The analysis focuses on the temperature increase caused by Joule’s law, created by current flow in a closed circuit. Precise control of the electric current determines the temperature increase, guiding the selection of physical parameters and materials for the thermal bed.

The device includes all design phases, from introducing the fluid mixture to completing the DNA amplification process. Two optoelectronic sensors play a key role in process control: one for temperature measurement and another for color detection, monitoring the amplification progress. The temperature is sampled at a single reference point to correlate with the sample’s temperature, verified through repeated simulations with varying system parameters. Detecting the precise completion of the process, especially with the miniaturized motility sensor, presents a challenge. An optical sensor detects color changes due to turbidity shifts in the sample, calibrated to ensure accurate control of the -LAMP process with miniaturized electro-optical sensors and precise temperature measurements. Introducing a small volume of fluid samples for DNA testing poses a technological challenge not covered in this work.

This paper presents a model for the electric current distribution leading to controlled temperature increases, crucial for a DNA amplification device operating at 62 °C. We introduce a novel thermal bed design that utilizes advances in semiconductor technology, specifying the thermoelectric parameters of copper tracing for effective implementation. Using the finite element method (FEM), we simulate the copper trace as a thermal bed for the sample chamber and evaluate its temperature performance under various electrical current levels.

2.1. Thermal Bed Design

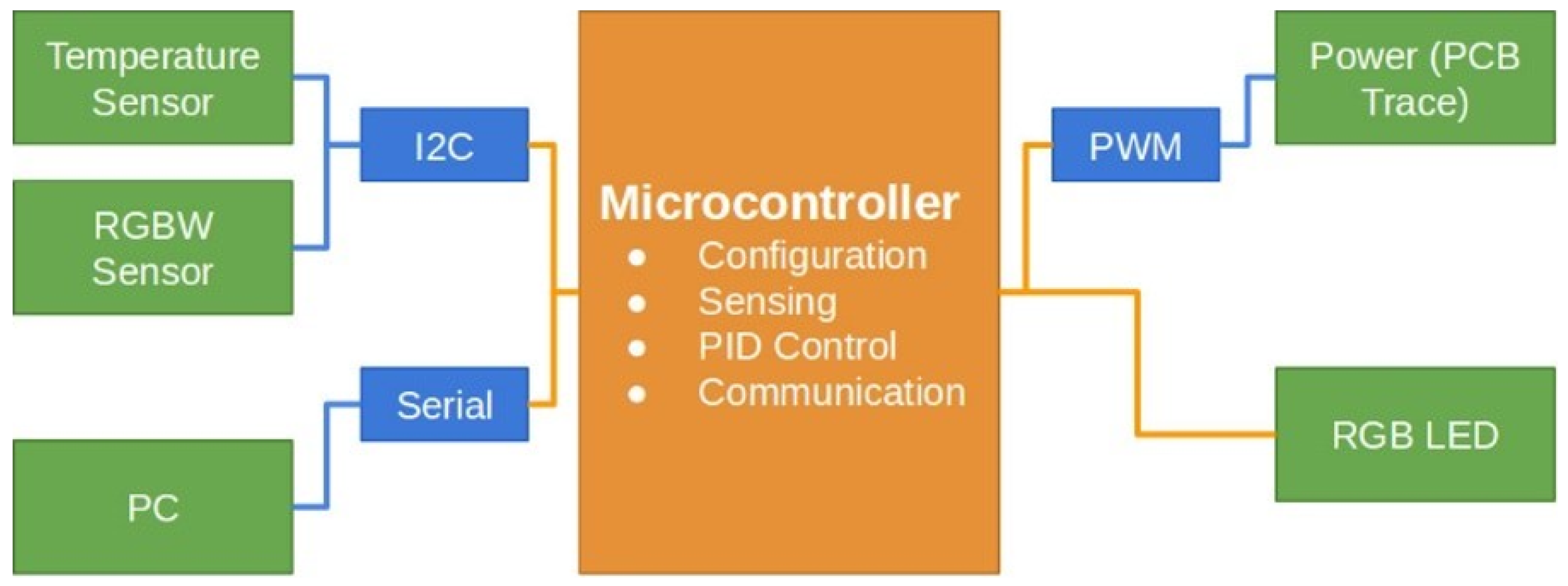

Figure 1 shows the block diagram presenting the architecture of the DNA amplification device. The hardware includes the copper trace heated with current whose magnitude is defined by the pulse width modulation (PWM) method. The thermoelectric system generates the necessary heat to elevate and maintain the temperature of the sample chamber contents. Its control subsystem ensures that the temperature remains within set limits, utilizing a copper trace integrated into a printed circuit board (PCB). A temperature sensor is strategically placed inside the fluid chamber to monitor conditions. The microprocessor adjusts the current through pulse width modulation (PWM) to regulate the temperature as needed. A modified optical turbidity sensor functions as an optical color sensor to detect the completion of DNA amplification. The microprocessor interprets the output of this sensor to identify when the color change indicates that DNA amplification is complete.

In our system design, hardware elements are represented with orange boxes, communication protocols with blue lines and boxes, and sensors, detectors, PC interface, and the power system for the PCB trace are represented with green boxes. A dsPIC® DSC microprocessor manages the device’s control, while the power supply on the upper right manages the energy distribution to the thermoelectric heating stage via PWM. An RGB LED is digitally controlled by the microprocessor for process visualization. Data transmission is illustrated in the lower left-central part, demonstrating compatibility with Bluetooth, ZigBee, and any wireless or wired communication support device.

We developed a mathematical model to evaluate the current distribution across the PCB traces, optimizing the physical and mechanical parameters and the geometric configuration for implementation on the chip. Thermoelectric simulations using the finite element method (FEM) were conducted to confirm that the proposed increase in temperature per current is appropriate. The PCB design software also implemented the copper trace configuration to simulate and ensure a homogeneous thermal distribution throughout the fluid volume.

After simulations, the selection of electronic components for the test PCB card was performed to validate the design. The thermal bed uses a specific current tailored to the PWM to match the electrical specifications of the components, including transistors and controllers, ensuring the functionality and longevity of the device. The DNA amplification process, accelerated using the procedure, operates at a stable temperature of . The methodologies described can also model and optimize other methods that require different temperatures, such as those starting around .

Providing a controlled temperature environment is crucial for a range of processes and applications in fields such as biology, medicine, chemistry, and forensics [

7,

28]. The primary objective is to replicate DNA or develop new methodologies for analyzing biological events. Various heating mechanisms have been implemented to control the temperature in these systems. Recent advances have focused on the thermal management of

-LAMP devices, including silicon arrays for temperature control in PCR amplification [

24,

25], micro-coils for temperature regulation in Lab-On-Chip platforms, and thermistors and thin-film manufacturing for PCR applications [

27,

28,

34,

35].

This study follows the IPC Industrial and Thermoelectric Standards Model (Association of Connecting Electronic Industries [

36]). Following the selection of the physical characteristics of the copper trace and the power supply, the simulations analyzed the thermal resistance of the PCB, establishing the relationship between the increase in temperature and the required electrical current. The current and its control unit automatically provide the necessary temperature increase without manual intervention.

To optimize DNA amplification, thermal specifications must be met. The control mechanisms raise the temperature to the desired operating point and maintain it for the duration required for DNA amplification. Subsequently, the mechanical parameters of the PCB trace are defined.

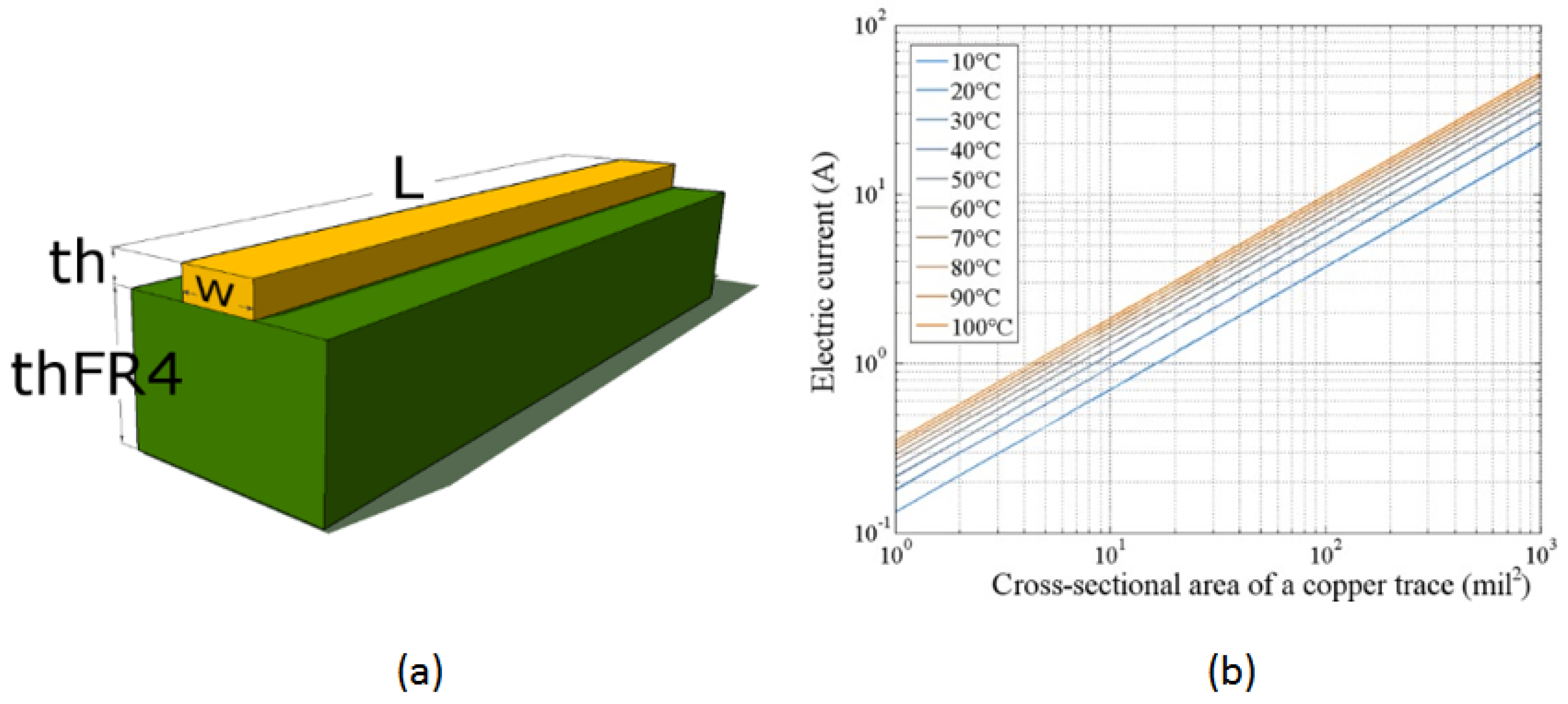

Figure 2 illustrates the characteristics of the PCB used in the thermal bed design.

Figure 2(a) shows the cross-section of an analyzed PCB segment. The thickness of copper remains consistent throughout the PCB layer, according to the chosen copper foil: 1 Oz ft

−2 in this case. The width of the copper trace is defined in the design program parameters and measured in mils (0.001 in = 1 mil = 0.025 mm). Modifying the width of the trace adjusts its impedance, allowing control over the current capacity for that segment of the copper trace. The target temperature increase and electrical current must be considered to propose an optimal trace width.

The design and manufacturing standard for PCBs,

, proposes an approximation of the increase in temperature of a trace as a function of the electric current flowing through it. This expression limits the physical geometry of the width of the trace relative to the amount of current given by

Here, I is the electrical current in amperes [A], A is the transverse cross-sectional area in , is the temperature increase in [K], and is a constant trace layer of copper such that: = , = . Here, is used for the external layer of the PCB and for its internal layer, known as stripline and microstrip, respectively. This approach works well for panel PCBs with a dielectric thickness of of material and copper conductors with a width of or greater.

Once we have selected the power supply, we can deduce other system parameters from it. Specifically, a copper trace of 10-mil

width and a thickness of 1 Oz

(a standard PCB specification, equal to

) of copper is considered. Then, the current may be limited to less than 1 A. According to the first law of thermodynamics, the total energy of a closed system is conserved. The only way the power of a system changes is when it crosses the boundaries of the system. This law further determines the way energy crosses system boundaries[

37]. The following expression is valid for a closed system:

Here

is the total change in power stored in the system in [W];

is the net heat transferred to the system per unit time, also in [W]; and

is the net amount of work generated by the system per unit time. The derivative of the first law of thermodynamics may also be applied to a controlled volume or even an open system. This analysis is important for determining the unknown temperature, as in our trace segment. Using it, we choose the current necessary for the requisite temperature increase, considering that no external (mechanical) power sources or sinks exist that might provoke a temperature change. The parameter obtained through this analysis is the temperature change rate as a function of current. The first law of thermodynamics and its derivative with time apply at any instant; therefore, the following expression is valid.

Here,

in [W] is the rate of increase of energy within a volume in [W],

is the rate of input energy transfer into the volume in [W],

is the rate of energy transfer out of a volume, and

is the rate of energy generation, likewise in [W]. All of this takes place according to the geometry and materials of the components. Using Eq. 3, we determine the current necessary to increase the temperature, considering that no external mechanical power sources could generate a temperature change. Equation 3 may be interpreted to mean that the rate of increase of thermal or mechanical energy stored in a volume must be equal to the rate at which thermal and mechanical energy enter the volume minus the rate at which thermal and mechanical energy leave the volume, plus the rate at which all energy (thermal and other) is generated within the volume.

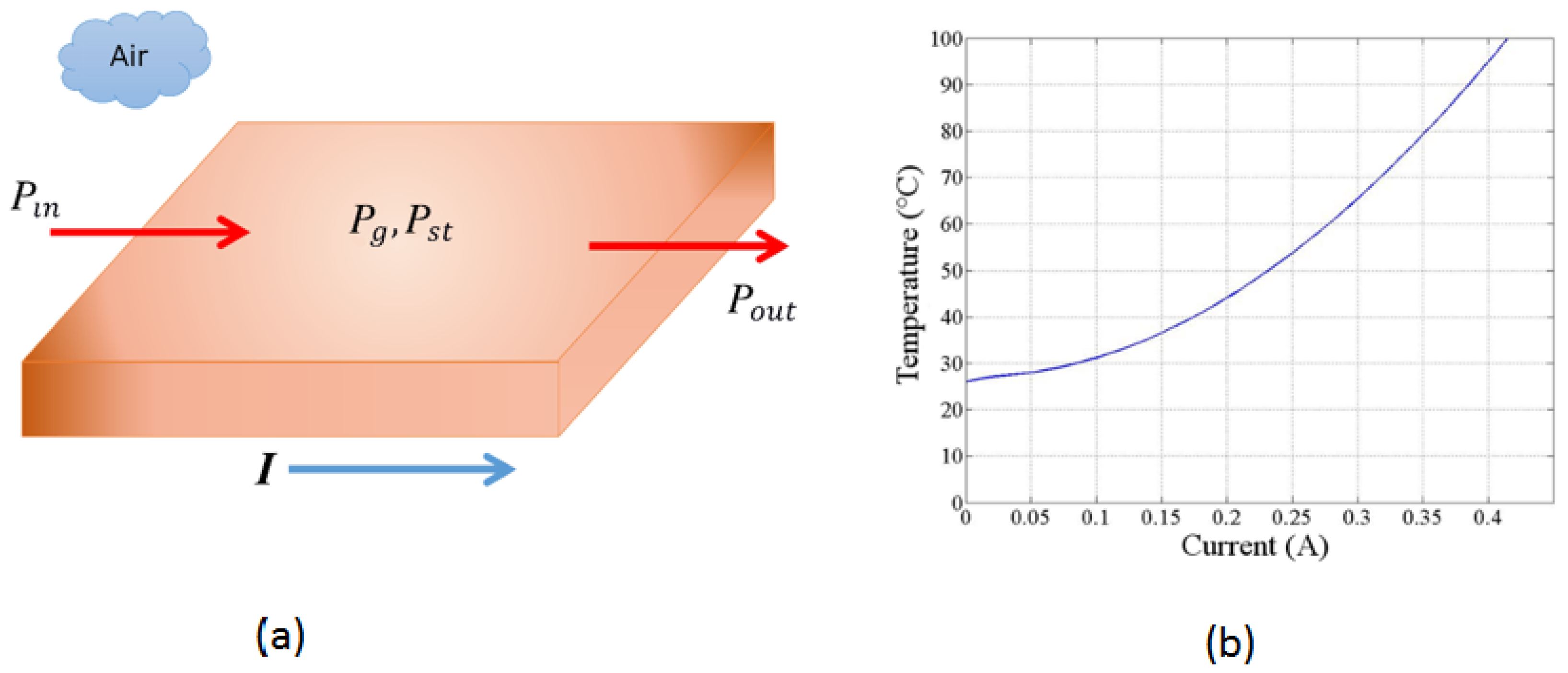

Figure 3(a) illustrates how the energy of the system changes with time for a short copper segment, representing a defined volume, and how it is interconnected. The electric current

I controls the amount of thermal energy generated per unit of time inside the volume using the resistive heating mechanism. Assuming that no energy flows into the short segment of the copper trace, we obtain the following expression from Equation 3:

The resistive losses produce the rate of energy dissipation, then

Here,

I is the electrical current in amperes [A],

is the electrical resistance of the copper trace per unit of length [

], and

L is the length of the trace segment in [mm]. The temperature increment of the copper trace is uniform within the volume because a concise segment is considered. This temperature increase may be found as a function of the energy increment rate within the copper trace volume.

Where

q is the rate of energy increment per unit of volume. Substituting the volume parameters for the geometry in our design, we have

Here,

w and

are the width and thickness of the copper trace, in [

m] respectively. In this system, thermal energy includes convection and radiative transfers away from the surface of the copper trace. The next equation represents the convection and radiative losses, considering only the surfaces exposed to air and the background temperature[

37].

Where

h is the heat transfer coefficient for convection in [

];

is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant,

X

[

];

is the emissivity of copper that is between

and

, without units; and

and

are the temperatures of the outer layer of the copper trace volume and of the background in [K], respectively. The rate of energy increase within a volume is given by:

Here,

is the mass density in [

], c is the specific heat capacity in [

], and

V is the volume of the copper trace, [

]. In the case of the copper trace, the mass density is 8933

, and the specific heat capacity is 385 [

]. Substituting Equations 4 through 8 into Equation 9, we solve it for the copper trace’s temperature increase as a current function.

we summarize the quantities for the sake of completeness. T is the temperature increase in [K]; t is the time in [s]; I is the current in amperes, [A]; is the electrical resistance of the copper trace per unit length []; h is the convection heat transfer coefficient in [W K−1]; w is the width of the copper trace in [m]; is the thickness of the copper trace in [m]; L is the total length of the trace in [m]; and are the temperature of the outer layer of the copper volume and the environment, in [K], respectively; is the emissivity of the copper trace, between 0.03 and 0.04; is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, with the value of 5.67 x 10−8 W K−4; is the mass density of the copper trace, 8,933 ; c is the specific heat capacity of the trace, 385[]; and the star (*) denotes a product.

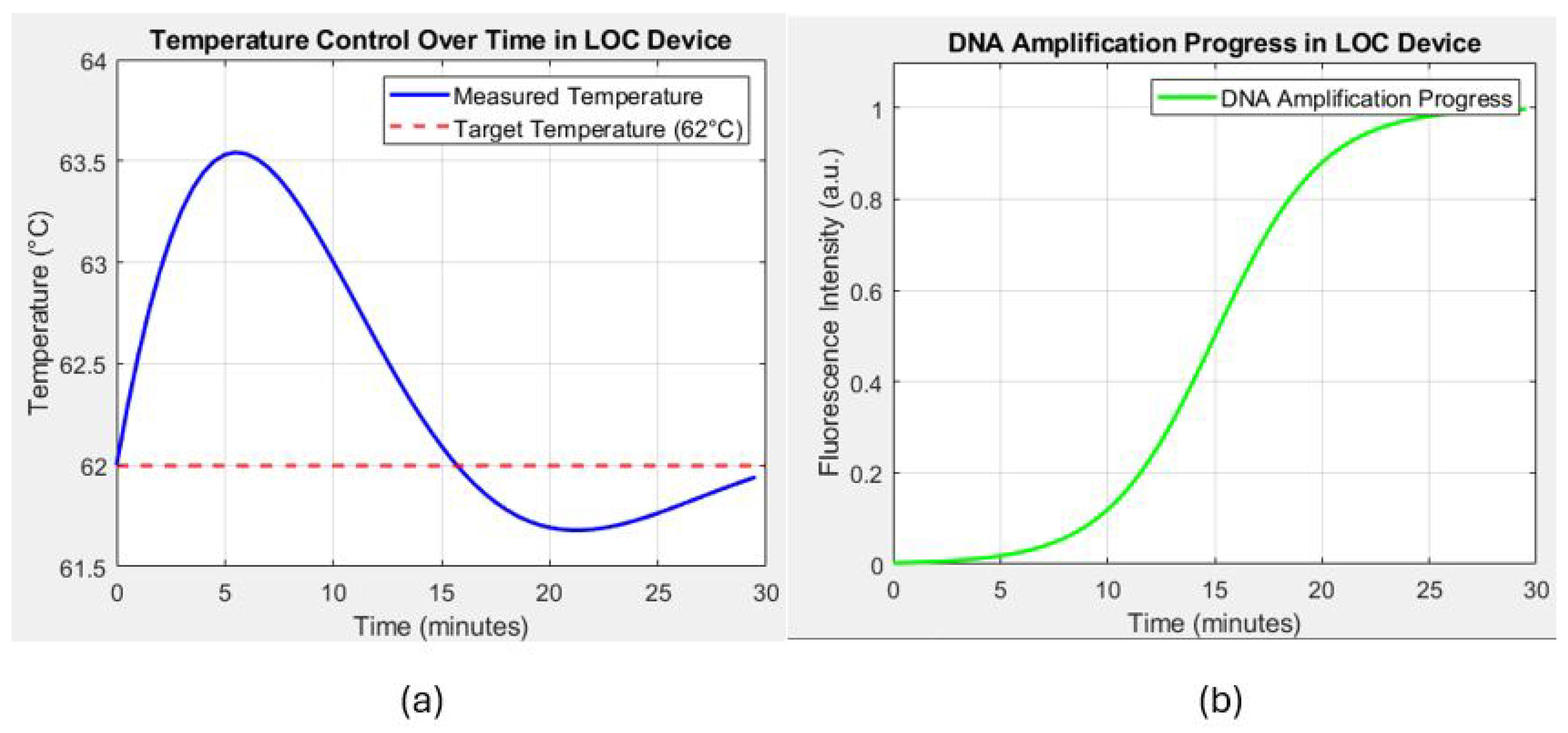

Equation 5 may be evaluated numerically. Our system is ten mils wide and 1 Oz ft-2 thick copper trace (as proposed in the design). We obtain the following numerical estimate for the increase in temperature as a current function for the proposed copper tracing using a numerical evaluation presented graphically in

Figure 3 (b). We see that any final temperature in the range between room temperature (25 °C) to above 100 °C can be reached with a current of less than 0.5 A through the trace. Thus, many processes may be achieved with the technique described here.

We note that a current smaller than 1 A is required to raise the temperature to the process temperature of 62 °C. To increase the system responsivity, the possibility of working with 1 to 2 W power supplies was also explored. Employing a power supply any larger than 1 W may damage the device itself or its constituent electronic components: the temperature increase may exceed their recommended operating conditions. When using a power source with power significantly smaller than 1 W, the system may take too long to reach, or it may never reach, the temperature required for the amplification process.

2.2. Finite Element Method (FEM) Simulations

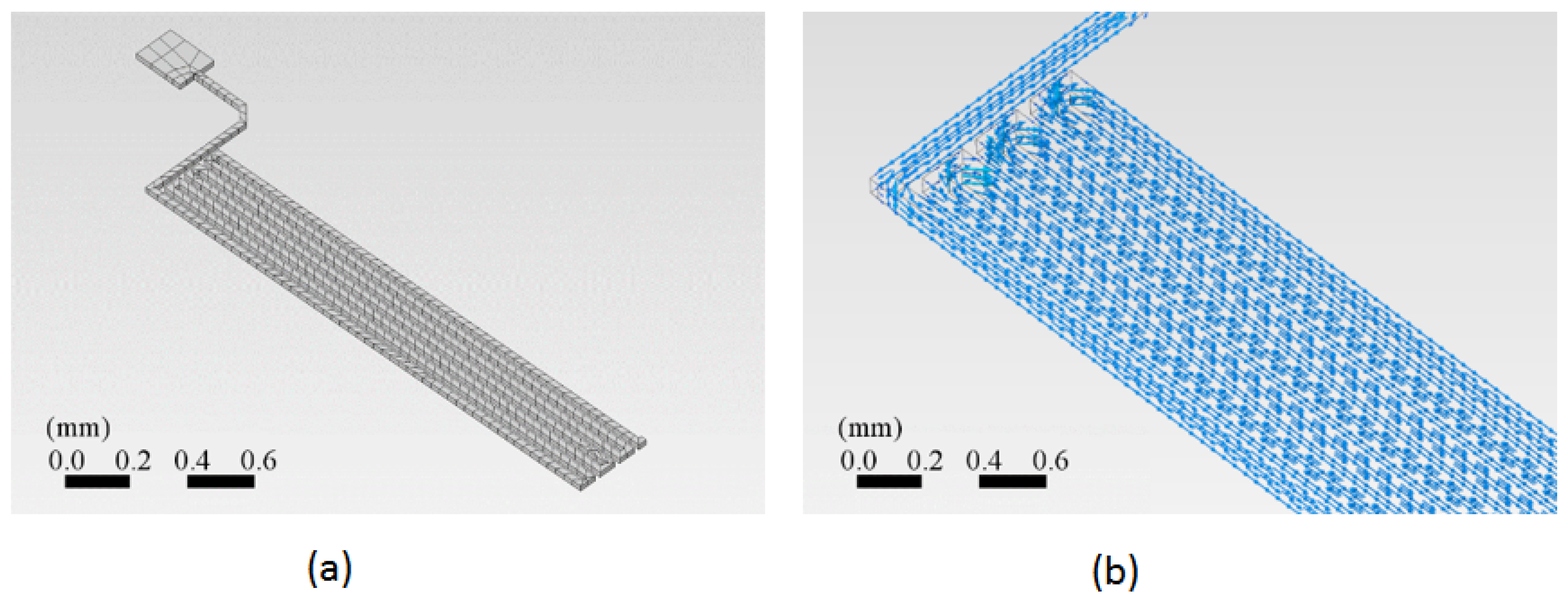

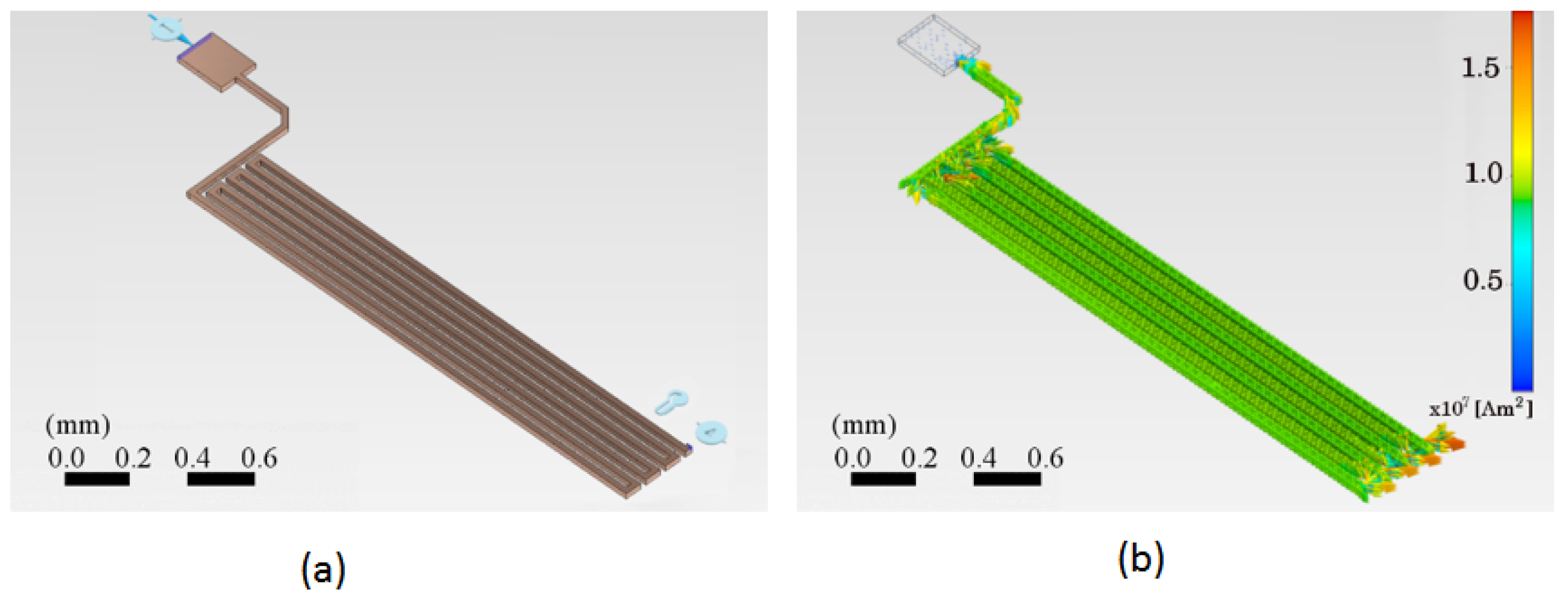

A section of the copper trace has been drawn in the ANSYS™ program. This simulation program works in the theory of finite elements for structures. Its dynamic mesh is presented in

Figure 4(a). The simulation was performed for an electric current input through a cooper trace to determine the current density distribution and the resulting temperature evolution through space and time. First, the current density inside the trace volume is calculated. The current density is a vector quantity whose magnitude is the electric current per unit area to the current flow’s direction.

Figure 4(b) The vector current density as a function of the location on the trace. The current density is related to the electric current as follows:

Again, I is the current in amperes, [A]; j is the current density in [A] and S is the surface area in [m2]. In our simulations, copper was considered the preferred material for selecting the trace. This material is also commonly used in the manufacturing of PCBs.

Figure 5 shows twoPCB trace schemes using the finite element method.

Figure 5(a) shows the trace with the initial parameters applicable to the system under design. The preliminary current of 500

mA is proposed for an initial temperature of 25 °C. In addition, an electrical reference potential and a fixed reference point for anchoring the motion are considered, shown in the lower right corner.

Figure 5(b) shows the distribution of the electric current density vectors throughout the system. It is observed that the magnitude of the current density is greatest when the trace changes direction by 90 degrees. Arrows represent the distribution of the electric current density vectors, their direction, and magnitude.

After calculating the electric current density vectors and using knowledge of the intrinsic parameters of the implemented trace material, it is finally possible to determine the temperature increase in the copper trace as a function of time using the finite element method[

38,

39,

40].

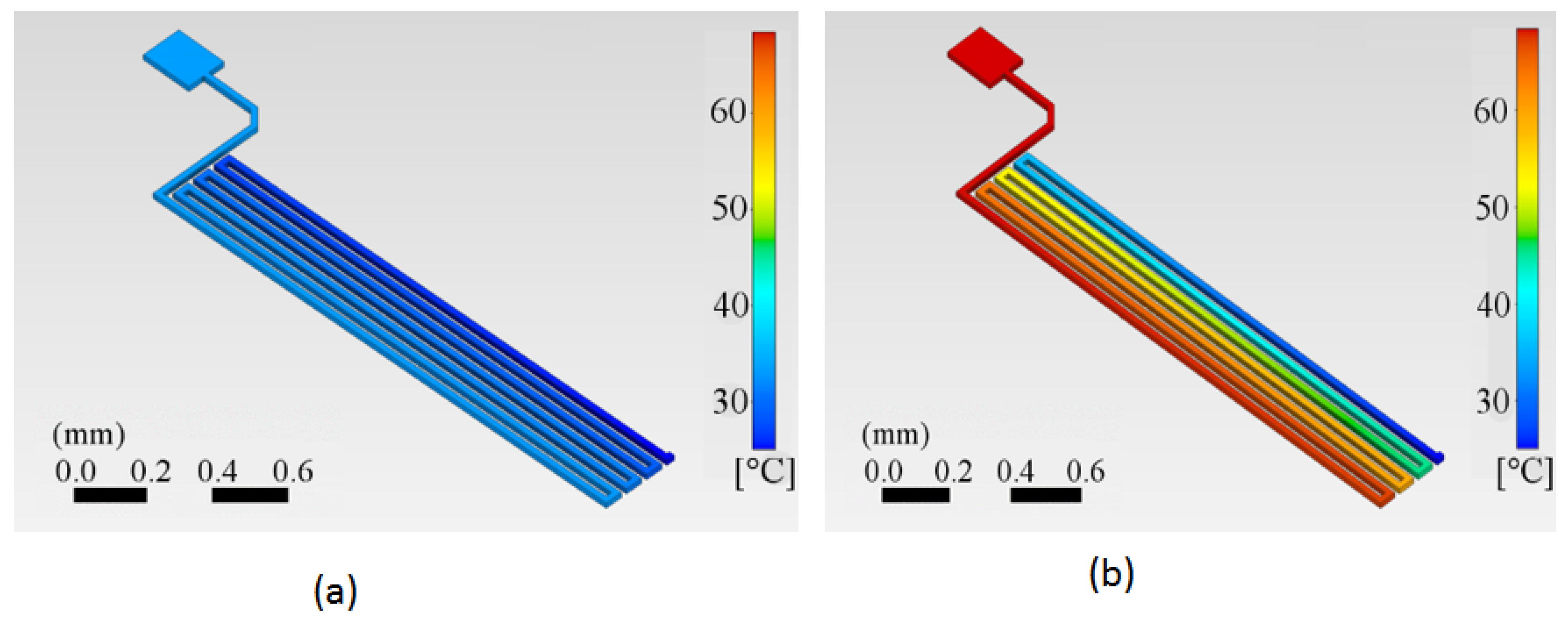

The calculated temperature distributions on the copper trace are shown for two specific times in

Figure 6(a) and 6(b). 10 and 11. We can appreciate how the trace starts at a reference temperature of 25 °C in

Figure 6 (a). The first half of the trace has already started to be heated at time t = 0.5 s, while the end segment remains at room temperature. After a specific, relatively short time at t = 2.5 s, the trace reaches the target temperature at least for the first half of the trace length, which in this case is 62 °C.

The simulations of the thermoelectric stage of the device are an iterative process, leading to ever-better design solutions compatible with the device’s requirements. With the final design, we are confident that the physical characteristics and thermal response of the unit are compatible with the device performance requirements. During the final, optimized design and simulation iteration we have determined that the trace configuration of 10 mil (0.254 mm) width and 1 Oz ft-2 (34.79 m) height is the optimal one for our prototype development.

2.3. Optoelectronic Sensor Integration

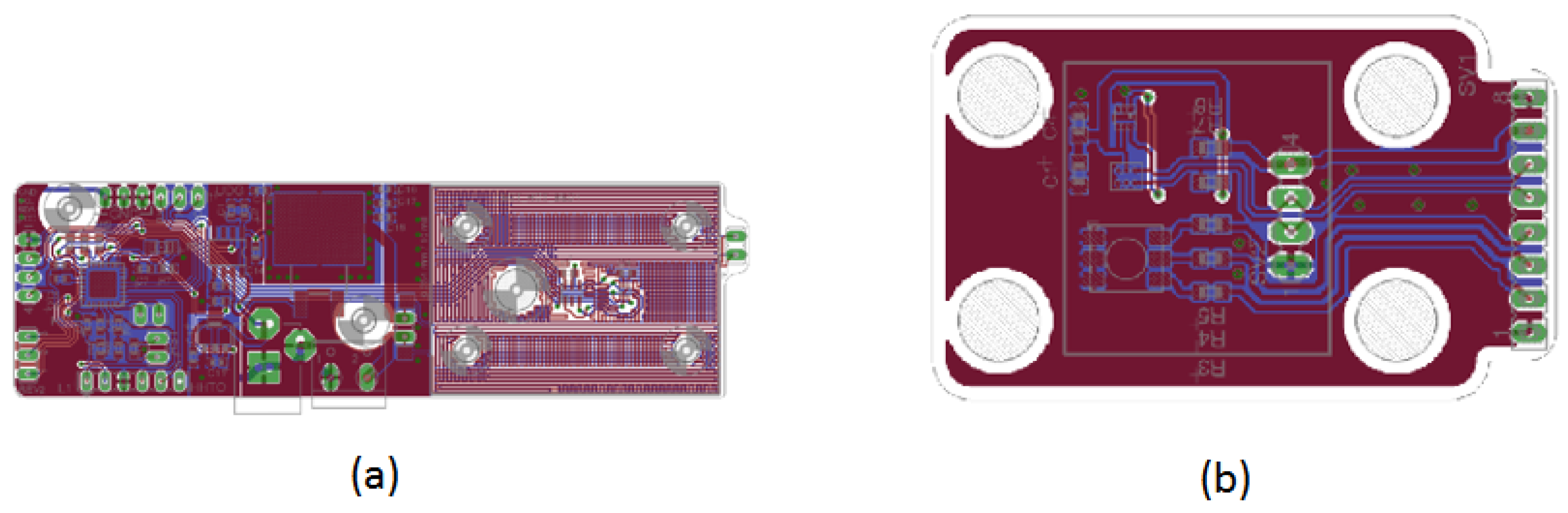

The geometric information of the parameters obtained with the thermal simulations is the data used in a PCB design program. The preliminary design resulting from the upper and lower layers of the thermal bed is shown in

Figure 7(a) and 7(b). The thermal stage of the PCB has an effective area of 39.7

X 28.45

. The thermal traces satisfy the design rule of 10 mils (0.254 mm) wide and 10 mils (0.254 mm) of spacing between the traces.

The central hole in the thermal bed is designed to accommodate an external light source if necessary. The four holes near the corners of the card guide the positioning, alignment, and assembly of the fluid chamber, which is constructed from multiple layers of acrylic sheeting placed on top of the card. The green pads on the right side are for attaching a connector. If a jumper cable shorts the connector, the current flows only through the top part. If the connector is open, the current flows through both parts, allowing us to adjust the system’s rate of temperature increase by changing the connector’s state.

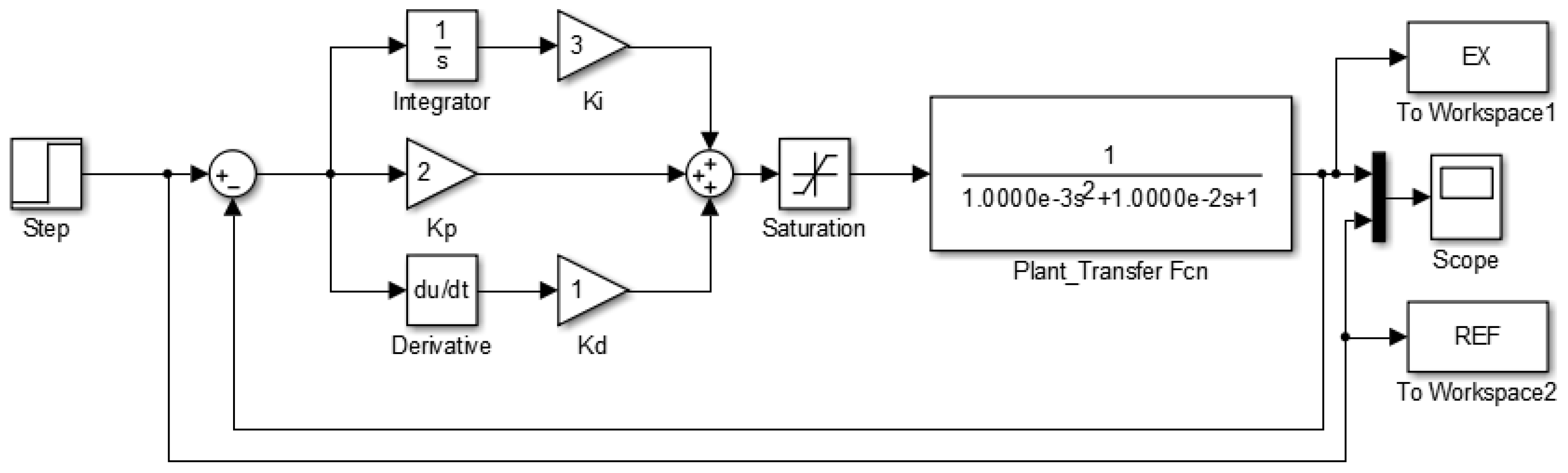

Technological advances in processors and reconfigurable systems enable the implementation of control algorithms that stabilize the system temperature. Classic and modified Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) temperature control systems are used due to their reliability and adaptability in maintaining a stable reference temperature state [

41,

42,

43]. A PID controller was incorporated to control the system temperature. The PID control is a feedback control system in which the variables corresponding to the stages are proposed as proportional, integral, and derivative, as necessary for this experiment. This control system was programmed through the configuration of registers and libraries of the dsPIC microprocessor. Sensor readings are processed and converted to appropriate values for microprocessor input. The control system’s output is scaled, providing a multiplier factor for the register that controls the PWM duty cycle. This control system is active from the start of the process until DNA amplification is complete, at which point the output commands deactivate.

Figure 8 illustrates the block diagram of the second-order control system implemented, including the closed-loop feedback cycle and the proportional, integral, and derivative parameters. The saturation element represents the maximum output, limited to

PWM by the microprocessor program. The system continuously compares with a unit step input signal, using

as reference. For different process temperatures, only minor programming adjustments are needed.

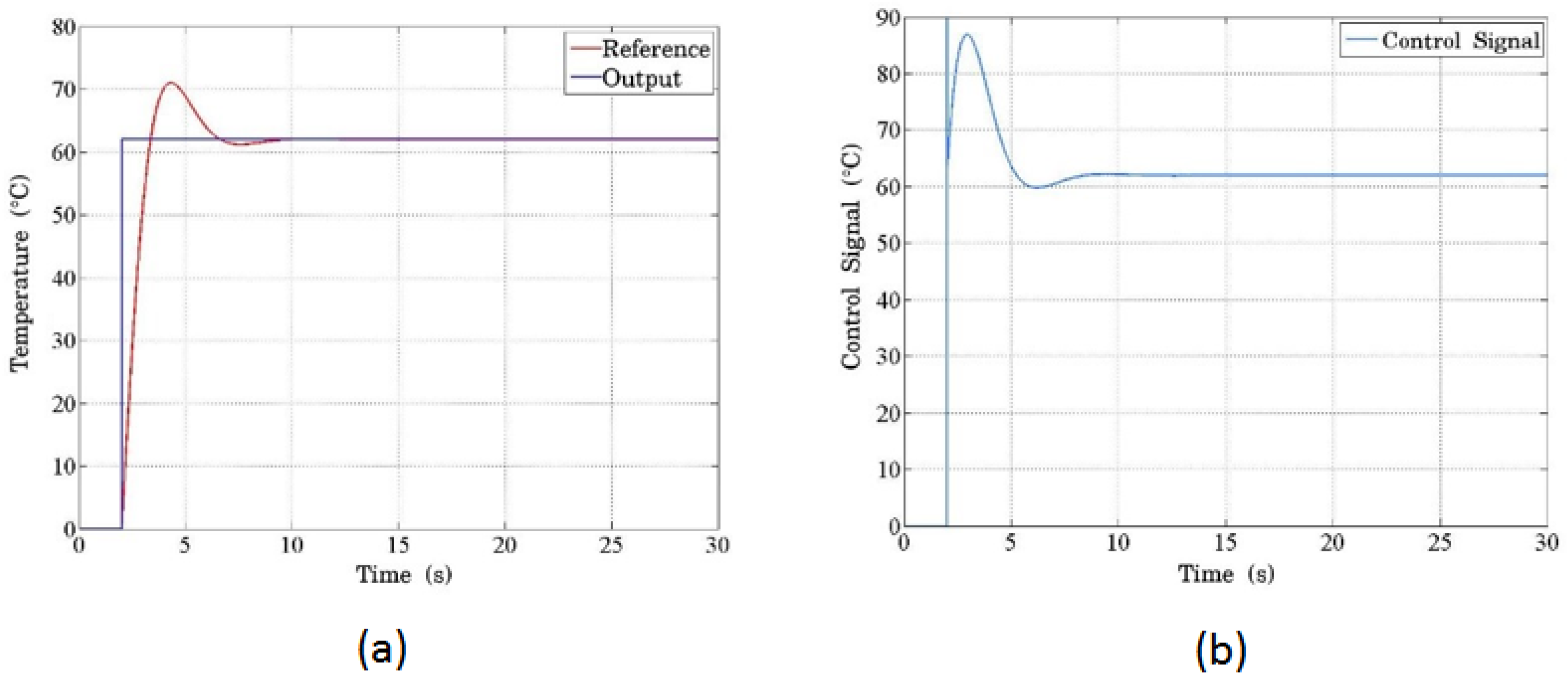

Figure 9 shows the system response considering the target temperature as a step input of 62 °C. In

Figure 9(a), we present the system response model with respect to temperature. The input signal (blue color) of 62 °C and its response are red. The response shows the overshooting and a small oscillation typical of a second-order system. In this case, the plant is the PCB, whose temperature increases depending on the amount of current that is delivered to it. This current depends on a PWM signal. Each temperature value is assigned a duty cycle value that affects the value. Thus, the PWM signal is uniquely related to the required increase in temperature value. The control signal, scaled to temperature units, is shown in

Figure 9 (b). The initial peak (overshooting) is generated because during this period the proportionality relationship controls the system. The system is trying to compensate for the initial, high, required difference in temperature with an even higher control signal value. This overshot behavior for the signal transitions usually disappears in electronic systems because of their intrinsic nature as low-pass filters..

The measured values by the sensors are processed and converted to acceptable values as input to the microprocessor. The output value of the control system is scaled, providing a multiplier factor for the register that controls the duty cycle of the PWM. This system is active from the start of the process until the amplification system is completed when the cycle deactivates the output commands

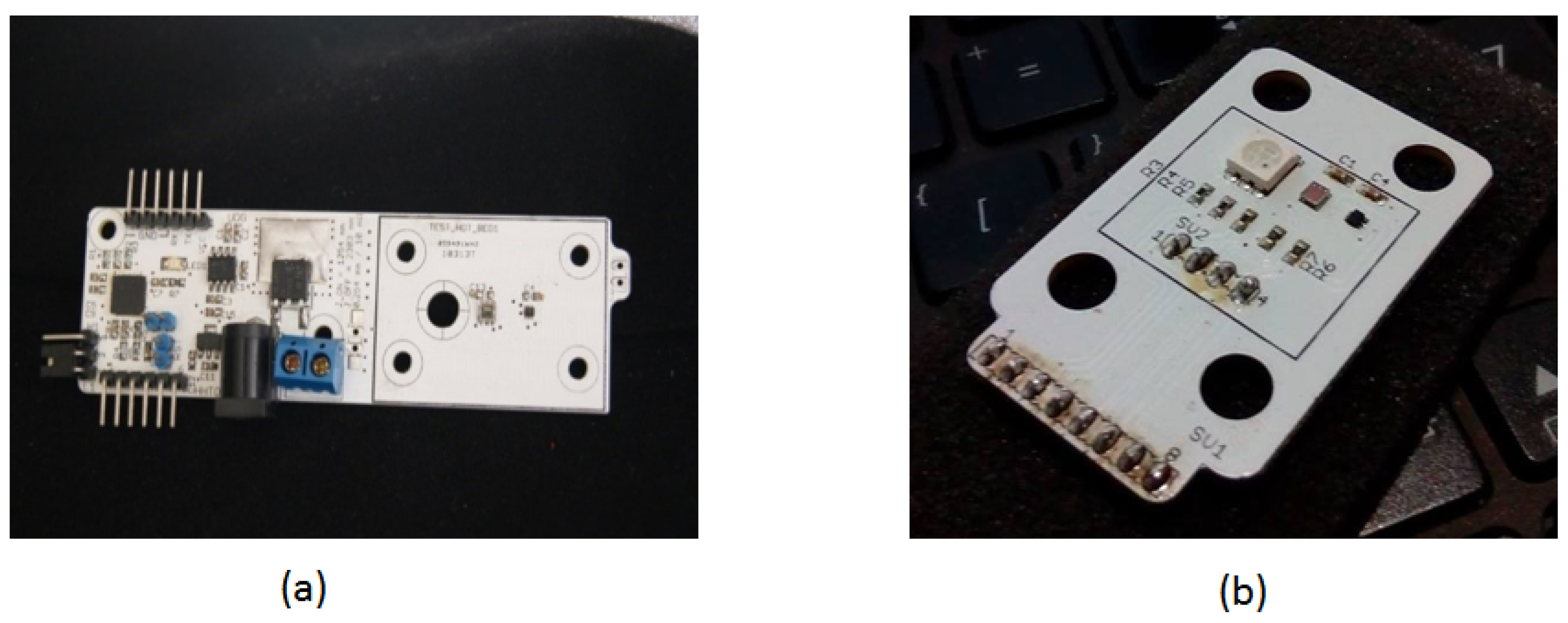

Figure 10 presents a photo of the assembled prototype.

Figure 10(A) shows part of the device that incorporates the control module with a microprocessor to manage sensors and power generation. This sub-assembly controls power delivery to the thermal stage and receives data from the temperature and color sensors. The microprocessor on the left side of the board meets the minimum performance requirements for these control functions.

The dsPIC33FJ128, a 16-bit midrange microprocessor, is shown with connectors at the bottom for ISP programming and top connectors for serial communication, allowing direct connection to a computer or wireless module.

Figure 10(a) also illustrates the power control stage, with an external power source connectable in the center. The microprocessor interfaces with the controller, which manages the gate current of the MOSFET transistor, causing the PCB temperature to increase in the thermal area as current flows through a resistive element.

On the right side of

Figure 10(a), the color and temperature sensors connected to the microprocessor are visible. Only this right portion of the design is shown in

Figure 10(a), as the full schematic is beyond this publication’s scope. The illumination source, an RGB LED, is matched with an RGB color sensor, and includes a temperature sensor to measure the temperature difference between the control base and the fluid layer. This setup helps estimate the temperature and heating time constant of the fluid chamber when heating is applied only to the base.

Figure 10(b) displays the RGB lighting source module for controlling and processing the color and temperature sensors.

Figure 11 shows the PCB layouts for the control assemblies depicted in

Figure 10(a) and 10(b). The design layout highlights the elegance and neatness of the fabricated subsystem, mounted on the prototype’s upper section. The I2C communication protocol connectors are used for sensors and the RGB LED, with one for each color and a shared white connector.