity |

At phylum level: Affected lung: Proteobacteria: 34.2%; Firmicutes: 27.96%; Bacteroides: 21.46%; Actinobacteria: 5.79%; Fusobacteria: 5.39%; Cyanobacteria: 1.23%; Spirochaerae: 1.12%; TM7 (Saccharibacteria): 0.53%; Acidobacteria: 0.53%; Tenericutes: 0.5%; Others: 1.2% Normal lung: Proteobacteria: 32.95%; Bacteroides: 26.65%; Firmicutes: 26.46%; Fusobacteria: 5.02%; Actinobacteria: 4.39%; Spirochaerae: 0.97%; TM7 (Saccharibacteria): 0.65%; Cyanobacteria: 0.56%; Acidobacteria: 0.55%; Tenericutes: 0.32%; Others: 1.43%. At genus level: Affected lung: Streptococcus: 10.78%; Neisseria: 7.54%; Alloprevotella: 5.22%; Prevotella_7: 4.88%; Haemophilus: 4.8%; Veillonella: 4.25%; Fusobacterium: 4.14%; Prevotella: 3.93%; Ochrobactrum: 3.25%; Porphyromonas: 3.25%; Other: 47.95%. Normal lung: Streptococcus: 12.04%; Neisseria: 9.37%; Prevotella_7: 7.1%; Alloprevotella: 6.57%; Haemophilus: 5.65%; Prevotella: 5.28%; Porphyromonas: 4.78%; Veillonella: 4.53%; Fusobacterium: 3.96%; Stenotrophomonas: 3.86%; Other: 47.95% |

| Gomes S et al. (2019) |

Portugal | subjects undergoing bronchoscopy for evaluation of lung disease at three hospitals in Portugal | 49 | Microbiota in LC vs controler | Sample collection was targeted toward affected lung segments and done by bronchoscope wedging into subsegmental lung regions; was used only bronchoscope working channel washes, which were done twice with a minimum volume of 15 mL (0.9% saline solution) | V3-V4, V4-V6 regions of the 16S rRNA gene DNA Mini kit (Qiagen) |

Simpson and Shannon SCC cases were in average more diverse than ADC |

At phylum level: Proteobacteria 38.7%; Firmicutes 25.4%; Actinobacteria 16.5%; Bacteroidetes 13.3%; Spirochaetes 2.2%; Fusobacteria 2.1%; TM7 0.7%; OD1 0.5%; SR1 0.3%; Tenericutes 0.2%; Synergistetes 0.1%; Others 0.0%; At genus level: Haemophilus 29.5%; Streptococcus 10.9%; Corynebacterium 8.2%; Actinomyces 7.4%; Prevotella 5.8%; Veillonella 5.0%; Neisseria 3.6%; Selenomonas 2.8%; Parvimonas 2.4%; Porphyromonas 2.4%; Aggregatibacter 2.1%; Treponema 2.1%; Fusobacterium 2.1%; Propionibacterium 2.0%; Bulleidia 1.9%; Peptostreptococcus 1.2%; Pseudomonas 1.1%; Granulicatella 0.9%; Oribacterium 0.9%; Actinobacillus 0.8%; Bifidobacterium 0.6%; Campylobacter 0.5%; Sphingobacterium 0.5%; Staphylococcus 0.5%; Sphaerochaeta 0.5%; Filifactor 0.4%; Leptotrichia 0.4%; Scardovia 0.3%; Stenotrophomonas 0.3%; Moraxella 0.3%; Capnocytophaga 0.3%; Rothia 0.2%; Lactobacillus 0.2%; Megasphaera 0.2%; Morganella 0.2%; Acholeplasma 0.2%; Flavobacterium 0.1%; Catonella 0.1%; Aerococcus 0.1%; Cupriavidus 0.1%; TG5 0.1%; Sphingomonas 0.1%; Phenylobacterium 0.1%; Pedobacter 0.1%; Dialister 0.1%; Others 0.1% |

| Seixas S et al (2021) |

Portugal | did not include in the non-LC group any subject with a primary diagnosis of COPD or ILD. No healthy controls were collected. For second goal, was selected three homogenous patient groups with a single CLD diagnosis (controlled for other comorbidities) |

49 | LC vs other lung disease | Sample collection targeted affected lung segments BALF samples had a minimum volume of 15 mL (0.9% saline solution) and were initially stored by pulmonologists at − 20 to 4 °C according to the facilities available at the participating hospitals. Samples were then transported on ice to research centers where they were stored at − 80 °C until needed |

Illumina MiSeq technology, performed 16S ribosomal rRNA targeted region V4 DNA Mini kit (Qiagen) |

Shannon, ACE, Simpson, Fisher and Phylogenetic (Faith’s) diversity indices Alpha-diversity indices did not vary significantly between LC and non-LC groups |

At phylum level: Firmicutes 47.11%; Proteobacteria 31.35%; Bacteroidetes 15.52%; Actinobacteria 2.80%; At genus level: Escherichia/Shigella 8.80 %; Bacillus 7.66%; Streptococcus 7.45%; Salmonella 7.40%; Staphylococcus 7.27 %; Lactobacillus 6.41 %; Prevotella 6.09%; Veillonella 6.00 %; Pseudomonas 3.56%; Haemophilus 3.21 %; Others (each <1%) |

| Lee SH et al. (2016) |

South Korea | Patients who were admitted for evaluation of lung masses were prospectively enrolled in this study at a 2500-bed tertiary uni-versity medical centre in Seoul, South Korea between May and September 2015. Excluded: less than 20 years of age, pregnant, or had undergone any procedure other than bronchoscopy to evaluate the lung mass. |

20 | characterized and compared the microbiomes of patients with lung cancer and those with benign mass-like lesions. | topical anaesthesia (lido-caine) by nebulizer and then were sedated with midazolam and fentanyl.. BAL was performed following a standardized protocol on the opposite side of the lung mass, and 10 mL of BALF was acquired from each patients using about 30 ml sterile 0.9% saline. If a patient had a lung mass on the right upper lobe, BAL was performed on the left upper lobe | Illumina HiSeq technology, performed 16S ribosomal rRNA targeted region V1-V3 |

Chao1 estimation and Shannon more complex diversity with higher abundance and α-diversity |

At phylum level: Bacteroidetes: 39.5%; Firmicutes: 29.7%; Proteobacteria: 22.8%; Fusobacteria: 4.5%; Actinobacteria: 2.1%; Spirochaetes: 0.4%; TM7: 0.5%; SR1: 0.3%; Tenericutes: 0.1% At genus level: Prevotella: 30.8%; Neisseria: 13.8%; Veillonella: 11.4%; Streptococcus: 10.9%; Haemophilus: 7.2%; Alloprevotella: 6.1%; Fusobacterium: 2.2%. Megasphaera: 2.2%; Porphyromonas: 2.0%; Leptotrichia: 1.8%; Campylobacter: 1.1%; Actinomyces: 0.8%. |

| Liu B et al. (2022) | China | patients with LC were recruited in the Zibo Municipal Hospital. The exclusion criteria included the uses of antibiotics, corticoids, probiotics, prebiotics or immunosuppressive drugs in the past 3 months; hypertension; diabetes; previous airway surgery; preoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy; and atomization treatment |

7 | excavate the features of the lung microbiota and metabolites in patients and verify potential biomarkers for lung cancer diagnosis. |

Sterile saline samples of bilateral lungs were obtained by bronchoscopy in patients with LC. Paired samples of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) included the one from the cancerous lobe and the other from the contralateral noncancerous lobe. |

Illumina MiSeq technology, performed 16S ribosomal rRNA targeted region V3-V4 FastDNA Spin Kit (MP Biomedicals, Shanghai, China) |

Shannon, Chao, ace Lower abundance in alpha diversity |

At phylum level: Proteobacteria 45.05%; Firmicutes 28.31%; Bacteroidota 14.89%; Actinobacteriota 7.15%; Fusobacteriota 2.41%; Patescibacteria 1.25%; others 0.94%; At genus level: Pseudomonas 35.14%; Streptococcus 14.34%; Prevotella 9.55%; Neisseria 6.81%; Veillonella 4.85%; Actinomyces 4.6%; Granulicatella 3.53 %; Alloprevotella 3.25%; Leptotrichia 1.27 %; Fusobacterium 1.13 %; Porphyromonas 1.12 %; Haemophilus 1.07 %; Rhodococcus 0.91 %; Klebsiella 0.05 %; Lactobacillus 0.12 %; Bacillus 0.11 %; others 12.15 %; |

| Jang, H.J. et al. (2023) |

South Korea | patients who were pathologically diagnosed with NSCLC |

84 | the histological type-based differences in the lung microbiomes of patients with lung cancer. |

topical anesthesia (lidocaine) via nebulizer; sedation with midazolam and fentanyl when the bronchoscope arrived in the “involved” airway containing lung masses or lung nodules, the bronchi were flushed with 30 to 50 mL of sterile saline (0.9%). Approximately 15 mL of BAL fluid samples were obtained from each patient for sequencing analysis. BAL fluid samples were immediately placed at –70°C in a freezer, and DNA extraction was conducted within 24 hours |

Illumina MiSeq technology, performed 16S ribosomal rRNA targeted region V3-V4 |

Shannon and Simpson α -diversity was different between the two types of lung cancer. |

At phylum level: ADK Bacteroidetes 40.8%; Proteobacteria 24.9%; Firmicutes 24.1%; Fusobacteria 6.0%; Actinobacteria 2.8% SCC Bacteroidetes 35.0%; Firmicutes 29.3%; Proteobacteria 27.8%; Fusobacteria 3.8%; Actinobacteria 3.3%; |

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.2.1. Studies Objective

3.2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

3.2.3. Bronchoalveolar Lavage Sample Collection

3.2.4. Study Conclusions

3.3. Proportional Distribution of Microbial Phyla and Genera in Lung Cancer

3.4. Patient Demographics and Tumor Histology in Selected Studies

3.5. Alpha Diversity

4. Discussion

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020 GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ursell, L.K.; Metcalf, J.L.; Parfrey, L.W.; Knight, R. Defining the human microbiome. Nutr Rev. 2013, 70, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Luo, J.L.; Ali, M.K.; Spiekerkoetter, E.; Nicolls, M.R. The Human Respiratory Microbiome: Current Understandings and Future Directions. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2023, 68, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natalini, J.G.; Singh, S.; Segal, L.N. The dynamic lung microbiome in health and disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023, 21, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Steenhuijsen Piters, W.A.A.; Binkowska, J.; Bogaert, D. Early Life Microbiota and Respiratory Tract Infections. Cell Host Microbe. 2020, 28, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, M.; Ege, M.J. The Lung Microbiome E vM, editor.: European Respiratory Society; 2019.

- Mathieu, E.; Escribano-Vazquez, U.; Descamps, D.; Cherbuy, C.; Langella, P.; et al. Paradigms of lung microbiota functions in health and disease, particularly, in asthma. Frontiers. 2018, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarner, F.; Malagelada, J.R. Gut flora in health and disease. Lancet. 2003, 361, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagi, K.; Huffnagle, G.B.; Lukacs, N.W.; Asai, N. The Lung Microbiome during Health and Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 10872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Sun, R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Z.; She, X.; et al. Lung microbiome alterations in NSCLC patients. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 11736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczynski, J.; Liu, Z.; Lozupone, C.; McDonald, D.; Fierer, N.; et al. Microbial community resemblance methods differ in their ability to detect biologically relevant patterns. Nature methods. 2010, 7, 813–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloss, P.D.; Westcott, S.L.; Ryabin, T.; Hall, J.R.; Hartmann, M.; et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7537–7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, A.L.; Riddle, S.; McPhillips, T.; Ludäscher, B.; Eisen, J.A. Introducing W.A.T.E.R.S.: a Workflow for the Alignment, Taxonomy, and Ecology of Ribosomal Sequences. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010, 11, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, J.R.; Wang, Q.; Cardenas, E.; Fish, J.; Chai, B.; et al. The Ribosomal Database Project: improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, D141–D145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Kuczynski, J.; Stombaugh, J.; Bittinger, K.; Bushman, F.D.; et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010, 7, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huse, S.M.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Fodor, A.A. A Core Human Microbiome as Viewed through 16S rRNA Sequence Clusters. PLoS ONE. 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome biology. 2011, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.J.; CJKKYSKYKSea. Relationship of the lung microbiome with PD-L1 expression and immunotherapy response in lung cancer. Respir Res. 2021, 22, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.J.; Lee, E.; Cho, Y.J.; Lee, S.H. Subtype-Based Microbial Analysis in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2023, 86, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, M.; An, T.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z. Characterization of Microbiota in Cancerous Lung and the Contralateral Non-Cancerous Lung Within Lung Cancer Patients. Front Oncol. 2020, 10, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.; Cavadas, B.; Ferreira, J.C.; Marques, P.I.; Monteiro, C.; Sucena, M.; et al. Profiling of lung microbiota discloses differences in adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 12838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seixas, S.; Kolbe, A.R.; Gomes, S.; Sucena, M.; Sousa, C.; Rodrigues, L.V.; et al. “Comparative analysis of the bronchoalveolar microbiome in Portuguese patients with different chronic lung disorders. Scientific reports. 2021, 11, 15042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liao, J.; Ding, Y.; Fang, X.; et al. A Preliminary Study of Microbiota Diversity in Saliva and Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid from Patients with Primary Bronchogenic Carcinoma. Med Sci Monit. 2019, 25, 2819–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Sung, J.Y.; Yong, D.; Chun, J.; Kim, S.Y.; Song, J.H.; et al. Characterization of microbiome in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with lung cancer comparing with benign mass like lesions. Lung Cancer. 2016, 102, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingula, R.; Filaire, E.; Molnar, I.; Delmas, E.; Berthon, J.Y.; Vasson, M.P.; et al. Characterisation of microbiota in saliva, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, non-malignant, peritumoural and tumour tissue in non-small cell lung cancer patients: a cross-sectional clinical trial. Respir Res. 2020, 21, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu B, Li Y, Suo L, Zhang W, Cao H, Wang R et all. l. 2022;12:1058436. Published 2022 Nov 15. Characterizing microbiota and metabolomics analysis to identify candidate biomarkers in lung cancer. Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 1058436.

- Zeng, W.; Zhao, C.; Yu, M.; Chen, H.; Pan, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Alterations of lung microbiota in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Bioengineered. 2022, 3, 6665–6677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, W.; Ma, W.; Wang, H.; Xu, K.; et al. Smoking related environmental microbes affecting the pulmonary microbiome in Chinese population. Sci Total Environ. 2022, 829, 154652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson, R.P.; Erb-Downward, J.R.; Freeman, C.M.; Lisa McCloskey, L.; Beck, J.M.; et al. Spatial Variation in the Healthy Human Lung Microbiome and the Adapted Island Model of Lung Biogeography. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2015, 12, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakasidis, E.; Kotsiou, O.S.; Gourgoulianis, K.I. Lung and Gut Microbiome in COPD. Journal of personalized medicine. 2023, 13, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, R.P.; Erb-Downward, J.R.; Martinez, F.J.; Huffnagle, G.B. The Microbiome and the Respiratory Tract. Annu Rev Physiol. 2016, 78, 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Shariff, M.; Chaturvedi, G.; Chaturvedi, G.; Sharma, A.; Goel, N.; et al. Comparative analysis of the alveolar microbiome in COPD, ECOPD, Sarcoidosis, and ILD patients to identify respiratory illnesses specific microbial signatures. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.J.; Nelson, C.E.; Brodie, E.L.; DeSantis, T.Z.; Baek, M.S.; et al. Airway microbiota and bronchial hyperresponsiveness in patients with suboptimally controlled asthma. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2011, 127, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun-Chieh, J.T.; Benjamin GWu Sulaiman, I.; Gershner, K.; Schluger, R.; et al. Lower Airway Dysbiosis Affects Lung Cancer Progression. Cancer discovery. 2021, 11, 293–307. [Google Scholar]

- Einarsson, G.G.; Comer, D.M.; McIlreavey, L.; Parkhill, J.; Ennis, M.; et al. Community dynamics and the lower airway microbiota in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, smokers and healthy non-smokers. Thorax. 2016, 71, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loverdos, K.; Bellos, G.; Kokolatou, L.; Vasileiadis, I.; Giamarellos, E.; et al. Lung Microbiome in Asthma: Current Perspectives. J Clin Med. 2019, 8, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.; Beck, J.M.; Schloss, P.D.; Campbell, T.B.; Crotherset, K.; et al. Comparison of the respiratory microbiome in healthy nonsmokers and smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013, 187, 1067–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.; Vella, G.; Galata, V.; Rentz, K.; Beisswenger, C.; et al. The composition of the pulmonary microbiota in sarcoidosis – an observational study. Respir Res. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molyneaux, P.L.; Cox, M.J.; Willis-Owen, S.A.; Mallia, P.; Russellet, K.E.; et al. The role of bacteria in the pathogenesis and progression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014, 190, 906–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, B.; Wu, B.G.; Kocak, I.F.; Sulaiman, I.; Schluger, R.; et al. Pleural fluid microbiota as a biomarker for malignancy and prognosis. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budden, K.F.; Shukla, S.D.; Rehman, S.F.; Bowerman, K.L.; Keely, S.; et al. Functional effects of the microbiota in chronic respiratory disease. Lancet Respir Med. 2019, 7, 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson, R.P.; Erb-Downward, J.R.; Huffnagle, G.B. Towards an ecology of the lung: new conceptual models of pulmonary microbiology and pneumonia pathogenesis. Lancet Respir Med. 2014, 2, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scher, J.U.; Joshua, V.; Artacho, A.; Abdollahi-Roodsaz, S.; Öckinger, J.; et al. The lung microbiota in early rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmunity. Microbiome. 2016, 4, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiscovitch-Russo, R.; Singh, H.; Oldfield, L.M.; Fedulov, A.V.; Gonzalez-Juarbe, N. An optimized approach for processing of frozen lung and lavage samples for microbiome studies. PLoS One. 2022, 17, Apr. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuhiro, K.; Tamiya, M.; Fujimoto, K.; Koyama, S.; Naito, Y.; Osa, A.; et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid reveals factors contributing to the efficacy of PD-1 blockade in lung cancer. JCI Insight. 2022, 7, e157915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doocey, C.M.; Finn, K.; Murphy, C.; Guinane, C.M. The impact of the human microbiome in tumorigenesis, cancer progression, and biotherapeutic development. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).