Submitted:

07 September 2024

Posted:

09 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Results

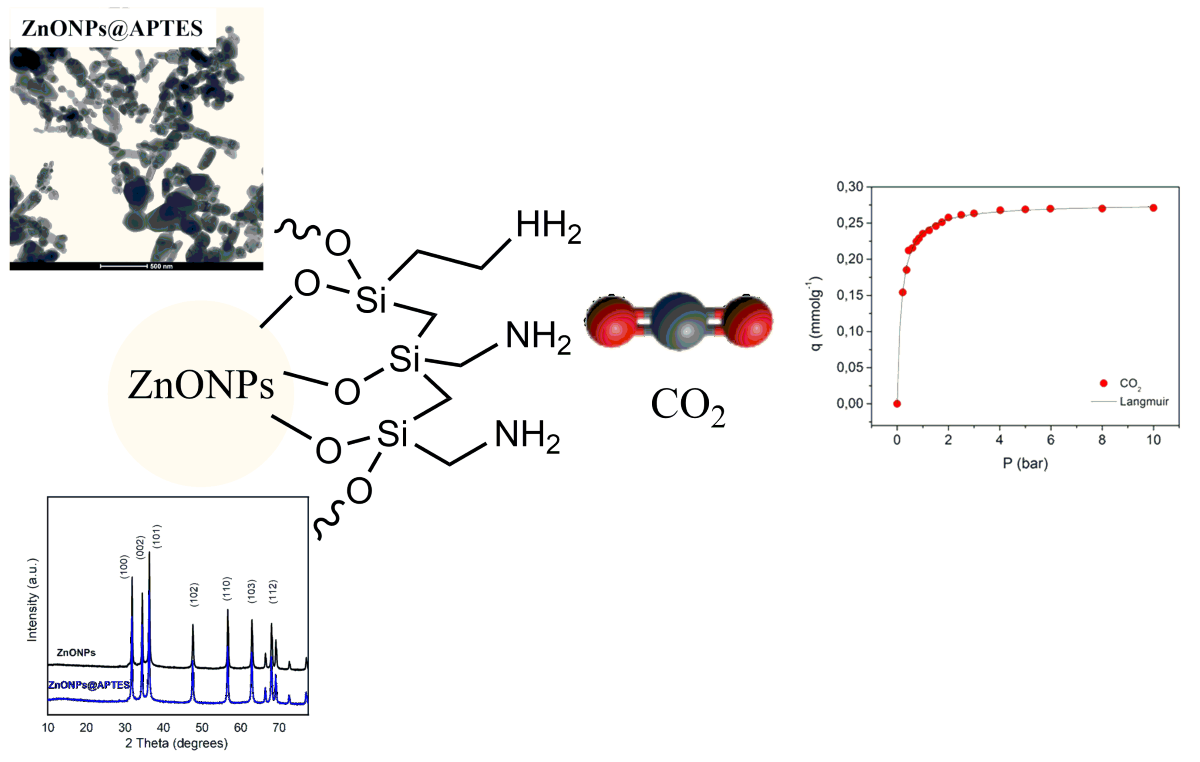

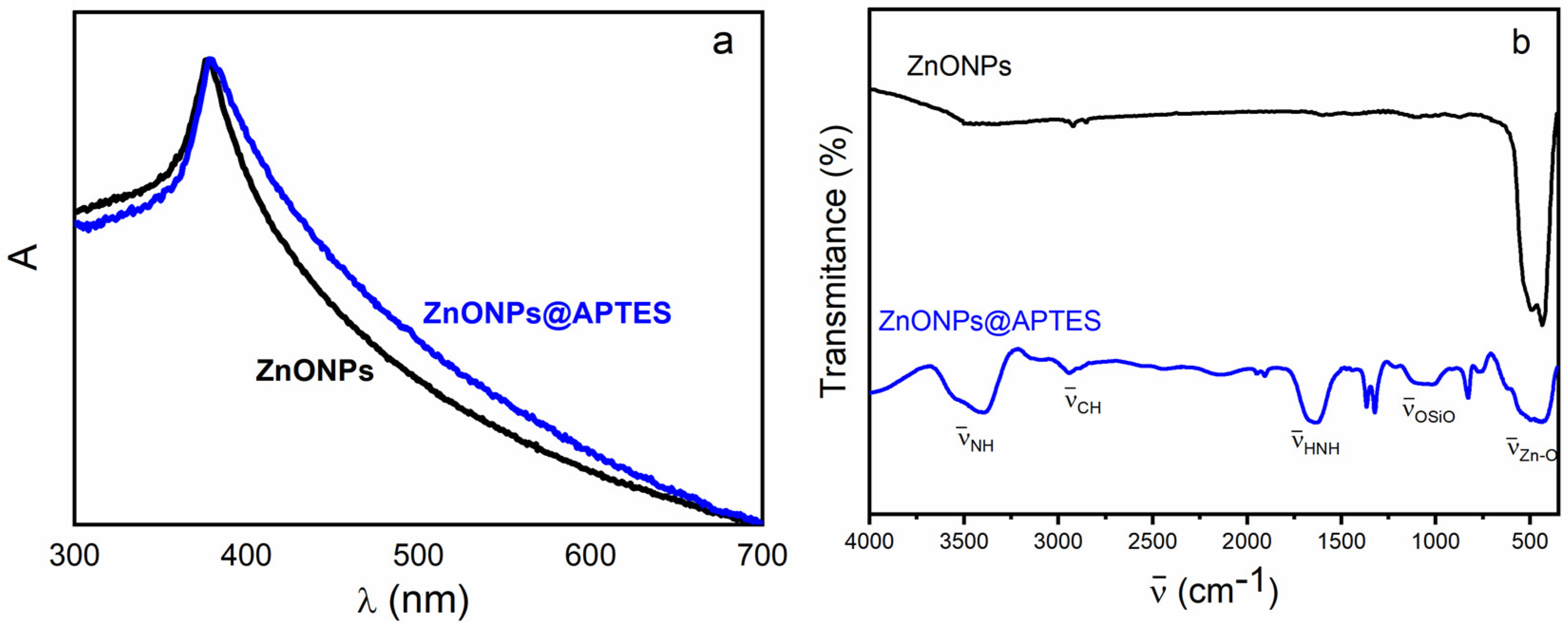

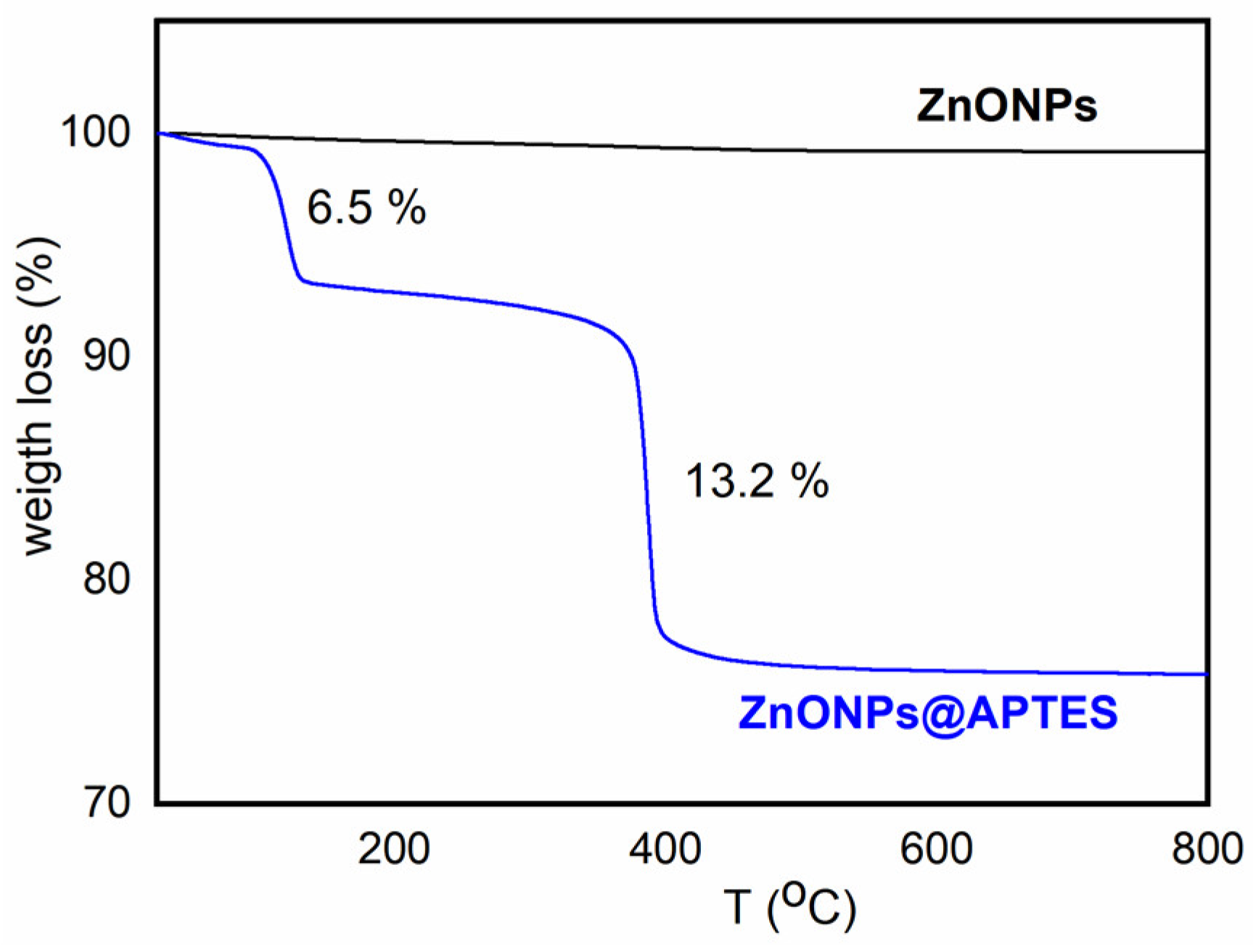

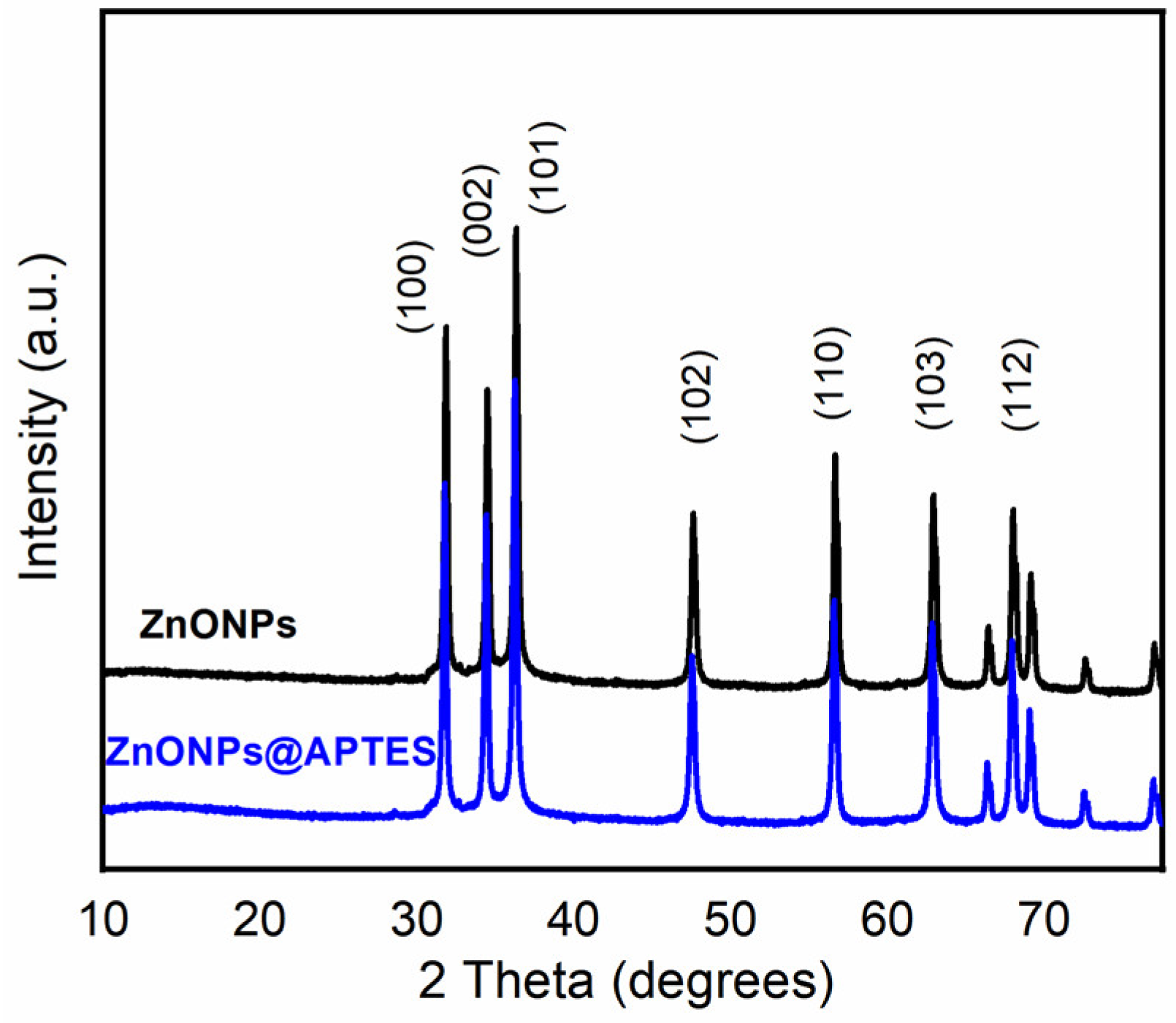

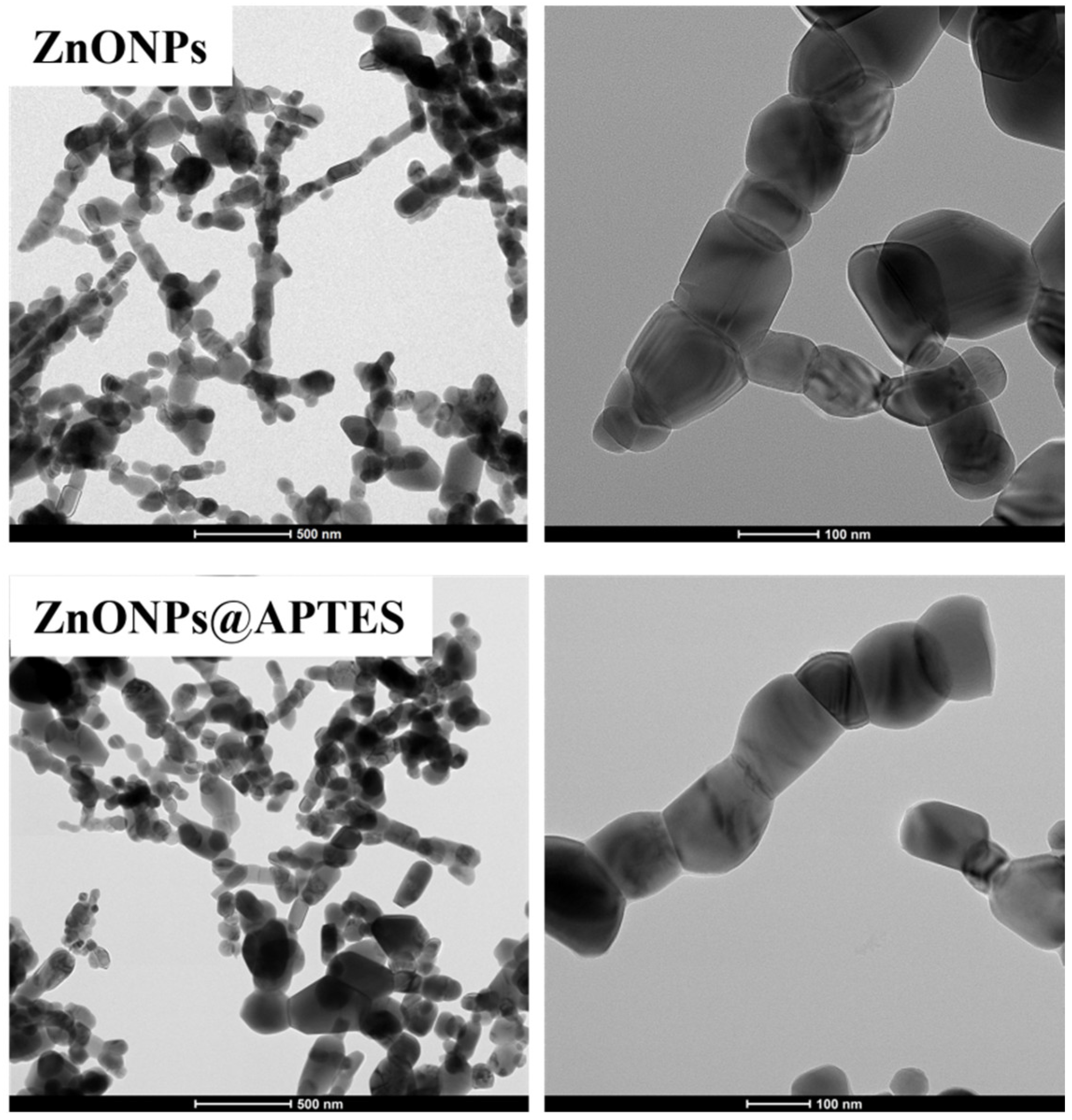

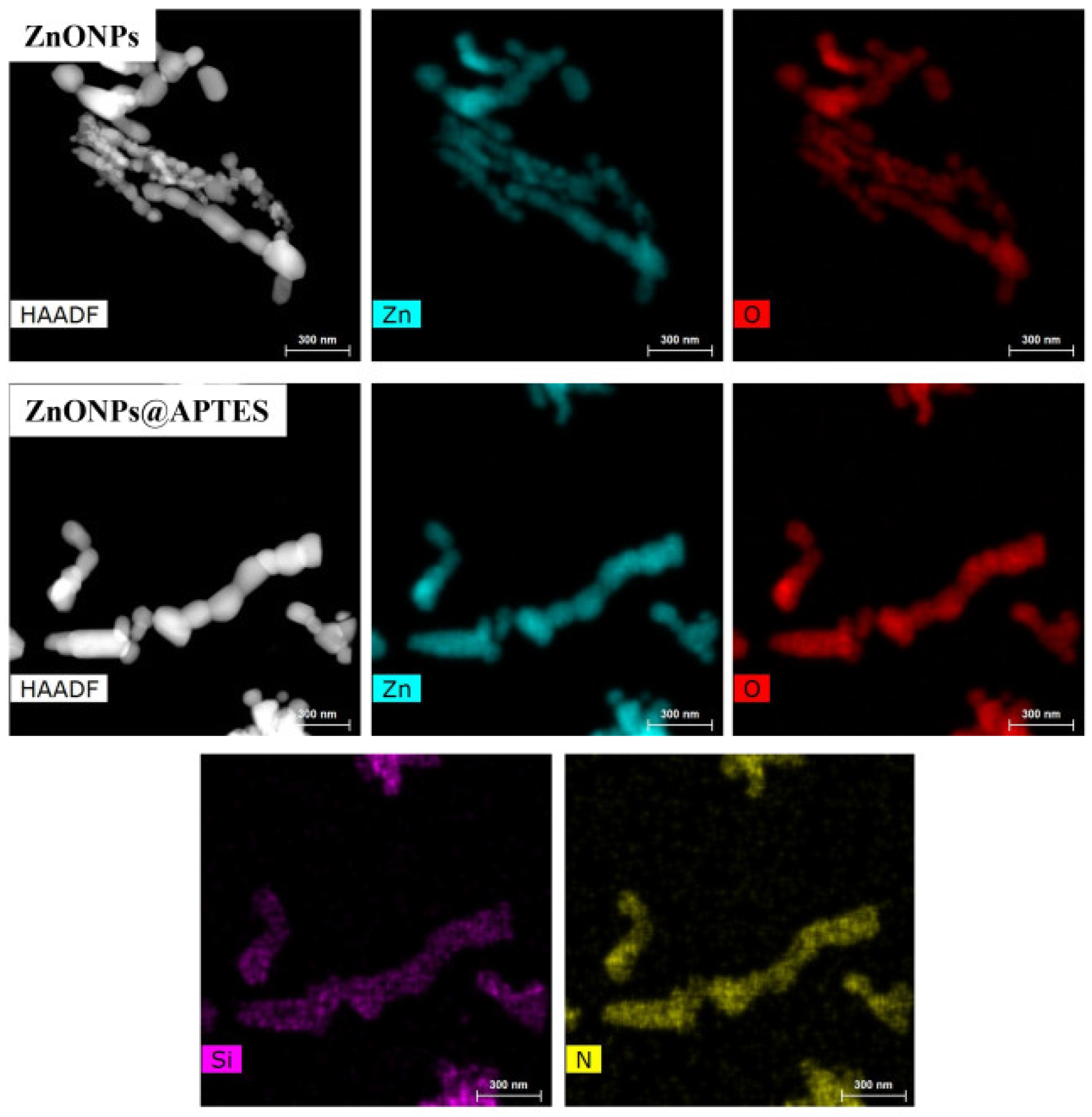

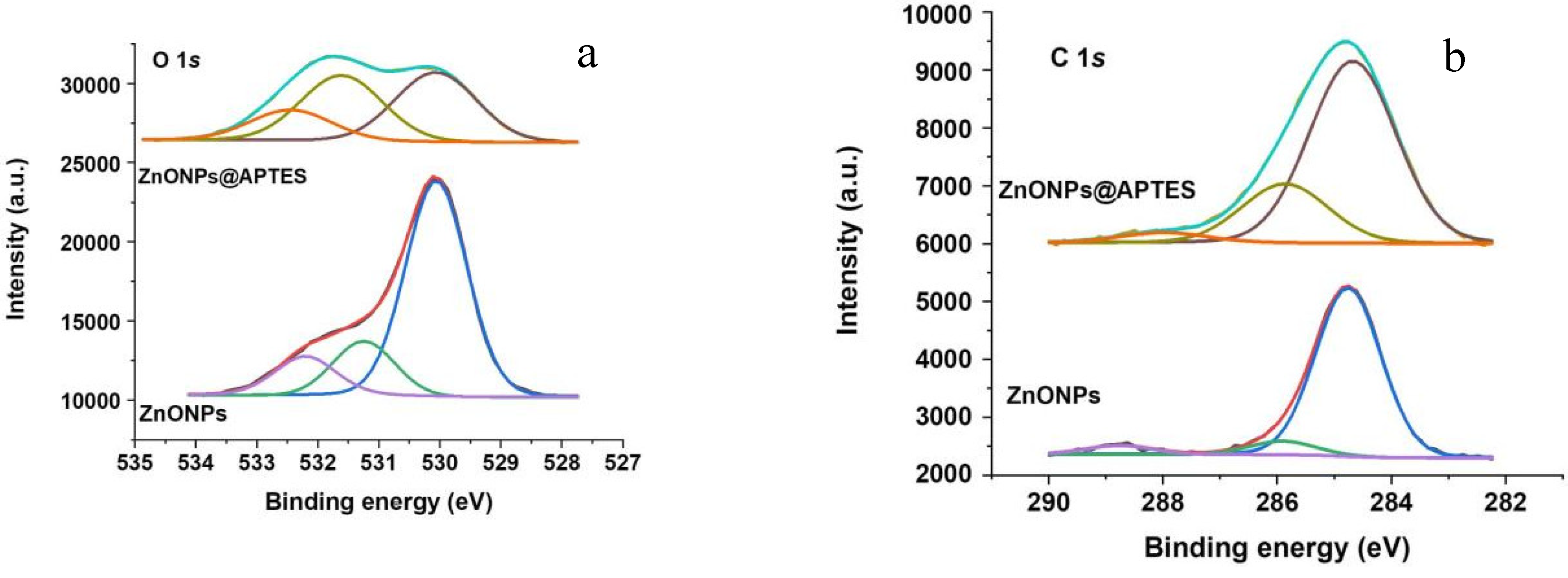

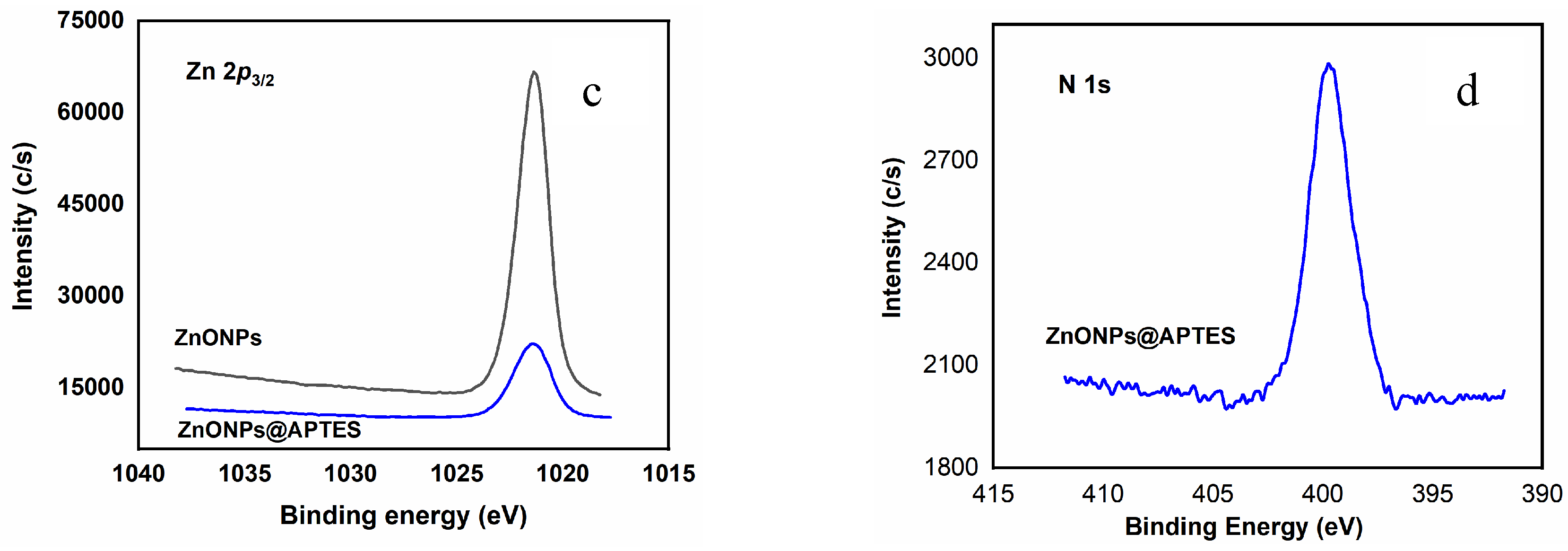

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of ZnO and ZnO@APTES Nanoparticles

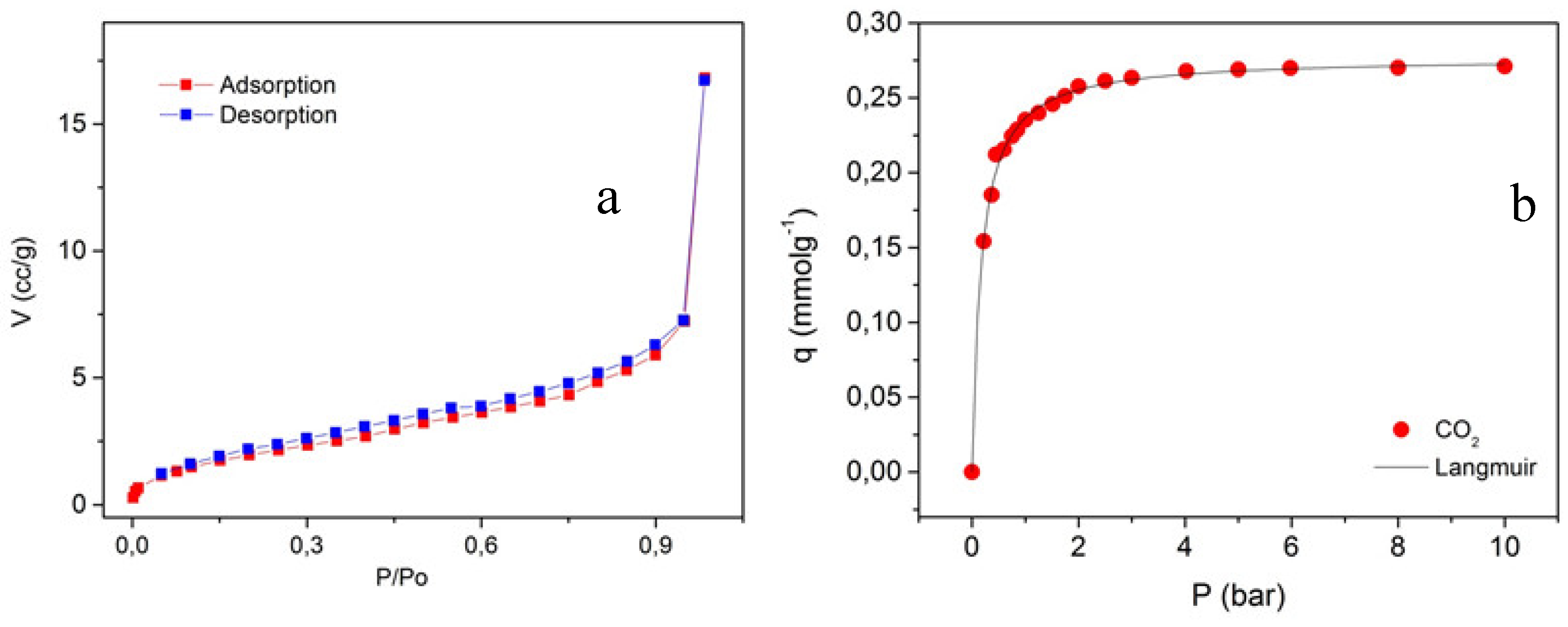

2.2. Gas Adsorption Experiments for ZnONPs@APTES

3. Discussion

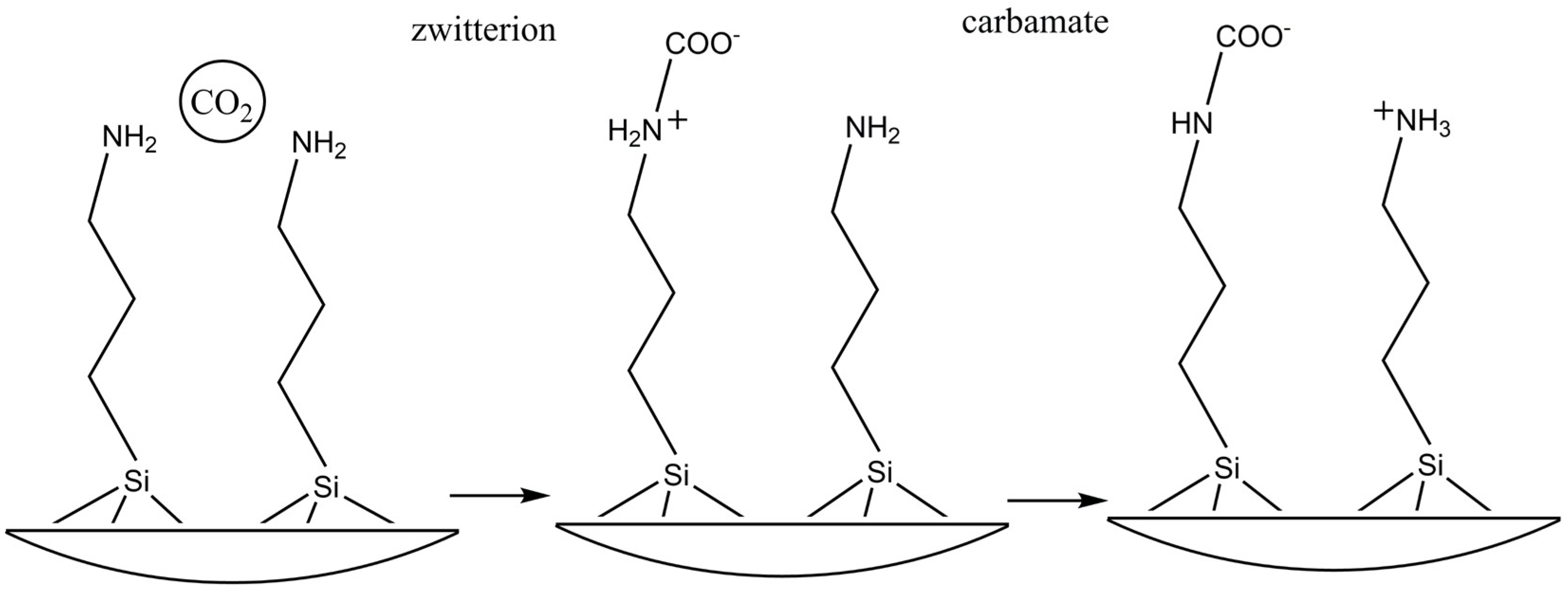

- Nucleophilic attack of the amino group on the carbon of CO2 and formation of the intermediate zwitterion (R1R2NH+COO-)R1R2NH + CO2 ®R1R2NH+COO- eq.III

- Acceptance of the proton by a base. Under anhydrous conditions, this function is performed by an adjacent amino group (primary or secondary) leading to the formation of the carbamate. (R1R2NCOO-)R1R2NH+COO- + Base (B)®BH+ +R1R2NCOO- eq.IV

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles (ZnONPs)

4.3. Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles Functionalized with APTES (ZnONPs@APTES)

4.4. Spectroscopic, Morphological and Thermogravimetric Characterization of ZnONPs and ZnONPs@APTES

4.5. N2, CO2 and CH4 Adsorption Experiments

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ding, M.; Guo, Z.; Zhou, L.; Fang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, L.; Xie, L.; Zhao, H. One-Dimensional Zinc Oxide Nanomaterials for Application in High-Performance Advanced Optoelectronic Devices. Crystals, 8: 223 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Saleem S., Jameel M. H. , Rehman A. , Tahir M. B., Irshad M. I., Jiang Z.-Y., Malik R.Q., Hussain A. A. , Rehman A., Jabbar A. H., Alzahrani A. Y., Salem M. A., Hessien M.M., Evaluation of structural, morphological, optical, and electrical properties of zinc oxide semiconductor nanoparticles with microwave plasma treatment for electronic device applications, Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 19: 2126-2134 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Jian J.-C., Chang Y.-C., Chang S.-P., Chang S.-J., Biotemplate-Assisted Growth of ZnO in Gas Sensors for ppb-Level NO2 Detection, ACS Omega 9 (1): 1077-1083 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Jian J.-C., Chang Y.-C., Chang S.-P., Chang S.-J., Biotemplate-Assisted Growth of ZnO in Gas Sensors for ppb-Level NO2 Detection, ACS Omega 9 (1): 1077-1083 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y., Pan, A., Su, Y. Q., Zhao, S., Li, Z., Davey, A. K., Zhao, L., Maboudian, R., & Carraro, C.. In-situ synthesized N-doped ZnO for enhanced CO 2 sensing: Experiments and DFT calculations. Sensors and Actuators, B: Chemical, 357: 131359 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y. Semiconducting Metal Oxides: Microstructure and Sensing Performance. In: Semiconducting Metal Oxides for Gas Sensing. Springer, Singapore. 271–297 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Zhang S., Li H., Zhang N., Zhao X., Zhang Z., Wang Yan, Self-sacrificial templated formation of ZnO with decoration of catalysts for regulating CO and CH4 sensitive detection, Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 330: 129286 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Sangchap M., Hashtroudi H., Thathsara T., HarrisonC. J., Kingshott P., Kandjani A. E., Trinchi A., Shafiei M., Exploring the promise of one-dimensional nanostructures: A review of hydrogen gas sensors, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 50 (A): 1443-1457 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Chen X., Bagnall D., Nasiri N., Capillary-Driven Self-Assembled Microclusters for Highly Performing UV Photodetectors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33: 2302808. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Alba-Cabañas J. , Rodríguez-Martínez Y. , Vaillant-Roca L. , Effects on the ZnO nanorods array of a seeding process made under a static electric field, Materials Today Communications 39: 108917 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Crapanzano, R.; Villa, I.; Mostoni, S.; D’Arienzo, M.; Di Credico, B.; Fasoli, M.; Scotti, R.; Vedda, A. Morphology Related Defectiveness in ZnO Luminescence: From Bulk to Nano-Size. Nanomaterials 10: 1983 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Güell F., Galdámez-Martínez A., Martínez-Alanis P., Catto A. C., da Silva L. F., Mastelaro V. R., Santana G., Dutt A. ZnO-based nanomaterials approach for photocatalytic and sensing applications: recent progress and trends Mater. Adv., 4: 3685-3707 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Motelica, L.; Vasile, B.-S.; Ficai, A.; Surdu, A.-V.; Ficai, D.; Oprea, O.-C.; Andronescu, E.; Mustățea, G.; Ungureanu, E.L.; Dobre, A.A. Antibacterial Activity of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Loaded with Essential Oils. Pharmaceutics , 15: 2470 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Kim I., Viswanathan K., Kasi G., Sadeghi K., Thanakkasaranee S., Seo J., Preparation and characterization of positively surface charged zinc oxide nanoparticles against bacterial pathogens, Microbial Pathogenesis, 149: 104290 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Najafi A. M., Soltanali S., Khorashe F., Ghassabzadeh H., Effect of binder on CO2, CH4, and N2 adsorption behavior, structural properties, and diffusion coefficients on extruded zeolite 13X, Chemosphere, 324: 138275 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Chang Y., Yao Ya., Wang L., Zhang Kun, High-Pressure adsorption of supercritical methane and carbon dioxide on Coal: Analysis of adsorbed phase density, Chemical Engineering Journal, 487: 150483 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Jiang C., Wang X., Lu K., Jiang W., Xu Huakai., Wei X., Wang Z., Ouyang Y., Dai F., From layered structure to 8-fold interpenetrated MOF with enhanced selective adsorption of C2H2/CH4 and CO2/CH4, Journal of Solid State Chemistry, 307:122881 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Gordijo J. S. , Rodrigues N. M., Martins J. B. L. , CO2 and CO Capture on the ZnO Surface: A GCMC and Electronic Structure Study, ACS Omega 8 (49): 46830–46840 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Montejo-Mesa, L. A., Autié-Castro, G. I. & Cavalcante, C. C. L. Evaluation of Zinc Oxide nanoparticles for separation of CH4-CO2. Rev. Cub. Quím. 30, 119–130 (2018). ISSN 2224-5421 http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=S2224-54212018000100010&script=sci_abstract&tlng=en.

- Hariharan, C. Photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminants in water by ZnO nanoparticles : Revisited. Applied Catalysis A: General 304, 55–61 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Erhart, P., Albe, K. & Klein, A. First-principles study of intrinsic point defects in ZnO : Role of band structure , volume relaxation , and finite-size effects. Physical Review B 73: 1–9 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Segets, D., Gradl, J., Taylor, R. K., Vassilev, V. & Peukert, W. Analysis of Optical Absorbance Spectra for the Determination of ZnO. ACS Nano 3: 1703–1710 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Viswanatha, R. et al. Understanding the quantum size effects in ZnO nanocrystals. J Matter Chem 14: 661–668 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Arya S., Mahajan P., Mahajan S., Khosla A., Datt R., Gupta V., Young S.-J., Oruganti S. K. Review—Influence of Processing Parameters to Control Morphology and Optical Properties of Sol-Gel Synthesized ZnO NanoparticlesECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 10: 023002 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Roslan A. A., Zaine S. N. A., Zaid H. M., Umar M., Beh H. G., Nanofluids stability on amino-silane and polymers coating titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles, Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal, 37: 101318 (2023). [CrossRef]

- PDF-2 File. JCPDS International Center for Diffraction Data, 1601 Park Lane, Swarthmore, PA.

- Raha S., Ahmaruzzaman Md., ZnO nanostructured materials and their potential applications: progress, challenges and perspectives, Nanoscale Adv., 4: 1868-1925 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi Reza, Talesh S. S. A., Effects of amine (APTES) and thiol (MPTMS) silanes-functionalized ZnO NPs on the structural, morphological and, selective sonophotocatalysis of mixed pollutants: Box–Behnken design (BBD), J. Alloys Compd., 896: 163121 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Rao, X., Abou, A., Cédric, H., Mengxue, G. & Stephanie, Z. Plasma Polymer Layers with Primary Amino Groups for Immobilization of Nano - and Microparticles. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 40: 589–606 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Min, H., Gross, T., Lippitz, A., Dietrich, P. & Unger, W. E. S. Ambient-ageing processes in amine self-assembled monolayers on microarray slides as studied by ToF-SIMS with principal component analysis , XPS , and NEXAFS spectroscopy. Anal Bioanal Chem 403, 613–623 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Casula, G., Fantauzzi, M., Elsener, B. & Rossi, A. XPS and ARXPS for Characterizing Multilayers of Silanes on Gold Surfaces. Coatings 14, 327–345 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M. et al. Physisorption of gases , with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution ( IUPAC Technical Report ). Pure Appl Chem 87, 1051–1069 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Brunauer, S., Emmett, P. H. & Teller, E. Adsorption of Gases in Multimolecular Layers. Journal of the American Chemical Society 60, 309–319 (1938). [CrossRef]

- Siriwardane, R. V et al. Adsorption of CO2 on Zeolites at Moderate Temperatures. Energy & Fuels 19, 1153–1159 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Arencibia, A., Pizarro, P., Sanz, R. & Serrano, D. P. CO2 adsorption on amine-functionalized clays. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 282, 38–47 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, E. & Schroeder, K. Effect of Moisture on Adsorption Isotherms and Adsorption Capacities of CO2 on Coals. Energy & Fuels 23, 2821–2831 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Vilarrasa-García E., Cecilia J.A., Santos S.M.L., Cavalcante C.L., Jiménez-Jiménez J., Azevedo D.C.S., Rodríguez-Castellón E. CO2 adsorption on APTES functionalized mesocellular foams obtained from mesoporous silicas. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 187, 125–134 (2014). [CrossRef]

- E. Vilarrasa-García, J. A. Cecilia, M. Bastos-Neto, C. L. Cavalcante Jr., D. C. S. Azevedo, E. R.-C. CO2/CH4 adsorption separation process using pore expanded mesoporous silicas functionalizated by APTES grafting. Adsorption 565–575 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Caplow, M. Kinetics of Carbamate Formation and Breakdown. J. Am. Chem. Socm Chem. Soc, 89, 6795–6803 (1968). [CrossRef]

- Danckwerts P.V. The reaction of CO2 with ethanolamines. Chem. Eng. Sci., 34: 443–446 (1979). [CrossRef]

- Rietveld, H. M. A profile refinement method for nuclear and magnetic structures. J Appl Cryst 2, 65–71 (1969). [CrossRef]

- Dreisbach, F., Staudt, R. & Keller, J. U. High Pressure Adsorption Data of Methane , Nitrogen , Carbon Dioxide and their Binary and Ternary Mixtures on Activated Carbon. 227, 215–227 (1999). [CrossRef]

| Elements/Series | Weigth (%) | Atomic (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO | ZnONPs@APTES | ZnO | ZnONPs@APTES | |

| Zn/K-series | 70.89 | 59.12 | 37.34 | 23.51 |

| O/K-serie | 29.11 | 20.50 | 62.66 | 33.31 |

| N/K-serie | - | 0.34 | - | 0.62 |

| Si/K-serie | - | 0.66 | - | 0.62 |

| C/K-serie | - | 19.38 | - | 41.94 |

| Sample | C 1s | N 1s | O 1s | Si 2s | Zn 2p3/2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnONPs | 284.8 (88) | 530.1 (69) | - | ||

| 285.9 (7) | - | 531.2 (17) | 1021.3 | ||

| 288.8 (5) | 532.2 (14) | ||||

| ZnONPs@APTES | 284.8 (73) 285.9 (23) 288.0 (4) |

399.7 | 530.1 (42) 531.6 (40) 532.4 (18) |

153.1 |

1021.4 |

| ZnONPs | 20.02 | - | 42.73 | - | 37.25 |

| ZnONPs@APTES | 39.31 | 7.16 | 32.32 | 8.84 | 11.38 |

| Sample | Surface area (m2g-1) | Pore volume(cm3g-1) | C |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZnONPs [19] | 7 | 0.018 | 2.11 |

| ZnONPs@APTES | 8 | 0.011 | 27.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).