Submitted:

09 September 2024

Posted:

10 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction:

Materials and Methods:

2.1. Variables of Interest

2.2. Data Analysis

Results:

Discussion:

Author Contributions

Funding Sources

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest Statement

References

- Steele, S.R.; Martin, M.J.; Mullenix, P.S.; Azarow, K.S.; Andersen, C.A. The significance of incidental thyroid abnormalities identified during carotid duplex ultrasonography. Arch Surg. 2005, 140, 981–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagag, P.; Strauss, S.; Weiss, M. Role of ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy in evaluation of nonpalpable thyroid nodules. Thyroid. 1998, 8, 989–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam-Goong, I.S.; Kim, H.Y.; Gong, G.; Lee, H.K.; Hong, S.J.; Kim, W.B.; et al. Ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration of thyroid incidentaloma: correlation with pathological findings. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2004, 60, 21–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leenhardt, L.; Hejblum, G.; Franc, B.; Fediaevsky, L.D.; Delbot, T.; Le Guillouzic, D.; et al. Indications and limits of ultrasound-guided cytology in the management of nonpalpable thyroid nodules. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999, 84, 24–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papini, E.; Guglielmi, R.; Bianchini, A.; Crescenzi, A.; Taccogna, S.; Nardi, F.; et al. Risk of malignancy in nonpalpable thyroid nodules: predictive value of ultrasound and color-Doppler features. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002, 87, 1941–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessler, F.N.; Middleton, W.D.; Grant, E.G.; Hoang, J.K.; Berland, L.L.; Teefey, S.A.; et al. ACR Thyroid Imaging, Reporting and Data System (TI-RADS): White Paper of the ACR TI-RADS Committee. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017, 14, 587–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukasa-Kakamba, J.; Bayauli, P.; Sabbah, N.; Bidingija, J.; Atoot, A.; Mbunga, B.; et al. Ultrasound performance using the EU-TIRADS score in the diagnosis of thyroid cancer in Congolese hospitals. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 18442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukasa, J.K.; Bayauli-Mwasa, P.; Mbunga, B.K.; Bangolo, A.; Kavula, W.; Mukaya, J.; et al. The Spectrum of Thyroid Nodules at Kinshasa University Hospital, Democratic Republic of Congo: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health [Internet]. 2022, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Zaichick, V.; Tsyb, A.F.; Vtyurin, B.M. Trace elements and thyroid cancer. Analyst. 1995, 120, 817–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Xue, S.; Zhang, L.; Chen, G. Trace elements and the thyroid. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 904889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.-l.; Wu, H.-b.; Hu, W.-l.; Liu, J.-j.; Zhang, Q.; Xiao, W.; et al. Exposure to multiple trace elements and thyroid cancer risk in Chinese adults: A case-control study. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 2022, 246, 114049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegedüs, L. Clinical practice. The thyroid nodule. N Engl J Med. 2004, 351, 1764–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobaly, K.; Kim, C.S.; Mandel, S.J. Contemporary Management of Thyroid Nodules. Annual Review of Medicine. 2022, 73, 517–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werk, E.E.; Jr Vernon, B.M.; Gonzalez, J.J.; Ungaro, P.C.; McCoy, R.C. Cancer in thyroid nodules. A community hospital survey. Arch Intern Med. 1984, 144, 474–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfiore, A.; Giuffrida, D.; La Rosa, G.L.; Ippolito, O.; Russo, G.; Fiumara, A.; et al. High frequency of cancer in cold thyroid nodules occurring at young age. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1989, 121, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, N.; Medici, M.; Angell, T.E.; Liu, X.; Marqusee, E.; Cibas, E.S.; et al. The Influence of Patient Age on Thyroid Nodule Formation, Multinodularity, and Thyroid Cancer Risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015, 100, 4434–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosino, V.; Motta, G.; Tenore, G.; Coletta, M.; Guariglia, A.; Testa, D. The role of heavy metals and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in the oncogenesis of head and neck tumors and thyroid diseases: a pilot study. BioMetals. 2018, 31, 285–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Xiwen, "Exposure To Heavy Metals In Relation To Thyroid Dysfunctions In U.s. Adults" (2019). Public Health Theses. 1833.

- Kim, S.; Song, S.-H.; Lee, C.-W.; Kwon, J.-T.; Park, E.Y.; Oh, J.-K.; et al. Low-Level Environmental Mercury Exposure and Thyroid Cancer Risk Among Residents Living Near National Industrial Complexes in South Korea: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Thyroid. 2022, 32, 1118–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- "New initiative to support artisanal cobalt mining in the DRC". Mining Review. 2021-04-01. Retrieved 2022-10-02.

- Banza, C.L.; Nawrot, T.S.; Haufroid, V.; Decrée, S.; De Putter, T.; Smolders, E.; et al. High human exposure to cobalt and other metals in Katanga, a mining area of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Environ Res. 2009, 109, 745–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squadrone, S.; Burioli, E.; Monaco, G.; Koya, M.K.; Prearo, M.; Gennero, S.; et al. Human exposure to metals due to consumption of fish from an artificial lake basin close to an active mining area in Katanga (D.R. Congo). Sci Total Environ. 2016, 568, 679–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angell, T.E.; Maurer, R.; Wang, Z.; Kim, M.I.; Alexander, C.A.; Barletta, J.A.; et al. A Cohort Analysis of Clinical and Ultrasound Variables Predicting Cancer Risk in 20,001 Consecutive Thyroid Nodules. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019, 104, 5665–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappelli, C.; Castellano, M.; Pirola, I.; Cumetti, D.; Agosti, B.; Gandossi, E.; et al. The predictive value of ultrasound findings in the management of thyroid nodules. Qjm. 2007, 100, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sipos, J.A. Advances in ultrasound for the diagnosis and management of thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009, 19, 1363–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solbiati, L.; Volterrani, L.; Rizzatto, G.; Bazzocchi, M.; Busilacci, P.; Candiani, F.; et al. The thyroid gland with low uptake lesions: evaluation by ultrasound. Radiology. 1985, 155, 187–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochand-Priollet, B.; Guillausseau, P.J.; Chagnon, S.; Hoang, C.; Guillausseau-Scholer, C.; Chanson, P.; et al. The diagnostic value of fine-needle aspiration biopsy under ultrasonography in nonfunctional thyroid nodules: a prospective study comparing cytologic and histologic findings. Am J Med. 1994, 97, 152–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakkos, S.K.; Scopa, C.D.; Chalmoukis, A.K.; Karachalios, D.A.; Spiliotis, J.D.; Harkoftakis, J.G.; et al. Relative risk of cancer in sonographically detected thyroid nodules with calcifications. J Clin Ultrasound. 2000, 28, 347–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonavita, J.A.; Mayo, J.; Babb, J.; Bennett, G.; Oweity, T.; Macari, M.; et al. Pattern recognition of benign nodules at ultrasound of the thyroid: which nodules can be left alone? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009, 193, 207–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiernan, C.M.; Solórzano, C.C. Bethesda Category III, IV, and V Thyroid Nodules: Can Nodule Size Help Predict Malignancy? J Am Coll Surg. 2017, 225, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, A.; Johnson, D.N.; White, M.G.; Siddiqui, S.; Antic, T.; Mathew, M.; et al. Thyroid Nodule Size at Ultrasound as a Predictor of Malignancy and Final Pathologic Size. Thyroid. 2017, 27, 641–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.T.; Jeon, Y.W.; Suh, Y.J. The Prognostic Values of Preoperative Tumor Volume and Tumor Diameter in T1N0 Papillary Thyroid Cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 2017, 49, 890–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, B.R.; Alexander, E.K.; Bible, K.C.; Doherty, G.M.; Mandel, S.J.; Nikiforov, Y.E.; et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016, 26, 1–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | All (n=529) |

Single (n=74) |

Multiple (n=455) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 44.2±14,6 | 45.0±14.9 | 44.0±14.2 | 0.206 |

| ≤20 years | 35(6.6) | 8(10.8) | 7(5.9) | |

| 21-30 years | 54(10.2) | 2(2.7) | 52(11.4) | |

| 31-40 years | 135(25.5) | 19(25.7) | 116(25.5) | |

| 41-50 years | 127(24.0) | 19(25.7) | 108(23.7) | |

| 51-60 years | 96(18.1) | 14(18.9) | 82(18.0) | |

| >60 years | 82(15.5) | 12(16.2) | 70(15.4) | |

| Sex | 0.360 | |||

| Male | 82(15.6) | 13(17.6) | 69(15.3) | |

| Female | 444(84.4) | 61(82.4) | 383(84.7) | |

| Marital Status | 0.636 | |||

| Married | 373(75.1) | 51(77.3) | 322(74.7) | |

| Single | 115(23.1) | 13(19.7) | 102(23.7) | |

| Divorced/Widowed | 9(1.8) | 2(3.0) | 7(1.6) | |

| Origin of the sample | 0.280 | |||

| Kinshasa | 468(88.5) | 64(86.5) | 404(88.8) | |

| Katanga | 18(3.4) | 1(1.4) | 17(3.7) | |

| Sud Kivu | 43(8.1) | 9(12.2) | 34(7.5) |

| Variables | All (n=529) |

Single (n=74) |

Multiple (n=455) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parity | 0.670 | |||

| Nulliparous | 65(14.6) | 10(16.4) | 55(14.3) | |

| Primiparous | 40(9.0) | 5(8.2) | 35(9.1) | |

| Pauciparous | 102(22.9) | 17(27.9) | 85(22.1) | |

| Multiparous | 239(53.6) | 29(47.5) | 210(54.5) | |

| Gravida | 0.514 | |||

| Nulligravid | 71(16.0) | 11(18.0) | 60(15.6) | |

| Primigravid | 40(9.0) | 3(4.9) | 37(9.6) | |

| Multigravid | 334(75.1) | 47(77.0) | 287(74.7) | |

| Abortion | 83(18.7) | 15(24.6) | 68(17.7) | 0,135 |

| Family history of thyroid pathology | 352(66.5) | 51(68.9) | 301(66.2)) | 0,373 |

| First degree | 205(58.2) | 30(60.0) | 175(57.9) | |

| Second degree | 147(41.8) | 20(40.0) | 127(42.1) | |

| Anterior-cervical mass | 503(95.1) | 71(95.9) | 391(95.8) | 0.099 |

| Overweight | 195(36.9) | 23(31.1) | 172(37.8) | 0.163 |

| Obesity | 187(35.3) | 28(37.8) | 159(34.9) | 0.360 |

| Clinical LAD | 46(8.7) | 10(13.5) | 36(7.9) | 0.091 |

| SBP | 135.6±58.6 | 131.4±13.8 | 135.8±65.5 | 0.786 |

| DBP | 72.6±8.9 | 73.9±8.5 | 72.3±9.2 | 0.485 |

| BMI | 29.8±12.1 | 29.5±3.1 | 29.9±13.6 | 0.959 |

| HR | 83.0±11.0 | 82.0±11.6 | 83.1±10.6 | 0.557 |

| Total volume | 70.9±31.5 | 68.5±30.8 | 70.8±32.2 | 0.596 |

| Thyroid Fonction | 0.631 | |||

| euthyroid | 464(87.7) | 63(85.1) | 401(88.1) | |

| Hyperthyroid | 50(9.5) | 9(12.2) | 41(9.0) | |

| Hypothyroid | 15(2.8) | 2(2.7) | 13(2.9) |

| Variables | All (n=529) |

Simple (n=74) |

Multiple (n=408) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echostructure | 0.837 | |||

| Solid | 382(72.2) | 53(71.6) | 329(72.3) | |

| Liquid | 12(2.3) | 1(1.4) | 11(2.4) | |

| Mixed | 135(25.5) | 20(27.0) | 115(25.3) | |

| Echogenicity | 0.332 | |||

| Hypoechoic | 447(84.5) | 59(79.7) | 388(85.3) | |

| Isoechoic | 81(15.3) | 15(20.3) | 66(14.5) | |

| Anechoic | 1(0.2) | 0(0.0) | 1(0.2) | |

| Size | 0.360 | |||

| Macronodule | 315(59.8) | 50(67.6) | 265(58.5) | |

| Micronodule | 82(15.6) | 9(12.2) | 73(16.1) | |

| Mixed | 130(24.7) | 15(20.3) | 115(25.4) | |

| Microcalcification | 0.494 | |||

| No | 453(85.6) | 64(86.5) | 389(85.5) | |

| Yes | 76(14.4) | 10(13.5) | 66(14.5) | |

| Adenopathy | 0.352 | |||

| No | 447(84.5) | 61(82.4) | 386(84.8) | |

| Yes | 82(15.5) | 13(17.6) | 69(15.2) |

| Variables | Number (n=529) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Anapathology | ||

| Benign nodules | 441 | 77.7 |

| Malignant nodules | 118 | 22.3 |

| Benign nodules | ||

| Colloid goiter | 302 | 73.5 |

| Adenomatoid goiter | 36 | 8.8 |

| Follicular adenoma | 20 | 4.9 |

| Macrofollicular adenoma | 18 | 4.4 |

| Follicular cyst | 8 | 1.9 |

| Adenomatoid nodule | 5 | 1.2 |

| Thyroid abscess | 3 | 0.7 |

| Follicular adenoma | 3 | 0.7 |

| Microfollicular adenoma | 3 | 0.7 |

| Reactive LAD | 3 | 0.7 |

| Chronic strumitis | 3 | 0.7 |

| Grave’s disease | 2 | 0.5 |

| Non toxic adenoma | 1 | 0.2 |

| Toxic adenoma | 1 | 0.2 |

| Granulomatous thyroid | 1 | 0.2 |

| Dequervain's subacute thyroiditis | 1 | 0.2 |

| Hashimoto’s thyroiditis | 1 | 0.2 |

| Malignant nodules | ||

| Papillary carcinoma | 79 | 66.9 |

| Follicular carcinoma | 26 | 22.0 |

| Anaplastic carcinoma | 9 | 7.6 |

| Lymphoma | 3 | 2.5 |

| Medullary carcinoma | 1 | 0.8 |

| Variables | N | Benign nodule n(%) |

Malignant nodule n(%) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.003 | |||

| ≤20 years | 35 | 31(87.1) | 4(12.9) | |

| 21-60 years | 412 | 333(80.8) | 79(19.2) | |

| >60 years | 82 | 47(57.3) | 35(42.7) | |

| Sex | 0.061 | |||

| Male | 82 | 58(70.7) | 24(29.3) | |

| Female | 444 | 352(79.3) | 92(20.7) | |

| Province of origin of the sample | 0.044 | |||

| Kinshasa | 468 | 364(77.8) | 104(22.2) | |

| Katanga | 18 | 10(55.6) | 8(44.4) | |

| South Kivu | 43 | 37(86.0) | 6(14.0) | |

| Marital status | 0.256 | |||

| Married | 373 | 293(78.6) | 80(21.4) | |

| Single | 115 | 85(73.9) | 30(26.1) | |

| Divorced/widow | 9 | 7(77.8) | 2(22.2) | |

| Parity | 0,160 | |||

| Nulliparous | 65 | 46(70.8) | 19(29.2) | |

| Primiparous | 40 | 32(80.0) | 8(20.0) | |

| Pauciparous | 102 | 87(85.3) | 15(14.7) | |

| Multiparous | 239 | 187(78.2) | 52(21.8) | |

| Gravida | 0.311 | |||

| Nulligravid | 71 | 51(71.8) | 20(28.2) | |

| Primigravid | 40 | 32(80.0) | 8(20.0) | |

| Multigravid | 334 | 268(80.2) | 66(19.8) | |

| FH of thyroid pathology | 0.022 | |||

| No | 177 | 147(83.1) | 30(16.9) | |

| Yes | 352 | 264(75.0) | 88(25.0) | |

| BMI | 0.505 | |||

| Normal | 25 | 22(88.0) | 3(12.0) | |

| Overweight | 195 | 150(76.9) | 45(23.1) | |

| Obesity | 187 | 146(78.1) | 41(21.9) | |

| Clinical LAD | <0.001 | |||

| No | 100.0 | 397(82.2) | 86(17.8) | |

| Yes | 100.0 | 14(30.4) | 32(69.6) |

| Variables | N | Benign nodule n(%) |

Malignant nodule n(%) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echostructure | <0.001 | |||

| Solid | 382 | 268(70.2) | 114(29.8) | |

| Liquid | 12 | 12(100.0) | 0(0.0) | |

| Mixed | 135 | 4(97.0) | 4(3.0) | |

| Echogenicity | <0.001 | |||

| Hypoechoic | 447 | 330(73.8) | 117(26.2) | |

| Isoechoic | 81 | 80(98.8) | 1(1.2) | |

| Anechoic | 1 | 1(100.0) | 0(0.0) | |

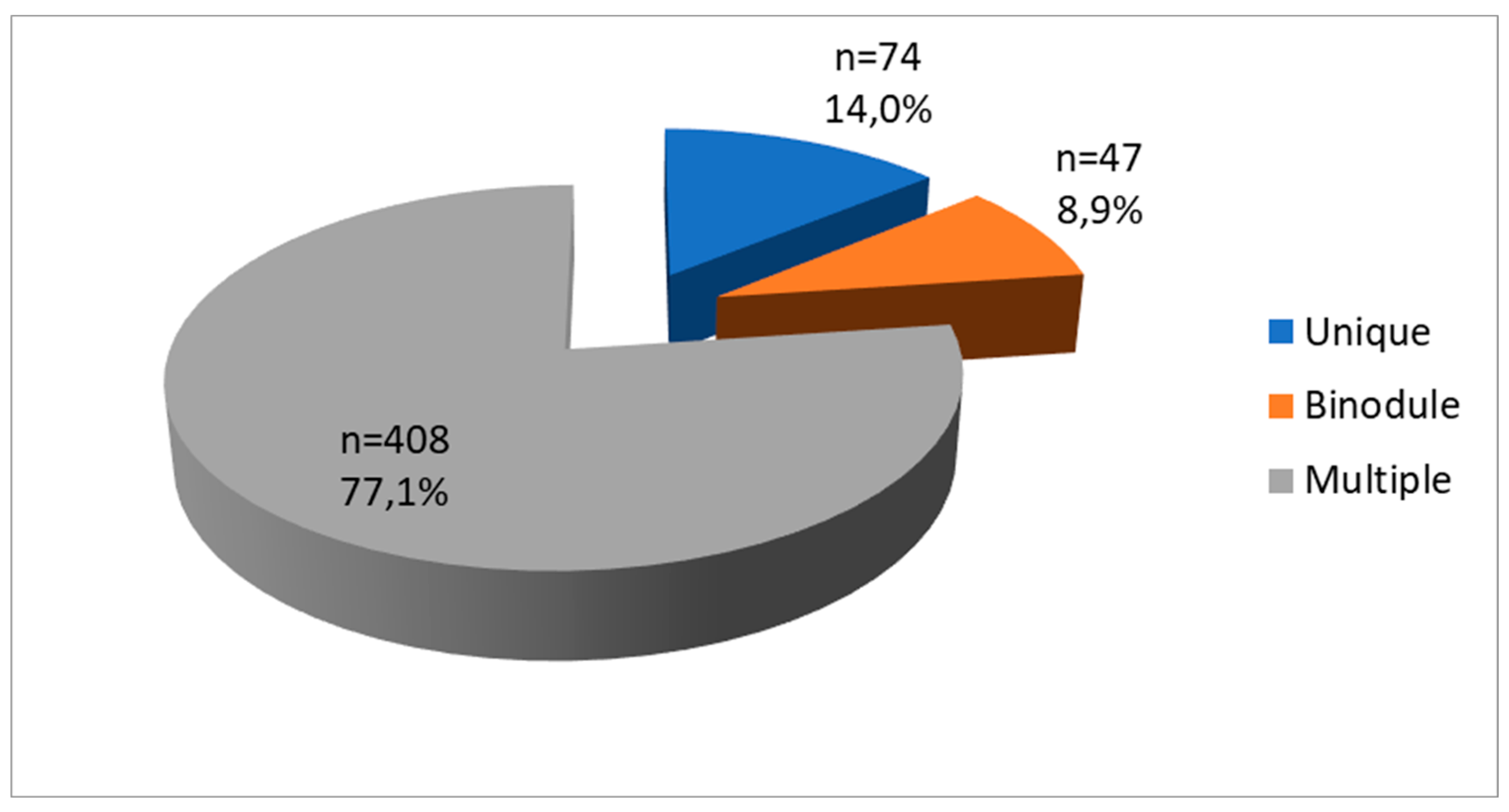

| Number | 0.284 | |||

| Unique | 74 | 55(74.3) | 19(25.7) | |

| Binodule | 47 | 33(70.2) | 14(29.8) | |

| Multiple | 408 | 323(79.2) | 85(20.8) | |

| Size | <0.001 | |||

| Macronodule | 315 | 211(67.0) | 104(33.0) | |

| Micronodule | 82 | 81(98.8) | 1(1.2) | |

| Mixed | 130 | 119(91.5) | 11(8.5) | |

| Calcification | <0.001 | |||

| No | 453 | 376(83.0) | 77(17.0) | |

| Yes | 76 | 35(46.1) | 41(53.9) | |

| Adenopathy | <0.001 | |||

| No | 447 | 382(85.5) | 65(14.5) | |

| Yes | 82 | 29(35.4) | 53(64.6) |

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | OR (CI 95%) | p | aOR (CI 95%) | ||

| Age | |||||

| ≤20 years | 1 | 1 | |||

| 21-60 years | 0,319 | 1.52(0,67-3.46) | 0.614 | 1,32(0.26-2.24) | |

| >60 years | 0.003 | 2.81(1.37-5.78) | 0.025 | 2.81(1.14-6.94) | |

| Province of origin of the sample | |||||

| South Kivu | 1 | 1 | |||

| Kinshasa | 0.212 | 1.76(0.72-4.29) | 0,116 | 2.47(0.80-7.62) | |

| Katanga | 0.014 | 4,93(1.39-17.54) | 0.036 | 8.19(1.14-12.45) | |

| FH of thyroid pathology | |||||

| No | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 0.022 | 1.63(1.03-2.59) | 0,105 | 1.65(0.90-3.34) | |

| Clinical LAD | |||||

| No | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | <0.001 | 10.55(5.40-20.62) | 0,760 | 1.20(0.38-3.82) | |

| Echostructure | |||||

| Liquid | 1 | 1 | |||

| Solid | <0.001 | 15,21(5.50-42.07) | 0.001 | 7.69(2.40-24.58) | |

| Echogenicity | |||||

| Isoechoic | 1 | 1 | |||

| Hypoechoic | <0.001 | 18.72(3.95-28.68) | 0.017 | 14.19(1.60-25.93) | |

| Size | |||||

| Micronodule | 1 | 1 | |||

| Macronodule | <0.001 | 5.33(2.75-10.33) | <0.001 | 9.13(4.19-19.89) | |

| Calcification | |||||

| No | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | <0.001 | 5.72(3.42-9.55) | 0.017 | 2.60(1.19-5.70) | |

| Ultrasound LAD | |||||

| No | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | <0.001 | 10.74(6.36-18.13) | <0.000 | 6.94(2.79-17.25) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).