Submitted:

11 September 2024

Posted:

12 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

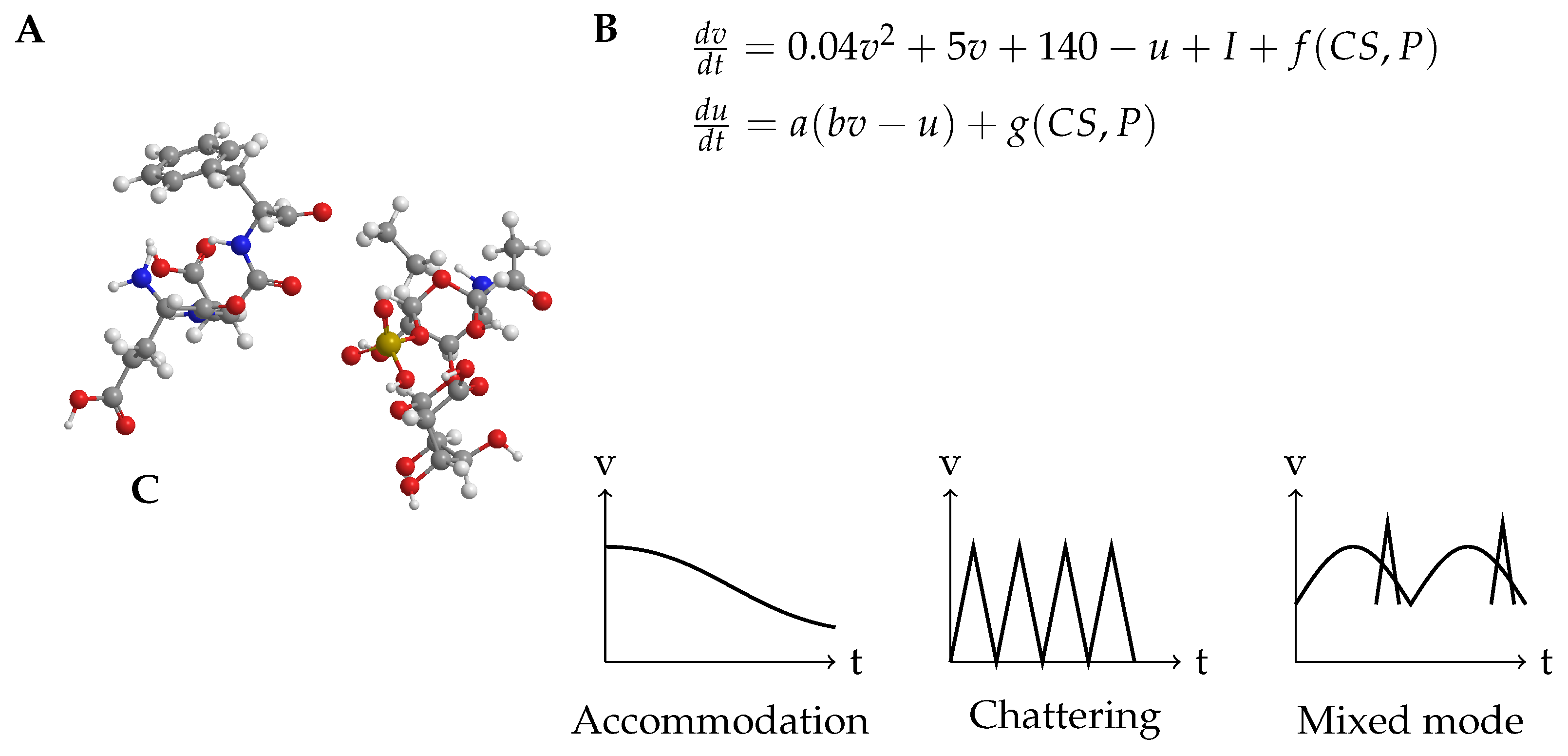

1. Introduction

- Induced excitability: Neuronal amplification is the process by which a neurone becomes more readily activated as a result of previous stimulation [11]. We investigate the potential impact of CS-proteinoid mixtures on the threshold for induced excitability.

- Phasic spiking:An firing pattern that is distinguished by a solitary spike at the beginning of stimulus [13]. We examine the potential of CS-proteinoid mixtures to regulate the shift from phasic to tonic firing patterns.

2. Materials and Methods

Synthesis of Chondroitin Sulfate-Proteinoid Mixture

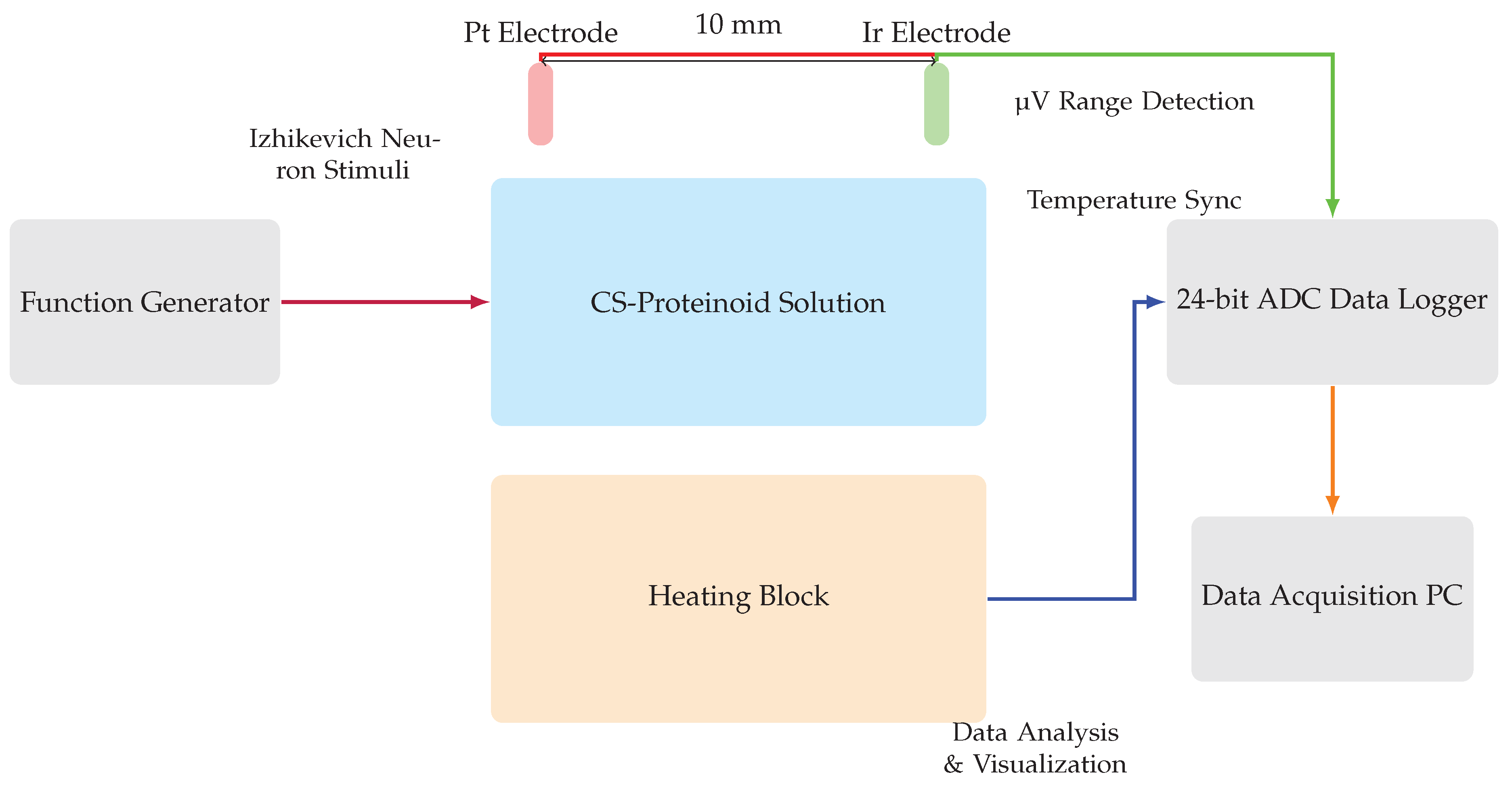

Electrochemical Characterization Apparatus

3. Results

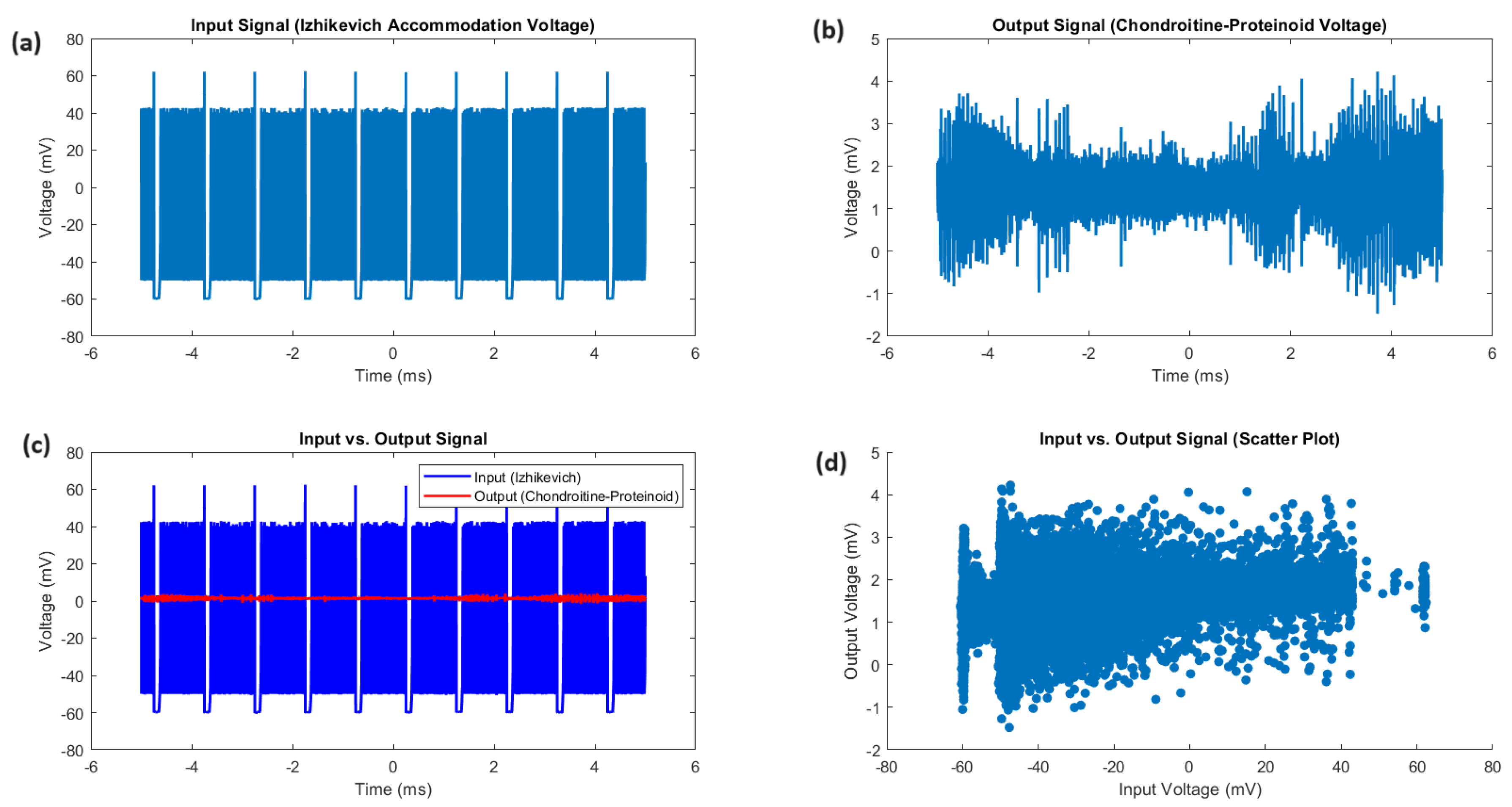

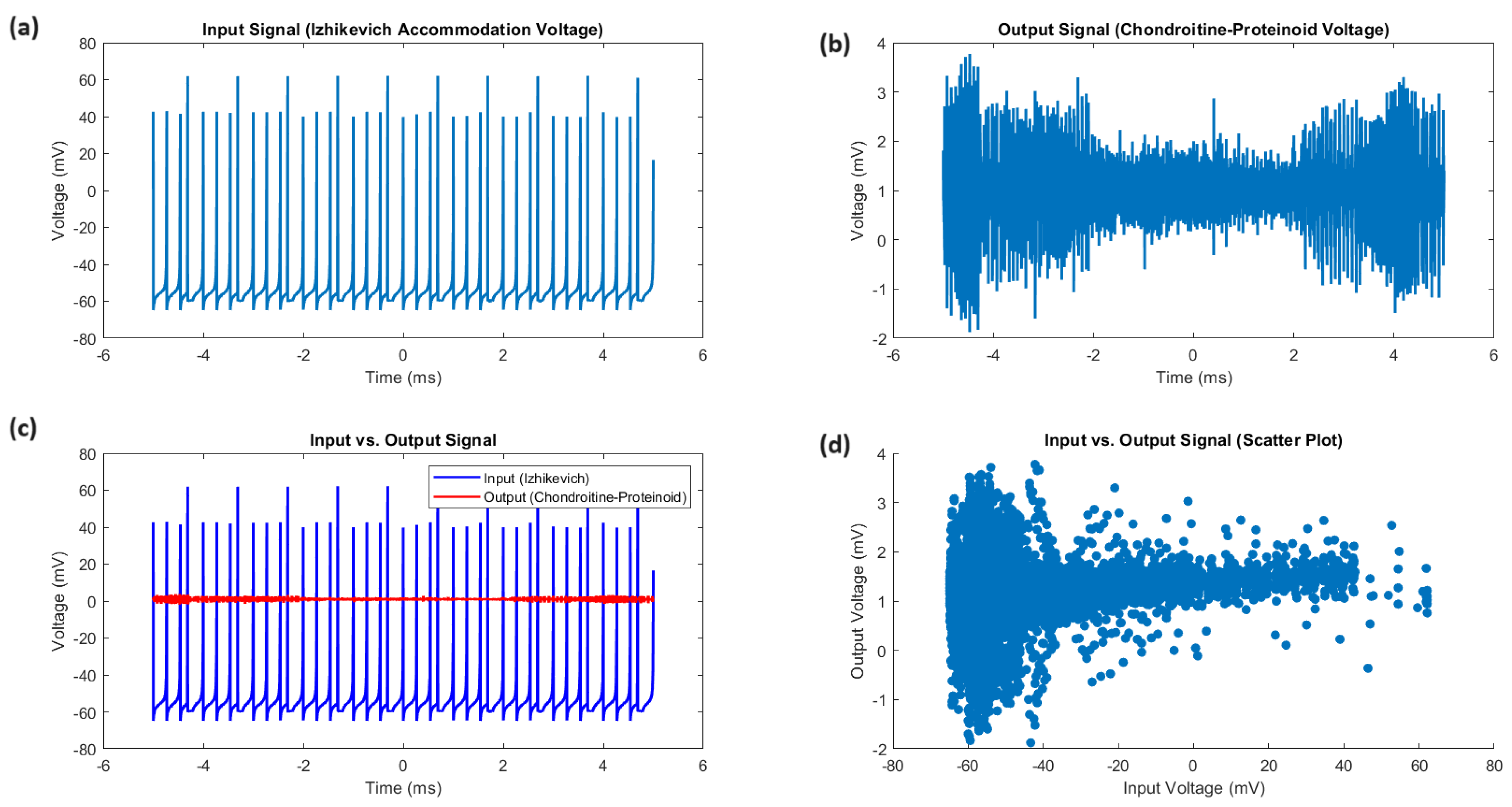

3.1. Accommodation Spike Analysis of Proteinoid-Chondroitine Sample

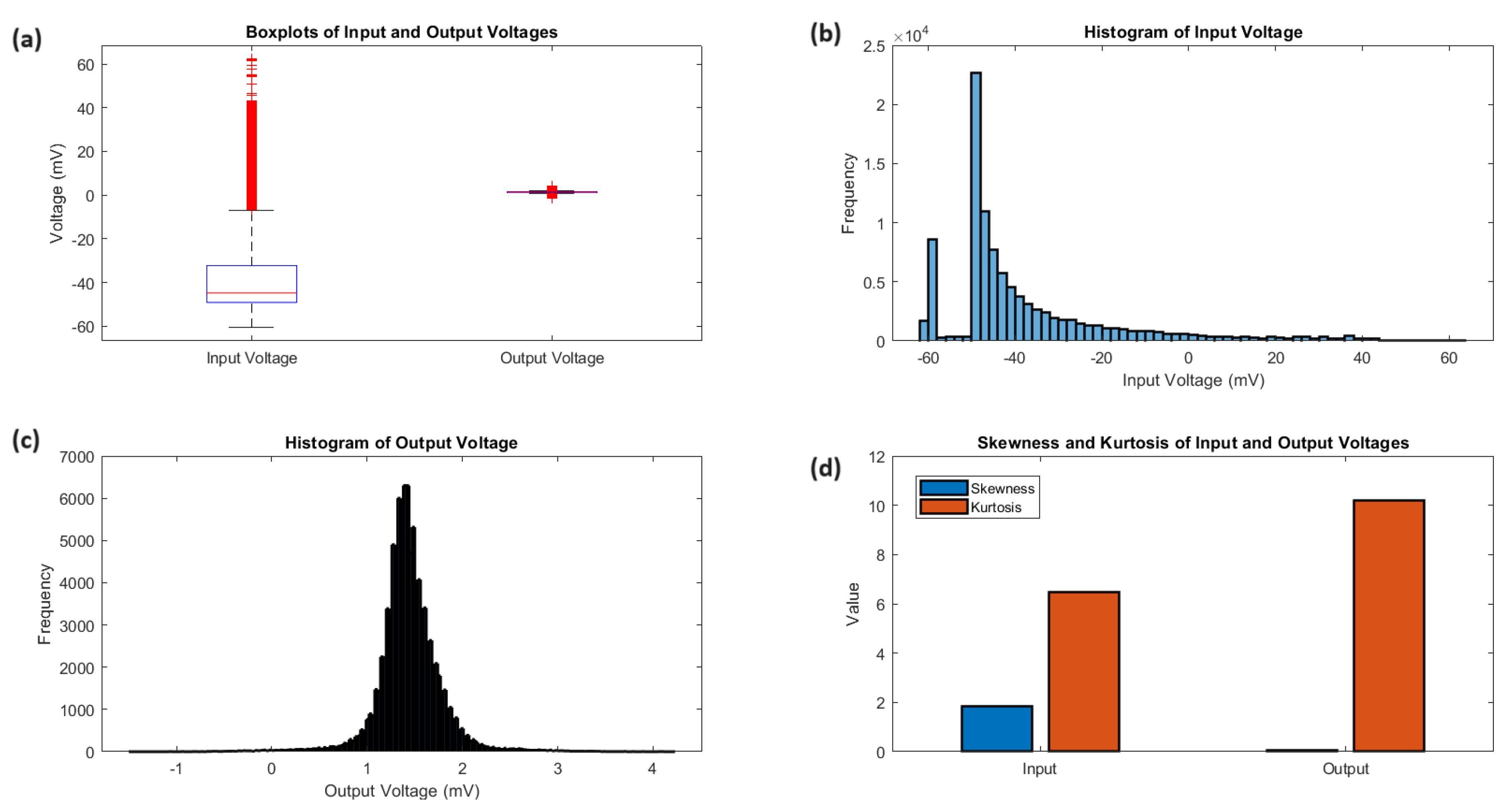

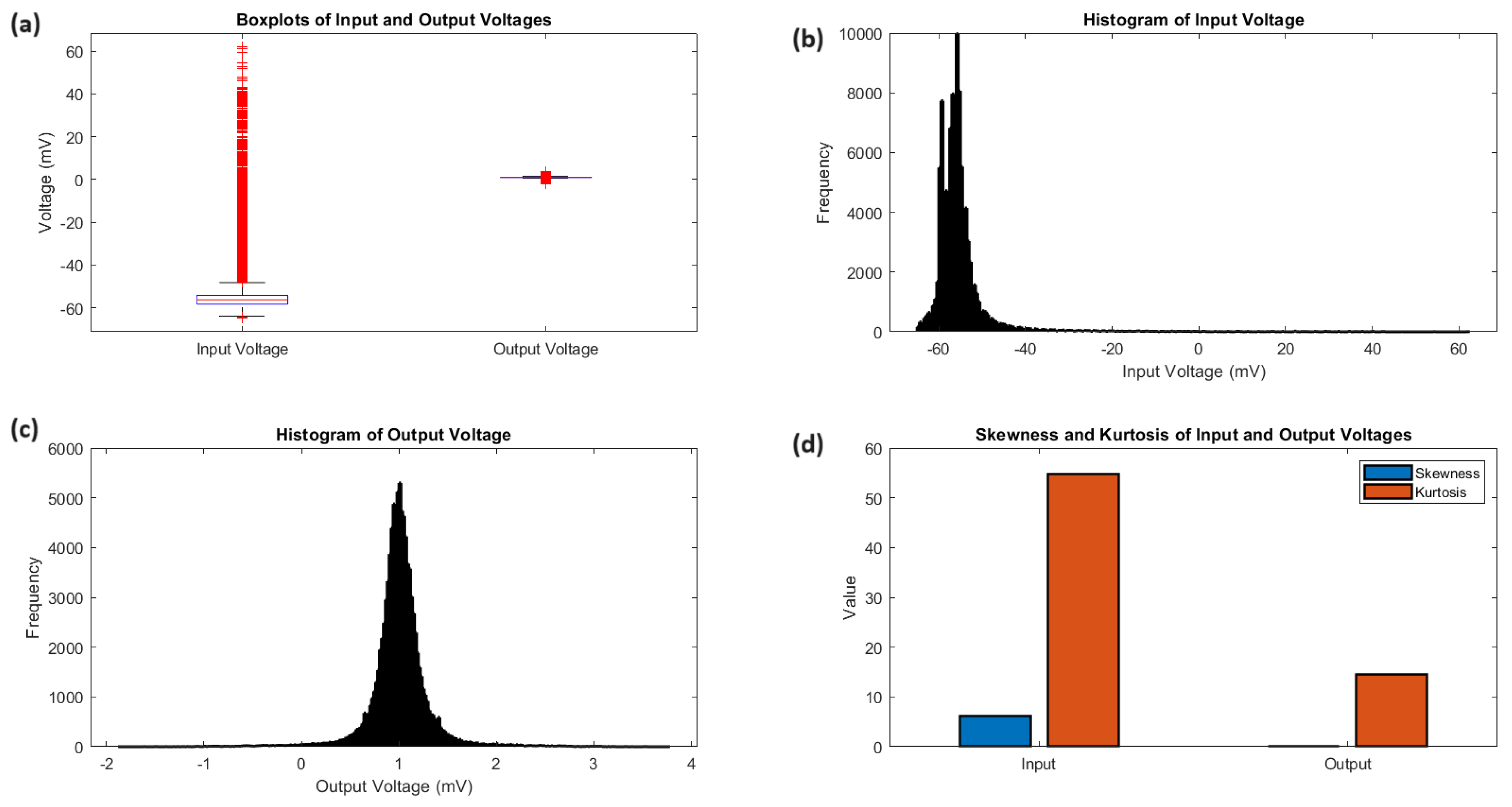

3.1.1. Statistical Analysis of Input and Output Voltages

3.1.2. Mechanisms and Implications

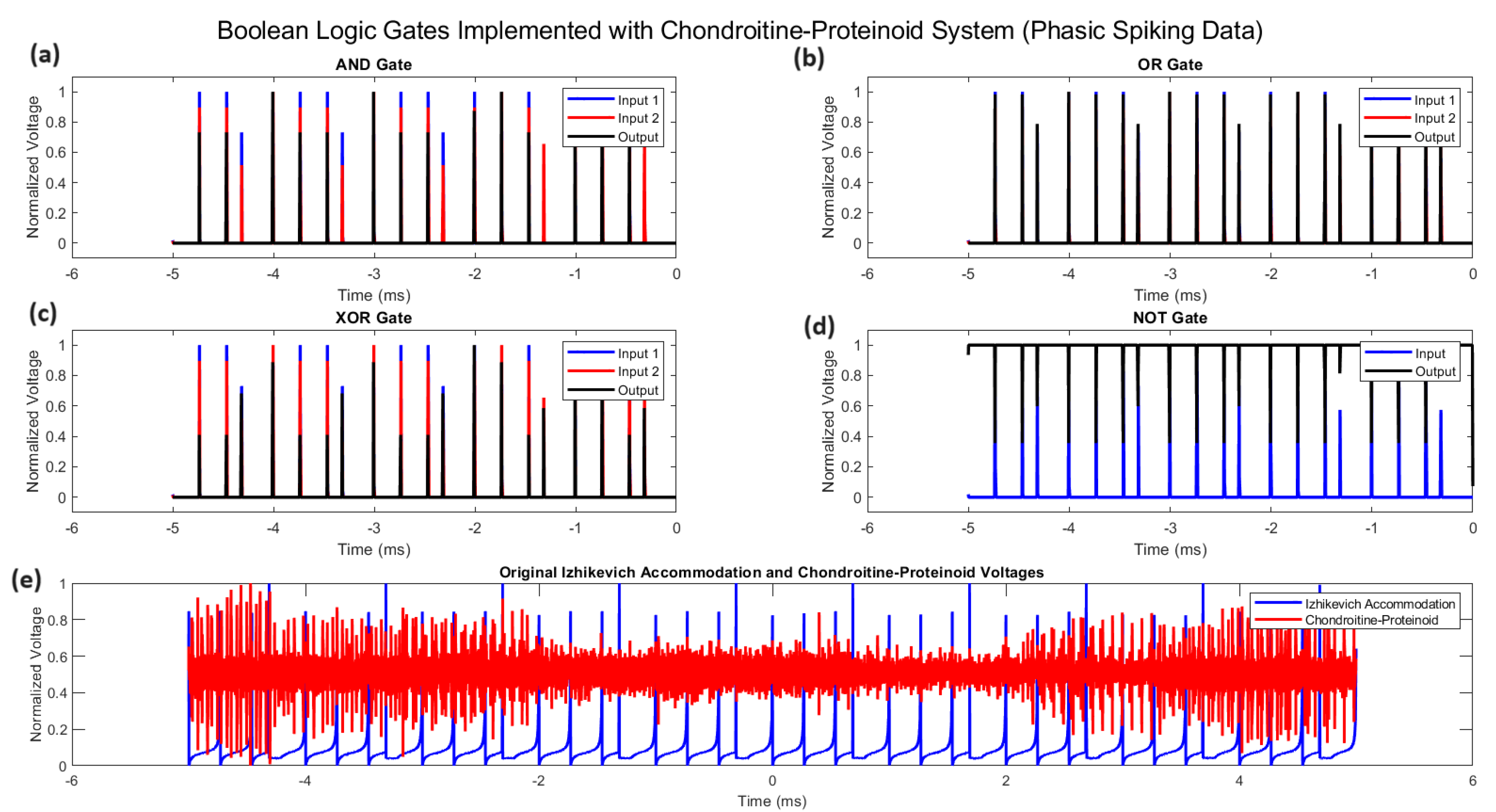

3.2. Analytical Response of Chondroitine-Proteinoid to Phasic Spiking Stimulus

| Measure | Input (mV) | Output (mV) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean voltage | 1.01 | |

| Standard deviation | 8.23 | 0.30 |

| Median voltage | 1.00 | |

| Interquartile range (IQR) | 4.01 | 0.22 |

| Range | 127.06 | 5.65 |

| Skewness | 6.11 | 0.02 |

| Kurtosis | 54.73 | 14.58 |

3.2.1. Input-Output Transformation

3.2.2. Phasic Spiking Mechanism

3.3. Statistical Characteristics

3.3.1. Boolean Logic Implementation in Chondroitine-Proteinoid Systems

- OR Gate:

- XOR Gate:

- NOT Gate:

3.3.2. Gate Accuracies and Performance Metrics

- The inherent noise and variability in the biological system may present challenges. The chondroitine-proteinoid system is a highly complex biological entity, and its response to input stimuli may not always be completely consistent or predictable. The accuracy of the implemented logic gates can be affected by this intrinsic noise.

- Considering the selection of threshold values: The accuracy of the logic gates relies on selecting the right threshold values for input spike generation and output response. Threshold values that are not optimal can result in misclassifications and decreased accuracy.

- The logic operation is quite complex. Certain logic operations, such as XOR, are comparatively more complex than others, such as AND or OR. The heightened complexity could require a greater level of precision in managing the system’s reaction, posing a challenge within a biological context.

3.3.3. Spike Rates and Energy Efficiency

3.3.4. Implications for Unconventional Computing

3.4. Functional Implications

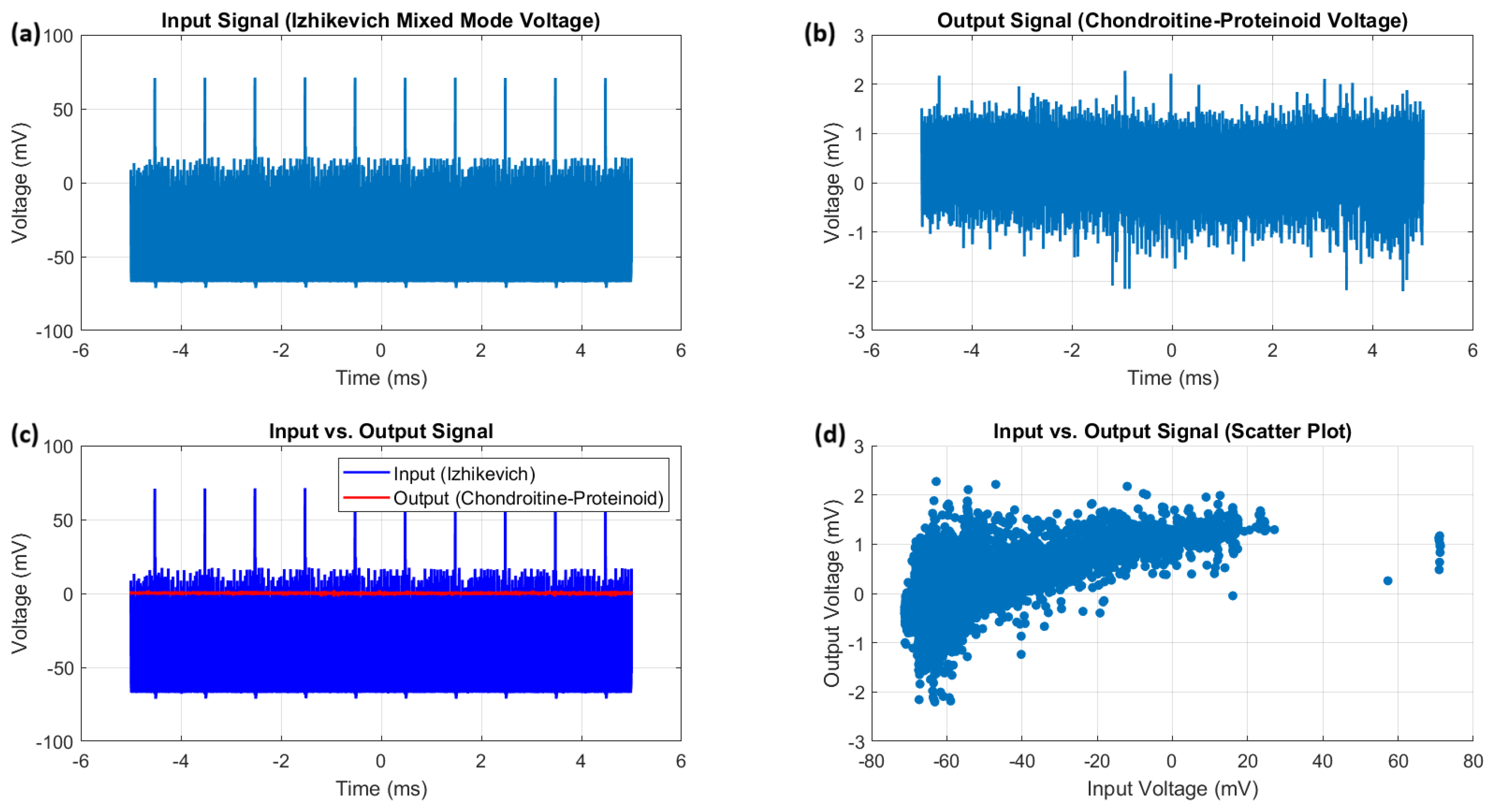

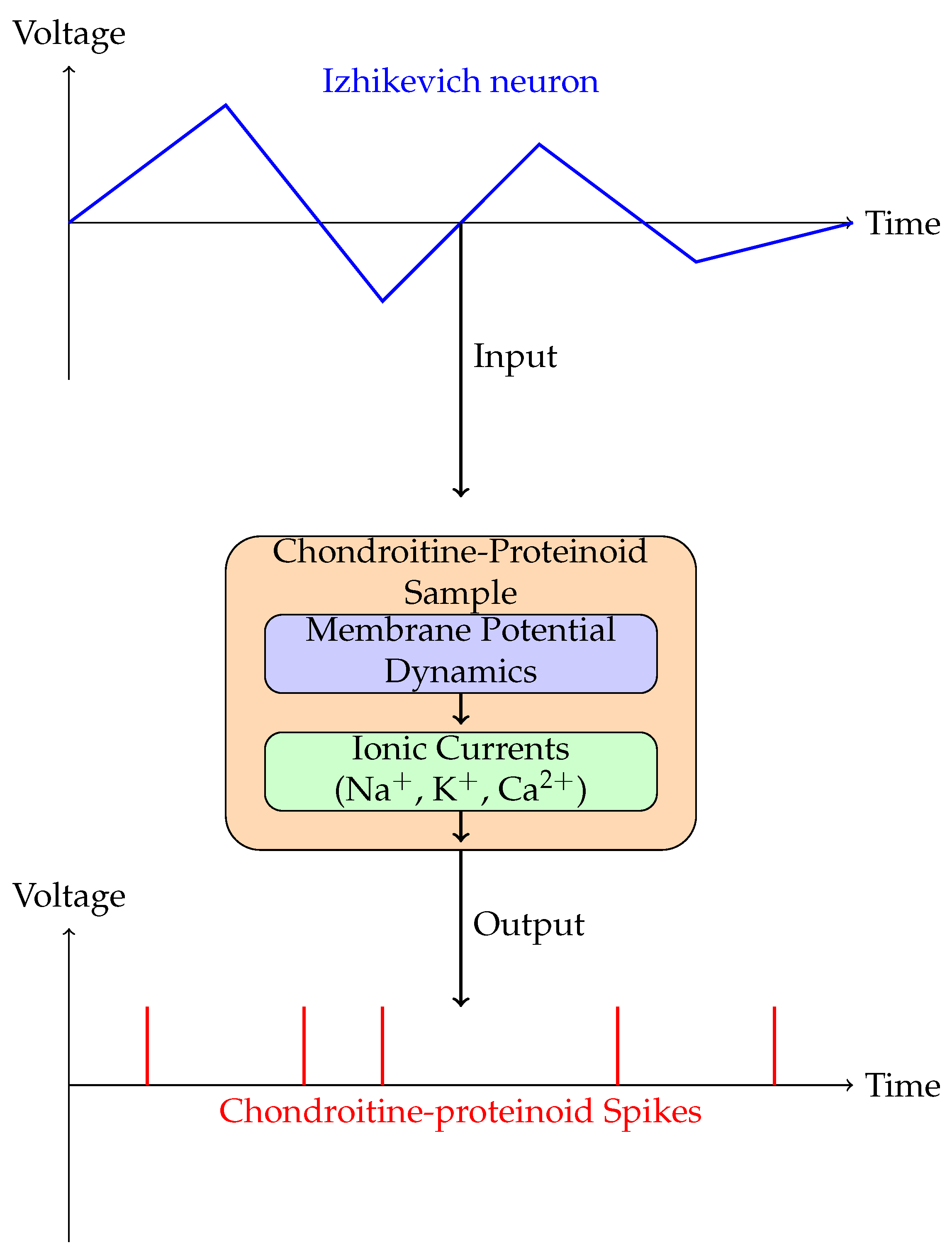

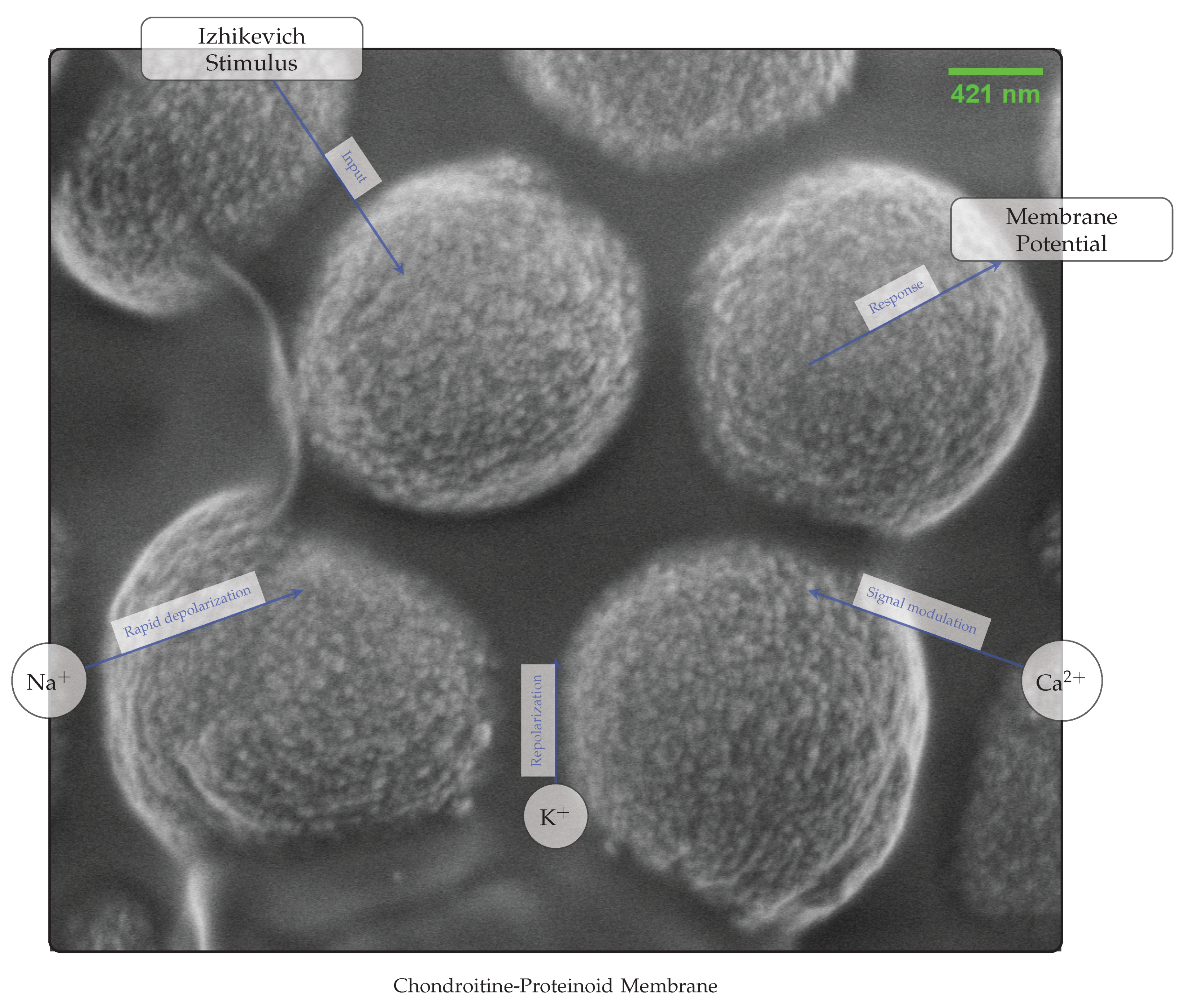

3.5. Mixed Mode Response of Proteinoid-Chondroitine Sample to Izhikevich Voltage Input

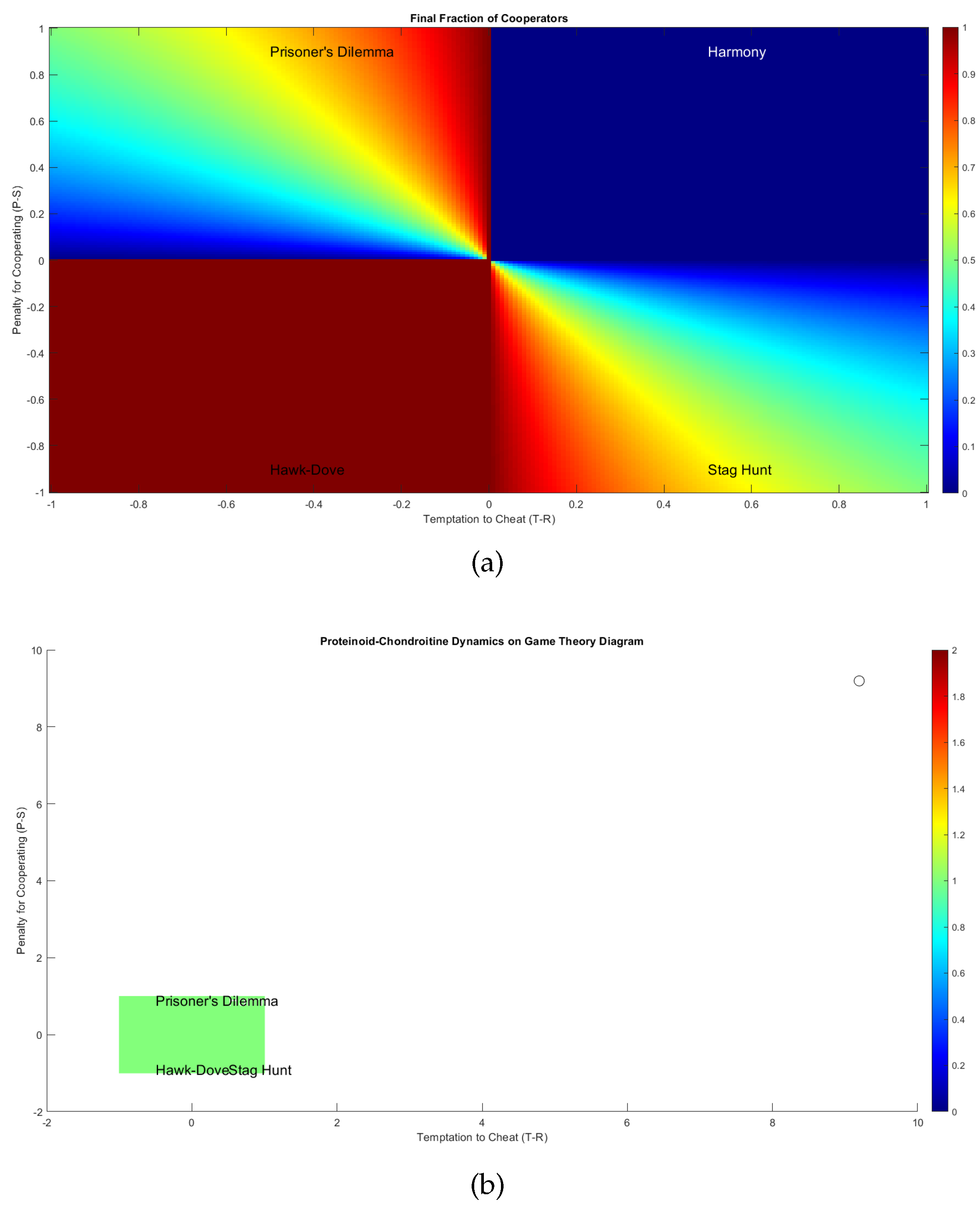

3.6. Game Theoretical Analysis of Proteinoid-Chondroitine Interactions

- Harmony: Cooperation is the dominant strategy, and the population reaches a stable equilibrium consisting primarily of cooperators.

- Hawk-Dove: A mix of cooperative and defective strategies coexist in the population, leading to a stable equilibrium with a certain proportion of cooperators and defectors.

- Stag Hunt: The outcome depends on the initial conditions, with the population converging towards either a cooperative or defective equilibrium.

- Prisoner’s Dilemma: Defection is the dominant strategy, and the population eventually reaches a stable equilibrium consisting mainly of defectors.

4. Discussion

4.1. Membrane Potential Dynamics and Ionic Mechanisms in Chondroitine-Proteinoid Response to a Stimulus from Izhikevich Neuron

4.2. Neuromorphic Properties and Burst-like Dynamics of Chondroitine-Proteinoid System: Implications for Bio-Inspired Computing

4.3. Biased Logic Operations and Reservoir Computing

4.4. Energy Efficiency and Neuromorphic Computing

4.5. Analog Computation and Noise Tolerance

4.6. Parallel Processing and Scalability

4.7. Future Directions

- Investigating advanced computational tasks, such as pattern recognition or time series prediction, use the chondroitin-proteinoid system as a computational reservoir.

- Exploring the system’s capacity for learning and adapting. Is it possible to adjust or train the system’s characteristics in order to enhance its performance on particular tasks?

- Creating hybrid systems that integrate the distinctive characteristics of the chondroitin-proteinoid system with conventional electrical components, which could potentially result in novel designs for neuromorphic computing.

- Investigating the system’s computational features for long-term stability and reproducibility, which is essential for practical implementations.

- Investigating the capabilities of this system in the growing area of biocomputing, which involves using biological components to carry out computations inside living organisms [47].

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Izhikevich, E.M. Resonate-and-fire neurons. Neural networks 2001, 14, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, J.; Warren, P.; Fawcett, J. Chondroitin sulfate: a key molecule in the brain matrix. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 2012, 44, 582–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galtrey, C.M.; Fawcett, J.W. The role of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans in regeneration and plasticity in the central nervous system. Brain research reviews 2007, 54, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dityatev, A.; Schachner, M. Extracellular matrix molecules and synaptic plasticity. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2003, 4, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandtlow, C.E.; Zimmermann, D.R. Proteoglycans in the developing brain: new conceptual insights for old proteins. Physiological reviews 2000, 80, 1267–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Katagiri, Y.; McCann, T.E.; Unsworth, E.; Goldsmith, P.; Yu, Z.X.; Tan, F.; Santiago, L.; Mills, E.M.; Wang, Y.; others. Chondroitin-4-sulfation negatively regulates axonal guidance and growth. Journal of cell science 2008, 121, 3083–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.W.; Harada, K. Thermal copolymerization of amino acids to a product resembling protein. Science 1958, 128, 1214–1214. [Google Scholar]

- Izhikevich, E.M. Simple model of spiking neurons. IEEE Transactions on neural networks 2003, 14, 1569–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benda, J.; Herz, A.V. A universal model for spike-frequency adaptation. Neural computation 2003, 15, 2523–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.M.; McCormick, D.A. Chattering cells: superficial pyramidal neurons contributing to the generation of synchronous oscillations in the visual cortex. Science 1996, 274, 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Henze, D.; Buzsáki, G. Action potential threshold of hippocampal pyramidal cells in vivo is increased by recent spiking activity. Neuroscience 2001, 105, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupa, M.; Popović, N.; Kopell, N. Mixed-mode oscillations in three time-scale systems: a prototypical example. SIAM Journal on Applied Dynamical Systems 2008, 7, 361–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, S.A.; De Koninck, Y.; Sejnowski, T.J. Biophysical basis for three distinct dynamical mechanisms of action potential initiation. PLoS computational biology 2008, 4, e1000198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, A.; Chammah, A.M. Prisoner’s dilemma: A study in conflict and cooperation; Vol. 165, University of Michigan press, 1965.

- Axelrod, R.; Hamilton, W.D. The evolution of cooperation. science 1981, 211, 1390–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.A.; May, R.M. Evolutionary games and spatial chaos. nature 1992, 359, 826–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.A. Five rules for the evolution of cooperation. science 2006, 314, 1560–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, A. Prisoner’s dilemma—recollections and observations. In Game Theory as a Theory of a Conflict Resolution; Springer, 1974; pp. 17–34.

- Axelrod, R. The evolution of cooperation Basic Books. New York 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, M.A. Evolutionary dynamics: exploring the equations of life; Harvard university press, 2006.

- Cordero, O.X.; Polz, M.F. Explaining microbial genomic diversity in light of evolutionary ecology. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2014, 12, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basanta, D.; Deutsch, A. A game theoretical perspective on the somatic evolution of cancer. In Selected Topics in Cancer Modeling: Genesis, Evolution, Immune Competition, and Therapy; Springer, 2008; pp. 1–16.

- Schuster, S.; Kreft, J.U.; Schroeter, A.; Pfeiffer, T. Use of game-theoretical methods in biochemistry and biophysics. Journal of biological physics 2008, 34, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrett, R.; Levin, S. The importance of being discrete (and spatial). Theoretical population biology 1994, 46, 363–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohl, K.; Hummert, S.; Werner, S.; Basanta, D.; Deutsch, A.; Schuster, S.; Theißen, G.; Schroeter, A. Evolutionary game theory: molecules as players. Molecular BioSystems 2014, 10, 3066–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantazopoulos, H.; Berretta, S. In sickness and in health: perineuronal nets and synaptic plasticity in psychiatric disorders. Neural plasticity 2016, 2016, 9847696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, H.; Freeman, C.; Jacobson, G.A.; Small, D.H. Proteoglycans in the central nervous system: role in development, neural repair, and Alzheimer’s disease. IUBMB life 2013, 65, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, G.; Vyawahare, S.; Austin, R.H. Bacteria and game theory: the rise and fall of cooperation in spatially heterogeneous environments. Interface focus 2014, 4, 20140029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, P.E.; Chao, L. Prisoner’s dilemma in an RNA virus. Nature 1999, 398, 441–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, E.R.; Schwartz, J.H.; Jessell, T.M.; Siegelbaum, S.; Hudspeth, A.J.; Mack, S. ; others. Principles of neural science; Vol.4,McGraw-hillNewYork,2000. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hille, B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes Third Edition. (No Title).

- Izhikevich, E.M. Dynamical systems in neuroscience; MIT press, 2007.

- Hodgkin, A.L.; Huxley, A.F. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. The Journal of physiology 1952, 117, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izhikevich, E.M.; Desai, N.S.; Walcott, E.C.; Hoppensteadt, F.C. Bursts as a unit of neural information: selective communication via resonance. Trends in neurosciences 2003, 26, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisman, J.E. Bursts as a unit of neural information: making unreliable synapses reliable. Trends in neurosciences 1997, 20, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahe, R.; Gabbiani, F. Burst firing in sensory systems. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2004, 5, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Qiu, J. Neuromorphic Computing in Sensory Systems: A Review. Journal of Neuromorphic Intelligence 2024, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Shi, Z.; Ma, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q. Recent advances on crystalline materials-based flexible memristors for data storage and neuromorphic applications. Science China Materials 2022, 65, 2110–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soman, S.; Suri, M. Recent trends in neuromorphic engineering. Big Data Analytics 2016, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, K. Physical reservoir computing—an introductory perspective. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics 2020, 59, 060501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Alvarez, A.; Higuchi, R.; Sanz-Leon, P.; Marcus, I.; Shingaya, Y.; Stieg, A.Z.; Gimzewski, J.K.; Kuncic, Z.; Nakayama, T. Emergent dynamics of neuromorphic nanowire networks. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 14920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.; Jaiswal, A.; Panda, P. Towards spike-based machine intelligence with neuromorphic computing. Nature 2019, 575, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indiveri, G.; Linares-Barranco, B.; Hamilton, T.J.; Schaik, A.v.; Etienne-Cummings, R.; Delbruck, T.; Liu, S.C.; Dudek, P.; Häfliger, P.; Renaud, S.; others. Neuromorphic silicon neuron circuits. Frontiers in neuroscience 2011, 5, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpeshkar, R. Analog synthetic biology. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2014, 372, 20130110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, M.D.; Abbott, D. What is stochastic resonance? Definitions, misconceptions, debates, and its relevance to biology. PLoS computational biology 2009, 5, e1000348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merolla, P.A.; Arthur, J.V.; Alvarez-Icaza, R.; Cassidy, A.S.; Sawada, J.; Akopyan, F.; Jackson, B.L.; Imam, N.; Guo, C.; Nakamura, Y.; others. A million spiking-neuron integrated circuit with a scalable communication network and interface. Science 2014, 345, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozinger, L.; Amos, M.; Gorochowski, T.E.; Carbonell, P.; Oyarzún, D.A.; Stoof, R.; Fellermann, H.; Zuliani, P.; Tas, H.; Goñi-Moreno, A. Pathways to cellular supremacy in biocomputing. Nature communications 2019, 10, 5250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measure | Input (mV) | Output (mV) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean voltage | 1.44 | |

| Standard deviation | 20.55 | 0.33 |

| Median voltage | 1.42 | |

| Interquartile range (IQR) | 16.92 | 0.31 |

| Range | 123.05 | 5.70 |

| Skewness | 1.84 | 0.06 |

| Kurtosis | 6.48 | 10.20 |

| Measure | Input (mV) | Output (mV) |

|---|---|---|

| Voltage range | to 71.25 | to 2.27 |

| Mean voltage | ||

| Median voltage | ||

| Standard deviation | 9.42 | 0.32 |

| Skewness | 4.08 | 1.22 |

| Kurtosis | 27.18 | 6.70 |

| Correlation coefficient | 0.71 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).