1. Introduction

In recent years, more than half a million asylum applications are submitted across European countries annually, peaking to more than one million some years, as in 2015, 2016 and 2023 (

https://euaa.europa.eu/). For these forced migrants1, learning the language of the host country is not just a tool for communication but a fundamental element that affects every aspect of their life: language skills are critical for young adults to access education and training programs, and more generally for finding and maintaining employment; language is crucial for navigating the legal and bureaucratic processes involved in asylum applications, accessing healthcare and other essential services ; language allows understanding the culture and values of the host society, which facilitates integration and reduces cultural misunderstandings, while enhancing migrants’ confidence to participate in their new communities.

A significant amount of scientific research has been done on language teaching for migrants, spanning disciplines including linguistics, education, sociology, and psychology. Research emphasizes the importance of tailored, practical, and supportive language learning approaches focusing on real-world application and cultural sensitivity, while also considering the specific needs of migrant learners [

1,

2]. The importance of incorporating learners’ cultural background has been highlighted particularly for forced migrants who often show emotional vulnerability due to a range of traumatic experiences and stressors associated with their displacement [

3,

4]). As a result, recommendations have been made to incorporate content, like texts and stories, from the learners’ own cultures and experience into the curriculum [

5,

6]. Another way of connecting the language classroom to the learners’ culture is through recognizing the languages that they speak. Instead of discouraging the use of their native languages, as was traditionally recommended [

7], the teacher can draw connections between the learners’ native language(s) and the new language. This approach fits within theories on bilingual education initiated in the eighties [

8,

9], and more recently within theories of translanguaging [

4,

10]. Translanguaging is the use, by multilingual individuals, of their entire linguistic repertoire to communicate, often blending elements from different languages in a flexible way. Capitalizing on this spontaneous tendency from learners, pedagogical translanguaging (PTL) involves instructional strategies that purposefully incorporate two or more of the learners’ languages as part of the teaching process [

11].

Recent research started to describe PTL tools that can be used in the classroom, and some studies assessed their efficiency in classrooms with migrant students, both in terms of language learning [

11,

12] and in terms of emotional well-being [

13,

14,

15]. But research on pedagogical translanguaging in the context of forced migrants is scarce. Although some studies provide insights into the potential of using PTL practices in that population [

16,

17], the specificity of these classrooms poses various challenges to the feasibility of implementing the method itself. Regarding teachers, many of those involved in forced migrants’ classrooms are not professionals and have little training in linguistics and/or (second) language teaching. Moreover, they usually do not speak the learners’ languages and classrooms often involve a diversity of languages. Regarding learners, forced migrants sometimes have low levels of education and therefore low levels of metalinguistic knowledge on their own languages, which may render reflecting on their own language challenging.

The present study aimed at developing a pedagogical tool to teach L22 French and Greek derivational morphology, assess its feasibility in the specific context of language teaching classrooms for adult migrants in Switzerland, Greece and France, and also provide a preliminary assessment of its impact on learners’ emotions. Derivational morphology, i.e., the formation of new words by adding affixes to the root (prefixes, suffixes, infixes etc.), was chosen for two reasons. First, morphological awareness has a significant impact on L1 literacy acquisition and vocabulary development [

18,

19]. Second, derivational morphology is seldom taught explicitly in L2 pedagogies, but recent evidence highlights its relevance [

20]. Two hypotheses regarding PTL underlie the study. The first hypothesis is that, at the cognitive level, PTL facilitates learning through the enhancement of positive transfer mechanisms, i.e., the transfer of what is similar between L1 and L2, and the reduction of negative transfers, i.e., errors due to the influence of L1 properties that are different in L2. The second hypothesis is that, at the emotional level, acknowledging and valuing the linguistic and cultural identities of students favors emotional well-being, enhancing positive emotions and reducing negative ones. The PTL approach is expected to be particularly beneficial to forced migrants, who often suffer high emotional vulnerability [

21]. In the following sections, we briefly describe the theoretical underpinnings of these two hypotheses.

1.1. Transfer Effects and Analogical Reasoning in L2 Learning

The process of learning a new language fundamentally differs from the task a baby is confronted to when acquiring her first language. The acquisition of a new language takes place on the background of pre-existing knowledge of one or more languages, which serves as the foundation on which L2 knowledge is developed [

9,

22]. And indeed, one of the clearest evidence gathered in psycholinguistic research on L2 learning is that it is strongly influenced by that pre-existing language knowledge. Negative transfer or ‘interference’ arises when the native language causes errors in the acquisition of the L2 due to differences between the two, while positive transfer or ‘facilitation’ arises when the native language facilitates L2 learning in virtue of their similarities. Negative transfer is found at all linguistic levels: phonological, syntactic, lexical and pragmatic. Learners often transfer phonological rules and sounds from their L1 to their L2, leading to pronunciation difficulties and accents that can hinder comprehension [

23]. The syntactic structure of L1 also interferes with the correct formation of sentences in L2, which may for example result in errors related to word order, inflectional morphology, or sentence structure (e.g., [

24] for the acquisition of L2 French). Negative transfer also arises at the lexical level when learners incorrectly assume that words in their L1 have direct equivalents in L2, leading to errors in word choice, meaning, and collocations. This is often seen in the use of words that look similar in two languages but have different meanings, i.e., false friends or false cognates [

25]. Much less research has been conducted on positive transfer, but facilitation in the learning of cognate words represents a clear illustration of it, while finely controlled experimental protocols have shown that under some circumstances, L2 learners may even surpass L1 speakers [

26].

The role of transfer in L2 learning comes as no surprise given the well-acknowledged role of analogy in the acquisition of new knowledge in cognitive models of learning [

27,

28,

29]. Analogy serves as a key adaptive mechanism for the formation, extension, and retrieval of concepts, connecting new situations to previous experience [

30]. The concept of analogical encoding refers to the active comparison of two examples, making learners more attentive to their structural similarities. Comparison increases the probability of finding the common underlying principle when encountering a similar situation and thus promotes the abstraction of schemas [

31,

32,

33]. The relevance of analogical processing has been demonstrated in cognitive domains such as school-based skills, understanding, reasoning, problem-solving, conceptual development, and more generally scientific discovery, in both novice and more experienced participants [

34,

35]. It is much less known in the field of L2 learning. A few studies have nevertheless indirectly related to it; for example, when explicitly questioned about the languages they had acquired and their attitudes towards these languages, bilingual speakers highlight their use of grammatical analogies to form complex sentences in both languages [

36]. Learners of a new language also report noticing analogies for similar words in the languages they already know, which arguably facilitates their understanding and memorization of new words [

37].

We propose that transfer effects in L2 learning are the manifestation of the core cognitive mechanism of analogical encoding by which learners link new knowledge of the L2 to the languages they already know. Interestingly, the vast majority of L2 research has focused on negative transfer, and therefore on the penalizing influence of L1 knowledge. We see at least two causes for that state of fact. First, whereas negative transfer is directly observable as an error, positive transfer is not directly observable, since it gives rise to correct production. Second, many datasets reporting evidence for negative transfer may as well be interpreted as evidence for positive transfer. The reason is that conclusions are usually drawn from the observation that speakers whose L1 is dissimilar to the L2 differ from speakers whose L1 is similar to the L2. This difference is typically interpreted as indicating that speakers of a dissimilar L2 make more errors; however, it could as well indicate that speakers of a similar L2 make less errors. The issue is well-known in experimental research and has to do with the need of a proper baseline to allow interpreting the direction of a difference. Despite the fact that evidence does not allow to determine the polarity of transfer effects, most theoretical models have concluded in favor of negative transfer [

22]. This conclusion has had important and unfortunate consequences on teaching practices, fueling approaches that ban learners’ languages from the classroom.

1.2. Emotions in L2 Learning

While the significance of emotions in learning was largely overlooked in the 1990s, emotions are nowadays acknowledged as components of cognition that are essential for learning. Emotional states affect attention: positive emotions enhance focus and engagement, while negative emotions lead to distraction and reduced attention [

38,

39]. Emotions also impact both the encoding and retrieval of memories: information associated with strong emotions is often better remembered [

40].

Language classrooms are filled with a wide range of emotions such as the pleasure of learning, pride, anxiety, shame, and boredom that are likely to impact L2 learning performance. As early as 1978, Krashen put forth the concept of ‘affective filter’, according to which emotions such as fear, shame, self-doubt, or boredom have the potential to negatively impact language learning [

41]. The literature in the field has primarily focused on negative emotions, particularly anxiety, but also shame and guilt, which are negatively related to L2 learning (see [

42] for a review). More recently, studies also highlighted the importance of positive emotions in L2 learning, arguing that they facilitate the development of cognitive resources but also contribute to promoting psychological resilience and dissipating the prolonged effects of negative emotions in the face of frustration [

43,

44].

Wide-scale cross-sectional and longitudinal studies on emotions related to the learning context and their effects on school and academic performance emerged in the early 2000, giving rise to deeper theorizing of emotions in education and their relationships with other core concepts like control, value, motivation and effort regulation [

45,

46,

47]. Data were collected through self-report questionnaires designed to assess students’ emotions related to academic settings (in particular, the Achievement Emotions Questionnaire, AEQ, [

48]. The control-value theory of emotions assumes that students’ emotional experiences are shaped by their perceptions of control over their learning outcomes and the value they place on academic tasks and outcomes. Whereas high levels of control and value trigger positive emotions like hope, pleasure and pride, low levels trigger negative emotions like anxiety or despair. Emotions, in turn, influence intrinsic motivation (engaging in an activity for its inherent satisfaction), extrinsic motivation (engaging in an activity to obtain rewards or avoid punishment) and effort regulation (the ability to regulate one’s efforts and persevere in the face of difficulties), which impact learning performance. Positive emotions, especially positive activating emotions, increase the levels of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and effort regulation, leading to beneficial effects on learning, while negative emotions have opposite effects. The control-value model thus relies on a causal chain linking control-value to emotions, emotions to motivation, and motivation to learning performance itself, while feedback loops between these levels are also at play.

The validity of the control-value theory of emotions in the context of L2 learning was assessed through different studies, either directly or indirectly. A literature survey of 146 reviews and quantitative studies between 1970 and 2019 showed that a number of data points support the theory [

42]. More recently, studies on Iranian and Chinese students learning L2 English employed a modified version of the AEQ adjusted to L2 education contexts and brought further support to the theory, showing that perceived control and value are positively linked to positive emotions and to language learning performance [

49,

50,

51].

Importantly, evidence suggests that control and value are themselves influenced by individual distal factors, such as gender, beliefs and achievement goals, but also by contextual distal factors, like the learning environment: teaching that promotes autonomy and cooperative goals help students develop positive beliefs about their ability to succeed, influencing their control and value perceptions, and thus the emotions experience [

47]. Such findings highlight the importance of developing pedagogical tools that enhance learners’ perception of the control and value of their language learning endeavor.

1.3. Language Teaching Practices, Analogical Reasoning and Emotions

There is a longstanding tradition of teaching foreign languages in isolation from the learners’ native languages, even in programs designed to foster bilingual or multilingual skills, following what is sometimes referred to as ‘the two solitudes’ [

52]. This approach is central to various second language teaching pedagogies, such as the Direct Method, the Audiolingual Method, and the Communicative Approach. The ‘two solitudes’ approach aims at reducing interference among languages, i.e., negative transfer, and maximizing L2 input, which has been found to play an important role in L2 learning [

53]. This ‘island’ approach ignores the vast array of studies in cognitive science showing that analogy is a powerful learning tool enabling pattern abstraction and predicting learning efficiency, such that learners’ linguistic resources actually constitute significant bootstraps to L2 learning, rather than obstacles. The isolationist approach also ignores the role of emotions and the role of contextual distal factors that drive them, as it vehicles a view of multilingual learners as incompetent students whose native languages inhibit the L2 learning process, underestimating the importance of learners’ empowerment [

54], and most probably also their perception of control and value of language learning.

A radically different pedagogy emerged in the nineties, mostly driven by sociolinguistic considerations regarding language and cultural diversity awareness in the context of migrants’ education in low-economic areas. The notion of ‘translanguaging’ was initially introduced by a Welsh educator to describe multilingual speakers’ spontaneous switching between languages for input and output in the classroom These studies were further developed into a broader theoretical framework applying translanguaging in educational settings to enhance teaching and learning for multilingual students, referred to as pedagogical translanguaging [

4,

9,

10]. Indeed, even though learners spontaneously use their native languages in the classroom when allowed to do so, the deeper process of explicit comparison between L1 and L2 is seldom observed in spontaneous exchanges. In order to trigger it, guided analogical encoding from the teacher is necessary, i.e., providing support for learners in making comparisons using explicit materials [

32]. Examples of pedagogical translanguaging practices and implementations for teaching purposes include allowing speakers of the same L1 to sit next to each other and speak together to compensate for lack of L2 knowledge, using the dictionary to translate the L2, comparing L1 and L2 and highlighting similar elements like cognates, or to convey an untranslatable term specific to one’s culture [

11].

Several studies emerged over the past few years proposing pedagogical tools to teachers (see for example the guides by [

5,

55], and assessing their efficiency through controlled protocols [

11,

54]. PTL was particularly developed in the teaching of derivational morphology in the formal setting of primary school education [

12,

56]. For example, the efficiency of PTL in morphological awareness was assessed in 10-year-old Basque-Spanish bilingual children attending a school in the Basque Autonomous Community in Spain and learning English as a foreign language [

12]. The teaching intervention involved techniques encouraging learners to compare the way complex words are formed in the three languages they know and/or learn. Morphological awareness significantly improved in learners who attended the PTL teaching intervention as compared to the control group who followed their regular program. Interestingly, the use of PTL in L2 teaching was found to have significant benefits not only for the development of morphological awareness in the L2 but also in the L1, thus facilitating the development of L1 literacy [

12,

20]. Beneficial effects of PTL were not only found on language learning, but also on enhancing positive attitudes and emotions in the learning process [

12,

25,

56,

57].

1.4. Goals of the Current Study

Capitalizing on recent studies showing the usefulness of pedagogical translanguaging in the learning of derivational morphology in children, the current study developed a pedagogical tool focusing on the teaching of derivational morphology to adult migrants. We focused on derivational morphology because recent studies show that allowing students to draw on their entire linguistic repertoire facilitates deeper comprehension of complex words, leading to a more profound understanding of how words are formed and how meaning changes with the addition of affixes, enhancing students’ metalinguistic awareness. Moreover, derivational morphology is not commonly taught in L2 textbooks and pedagogical materials, even though the command of derivational affixes and rules facilitates the productive formation of new, morphologically complex words and enriches lexical competence [

20]. The cornerstone of the PTL tool we developed lies in the systematic, explicit linking between the learners’ existing languages’ knowledge and the new language.

The PTL tool was implemented in language classrooms for migrants involving both forced and voluntary migrants. Forced migrants, contrary to voluntary migrants, have left their countries because their lives were threatened, and they often continue experiencing stress during the migration journey, and even once arrived in the resettlement country where they are exposed to post-migratory stressors involving administrative challenges and uncertainty around basic needs, and more generally social and cultural isolation [

58]. Their integration crucially depends on the mastery of the country language, and they may therefore show specificities in regard to their emotions in the L2 classroom. As reviewed in the Introduction, recent studies based on the control-value theory of emotions have started finely exploring emotions in different profiles of learners, however, none of them has examined emotions in forced migrants. Additionally, forced migrants are often multilingual speakers, while their education level is usually low; these cognitive specificities may have an impact on their metalinguistic awareness in the L1, and may thus also impact the feasibility of the PTL approach.

The tool was designed, implemented and evaluated in migrants’ classrooms, involving both forced and voluntary migrants, in order to explore two goals, which are exemplified below and are based on the two research hypotheses formulated in the Introduction:

- To assess the overall feasibility of the tool in migrant language classrooms. To do so, teachers and learners filled in detailed questionnaires about their attitudes toward the PTL tools as well as their perception of its learning benefits. Learners also answered questions regarding key individual variables susceptible to influence their attitudes and perception (age, years in the host country, multilingualism, years of education, SES, proficiency level in the target language, number of course hours completed, frequency of L2 language practice, perceived similarity between L1 and L2). We expected that teaching derivational morphology through PTL activities is feasible in migrants’ classrooms, including forced migrants who may show low levels of education, because it activates the spontaneous analogical reasoning mechanism underlying L2 learning, and it has been shown to be feasible and efficient in children. Comparisons of L1 and L2 are argued to enhance learners’ awareness about the similarities and the differences between the two languages and, consequently, exploit positive but also negative transfer to learners’ advantage.

- To conduct a preliminary assessment of the emotional impact of this new PTL tool in migrant language classrooms. To do so, learners rated the strength of 13 emotions they experienced during the PTL lesson, comparatively to the emotions they feel in their usual lessons. Both epistemic emotions (related to the cognitive processes involved in learning, understanding, and knowledge acquisition) and achievement emotions (experienced in relation to one’s accomplishments, successes, or failures in learning or task performance) were measured [

46]. Anxiety and boredom, which are considered both epistemic and achievement emotions, were also assessed. We expected that setting migrant learners in the position of reflecting on their native language that they master and relate to would increase their sense of control and the value they grant to the learning task, resulting in reduced negative emotions in PTL classroom compared to the traditional classroom, and enhanced positive emotions. These effects were expected to be particularly salient in forced migrants, due to their emotional vulnerability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 141 L2 learners took part to the study: 96 learners attended 14 L2 French classes in Switzerland, 31 attended 7 L2 Greek classes in Greece and 14 attended 2 L2 Greek classes in France. Since there are no relevant differences between the three groups, all participants are treated as a single group. Learners were aged between 14 and 77, with a mean age of 39 (M = 39.1, SD = 14.0). Their socio-economic status ranged between poor (N=15) and upper-middle class (N=17). The participants’ level of education varied between 0 and 18 years (M = 12.7, SD= 4.9). Learners came from nearly 40 different countries spread on all continents (most of them coming from Europe, Asia, and the Americas) and spoke in total nearly 30 different languages. Most of them spoke more than one language (N = 127); learners’ multilingualism ranged between 1 and 7 languages, with an average of 2.8 languages spoken in addition to the native language. The average time spent in the host country was 5 years, ranging between 1 and 20 years (M = 5.1, SD = 6.4). Learners had different L2 proficiency levels, below A1 (N=29), A1 (N=56), A2 (N=31), B1 (N=14), B2 (N=6), C1 (N=1), while most of them were basic users of the L2 (A1 and A2 level). Exposure to the L2 ranged between less than 80 hours and more than 800 hours, but most participants had less than 500 hours (less than 80 hours: N = 44; between 80 and 200 hours: N = 45, between 200 and 500 hours: N = 23). Additionally, the opportunity to practice the host country language ranged between ‘never’ and ‘often’, most of the answers being ‘sometimes’ (N = 47). A total of 79 participants felt forced to leave their country (N = 18 in Greece, N = 62 in Switzerland), while a subset of them also felt threatened (N = 58). Forced migrants did not significantly differ from voluntary migrants in terms of SES (W = 1510, p = 0.143) but showed a significantly lower level of education (W = 1447.5, p = 0.021) and spent significantly less time in the host country (W = 1508, p = 0.019).

Thirteen different teachers gave a total of 23 lessons: 14 in Switzerland, 7 in Greece and 2 in France. Seven of them were professional L2 teachers, the other 6 teachers had experience in L2 training but no professional background.

Teachers and learners were all volunteers in the study. Teachers were recruited through the authors’ network of schools for migrants in the three countries. Participants signed the consent form translated in 14 languages (Albanian, Arabic, Chinese, English, Farsi, French, German, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, Tigrinya, and Turkish). The study was approved by the ethics commission of the University of Geneva (CUREG-2022-02-33).

2.2. Materials and Procedure

2.2.1. Pedagogical Cards and Lesson’s Protocol

Fifteen pedagogical cards were built, 8 in French and 5 in Greek. All focus on the teaching of derivatives, both the root and the affixes, have the same structure, but they vary in the number of affixes introduced and their level of abstractness, such that teachers were free to choose the card that best suit the level of proficiency of their students. Suffixes and prefixes were selected on the basis of their frequency and productivity in the language (French database Polymots,

https://polymots.huma-num.fr/): only frequent and productive morphemes were used.

Each card involves 5 steps illustrated below:

Familiarization to the notion of word family. Learners are presented orally with 3 lists of words sharing the same root, i.e., derivatives, while each list is depicted in a different color and is associated to a picture of a family of children, parents and grandparents.

Introduction to the words of the family. Between 6 and 10 derivatives are presented in short sentences illustrated by pictures (taken from the database on arasaac.org and from

https://www.freepik.com/). Participants read the sentences aloud and then write each target word, i.e., the derivative in the text, below the sentence.

PTL exercise on the root. (i) Learners translate each target word in their L1 using a translation tool (dictionary or on-line application); (ii) Learners reflect on the presence or absence of a ‘fixed’ part in the words in their L1 (the root); (iii) Learners find other words in their L1 sharing that fixed part and translate them into French; (iv) Learners exercise their memory for the new taught words through translation exercises (from L2 to L1 and from L1 to L2) within the groups.

Introduction to the affixes. Three to four of the affixes encountered in Step 3 are set on the blackboard and participants search for words in the L2 containing these affixes. Each affix is represented with a symbol that illustrates its meaning. A short exercise of pairing new affixed words to the three symbols is provided to train learners on the symbols.

PTL exercise on the affixes. (i) Participants are presented with lists of words sharing each of the affixes and find their translation in their L1. (ii) Learners reflect on the presence or absence of a ‘fixed’ part among those L1 words (the affix); (iii) Learners find other words in their L1 sharing that fixed part and translate them into French; (iv) Learners exercise their knowledge of the affixes through the creation of new words based on the combination of a root, a relevant picture and the affix symbol (e.g., the globe icon symbolizing the French suffix -erie, which often indicates a place).

Throughout the lesson, learners worked in groups sharing the same L1, or another language when there was no more than one learner speaking the same L1. In steps 3 and 5 that involve PTL activities, the teacher guides the learners in their reflection on their L1 on the basis of the written and/or the oral forms of the L1 words as pronounced by the learners. Guidance is ensured by way of questions on the L1 as well as comments about what seems or sounds similar and what seems or sounds different in L1 and L2. These interactions provide an opportunity for the teacher to show interest in the learners’ L1.

Steps 1-5 lasted on average 90 minutes, which corresponds to the usual length of a lesson.

2.2.2. Questionnaires

Two questionnaires were developed to assess teachers’ and learners’ attitudes on the PTL lesson as well as learners’ emotions. The teachers’ questionnaire was translated in 3 languages (French, Greek, English) and learners’ questionnaire was translated in 14 languages (Albanian, Arabic, Chinese, English, Farsi, French, German, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, Tigrinya, and Turkish, see Appendix for the English versions of the questionnaires).

Questionnaires were filled in at the end of the lesson and took on average 5 minutes (teachers) and 20 minutes (learners) respectively. Teacher’s questionnaire. The questionnaire contains 11 closed questions on a 5-points Likert scale about the PTL lesson. Questions were grouped into 5 indexes: 2 indexes about their own experience, namely ease to teach (‘Teaching the root was simple’ and ‘Teaching the affix was simple’) and pleasure to teach (‘I enjoyed guiding the learners into reflecting on their native language and comparing it with the target language’), and 3 indexes about their assumptions regarding their students’ experience, namely ease to learn (‘The learners generally understood the instructions’, ‘The learners managed to reflect on the roots and compare them with their native language’, ‘The learners managed to reflect on the affixes and compare them with their native language’), pleasure to learn (‘Reflecting about the learners’ native languages positively affected the group dynamics’, ‘The learners enjoyed comparing their native language with the target language’), and learning benefits (‘The translanguaging techniques facilitated the understanding/learning the roots’, ‘The translanguaging techniques facilitated the understanding/learning the affixes’). Teachers were also asked to rate whether they felt sufficiently prepared for the lesson (‘I received sufficient training to implement a PTL lesson’), and an open section at the end of the questionnaire allowed them to provide additional comments.

Learner’s questionnaire. The questionnaire contains 4 categories of questions. The first category contains 11 background questions on the home country, host country, number of years spent in the host country, two questions about migration status, native language, multilingualism, years of education and SES. The second category of questions are about the mastery of the host language: proficiency level, number of course hours attended, opportunities to practice the language outside the classroom, familiarity with translanguaging techniques. The third category of questions concern attitudes about the translanguaging activities employed in the lesson they attended. These questions were assigned to 3 indexes, namely ease to learn, (‘It was easy to work on my native language with my classmates’ and ‘It was confusing to work on my native language and the taught language at the same time’), pleasure to learn (‘I felt tense when comparing the taught language with my native language’ and ‘I enjoyed reflecting on my native language’) and learning benefits (‘Relating the taught language to my native language helped me understand the course material better’ and ‘Relating the taught language to my native language will help me remember the course material better’). One additional question concerned the perceived closeness of L2 to L1 (‘My native language is closer to the taught language than I thought’). The fourth category of questions refers to emotions, which were assessed by asking participants to rate comparatively the strength of the emotions they have experienced during the PTL lesson they just attended to the emotions they typically feel in a “more traditional” lesson in which they do not reflect on their native language. A total of 13 emotions were tested including both positive and negative emotions, and both epistemic emotions (surprise, curiosity, excitement, confusion, frustration) and a subset of achievement emotions (hope, pride, enjoyment, despair, anger, shame) from the Achievement Emotions Questionnaire AEQ-S [

59]. Anxiety and boredom, which are considered both epistemic and achievement emotions, were also assessed. Responses to questions of categories 3 and 4 were given on a 5-points Likert scale (1 = ‘Not at all’; 5 = ‘Very strong’).

2.2.3. Teachers’ Training

Teachers attended a 90-minutes training session, either on site or remotely. The purpose of this session was to familiarize them with the theoretical framework of the study and the lesson’s materials and protocol, and to answer their questions. These sessions also provided an opportunity to adjust the construction of the pedagogical material based on their feedback. At the end of the training, teachers received an “example” video containing excerpts from pilot classes conducted by one of the authors in Switzerland and in Greece as well as the detailed protocol of the lesson.

2.2.4. Data Analyses

Nominal responses from both teachers’ and learners’ questionnaires were recoded into ordinal data and questions with a negative valence (e.g., ‘I felt tense when comparing the taught language with my native language’) were recoded inversely (5 becomes 1 etc.). No participants had missing data for over 50% of the questions. Therefore, no participants were removed based on missing data. Based on inspection of the data, no participants systematically misinterpreted any questions and had to be removed for this reason.

The overall feasibility of the method was assessed through 5 indexes from the teachers’ questionnaire (ease to teach, pleasure to teach, ease to learn, pleasure to learn, learning benefits) and 3 indexes from the learners’ questionnaire (ease to learn, pleasure to learn, learning benefits). Indexes’ scores were calculated by averaging scores to questions underlying them. When an answer to one of the questions was missing, the score to the other question(s) was taken to calculate the index. No participants failed to respond to both component questions of any of the indexes. Teachers’ indexes were analyzed using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test to assess whether those with a non-professional background in L2 teaching differ from professional teachers, while Wilcoxon signed-ranked tests were run with continuity correction to examine whether the indexes varied for root and affixes’ teaching. Learners’ data were first analyzed through Spearman correlations between the three indexes and individual demographic variables (age, years in the host country, multilingualism, years of education, SES) as well as variables related to the L2 (proficiency level in the target language, number of course hours completed, frequency of L2 language practice, and perceived similarity between L1 and L2). Multiple linear regression models were then conducted to evaluate predictive relationships between the indexes and the variables they showed correlations with. Multicollinearity was checked using the vif function in R. Residuals were approximately normally distributed for each model.

Learners’ emotions were analyzed to assess our 2 main hypotheses regarding the impact of the teaching method on emotions (PTL vs. standard) and regarding the impact of migration (forced vs. voluntary) on emotions. A first set of linear mixed effects models were run to test the effect of emotions and their sensitivity to the pedagogical method. A model was first run on the entire dataset with method and emotion valence (positive vs. negative) as fixed effects, and participant as random effect. Models were then conducted to assess the impact of the method on each individual emotion, using linear mixed effects regression models with method as a fixed effect and participant as a random effect on each emotion’s rating.

A second set of analyses were conducted to assess the impact of migration type on the evaluation of the PTL lesson and on their emotions. Two-factor between-subjects analyses of variance (ANOVA) were run with migration status as between subject factor on the three indexes: ease of learning, pleasure of learning and learning benefit. A first linear mixed effects regression model was run to test the hypothesis that forced migrants have overall stronger emotions than voluntary migrants, using emotion ratings in the entire dataset with emotion valence and migration status as fixed effects, and participant as a random effect. To assess the hypothesis that forced migrants get higher benefits from the PTL lesson than voluntary migrants, linear mixed effects regression models were conducted for each emotion, with method and migration status as fixed effects, and participant as random effect. Complementary analyses were conducted to assess whether migration status differently affects emotion type (epistemic vs. achievement emotions). Linear mixed effects regression models were conducted separately for positive and negative emotions, with emotion type and migration status as fixed effects, and participant as random effect. All interactions were resolved with the Tukey correction.

All analyses were conducted in R (R Core Team, 2012). Linear mixed effects regression models were conducted with the lme4 package.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Overall Feasibility of the Method

The overall means of the major indexes from teachers’ and learners’ questionnaires are reported in

Table 1. Teachers’ scores indicate a positive evaluation of the protocol. Moreover, none of the indexes were affected by the teachers’ professional background (ease to teach: H(1) = 1.226, p = 0.268; pleasure to teach: H(1) = 0.466, p = 0.495; ease to learn: H(1) = 1.226, p = 0.268; pleasure to learn: H(1) = 0.749, p = 0.784; learning benefits: H(1) = 1.321, p = 0.250). Teachers overall considered that they received sufficient training, with a mean of 4.71, where 5 corresponds to ‘strongly agree’, and teachers with no professional background did not differ from professionals (H(1) = 0.294, p = 0.587). Teachers did not find it harder to teach affixes than roots (V = 3, p = 0.233) and they did not think that learners struggled more with affixes than with roots (V = 7, p = 0.484).

Learners’ responses also demonstrate a positive evaluation of the protocol, even though their scores are lower than those obtained from the teachers. Spearman correlations between each of the indexes and individual variables susceptible to affect them (age, multilingualism, years of education, SES, years in the host country, L2 proficiency level, number of course hours completed, frequency of L2 practice, perceived similarity between L1 and L2) revealed a significant positive correlation of ease of learning with age (r(119) = 0.200, p = 0.029) and perceived language similarity (r(139) = 0.170, p = 0.046), a negative correlation with frequency of language practice (r(135) = -0.193, p = 0.025) and SES (r(132) = -0.175, p = 0.045), and a marginal negative correlation with multilingualism (r(139) = -0.161, p = 0.058). Pleasure of learning correlated negatively with SES (r(132) = -0.209, p = 0.017) and marginally with multilingualism (r(139) = -0.163, p = 0.055) and frequency of L2 practice (r(135) = -0.150, p = 0.082). Learning benefit showed a positive relationship with perceived language similarity (r(139) = 0.285, p < 0.001).

Three multiple linear regression models were used to evaluate predictive relationships between each of the learning indexes and the variables they correlate with. The model on ease of learning was significant (F(4, 106) = 4.616, p = 0.002, R2 = 0.148), and revealed SES (t = -2.437, p = 0.017) and L2 practice (t = -2.099, p = 0.038) as significant negative predictors, and perceived language similarity (t = 2.359, p = 0.020) as a significant positive predictor. The model on pleasure of learning was also significant (F(2, 129) = 5.228, p = 0.07, R2 = 0.075), revealing SES as a marginal negative predictor (t = -1.859, p = 0.065) and L2 practice as a significant negative predictor (t = -2.478, p = 0.015). The model on learning benefit was also significant (F(1, 137) = 15.92, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.104), and showed perceived language similarity as a significant positive predictor (t = 3.99, p < 0.001). A summary of the significant predictors is provided in

Table 2.

3.2. Analysis of Learners’ Emotions

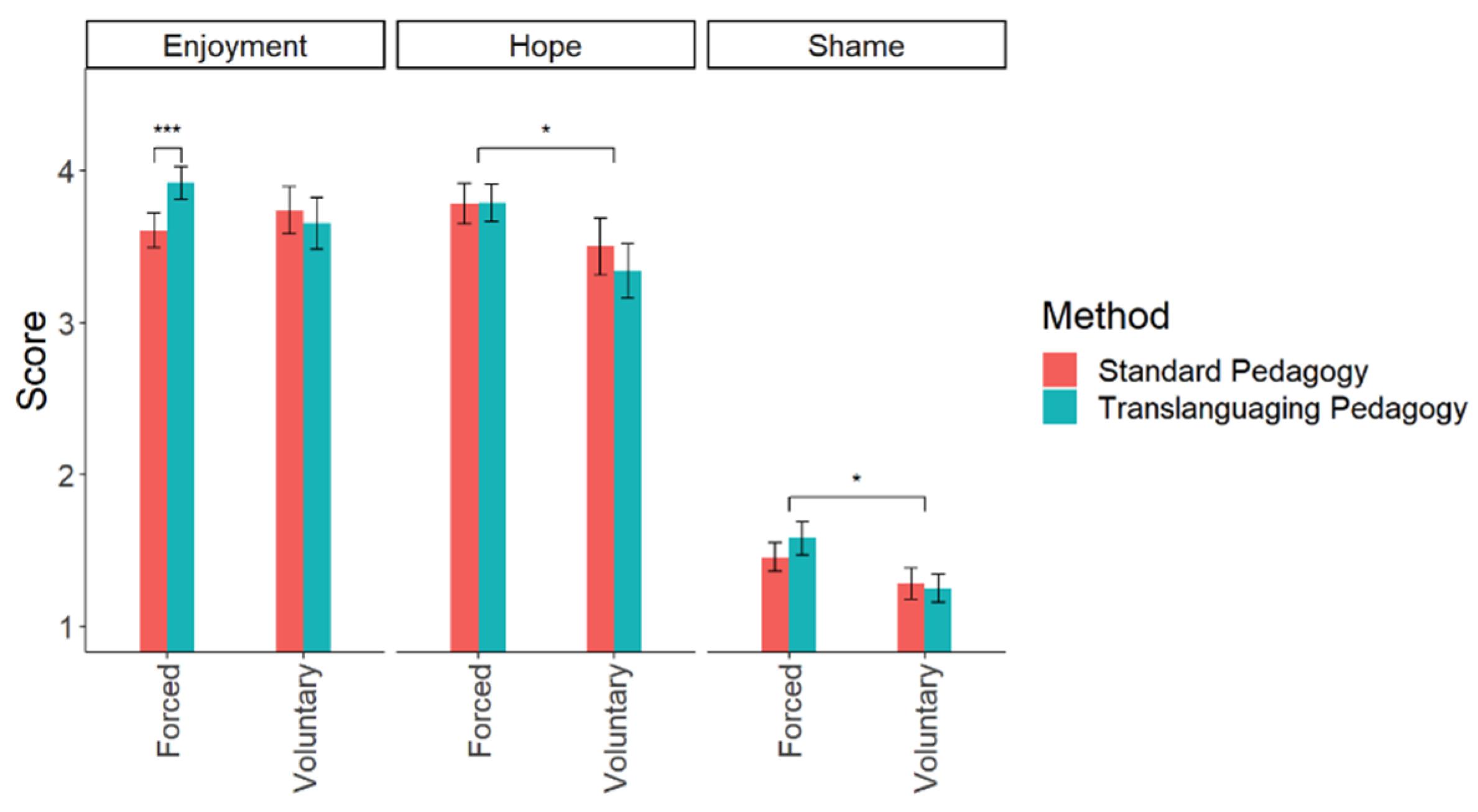

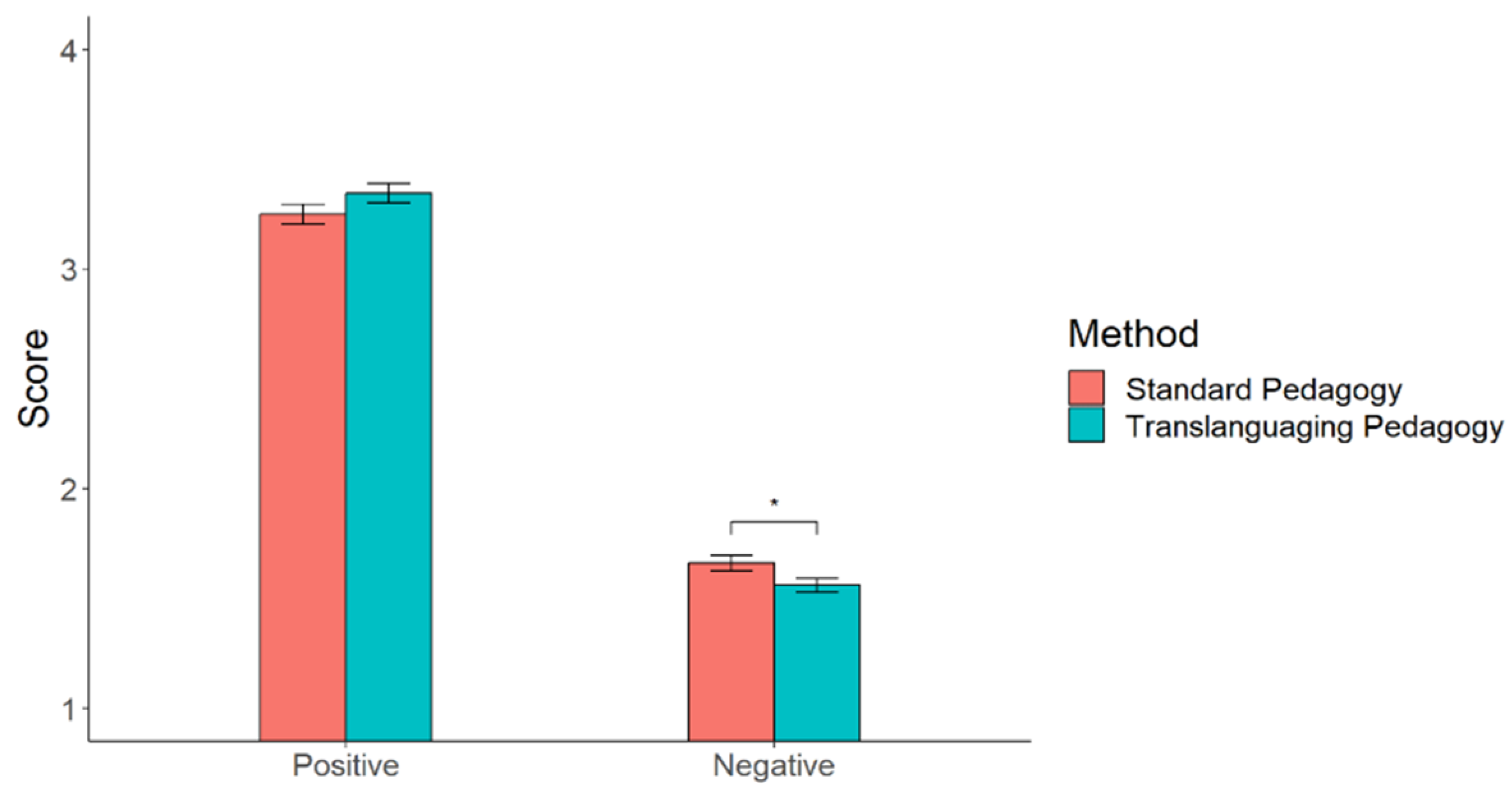

A first model was run on emotional ratings in the entire dataset with emotion valence (positive vs. negative) and pedagogical method (standard vs. PTL) as fixed effects and participant as a random effect. Results showed a significant main effect of emotion valence (F(1, 3196) = 2371, p < 0.001) with higher ratings for positive than negative emotions, and a significant valence x method interaction (F(1, 3196) = 8.172, p = 0.004) as illustrated in

Figure 1. Resolving the interaction with the Tukey correction applied revealed lower ratings for PTL than the standard pedagogy for negative emotions (z = 2.424, p = 0.015), and no significant difference between the two approaches for positive emotions (z = -1.623, p = 0.105).

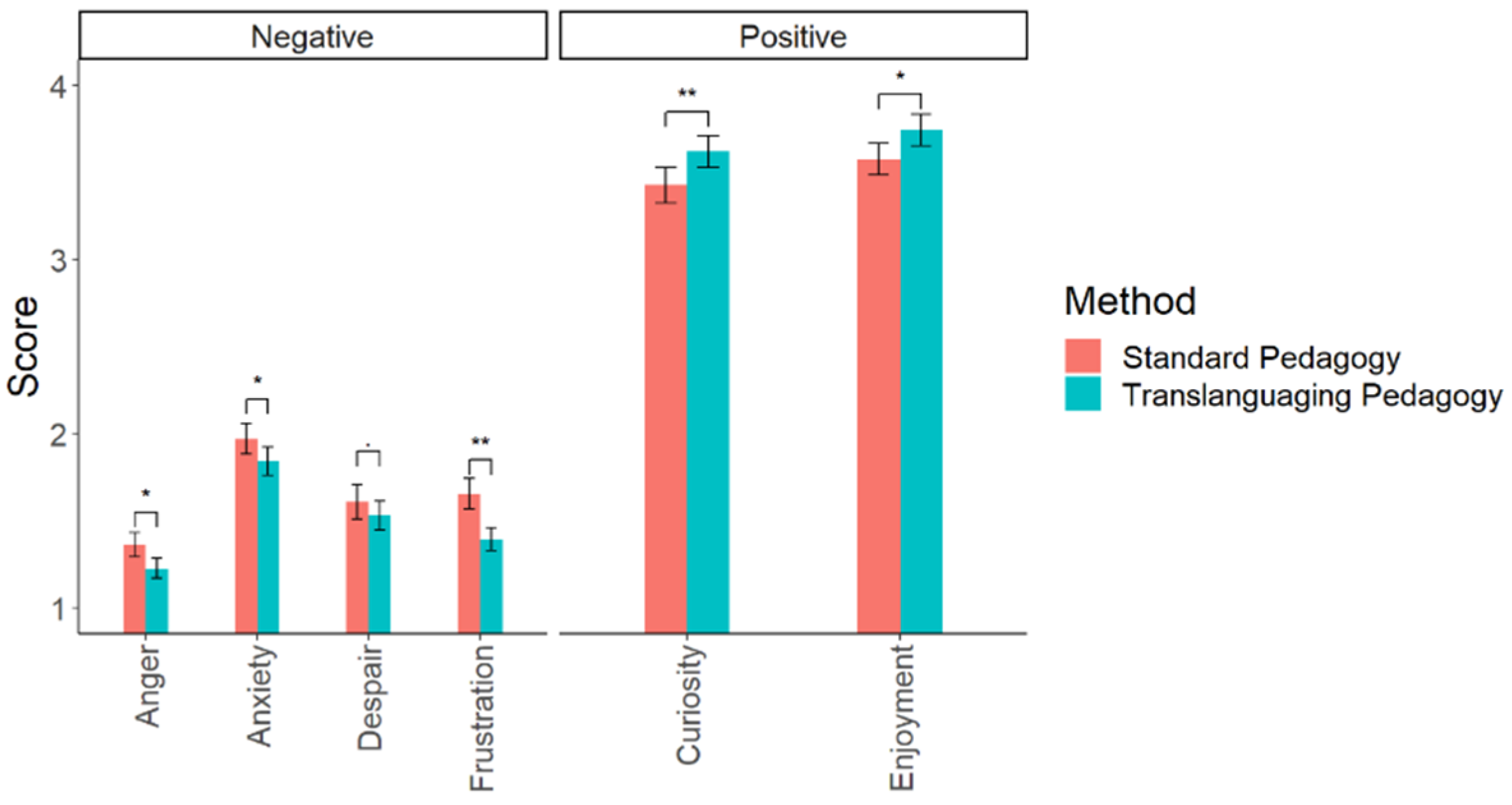

Linear mixed effects regression models were then run on each emotion with pedagogical approach as a fixed effect and participant as a random effect. Results revealed lower ratings for PTL than the standard pedagogy for anger (F(1,120) = 6.817, p = 0.010), frustration (F(1,121) = 11.821, p < 0.001) and anxiety (F(1,126) = 4.431, p = 0.037) and a marginal effect in the same direction for despair (F(1, 122) = 3.636, P = 0.059), and higher ratings for PTL than the standard pedagogy for enjoyment (F(1, 120) = 5.923, p = 0.016) and curiosity (F(1,117) = 9.529, p = 0.003). A summary of the emotions showing significant sensitivity to pedagogy is illustrated in

Figure 2.

3.3. Analysis of the Role of Migration Status

Three two-factor between-subjects analyses of variance (ANOVA) were run with migration status (forced vs. voluntary) as between subject factor on the three indexes: ease of learning, pleasure of learning and learning benefit, respectively. Results showed a higher index of overall pleasure to learn for voluntary than for forced migrants (F(1, 7.10) = 9.008, p = 0.003) and a trend toward higher ease to learn for voluntary than forced migrants (F(1, 2.23) = 2.877, p = 0.09). Linear mixed effects regression models were run on each emotion with pedagogical method and migration status as fixed effects and participant as a random effect on ratings for a given emotion. Results on enjoyment revealed a marginal effect of pedagogical method (F(1,106) = 2.931, p = 0.090) and a significant interaction (F(1, 106) = 4.053, p = 0.047). Resolving the interaction with the Tukey correction showed higher enjoyment ratings in PTL than in standard pedagogy for forced migrants (t = -2.972, p = 0.004) and no difference between the two methods in voluntary migrants (t = 0.193, p = 0.847). Hope and shame revealed a main effect of migration status, with higher ratings in forced than in voluntary migrants (F(1,120) = 4.884, p = 0.029 and F(1,118) = 4.510, p = 0.036 respectively). Pride revealed a trend for higher ratings by forced than by voluntary migrants (F(1, 123) = 3.389, p = 0.068).

Figure 3.

Mean ratings of learners’ emotions that showed a significant effect of migration status, and their sensitivity to pedagogy.

Figure 3.

Mean ratings of learners’ emotions that showed a significant effect of migration status, and their sensitivity to pedagogy.

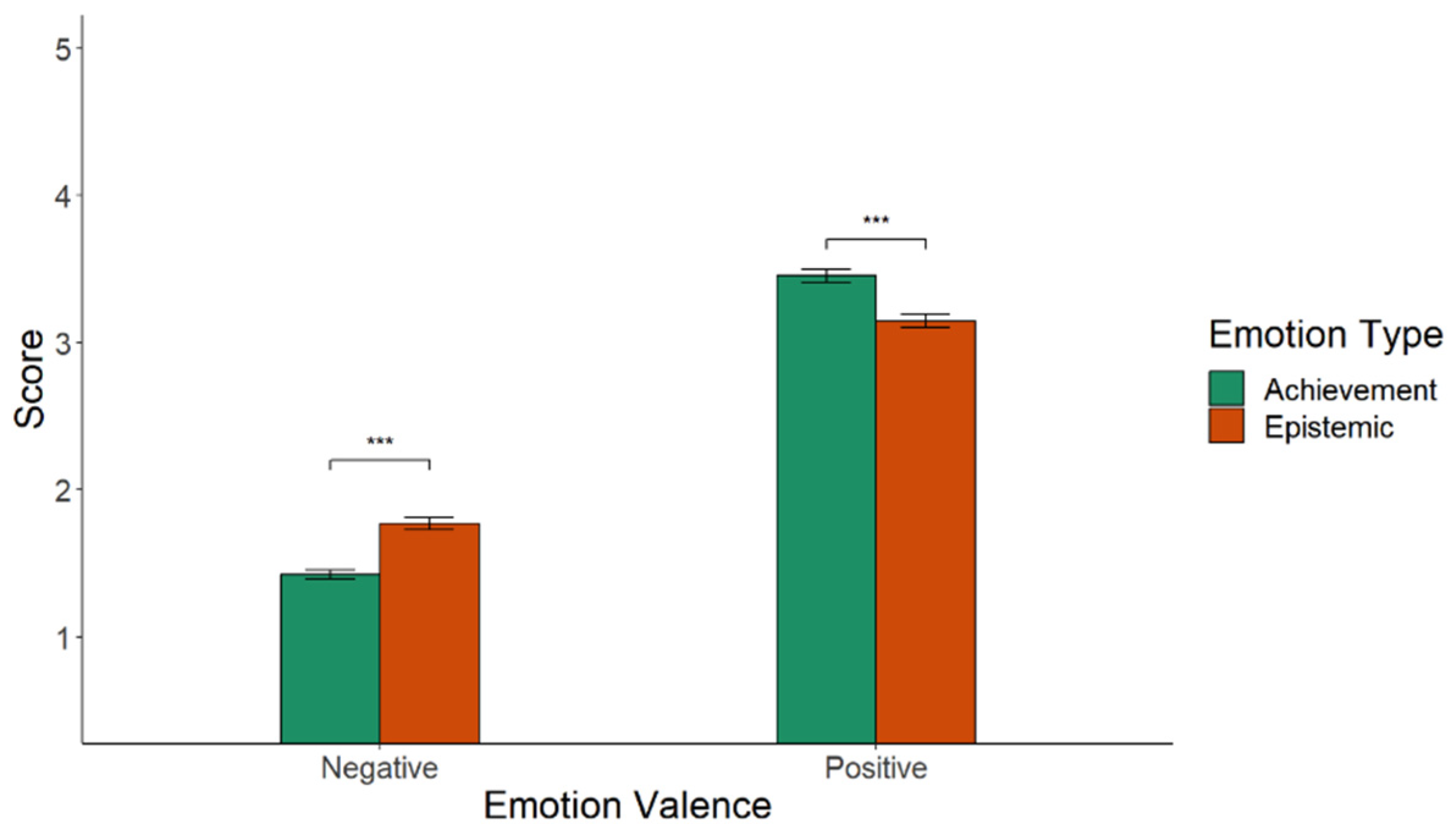

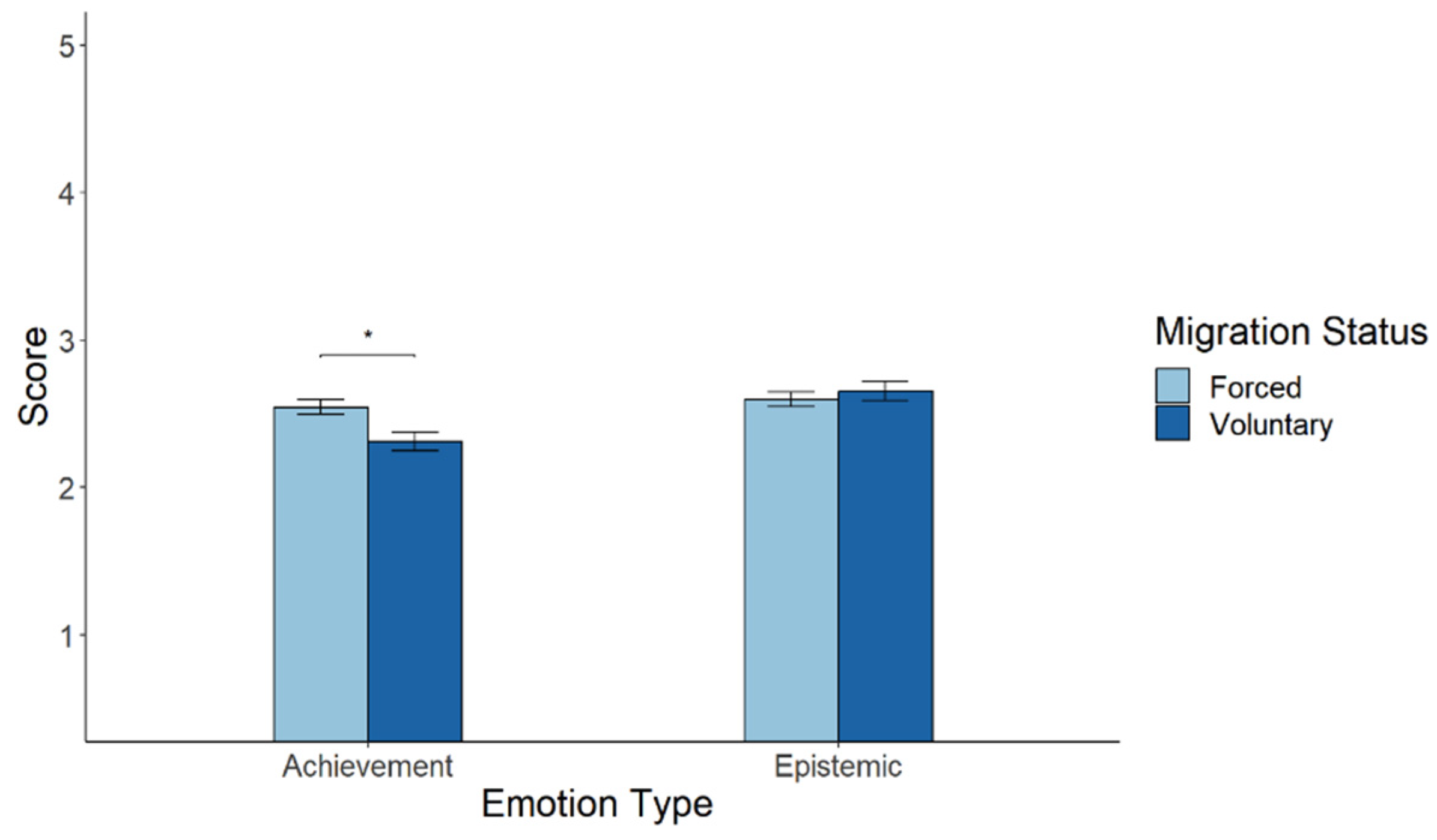

Complementary analyses were conducted to explore the impact of migration status on achievement and epistemic emotions. A linear mixed effects regression model was run with emotion type (epistemic vs. achievement), migration status and emotion valence as fixed effects, and participant as a random effect. Results showed a main effect of valence with higher ratings for positive than negative emotions (F(1, 2409) = 1811.099, p < 0.001) and a valence x emotion type interaction (F(1, 2408.60) = 62.358, p < 0.001, see

Figure 4). Resolving that interaction with the Tukey correction showed higher achievement than epistemic positive emotions (t = 4.860, p < 0.001), and lower achievement than epistemic negative emotions (t = -6.249, p < 0.001).

The model also revealed a migration status x emotion type interaction (F(2, 2410.27) = 11.825, p < 0.001), illustrated in

Figure 5. Resolving that interaction with the Tukey correction showed higher achievement emotions for forced than voluntary migrants (t = 2.585, p = 0.011), but no difference between the two groups for epistemic emotions (t = -0.151, p = 0.880).

4. Discussion

This study presents a novel pedagogical translanguaging tool to teach derivational morphology to migrants and the evaluation of this tool, through questionnaires, by 141 L2 learners and 13 language teachers involved in 23 90-minutes pilot lessons given in Switzerland, Greece, and France. Three major lines of results were obtained regarding the overall feasibility of the tool, learners’ emotions in the classroom, and the impact of forced migration on both the feasibility of the tool and learners’ emotions. These three lines are discussed in turns.

4.1. Overall Feasibility of PTL in Adult Migrants’ Classroom

Both teachers and learners showed highly positive attitudes towards the PTL tool. Teachers rated their pleasure at near ceiling on the scale (4.8 on a 5-point scale), followed closely by ease to teach. When asked to evaluate their students’ ease of learning, pleasure of learning and learning benefits of the tool, teachers rated all three above 4, showing their confidence that the tool was well-appreciated by their students. Teachers did not find it more difficult to teach affixes than roots, despite their higher level of abstraction, and they considered that the learning benefits in using the translanguaging tool was equally beneficial in the teaching of affixes and roots. This finding is important since the teaching of affixes is often considered difficult by educators and educational materials rarely focus on the systematic teaching of affixes [

60]. Teachers all considered that the 90-minutes training they received was sufficient to grasp and implement the pedagogical tool, and none of the indexes showed sensitivity to teachers’ professional background. This shows that non-professional L2 teachers with no background in linguistics or language teaching did not struggle more than professionals when guiding learners in the comparison between their native languages and the taught language. Moreover, for the most part, teachers did not speak the languages of the learners, and most of the learners had a very low L2 level (A1 or below). Hence, these specificities of migrants’ L2 classrooms do not appear to constitute obstacles for teachers to the use of PTL tools, even in the teaching of rather complex structural properties of words.

Teachers were also given the opportunity to comment on their experience through qualitative feedback. Analysis of their comments also highlights teachers’ overall high degree of satisfaction (e.g., “The dynamics were excellent. You made it possible for me to spend a good evening with the group”; “I found it very interesting, like the students”; “ Thank you so much for giving me the privilege to participate in this experience”), their interest in learning more about PTL (e.g., “I hope to receive further education and material on this approach (pedagogical translanguaging)”, and their intention to using it in their regular classes (e.g., “I like the tool, I still have to think about how to use it in my own classes but I will use it”; “I find the worksheets very good and very useful, an example to follow for my next lessons”). It therefore appears that the PTL tool triggered teachers’ enthusiasm, a feature that is crucial to the adoption of success-related values and associated emotions [

61].

Learners also showed overall high rates on the 3 attitude indexes: the highest score was obtained for their evaluation of the learning benefits of the tool, above their pleasure to learn and ease of learning. Regarding the influence of individual factors on these indexes, a single factor appeared to positively influence both learners’ ease to learn and their evaluation of the potential learning benefits of PTL: their perception of how similar their native language is to the taught language. Learners rated the lesson as overall easier and more beneficial when they felt that the two languages were close. This finding, based on subjective evaluations, is in line with the hypothesis that the cognitive mechanism underlying L2 learning is analogy: when L2 is compared to L1 and the similarities between the two languages are explicitly revealed, learners can more easily anchor new knowledge into existing one through analogical reasoning [

32,

37].

Learners’ ease to engage in translanguaging activities was not affected by their level of formal education, which goes against the claim that metalinguistic reasoning is difficult for learners with low levels of education [

62,

63]. Yet, it is in line with recent research reports showing that reflection on crosslinguistic correspondences is not only feasible but also beneficial to children as young as 8 years old. It has been shown that such practices enhance children’s L2 (English) vocabulary [

15] but also more specifically that they improve children’s morphological awareness both in L1 and in L2 , their reading comprehension [

64] as well as their sensitivity to ungrammaticality in the L2 [

65]. Along the same lines, learners’ proficiency level in L2 did not influence their ease to engage in PTL practices either. This suggests that the tool can be implemented from the beginning proficiency levels as a scaffolding in L2 learning, and that PTL techniques that explicitly draw on systematic comparisons of learners’ languages are suitable even for beginners (see [

66], for the successful integration of metalinguistic awareness practices for beginners).

Ease to learn and pleasure to learn were both unexpectedly negatively influenced by SES and L2 practice. Learners with higher SES found the tool less pleasurable and more difficult to use than learners with lower SES. We speculate that the negative effect of SES may reflect different expectations of L2 learners with higher education, who may grant higher importance in maximizing the L2 input in the classroom, because this is the kind of teaching practice they have been used to at school and/or because this is what is often claimed to be the right way to teach [

7,

9]. The finding that learners who have fewer opportunities to practice the L2 in everyday life find it easier and more pleasurable to engage in PTL activities shows that such activities may be of particular interest for learners with few opportunities to practice the taught language, as is often the case of forced migrants.

Exploration of the impact of migration type on learners’ attitudes about PTL showed that forced migrants had a lower index of pleasure to learn and a trend toward lower ease to learn compared to voluntary migrants. Although forced migrants in our sample showed significantly lower levels of education than voluntary migrants, analyses showed that this variable did not influence the two indexes. We explored the possibility that the differences found between the two groups be due to differences in their perception of the similarity between the L2 and their native languages. However, no such difference was found between the groups on that variable. Finer exploration of the data revealed that the lower pleasure observed in forced migrants actually lied in learners tested in Greece: forced migrants tested in Greece enjoyed less reflecting on their native language and felt more tense to do so than voluntary migrants, while no such difference was found in learners tested in Switzerland. Further investigation is needed to understand the lower pleasure to learn found in Greece.

4.2. Learners’ Emotions in the Language Classroom

Results show that overall, migrant learners experience more positive emotions than negative emotions in the language classroom, in line with recent data obtained with a similar methodology on students following foreign language teaching lessons in their own country [

51].

Comparison between learners’ emotions in the PTL classroom and in their usual classroom showed overall no difference between the two settings for positive emotions, but a significant reduction of negative emotions in the PTL classroom. Finer analysis of the effect of pedagogy on individual emotions showed that enjoyment and curiosity were significantly higher in the PTL than the usual classroom, whereas anger, frustration and to some extent despair (trend) were lower. Anxiety was also rated significantly lower in the PTL setting. These results align and extend to a new population of L2 learners, with fine subjective measures, previous studies that reported benefits from PTL on learners’ well-being (Busse et al., 2019; [

12,

14] [

16,

17,

56]. The control-value theory of emotions identifies two cognitive appraisals of emotions: learners’ perceptions of control and value [

47]. Control refers to the learners’ perception of their ability to produce the actions necessary for task success, indicating how capable the individual feels of accomplishing the learning. Value pertains to the importance attached to the task. High levels of perceived control and value over the learning activities are assumed to evoke positive emotional experiences while low levels of control are expected to elicit negative emotions. By its essence, PTL sets learners at the heart of their learning process, and therefore in the position of controlling it: in migrants’ classrooms where teachers do not speak their native languages, learners are actively engaged in reflecting on the similarities between languages, and share the output of their own insights with teachers who act as guides, rather than main source of knowledge and information. This peculiar relation between learners and their teacher puts the learners in the position of the one who has the knowledge, which it can convey to the teacher, which not only sets learners in a control position, but which also grants a special value to their native language, and probably to the L2 learning task itself. The present study only assessed emotions, and not their appraisals. However, recent research has validated the major tenets of the control-value theory in a group of foreign language learners [

51], and preliminary evidence from our own laboratory on a wide sample of migrants suggests that not only control and value play a key role in emotions, but that both these appraisals and emotions significantly benefit from the use of PTL tools in the classroom (Franck, Papadopoulou & Audrin, in prep.).

Results showed that forced migrants like voluntary migrants experience overall higher positive than negative emotions, and that the intensity of emotions does not differ across the two groups. Nevertheless, a finer approach to individual emotions suggests differences between forced and voluntary migrants. Forced migrants showed higher hope and shame than voluntary migrants. L2 courses may be regarded by forced migrants as a window to the society and the culture of the host country, particularly since they are in the process of getting integrated in the host country: they usually are unemployed, do not have a permanent shelter and have no or very few contacts with the locals. L2 courses constitute the first and very important step of their integration and may give forced migrants hope for the possibility of a new beginning. At the same time, shame is more intense in forced than in voluntary migrants. Shame refers to a self-conscious feeling that entails reflection and evaluation of the self [

67]. This negative emotion is usually characterized by a sense of worthlessness, and is often accompanied by negative self-evaluation, enthusiasm to quit, and a sense of distrust, helplessness, and insignificance. Interestingly, shame has also been argued to arise from fear [

68]. Hence, it is plausible that the stressors encountered in the host country contribute to trigger the feeling of shame [69] The higher feeling of shame in the L2 classroom reported in the present study may thus reflect a more general feeling that forced migrants experience in the host countries, and not a specific emotion experienced only in the language courses, as they are aware that the host countries and communities often look upon them with skepticism and suspicion and conceive them as a complication rather than as enrichment of the society.

Forced migrants also differed from voluntary migrants in that they reported feeling significantly higher enjoyment in the PTL lesson than in their usual language classroom, a difference that was not found in voluntary migrants. This result suggests that the lower indexes of pleasure and ease to engage in specific translanguaging activities discussed in the previous section cannot be attributed to forced migrants’ emotional stance regarding the PTL lesson. Forced migrants did not leave their country by their own will and hence they may be missing their country, families, friends etc. PTL activities represent a unique opportunity for them to reflect on their own language and, by extension, on their own country and everything they left behind, a task in which they appear to take particular pleasure.

To our knowledge, achievement and epistemic emotions have not been examined conjointly in previous research. Exploratory analyses of the current data set shows an interesting interaction between valence and emotion type: while positive achievement emotions (hope, pride and enjoyment) were rated higher than positive epistemic emotions (surprise, curiosity, excitement), negative achievement emotions (despair, anger, shame) were rated lower than negative epistemic emotions (confusion, frustration). This suggests that in the L2 classroom, the most salient positive emotions are those experienced in relation to the learning accomplishments, i.e., achievement emotions, whereas the most salient negative emotions are those related to the cognitive processes involved in learning, i.e., epistemic emotions. Moreover, our data suggest that forced migrants differ from voluntary migrants in showing higher achievement emotions altogether. Forced migrants may grant stronger value and have a stronger intrinsic motivation to succeed in language learning because it is closely tied to their immediate needs for survival and integration. This heightened value and motivation can lead to more intense achievement emotions, both positive and negative [

48].

5. Conclusions

The study shows that both teachers and learners experienced pedagogical translanguaging practices as a relevant language learning tool that is easy to apply, generates pleasure in teaching as well as in learning, and is susceptible to bring learning benefits. Importantly, the fact that teachers do not master the learners’ native languages or that they do not necessarily have a professional background in second language teaching and linguistics is not an obstacle to guide learners in their reflection on comparing the second to their first language. Moreover, although forced migrants showed overall lower indexes of pleasure to learn and ease to learn than voluntary migrants, level of education did not impact the subjective ease to engage into metalinguistic reasoning, suggesting that a low level of education, which often characterizes forced migrants, does not exclude the use of PTL pedagogies. Additionally, bringing the learners’ languages in the classroom appears as a relevant tool to overall reduce negative emotions, more particularly anger, frustration, anxiety, and despair, and enhance positive emotions, more particularly enjoyment and curiosity. Besides, forced migrants reported higher enjoyment with the PTL approach compared to the standard classroom, which supports its socio-emotional benefits for migrant education. The study also highlighted that forced migrants have higher achievement - but not epistemic - emotions than voluntary migrants, which further emphasizes the significant impact of positive achievement emotions such as hope, pride and enjoyment, on migrant language learning.

Although the current study brings encouraging results, given the key role emotions play in L2 learning, the assessment of the PTL tool is entirely based on subjective measures. Capitalizing on these preliminary results, future research now needs to establish the direct benefits of PTL practices on language learning, via an adequate evidence-based protocol.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to ethical reasons. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Aude Maldy, Coralie Bourquin, Laurane Perrin, Justine Wicky, Sofia Dagkopoulou and Olga Kritharidou for the contribution to materials construction and data collection, and David György for his contribution to data analyses. We are grateful to all the teachers and learners who took part in the study and provided us with insightful comments at various steps of this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Beacco, J., Krumm, H., Little, D., & Thalgott, P. (2017b). The Linguistic integration of adult migrants / L’intégration linguistique des migrants adultes: Some Lessons from Research / Les Enseignements de la Recherche. De Gruyter Mouton.

- Rocca, L., Carlsen, C. H., & Deygers, B. (2020). Linguistic integration of adult migrants: requirements and learning opportunitie: Council of Europe.

- Rubio-Marín, R. (2014). Human rights and immigration: OUP Oxford.

- García, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Language, languaging and bilingualism. Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education, 5-18.

- Celic, C. M., & Seltzer, K. (2013). Translanguaging : A CUNY-NYSIEB Guide for Educators: Cuny-Nysieb New York.

- Kirsch, C. (2020). Opening minds to translanguaging pedagogies. System, 92, 102271.

- Olioumtsevits, K., Franck, J., & Papadopoulou, D. (2024). Breaking the Language Barrier: Why Embracing Native Languages in Second/Foreign Language Teaching is Key. In T. Books (Ed.), In Myths and Facts about Multilingualism. Calec Editions, New York, USA. [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J. (1980). The cross-lingual dimensions of language proficiency: Implications for bilingual education and the optimal age issue. TESOL quarterly, 175-187. [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J. (2019). The emergence of translanguaging pedagogy: A dialogue between theory and practice. Journal of Multilingual Education Research, 9(13), 19-36.

- García, O. (2011). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective: John Wiley & Sons.

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2017). Minority languages and sustainable translanguaging: Threat or opportunity? Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural development, 38(10), 901-912.

- Hopp, H., Kieseier, T., Jakisch, J., Sturm, S., & Thoma, D. (2021). Do minority-language and majority-language students benefit from pedagogical translanguaging in early foreign language development? Multilingua, 40(6), 815-837.

- Leonet, O., Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2020). Developing morphological awareness across languages: Translanguaging pedagogies in third language acquisition. Language awareness, 29(1), 41-59. [CrossRef]

- Capstick, T., & Delaney, M. (2016). Language for resilience: The role of language in enhancing the resilience of Syrian refugees and host communities.

- Busse, V., Cenoz, J., Dalmann, N., & Rogge, F. (2020). Addressing linguistic diversity in the language classroom in a resource-oriented way: An intervention study with primary school children. Language Learning, 70(2), 382-419. [CrossRef]

- Mammou, P., Maligkoudi, C., & Gogonas, N. (2023). Enhancing L2 learning in a class of unaccompanied minor refugee students through translanguaging pedagogy. International multilingual research journal, 17(2), 139-156. [CrossRef]

- Van Viegen, S. (2020). Translanguaging for and as Learning with Youth from Refugee Backgrounds. Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 3(1), 60-76.

- Giazitzidou, S., Mouzaki, A., & Padeliadu, S. (2024). Pathways from morphological awareness to reading fluency: the mediating role of phonological awareness and vocabulary. Reading and Writing, 37(5), 1109-1131. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, G., Walton, P., & Roberts, W. (2014). Morphological awareness and vocabulary development among kindergarteners with different ability levels. Journal of learning disabilities, 47(1), 54-64. [CrossRef]

- De Togni, L. (2023). Morphological Awareness and Vocabulary Acquisition. The contribution of Explicit Morphological Instruction in the acquisition of L2 vocabulary. International Journal of Multilingual Education(24), 37-52.

- Spaas, C., Verelst, A., Devlieger, I., Aalto, S., Andersen, A. J., Durbeej, N., Hilden, P. K., Kankaanpää, R., Primdahl, N. L., Opaas, M., Osman, F., Peltonen, K., Sarkadi, A., Skovdal, M., Jervelund, S. S., Soye, E., Watters, C., Derluyn, I., Colpin, H., & De Haene, L. (2022). Mental health of refugee and non-refugee migrant young people in European secondary education: The role of family separation, daily material stress and perceived discrimination in resettlement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(5), 848–870. [CrossRef]

- Rothman, J., & Slabakova, R. (2018). The generative approach to SLA and its place in modern second language studies. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 40(2), 417-442. [CrossRef]

- Eckman, F. R. (2017). Theoretical L2 phonology The Routledge handbook of contemporary English pronunciation (pp. 25-38): Routledge.

- Prévost, P. (2009). The acquisition of French: The Development of Inflectional Morphology and Syntax in L1 Acquisition, Bilingualism, and L2 Acquisition. John Benjamins Publishing.

- Marecka, M., Szewczyk, J., Otwinowska, A., Durlik, J., Foryś-Nogala, M., Kutyłowska, K., & Wodniecka, Z. (2021). False friends or real friends? False cognates show advantage in word form learning. Cognition, 206, 104477. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. B., & Mishler, A. (2012). Evidence for language transfer leading to a perceptual advantage for non-native listeners. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 132(4), 2700-2710. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentner, D. (1983). Structure-mapping: A theoretical framework for analogy. Cognitive Science, 7(2), 155-170. [CrossRef]

- Hofstadter, D. R. (1995). Fluid concepts and creative analogies: Computer models of the fundamental mechanisms of thought. Basic books.

- Holyoak, K. J., & Thagard, P. (1996). Mental leaps: Analogy in creative thought. MIT press.

- Sander, E., & Bianchini, F. (2013). The central role of analogy in cognitive science. Methode: Analytic Perspectives, 2, 21-26.

- Gentner, D., Loewenstein, J., & Thompson, L. (2003). Learning and transfer: A general role for analogical encoding. Journal of educational psychology, 95(2), 393. [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, K. J., Miao, C.-H., & Gentner, D. (2001). Learning by analogical bootstrapping. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 10(4), 417-446. [CrossRef]

- Ross, B. H. (1987). This is like that: The use of earlier problems and the separation of similarity effects. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 13(4), 629.

- Hofstadter, D. R., & Sander, E. (2013). Surfaces and essences: Analogy as the fuel and fire of thinking. Basic books.

- Loewenstein, J. (2017). Structure mapping and vocabularies for thinking. Topics in Cognitive Science, 9(3), 842-858. [CrossRef]

- Odlin, T. (1989). Language transfer (Vol. 27): Cambridge University Press.

- Gentner, D., & Markman, A. B. (1997). Structure mapping in analogy and similarity. American psychologist, 52(1), 45.

- Pessoa, L. (2009). How do emotion and motivation direct executive control? Trends Cognitive Sciences, 13(4), 160-166.

- Vuilleumier, P. (2005). How brains beware: neural mechanisms of emotional attention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(12), 585-5. [CrossRef]

- Kensinger, E. A., & Kark, S. M. (2018). Emotion and memory. Stevens’ handbook of experimental psychology and cognitive Neuroscience, 1, 1-26.

- Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition.

- Shao, K., Pekrun, R., & Nicholson, L. J. (2019). Emotions in classroom language learning: What can we learn from achievement emotion research? System, 86, 102121.

- Dewaele, J.-M., Witney, J., Saito, K., & Dewaele, L. (2018). Foreign language enjoyment and anxiety: The effect of teacher and learner variables. Language teaching research, 22(6), 676-697. [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z., Henry, A., & MacIntyre, P. D. (2014). Motivational dynamics in language learning (Vol. 81): Multilingual Matters.

- Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educational psychologist, 37(2), 91-105. [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational psychology review, 18, 315-341. [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., & Perry, R. P. (2014). Control-value theory of achievement emotions. In R. Pekrun & L. Linnenbrink-Garcia (Eds.), International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 130-151). Routledge.

- Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., Barchfeld, P., & Perry, R. P. (2011). Measuring emotions in students’ learning and performance: The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire (AEQ). Contemporary educational psychology, 36(1), 36-48. [CrossRef]

- Davari, H., Karami, H., Nourzadeh, S., & Iranmehr, A. (2022). Examining the validity of the Achievement Emotions Questionnaire for measuring more emotions in the foreign language classroom. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural development, 43(8), 701-714. [CrossRef]

- Shao, K., Pekrun, R., Marsh, H. W., & Loderer, K. (2020). Control-value appraisals, achievement emotions, and foreign language performance: A latent interaction analysis. Learning and Instruction, 69, 101356. [CrossRef]

- Shao, K., Stockinger, K., Marsh, H. W., & Pekrun, R. (2023). Applying control-value theory for examining multiple emotions in L2 classrooms: Validating the Achievement Emotions Questionnaire–Second Language Learning. Language teaching research, 13621688221144497. [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J. (2007). Rethinking monolingual instructional strategies in multilingual classrooms. Canadian journal of applied linguistics, 10(2), 221-240.

- Armon-Lotem, S., Meir, N., De Houwer, A., & Ortega, L. (2019). The nature of exposure and input in early bilingualism. In A. De Houwer & L. Ortega (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of bilingualism (pp. 193-212). Cambridge University Press.

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2021). Pedagogical translanguaging: Cambridge University Press.

- Simopoulos, G., Gatsi, G., Pathiaki, E., Karagianni, D., & Bouri, S. (2019). Ftou kai Vgaino! Toolkit of activities for multilingual and social emotional empowerment. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/greece/en/reports/ftou-kai-vgaino.

- Lyster, R., Quiroga, J., & Ballinger, S. (2013). The effects of biliteracy instruction on morphological awareness. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 1(2), 169-197. [CrossRef]

- James, P., Iyer, A., & Webb, T. L. (2019). The impact of post-migration stressors on refugees’ emotional distress and health: A longitudinal analysis. European journal of social psychology, 49(7), 1359-1367. [CrossRef]

- Bieleke, M., Gogol, K., Goetz, T., Daniels, L., & Pekrun, R. (2021). The AEQ-S: A short version of the Achievement Emotions Questionnaire. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 65, 101940. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Vega, B., & Mora-Pablo, I. (2023). English Derivational morphology: Challenges and Teaching Considerations for non-native speakers. Beyond Words, 11(1), 1-18.

- Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., Lüdtke, O., Pekrun, R., & Sutton, R. E. (2009). Emotional transmission in the classroom: exploring the relationship between teacher and student enjoyment. Journal of educational psychology, 101(3), 705. [CrossRef]

- Kurvers, J., van Hout, R., & Vallen, A. (2006). Discovering features of language: Metalinguistic awareness of adult illiterates. International Review of Education, 52(2), 159-176.

- Tarone, E. (2010). Second language acquisition by low-literate learners: An under-studied population. Language Teaching, 43(1), 75-83. [CrossRef]

- Lam, K., Chen, X., & Deacon, S. H. (2020). The role of awareness of cross-language suffix correspondences in second-language reading comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(1), 29-43. [CrossRef]

- Torregrossa, J., Eisenbeiß, S., & Bongartz, C. (2023). Boosting bilingual metalinguistic awareness under dual language activation: Some implications for bilingual education. Language Learning, 73(3), 683-722. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalves, L. (2021). Development and demonstration of metalinguistic awareness in adult ESL learners with emergent literacy. Language awareness, 30(2), 134-151. [CrossRef]

- Kang, C., & Wu, J. (2022). A theoretical review on the role of positive emotional classroom rapport in preventing EFL students’ shame: A control-value theory perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. L. (2002). Shame and guilt Guilford Press. New York, NY.

- Ķešāne, I. (2019). The lived experience of inequality and migration: Emotions and meaning making among Latvian emigrants. Emotion, Space and Society, 33, 100597.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).