1. Introduction

Large B cell lymphoma (LBCL) represents a heterogeneous group of aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) subtypes, predominantly afflicting adults and characterized by rapid growth of transformed large B cells. Diffuse large B cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (DLBCL NOS) being the most common subtype, accounts for approximately 30% of all NHL cases, with a median age at diagnosis of around 70 years [

1]. The cornerstone of DLBCL treatment has traditionally been rituximab in combination with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), reflecting the standard first-line therapy [

2].With current standard, about 25-35% of patients have primary resistance or relapse post-treatment with even higher rate of treatment failures for patients at higher risk LBCL types, such as high grade B cell lymphoma (HGBL) or DLBCL NOS with aggressive disease features [

3]. A significant number of randomized trials exploring alternative therapeutic approaches have failed to surpass the efficiency of R-CHOP, with a notable exception of Pola-R-CHP regimen incorporating polatuzumab vedotin, which, however, did not solve the problem of relapsed and refractory (r/r) LBCL [

4]. Outcomes for r/r LBCL patients remain dismal, with limited therapeutic options and poor overall survival rates in the era of chemotherapy [

5]. In the second-line setting, autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) following salvage chemotherapy has historically represented a critical therapeutic option. The efficacy of this approach is limited, with approximately 25% patients eligible to intensive chemotherapy achieving prolonged remissions [

6]. Unfortunately, for patients who are not candidates for transplantation or those who fail salvage chemotherapy, the prognosis was even more discouraging [

5]. T cell redirecting therapies is a form of immunotherapy implemented by targeting T lymphocytes to a pre-selected antigen expressed on the surface of tumor cells through genetic modification of T cells or pharmacological effects, holds significant promise in this context. Main types of T cell redirecting therapies currently used in clinical practice are represented by T-cells with chimeric antigen receptors (CAR-T) and bispecific antibodies (BSAs) [

7].

CAR-T is an innovative approach in which T cells are genetically modified ex vivo with a transgene encoding a chimeric receptor [

8]. Chimeric receptors combine in their structure the antigen-binding fragment of immunoglobulin, and the signaling part of the T cell receptor with the domain of immune cells costimulatory receptors. This approach allows CAR-T to recognize the target independently from MHC, and also induce target-specific cytotoxicity without additional activating signals [

8]. Currently, 5 commercial anti-CD19 CAR-T are approved for the treatment of r/r LBCL in 3 and subsequent lines of therapy: tisagenlecleucel (tisa-cel), axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) and lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel) in USA and Europe, actalycabtagene autoleucel (actaly-cel) in India, relmacabtagene autoleucel (relma-cel) in China [

9,

10,

11]. In this group of patients, overall response rates (ORR) with anti-CD19 CAR-T ranged from 53%, to 83% and complete remission (CR) rates ranged from 39% to 83%. Median overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) reported in registration clinical trials was 11,1-25,8 months and 2,9-6,8 months, respectively [

10,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Encouraging results of CAR-T in a group of highly pre-treated patients have led to research into the effectiveness of CAR-T at earlier lines of treatment. Tisa-cel, axi-cel and liso-cel were compared in randomized trials with high-dose chemotherapy followed by ASCT, representing the standard of care for second-line treatment of LBCL. Axi-cel and liso-cell demonstrated a significant benefit in OS and event-free survival (EFS) compared with the control group, which served as the basis for the US and European regulatory approval for the use of these CAR-Ts in the second line therapy of LBCL [

16,

17,

18].

The mechanism of action of BSAs is realized through the binding of one antigen-recognition domain to the target on the surface of the tumor cell, and the other domain to the molecule expressed by the T cell. This interaction leads to the formation of an immune synapse between the malignant cells and the T lymphocytes, inducing T-cell-mediated cytotoxicity independent of T-cell receptor/major histocompatibility complex. Currently, numerous anti-CD3/anti-CD20 BSA are tested in clinical trials for the treatment of LBCL in third or subsequent therapy line lines with glofitamab, epcoritamab, odronextamab and mosunetusumab being most developed to date [

19,

20,

21,

22]. The first three on this list have demonstrated excellent activity in patients with r/r LBCL in corresponding pivotal trials with obrserved ORR ranging 52% to 63% and CR ranging 31% to 39%. At a two-year follow-up, the median OS with odronextamab therapy was 9.2 months, while in the studies with glofitamab and epcoritamab, the median OS was not reached. Median PFS survival was 4,4 months [

19,

20,

23]. Based on results of phase II studies glofitamab and epcoritamab was approved for patients with LBCL who have received two or more lines of therapy, while odronextamab is undergoing regulatory review [

24]. In contrast, mosunetuzumab demonstrate limited efficacy in aggressive B cell lymphomas [

22].

Both types of T cell redirecting therapies have potential to achieve long-term remissions. Analysis of the long-term results of the ZUMA-1 study (median follow-up 63 months) demonstrated that in the total group of patients, 30.3% were characterized by durable remissions that persisted without any maintenance or new anti-lymphoma therapy. Patients who are event-free one or two years after initiation of CAR-T have excellent OS: 90.9% and 92.3%, respectively [

13]. Among patients treated with glofitamab, 78% with a complete response maintained this status after one year of follow-up [

25]. This represents 31% of the patient population treated with glofitamab. However, with both CAR-T and BSAs, CR in approximately half of patients are not sustained. Most relapses occur in the first 12 months after the start of T cell redirecting therapies [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. To prevent relapse in this population of patients, it is necessary to consider consolidation therapy, such as allogeneic HSCT [

26]. Importantly, to date, there are no markers or factors that enable identifying the group of patients with CR who are at high risk of relapse. At the same time, despite the superiority of T cell redirecting therapies for r/r LBCL over chemotherapy, from 17% to 47% still remain refractory [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Therefore, this group of patients may likely require a combination of CAR-T or BSAs with another treatment component. Thus, T cell redirecting therapies should be built into a comprehensive treatment strategy of LBCL, which necessitates stratification factors. Traditional clinical prognostic factors, such as LDH level, bulky disease, ECOG status, extranodal involvement are characterized by limited prognostic value [

27,

28]. Potentially, the tumor microenvironment (TME) may become a new prognostic cluster, helping to better stratify patients and optimize treatment strategies. But the impact of TME composition on the prognosis of patients receiving CAR-T or BSAs remains uncertain. The article provides an overview of the relationships between the structure of TME and its dynamics, the phenotype of tumor cells, and the profile of immune checkpoint inhibitors on the effectiveness of T cell redirecting therapies in patients with r/r LBCL.

2. The Tumor Microenvironment in Large B Cell Lymphoma

The tumor microenvironment plays a critical role in the pathology and treatment responses of LBCL. Because of LBCL type heterogeneity, specific cellular composition varies widely, hampering the studies of the microenvironment. In most LBCL cases, malignant B cells disrupt the normal tissue architecture, leaving only a limited presence of TME cells including macrophages, T-cells, NK cells and stromal cells [

29]. Within the TME, immune cells may carry inhibitory receptors like programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1), lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG3), and T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing 3 (TIM3) [

30]. While these receptors can suppress anti-tumor immune activity supporting survival of cancer cells, they also represent important markers for processes of T-cell activation and exhaustion. Prognostic relevance of certain TME characteristics, like the level of immune infiltration and functional state T cells, the density and polarization of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) was demonstrated for first line treatment across different types of LBCL [

31,

32,

33,

34]. Several recent studies showed that “hot” tumors, specifically those with increased T-cell proportion and expressing PD1 and TIM3, were associated with an improved prognosis for DLBCL patients after rituximab based chemotherapy, while “cold” DLBCL cases with a depleted TME were associated with significantly worse outcomes [

35]. The relevance of described TME characteristics for the efficacy of different types of T cell redirecting therapies is an area of active research.

This review focuses on the reports of the TME components and their respective prognostic significance for T-cell redirecting therapies. Such components include:

Tumor cells characteristics

Immune cells populations

Immune checkpoints profile

Cytokines and chemokines

Stromal Components and adhesion molecules

Importantly, the more extensive clinical experience with CAR-T therapy may provide valuable insights that are crucial for understanding the mechanisms of response and resistance in treatments involving bispecific antibodies with potential to refine current therapeutic strategies and introduce new treatment modalities.

3. Cell Populations within the TME

3.1. Tumor Cells

Although LBCLs are often grouped as a single entity, they exhibit significant heterogeneity in phenotypic characteristics, pathogenesis mechanisms, and mutational landscapes, which may influence their responses to immunotherapy.

Histological subtype. Pivotal studies of CAR-T therapy did not identify LBCL subtype as a significant factor influencing outcomes. However, real-world data suggest that primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL) and transformed follicular lymphoma (tFL) may exhibit more favorable responses to CAR-T therapy [

27,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. It was also demonstrated that patients with a higher “FL-like” gene expression score had higher complete response rates and longer progression-free survival in liso-cel therapy [

42]. Similarly, when using BSAs, the LBCL subtype was also not identified as a determinant of prognosis [

19,

20,

21,

43].

Cell of origin (COO). For standard chemoimmunotherapy, the cell of origin (COO) of DLBCL holds known prognostic significance. Lymphomas derived from germline B cells (GCB subtype) have a better prognosis than those derived from activated B cells (ABC subtype) when treated with R-CHOP chemotherapy [

44]. However, T-cell redirecting therapies appear to negate the impact of COO on patient outcomes. [

19,

20,

28,

36,

37,

39,

42,

43,

45,

46].

Double hit\triple hit lymphomas. Contrary to standard chemotherapy, where BCL2 and MYC rearrangements predict a poor prognosis, T cell redirecting therapies have been effective in managing these traditionally unfavorable phenotypes. As shown in a series of reports, neither double-expressor variant of LBCL nor double/triple-hit lymphoma were a prognostic factor among patients receiving CAR-T or BSAs [

19,

27,

37,

42,

45].

Target antigen expression. The role of target antigen expression levels on malignant B cells remains unresolved. The density of the target on the surface of B cells varies. The expression level of CD20 in patients with DLBCL is higher and less variable than CD19 according to immunohistochemical and molecular genetic studies [

47,

48]. JULIET study showed that for tisagenlecleucel treatment, baseline CD19 expression levels assessed by immunohistochemistry did not correlate with response outcomes. Moreover, the ORR was comparable between patients with clearly CD19 positive LBCL and CD19 negative or low expression lymphoma [

37]. However, in two cases where lack of CD19 expression was observed, responses were not achieved. In ZUMA-1 study similar response rates on axi-cel were observed in patients with CD19-negative disease and those who had CD19-positivity according to immunohistochemistry [

39,

49]. In addition to immunohistochemistry, transcriptomic analysis of CD19 expression by RNA-seq in patients did not also demonstrate impact on both PFS and OS across the overall study population. But it is worth noting that 6 of 8 CD19 negative patients who initially responded to axi-cel subsequently had disease progression [

49]. In contrast, in ZUMA-7 EFS after axi-cel was better in patients with high (>median) CD19 gene and protein expression, assessed by immunohistochemistry or gene signatures analysis, compared with patients with lower expression [

50]. In liso-cel study levels CD19 gene expression before CAR-T were comparable between patients with ongoing CR at 3 months and progression disease [

42].

In studies of the effectiveness of BSAs glofitamab, mozunetuzumab and odronextamab, no significant association was found between the level of CD20 expression by immunohistochemistry on tumor cells and ORR. But researchers still pay attention to the fact that patients with extremely low or negative CD20 expression tend to fail to achieve a response to BSAs [

43,

45,

47,

51].

In vitro experiments have shown that CAR T cells are able to eliminate malignant cells that express <100 CD19 molecules on their surface. This number is below the detection limit of immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry [

47,

52]. Taken together, these data suggest that, in general, the level of expression of neither CD19 nor CD20 on B cells beyond a certain threshold influences ORR and clinical outcomes. However, in situations where expression of the target is absent or extremely low, although such cases are rare in the patient population, T cell redirecting therapies has little effect and predominantly results in lack of response or early progression. The discrepancy in the results of the trials may be explained by cases of false CD19 negativity, when the expression level of this marker is below the detection limit of the methods used in clinical practice. Still there have been demonstrated cases of sustained CR in patients with confirmed CD19 negative lymphomas [

49]. In such cases the achievement of an antitumor effect may be mediated by mechanisms other than CD19 antigen-dependent cytotoxicity, such as “bystander effect” [

37,

42,

49].

Antigen loss can be considered the ultimate adaptation of a cancer cell to targeted immunotherapy. At relapse after anti-CD19 or anti-CD20 T-cell redirecting therapies, approximately 30% of patients experience target loss. This highlights the higher evolutionary pressure exerted by CAR-T and BSAs compared to naked monoclonal antibodies, where loss of antigen is casuistically rare. In cases of target-positive relapses, other mechanisms come to the fore, with the important role attributed to the influence of TME components [

53].

3.2. Tumor-Infiltrating T Cells

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) are a population of T cells, heterogeneous in phenotype and function, forming part of the tumor microenvironment both in the primary and in metastatic sites [

54]. In most studies, elevated levels of CD3+ TILs had an impact on response and prognosis of patients treated by anti-CD19 CAR-T. This highlights the importance of environment permissiveness for T cell infiltration and contribution of not only genetically modified T lymphocytes to the antitumor response [

46,

55,

56,

57]. High values of Immunoscore index, which assess the abundance of CD3+ and CD8+ TILs subsets at various tumor loci, and Immunosign 21, which assesses the expression of set of genes associated in particular with T cells (

CD3D, CD3E, CD3G, CD8A, GZMA, GZMB, GZMK, GZMM) were significantly correlated with OS in patients with LBCL treated by axi-cel [

56,

57]. The independent influence of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells numbers is unclear. The different methods for determining T cell subsets among studies are also a definite barrier to identifying their prognostic value. Generally, the density of CD8+ TILs in pre-treatment biopsies had either a neutral or beneficial effect on ORR to CAR-T. While, the number of CD8+ TILs with PD1+ or PD1+ LAG3 +/- TIM3- or CD73+ was significantly associated with achieving response or its durations in patients treated by axi-cel or lisa-cel, but not tisa-cel [

57,

58,

59,

60]. Data on the prognostic value of CD4 TILs are even more limited. It was shown that the number of T helpers in pre-treatment biopsies did not affect the OS during axi-cel treatment [

57]. Patients with persisting response at month 3 after liso-cel had a higher percentage of CD4+ TILs cells in tumor samples [

60].

In BSAs therapy, similarly, enrichment of TME by TILs creates the prerequisites for achieving remissions. A trend for the higher number of CD3+ and CD8+, but not CD4+ TILs in lymphoma biopsies before initiation of odronextamab was observed in patients with response in ELM-1 trial, but none of these effects reached significance. Surprisingly, enrichment of the Treg in TME was associated with response to treatment with odronextamab. Patients who achieved CR to glofitamab also showed a trend towards a higher percentage of CD8+ T cells infiltration in TME [

45,

47]. In the case of mosunetuzumab, a positive association was confirmed between signature of CD4+ follicular T helpers genes and response rates in patients with tFL but not for DLBCL [

61].

3.3. Tumor-Associated Macrophages

It is known that the role of TAMs in the microenvironment is ambivalent and is largely determined by their polarization. M1 polarization of TAMs is induced by Th1 cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-a, IL-1b). M1 TAMs provide a pro-inflammatory environment, secrete immunostimulatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, IL-12 IL-18, IL-23) and antiangiogenic factors, present antigens and support the antitumor response. On the contrary, M2 TAM are characterized by an anti-inflammatory functional phenotype, produce immunosuppressive cytokines (IL-10, IL-4, IL-13, TGF-β) and angiogenesis factors, inhibit the antitumor response, cause T-cell dysfunction, promote the growth and proliferation of tumor cells [

62,

63].

Typically, CD68 and/or CD163 are used for designation TAMs in studies, but these markers do not reflect functional polarization. Only a few studies assessed not only TAMs population as a whole, but also the aspects of their polarization. A number of authors have demonstrated that TAMs density is associated with refractoriness to anti-CD19 CAR-T therapy. Patients with higher levels of CD68 and/or CD163 positive cells in tumor biopsies had shorter duration of response to axi-cel and lisa-cel [

36,

57,

59]. When using relma-cel, the depth of the response was also determined by the number of TAMs [

55]. The negative role of M2 TAMs was also confirmed. In patients who relapsed after axi-cel, initial tumor biopsies were enriched by M2 TAMs [

64].

In the context of BSAs, information on the prognostic value of TAMs is limited. J. Brouwer-Visser et al. demonstrated that the density of CD68+ TAMs did not differ between responders and non-responders to odronextamab [

47].

3.4. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells

MDSCs are a heterogeneous population of cells with potent immunosuppressive activity. The source for MDSCs are cells of the monocytic or granulocytic lineage. If MDSCs are formed from granulocytes, they are called granulocytic/polymorphonuclear MDSCs (PMN-MDSCs), and if from monocytes, then monocytic MDSCs (M-MDSCs). The main parameter defining MDSCs is their ability to inhibit T cell and B cell immune responses through the secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines, a number of enzymes, and the expression of ligands for immune checkpoint receptors [

65,

66].

The data from ZUMA-1 trial shows that the density of M-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs in the TME did not differ significantly between complete responders and patients with other types of response to axi-cel [

57,

67]. The impact of MDSCs TME on the outcomes of patients with LBCL treated by BSAs remains an unexplored issue and requires further research.

3.5. Kinetics of Microenvironment Composition during T Cell Redirecting Therapies

TME remodeling during T cell redirecting therapy affects TILs and other cell populations. As has been shown by a number of studies, density of TILs after CAR-T or BSAs increases [

42,

68,4755]. It was mainly shown that CD3+ TILs are predominantly enriched by CD8+ T cells. There is insufficient data regarding the dynamics of changes in other T-cell subpopulations. Notably, the proportion of CAR-positive T cells varies from 1 to 22% of TILs in the TME. This again emphasizes the versatility of the mechanisms of the antitumor response induced by CAR-T. In patients treated by axi-cel, durable response was associated with a significant increase of cytotoxic T cell subset, CD4+ naive T cells, T helper 2 in post-infusion biopsies. In liso-cel trial patients achieved objective response trended to have a larger increase in CD8+ cells in tumors as compared to patients achieving SD or PD [

42,

47,

55,

57,

60,

64,

68].

Changes occurring in other cell populations in the TME, during T cell redirecting therapy with the exception of the TILs, are practically absent. It has been demonstrated that the density of TAMs increases after CAR-T therapy. But the available data on the relationship between the dynamics of changes in TAM and the clinical effect are contradictory. It is also noted that patients who had a relapse after CAR-T are characterized by an increase in the number of M-MDSCs in post-treatments biopsies [

42,

55,

57,

60,

64,

68].

4. Immune Checkpoints in the TME

The immune checkpoint family include more than two dozen members, with notable examples of PD-1, CTLA-4, LAG3, TIM3, TIGIT playing a pivotal role in modulating the immune tolerance and CD28, ICOS, 4-1BB (CD137), CD40 considered as activators of immune response, making them and their corresponding ligands a particularly interesting candidates for identification as markers for the success of T-cell redirecting therapies [

69].

Due to the clinical importance of PD-1, LAG3 and TIM3, most of the studies addressed the prognostic significance of these markers on response and prognosis of patients treated with CAR-T. Using imunofluorescence panels and gene expression profiles, higher baseline presence of PD-1+ T cells was significantly associated with early CR versus patients who had progression at first month after CAR-T infusion in liso-cel TRANSCEND NHL-001 trial [

59]. However only a trend was shown for this factor in later report for the same cohort [

42]. The comprehensive study of pretreatment TME profile of patients treated with axi-cel included a differentiated approach to analyze the isolated or simultaneous expression of immune checkpoints PD-1, LAG3, and TIM3 on CD8+ T cells. The density of CD8+ T cells with activated phenotype (PD-1+ and LAG3+/−, TIM3−) was most significantly associated with objective response, contrasting with non-activated (no checkpoint expression) or exhausted phenotype (PD-1+LAG-3+TIM-3+) [

57]. In a limited cohort of patients treated with relma-cel, the CR group demonstrated significantly higher relative mRNA expression of

LAG3 and

CTLA4 in pretreatment tumor biopsies [

55]. For tisa-cel quantitative immunofluorescence analysis was performed on preinfusion tumor tissues demonstrating no significant differences between the best overall response groups in the percentage of total cells expressing PD-1, LAG3, or TIM3 and percentage of total CD3 T cells expressing these markers at baseline. However patients with the highest percentages of LAG3+ T cells (among total T cells) did not have a response to tisagenlecleucel or had a relapse within 6 months [

37].

The inhibitory immune checkpoint ligands expression profile in patients treated with CAR-T is less described. The percentages of malignant B cells (defined as CD19+ and/or CD20+) in pre-infusion biopsy that were also positive for PD-L1 or MHC II were higher in patients with no durable response to axi-cel compared with durable response defined as remission with a minimum follow-up of 6 months after infusion [

36]. A subset of CD163+ macrophages, those that were IDO1+ or PD-L1+, appeared to be higher in the pre infusion samples of patients with no response to lisa-cel [

42]. For tisa-cel, no significant influence was shown for the percentage of total cells expressing PD-L1 in pre-infusion biopsies of best response. However, the 5 patients with the highest PD-1–PD-L1 interaction scores either did not have a response to tisa-cel or had an early relapse [

37].

Several studies addressed the influence of activating immune checkpoints expression. Some of the strongest individual genes with higher expression in pre-infusion of liso-cel samples of patients in month-3 CR included

ICOS,

CD28, CD40LG and

KLRB1 in TRANSCEND NHL 001 cohort [

42]. The relative expression of costimulatory molecules mRNA (ICOS and 4-1BB) were significantly higher for the CR patients in relma-cel trial [

55].

The assessment of TME dynamics after CAR-T infusion showed the significant shift in immune checkpoint expression profile and its association with response. Multiplex immunohistochemistry in axi-cel cohort post-infusion showed that durable responses were associated with a significant increase in PD1+TIM3+LAG3- cytotoxic T cell densities [

64]. Significant transcriptomics changes in tumor biopsies from pre-treatment to 2 weeks after axi-cel with upregulation of immune checkpoint encoding genes, (CD274, CD276 and CTLA-4) was also associated with response to therapy [

57].

The data regarding the role of immune checkpoints in the tumor microenvironment for bispecific antibody therapies is rather scarce. The expression of PD-1 and LAG-3 on CD8 T cells within baseline tumor biopsies of patients with DLBCL was assessed using immunoflorescence in ELM-1 cohort of patients treated with odronextamab. While the proportion of CD8 T cells that expressed PD-1 and/or LAG-3 was numerically higher among patients with response, this difference was not statistically significant [

47]. A gene expression signature analysis of baseline tumor samples of patients received glofitamab treatment demonstrated a significantly lower PD-1-high T-cell signatures in complete responders versus patients with progression of disease [

45].

A notable, yet unexpected observation in patients treated with odronextamab was the significantly higher density of PD-L1+ cells within baseline tumor biopsies among responders compared to non-responders. Moreover, an increase in PD-L1+ cells from baseline to Week 5 was noted across patients with DLBCL, suggesting that PD-L1 expression may be an adaptive increase in interferon signaling as response of the tumor to immune engagement by the therapy [

47].

To sum up, studies on immune checkpoint expression in T-cell redirecting therapy highlight the complexity of interpreting these markers, which can indicate either T-cell activation or exhaustion depending on their co-expression and TME context. For example, PD1 expression is not only restricted to dysfunctional T cells, and further studies should assess this marker in complex with additional parameters, such as cell type, co-expression with other IC’s, and with consideration of a spatial composition of the tumor, a question which was not addressed in most reports to date. Responses to treatment with CAR-T were associated with a tumor microenvironment that promotes T-cell activation, supported by elevated levels of costimulatory molecules such as ICOS and 4-1BB. The data regarding these characteristics for BSAs is lacking. The expression inhibitory ligands, particularly PD-L1 either by tumor or TME macrophages demonstrated negative influence on response and prognosis for patients treated with CAR-T. The difference in prognostic significance of high PD-L1 density observed in patients treated with odronextamab is intriguing as it may indicate distinct mechanisms of resistance in patients treated with BSAs, but should be confirmed in other cohorts in future studies.

5. Stromal Components, Adhesion Factors and Cytokines

Studies of the stromal components and their prognostic role in T cell redirecting therapies are limited, especially those utilizing immunohistochemistry. Most studies have instead focused on stromal gene expression as a part of comprehensive gene expression profiling. Gene expression profiles from biopsy samples of patients with relapsed/refractory LBCL from ZUMA-7 trial identified cluster enriched by stroma, myeloid and endothelial cells,

NOS2,

TGF-β,

B7-H3,

ARG1 and hypoxia. Notably, this cluster correlated negatively with event-free survival of patients undergoing treatment with axi-cel [

50].

Previously G. Lenz et al. analyzed biopsy samples from untreated patients with DLBCL. Their gene expression profiling revealed two distinct gene signatures unrelated to malignant cells. The "stromal 1" gene signature was enriched in genes encoding extracellular matrix proteins (fibronectin, osteonectin, collagens, laminins) or enzymes involved in the synthesis and remodeling of matrix components (collagen synthesis modifiers, metalloproteases, connective tissue growth factor) and the antiangiogenic factor thrombospondin. This cluster was positively associated with survival after CHOP or R-CHOP therapy. The “stromal 2” gene signature had the opposite effect on the prognosis. This cluster included genes for endothelial cells and angiogenesis regulators [

44]. Building on these findings, subsequent gene expression profiling of baseline tumor biopsies from patients treated with liso-cel, using the gene sets identified by Lenz et al., demonstrated that patients who maintained a complete response at 3 months post-CAR-T infusion exhibited a strong expression of the "stromal 1" gene signature [

42].

In the relma-cel study, gene expression of tumor-associated fibroblasts (

AP,

TNC,

CSPG4,

PDGFRA,

S100A4,

ASPN,

STC1,

ITGAM) was higher in the patients with PR than with CR [

55].

As described above the enrichment of T cells is beneficial, as is enrichment of the TME during and after T cell redirecting therapies. The capacity of the TME to support T-cell infiltration is influenced by the endothelial state, extracellular matrix architecture and the profile of chemokines and cytokines, facilitating lymphocyte access and migration to tumor loci. The analysis of biopsies of patients treated with relma-cel demonstrates that in patients with complete response to CAR-T, CD3+ T cells were distributed within the tumor, whereas in partial responders, characterized by high levels of tumor-associated macrophages, T cells were largely excluded from tumor loci [

55]. However, the studies of the mechanisms of this trafficking was limited to the analysis of gene expression profiles in different panels. Based ot the RNA sequencing of biopsy samples of patients before the relma-cel infusion, in complete responders, the expression of cytokines genes

CCL2,

CCL3,

CCL4,

CCL5,

CXCL8,

CXCL9,

CXCL10,

CXCL11,

CXCL12,

CXCL16,

IL-10 and

TGF-β were lower compared with patients who achieved only partial response. Same study demonstrated that the expression genes of

CCR6,

CCR10,

CXCR3, and

CXCR4 were increased in patients with CR [

55]. In tumor samples

IL-8 gene expression was elevated in patients who failed to respond or relapsed after axi-cel [

67].

Mutations in the gene or loss expression of adhesion protein CD58 (ligand of CD2) in tumor cells was an unfavorable prognostic factor. Patients with LBCL with aberrations in CD58 had lower PFS during CAR-T therapy by axi-cel [

70,

71].

Thus, the available information on the prognostic influence of stromal components, the profile of cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules on the effectiveness of CAR-T is extremely limited. Regarding BSAs, we did not find relevant information assessing the impact of these factors on therapy and patient prognosis. While gene expression profiling provides valuable insights, it only partially addresses the complexity of T-cell migration and interaction with a tumor. Critical aspects such as properties of endothelial barrier, spatial assessment of chemokine gradients, and the physical and mechanical properties of the matrix, remain unexplored. These factors are crucial for understanding the full spectrum of mechanisms governing T-cell trafficking from the bloodstream into the tumor microenvironment, suggesting a significant gap in our current methodological approaches and emphasizing the need for comprehensive studies that would expand our understanding of T-cell redirecting therapies.

6. Challenges and Opportunities

The significant limitation of current analysis is the limited number of patient data and cohorts available. Data predominantly come from registrational trials like ZUMA-1 and ZUMA-7 for axi-cel, TRANSCEND NHL-001 for liso-cel, JULIET pivotal trial for tisa-cel, and small relma-cel cohort. Moreover, the same patient populations often underpin multiple reports published at different times, which might lead to overlapping or contradictory findings. The dataset is even more limited for BSAs. Furthermore, the methodologies employed in these studies vary significantly, most encompassing bulk gene expression profiling and immunofluorescence utilizing diverse marker panels. This variability complicates the comparison of results across different studies and can lead to contradictory findings. Another significant limitation is the focus of most studies on immediate response metrics like complete response or partial response, and objective response rate, with less emphasis on long-term outcomes such as progression-free survival and even less reporting the influence on overall survival.

The analysis revealed several research gaps which may be addressed to advance the field of T-cell redirecting therapies for LBCL, as well as some insights from CAR-T studies providing valuable perspectives for BSAs. These include a more comprehensive analysis of immune cell density and composition, particularly in BSA treatments, to understand not just the quantity but also the functional state of cells like macrophages and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. This may imply the use of standardized panels like Immunoscore and Immunosign21. The role of macrophage polarization (M1 vs. M2) in prognosis and therapy outcomes also needs more exploration. Future studies should assess polarization states to better understand their impact on therapy efficacy. Moreover, there is a need for an expansion of immune checkpoint analysis to evaluate comprehensive profiles that include activating checkpoints in BSAs as they showed to be significant in CAR-T cohorts. Besides assessing isolated markers, studies should evaluate comprehensive profiles enabling distinction between activated and exhausted T cells. The immune checkpoint ligands studies need to expand beyond PD-L1 for a more nuanced understanding of TME immune interactions. Techniques such as immunofluorescence or immunohistochemistry are needed to explore the spatial characteristics of tumor architecture and checkpoint distribution. The prognostic value of stromal gene expressions, such as those associated with the extracellular matrix, also remains underexplored in both CAR-T and BSA contexts. A deeper understanding of these elements could reveal new therapeutic targets and prognostic markers. Finally, integrating advanced technologies like genomic, proteomic, and imaging technologies could enhance the accuracy of TME assessments. This comprehensive approach would help to fill the significant gaps in our current methodological approaches and improve the effectiveness of T-cell redirecting therapies in LBCL.

7. Conclusions

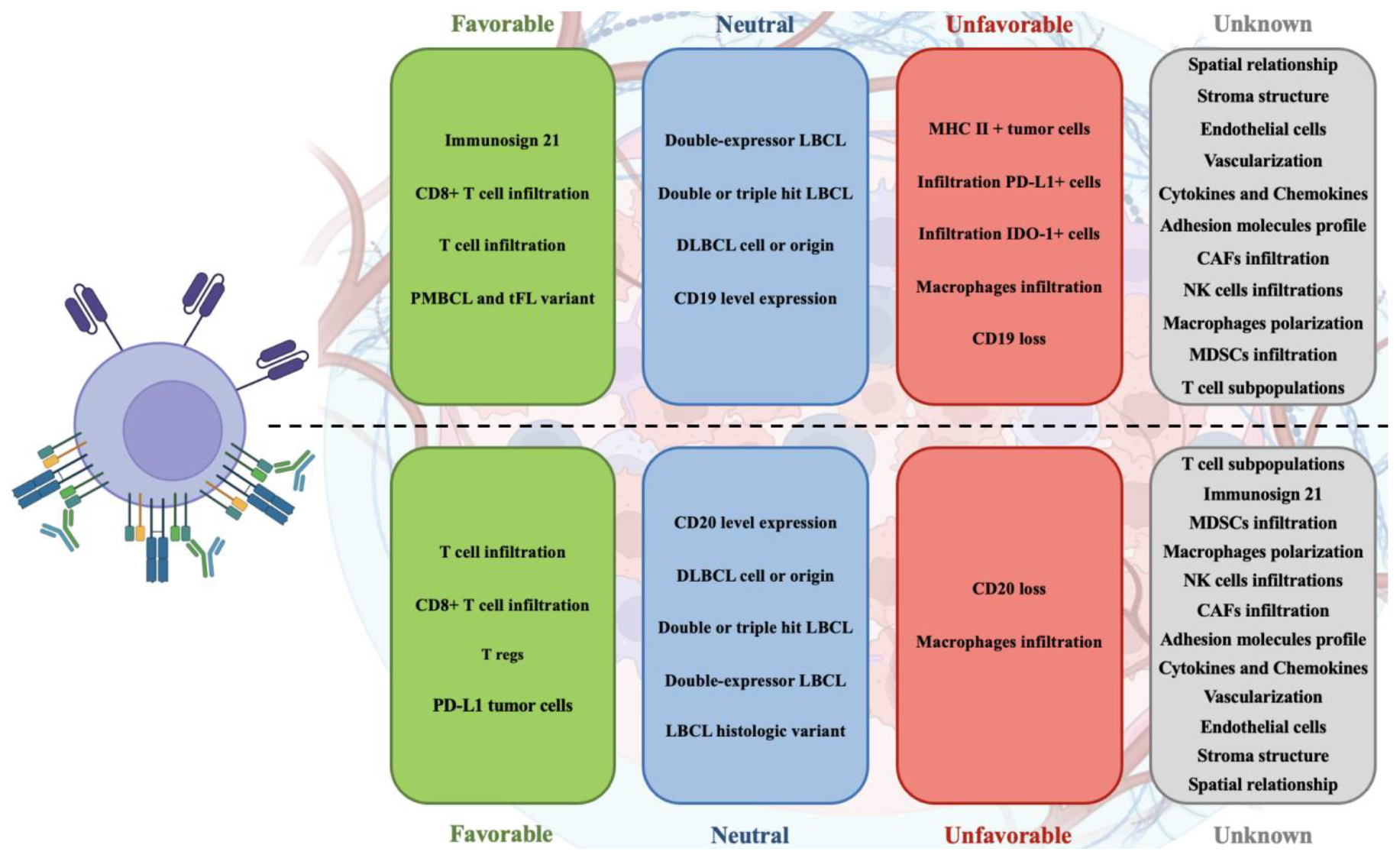

The role of the tumor microenvironment in T-cell redirecting therapies such as CAR-T and bispecific antibodies has proven pivotal yet complex, underscoring a nuanced interplay between tumor biology and therapeutic efficacy in large B-cell lymphoma. As illustrated on

Figure 1, the variability in TME composition—ranging from immune cells to stromal elements—critically influences patient outcomes, highlighting a significant area for deeper investigation. The existing literature, primarily from a limited number of trials and using diverse methodologies, provides a foundational understanding but also indicates substantial gaps in comprehensively mapping TME dynamics and its therapeutic implications. Future research should aim to standardize assessment methods and expand studies to include a broader range of TME components, which may unveil new prognostic markers and therapeutic targets. Ultimately, advancing our grasp of the TME's role will enhance the strategic development of T-cell therapies, potentially leading to more robust and sustained responses in LBCL patients.

Funding

This research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation research grant (project number 22-75-00117).

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to the resource biorender.com for the opportunity to create the picture.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Sehn LH, Salles G. Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(9):842-858. [CrossRef]

- Candelaria M, Dueñas-Gonzalez A. Rituximab in combination with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Ther Adv Hematol. 2021;12:2040620721989579. Published January 30, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Olszewski AJ, Kurt H, Evens AM. Defining and treating high-grade B-cell lymphoma, NOS. Blood. 2022;140(9):943-954. [CrossRef]

- Tilly H, Morschhauser F, Sehn LH, et al. Polatuzumab Vedotin in Previously Untreated Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(4):351-363. [CrossRef]

- Crump M, Neelapu SS, Farooq U, et al. Outcomes in refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results from the international SCHOLAR-1 study. Blood. 2017;130(16):1800-1808. Correction appears in Blood. 2018;131(5):587-588. 10.1182/blood-2017-11-817775. [CrossRef]

- Wullenkord R, Berning P, Niemann AL, et al. The role of autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in aggressive B-cell lymphomas: real-world data from a retrospective single-center analysis. Ann Hematol. 2021;100(11):2733-2744. [CrossRef]

- Russler-Germain DA, Ghobadi A. T-cell redirecting therapies for B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: recent progress and future directions. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1168622. Published July 3, 2023. [CrossRef]

- June CH, Sadelain M. Chimeric Antigen Receptor Therapy. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(1):64-73. [CrossRef]

- Cappell KM, Kochenderfer JN. Long-term outcomes following CAR T cell therapy: what we know so far. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20(6):359-371. [CrossRef]

- Ying Z, Yang H, Guo Y, et al. Relmacabtagene autoleucel (relma-cel) CD19 CAR-T therapy for adults with heavily pretreated relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma in China. Cancer Med. 2021;10(3):999-1011. [CrossRef]

- https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2024/nexcar19-car-t-cell-therapy-india-nci-collaboration.

- Schuster SJ, Tam CS, Borchmann P, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of tisagenlecleucel in patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell lymphomas (JULIET): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(10):1403-1415. [CrossRef]

- Neelapu SS, Jacobson CA, Ghobadi A, et al. Five-year follow-up of ZUMA-1 supports the curative potential of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2023;141(19):2307-2315. [CrossRef]

- Abramson JS, Palomba ML, Gordon LI, et al. Two-year follow-up of lisocabtagene maraleucel in relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma in TRANSCEND NHL 001. Blood. 2024;143(5):404-416. [CrossRef]

- Jain H, Karulkar A, Kalra D, et al. High Efficacy and Excellent Safety Profile of Actalycabtagene Autoleucel, a Humanized CD19 CAR-T Product in r/r B-Cell Malignancies: A Phase II Pivotal Trial. Blood. 2023;142:4838-4838. [CrossRef]

- Locke FL, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel as Second-Line Therapy for Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(7):640-654. [CrossRef]

- Bishop MR, Dickinson M, Purtill D, et al. Second-Line Tisagenlecleucel or Standard Care in Aggressive B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(7):629-639. [CrossRef]

- Abramson JS, Solomon SR, Arnason J, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel as second-line therapy for large B-cell lymphoma: primary analysis of the phase 3 TRANSFORM study. Blood. 2023;141(14):1675-1684. [CrossRef]

- Dickinson MJ, Carlo-Stella C, Morschhauser F, et al. Glofitamab for Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(24):2220-2231. [CrossRef]

- Thieblemont C, Phillips T, Ghesquieres H, et al. Epcoritamab, a Novel, Subcutaneous CD3xCD20 Bispecific T-Cell-Engaging Antibody, in Relapsed or Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma: Dose Expansion in a Phase I/II Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(12):2238-2247. [CrossRef]

- Bannerji R, Arnason JE, Advani RH, et al. Odronextamab, a human CD20×CD3 bispecific antibody in patients with CD20-positive B-cell malignancies (ELM-1): results from the relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma cohort in a single-arm, multicentre, phase 1 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9(5). [CrossRef]

- Budde LE, Assouline S, Sehn LH, et al. Single-Agent Mosunetuzumab Shows Durable Complete Responses in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory B-Cell Lymphomas: Phase I Dose-Escalation Study. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(5):481-491. [CrossRef]

- Ayyappan S, Kim W, Kim T, et al. Final Analysis of the Phase 2 ELM-2 Study: Odronextamab in Patients with Relapsed/Refractory (R/R) Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL). Blood. 2023;142:436-436. [CrossRef]

- Trabolsi A, Arumov A, Schatz JH. Bispecific antibodies and CAR-T cells: dueling immunotherapies for large B-cell lymphomas. Blood Cancer J. 2024;14(1):27. Published February 8, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hutchings M, Carlo-Stella C, Morschhauser F, et al. Relapse Is Uncommon in Patients with Large B-Cell Lymphoma Who Are in Complete Remission at the End of Fixed-Course Glofitamab Treatment. Blood. 2022;140:1062-1064. [CrossRef]

- Zurko J, Ramdial J, Shadman M, et al. Allogeneic transplant following CAR T-cell therapy for large B-cell lymphoma. Haematologica. 2023;108(1):98-109. Published January 1, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Vercellino L, Di Blasi R, Kanoun S, et al. Predictive factors of early progression after CAR T-cell therapy in relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2020;4(22):5607-5615. [CrossRef]

- Birtas Atesoglu E, Gulbas Z, Uzay A, et al. Glofitamab in relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Real-world data. Hematol Oncol. 2023;41(4):663-673. [CrossRef]

- Scott DW, Gascoyne RD. The tumour microenvironment in B cell lymphomas. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(8):517-534. [CrossRef]

- Chen BJ, Dashnamoorthy R, Galera P, et al. The immune checkpoint molecules PD-1, PD-L1, TIM-3, and LAG-3 in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Oncotarget. 2019;10(21):2030-2040. Published March 12, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Keane C, Gill D, Vari F, et al. CD4(+) tumor infiltrating lymphocytes are prognostic and independent of R-IPI in patients with DLBCL receiving R-CHOP chemo-immunotherapy. Am J Hematol. 2013;88(4):273-276. [CrossRef]

- Coutinho R, Clear AJ, Mazzola E, et al. Revisiting the immune microenvironment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma using a tissue microarray and immunohistochemistry: robust semi-automated analysis reveals CD3 and FoxP3 as potential predictors of response to R-CHOP. Haematologica. 2015;100(3):363-369. [CrossRef]

- Xu-Monette ZY, Xiao M, Au Q, et al. Immune Profiling and Quantitative Analysis Decipher the Clinical Role of Immune-Checkpoint Expression in the Tumor Immune Microenvironment of DLBCL. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7(4):644-657. [CrossRef]

- Autio M, Leivonen SK, Brück O, et al. Clinical Impact of Immune Cells and Their Spatial Interactions in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28(4):781-792. [CrossRef]

- Song JY, Nwangwu M, He TF, et al. Low T-cell proportion in the tumor microenvironment is associated with immune escape and poor survival in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Haematologica. 2023;108(8):2167-2177. Published August 1, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jain MD, Zhao H, Wang X, et al. Tumor interferon signaling and suppressive myeloid cells are associated with CAR T-cell failure in large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2021;137(19):2621-2633. [CrossRef]

- Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Adult Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(1):45-56. [CrossRef]

- Abramson JS, Palomba ML, Gordon LI, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel for patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphomas (TRANSCEND NHL 001): a multicentre seamless design study. Lancet. 2020;396(10254):839-852. [CrossRef]

- Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-Cell Therapy in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(26):2531-2544. [CrossRef]

- Schubert ML, Bethge WA, Ayuk FA, et al. Outcomes of axicabtagene ciloleucel in PMBCL compare favorably with those in DLBCL: a GLA/DRST registry study. Blood Adv. 2023;7(20):6191-6195. [CrossRef]

- Chiappella A, Casadei B, Chiusolo P, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel treatment is more effective in primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphomas than in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas: the Italian CART-SIE study. Leukemia. 2024;38(5):1107-1114. [CrossRef]

- Olson NE, Ragan SP, Reiss DJ, et al. Exploration of Tumor Biopsy Gene Signatures to Understand the Role of the Tumor Microenvironment in Outcomes to Lisocabtagene Maraleucel. Mol Cancer Ther. 2023;22(3):406-418. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett NL, Assouline S, Giri P, et al. Mosunetuzumab monotherapy is active and tolerable in patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2023;7(17):4926-4935. [CrossRef]

- Lenz G, Wright G, Dave SS, et al. Stromal gene signatures in large-B-cell lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(22):2313-2323. [CrossRef]

- Bröske AE, Korfi K, Belousov A, et al. Pharmacodynamics and molecular correlates of response to glofitamab in relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2022;6(3):1025-1037. [CrossRef]

- Locke F, Chou J, Vardhanabhuti S, et al. Association of pretreatment tumor characteristics and clinical outcomes following second-line axicabtagene ciloleucel versus standard of care in patients with relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(16_suppl):7565-7565. [CrossRef]

- Brouwer-Visser J, Fiaschi N, Deering RP, et al. Molecular assessment of intratumoral immune cell subsets and potential mechanisms of resistance to odronextamab, a CD20×CD3 bispecific antibody, in patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2024;12(3). Published March 21, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mian A, Bhattarai N, Wei W, et al. Quantitative Assessment of the Evolution of Therapeutic Target Antigen Expression Level in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma in Response to Treatment. Blood. 2021;138:4367-4367. [CrossRef]

- Jain MD, Ziccheddu B, Coughlin CA, et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals complex genomic features underlying anti-CD19 CAR T-cell treatment failures in lymphoma. Blood. 2022;140(5):491-503. Correction appears in Blood. 2023 Oct 5;142(14):1255. 10.1182/blood.2023022211. [CrossRef]

- Locke FL, Filosto S, Chou J, et al. Impact of tumor microenvironment on efficacy of anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy or chemotherapy and transplant in large B cell lymphoma. Nat Med. 2024;30(2):507-518. [CrossRef]

- Schuster SJ, Huw LY, Bolen CR, et al. Loss of CD20 expression as a mechanism of resistance to mosunetuzumab in relapsed/refractory B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2024;143(9):822-832. [CrossRef]

- Nerreter T, Letschert S, Götz R, et al. Super-resolution microscopy reveals ultra-low CD19 expression on myeloma cells that triggers elimination by CD19 CAR-T. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3137. Published July 17, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Duell J, Leipold AM, Appenzeller S, et al. Sequential antigen loss and branching evolution in lymphoma after CD19- and CD20-targeted T-cell-redirecting therapy. Blood. 2024;143(8):685-696. [CrossRef]

- Brummel K, Eerkens AL, de Bruyn M, Nijman HW. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes: from prognosis to treatment selection. Br J Cancer. 2023;128(3):451-458. [CrossRef]

- Yan ZX, Li L, Wang W, et al. Clinical Efficacy and Tumor Microenvironment Influence in a Dose-Escalation Study of Anti-CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells in Refractory B-Cell Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(23):6995-7003. [CrossRef]

- Rossi J, Galon J, Chang E, et al. Abstract CT153: Pretreatment immunoscore and an inflamed tumor microenvironment (TME) are associated with efficacy in patients (Pts) with refractory large B cell lymphoma treated with axicabtagene ciloleucel (Axi-Cel) in ZUMA-1. Cancer Res. 2019;79. [CrossRef]

- Scholler N, Perbost R, Locke FL, et al. Tumor immune contexture is a determinant of anti-CD19 CAR T cell efficacy in large B cell lymphoma. Nat Med. 2022;28(9):1872-1882. [CrossRef]

- Galon J, Scholler N, Perbost R, et al. Tumor microenvironment associated with increased pretreatment density of activated PD-1+ LAG-3+/− TIM-3− CD8+ T cells facilitates clinical response to axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) in patients (pts) with large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3022. [CrossRef]

- Reiss D, Do T, Kuo D, et al. Multiplexed Immunofluorescence (IF) Analysis and Gene Expression Profiling of Biopsies from Patients with Relapsed/Refractory (R/R) Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) Treated with Lisocabtagene Maraleucel (liso-cel) in Transcend NHL 001 Reveal Patterns of Immune Infiltration Associated with Durable Response. Blood. 2019;134:202. [CrossRef]

- Swanson C, Do T, Merrigan S, et al. Predicting Clinical Response and Safety of JCAR017 in B-NHL Patients: Potential Importance of Tumor Microenvironment Biomarkers and CAR T-Cell Tumor Infiltration. Blood. 2017;130(Suppl 1):194.

- Bolen C, Roy S, Huw LY, et al. Baseline CD4 T Cells Are Associated with Improved Response to CD20-CD3 Bispecifics in Lymphoma. Blood. 2023;142:3005-3005. [CrossRef]

- Steidl C, Lee T, Shah SP, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages and survival in classic Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(10):875-885. [CrossRef]

- Boutilier AJ, Elsawa SF. Macrophage Polarization States in the Tumor Microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(13):6995. Published June 29, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mattie M, Grosso M, Auguste A, et al. Pre- and Post-Treatment Immune Contexture Correlates with Long Term Response in Large B Cell Lymphoma Patients Treated with Axicabtagene Ciloleucel (axi-cel). Blood. 2023;142(Suppl 1):226. [CrossRef]

- Veglia F, Sanseviero E, Gabrilovich DI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the era of increasing myeloid cell diversity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21(8):485-498. [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj S, Schrum AG, Cho HI, et al. Mechanism of T cell tolerance induced by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Immunol. 2010;184(6):3106-3116. [CrossRef]

- Chou J, Plaks V, Poddar S, et al. Favorable tumor immune microenvironment (TME) and robust chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell expansion may overcome tumor burden (TB) and promote durable efficacy with axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) in large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL). J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:7536-7536. [CrossRef]

- Chen PH, Lipschitz M, Weirather JL, et al. Activation of CAR and non-CAR T cells within the tumor microenvironment following CAR T cell therapy. JCI Insight. 2020;5(12). [CrossRef]

- Peng S, Bao Y. A narrative review of immune checkpoint mechanisms and current immune checkpoint therapy. Annals of Blood. 2021;7. [CrossRef]

- Majzner R, Frank M, Mount C, et al. CD58 Aberrations Limit Durable Responses to CD19 CAR in Large B Cell Lymphoma Patients Treated with Axicabtagene Ciloleucel but Can be Overcome through Novel CAR Engineering. Blood. 2020;136:53-54. [CrossRef]

- Yan X, Chen D, Ma X, et al. CD58 loss in tumor cells confers functional impairment of CAR T cells. Blood Adv. 2022;6(22):5844-5856. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).