Submitted:

10 September 2024

Posted:

11 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

1.1. Sarcopenia and Frailty Assessment amongst Cancer Patients

1.2. Alanine Aminotransferase as a Biomarker for Sarcopenia and Frailty

1.3. Renal Cell Carcinoma Patients and Survivors

1.4. Aim of the Current Study

2. Methods

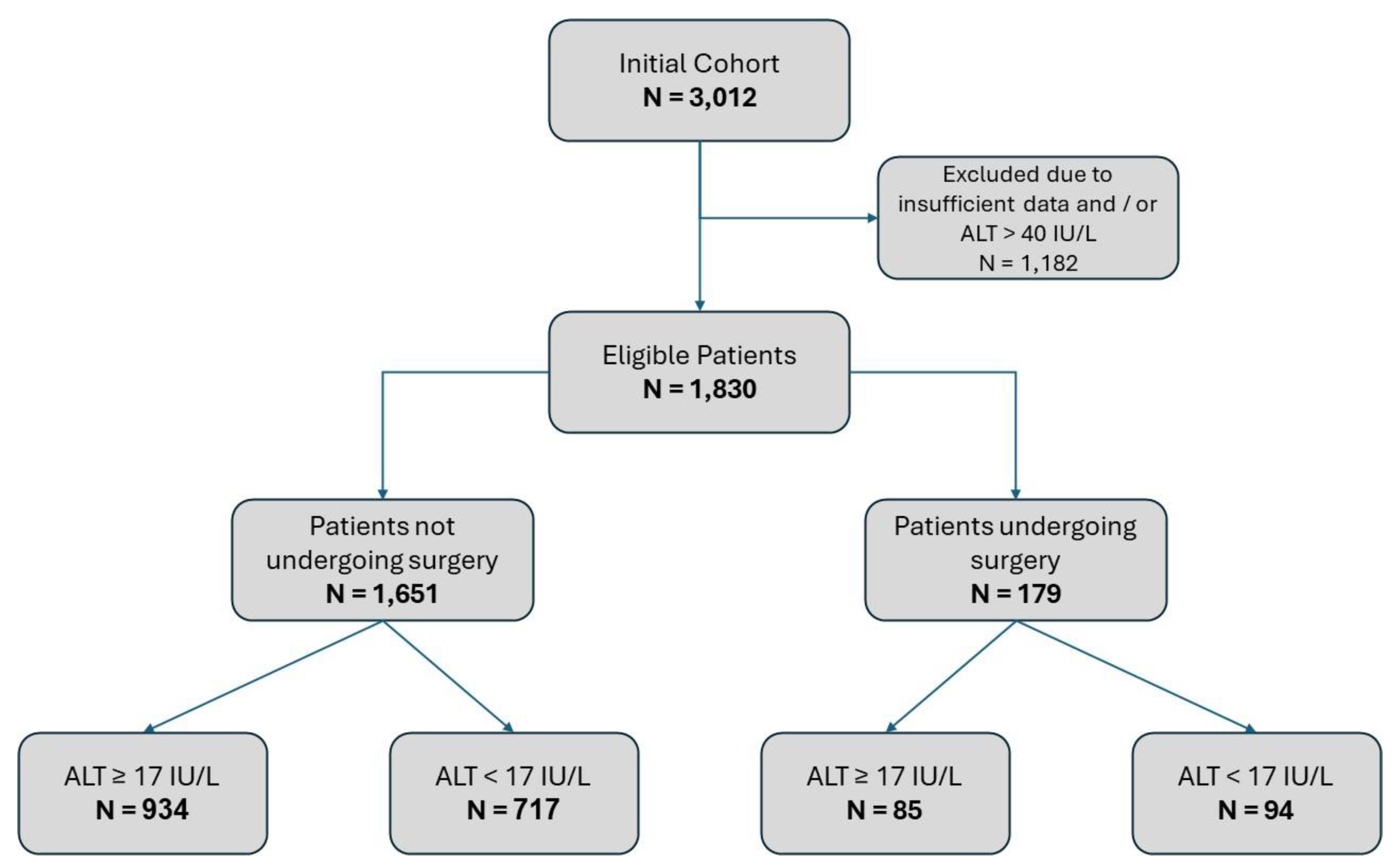

2.1. Study Cohort

2.2. Statistical Analysis of Data

3. Results

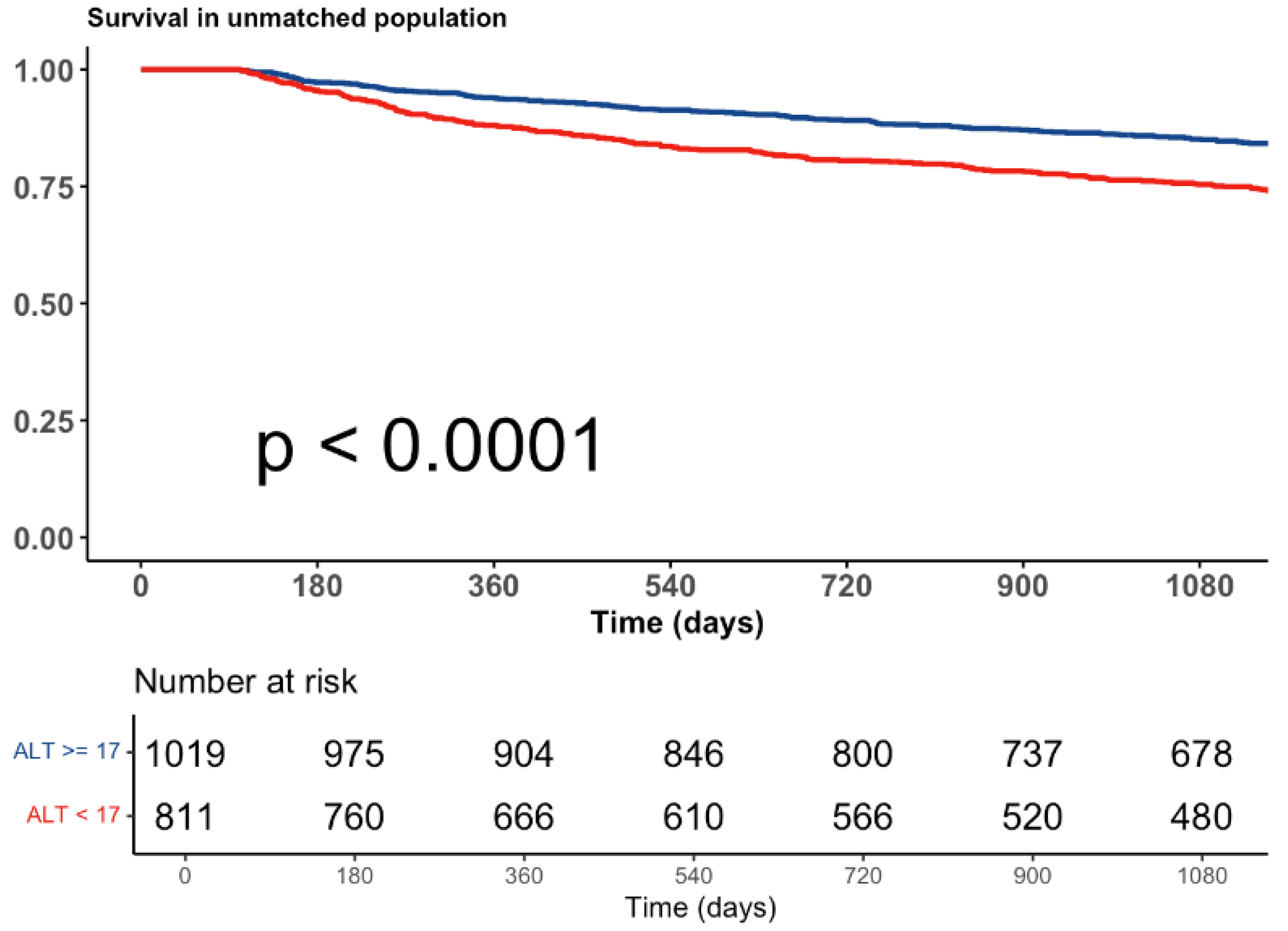

3.1. Univariate Analysis

3.2. Multivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Personalized vs. Precision Medicine for Cancer Patients

4.2. Sarcopenia and Frailty of RCC Patients

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

References

- Sinha P, Kallogjeri D, Piccirillo JF. Assessment of comorbidities in surgical oncology outcomes. J Surg Oncol [Internet]. 2014 Oct 1 [cited 2023 Aug 23];110(5):629–35. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25100618/.

- Simcock R, Wright J. Beyond Performance Status. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) [Internet]. 2020 Sep 1 [cited 2024 Apr 30];32(9):553–61. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32684503/.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Sayer AA. Sarcopenia. Lancet [Internet]. 2019 Jun 29 [cited 2023 Aug 23];393(10191):2636–46. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31171417/.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, Cederholm T, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing [Internet]. 2019 Jan 1 [cited 2023 Aug 23];48(1):16–31. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30312372/.

- Picca A, Coelho-Junior HJ, Calvani R, Marzetti E, Vetrano DL. Biomarkers shared by frailty and sarcopenia in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev [Internet]. 2022 Jan 1 [cited 2023 Aug 23];73. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34839041/.

- Korc-Grodzicki B, Downey RJ, Shahrokni A, Kingham TP, Patel SG, Audisio RA. Surgical considerations in older adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2014 Aug 20 [cited 2023 Feb 6];32(24):2647–53. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25071124/.

- Ryan AM, Prado CM, Sullivan ES, Power DG, Daly LE. Effects of weight loss and sarcopenia on response to chemotherapy, quality of life, and survival. Nutrition [Internet]. 2019 Nov 1 [cited 2023 Aug 26];67–68. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31522087/.

- Au PCM, Li HL, Lee GKY, Li GHY, Chan M, Cheung BMY, et al. Sarcopenia and mortality in cancer: A meta-analysis. Osteoporos Sarcopenia [Internet]. 2021 Mar [cited 2023 Feb 6];7(Suppl 1):S28–33. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33997306/.

- Liu Z, Que S, Xu J, Peng T. Alanine aminotransferase-old biomarker and new concept: a review. Int J Med Sci [Internet]. 2014 Jun 26 [cited 2023 Feb 7];11(9):925–35. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25013373/.

- Ramaty E, Maor E, Peltz-Sinvani N, Brom A, Grinfeld A, Kivity S, et al. Low ALT blood levels predict long-term all-cause mortality among adults. A historical prospective cohort study. Eur J Intern Med [Internet]. 2014 Dec 1 [cited 2023 Feb 7];25(10):919–21. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25468741/.

- Ruhl CE, Everhart JE. The association of low serum alanine aminotransferase activity with mortality in the US population. Am J Epidemiol [Internet]. 2013 Dec [cited 2023 Feb 7];178(12):1702–11. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24071009/.

- Segev A, Itelman E, Avaky C, Negru L, Shenhav-Saltzman G, Grupper A, et al. Low ALT Levels Associated with Poor Outcomes in 8700 Hospitalized Heart Failure Patients. J Clin Med [Internet]. 2020 Oct 1 [cited 2023 Aug 29];9(10):1–10. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33008125/.

- Uliel N, Segal G, Perri A, Turpashvili N, Kassif Lerner R, Itelman E. Low ALT, a marker of sarcopenia and frailty, is associated with shortened survival amongst myelodysplastic syndrome patients: A retrospective study. Medicine [Internet]. 2023 Apr 25 [cited 2023 May 10];102(17):e33659. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37115069.

- Laufer M, Perelman M, Sarfaty M, Itelman E, Segal G. Low Alanine Aminotransferase, as a Marker of Sarcopenia and Frailty, Is Associated with Shorter Survival Among Prostate Cancer Patients and Survivors. A Retrospective Cohort Analysis of 4064 Patients. Eur Urol Open Sci [Internet]. 2023 Sep 1 [cited 2023 Oct 28];55:38–44. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37693730/.

- Laufer M, Perelman M, Segal G, Sarfaty M, Itelman E. Low Alanine Aminotransferase as a Marker for Sarcopenia and Frailty, Is Associated with Decreased Survival of Bladder Cancer Patients and Survivors-A Retrospective Data Analysis of 3075 Patients. Cancers (Basel) [Internet]. 2023 Jan 1 [cited 2024 Apr 30];16(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38201601/.

- Hellou T, Dumanis G, Badarna A, Segal G. Low Alanine-Aminotransferase Blood Activity Is Associated with Increased Mortality in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Patients: A Retrospective Cohort Study of 716 Patients. Cancers (Basel) [Internet]. 2023 Sep 17 [cited 2023 Oct 28];15(18):4606. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37760575/.

- Capitanio U, Bensalah K, Bex A, Boorjian SA, Bray F, Coleman J, et al. Epidemiology of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur Urol [Internet]. 2019 Jan 1 [cited 2024 May 1];75(1):74–84. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30243799/.

- Bukavina L, Bensalah K, Bray F, Carlo M, Challacombe B, Karam JA, et al. Epidemiology of Renal Cell Carcinoma: 2022 Update. Eur Urol [Internet]. 2022 Nov 1 [cited 2024 May 1];82(5):529–42. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36100483/.

- Chen YW, Wang L, Panian J, Dhanji S, Derweesh I, Rose B, et al. Treatment Landscape of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol [Internet]. 2023 Dec 1 [cited 2024 May 1];24(12):1889–916. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38153686/.

- Klatte T, Rossi SH, Stewart GD. Prognostic factors and prognostic models for renal cell carcinoma: a literature review. World J Urol [Internet]. 2018 Dec 1 [cited 2024 May 1];36(12):1943–52. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29713755/.

- Maia MC, Adashek J, Bergerot P, Almeida L, dos Santos SF, Pal SK. Current systemic therapies for metastatic renal cell carcinoma in older adults: A comprehensive review. J Geriatr Oncol [Internet]. 2018 May 1 [cited 2024 May 2];9(3):265–74. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29249644/.

- Esther J, Hale P, Hahn AW, Agarwal N, Maughan BL. Treatment Decisions for Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma in Older Patients: The Role of TKIs and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Drugs Aging. 2019 May 1;36(5):395–401.

- Ueki H, Hara T, Okamura Y, Bando Y, Terakawa T, Furukawa J, et al. Association between sarcopenia based on psoas muscle index and the response to nivolumab in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A retrospective study. Investig Clin Urol. 2022;63(4):415–24.

- Noguchi G, Kawahara T, Kobayashi K, Tsutsumi S, Ohtake S, Osaka K, et al. A lower psoas muscle volume was associated with a higher rate of recurrence in male clear cell renal cell carcinoma. PLoS One [Internet]. 2020 Jan 1 [cited 2024 May 2];15(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31895931/.

- Ishihara H, Nishimura K, Ikeda T, Fukuda H, Yoshida K, Iizuka J, et al. Impact of body composition on outcomes of immune checkpoint inhibitor combination therapy in patients with previously untreated advanced renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 May 2]; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38653590/.

- Rosiello G, Larcher A, Fallara G, Cignoli D, Re C, Martini A, et al. A comprehensive assessment of frailty status on surgical, functional and oncologic outcomes in patients treated with partial nephrectomy—A large, retrospective, single-center study. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations. 2023 Mar 1;41(3):149.e17-149.e25.

- Courcier J, De La Taille A, Lassau N, Ingels A. Comorbidity and frailty assessment in renal cell carcinoma patients. World J Urol [Internet]. 2021 Aug 1 [cited 2024 May 1];39(8):2831–41. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33616708/.

- Campi R, Berni A, Amparore D, Bertolo R, Capitanio U, Carbonara U, et al. Impact of frailty on perioperative and oncologic outcomes in patients undergoing surgery or ablation for renal cancer: a systematic review. Minerva urology and nephrology [Internet]. 2022 Apr 1 [cited 2024 Mar 16];74(2):146–60. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34714036/.

- Walach MT, Wunderle MF, Haertel N, Mühlbauer JK, Kowalewski KF, Wagener N, et al. Frailty predicts outcome of partial nephrectomy and guides treatment decision towards active surveillance and tumor ablation. World J Urol. 2021 Aug 1;39(8):2843–51.

- Sharma R, Kannourakis G, Prithviraj P, Ahmed N. Precision Medicine: An Optimal Approach to Patient Care in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Front Med (Lausanne) [Internet]. 2022 Jun 14 [cited 2024 May 17];9:766869. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC9237320/.

- Massari F, Santoni M, Di Nunno V, Cimadamore A, Battelli N, Scarpelli M, et al. Quick steps toward precision medicine in renal cell carcinoma. Expert Rev Precis Med Drug Dev [Internet]. 2018 Sep 3 [cited 2024 May 17];3(5):283–5. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/23808993.2018.1510289.

- Gambardella V, Tarazona N, Cejalvo JM, Lombardi P, Huerta M, Roselló S, et al. Personalized Medicine: Recent Progress in Cancer Therapy. Cancers (Basel) [Internet]. 2020 Apr 1 [cited 2024 May 17];12(4). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7226371/.

- Krzyszczyk P, Acevedo A, Davidoff EJ, Timmins LM, Marrero-Berrios I, Patel M, et al. The growing role of precision and personalized medicine for cancer treatment. Technology (Singap World Sci) [Internet]. 2018 Sep [cited 2024 May 17];6(3–4):79. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6352312/.

- Massaad E, Saylor PJ, Hadzipasic M, Kiapour A, Oh K, Schwab JH, et al. The effectiveness of systemic therapies after surgery for metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the spine: a propensity analysis controlling for sarcopenia, frailty, and nutrition. J Neurosurg Spine [Internet]. 2021 Sep 1 [cited 2024 May 17];35(3):356–65. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34171829/.

| Whole study cohort N = 1,830 |

ALT ≥ 17 IU/L N = 1,019 |

ALT < 17 IU/L N = 811 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALT (Mean IU/L [SD]) | 18.83 (8.01) | 24.44 (6.07) | 11.79 (3.04) | < 0.001 |

| Patients’ demographics | ||||

| Age (years, Mean [SD]) | 65.6 (13.3) | 63.7 (12.9) | 67.9 (13.5) | < 0.001 |

| Male gender (N [%]) | 1,238 (68) | 704 (69) | 534 (66) | 0.155 |

| BMI (Mean [SD]) | 27.4 (5) | 28 (5.1) | 26.6 (4.9) | < 0.001 |

| Clinical background | ||||

| Diabetes Mellitus (N [%]) | 428 (23) | 219 (22) | 209 (26) | 0.036 |

| Dyslipidemia (N [%]) | 657 (36) | 379 (37) | 278 (34) | 0.214 |

| Arterial Hypertension (N [%]) | 980 (54) | 520 (51) | 460 (57) | 0.017 |

| COPD (N [%]) | 113 (6) | 53 (5.2) | 60 (7.4) | 0.065 |

| CHF (N [%]) | 67 (3.7) | 30 (2.9) | 37 (4.6) | 0.088 |

| Atrial Fib. (N [%]) | 139 (8) | 62 (6.1) | 77 (9.5) | 0.008 |

| S/P Stroke (N [%]) | 95 (5.2) | 47 (4.6) | 48 (5.9) | 0.252 |

| Laboratory parameters | ||||

| Albumin (gr/dL, Mean [SD]) | 3.9 (1.38) | 3.93 (0.58) | 3.86 (1.97) | 0.32 |

| Hemoglobin (gr/dL, Mean [SD]) | 12.57 (2.02) | 12.91 (1.9) | 12.14 (2.09) | < 0.001 |

| Platelets (K/mcl, Mean [SD]) | 236 (95) | 233 (91) | 239 (100) | 0.17 |

| Neut. / Lymph. (Mean [SD]) | 4.87 (5.85) | 4.67 (5.06) | 5.12 (6.71) | 0.106 |

| Plt. / Lymph. (Mean [SD]) | 166 (118) | 156 (115) | 178 (121) | < 0.001 |

| LDH (IU/L, Mean [SD]) | 243 (149) | 245 (159) | 240 (135) | 0.496 |

| Calcium (mg/dL, Mean [SD]) | 7.69 (3.43) | 7.56 (3.56) | 7.85 (3.26) | 0.069 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL, Mean [SD]) | 1.29 (1.08) | 1.14 (0.69) | 1.49 (1.4) | < 0.001 |

| Time to death / end of follow-up (days, Mean [SD]) | 1,946 (1,474) | 2,045 (1,457) | 1,822 (1,487) | 0.001 |

| Patient characteristics | HR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| ALT < 17 IU/L | 1.27 [1.08 – 1.51] | 0.005 |

| Age | 1.05 [1.05 – 1.06] | < 0.001 |

| Male gender | 1.6 [1.33 – 1.92] | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 0.84 [0.81 – 0.87] | < 0.001 |

| Platelets (K/mcl) | 1.00 [1.00 – 1.00] | 0.003 |

| LHD (IU/L) | 1.00 [1.00 – 1.00] | < 0.001 |

| Platelets / Lymphocytes | 1.00 [1.00 – 1.00] | 0.007 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).