1. Introduction

The global incidence of thyroid cancer has undergone a significant increase over recent decades, transforming it into a prominent public health concern worldwide [

1]. This rising trend is attributed to a complex interplay of factors, including enhanced detection through advanced imaging technologies, genuine increases in risk factor exposures, and a deeper understanding of the molecular underpinnings of the disease [

2]. Thyroid cancer is broadly classified into several distinct histological subtypes, primarily differentiated thyroid carcinomas (DTCs), encompassing papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) and follicular thyroid carcinoma (FTC), and less common, more aggressive forms, including medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) and anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC) [

3]. Each subtype exhibits unique biological behaviors, molecular profiles, and clinical outcomes [

4].

Genetic alterations represent critical drivers in the initiation and progression of thyroid malignancies. PTC, the most prevalent subtype, is frequently characterized by mutations in the

BRAF gene, particularly the

BRAF V600E variant, approximately 40-50% of PTCs, or by

RET/PTC chromosomal rearrangements [

5]. FTC is predominantly associated with mutations in the

RAS family genes (

HRAS,

KRAS,

NRAS) or

PAX8-PPARγ fusion gene, which are often linked to capsular or vascular invasion and metastatic potential [

6]. MTC, arising from parafollicular C cells, is strongly linked to germline or somatic mutations in the

RET proto-oncogene, forming the basis for genetic screening in affected families (Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type 2 syndromes) and targeted therapies [

7]. ATC, an extremely aggressive and typically fatal malignancy, harbors a high frequency of mutations in

TP53,

TERT promoter, and frequently co-occurs with

BRAF or

RAS mutations, contributing to its rapid progression and therapeutic resistance [

8].

Environmental exposures are well-established contributors to thyroid carcinogenesis. Ionizing radiation, particularly exposure during childhood or adolescence, remains the most prominent environmental risk factor [

9,

10]. Studies following atomic bomb survivors and populations exposed to fallout from nuclear accidents, notably Chernobyl, have demonstrated a significantly elevated risk of PTC, often characterized by specific

RET/PTC rearrangements, decades after exposure [

11]. Beyond ionizing radiation, exposure to certain environmental pollutants has been implicated in thyroid dysfunction and potentially thyroid cancer. These include heavy metals, pesticides, and various endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) found in industrial settings, contaminated water sources, and consumer products [

12,

13]. The precise mechanisms by which these pollutants impact thyroid follicular cells and contribute to malignant transformation require further investigation.

Lifestyle factors and common health conditions also play a role in modulating thyroid cancer risk. Obesity, defined by a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m ² or higher, has been consistently associated with an increased risk of developing thyroid cancer, particularly PTC [

14]. Addressing obesity through lifestyle modifications, including balanced diet and increased physical activity, is therefore a potential strategy for mitigating this risk [

15]. The association between smoking and thyroid cancer risk remains less clear and somewhat controversial in epidemiological studies, as meta analysis study by Lee et al, showed that some studies suggest a decreased risk, while others point to potential carcinogenic effects of tobacco components [

16].

Thyroid-specific conditions, such as thyroid dysfunction and the presence of thyroid nodules, are central to the clinical context of thyroid cancer. Thyroid nodules are exceedingly common, detected in a large proportion of the population by ultrasound, with the majority being benign [

17]. However, a significant minority (5-15%) are malignant, and accurate risk stratification of nodules is crucial to avoid unnecessary surgeries while detecting cancers early [

18]. Ultrasound features (e.g., hypoechogenicity, irregular margins, microcalcifications) and the size of the nodule are used for risk assessment, and fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) is the primary diagnostic tool [

19].

Thyroid dysfunction, including both hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, has been investigated for its association with thyroid cancer risk. While the relationship is complex and potentially influenced by the underlying cause of the dysfunction, some studies suggest that prolonged exposure to elevated TSH levels in hypothyroidism might be associated with an increased risk, particularly for follicular neoplasms, although this remains debated [

20]. Hyperthyroidism, particularly Graves' disease, may also be associated with an increased prevalence of thyroid cancer within surgical series, although this could be related to increased surveillance or specific disease mechanisms [

21]. Hashimoto thyroiditis (HT), an autoimmune thyroid disease leading to chronic inflammation and hypothyroidism, has a well-recognized association with PTC [

22]. The chronic inflammation and immune cell infiltration in HT may contribute to a pro-tumorigenic microenvironment, although conversely, the heightened immune surveillance in HT might also lead to earlier detection and potentially a more favorable prognosis for associated PTCs. Diabetes mellitus (DM), another prevalent chronic condition, has also been investigated for its link to thyroid cancer risk. Similar to obesity, DM is associated with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, which may promote thyroid cell proliferation via the IGF-1 pathway [

23].

Finally, hormonal factors, particularly exogenous hormones like oral contraceptives (OCPs), have been explored as potential modulators of thyroid cancer risk, given the strong female predominance of the disease [

24]. Pregnancy and hormone replacement therapy are other periods of significant hormonal fluctuation that have been investigated for their potential impact on thyroid cancer risk and progression, adding further complexity to understanding the role of endogenous and exogenous hormones [

25].

Considering the multifaceted nature of thyroid cancer etiology, understanding the interplay of genetic predispositions, environmental exposures, specific thyroid conditions, common health disorders like diabetes and obesity, and hormonal factors is essential for comprehensive risk assessment, targeted prevention strategies, and effective clinical management. Studying these factors within specific regional populations can provide valuable insights into localized risk profiles and disease patterns, informing public health initiatives and optimizing clinical approaches in diverse geographic settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This investigation employed a quantitative research design utilizing a cross-sectional approach to explore the associations between various demographic, clinical, and lifestyle factors and specific characteristics of thyroid cancer and thyroid nodules within a defined cohort. Data were collected retrospectively from existing medical records of patients who presented for examination at a major hospital in Ha'il, Saudi Arabia. This design facilitated the assessment of the prevalence of different thyroid conditions and the distribution of associated factors at a single point in time, allowing for the exploration of correlations between variables.

This investigation employed a quantitative research design utilizing a cross-sectional approach. Data were collected retrospectively from existing medical records of patients who presented for examination at a single, 500-bed tertiary care hospital in Ha'il, Saudi Arabia, between January 2022 and December 2025. This retrospective cross-sectional design facilitated the assessment of the prevalence of different thyroid conditions and the distribution of associated factors within this cohort at the time of their examination, allowing for the exploration of correlations between variables.

2.2. Population and Sampling

The study population comprised 208 individuals whose medical records were available and met the inclusion criteria during the specified study period. Participants were selected from patients examined at the participating tertiary hospital. Inclusion criteria included individuals aged 18 years or older with documented information pertaining to a thyroid diagnosis or examination (including histopathology for cancer cases) and relevant demographic and clinical data available in their medical files. Exclusion criteria involved individuals with substantially incomplete medical records regarding the variables of interest or those with significant, clearly documented comorbidities known to strongly confound the assessment of thyroid conditions independently (e.g., certain systemic autoimmune diseases impacting multiple organs beyond Hashimoto's, specific genetic syndromes with widespread effects). The final cohort size included in the analysis was 208 participants, based on the availability of suitable records meeting these criteria during the study timeframe.

The sampling method utilized accessible patient data from the participating institution, representing a convenience or consecutive sample of eligible patients presenting during the study period. We acknowledge that utilizing data from a single center (out of two major centers in the area) may introduce selection bias and limit the generalizability of findings to the broader regional or national population with thyroid conditions. Future multi-center studies could provide a more comprehensive view.

2.3. Data Collection Methods

Data for this study were systematically collected through a comprehensive retrospective review of existing electronic and paper medical records and corresponding histopathology reports maintained at the participating hospital.

Medical Record Review: Patient files served as the primary source for extracting demographic, clinical, and lifestyle information. Variables abstracted included: Age (categorized into 30-39, 40-49, and 50-60 years); Gender (recorded as Male or Female); Clinical History: Documented first-degree family history of thyroid disease (defined as a parent, sibling, or child with diagnosed thyroid cancer) was recorded as Negative or Positive; Smoking status (abstracted as Non-Smoker or Smoker based on recorded history); Obesity Status: Body Mass Index (BMI) was obtained directly from documented values in the patient records where available. If not directly recorded, BMI was calculated using documented height and weight measurements (kg/m ²). Obesity was categorized as Non-Obese (BMI < 30 kg/m ²) or Obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m ²); Oral Contraceptive Pill (OCP) Use: History of OCP use was recorded as Yes or No for female participants based on medication history or clinical notes; Comorbidities: Presence of diagnosed Hypertension (HT) and Diabetes Mellitus (DM) was abstracted as Yes or No based on documented diagnoses in the medical records; Thyroid Nodule Characteristics: Information on the presence and pattern of thyroid nodules was extracted from documented ultrasound reports. Nodules were classified as 'single' (one discrete nodule identified) or 'multiple' (two or more discrete nodules identified).

Histopathology Report Review: For all participants diagnosed with thyroid cancer via surgical resection, the corresponding final histopathology reports were reviewed. These reports provided the definitive diagnosis of the thyroid cancer histological subtype (Papillary, Follicular, Medullary, or Anaplastic). The generation of these reports followed standard institutional protocols, involving microscopic examination by Consultant Histopathologists, discussion in regular multidisciplinary tumor board meetings, and final reports typically signed off by two consultants to ensure diagnostic accuracy.

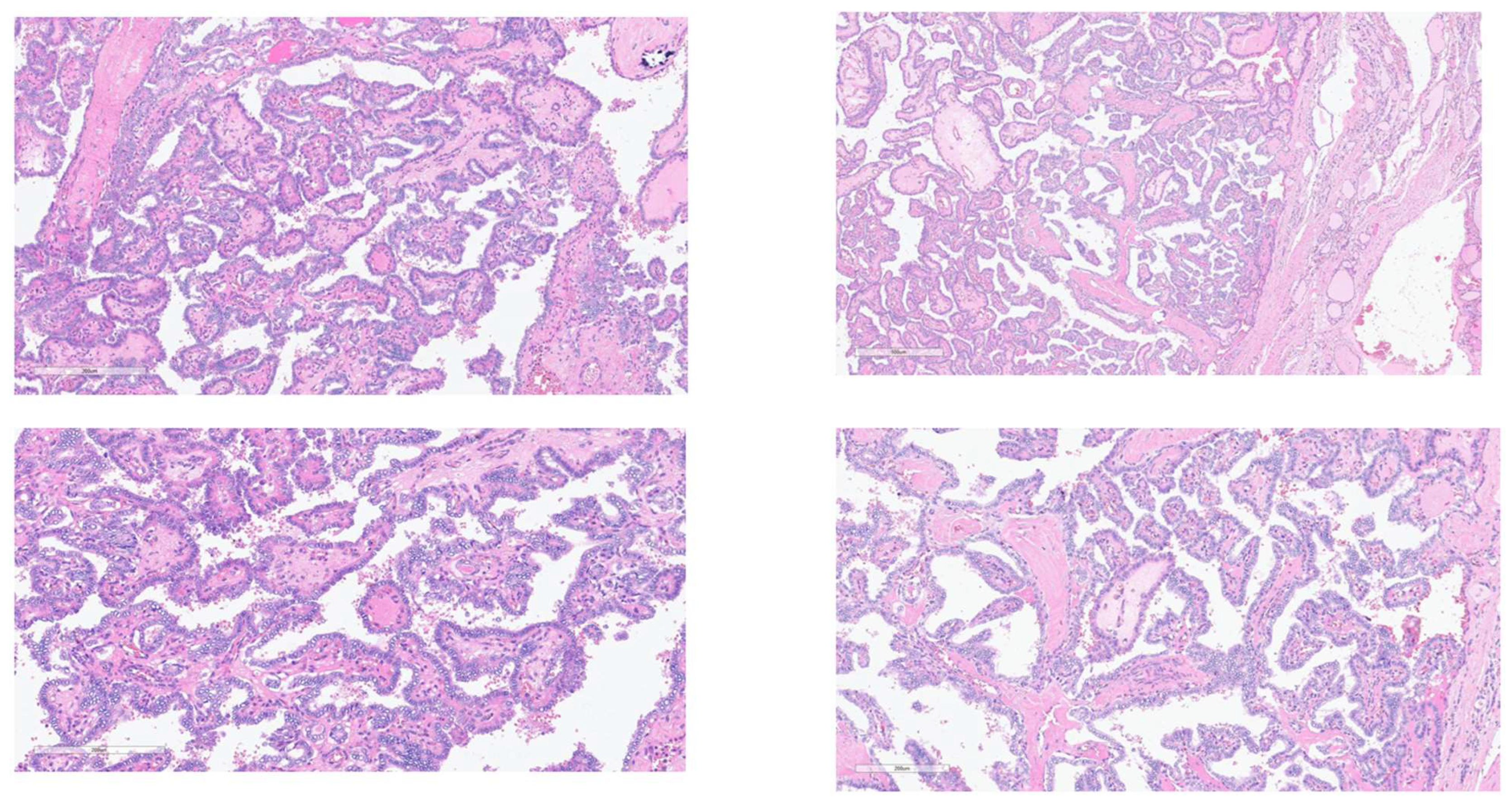

2.4. Histopathology Study (Microscopic Examination for Study Confirmation)

For the purposes of this study and to ensure consistency, representative Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E) stained slides from the surgically resected thyroid tumor tissues of the included cancer patients were re-reviewed by a study-affiliated Consultant Histopathologist. This re-review focused on evaluating the key cellular and architectural characteristics crucial for confirming the histological classification documented in the original reports. Microscopic analysis confirmed features such as branching papillary structures with fibrovascular cores; characteristic nuclear features of PTC (enlarged, ground-glass appearance, crowding, grooves, pseudo inclusions); stromal fibrosis; psammoma bodies; follicular architecture; C-cell origin for MTC; or pleomorphism/necrosis in ATC. Colloid appearance was also noted. Standard tissue processing (10% formalin fixation, paraffin embedding, sectioning, H&E staining) had been performed initially by the hospital laboratory. Representative images confirming typical features are shown in figure 1 in results section.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics (absolute numbers, percentages) summarised the cohort’s age- and sex-structure and the cross-distribution of tumour sub-types with clinical / lifestyle variables across sex-by-age strata as shown in figures in results section. For inference, categorical associations were tested with Pearson’s χ²; the continuity-correction was applied to 2 × 2 tables and Fisher’s exact test was substituted whenever an expected cell count was < 5. Significance was accepted at p < 0.05. Where a comparison was binary, odds ratios (ORs) with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) were provided to convey effect size. We provided Pearson-correlation matrix (N = 205) that explores inter-relationships among all binary study variables (e.g., sex, smoking, OCP use, comorbidities). Cross-tabulates thyroid-cancer histology against first-degree family-history status and reported χ² and likelihood-ratio statistics. Age-group differences were evaluated in histology with χ², likelihood-ratio and linear-by-linear trend tests. Sex disparity in smoking prevalence using χ², continuity-corrected χ², Fisher’s exact and trend statistics were examined, and supplied an OR for the non-smoking cohort. The association between OCP exposure and nodule pattern, and between sex and nodule pattern studied using Pearson χ², continuity correction, likelihood ratio and trend statistics. Results of these investigations were all shown in tables below.

In addition, two purely null 2 × 2 comparisons have been relocated to the Supplement for concision: sex versus family-history status (

Supplementary Table S1) and sex versus obesity (

Supplementary Table S2). These tables retain full cell counts, χ²/Fisher outputs and ORs for transparency but are not reiterated in the main text because their findings are already evident in the correlation matrix.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

Institutional Review Board Statement: The Research Ethical Committee (REC) of University of Ha’il, Saudi Arabia, has Approved this research by the number (H-2024-490), dated REC 4/11/2024. In addition, IRB Approval (Log 2024-117, Dec 16 2024) was obtained from Ha’il Health Cluster, Ha’il to perform this work. The study was conducted in strict adherence to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Given the retrospective nature of data collection from existing medical records, maintaining patient confidentiality and ensuring data privacy were paramount. All collected data were meticulously anonymized or de-identified by removing direct personal identifiers before analysis to prevent the identification of individual participants. Access to the de-identified dataset was strictly limited to the approved research personnel and stored securely on password-protected computers and encrypted file servers. Informed consent for the retrospective use of de-identified medical record data for research purposes was obtained from all participants, as required by the guidelines and regulations stipulated by the approving ethics committees.

3. Results

The study included a cohort of 208 individuals examined for thyroid cancer at a major hospital in Ha'il, Saudi Arabia. The demographic characteristics of the patient population are summarized below.

Demographic Profile of the Study Cohort

The majority of the study participants were female, comprising 70.2% (N=146) of the total cohort, while males accounted for 29.8% (N=62) (

Table 1). The predominant age group was 30-39 years, representing 52.4% (N=109) of the patients. Older age groups included individuals aged 40-49 years (32.7%, N=68) and 50-60 years (14.9%, N=31) (

Table 1).

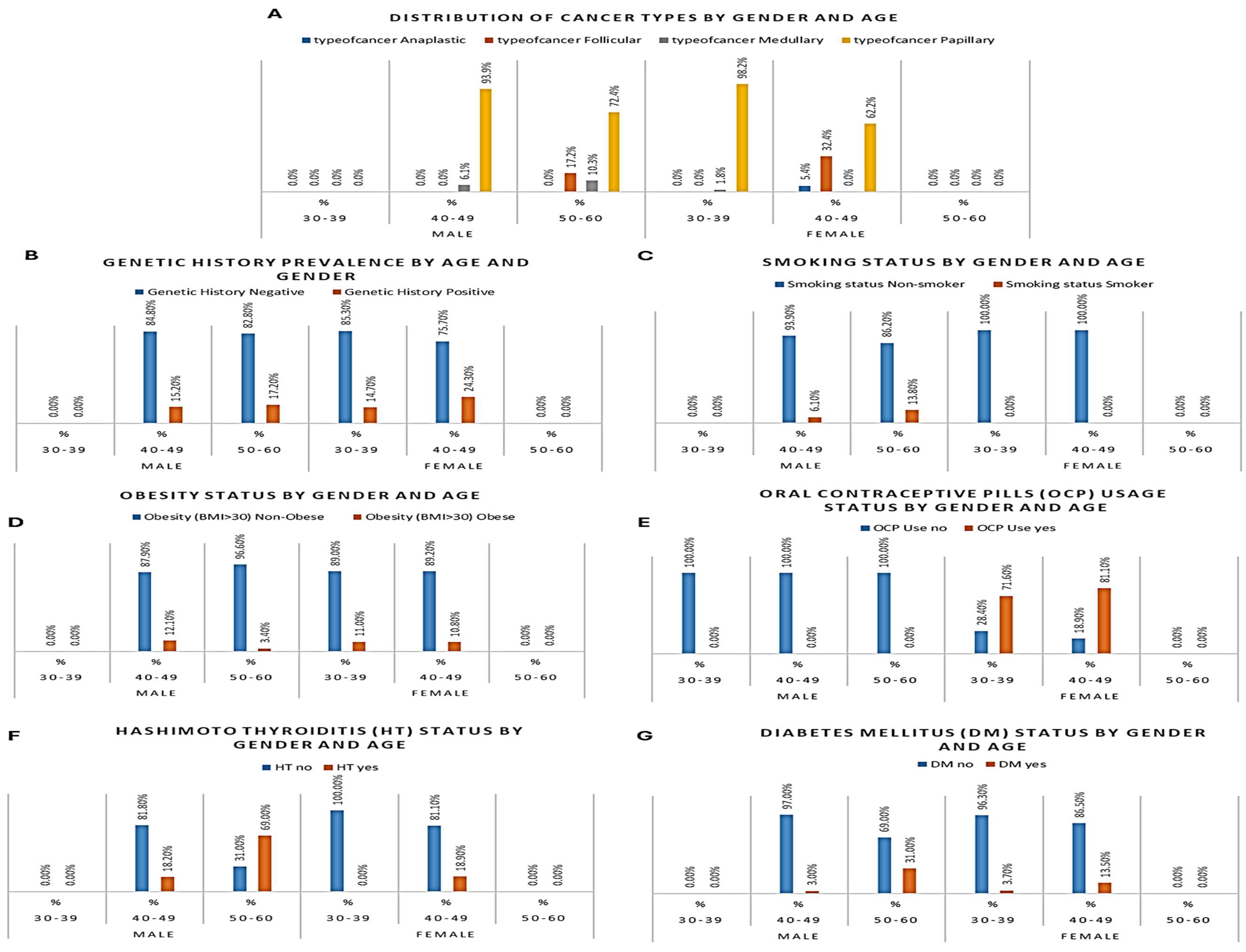

Distribution of Thyroid Cancer Histological Subtypes

Among the 208 patients examined for thyroid cancer, the most frequently diagnosed histological subtype was PTC, accounting for 87.5% (N=182) of all cases. FTC was the second most common, diagnosed in 8.2% (N=17) of patients. MTC represented 3.4% (N=7), and ATC was the least frequent subtype, found in 1.0% (N=2) of the cohort (

Table 2,

Figure 1 and

Figure 2A).

Association of Age and Genetic History with Thyroid Cancer Subtype

A total of 35 participants (16.8%) reported a positive family history of thyroid cancer. Among male patients, five individuals aged 40–49 and five aged 50–60 had a familial background of thyroid malignancy. Among female participants, positive history was more common, with 16 cases recorded in the 30–39 age group and 9 in the 40–49 group. No patients aged 30–39 or 50–60 years among males reported a familial link (

Table 2,

Figure 2B). Overall, females presented a higher frequency of positive genetic background, particularly in the younger age group, aligning with the elevated incidence of papillary thyroid cancer among them.

Gender and Smoking Status

Smoking was observed exclusively among male participants, with 6 out of 62 men (9.7%) identified as current smokers. Two male smokers were aged 40–49, and four were aged 50–60. In contrast, none of the 146 female participants reported smoking (

Table 2,

Figure 2C). This sex-based disparity underscores the need to investigate male-specific risk exposures in thyroid cancer. The association between male smoking behavior and medullary or follicular histology types in older patients may reflect compounded environmental and biological risk.

Obesity and Age-Specific Trends

Obesity, defined as BMI > 30 kg/m², was identified in 21 patients, representing 10.1% of the total sample. Among males, 5 patients were obese, including four in the 40–49 group and one in the 50–60 group. In female participants, obesity was more frequent with 12 cases in the 30–39 group and 4 in the 40–49 group (

Table 2,

Figure 2D).

Oral Contraceptive Pill (OCP) Use Among Women

OCP use was recorded exclusively in female participants and was most prevalent among women aged 30–39, where 78 out of 109 (71.6%) reported current or past use. In the 40–49 age group, 30 out of 37 (81.1%) females used OCPs, whereas no OCP use was reported among women aged 50–60 (

Table 2,

Figure 2E).

Hypertension (HT) by Gender and Age

HT was present in 33 participants (15.9%). Male patients showed a greater burden, particularly in older age. Six out of 33 men aged 40–49 (18.2%) and twenty out of 29 men aged 50–60 (69.0%) was diagnosed with HT. Among females, HT was less common, with 7 cases all occurring in the 40–49 group (18.9%). No female cases were observed in other age groups (

Table 2,

Figure 2F).

Diabetes Mellitus (DM) Prevalence Across Subgroups

DM was identified in 19 out of 208 participants (9.1%). Among males, DM was most frequent in the oldest group, with 9 out of 29 men aged 50–60 (31.0%) and one individual aged 40–49 diagnosed with diabetes. In females, 4 women aged 30–39 and 5 aged 40–49 had DM, accounting for 3.7% and 13.5% of their respective groups (

Table 2,

Figure 2G).

Inter-variable correlation profile within the cohort

Pearson’s matrix analysis (

Table 3) revealed a tightly inter-woven pattern linking sex, age, lifestyle habits and cardiometabolic comorbidities. Female sex correlated strongly with oral-contraceptive exposure (r = 0.646, p < 0.001), reflecting the reproductive-age composition of the cohort, and, conversely, women were markedly less likely to smoke (r = –0.264, p < 0.001), to be hypertensive (r = –0.463, p < 0.001) or to have diabetes (r = –0.160, p = 0.021). Age emerged as a central driver: as participants grew older, the probability of hypertension (r = 0.598, p < 0.001), diabetes (r = 0.290, p = 0.013) and smoking (r = 0.252, p < 0.001) increased, whereas use of oral contraceptives declined sharply (r = –0.474, p < 0.001); the strong inverse correlation between age and gender (r = –0.771, p < 0.001) simply reflects that the youngest stratum was predominantly female. Hypertension and diabetes clustered together (r = 0.412, p < 0.001), underscoring their shared metabolic background, and women who used oral contraceptives were modestly less likely to be hypertensive (r = –0.273, p < 0.001) or diabetic (r = –0.137, p = 0.050). In contrast, obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg m⁻²), first-degree family history of thyroid cancer, self-reported environmental exposure and alcohol intake showed no meaningful correlation with any other variable (all p > 0.05), suggesting that these factors act independently of the demographic and lifestyle clusters identified above.

The detailed 2 × 2 contingency analyses that underpin two null findings—(i) the absence of a sex difference in the prevalence of a positive family history and (ii) the lack of association between sex and obesity—are now provided in

Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, respectively. In brief, 16.1 % of men versus 17.1 % of women reported an affected first-degree relative (χ² = 0.031, p = 0.861; odds ratio = 1.07, 95 % CI 0.48–2.40), while obesity affected 8.1 % of men and 11.0 % of women (χ² = 0.402, p = 0.526; odds ratio = 1.40, 95 % CI 0.49–4.02).

Relationship Between Family History and Histological Subtype

When thyroid-cancer subtype was cross-tabulated against family-history status, a statistically significant association emerged. Among the 35 patients with a positive family history, PTC remained predominant (29 cases, 82.9 %), but the relative frequency of MTC was markedly higher (4 cases, 11.4 %) than in the history-negative group (3 cases, 1.7 %). Conversely, ACT was observed only in patients without a reported familial background. Pearson’s chi-square test produced χ² = 8.949 (p = 0.030), confirming that tumour histology varies with hereditary status (

Table 4).

Age-Specific Variation in Thyroid-Cancer Subtype

Histological distribution differed significantly across age groups. In patients aged 30–39 years, PTC accounted for 98.2 % of tumors (107/109), with only two medullary cases and no follicular or anaplastic tumors recorded. In the 40–49 year group, the proportion of PTC fell to 77.1 % (54/70) while follicular carcinoma rose sharply to 17.1 % (12/70); this age band also contained the study’s only two anaplastic tumors. Among patients aged 50–60 years, papillary carcinoma constituted 72.4 % of diagnoses (21/29) and follicular carcinoma 17.2 % (5/29), with three medullary tumors completing the profile. Pearson’s chi-square test confirmed a robust association between age and histology (χ² = 30.7, p < 0.001), and the linear-by-linear component (χ² = 19.8, p < 0.001) demonstrated a graded shift from exclusively papillary disease in younger adults toward greater histological heterogeneity—particularly increased follicular representation—as age advances (

Table 5).

Gender and Smoking Status

The crosstabulation of gender versus smoking status confirmed that tobacco use in this cohort was restricted to males. All six smokers were men, whereas all 146 women were non-smokers. Pearson’s χ² test yielded a value of 14.549 with 1 degree of freedom (p < 0.001), and Fisher’s exact test produced the same two-sided probability (p = 0.001), demonstrating a highly significant association between sex and smoking behaviour. The risk estimate for the non-smoking cohort gave an odds ratio of 0.903 (95 % CI 0.833–0.980), underscoring that males were considerably more likely to smoke than females within this study population (

Table 6).

OCP, Gender and Thyroid-Nodule Pattern

Crosstabulation of nodule morphology with OCP exposure revealed a highly significant association. Among women who reported OCP use (n = 110), single nodules predominated (102 single vs 8 multinodular). In contrast, non-users (n = 98) exhibited a markedly higher proportion of multinodular disease (32 multinodular vs 66 single). Pearson’s χ² test confirmed the difference (χ² = 21.5, p < 0.001), indicating that OCP exposure correlated with a lower likelihood of presenting with multiple nodules (

Table 7).

Gender also influenced nodule profile. Multinodular architecture was considerably more frequent in men (27/62, 43.5 %) than in women (13/146, 8.9 %). The association between sex and nodule type was highly significant (χ² = 33.6, p < 0.001). Linear-by-linear trend statistics supported a graded shift toward multinodularity in males (

Table 7).

Taken together, these data suggest that exogenous hormonal exposure may modulate nodule multiplicity in women, while intrinsic sex-related factors predispose men to a multinodular presentation—differences that could influence surgical planning and long-term surveillance strategies.

4. Discussion

The persistent increase in thyroid cancer incidence globally necessitates a granular understanding of its contributing factors across diverse populations. This study, focusing on a cohort from Ha'il, Saudi Arabia, provides a critical regional perspective on the interplay of demographic variables, prevalent health conditions, lifestyle elements, and specific thyroid tumor characteristics. By examining these associations, the findings contribute to the growing body of evidence characterizing thyroid cancer epidemiology and offer insights pertinent to public health strategies and clinical management within this specific geographic context.

The demographic profile observed in our cohort, marked by a significant female preponderance and a peak incidence in individuals aged 30-39 years, is highly congruent with well-established global epidemiological patterns for differentiated thyroid carcinoma (DTC) [

26,

27]. The striking female predilection continues to suggest that sex-specific biological factors, likely hormonal influences, play a pivotal role in susceptibility. Although the precise molecular mechanisms remain under investigation, the expression of estrogen receptors in thyroid follicular cells and experimental evidence demonstrating estrogen's capacity to stimulate thyroid cell proliferation offer plausible biological underpinnings for this disparity [

28,

29]. The concentration of diagnoses within the younger adult age range (30-39 years) also aligns with trends noted in numerous other populations, underscoring that thyroid cancer, particularly PTC, is a malignancy that frequently affects individuals in their prime, emphasizing the importance of awareness and accessible diagnostic pathways for this demographic group [

30,

31].

A key finding illuminated by this study is the statistically significant association between advancing age and a discernible shift in the distribution of thyroid cancer histological subtypes. While PTC predominated across all age groups, consistent with its status as the most common thyroid malignancy [

32,

33], our data show a relatively higher proportion of FTC and MTC in older age brackets (40-49 and 50-60 years) compared to the youngest cohort (30-39 years). This observation reinforces the clinical understanding that non-PTC subtypes, some of which (like poorly differentiated or anaplastic carcinoma, or certain FTCs) carry a less favorable prognosis, become relatively more frequent with increasing age [

34]. The biological basis for this age-related histological shift is likely multifactorial. It could reflect the accumulation of distinct somatic genetic alterations over an individual's lifetime, potentially leading to the emergence of tumors with different molecular drivers and developmental pathways compared to the typical

BRAF V600E-driven PTC prevalent in younger patients or

RAS-driven FTC more common in middle age [

35]. Age-related changes in the thyroid gland's microenvironment, including inflammation, fibrosis, or alterations in hormonal signaling, might also contribute to favoring the development of certain histological types or influencing tumor evolution [

36]. This finding has direct implications for clinical practice, suggesting that in older patients presenting with thyroid nodules, clinicians should maintain a heightened index of suspicion for non-PTC histologies and consider comprehensive diagnostic approaches, potentially including broader molecular testing panels, to accurately identify the subtype and guide appropriate management.

Our investigation also confirmed the critical role of genetic predisposition, specifically demonstrating a statistically significant association between a positive first-degree family history of thyroid disease and a higher relative frequency of MTC. This finding aligns with the well-documented genetic basis of MTC, where germline mutations in the

RET proto-oncogene are responsible for hereditary forms, such as those seen in Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type 2 syndromes [

37]. Higher proportion of MTC observed in patients with a family history in our cohort underscores the critical importance of thorough family history collection for all individuals undergoing thyroid evaluation and the necessity of genetic counseling and cascade testing for specific mutations like RET proto-oncogene in families affected by MTC.

Our data revealed a statistically significant association between gender and thyroid nodule type, with females showing a markedly higher propensity for single nodules compared to males [

38]. Furthermore, within the female cohort, there was a statistically significant association between OCP use and thyroid nodule type; females who reported OCP use demonstrated a higher likelihood of presenting with single nodules compared to female non-users. While previous research has explored the link between hormonal factors and overall thyroid cancer risk or nodule prevalence, less attention has been paid to their influence on nodule multiplicity [

39,

40]. Our observation suggests that both inherent sex-related biological differences and potentially exogenous hormonal exposure from OCPs might influence the biological processes underlying thyroid hyperplasia or autonomous growth, potentially favoring the development of a single dominant lesion compared to a multinodular goiter. This could hypothetically involve differential effects on cellular proliferation, apoptosis, or local growth factor production within the thyroid parenchyma influenced by estrogen levels [

41]. Given the prevalence of thyroid nodules and OCP use, particularly in the younger female demographic, as also reflected in our correlation analyses showing OCP use strongly associated with younger age and female sex, these potential associations, if validated in larger, appropriately designed studies, could represent a potential factors to consider during the clinical evaluation and imaging interpretation of thyroid nodules, potentially influencing the pre-test probability assigned to single versus multiple lesions, although it should not supersede established ultrasound risk stratification systems and cytological evaluation.

Conversely, several factors frequently cited in the global literature as potentially associated with thyroid cancer risk, including smoking status, obesity (BMI ≥ 30), HT, and DM, did not reach statistical significance in their association with the overall presence or specific subtype of thyroid cancer in our specific cohort. This finding appears to contrast with numerous large-scale epidemiological studies and meta-analyses that have reported varying degrees of association, particularly linking obesity and DM to a modest increase in thyroid cancer risk [

14,

42]. It is important to distinguish this lack of direct association with cancer characteristics from the inter-relationships among these variables themselves within our cohort. Our correlation analysis did reveal significant clustering: for example, hypertension and diabetes were strongly correlated with each other and with increasing age, and smoking clustered significantly with male gender, older age, and hypertension. Obesity and Hashimoto's thyroiditis, however, showed few significant correlations with other variables. The lack of detected significance in the primary cancer association analyses might be influenced by several factors. The cross-sectional design, relying on a cohort undergoing evaluation for thyroid conditions rather than a case-control comparison with healthy individuals, inherently limits the capacity to estimate the incidence risk associated with these factors. The sample size, while providing insights into specific associations, might have been insufficient to detect subtle or moderate effects of these prevalent conditions or lifestyle habits on the overall likelihood of being diagnosed with thyroid cancer within this specific population. Furthermore, the retrospective nature of data collection meant relying on existing medical record documentation, which may not capture the duration, severity, control, or specific characteristics of conditions like HT and DM, or provide granular detail on smoking history or longitudinal changes in BMI, all of which could modify their true association with cancer risk. The unique genetic and environmental background or the specific prevalence of these factors within the Ha'il population compared to other globally studied cohorts might also contribute to the observed differences in their link to cancer. Despite the lack of a direct statistically significant link to cancer outcomes in this specific cohort, the substantial body of evidence from the broader literature regarding the links between obesity, DM, and potentially other lifestyle factors and increased thyroid cancer risk highlights the continued importance of addressing these modifiable factors in public health initiatives aimed at reducing the overall cancer burden.

The findings from this study carry several potential implications for clinical practice and public health in Ha'il and possibly other regions with similar demographic and epidemiological profiles. The recognition of the age-dependent shift towards a higher relative proportion of non-PTC subtypes in older patients emphasizes the need for clinicians to be particularly vigilant in their diagnostic evaluation of thyroid nodules in this age group, considering a broader differential diagnosis and utilizing appropriate molecular or advanced imaging techniques when indicated. The observed association between gender and OCP use with thyroid nodule multiplicity, while requiring validation, suggests that these factors might influence nodule morphology, a point that could be noted during ultrasound evaluation and potentially influence clinical follow-up strategies, although it should not replace established malignancy risk assessment. Public health strategies should continue to emphasize the importance of maintaining a healthy weight and managing conditions like diabetes and hypertension, based on the robust global evidence linking them to increased thyroid cancer risk and their prevalence as age-related comorbidities noted in our cohort, even if a significant association with cancer was not detected in this specific study's primary analysis.

This study's limitations, including its single-center, cross-sectional, and retrospective nature, restrict the ability to infer causality, are subject to data completeness from medical records, and limit generalizability. Future research endeavors in this region should aim for prospective, large-scale, and multi-center designs to capture more detailed data on a wider range of potential risk factors, including specific environmental exposures (e.g., quantifiable radiation history, iodine intake levels), detailed hormonal histories (including menopausal status and HRT), and more granular information on lifestyle habits. Incorporating biological sample collection for genetic and molecular profiling would provide invaluable mechanistic insights. Longitudinal follow-up would allow for the assessment of risk factors in relation to cancer incidence and progression. Although this work provides significant insights, albeit more wide comprehensive studies are crucial for validating the novel associations identified here and for developing tailored prevention and management strategies for thyroid cancer in this population.

5. In conclusion, this study from Ha'il, Saudi Arabia, provides a valuable contributions of regional profiles in understanding of thyroid cancer epidemiology. It confirms key global demographic trends and the predominance of PTC. More significantly, it reveals a notable age-dependent shift in the distribution of histological subtypes towards a higher relative frequency of non-PTCs in older patients and identifies significant associations linking gender and OCP use with thyroid nodule multiplicity, which warrants further investigation. The strong link found between family history and MTC reinforces the critical need for genetic assessment in appropriate contexts. While several established risk factors did not show significant associations with cancer characteristics in this specific cohort's primary analyses, correlation analysis highlighted their interplay with age and sex within the population studied. This research underscores the complex, multi-factorial nature of thyroid cancer and lays the groundwork for future targeted investigations to enhance our understanding and ultimately improve patient outcomes in this region.

Supplementary Materials

All data generated from this study is included in the manuscript. In ddition, two supplementary tables were uploaded along with the manuscript. Furthermore, a blank informed consent was uploaded with this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Kamaleldin B Said; Data curation, Ruba M. Elsaid Ahmed, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Arwa A Alotaibi, Kareemah Alshurtan, Kawthar Alshammari, Fayez Alfouzan, Maram Alanazi , Amal Alshammari, Fahad Alshammary, Mohammad Alzugahibi , Alfatih Alnajib, Manal Alshammari and Abdullah Alotaibi ; Formal analysis, Ruba M. Elsaid Ahmed, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Arwa A Alotaibi, Kareemah Alshurtan, Kawthar Alshammari, Fayez Alfouzan, Maram Alanazi , Amal Alshammari, Fahad Alshammary, Mohammad Alzugahibi , Alfatih Alnajib, Manal Alshammari and Abdullah Alotaibi ; Funding acquisition, Kamaleldin B Said; Investigation, Ruba M. Elsaid Ahmed and Kamaleldin B Said; Methodology, Ruba M. Elsaid Ahmed, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Arwa A Alotaibi, Kareemah Alshurtan, Kawthar Alshammari, Fayez Alfouzan, Maram Alanazi , Amal Alshammari, Fahad Alshammary, Mohammad Alzugahibi , Alfatih Alnajib, Manal Alshammari and Abdullah Alotaibi ; Project administration, Kamaleldin B Said and Khalid F Alshammari; Resources, Ruba M. Elsaid Ahmed, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Arwa A Alotaibi, Kareemah Alshurtan, Kawthar Alshammari, Fayez Alfouzan, Maram Alanazi , Amal Alshammari, Fahad Alshammary, Mohammad Alzugahibi , Alfatih Alnajib, Manal Alshammari and Abdullah Alotaibi ; Software, Ruba M. Elsaid Ahmed, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Arwa A Alotaibi, Kareemah Alshurtan, Kawthar Alshammari, Fayez Alfouzan, Maram Alanazi , Amal Alshammari, Fahad Alshammary, Mohammad Alzugahibi , Alfatih Alnajib, Manal Alshammari and Abdullah Alotaibi ; Supervision, Ruba M. Elsaid Ahmed and Kamaleldin B Said; Validation, Ruba M. Elsaid Ahmed, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Arwa A Alotaibi, Kareemah Alshurtan, Kawthar Alshammari, Fayez Alfouzan, Maram Alanazi , Amal Alshammari, Fahad Alshammary, Mohammad Alzugahibi , Alfatih Alnajib, Manal Alshammari and Abdullah Alotaibi ; Visualization, Ruba M. Elsaid Ahmed, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Arwa A Alotaibi, Kareemah Alshurtan, Kawthar Alshammari, Fayez Alfouzan, Maram Alanazi , Amal Alshammari, Fahad Alshammary, Mohammad Alzugahibi , Alfatih Alnajib, Manal Alshammari and Abdullah Alotaibi ; Writing – original draft, Kamaleldin B Said; Writing – review & editing, Ruba M. Elsaid Ahmed, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Arwa A Alotaibi, Kareemah Alshurtan, Kawthar Alshammari, Fayez Alfouzan, Maram Alanazi , Amal Alshammari, Fahad Alshammary, Mohammad Alzugahibi , Alfatih Alnajib, Manal Alshammari and Abdullah Alotaibi .

Funding

This research was funded by Scientific Research, Deanship at University of Hail, Saudi Arabia through project number GR-25 006.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Research Ethical Committee (REC) of University of Ha’il, Saudi Arabia, has Approved this research by the number (H-2024-490), dated REC 4/11/2024. In addition, IRB Approval (Log 2024-117, Dec 16 2024) was obtained from Ha’il Health Cluster, Ha’il to perform this work. The study was conducted in strict adherence to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Given the retrospective nature of data collection from existing medical records, maintaining patient confidentiality and ensuring data privacy were paramount. All collected data were meticulously anonymized or de-identified by removing direct personal identifiers before analysis to prevent the identification of individual participants. Access to the de-identified dataset was strictly limited to the approved research personnel and stored securely on password-protected computers and encrypted file servers.

Informed Consent Statement

“Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.” A blank form of the informed consent is uploaded along with this manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated from this work is included in the manuscript submitted. Two supplementary tables are uploaded as Supplementary Material along with this manuscript. There is no data about this work available anywhere else.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research and graduate studies at the University of Ha’il. This research has been funded by Scientific Research Deanship at University of Hail, Saudi Arabia through project number GR-25 006.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, M.; Li, N.; Tian, T.; Wu, Y.; et al. Global burden of thyroid cancer from 1990 to 2017. JAMA network open. 2020, 3, e208759–e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassol, C.A.; Asa, S.L. Molecular pathology of thyroid cancer. Diagnostic histopathology. 2011, 17, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filetti, S.; Durante, C.; Hartl, D.; Leboulleux, S.; Locati, L.; Newbold, K.; et al. Thyroid cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology. 2019, 30, 1856–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Ham, J.; Po, J.W.; Niles, N.; Roberts, T.; Lee, C.S. The Genomic Landscape of Thyroid Cancer Tumourigenesis and Implications for Immunotherapy. Cells. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prete, A.; Borges de Souza, P.; Censi, S.; Muzza, M.; Nucci, N.; Sponziello, M. Update on Fundamental Mechanisms of Thyroid Cancer. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2020; Volume 11 - 2020.

- Sahakian, N.; Castinetti, F.; Romanet, P. Molecular basis and natural history of medullary thyroid cancer: it is (almost) all in the RET. Cancers. 2023, 15, 4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leandro-García, L.J.; Landa, I. Mechanistic Insights of Thyroid Cancer Progression. Endocrinology. 2023, 164, bqad118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iglesias, M.L.; Schmidt, A.; Ghuzlan, A.A.; Lacroix, L.; Vathaire, F.; Chevillard, S.; et al. Radiation exposure and thyroid cancer: a review. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2017, 61, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zupunski, L.; Ostroumova, E.; Drozdovitch, V.; Veyalkin, I.; Ivanov, V.; Yamashita, S.; et al. Thyroid Cancer after Exposure to Radioiodine in Childhood and Adolescence: (131)I-Related Risk and the Role of Selected Host and Environmental Factors. Cancers (Basel). 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman-Neill, R.J.; Brenner, A.V.; Little, M.P.; Bogdanova, T.I.; Hatch, M.; Zurnadzy, L.Y.; et al. RET/PTC and PAX8/PPARγ chromosomal rearrangements in post-Chernobyl thyroid cancer and their association with iodine-131 radiation dose and other characteristics. Cancer. 2013, 119, 1792–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotta, V.; Malandrino, P.; Russo, M.; Panariello, I.; Ionna, F.; Chiofalo, M.G.; et al. Fathoming the link between anthropogenic chemical contamination and thyroid cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2020, 150, 102950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macedo, S.; Teixeira, E.; Gaspar, T.B.; Boaventura, P.; Soares, M.A.; Miranda-Alves, L.; et al. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals and endocrine neoplasia: A forty-year systematic review. Environ Res. 2023, 218, 114869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.-L.; Li, L.-R.; Yu, X.-Z.; Zhan, L.; Xu, Z.-L.; Li, J.-J.; et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and clinicopathological features of papillary thyroid cancer. Endocrine. 2022, 75, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, Z.; Hassanzadeh, J.; Ghaem, H. Relationship of modifiable risk factors with the incidence of thyroid cancer: a worldwide study. BMC Research Notes. 2025, 18, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Chai, Y.J.; Yi, K.H. Effect of Cigarette Smoking on Thyroid Cancer: Meta-Analysis. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2021, 36, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buitrago-Gómez, N.; García-Ramos, A.; Salom, G.; Cuesta-Castro, D.P.; Aristizabal, N.; Hurtado, N.; et al. Sociodemographic, clinical and ultrasound characterization of thyroid nodule pathology and its association with malignancy in a Colombian high-complexity center]. Semergen. 2023, 49, 102015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Lee, C.Y.; Hwang, I.; You, S.H.; Park, S.W.; Lee, B.; et al. Malignancy risk stratification of thyroid nodules according to echotexture and degree of hypoechogenicity: a retrospective multicenter validation study. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 16587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.L.; Yang, H.Y.; Liu, R.B.; Liang, M.; Han, P.; Xu, X.L.; et al. Fine needle aspiration biopsy indications for thyroid nodules: compare a point-based risk stratification system. Eur Radiol. 2019, 29, 4871–4878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fighera, T.M.; Perez, C.L.; Faris, N.; Scarabotto, P.C.; da Silva, T.T.; Cavalcanti, T.C.; et al. TSH levels are associated with increased risk of thyroid carcinoma in patients with nodular disease. Endokrynol Pol. 2015, 66, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Disharoon, M.; Song, Z.; Gillis, A.; Fazendin, J.; Lindeman, B.; et al. Incidental but Not Insignificant: Thyroid Cancer in Patients with Graves Disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2024, 238, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.F.; Ge, H.; Tang, N.; Qin, Z.E.; Tan, H.L. Prevalence of Hashimoto's thyroiditis in papillary thyroid cancer and its association with aggressive characteristics. Gland Surg. 2025, 14, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushchayeva, Y.S.; Kushchayev, S.V.; Startzell, M.; Cochran, E.; Auh, S.; Dai, Y.; et al. Thyroid Abnormalities in Patients With Extreme Insulin Resistance Syndromes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019, 104, 2216–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Grady, T.J.; Rinaldi, S.; Michels, K.A.; Adami, H.O.; Buring, J.E.; Chen, Y.; et al. Association of hormonal and reproductive factors with differentiated thyroid cancer risk in women: a pooled prospective cohort analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2024, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.C.; Li, X.; Shan, R.; Mei, F.; Song, S.B.; Chen, J.; et al. Pregnancy and Progression of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: A Propensity Score-Matched Retrospective Cohort Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024, 109, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Tang, J.; Kong, D.; Cui, Q.; Wang, K.; Gong, Y.; et al. Impact of Gender and Age on the Prognosis of Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma: a Retrospective Analysis Based on SEER. Horm Cancer. 2018, 9, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.X.; Pang, P.; Wang, F.L.; Tian, W.; Luo, Y.K.; Huang, W.; et al. Dynamic profile of differentiated thyroid cancer in male and female patients with thyroidectomy during 2000-2013 in China: a retrospective study. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 15832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derwahl, M.; Nicula, D. Estrogen and its role in thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014, 21, T273–T283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.Z.; Zheng, L.L.; Chen, K.H.; Wang, R.; Yi, D.D.; Jiang, C.Y.; et al. Serum sex hormones correlate with pathological features of papillary thyroid cancer. Endocrine. 2024, 84, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, N.; Bell, K.J.L.; Hsiao, V.; Fernandes-Taylor, S.; Alagoz, O.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Prevalence of Subclinical Papillary Thyroid Cancer by Age: Meta-analysis of Autopsy Studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022, 107, 2945–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Devesa, S.S.; Sosa, J.A.; Check, D.; Kitahara, C.M. Trends in Thyroid Cancer Incidence and Mortality in the United States, 1974-2013. JAMA. 2017, 317, 1338–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.; Giriyan, S.S.; Rangappa, P.K. Clinicopathological profile of papillary carcinoma of thyroid: A 10-year experience in a tertiary care institute in North Karnataka, India. Indian J Cancer. 2017, 54, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, D.T.; Haymart, M.R.; Miller, B.S.; Gauger, P.G.; Doherty, G.M. The most commonly occurring papillary thyroid cancer in the United States is now a microcarcinoma in a patient older than 45 years. Thyroid. 2011, 21, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, N.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Cui, A.; Tan, S.; Bai, N. Age Influences the Prognosis of Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer Patients. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021, 12, 704596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romei, C.; Elisei, R. A Narrative Review of Genetic Alterations in Primary Thyroid Epithelial Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolly, L.A.; Novitskiy, S.; Owens, P.; Massoll, N.; Cheng, N.; Fang, W.; et al. Fibroblast-Mediated Collagen Remodeling Within the Tumor Microenvironment Facilitates Progression of Thyroid Cancers Driven by BrafV600E and Pten Loss. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 1804–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Liu, J.; Cheng, S.W.; Wang, B.; Yang, R.; Peng, L. Hereditary medullary thyroid carcinoma: the management dilemma. Fam Cancer. 2012, 11, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, Q.-L.; Davies, L. Thyroid cancer incidence differences between men and women. Current Opinion in Endocrine and Metabolic Research. 2023, 31, 100472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoveniuc, G.; Jonklaas, J. Thyroid nodules. Med Clin North Am. 2012, 96, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Park, Y.R.; Lim, D.J.; Yoon, K.H.; Kang, M.I.; Cha, B.Y.; et al. The relationship between thyroid nodules and uterine fibroids. Endocr. J. 2010, 57, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, T.; Ma, L.; Chang, W. Signal Pathway of Estrogen and Estrogen Receptor in the Development of Thyroid Cancer. Front Oncol. 2021, 11, 593479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Qian, J. Association of diabetes mellitus with thyroid cancer risk: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Medicine. 2017, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).