1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Rationale

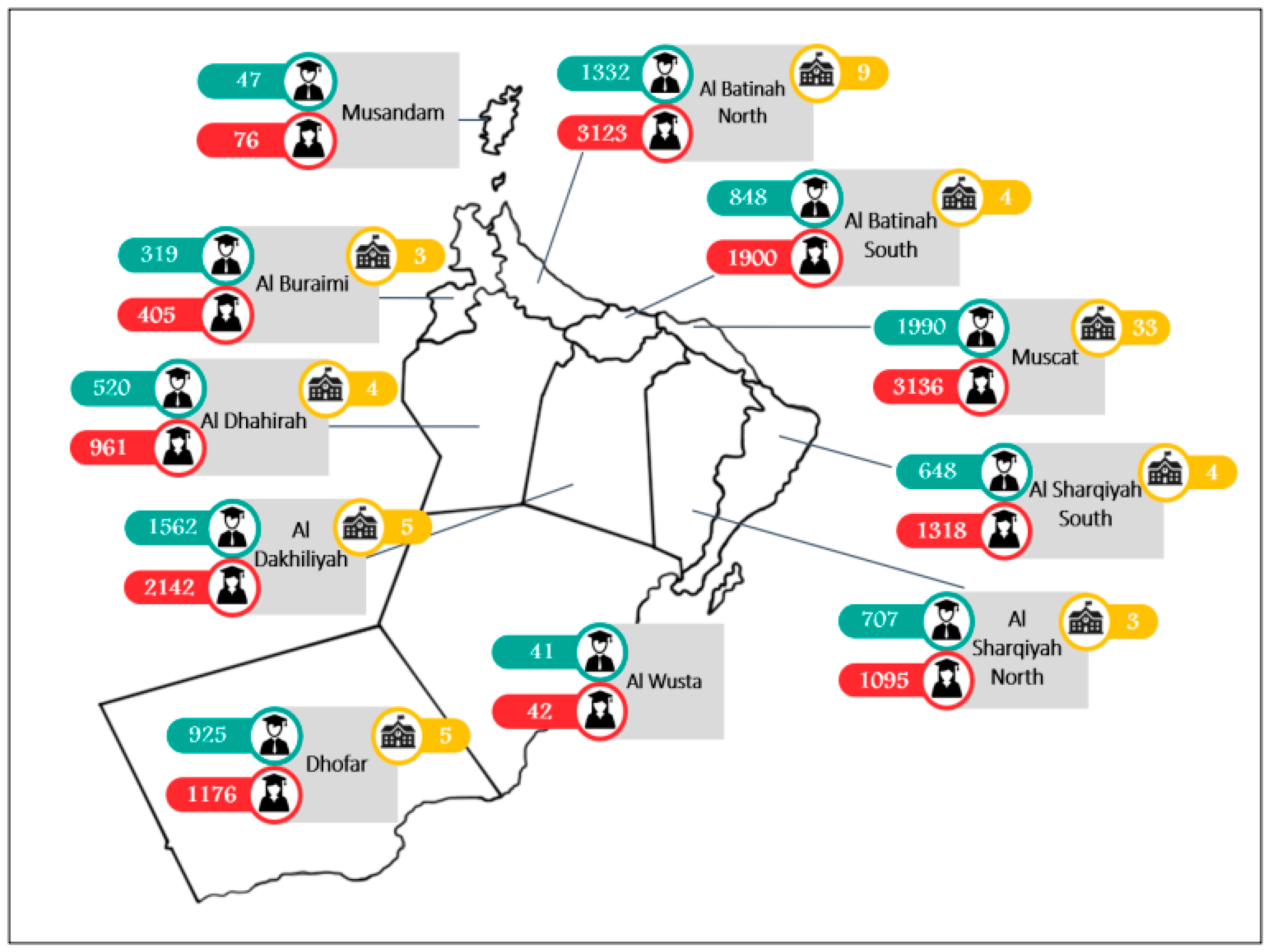

The Sultanate of Oman, with a population of more than 4.5 million is distinguished by its sustainable economic climate, outstanding infrastructure and skilled human resources. While one of the key sectors of the Omani economy is the oil and gas industry, the Sultanate of Oman has a dynamic and diversification of economy strategy covering various sectors including manufacturing, agriculture, mining, textiles, retail, tourism, logistic, fishing, among others. Whereas the education and health sectors have played a vital role in Oman's growth and prosperity. They have been the primary drivers of growth and achievement of the economy strategy goals including Oman vision 2040 (2020). Oman has realized that education reform including curricula, teaching and learning processes is its pillar towards the quality of education. The sustainability of economic growth, human resources development through improving the education technologies was set as the important aspect in Oman Vision 2040.(Oman Vision 2040, 2020). Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research and Innovation institutions in Oman are accounted responsible to promote higher education in the public and private sectors as per Royal Decree number (2/1994) released in the government document of the Sultanate of Oman. Multiple objectives concern academic, research, community development and were fully described in the documents using innovative approaches in higher education (Oman Vision 2040, 2020). As a result of population growth and the diversity of the different sectors, the number of institutes has been expanded in Oman. According to the academic year (2017/2018) statistics, the higher education system comprises of 70 educational institutions with 41 and 29 government and private institutions, respectively as per National Center for Statistics and Information (NCSI) (Home – NCSI PORTAL, 2020). The remarkable expansion was witnesses following the year 2018. The geographical distribution of universities and colleges across governorates of the Sultanate is shown in

Figure 1.

In the present scenario, education is one of the sectors that has been forced to dramatically recalibrate its approach and operations. Moreover, the sudden changes that had to be implemented to accommodate the necessary safety concerns stemming from the pandemic have led to frustration and difficulties from both students and faculty (Ali, 2020).

Raza, S.A.et al (2022) have done a research work in the Blackboard Learning System (BLS) which is an online platform designed for e-learning employed by higher education institutes that facilities students to continue learning and educational activities. This study explores the acceptance and use of Blackboard learning system (BLS) in Pakistan. The study provides that the BLS is highly suitable in online learning environment, however, the research concluded that the similar type of research should be conducted in different regions and boundaries in Pakistan to find the efficiency of the system. Ali,M et al ( 2018) examined the university students’ acceptance of e-learning systems in Pakistan. The results revealed that university students’ acceptance of the e-learning system reasonably well in Pakistan. This research concluded that work life quality (WLQ) and facilitating conditions (FC) have a greater influence on the actual use of the e-learning system. The study has also provided valuable implications for academics and practitioners for ways to enhance the acceptance of the e-learning system in the higher education of Pakistan. As per Janet et al (2021) research work, “educational reforms implemented in Thai education system is a burning question of the current state of schools in the country”. This research work described the progress along learning resources, several changes in daily routines and school activities, more comprehensive classroom policies that include social and cultural rules, and multi-faceted functions of Thai teachers. Aslam,S et al (2021) have done a research work in online learning at a medical college in china. This study aimed to investigate international medical students’ (IMS) experiences of online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic in china. Among 1,107 respondents in this study, a total of 67.8% were males, and the majority (63.1%) of the IMS were in the age group of 21–23 years. The results showed that more than half of the respondents reported their Internet connection quality as poor to average. Poor Internet connection severely affected IMS online learning experience. Moreover, the study has concluded that the online learning is not suitable for medical education because of the involvement of physical examination of the body in the practical classes. Aslam, S., et al 2021 has published a paper which gives the challenges in implementing the online learning during the pandemic time. This paper has revealed various challenges in implementing the online education in teaching and learning in the developing countries. These papers have shown a positive feedback in implementing online teaching and learning.

However, quality checking is an important process in the implementation of online education system. Therefore, this paper sets out to apply principles of Total Quality Management (TQM) on online learning through the use of Quality Function Deployment (QFD) as a way of identifying the main hurdles and areas of improvements that need to be addressed in the case of HEIs in Oman. Total Quality Management concern about the management of quality assurance in all levels of organization. Many researchers have done various research works in the implementation of TQM including in educational institute. The TQM approach uses many quality tools to foster improvements in an organization. Among TQM tools, QFD is a structured and an important tool in TQM implementation that uses engineering and management charts to transform customer requirements into process characteristics.

1.2. Problem Statement

It is clear that the world is moving towards digitalization including teaching and learning in HEIs. In this regard, it is required to maintain quality of education before implementing any of the digital techniques in teaching and learning. In this paper, the hypothesis is set up to check the quality of online education based on customer requirements. It is planned to implement QFD as tool to identify the exact technical requirements to satisfy the customer and stake holder expectations.

1.3. Research Aim and Objectives

The basic aim of this study is to implement QFD as a way of supporting the move towards utilizing the TQM framework to then improve the way that online learning and related teaching strategies in Oman’s HEIs has been approached. This work seeks to achieve the following objectives:

1. To use QFD as a way of understanding the challenges that students from HEIs in Oman have faced in adopting and understanding coursework through online learning platforms

2. To leverage QFD to collect information from teachers in HEIs in Oman related to their experience of delivering course material through online learning

3. To identify the main gaps in the current approach to online learning among HEIs in Oman; and

4. To provide recommendations to HEIs in Oman geared towards improving online learning based on TQM principles

1.3. Significance of the Study

This study responds to a clear demand not only in Oman, but worldwide in the higher education sector. There is a need to refine the approach to online learning given that it will prove to be a part of the educational experience of university students. In Oman, higher education is vital to the sultanate’s economic growth plans thereby adding another layer of importance in resolving the issues surrounding online learning. As this case study seeks to improve online education quality within Oman, however, it also seeks to expand the current body of research relating to the efficacy of QFD and TQM in supporting higher education initiatives.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Current state of Higher Education in Oman

This section of the literature review focuses mainly on two key points of discussion. The first is an overview of higher education in Oman, with a focus on its role in society and the sultanate's economy, and the second is about attempts at online learning in the country prior to, during and after the pandemic.

2.2. Higher Education in Sultanate of Oman

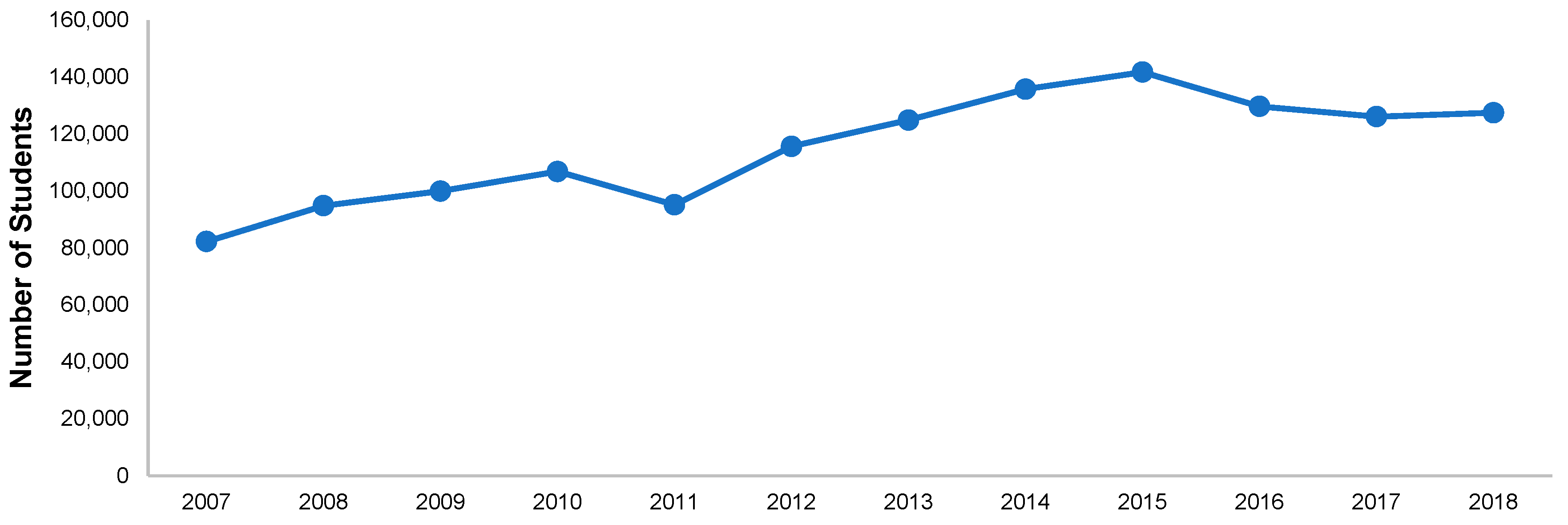

The higher education sector of Oman is constantly evolving to achieve high quality in education. Therefore, it is essential to begin by providing more insight on the current state of higher education in Oman so as to better understand the nature of the improvements that will have to be undertaken based on the evaluation. As per the NCSI-2021, the number of students enrolled and the number of teachers employed in HEIs in Oman from the year 2007 to 2018 are shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, respectively.

The data in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 indicates that the HEI sector of Oman has been expanding in the past years, while the number of students has more or less stabilized in the 120,000 to 130,000 range, there have been more and more teachers employed in various HEIs to support the growth of the sector.

As a part of technology, higher education institutes in Oman have introduced the alternative learning modes focused on e-learning channels. Tawafak et al., (2019) looked into the efficacy of using e-learning in coursework among Omani university students. Based on an evaluation of student and teacher experiences, the authors found that the two modes are more or less comparable although there were more variables that had to be controlled to make e-learning effective. This study shows that the pivot to online learning which lead to positive outcomes but there is a greater complexity involved in determining the proper teaching pedagogy.

Sarrab et al., (2016) evaluated the factors that influenced the adoption of mobile and online learning among students in HEIs in Oman. The authors found that students were more critical about the ease of use of online learning platforms and the ability of educators to engage in this alternative channel.

2.2.1. Value and Challenges of Higher Education in Oman

Compared to many of its neighbors in the Gulf, higher education in Oman is relatively young as it was only in 1970 that the sultanate moved towards a rapid and extensive overhaul of the country’s educational system. This was initiated with the growing recognition of the importance of higher education on the economic viability of Oman (Hakro and Mathew, 2020). This is exemplified in the fact that the continued improvement of standards related to higher education has been a core issue pushed in the Oman council since the 1980’s (Al-Najar, 2016).”

The role of higher education in the Sultanate of Oman has gained even greater focus in the past years given the release of the Oman Vision 2040 (2020) plan, which highlights education and the bolstering of national talents as one of the main priorities. According to the plan, the Sultanate is able to provide quality higher education which will lead to long-term economic gains due to the creation of a mass of Omani citizens who are skilled and capable in supporting various industries and development and innovation activity in the entire country (Oman Vision 2040, 2020). The plan sees higher education as an avenue through which Oman can globalize its industries by up skilling citizens through the refinement and refocusing of curricula.

Growth is not always positive. One of the main challenges in higher education in Oman is the pace of change. The hurdles are highlighted in three issues: funding, access, and quality. Higher education in Oman is strongly dependent on government funding. This is obvious for public institutions but even private HEIs are dependent on various subsidies and support from the government (Al-Sarmi and Al-Hemyari, 2014). However, the issue is that this funding is buoyed by revenues from the country’s oil reserves, and this raises the question of sustainability. The second issue is equity and access to higher education. There are more and younger Omanis that are eligible for higher education and who are actually interested in pursuing this opportunity. There are limited seats in the government institutions for the students who are coming from economically backward families; If they want to join in private institution for their higher studies, then they have to pay more money which will give more burden to their families .(Ismail and Al Shanfari, 2014). The government has realized and responded to this by expanding scholarship grants, but this once again raises the question of funding and sustainability.

2.2.2. Online Learning in Oman Higher Education Institutions

The online learning and the use of alternative learning platforms is not new in Oman. Many efforts have been taken in the past to support the growth of the higher education sector and to leverage wireless technology and digital innovation in expanding the reach of HEIs (Al-Emran and Shaalan, 2017). To achieve this, there has been substantial research done to evaluate the efficacy of these methods. For instance, in the work done by Tawafak et al. (2019), the authors considered a specific style of online learning implemented at a university in Oman and they evaluated the feedback provided by the students. The researchers found that to provide effective online learning, good administrators, clear coursework instruction, an effective way of assessment, recruit faculty with experience on the medium.

Another study done by Gawande (2015) evaluated the use of blended learning wherein students are exposed to both online channels and in-person instruction. In the research, Gawande (2015) found that a key factor in supporting online learning is to work to develop student friendly environment. This means students must first understand the value of online learning as a method and they should see it as a viable way of understanding their course material. According to the author, this can be challenging as students are accustomed to the classroom setting as the sole academic venue. With regard to achieving greater buy-in, Al-Emran et al., (2016) sought to investigate the attitudes of university students in Oman towards mobile and online learning. In their analysis, Al-Emran et al. (2016) identified that younger students are typically more open to these alternative learning mechanisms because of their affinity for using digital solutions. The authors added that the quality of connectivity is a strong antecedent to openness to online learning.

Slimi (2020) has undertaken a case study on the situation in HEIs in Oman. According to Slimi (2020), learners and teachers have been able to adjust to the online setting, but the author raises issues in the overall experience of the relevant parties and added that students who have had a negative online learning experience has mainly been hampered by internet connectivity problems and the technological infrastructure that they have access to. This raises a clear issue of equitable access to quality education in the current situation. In addition to this, Slimi (2020) also mentions the inability of some instructors to translate their methods into the online setting given that there was little time to adjust to the set-up. All these is to say that there is still work that is needed to improve the quality of online learning in Oman.

2.3. Total Quality Management: An Overview

Having provided a greater description of the state of higher education and online learning in Oman, the second part of this literature review focuses on the concept of TQM. In this study, the fundamental framework that guides the analysis of the issues of online learning and its principles are presented. As such it is necessary to cover the concept of TQM to better comprehend why it was developed and what problems it addresses. Furthermore, a discussion of TQM's application in education is included to illustrate the sector's ability to enhance results.

2.3.1. Development and Concept of TQM

There are numerous conceptualizations that seek to describe the nature of TQM, but its name represents overall quality management in all area of the product (or) processes. It is a quality management framework that seeks to capitalize on leveraging all aspects of the organization to holistically and comprehensively meet standards of quality that are aligned with the needs and expectations of a firm’s customers (Abbas, 2020). According to O’Neill et al., (2016), the authors looked into the various ways that TQM is utilized by different organizations and they evaluated the impact of these approaches on the financial performance of the company. Looking into data gathered from manufacturing firms in Australia, O’Neill, Sohal, and Teng (2016) found that the selection of the TQM approach is a function of compatibility with the operational paradigm and culture of the organization. This shows that TQM is broad and diverse, it is nonetheless effective when properly applied. Supporting this, Pambreni et al., (2019) considered the case of small and medium enterprises in Malaysia and they found that the use of TQM, helps firms improve overall performance because of its focus on customer satisfaction.

TQM is an important tool for of cultural and organizational change in order to achieve success. In the midst of the encompassing nature of TQM and the management commitment to enforcing it, this will inevitably lead to long-term and potentially dramatic changes within the organization that must be likewise supported by holistic cultural change. The solutions that are proposed through TQM can make a lasting and sustainable impact within the company.

2.3.2. Total Quality Management and Education

As a second point in this contextualization of the work, the question remains as to whether TQM and QFD can be applied in higher education so as to support the intent of this study. Shams (2017) showed that TQM is an effective paradigm to apply in the improvement of higher education outcomes and the author especially emphasized its applicability to numerous national and cultural settings. Moreover, Al-Qayoudhi et al., (2017) more directly looked into TQM’s use in Oman by undertaking a case study on a university and the authors confirmed the conclusions made by Shams (2017). With regard to QFD, Sagnak et al.,(2017) found it effectiveness in improving quality in business schools while Al-Bashir (2016) determined the tool to be useful in supporting the efforts of various universities in the gulf area to bolster the educational experience. These studies ultimately point to the fact that QFD and TQM indeed have a place in the education sector and both can be leveraged to aid HEIs in the continued transition and improvement of online learning implementation.

2.3.3. Application of the TQM Framework in Higher Education

Nasim et al., (2020). emphasized that several studies have repeatedly shown that TQM can be used to evaluate and adjust teaching styles to better suit student needs, to understand the various aspects of experience of the student to adjust curriculum and pedagogy, and to ensure that the coursework and course material provided to students are up to par with national and international standards. Drawing from the conclusion of Nasim et al. (2020), it is quite apparent that TQM does finds its application in higher education and that it is, in fact, effective. Building upon this, an important question is how it is able to affect this positive change on HEIs.

In considering the experiences of HEI staff members in Iran, Aminbeidokhti et al., (2016) found that TQM helped to support organizational learning, which is the process by which an organization is able to be introspective and use its experiences in order to support sustained and continuous improvement. The authors noted that the application of the principles of TQM made HEI faculty and staff more conscious about issues in teaching styles and course material and this motivated organizational innovation towards the improvement of overall quality. In another study, Psomas and Antony (2017) surveyed the implementation of TQM in 15 private HEIs operating in Greece. The intention of the authors was to determine which aspects of TQM are being used in these organizations along with the main focus areas that they sought to improve. The findings of Psomas and Antony (2017) show that HEIs were most focused on using to TQM to bolster overall quality metrics, enhance operations, and ensure satisfaction both in terms of the faculty and staff and the students.

Nadim and Al-Hinai (2016) set out to identify the critical success factors of TQM in the higher education context. The study is especially relevant as data was collected from an HEI in Oman. According to the authors, successful TQM was predicated on two factors: employee involvement and stakeholder focus. This shows that the idea of buy-in among employees is needed in order for TQM to work, indicating that faculty and staff should be fully committed to utilizing the various appurtenances of the framework upon implementation. Nadim and Al-Hinai (2016) moreover noted the importance of stakeholder focus, meaning that the experience of the students is paramount in using TQM in HEIs. In the next part of this literature review, the notion of listening to the voice of the stakeholders, the students, are tackled through the discussion on QFD.

2.4. Quality Function Deployment and Total Quality Management

The main quality management paradigm that is going to be explored is TQM. This framework places an emphasis on the importance of leveraging customer satisfaction and customer voice in order to guide the continuous improvement and processes and operations within an organization (Androniceanu, 2017). QFD is a way by which companies are able to listen to the voice and opinions of their customers in order to move towards addressing the core needs of the group (Kiran, 2016). Given that TQM is highly customer-driven and is geared towards ensuring satisfaction, QFD provides a means through which customer needs can be better identified and consequently understood the most effective actions can be carried out by the company (Erdil N.O. and Arani, 2019). A deeper consideration and exploration of QFD as a tool in terms of how it relates to quality management.

2.4.1. Implementation and the Idea of Customer Voice

QFD is a tool that is deployed when undertaking TQM and it allows organizations to understand customer requirements for a given product or service and to, thus, effectively organize engineering specifications that are able to meet these requirements (Lam and Bai, 2016). Therefore, QFD responds to the customer-centric nature of the TQM framework by creating a concrete path for the organization to engage with the customer and to explicate their needs in terms of actionable decisions in connection to what they want to offer (Puglieri et al., 2020). As mentioned, QFD is usually used at the onset of product development to guide the design process. Using a case study focused on a ceramic tile-making company, Erdil N.O. and Arani (2019) developed a framework that utilized QFD not just as a way of defining design specifications but as a quality improvement tool that is focused on identifying corrective actions and technical limitations to current products. In taking this approach, Erdil N.O. and Arani (2019) found that the company improved customer satisfaction and service quality, as an evident in a reduction in complaints. This shows that QFD can be used to support quality improvement and not just to chart product definition.

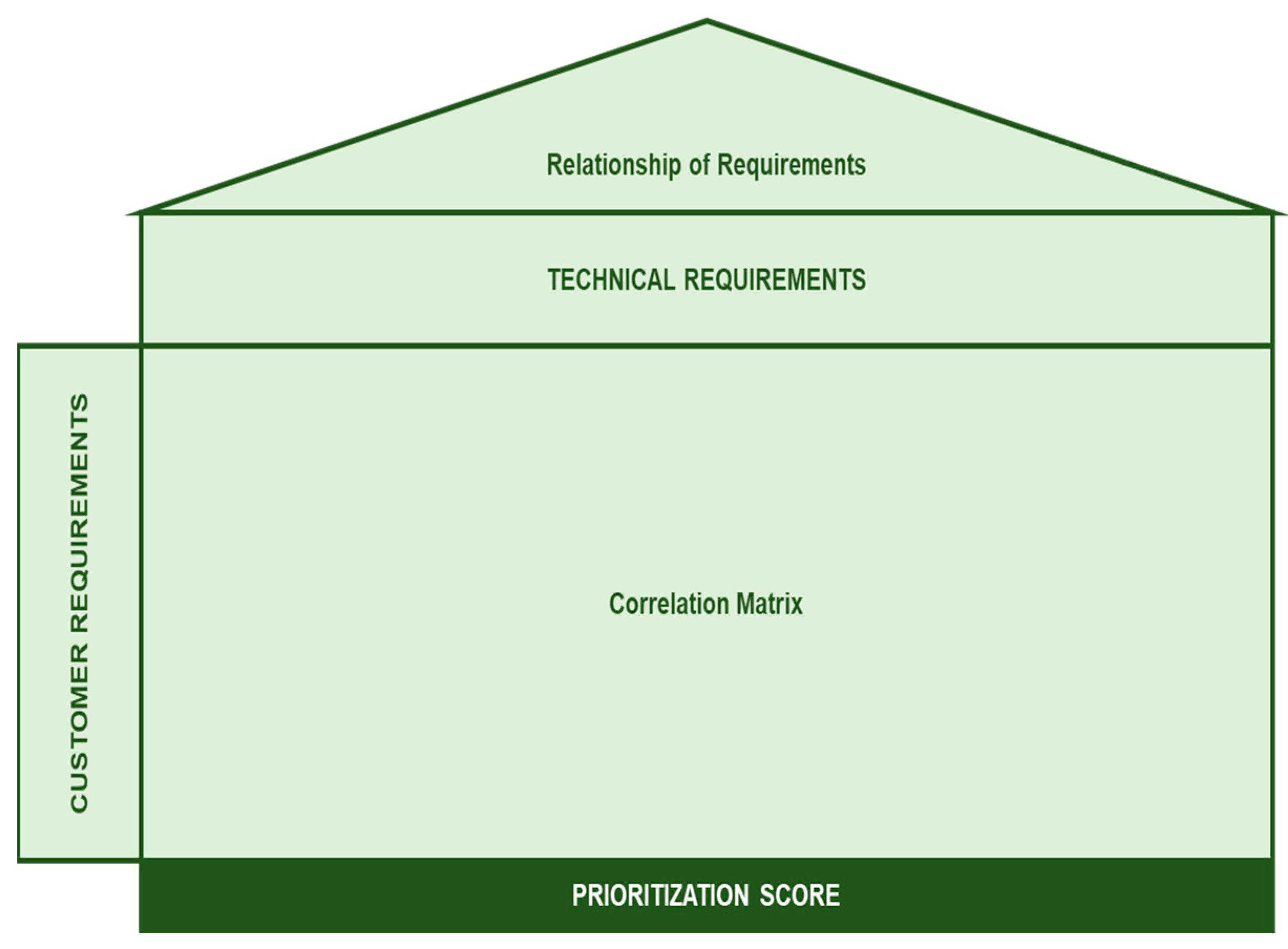

Voice of customer is a core and central theme of QFD. The voice of the customer, as the name implies, refers to all their needs and requirements, both explicitly and implicitly stated (Gangurde and Patil, 2018). Therefore, QFD is a way for companies to explicate the voice of the customer and to concretize them so that the company can move towards ensuring that this voice is heard and is considered. According to the study carried out by Iqbal and Girgg (2020), if QFD is properly implemented, it is able to provide the emphasis on the voice of the customer such that it leads to prioritization on the part of the company. One of the primary tools by which QFD is applied is through the creation of a house of quality. This is the fundamental design tool employed in QFD that visualizes the customer requirements and their level of importance against the product features to determine the strength of association across these aspects of the product or service. This case study will employ the house of quality approach in the analysis of online learning and a fuller description in this research work.

Amuthakkannan,R et al., (2018) proposed a new methodology in relate to blending of the Voice of customer with a novel concept of Red Green Chart (RGC) to build the House of Quality to improve the effectiveness of the selection of the components for design changes. In this research work, Quality Function Deployment (QFD) concept is applied to predict the appropriate technical requirements in each stage of product development and production in the area of mechatronics system design.

2.4.2. Use of Quality Function Deployment (QFD) in Higher Education

There are several studies that highlight the use of QFD in higher education. In the research of Sagnak et al. (2017), the authors deployed QFD as a way of helping business schools to improve their overall quality. The contention of the researchers is that QFD is an effective tool to find the need of business schools to become more competitive as it gives them a concrete and definitive way of determining whether current coursework and aspects of teaching are aligned with the needs of the students and are to a standard that is comparable to their competitors. This once again emphasize how QFD is supportive of quality improvement in case of the higher education sector.In another study, Cetinkaya et al., (2019) carried out an analysis in which QFD was implemented to investigate the quality of the industrial engineering curriculum adopted in a particular HEI in Turkey. In doing so, Cetinkaya et al., (2019) were able to note the aspects of the curriculum that did not meet the needs of the students and the quality of their learning experience is not upto the mark. In implementing modifications based on these results, the authors mentioned improvements in the quality evaluations provided by both teachers and students with regard to the curriculum. Lastly, Matorera and Fraser (2016) took a broader view of the topic, responding to the larger question of whether QFD can truly serve as a way to evaluate and assess the quality of instruction in higher education settings or not. From data that was collected in business schools in South Africa, the authors concluded that QFD indeed has a place in higher education and it is an effective tool for pursuing quality improvement.

3. Methodological Framework

3.3. Research Strategies

A research strategy provides a glimpse of the research design. To facilitate the quantitative approach that is adopted in this research, a survey questionnaire is utilized. This gives the respondents a convenient way of responding to the queries of the researcher in a succinct and compact manner. At the same time, this also aids the researcher as questionnaires are easier and logistically to distribute and collect as well as more expedient when it comes to analysis (Patten, 2016).

3.4. Sample of the Study and Recruitment

The research seeks from respondents to provide recommendations for online learning among HEIs. As such, the teachers and students that are to be a part of the sample should come from Omani HEIs. To focus the data collection and to reduce logistical issues, the researcher decided to collect data from the College of Engineering. This introduces some bias into this study as it is specifically a private institution and the students are from an engineering-related course, but it is hoped that the sample will nonetheless give insight into the larger situation of online learning in the country. As mentioned, both teachers and students are going to be recruited in the sample collection. The question, then, is the number of respondents for each.

To determine this, Slovin’s Formula was utilized.

This is an equation that computes the suggested sample size n from a population N given the statistical significance e that is selected for the study (Adam, 2020).

From information published by the University in 2021, the College of Engineering is said to have an estimated 3,000 students. Moreover, based on data from the Oman NCSI (2021), the typical student-to-teacher ratio in HEIs is one to eleven. This means that around 275 teachers are in the college. From these numbers, and through the use of Slovin’s Formula, a sample size of 355 for the students and 165 for the teachers was used in this study.

With regard to the selection process of participants, convenience sampling was implemented. This means that the researcher simply spreads the invitation to participate across all viable channels. Invitations were thus posted in electronic student and university boards and those who saw this were encouraged to spread it around as well. From this broad recruitment strategy, a total of 422 students and 187 teachers responded with their intent to participate. From this initial pool, 355 students and 165 teachers were randomly selected to be part of the final sample. Any respondent who withdrawn their intention to participate after this final selection was replaced by once again randomly selecting from the larger group. Note that all respondents were duly briefed and asked for their consent to participate before any data collection was carried out to adhere to ethical practice.

3.5. Data collection and Research Instrument

As was indicated, a questionnaire is the primary data collection instrument that is utilized in this study. As there are two groups, there were two sets of questionnaires created, one for the teachers and one for the students. Both questionnaires have two sections. The first section of the questionnaires is geared towards collecting information on the respondents. On the part of the teachers, the first section covered:

- ❖

Their gender, age group, current teaching position, the online platform they use, and the number of years of experience they have had with online instruction.

On the other hand, the first part of the questionnaire for the students collects data of

- ❖

Their gender, age group, the department that they are a part of in the College of Engineering, the online learning platforms that they have used, and the time that they have spent attending online classes.

In addition, the second part of the questionnaires was the same for both groups as this is the part where their voice as a customer is evaluated. There are 12 items in this part that revolve around aspects of online learning. For each of the items, the respondents were asked to rate them on a scale of one to five with one being strongly not important and five indicating strongly important. These 12 items fall within four product attributes: technical, financial, operational, and functional. These were determined to be the key categories that any product or service should consider, and this also includes online learning.

In terms of the data collection, given the current restrictions and to uphold proper health standards, everything was conducted online. In particular, the participants were provided a link to a Google form where they were asked to provide the information that was asked of them. They were given three weeks from the time that the survey link was sent to finish the questionnaire. Three reminders were given when needed: one week, two weeks, and one day before the indicated deadline. This was to ensure that all questionnaires were reverted in a timely manner.

3.6. Approach of Data Analysis

There are three parts in the data analysis from the data which is collected from staff & students. The first part involves the computation of the descriptive statistics and frequencies of the various data collected in the initial part of the questionnaire for both groups. The intent here is to provide a characterization of the sample of the study. Following this, two more levels of analysis were carried out which are understanding of customer voice and building house of quality using QFD concepts.

3.7. Analysis the Voice of Customer

The second aspect of analysis was done by asking the understanding of the voice of the customer. To do this, the mean score of each of the 12 items in the questionnaire was computed, both for the students and for the teachers. The understanding is that the students are central to the online learning process. As such, a final inclusion score for the items was computed by weighting the student score by 70% and the teacher score by 30%. From this, the six most pertinent items were deemed to be the critical technical requirements that an effective online learning scheme must be able to capture. This represents a preliminary step that is required in the development of the house of quality diagram used in QFD. In addition to looking at the scores to finalize the technical requirements, inferential statistical analysis was also conducted to determine trends and differences in the responses of the teachers and students.

5. Creating the House of Quality

The third part is the core analysis that was centered on the creation of a house of quality for online learning representing the needs of both the teachers and the students. As was noted in the literature review, this is a diagrammatic tool that is implemented as part of QFD and the goal here is to determine the main areas of improvement that should be prioritized in order to meet the needs of the customer (Jamali et al., 2010). The house of quality can be analyzed in the diagram as shown in

Figure 4.

There are four parts to the house of quality that needs to be considered. The two major ones are the customer requirements and the technical requirements. The other two parts are to determine relationship requirements and preparation of correlation matrix. In this study, the customer requirements are what the online learning process is intended to ultimately result into. To identify these, the graduate outcomes of the institution were consulted. As such, there were seven customer requirements that were identified:

Create an environment of effective learning and instruction for students and teachers;

Ensure that students are able to attain knowledge and gain competence;

Develop the innate curiosity of the students and make them life-long learners;

Inculcate the importance of ethical practice to the students;

Make the students confident in their skills and capable of adapting to situations;

Emphasize the importance of entrepreneurship and responsive citizenship; and

Provide an education that is cost-effective.

These seven items are then given an importance score that ranges from one to five, with five indicating the highest level of importance. The technical requirements, on the other hand, are added based on the voice of the customer. These are the specifications of online learning that were considered to be most important by the relevant stakeholders.

With these two main parts of the house of quality established, the rest of it can be constructed. The correlation matrix is an evaluation of how each of the customer requirements relate with the technical requirements. The rule of thumb for this is to score high correlations with nine, mid correlations with five, low correlations with one, and aspects with no correlation are given a score of zero. To fill up the matrix, the correlation score is multiplied with the importance score of each item. The scores across each column are then added to determine the prioritizations core of the various technical requirements. This is especially critical for the study because this determines the main aspects of improvement for online learning and was used as the rationale for crafting the recommendations of the study.

The roof or apex of the house of quality represents the relationship of each of the requirements. This can range from a strong positive to a strong negative correlation. In this study, this was determined by carrying out bivariate analysis on the scores of each of the items based on the data from the students and the teachers.

4. Characteristics of the Study's Sample

The characteristics of the two sample groups under consideration are presented in this section. The first part of the questionnaires given to these respondents, as previously stated, collected participant information such as gender, age and work or study-related information. This was done to give the researcher a better understanding of the different characteristics that the participant groups exhibited, allowing for a more in-depth discussion of the study's findings. In this part, we'll look at both sample groups. The first section will focus on the details of the teachers, while the second section will concentrate on the details of the students, as seen below.

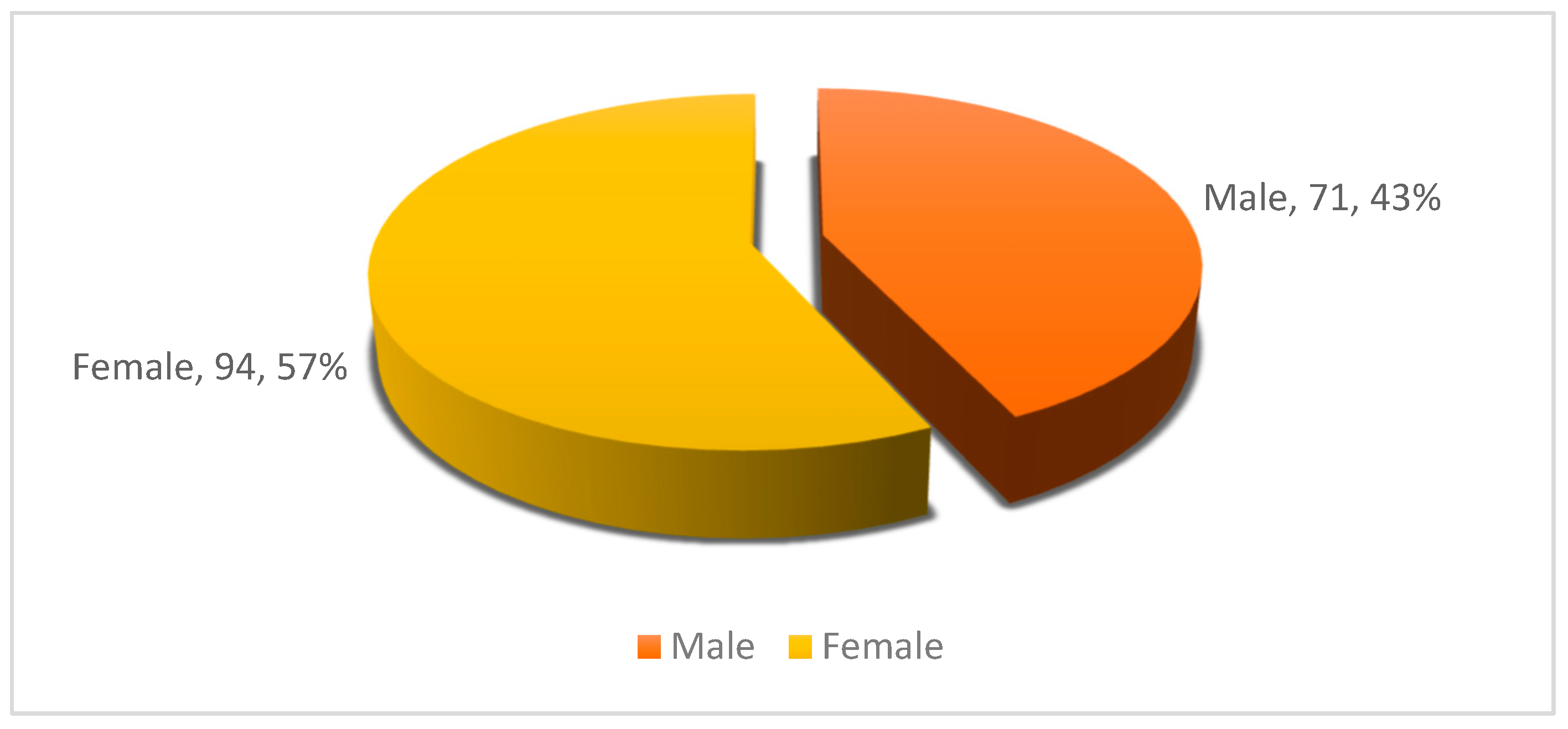

4.1. Teachers in the Sample of the Study

To begin, the study takes into account the key characteristics of the teachers. Based on the sample size determination, it was determined that 165 teacher respondents would be appropriate to produce a statistically significant sample size at the 0.05 level of significance. The gender distribution was the first aspect of the data that was highlighted for this category, as shown in

Figure 5.

As shown in the above figure 5, the data indicates that majority of the teachers surveyed in this study were female as they composed 57% (N = 94) of all respondents whereas only 43% (N = 71) were male. In addition to asking about their gender, the questionnaire also inquired upon their age and the data for this is shown in

Figure 6.

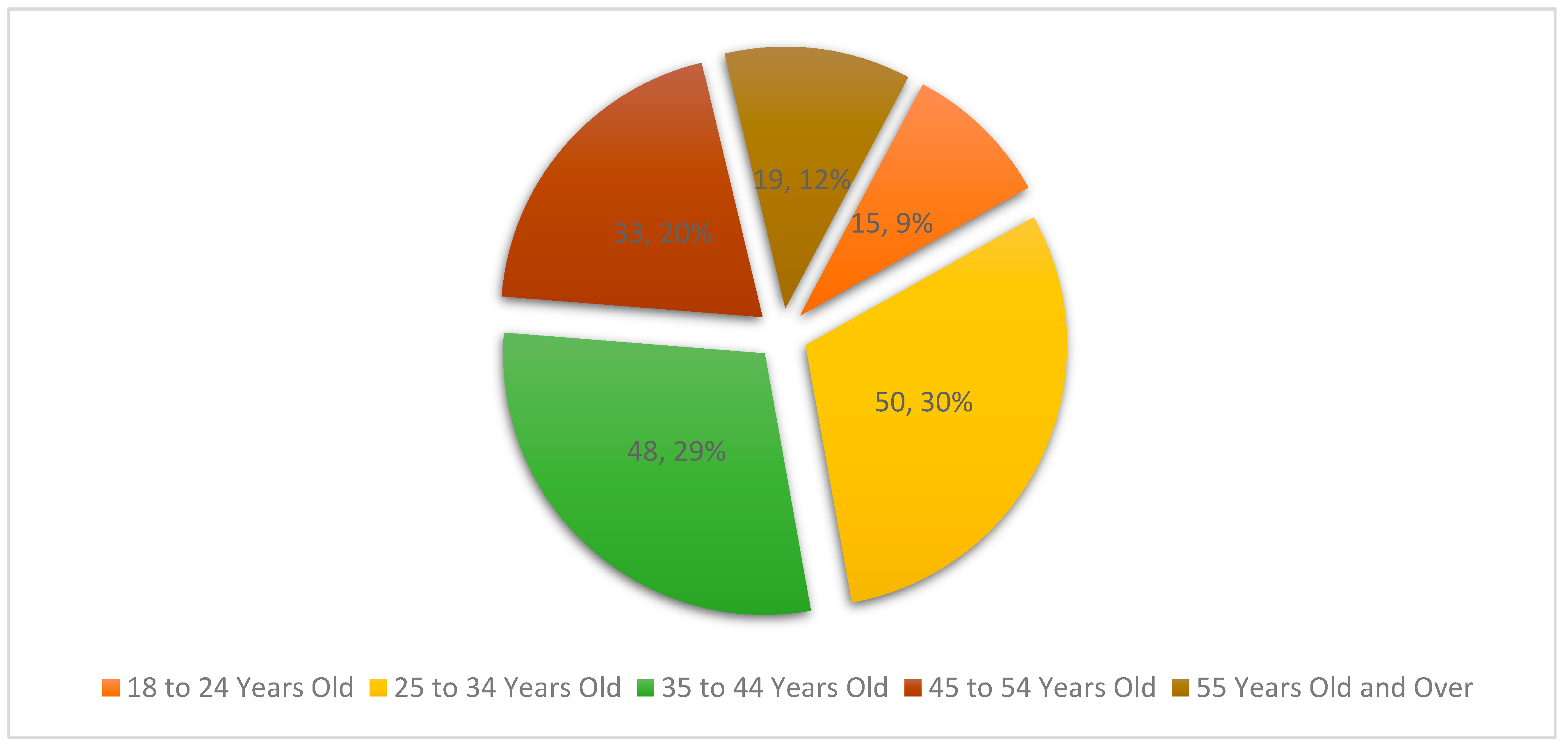

The data that is visualized in

Figure 6 indicates that most of the teachers in this study fall within the 25 to 34 and 35 to 44 age groups as these had 30.30% (N = 50) and 29.09% (N = 48) of all the sample group. The lowest representation came from either end of the age spectrum as those in the 18 to 24 years old group were only 9.09% (N = 15) of the respondents and those who were 55 years old and older composed only 11.52% (N = 19) of all teachers. Moving on from this personal information, data was also collected about their work and experience. First among these was on their current designation, shown in

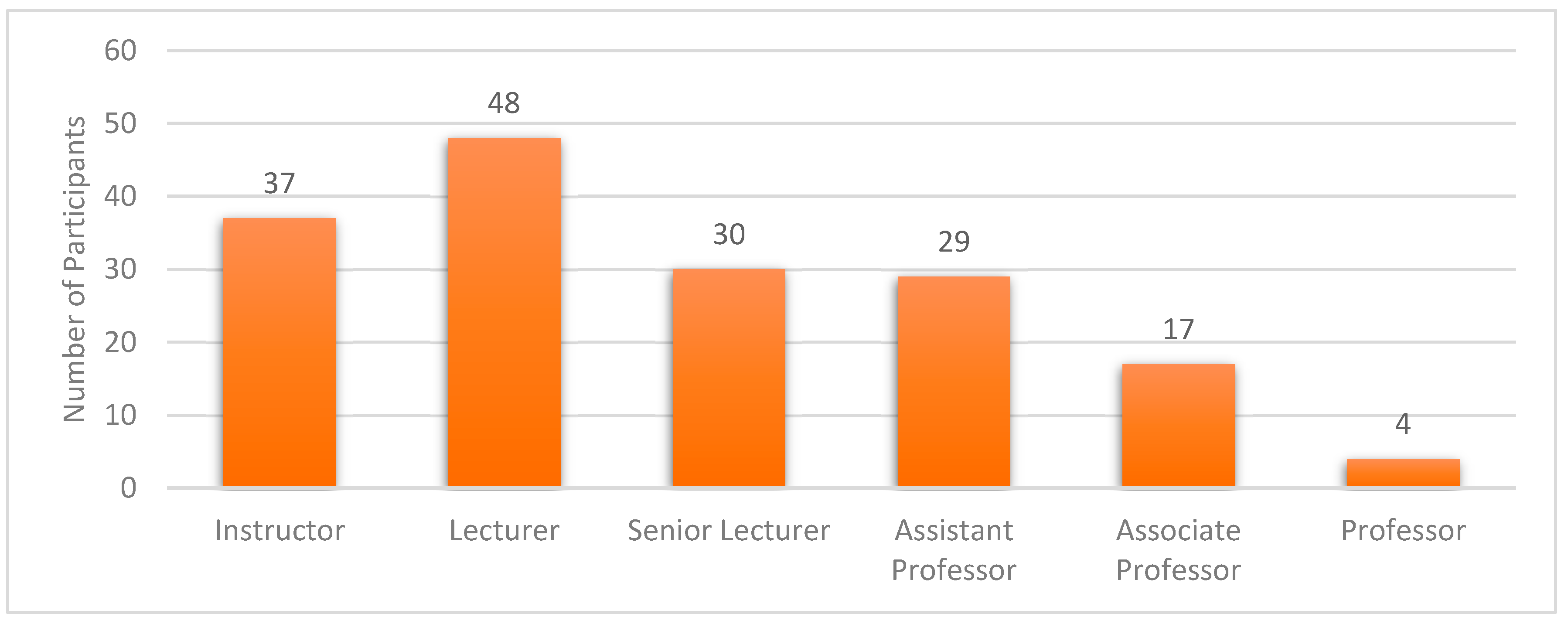

Figure 7.

Those who responded to the invite tended to be teachers who fell within the lower designation ranks. This is apparent as instructors were 22.42% (N = 37) of participants and lecturers 29.09% (N = 48). On the other hand, only 2.42% (N = 4) of those who joined the study had the designation of professor. Apart from information on their role, the department they belong to in the college was also asked. This is shown in

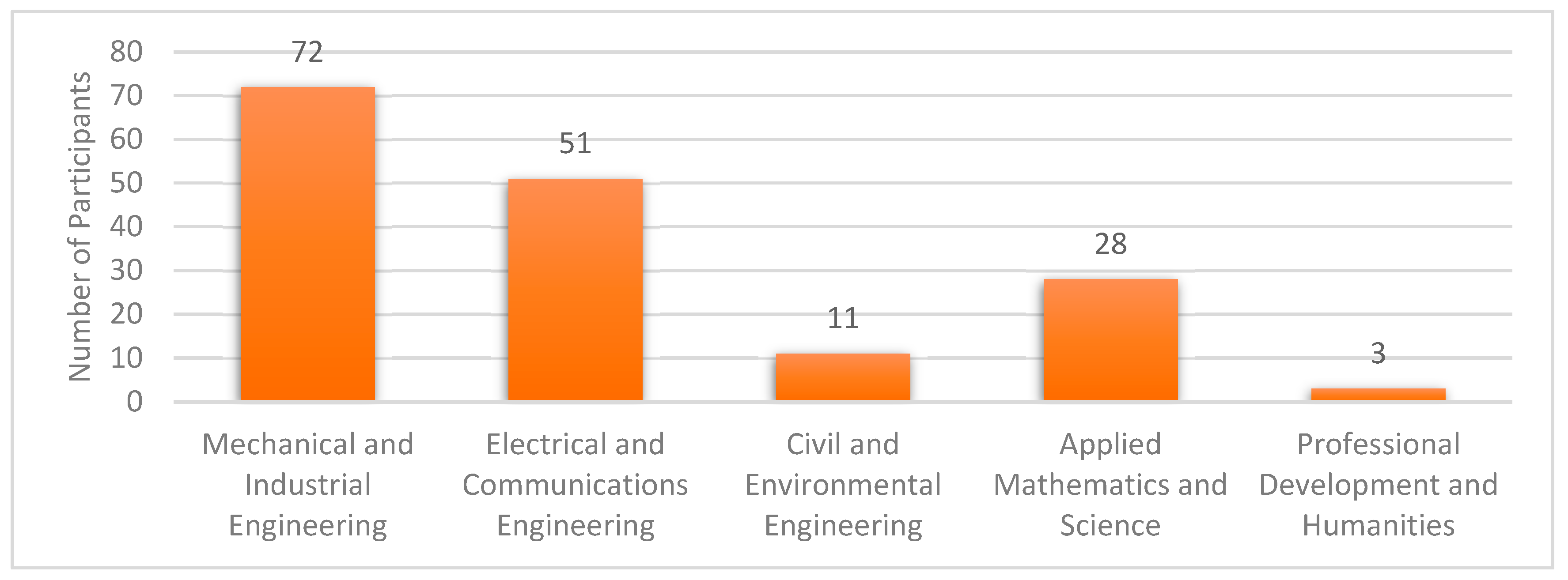

Figure 8.

Almost half of the participants actually came from Mechanical and Industrial Engineering Department as they were 43.64% (N = 72) and this is closely followed by those from the Electrical and Communications Engineering Department at 30.91% (N = 51). The smallest representation came from the Professional Development and Humanities Department as only 1.82% (N = 3) joined the research. Focusing now on aspects of online learning, the participants were asked about the number of months of experience they have had with this medium of instruction. Their responses are illustrated in

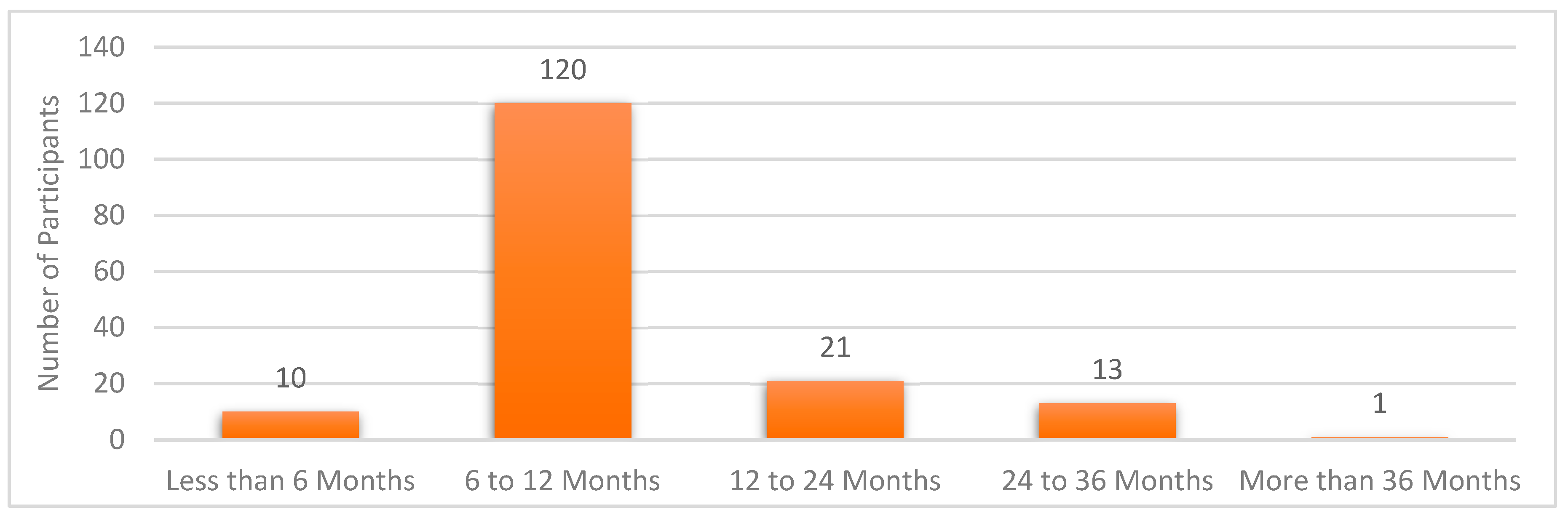

Figure 9.

Figure 9 is very clearly shows that most of the participants have had time with online learning for only six to 12 months. This represents 72.73% (N = 120) of all the teachers in this study. This result is unsurprising given that this covers the period of transition to this new platform of instruction resulting from the safety issues that may arise from in-person classes. In addition to this, what this result shows is that most of the participants were thrust into online classes with very little time to actually learn how to manage the setting. It makes sense, therefore, that even teachers were struggling to cope with the complexities of connecting with students remotely and trying to communicate difficult subject matter in a manner that is less than optimal or, at the very least, is foreign to both the students and the teachers. This further highlights the need for a more concerted effort to improve the online learning experience, which, as this study argues, can be facilitated by TQM through the implementation of QFD.

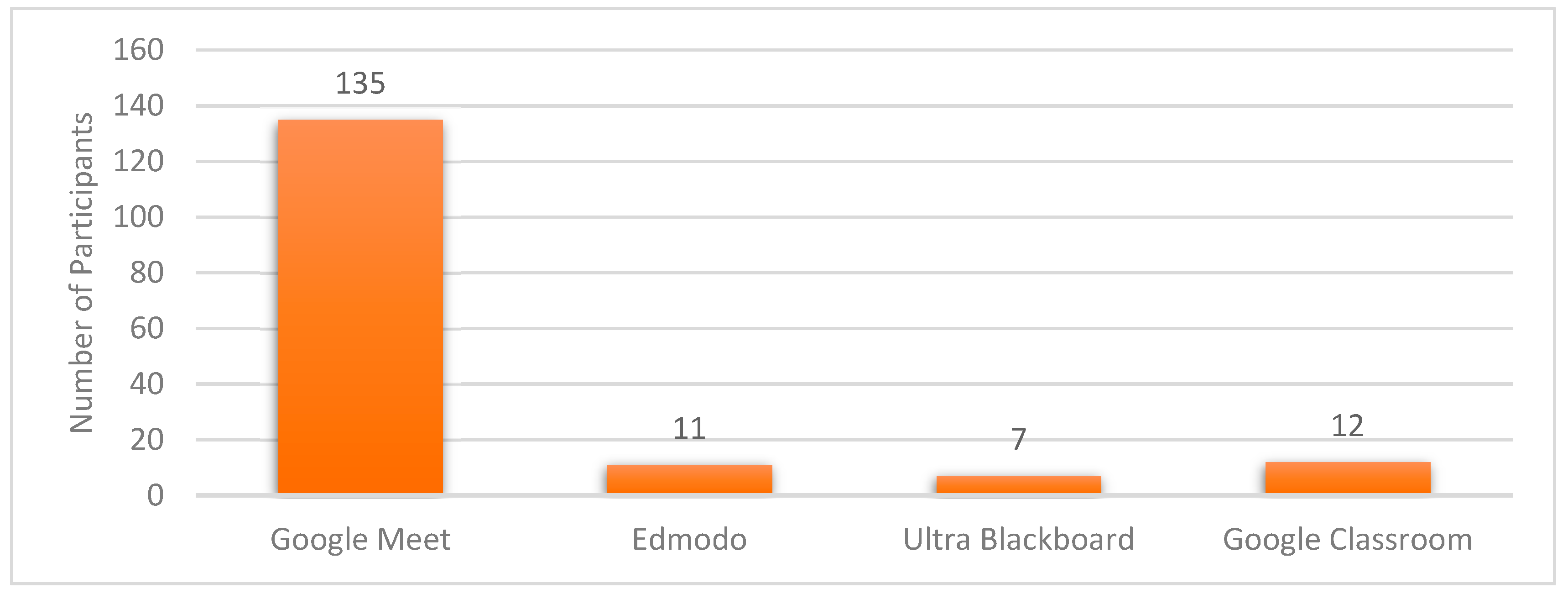

The last piece of information asked from the teachers concerning their online classes was on the platform that they most frequently utilized. Note that this does not mean that this is the only one they used. Rather, among the choices, it was their response indicates the one they have preferred through their time in the online setting. Results are shown in

Figure 10.

The data in

Figure 10 makes it apparent that the teachers generally tend towards the use of Google Meet for their online classes as this was 81.82% (N = 135) of all responses. The rest of the participants were more or less split across the three other platform options in the questionnaire.

4.2. Students in the Sample of the Study

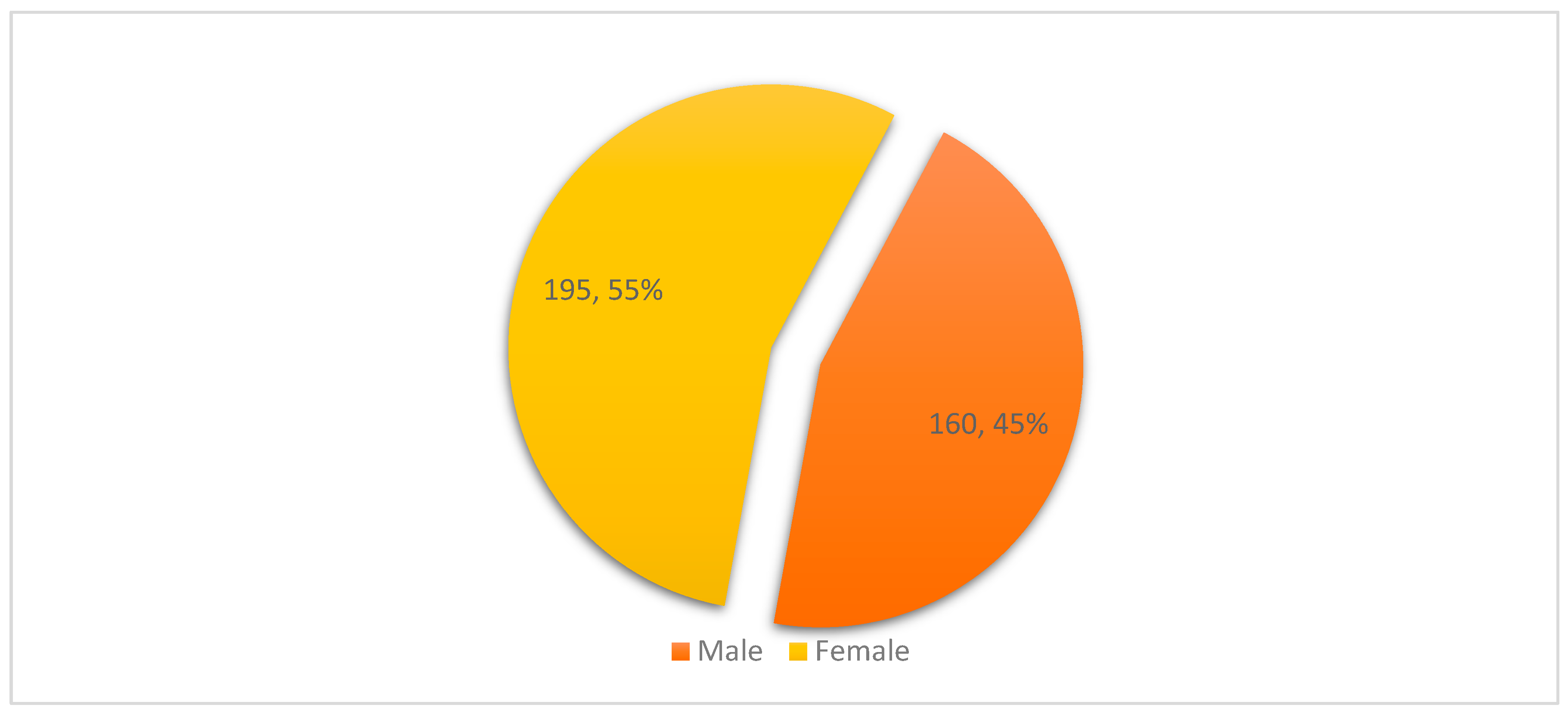

The second group of respondents in this study were the students of which 355 were included in the final group to ascertain statistical relevance. The same information was mainly asked of these participants as well, starting with gender. The results are shown in

Figure 11.

Just as in the case of the teachers, most of the respondents are also female for the students as they were 54.93% (N = 195) of the sample while the males were 45.07% (N = 160). However, in terms of the gap in the gender representation, the case for the students is far more balanced when compared to the teachers. In addition to this, the students were also asked about their age and this data is illustrated in

Figure 12.

Now, compared to the teachers that had representation across all the age groups covered in the questionnaire, the student’s only fell within two. This is not surprising as these cover the gamut of all student designations, from undergraduates to those who are currently pursuing further studies. Among these two groups, most students were in the 18 to 24 years old range at 77.75% (N = 276) while the rest of the 22.25% (N = 79) had ages that were between 25 to 34 years old. Moving away from the personal information, questions about their education were also posed. The first was with regard to their department in the College of Engineering. The distribution is shown in

Figure 13.

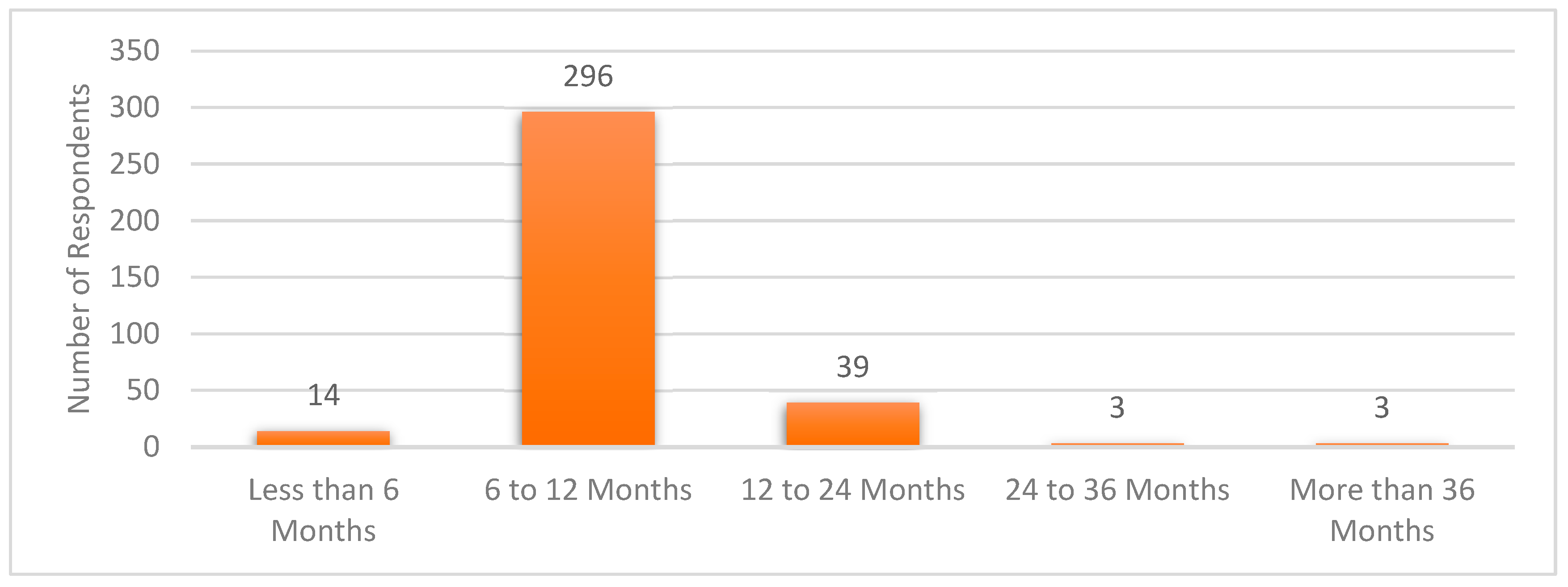

Interestingly, the split across the various departments is quite similar to that of the teachers. That is, just as in the other group, most of the participants were from the Mechanical and Industrial Engineering department, representing 45.92% (N = 165) of the sample followed by the Civil and Environmental Engineering group at 21.13% (N = 75). The smallest representation, on the other hand, was for the Professional Development and Humanities department that only covered 6.76% (N = 24) of the participants, and this was also the case for the teacher group. The next two questions then revolved around information on the online learning experience of the respondents. They were first asked about the number of months that they have spent with this set-up, considering both experiences before, during and after the pandemic. Their responses are shown in

Figure 14.

The results are staggeringly skewed towards 6 to 12 months horizon, which would be equivalent to the time when in-person classes were suspended because of various issues like abnormal weather conditions, less attendance due to traffic issues etc. Of all the students, 83.38% (N = 296) responded with this. What this shows is, just as in the case of the teachers, the students were thrust in an educational set-up that is foreign to them. They had to adjust as they went along, and this would mean that the quality of their education was inevitably affected. As experience with online learning expands for both groups, however, and as a chance for a retrospective such as this study opens up, there is an opportunity to improve the overall learning approach through the use of necessary tools and frameworks. The final question that was asked to the students in this part of the questionnaire was their most frequently used platform for their online classes. Results are shown in

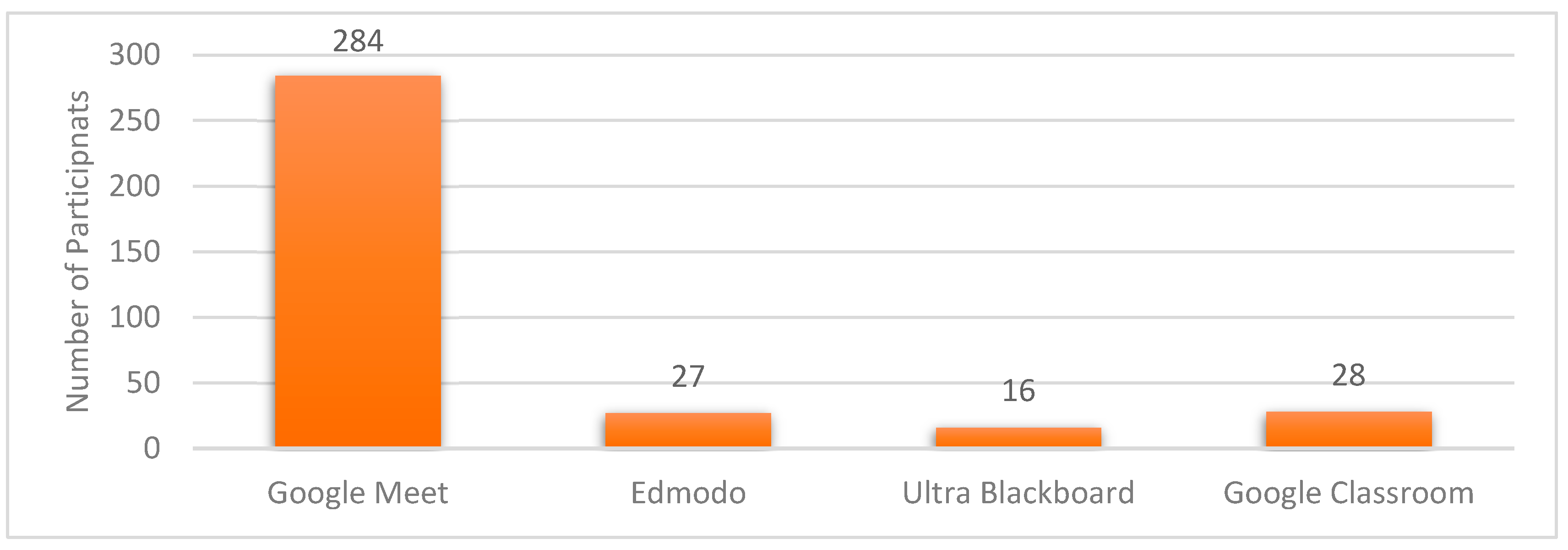

Figure 15.

It comes as no surprise that the responses to this question parallel that of the teachers as the platforms used by the other group would be similar to the ones in this group given that they are in the same university.

Figure 15, thus, shows that most of the students have been using Google Meet, with 80% (N = 284) of all participants choosing this. The rest are closely distributed among the other choices.

4.3. Understanding the Voice of the Customer

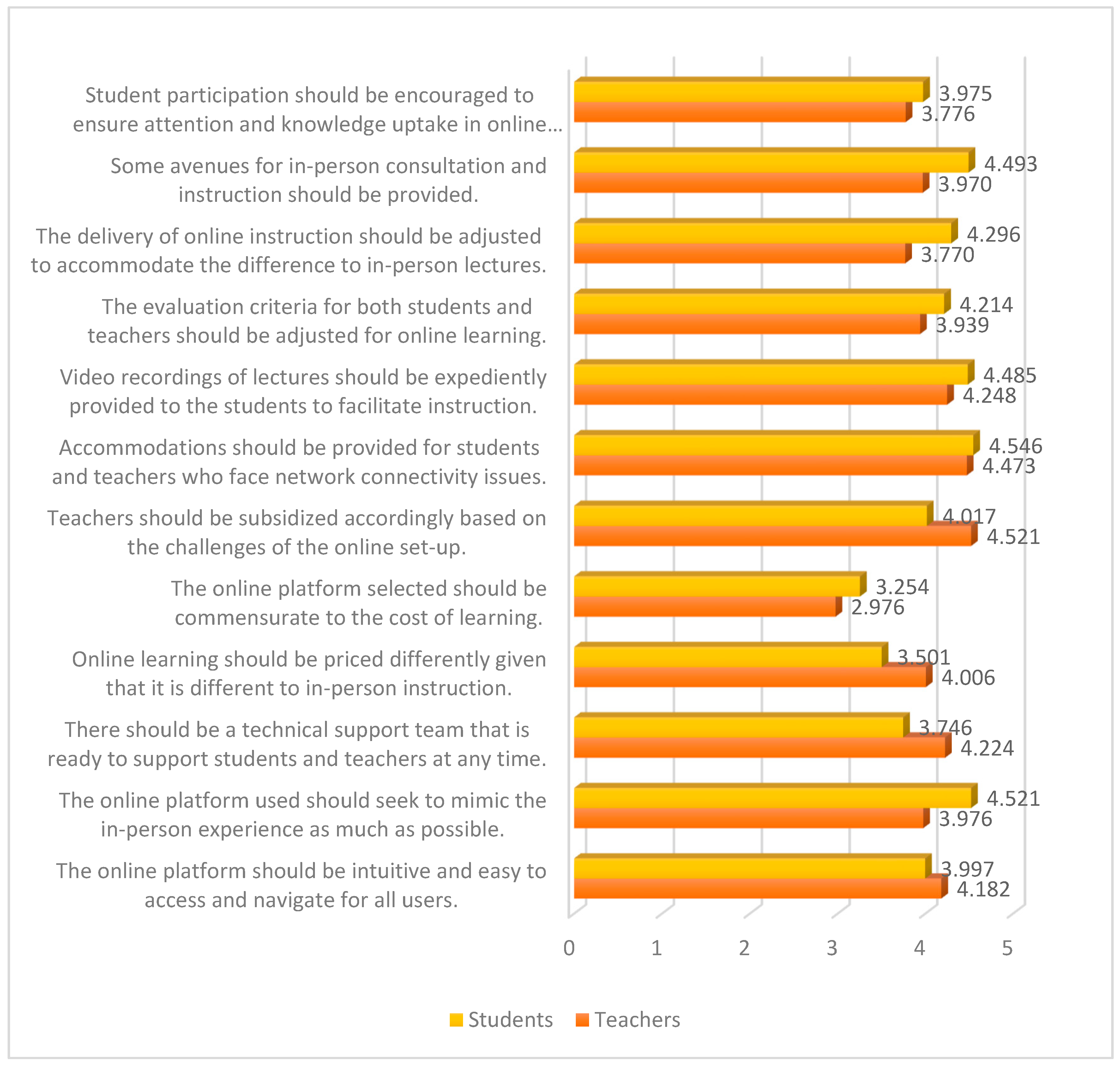

The core of this analysis involves the determination of the voice of the customer as all the recommendations that are to be presented depend on how the two groups view online learning. To understand better and identify the nuances in the voice of the customer, there are three main levels of analysis that was carried out in this research. The first is to show the main trends in the way that both the teachers and the students responded to the various items of the questionnaire. The second is to then evaluate if there are discernible and statistically significant differences in the responses of the two groups. The third level of analysis would be to highlight the priority technical areas of online learning by aggregating the results of the two groups using the weighted scoring process that was discussed in the previous chapter. That is, 70% of the final priority score is dependent on student responses while the other 30% is from the teachers. As mentioned, the first part of this analysis to show the main trends in the data. To this end,

Figure 16 shows the average score of each of the items for both the students and the teachers.

From the results, it is apparent that there are indeed clear differences of opinion from the two groups. From this, there are several items that the students scored higher and some items that garnered a stronger response from the teachers. This shows that the two groups are not monolithic. They have differences in priorities that are based on their perspectives in online learning. With the overall results now presented, the second level of analysis involves researching deeper into the disparity in the opinions of the two groups. The gap in the scores of teachers against that of the students is visualized in

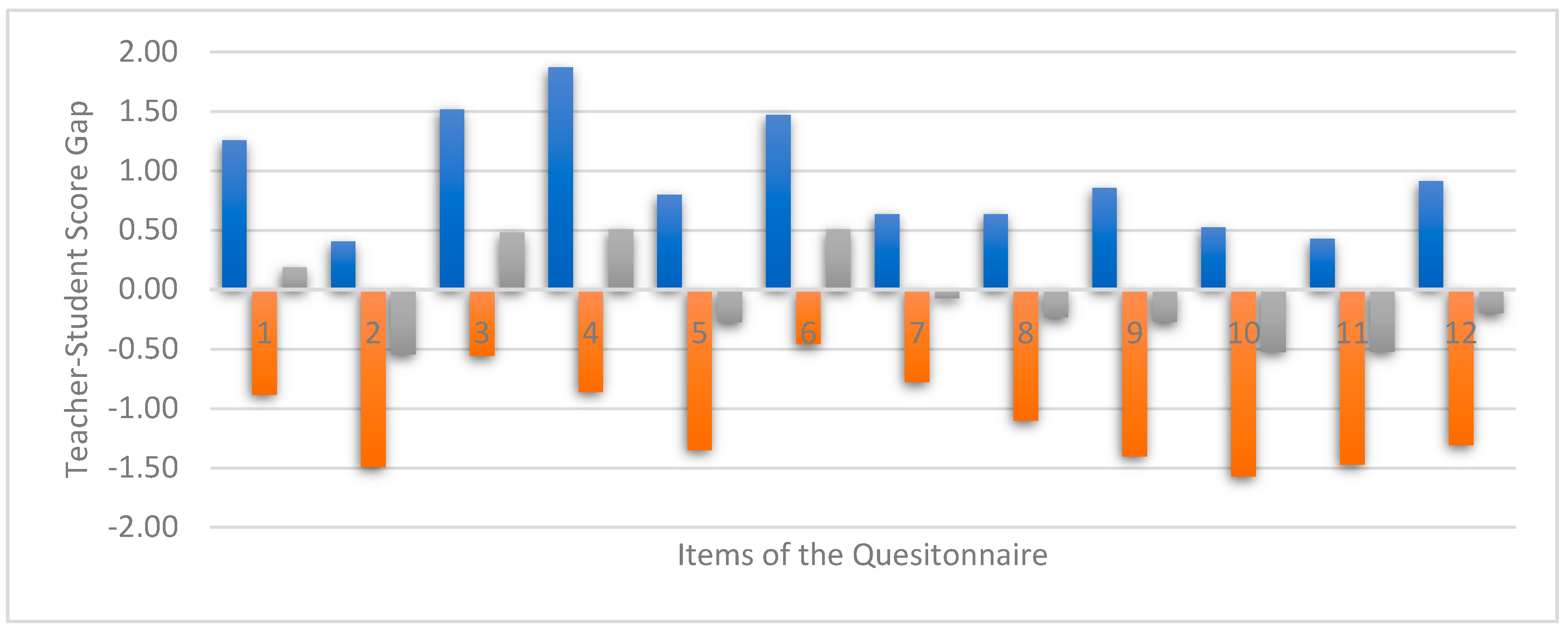

Figure 17.

Figure 17 provides a clearer view of the differences of the scores. Positive values indicate that the teachers scored the items higher while negative values mean that the converse is true. From these results, the two items that teachers scored much higher than students were regarding the need of having a technical team that is constantly on stand-by to support teachers and students if any issues arise and the relevance of pricing online learning differently given the challenges and complexities that it gives everyone involved. Both of these make sense because it is typically the teachers who struggle more with the technical aspect of online learning. As the data shows, quite a number of the teachers are older than 35 years old so it may mean a steeper learning curve to the utilization of these online platforms. With regard to the other item, it emphasizes how the teachers are also feeling more burdened because of the new set-up and are, therefore, ruminating on the possibility of pricing online learning higher because of the greater requirement needed on their side. Looking at the items that the students scored much higher, these were on the importance of adjusting the delivery in online classes given that they are different form in-person lessons and the need to provide in-person classes as well to provide a mix of experiences. Both of these are pointed at the learning experience and the value that the student places in the process of acquiring new knowledge.

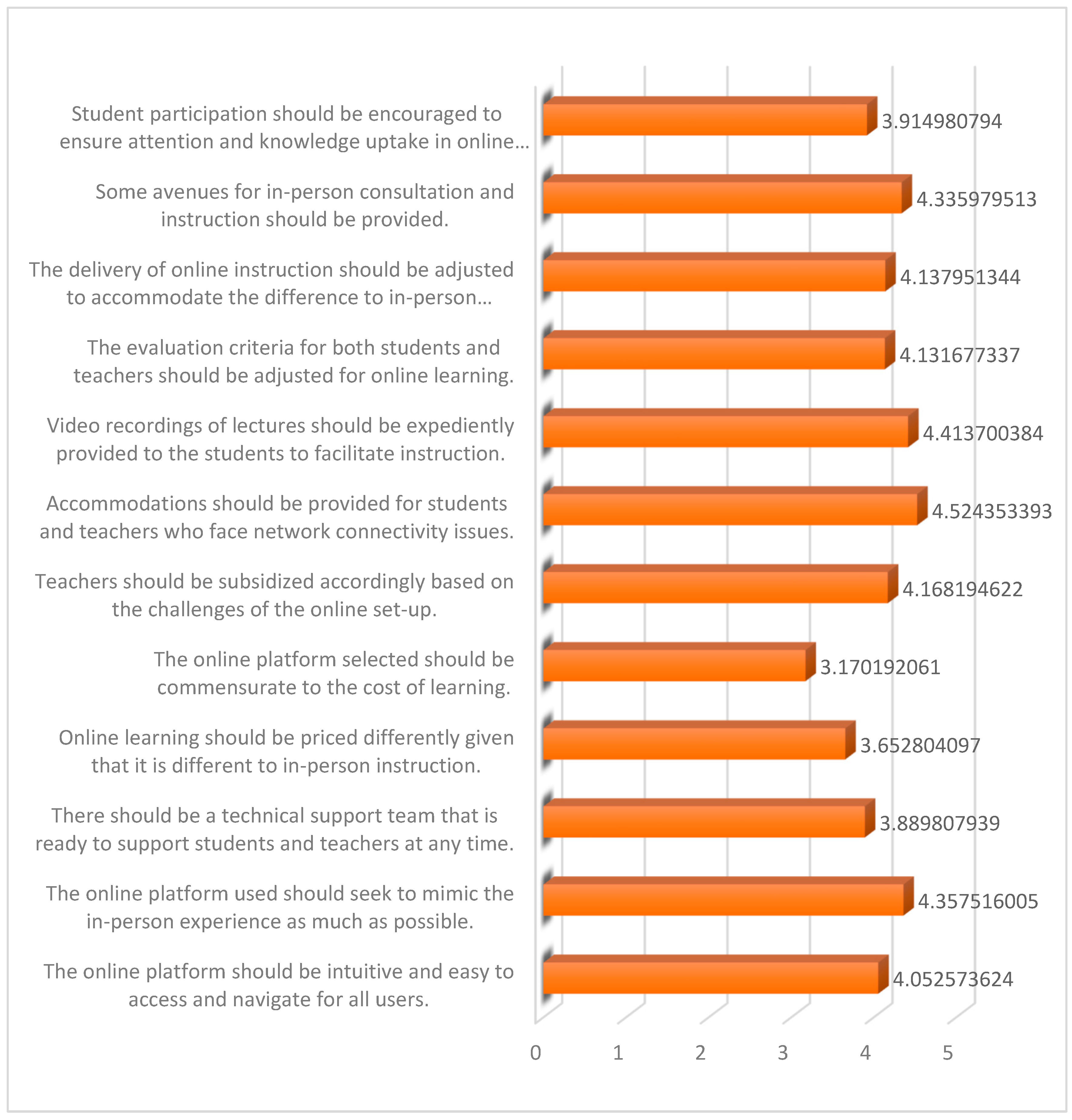

Going even deeper into the results, the differences were assessed for statistical significance using the independent samples t-test and the results indicate that all of the items show a statistically significant difference in the mean scores provided by the respondents. This shows the distinct paradigms through which teachers and students go through online learning. While there may be disparities, however, a final aggregated priority score was computed from the two groups and the ratings are shown in

Figure 18.

Among these, the six highest are going to be considered for the house of quality construction to represent the voice of the customers. Based on the scores in

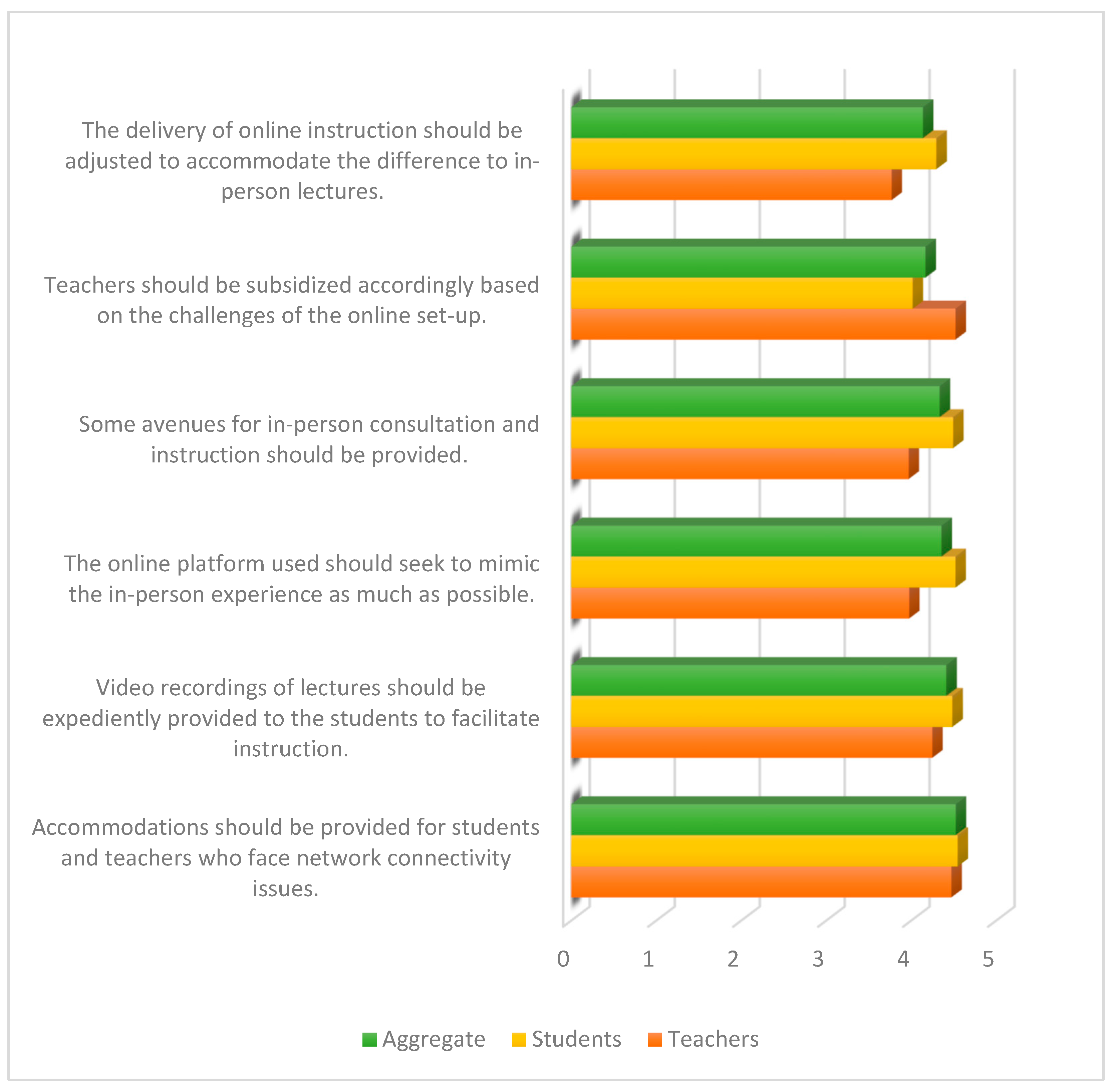

Figure 18, the six key items that were deemed to be of the highest priority are isolated in

Figure 19. The data visualized in the graph indicates the aggregate score along with the individual ratings by the teachers and students.

Among the six items that were of highest priority, the top two came from operational factors and these were the need to provide expedient delivery of video recordings and the provision of accommodations and considerations when network connectivity issues affect students and teachers. One technical and one financial factor were also covered in these priorities. The technical factor was the importance of choosing an online platform that best mimics the experience of in-person classes while the financial factor touched upon the need to subsidize teachers better based on the challenges of the online set-up. The last two priorities were functional in nature. These were the need to include opportunities for in-person consultation to supplement the online classes and the importance of adjusting learning methods to account for the difference in the online experience. With the voice of the customer now better understood, the section 5.6 constructs the house of quality for online learning.

5. Constructing the House of Quality for Online Learning

This section explains the construction of the house of quality for online learning in Omani HEIs from the VOC collected in this research work. There were three main aspects that needed to be added to the house of quality which are the relationship between the customer requirements and the technical requirements from the voice of the customer, the target direction of each of the requirements, and the correlation between requirements. These are all shown in

Figure 20 and are discussed accordingly.

The first element that needed to be included is the relationship between technical requirements of voice of customer and the established customer requirements for online learning. To analyze this, each of the customer requirements are detailed and the pertinent points regarding their relationship with the technical requirements are noted. In the customer requirements, the creation of environment of effective learning for students is the first requirement and this was shown to have a sufficiently strong relationship with four of the technical requirements. The first technical requirement is the need to have an online platform that best mimics in-person learning.

This makes sense as it would improve the learning context of those involved. Second technical requirement is in relation to teachers having to be subsidized better for the challenges of online learning. When it comes to this, the strong relationship is based on the importance of making teachers feel better about their role in online learning and this would extend to how well they carry out their roles as well. The two other requirements also have a high relationship which are related to network problems during the course of online learning and the importance of adjusting instructional delivery to the needs of the new method. The second customer requirement of ensuring that students gain knowledge and competence is highly connected to the former which is strongly related to selecting an online learning platform that translates the needs of in-person learning virtually, extending accommodations in case of connectivity issues, and the value of adjusting mode of instruction and delivery to leverage the new learning environment.

In addition to these, however, it is also found to be highly related to providing avenues for in-person consultation as this would allow for improved competence to be developed due to the additional time spent with the student. In terms of developing the innate curiosity of the student, this was the only factor which is highly related with an effective learning platform as this would lead to uninterrupted learning and the student can focus on their pursuit of new knowledge. Helping students to gain a favorable understanding of ethics and ethical practice also had no strong relationships, but this was found to be somewhat related to choosing the right platform, subsidizing teachers properly, and making sure delivery is appropriate.

For the requirement of making the student more confident and adaptable, this had no strong correlation to any of the technical requirements, but minor relationship was found on the ones that underscored seamless instruction. The same could be said for the customer requirement involving the need to develop strong and active citizens among the students along with cultivating the entrepreneurial spirit. The last requirement considered was ensuring that the education provided is, at the end of the day, cost-effective and this was the only factor which is strongly related to the item on paying the teachers more due to the hassles of online learning as this was the sole financial aspect considered.

With all the relationships established, the technical requirements that were drawn from the voice of the customer can be given a final prioritization score and these are also shown in

Figure 19. Another aspect of the house of quality is deciding the target direction of each requirement and this was evaluated based on whether they needed to be increased, decreased, or if a specific amount is to be prescribed. Apart from this, correlations between the requirements were also identified. This was done by carrying out a bivariate analysis on the scores given by both the teachers and the students. Those that were found to have a positive correlation that was statistically significant at the 0.05 level were deemed to have weak positive correlation while those that were significant at the 0.001 level were considered to be strong. A similar nomenclature was followed for negative correlations. The item-pairs that had no statistically significant correlation were noted as no relationship between factors.

6. Main Findings and Analysis Related to QFD Implementation in HEIs

In this section, the house of quality is discussed even further by highlighting some key conclusions that can be made in terms of how online learning is to be improved in Omani HEIs. In looking at the prioritization scores computed and shown in

Figure 20, there are two technical requirements that scored notably higher than the rest. These are the need to choose an online platform that aligns well with students and teachers and best imitates the nuances of in-person instruction and the need to adjust instruction delivery to rise up the challenges and complexities of communicating in an online environment. Both of these factors are in align with the main challenge for students and teachers to improve the delivery of coursework and course material in the online set-up. As such, universities should seek into evaluating platforms that can help to bridge the virtual disconnect that can happen in these classes while also helping teachers by giving them workshops and similar training and development opportunities that would give them a better handle on online teaching. Note that the data shows that majority of the teachers were thrust into this set-up without prior experience, so this study is certainly necessary.

The other four requirements also scored well in terms of priority but were relatively similar in the final assessment. This is not to say that these are not necessary in fortifying the online learning experience. Instead, a better analysis would be that they should be pursued after the top two priorities from House of Quality are finally addressed and covered by the relevant organizations.

As stated in section 1.2, there are four objectives were taken to execute this case study in the Higher Education Institutes in the Sultanate of Oman. The first two of these were to utilize QFD as a way of better understanding the issues and solve complexities that students and teachers, respectively, have faced in light to the shift to online learning from traditional learning in HEIs in Oman. Through the use of a survey questionnaire, the insights of the two groups on online learning was better understood. This led to an evaluation of the voice of the customer buoyed by the principles of QFD, and from this the six main requirements for improved online learning were identified. In addition to this, the house of quality analysis that was implemented in the study to refine the consideration of these six main requirements by evaluating how they relate to the standard requirements of learning and higher education. Among this, two main requirements were determined to be the most pertinent: the selection of an appropriate online learning platform that translates the nuances of in-person instruction into the virtual setting and the need to make changes and adjustments in the delivery of course material in this new set-up.

In the process of highlighting the priorities that should be pursued for online learning, the third research objective of the study was also addressed. This was regarding the identification of gaps in the current approach to online learning in Omani HEIs. These gaps were made evident in the collection of the data from both the students and the teachers as they indicated the aspects of online learning improvement that are most important to them and also addressing difficulty in implementing them. More than this, the entire analysis, from the use of QFD as driven by principles of TQM, was geared towards meeting the fourth objective of the case study, which is to provide recommendations to HEIs for enhancing the online learning experience. On this, the two priority requirements already stated are the focal point of the recommendation. However, the other four requirements that were identified in the study are helpful in bolstering the overall quality of online learning as well.

7. Conclusion

7.1. Academic and Technical Contribution

The practical implications for the study revolve around the aspects of online learning in Oman that needs attention. The data shows that the students and teachers are quite new to this set-up as a good number of them have only had experience with online learning during the shift due to the digital transformation. The implication is two-fold. First, the students are still adjusting to this new learning style and secondly, the teachers are still grappling with the challenges of translating instruction virtually. From this challenging context, it was found that the two groups have different priorities when it comes to improving online learning. The students were more focused on the learning experience itself and how they would better understand the course material. On the other hand, the teachers emphasized the logistical challenges of the set-up and how they need better support and financial incentives to work through the hurdles. Ultimately, the study identified six requirements that addresses the needs of both groups albeit weighted more strongly towards the needs of the students and this allowed for recommendations for improvement to be made.There is much less to be said about theoretical implications. However, the study does help in expanding the body of knowledge relating to the use of TQM and QFD in the higher education setting, and more so in online learning. In addition to this, the case study also provides much needed insight on the implications in the educational experiences of students and teachers in the HEIs, which is essential as researchers begin to grapple more holistically with the industry 4.0 effects.

7.2. Managerial Implication

In the implementation, there are many managerial implication related to institutional leadership, changing organizational structure, financial commitment, training to the staff and creating smooth environment in learning and teaching. Among these factors, the institution leader’s decision is more important to adopt or not to adopt the new technology based learning. Institutional leader is the responsible person to implement and test the new strategies in learning and teaching including online learning (Rajakannu, A et al, 2024). Similarly, finance manager role is also equally important to realize the importance of new methodology and floating money to procure the digital gadgets and relevant software in relate to online teaching.

7.3. Limitations and Future Work

The limitation of the study is the sample size and group of the students. This study had been done in HEIs which are conducting engineering related programmes. There may be a chance to have deviation if the study will conduct in the institutes which are concentrating on arts and science curriculum. Even though the online is essential learning methodology in future, the outcome or prediction may vary slightly for region but not in a major level. However, we can conclude that the QFD is an excellent tool to assess the effectiveness of the online learning methodology.

As a final area of discussion, some recommendations for future work are provided. There are two types of recommendations that are covered. The first are methodological recommendations, which are improvements to the current data collection and analysis approach done in this study that can be applied in new iterations of the research. Second are recommendations that can be done to extend and expand the insights that were developed in this work. In terms of the methodological recommendations, the most pertinent is the need to expand the sample of the study. This work is more closely related to a case study given that the sample was strictly from a single college of a university. For a better understanding of HEIs in Oman, a good mix of both public and private institutions should be included in future work. Another methodological improvement would be the potential of triangulating the data collected by including aspects of qualitative research as well, specifically the use of semi-structured interviews with students and teachers to help elaborate upon the data. This was not done in this case study due to the constraints of time and logistics, but it would certainly add to the depth of information gathered.

Finally, for the recommendations pertaining to further research that can be pursued as a way of building upon this work’s conclusions, the first is a more definitive look into online teaching strategies, identifying the specific aspects of teaching and pedagogy that teachers apply that may have a positive or negative effect on the learning experience. This study took a broad approach on online learning so a deeper dive would certainly be productive. In a similar vein, it would be interesting to evaluate how different online learning setups (e.g., pure virtual, mix of in-person and virtual, etc.) are affecting the overall learning outcomes of students in HEIs based on academic achievement and their personal evaluation of their scholastic development. This would provide necessary nuance on the entire discussion of online learning and would also lend insight on its effects on the student’s academic growth.

References

- Abbas, J. (2020). ‘Impact of total quality management on corporate green performance through the mediating role of corporate social responsibility’, Journal of Cleaner Production, 242. [CrossRef]

- Adam, A. M. (2020). ‘Sample size determination in survey research’, Journal of Scientific Research and Reports, 26(5), pp. 90-97. [CrossRef]

- Al-Bashir, A. (2016). ‘Applying total quality management tools using QFD at higher education institutions in gulf area (Case study: ALHOSN University)’, International Journal of Production Management and Engineering, 4(2), pp. 87-98. [CrossRef]

- Al-Emran, M. and Shaalan, K. (2017). ‘Academics’ awareness towards mobile learning in Oman’, International Journal of Computing and Digital Systems, 6(1), pp. 45-50. [CrossRef]

- Al-Emran, M., Elsherif, H. M. and Shaalan, K. (2016). ‘Investigating attitudes towards the use of mobile learning in higher education’, Computers in Human behavior, 56, pp. 93-102. [CrossRef]

- Ali, W. (2020). ‘Online and remote learning in higher education institutes: A necessity in light of COVID-19 pandemic’, Higher Education Studies, 10(3), pp. 16-25. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M., Raza, S.A., Qazi, W. and Puah, C.-H. (2018), "Assessing e-learning system in higher education institutes: Evidence from structural equation modelling", Interactive Technology and Smart Education, Vol. 15 No. 1, pp. 59-78. [CrossRef]

- Al-Najar, N. (2016). ‘View of education development in Oman’, International Journal of Academic Research in Education and Review, 4(1), pp. 10-18.

- Al-Qayoudhi, S., Hussaini, S. S. and Khan, F. R. (2017). Application of total quality management (TQM) in higher education institution (HEI) in Oman: Shinas College of Technology: A Case Study’, Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews, 5(1), pp. 21-32.

- Al-Sarmi, A. M. and Al-Hemyari, Z. A. (2014). ‘Goals and Objectives: Statistical techniques and measures for Performance Improvement of HEIs in Oman’, International Journal of Management in Education, 8(3), pp. 244-264. [CrossRef]

- Aminbeidokhti, A., Jamshidi, L. and Mohammadi Hoseini, A. (2016). ‘The effect of the total quality management on organizational innovation in higher education mediated by organizational learning’, Studies in Higher Education, 41(7), pp. 1153-1166. [CrossRef]

- Amuthakkannan,R., Abubacker,K.M., Babu,S.V (2018). ‘Improvement of QFD effectiveness with blend of Voice of Customer and Red Green chart on complex mechatronics products, World Journal of Engineering Research and Technology, Vol 4, Issue 1,pp.437-451.

- Androniceanu, A. (2017). ‘The three-dimensional approach of Total Quality Management, an essential strategic option for business excellence’, Amfiteatru Economic, 19(44), pp. 61-78.

- Aslam S, Akram H, Saleem A, Zhang B. 2021. ‘Experiences of international medical students enrolled in Chinese medical institutions towards online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic’, The open access journal for life and environment, PeerJ 9:e12061. [CrossRef]

- Aslam, S., Saleem, A., Akram, H., Parveen, K., Hali, A.U. (2021). The challenges of teaching and learning in the COVID-19 pandemic: The readiness of Pakistan. Academia Letters,, Article 2678. [CrossRef]

- Cetinkaya, C., Kenger, O. N., Kenger, Z. D. and Ozceylan, E. (2019). ‘Quality function deployment implementation on educational curriculum of industrial engineering in University of Gaziantep’, in Industrial Engineering in the Big Data Era (pp. 67-78). Springer, Cham.

- Erdil, N. O. and Arani, O. M. (2019). ‘Quality function deployment: more than a design tool’, International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 11(2), pp. 142-166. [CrossRef]

- Gangurde, S. R. and Patil, S. S. (2018). ‘Benchmark product features using the Kano-QFD approach: a case study’, Benchmarking: An International Journal, 25(2), pp. 450-470. [CrossRef]

- Gawande, V. (2015). ‘Development of blended learning model based on the perceptions of students at higher education institutes in Oman’, International Journal of Computer Applications, 114(1), pp. 38-45. [CrossRef]

- Hakro, A. N. and Mathew, P. (2020). ‘Coaching and mentoring in higher education institutions: a case study in Oman’, International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 9(3), pp. 307-322. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Z., Grigg, N.P (2020) ‘ Enhancing voice of customer prioritisation in QFD by integrating the competitor matrix’, International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, Volume 70, Number 1, 2020, p. 217-229(13).

- Ismail, O. and Al Shanfari, A. (2014). ‘Management of private higher education institutions in the Sultanate of Oman: A call for cooperation’, European Journal of Social Sciences, 43(1), pp. 39-45.

- Jamali, R., Aramoon, H. and Mansoori, H., 2010. Dynamic quality function deployment in higher education. JJMIE, 4(4).

- Janet S. Casta, Grace C. Bangasan, and Dario A. Mando, (2021) Contemporary Thai Primary Schools through the Years, ASR CMU Journal of Social science and Humanities, VOl.7 No.1 pp 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Kiran, D. R. (2016). Total Quality Management: Key Concepts and Case Studies. Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Lam, J. S. L. and Bai, X. (2016). ‘A quality function deployment approach to improve maritime supply chain resilience’, Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 92, pp. 16-27. [CrossRef]

- Matorera, D. and Fraser, W. J. (2016). ‘The feasibility of Quality Function Deployment (QFD) as an assessment and quality assurance model’, South African Journal of Education, 36(3). [CrossRef]

- Nadim, Z. S. and Al-Hinai, A. H. (2016). ‘Critical success factors of TQM in higher education institutions context’, International Journal of Applied Sciences and Management, 1(2), pp. 147-156.

- Nasim, K., Sikander, A. and Tian, X. (2020). ‘Twenty years of research on total quality management in Higher Education: A systematic literature review’, Higher Education Quarterly, 74(1), pp. 75-97. [CrossRef]

- National Center for Statistics and Information. (2021). Education. Retrieved from https://data.gov.om/OMEDCT2016/education [Accessed on 22 February 2021].

- O’Neill, P., Sohal, A. and Teng, C. W. (2016). ‘Quality management approaches and their impact on firms׳ financial performance–An Australian study’, International Journal of Production Economics, 171, pp. 381-393.

- Oman Vision 2040. (2020). National Priorities. Retrieved from https://www.2040.om/en/national-priorities/ [Accessed on 22 February 2021].

- Pambreni, Y., Khatibi, A., Azam, S. and Tham, J. (2019). ‘The influence of total quality management toward organization performance’, Management Science Letters, 9(9), 1397-1406. [CrossRef]

- Patten, M. L. (2016). Questionnaire Research: A Practical Guide. Routledge.

- Psomas, E. and Antony, J. (2017). ‘Total quality management elements and results in higher education institutions’, Quality Assurance in Education, 25(2), pp. 206-223. [CrossRef]

- Puglieri, F. N., Ometto, A. R., Salvador, R., Barros, M. V., Piekarski, C. M., Rodrigues, I. M. and Diegoli Netto, O. (2020). ‘An environmental and operational analysis of quality function deployment-based methods’, Sustainability, 12(8), 3486. [CrossRef]

- Rajakannu, A.; Hassan Al bulushi, A.; K, V. Challenges in the automation of Education 4.0 using Industry 4.0 Technologies - A Systematic Review. Preprints 2024, 2024082039. [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.A., Qazi, Z., Qazi, W. and Ahmed, M. (2022), "E-learning in higher education during COVID-19: evidence from blackboard learning system", Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, Vol. 14 No. 4, pp. 1603-1622. [CrossRef]

- Sagnak, M., Ada, N., Kazancoglu, Y. and Tayaksi, C. (2017). ‘Quality function deployment application for improving quality of education in business schools’, Journal of Education for Business, 92(5), pp. 230-237. [CrossRef]

- Sarrab, M., Al Shibli, I. and Badursha, N. (2016). ‘An empirical study of factors driving the adoption of mobile learning in Omani higher education’, International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(4), pp. 331-349. [CrossRef]

- Shams, S. R. (2017). ‘Transnational education and total quality management: a stakeholder-centred model’, Journal of Management Development, 36(3), pp. 376-389.

- Slimi, Z. (2020). ‘Online learning and teaching during COVID-19: A case study from Oman’, International Journal of Information Technology and Language Studies, 4(2), pp. 44-56.

- Tawafak, R. M., Romli, A., Malik, S. I., Shakir, M. and Farsi, G. A. (2019). ‘A systematic review of personalized learning: Comparison between e-Learning and learning by coursework program in Oman’, International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 14(9), pp. 93-104. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The geographical distribution of graduation, universities and colleges across governorates of the Sultanate of Oman in 2017-2018 (Home - NCSI PORTAL, 2020).

Figure 1.

The geographical distribution of graduation, universities and colleges across governorates of the Sultanate of Oman in 2017-2018 (Home - NCSI PORTAL, 2020).

Figure 2.

Number of enrolled students in HEIs in Oman from 2007 to 2018 (Oman NCSI, 2021).

Figure 2.

Number of enrolled students in HEIs in Oman from 2007 to 2018 (Oman NCSI, 2021).

Figure 3.

Number of employed teachers in HEIs in Oman from 2013 to 2018 (Oman NCSI, 2021).

Figure 3.

Number of employed teachers in HEIs in Oman from 2013 to 2018 (Oman NCSI, 2021).

Figure 4.

House of quality framework.

Figure 4.

House of quality framework.

Figure 5.

Distribution of the teacher respondents by the gender.

Figure 5.

Distribution of the teacher respondents by the gender.

Figure 6.

Distribution of teachers by age group.

Figure 6.

Distribution of teachers by age group.

Figure 7.

Distribution of teachers by work designation.

Figure 7.

Distribution of teachers by work designation.

Figure 8.

Distribution of teachers by department.

Figure 8.

Distribution of teachers by department.

Figure 9.

Distribution of teachers by months of experience with online learning.

Figure 9.

Distribution of teachers by months of experience with online learning.

Figure 10.

Distribution of teachers by preferred online platform.

Figure 10.

Distribution of teachers by preferred online platform.

Figure 11.

Distribution of students by gender.

Figure 11.

Distribution of students by gender.

Figure 12.

Distribution of students by age group.

Figure 12.

Distribution of students by age group.

Figure 13.

Distribution of students by their college department.

Figure 13.

Distribution of students by their college department.

Figure 14.

Distribution of students by time spent with online learning.

Figure 14.

Distribution of students by time spent with online learning.

Figure 15.

: Distribution of students by preferred online platform.

Figure 15.

: Distribution of students by preferred online platform.

Figure 16.

Summary of responses of both teachers and students to the technical requirements of online learning.

Figure 16.

Summary of responses of both teachers and students to the technical requirements of online learning.

Figure 17.

Differences of scores given by teachers and students for each of the items.

Figure 17.

Differences of scores given by teachers and students for each of the items.

Figure 18.

Aggregated scores for each of the items in the questionnaire.

Figure 18.

Aggregated scores for each of the items in the questionnaire.

Figure 19.

Highest priority items based on computed aggregate scores.

Figure 19.

Highest priority items based on computed aggregate scores.

Figure 20.

House of quality for online learning based on survey taken in HEIs, Oman.

Figure 20.

House of quality for online learning based on survey taken in HEIs, Oman.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).