1. Introduction

Lake eutrophication is a major problem to be solved urgently in the global water environment (Yang et al. 2020; Tan et al. 2017). In China, more than 60% of lakes have eutrophication problems, and more than 50% of the lakes’ nitrogen and phosphorus originate from non-point source pollution (Hou et al. 2021). Most studies suggested that nutrient loss in water from farmland is a key factor causing water eutrophication when the high nutrient concentration is carried by farmland runoff (Yang et al. 2020; Xia et al. 2020). Xue et al. (2020) suggested that water quality was mainly attributed to pollutant load from agricultural fields. Li et al. (2021) suggested that agricultural land, including the paddy fields and uplands, was positively correlated with various forms of nutrients. In recent years, the Lake Basin of Yunnan has faced the ecological environment problem of increasing eutrophication risk with the rapid enhancing of nitrogen of pollution due to the nitrogen forms fertilizer input from farmland, and increased runoff into river and lake basins (Husain et al 2019). It is very serious to affecting the ecological environment and threatens the safety of drinking water for human survival (Barcellos et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2019). Thus, it is urgent and of great significance to effectively prevent and reduce nitrogen of pollution, an agricultural non-point source pollution, from farmland by and protect water resources and ecological security (Tang et al. 2020).

Most studies suggested that nitrogen pollution caused from nitrogen fertilizer application into lake basins, has caused more than 60% of water pollution (Bhambri et al. 2020; Javier, et al. 2021). A series of studies focused on nitrogen reduction and degradation measures in water bodies and attracted wide attention in water resource research and environmental management (Zhang et al. 2019). Hou et al. (2021) suggested that teatments controlled release fertilizer application, conventional urea and conventional urea as environmental fertilizer were observed 29%, 47%, and 46%, respectively lower in TN loading to the surface and percolating water than the conventional fertilizer practice. For the agricultural production, nitrogen fertilizer application is an important measure to increase crop yield when the fertilizer is added to the soil layer (Diao et al. 2020; Hou et al. 2021). In recent decades, large amounts of nitrogen fertilizer have increased crop yields to assure national food security (Cai et al. 2009; Husain et al. 2019). However, the unreasonable and continuous input of nitrogen fertilizer leads to the loss of nitrogen nutrients from farmland, releases a large amount of surplus nitrogen pollutants to the environment, increases the risk of eutrophication in water bodies, and seriously affects the ecological environment (Cai et al. 2009; Lu et al. 2005). Therefore, scientific nitrogen fertilization application is an important measure to reduce agricultural nitrogen nutrient loss in terms of surface runoff and infiltration and is an effective method to reduce non-point source pollution in lake basins (Zhang et al. 2020).

Nitrogen, including ammonium nitrogen and nitrate nitrogen, causing the rapid reproduction of algae and other plankton and decreasing dissolved oxygen in water, resulting in water pollution (Monchamp et al. 2014). When rainfall occurs, rainwater collects in surface runoff water and infiltrated groundwater. Through physical and chemical circulation, nitrogen in rainwater enters river and lake drainage areas in the form of ammonium nitrogen and nitrate nitrogen (Zhao et al. 2018). Indicating that different nitrogen forms of water are important factors for the eutrophication of water bodies and the aggravation of non-point source pollution in lake basins (Lu et al. 2014). Studies have shown that nitrate is the main cause of lake water pollution (Arunothai et al. 2008). A study showed that the nitrate/ammonium ratio can affect the growth of algae and other plankton by affecting the nutrient structure of river and lake basins (Monchamp et al. 2018). Therefore, it is an important environmental problem that should be paid attention to in agricultural production to reduce nitrogen loss and the pollution load of the water environment by changing the type of nitrogen fertilizer (Ying et al. 2017).

The root system is an important organ for crops to absorb nutrients, and many studies have shown that a good root system is a prerequisite for a high yield of crops (Kristian et al. 2011). The reason is that root growth and development (such as root length, root surface area, root tip number, root activity, and other morphological and physiological indicators) are affected by the nitrogen form in the soil environment, which is an important factor that determines the nitrogen absorption ability of roots (Elsalam et al. 2021). Many results showed that a single application of nitrate-nitrogen or ammonium nitrogen inhibited root elongation and growth (Pan et al. 2017; Chen et al. 2017). In contrast, a combined application of nitrate and ammonium nitrogen promoted root growth (Chen et al. 2019; Kurt et al. 2021; Xu et al. 2021). The results showed that root growth was affected by nitrogen form and nitrogen use efficiency. However, knowledge of the response of crop roots to nitrogen forms for the protection of water resources and ecological security is still lacking and is of great significance.

Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) is one of the main cash crops in Yunnan, such as the Honghe watershed and the Fuxian Lake Basin (Kakar et al. 2020). Nitrogen fertilizer including ammonium nitrogen and nitrate nitrogen is applied to improve tobacco plant growth and increase tobacco yield (Zia et al. 2020). The problem is that different forms of nitrogen fertilizer will inevitably affect the ecological environment of a watershed, so how to effectively control water pollution in the watershed and guarantee the quality of tobacco is an important issue in these regions (Xu et al. 2016). Indicating that many studies have focused on crops' absorption and utilization of nitrogen forms (nitrate and ammonium) and their effects on tobacco plant growth (Hessini et al. 2019; Suyala et al. 2017). It remains unclear whether different forms of nitrogen fertilizer can reduce nitrogen loss in lake basins and ensure tobacco yield and quality.

Based on this, in this study, we collected runoff in real-time and infiltration water samples during tobacco plant growth in the Honghe watershed and the Fuxian Lake Basin to study the effect of different forms of nitrogen fertilizer on the soil environment to protect water quality and ensure tobacco farmers' income.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

The experiment was conducted from April to September 2020 in the Mile and Chengjiang Counties of Yunnan. The experimental site of Mile County was located in the basin of Red River (103 45 '46"E, 24 37' 34"N, 1451 m a. s. l.), which has a south-central subtropical or mid-subtropical monsoon climate with an average annual temperature of 19.7°C, annual rainfall of 800–1100 mm and annual sunshine duration of 2176 h. The experimental site of Chengjiang is located in the basin of Fuxian Lake, (102°52′39″E, 24°38′29″N, 1767 m a.s.l.), which has a subtropical plateau monsoon climate with an average annual temperature of 17.5°C and an average annual rainfall of 900–1200 mm. The total sunshine duration is 2172 h, and the sunshine rate is 50%. The soil is red soil in Mile County and Paddy soil in Chengjiang County (Chinese Classification system). The soil nutrients before the tobacco was transplanted are shown in

Table 1.

2.2. Experimental Design

Five nitrogen fertilizer treatments were used i.e., 100–0% nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer treatment (T1), 75–25% nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer treatment (T2), 50–50% nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer treatment (T3), 25–75% nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer treatment (T4), and 0–100% nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer treatment (T5). Each treatment was replicated three times in a randomized complete block design (RCBD). Each plot was set up with a collection tank at the bottom of the plot.

At the two field experimental sites, the variety K326 of flue-cured tobacco was used it is widely planted in the regions of Yunnan. The plot size was 12 × 3.6 m2, and the plant row spacing was 1.2 m × 0.6 m, resulting in a density of 13,890 plant ha-1 when the tobacco seedlings were transplanted into the soil at the two field experimental sites. The total amount of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium fertilizer in each treatment was the same, and the fertilizer was applied as follows: 75 kg∙ha−1 annual nitrogen (N) application rate (pure N), 75 kg∙ha−1 phosphorus (P) application rate (P2O5) and 150 kg∙ha−1 potassium (K) application rate (K2O) before the tobacco seedlings were transplanted. The N fertilizer input was applied according to the form of the nitrogen fertilizer, shown in

Table 2. All fertilizer was provided by a local tobacco company. The cultivation management practices were carried out following local high-quality tobacco production protocols.

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Water Sample Collection and Measurement

In a field experiment, runoff and infiltration are important parameters for evaluating nitrogen loss. A water collection tank was installed to collect runoff and infiltration in each plot, which were described by Zhao (2017). After rainfall, water samples were collected in each plot when runoff and infiltration were generated at the experimental sites. Water depth was measured per plot to evaluate the runoff amount after each rainfall event, and the harvested runoff amount was calculated by multiplying by the plot area. Then, water samples (500 ml) were collected using collection bottles and were taken to the laboratory to be stored in a refrigerator at 4°C for measuring total nitrogen, nitrate nitrogen, and ammonium nitrogen in the water. The measurements were conducted following the national standard using the alkaline potassium persulfate digestion method to determine total nitrogen, a UV spectrophotometer to determine nitrate nitrogen, and the alkaline potassium persulfate digestion method to determine ammonium nitrogen. The nitrogen loss was calculated by the water volume is multiplied by the concentration, and convert the yield loss per hectare.

2.3.2. Biomass and Root Index of Tobacco

At the two field experimental sites, the biomass of tobacco was used to extrapolate the yield per unit ground area in each plot. When tobacco plants were picked (90 d after transplanting), four plants were randomly selected and cut at the ground level in each plot; the roots, stems, and leaves of tobacco were separated, weighed fresh, oven-dried at 80°C to a constant weight and weighed separately to determine the dry matter weight.

When tobacco plants were picked (90 d after transplanting), four plants were randomly selected to observe the root spatial distribution in each plot. The method was determined by the "3D monolith" stratified spatial sampling method, which was described by Booij (2016). That is, a small cubic in situ root and soil sampler was used to sample the roots of tobacco; nine soil blocks were taken in each layer centered on the tobacco plant; soil blocks with a volume of 10 cm × 10 cm × 20 cm were sampled; and a total of 27 root samples were collected in each plant. The root samples were used to measure the root morphological parameters such as the root length density and root surface area. The root length density and root surface area were measured using a root scanning system (Win RHIZO, Canada, REGENT).

2.4. Data Analysis

All metrics were statistically analyzed, and ANOVA was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0. ANOVA was performed using the LSD method for one-way comparisons. The significance level was P < 0.05 for all analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Nitrogen Loss from Tobacco Fields with Different Forms of Nitrogen Fertilizer

3.1.1. Characteristics of Nitrogen Loss in Runoff from Tobacco Fields with Different Forms of Nitrogen Fertilizer

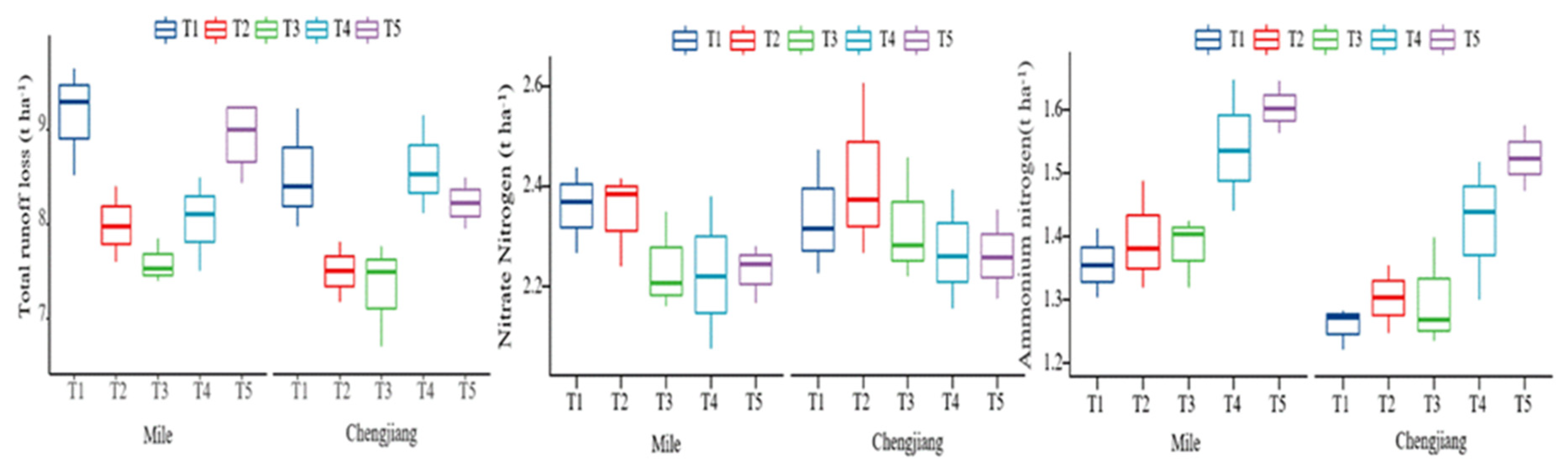

The characteristics of nitrogen loss in runoff from tobacco fields with different forms of nitrogen fertilizer are shown in

Figure 1. Nitrogen loss in runoff in the T2 and T3 treatments was significantly lower than that in the T1, T4, and T5 treatments in terms of the total nitrogen, nitrate-nitrogen, and ammonium-nitrogen contents in the two field experiments.

At the Chengjiang experimental site, the total nitrogen loss in runoff was characterized by the order T1 > T4 > T5 > T3 > T2 during the experimental periods. That is, total nitrogen loss in runoff in the T2 and T3 treatments was significantly lower than that in the T1, T4, T5 treatments (P < 0.05), but the difference between the T2 and T3 treatments was not significant (P > 0.05). Nitrate-nitrogen loss in runoff was ranked in the order T2 > T1 > T3 > T4 > T5. Nitrate-nitrogen loss in runoff in the T2 and T1 treatments was significantly lower than that in the T3, T4, and T5 treatments (P < 0.05), but there were no significant differences among the T4, T3, and T5 treatments (P > 0.05). Ammonium-nitrogen loss in runoff was ranked in the order T5 > T4 > T2 > T3 > T1. Ammonium-nitrogen loss in runoff in the T4 and T5 treatments was significantly higher than that in the T3, T2, and T1 treatments (P < 0.05), but there were no significant differences among the T3, T2, and T1 treatments (P > 0.05).

At the Mile experimental site, the total nitrogen loss in runoff was characterized by the order T5 > T1 > T4 > T2 > T3 during the experimental periods. Total nitrogen loss in runoff in the T2, T3, and T4 treatments was significantly lower than that in the T1 and T5 treatments (P < 0.05), but there were no significant differences among the T4, T3, and T5 treatments (P > 0.05). Nitrate-nitrogen loss in runoff was ranked in the order T1 > T2 > T4 > T3 > T5. Nitrate-nitrogen loss in runoff in the T1 and T2 treatments was significantly higher than that in the T3, T4, and T5 treatments (P < 0.05), but there were no significant differences among the T4, T3, and T5 treatments (P > 0.05). Ammonium-nitrogen loss in runoff was ranked in the order T5 > T4 > T2 > T3 > T1. Ammonium-nitrogen loss in runoff in the T4 and T5 treatments was significantly higher than that in the T3, T2, and T1 treatments (P < 0.05), but there were no significant differences among the T3, T2, and T1 treatments (P > 0.05).

The results from the two experimental sites suggested that 50–50% nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer resulted in a lower total nitrogen loss, which may contribute to promoting the root growth of tobacco plants and the absorption of soil nutrients.

3.1.2. Characteristics of Nitrogen Loss Due to Infiltration from Tobacco Fields with Different Forms of Nitrogen Fertilizer

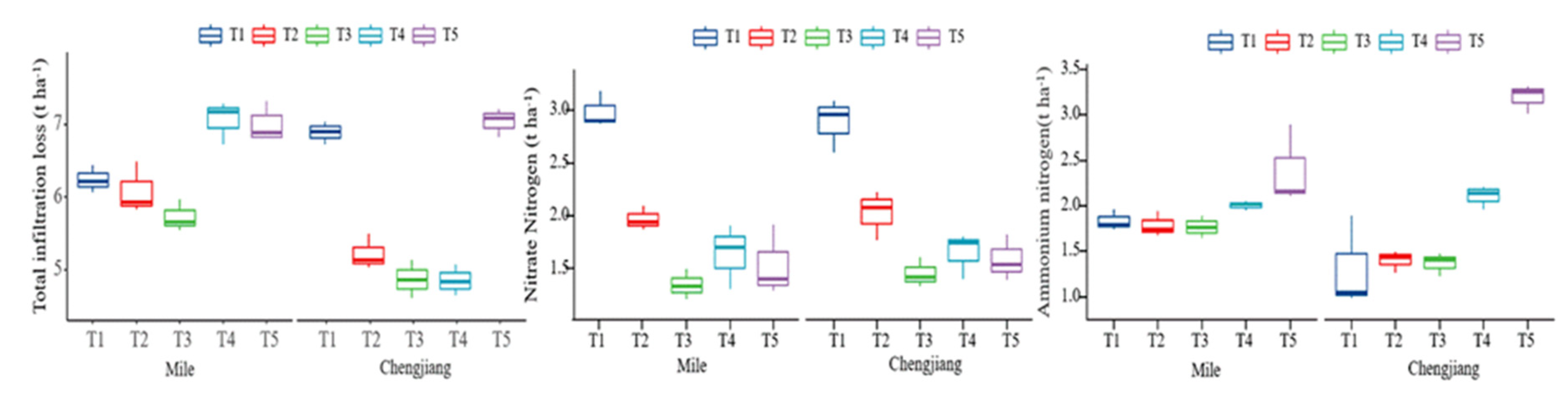

The characteristics of nitrogen loss due to infiltration from tobacco fields with different forms of nitrogen fertilizer are shown in

Figure 2. Nitrogen loss due to infiltration in the T2 and T3 treatments was significantly lower than that in the T1, T4, and T5 treatments in terms of the total nitrogen, nitrate-nitrogen, and ammonium-nitrogen contents in the two field experiments.

At the Chengjiang experimental site, the total nitrogen loss due to infiltration was characterized by the order T5 > T1 > T2 > T4 > T3 during the tobacco growth periods. Total nitrogen loss due to infiltration in the T1 and T5 treatments was significantly higher than that of the T2, T3, and T4 treatments (P < 0.05), but there were no significant differences among the T4, T3, and T2 treatments (P > 0.05). Nitrate-nitrogen loss due to infiltration was characterized by the order T1 > T2 > T4 > T3 > T5. Nitrate-nitrogen loss due to infiltration in the T1 and T2 treatments was significantly lower than that in the T3, T4, and T5 treatments (P < 0.05), but there were no significant differences among the T3, T4, and T5 treatments (P > 0.05). Ammonium-nitrogen loss due to infiltration was ranked in the order T5 > T4 > T3 > T2 > T1. Ammonium-nitrogen loss in runoff in the T5 and T4 treatments was significantly higher than that in the T3, T2, and T1 treatments (P < 0.05), but there were no significant differences among the T3, T2, and T1 treatments (P > 0.05).

At the Mile experimental site, the total nitrogen loss due to infiltration was characterized by the order T5 > T4 > T1 > T2 > T3 during the experimental periods. Total nitrogen loss due to infiltration in the T1, T2, and T3 treatments was significantly lower than that of the T4 and T5 treatments (P < 0.05), but there were no significant differences among the T1, T2, and T3 treatments (P > 0.05). Nitrate-nitrogen loss due to infiltration was ranked in the order T1 > T2 > T4 > T5 > T3. Nitrate-nitrogen loss due to infiltration in the T3 and T5 treatments was significantly lower than that in the T1, T2, and T4 treatments (P < 0.05), but there were no significant differences among the T1, T2, and T4 treatments (P > 0.05). Ammonium-nitrogen loss due to infiltration was ranked in the order T5 > T4 > T3 > T2 > T1. Ammonium-nitrogen loss in runoff in the T4 and T5 treatments was significantly higher than that in the T3, T2, and T1 treatments (P < 0.05), but there were no significant differences among the T3, T2, and T1 treatments (P > 0.05). The results from the two experimental sites result suggested that 50–50% nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer resulted in less total nitrogen loss, which may contribute to promoting the root growth of tobacco plants and the absorption of soil nutrients.

3.2. Root Spatial Distribution of Tobacco with Different Forms of Nitrogen Fertilizer

3.2.1. Root Biomass of Tobacco with Different forms Of Nitrogen Fertilizer

The characteristics of the root biomass of tobacco with different forms of nitrogen fertilizer are shown in

Table 3. At the Chengjiang experimental site, the root biomass of tobacco was characterized by the order T3 > T1 > T2 > T4 > T5 during the tobacco growth periods. The root biomass of tobacco in the T1, T2, and T3 treatments was significantly higher than that of the T4 and T5 treatments (P < 0.05), but there were no significant differences among the T1, T2, and T3 treatments (P > 0.05). At the Mile experimental site, the root biomass of tobacco was characterized by the order T3 > T4 > T1 > T2 > T5. The root biomass of tobacco in the T1, T2, and T3 treatments was significantly higher than that of the T4 and T5 treatments (P < 0.05), but there were no significant differences among the T1, T2, and T3 treatments (P > 0.05). Compared to the T5 treatment, the root biomass of tobacco in the T1, T2, T3, and T4 treatments increased by 15.49–18.32%, 11.74–14.87%, 18.99–22.36%, and 0.02–4.02%, respectively. The root biomass of tobacco in the T3 treatment was significantly higher than that of the T1, T2, T4, and T5 treatments in the two field experiments, indicating that 50–50% nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer could promote the root growth of tobacco after transplanting.

3.2.2. Characteristics of the Root Surface Area of Tobacco under Different Forms of Nitrogen Fertilizer

The characteristics of the root surface area of tobacco under different forms of nitrogen fertilizer are shown in

Table 3. At the Mile experimental site, the root surface area of the T3 and T2 treatments was significantly higher than that of the T1, T4, and T5 treatments in the 0–20 cm soil layer (vertical direction), and the same result was observed in the 20–40 cm soil layer. The root surface area was characterized by the order T1 > T2 > T3 > T4 > T5 in the 40–60 cm soil layer. At the Chengjiang experimental site, the root surface area of the T3 and T2 treatments was significantly higher than that of the T1, T4, and T5 treatments in the 0–20 cm soil layer (vertical distance), and the same result was observed in the 20–40 cm soil layer. The root surface area was characterized by the order T4 > T2 > T3 > T1 > T5 in the 40–60 cm soil layer, indicating that 50–50% nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer could promote the root growth of tobacco after transplanting.

At the Mile experimental site, the root surface area was characterized by the order T2 > T1 > T3 > T5> T4 in the 0–10 cm soil layer (horizontal directions), T3 > T2 > T1 > T4> T5 in the 10–20 cm soil layer, and T4 > T3 > T1 > T5> T2 in the 20–30 cm soil layer. At the Chengjiang experimental site, the root surface area was characterized by the order T3 > T2 > T4 > T1> T5 in the 0–10 cm, 10–20 cm, and 20–30 cm soil layers. The root surface area in the T3 and T2 treatments was higher than that in the T1, T4, and T5 treatments during the experimental periods. The results suggested that a high nitrate-nitrogen content of fertilizer was beneficial to root elongation both longitudinally and laterally, and 50–50% nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer and 75–25% nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer facilitated root growth and promoted nutrient uptake in both different directions in the soil layers.

3.2.3. Characteristics of the Root Distribution of the Root System under Different Forms of Nitrogen Fertilizer

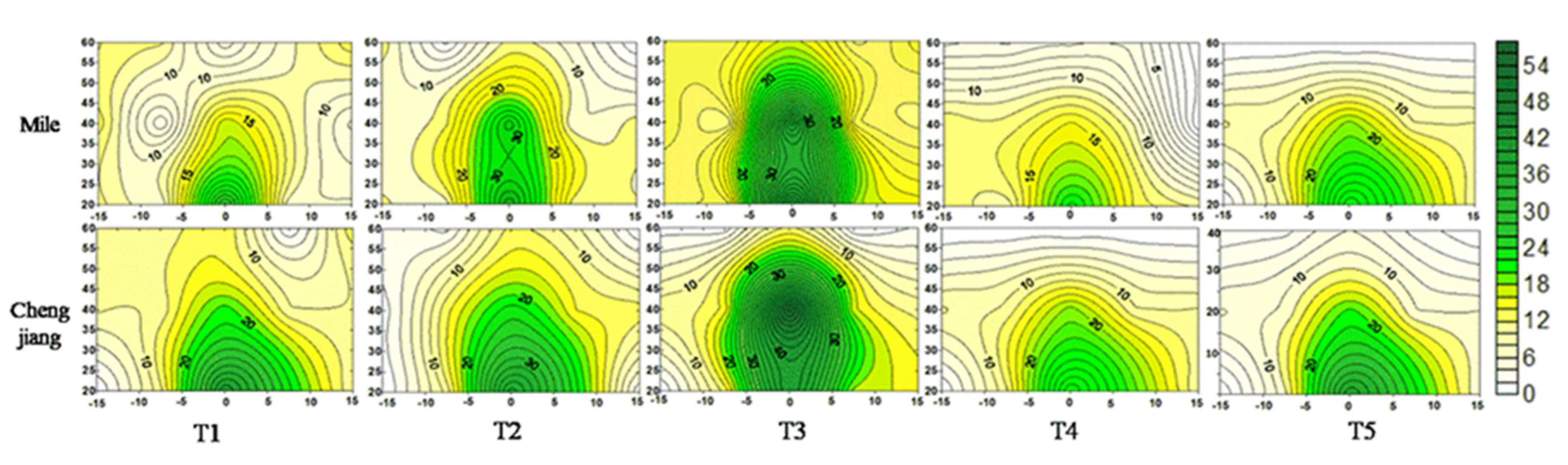

The root distribution in the 0–60 cm soil layer is shown in

Figure 3. The roots were mainly distributed in the 0–40 cm soil layer at the two experimental sites. The root distribution of the T2 and T3 treatments was greater than that of the T1, T4, and T5 treatments. The root distribution of the T1, T2, and T3 treatments was both wider and deeper compared with that of the T4 and T5 treatments. The results suggested that root distribution in the 50–50% nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer treatment was better than that in the T1, T2, T4, and T5 treatments, which may contribute to a reduction in nutrient loss.

3.3. Relationship of the Root System of Tobacco and Nitrogen Loss under Different Forms of Nitrogen Fertilizer

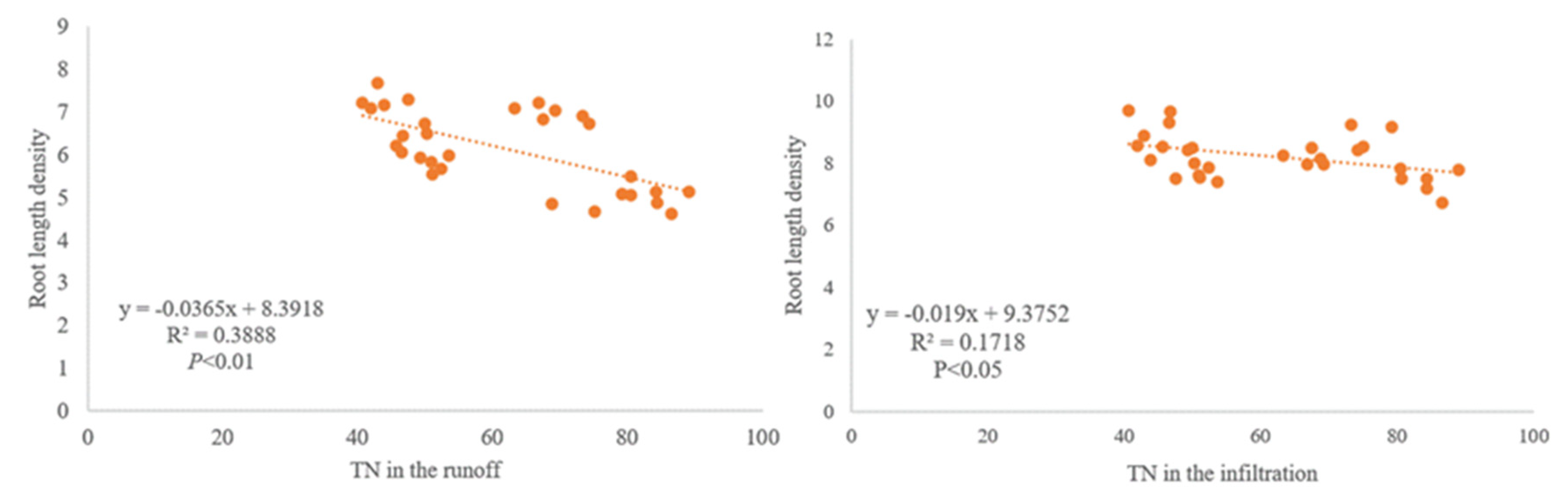

The relationship between the root system of tobacco and nitrogen loss under different forms of nitrogen fertilizer is shown in

Figure 4. The two experimental sites showed that the nitrogen loss was closely related to the root system under different forms of nitrogen fertilizer. The nitrogen loss decreased and the root length density (root biomass) increased when the proportion of nitrate nitrogen fertilizer increased. By contrast, the nitrogen loss increased and the root length density (root biomass) decreased when the proportion of ammonium nitrogen fertilizer increased. The results suggested that root morphology plays an important role in reducing nitrogen loss under different forms of nitrogen fertilizer.

3.4. Characteristics of Biomass under Different Forms of Nitrogen Fertilizer

The biomass of tobacco plants under different forms of nitrogen fertilizer is shown in

Table 4. The two experimental site results suggested that the biomass of tobacco plants in the T3 treatment was higher than that in the T2, T1, T4, and T5 treatments during the experimental periods. The biomass of tobacco plants was characterized in order T3 > T4 > T2 > T1> T5 at the Mile experimental site and T3 > T2 > T4 > T1> T5 at the Chengjiang experimental site. The biomass of tobacco plants in the T3 treatment was higher than that of the T1, T2, T4, and T5 treatments. In addition, the biomass of tobacco plants in the T1, T2, T4, and T5 treatments was 48.00%, 25.57%, 37.48%, and 70.66%, respectively, at the Mile experimental site and 39.63%, 29.33%, 26.84%, and 57.53%, respectively, at the Chengjiang experimental site. This indicates that 50–50% nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer can increase root absorption.

4. Discussion

The form of nitrogen loss in water is one of the key factors causing the eutrophication of lake water (Ann-Kristin et al. 2006). The results from the two experimental sites suggested that the loss of total nitrogen, nitrate nitrogen, and ammonium nitrogen in runoff and infiltration was significant when different forms of nitrogen fertilizer were added to the soil layer. The nitrogen loss in water in the 50–50% nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer treatment was lower, which may contribute to reducing agricultural non-point source pollution and providing a basis for fertilizer management in the watershed. This result is urgent and of great significance to effectively prevent and reduce agricultural non-point source pollution from farmland and protect water resources and ecological security.

The root system is the main organ that absorbs nitrogen, and its growth was affected, with significant effects on the root length, total surface area, root tip number, and root activity under different forms of nitrogen fertilizer (Ranjan et al. 2021). In this study, correlation analysis suggested that roots played an important role in nitrogen loss, that is, the loss of nitrogen was closely related to the root system under different forms of nitrogen fertilizer. The root length density, root surface area, and root weight of the 50–50% nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer treatment was higher than those of other treatments. The root spatial distribution results showed that the 50–50% nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer treatment changed the deep root system distribution, with more access to more of the soil volume, thus improving the roots under deep soil nitrogen and other nutrient absorption use, improving the use efficiency of nitrogen in the soil.

One reason is that nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer in the soil can decrease the pH, and increase the nitrogen supply in the soil under nitrification in agricultural soils. The absorption of nitrogen by the root system improves, and nitrogen use efficiency increases in tobacco farmland (Beeckman et al. 2018; Marcus et al. 1993). Wang showed that allowing roots to "extend vertically" reduces root crowding in the upper soil, making tobacco plants more efficient at absorbing nutrients from fertilizers (Wang et al. 2021). Furthermore, studies reported that nitrate does not adhere well to negatively charged soil particles and easily leaches into the soil. That, nitrate nitrogen in the soil is the most active in the process of soil nitrogen migration and transformation of nitrogen forms, which is difficult to be adsorbed by soil.

On the contrary, ammonium nitrogen adsorbs easily and is more efficient because ammonium is directly used to synthesize glutamine and subsequently other amino acids as well. The study suggested that ammonium nitrogen application resulted in higher chlorophyll, starch, monosaccharide, and amino acid levels, all important crop parameters when compared with nitrate nitrogen fertilizer (Beeckman et al. 2018). Thus, when 100% ammonium nitrogen is used as a nitrogen fertilizer, leading to short roots due to preventing plants from absorbing cations (Wang et al. 2021). The root activity decreased when a small number of lateral roots developed, there were more negatively charged suspended soil particles, and decreased with the generated rainfall runoff (Wang et al. 2018). Thus, in this study, 50–50% nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer not only guaranteed the nitrate-nitrogen active degree but also guaranteed fertilizer adsorption, promoted root growth and development, and improved fertilizer utilization efficiency (Caires et al. 2016). The improvement of fertilizer use efficiency further reduced the nitrogen transfer into river and lake basins and thus reduced the risk of eutrophication in lake basins (Husain et al. 2019).

5. Conclusions

This study suggested that the 50–50% nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer treatment had a smaller nitrogen loss than the 100% nitrate nitrogen fertilizer treatment and the 100% ammonium nitrogen fertilizer treatment, which contributed significantly to reducing agricultural non-point source pollution. An important reason is that flue-cured tobacco roots (root length density, root surface area, and spatial distribution) play an important role in the regulation of nitrogen loss with the roots in the 50–50% nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer treatment being the most developed. The root systems in the 50–50% nitrate-ammonium nitrogen fertilizer treatment was widely distributed in the different soil layers, maximizing the use of soil nutrients and reducing the entry of soil nitrogen nutrients into lake basins. The findings demonstrated that nitrogen form affected nitrogen loss by regulating growth of root morphology in the tobacco fields, which provides a theoretical basis for the prevention and control of agricultural non-point source pollution. Future studies can further improve this study by enhancing the agricultural non-point source pollution into similar fertilizer application management practices.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Chengren Ouyang and Zhengxiong Zhao conceived and designed the experiments. Kang Yang performed the experiments and analyzed the data and performed the analysis. Kang Yang and Chengren Ouyang wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final draft of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Program for the Key Research and Development Program of Yunnan, China (No. 202202AE090034), National Key R&D Program Projects (No. 2022YFD1901504), Basic Application Research Project of Yunnan Province, China (No. 2019YD096).

Acknowledgments

We thank LetPub (

www.letpub.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barcellos D, Queiroz HM, Nóbrega GN, de Oliveira Filho LR, Santaella ST, Otero XL, Ferreira TO. Phosphorus enriched effluents increase eutrophication risks for mangrove systems in northeastern Brazil. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2019,142: 58–63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beeckman F, Motte H, Beeckman T. Nitrification in agricultural soils: impact, actors and mitigation. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2018, 50: 166–173. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergstrom AK, Jansson M. Atmospheric nitrogen deposition has caused nitrogen enrichment and eutrophication of lakes in the northern hemisphere. Global Change Biology, 2006,12(4): 635–643. [CrossRef]

- Bhambri A, Karn SK. Biotechnique for nitrogen and phosphorus removal: a possible insight. Chemistry and Ecology,2020,36(8): 785-809. [CrossRef]

- Cai A, Xu M, Wang B, Zhang W, Liang G, Hou E, Luo Y. Manure acts as a better fertilizer for increasing crop yields than synthetic fertilizer does by improving soil fertility. Soil and Tillage Research,2019,189: 168–175. [CrossRef]

- Chen WB, Chen BM. Considering the preferences for nitrogen forms by invasive plants: a case study from a hydroponic culture experiment. Weed Research, 2019,59(1): 49–57. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Mao A, Alice Z, Zhang Y, Chang L, Gao J, Thompson HJ, Michael L. Carbon and nitrogen forms in soil organic matter influenced by incorporated wheat and corn residues. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition ,2017,63(4): 377–387. [CrossRef]

- Diao Y, Li H, Jiang H, Li H. Effects of changing fertilization since the 1980s on nitrogen runoff and leaching in rice–wheat rotation systems, Taihu Lake Basin. Water ,2020,12(3): 886. [CrossRef]

- Elsalam HEA, Sharnouby MEE, Mohamed AE, Raafat BM, El-Gamal EH. 2021. Effect of sewage sludge compost usage on corn and faba bean growth, carbon and nitrogen forms in plants and soil. Agronomy ,2021,11(4): 628.

- Hou P, Jiang Y, Yan L, Petropoulos E, Chen DL.. Effect of fertilization on nitrogen losses through surface runoffs in Chinese farmlands: A meta-analysis. Science of the Total Environment,2021,793: 148554.

- Kamel H, Khawla I, Selma F, Tarek S, Chedly A, Kadambot S, Cristina C. Interactive effects of salinity and nitrogen forms on plant growth, photosynthesis and osmotic adjustment in maize. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry,2019,139:171–178.

- Husain A, Muneer MA, Fan W, Yin GF, Shen SZh, Wang F, LI Y, Zhang KQ. Application of optimum n through different fertilizers alleviate NH+ 4–N, NO- 3–N and total nitrogen losses in the surface runoff and leached water and improve nitrogen use efficiency of rice crop in Erhai Lake Basin, China. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis ,2019,50(6): 716–738.

- Kakar K U, Nawaz Z, Cui ZhQ, Ahemd N, Ren XL. Molecular breeding approaches for production of disease-resilient commercially important tobacco. Briefings in Functional Genomics ,2020,19(1): 10–25. [CrossRef]

- Kurt D, Kinay A. Effects of irrigation, nitrogen forms and topping on sun cured tobacco. Industrial Crops and Products,2021,162(4):113276. [CrossRef]

- Li WH, Cheng XJ, Yu Z, Cheng GL, Zhao LW. Response of non-point source pollution to landscape pattern: A case study in mountain-rural region, China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research ,2021,28(13): 16602–16615. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu X, Zhang G, Sun G, Wu Y, Chen Y. Assessment of lake water quality and eutrophication risk in an agricultural irrigation area: A case study of the Chagan Lake in northeast China. Water ,2019,11(11): 2380. [CrossRef]

- Lu YX, Li CJ, Zhang FS. Transpiration, potassium uptake and flow in tobacco as affected by nitrogen forms and nutrient levels. Annals of Botany,2005,95(6): 991–998. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Dalmau J, Berbel J, Ordóñez-Fernández R. Nitrogen fertilization. A review of the risks associated with the inefficiency of its use and policy responses. Sustainability,2021,13(10): 5625. [CrossRef]

- Monchamp ME, Pick FR, Beisner BE, Maranger R. Nitrogen forms influence microcystin concentration and composition via changes in cyanobacterial community structure. PloSone,2014,9(1): e85573. [CrossRef]

- Pan SG, Liu HD, Mo ZW, Bob P, Duan MY, Tian H, Hu SJ, Tang XR. Corrigendum: Effects of nitrogen and shading on root morphologies, nutrient accumulation, and photosynthetic parameters in different rice genotypes. Scientific Reports ,2017,7: 45611. [CrossRef]

- Ranjan R, Yadav R. Genetics of root traits influencing nitrogen use efficiency under varied nitrogen level in spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Cereal Research Communications ,2022,50, 755–765.

- Schortemeyer M, Feil B, Stamp P. Root morphology and nitrogen uptake of maize simultaneously supplied with ammonium and nitrate in a split-root system. Annals of botany ,1993,72(2): 107–115. [CrossRef]

- Suyala Q, Liguo J, Qin YL, Chen Y, Fan MS. Effects of different nitrogen forms on potato growth and development. Journal of Plant Nutrition ,2017,40(11): 1651–1659. [CrossRef]

- Tan C, Ma M, Kuang H. Spatial-temporal characteristics and climatic responses of water level fluctuations of global major lakes from 2002 to 2010. Remote Sensing ,2017,9(2): 150. [CrossRef]

- Tang X, Li R, Han D, Scholz M. Response of eutrophication development to variations in nutrients and hydrological regime: a case study in the Changjiang River (Yangtze) Basin. Water ,2020,12(6): 1634. [CrossRef]

- Thorup-Kristensen K, Dresbøll DB, Kristensen HL. Crop yield, root growth, and nutrient dynamics in a conventional and three organic cropping systems with different levels of external inputs and N re-cycling through fertility building crops. European Journal of Agronomy,2012,37(1): 66–82. [CrossRef]

- Wang JF, Zhu CY, Weng BS, Mo PW, Xu ZJ, Ping T, Cui BS, Bai JH. Regulation of heavy metals accumulated by Acorus calamus L. in constructed wetland through different nitrogen forms. Chemosphere,2021,281: 130773. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang JL, Fu ZS, Chen GF, Zou GY, Song XF, Liu FX. Runoff nitrogen (N) losses and related metabolism enzyme activities in paddy field under different nitrogen fertilizer levels. Environmental Science and Pollution Research ,2018,25(27): 27583-27593. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia YF, Zhang M, C.W. Tsang D, Geng N, Lu DB, Zhu LF, Avanthi DI, Pavani DD, Jörg R, Xiao Y, Yong SO. Recent advances in control technologies for non-point source pollution with nitrogen and phosphorous from agricultural runoff: current practices and future prospects. Applied Biological Chemistry ,2020,63(1): 1–13.

- Xu G, Jiang M, Lu D, Wang H, Chen M. Nitrogen forms affect the root characteristic, photosynthesis, grain yield, and nitrogen use efficiency of rice under different irrigation regimes. Crop Science,2020,60(5): 2594–2610. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Huang G. A Risk-Based interval two-stage programming model for agricultural system management under uncertainty. Mathematical Problems in Engineering ,2016,7438913.1-7438913.13.

- Xue L, Hou P, Zhang Z, Shen M, Yang L. Application of systematic strategy for agricultural non-point source pollution control in Yangtze River basin, China. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment ,2020,304: 107148.

- Yang CH, Yang P, Geng J, Yin HB, Chen K. Sediment internal nutrient loading in the most polluted area of a shallow eutrophic lake (Lake Chaohu, China) and its contribution to lake eutrophication. Environmental Pollution ,2020, 262: 114292.

- Ying J, Li X, Wang N, Lan Z, He J, Bai Y. Contrasting effects of nitrogen forms and soil pH on ammonia oxidizing microorganisms and their responses to long-term nitrogen fertilization in a typical steppe ecosystem. Soil Biology and Biochemistry ,2017,107: 10–18. [CrossRef]

- Zhao ZX, Yuan Z, Yu LJ. A collection device for collecting water in runoff and infiltration from tobacco field. Innovation China, 2017,CN206515100U.

- Zhang XC, Razavi B, Liu JX, Wang G, Zhang XC, Li ZY, Zhai BN, Wang ZH, Zamanian K. Croplands conversion to cash crops in dry regions: Consequences of nitrogen losses and decreasing nitrogen use efficiency for the food chain system. Land Degradation & Development , 2021,32(3): 1103–1113.

- Zhang Y, Li H, Reggiani P. Climate variability and climate change impacts on land surface, hydrological processes and water management. Water, 2019,11(7): 1492. [CrossRef]

- Zhao LS, Hou R, Wu FQ, Keesstra S. Effect of soil surface roughness on infiltration water, ponding and runoff on tilled soils under rainfall simulation experiments. Soil and Tillage Research , 2018,179: 47–53. [CrossRef]

- Zia A, Berg LVD, Riaz M, Arif M, Ahsmore M. Nitrogen induced DOC and heavy metals leaching: Effects of nitrogen forms, deposition loads and liming. Environmental Pollution ,2020, 265(Pt B):114981.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).