Submitted:

13 September 2024

Posted:

13 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

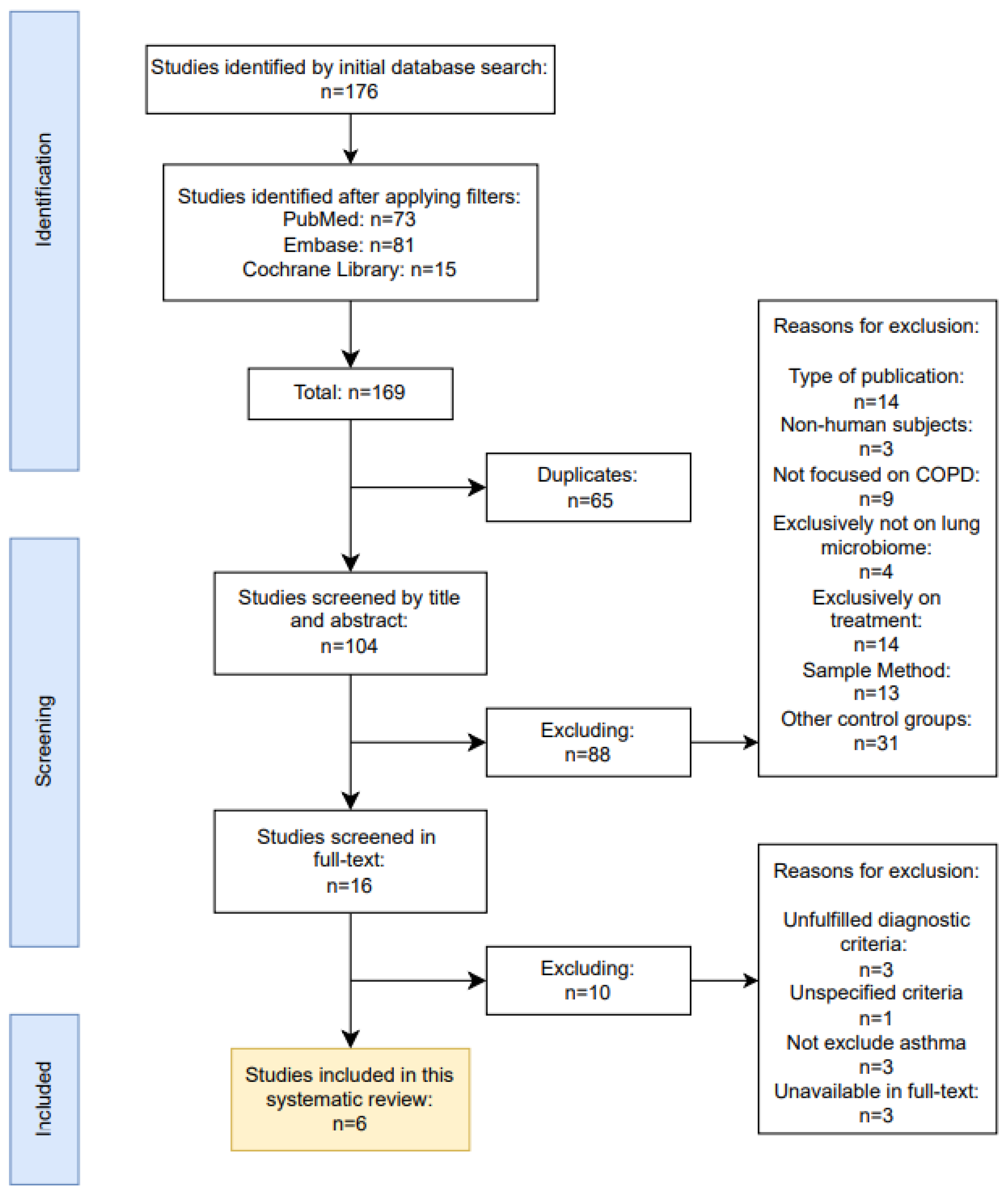

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Definition of Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.1.1. Characteristics of Excluded Studies

2.1.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.1. Community Diversity

3.2. Taxonomic Differences during Exacerbations

| Su et al. (2022)[68] | AECOPD | Proteobacteria 30.29% |

Firmicutes 29.85% |

Bacteroidetes 14.02% |

Streptococcus 14.31% |

Neisseria 11.60% |

UnidentifiedPrevotellaceae8.90% | Haemophilus 7.49% |

Veillonella 6.37% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stable | Firmicutes 31.63% | Bacteroidetes 28.94% | Proteobacteria 19.68% | Unidentified_ Prevotellaceae (15.69%) |

Streptococcus14.31% | Neisseria 12.13% |

Veillonella 7.38% |

Haemophilus 3.62% | |

| J. Wang et al. (2018)[67] | AECOPD | Firmicutes 60.99% | Actinobacteria 25.75% | Proteobacteria 5.59% | Streptococcus 26.59% |

Rothia 16.07% |

Staphylococcus 7.83% |

Abiotrophia 5.89% |

Lactobacillus 4.34% |

| Stable | Firmicutes 53.95% | Actinobacteria 33.47% | Bacteroidetes 4.69% | Streptococcus 34.49% |

Rothia 21.04% |

Lactobacillus 12.43% |

Lautropia (6.26%) |

Parvimonas 3.91% |

|

| Jubinville et al. (2018)[66] | AECOPD | Firmicutes 41% |

Proteobacteria 28% |

Bacteroidetes 25% |

Streptococcus 27% |

Prevotella 23% |

Moraxella 16% |

Veillonella 10% |

|

| Author | State | Phylum | Genus | ||||||

3.3. Potential Interactions within the Microbiome

3.4. Microbiome Stability

3.5. Exacerbation Phenotypes

3.6. Correlation with Clinical Indices

3.7. Functional Analysis

3.8. The Impact of Treatment

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Main Results in Context of the Current State of Research

4.2. Applicability of Evidence

4.3. Limitations of Included Studies and in the Retrieval Process of Studies

5. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

References

- Global Initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease. 2024 GOLD report [Internet]. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease - GOLD. 2023. Available from: https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/.

- Ko FW, Chan KP, Hui DS, Goddard JR, Shaw JG, Reid DW, et al. Acute exacerbation of COPD. Respirology [Internet]. 2016 Mar 30;21(7):1152–65. [CrossRef]

- Introduce to 16S rRNA and 16S rRNA Sequencing | CD Genomics Blog [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Jun 8]. Available from: https://www.cd-genomics.com/blog/introduce-to-16s-rrna-and-16s-rrna-sequencing/.

- Whiteside SA, McGinniss JE, Collman RG. The lung microbiome: progress and promise. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2021 Aug 2;131(15). [CrossRef]

- Tangedal S, Nielsen R, Aanerud M, Persson LJ, Wiker HG, Bakke PS, et al. Sputum microbiota and inflammation at stable state and during exacerbations in a cohort of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients. Singanayagam A, editor. PLOS ONE. 2019 Sep 17;14(9):e0222449. [CrossRef]

- Bouquet J, Tabor DE, Silver JS, Nair V, Tovchigrechko A, Griffin MP, et al. Microbial burden and viral exacerbations in a longitudinal multicenter COPD cohort. Respiratory Research. 2020 Mar 30;21(1). [CrossRef]

- Goolam Mahomed T, Peters RPH, Allam M, Ismail A, Mtshali S, Goolam Mahomed A, et al. Lung microbiome of stable and exacerbated COPD patients in Tshwane, South Africa. Scientific Reports. 2021 Oct 5;11(1). [CrossRef]

- Huang YJ, Sethi S, Murphy T, Nariya S, Boushey HA, Lynch SV. Airway Microbiome Dynamics in Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Journal of Clinical Microbiology [Internet]. 2014 Aug 1;52(8):2813–23. [CrossRef]

- O’Farrell HE, Shaw JG, Goh F, Bowman RV, Fong KM, Krause L, et al. Potential clinical utility of multiple target quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) array to detect microbial pathogens in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Journal of Thoracic Disease [Internet]. 2019 Oct [cited 2022 May 3];11(S17):S2254–65. [CrossRef]

- Yang J, Zhang Q, Zhang J, Ouyang Y, Sun Z, Liu X, et al. Exploring the Change of Host and Microorganism in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients Based on Metagenomic and Metatranscriptomic Sequencing. Frontiers in microbiology. 2022 Mar 16;13. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Bafadhel M, Haldar K, Spivak A, Mayhew D, Miller BE, et al. Lung microbiome dynamics in COPD exacerbations. The European Respiratory Journal [Internet]. 2016 Apr 1 [cited 2022 Apr 3];47(4):1082–92. [CrossRef]

- Bafadhel M, McKenna S, Terry S, Mistry V, Reid C, Haldar P, et al. Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine [Internet]. 2011 Sep 15;184(6):662–71. [CrossRef]

- Mayhew D, Devos N, Lambert C, Brown JR, Clarke SC, Kim VL, et al. Longitudinal profiling of the lung microbiome in the AERIS study demonstrates repeatability of bacterial and eosinophilic COPD exacerbations. Thorax. 2018 Jan 31;73(5):422–30. [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. clinicaltrials.gov. [cited 2024 Jul 3]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT01360398.

- Jubinville E, Veillette M, Milot J, Maltais F, Comeau AM, Levesque RC, et al. Exacerbation induces a microbiota shift in sputa of COPD patients. Zoetendal EG, editor. PLOS ONE. 2018 Mar 26;13(3):e0194355. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Chai J, L S, Zhao J, Chang C. The sputum microbiome associated with different sub-types of AECOPD in a Chinese cohort. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2020 Aug 18;20(1). [CrossRef]

- Su L, Qiao Y, Luo J, Huang R, Li Z, Zhang H, et al. Characteristics of the sputum microbiome in COPD exacerbations and correlations between clinical indices. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2022 Feb 5;20(1). [CrossRef]

- Xue Q, Xie Y, He Y, Yu Y, Fang G, Yu W, et al. Lung microbiome and cytokine profiles in different disease states of COPD: a cohort study. Scientific Reports [Internet]. 2023 Apr 7 [cited 2023 Dec 21];13(1):5715. [CrossRef]

- Toraldo DM, Conte L. Influence of the Lung Microbiota Dysbiosis in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Exacerbations: The Controversial Use of Corticosteroid and Antibiotic Treatments and the Role of Eosinophils as a Disease Marker. Journal of Clinical Medicine Research [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2022 Jun 6];11(10):667–75. [CrossRef]

- Li W, Wang B, Tan M, Song X, Xie S, Wang C. Analysis of sputum microbial metagenome in COPD based on exacerbation frequency and lung function: a case control study. Respiratory Research. 2022 Nov 19;23(1). [CrossRef]

- Hajishengallis G, Darveau RP, Curtis MA. The keystone-pathogen hypothesis. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2012 Sep 3;10(10):717–25. [CrossRef]

- Larsson K. Inflammatory markers in COPD. The Clinical Respiratory Journal. 2008 Sep 3;2:84–7. [CrossRef]

| Reasons for exclusion | Diagnosis criteria unfulfilled | Diagnostic criteria unspecified | Failed to exclude patients with concomitant asthma | Unavailable in full-text |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | South Africa | China | Bulgaria, Czech Republic and USA | Spain |

| Publication year | 2014 | 2022 | 2020 | 2019 |

| Title | Bacterial airway microbiome dynamics in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Exploring the Change of Host and Microorganism in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients Based on Metagenomic and Metatranscriptomic Sequencing | Microbial burden and viral exacerbations in a longitudinal multicenter COPD cohort | Sputum Microbiome Dynamics in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients during an Exacerbation Event and Post-Stabilization |

| Author | Huang et al. [58] | Yang et al.[60] | Bouquet et al.[56] | López Caro et al.[53] |

| Outcomes | OTU RA, D, Network analysis (OTU, CI), Eos SG | OTU RA, D, Markov chain analysis | OTU RA, D, quantity, GOLD SG | OTU RA, D, Eos SG, RFM | OTU RA, D, discriminators, CI correlation, functional state | OTU RA, D, CI correlation, functional discriminators state, SG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample collection | 376 (137 AE, 106 S*, 136 PT**, 97 R7***; 87 P) |

584 (161 AE, 423 S; 104 P) |

18 (9 AE, 9 S; 9 P) |

68 (36 AE, 4 S****, 18 R**, 10 H) |

76 (28 AE, 23 S, 15 R**, 10 H) |

113 (35 AE, 35 PT, 43 S*****; 35 P) |

| Methods | Cohort | Cohort | Cohort | Cross-sectional | Cross-sectional | Cohort |

| Location | United Kingdom | United Kingdom | Canada | China | China | China |

| Publication year | 2016 | 2018 | 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | 2023 |

| Title | Lung microbiome dynamics in COPD exacerbations | Longitudinal profiling of the lung microbiome in the AERIS study demonstrates repeatability of bacterial and eosinophilic COPD exacerbations | Exacerbation induces a microbiota shift in sputa of COPD patients | The sputum microbiome associated with different sub-types of AECOPD in a Chinese cohort | Characteristics of the sputum microbiome in COPD exacerbations and correlations between clinical indices | Lung microbiome and cytokine profiles in different disease states of COPD: a cohort study |

| Author | Z. Wanget al.[62] | Mayhew et al. [64] | Jubinville et al.[66] | J. Wanget al.[67] | Suet al.[68] | Xue et al.[69] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).