1. Introduction

Considering the historical development and evolution of dental alloys, the first materials used in Dentistry were gold-based alloys. Gold is considered a superior metallic biomaterial due to its exceptional resistance to corrosion, which makes it ideal for noble metal applications in biologically sensitive environments. Its unique colour distinguishes gold from most other metals, except copper and cesium. In developing alloys for fixed dental prostheses, gold is also employed extensively because of its high electrical conductivity (conductive metals resist tarnishing and corrosion, ensuring the longevity and stability of dental restorations), and strong bonding with porcelain [

1]. These characteristics make it an ideal candidate for producing inlays, crowns and substructures for application in Dentistry. High-noble alloys based on gold and platinum have been favoured in Dentistry for their proven long-term use and clinical reliability.

Regarding the economic pressure, and increasing cost of noble metals, the exploration of more cost-effective alternatives, is making base alloys like CoCr attractive options. Besides lower prices, CoCr alloys provide satisfactory mechanical performance in the long term clinical use, with durability and wear resistance comparable to noble alloys [

2,

3]. However, there has been an increase in reports from clinical studies highlighting both biological and technological complications related to base metal alloys. In both in vitro and in vivo investigations there is evidence that dental restorations release metal ions, due primarily to corrosion [

4]. Due to the challenging conditions in oral environments, chemically and microorganism-induced corrosion are most likely to develop [

5]. Metal ions can be released locally and systemically, potentially contributing to the the development of oral and systemic health issues. The type of alloy and various corrosion factors influence the type and amounts of cations released significantly. Dental prostheses deal with the oral environment-dependent factors for extended periods, facing corrosive impacts such as saliva exposure, temperature and pH fluctuations, among others. The release of ions from metals in saliva can initiate oxidative reactions, leading to discolouration and the deposition of metal in the adjacent tissues. Health concerns are particularly significant for alloys containing nickel as an alloying element [

6,

7]. Recently, germanium (Ge) has been identified as a promising alternative alloying element [

8]. Previous research has revealed that adding germanium (Ge) to alloys results in reduced hardness, improved flowability, and less shrinkage during casting, while also offering a more cost-effective alternative to other precious metals [

8,

9].

Porcelain-fused-to-metal (PFM) fixed restorations often require subgingival margin preparation, which calls for a thorough evaluation of the host's biological response to specific metallic materials [

10]. To ensure these biomaterials remain within the physiological tolerance levels, it is important to examine the direct effects of different alloys on the host tissue, not only in their as-cast form, but also after thermomechanical and degassing treatments. For instance, the presence of oxide alloying elements formed during these processes may modulate or alter the host response.

There is little knowledge about the cytotoxic effect of the degassing process on noble porcelain fused to metal restorations.

Besides biological, technological challenges in dental restorations, such as the higher incidence of veneering porcelain chipping observed in base alloy substructures (18-25%) compared to noble alloys (4-10%), have been reported extensively [

11]. The main factors contributing to this discrepancy are thermal expansion compatibility and the characteristics of oxide layer formation [

12]. Noble alloys generally have a thermal expansion rate that matches porcelain closely, reducing thermal stress during cooling and firing, and thus minimising chipping. In contrast, base alloys often exhibit a significant mismatch in thermal expansion, leading to increased stress and a higher incidence of chipping [

13]. Additionally, base alloys form a thick, irregular oxide layer that can weaken the bond with porcelain, further contributing to the higher chipping rates. In comparison, noble alloys form a stable oxide layer that strengthens the bond, reducing the risk of chipping.

Moreover, one study, which analysed the discrepancy in chemical composition, revealed that base metal alloys differed more than noble alloys. The number of compositional discrepancies for gold alloys was 8% (1 of 13), and for base alloys 31% (4 of 13) [

14]. Unlike base alloys, noble alloys are less reactive with the environment, maintaining their intended composition and structural integrity over extended periods, and throughout their lifecycle. Base alloys have a higher tendency to oxidate, which can alter their composition. Besides, the different melting points of the metals in base alloys can lead to uneven mixing and segregation during casting [

15,

16]. For example, chromium and nickel have significantly different melting temperatures [

17], complicating the alloying process. From the practical point, clinicians are unable to confirm the exact alloy composition of prosthetic materials.

With this in mind, the ADA established the classification system [

18] for dental casting alloys which categorises alloys based on their composition. It divides alloys into three main groups:

High noble alloys, characterised by a noble-metal content of a minimum of 60 wt% and a gold content of at least 40%.

Noble alloys, containing a noble-metal content of at least 25%, with no specific requirement for gold content.

Predominantly base metal alloys, possessing a noble-metal content below 25%.[

19]

The objective of this investigation was to analyse the thermomechanical and biocompatibility properties of a high noble novel Au-Pt-Ge porcelain-fused-to-metal alloy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Alloy Production Experiment Parameters

The melting of pure components (Au=99.99 wt.%, Pt=99.99 wt.%, Ir=99.99wt.%, Ag=99.99 wt.%, Ge=99.99 wt.%, Rh=99.99 wt.%) was performed in an induction vacuum pressure casting machine, Galloni G3 (Aseg Galloni S.p.A., Milano, Italy). The initial melting parameters were at the vacuum p=-0.6 bar and temperature T=1030°C. At the onset of melting, the temperature increased to 1120 °C and held for 2 min. The melt was then cast into a graphite crucible at a pressure of p=0.6 bar, with an overpressure of p=1.1 bar. The melt was held in the crucible for 6 minutes (360 seconds). The cast ingot had dimensions of 30 x 10 x 3 mm.

After casting, the obtained alloy ingot was treated thermomechanically, using a procedure of profile rolling with intermittent thermal treatment. Rolling was performed from a flat profile of 3 x 10 mm with a thickness of 3 mm with three rolling steps with varying degrees of deformation, and intermediate heating at a temperature of 700-750 °C for 15 min. This thermal treatment was performed in order to reduce the internal stress of the alloy caused by rolling, increase ductility through recrystallisation, and enhance the homogeneity of the dental alloy microstructure. The material was rolled into a strip, reducing the thickness from 3 mm to 1.4 mm, followed by cutting into tile-shaped specimens, with dimensions of 7 x 7 x 1.4 mm.

The ternary system of the Au-Pt-Ge alloy had a nominal composition of 80Au-10,8Pt-1Ge, and about 8 wt.% alloying elements (Ag, Ir, Rh ).

2.2. DSC Analysis

DSC analysis of the obtained dental alloy was conducted, to determine the onset of melting enthalpy. The sample for measurement had dimensions of approximately 2 x 2 x 2 mm and weighed 40.63 mg, taken from the thermomechanical treatment of the alloy.

For determining the melting interval, we performed an additional analysis using a sample weighing 0.1633 g. The analysis programme involved heating at 10 K/min up to a temperature of 1300 °C and cooling to room temperature at 20 K/min. The analysis was carried out in an argon protective atmosphere. The analysis was performed using an NETZSCH STA 449 F3 Jupiter device (Netzsch-Gerätebau GmbH, Selb, Germany).

2.3. Hardness

According to the Standard 6507-1:1998, the measurements of hardness were conducted using the static Vickers test on the Zwick 3212 microhardness measurement device (ZwickRoell AG, Ulm, Germany). An applied load of F=49 N was used for testing the samples, as per the Standard. Six measurements were performed for each sample.

2.4. Density

The density was measured with a 25 mL pycnometer and deionised water. The pycnometer was first weighed empty. It was then weighed with the cast alloy sample. This was followed by five measurements of the water-filled pycnometer without a sample, and five measurements of the water-filled pycnometer with the cast alloy sample. A scale with four decimal places was used for the weighing. The temperature of the water was 19 °C, and the density of the water was 0.998 g/cm3. The density of the cast sample was calculated from the five measurements of the pycnometer displaced water volume and known weight of the sample. The measured density was used for the production of a test dental bridge with the lost-wax cast method.

2.5. Dilatometric Coefficient (CTE) Analysis

Testing of the thermal expansion coefficient (CTE) was conducted on the Mechanical Dilatometry device DIL 805A/D (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA). The measurements were performed on 3 samples (dimensions Φ4 x 10 mm).

2.6. Static Immersion Testing

2.6.1. Preparation of Solution - Artificial Saliva

A solution of artificial saliva was prepared according to the ISO 10271 Standard. 5850 g of NaCl and 10.0 g of > 85% C3H6O3 were dissolved in 300 mL of water. Distilled water was then added to the solution to a total volume of 1000 mL. The prepared solution had a pH value of 2.24, meeting the Standard`s requirements.

2.6.2. Sample Preparation

Two samples for the static immersion testing were prepared in accordance with ISO 10271, with the dimensions 34 x 13 x 1.5 mm and a total surface area of 10.25 cm2. Prior to immersion testing, the samples were cleaned in an ultrasonic bath with ethanol, rinsed with distilled water, and dried with dry air. After cleaning, they were measured and weighed.

2.6.3. Testing Procedure

The samples were immersed in 20 mL of each test solution in a test tube closed with a rubber cork using nylon string. The test duration was 168 h (7 days) at a constant temperature of 37 ± 0.2 °C. Parallel with the samples, a reference pure solution with no samples was treated in the same way. To evaluate the migration of ions from the samples into the solution, the chemical content of the suspensions was overseen by ICP-MS.

2.7. Microstructure Investigations

The produced alloy casting tile sample for the microstructure investigations was cold mounted and ground with 600 and 1200 grit size. This was followed by polishing with 1 μm and 0.05 μm aluminium oxide suspensions. After polishing, etching was performed using a solution prepared by mixing 30 mL distilled water, 25 mL HCl, and 5 mL HNO3. The sample was etched for 60 seconds, and then rinsed with ammonium hydroxide and distilled water. A brief manual polishing with 0.05 μm aluminium oxide suspension was performed, followed by cleaning with distilled water in an ultrasonic bath.

The microstructure of the finally polished and etched sample was investigated with an optical metallographic microscope, Nikon Epiphot 300 (Tokyo, Japan), equipped with a CCD camera Olympus DP12 (Boston, MA, USA). A grain size analysis of the alloy was performed with the planimetric method according to ASTM E112. A Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), Sirion 400NC (FEI, Hillsboro, Oregon, USA) was used for detailed microstructure observation, with an Energy-Dispersive X-ray spectroscopy detector INCA 350 (Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK) for microchemical analysis.

2.8. Production of a Test PFM Dental Bridge

A 3-unit dental bridge substructure was modelled by hand using wax. The refractory material used was phosphate based Interfine K+B Speed (Interdent d.o.o., Celje, Slovenia). The refractory mass was mixed according to the manufacturer's instructions for precious alloys with Expasol liquid (Interdent d.o.o., Celje, Slovenia) and distilled water, with a ratio of 60:40. The rapid heating method was used for the refractory block. After 20 min of mixing the powder and liquid of the refractory mass, the cuvette was introduced into an annealing furnace preheated to 850°C. After holding for 40 min at this temperature, casting was started in a furnace with an induction heater. A graphite crucible was used to melt the alloy. The alloy melted completely very quickly (in a few seconds) and was poured into a heated refractory block using a centrifuge. The refractory block was cooled spontaneously to room temperature. The cast substructure was removed from the refractory block.

The opaquers and faceted ceramics used were manufactured by Ivoclar Vivadent AG (Schaan, Liechtenstein). After processing, a wash opaquer was applied, fired at 890°C. After the wash layer, two more opaquer layers were applied, fired at 870°C. The IPS Style Ceram Powder Opaquer was used.

After the opaquer, an IPS Style Ceram Dentin was applied and fired at 800°C, according to the Standard programme for the given ceramic in the Ivoclar ceramic oven. The dentin layer was followed by a second firing, the incisal layer, using IPS Style Incisal, also at 800°C. The faceted ceramic used was in the A1 colour, glazed at 770°C.

The thin edge of the crowns, which was not covered by ceramic, was polished after glazing with a green polishing stone for metal polishing and a yellow polishing stone for polishing ceramics. A high gloss and smoothness of the alloy were obtained.

2.9. Biocompatibility Evaluation

2.9.1. Samples` Preparation for Biocompatibility Testing

The samples used in the present investigation were divided into three groups (control-glass cover slip, Au-Pt-Ge in as-cast oxidised and polished condition of Au-Pt-Ge).

The oxidised as-cast castings were cleaned initially by air blasting with 50 μm Al2O3 and then with 50 μm glass beads, followed by a 5-minute ultrasonic cleaning in 95% ethanol. The degassing protocol included treatment in a ceramic furnace (Shofu dental laboratory). The heating was performed from 650°C to 940°C at a rate of 55°C with a 5-minute hold at the peak temperature. The samples were then bench-cooled to room temperature. After degassing and heat treatment, the samples underwent additional air blasting with glass beads and ultrasonic cleaning in 95% ethanol.

The polished samples were prepared by polishing the air blasted samples with an abrasive wheel, and rouge on a rag wheel, followed by a 10-minute ultrasonic cleaning. These samples were also degassed and heat-treated. Following the heat treatment, they were polished and cleaned as before.

Before the biological research, the examined samples were sterilised in an autoclave for 15 min at 121°C.

2.9.2. MTT Assay

An in vitro primary biocompatibility test was conducted on human gingival cells, as previously described [

20]. The gingival tissues were collected from healthy donors with written consent. The tissues were minced into 1 mm

3 fragments and processed using the outgrowth method. These tissue fragments were then placed in 25 cm

2 culture flasks containing a growth medium (DMEM/F12 with 10% FBS and 1% ABAM from Gibco, Thermo Fisher, MA, USA) and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO

2 environment. The cells were passaged regularly when they reached 80% confluence, and the culture medium was changed every 3 days.

In accordance with ISO 10993-5:2009, for the indirect test, the samples (control, Au-Pt-Ge, and Au-Pt-Ge oxidised) were placed in a tube containing 10 mL of complete medium, incubated at 37 °C for two time intervals (1 and 7 days), and removed, while the remaining supernatants was used in further experiments. The cells were seeded in a 96-well plate (,.000 cells/well), and the next day 100 µL of supernatant was added to the corresponding wells (indirect MTT assay).

For the direct MTT test, the samples were placed onto 24-well plates; 20,000 cells/well were seeded onto discs and incubated in freshly prepared growth medium at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere for up to 7 days. The medium was changed every 3rd day. Mitochondrial activity was assessed after the 7th day of treatment.

For the assessment of mitochondrial activity after direct and indirect exposure to the tested samples, the medium was discarded, and 100 µL of solution containing 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5 diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT, 0.5 mg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to each well and incubated. After 4 h the supernatant was discarded; dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to each well; and the plate was placed on a shaker for 20 min, at 250 rpm, in the dark, at 37 °C. The extracted coloured solutions from 24-well plates were transferred into a new 96-well plate. The optical density was measured at 550 nm using a microplate reader RT-2100c (Rayto, Shenzhen, China). The results were presented as a percentage of the control value.

3. Results

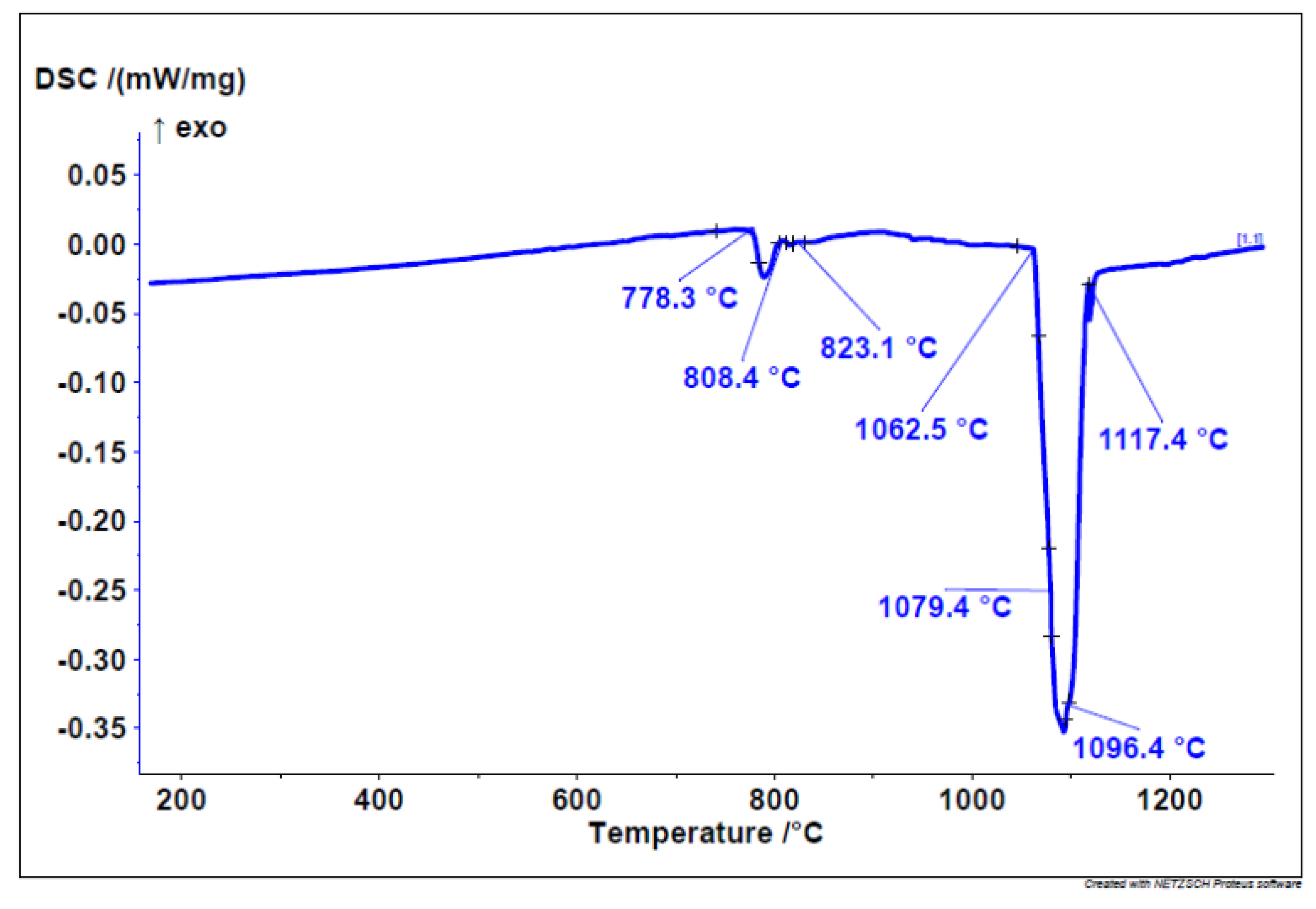

3.1. DSC Results

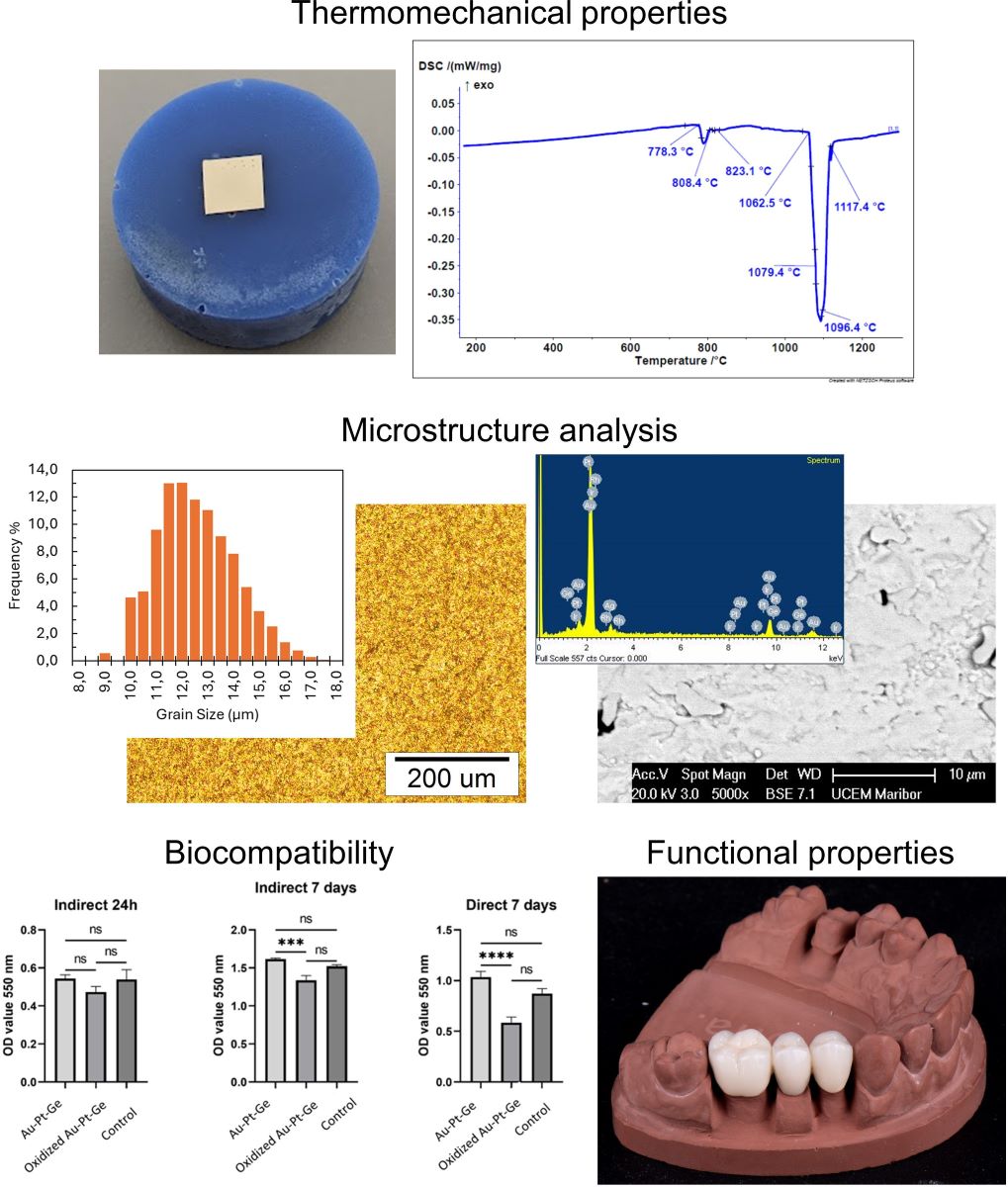

The onset of melting enthalpy, or the melting point, was found to be at 1069.71 ± 3 °C. The DSC heating curve (

Figure 1) indicates the melting of a dental alloy, starting at 778 °C, where a low-melting eutectic is likely to melt. Within this temperature range, three different phases/eutectics also undergo melting. The main melting portion begins at 1062 °C in three steps or phases.

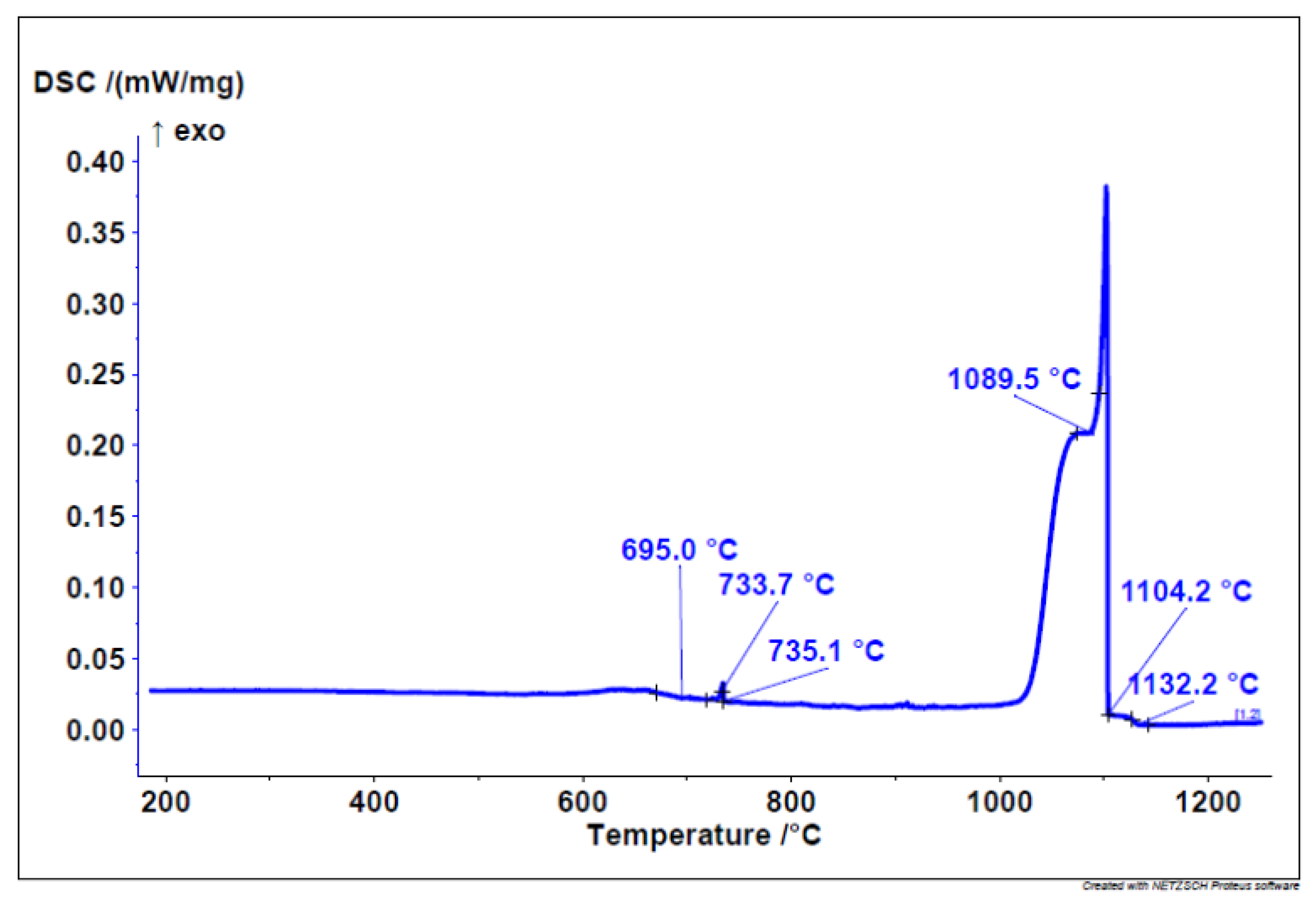

The start of solidification is revealed by the cooling DSC curve at 1132 °C with three solidification temperatures/phases. Similarly, on the cooling curve (

Figure 2), the solidification of three different phases/eutectics can be observed within a range of approximately 700 °C. This leads to the conclusion that six different phases appear in the microstructure.

3.2. Microhardness

The average results of the hardness measurement are presented in

Table 1. As seen, the average microhardness value was 127.17 HV.

3.3. Density

The measured density was calculated from the pycnometer weight measurements using the equation

and a measured mass of 3.03 g for the alloy sample. The average measured density of the alloy sample was 16.46 ± 0.23 g/cm

3, shown in

Table 2.

3.4. CTE Results

Testing of the thermal expansion coefficient showed that the average value of CTE (50-900 °C) for the Au-Pt-Ge alloy is about 15.84×10

-6 K

-1 (

Table 3).

3.5. ICP Analysis of Solutions after Immersion Testing

As seen from

Table 3, the total ions released for the Au-Pt-Ge dental alloy were 1,622 μg/cm

2 per 7 days.

Table 3.

Results of the ICP analysis in µg/cm2 after 7 days of immersion of the Au-Pt-Ge sample in artificial saliva (pH 2.24).

Table 3.

Results of the ICP analysis in µg/cm2 after 7 days of immersion of the Au-Pt-Ge sample in artificial saliva (pH 2.24).

| Ag |

Au |

Be |

Cd |

Ge |

In |

Ir |

Ni |

Pb |

Pd |

Pt |

Rh |

Total |

| 0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1.622 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1.622 |

3.6. Microstructure Investigations

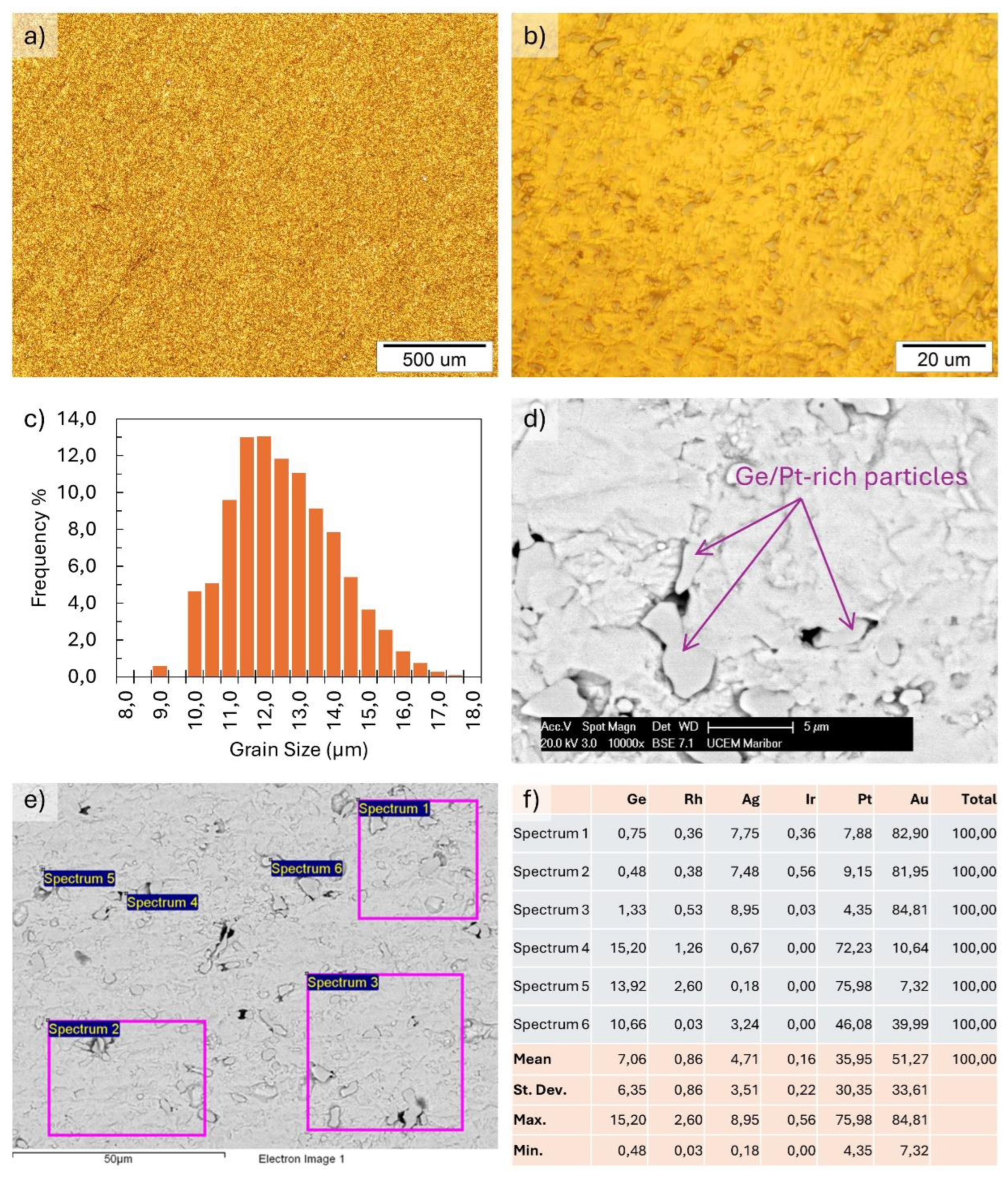

The microstructural investigations are presented in

Figure 3. The optical metallography in Figures 3a) and b) show a homogeneous microstructure. The ASTM grain size analysis result for the alloy grain size number G was 13.16, with a mean intercept distance of 3.35 µm. The frequency of grain size distribution is shown in

Figure 3c). The SEM images show a similar homogeneous microstructure. The EDX microchemical analysis shows an alloy matrix with the initial basic composition, along with Ge- and Pt-rich particles with sizes of about a few μm up to around 10 μm. Examination of the Ge/Pt-rich particles in the matrix showed a relatively homogeneous distribution, with no visible areas of particle clustering or larger particles present, which would indicate areas of higher Ge concentration in the matrix.

Figure 3f) shows the results of an EDX analysis of the matrix and Ge/Pt-rich particles, typical for the sample surface, shown in Figures 3d) and f).

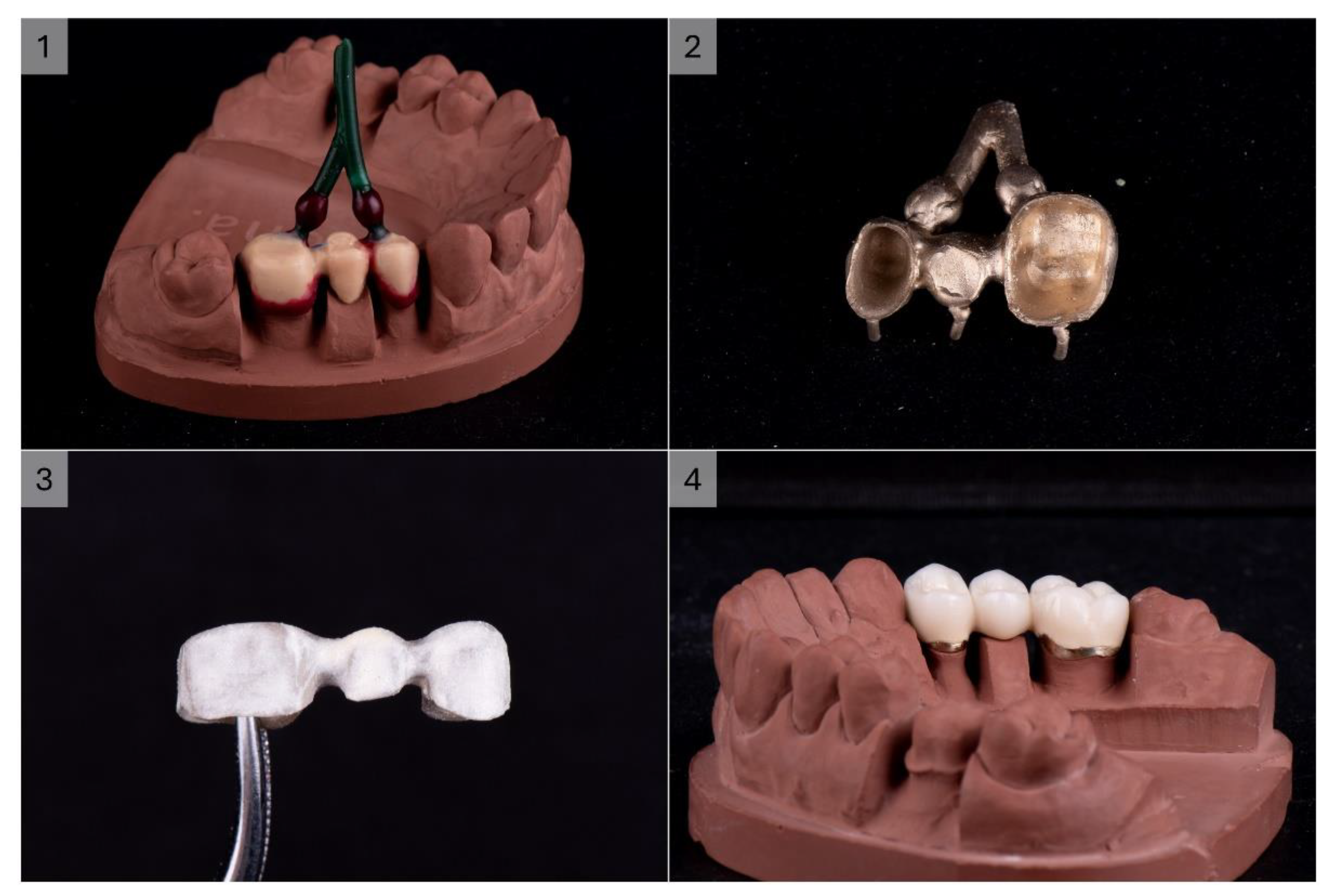

3.7. Produced Test PFM Dental Bridge

The produced 3-unit dental bridge casting was completely homogeneous, compact, with a nice golden colour. The processing of the metal substructure was not difficult, without the need for great force or a high number of revolutions of the cutter. Moderate heating of the metal during processing was observed, which was expected due to friction. The overall impression is that machining is faster and easier than CoCr alloys. A high gloss and smoothness of the alloy was obtained with polishing and glazing, which was also faster and easier than with base metal alloys. The finished product had a noticeably pleasant colour and excellent optical characteristics of the ceramics on the given alloy (

Figure 4).

3.8. Biocompatibility

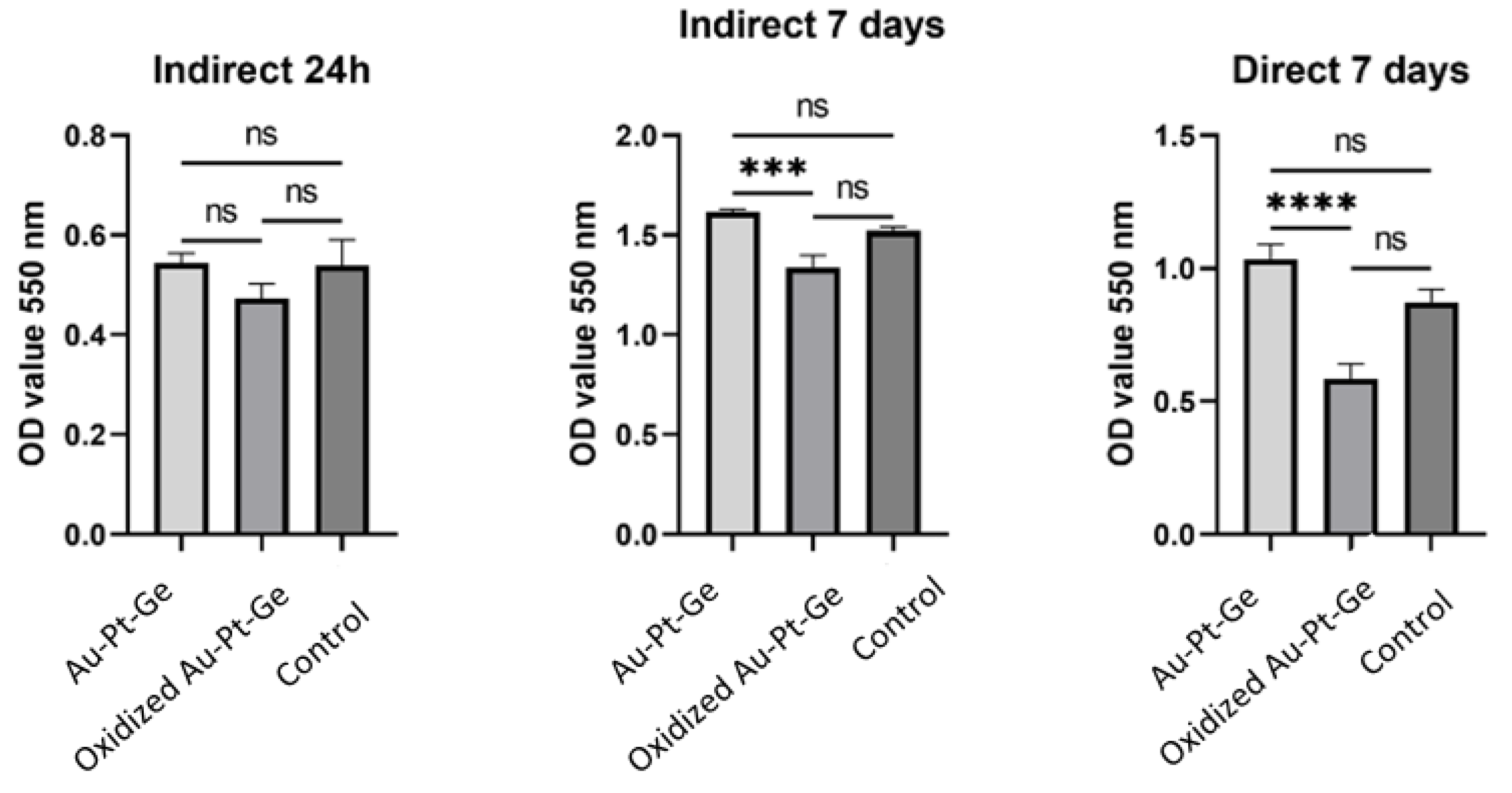

After 24 hours of indirect exposure of human gingival cells (HGCs) to the tested materials, the mitochondrial activity observed in the tested groups (control and polished Au-Pt-Ge) was almost similar. Lower activity was observed in cells treated with oxidised Au-Pt-Ge supernatants, but there were no statistically significant differences compared to the control and polished Au-Pt-Ge samples (

Figure 5).

After 7 days of both indirect and direct exposure it was observed that cell viability increased in contact with the as cast Au-Pt-Ge, and decreased in contact with theoxidised supernatants compared to the control. When comparing the cells' mitochondrial activity between the groups (the control group, the cells seeded on Au-Pt-Ge, and the cells seeded on the oxidised Au-Pt-Ge samples), the ANOVA test indicated statistically significant differences only between the oxidised and Au-Pt-Ge groups in terms of both indirect and direct contact (

Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Optical density measurements for the MTT assay of cell viability.

Figure 5.

Optical density measurements for the MTT assay of cell viability.

4. Discussion

This study aimed primarily to investigate the biomechanical properties of the novel ternary noble Au-Pt-Ge alloy. For the development of a dental alloy, we chose the composition described above (80% Au; 10.84% Pt; 1% Ge; 8% alloying elements). Historically, the main noble alloys utilised in dental prosthetics contained significant amounts of palladium. Recent research has shown that palladium can cause allergic reactions, even though it is considered a noble metal [

21,

22]. This has led to the development of a new palladium-free alloy made of gold, platinum and germanium, to reduce the potential adverse effects associated with palladium. [

23,

24]. Additionally, a higher Pt content is essential to elevate the melting range effectively beyond the porcelain firing temperature, thereby preventing distortion during the porcelain application phase. According to the firing temperature, dental porcelains are divided into four categories: ultra-low fusing (≤850 °C), low fusing (850-1100 °C), medium fusing (1100-1300 °C), and high fusing (≥1300 °C) (the latter of which are used less frequently) [

25]. So, for dental alloys used in porcelain-fused-to-metal (PFM) restorations, the key physical requirement is a melting point of nearly 1100 °C. However, most of the alloys with high Au content that meet the Standards` requirements for PFM application melt at temperatures below 1000 °C, which makes them easier to cast than base alloys. However, gold alloys designed for porcelain-fused applications must have a solidus temperature at least 100 °C higher than the firing temperature of dental porcelain, which, for most veneering porcelains, is between 960 and 980 °C. This higher temperature is crucial to ensure the frameworks maintain their shape and do not sag during firing [

26].

Based on the analyses of the manufactured alloy, its thermomechanical properties are suitable for application in Dentistry for prosthetic products.

Considering further thermomechanical features, high noble alloys are produced carefully to have a coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) that matches that of dental porcelain closely. The metal alloy is typically designed to have a slightly higher CTE than the porcelain, with the coefficients generally falling within the intervals of 12.7-14.8 × 10

-6 K

-1 for the alloys and 10.8-14.6 × 10

-6 K

-1 for the porcelain [

27,

28]. This slight mismatch in CTE values serves a specific purpose. As the materials cool from the high firing temperatures used during the porcelain application process, the metal contracts slightly more than the porcelain. This differential contraction places the porcelain in a state of slight compressive stress. Such compressive stress is beneficial, as it helps prevent the development of tensile stress, which could lead to cracking or debonding of the porcelain from the metal substructure. The induced compressive stress enhances the bond's strength and stability, minimising the risk of mechanical failure under the functional loads experienced in the oral environment. By ensuring that the CTE values of the alloy and porcelain are well-matched yet strategically different, high noble alloys provide a stable base for durable and reliable dental restorations [

7].

Considering the results of the sample hardness measurements, it was observed that the alloy demonstrated lower hardness but still met the minimum values required for dental applications in fixed restorations, including up to three-unit bridges [

29]. For single crowns and up to three-unit bridges the hardness of the selected alloy should be at least 130 HV [

26]. The tested samples, irrespective of the fabrication method, are not suitable for multiunit fixed prostheses, especially for extensive multiunit fixed restorations. The metallographic investigation showed a homogeneous, finely grained microstructure, with a grain size number G of 13.16. The microstructure and chemical analyses showed apparent Ge segregation. The Ge segregation decreases the alloy’s mechanical properties and may affect workability negatively, as the alloy becomes more brittle with higher additions of Ge. To reduce these negative effects, the Ge distribution must be homogeneous in the matrix. The observations and analyses of the microstructure showed an even concentration of Ge across the sample, indicating that a consistent distribution had been achieved.

The metal ion release test demonstrated that the alloy is biologically safe for use in the oral environment. According to the ISO 22674 Standard for metallic dental materials [

30], it is required that the cumulative metal ion concentration released from the alloy should not exceed 200 μg/cm

2 within a 7-day period ± 1 h, at a temperature of 37 ± 1 °C. The Au-Pt-Ge dental alloy complies with these criteria, as the measured ion release is minimal, making it suitable for application in dental prosthetics. No noble metal ions were detected from the ion release, while Ge was detected.

Additional density measurements of the alloy were performed, for facilitating the production of the test PFM dental bridge. The measured density showed typical values for high noble dental alloys, suitable for dental restorations of this type. The production of the dental bridge was performed with no major difficulties or defects in the casting. The substructure was homogeneous, while the processing and machining were less demanding and faster than with base metal or typical CoCr alloys. The ceramic firing also did not introduce any defects or sagging of the metallic substructure. The appearance of the finished PFM dental bridge was of a high standard for dental restorations, with excellent optical characteristics of the ceramics.

The biocompatibility assessment of noble alloys has been extensively investigated through multiple "in vivo" and "in vitro" studies [

31,

32,

33,

34]. The primary emphasis in these investigations centered on assessing the performance of polished Porce-lain-Fused-to-Metal (PFM) alloys. Overall, these studies conclude that these alloys are generally safe and non-toxic when polished [

34].

Our study examined cell viability following plating for the degassing as-cast condition and polished samples. Significantly higher viability ratings were noted on the polished samples. This result is supported by a similar study conducted on an Au-based PFM alloy, which demonstrated improved biocompatibility of polished casting alloys compared to their as-cast counterparts after degassing process [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Cells in contact with the polished samples had higher optical densities than those in contact with the samples after degassing treatment [

31,

39]. Oxidized forms induced changes in cells, including actin filament disintegration, indicating a mild to moderate response [

39].

Additionally, reactions in gingival tissues near dental alloys are more frequent than previously thought, with chronic inflammation and metal ion accumulation observed. While adding non-noble elements like In, Sn, or Zn improves porcelain adhesion, it also increases corrosion and metal ion release, raising toxicity concerns [

35,

36,

37,

38]. High-noble alloys generally demonstrated better biocompatibility, though heat treatment heightened ion release and reduced cell viability, especially if the alloying element is zinc [

40,

41]. To minimize ion release and protect oral health, removing the oxide layer is recommended.

Although a significant portion of the metallic substructure is covered by veneering porcelain, typically the cervical part, i.e., the collar, remains exposed. As it is situated subgingivally, thereby in direct contact with the surrounding tissue and susceptible to exposure to oral and subgingival fluids, this area needs to be polished highly.

5. Conclusions

Based on the conducted investigation on the development of an Au-Pt-Ge based dental alloy, the following conclusions may be given:

Based on the analyses of the manufactured alloy, its thermomechanical properties are suitable for application in Dentistry for prosthetic products.

Due to a lower hardness, the designed alloy is not suitable for extensive multiunit fixed restorations.

The cast alloy has a finely grained microstructure with Ge segregations, which decrease the alloy’s mechanical properties. The homogeneous distribution of Ge in the matrix reduces these negative effects on the mechanical properties.

The measured metal ion release from immersion testing was minimal, demonstrating that the alloy is biologically safe for use in an oral environment.

The production of the 3-unit PFM dental bridge was performed with no major difficulties in processing, while being less demanding and faster than with base metals, and resulting in the production of a high standard dental restoration

The cell viability examination for as-cast and polished alloy samples showed significantly higher viability ratings on the polished samples, demonstrating the improved biocompatibility of polished casting alloys compared to their as-cast counterparts. The results show that a dental substructure in direct contact with the surrounding tissue and susceptible to exposure to oral and subgingival fluids should be polished highly.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, P.M., V.L. and R.R.; methodology, P.M., M.M.L., D.M., M.L. and E.K.L.; validation, P.M., M.M.L., D.M., M.L., E.K.L. and G.V.; formal analysis, P.M., M.M.L. and G.V.; investigation, D.M., M.L. and E.K.L.; resources, V.L. and R.R.; data curation, P.M., M.M.L., M.L. and E.K.L.; writing—original draft preparation, P.M., D.M., M.M.L., M.L., E.K.L. and G.V.; writing—review and editing, P.M., G.V., I.A., V.L. and R.R.; visualisation, P.M. and M.M.L.; supervision, I.A., V.L. and R.R.; project administration, V.L. and R.R.; funding acquisition, I.A., V.L. and R.R. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is part of the Eureka E!17091 GOLD-GER Project, Grant number 337-00-00294/2021-09/07, funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development, Serbia. This research and APC was funded by the Slovenian Research Agency ARIS (P2-0120 Research Programme).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors Peter Majerič and Rebeka Rudolf were employed by the company Zlatarna Celje d.o.o. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Khmaj, M.R.; Khmaj, A.B.; Brantley, W.A.; Johnston, W.M.; Dasgupta, T. Comparison of the Metal-to-Ceramic Bond Strengths of Four Noble Alloys with Press-on-Metal and Conventional Porcelain Layering Techniques. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 2014, 112, 1194–1200. [CrossRef]

- Dolgov, A.N.A.; Dikova, A.T.; Dzhendov, A.D.; Pavlova, D.; Simov, A.M. MECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF DENTAL Co-Cr ALLOYS FABRICATED VIA CASTING AND SELECTIVE LASER MELTING. 2016.

- Nakano, T.; Hagihara, K.; Ribeiro, A.R.; Fujii, Y.; Todo, T.; Fukushima, R.; Rocha, L.A. Orientation Dependence of the Wear Resistance in the Co–Cr–Mo Single Crystal. Wear 2021, 478–479, 203758. [CrossRef]

- Eliaz, N. Corrosion of Metallic Biomaterials: A Review. Materials (Basel) 2019, 12, E407. [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, U.; Felicita, A.S.; Mahendra, L.; Kanji, M.A.; Varadarajan, S.; Raj, A.T.; Feroz, S.M.A.; Mehta, D.; Baeshen, H.A.; Patil, S. Assessing the Potential Association Between Microbes and Corrosion of Intra-Oral Metallic Alloy-Based Dental Appliances Through a Systematic Review of the Literature. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Urbutytė, K.; Barčiūtė, A.; Lopatienė, K. The Changes in Nickel and Chromium Ion Levels in Saliva with Fixed Orthodontic Appliances: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 4739. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, P.; Agrawal, S.; Bansal, A.; Jain, A.; Tiwari, U.; Anand, A. Assessment of Nickel Release from Various Dental Appliances Used Routinely in Pediatric Dentistry. Indian J Dent 2016, 7, 81–85. [CrossRef]

- Vastag, G.; Majeric, P.; Lazic, V.; Rudolf, R. Electrochemical Behaviour of an Au-Ge Alloy in an Artificial Saliva and Sweat Solution. Metals 2024, 14, 668. [CrossRef]

- Rudolf, R.; Majerič, P.; Lazić, V.; Grgur, B. Development of a New AuCuZnGe Alloy and Determination of Its Corrosion Properties. Metals 2022, 12, 1284. [CrossRef]

- Kancyper, S.G.; Koka, S. The Influence of Intracrevicular Crown Margins on Gingival Health: Preliminary Findings. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 2001, 85, 461–465. [CrossRef]

- Behr, M.; Zeman, F.; Baitinger, T.; Galler, J.; Koller, M.; Handel, G.; Rosentritt, M. The Clinical Performance of Porcelain-Fused-to-Metal Precious Alloy Single Crowns: Chipping, Recurrent Caries, Periodontitis, and Loss of Retention. Int J Prosthodont 2014, 27, 153–160. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.; Shiraishi, T.; Al-Salehi, S.K. Ion Release from Experimental Au–Pt-Based Metal–Ceramic Alloys. Dental Materials 2010, 26, 682–687. [CrossRef]

- Özcan, M. Fracture Reasons in Ceramic-Fused-to-Metal Restorations (Review). Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 2003, 30. [CrossRef]

- Haugen, H.J.; Soltvedt, B.M.; Nguyen, P.N.; Ronold, H.J.; Johnsen, G.F. Discrepancy in Alloy Composition of Imported and Non-Imported Porcelain-Fused-to-Metal (PFM) Crowns Produced by Norwegian Dental Laboratories. Biomater Investig Dent 7, 41–49. [CrossRef]

- Uriciuc, W.A.; Boșca, A.B.; Băbțan, A.-M.; Vermeșan, H.; Cristea, C.; Tertiș, M.; Pășcuță, P.; Borodi, G.; Suciu, M.; Barbu-Tudoran, L.; et al. Study on the Surface of Cobalt-Chromium Dental Alloys and Their Behavior in Oral Cavity as Cast Materials. Materials (Basel) 2022, 15, 3052. [CrossRef]

- Lojen, G.; Stambolić, A.; Šetina Batič, B.; Rudolf, R. Experimental Continuous Casting of Nitinol. Metals 2020, 10, 505. [CrossRef]

- Lugscheider, E.; Knotek, O.; Klöhn, K. Melting Behaviour of Nickel—Chromium—Silicon Alloys. Thermochimica Acta 1979, 29, 323–326. [CrossRef]

- Chapter 10 - Restorative Materials: Metals. In Craig’s Restorative Dental Materials (Fourteenth Edition); Sakaguchi, R., Ferracane, J., Powers, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, 2019; pp. 171–208 ISBN 978-0-323-47821-2.

- Grgur, B.N.; Lazić, V.; Stojić, D.; Rudolf, R. Electrochemical Testing of Noble Metal Dental Alloys: The Influence of Their Chemical Composition on the Corrosion Resistance. Corrosion Science 2021, 184, 109412. [CrossRef]

- Lazić, M.; Lazić, M.M.; Karišik, M.J.; Lazarević, M.; Jug, A.; Anžel, I.; Milašin, J. Biocompatibility Study of a Cu-Al-Ni Rod Obtained by Continuous Casting. Processes 2022, 10, 1507. [CrossRef]

- Faurschou, A.; Menné, T.; Johansen, J.; Thyssen, J. Metal Allergen of the 21st Century—A Review on Exposure, Epidemiology and Clinical Manifestations of Palladium Allergy. Contact dermatitis 2011, 64, 185–195. [CrossRef]

- Bordel-Gómez, M. at; Miranda-Romero, A. Palladium Allergy: A Frequent Sensitisation. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2008, 36, 306–307. [CrossRef]

- J, M.; Rj, S.; Cj, K.; T, R.; Im, van H.; Me, von B.; Aj, F. Palladium-Based Dental Alloys Are Associated with Oral Disease and Palladium-Induced Immune Responses. Contact dermatitis 2014, 71. [CrossRef]

- H, S.; K, K.; M, S.; T, E.; R, M.; Y, N.; K, N.; T, Y.; H, I.; T, M.; et al. Cross-Reactivity of Palladium in a Murine Model of Metal-Induced Allergic Contact Dermatitis. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, V.P.; Rekow, E.D. 23 - Dental Ceramics. In Bioceramics and their Clinical Applications; Kokubo, T., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Biomaterials; Woodhead Publishing, 2008; pp. 518–547 ISBN 978-1-84569-204-9.

- Knosp, H.; Nawaz, M.; Stümke, M. Dental Gold Alloys: Composition, Properties and Applications. Gold Bull 1981, 14, 57–64. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, S.C.; Pagnano, V.O.; Rollo, J.M.D. de A.; Leal, M.B.; Bezzon, O.L. CORRELATION BETWEEN METAL-CERAMIC BOND STRENGTH AND COEFFICIENT OF LINEAR THERMAL EXPANSION DIFFERENCE. J Appl Oral Sci 2009, 17, 122–128. [CrossRef]

- Lazi, V.; Stamenkovi, D.; Todorovi, A.; Rudolf, R.; Anžel, I. INVESTIGATION OF MECHANICAL AND BIOMEDICAL PROPERTIES OF NEW DENTAL ALLOY WITH HIGH CONTENT OF Au. JOURNAL OF METALLURGY.

- Dental Gold Alloys and Gold Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications | SpringerLink Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-98746-6 (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- SIST EN ISO 226742022 - SIST EN ISO 226742022.Pdf.

- Craig, R.G.; Hanks, C.T. Cytotoxicity of Experimental Casting Alloys Evaluated by Cell Culture Tests. J Dent Res 1990, 69, 1539–1542. [CrossRef]

- Reaction of Fibroblasts to Various Dental Casting Alloys - PubMed Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3145968/ (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Kansu, G.; Aydin, A.K. Evaluation of the Biocompatibility of Various Dental Alloys: Part I--Toxic Potentials. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent 1996, 4, 129–136.

- Rutkunas, V.; Bukelskiene, V.; Sabaliauskas, V.; Balciunas, E.; Malinauskas, M.; Baltriukiene, D. Assessment of Human Gingival Fibroblast Interaction with Dental Implant Abutment Materials. J Mater Sci: Mater Med 2015, 26, 169. [CrossRef]

- Bergman, M. Corrosion in the Oral Cavity--Potential Local and Systemic Effects. Int Dent J 1986, 36, 41–44.

- Berstein, A.; Bernauer, I.; Marx, R.; Geurtsen, W. Human Cell Culture Studies with Dental Metallic Materials. Biomaterials 1992, 13, 98–100. [CrossRef]

- Schmalz, G.; Garhammer, P. Biological Interactions of Dental Cast Alloys with Oral Tissues. Dent Mater 2002, 18, 396–406. [CrossRef]

- Schmalz, G.; Langer, H.; Schweikl, H. Cytotoxicity of Dental Alloy Extracts and Corresponding Metal Salt Solutions. J Dent Res 1998, 77, 1772–1778. [CrossRef]

- Doktorarbeit_Celinski.Pdf.

- Wataha, J.C.; Lockwood, P.E.; Nelson, S.K. Initial versus Subsequent Release of Elements from Dental Casting Alloys. J Oral Rehabil 1999, 26, 798–803. [CrossRef]

- Effect of Alloy Surface Composition on Release of Elements from Dental Casting Alloys - WATAHA - 1996 - Journal of Oral Rehabilitation - Wiley Online Library Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2842.1996.tb00896.x (accessed on 9 September 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).